Abstract

There are over 1 million transgender people living in the United States, and 33% report negative experiences with a healthcare provider, many of which are connected to data representation in electronic health records (EHRs). We present recommendations and common pitfalls involving sex- and gender-related data collection in EHRs. Our recommendations leverage the needs of patients, medical providers, and researchers to optimize both individual patient experiences and the efficacy and reproducibility of EHR population-based studies. We also briefly discuss adequate additions to the EHR considering name and pronoun usage. We add the disclaimer that these questions are more complex than commonly assumed. We conclude that collaborations between local transgender and gender-diverse persons and medical providers as well as open inclusion of transgender and gender-diverse individuals on terminology and standards boards is crucial to shifting the paradigm in transgender and gender-diverse health.

Keywords: gender and sexual minorities, transgender persons, electronic health records, bioethics

INTRODUCTION

Thirty-three percent of transgender persons have had negative experiences with healthcare providers and 23% describe avoiding needed medical care due to fear of mistreatment.1 Reasons for avoiding care include experiences of misgendering, pathologization, and medicalization.1–4 These forms of discrimination have been codified in electronic health records (EHRs), as well as in diagnostic and billing codes and criteria including the DSM, Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED-CT), and International Classification of Diseases (ICD), becoming the de facto language of treatment. It is especially concerning that terms like “sodomy,” “surgically transgendered transsexual,” and “transvestic fetishism” persist in some terminologies. These terms, formed from alleyways of systemic discrimination,5 continue to perpetuate anti-LGBTQ violence, despite protest against their usage from affected groups.6–10 As feminist scholar Sara Ahmed noted in a 2018 talk: “When those who try to stop a culture from being reproduced are stopped, a culture is being reproduced,”11 thereby continuing an already ever-present cycle of transphobic rhetoric in medical standards and terminologies.3,12–16

For the past 3 centuries,22 medical professionals have diagnosed being transgender as schizophrenia,23–26 paraphilia,27,28 multiple personality disorder,29,30 borderline personality disorder,31,32 narcissistic personality disorder,33 obsessive-compulsive disorder,34 or autism,40,41 if analyzed in terms of contemporary understandings of the term transgender (see Definitions and Concepts). However, it is of note that a number of cultures have gender systems that are not binary and have varying degrees of gender diversity (as judged by contemporary Eurocentric/binary standards), in general and including rituality some have compared with hormone replacement therapy and gender-affirming surgery; further, some of these cultures have histories of gender diversity stretching back far further than a few centuries, up to thousands of years.17–21 While it is crucial to avoid pathologization of trans experiences (ie, suggesting that transness itself is a mental disorder or condition), it is important to acknowledge that a number of neurodiverse people identify as trans and gender diverse.35,36 Oftentimes, such neurodiversity is inappropriately used as a mechanism to deny access to potentially life-saving gender-affirming care.37,38 For an in-depth exploration of the intersections between neurodiversity and gender diversity, see Adams and Liang.39

Even in contemporary literature, pathological terms such as “gender dysphoria syndrome,”42 “transsexual syndrome,”43 “gender identity disorder,”44 “transsexualism,”16,45 and “transgenderism”16,46,47 still exist. “Transgender” continues to appear on patients’ problem lists.48–50 While this is partially due to vocabulary systems like SNOMED CT and ICD, this is also part of a larger systemic problem concerning how a “problem list” is defined. Oftentimes, there is nowhere else to indicate that a patient is transgender, forcing even affirming providers to use it. Replacement terminology or another area provided for such indications to not be labeled as “problems” is vital to preventing pathologization and medicalization of transness.

Prejudice and discrimination against transgender people in biomedical research and medical practice are well established.1,51–66 The misunderstanding and erasure of gender diversity has led to poor study design, additional barriers accessing care, unethical disclosure of transgender status in medical contexts, and in some cases, patient death. Three prominent cases of avoidable patient death due to negligence include that of Lou Sullivan, who died in 1991 after being denied care at an HIV/AIDS clinic67; Tyra Hunter, who died in 1995 when emergency medical technicians discovered she was transgender while treating her after a car accident and refused to save her life68; and Alejandra Monocuco, who died from COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) after emergency medical technicians learned of her HIV status in 2020.69 Little has changed in terms of either medical discrimination against transgender patients, or data collection and usage with transgender patients in the period spanning their deaths.22,70,71 To move past barriers to proper health care for transgender people, both fields must undergo paradigm shifts.

Sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) EHR data collection policies are currently implemented without adequate knowledge of the needs of transgender populations, without provider education, and often only in limited care contexts (such as psychiatric, endocrinological, and gender identity clinics).72,73 Additionally, many policies have been rolled back as the result of political pressures,70,71,74 despite a call to action for supporting transgender scientists during the epidemic.75 In one case involving the COVID-19 National Institutes of Health Researchers Survey SOGI questions, 2 of this piece’s authors were told via personal communication that a 2-step question, like the one proposed later in this perspective, concerning assigned sex at birth was omitted due to concern “about the number of demographic questions,” despite its validated efficacy.74,75 As a result, transgender populations are, and will not be, adequately described in biomedical contexts.

Ethical data collection for transgender and gender-diverse communities in health care is needed now more than ever. Medical providers and health informaticians have a duty to address the ongoing systemic mistreatment of transgender and gender-diverse people within healthcare institutions.76,77 Accurate research is crucial to redressing inequities. To policymakers, what is not documented might as well have never happened.

DEFINITIONS AND CONCEPTS

Accurate and equitable clinical practice and research requires discussion of operational standards.78–80 Transgender populations have often been defined in terms of relationships to diagnostics ,81–83 procedures,44,84 or assigned sex at birth (ASAB) or assigned gender at birth (AGAB) vs gender identity data (Table 1).94,95 The differences in terminology are important to discuss, not only because they have impact on clinical care,96 but also because lack of appropriate terminological frameworks in research studies impacts the usability, applicability, and reproducibility of results.

Table 1.

Selected definitions of the term “transgender” and its variants, 1965-2021, showcasing how the term continues to evolve and change over time, oftentimes making results of studies utilizing the term (or similar terms) nonreproducible85

| Year | Definition | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1965 | Where the compulsive urge reaches beyond female vestments, and becomes an urge for gender (“sex”) change, transvestism becomes “transsexualism.” The term is misleading; actually, “transgender[ism]” is what is meant, because sexuality is not a major factor in primary transvestism. | 86 |

| 1978 | [Transgenderists] are people who have adopted the exterior manifestations of the opposite sex on a full-time basis but without any surgical intervention. | 87 |

| 1988 | It used to be that a “transgender[ist]” was a person who could express him or herself comfortably in both masculine and feminine terms… Recently, however, the term “transgender[ist]” has come more and more to mean a person of one sex living entirely in the gender role generally considered appropriate for the opposite sex (cross-living). Most people who consider themselves to be transgender[ist]s do not want or need sexual reassignment surgery, and do not identify with “transvestite.” | 88 |

| 1998 | Originally, transgender referred to the group of people, also know[n] as full-time cross-dressers or nonsurgical transsexuals, who live and work as the opposite gender continuously and for always. Now it more often refers to the group of all people who are inclined to cross the gender line, including both cross-dressers and gender-benders, the “umbrella definition” that covers everyone. | 89 |

| 2008 | An umbrella term for people whose gender identity and/or gender expression differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. The term may include but is not limited to transsexuals, cross-dressers, and other gender-variant people. Transgender people may identify as female-to-male (FTM) or male-to-female (MTF). Use the descriptive term (transgender, transsexual, cross-dresser, FTM, or MTF) preferred by the individual. Transgender people may or may not decide to alter their bodies hormonally and/or surgically. | 90 |

| 2011 | Relating to or being a person whose gender identity does not conform to that typically associated with the sex to which they were assigned at birth. | 91 |

| 2018 | Often shortened as “trans.” An umbrella term for people whose gender and/or expression does not match their birth assignment. Transgender includes many of the terms in this list and may or may not include transsexuals, cross dressers, drag kings/queens, and others who defy what society tells them their gender should be. How people identify with this term depends on the individual and their relationship with their gender. | 92 |

| 2021 | A term describing a person’s gender identity that does not necessarily match their assigned sex at birth. Transgender people may or may not decide to alter their bodies hormonally and/or surgically to match their gender identity. This word is also used as an umbrella term to describe groups of people who transcend conventional expectations of gender identity or expression—such groups include, but are not limited to, people who identify as transsexual, genderqueer, gender variant, gender diverse, and androgynous. | 93 |

In this work, we use Ashley’s gender modality framework to discuss the term transgender as specifically representing an incongruence between one’s AGAB and one’s gender identity.97 Occasionally, transgender is shortened as trans.92 We also sparingly use the term transgender and gender diverse, which is meant to be inclusive of gender diversity that does not specifically fall under the gender modality framework .

Within this framework, we would first like to clarify the meanings of 2 terms: sex and gender. In international legal systems, these terms are often defined as being interchangeable, given that a number of languages do not have a gender-sex distinction linguistically.98–101 This necessitates usage of qualifying terms such as assigned sex or gender identity.105 For instance, “gender identity” may be rendered as “sex identity” in some languages.102–104 Yet, while gender identity is widely understood as the gender one identifies as, assigned sex (at birth) often is not. Owing to confusion individuals may have over the phrasing, there is often an additional clause added when asking for ASAB, namely clarifying that what is meant is the gender marker on an individual’s birth certificate or other birth record.106–108 It is at this point that ASAB in theory becomes AGAB in practice. This is because birth certificates (and by extension, birth records) are legal documents109–111 containing a marker that is a culturally dependent and socially constructed signifier (and therefore correctly called a gender marker).112,113 A list of known culturally dependent AGAB values is linked in the additional supplementary tables in Supplementary Appendix A. Owing to translation difficulties, it is entirely possible that “assigned gender at birth” may be rendered as “assigned sex at birth” in some jurisdictions and languages. In terms of clinical practice (and therefore in medical standards), this will likely not affect care. However, it is important to realize that these are fundamentally different concepts and relate different information, which may become an issue in terms of cultural competency in some regions, that is, “sex” implies a fundamentally biological component in English (even if this is not always the case with “assigned sex at birth”), which can insinuate that a provider believes that a trans woman patient’s “real” sex is “male.”

PERSPECTIVES ON DATA COLLECTION

From the clinical perspective

When a transgender person enters a clinic, health care is rarely their sole concern. Will the staff use their name and pronouns? Will their privacy be respected? Will the clinic provide adequate services or services at all? These questions burden transgender people as they navigate the medical system, and they are often answered quickly through implicit and explicit cues.

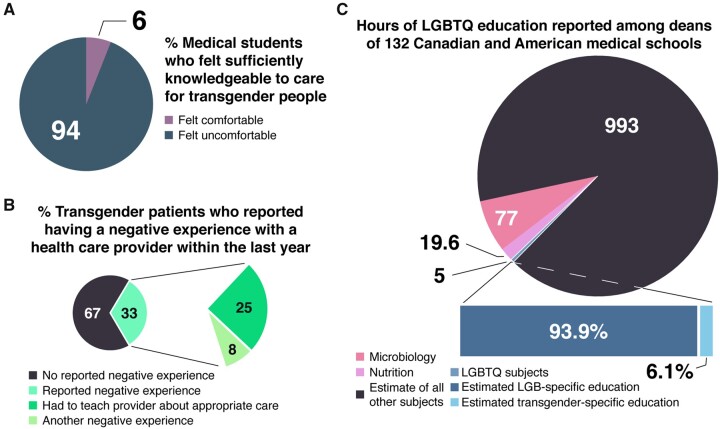

Because providers rarely understand their trans patients’ lived realities, their unique needs and questions are seldom prioritized. Expecting boards comprised mostly or entirely cisgender medical professionals or EHR vendors to understand what transgender patients need without close collaboration is impractical, especially given the dearth of LGBTQ health education in most medical training (Figure 1).116,117,126–130 (LGBTQ is the abbreviated form of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning. Note that LGBTQIA+114 or 2SLGBTQIA+115 may be more appropriate if the curriculum also actively includes Two-Spirit, intersex, and asexual or aromantic persons, as well as other marginalized or minoritized sexual- or gender-based groups.) Up to half of transgender people must educate their providers to receive appropriate care.1,131 This structural incompetency translates into significant pitfalls in SOGI data collection.132–135

Figure 1.

The current state of trans healthcare education, wherein patients are the primary educators of providers. (A) The percentage of medical students among 365 Canadian medical schools who felt knowledgeable enough to care for transgender patients.116 (B) Percentage of transgender patients who reported having a negative experience with a healthcare provider in the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey (USTS).1 (C) The number of LGBTQ education hours117 and estimated percentage of transgender education hours,116,118 based on percentage hours in other disciplines,119 compared with hours in nutrition and microbiology.120,121 The total number of hours was conservatively estimated based on 1100 hours of instruction in the first 2 years of medical school. We estimate that approximately 18.3 minutes of medical education is spent on transgender-related care, care which is potentially life-saving for millions of people.122–125

SOGI data collection often begins with intake forms. Institutions and providers do not always understand how to ask for one’s gender identity. Gender identities can include female (woman), male (man), and nonbinary, among numerous others. In EHR systems, gender identity answers often include “FTM” (short for female-to-male), “MTF” (short for male-to-female), “transgender male,” “transgender female,” and simply “transgender.”136–139 These options are antiquated and problematic, in part owing to the massive shift in the conceptualization of what these terms have meant over the past 8 decades (Table 1). The first 2 (FTM and MTF) have largely fallen out of use among transgender people and in transgender-related literature because they fundamentally assume a “change” in gender—that a transgender person was “female” and now is “male” (FTM), typically after some sort of medicalization process (hormone replacement therapy and/or gender-affirming surgery).137,141,149–151 This contradicts how many trans people understand their identity and can confuse patients. Note that distaste toward “FTM” and “MTF” is not universal; many transgender men have centered much of their North American community around the usage of FTM (in organizations like the FTM Foundation and FTM International, for instance), whereas the usage of “MTF” is more heavily tied to the pornography industry and is actively utilized to discriminate against transgender women.140–144 Two other terms that have become more popular in the last decade to describe “directionality” of transness, being “transfeminine” and “transmasculine.” While these terms are marginally more effective than terms like “FTM” and “MTF” and often are used to describe an individual’s gender identity,145 we would like to emphasize that their usage tends to conflate access to medical care with unspoken gender expression requirements, that is, insisting that trans women must be feminine or that trans men must be masculine to be considered as having “succeeded” in transitioning.146,147 Further, these terms often binarize nonbinary persons unnecessarily.147,148 In medical contexts, using assigned gender at birth alongside gender identity already achieves most of what terms like “transfeminine” and “transmasculine” attempt to elucidate. Therefore, we use terms like “assigned male at birth” or “assigned female at birth” where necessary in this article. All 5 options (being “FTM,” “MTF,” “transgender male,” “transgender female,” and “transgender”) center cisgender people on intake forms, reserving unqualified “male” and “female” for them while trans people are segregated into the separate, qualified categories of “MTF,” “FTM,” “transgender male,” “transgender female,” and “transgender.” Fundamentally, this implies trans women and trans men are deviant and not actually female or male, respectively, especially when the selection is ordered as “male,” “female,” “MTF,” and“FTM.”156–158 Usage of “transgender male” and “transgender female” may be confusing as well, as the terms have varied over time. For instance, some sources use “transgender male” or “transsexual male” to refer to a trans man,152,153 while others used it to refer to a trans woman.154,155 Further, by separating these groups in the first place, “male” and “female” are presented as the norm while “transgender male” and “transgender female” are othered.138,156–159 The separation can insinuate that transgender people are not their stated gender and that separation is cited heavily in transphobic and exclusionary actions.160–162 Additionally, it has been noted that terms like “FTM” and “MTF” are likely to be misinterpreted and confused within medical systems, with anecdotal evidence supporting the notion that terms like “FTM top surgery,” “MTF bottom surgery,” etc. being misunderstood because the actual procedure is unclear from those phrases alone. In addition to the cited sources regarding the separation of binary trans identities from unqualified terms, one of the authors (C.A.K.) ran an informal 24-hour Twitter poll and received 401 responses, with 84% noting that the separation implied that “trans woman”/”trans man” was deviant and “woman”/”man” was normal. Further, just under 14% of trans men and trans women elected to de-emphasize their trans status via write-in on the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, even when the question asked was not considering gender identity, but instead considering general identity terms. For the data methodology used to analyze the U.S. Transgender Survey data, see Supplementary Appendix A, Supplement B. In practice, many binary transgender persons indicated they would answer “female” over “MTF” or “transgender female.”

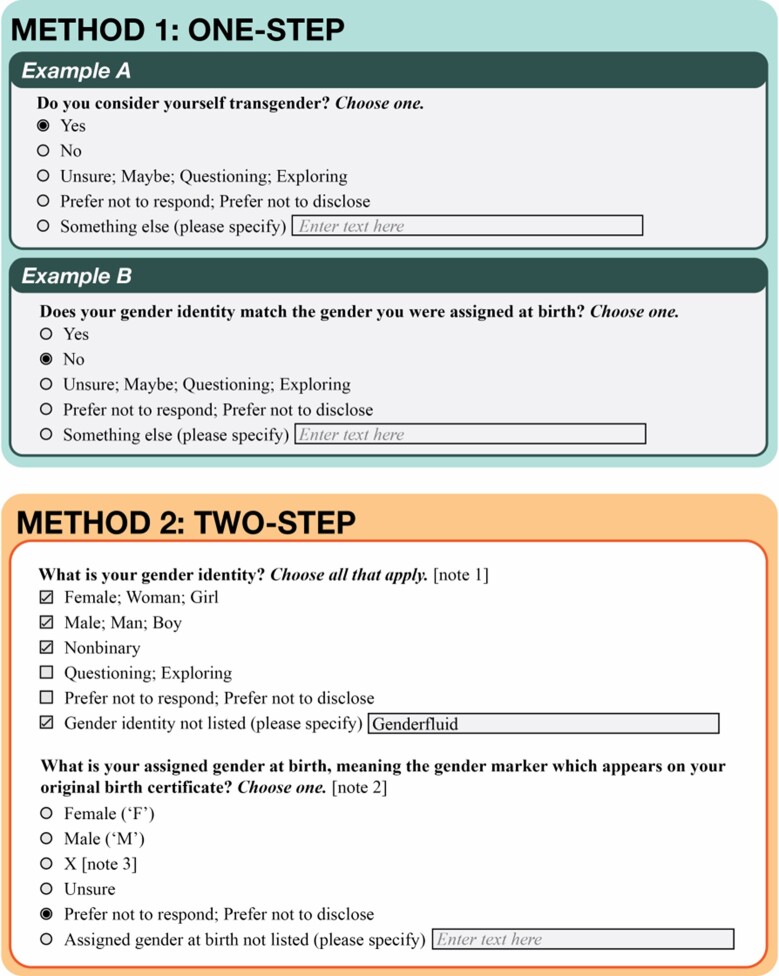

For nonbinary people, being relegated to an “other” category is often experienced as a literal “othering” whereas the inclusion of a “nonbinary” category communicates inclusion.136,138,158,163 Unfortunately, intake forms guided by the Veteran Affairs’ “Self-Identified Gender Identity” initiative employ such exclusionary linguistic practices. The initiative enforces a distinction between transgender and cisgender individuals by providing patients the options of “male,” “female,” “transman,” “transwoman,” “other,” and “the individual chooses not to answer.”168 Additionally, the inclusion of “transwoman” and “transman” is not best practice or grammatically correct. The othering effect this has is another subtle linguistic turnoff to transgender patients. “Trans” is an adjective and the correct wording would be “trans woman” or “trans man” with a space.164–167 EHRs should accurately record transgender people’s gender based on their gender identity as male, female, nonbinary, etc. such as that presented in Figure 3 (see also the additional supplementary tables for further discussions of possible regional extensions).

Figure 3.

Examples of 2 ways to ask for identification of transgender identity: direct method (1-step) and indirect method (2-step); indicates different options that may be used to similar effect in certain circumstances. In general, it should be clear that this information is not a proxy for karyotype or organ inventory, which should be ascertained independently (see “Additional Considerations”). However, it is important to include for providers, researchers, and patients, as patients might not have karyotype- or organ inventory–based knowledge and tests may be unaffordable, unavailable, or unnecessarily invasive. Note 1: For neonates and infants for which gender identity has not yet developed, a medical provider could enter “unknown,” “uncertain,” “undifferentiated,” or “none.” Note 2: This may only be appropriate in some jurisdictions as the original birth certificate may no longer officially exist (such as in Germany). It does resolve ambiguity in a situation wherein a patient has been issued a new birth certificate with an updated gender marker. Additionally, there may be values and options for this question that differ significantly by jurisdiction. Note 3: “X” is allowed in some jurisdictions, such as in New York City, Washington DC, New Jersey, California, etc. and has been recently approved for federal documentation in the U.S.170 While occasionally intersex is considered a gender identity or as an assigned gender at birth, this is commonly thought of as inappropriate, because intersex people can have many different gender identities or assigned genders at birth (some intersex people do identify their gender identity as “intersex” or “hermaphrodite” [typically as a form of reclamation], but these identifications can adequately be covered by “A gender not listed [please specify]” in most cases).171 For more information on intersex-inclusive question design, see “Intersex Data Collection: Your Guide to Question Design.”172 It is also important to note that birth certificates may change to not include gender markers or may not be consistent from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.111,173,174 Therefore, a two-step is simply a better proxy to gender- and/or sex-related information than a one-step, which may be replaced in the future with more accurate models incorporating information like hormonal milieau.

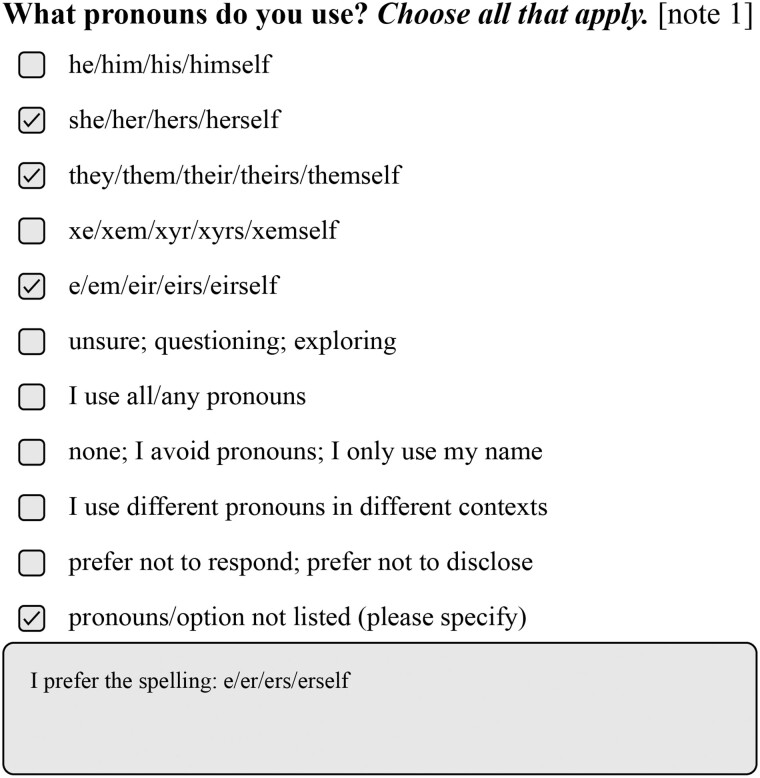

In addition to avoiding derogatory and othering terms when referring to transgender people’s gender, EHRs should encode their correct name and pronouns. Accurately recording person’s name and pronouns without labelling either as preferred or chosen is necessary to improve transgender health.176 English-language pronoun sets have begun to be codified in some EHRs.175 For instance, LOINC provides an answer list for reported personal pronouns (https://loinc.org/90778-2/), and the HL7 Gender Harmony Project has announced inclusion of pronouns per their current balloting process (for more information on pronouns and for example use cases, see https://www.mypronouns.org/what-and-why and https://pronoun.is/). Usage of the correct name and pronouns is linked to lower risk of depression, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior among trans people.59,96,177

Adding pronoun-related information in EHRs can easily be modeled as part of the software, with example usage sentences provided using an automated system, some of which are open source.178–180 A potential setup for asking a person their pronouns is shown in Figure 2 but giving one’s pronouns and asking for the patients’ during all clinical interactions should be made routine in all patient care. Pronoun information can also be included with a list of utilized titles or honorifics. An algorithm connected to a person’s selected pronouns or titles can be used to automatically set the appropriate terms in the provider’s notes.

Figure 2.

A potential question to ask an individual their pronouns. Individuals may use or be comfortable with multiple sets of pronouns, hence “choose all that apply.” Neopronouns were added based on the 2 most recent Gender Censuses (2020, 2021), in which over 24 000 and 44 000 nonbinary people, respectively, were queried about their terminological usages.181,182 Pronoun sets could be shifted in or out based on usage statistics on a local level over a period of time. Having a pronoun not listed could alert the medical provider about pronoun usage prior to the encounter. Selecting “prefer not to respond; prefer not to disclose” or the like could trigger a series of potential privacy options, wherein the patient could determine pronouns for various kinds of healthcare encounters depending on safety, presentation, etc.

While it is essential for the medical provider to have current and accurate information, it is also necessary for frontline staff to have sufficient training to conduct intake without misgendering or distressing transgender patients. Misgendering patients fosters distrust when the healthcare system is already perceived as unsafe by many transgender people and can lead to poor health outcomes.59,96 The healthcare system must also undergo transformational change, and we ask for more than just brief intervention-based training, but rather for a system in which transgender care knowledge is integrated into the pedagogy of healthcare disciplines.130

All gender-related demographic information should be modifiable by patients without a provider’s consent. Requiring a medical provider to change the data may (1) unnecessarily out the patient to the provider, (2) lead to potentially transphobic or wrong information being entered given the state of LGBTQ medical education, or (3) pathologize and medicalize one’s status as transgender. Regardless of how EHR data is recorded, transgender patients must be assured of their autonomy, privacy, and confidentiality throughout the process.183 As one trans person put it, “If you can’t even go to the bathroom without fearing for your safety, then why would you feel safe disclosing your [identity] in a… medical setting?”184

From the researcher’s perspective

Used appropriately, EHRs can improve the quality of care and research on transgender patient populations by facilitating consistency and comprehensiveness in population definition. Transgender prevalence estimates can differ significantly based on case definition; therefore, patient self-identification is the gold standard.85,185 Usage of methodologies such as ICD codes or free text linked primarily to procedures or diagnostics considered trans-related prioritizes White, middle-class transgender persons because these individuals showcase higher utilization of gender-affirming hormone therapies and surgeries,1,186,187 higher rates of insurance coverage,188 lower poverty rates,1,189 and lower mortality rates.190,191

There are 2 common methods for patient self-identification (Figure 3).136,138,156,157,192 Note that the answers provided in Figure 3 are placeholders and reference the set of tables derived in the additional supplementary tables, which provide further notes and international implications/considerations..

Both methods have significant advantages for researchers collecting data on transgender persons. In the first version, all individuals who responded “yes” in their most recent intake forms have self-identified as transgender.

The second casts a wider net. If a person selects “Male” for both questions, they are considered a cisgender man, whereas a person who selects “Female” as a gender identity then “Male” as their AGAB would be considered a transgender woman.192,193 This method also captures nonbinary persons who may not consider themselves transgender. It also includes persons who have undergone transition-related processes and no longer consider themselves transgender. It is crucial to emphasize that the gender identity question should be asked first, as asking for a person’s AGAB first implies that AGAB is an individual’s “real” gender, denying the individual’s lived experience.194

The 2-step methodology has the distinct advantage that we can split our transgender population into “assigned male at birth” or “assigned female at birth” (or other gender assignment designations), as well as into “trans women” (answering “Female,” then “Male”), “trans men” (answering “Male,” then “Female”), and “nonbinary persons” (if using umbrella terminology, all additional answers which differ and do not fit into binary categorizations). This disaggregation is useful in data collection because it accurately denotes the patient’s gender as indicated by self-report. It also enables providers to offer medically relevant testing and services based on AGAB (eg, pap smears and prostate exams) and organ inventory (see Additional Considerations). Best practice recommendations for screening of transgender patients should be individualized based on organ history and cumulative exposure to hormones.195 Implementation of these goals is facilitated by accurate SOGI documentation in the EHR, but administrators should be cautious of being overreliant on automated screening rules in any setting.196

The 2-step process leads to an increased ascertainment of transgender status.183,197 Cisgender and transgender persons understand the 2-step thoroughly and in a manner that makes for more complete and more accurate data analytics.192,193,198–200 The UCSF Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, Fenway Health in Boston, the Mayo Clinic, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention all recommend using some form of the 2-step process.201 Anecdotally, it has been mentioned that some individuals dislike the 2-step process. However, in the authors’ experience, this is usually because the reasoning behind asking the questions has not be adequately explained to the patient.193 In one author’s experience (C.A.K.), discussion of accuracy of data collection and what that data collection could be used for (for instance, to indicate correct reference ranges for medical testing), followed by discussion of privacy standards, ameliorated any distrust of the 2-step process.

To highlight the limitations of current EHR data capture, we examined the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-III (MIMIC-III) database, a de-identified database of the EHRs of over 46 000 emergency department patients.202 “Gender” in the system is defined as the “genotypical sex of the patient,” which can be analyzed as meaning AGAB.203 This is inaccurate, as (1) the patients were not mass genotyped and (2) investigation of clinical notes regarding persons labeled as transgender revealed that this was the correct AGAB about 54% of the time. Identification by ICD–Ninth Revision–Clinical Modification codes in the diagnostics table reveals that only 46% of patients identified as transgender in notes were identified as such by ICD codes.204–207 This may be due to a history (and current reality) of health insurance denials for trans persons, meaning that providers adapted to using non–trans-related codes to avoid treatments being flagged as trans care.208

To find out which patients were transgender men, transgender women, or nonbinary persons was difficult, as it required manual full review of all patients’ charts. No nonbinary persons were detected, but this could reflect patient discomfort disclosing their identity or the decision to report a binary trans identity to ease access to desired care.183 Alternatively, it might indicate that whoever entered the notes failed to correctly codify disclosed identities.183 If we assume that all transgender persons in the MIMIC-III sample were trans men or trans women, correct pronouns were used <40% of the time in notes.204,205 It is extremely likely that many transgender persons were not identified at all, as many do not disclose their status as transgender.1

ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

A number of proposals related to transgender data collection protocols include sections calling for organ inventories and karyotyping.209–211 However, there is little discussion considering wide implementation of such systems.210 Karyotyping can be performed relatively easily, but is omitted from most extant SOGI vocabularies, with atypical karyotype results tracked under disease or disorder hierarchies or on a “problem list.”

Organ inventories using a presence/absence system are effective in showcasing differences in anatomy quickly and can display more medically salient information than a person’s gender identity or AGAB alone.212 Some implementations permit addition of free-text comments to document pertinent anatomical details.213 All patients can benefit from usage of organ inventories, regardless of transgender status.

The difficulty with clinical decision making based on purely presence- or absence-based organ inventories lies in the plethora of possible permutations and health risk profiles associated with anatomical features, of which medical providers might not be aware. For instance, organs and tissues are oftentimes not clearly demarcated (eg, in ovotesticular tissue), some anatomical features may develop unexpectedly, some organs or tissues might be partially present in certain situations, and some organ combinations might be unanticipated. For instance, persons assigned female at birth persons have shown some evidence of prostatic tissue growth following extended testosterone therapy.214 There may also be difficulties representing chest cancer risks following many forms of chest reconstruction or contouring in individuals assigned female at birth.215,216 This can be a serious issue if an individual has a BRCA mutation or other familial cancer syndrome.217 Procedures like penis-preserving vaginoplasty or vagina-preserving phalloplasty218 may contradict binarist systems that do not consider it possible for an individual to have a penis and vagina simultaneously.

Therefore, usage of a modifiable presence and absence system with integrated anatomical terminology (such as that seen in SNOMED CT) offers a reasonable entry point. The patient would be provided a list of common organs to consider, with presence, absence, and something else options for each. At the bottom of the list, there would be a place to clarify the “something else” selections and to indicate any additional presence and absence data not included in the list. Following this, a provider or administrator would enter the information into the EHR, which could then be transformed into an image of the body with present and absent organs highlighted appropriately and with text notes included in full. Such information could be assessed quickly visually and be integrated easily into existing clinical workflows. A brief discussion of how this workflow could be tested and rolled out is included in Supplementary Appendix A, Supplement A.

Gender identity and AGAB questions are important to preserve alongside organ inventory, as organ status cannot always easily be ascertained. There are cases wherein a patient’s privacy should be respected, and cases in which invasive procedures may be required to “check” for particular organ statuses. Patients may not remember particular surgical and organ histories, be aware of them, or necessarily understand the associated vocabulary. This is pertinent to consider when caring for intersex persons, who may have had medically unnecessary surgeries performed on them without their knowledge,219–222 as well as when considering general language barriers in health care.223–225 Having both systems side by side reduces the chance for medical error.

In addition to organ inventories, karyotyping (and related genetic laboratory techniques) may be important to showcase when considering the impacts of certain chromosomal conditions.226–228 However, while karyotyping can be useful in select cases, it is ultimately less informative than other inventories that have been proposed. Karyotyping should only be performed or recorded at the discretion of the patient, involve full privacy protections, and should only be considered alongside other data for prognostics and diagnostics.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In part owing to the absence of trans voices leading trans research teams, cisgender researchers doing trans research often fail to consider the ethical and material implications of their study designs, methods, and underlying assumptions.51,60,66,77,229–240 These researchers, and the informaticists who codify their assumptions, have contributed and continue to contribute to the epidemics of transphobic violence we see today.1,3,10,12,14,52,55,241–245

The 2-step validation process proposed above meets the needs of patients, clinicians, and researchers, and is preferred by all 3 groups.138,157,192 We therefore ask the American Medical Informatics Association and its members to endorse the 2-step method presented in Figure 3 as a starting point for collecting gender-related information in EHRs. It is important to carefully select the options provided in coordination with local gender-diverse communities to avoid anything inaccurate, confusing, pathologizing, transphobic, or intersexphobic. This involvement is vital to ensure locally relevant data collection, but also to afford community members the opportunity to be active participants in their own health. An outline of some identities to consider as a starting point is available as part of the additional supplementary tables. We also call for more research into ethical implementation of organ inventories, hormone inventories, and karyotyping in general medical settings and in EHR systems.

Further, cultural considerations should inform procedural aspects of data collection, including physical location and employee training. Financial support for transgender participation in coordinated, multidisciplinary community advisory boards and employee-based medical coding standards boards within healthcare-affiliated organizations to center the needs of trans persons in the EHR and improve clinical decision making is a critical next step to achieve data-driven, gender-affirming care.

FUNDING

TS was supported by grant number T32HS000029 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HT was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality Grant Number K12-HS-026385 and the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant number 5R25DA035692-08. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and those of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The other authors received no specific funding for this work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

CK conceived the research idea and was the primary author of the manuscript. AE, FA, HT, TS, TG, LH, ZD, RQ, AR, EG, OD, EL, EP, SS, and RK contributed several critical revisions and provided significant feedback on discussed systems. AE performed the single analysis regarding the U.S. Transgender Survey data in footnote 10, covered under the auspices of her Institutional Review Board at the University of Southern California. EG designed Figure 1. SS designed Figures 2 and 3. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. CK performed analyses using the MIMIC-III database, which were published in prior work and did not specially require Institutional Review Board approval (all records therein are de-identified). A CITI training course (entitled “Data or Specimens Only Research”) was required and taken in order to gain access to the database.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online .

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

No new data were generated or analyzed in support of this piece. Requests for 2015 United States Transgender Survey data can be made here: https://www.ustranssurvey.org/data-requests. Information about requesting access to MIMIC-III records can be found at https://mimic.physionet.org/gettingstarted/access/.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This document adheres to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Special thanks to the following individuals for their critical assistance in this work: Judith W. Dexheimer, Laur Bereznai, and Os Keyes.

REFERENCES

- 1. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, et al. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. 2016. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2020.

- 2. Roberts TK, Fantz CR. Barriers to quality health care for the transgender population. Clin Biochem 2014; 47 (10–11): 983–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Suess Schwend A. Trans health care from a depathologization and human rights perspective. Public Health Rev 2020; 41: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kcomt L, Gorey KM, Barrett BJ, et al. Healthcare avoidance due to anticipated discrimination among transgender people: a call to create trans-affirmative environments. SSM Popul Health 2020; 11: 100608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wills M. A history of transphobia in the medical establishment. 2020. https://daily.jstor.org/a-history-of-transphobia-in-the-medical-establishment/. Accessed May 6, 2021.

- 6. Serano J. Trans people still disordered in DSM. Social Text. 2013. https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/trans-people-still-disordered-in-dsm/. Accessed May 5, 2021.

- 7. Whalen K. (In)validating transgender identities: progress and trouble in the DSM-5. https://www.thetaskforce.org/invalidating-transgender-identities-progress-and-trouble-in-the-dsm-5/. Accessed May 5, 2021.

- 8. GLAAD Media Reference Guide. 10th ed. https://www.glaad.org/sites/default/files/GLAAD-Media-Reference-Guide-Tenth-Edition.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2021.

- 9. Davy Z. The DSM-5 and the politics of diagnosing transpeople. Arch Sex Behav 2015; 44 (5): 1165–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Inch E. Changing minds: the psycho-pathologization of trans people. Int J Ment Health 2016; 45 (3): 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ahmed S. Complaint as diversity work. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JQ_1kFwkfVE. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- 12. Ashley F. The misuse of gender dysphoria: toward greater conceptual clarity in transgender health. Perspect Psychol Sci 2019. Nov 20 [E-pub ahead of print]. doi:10.1177/1745691619872987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Winters K. Ten reasons why the transvestic disorder diagnosis in the DSM-5 Has Got to Go. 2010. https://gidreform.wordpress.com/2010/10/16/ten-reasons-why-the-transvestic-fetishism-diagnosis-in-the-dsm-5-has-got-to-go/. Accessed August 10, 2021.

- 14. Lev AI. Disordering gender identity: gender identity disorder in the DSM-IV-TR. J Psychol Hum Sex 2006; 17 (3–4): 35–69. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khoury B, Langer EJ, Pagnini F. The DSM: mindful science or mindless power? A critical review. Front Psychol 2014; 5: 602. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Castro-Peraza ME, García-Acosta JM, Delgado N, et al. Gender identity: the human right of depathologization. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16 (6): 978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McNabb C. Nonbinary Gender Identities: History, Culture, Resources. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rowson EK. The effeminates of early Medina. J Am Orient Soc 1991; 111 (4): 671. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Francis AG. On a Romano-British castration clamp used in the rights of cybele. Proc R Soc Med 1926; 19 (Sect Hist Med): 95–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burton R. KAMA Sutra: The Original English Translation by Sir Richard Francis Burton. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Musaicum Books; 2017.

- 21. Cassius D. Roman History, Volume I: Books 1-11. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1914. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kronk C, Dexheimer J. An Ontology-Based Review of Transgender Literature: Revealing a History of Medicalization and Pathologization; 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23. Caldwell C, Keshavan MS. Schizophrenia with secondary transsexualism. Can J Psychiatry 1991; 36 (4): 300–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Calnen T. Gender identity crises in young schizophrenic women. Perspect Psychiatr Care 1975; 13 (2): 83–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kampik E, Müller N, Soyka M. [Manifestation of schizophrenic psychosis in a transsexual patient following surgical sex change]. Nervenarzt 1989; 60 (6): 361–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lothstein LM, Roback H. Black female transsexuals and schizophrenia: a serendipitous finding? Arch Sex Behav 1984; 13 (4): 371–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brown JRWC. Paraphilias: sadomasochism, fetishism, transvestism and transsexuality. Br J Psychiatry 1983; 143: 227–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blancard R. Clinical observations and systematic studies of autogynephilia. J Sex Marital Ther 1991; 17 (4): 235–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Modestin J, Ebner G. Multiple personality disorder manifesting itself under the mask of transsexualism. Psychopathology 1995; 28 (6): 317–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brenner I. On trauma, perversion, and “multiple personality.” J Am Psychoanal Assoc 1996; 44 (3): 785–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Murray JF. Borderline manifestations in the Rorschachs of male transsexuals. J Pers Assess 1985; 49 (5): 454–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marantz S, Coates S. Mothers of boys with gender identity disorder: a comparison of matched controls. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991; 30 (2): 310–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hartmann U, Becker H, Rueffer-Hesse C. Self and gender: narcissistic pathology and personality factors in gender dysphoric patients. Preliminary results of a prospective study. Int J Transgenderism 1997; 1. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Marks IM, Mataix-Cols D. Four-year remission of transsexualism after comorbid obsessive–compulsive disorder improved with self-exposure therapy: case report. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 171: 389–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Walsh RJ, Krabbendam L, Dewinter J, et al. Brief report: gender identity differences in autistic adults: associations with perceptual and socio-cognitive profiles. J Autism Dev Disord 2018; 48 (12): 4070–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brown LXZ. Gendervague: at the intersection of autistic and trans experiences. https://www.aane.org/gendervague-intersection-autistic-trans-experiences/. Accessed May 6, 2021.

- 37.ASAN Joint statement on the death of Kayden Clarke. 2016. https://autisticadvocacy.org/2016/02/asan-joint-statement-death-of-kayden-clarke/. Accessed May 6, 2021.

- 38. Burns K. How our society harms trans people who are also autistic. 2017. https://medium.com/the-establishment/how-our-society-harms-trans-people-with-autism-9766edc6553d. Accessed May 6, 2021.

- 39. Adams N, Liang B. Trans and Autistic: Stories from Life at the Intersection. London, Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Landén M, Rasmussen P. Gender identity disorder in a girl with autism: a case report. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997; 6 (3): 170–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Carlile A. The experiences of transgender and non-binary children and young people and their parents in healthcare settings in England, UK: interviews with members of a family support group. Int J Transgend Health 2020; 21 (1): 16–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kula K, Słowikowska-Hilczer J. [Consequences of disturbed sex-hormone action in the central nervous system: behavioral, anatomical and functional changes]. Neurol Neurochir Pol 2003; 37 (Suppl 3): 19–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Steiner BW. Gender Dysphoria: Development, Research, Management. New York, NY: Springer; 1985.

- 44. Jasuja GK, de Groot A, Quinn EK, et al. Beyond gender identity disorder diagnoses codes: an examination of additional methods to identify transgender individuals in administrative databases. Med Care 2020; 58 (10): 903–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bartnik P, Kacperczyk-Bartnik J, Próchnicki M, et al. Does the status quo have to remain? The current legal issues of transsexualism in Poland. Adv Clin Exp Med 2020; 29 (3): 409–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Joseph A, Cliffe C, Hillyard M, et al. Gender identity and the management of the transgender patient: a guide for non-specialists. J R Soc Med 2017; 110 (4): 144–52. PMC][10.1177/0141076817696054] [28382847] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Majid DSA, Burke SM, Manzouri A, et al. Neural systems for own-body processing align with gender identity rather than birth-assigned sex. Cereb Cortex 2020; 30 (5): 2897–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. O'Neill T, Wakefield J. Fifteen-minute consultation in the normal child: Challenges relating to sexuality and gender identity in children and young people. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2017; 102 (6): 298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Why is my Provider Using Gender Dysphoria Codes?: Information for transgender, nonbinary, gender nonconforming/expansive and questioning patients. https://www.uwhealth.org/files/uwhealth/docs/gender_services/DI-165839-18_Gender_Services_Patient_Coding_Booklet.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2021.

- 50. Foer D, Rubins DM, Almazan A, Chan K, Bates DW, Hamnvik O-PR. Challenges with accuracy of gender fields in identifying transgender patients in electronic health records. J Gen Intern Med 2020; 35 (12): 3724–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Serano JM. The case against autogynephilia. Int J Transgenderism 2010; 12 (3): 176–87. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rodriguez A, Agardh A, Asamoah BO. Self-reported discrimination in health-care settings based on recognizability as transgender: a cross-sectional study among transgender U.S. citizens. Arch Sex Behav 2018; 47 (4): 973–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Glick JL, Theall KP, Andrinopoulos KM, Kendall C. The role of discrimination in care postponement among trans-feminine individuals in the U.S. National Transgender Discrimination Survey. LGBT Health 2018; 5 (3): 171–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jaffe S. LGBTQ discrimination in US health care under scrutiny. Lancet 2020; 395 (10242): 1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. McHugh PR. Surgical sex: why we stopped doing sex change operations. 2004. https://www.firstthings.com/article/2004/11/surgical-sex. Accessed January 5, 2021.

- 56. Ashley F. Science has always been ideological, you just don’t see it. Arch Sex Behav 2019; 48 (6): 1655–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Powell K, Terry R, Chen S. How LGBT+ scientists would like to be included and welcomed in STEM workplaces. Nature 2020; 586 (7831): 813–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tanenbaum TJ. Publishers: let transgender scholars correct their names. Nature 2020; 583 (7817): 493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Russell ST, Pollitt AM, Li G, Grossman AH. Chosen name use is linked to reduced depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior among transgender youth. J Adolesc Health 2018; 63 (4): 503–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Turban J. The disturbing history of research into transgender identity. Sci Am 2020. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-disturbing-history-of-research-into-transgender-identity/. Accessed January 9, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Radix AE. Addressing needs of transgender patients: the role of family physicians. J Am Board Fam Med 2020; 33 (2): 314–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hamer D. New “scientific” study on sexuality, gender is neither new nor scientific. 2016. https://www.advocate.com/commentary/2016/8/29/new-scientific-study-sexuality-gender-neither-new-nor-scientific. Accessed January 19, 2021.

- 63. Serano J. A matter of perspective: a transsexual woman-centric critique of dreger’s “scholarly history” of the Bailey controversy. Arch Sex Behav 2008; 37 (3): 491–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pickstone-Taylor SD. Children with gender nonconformity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003; 42 (3): 266; author reply 266–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bollinger A. Medical school suspends study that would have tortured transgender people for science. 2021. https://www.lgbtqnation.com/2021/02/medical-school-suspends-study-tortured-transgender-people-science/. Accessed February 5, 2021.

- 66. Baska M. Controversial trans study that “purposefully induced dysphoria” suspended over “grave” ethical concerns. PinkNews. 2021. https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2021/02/05/ucla-trans-medical-study-gender-dysphoria/. Accessed February 15, 2021.

- 67. Highleyman L. Who was Lou Sullivan? Seattle Gay News. http://sgn.org/sgnnews36_09/mobile/page30.cfm. Accessed August 10, 2021.

- 68. Bowles S. A death robbed of dignity mobilizes a community. Washington Post. 1995.https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1995/12/10/a-death-robbed-of-dignity-mobilizes-a-community/2ca40566-9d67-47a2-80f2-e5756b2753a6/. Accessed August 10, 2021.

- 69. Parsons V. Trans woman left to die with coronavirus symptoms by paramedics who “refused to treat her” because she had HIV. PinkNews. 2020. https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2020/06/01/alejandra-monocuco-trans-woman-dead-coronavirus-hiv-positive-bogota/. Accessed August 10, 2021.

- 70. Persad X. LGBTQ-inclusive data collection: a lifesaving imperative. 2019. https://assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/HRC-LGBTQ-DataCollection-Report.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2021.

- 71. Cahill SR, Makadon HJ. If they don’t count us, we don’t count: trump administration rolls back sexual orientation and gender identity data collection. LGBT Health 2017; 4 (3): 171–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Grasso C, Goldhammer H, Funk D, et al. Required sexual orientation and gender identity reporting by US health centers: first-year data. Am J Public Health 2019; 109 (8): 1111–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Suen LW, Lunn MR, Katuzny K, et al. What sexual and gender minority people want researchers to know about sexual orientation and gender identity questions: a qualitative study. Arch Sex Behav 2020; 49 (7): 2301–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Singh S, Durso LE, Tax A. The Trump administration is rolling back data collection on LGBT older adults. 2017. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/lgbtq-rights/news/2017/03/20/428623/trump-administration-rolling-back-data-collection-lgbt-older-adults/. Accessed February 3, 2021.

- 75. Turney S, Carvalho MM, Sousa ME, et al. Support transgender scientists post–COVID-19. Science 2020; 369 (6508): 1171–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kluge E-HW. Ethics in Health Care: A Canadian Focus. 1st ed. Don Mills, Canada: Pearson Canada; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bauer G, Devor A, Heinz M, et al. CPATH ethical guidelines for research involving transgender people & communities. 2019. https://cpath.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/CPATH-Ethical-Guidelines-EN.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2021.

- 78. Rao TSS, Radhakrishnan R, Andrade C. Standard operating procedures for clinical practice. Indian J Psychiatry 2011; 53 (1): 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sajdak R, Trembath L, Thomas KS. The importance of standard operating procedures in clinical trials. J Nucl Med Technol 2013; 41 (3): 231–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Hollmann S, Frohme M, Endrullat C, et al. ; Cost Action CA15110. Ten simple rules on how to write a standard operating procedure. PLoS Comput Biol 2020; 16 (9): e1008095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ewald ER, Guerino P, Dragon C, et al. Identifying Medicare beneficiaries accessing transgender-related care in the era of ICD-10. LGBT Health 2019; 6 (4): 166–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Proctor K, Haffer SC, Ewald E, et al. Identifying the transgender population in the Medicare program. Transgend Health 2016; 1 (1): 250–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Blosnich JR, Brown GR, Wojcio S, et al. Mortality among veterans with transgender-related diagnoses in the Veterans Health Administration, FY2000-2009. LGBT Health 2014; 1 (4): 269–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Canner JK, Harfouch O, Kodadek LM, et al. Temporal trends in gender-affirming surgery among transgender patients in the United States. JAMA Surg 2018; 153 (7): 609–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Collin L, Reisner SL, Tangpricha V, et al. Prevalence of transgender depends on the “case” definition: a systematic review. J Sex Med 2016; 13 (4): 613–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Oliven JF. Sexual Hygiene and Pathology: A Manual for the Physician and the Professions. 2nd ed. Lippincott; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Prince V. The “Transcendents” or “Trans” people. Int J Transgenderism 2005; 8 (4): 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Lynn MS. Definitions of terms commonly used in the transvestite-transsexual community. TV-TS Tapestry 1988; (5): 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Molina NG. A transgender dictionary. Focus San Franc Calif 1998; 13: 5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.GLAAD Media Reference Guide. 7th ed. Los Angeles, CA: GLAAD; 2008.

- 91.transgender. 2011. https://ahdictionary.com/word/search.html?q=TRANSGENDER. Accessed August 10, 2021.

- 92.Primer. 2018. https://www.translanguageprimer.org/primer/. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- 93.PFLAG National Glossary of Terms. 2021. https://pflag.org/glossary. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- 94. Olson J, Forbes C, Belzer M. Management of the transgender adolescent. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011; 165 (2): 171–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Giami A, Beaubatie E. Gender identification and sex reassignment surgery in the trans population: a survey study in France. Arch Sex Behav 2014; 43 (8): 1491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Dolan IJ, Strauss P, Winter S, et al. Misgendering and experiences of stigma in health care settings for transgender people. Med J Aust 2020; 212 (4): 150–1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ashley F. “Trans” is my gender modality: a modest terminological proposal. https://www.florenceashley.com/uploads/1/2/4/4/124439164/florence_ashley_trans_is_my_gender_modality.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2021.

- 98. Braidotti R. The uses and abuses of the sex/gender distinction in European feminist practices. In: Translating Gender. Utrecht, Netherlands: European Association for Gender Research, Education and Documentation; 5–26. https://atgender.eu/wp-content/uploads/sites/207/2015/12/Translating-Gender-2012.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- 99. Jegerstedt K. A short introduction to the use of “sex” and “gender” in the Scandinavian languages. In: Translating Gender. Utrecht, Netherlands: European Association for Gender Research, Education and Documentation; 27–8. https://atgender.eu/wp-content/uploads/sites/207/2015/12/Translating-Gender-2012.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- 100. Bahovic E. A short note on the use of “sex” and “gender” in some Slavic languages. In: Translating Gender. Utrecht, Netherlands: European Association for Gender Research, Education and Documentation 30–1. https://atgender.eu/wp-content/uploads/sites/207/2015/12/Translating-Gender-2012.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- 101. Petö A. From a “non-science” to gender analyses? Usage of sex/gender in Hungarian. In: Translating Gender. Utrecht, Netherlands: European Association for Gender Research, Education and Documentation; 61–2. https://atgender.eu/wp-content/uploads/sites/207/2015/12/Translating-Gender-2012.pdf. Accessed May. 3, 2021.

- 102. Kiuchi A. [Independent and interdependent construal of the self: the cultural influence and the relations to personality traits]. Shinrigaku Kenkyu 1996; 67 (4): 308–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Goecker D, Korte A. Sex identity disorders in children and adolescents. Kinderkrankenschwester Organ Sekt Kinderkrankenpflege 2007; 26: 330–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Tang G, Guo L, Huang X. [An epidemiological study on mental problems in adolescents in Chengdu, China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2005; 26: 878–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Council of Europe. Sex and gender. https://www.coe.int/en/web/gender-matters/sex-and-gender. Accessed May 5, 2021.

- 106. Burgess C, Kauth MR, Klemt C, et al. Evolving sex and gender in electronic health records. Fed Pract 2019; 36: 271–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gender identity and sexual orientation questions. https://grad.ucdavis.edu/admissions/admission-requirements/gender-identity-and-sexual-orientation-questions. Accessed May 5, 2021.

- 108.New Student Survey 2018. 2018. https://www.evergreen.edu/sites/default/files/NSS18-Q25-OLY-Gender.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2021.

- 109.Birth certificates. 2018. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_education/publications/teaching-legal-docs/birth-certificates/#:~:text=A%20birth%20certificate%20is%20a,documents%20an%20individual%20might%20acquire. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- 110.Editorial: Birth certificate is a legal, not a biological document. Cincinnati Enquirer. 2014. https://www.cincinnati.com/story/opinion/editorials/2014/02/13/birth-certificate-is-a-legal-not-a-biological-document/5458545/. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- 111. Shteyler VM, Clarke JA, Adashi EY. Failed assignments — rethinking sex designations on birth certificates. N Engl J Med 2020; 383 (25): 2399–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.What do we mean by “sex” and “gender”? 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20140923045700/http://www.who.int/gender/whatisgender/en. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- 113.State-by-state overview: rules for changing gender markers on birth certificates. 2017. http://transgenderlawcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Birth-Cert-overview-state-by-state.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- 114.Ten strategies for creating inclusive health care environments for LGBTQIA+ people. 2021. https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Ten-Strategies-for-Creating-Inclusive-Health-Care-Environments-for-LGBTQIA-People-Brief.pdf. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- 115. Schreiber M, Ahmad T, Scott M, et al. The case for a Canadian standard for 2SLGBTQIA+ medical education. CMAJ 2021; 193 (16): E562–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Korpaisarn S, Safer JD. Gaps in transgender medical education among healthcare providers: a major barrier to care for transgender persons. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2018; 19 (3): 271–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA 2011; 306 (9): 971–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Liang JJ, Gardner IH, Walker JA, et al. Observed deficiencies in medical student knowledge of transgender and intersex health. Endocr Pract 2017; 23 (8): 897–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Li X. Advocates express need for increased research in transgender health care. 2017. https://dailybruin.com/2017/06/11/advocates-express-need-for-increased-research-in-transgender-health-care. Accessed January 29, 2021.

- 120. Cuerda C, Schneider SM, Van Gossum A. Clinical nutrition education in medical schools: results of an ESPEN survey. Clin Nutr 2017; 36 (4): 915–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Melber DJ, Teherani A, Schwartz BS. A comprehensive survey of preclinical microbiology curricula among US Medical Schools. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63 (2): 164–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Stroumsa D. The state of transgender health care: policy, law, and medical frameworks. Am J Public Health 2014; 104 (3): e31–e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Lam K. Some Americans are denied “lifesaving” health care because they are transgender. USA Today. 2018. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2018/12/11/transgender-health-care-patients-advocates-call-improvements/1829307002/. Accessed January 29, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 124. Christensen J. Puberty blockers can be “life-saving” drugs for trans teens, study shows. CNN. 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/01/23/health/transgender-puberty-blockers-suicide-study/index.htmlAccessed January 29, 2021.

- 125. Winter S, Conway L. How many trans people are there? A 2011 update incorporating new data. 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20141205022609/http://web.hku.hk/∼sjwinter/TransgenderASIA/paper-how-many-trans-people-are-there.htm. Accessed August 10, 2021.

- 126. Johnson N. LGBTQ health education: where are we now? Acad Med J Med 2017; 92 (4): 432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. DeVita T, Bishop C, Plankey M. Queering medical education: systematically assessing LGBTQI health competency and implementing reform. Med Educ Online 2018; 23 (1): 1510703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Snelgrove JW, Jasudavisius AM, Rowe BW, et al. Completely out-at-sea” with “two-gender medicine”: a qualitative analysis of physician-side barriers to providing healthcare for transgender patients. BMC Health Serv Res 2012; 12: 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. MacKinnon KR, Ross LE, Rojas Gualdron D, et al. Teaching health professionals how to tailor gender-affirming medicine protocols: a design thinking project. Perspect Med Educ 2020; 9 (5): 324–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. MacKinnon KR, Kia H, Rai N, et al. Integrating trans health knowledge through instructional design: preparing learners for a continent – not an island – of primary care with trans people. Educ Prim Care 2021; 32 (4): 198–201. doi:10.1080/14739879.2021.1882885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, et al. Injustice at every turn: a report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. 2011. https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2021.

- 132. Donald CA, DasGupta S, Metzl JM, et al. Queer Frontiers in medicine: a structural competency approach. Acad Med J Med 2017; 92 (3): 345–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Willging C, Gunderson L, Shattuck D, et al. Structural competency in emergency medicine services for transgender and gender non-conforming patients. Soc Sci Med 2019; 222: 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Zaidi D. Transgender health in an age of bathroom bills. Acad Med 2018; 93 (1): 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Cruz TM. Perils of data-driven equity: safety-net care and big data’s elusive grasp on health inequality. Big Data Soc 2020; 7 (1): 205395172092809. [Google Scholar]

- 136. Price D. Bad gender measures & how to avoid them. 2018. https://medium.com/@devonprice/bad-gender-measures-how-to-avoid-them-23b8f3a503a6. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 137. Tate CC, Youssef CP, Bettergarcia JN. Integrating the study of transgender spectrum and cisgender experiences of self-categorization from a personality perspective. Rev Gen Psychol 2014; 18 (4): 302–12. [Google Scholar]

- 138. Puckett JA, Brown NC, Dunn T, et al. Perspectives from transgender and gender diverse people on how to ask about gender. LGBT Health 2020; 7 (6): 305–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Tudisco J. Survey says “woman, man, or transgender” - how non-inclusive survey design erases our existence. https://www.ihc.ucsb.edu/survey-says-woman-man-or-transgender-how-non-inclusive-survey-design-erases-our-existence/. Accessed January 8, 2021.

- 140.Transgender FAQ. https://www.hrc.org/resources/transgender-faq. Accessed January 22, 2021.

- 141.PFLAG National Glossary of Terms. https://pflag.org/glossary. Accessed January 22, 2021.

- 142. Lynsey G. Watching Porn: and Other Confessions of an Adult Entertainment Journalist. New York, NY: Abrams Books; 2017.

- 143. Escoffier J. Imagining the she/male: pornography and the transsexualization of the heterosexual male. Stud Gend Sex 2011; 12 (4): 268–81. [Google Scholar]

- 144. Carrera-Fernández MV, DePalma R. Feminism will be trans-inclusive or it will not be: why do two cis-hetero woman educators support transfeminism? Sociol Rev 2020; 68 (4): 745–62. [Google Scholar]

- 145. Ritzer G, ed. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 146.u/redesckey. Can we please stop using “transmasculine” and “transfeminine”? r/lgbt. 2019. https://www.reddit.com/r/lgbt/comments/aql7sy/can_we_please_stop_using_transmasculine_and/. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- 147.Dark J. I am Not Transmasculine or Transfeminine. 2018. https://medium.com/@whoaitsjoan/i-am-not-transmasculine-or-transfeminine-9fe0791afa95. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- 148.@hologramvin. Alternatives to “AFAB” and “AMAB.” Trans Style Guide. 2019. https://medium.com/@transstyleguide/alternatives-to-afab-and-amab-d7cf8fe20a72. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- 149. Mitchell G. Some terms are better than others. 2017. https://transsubstantiation.com/some-terms-are-better-than-others-603827adb9b7. Accessed January 22, 2021.

- 150. Mere A. 64 terms that describe gender identity and expression. 2019. https://www.healthline.com/health/different-genders. Accessed January 22, 2021.

- 151. Bailar S. Terminology. 2015. https://pinkmantaray.com/terminology. Accessed January 22, 2021.

- 152. Kang A, Aizen JM, Cohen AJ, et al. Techniques and considerations of prosthetic surgery after phalloplasty in the transgender male. Transl Androl Urol 2019; 8 (3): 273–82. PMC][10.21037/tau.2019.06.02] [31380234] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Smith KP, Madison CM, Milne NM. Gonadal suppressive and cross-sex hormone therapy for gender dysphoria in adolescents and adults. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther 2014; 34 (12): 1282–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Valera RJ, Sawyer RG, Schiraldi GR. Perceived health needs of inner-city street prostitutes: a preliminary study. Am J Health Behav 2001; 25 (1): 50–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Lee C, Basaria S. Syncope in a transsexual male. J Androl 2006; 27 (2): 164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Fonseca S. Designing forms for gender diversity and inclusion. 2017. https://uxdesign.cc/designing-forms-for-gender-diversity-and-inclusion-d8194cf1f51. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 157. Bauer GR, Braimoh J, Scheim AI, Dharma C. Transgender-inclusive measures of sex/gender for population surveys: mixed-methods evaluation and recommendations. PLoS One 2017; 12 (5): e0178043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Holzberg J, Ellis R, Virgile M. Assessing the feasibility of asking about gender identity in the current population survey: results from Focus Groups with members of the transgender population. 2017. https://www.bls.gov/osmr/research-papers/2017/pdf/st170200.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2021.

- 159. Ke M. How to make an LGBTQ+ inclusive survey. 2020. https://uxdesign.cc/how-to-make-an-lgbtq-inclusive-survey-bfd1d801cc21. Accessed January 11, 2021.

- 160. Stock K. Changing the concept of “woman” will cause unintended harms. 2018. https://www.economist.com/open-future/2018/07/06/changing-the-concept-of-woman-will-cause-unintended-harms. Accessed January 8, 2021.

- 161. Jenkins K. Amelioration and inclusion: gender identity and the concept of woman. Ethics 2016; 126 (2): 394–421. [Google Scholar]

- 162. Holston-Zannell LB. Black trans women are being murdered in the streets. Now the Trump administration wants to turn us away from shelters and health care. 2019. https://www.aclu.org/blog/lgbt-rights/transgender-rights/black-trans-women-are-being-murdered-streets-now-trump. Accessed January 8, 2021.

- 163. Spiel K, Haimson O, Lottridge D. How to do better with gender on surveys: a guide for HCI researchers. ACM Interact. 2019: 26. https://interactions.acm.org/archive/view/july-august-2019/how-to-do-better-with-gender-on-surveys?fbclid=IwAR38mqjxkk3svBMPKDE8c8WHWlpk0ttHMv42G_23fLFoNe35Ao3vlLjNp-M. Accessed October 1, 2010.

- 164.Transgender: using words wisely. 2018. https://emmanuelle.coach/transgender-using-words-wisely/. Accessed January 22, 2021.

- 165. Lopez G. Why you should always use “transgender” instead of “transgendered.” Vox. 2015. https://www.vox.com/2015/2/18/8055691/transgender-transgendered-tnr. Accessed January 22, 2021.

- 166. Serano J. Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity. 2nd ed. Berkeley, CA: Seal Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 167.Gender identity definitions. https://mmt.org/gender-identity-definitions. Accessed January 22, 2021.

- 168.Providing health care for transgender and intersex veterans. 2018. https://www.albuquerque.va.gov/docs/ProvidingHealthCareforTransgenderandIntersexVeterans.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2021.

- 169.Nonbinary? Intersex? 11 U.S. states issuing third gender IDs. Reuters. 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-us-lgbt-lawmaking/nonbinary-intersex-11-u-s-states-issuing-third-gender-ids-idUSKCN1PP2N7. Accessed January 8, 2021.

- 170.Haug O. The State Department Will Finally Allow "X" Gender Marker on Passports. 2021. https://www.them.us/story/biden-state-department-allows-x-gender-marker-passports. Accessed July 6, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 171.Intersex is not a gender identity, and the implications for legislation. 2012. https://ihra.org.au/17680/intersex-characteristics-not-gender-identity/. Accessed January 19, 2021.

- 172.Intersex data collection: your guide to question design. https://interactadvocates.org/intersex-data-collection/. Accessed May 5, 2021.

- 173.de la Cretaz B. American Medical Association Recommends Removing Sex From Birth Certificates. 2021. https://www.them.us/story/american-medical-association-recommends-removing-sex-from-birth-certificates. Accessed August 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 174. Bhatia A, , FerreiraLZ, , BarrosAJD, , Victora CG.. Who and where are the uncounted children? Inequalities in birth certificate coverage among children under five years in 94 countries using nationally representative household surveys. Int J Equity Health 2017; 16 (1): 148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.More inclusive care for transgender patients using epic. 2017. https://www.epic.com/epic/post/inclusive-care-transgender-patients-using-epic. Accessed May 5, 2021.

- 176. Koehle H. Trans inclusive health records. 2020. https://hankoehle.com/2020/08/06/trans-care-begins-at-the-software/Accessed October 2, 2020.

- 177. Kapusta SJ. Misgendering and its moral contestability. Hypatia 2016; 31 (3): 502–19. [Google Scholar]

- 178.@morganastra. pronoun.is. 2019. https://github.com/witch-house/pronoun.is. Accessed August 10, 2021.

- 179. Kronk CA, Dexheimer JW. Creation and evaluation of the Gender, Sex, and Sexual Orientation (GSSO) Ontology. Pediatrics 2021; 147 (3 Meeting Abstract): 602–3.

- 180.Personal pronouns - reported. 2018. https://loinc.org/90778-2/. Accessed January 21, 2021.

- 181.Cassian. Gender Census 2020: Worldwide Report. 2020. https://gendercensus.com/results/2020-worldwide/. Accessed January 22, 2021.

- 182.Cassian. Gender Census 2021: Worldwide Report. 2021. https://gendercensus.com/results/2021-worldwide/. Accessed May 5, 2021.

- 183. Thompson HM. Patient perspectives on gender identity data collection in electronic health records: an analysis of disclosure, privacy, and access to care. Transgend Health 2016; 1 (1): 205–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184. Dunne MJ, Raynor LA, Cottrell EK, et al. Interviews with patients and providers on transgender and gender nonconforming health data collection in the electronic health record. Transgend Health 2017; 2 (1): 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185. Blosnich JR, Cashy J, Gordon AJ, et al. Using clinician text notes in electronic medical record data to validate transgender-related diagnosis codes. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018; 25 (7): 905–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186. Goldenberg T, Reisner SL, Harper GW, et al. State‐level transgender‐specific policies, race/ethnicity, and use of medical gender affirmation services among transgender and other gender‐diverse people in the United States. Milbank Q 2020; 98 (3): 802–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187. Lopez CM, Solomon D, Boulware SD, et al. Trends in the use of puberty blockers among transgender children in the United States. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2018; 31 (6): 665–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]