Abstract

Purpose

The threat of national and international terrorism remains high. Preparation is the key requirement for the resilience of hospitals and out-of-hospital rescue forces. The scientific evidence for defining medical and tactical strategies often feeds on the analysis of real incidents and the lessons learned derived from them. This systematic review of the literature aims to identify and systematically report lessons learned from terrorist attacks since 2001.

Methods

PubMed was used as a database using predefined search strategies and eligibility criteria. All countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) were included. The time frame was set between 2001 and 2018.

Results

Finally 68 articles were included in the review. From these, 616 lessons learned were extracted and summarized into 15 categories. The data shows that despite the difference in attacks, countries, and casualties involved, many of the lessons learned are similar. We also found that the pattern of lessons learned is repeated continuously over the time period studied.

Conclusions

The lessons from terrorist attacks since 2001 follow a certain pattern and remained constant over time. Therefore, it seems to be more accurate to talk about lessons identified rather than lessons learned. To save as many victims as possible, protect rescue forces from harm, and to prepare hospitals at the best possible level it is important to implement the lessons identified in training and preparation.

Keywords: Terror attacks, Evaluation, Lessons learned, Emergency preparedness, Public health preparedness, Mass casualties

Introduction

Background

The emergency management of terrorist attacks has been one of the prominent topics in disaster and emergency medicine before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. The most recent attacks have shown that this particular threat is still present and highly relevant today [1–4]. The idea of “stopping the dying as well as the killing”, which has been coined by Park et al. after the London Bridge and Borough Market attacks in 2017, emphasizes the urgent need to focus on emergency management and early medical and surgical intervention [5].

Rescue systems and hospitals must prepare themselves to manage terrorist attacks in order to save as many lives as possible and to return rescue forces from the missions unscathed. As it is impossible to conduct prospective, high-quality scientific studies, the definition of these medical and tactical strategies relies on the analysis of real incidents and the lessons learned derived from them. After the Paris terror attacks in 2015 for example, important publications, describing the events of the night of the 13th of November 2015, were published [6, 7]. Two publications, one by the French Health Ministry and one by Carli et al., about the “Parisian night of terror” have gone a step further and have clearly described the lessons learned from these attacks [8, 9]. Importantly, experts agree on the importance of the scientific and systematic evaluation of the most recent terror attacks [10]. Challen et al. proved the existence of a large body of literature on the topic in 2012 already, but questioned its validity and generalisability. The authors based their conclusion on a review, which focused on emergency planning for any kind of disaster [11].

More than ever, the principle applies, that the preparation for extraordinary disastrous incidents is the decisive prerequisite for successful management. The lack of preparedness for the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has taught modern society this lesson.

With the aim to identify and systematically report the lessons learned from terrorist attacks as an important basis for preparation, we conducted the presented systematic review of the literature.

Materials and methods

Study design and search strategy

This is a systematic review of the literature with the focus on lessons learned from terror attacks. A comprehensive literature search was performed to identify articles reporting medical and surgical management of terrorist attacks and lessons learned derived from them. PubMed was used as database. The first search term concentrated on terrorism, the second on medical/surgical management and the third on evaluation and lessons learned. Adapted PRISMA guidelines were used and all articles were checked and reported against its checklist [12].

The search terms were formulated as an advanced search in PubMed in the following way: Search: ((Terror* OR Terror* Attack* OR Terrorism* OR Mass Casult* Incident* OR Mass Shooting* OR Suicide Attack* OR Suicide Bomb* OR Rampage* OR Amok*) AND (Prehospital* Care* OR Emergenc* Medical* Service* OR Emergenc* Service* OR Emergenc* Care* OR Rescue Mission* OR Triage* OR Disaster* Management* OR First* Respon*)) AND (Lesson* Learn* OR Quality Indicator* OR Evaluation* OR Analysis* OR Review* OR Report* OR Deficit* OR Problem*).

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Time frame: The attack on the World Trade Centre in New York, the Pentagon in Arlington, and the crash of a hijacked airliner in 2001 is considered the event that brought international terrorism onto the world stage with the beginning of the new millennium. The attacks have been documented and analysed in great detail. For this reason, this analysis starts in 2001 and ends with the terrorist attacks in London and Manchester in 2017. The search history was extended to the year 2018.

Included countries: Terrorism is a worldwide phenomenon. Attempting to evaluate the data of all terrorist attacks that have occurred since 2001 seems impossible due to the extremely high number. The work therefore focuses mainly on Western-oriented democracies, for which a terrorist attack is still a relatively rare event and whose infrastructure and emergency services recently had to adapt to this challenge. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)—countries therefore represent a reasonable selection of countries for this study.

Exclusion criteria:

Articles reporting mass casualty incidents without a terroristic background

Personal reports without any clear defined lessons learned

Articles dealing exclusively with chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) terrorism

Articles dealing with a narrow point of view and only dealing with specific types of injuries such as burns or psychiatry

Articles not written in English.

Articles dealing exclusively with chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear terrorism (CBRN-attacks) were excluded from the literature-search. The reason for this is the large number of special problems and issues associated with this type of incident. To address this adequately, a separate literature search would be necessary.

Data abstraction

The lessons learned from each included article were extracted according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Duplicated data was excluded. As expected, there was a vast number of individual lessons learned. To summarize the results, it was imperative to divide them into categories. As a basis for developing the categories existing systems were used. The reporting system of Fattah et al. defines 6 categories, but these were not sufficient to represent all types of lessons learned [13]. Wurmb et al. had recently developed 13 clusters of quality indicators [14], some of which we were able to adopt. However, both systems focused on categories that serve to describe the overall setting of a rescue mission and were therefore not fully suitable for clustering lessons learned. Finally these 15 categories were used for clustering the lessons learned:

Preparedness/planning/training

Tactics/organisation/logistics

Medical treatment and Injuries

Equipment and supplies

Staffing

Command

Communication

Zoning and safety scene

Triage

Patient flow and distribution

Team spirit

Role Understanding

Cooperation and multidisciplinary approach

Psychiatric support

Record keeping

After defining the categories, the lessons learned were assigned to them. Where applicable, the lessons learned were divided into “pre-incident”, “during incident” and “post-incident” within the different categories.

Results

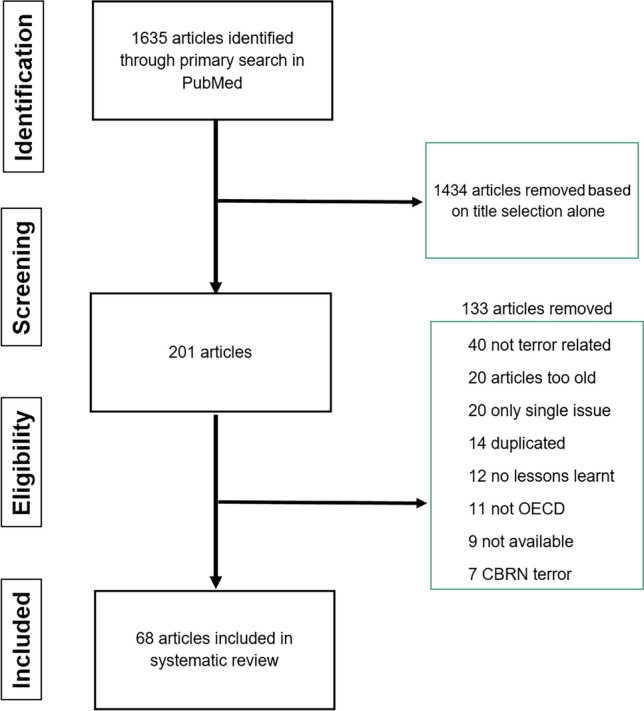

The extended PubMed Search yielded 1635 articles out of which 1434 articles were excluded on title selection only. The abstracts of the remaining 201 articles were evaluated and finally 68 articles were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Process to identify the articles included in the systematic review

To evaluate the quality of the included studies, the PRISMA evaluation was used and all articles were checked and reported against its checklist and then rated as either high quality (HQ), acceptable quality (AQ) or low quality (LQ) paper (Table 1) [12].

Table 1.

Overview of all included articles with PRISMA evaluation

| Authors | Year | Incident site | Study type | PRISMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roccaforte et al. [15] | 2001 | USA 9/11 | Retrospective | AQ |

| Martinez et al.[16] | 2001 | USA 9/11 | Eye Witness | AQ |

| Cook et al. [17] | 2001 | USA 9/11 | Eye Witness | AQ |

| Tamber et al. [18] | 2001 | USA 9/11 | Expert Opinion | AQ |

| Simon et al. [19] | 2001 | USA 9/11 | Review/Report | AQ |

| Mattox et al. [20] | 2001 | USA 9/11 | Review/Report | AQ |

| Shapira et al. [21] | 2002 | Israel | General Review | HQ |

| Frykberg et al. [22] | 2002 | Multiple | Review/Report | HQ |

| Garcia-Castrillo et al. [23] | 2003 | Madrid, Spain | Review/Report | AQ |

| Shamir et al. [24] | 2004 | Israel | Review/Report | HQ |

| Einav et al. [25] | 2004 | Israel | Guidelines | HQ |

| Almogy et al. [26] | 2004 | Israel | Review/Report | AQ |

| Rodoplu et al. [27] | 2004 | Istanbul, Turkey | Retrospective Study | AQ |

| Kluger et al. [28] | 2004 | Israel | Review/Report | AQ |

| Gutierrez de Ceballos et al. [29] | 2005 | Madrid, Spain | Retrospective Study | AQ |

| Kirschbaum et al. [30] | 2005 | USA 9/11 | Lessons Learned | HQ |

| Aschkenazy-Steuer et al. [31] | 2005 | Israel | Retrospective Study | HQ |

| Lockey et al. [32] | 2005 | London, UK | Retrospective Study | HQ |

| Hughes et al. [33] | 2006 | London, UK | Review/Report | AQ |

| Shapira et al. [34] | 2006 | Israel | Review/Report | AQ |

| Aylwin et al. [35] | 2006 | London, UK | Review/Report | HQ |

| Mohammed et al. [36] | 2006 | London, UK | Review/Report | AQ |

| Bland et al. [37] | 2006 | London, UK | Personal Review | AQ |

| Leiba et al. [38] | 2006 | Israel | Review/Report | HQ |

| Singer et al. [39] | 2007 | Israel | Review/Report | HQ |

| Schwartz et al. [40] | 2007 | Israel | Review/Report | AQ |

| Gomez et al. [41] | 2007 | Madrid, Spain | Review/Report | AQ |

| Bloch et al. [42] | 2007 | Israel | Review/Report | AQ |

| Bloch et al. [43] | 2007 | Israel | Review/Report | AQ |

| Barnes et al. [44] | 2007 | London, UK | Government Evaluation | HQ |

| Carresi et al. [45] | 2008 | Madrid, Spain | Review/Report | HQ |

| Raiter et al. [46] | 2008 | Israel | Review/Report | HQ |

| Shirley et al. [47] | 2008 | London, UK | Review/Report | HQ |

| Almgody et al. [48] | 2008 | Multiple | Review/Report | AQ |

| Turegano-Fuentes et al. [49] | 2008 | Madrid, Spain | Review/Report | AQ |

| Pinkert et al. [50] | 2008 | Israel | Review/Report | HQ |

| Pryor et al. [51] | 2009 | USA 9/11 | Review/Report | HQ |

| Lockey et al. [52] | 2012 | Utoya, Norway | Review/Report | AQ |

| Sollid et al. [53] | 2012 | Utoya, Norway | Review/Report | AQ |

| Gaarder et al. [54] | 2012 | Utoya, Norway | Review/Report | AQ |

| No authors listed [55] | 2013 | Boston USA | Review/Report | AQ |

| Jacobs et al. [56] | 2013 | USA | General Review | AQ |

| Gates et al. [57] | 2014 | Boston, USA | Review/Report | AQ |

| Wang et al. [58] | 2014 | Multiple | General Review | HQ |

| Ashkenazi et al. [59] | 2014 | Israel | Overall Review | AQ |

| Thompson et al. [60] | 2014 | Multiple | Retrospective | AQ |

| Rimstad et al. [61] | 2015 | Oslo, Norway | Retrospective | AQ |

| Goralnick et al. [62] | 2015 | Boston, USA | Retrospective | AQ |

| Hirsch et al. [6] | 2015 | Paris, France | Personal Review | HQ |

| Lee et al. [63] | 2016 | San Bernadino, USA | Personal Review | HQ |

| Pedersen et al. [64] | 2016 | Utoya, Norway | Review/Report | AQ |

| Raid et al. [65] | 2016 | Paris, France | Personal Review | AQ |

| Philippe et al. [8] | 2016 | Paris, France | Government Review | HQ |

| Traumabase et al. [66] | 2016 | Paris, France | Personal Review | HQ |

| Gregory et al. [67] | 2016 | Paris, France | Review/Report | AQ |

| Ghanchi et al. [68] | 2016 | Paris, France | Review/Report | AQ |

| Khorram-Manesh et al. [69] | 2016 | Multiple | Review/Report | HQ |

| Goralnick et al. [10] | 2017 | Paris/Boston | Expert Opinion | AQ |

| Lesaffre et al. [70] | 2017 | Paris, France | Review/Report | AQ |

| Wurmb et al. [71] | 2018 | Würzburg, Germany | Lessons Learned | HQ |

| Brandrud et al. [72] | 2017 | Utoya, Norway | Review/Report | HQ |

| Carli et al. [9] | 2017 | Paris/Nice, France | Review/Report | HQ |

| Borel et al. [73] | 2017 | Paris, France | Review/Report | AQ |

| Bobko et al. [74] | 2018 | San Bernadino, USA | Review/Report | AQ |

| Chauhan et al. [75] | 2018 | Multiple | Review/Report | HQ |

| Hunt et al. [76] | 2018 | London/Manchester, UK | Review/Report | HQ |

| Hunt et al. [77] | 2018 | London/Manchester, UK | Review/Report | HQ |

| Hunt et al. [78] | 2018 | London/Manchester, UK | Review/Report | HQ |

HQ high quality, AQ acceptable quality, LQ low quality, USA United States of America, UK United Kingdom

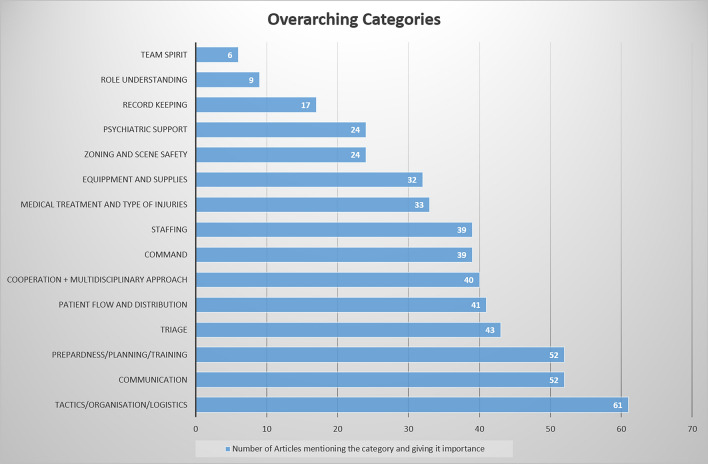

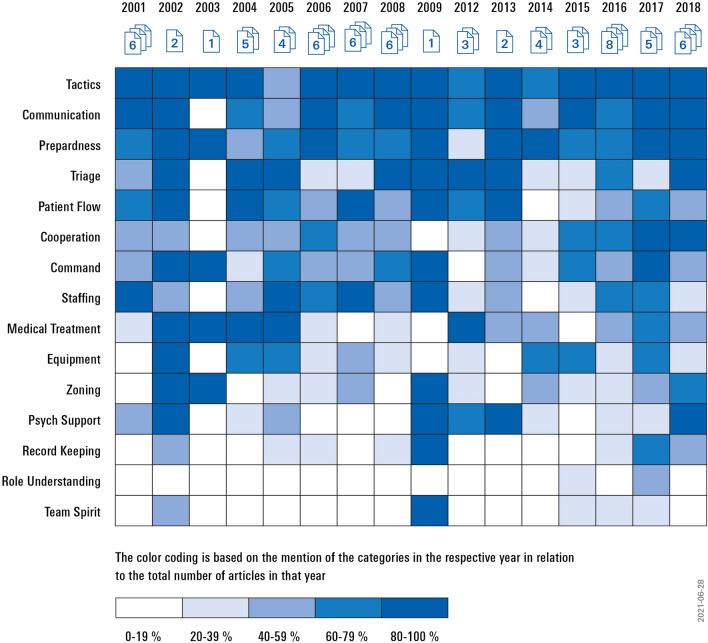

A total of 616 lessons learned were assigned to the 15 categories. If a lesson matched more than one category, it was assigned to all matching categories. Therefore, multiple entries occur in some cases. Table 2 shows the distribution of categories across all included articles, while Fig. 2 shows the number of articles in which each category appears. In this figure, the publications are assigned to the respective categories. This provides an overview of the number of articles dealing with each category. An overview of the distribution over time is later given in Fig. 3. Lessons learned within the category “tactics/organisation/logistics” were mentioned most frequently, while the category “team spirit” was ranked last in this list.

Table 2.

Distribution of the 15 clusters across all included articles

| Study | Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roccaforte et al. [15] | 2001 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Martinez et al.[16] | 2001 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Cook et al. [17] | 2001 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Tamber et al.[18] | 2001 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Simon et al.[19] | 2001 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Mattox et al. [20] | 2001 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Shapira et al. [21] | 2002 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Frykberg et al. [22] | 2002 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Garcia-Castrillo et al. [23] | 2003 | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Shamir et al.[24] | 2004 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Einav et al. [25] | 2004 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Almogy et al. [26] | 2004 | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Rodoplu et al. [27] | 2004 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Kluger et al. [28] | 2004 | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Gutierrez de Ceballos et al. [29] | 2005 | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Kirschbaum et al. [30] | 2005 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Aschkenazy-Steuer et al. [31] | 2005 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Lockey et al. [32] | 2005 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Hughes et al. [33] | 2006 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Shapira et al. [34] | 2006 | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Aylwin et al. [35] | 2006 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Mohammed et al. [36] | 2006 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Bland et al. [37] | 2006 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Leiba et al. [38] | 2006 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Singer et al. [39] | 2007 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Schwartz et al. [40] | 2007 | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Gomez et al. [41] | 2007 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Bloch et al. [42] | 2007 | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Bloch et al. [43] | 2007 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Barnes et al.[44] | 2007 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Carresi et al.[45] | 2008 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Raiter et al.[46] | 2008 | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Shirley et al.[47] | 2008 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Almgody et al. [48] | 2008 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Turegano-Fuentes et al. [49] | 2008 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Pinkert et al. [50] | 2008 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Lockey et al. [52] | 2012 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Sollid et al. [53] | 2012 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Gaarder et al. [54] | 2012 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| NN et al. [55] | 2013 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Jacobs et al. [56] | 2013 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Gates et al. [57] | 2014 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Wang et al. [58] | 2014 | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Ashkenazi et al. [59] | 2014 | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Thompson et al. [60] | 2014 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Rimstad et al. [61] | 2015 | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Goralnick et al. [62] | 2015 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Hirsch et al. [6] | 2015 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Lee et al. [63] | 2016 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Pedersen et al. [64] | 2016 | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Raid et al. [65] | 2016 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Philippe et al. [8] | 2016 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Traumabase et al. [66] | 2016 | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Gregory et al. [67] | 2016 | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Ghanchi et al. [68] | 2016 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Khorram-Manesh et al. [69] | 2016 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Goralnick et al. [10] | 2017 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Lesaffre et al. [70] | 2017 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Brandrud et al. [72] | 2017 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Carli et al. [9] | 2017 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Borel et al. [73] | 2017 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Wurmb et al. [71] | 2018 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| Bobko et al. [74] | 2018 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Chauhan al. [75] | 2018 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Hunt et al. [76] | 2018 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Hunt et al. [77] | 2018 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Hunt et al. [78] | 2018 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

1—Tactics/organization/logistics, 2—Communication, 3—Preparedness/planning/training 4—Triage, 5—Patient flow and distribution, 6—Cooperation/multi-disciplinary approach, 7—Command, 8—Staffing, 9—Medical treatment and type of injuries, 10—Equipment/supplies, 11—Zoning/scene safety, 12—Psych support, 13—Record keeping, 14—Role understanding, 15—Team spirit

Fig. 2.

Number of articles mentioning each of the 15 categories

Fig. 3.

Categories of lessons learned from terror attacks—development since 2001

To obtain a graphical overview over the entire study period, the frequency with which the categories were mentioned per year were colour-coded and presented in a matrix (Fig. 3).

A summary of all lessons learned assigned to the 15 categories can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

lessons learned assigned to the 15 overwhelming categories

| Lessons learned | Tactics/organization/logistics |

|---|---|

| Pre-incident | |

| 1 | Offer a detailed manual for potential terror attacks |

| 2 | Need for having a solid disaster plan for each hospital |

| 3 | Have a national standard for major incidents and a preparedness concept/disaster response plan |

| 4 | Adequate trauma centre concepts on national level |

| 5 | Use trauma guidelines |

| 6 | Conduct updated disaster plans/drills |

| 7 | Active pre-planned protocols—pre hospital protocol + hospital protocol |

| 8 | All hospitals should be included in contingency planning |

| 9 | Do not base disaster plan on average surge rates |

| 10 | Standardisation in hospital incident planning |

| 11 | Have an emergency plan for preparedness |

| 12 | Use standard Protocols but keep flexibility |

| 13 | Establishment of various anti-terror contingency plans (hijack/bombing/shooting) |

| 14 | Mini disasters as basis for escalation (flu season) |

| 15 | Crisis management based on knowledge and data collection |

| During the incident | |

| 16 | Activate contingency/emergency plans soon |

| 17 | Organisation of trauma teams that stay with a patient |

| 18 | Cancellation of all elective surgery/discharge of all non-urgent patients |

| 19 | Establish a public information centre close to hospital |

| 20 | Alert all hospitals |

| 21 | Prehospital and hospital coordination + communication is necessary |

| 22 | Crowd control is important |

| 23 | Maximise surge capacity |

| 24 | Distance to hospital site is major distribution factor |

| 25 | Evacuation of the less critically ill to further away hospitals |

| 26 | Importance of controlled access to hospitals |

| 27 | Avoid main gate syndrome—overwhelmed resources at the closest hospital |

| 28 | Avoid overcrowding in the ER |

| 29 | Activation of white plan—all hospitals/all staff/empty beds → no shortage |

| 30 | Recruit help from outside early on |

| 31 | Do not forget flexibility |

| 32 | Combination of civil defence and emergency medical services |

| 33 | Designated treatment area |

| 34 | Rapid scene clearance—highly organised und efficient |

| 35 | Flexibility across incident sites/hospitals |

| 36 | Vehicle coordination and rapid accumulation |

| 37 | Set principles rather than fixed protocols to allow for flexibility |

| 38 | Importance of quick evacuation |

| 39 | Ambulance stacking area to allow access and reduce traffic jam |

| 40 | Important to declare major incident as soon as possible |

| 41 | Manage uncertainties and scene |

| 42 | Coordination of rescue—especially HEMS |

| 43 | Rapid logistical response |

| 44 | Divide emergency response into stages break into smaller parts |

| 45 | Adaptation of decisions taken |

| 46 | Early decision by incidence commander needed |

| 47 | No headquarter at frontline |

| 48 | Peri-incident intensive care management—forward deployment |

| 49 | Critical mortality is reduced by rapid advanced major incident management |

| 50 | Use ICU staff for resuscitation and triage |

| 51 | Four step approach to terror attacks: analysis of scenario; description of capabilities, analysis of gaps, development of operational framework |

| 52 | Experienced personnel should treat patient and not take on organisation |

| 53 | Empty hospital immediately |

| 54 | Focus on increasing bed capacity especially ICU beds |

| 55 | Constant update on resources and surge limitation of all hospitals |

| 56 | Trauma leaders must be aware of bed capacities |

| 57 | Combined activation of major incident plans (all EMS services) |

| 58 | Early activation of surge capacity |

| 59 | Crucial interaction/communication between hospital/police/municipalities |

| 60 | Fullback structures but flexibility and improvisation important |

| 61 | Tactical management—get an overview and do not get stuck in details |

| 62 | Prehospital damage control—military concepts in civilian setting |

| 63 | Regional resource mobilisation vital |

| 64 | Have a plan but use continuous reassessment and modification of response strategy |

| 65 | Use METHANE to assess incident |

| 66 | Clear escalation plan |

| 67 | Coordination and collaboration should be planned and practised at intra/inter-regional, multiagency and multiprofessional levels |

| 68 | Improved forensic management |

| 69 | Logistic is important for operational strategic roles |

| 70 | Maintaining access to other emergencies MI/stroke, etc. |

| 71 | Gradual De-escalation – part of contingency plan |

| 72 | Issue: recognition of situational aspect and severity + complexity—evolving risk |

| 73 | Cockpit view due to HEMS—helpful in big sweep of casualties |

| 74 | Limited mobilisation at remote hospitals |

| 75 | Incident commander appoints: liaison officer; public information officer; personnel officer; logistics officer; data officer; medical command officer; patient/family information officer |

| 76 | “ABCD response”: assess incident size and severity, alert backup personnel, perform initial casualty care, and provide definitive treatment |

| 77 | Authority and command structure—two command posts—administrational vs medical management |

| 78 | Med Students used as runners |

| 79 | Tape fixed with name/specialty |

| 80 | Delays should be expected |

| 81 | Disruption in transport—lengthens rescue effort |

| 82 | Guidelines on biochemical warfare |

| 83 | Structural organisation important |

| 84 | Clear and well-structured coordination |

| 85 | Management of uninjured survivors and relatives—good communication |

| 86 | Development of operational framework |

| 87 | Assessment and re-evaluation of disaster plans |

| 88 | ED as epicentre |

| 89 | Most senior emergency physician directs traffic/surgeons overseas area—triage not by most senior personnel |

| 90 | Volunteer surges difficult to manage but can be helpful |

| 91 | Need to increase morgue facilities |

| 92 | Improved alert system |

| 93 | Clear communication, organization and decision making skills |

| 94 | Robust and simple organisation and command |

| Post-incident | |

| 95 | Clinical representation at strategic level to facilitate cooperation between networks/regions |

| 96 | Support from neighbouring regions during terror |

| 97 | Develop a network of capacities and capabilities which is constantly updated |

| 98 | Gaps in provision of rehab services—acute phase vs long term phase |

| 99 | Access to legal and financial support for victims |

| 100 | Importance of evaluation and improvement of emergency plans |

| 101 | Analysis based on past incidences |

| 102 | Early debriefing |

| 103 | Quickest possible return to normality |

| 104 | Quick return to normality—ongoing care for normal patients |

| Lessons learned | Communication |

|---|---|

| Pre-incident | |

| 1 | Terror awareness—train the public—communicate |

| 2 | Establish Improved alert system |

| 3 | Public engagement and empowerment—communication and teaching |

| 4 | Clear communication, organization and decision making skills |

| During the incident | |

| 6 | Delays in communication should be expected |

| 7 | Radio Equipment vital as often all other communication lines lost |

| 8 | Importance of reliable information |

| 9 | Effective intra-hospital communication |

| 10 | Constant update on resources and limitation of all hospitals |

| 11 | Better communication between disaster agencies |

| 12 | Importance of communication between different rescue teams |

| 13 | Identification vests help communication and command structures—clear roles |

| 14 | Intra and interhospital communication is important |

| 15 | Importance of public communication centre |

| 16 | Communication between disaster scene/EMS and hospital is often big problem |

| 17 | Use of protected phone lines and walkie-talkies |

| 18 | Early information/communication from site to assess severity |

| 19 | Early on radio/bleep system—later use of mobile phones possible |

| 20 | Clear, well-structured communication and coordination |

| 21 | Increase supplies through early communication with vendors |

| 22 | Bleeps and cable phones as cell service is often unreliable |

| 23 | Multiple scenes create difficult command and communication problems |

| 24 | Communication between rescue services is vitally important |

| 25 | Do not solely rely on mobile phones—danger of collapse |

| 26 | Establish a public information centre close to hospital |

| 27 | Use robust communication methods |

| 28 | Communication lines often fail—be prepared |

| 29 | Management of uninjured survivors and relatives—good communication |

| 30 | Concentrate initially on relaying as much information as possible |

| 31 | Important information: (1) the nature of the event (2) the estimated number and severity of casualties; (3) the exact location of the event; (4) the primary routes of approach and evacuation; (5) estimated time of arrival at the nearest hospital |

| 32 | Use megaphones if adequate |

| 33 | Turn off all non-critical mobile cell phones during terror event (government implementation) |

| 34 | Communication centre for relatives |

| 35 | No media inside hospital—media centre set up |

| 36 | Importance of communication mechanisms during terror |

| 37 | Communication with public—use of media |

| 38 | Good telecommunication system—with backup options |

| 39 | Create database of victims/casualties |

| 40 | Importance of communication/coordination between incident site and hospitals |

| 41 | Importance of even distribution between hospitals—communication |

| 42 | Early press briefings to stop hysteria |

| 43 | Communication failure will always happen |

| 44 | Good care despite communication failure—hence senior well-trained personnel |

| 45 | Communication-use of standardised operational terms |

| 46 | Good in-hospital communication between specialties |

| 47 | Decision making without all information—lack of communication unavoidable |

| 48 | Public Reassurance through good communication |

| 49 | Restricted internet access to avoid breakage |

| 50 | Communication with relatives |

| 51 | Better communication of patient information between prehospital and hospital setting |

| 52 | Communication channel between police, EMS and hospitals |

| 53 | Public relations and communication |

| 54 | Readiness of hospitals—good communication and preparation |

| 55 | Mutual communication systems |

| 56 | Better Integration of operators of different rescue chains + communication |

| 57 | Provide patient lists to police to ease communication/information gathering for relatives |

| 58 | Importance of patient hand over communication |

| 59 | Effective communication—improve information sharing |

| 60 | Sharing of corporate knowledge—communication of information |

| 61 | Good communication and situational awareness—use liaison officers |

| 62 | Media policy and communication—robust and well informed |

| 63 | Consider radio control mechanisms |

| 64 | Confidentiality when it comes to communication with media |

| 65 | Security and privacy issues when it comes to media communication |

| 66 | Quick and clear communication with relatives—to avoid information gathering via social media |

| Lessons learned | Preparedness/planning/training |

|---|---|

| Pre-incident | |

| 1 | Practise/drill—important! |

| 2 | Terror awareness—train the public |

| 3 | Trained prehospital personnel is a crucial factor |

| 4 | Update disaster plans—train them |

| 5 | Different sort of drills to prepare (manager drills/full scale drills) |

| 6 | Training is most important |

| 7 | Have and follow a pre-existing plan—based on experience |

| 8 | Thorough good quality preparation |

| 9 | Good prehospital care systems improve survival |

| 10 | Training of triage to reduce over and under triage |

| 11 | Debrief early and in a structured way |

| 12 | Preparation for incidents and injury types |

| 13 | Be prepared: have 1–3 months supply of surgical disposables |

| 14 | All hospitals should be included in contingency planning |

| 15 | All hospitals should be prepared to act as evacuation hospital—drills and training |

| 16 | Importance of damage control concepts—training |

| 17 | Cancellation of all elective surgical procedure |

| 18 | Emptying of ICU and wards |

| 19 | Importance of planning, coordination, training, financial support and well equipped medical services |

| 20 | Clear out hospital during latent phase |

| 21 | Have a major incident plan—have it rehearsed |

| 22 | Analysis based on past incidences |

| 23 | Analysis of gaps between scenario and response needed |

| 24 | Pre-event preparedness crucial—extensive planning improve outcome |

| 25 | Train core of nurses in emergency medicine skills |

| 26 | Have an emergency plan even if not a level one trauma centre |

| 27 | Rehearsal of emergency plan |

| 28 | Every hospital should be prepared for a major incident with terrorist background -solid emergency plans in situ |

| 29 | Importance of thorough analysis and short fallings |

| 30 | Good mix between planning and improvisation |

| 31 | A major incident plan is necessary—on a local as well as regional level |

| 32 | Meticulous planning |

| 33 | Extensive education |

| 34 | Regular review of the contingency plans |

| 35 | Emergency and disaster preparation and planning is crucial |

| 36 | All hospitals should be ATLS trained and have major incident drills |

| 37 | Regional major incident plan to help allocate resources |

| 38 | Have and activate contingency plans soon |

| 39 | Be prepared for uncertainty and unsafe environment |

| 40 | Having experience best preparation for next incident |

| 41 | Training saves lives |

| 42 | Drills based on past experiences |

| 43 | Teaching/training/education—best preparation |

| 44 | Disaster training best preparation for reality—systematic multidisciplinary training/drills |

| 45 | Train for new pattern of injuries |

| 46 | Readiness of hospitals—good communication and preparation |

| 47 | Public engagement and empowerment—communication and teaching |

| 48 | Staff training in combat medicine—cooperation with the military |

| 49 | Greater investment, integration, standardisation of disaster medicine |

| 51 | Multidisciplinary training—including police/fire service |

| 52 | Monthly multidisciplinary trauma training |

| 53 | Train the public/police in first aid/bleeding control |

| 54 | Importance of evaluation and improvement of emergency plans |

| 55 | Emergency preparedness based on planning/training/learning |

| 56 | Competence through continuous planning/training/drills |

| 57 | Cooperation: teaching of medical staff by military |

| 58 | Teaching of trauma management to med students |

| 59 | Therapy of paediatric cases—training is essential |

| 60 | Anticipation and planning—Plan Blanc obligatory |

| 61 | Awareness of tactical threat—idea of hazardous area response team |

| 62 | Training in trauma management |

| 63 | Planning and training—the value of organised learning |

| 64 | National process for debriefing and lessons learned |

| 65 | Regional standards for training |

| Lessons learned | Command |

|---|---|

| During the incident | |

| 1 | Strict command and control structures with designated hierarchy |

| 2 | Establish incident command system/centre—this is important |

| 3 | Early command and control structure—be prepared to rebuild |

| 4 | Avoid improvisation in command structure |

| 5 | Identification vests help communication and command structures—clear roles |

| 6 | Most senior medical officer = commander |

| 7 | Prompt and vigorous leadership |

| 8 | Civil defence coordinates and has overall command—clear structure |

| 9 | Importance of chain of command |

| 10 | Command structures—medical director vs administrative director |

| 11 | Incident commander appoints: liaison officer; public information officer; personnel officer; logistics officer; data officer; medical command officer; patient/family information officer |

| 12 | Chain of command: most senior official from all important specialties plus hospital admin |

| 13 | Multiple scenes create difficult command and communication problems |

| 14 | Have experienced decision maker |

| 15 | Command and control—regular trauma meetings |

| 16 | Importance of EMS command centre |

| 17 | Accept chaos phase—command structures will follow |

| 18 | Importance of local command structures—most senior official = commander in chief |

| 19 | Communication/cooperation between managers of different EMS |

| 20 | Work within established command and control structures |

| 21 | Clear distinction between command/control and casualty treatment |

| 22 | Lead by senior clinicians |

| 23 | Effective decision making—command is crucial |

| 24 | Command structures need to be robust |

| 25 | EMS command structures are vital |

| 26 | Dual command—ambulance/tactical commander vs medical commander |

| 27 | Command and control vs collaboration—both important |

| 28 | Flexible leadership |

| 29 | Leadership through ER physicians |

| 30 | Central Command—Health emergencies crisis management centre |

| 31 | Central command in hospital—director of medical operations |

| 32 | Good crisis management/command important |

| 33 | Multidisciplinary management |

| 34 | Clear communication, organization and decision making skills vital |

| 35 | Robust and simple organisation and command |

| 36 | Crisis management based on knowledge and data collection |

| 37 | Solid command structures and leadership based on experience and knowledge |

| 38 | Tactical management—get an overview and do not get stuck in details |

| 39 | Leadership/coordination through experienced healthcare professionals |

| 40 | Tactical command post in safe zone |

| Lessons learned | Triage |

|---|---|

| Pre-incident | |

| 1 | Establish national triage guidelines |

| 2 | Improve triage skills |

| 3 | Reproducible triage standards |

| 4 | Triage according to three ECHO—coloured cards |

| 5 | Casualty disposition framework with an effective enhanced triage process |

| During the incident | |

| 6 | Priority is quick triage, evacuation and transport to hospital |

| 7 | Establish casualty collection points/triage simple and early |

| 8 | Multiple triage areas—staff with freelancers |

| 9 | Coloured tags for triage |

| 10 | Use START system—simple triage rapid treatment |

| 11 | Doctors not deployed in red zone -triage in safe zone |

| 12 | Triage by most senior personnel |

| 13 | In-hospital triage according to ATLS |

| 14 | Systematic planning for triage, stabilisation and evacuation to hospital through chain of treatment stations |

| 15 | Triage at a distant site to disaster |

| 16 | Importance of triage—good triager—absolute authority |

| 17 | Deploy small medical teams for 2nd triage |

| 18 | Senior general surgeon triages at hospital entrance |

| 19 | Triage on arrival at hospital entrance as prehospital triage not necessarily reliable |

| 20 | Rapid primary triage—evacuation of the critical ill to nearest hospital (evacuation hospital) for stabilisation |

| 21 | Beware of undertriage |

| 22 | Importance of triage at incident site |

| 23 | Importance of retriage at hospital |

| 24 | Importance of triage concepts in general—avoid undertriage |

| 25 | Primary in-hospital survey through surgeons and anaesthetists |

| 26 | Diligence in triage |

| 27 | Large amount of over triage—no negative consequences/overtriage does not kill |

| 28 | Establishment of triage areas in hospital |

| 29 | Tertiary survey day after |

| 30 | Repeated effective triage maintains hospital surge capacity |

| 31 | Idea to establish triage hospital |

| 32 | Rapid primary survey and triage—delay of secondary survey |

| 33 | Most senior emergency physician directs traffic/surgeons overseas area—triage not by most senior personnel |

| 34 | Prehospital as well as hospital triage is vitally important |

| 35 | Importance of good primary triage |

| 36 | Frequent reassessment and triage |

| 37 | Quick triage—scoop and run—repeated triage at hospital |

| 38 | Quick effective good basic triage—reduction of overtriage |

| 39 | Improved triage through physician/paramedic teams |

| 40 | Enough equipment but mainly quick triage and transport |

| 41 | Deliberate overtriage |

| 42 | Directed quick patient flow to relieve triage area |

| 43 | Inadequate triage results in critically injured patients—retriage is vital |

| 44 | Outside triage area—not in hospital |

| 45 | Triage: absolute vs relative emergencies |

| 46 | Crisis teams to organise triage |

| 47 | Continuous retriage—similar triage system preclinical and in hospital |

| 48 | Triage outside hot zone—no therapy in hot zone if not trained |

| 49 | Most important triage point: able to walk vs not able to walk |

| Lessons learned | Staffing |

|---|---|

| Pre-incident | |

| 1 | Deploy trained prehospital personnel |

| 2 | Staff imprints lessons from mini-disasters and use this experience |

| 3 | Establishment of human resource pools—especially with volunteers |

| 4 | Too few nurses—improve incentives |

| 5 | Description of relevant capabilities of the medical system |

| 6 | Staff training in combat medicine—cooperation with the military |

| 7 | Up-to-date list of available staffing important |

| During the incident | |

| 8 | Descale as soon as possible → rest time for staff |

| 9 | Staff Safety is a major concern |

| 10 | Freelancers are important but difficult to manage |

| 11 | Multiple triage areas—possible staffing with freelancers |

| 12 | Quick response—increase staffing as soon as possible |

| 13 | Maximal increase of staffing needed—most important factor |

| 14 | Forward deployment of anaesthetist—allows for continuity of care |

| 15 | Relieve staff after 8–12 h for breaks |

| 16 | Optimise utilisation of manpower and supplies |

| 17 | Primary survey through surgeons and anaesthetists |

| 18 | ED staffed with nurse/doctor combo at each bed |

| 19 | Gather information and personnel during latent phase |

| 20 | Helicopters to transport staff and equipment |

| 21 | Triple: anaesthetist trauma surgeon abdominal surgery lead assessment and allocation to definite care |

| 22 | Efficient staff allocation |

| 23 | Pre hospital physicians useful |

| 24 | Using tags for triage—no resuscitation efforts until enough staffing |

| 25 | Train core of nurses in emergency medicine skills |

| 26 | Different specialties (ENT/psych) needed |

| 27 | Spread out teams to attend more patients |

| 28 | Too much staff available in ER—overcrowding |

| 29 | Good care despite communication failure—hence senior well trained personnel |

| 30 | Triage by senior medical officers |

| 31 | Keep track of staff showing up |

| 32 | Keep personnel in reserve/on standby |

| 33 | Experienced staff is vitally important |

| 34 | Surge in equipment and staff vital |

| 35 | Safety of personnel—idea of SWAT paramedics—therapy under fire |

| 36 | Increase blood bank staff |

| 37 | Photography staff/service to document injury |

| Post-incident | |

| 38 | Follow up on personnel—psychological and physiological |

| Lessons learned | Patient flow and distribution |

|---|---|

| Pre-incident | |

| 1 | Large number of mildly injured patients need to be expected and swiftly dealt with |

| 2 | Provide enough equipment but tailor to quick triage and transport |

| During the incident | |

| 3 | Majority of survivors are self-rescuer |

| 4 | Establish safe way for self-rescuer/non invalid patients |

| 5 | Increase ICU capacity move patients and unlock new areas |

| 6 | Patient flow—division between different hospital to avoid overload/right patient to the right hospital |

| 7 | Fast forward casualty flow |

| 8 | Coordinated distribution of casualties to hospitals |

| 9 | Log of most severely injured patients and their whereabouts |

| 10 | Quick redistribution of patients to clear ER for new ones |

| 11 | Use recovery room for monitoring unstable patient |

| 12 | Second wave of patient transfer between hospitals to avoid resource overstretching |

| 13 | Misdistribution between hospitals is a huge problem |

| 14 | Unidirectional patient flow—quick emptying of ED—one way pathway of care |

| 15 | Walking wounded redirected to satellite areas |

| 16 | Early evaluation of patients by senior doctors—early estimation of ICU capacity/operating capacity needed |

| 17 | Transport off ICU patients to different hospitals needs to be thought of |

| 18 | Rapid removal from critically ill patients out of an unsafe environment |

| 19 | Transferring patients rapidly to definite care—rapid scene clearance |

| 20 | Consider the need for secondary transport (interhospital) |

| 21 | Distinction between circle 1 and circle 2 hospitals—direction of casualties accordingly |

| 22 | Quick evacuation of casualties—if stable enough severely injured patients to trauma hospitals |

| 23 | ED as epicentre—clear ED quick |

| 24 | Establish different treatment areas: fast track, psychiatric, major trauma, etc. |

| 25 | Primary evacuation of mildly injured patients to distant hospitals |

| 26 | Treat patient in level 2 trauma centres and only transfer if necessary to level 1 trauma centres |

| 27 | Divert non urgent patients to hospitals further away from incident site |

| 28 | Survivor reception centres to alleviate hospitals |

| 29 | Primary and balanced distribution between hospitals |

| 30 | Timely evacuation out of unsafe zone |

| 31 | Overload of patients at close by hospitals is huge problem |

| 32 | Fast track route for minor injuries |

| 33 | Patient flow—evacuation to cold zones |

| 34 | Directed quick patient flow to relieve triage area |

| 35 | Secondary patient flow according to capacity and specialty |

| 36 | Relocation of current patients |

| 37 | Cooperation between hospitals and trauma centres—recognise your limits and transfer |

| 38 | Tourniquet use und quick transfer to definite care |

| 39 | Track patients through hospital is a difficult task |

| 40 | Casualty clearing station—part of patient flow |

| 41 | Casualty disposition framework with an effective enhanced triage process |

| 42 | Safe transfer and handover of existing patients |

| Lessons learned | Cooperation and multidisciplinary approach |

|---|---|

| Pre-incident | |

| 1 | Common goal is an important benefit |

| 2 | Cross organisational planning important |

| 3 | Communication channel between police, EMS and hospitals |

| 4 | Staff training in combat medicine—cooperation with the military |

| 5 | Awareness of tactical threat—idea of hazardous area response team |

| 6 | Sharing of corporate knowledge—communication of information |

| 7 | Clinical representation at strategic level to facilitate cooperation between networks/regions |

| 8 | Simultaneous search/rescue/treatment |

| During the incident | |

| 9 | Better communication between disaster agencies is important |

| 10 | Importance of communication between different rescue teams |

| 11 | Especially trauma patients need teamwork and good cooperation (surgery/anaesthetic) |

| 12 | Cooperation of the entire medical system—prehospital as well as hospital |

| 13 | Increase supplies through early communication with vendors |

| 14 | Collaboration with police to deliver supplies |

| 15 | Police command centre within hospital |

| 16 | Chain of command: most senior official from all important specialties plus hospital admin |

| 17 | Communication between rescue services vitally important |

| 18 | Good teamwork is crucial |

| 19 | Triple: anaesthetist, trauma surgeon abdominal surgeon lead assessment and allocation to definite care |

| 20 | Multidisciplinary meetings |

| 21 | Most senior emergency physician directs traffic/surgeons overseas area—triage not by most senior personnel |

| 22 | Flexibility of services important—interaction/cooperation important |

| 23 | Possibility for emergency services to cooperate and communicate |

| 24 | Combined activation of major incident plans (all EMS services) |

| 25 | Joint field command post |

| 26 | Cooperation and communication between hospitals and all emergency services |

| 27 | Dual surgical command-triage |

| 28 | Cooperation between police and EMS |

| 29 | Methodical multidisciplinary care delivery |

| 31 | Good cooperation/collaboration between services is vital |

| 32 | Good interdisciplinary cooperation is vital |

| 30 | Command and control vs collaboration—both important |

| 33 | Multidisciplinary care saves lives |

| 34 | Cooperation between EMS and police/fire services |

| 35 | Multidisciplinary training—including police/fire service |

| 36 | Multi-professional networks/interaction including mental health |

| 37 | Cooperation between hospitals and trauma centres—recognise your limits and transfer |

| 38 | Crucial interaction/communication between hospital/police/municipalities |

| 39 | Provide patient lists to police to ease communication/information gathering for relatives |

| 40 | Good communication between incident site and hospital |

| 41 | Law enforcement medical commander—cross over between specialties/cooperation |

| 42 | Cooperation between civilian rescue teams and military |

| 43 | Good communication and situational awareness—use liaison officers |

| 44 | Coordination and collaboration should be planned and practised at intra/inter-regional, multiagency and multiprofessional levels |

| 45 | Support from neighbouring regions during terror |

| Lessons learned | Equipment and supplies |

|---|---|

| Pre-incident | |

| 1 | Functioning equipment is vitally important (broadband internet) |

| 2 | Constant resource evaluation |

| 3 | Combat medical care—reduced level of treatment per patient due to resource insufficiencies |

| 4 | Need for appropriate equipment + supplies |

| 5 | Increase supply of available blood products |

| 6 | Mobile multiple casualty carts and disaster supply carts with equipment are helpful |

| 7 | Increase supplies through early communication with vendors |

| 8 | Assess Need for chemical and radiological monitors |

| 9 | Description of relevant capabilities of medical system |

| 10 | Provide megaphones |

| 11 | Provide protective personal equipment |

| 12 | Install mobile mass casualty vehicles with additional supplies |

| 13 | Increase and storage of supplies |

| 14 | Supply chains need to be reliable/organised well |

| 15 | Regional major incident plan to help allocate resources |

| During the incident | |

| 16 | Restrict laboratory and radiology testing |

| 17 | Protection of medical assets |

| 18 | Increase equipment—prep minor OR for major casualties |

| 19 | Rapid primary triage—only evacuation of the critical ill to nearest hospital (evacuation hospital) for stabilisation—to avoid resource overstretching |

| 20 | Second wave of patient transfer to avoid resource overstretching |

| 21 | Optimise utilisation of manpower and supplies |

| 22 | Collaboration with police to deliver supplies |

| 23 | Helicopters to transport staff and equipment |

| 24 | Basic equipment important and needed |

| 25 | Use of radio systems |

| 26 | Basic first aid kits on buses/trains |

| 27 | Allocation of resources difficult especially with multiple incidents |

| 28 | Enough equipment but mainly quick triage and transport |

| 29 | More advanced equipment including CBRN |

| 30 | Allocate resources to correct diagnosis |

| 31 | Extensive use of tourniquet |

| 32 | Challenge of technology-equipment may fail |

| 33 | Back up resources—mobilise equipment and staff |

| 34 | Use of clotting devices/tourniquet |

| 35 | Surge capacity in equipment and staff is vital |

| 36 | Avoid main gate syndrome—overwhelmed resources at the closest hospital |

| 37 | Regional resource mobilisation is vital |

| Lessons learned | Medical treatment + type of injury |

|---|---|

| Pre-incident | |

| 1 | Use critical mortality rate as indicator for assessing medical care |

| 2 | Terror attack cause different/specific injury patterns |

| 3 | Except many blast injuries |

| 4 | Average ISS Score of ICU admission |

| 5 | Professional abilities are important |

| 6 | Train for new pattern of injuries |

| 7 | Medical management and knowledge vitally important |

| 8 | Stop the bleeding—tourniquet use—train as basic first aid |

| 9 | Integration of TCCC to ATLS |

| 10 | Improve therapy of paediatric cases—training |

| During the incident | |

| 11 | Evacuate patients as soon as possible |

| 12 | Rapid treatment is important |

| 13 | Use START system—simple triage rapid treatment |

| 14 | Combat medical care—reduced level of treatment per patient due to resource insufficiencies |

| 15 | Early aggressive resuscitation predicts survival |

| 16 | Available surgical capacity needs to be increased |

| 17 | Restrict laboratory and radiology testing—minimal investigations |

| 18 | Only damage control surgery—the rest must wait |

| 19 | Medical treatment dependent on type of attack |

| 20 | Rapid provision of definite care |

| 21 | Therapy according to ATLS guidelines |

| 22 | Predominance of minor injuries during terrorist bombings (secondary/tertiary blast effect) and worried well patients |

| 23 | Critical injury appears roughly in 1/3rd of the cases |

| 24 | Blast injury results often in immediate death—if not there is often a combination with ear injury |

| 25 | Only 5% ISS > 15; 2% ISS > 25 |

| 26 | Main injuries: blunt trauma, blast injury, penetrating wounds, burns |

| 27 | Rapid removal from critically ill patients out of an unsafe environment—scoop and run Therapy |

| 28 | Damage control treatment and mind set to increase surge capacity |

| 29 | Using tags for on scene triage—no resuscitation efforts until enough staffing |

| 30 | Treat patient in level 2 trauma centres and only transfer if necessary to level 1 trauma centres |

| 31 | Damage control treatment—no provision of individual definite care |

| 32 | Use ATLS/PHLTS standards |

| 33 | Use tactical combat casualty care + haemorrhage control |

| 34 | Roughly 10% suffer major injury |

| 35 | Schedule operations according to urgency |

| 36 | Extensive use of tourniquet |

| 37 | Offer immediate access to OR |

| 38 | Patient therapy/flow: tourniquet use und quick transfer to definite care |

| 39 | Safety vitally important—extent of therapy based on situational safety |

| Lessons learned | Zoning and scene safety |

|---|---|

| Pre-incident | |

| 1 | Full personal protective equipment and knowledge of the prehospital environment helpful |

| 2 | Beware of hospitals being soft targets |

| 3 | Safety of personnel—idea of SWAT paramedics—therapy under fire |

| 4 | Awareness of tactical threat—idea of hazardous area response team |

| During the incident | |

| 5 | Security at all hospital entrances—consider immediate lockdown |

| 6 | Simultaneous search/rescue/treatment—beware of security risks of this concept |

| 7 | Scene safety and scene control—beware of loss of rescue personnel—safety first |

| 8 | Beware second hit principle—protect trained personnel |

| 9 | Establish a safe way for self-rescuer |

| 11 | Safety of staff paramount |

| 12 | Rapid removal from critically ill patients out of an unsafe environment |

| 13 | Scene safety—important but huge problem hence rapid evacuation |

| 14 | Awareness for explosive devices being carried into hospital |

| 10 | Doctors not in red zone—triage in safe zone |

| 15 | Continuous assessment of scene safety |

| 16 | Safety first—triage/command outside danger zone |

| 17 | Manage uncertainties and scene |

| 18 | Evacuation problematics due to scene and geographical environment |

| 19 | Importance of scene safety and terror control |

| 20 | Scene safety—secondary attack/collapsing buildings/explosive Device |

| 21 | Conventional rescue teams out of danger zone |

| 22 | Operating capacity within on scene dressing station-tactical physicians as concept |

| 23 | Scene safety—zoning (exclusion zone) |

| 24 | Scene safety: develop best compromise btw safety of responders, immediate care and fast extraction |

| 25 | Triage outside hot zone—no therapy in hot zone if not trained |

| 26 | Tactical command post in safe zone |

| 27 | Scene safety cannot be guaranteed |

| 28 | Safety vitally important—extent of therapy based on situational safety |

| 29 | Challenges of being in the hot zone—multifaceted and continuously evolving |

| 30 | Recognition of situational aspect and severity + complexity—evolving risk |

| Lessons learned | Psychiatric support |

|---|---|

| Post-incident | |

| 1 | Early psychiatric help is important |

| 2 | Site for acute stress disorder therapy needed |

| 3 | Good psychological support is necessary and important |

| 4 | Importance of post-traumatic stress disorder treatment groups |

| 6 | Do not underestimate the psychological and physical effects on health care workers |

| 7 | Psychological support for emergency services/healthcare worker/staff |

| 8 | Debriefing as stress relief |

| 9 | Psychiatric support before discharge for all patients |

| 10 | Psychological support for mildly injured patients |

| 11 | Set up survivor groups/psychological support |

| 13 | Psychological support to reduce long term impact of terrorism |

| 14 | Establishment of mental health counselling for staff |

| 15 | Psychiatric illness as hazard for emergency personnel |

| 16 | Establish psychological support centre |

| 17 | Low PTSD with good preparation, debriefing and high role clarity |

| 18 | Psychological follow up for staff and patients |

| 19 | Multiprofessional networks/interaction inclusive Mental Health |

| 20 | Everyone should be seen by psychiatric experts |

| 21 | Psychological care—Increase psychological support short and long term |

| 22 | 1/3 of victims develop post traumatic stress disorder (PTSB) |

| 23 | Psychological support—informal and formal Treatment |

| 24 | Improve bereavement support |

| 25 | Psychological first aid approach including self help |

| 26 | Bereavement nurses—24/7 access in the first 48 h |

| 27 | Monitor high risk groups of PTSD |

| Lessons learned | Record keeping |

|---|---|

| Pre-incident | |

| 1 | Create database of victims/casualties |

| 2 | Identification difficulties of victims—improve documentation to allow quicker identification |

| 3 | Improvement in identification: INTERPOL Disaster Victim Identification Standard |

| 4 | Standardised documentation at regional level/need for national casualty identification system |

| 5 | Patient identification difficult task—standardized identification and documentation systems |

| During the incident | |

| 6 | Written documentation strapped to patient |

| 7 | Early start of data collection |

| 8 | Good record keeping is essential |

| 9 | Lead agency to solely deal with record keeping |

| 10 | Importance of data collection of casualties at the scene |

| 11 | Importance of documentation—which patient has already been triaged |

| 12 | Better communication of patient information between prehospital and hospital setting |

| 13 | Detailed documentation of the disaster operation |

| 14 | Crisis management based on knowledge and data collection |

| 15 | Track patients through hospital—this is a difficult task |

| 16 | Photography staff/service to document injury |

| 17 | Importance of patient identification to allow for family reunification/bereavement |

| Lessons learned | Role understanding |

|---|---|

| 1 | Clear identification methods of roles—tags/vests—helps communication and command structures |

| 2 | Dedicated roles with clear defined duties during event—command and control physician; discharge/ patient flow organiser; ED supervisor |

| 3 | Assigned roles in disaster plan |

| 4 | Flexibility but clear roles |

| 5 | Know your capabilities/professional role |

| 6 | Low post traumatic stress disorder with good preparation, debriefing and high role clarity |

| 7 | Clear defined roles help to give security and confidence and improve outcome |

| Lessons learned | Team spirit |

|---|---|

| 1 | Keep team spirit up |

| 2 | Form coalition to keep up spirit and improve |

| 3 | Staff solidarity and professionalism vital |

| 4 | Public engagement and empowerment—communication and teaching |

| 5 | Professionalism and team spirit important for success |

| 6 | Mutual support important |

Discussion

This systematic review is the first of its kind to review the vast amount of literature dealing with lessons learned from terror attacks. It thus contributes to a better understanding of the consequences of terror attacks since 2001. It also brings order to the multitude of defined lessons learned and allows for an overview of all the important findings.

Our data has shown that, despite the difference in attacks, countries, social and political systems and casualties involved, many of the lessons learned and issues identified are similar. Important to note was the fact that time of article release did not relate to content. Many articles written after the London attacks in 2005 formulated similar if not the same lessons learned as articles written in 2017 about Utoya [36, 52]. This is a major point of concern as it indicates, that despite the knowledge about the issues and the existence of already developed, excellent concepts [56, 79, 80], their successful implementation and continuous improvements seem to be lacking.

One of these well-developed concepts, the Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC), began as a special operations medical research programme in 1996 and is now an integral part of the US Army's trauma care [79]. The Committee on TCCC, which was established in 2001, ensures that the TCCC guidelines are regularly updated [79]. Many of the lessons learned listed in our review are an integral part of these guidelines and are addressed with concrete options for action. For Example, the principles of Tactical Evacuation Care provide detailed instructions on the management of casualties under the special conditions of evacuation from a danger zone [81]. Moreover, the lack of knowledge on how to deal with injuries caused by firearms or explosive devices, which was mentioned in many articles, could be remedied by a consistent integration of the TCCC guidelines into the training and drills of emergency service staff.

Another concept that deals with the management of terrorist attacks and mass shootings is the Medical Disaster Preparedness Concept “THREAT”, which was published after the Hartford Consensus Conference in 2013 [56]. The authors defined seven deficits as lessons learned and recommended concrete measures to address them. These lessons were included in our review and were mentioned in one form or the other in many of the articles. The defined THREAT concept components were:

T: Threat suppression

H: Haemorrhage control

RE: Rapid extraction to safety

A: Assessment by medical providers

T: Transport to definitive care.

Consistent implementation of these points in training and practice would be an important step towards improving preparation for terror attacks.

A good example of the successful implementation of an interprofessional concept is the 3 Echo concept (Enter, Evaluate, Evacuate) [80]. It was developed and introduced with the goal to optimize the management of mass shooting incidents. At the beginning of concept development stood the identification of deficits. Those deficits correspond to those that we found in the presented systematic review. The introduction of the concept in training and practice has led to successful management of a mass shooting event in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA in 2012 [80]. This outlines once again the importance of translating lessons learned into concrete concepts, to integrate them into the training and to practice them regularly in interprofessional drills. Just as the 3 Echo concept is based on interprofessional cooperation, the Joint Emergency Services Interoperability Principles (JESIP) project is also based on this principle [82]. It is the standard in Great Britain for the interprofessional cooperation of emergency services in major emergencies or disasters. Through simple instructions and a clear concept, both the aspect of planning and preparation as well as the concrete management of operations are taken care of [82].

In interpreting the lessons learned in this systematic review, the question arises whether they are specific to terrorist attacks. Our review deals exclusively with lessons learned from terrorist attacks. Other publications, however, systematically addressed the management of terrorist and non-terrorist mass shootings and disasters. Turner et al. reported the results of a systematic review of the literature on prehospital management of mass casualty civilian shootings [83]. The authors identified the need for integration of tactical emergency medical services, improved cross-service education on effective haemorrhage control, the need for early and effective triage by senior clinicians and the need for regular mass casualty incident simulations [83] as key topics. Those correspond congruently with the lessons learned from terrorist attacks that were found and presented in this systematic review.

Hugelius et al. performed a review study and identified five challenges when managing mass casualty incidents or disaster situations [84]. These were “to identify the situation and deal with uncertainty”, “to balance the mismatch between contingency plan and reality”, “to establish functional crisis organisation”, “to adapt the medical response to actual and overall situation” and “to ensure a resilient response” [84]. The authors included 20 articles, of which 5 articles dealt with terror and mass shooting (including the terror attacks in Paris and Utoya). Although only 25% of the included articles dealt with terrorist attacks, the lessons learned are again very comparable to the results of this systematic review.

Challen et al. published the results from a scoping review in 2012 [11]. The authors stated that “although a large body of literature exists, its validity and generalisability is unclear” [11]. They concluded that the type and structure of evidence that would be of most value for emergency planners and policymakers has yet to be identified. If trying to summarise the development since that statement it can be assumed that on one hand sound concepts have been developed and implemented. On the other hand however, the lessons learned in recent terror attacks still emphasize similar issues as compared to those from the beginning of the analysis in 2001, showing that there is still work to be done. It should be mentioned at this point, that there was a federal conducted evaluation process in Germany after the European terror attacks in 2015/2016. The lessons learned were published in 2020 by Wurmb et al. and were very comparable to those of this systematic review [85]. Furthermore the terror and disaster surgical care (TDSC®) course was developed in 2017 by the Deployment, Disaster, Tactical Surgery Working Group of the German Trauma Society to enhance the preparation of hospitals to manage mass casualty incidents related to terror attacks [86]. Finally it is important to mention, that hospitals and rescue systems must prepare not only for terrorist attacks, but also for a wide spectrum of disasters. Ultimately, this is the key to increased resilience and successful mission management.

Limitations

This systematic review has several limitations. Due to the vast amount of information only PubMed was used as a source. From the authors' point of view, this is a formal disadvantage, but it does not change the significance of the study as in contrast to the question of therapy effectiveness or the comparison of two forms of therapy, the aim here is to systematically present lessons learned. To get even more information, the data search could have been extended to other databases (e.g. Cochrane Library, Web of science) and the grey literature. Given the number of included articles, it is questionable whether this would have significantly changed the central message of the study. It is even possible that this would have made a systematic presentation and discussion even more difficult. CBRN attacks have been excluded from the research. The reason for that was that many special aspects have to be taken into account in these attacks. Nevertheless CBRN attacks are an important topic, which would need further exploration in the future. The restriction to OECD countries certainly causes a special view on the lessons learned and is thus also a source of bias. However, the aim was to look specifically at countries where terror attacks are a rather rare event and rescue forces and hospitals are often unfamiliar with managing these challenges. Special injury patterns associated with terror attacks were not considered. This reduces the overall spectrum of included articles, but from the authors' point of view, a consideration of these would have exceeded the scope of this review.

Conclusion

The first thing that stands out is that most lessons learned followed a certain pattern which repeated itself over the entire time frame considered in the systematic review. It can be assumed that in many cases it is therefore less a matter of lessons learned than of lessons identified. Although sound concepts exist, they do not seem to be sufficiently implemented in training and practice. This clearly shows that the improvement process has not yet been completed and a great deal of work still needs to be done. The important practical consequence is to implement the lessons identified in training and preparation. This is mandatory to save as many victims of terrorist attacks as possible, to protect rescue forces from harm and to prepare hospitals and public health at the best possible level.

Author contributions

All authors contributed substantially to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by NS and TW. The first draft of the manuscript was written by NS and TW and all authors commented on previous and following versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work. No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript. No funding was received for conducting this study. No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Nora Schorscher, Email: Schorscher_N@ukw.de.

Maximilian Kippnich, Email: Kippnich_M@ukw.de.

Patrick Meybohm, Email: Meybohm_P@ukw.de.

Thomas Wurmb, Email: Wurmb_t@ukw.de.

References

- 1.Vienna shooting: Gunman hunted after deadly 'terror' attack. BBC News. 03.11.2020.

- 2.Keskinkılıç OZ. Hanau istüberall. Panorama. 19.02.2021.

- 3.Kar-Gupta S. Driver who rammed Paris police pledged allegiance to Islamic State: prosecutor. Reuters Media. 28.04.2020.

- 4.Brewis H. ISIS claims responsibility for Streatham terror attack carried out by Sudesh Amman. Evening Standard. 03.02.2020.

- 5.Park CL, Langlois M, Smith ER, Pepper M, Christian MD, Davies GE, Grier GR. How to stop the dying, as well as the killing, in a terrorist attack. BMJ. 2020;368:m298. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsch M, Carli P, Nizard R, Riou B, Baroudjian B, Baubet T, et al. The medical response to multisite terrorist attacks in Paris. Lancet. 2015;386:2535–2538. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haug CJ. Report from Paris. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2589–2593. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1515229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Philippe J-M, Brahic O, Carli P, Tourtier J-P, Riou B, Vallet B. French Ministry of Health's response to Paris attacks of 13 November 2015. Crit Care. 2016;20:85. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1259-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carli P, Pons F, Levraut J, Millet B, Tourtier J-P, Ludes B, et al. The French emergency medical services after the Paris and Nice terrorist attacks: what have we learnt? Lancet. 2017;390:2735–2738. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goralnick E, van Trimpont F, Carli P. Preparing for the next terrorism attack: lessons From Paris, Brussels, and Boston. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:419–420. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Challen K, Lee ACK, Booth A, Gardois P, Woods HB, Goodacre SW. Where is the evidence for emergency planning: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:542. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fattah S, Rehn M, Lockey D, Thompson J, Lossius HM, Wisborg T. A consensus based template for reporting of pre-hospital major incident medical management. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2014;22:5. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-22-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wurmb T, Justice P, Dietz S, Schua R, Jarausch T, Kinstle U, et al. Qualitätsindikatoren für rettungsdienstliche Einsätze bei Terroranschlägen oder anderen Bedrohungslagen : Eine Pilotstudie nach dem Würzburger Terroranschlag vom Juli 2016 [Quality indicators for rescue operations in terrorist attacks or other threats : a pilot study after the Würzburg terrorist attack of July 2016] Anaesthesist. 2016;2017(66):404–411. doi: 10.1007/s00101-017-0298-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roccaforte JD. The World Trade Center attack. Observations from New York's Bellevue Hospital. Crit Care. 2001;5:307–309. doi: 10.1186/cc1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez C, Gonzalez D. The World Trade Center attack: doctors in the fire and police services. Crit Care. 2001;5:304–306. doi: 10.1186/cc1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook L. The World Trade Center attack: the paramedic response: an insider's view. Crit Care. 2001;5:301–303. doi: 10.1186/cc1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamber PS, Vincent J-L. The World Trade Center attack: lessons for all aspects of health care. Crit Care. 2001;5:299–300. doi: 10.1186/cc1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]