Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) and neurologic deficits are often unable to provide consent and excluded from emergency research participation. Experiences with exception from informed consent (EFIC) to facilitate research on potentially life-saving emergency interventions are limited. Here, we describe our multifaceted approach to EFIC approval for an ongoing randomized clinical trial that compares sedation versus general anesthesia (SEGA) approaches for endovascular thrombectomy during AIS.

METHODS:

We published a university clinical trial website with EFIC information. We initiated a social media campaign on Facebook within a 50 mile radius of Texas Medical Center. Advertisements were linked to our website, and a press release was issued with information about the trial. In-person community consultations were performed, and voluntary survey information was collected.

RESULTS:

A total of 193 individuals (65% female, age 46.7 ± 16.6 years) participated in seven focus group community consultations. Of the 144 (75%) that completed surveys, 88.7% agreed that they would be willing to have themselves or family enrolled in this trial under EFIC. Facebook advertisements had 134,481 (52% females; 60% ≥45 years old) views followed by 1,630 clicks to learn more. The website had 1130 views (56% regional and 44% national) with an average of 3.85 min spent. Our Institutional Review Board received zero e-mails requesting additional information or to optout.

CONCLUSION:

Our social media campaign and community consultation methods provide a significant outreach to potential stroke patients. We hope that our experience will inform and help future efforts for trials seeking EFIC.

Keywords: Acute stroke therapy, clinical trial, community consultation, emergency consent, endovascular therapy, exception from informed consent, focus group, social media, stroke

Introduction

Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) affects someone new in the United States approximately every 40 s and is the second leading cause of death worldwide.[1] The time to revascularization has been shown to play a significant role in the recovery of symptoms; hence, time metrics for stroke have received significant attention, and management protocols have been developed to improve overall care.[1,2] In addition to the stringent time metrics, AIS is a challenging disease to study because victims have impaired ability to understand and communicate decisions and choices about their participation in clinical trials. This makes it especially difficult to effectively and reliably conduct clinical trials to evolve our health-care systems while simultaneously employing good clinical practice.[3]

When patients present to the emergency department with a large vessel occlusion (LVO), they are often unable to provide consent and are therefore excluded from emergency research participation, challenging the ethical principle of justice. Families and other legally authorized representatives (LAR) are often not at the bedside to provide consent for enrollment in clinical trials. Among other perceived benefits and harms, excluding patients may lead to study population changes with pseudovariations in demographics, resulting in a nonrepresentative or nonencompassing study cohort. Arguments have been made over the past two decades about whether an exception from informed consent (EFIC) is ethically justifiable, and if there is a need to evaluate EFIC against the actual patient's or LAR's consent decision.[4,5]

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued guidance for EFIC to facilitate research on potentially life-saving interventions in emergencies, and the latest (April 2013) version of this guideline is available on the FDA's website for Institutional Review Boards (IRB). However, there remains to be no explicit criteria or a particular quantifiable goal to satisfy EFIC. A recent meta-analysis of 45 EFIC studies also suggested that a better justification and presentation of clinical research would help to educate the medical community about the ethical and scientific concerns surrounding EFIC.[6,7] There has been further emphasis on the justification of applying EFIC with nonlife-threatening conditions and the lack of established treatment guidelines and protocols in those cases.[4] For our stroke trial, the SEGA Trial (Sedation versus General Anesthesia for Endovascular Therapy [EVT] in AIS – A Randomized Comparative Effectiveness Trial, Clinicaltrials.gov NCT-03263117), we saw the need to implement EFIC to ensure efficient and unbiased patient enrollment as well as to minimize logistic impracticability for the overall trial recruitment, since every minute counts in emergency stroke therapy. To obtain EFIC, we developed a multistep approach with the assistance of our IRB.

In this paper, we wish to present our experience on EFIC acquisition in our center that can be used as a guide for upcoming or ongoing (multicenter) prospective emergency clinical trials in cerebrovascular diseases.

Methods

We present the essential steps in our EFIC acquisition for the conscious sedation versus general anesthesia (SEGA) trial. Together with our IRB, we utilized a multifaceted approach to inform residents within our metropolitan area about EFIC in our SEGA stroke trial. Briefly, the SEGA trial is designed to determine if there is any significant difference in functional outcome between the use of conscious sedation versus general anesthesia during EVT for AIS patients with a proximal LVO. Patients are screened in the emergency department and all procedures follow the standard of care (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT-03263117).

Website

First, we began by publishing a university-created website that included information on EFIC regulations, our clinical trial aims, survey questions, and opt-out procedures. This website remained online for 3 months, for the duration of this campaign.

Facebook page

Subsequently, we advertised the trial on Facebook through a targeted page. The reason we utilized Facebook was due to its demographic profile with respect to reaching an adult population of various age groups and socioeconomic backgrounds, as well as for being the most frequently utilized social media platform.[8] This was intended for users within a 50-mile radius of our institution and 25-year-old hospital systems. Clicking on the advertisement directed users to the trial website hosted by our university, which contained a description of the SEGA trial, ways to learn more, and the procedure to opt-out. We tracked the number of clicks and the number of time participants spent on the linked trial website. Our research and IRB team has been open and prepared to answer all potential inquiries.

Press release

In collaboration with our university's office of communications, we issued a press release about our stroke trial and the link to our trial website. This was done to ensure additional publicity outside the internet to update and reach out specifically to AIS survivors in the medical community.

Community consultations

We held seven community consultations, in which we conducted voluntary surveys with focus groups. These focus groups consisted of stroke survivors, advisory councils, neuroscience intensive care unit family members, and associates of AIS patients. Alongside the trial program manager or the trial coordinator, at least one of our advisory committee members volunteered his or her time to attend these consultations to present the trial and the idea of EFIC. The anonymous voluntary surveys were collected from willing participants at the end of each community consultation. Surveys revealed how attendees were related to AIS patients and if they would feel comfortable having themselves or their families undergo this trial under EFIC rules [Supplemental Document (2MB, tif) ]. These anonymous surveys were also designed to help facilitate communication with insecure or unenthusiastic participants who may have felt hesitant to voice their comments or concerns aloud.

Protocol Implementation

The SEGA committee felt it was equally important to implement a protocol ensuring that standard of care was followed, minimizing the risks inherent in participating in the study. Multidisciplinary screening protocols were developed by the research team in collaboration with the stroke, neurointerventionalist, and anesthesia teams. Within the sensitive therapeutic window from last seen normal to EVT, our study was structured to work in parallel with the standard of care. Considering established stroke metrics, time from imaging to potential EVT operation as well as the time necessary to thoroughly introduce and obtain consent from an available LAR, led to the calculation of a parallel wait time of 15 min before proceeding with EFIC enrollment. When EFIC was applied, our protocol required a postoperative consent within 5 days, or before discharge, for continued study participation. All patients regardless of enrollment in the trial received standard of care treatment. Passive data acquisition was undertaken using clinical notes made during stroke hospitalization and routine institutional 3-month clinical follow-ups.

This research design was based on surveys, questionnaires, social media, and publicity values; therefore, we opted to employ descriptive statistics only. All FDA and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) requirements were achieved with the close guidance and instructions of our IRB.

Results

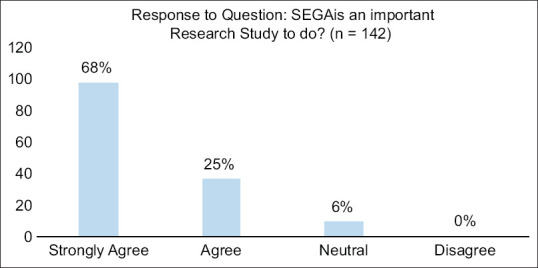

Between the months of June and September 2017, a total of 193 individuals (65% female, age 46.7 ± 16.6 years) participated in seven focus group community consultations. Of the 144 (75%) who completed surveys, 88.7% agreed that they would be willing to have themselves or a family member enrolled in this trial under EFIC. Moreover, 93.9% of participants who completed questionnaires during community consultations agreed that conducting this stroke research study was important [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Graph showing percentage of each response of the question: “SEGA is an important research study to do?” – A question proposed on the survey for community consultation. There was a total of 142 responses to this question. Of those responses, 133 (93.9%) responded that they Strongly agreed or agreed

Facebook advertisements had 134,481 views (52% female, 60% age ≥45 years), 1,630 clicks to “learn more” and 1130 website views (56% regional and 44% national [Table 1]). Users spent an average of 3 min 51 s on the webpage. Our IRB received zero e-mails requesting additional information or to opt out of potential EFIC enrollment.

Table 1.

Impact of Facebook advertisements showing the number of times the clinical trial link was shown and clicked

| Impact of Facebook ads by gender and age | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Impressions* | Unique link clicks | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Age | Females | Males | Unknown | Females | Males | Unknown |

| 25-34 | 6750 | 12,035 | 240 | 45 | 116 | |

| 35-44 | 16,824 | 17,700 | 729 | 127 | 185 | 5 |

| 45-54 | 13,431 | 12,252 | 495 | 155 | 159 | 2 |

| 55-64 | 15,695 | 10,899 | 455 | 195 | 154 | 1 |

| 65+ | 17,292 | 9331 | 357 | 216 | 114 | 2 |

*Number of times the ad was shown

Based on our findings, the IRB granted a 50-mile EFIC active radius from our institution at Texas Medical Center. During the first quarter of our enrollments in SEGA, EFIC-eligible centers falling within this radius collected a total of 16 (39%) preoperative signed informed consent forms in the emergency department. None of the 25 (61%) participants enrolled by EFIC have refused to give consent postprocedure or requested withdrawal from the study once enrolled.

Discussion

While the utilization of social media has been previously reported for the acquisition of EFIC in emergency trials, methodology and guidelines for prospective trials have not been clearly described.[6,7] Although there are numerous studies who have reported their experiences in EFIC acquisition and their use of social media, there is inconsistency in the methods.[9,10,11,12,13] Whether to do more or less is still a financial and logistic debate for the centers considering to perform campaigns for EFIC approval.[13,14] Moreover, there is no single acceptable way to accomplish or fulfill the community consultation requirements, nor will all studies require the same amount, type, or extent of community consultation activities.[15,16] Hence, the detail steps in our methodology are subject to change and further modification depending on the study type, target population, and geographical as well as social factors. We, therefore, believe that our paper is aiming to describe the multifaceted guideline combining multiple effective methods into one protocol while leaving room for adaptation to other future studies that may follow along our core steps. The development of this process was overseen and guided by our IRB.

Our initially anticipated geographic target within a 50-mile radius of our institution expanded nationally beyond our city limits among almost half of all Facebook advertisement participants. This may have been facilitated by the participants who could easily share the trial link with their friends and family or post it for public viewing. Although our initial focus and investment were directed locally, there is potential to utilize this approach for nationwide EFIC publicity with the Facebook advertisement to allow other SEGA sites to participate. We believe the feasibility of this approach and the ethical perspectives could be explored in future studies.

During the first quarter of SEGA enrollments, with an established and trained research staff, we were able to enroll 16 patients (39% of total enrollment) with an in situ informed consent. This is a reflection of our 15 min deadline, which was determined in addition to EFIC guidelines. While we could potentially enroll most or all of the cases under EFIC in compliance with FDA and HHS regulations, we have determined to designate a window of opportunity to respect additional ethical concerns for a late-arriving LAR. This is because of the debatable lack of any therapeutic window in emergency stroke management that limits the team to perform regulatory “reasonable efforts” such that once a patient qualifies for EVT the treatment must be initiated immediately, since there is a very limited time window for the providers to designate it for any research purposes.[17] We have, however, achieved this while maintaining recommended door to imaging and imaging to EVT timelines and without delaying any emergency procedures with a designated research staff working in parallel to the clinical team. Hence, even with a preoperative in situ consent, we were able to meet stroke metrics for SEGA enrolled patients within the Joint Commission recommendation across all time frames: door to imaging below 25 min (mean 15, median 13), door to interventional radiology (IR) suite below 70 min (mean 54, median 47), and IR suite arrival to groin puncture below 15 min (mean 13, median 13 min).

During our 1st year, the use of EFIC had allowed us to enroll 25 (61%) participants, more than double the number of total enrollments previously, who otherwise would not have been able to participate in SEGA. We have also noticed that enrollment numbers at EFIC approved centers have been less affected by logistic factors such as the inability to contact LAR inperson for an incapacitated patient or not having a research representative be on site for the after-hour code stroke cases or due to the current COVID-19 precautions in place. This increase in enrollment not only improves data validity and quality by reducing selection bias but may potentially reduce the overall study period, monitoring costs, sponsor costs, and overall time spent to conclude an emergency research trial.[4]

Moreover, we did not opt for a procedure consent over the phone instead of applying EFIC due to the acuity and sensitivity of the emergent situation during an AIS with a LVO. Obtaining consent over the phone may not be the most reliable source of LAR decisions when compared to in-person consent in a professional setting. Risks of consenting the LAR by phone during a life-threatening emergency have previously been described, as the reaction of LAR to the condition alone cannot be predicted and a consequential adverse event may occur (e.g. while driving).[7] Furthermore, a phone call from a research team may feel intrusive during this sensitive and emergent period, and the details of the conversation may be overwhelming. Providing a copy of the informed consent (by fax and E-mail) is also challenging and may not be feasible in urgent cases. It is difficult to expect LARs to clearly understand an emergency procedure over the phone or respond effectively to complex medical concepts with minimal personal interaction. Hence, in cases when we were able to speak to the LAR over the phone to explain the procedure and received their approval, we still enrolled the participant under the EFIC arm, which enforced the research team to seek postoperative consent for continued participation in the trial. This step could be a matter of discussion for further EFIC trial consents.

At the time of in-person postoperative consent, families were informed of the standard of care and that we did not change the care according to study participation. Hence, it is of significant importance to introduce the patient and/or LAR to the nature of the operation and how the trial involvement is relevant. Incidentally, our trial is a “minimum risk” comparative effectiveness trial for two standardly utilized anesthesia methods. Risks involved in other trials may impact the participant or LAR response to EFIC enrollment and subsequent continued participation following trial intervention. In our study, no participants or LARs withdrew their consent for continued participation after EFIC enrollment, when the details of the procedures were disclosed and all questions and concerns were answered.

Our experience was limited by the use of a single social media platform, leading to unpredictable numbers of users with different characteristics. Facebook was used alone without Twitter or other popular platforms due to the user demographics. Many private journals and news organizations have reported that Facebook is the largest social media platform with the greatest adult population. These resources cited Pew Research Center, one of the leading researchers on the American social and demographic trends.[8] Due to the lack of a published research comparing the effectiveness of different platforms, the reliability of these private reports may also pose a limitation. However, the consistency of these reports across different journals and companies suggest that Facebook is a preferred social media platform for reaching the adult population with stroke history. Utilizing multiple platforms may prove more effective in larger trials or to reach a broader target audience.

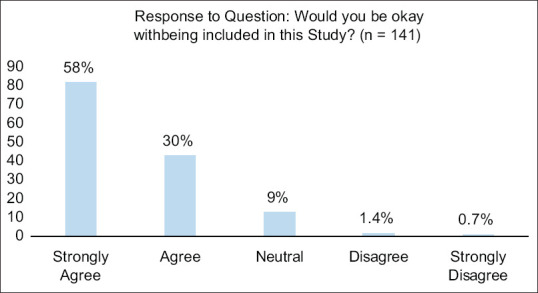

Among the 141 participants in the focus groups who completed the consultation surveys, there were two who disagreed and strongly disagreed with potentially participating in our trial [Figure 2]. These individuals could not be identified as our surveys were anonymous and collected separately from voluntary participants. However, the fact that there are individuals who feel against participating in a study that uses EFIC, despite adherence to guidelines, identifies ethical challenges regarding the concept of research without consent. We should also reiterate that the current trial involves minimal risk, which we considered a strong advantage. Acquiring a positive response and support from the community might be more challenging for more invasive or novel clinical trials, hence these campaigns may need to be carried out longer and with more resources under the adjudication of the study teams and their IRB(s).

Figure 2.

Graph showing percentage of each response of the question: “Would you be okay with being included in this study?” – A question proposed on the survey for community consultation. There was a total of 141 responses to this question. Of those responses, 125 (88.7%) responded that they strongly agreed or agreed

Centers seeking EFIC approval for their clinical trials should take advantage of their IRB support while also being careful in designing their trial protocols. While social media platforms and advertisement methods can be more promising in reaching out to targeted demographics and communities avoiding distance, time, or other logistic factors, focus groups, or community meetings should still be a part of the overall campaign to identify direct complaints if any, the perspectives, and also the level of understanding to the newly proposed trial. These in-person focus groups and community campaigns can subsequently help refine the social media campaigns. Future studies should also explore the use of multiple social media platforms and present more detailed guidance on specific cost, utility, and success measures for each method. Finally, studies should further explore and highlight the need for EFIC in research, and work to establish a universal protocol for EFIC approval that can be applied at all EFIC seeking centers.

Conclusion

EFIC plays a critical role in trials advancing our constantly evolving standard of care, especially with emergency research when planned participation is not feasible. Currently, there is no standardized approval process for EFIC. We hope that our multifaceted EFIC campaign experience will provide some insight for future standardization.

IRBs are fundamental experts in determining EFIC eligibility and filing legal documentation to the FDA or HHS. Based on our results and the limitations presented by each individual community consultation and public disclosure methods, we hope that our experience will inform and help future efforts for trials seeking EFIC.

Financial support and sponsorship

Stryker Neurovascular has granted research fund for the SEGA trial. The sponsor has had no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of this or any other SEGA trial data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

None of the authors have any financial relationships with commercial interests related to the content of this research, or any unlabeled or unapproved uses to disclose for this research.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge our Institutional Review Board team, the Research Compliance, Education and Support Services of University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston, Texas, for their support and availability throughout the process of EFIC acquisition.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, et al. “Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2017 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e229–445. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Musuka TD, Wilton SB, Traboulsi M, Hill MD. Diagnosis and management of acute ischemic stroke: Speed is critical. CMAJ. 2015;187:887–93. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hariton E, Locascio JJ. Randomised controlled trials – The gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: Randomised controlled trials. BJOG. 2018;125:1716. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rebers S, Aaronson NK, van Leeuwen FE, Schmidt MK. Exceptions to the rule of informed consent for research with an intervention. BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17:9. doi: 10.1186/s12910-016-0092-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sims CA, Isserman JA, Holena D, Sundaram LM, Tolstoy N, Greer S, et al. Exception from informed consent for emergency research: Consulting the trauma community. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:157–65. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318278908a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein L, Moore J, Biros M. A 20-year review: The use of exception from informed consent and waiver of informed consent in emergency research. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25:1169–77. doi: 10.1111/acem.13438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vorholt V, Dickert NW. Uninformed refusals: Objections to enrolment in clinical trials conducted under an exception from informed consent for emergency research. J Med Ethics. 2019;45:18–21. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2017-104736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pew Research Center. Demographics of Social Media Users and Adoption in the United States: Social Media Facts Sheet. 2019. June 12, [Last accessed on 2020 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/

- 9.Harvin JA, Podbielski JM, Vincent LE, Liang MK, Kao LS, Wade CE, et al. Impact of social media on community consultation in exception from informed consent clinical trials. J Surg Res. 2019;234:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stephens SW, Williams C, Gray R, Kerby JD, Wang HE, Bosarge PL. Using social media for community consultation and public disclosure in exception from informed consent trials. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80:1005–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson JN, Zive D, Griffiths D, Brown KN, Schmicker RH, Herren H, et al. Variations in the application of exception from informed consent in a multicenter clinical trial. Resuscitation. 2019;135:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eubank L, Lee KS, Seder DB, Strout T, Darrow M, MacDonald C, et al. Approaches to community consultation in exception from informed consent: Analysis of scope, efficiency, and cost at two centers. Resuscitation. 2018;130:81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matchett G, Ryan TJ, Sunna MC, Lee SC, Pepe PE. EvK Clinical Trial Group. Measuring the cost and effect of current community consultation and public disclosure techniques in emergency care research. Resuscitation. 2018;128:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silbergleit R, Biros MH, Harney D, Dickert N, Baren J. NETT Investigators. Implementation of the exception from informed consent regulations in a large multicenter emergency clinical trials network: The RAMPART experience. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:448–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Office of Good Clinical Practice, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, and Center for Devices and Radiological Health. ”Guidance for Institutional Review Boards, Clinical Investigators, and Sponsors Exception from Informed Consent Requirements for Emergency Research”. 2013 FDA-2006-D-0464. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halperin H, Paradis N, Mosesso V, Jr, Nichol G, Sayre M, Ornato JP, et al. Recommendations for implementation of community consultation and public disclosure under the food and drug administration's “exception from informed consent requirements for emergency research. Circulation. 2007;116:1855–63. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.186661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose DZ, Kasner SE. Informed consent: The rate-limiting step in acute stroke trials. Front Neurol. 2011;2:65. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2011.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.