Abstract

Luteolin (LT) is a natural polyphenol water-insoluble compound. LT-loaded nanovesicles (NVs) were prepared by using the solvent evaporation method. LT-NVs were prepared using cholesterol, phosphatidylcholine, span 60, and labrasol in a different composition. The prepared LT-NVs were evaluated for encapsulation efficiency, in vitro drug release, and permeation study. The optimized LT-NVs were further evaluated for antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity using the lung cancer cell line. LT-NVs showed nanometric size (less than 300 nm), an optimum polydispersibility index (less than 0.5), and a negative zeta potential value. The formulations also showed significant variability in the encapsulation efficiency (69.44 ± 0.52 to 83.75 ± 0.35%) depending upon the formulation composition. The in vitro and permeation study results revealed enhanced drug release as well as permeation profile. The formulation LT-NVs (F2) showed the maximum drug release of 88.28 ± 1.13%, while pure LT showed only 20.1 ± 1.21% in 12 h. The release data revealed significant variation (p < 0.001) in the release pattern. The permeation results also depicted significant (p < 0.001) enhancement in the permeation across the membrane. The enhanced permeation from LT-NVs was achieved due to the enhanced solubility of LT in the presence of the surfactant. The antioxidant activity results proved that LT-NVs showed greater activity compared to pure LT. The cytotoxicity study showed lesser IC50 value from LT-NVs than the pure LT. Thus, it can be concluded that LT-NVs are a natural alternative to the synthetic drug in the treatment of lung cancer.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide in men and the third most common in women, with 2.09 million total new cases in 2018.1,2 It was the leading cause of cancer-related death with 1.76 million deaths worldwide in 2018, and the number may increase to 3 million by the year 2035.3 There are a number of synthetic anticancer drugs like gefitinib, afatinib, brigatinib, osimertinib, and paclitaxel that are used to treat this disease. The major problem associated with synthetic drugs is their poor solubility, peripheral neuropathy, and hematological toxicity.4

Nanoformulations have the potential to fix some of the current medical problems. These delivery systems can help to target the therapeutic agent to cancerous tissues as well as to the cancer diagnosis.5−7 Different nanoformulations like lipid nanoparticles, polymeric nanoparticles, nanomicelles, nanovesicles, and nano-lipid-drug conjugates have been reported for anticancer delivery using different routes of administration. Among these, nanovesicles (NVs) have several advantages over other conventional delivery systems. These delivery systems have shown enhanced solubility of poorly soluble drugs with improved pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic activities. The limited aqueous solubility of drugs limits their therapeutic activity, so entrapment of drugs into NVs is a better alternative to deliver the insoluble drugs.8 The use of different nano-sized lipid vesicles (liposomes, niosomes, transferosomes, cubosomes, and chitosomes) in the treatment of systemic delivery is acceptable due to their high permeation profile. The nano-lipid vesicles can encapsulate hydrophilic and lipophilic drugs. There are a number of different vesicular delivery systems like docetaxel liposomes,9 bortezomib liposomes,10 morusin niosomes,11 galangin niosomes,12 and cyanocobalamin ultra-flexible lipid vesicles.13 These delivery systems showed enhanced in vitro and in vivo results.

Luteolin (LT) is a natural flavonoid, having the chemical formula 3,4,5,7-tetrahydroxy flavone. It is available in different plant species like fruits and vegetables. LT has been widely used in the treatment of different diseases, including cancers. It has shown greater potential in the treatment of lung cancer.14,15 It has been found effective against cancer cell proliferation by inducing cell death and suppressing cell migration.16 The induction of apoptosis leads to activation of caspase-3 and -9, altering the phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase enzymes and activated protein kinase.17,18 The poor water solubility of LT (50.6 μg/mL) leads to poor bioavailability and hampers its therapeutic efficacy.19

The main objective of the present study is to develop and optimize luteolin nanovesicles (LT-NVs) by the thin-film hydration method. The formulations were prepared using cholesterol, lipids, and surfactants. The formulations were assessed for different physicochemical parameters, and the selected formulation was evaluated for cell viability study against the lung cancer cell line.

Results and Discussion

Luteolin-loaded lipid nanovesicles (LT-NVs) were prepared by the thin-film evaporation hydration method (Table 1). Luteolin is a water-insoluble drug and is entrapped in the lipid vesicles to enhance solubility as well as in vitro properties. It is composed of cholesterol, span 60, phosphatidylcholine, and labrasol. Cholesterol helps to achieve the rigidity of the vesicle walls20 and also enhances the stability by altering its phase transition behavior; span 60 protects the drug from proteolytic enzymes to provide higher stability.11,21 In this study, a fixed quantity of cholesterol was used, and, furthermore, the concentration of phosphatidylcholine was changed. At a lower ratio of cholesterol and phosphatidylcholine, stable vesicles do not form. The stable size of vesicles was found at ratios of 1:8 and 1:9. Therefore, these ratios were finally selected to prepare the formulation using the surfactant span 60 and labrasol alone as well as in combination. The combination of span 60 and labrasol showed a better result than the single surfactant.

Table 1. Formulation Composition of the Prepared Luteolin Nanovesicles (LT-NVs).

| formulation | cholesterol (%, w/v) | phosphatidylcholine (%, w/v) | span 60 (%, w/v) | labrasol (%, w/v) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| F2 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| F3 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| F4 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| F5 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| F6 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| F7 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 1.0 | |

| F8 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

Characterization

Vesicle Size, Polydispersibility Index (PDI), and Zeta Potential (ZP)

The prepared LT-NVs were found to be in the nanometric size range of 373 ± 4.65 nm (F2, Figure 1) to 459 ± 4.11 nm (F7) (Table 2). The difference in size was observed for the prepared LT-NVs due to the variation in the formulation composition. The vesicle size trend was found to follow the order F7 > F5 > F4 > F6 > F8 > F1 > F3 > F2. The formulation prepared with span 60 alone (F7) showed a larger vesicle size (459 ± 4.11 nm) due to the longer alkyl chain length. Formulation F2 prepared with the surfactant blend span 60 and labrasol (6:4) showed a smaller size. The vesicle size of formulation F3 was also found to be closer to that of formulation F2. The size of the formulation prepared with span 60 and labrasol (4:6) was found to be 386 ± 5.54 nm. The ideal size of vesicles for the cellular uptake via the endocytic pathway is 100–500 nm; our prepared LT-NVs are found in the desired range of internalization by cancer cells.22,23 The smaller vesicle size provides a greater effective surface area for the drug absorption. Due to the smaller size, the solubility of the drug increases and the drug absorption enhances.

Figure 1.

Vesicle size of luteolin-loaded nanovesicles (LT-NVs, F2).

Table 2. Characterization Results of Luteolin Nanovesicles (LT-NVs)a.

| formulation | vesicle size (nm) | PDI | zeta potential (mV) | encapsulation efficiency (%) | drug release (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 404 ± 3.18 | 0.32 ± 0.08 | –11.12 ± 0.34 | 79.25 ± 1.22 | 79.6 ± 1.66 |

| F2 | 373 ± 4.65 | 0.28 ± 0.07 | –14.82± 0.54 | 83.75 ± 0.35 | 88.3 ± 1.13 |

| F3 | 386 ± 5.54 | 0.41 ± 0.12 | –12.56 ± 0.95 | 71.11 ± 0.51 | 85.9 ± 1.45 |

| F4 | 431 ± 2.23 | 0.38 ± 0.05 | –8.22 ± 1.21 | 76.00 ± 1.05 | 78.7 ± 1.31 |

| F5 | 442 ± 3.28 | 0.44 ± 0.02 | –10.56 ± 0.43 | 72.74 ± 0.32 | 77.9 ± 2.26 |

| F6 | 418 ± 1.78 | 0.39 ± 0.06 | –16.43 ± 0.76 | 70.48 ± 0.85 | 73.6 ± 1.67 |

| F7 | 459 ± 4.11 | 0.31 ± 0.02 | –16.16 ± 0.89 | 78.42 ± 0.56 | 67.2 ± 0.78 |

| F8 | 413 ± 3.38 | 0.42 ± 0.11 | –19.36 ± 1.13 | 69.44 ± 0.52 | 75.2 ± 1.46 |

| pure LT | 20.1 ± 0.59 |

The study was performed in triplicate, and data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3).

The zeta potential on the vesicle is very important for cellular interaction and uptake. The negative or positively charged particles are more readily internalized as compared to uncharged particles. The prepared LT-NVs (F2) showed a surface charge of −14.82 ± 0.54 mV (Figure 2). These values are found to be ideal for the stability of the formulation; the value ± 30 mV is standard for the stability.24 The repulsion forces occurring from the surface charge overcome the van der Waals attractive forces between them and help in achieving stability. The PDI of the prepared LT-NVs was found to be less than 0.5. Thus, a value less than 0.7 is considered suitable for the delivery systems.24 The low value indicates greater uniformity of the dispersion.

Figure 2.

Zeta potential image showing the surface charge of luteolin-loaded nanovesicles (LT-NVs, F2).

Encapsulation Efficiency

The encapsulation efficiency of the prepared formulations was evaluated to check the loading of LT in the lipid vesicles (Table 2). LT is a lipophilic drug, so the prepared LT-NVs showed higher encapsulation. The formulation prepared with a surfactant blend showed higher encapsulation than the individual surfactant. The maximum encapsulation efficiency shown by formulation F2 was 83.75 ± 3.45%, and the lowest shown by formulation F8 prepared with labrasol as surfactant was 69.44 ± 2.51%. Formulation F7 prepared with surfactant SP 60 also showed a significantly (p < 0.05) higher encapsulation (78.42 ± 1.45%) than that prepared with the surfactant (labrasol; 69.44 ± 0.52). The formulation prepared with span 60 showed the highest encapsulation among all compositions. The higher encapsulation with the higher concentration of span 60 is due to the longer alkyl chain length and phase transition temperature. No significant difference in the encapsulation efficiency was observed between formulations F2 and F3.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

LT-NVs (F2) were evaluated for surface morphology. The image (Figure 3) shows spherical-shaped vesicles with a smooth surface. There is a distinct thin bilayer of lipid shown in the image, which confirms the formation of lipid vesicles. No rupture or leaching of vesicles was observed. The vesicles were non-aggregated with each other, confirming the stability of the formulation. The TEM image was in agreement with the data obtained for size and PDI. No significant difference in size was found.

Figure 3.

Transmission electron microscope image showing the morphology of luteolin-loaded nanovesicles (LT-NVs, F2).

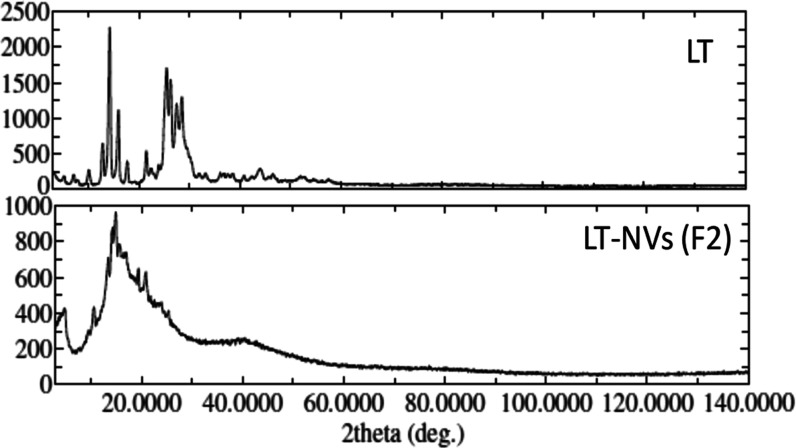

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

Figure 4 shows the changes in the XRD peaks of pure LT after encapsulation into the LT-NVs. Pure LT showed characteristic crystalline peaks with a 2θ of 10.1, 12.8, 14.2, 15.9, 21.5, 23.9, 25.5, 26.3, and 28.5, indicating the crystallinity of the compound.25 LT-NVs (F2) showed low-intensity characteristic peaks at 12.5, 14.2, 20.9, and 23.7. The change in peak height and intensity confirms the solubility of LT in the used lipids. The formation of vesicles confirms that the drug LT was entrapped in the used lipid and lost its crystallinity. A similar type of finding was reported by Khan et al.,26 who showed the absence of a sharp characteristic diffraction pattern of LT peaks in the LT phospholipid complex.

Figure 4.

XRD of pure luteolin and luteolin-loaded nanovesicles (LT-NVs, F2).

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

Figure 5 reflects the FT-IR spectra of LT and various excipients, viz., span 60, cholesterol, phosphatidylcholine, and LT-NVs (F2). The spectral peaks of LT exhibited a wavenumber of 3214.83 cm–1, ascribed to the stretching vibration of the hydroxyl (−OH) group. The C=O stretching peaks were shown at 1664.04 cm–1. The IR spectra also revealed the peaks of C=C, C–O–C of the pyran ring, and C–H of the aromatic bending, which are imputed at 1439.34, 1345.48, and 849.44 cm–1, respectively. Span 60 ascribed the FT-IR spectra at 3381.26 cm–1 for the -OH stretching vibration, and at 2915.72 and 2850.53 cm–1 for the chains of the CH2 symmetric stretching vibration. The peaks of the stretching vibration for the ester (−CH2–COO–CH2−) group were observed at 1733.29 cm–1, whereas the C–O–C stretching vibrations were exhibited at 1173.02. The spectral peaks of span 60 also revealed the CH2 bending and rocking vibrations ascribed at 1462.34 and 720.91 cm–1. The excipient cholesterol imputed strong and broad −OH stretching peaks at 3406.67 cm–1 and CH2 symmetric stretching at 2938.67 cm–1. It also exhibited peaks at 1710.04 cm–1 for C=C at C-5 and C-6 of the ring B for the aforementioned excipient. The excipient phosphatidylcholine exhibited a frequency at 559.82 cm–1 for CN+ (CH3)3 deformation vibration. The acidic carboxylic group (RCOO–) of the excipient showed a stretching vibration at 2915.57 cm–1. The formulation (F2) showed insignificant change in the peaks of the aromatic −OH stretching vibration ascribed at 3330.18 cm–1, which may be due to the interaction of the excipient with the pure drug LT. The symmetric chain of CH2 stretching vibration of the excipient was also observed with a slight deviation at 2924.19 cm–1 in the spectrum. Some minute swap in the frequency of the formulation was observed for the peaks of C=O and C–O–C, which were exhibited at 1402.63 and 1034.82 cm–1 as compared with the pure drug. The C=C and C–H aromatic bending also exhibited the spectrum, with minor modification in the peaks ascribed at 1402.63 and 844.17 cm–1, respectively. This confirmed that there was a slight interaction between pure LT and the excipients.

Figure 5.

IR spectra of pure luteolin, excipients (cholesterol, span 60, phosphatidylcholine), and luteolin-loaded nanovesicles (LT-NVs, F2).

Luteolin Release Study

The prepared LT-NVs were evaluated to check the amount of LT released in 12 h of the study, and the data are shown in Table 2 and Figure 6. The release media phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) was selected to study the drug release because LT is a weak acid having a pKa of 10.3 and is easily ionized in weak alkaline condition.27,28 LT is a water-insoluble drug and showed a cumulative drug release of 20.1 ± 0.5%. LT-NVs showed biphasic release behavior with a fast release of 15–25% in the initial 2 h. The faster release is due to the diffusion mechanism from an outer layer of vesicles, as well as the drug molecules adhered to the surface.29 At 12 h, the maximum release was found to be 67.2 ± 0.75 to 88.28 ± 1.13%. The difference was found to be significant (p < 0.05). The maximum drug release was found to be 88.28 ± 1.13% from formulation F2 prepared with span 60:labrasol (6:4). The presence of the surfactant blend in formulation F2 helps to achieve the maximum release. The difference in the LT release also depends upon the phosphatidylcholine concentration. Formulations F1–F3 prepared with phosphatidylcholine 0.8% (w/v) showed a higher LT release in comparison to formulations F4–F6 prepared with phosphatidylcholine 0.9% (w/v). The release profile data depicted a closer LT release of formulation F3 prepared with span 60:labrasol (4:6) (85.9±1.5%). From the results, it was observed that the surfactant plays an important role in drug release. The formulation prepared with a single surfactant showed lesser drug release than the formulation prepared with the surfactant blend. In addition, the release rate varies upon increasing the labrasol concentration and reducing the span 60 concentration. The formulation prepared with phosphatidylcholine 0.9% (w/v) with a variable ratio of surfactant showed lesser LT release. The presence of a high concentration of lipid slows the LT release from the vesicles. The sustained drug release effect due to the lipid may be attributed to its greater stabilization effect.30,31

Figure 6.

Drug release profile of pure luteolin and luteolin-loaded nanovesicles (LT-NVs, F2). The release study was performed in triplicate and data shown as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Luteolin Permeation Study

The comparative drug permeation study data has been calculated to estimate the flux. Pure LT showed a significantly poor flux profile in comparison to the LT-NVs (F2) and lesser permeation (98.81 ± 5.04 μg/cm2/h), while LT-NVs (F2) depicted significantly (p < 0.001) enhanced permeation (229.91± 4.1 μg/cm2/h). The poor solubility of pure LT is the main reason for the poor permeation across the tested membrane. A significantly high (p < 0.001) enhancement of 3.8-fold in the permeation flux was achieved. The enhanced permeation in the permeation flux was achieved from F2 due to the presence of surfactant in the formulation, which helps to enhance the solubility of LT. The presence of cholesterol and lipid also helps reduce the barrier property at the site of absorption.32 This observation also showed that LT is not available for the P-gp pump and can easily cross the intestinal wall.33

Antioxidant Assessment

The antioxidant potentials of the prepared LT-NVs (F2) and pure LT were evaluated at different concentrations (Figure 7). LT is a flavonoid and has been reported for its antioxidant potential. Pure LT showed a slightly lesser antioxidant potential at each tested concentration than LT-NVs. The compound shows the antioxidant potential by reacting with the proton donor groups and changes to violet color. The antioxidant activity of LT depends upon the concentration tested; as the concentration increases, the antioxidant potential also increases for both samples [pure LT and LT-NVs (F2)]. At a lower concentration (10 μg/mL), pure LT and LT-NVs (F2) showed 63.52 ± 0.71 and 75.23 ± 0.97% antioxidant potential. The results showed a significant (p < 0.05) difference in the antioxidant potential between them. As the concentration increases from 10 to 50 μg/mL, the antioxidant property also gradually increases in both samples. Similarly, at 100 μg/mL, the antioxidant property increases in pure LT (73.64 ± 1.33%), and LT-NVs (F2) showed 87.48 ± 0.62% (p < 0.001). The presence of surfactant in the prepared formulation helps to get a better antioxidant potential by increasing the solubility of the drug. Similar findings have been reported in the published literature.34

Figure 7.

Antioxidant potential of pure luteolin and luteolin-loaded nanovesicles (LT-NVs, F2). The study was performed in triplicate, and data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison test was used to evaluate the statistical significance between two groups. The difference was considered significant if *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001 when compared with the same concentration of pure LT with LT-NVs (F2).

Cell Viability

The comparative cell viability data of pure LT and LT-NVs (F2) are depicted in Figure 8. The study revealed a significant effect on the cell viability of A549. The cytotoxic effect is reduced with increase in the concentration of LT. Pure LT showed the following cell viabilities (%) at different concentrations: 125 μM, 84.96 ± 2.62; 250 μM, 74.99 ± 3.13; 500 μM, 75.04 ± 0.77; 1000 μM, 75.27 ±1.45; and 2000 μM, 84.06 ± 1.98. LT-NVs showed the following cell viabilities (%) at different concentrations: 125 μM, 87.21 ± 8.4; 250 μM, 82.42 ± 1.2; 500 μM, 82.42 ± 1.6; 1000 μM, 70.2 ± 0.8; and 2000 μM, 37.97 ± 3.2. A significant difference in the cell viability was observed at 2000 μM concentration (p < 0.001). The effects of pure LT and LT-NVs were compared; LT-NVs showed a marked enhancement in growth inhibition. LT-NVs showed the effect at lower concentrations in comparison to pure LT. The enhanced activity from the LT-NVs was achieved due to the increased solubility of LT in the used lipid and surfactant, which helps to achieve a greater effect. The effect of both these groups is shown in Figure 8. The IC50 values of both the treatment groups were calculated; LT-NVs showed a lower value of 1.62 mM than pure LT, which did not show an IC50 value at the tested concentrations. So, from the results, we can conclude that the prepared LT-NVs reduced the IC50 value significantly. It also confirms that the prepared LT-NVs showed less cytotoxicity than pure LT. The effect on the cell viability is concentration-dependent.

Figure 8.

Cytotoxicity activity of pure luteolin and LT-NVs (F2). Data are depicted in percentage in comparison to control (100%). Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison test was used to evaluate the statistically significant difference between the control and the tested concentrations. The difference was considered significant if p < 0.05. ns = not significant when compared with control; *** p < 0.001 when compared with control; ### p < 0.001 when compared with the same concentration groups of pure luteolin.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Luteolin (LT) was purchased from Beijing Mesochem Technology Co. Pvt. Ltd. (Beijing, China). Cholesterol was purchased from Alpha Chemika, India; soy phosphatidylcholine and labrasol from Lipoid-GmbH, Germany and Gattefosse, Saint-Priest, France; and analytical-grade chloroform and methanol from Fisher Scientific, U.K. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and Dulbeccoʼs modified Eagleʼs media (DMEM) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and Thermo Fisher Scientific. The lung cancer cell line (A549) was obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ) (Braunschweig, Germany). All other chemicals and reagents used were of analytical grade.

Method of Preparation

LT-loaded nanovesicles (LT-NVs) were prepared by the thin-film deposition and hydration method.35 Accurately weighed quantities of luteolin, cholesterol, phosphatidylcholine, span 60, and labrasol were taken to prepare the LT-NVs (Table 1). The ingredients were dissolved in methanol:chloroform mixture (10 mL, 1:2) and transferred to a round-bottom flask. The flask was rotated at 50 rpm for 30 min and then kept overnight for complete removal of the organic solvent residue. The flask was rotated at 50 rpm for 30 min. The flasks were kept overnight for complete removal of the organic solvent residue. The flask was hydrated with phosphate-buffered saline for 1 h to remove the thin film from the flask. The prepared vesicles were further sonicated in ice condition using a probe sonicator to reduce the size and stored in a container for further use. The three cycles of sonication (1 min) were conducted at intervals of 5 min in ice condition (4 °C).

Characterization

Vesicle Size, Zeta Potential, and Polydispersity Index

The prepared nanovesicles were evaluated for size, polydispersity index, and zeta potential. The different parameters were assessed by the instrument (Malvern Zetasizer, Malvern, U.K.). The prepared samples (0.1 mL) were taken and diluted 100-fold to evaluate their size and zeta potential. The diluted sample (1 mL) was placed into the cuvette, and then, size and PDI were measured. The PDI value must be less than 0.5 to give more homogeneity to the sample. The zeta potential (ZP) value gives the stability of the sample, and the ideal value must be ± 30 mV.

Encapsulation Efficiency

The encapsulation of LT in the prepared nanovesicles (LT-NVs) was evaluated by the indirect method.36 The sample (2 mL) was taken and centrifuged at 10 000 rpm for 1 h using a cooling centrifuge (Centurion Scientific Ltd.). The supernatant was separated and further diluted in methanol. The amount of LT was measured spectrophotometrically at 350 nm using a UV spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV, 2401 PC, Japan). The entrapment efficiency of the prepared formulations was calculated using the below formula37

Transmission Electron Microscopy

The surface morphology of the prepared LT-NVs was analyzed by a transmission electron microscope (JEM, JOEL). One drop of the sample was taken on a copper grid, and uranyl acetate 2% (w/v) was added and kept aside for 5 min to stain the sample. The excess sample was removed and then dried at 20 °C. Finally, the image was visualized using TEM at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV.

X-ray Diffraction

The crystalline structure of all of the samples was evaluated to study the changes in the nature of the sample after formulation. The study was performed using an X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku International Corporation, Japan). The samples were scanned between 5 and 40° with a CuKά radiation of 40 kV.

Infrared Spectroscopy

The drug-polymer interaction of the prepared LT-NVs was evaluated using infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR, Bruker Alpha, Germany). The samples of pure LT, span 60, and LT-NVs were tested to compare the spectral changes. The scanning was performed between 4000 and 400 cm–1. The spectra of pure LT were compared with the spectra of sample F2 to evaluate the changes in peak height and change in peak position.

Luteolin Release Study

The drug release study of luteolin nano-lipid vesicles (LT-NVs) was performed using the dialysis bag method.38 Briefly, LT-NVs and pure LT (5 mg LT) were filled in the dialysis membrane and tied. The bag was dipped into a beaker containing phosphate buffer (500 mL). The temperature was set to 37 °C and the release media was stirred at 100 rpm. At definite intervals, a 5 mL sample was collected and replaced with the fresh release media to make a uniform study condition. The released content was filtered, diluted, and the released concentration at each time point was evaluated at 350 nm using a UV spectrophotometer.

Luteolin Permeation Study

The study was carried out as per the reported method with slight modifications.39 The egg membrane was used as a permeating membrane due to its similarity to skin. The membrane was prepared as per the reported procedure.40 The egg membrane was fixed to the diffusion cell having an area of 3.22 cm2 and a receptor volume of 22 mL. The study was performed at 37 °C using phosphate-buffered saline as release media. The prepared and optimized LT-NVs and pure LT (5 mg of LT) were filled in the donor compartment. At fixed time intervals, the released sample (1 mL) was removed from the receptor compartment and replaced with the same fresh media. The sample was diluted and filtered, and the LT concentration was estimated using a UV spectrophotometer.

Antioxidant Assessment

LT-NVs and pure LT were assessed for antioxidant potential using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) scavenging method by the reported procedure with a slight modification by Caddeo et al.34 The stock solution (1 mg/mL) was prepared and further diluted in three different concentrations (10, 50, and 100 μg/mL). The DPPH solution in methanol was prepared at a concentration of 25 μM. The prepared DPPH sample (2 mL) was added to 25 μL of pure LT and LT-NVs (F2). The sample was kept aside for 30 min in the dark to complete the reaction. The absorbance of each test sample was evaluated at 517 nm using methanol as blank. The absorbance of the sample depends upon the intrinsic antioxidant property. The DPPH antioxidant scavenging activity of each sample was calculated by estimating the antioxidant percentage using the equation

where As is the DPPH absorbance and At is the test sample absorbance.

Cell Viability Assay

The cell line study was assessed on A549 for the prepared formulation (LT-NVs), and the results were compared with those of pure LT. The study was evaluated using MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl teterazolium bromide). The cells (A549) were seeded into the cell media, Dulbeccoʼs modified Eagleʼs media (DMEM, 10% FBS), using 96-well plates with 15 000 cells per well. The cells were incubated for 24 h with a flow of CO2 (5%) at 37 °C for proper growth and acclimatization. The different concentrations of the test samples (pure LT and LT-NVs) were added to each well in triplicate to assess the cytotoxic effect. The stock solution of both the test samples was prepared in DMSO and further serially diluted in the 96-well plates using serum-free media. The concentration of DMSO was kept below 1% to avoid undesirable effects. The different concentrations of pure LT and LT-NVs (125, 250, 500, 1000, and 2000 μM) were tested and their results were compared. After addition to the wells, MTT solution (10 μL, 5 mg/mL) prepared in phosphate-buffered saline was added, except for the control well. The cells were incubated to metabolize the MTT by viable cells. Finally, the media was removed from the wells and DMSO (100 μL) was added to dissolve the formazan. The plate was incubated for 30 min, and the estimation was performed at 570 nm using DMSO as blank. The untreated cells were considered as control to compare the result.41

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using GraphPad Instat software (GraphPad software Inc., La Jolla, CA). The study was performed in triplicate, and data are shown as mean ± SD.

Conclusions

LT-loaded nanovesicles were prepared by the solvent evaporation method using cholesterol, span 60, phosphatidylcholine, and labrasol. The prepared LT-NVs showed nanovesicles with a low PDI value (<0.5) and negative zeta potential value. LT-NVs showed a high encapsulation efficiency as well as significantly (p < 0.05) enhanced drug release and permeation flux. The selected LT-NVs (F2) showed nanovesicle of size 373 ± 4.65 nm, PDI 0.28 ± 0.07, zeta potential −14.82 ± 0.54, encapsulation efficiency 83.75 ± 0.35, and drug release amount 88.3 ± 1.13. The surface morphology image depicted vesicles with a smooth surface. The antioxidant result depicted enhanced activity as the concentration of LT increases. Also, significantly greater activity was observed from formulation F2 in comparison to pure LT. The cytotoxicity study results revealed that formulation F2 showed higher cell viability than pure LT. From the study, it can be concluded that LT-NVs could be a suitable delivery system for the treatment of cancer by oral delivery.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP- 2021/146) at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Keikha M.; Esfahani B. N. The relationship between tuberculosis and lung cancer. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2018, 7, 58. 10.4103/abr.abr_182_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norouzi M.; Hardy P. Clinical applications of nanomedicines in lung cancer treatment. Acta Biomater. 2021, 121, 134–142. 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J.; Colombet M.; Soerjomataram I.; Mathers C.; Parkin D.; Pineros M.; Znaor A.; Bray F. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 1941–1953. 10.1002/ijc.31937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-López J.; El-Hammadi M. M.; Ortiz R.; Cayero-Otero M. D.; Cabeza L.; Perazzoli G.; Martin-Banderas L.; Baeyens J. M.; Prados J.; Melguizo C. A novel nanoformulation of PLGA with high non-ionic surfactant content improves in vitro and in vivo PTX activity against lung cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 141, 451–465. 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norouzi M. Gold nanoparticles in glioma theranostics. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 156, 104753 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norouzi M.; Yathindranath V.; Thliveris J. A.; Kopec B. M.; Siahaan T. J.; Miller D. W. Doxorubicin-loaded iron oxide nanoparticles for glioblastoma therapy: a combinational approach for enhanced delivery of nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11292 10.1038/s41598-020-68017-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Wang N.; Li Q.; Zhou Y.; Luan Y. A two-pronged photodynamic nanodrug to prevent metastasis of basal-like breast cancer. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 2305–2308. 10.1039/D0CC08162K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernabeu E.; Cagel M.; Lagomarsino E.; Moretton M.; Chiappetta D. A. Paclitaxel: what has been done and the challenges remain ahead. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 526, 474–495. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonali S. R. P.; Singh N.; Sharma G.; Vijayakumar M. R.; Koch B.; Singh S.; Singh U.; Dash D.; Pandey B. L.; Muthu M. S. Transferrin liposomes of docetaxel for brain-targeted cancer applications: formulation and brain theranostics. Drug Delivery 2016, 23, 1261–1271. 10.3109/10717544.2016.1162878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korani M.; Ghaffari S.; Attar H.; Mashreghi M.; Jaafari M. R. Preparation and characterization of nanoliposomal bortezomib formulations and evaluation of their anti-cancer efficacy in mice bearing C26 colon carcinoma and B16F0 melanoma. Nanomedicine 2019, 20, 102013 10.1016/j.nano.2019.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S.; Mohamed M. S.; Raveendran S.; Rochani A. K.; Maekawa T.; Kumar D. S. Formulation, characterization and evaluation of morusin loaded niosomes for potentiation of anticancer therapy. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 32621–32636. 10.1039/C8RA06362A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabry S.; Ramadan A.; Abdelghany M.; Okda T.; Hasan A. Formulation, characterization, and evaluation of the anti-tumor activity of nanosizedgalangin loaded niosomes on chemically induced hepatocellular carcinoma in rats. J. Drug Delivery Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 102163 10.1016/j.jddst.2020.102163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guillot A. J.; Jornet-Molla E.; Landsberg N.; Milian-Guimera C.; Montesinos M. C.; Garrigues T. M.; Melero A. Cyanocobalamin ultraflexible lipid vesicles: characterization and in vitro evaluation of drug-skin depth profiles. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 418 10.3390/pharmaceutics13030418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z. Q.; Li M. H.; Qin Y. M.; Jiang H. Y.; Zhang X.; Wu M. H. Luteolin Inhibits Tumorigenesis and Induces Apoptosis of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells via Regulation of MicroRNA-34a-5p. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 447 10.3390/ijms19020447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L.; Peng H.; Li K.; Zhao R.; Li L.; Yu Y.; Wang X.; Han Z. Luteolin exerts an anticancer effect on NCI-H460 human non-small cell lung cancer cells through the induction of Sirt1-mediated apoptosis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 4196–4202. 10.3892/mmr.2015.3956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliman N. A.; Abd-Ellatif R. N.; ELSaadany A. A.; Shalaby S. M.; Bedeer A. E. Luteolin and 5-flurouracil act synergistically to induce cellular weapons in experimentally induced Solid Ehrlich Carcinoma: Realistic role of P53; a guardian fights in a cellular battle. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2019, 310, 108740 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.108740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S. F.; Yang W. F.; Chang H. R.; Chu S. C.; Hsieh Y. S. Luteolin induces apoptosis in oral squamous cancer cells. J. Dent. Res. 2008, 87, 401–406. 10.1177/154405910808700413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imran M.; Rauf A.; Abu-Izneid T.; Nadeem M.; Shariati M. A.; Khan I. A.; Imran A.; Orhan I. E.; Rizwan M.; Atif M.; Gondal T. A.; Mubarak M. S. Luteolin, a flavonoid, as an anticancer agent: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 112, 108612 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y.; Chen S.; Zhou J.; Chen J.; Tian L.; Gao W.; Zhang Y.; Ma A.; Li L.; Zhou Z. Luteolin cocrystals: Characterization, evaluation of solubility, oral bioavailability and theoretical calculation. J. Drug Delivery Sci. Technol. 2019, 50, 248–254. 10.1016/j.jddst.2019.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelkader H.; Alani A. W.; Alany R. G. Recent advances in non-ionic surfactant vesicles (niosomes): self-assembly, fabrication, characterization, drug delivery applications and limitations. Drug Delivery 2014, 21, 87–100. 10.3109/10717544.2013.838077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshosaz J.; Pardakhty A.; Hajhashemi V. I.; Najafabadi A. R. Development and physical characterization of sorbitan monoester niosomes for insulin oral delivery. Drug Delivery 2003, 10, 251–262. 10.1080/drd_10_4_251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Gao H.; Bao G. Physical principles of nanoparticle cellular endocytosis. ACS Nano. 2015, 9, 8655–8671. 10.1021/acsnano.5b03184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph E.; Singhvi G. Multifunctional nanocrystals for cancer therapy: a potential nanocarrier. Nanomater. Drug Delivery Ther. 2019, 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Danaei M.; Dehghankhold M.; Ataei S.; Hasanzadeh D. F.; Javanmard R.; Dokhani A.; Khorasani S.; Mozafari M. R. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics. 2018, 10, 57 10.3390/pharmaceutics10020057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawornchat P.; Pattarakankul T.; Palaga T.; Intasanta V.; Wanichwecharungruang S. Polymerized luteolin nanoparticles: synthesis, structure elucidation, and anti-inflammatory activity. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 2846–2855. 10.1021/acsomega.0c05142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan J.; Saraf S.; Saraf S. Preparation and evaluation of luteolin–phospholipid complex as an effective drug delivery tool against GalN/LPS induced liver damage. Pharm. Delivery Technol. 2016, 21, 475–486. 10.3109/10837450.2015.1022786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielczarek C. Acid–base properties of selected flavonoid glycosides. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 25, 273–279. 10.1016/j.ejps.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qing W.; Wang Y.; Li H.; Ma F.; Zhu J.; Liu X. Preparation and characterization of copolymer micelles for the solubilization and in vitro release of luteolin and luteoloside. AAPS PharmSciTech 2017, 18, 2095–2101. 10.1208/s12249-016-0692-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaker D. S.; Shaker M. A.; Hanafy M. S. Cellular uptake, cytotoxicity and in-vivo evaluation of Tamoxifen citrate loaded niosomes. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 493, 285–294. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AbouSamra M. M.; Salama A. H.; Awad G. E. A.; Mansy S. S. Formulation and evaluation of novel hybridized nanovesicles for enhancing buccal delivery of Ciclopirox olamine. AAPS PharmSciTech 2020, 21, 283 10.1208/s12249-020-01823-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saravanakumar G.; Min K. H.; Min D. S.; Kim A. Y.; Lee C. M.; Cho Y. W.; et al. Hydrotropic oligomer-conjugated glycol chitosan as a carrier of paclitaxel: synthesis, characterization, and in vivo biodistribution. J. Controlled Release 2009, 140, 210–217. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalifa A.-Z. M.; Abdul Rasool B. K. Optimized Mucoadhesive Coated Niosomes as a Sustained Oral Delivery System of Famotidine. AAPS PharmSciTech 2017, 18, 3064–3075. 10.1208/s12249-017-0780-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zare M.; Samani S. M.; Sobhani Z. Enhanced intestinal permeation of doxorubicin using chitosan nanoparticles. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2018, 8, 411–417. 10.15171/apb.2018.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caddeo C.; Pucci L.; Gabriele M.; Carbone C.; Fernàndez-Busquetsd X.; Valenti D.; Pons R.; Vassallo A.; Fadda A. M.; Manconi M. Stability, biocompatibility and antioxidant activity of PEG-modified liposomes containing resveratrol. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 538, 40–47. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matloub A. A.; Salama A. H.; Aglan H. A.; AbouSamra M. M.; ElSouda S. S. M.; Ahmed H. H. Exploiting bilosomes for delivering bioactive polysaccharide isolated from Enteromorpha intestinalis for hacking hepatocellular carcinoma. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2018, 44, 523–34. 10.1080/03639045.2017.1402922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammar H.; Ghorab M.; Kamel R.; Salama A. H. A trial for the design and optimization of pH-sensitive microparticles for intestinal delivery of cinnarizine. Drug Delivery Transl. Res. 2016, 6, 195–209. 10.1007/s13346-015-0277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari M. J.; Alshahrani S. M. Nano-encapsulation and characterization of baricitinib using poly-lactic-glycolic acid co-polymer. Saudi Pharm. J. 2019, 27, 491–501. 10.1016/j.jsps.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byeon J. C.; Lee S. E.; Kim T. H.; Ahn J. B.; Kim D. H.; Choi J. S.; Park J. S. Design of novel proliposome formulation for antioxidant peptide, glutathione with enhanced oral bioavailability and stability. Drug Delivery 2019, 26, 216–225. 10.1080/10717544.2018.1551441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem M. N.; Idris M. Formulation design and development of a unani transdermal patch for antiemetic therapy and its pharmaceutical evaluation. Scientifica 2016, 2016, 7602347 10.1155/2016/7602347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigh J. M.; Smith E. W. The selection and use of natural and synthetic membranes for in vitro diffusion experiments. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 1994, 2, 311–330. 10.1016/0928-0987(94)90032-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S.; Shang Q.; Wang N.; Li Q.; Song A.; Luan Y. Rational design of a minimalist nanoplatform to maximize immunotherapeutic efficacy: Four birds with one stone. J. Controlled Release 2020, 328, 617–630. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]