Abstract

How is the dynamics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in 2020 with an health policy of full lockdowns and in 2021 with a vast campaign of vaccinations? The present study confronts this question here by developing a comparative analysis of the effects of COVID-19 pandemic between April–September 2020 (based upon strong control measures) and April–September 2021 (focused on health policy of vaccinations) in Italy, which was one of the first European countries to experience in 2020 high numbers of COVID-19 related infected individuals and deaths and in 2021 Italy has a high share of people fully vaccinated against COVID-19 (>89% of population aged over 12 years in January 2022). Results suggest that over the period under study, the arithmetic mean of confirmed cases, hospitalizations of people and admissions to Intensive Care Units (ICUs) in 2020 and 2021 is significantly equal (p-value<0.01), except fatality rate. Results suggest in December 2021 lower hospitalizations, admissions to ICUs, and fatality rate of COVID-19 than December 2020, though confirmed cases and mortality rates are in 2021 higher than 2020, and likely converging trends in the first quarter of 2022. These findings reveal that COVID-19 pandemic is driven by seasonality and environmental factors that reduce the negative effects in summer period, regardless control measures and/or vaccination campaigns. These findings here can be of benefit to design health policy responses of crisis management considering the growth of COVID-19 pandemic in winter months having reduced temperatures and low solar radiations ( COVID-19 has a behaviour of influenza-like illness). Hence, findings here suggest that strategies of prevention and control of infectious diseases similar to COVID-19 should be set up in summer months and fully implemented during low-solar-irradiation periods (autumn and winter period).

Keywords: COVID-19 transmission, Coronavirus, Influenza-like illness, Vaccinations, Seasonality, Climate factors, Environmental factors, Health planning, Crisis management

1. Introduction and goal of this investigation

We are still in the throes of the pandemic of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and its variants, an infectious illness generated by mutant viral agent of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that is generating health and social issues in manifold countries (Anand et al., 2021; Bontempi and Coccia, 2021; Bontempi et al., 2021; Coccia, 2020c; Johns Hopkins Center for System Science and Engineering, 2021). COVID-19 transmission has been investigated considering the relation with weather conditions, air pollution factors and social activities within and between countries (Bontempi et al., 2021; Coccia, 2020c, 2020a, 2021). Zhang et al. (2022) apply two different approaches to analyze the impact of social activity and climate factors on daily COVID-19 cases in the USA. The first approach is the correlation analysis to test the relationship between COVID-19 cases and weather variables or a social activity factor (i.e., social distance index); the second technique is a machine learning algorithm (random forest regression model) to investigate the feasibility of estimating the number of county-level daily confirmed COVID-19 cases by using different factors (e.g., population, population density, social distance index, temperature, humidity, solar radiation, precipitation, and wind speed). Nichols et al. (2021) analyze seasonal coronaviruses from 2012 to 2019 and compare their temporal dynamics to daily average weather parameters showing how coronavirus infections had a seasonal distribution like influenza. Zoran et al. (2021) apply descriptive statistics and regression models on geospatial daily time series to compare incidence and mortality cases of COVID-19 waves in Madrid (Spain) under different air quality and climate conditions. Results suggest for each of the four COVID-19 waves, anomalous anticyclonic synoptic meteorological patterns in the mid-troposphere and favorable stability conditions for COVID-19 disease fast spreading. Nicastro et al. (2021) also analyze the spatial aspects of SARS-CoV-2 in response to UV light and solar irradiation measurements on Earth. The “Solar-Pump” diffusive model of epidemics shows that UV-B/A photons have a powerful virucidal effect on the single-stranded RNA virus of the COVID-19 and that the solar radiation that reaches temperate regions of the Earth at noon during summers, it is a sufficient condition to inactivate 63% of virions in open-space concentrations in less than 2 minutes. Hoogeveen and Hoogeveen (2021) calculated the average annual time-series for influenza-like illnesses based on incidence data from 2016 to 2019 in the Netherlands and compared these results with two time-series of COVID-19 during 2020–2021 period for the same country. Results of the time-series for COVID-19 and influenza-like illnesses were highly significantly correlated. Instead, Baker et al. (2021) use an epidemiological model to assess the sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 to climate conditions. The sensitivity depends both on the susceptibility of population and the efficacy of non-pharmaceutical interventions in reducing transmission. Hence, more stringent non-pharmaceutical interventions may be required to minimize outbreak risk during the winter months in a pre-vaccination period. In the presence of COVID-19 pandemic crisis, just mentioned, R&D investment of nations and large corporations in pharmaceutical sector have supported the development of new drugs, such as different types of medicinal products (vaccines) based on viral vector, protein subunit and nucleic acid, etc., to constrain, temporarily, the spread of COVID-19 at national and international level (cf., Abbasi, 2020; Coccia, 2019, 2021a, 2022a, 2022b; Cylus et al., 2021; GAVI, 2021; Heaton, 2020; Jalkanen et al., 2021; Jeyanathan et al., 2020; MAYO Clinic, 2021). Vector vaccines have the characteristic that genetic material from the COVID-19 virus is placed in a modified version of a different virus (called, viral vector). When the viral vector gets into human cells, it delivers genetic material from the COVID-19 virus directed to instruct the cells to make copies of the Spike (S) protein (the main protein used as a target in COVID-19 vaccines). After that, human cells display the S proteins on their surfaces and immune system responds by creating antibodies and defensive white blood cells to fight the novel coronavirus (viral vector vaccines for COVID-19 are by Janssen/Johnson & Johnson and University of Oxford/AstraZeneca). Protein subunit vaccine includes only the parts of a virus that best stimulate the immune system. This type of COVID-19 vaccine has harmless S proteins. The immune system recognizes S proteins and creates antibodies and defensive white blood cells to fight the viral agent (e.g., the vaccine developed by Novavax, an American biotechnology company; cf., GAVI, 2021; readings Coccia, 2005, Coccia, 2017a, Coccia and Rolfo, 2008). Instead, the messenger RiboNucleic Acid (mRNA) vaccines use genetically engineered mRNA to give to cells instructions on how to make the S protein found on the surface of the SARS-CoV-2, creating antibodies to fight this novel coronavirus (Mayo Clinic, 2021). The process of development of mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 is much faster than other vaccines to be redesigned and mass-produced (Cylus et al., 2021; Heaton, 2020; Jeyanathan et al., 2020). The first path-breaking mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 are due to premier biopharmaceutical companies, Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna (cf., Coccia, 2021a, 2022a, 2022b; Estadilla et al., 2021; Love et al., 2021; Miles et al., 2021; Shahzamani et al., 2021; Yang and Shaman, 2021). A fundamental question in COVID-19 pandemic crisis is to analyze the dynamics of COVID-19 and compare the societal impact over time in the presence of non-pharmaceutical (lockdowns) and/or pharmaceutical measures (given by vaccines) in a same society and period. Manifold studies show the effects of COVID-19 vaccines and lockdowns on population and health system (Cai et al., 2021; Feng and LI, 2021; Rosenberg et al., 2021). However, inconsistencies and ambiguities in the literature and data about the overall effects over time of these control measures against the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) and its variants suggest the need for additional research. Unlike previous studies, the motivation of this study is to clarify, using statistical analyses, the dynamics and effects of COVID-19 in society comparing a period without vaccinations (and with strong control measures) to the same period of the following year having a vast vaccination campaign. In particular, the goal of this investigation is the assessment of the impact of COVID-19 in society (considering infected individuals, hospitalizations, ICUs, and fatality rates) by a comparative analysis of data between April–September 2020 and 2021 in Italy, which was one of first European countries to experience in 2020 high numbers of COVID-19 related infected individuals and deaths and in 2021 has a high share of people fully vaccinated against COVID-19. The results here can help scholars and policymakers to understand factors determining the behaviour of COVID-19 in environment and support appropriate and timing policy responses to cope with pandemic threat.

2. Theoretical background

Because of the rapid spread of COVID-19 worldwide, how the temporal dynamics and effects of COVID-19 pandemic change over time are important aspects to clarify driving factors for controlling, with appropriate health planning, the transmission and impact of the novel viral agent and its variants in environment and society (Aldila et al., 2021; Bontempi et al., 2021; Coccia, 2021b, 2021c, 2021d; Pawelec and McElhaney, 2021). In the presence of COVID-19 pandemic crisis, a pharmaceutical measure is vaccinations that have the potential to keep low basic reproduction number, to relax non-pharmaceutical interventions and to support the recovery, whenever possible, of socioeconomic systems (cf., Prieto Curiel and González Ramírez, 2021; Coccia, 2021b). Akamatsu et al. (2021) argue that governments have to implement an efficient campaign of vaccinations to reduce infections and mortality of COVID-19 in society and avoid the collapse of the healthcare system of countries (cf., Yoshikawa, 2021; Coccia, 2022a). Aldila et al. (2021) maintain that high levels of vaccination can eradicate COVID-19 in society by achieving, as far as possible, the herd immunity1 to protect vulnerable individuals (Anderson et al., 2020; de Vlas and Coffeng, 2021; Randolph and Barreiro, 2020; Redwan, 2021). Ioannidis (2021) suggests that if the vaccine efficacy decreases to 0.8, the benefit gets eroded easily with modest risk compensation. Tran et al. (2021) argue, in a case study of the states of Rhode Islands and Massachusetts, that with vaccination coverage higher than 28% and no major changes in non-pharmaceutical measures (e.g., social distancing, masking, gathering size, hygiene guidelines, etc.) and in virus transmissibility, a combination of vaccination and population immunity may lead to low or near-zero transmission levels by the second quarter of 2021.

However, other climatological, environmental, demographic, and geographical factors of the total environment can influence the spread of COVID-19 in society (Bashir et al., 2020; Coccia, 2021c, 2021d, 2021e, 2021f; Rosario et al., 2020; Sahin, 2020; Sarmadi et al., 2020). Zhong et al. (2018) argue that static meteorological conditions associated with high air pollution may explain the increase of bacterial communities in environment. Coccia (2020c) reveals that, among Italian provincial capitals, the number of infected people was higher in cities having high air pollution, cities located in hinterland zones (i.e., away from the coast), cities having a low wind speed (atmospheric stability) and cities with a lower temperature (cf., Coccia, 2020a, 2021; 2021c). Rosario et al. (2020) also reveal that high wind speed improves the circulation of air and increases the exposure of the novel coronavirus to solar radiation effects, a factor having a negative correlation with the environmental diffusion of COVID-19 (cf., Coccia, 2020c, 2021; 2021c, 2021f). Abraham et al. (2021) suggest the vital role of climatic factors and seasonality in all types of epidemics and pandemics, included the COVID-19. Zoran et al. (2021), analyzing COVID-19 waves in Madrid (Spain), maintain that air temperature, planetary boundary layer height, and ground level ozone have a significant negative relationship with daily new confirmed cases and deaths of COVID-19. Zoran et al. (2022) also show that from January 2020 to July 2021 the favorable stability conditions of atmosphere in Madrid (Spain) have supported COVID-19 disease fast spreading (cf., Coccia, 2021c). In general, this airborne disease is affected by seasonal changes with a significant negative correlation between air temperature, surface solar irradiance and daily new COVID-19 cases and deaths, showing a seasonality with climate factors. Danon et al. (2021) show that seasonal changes in transmission rate of COVID-19 can affect the timing and size of the epidemic potential; in particular, seasonal changes of COVID-19 shift the timing of the peak into winter period, with important implications for healthcare capacity planning (cf., Coccia, 2021f). Zhang et al. (2022) show that the estimation of COVID-19 cases is more accurate with data including weather variables. In particular, temperature and humidity are more vital factors than solar radiation and wind speed. Nichols et al. (2021) argue that seasonal coronavirus infections are due to immunological, weather, social and travel factors. Empirical evidence on different coronaviruses reveals that low temperature and low sunlight, such as in the UK and countries having a similar climate during winter period, can increase infections of airborne disease. Nicastro et al. (2021) maintain that the seasonality by the SARS-CoV-2 mortality is associated with different intensity of UV-B/A solar radiation hitting different Earth's locations at different times of the year. Hence, planning strategies of prevention of the epidemics should be fully implemented during low-solar-irradiation periods (Coccia, 2022a). The study by Hoogeveen and Hoogeveen (2021) confirms that the same factors that are driving the seasonality of influenza-like illnesses (e.g., low solar radiation, low temperature, high relative humidity, and subsequently seasonal allergens and allergies), they are also causing COVID-19 seasonality (cf., Erren et al., 2021; Baker et al., 2021).

In this context, a fundamental problem in COVID-19 pandemic crisis is to examine the evolution of COVID-19 into the same spatial area and period in 2020 and 2021 to explain variations or similarities of the effects in society. This study confronts the problem here by developing a comparative analysis between April–September 2020 and April–September 2021 in Italy, which was the first European country to experience a rapid increase in confirmed cases and deaths of COVID-19 in 2020 and in 2021 is one of the world-wide countries with a widespread plan of vaccination. The study here can clarify the behavior and effects of COVID-19 pandemic in environment and society in the presence of non-pharmaceutical or pharmaceutical measures of control. Lessons learned from this study could be of benefit to countries to design effective strategies of healthcare capacity planning to cope with and/or to prevent future waves of COVID-19 and/or epidemics/pandemics of similar infectious diseases. This study is part of a large body of research directed to explain drivers and effects of the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 pandemic to support effective policy responses of crisis management (Coccia, 2021b, 2022b, 2021g).

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Research questions

How is the temporal dynamics and effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in summer season of 2020 (without vaccines) and 2021 (with vaccinations)?

Does the behavior of COVID-19 change between summer period of 2020 (without vaccines) and 2021 (with vaccinations)?

The goal of this study is a comparative analysis of the temporal dynamics and effects of COVID-19 pandemic between 2020 and 2021 in Italy in the presence of different control measures in society.

3.2. Research setting

The research setting here is a case study of Italy, the first European country to experience a rapid increase of COVID-19 related infected individuals and deaths in 2020 (Coccia, 2020c). Moreover, Italy on 27th December 2021 is one of the world-wide countries with a widespread plan of vaccination having a share of people fully and only partly vaccinated against COVID-19 equal to about 90% (Lab24, 2021; Mathieu et al., 2021; Our World in Data, 2021).

In 2020, Italy applied non-pharmaceutical measures of control and strong containment policies, such as full lockdown (Coccia, 2021b). On March 12, 2021, Italy adopted the national strategic plan for the prevention of COVID-19 based on the execution of the vaccination campaign. Since scientific studies reveal that age and the presence of pathologies are associated with mortality from COVID-19 (cf., Seligman et al., 2021), these people have a priority order to be vaccinated in the Italian campaign, such as: highly frail people, people aged between 70 and 79 years, for whom the death rate associated with COVID-19 in those who are infected is about 10%; people between 60 and 69 years of age, for whom the death rate associated with COVID-19 in those who become infected is 3%; people under the age of 60 years with co-morbidities. In addition, the following categories have also been identified as priorities: school and university staff, teachers and non-teachers, armed forces, police and public rescue, etc. Initially, the vaccines administered in Italy are by the University of Oxford/AstraZeneca, Janssen/Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna. Because of supply issues, the vaccination campaign was continued mainly with mRNA vaccines (Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna); on 16 December 2021, it is also started the vaccination of children with pediatric Pfizer and in January-February 2022 it will be also available Novavax vaccine.

3.3. Period, sample and source

Data from 1st April to 23rd September 2020 are compared to the same period over 2021 in Italy, using daily data based on N = 176 days in 2020 and N = 176 days in 2021 for a total of N = 352 cases for different variables under study (described later). Source of epidemiological data under study is The Ministry of Health in Italy (Ministero della Salute, 2020).

3.4. Measures

The measures for statistical analyses are:

-

⁃

Number of daily COVID-19 infected individuals is measured with confirmed cases of COVID-19 per day.

-

⁃

Number of daily COVID-19 swab tests verifies the positivity to the novel coronavirus (confirmed case) by analyzing specimen of people (LabCorp, 2020).

-

⁃

Daily hospitalized people are total hospitalized patients with different COVID-19 symptoms and patients in Intensive Care Units.

-

⁃

Daily admissions to Intensive Care Units (ICUs) are the number of patients in ICUs for COVID-19.

-

⁃

Number of daily COVID-19 deaths is measured with total deaths per day.

-

⁃

Daily fatality rate = ratio of deaths at (t) divided by confirmed cases at (t-14 days). The time lag of about 14 days from initial symptoms to deaths is based on empirical evidence of some studies (Zhang et al., 2020).

3.5. Data analysis procedure

Firstly, the study calculates the daily contagiousness coefficient of COVID-19 in the same period under study of 2020 and 2021, given by:

This coefficient is used to normalize hospitalizations and admissions to ICUs. Moreover, to eliminate the weekly seasonal variation from original time series y t, it is applied the method of moving averages (MM) considering the sub-period of length r = 7 days (a week), using the following formula of MM7:

New time series adjusted with averaging process is given by that eliminates period to period weakly fluctuations and produces a much smoother series than original observations.

Data of daily hospitalizations of people and admissions to ICUs are normalized as follows:

The time lag of about 5 days to normalize these variables is based on an average period from diagnosis (initial symptoms and positivity to swab test) to the hospitalizations and recovery in ICUs of patients having COVID-19 complications (shortness of breath, loss of speech or mobility, confusion, chest pain, etc.) as explained by specific studies (Faes et al., 2020).

The sample of N = 352 cases is divided in two sub-samples having similar temporal, healthcare and societal conditions for a comparative analysis:

-

❑

group 1: data from 1st April to 23rd September 2020, N = 176

-

❑

group 2: data from 1st April to 23rd September 2021, N = 176

Secondly, data are analyzed with descriptive statistics given by arithmetic mean (M) and Std. Error of mean (SEM) for a comparative analysis between two groups just mentioned (Coccia, 2018, Coccia and Benati, 2018).

Thirdly, follow-up investigation is the Independent Samples t-Test that compares the means of two independent groups to determine whether there is statistical evidence that the associated population means are significantly different. The assumption of homogeneity of variance in the Independent Samples t-Test -- i.e., both groups have the same variance -- is verified with Levene's Test based on following statistical hypotheses:

H0: σ1 2 - σ2 2 = 0 (population variances of group 1 and 2 are equal).

H1: σ1 2 - σ2 2 ≠ 0 (population variances of group 1 and 2 are not equal).

The rejection of the null hypothesis in Levene's Test suggests that variances of the two groups are not equal: i.e., the assumption of homogeneity of variances is violated. If Levene's test indicates that variances are equal between the two groups (i.e., p-value large), equal variances are assumed. If Levene's test indicates that the variances are not equal between the two groups (i.e., p-value small), the assumption is that equal variances are not assumed.

After that, null hypothesis (H′ 0) and alternative hypothesis (H′ 1) of the Independent Samples t-Test are:

H′0: μ1 = μ2, the two-population means are equal in 2020 and 2021.

H′1: μ1 ≠ μ2, the two-population means are not equal in 2020 and 2021.

Finally, trends of variables under study are visualized and analyzed by comparing the data of COVID-10 pandemic in Italy between 2020 (with non-pharmaceutical control measures) and 2021 (with vaccinations). Statistical analysis is based on a simple regression (linear model) in which response variables measure the impact of the COVID-19 in society. Assumptions of the model of simple regression are:

-

•

Linearity – the relationships between the predictors and the outcome variable is linear.

-

•

Homogeneity of variance (homoscedasticity) – the error variance is constant.

-

•

Normality of distributions is necessary for the b-coefficient tests, and estimation of the coefficients requires that the errors be identically and independently distributed.

-

•

Independence – the errors associated with one observation are not correlated with the errors of any other observation.

Model specification is given by using the time series y* t in 2020 and 2021 for a comparative analysis of temporal dynamics over time:

| (1) |

y*t = measure of the impact of COVID-19 pandemic in society using MM7 of time series (Confirmed cases/swab tests, Hospitalizations and ICUs normalized)

t = time given by 2020 and 2021 period, as explained before

u = error term

Response variables of the indicators of COVID-19 in society depend on time considering two periods:

-

❑

2020, from 1st April to 23rd September 2020 when Italy applied non-pharmaceutical measures of containment based on national lockdown and quarantine.

-

❑

2021, from 1st April to 23rd September 2021, when Italy adopted mainly pharmaceutical measures for the prevention of COVID-19 based on a vast vaccination campaign.

The COVID-19 pandemic is also analyzed in December 2021 using different datasets for assessing the effects in a central month of winter and checking previous results to extend knowledge in these topics. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method is applied for estimating the unknown parameters of linear model [1]. Statistical analyses are performed with the Statistics Software SPSS® version 26.

4. Results

Table 1 shows that confirmed cases in 2020 is about 2.1%, whereas in 2021 is 2.5%. Number of hospitalizations and ICUs in 2020 has a slightly higher level, whereas fatality rate in 2021 is lower than 2021, likely because of a higher numbers of swab tests in 2021 that have detected more confirmed cases that increase the denominator of the ratio and consequently it reduces fatality rate.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

| Description of variables | April–September 2020 |

April–September 2021 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | Std. Error of Mean | M | Std. Error of Mean | |

| Confirmed cases normalized | 0.021 | 0.002 | 0.0254 | 0.0012 |

| Hospitalizations normalized | 556.720 | 94.706 | 406.0100 | 46.8410 |

| ICUs normalized | 58.850 | 11.076 | 48.0400 | 5.4400 |

| Fatality rates | 0.073 | 0.003 | 0.0146 | 0.0004 |

Note: M = arithmetic mean, N = 176 days in 2020 and 176 in 2021.

Table 2 shows the Independent Samples t-Test, as follow-up inspection, to assess the significance of the difference of arithmetic mean between groups of variables in 2020 and 2021. The p-value of Levene's test is significant, and we have to reject the null hypothesis of Levene's test and conclude that the variance in the groups under study is significantly different (i.e., equal variances are not assumed). Table 2 also shows t-test for equality of means. Since p-value≥0.5 is higher than fixed significance level α = 0.01, we can accept the null hypothesis, and conclude that the mean of confirmed cases, hospitalizations of people, and admissions to ICUs in 2020 and 2021 is significantly equal: there is not a significant difference in arithmetic mean between April–September 2020 and 2021. Instead, for fatality rates, since p -value<0.001 is less than chosen significance level α = 0.01, we can reject the null hypothesis, and conclude that the mean in 2021 and 2021 is significantly different, likely for reasons mentioned for Table 1.

Table 2.

Independent samples test.

| Levene's test for equality of variances |

t-test for equality of Means |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | T | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | ||

| Confirmed cases 2020 vs. 2021 |

|

11.722 | 0.001 | −1.631 | 350 | 0.104 | −0.004 | 0.002 |

|

−1.631 | 276.877 | 0.104 | −0.004 | 0.002 | |||

| Hospitalizations 2020 vs. 2021 |

|

18.541 | 0.001 | 1.426 | 350 | 0.155 | 150.716 | 105.657 |

|

1.426 | 255.784 | 0.155 | 150.716 | 105.657 | |||

| ICUs 2020 vs. 2021 |

|

12.436 | 0.001 | 0.876 | 350 | 0.382 | 10.813 | 12.340 |

|

0.876 | 254.772 | 0.382 | 10.813 | 12.340 | |||

| Fatality rates 2020 vs. 2021 |

|

446.728 | 0.001 | 17.812 | 350 | 0.001 | 0.058 | 0.003 |

|

17.812 | 180.875 | 0.001 | 0.058 | 0.003 | |||

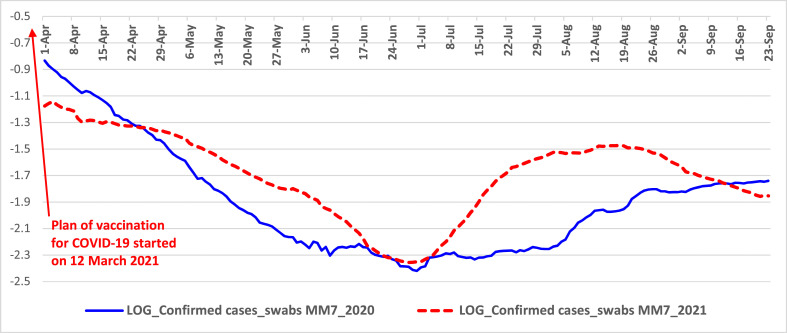

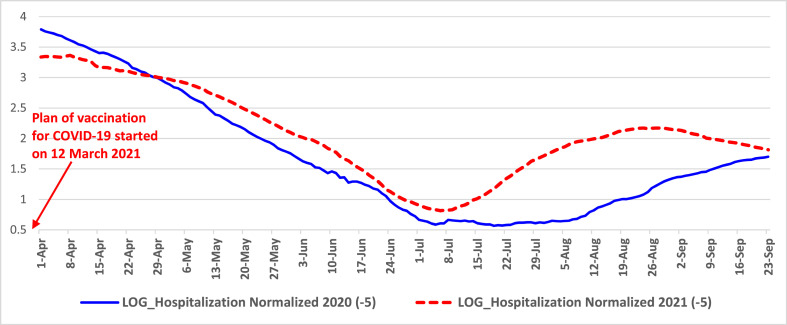

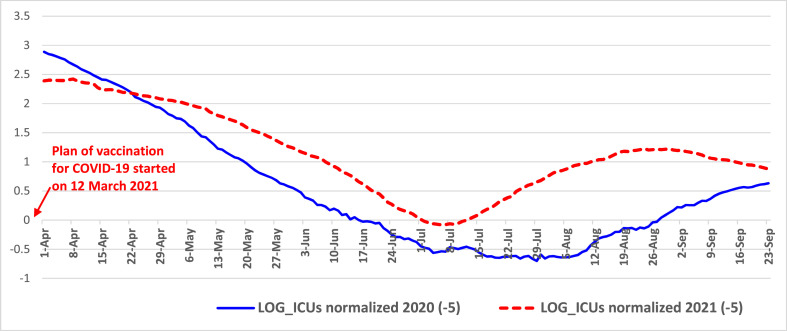

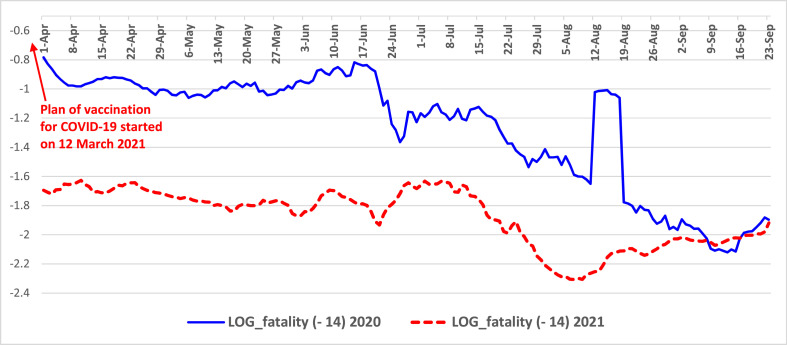

Table 3 and Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4 confirm, ictu oculi, previous results. In particular, simple regression analysis in Table 3 shows, in average, a higher reduction of variables in 2020 than 2021, measured with coefficients of regression (p-value≤ 0.001). The coefficient of determination R2 indicates that the variation from 24% to 70% in response variables of the COVID-19 can be attributed (linearly) to temporal variable. F-test is significant with p-value <0.001.

Table 3.

Estimated relationships based on model of simple regression.

| Confirmed cases |

Hospitalizations |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2021 | 2020 | 2021 | |

| Constant α | 0.050*** | 0.066*** | 1944.93*** | 2768.46*** |

| Coefficient β | −0.00032*** | −0.00015*** | −15.69*** | −8.93*** |

| Stand. Coeff. β | −0.58 | −0.49 | −0.64 | −0.73 |

| R2 | 0.334 | 0.143 | 0.41 | 0.54 |

|

F-test |

87.25*** |

55.79*** |

118.26*** |

201.25*** |

| ICUs |

Fatality rates |

|||

| 2020 |

2021 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

| Constant α | 210.48*** | 327.21*** | 0.14*** | 0.04*** |

| Coefficient β | −1.71*** | −1.06*** | −0.001*** | −0.00009*** |

| Stand. Coeff. β | −0.594 | −0.745 | −.84 | −.78 |

| R2 | 0.35 | 0.55 | 0.71 | 0.60 |

| F-test | 94.90*** | 217.30*** | 416.01*** | 264.00*** |

Notes: Explanatory variable: Case sequence (time).

Response variables: Hospitalizations normalized, Confirmed cases normalized, ICUs normalized, Fatality rates.

Significance: ***p-value<0.001,*p-value<0.5.

Fig. 1.

Trends of normalized confirmed cases from April to September 2020 and 2021 in Italy. Note: log scale on y-axis for better visualization of MM7 values.

Fig. 2.

Trends of normalized hospitalized people from April to September 2020 and 2021 in Italy Note: log scale on y-axis for better visualization of MM7 values.

Fig. 3.

Trends of normalized ICUs from April to September 2020 and 2021 in Italy Note: log scale on y-axis for better visualization of MM7 values.

Fig. 4.

Trends of fatality rates from April to September 2020 and 2021 in Italy Note: log scale on y-axis for better visualization of MM7 values.

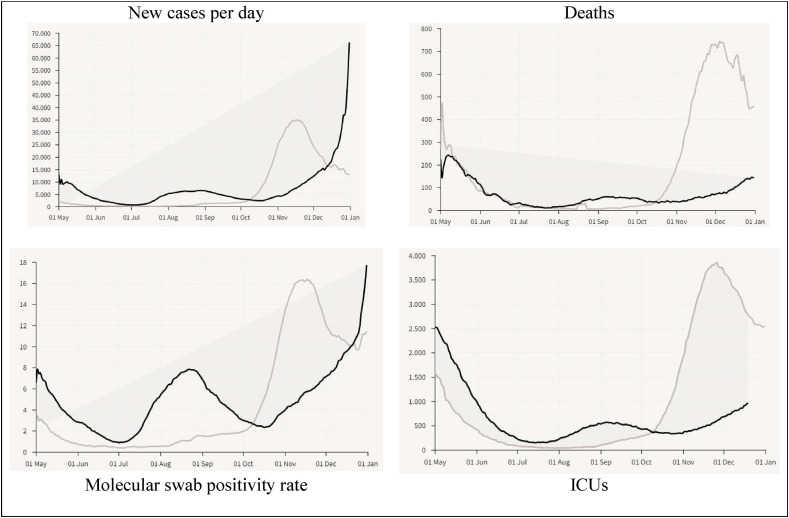

Fig. 5 shows a control analysis considering winter months from October to December based on data and elaboration by Lab24-il Sole 24 Ore (2022). Firstly, we have to consider that:

-

⁃

In 2020, during the period of first wave of COVID-19 pandemic, Italy applied non-pharmaceutical measures of containment based on national lockdown and quarantine, which started on 8th March 2020 and ended on 18th May 2020 directed to constrain transmission dynamics of the novel coronavirus (Coccia, 2021b, 2021d).

-

⁃

Instead, in 2021 during the second and third wave of COVID-19, on March 12, 2021, Italy applied mainly pharmaceutical measures for the prevention of COVID-19 based on a vast vaccination campaign associated with a vaccine certificate (cf., Coccia, 2022a, 2022b).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of COVID-19 dynamics in 2020 vs. 2021 in Italy, May–December 2021, January 2022. Note: See Appendix for a focus on December 2020 vs. 2021.

Secondly, Fig. 5 seems to suggest, from October to December 2021, that new daily cases of COVID-19 are increasing in 2021 compared to 2020, maybe because of new variants of COVID-19 for which vaccines seem to have low effectiveness, whereas deaths and ICUs in 2021 are lower than 2020 (until December), though trend of 2021 is increasing over time for a likely convergence towards similar effects of the line of 2020 in the first quarter of 2022.

Overall, then, conclusion of statistical analyses here suggests that the behavior of pandemic waves in 2020 and 2021 is rather similar, regardless the plan of vaccination and/or control measures (e.g., full lockdowns) implemented by Italy in the period under study. Results seem also to reveal that the negative effects of COVID-19 in Italy are higher in 2021 than 2020 for some variables. This finding can be explained with highly contagious nature of new variants (e.g., Delta and Omicron) of the novel coronavirus and limited scope of vaccines (originated to cope with the original alpha strain), because mutant SARS-CoV-2 is also infecting people who are full vaccinated. Hence, these new variants should open a scientific and political debate about the appropriateness of vaccinations with current anti-COVID/19 drugs that protect people against this infection mainly in a short run and on role of environmental factors that guide transmission dynamics of this novel infection disease, factors that are discussed in the following section.

5. Discussions and explanation of findings

The results of this study show a comparative analysis of the effects of COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021 in the same socioeconomic system, given by Italy, and same period (April–September). Results reveal a similar behavior of COVID-19, regardless of lockdowns and/or vaccinations. These results can be explained with theories that focus on critical role of climatic factors and seasonality in all types of epidemics and pandemics based on airborne diseases, such as COVID-19 (Abraham et al., 2021; Dbouk and Drikakis, 2020; Ianevski et al., 2019; Hoogeveen and Hoogeveen, 2021; Nichols et al., 2021). In general, meteorological factors (e.g., temperature and humidity) play a well-established role in the seasonal transmission of respiratory viruses and influenza-like illnesses (Chan et al., 2011; Hoogeveen and Hoogeveen, 2021; Roussel et al., 2016). Manifold studies suggest that the spread of COVID-19 can be influenced by climate and variation of environmental factors that induce a seasonality (Christophi et al., 2021; Maharaj et al., 2021). In fact, summer seasonality can reduce the spread of the novel coronavirus over time and space and constrain the negative effects in society (Takagi et al., 2020; Şahin, 2020). In particular, while a high absolute humidity can support viral transmission (Islam et al., 2021), high solar radiation and high wind speed can mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in environment (Coccia, 2021, 2021c; Rosario et al., 2020). Scholars suggest that the effects of climate on the influenza epidemic lead to seasonal fluctuations associated with latitude in the North and South Hemisphere of the globe (Ianevski et al., 2019; Shaman and Galanti, 2020). Especially, scholars analyze the sensitivity of COVID-19 to meteorological factors for explaining how changes in the weather and seasonality may constrain COVID-19 transmission (Audi et al., 2020; Kerr et al., 2021; Moriyama et al., 2020). The study by Liu et al. (2021, p.1ff) shows that the cold season in the Southern Hemisphere countries caused a 59.71 ± 8.72% increase of total infections, whereas the warm season in the Northern Hemisphere countries contributed to a 46.38 ± 29.10% reduction. These results propose that COVID-19 seasonality is more pronounced at higher latitudes, in the presence of larger seasonal amplitudes in atmosphere. Other studies have focused on effects of high temperature and/or low humidity that might slow down transmission of the novel coronavirus (Karapiperis et al., 2021; Rosario et al., 2020; Runkle et al., 2020). Byun et al. (2021) show that manifold studies suggest an inverse relation between temperature and humidity, and global transmission of the viral agent of SARS-CoV-2. As matter of fact, COVID-19 tends to be temperature-sensitive and, consequently, driven by a seasonal viral agent (cf., Engelbrecht and Scholes, 2021). In this context, Karapiperis et al. (2021) demonstrated that UV radiation is strongly associated with incidence rates of COVID-19, regardless the initial conditions of the epidemic over space (cf., Kumar et al., 2021). Dbouk and Drikakis (2021), applying fluid dynamics simulations, show that weather seasonality can induce two outbreaks of the COVID-19 pandemic that are directly associated with temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed of geographical regions. In brief, many endemic human coronaviruses can be seasonally recurrent infectious diseases (Kronfeld-Schor et al., 2021). Although a vital relationship between weather seasonality, environmental factors, air pollution and airborne infectious diseases exists over time and space (Coccia, 2020c), Dbouk and Drikakis (2020) maintain that many epidemiologic models do not include climate factors to explain the transmission dynamics of airborne transmission opf viral agents with likely misleading results.

Hence, the empirical evidence here seems to suggest that the novel coronavirus pandemic has a full seasonal cycle, showing a reduced rate of diffusion with low humidity and high temperature (Karapiperis et al., 2021): i.e., the SARS-CoV2 transmissibility seems to naturally decrease in summer seasons, regardless of non-pharmaceutical and/or pharmaceutical interventions. The proposed explanation here of similar trends of the temporal dynamics of COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021 in Italy--based on seasonality and other environmental factors in the spread of the novel coronavirus--is a critical result to design and implement appropriate public health policies, timely vaccination campaigns and other non-pharmaceutical interventions to cope with recurring waves of COVID-19 pandemic in society.

6. Concluding observations and limitations

COVID-19 and other future pandemics can be due to human activities that are changing the globe, such as high industrialization associated with air and environmental pollution (and inter-related climate and ecological change), bad land use, high urbanization, globalization of trade, laboratory testing of hazardous pathogens, people who have continuos contacts with wildlife, and in general the change on how human society interacts with natural ecosystems (Abraham et al., 2021; Coccia, 2005, 2015, 2017, 2020b; Coccia and Bellitto, 2018; cf. also readings Coccia, 2017, Coccia, 2021). This study reveals,−with a comparative analysis between April–September 2020 and April–September 2021 in Italy−, that average confirmed cases, hospitalizations of people, and admissions to ICUs are significantly equal, corroborating the seasonal behavior in the total environment of the COVID-19, which decreases in summer season regardless of vaccinations and/or other non-pharmaceutical measures of control over time and space. This finding has a critical aspect to clarify transmission dynamics of COVID-19 and support appropriate interventions of health policy to cope with outbreaks of current and future (airborne) infectious diseases (Coccia, 2021a). In fact, these results can support the implementation of best practices of public health considering seasonal behavior of the COVID-19 in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres that unfold mainly over winter-fall period (cf., Bontempi et al., 2021; Coccia, 2022b; Gozzi et al., 2021; Yoshikawa, 2021). Danon et al. (2021) show that seasonal changes in transmission rate can affect the timing and size of COVID-19 pandemic, shifting the peak into winter, with important implications for planning the healthcare capacity and vaccination campaign to cope with this airborne infectious disease. As a matter of fact, Smit et al. (2020) argue that climatic factors would reduce the viral transmission rate in boreal summer and the COVID-19 peak would coincide with the peak of the influenza season, increasing the burden on health systems (cf., Kronfeld-Schor et al., 2021). Nichols et al. (2021) maintain that high level of infections is associated with reduced temperatures and low solar radiations, such that measures of control for COVID-19 have to be introduced mainly in autumn-winter months. Nicastro et al. (2021) also argue that the planning of strategies of confinement for epidemics should be set up during summer months and fully implemented during low-solar-irradiation months (autumnal and winter period). Hence, seasonality is one of the main drivers in transmission dynamics of COVID-19 and to curb the diffusion of the novel coronavirus, it is important to apply multidisciplinary approaches, not limited to medicine, to design and timely apply response policies of short and long run, supporting a scaled-up health care capacity in autumnal and winter seasons (Bontempi et al., 2021, Bontempi and Coccia, 2021, Coccia, 2020c, Coccia, 2020a, Bontempi, 2022).

Overall, then, this statistical analysis here suggests that the behaviour of COVID-19 seems to be associated with seasonality of the novel coronavirus that reduces the transmission in summer season and naturally constrains the effects of this airborne disease in society, regardless of pharmaceutical and/or other non-pharmaceutical measures of control applied previously over time and space (cf. readings Coccia, 2020a, Coccia, 2020b). These conclusions are, of course, tentative. Although this study has provided some interesting, albeit preliminary results, it has several limitations. First, COVID-19 is still progressing with new variants, and sources understudy may only capture certain aspects of the on-going dynamics of this pandemic, because the effects of this mutant coronavirus are continually changing in geo-economic regions. Second, structure of population and characteristics of patients (e.g., ethnicity, type of blood group, age, sex, and comorbidities) and new technology applied to face this pandemic may vary between regions affecting the impact of COVID-19 in society (Coccia, 2019a), and cf. also readings (Ardito et al., 2021, Coccia, 2018). Third, there are multiple confounding factors that could affect the spread of COVID-19 pandemic to be further investigated (e.g., institutional aspects, investments in healthcare sector, etc.; cf., Coccia, 2018a). Finally, the statistical analyses and estimated relationships in this study focus on data in a specific period and country having a Mediterranean climate (i.e., Italy) and must be extended to other countries to reinforce proposed results here. Thus, the generalization of results in this research should be done with caution. Despite these limitations, the results presented here clearly illustrate the seasonal behaviour of COVID-19 and the need for more detailed examinations of the relationship between dynamics of COVID-19, climate and environmental factors to better understand transmission dynamics of this novel coronavirus and airborne disease over time and space for applying appropriate policy responses of crisis management to cope with pandemic threat at country and global level (cf. reading Coccia, 2020).

To conclude, future research should consider new data when available, and when possible, it should examine new time series of different countries with models including manifold variables to provide a comprehensive explanation of the phenomena under study over time and space. Therefore, this study like many studies--analyzing the behaviour of pandemic diseases--strongly suggests an extension of the family of epidemiologic models that should also include parameters associated with climatological, environmental and socioeconomic factors to explain the complex aspects of this mutant SARS-CoV-2 in natural ecosystem and support appropriate policy responses (Batabyal, 2021; Bontempi and Coccia, 2021; Bontempi et al., 2021; Coccia, 2021e, 2021f).

Declaration of competing interest

The author declares that he has no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Herd immunity indicates that only a share of a population needs to be immune and consequently no longer susceptible (by overcoming natural infection or through vaccination) to a viral agent for epidemic control and to stop large outbreaks (Fontanet and Cauchemez, 2020; Rosen et al., 2021).

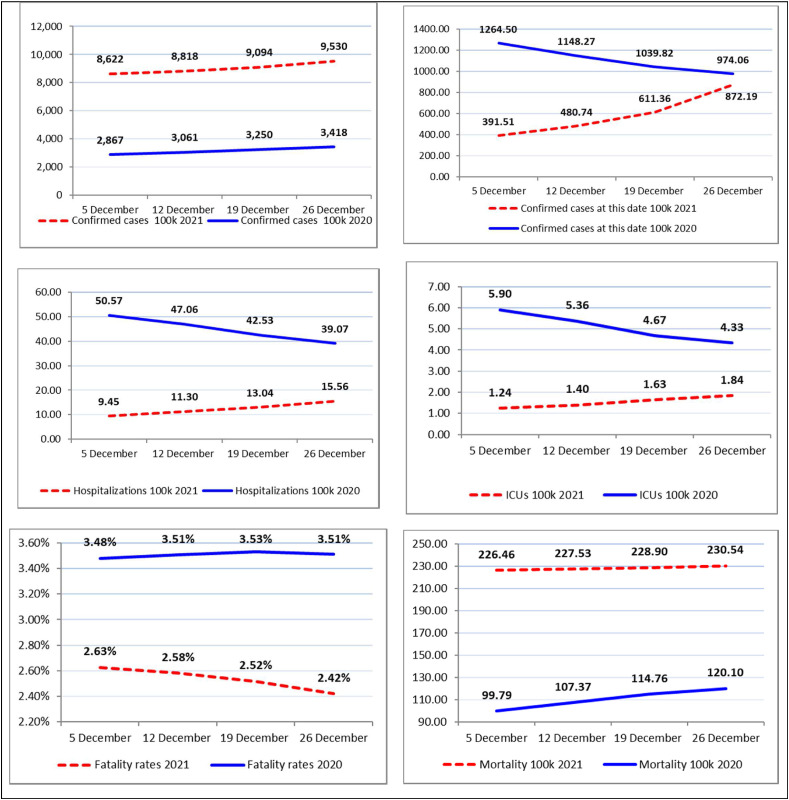

Appendix A. Comparison of indicators concerning COVID-19 between December 2020 and 2021 in Italy

Note: Figures are based on weekly arithmetic mean (per 100 000 inhabitants), except the first figure in the top-right that is based on total values of the day.

References

- Abbasi J. COVID-19 and mRNA vaccines-first large test for a new approach. JAMA. 2020;324(12):1125–1127. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.16866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham J., Turville C., Dowling K., Florentine S. Does climate play any role in covid-19 spreading?—an Australian perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021;18(17):9086. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akamatsu T., Nagae T., Osawa M., Satsukawa K., Sakai T., Mizutani D. Model-based analysis on social acceptability and feasibility of a focused protection strategy against the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81630-9. 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldila D., Samiadji B.M., Simorangkir G.M., Khosnaw S.H.A., Shahzad M. Impact of early detection and vaccination strategy in COVID-19 eradication program in Jakarta, Indonesia. BMC Res. Notes. 2021;14(1):132. doi: 10.1186/s13104-021-05540-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand U., Cabreros C., Mal J., Ballesteros F., Jr., Sillanpää M., Tripathi V., Bontempi E. Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: from transmission to control with an interdisciplinary vision. Environ. Res. 2021;197:111126. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R.M., Vegvari C., Truscott J., Collyer B.S. Challenges in creating herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection by mass vaccination. Lancet (London, England) 2020;396(10263):1614–1616. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32318-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardito L., Coccia Mario, Messeni Petruzzelli A. Technological exaptation and crisis management: Evidence from COVID-19 outbreaks. R&D Management. R&D Management. 2021;51(4):381–392. doi: 10.1111/radm.12455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Audi A., Alibrahim M., Kaddoura M., Hijazi G., Yassine H.M., Zaraket H. 2020. Seasonality of Respiratory Viral Infections: Will. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R.E., Yang W., Vecchi G.A., Metcalf C.J.E., Grenfell B.T. Assessing the influence of climate on wintertime SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):846. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-20991-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir M.F., Ma B., Bilal Komal B., Bashir M.A., Tan D., Bashir M. vol. 728. Science of the Total Environment; 2020. (Correlation between Climate Indicators and COVID-19 Pandemic in New York, USA). art. no. 138835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batabyal S. COVID-19: perturbation dynamics resulting chaos to stable with seasonality transmission. Chaos, Solit. Fractals. 2021;145:110772. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2021.110772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi E., Coccia M. International trade as critical parameter of COVID-19 spread that outclasses demographic, economic, environmental, and pollution factors. Environ. Res. 2021;201 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111514. Article number 111514, PII S0013-9351(21)00808-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi E., Coccia M., Vergalli S., Zanoletti A. Can commercial trade represent the main indicator of the COVID-19 diffusion due to human-to-human interactions? A comparative analysis between Italy, France, and Spain. Environ. Res. 2021;201 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111529. Article number 111529, PII S0013-9351(21)00823-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi E. A global assessment of COVID-19 diffusion based on a single indicator: some considerations about air pollution and COVID-19 spread. Environ. Res. 2022;204(Pt B):112098. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.112098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun W.S., Heo S.W., Jo G., Kim J.W., Kim S., Lee S., Park H.E., Baek J.H. Is coronavirus disease (COVID-19) seasonal? A critical analysis of empirical and epidemiological studies at global and local scales. Environ Res. 2021. 2021;196:110972. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.110972. May. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C., Peng Y., Shen E., et al. A comprehensive analysis of the efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines. Mol. Ther. 2021;29(9):2794–2805. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K.H., Peiris J.S.M., Lam S.Y., Poon L.L.M., Yuen K.Y., Seto W.H. The effects of temperature and relative humidity on the viability of the SARS coronavirus. 2011) Adv. Virol., 2011. 2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/734690. art. no. 734690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophi C.A., Sotos-Prieto M., Lan F.-Y., et al. Ambient temperature and subsequent COVID-19 mortality in the OECD countries and individual United States. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):8710. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87803-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. Countrymetrics: valutazione della performance economica e tecnologica dei paesi e posizionamento dell'Italia. Riv. Int. Sci. Soc. 2005;CXIII(3):377–412. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41624216 Stable URL: [Google Scholar]

- Coccia Mario. A taxonomy of public research bodies: a systemic approach. Prometheus. 2005;23(1):63–82. doi: 10.1080/0810902042000331322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. Spatial relation between geo-climate zones and technological outputs to explain the evolution of technology. Int. J. Transit. Innovat. Syst. 2015;4(1–2):5–21. doi: 10.1504/IJTIS.2015.074642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia Mario, Rolfo S. Strategic change of public research units in their scientific activity. Technovation. 2008;28(8):485–494. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2008.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. New directions in measurement of economic growth, development and under development. J. Econ. Polit. Econ. 2017;4(4):382–395. doi: 10.1453/jepe.v4i4.1533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia Mario. Varieties of capitalism’s theory of innovation and a conceptual integration with leadership-oriented executives: the relation between typologies of executive, technological and socioeconomic performances. Int. J. Public Sector Performance Management. 2017;3(2):148–168. doi: 10.1504/IJPSPM.2017.084672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. Disruptive firms and industrial change. Journal of Economic and Social Thought. 2017;4(4):437–450. doi: 10.1453/jest.v4i4.1511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. The origins of the economics of Innovation. Journal of Economic and Social Thought. 2018;5(1):9–28. doi: 10.1453/jest.v5i1.1574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. Effects of human progress driven by technological change on physical and mental health. STUDI DI SOCIOLOGIA. 2021;(2):113–132. doi: 10.26350/000309_000116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia Mario. An introduction to the methods of inquiry in social sciences. J. Adm. Soc. Sci. 2018;5(2):116–126. doi: 10.1453/jsas.v5i2.1651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia Mario. An introduction to the theories of institutional change. J. Econ. Lib. 2018;5(4):337–344. doi: 10.1453/jel.v5i4.1788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. Why do nations produce science advances and new technology? Technol. Soc. 2019;59(November):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.03.007. 101124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia Mario. A Theory of classification and evolution of technologies within a Generalized Darwinism. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2019;31(5):517–531. doi: 10.1080/09537325.2018.1523385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia Mario. In: Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. 1st. Farazmand A., editor. Springer Nature; 2020. Comparative Critical Decisions in Management; pp. 1–9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. The impact of lockdown on public health during the first wave of covid-19 pandemic: lessons learned for designing effective containment measures to cope with second wave. CocciaLab Working Paper – National Research Council of Italy. 2020;(56B):1–23. doi: 10.1101/2020.10.22.20217695. https://medrxiv.org/cgi/content/short/2020.10.22.20217695v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. How is the impact on public health of second wave of COVID-19 pandemic compared to the first wave? Case study of Italy. Working Paper CocciaLab, CNR -- National Research Council of Italy. 2020;(57/B):1–20. doi: 10.1101/2020.11.16.20232389. doi: 10.1101/2020.11.16.20232389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. How (Un)sustainable environments are related to the diffusion of COVID-19: the relation between coronavirus disease 2019, air pollution, wind resource and energy. Sustainability. 2020;12(22):9709. doi: 10.3390/su12229709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. How do environmental, demographic, and geographical factors influence the spread of COVID-19. J. Soc. Admin. Sci. 2020;7(3):169–209. doi: 10.1453/jsas.v7i3.2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. Factors determining the diffusion of COVID-19 and suggested strategy to prevent future accelerated viral infectivity similar to COVID. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:138474. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. The effects of atmospheric stability with low wind speed and of air pollution on the accelerated transmission dynamics of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2021;78(1):1–27. doi: 10.1080/00207233.2020.1802937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. vol. 1. MDPI; Basel, Switzerland: 2021. pp. 433–444. (Pandemic Prevention: Lessons from COVID-19. Encyclopedia 2021). Encyclopedia of COVID-19, open access journal. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. Science of The Total Environment; 2021. The Relation between Length of Lockdown, Numbers of Infected People and Deaths of Covid-19, and Economic Growth of Countries: Lessons Learned to Cope with Future Pandemics Similar to Covid-19; p. 145801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. How do low wind speeds and high levels of air pollution support the spread of COVID-19? Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2021;12(1):437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.apr.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. The impact of first and second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: comparative analysis to support control measures to cope with negative effects of future infectious diseases in society. Environ. Res. 2021;197 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111099. Article number 111099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. Effects of the spread of COVID-19 on public health of polluted cities: results of the first wave for explaining the dejà vu in the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic and epidemics of future vital agents. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2021;28(15):19147–19154. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-11662-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. High health expenditures and low exposure of population to air pollution as critical factors that can reduce fatality rate in COVID-19 pandemic crisis: a global analysis. Environ. Res. 2021;199:111339. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. Evolution and structure of research fields driven by crises and environmental threats: the COVID-19 research. Scientometrics. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11192-021-04172-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. Preparedness of countries to face covid-19 pandemic crisis: strategic positioning and underlying structural factors to support strategies of prevention of pandemic threats. Environ. Res. 2022;203:111678. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111678. ISSN 0013-9351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M. vol. 204. Environmental Research; 2022. (Optimal Levels of Vaccination to Reduce COVID-19 Infected Individuals and Deaths: A Global Analysis). Part C, March 2022, Article number 112314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia M., Bellitto M. Human progress and its socioeconomic effects in society. J. Econ. Soc. Thought. 2018;5(2):160–178. doi: 10.1453/jest.v5i2.1649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia Mario, Benati I. In: Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. 1st. Farazmand A., editor. Springer Nature; 2018. Comparative Models of Inquiry; pp. 1–7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cylus J., Pantel D., van Ginneken E. Who should be vaccinated first? Comparing vaccine prioritization strategies in Israel and European countries using the Covid-19 Health System Response Monitor. Isr. J. Health Pol. Res. 2021;10(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s13584-021-00453-1. https://doi.org/10.1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danon L., Brooks-Pollock E., Bailey M., Keeling M. A spatial model of COVID-19 transmission in England and Wales: early spread, peak timing and the impact of seasonality. Phil. Trans. Biol. Sci. 2021;376(1829):20200272. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2020.0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dbouk T., Drikakis D. Weather impact on airborne coronavirus survival. Phys. Fluids. 2020;32(9) doi: 10.1063/5.0024272. 093312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dbouk T., Drikakis D. Fluid dynamics and epidemiology: seasonality and transmission dynamics. Phys. Fluids. 2021;33(2) doi: 10.1063/5.0037640. 021901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vlas S.J., Coffeng L.E. Achieving herd immunity against COVID-19 at the country level by the exit strategy of a phased lift of control. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):4445. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83492-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministero della Salute . 2021. COVID-19 - Situazione in Italia.http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=5351&area=nuovoCoronavirus&menu=vuoto Accessed June 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht F.A., Scholes R.J. vol. 12. One health; Amsterdam, Netherlands: 2021. p. 100202. (Test for Covid-19 Seasonality and the Risk of Second Waves). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erren T.C., Lewis P., Morfeld P. Factoring in coronavirus disease 2019 seasonality: experiences from Germany. JID (J. Infect. Dis.) 2021;224(6):1096. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estadilla C.D.S., Uyheng J., de Lara-Tuprio E.P., et al. Impact of vaccine supplies and delays on optimal control of the COVID-19 pandemic: mapping interventions for the Philippines. Infect. Dis. Pover. 2021;10(1):107. doi: 10.1186/s40249-021-00886-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faes C., Abrams S., Van Beckhoven D., Meyfroidt G., Vlieghe E., Hens N., Belgian Collaborative Group on Covid-19 Hospital Surveillance Time between symptom onset, hospitalisation and recovery or death: statistical analysis of Belgian COVID-19 patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17:7560. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J., Li Q. How to ensure vaccine safety: an evaluation of China's vaccine regulation system. Vaccine. 2021;39(37):5285–5294. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanet A., Cauchemez S. COVID-19 herd immunity: where are we? Nature reviews. Immunology. 2020;20(10):583–584. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00451-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAVI . 2021. THE FOUR MAIN TYPES OF COVID-19 VACCINE.https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/there-are-four-types-covid-19-vaccines-heres-how-they-work accessed 6 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gozzi N., Bajardi P., Perra N. The importance of non-pharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 vaccine rollout. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2021;17(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton P.M. The covid-19 vaccine-development multiverse. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383(20):1986–1988. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2025111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogeveen M.J., Hoogeveen E.K. Comparable seasonal pattern for COVID-19 and flu-like illnesses. One Health. 2021;13:100277. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ianevski A., Zusinaite E., Shtaida N., Kallio-Kokko H., Valkonen M., Kantele A., Telling K., Lutsar I., Letjuka P., Metelitsa N., Oksenych V., Dumpis U., Vitkauskiene A., Stašaitis K., Öhrmalm C., Bondeson K., Bergqvist A., Cox R.J., Tenson T., Merits A., Kainov D.E. Low temperature and low UV indexes correlated with peaks of influenza virus activity in Northern Europe during 2010⁻2018. Viruses. 2019;11(3):207. doi: 10.3390/v11030207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis J.P.A. Benefit of COVID-19 vaccination accounting for potential risk compensation. npj Vaccines. 2021;6(1):99. doi: 10.1038/s41541-021-00362-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam N., Bukhari Q., Jameel Y., Shabnam S., Erzurumluoglu A.M., Siddique M.A., Massaro J.M., et al. 2021. COVID-19 and climatic factors: a global analysis. Environ. Res. 2021;193:110355. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalkanen P., Kolehmainen P., Häkkinen H.K., et al. COVID-19 mRNA vaccine induced antibody responses against three SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):3991. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24285-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyanathan M., Afkhami S., Smaill F., Miller M.S., Lichty B.D., Xing Z. Immunological considerations for COVID-19 vaccine strategies. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20(10):615–632. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00434-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins Center for System Science and Engineering . 2021. Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases.https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 accessed in 4 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Karapiperis C., Kouklis P., Papastratos S., et al. A strong seasonality pattern for covid-19 incidence rates modulated by UV radiation levels. Viruses. 2021;13(4):574. doi: 10.3390/v13040574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr G.H., Badr H.S., Gardner L.M., Perez-Saez J., Zaitchik B.F. One Health12; 2021. Associations between Meteorology and COVID-19 in Early Studies: Inconsistencies, Uncertainties, and Recommendations; p. 100225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronfeld-Schor N., Stevenson T.J., Nickbakhsh S., Schernhammer E.S., Dopico X.C., Dayan T., Martinez M., Helm B. Drivers of infectious disease seasonality: potential implications for COVID-19. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2021;36(1):35–54. doi: 10.1177/0748730420987322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M., Mazumder P., Mohapatra S., et al. A chronicle of SARS-CoV-2: seasonality, environmental fate, transport, inactivation, and antiviral drug resistance. J. Hazard Mater. 2021;405:124043. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lab24 . 2021. Vaccino, I Dati Per Paese | Il Sole 24 ORE.https://lab24.ilsole24ore.com/coronavirus/ (accessed 20th June 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Lab24-il Sole 24 Ore . 2022. Coronavirus in Italia, i dati e la mappa (ilsole24ore.com)https://lab24.ilsole24ore.com/coronavirus/ Accessed 3rd January 2022. [Google Scholar]

- LabCorp . 2020. Individuals/Patients, Getting COVID-19 Test Results-How to Get My COVID-19 Test Result.https://www.labcorp.com/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/individuals/test-results accessed in October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Huang J., Li C., Zhao Y., Wang D., Huang Z., Yang K. The role of seasonality in the spread of COVID-19 pandemic. Environ. Res. 2021;195:110874. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.110874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love J., Keegan L.T., Angulo F.J., et al. Continued need for non-pharmaceutical interventions after COVID-19 vaccination in long-term-care facilities. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):18093. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-97612-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharaj A.S., Parker J., Hopkins J.P., Gournis E., Bogoch I.I., Rader B., Astley C.M., Ivers N., Hawkins J.B., VanStone N., Tuite A.R., Fisman D.N., Brownstein J.S., Lapointe-Shaw L. The effect of seasonal respiratory virus transmission on syndromic surveillance for COVID-19 in Ontario, Canada. The Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2021;21(5):593–594. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00151-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu E., Ritchie H., Ortiz-Ospina E., et al. A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021;5:947–953. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01122-8. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo Clinic . 2021. Different Types of COVID-19 Vaccines: How They Work.https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/different-types-of-covid-19-vaccines/art-20506465 accessed 6 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Miles D.K., Heald A.H., Stedman M. How fast should social restrictions be eased in England as COVID-19 vaccinations are rolled out? Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021;75(7) doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama M., Hugentobler W.J., Iwasaki A. Seasonality of respiratory viral infections. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2020;7:83–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-012420-022445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicastro F., Sironi G., Antonello E., et al. Solar UV-B/A radiation is highly effective in inactivating SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):14805. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-94417-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols G.L., Gillingham E.L., Macintyre H.L., et al. Coronavirus seasonality, respiratory infections and weather. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;21(1):1101. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06785-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Our World in Data . 2021. Statistics and Research, Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations.https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations Accessed 20 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pawelec G., McElhaney J. Unanticipated efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in older adults. Immun. Ageing. 2021;18(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s12979-021-00219-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto Curiel R., González Ramírez H. Vaccination strategies against COVID-19 and the diffusion of anti-vaccination views. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):6626. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85555-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph H.E., Barreiro L.B. Herd immunity: understanding COVID-19. Immunity. 2020;52:737–741. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redwan E.M. COVID-19 pandemic and vaccination build herd immunity. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021;25(2):577–579. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202101_24613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario D.K.A., Mutz Y.S., Bernardes P.C., Conte-Junior C.A. Relationship between COVID-19 and weather: case study in a tropical country. 2020) Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2020;229:113587. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2020.113587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen B., Waitzberg R., Israeli A. Israel's rapid rollout of vaccinations for COVID-19. Isr. J. Health Pol. Res. 2021;(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s13584-021-00440-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg E.S., Holtgrave D.R., Dorabawila V., et al. New COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations among adults, by vaccination status — New York, may 3–july 25, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021. 2021;70:1150–1155. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7034e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussel M., Pontier D., Cohen J.-M., Lina B., Fouchet D. Quantifying the role of weather on seasonal influenza. 2016) BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):441. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3114-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runkle J.D., Sugg M.M., Leeper R.D., Rao Y., Matthews J.L., Rennie J.J. Short-term effects of specific humidity and temperature on COVID-19 morbidity in select US cities. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;740:140093. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Şahin M. vol. 728. Science of the Total Environment; 2020. p. 138810. (Impact of Weather on COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmadi M., Marufi Nilufar, Kazemi Moghaddam Vahid. Association of COVID-19 global distribution and environmental and demographic factors: an updated three-month study. Environ. Res. 2020;188:109748. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman B., Ferranna M., Bloom D.E. Social determinants of mortality from COVID-19: a simulation study using NHANES. PLoS Med. 2021;18(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahzamani K., Mahmoudian F., Ahangarzadeh S., et al. Vaccine design and delivery approaches for COVID-19. Int. Immunopharm. 2021;100:108086. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.108086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaman J., Galanti M. Will SARS-CoV-2 become endemic? Science. 2020;370:527–529. doi: 10.1126/science.abe5960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit A.J., Fitchett J.M., Engelbrecht F.A., Scholes R.J., Dzhivhuho G., Sweijd N.A. Winter is coming: a Southern Hemisphere perspective of the environmental drivers of SARS-CoV-2 and the potential seasonality of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17(16):5634. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi H., Kuno T., Yokoyama Y., Ueyama H., Matsushiro T., Hari Y., Ando T. The higher temperature and ultraviolet, the lower COVID-19 prevalence–meta-regression of data from large US cities. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2020;48(10):1281–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.06.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran T.N.-A., Wikle N.B., Albert E., et al. Optimal SARS-CoV-2 vaccine allocation using real-time attack-rate estimates in Rhode Island and Massachusetts. BMC Med. 2021;(1):162. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-02038-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Shaman J. Development of a model-inference system for estimating epidemiological characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):5573. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25913-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa T. Implementing vaccination policies based upon scientific evidence in Japan. Vaccine. 2021;39(38):5447–5450. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Zhou X., Qiu Y., Song Y., Feng F., Feng J., et al. Clinical characteristics of 82 cases of death from COVID-19. PLoS One. 2020;15(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Maggioni V., Houser P., Xue Y., Mei Y. The impact of weather condition and social activity on COVID-19 transmission in the United States. J. Environ. Manag. 2022;302:114085. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.114085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong J., Zhang X., Dong Y., Wang Y., Wang J., Zhang Y., et al. Feedback effects of boundary-layer meteorological factors on explosive growth of PM2.5 during winter heavy pollution episodes in Beijing from 2013 to 2016. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018;18:247e258. [Google Scholar]

- Zoran M.A., Savastru R.S., Savastru D.M., et al. vol. 152. Process Safety and Environmental Protection; 2021. pp. 583–600. (Exploring the Linkage between Seasonality of Environmental Factors and COVID-19 Waves in Madrid, Spain). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoran M.A., Savastru R.S., Savastru D.M., et al. Assessing the impact of air pollution and climate seasonality on COVID-19 multiwaves in Madrid, Spain. Environ. Res. 2022;203:111849. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]