Abstract

Background:

Due to the impact of continuous pulse oximetry (CPOX) on the overdiagnosis of hypoxemia in bronchiolitis, the AAP and the Choosing Wisely Campaign have issued recommendations for intermittent monitoring. Parental preferences for monitoring may impact adoption of these recommendations, but these perspectives are poorly understood.

Methods:

This cross-sectional survey examining parental perspectives on CPOX monitoring surveyed parents prior to and 1 week after bronchiolitis hospitalizations. During the 1-week call, half of the participants were randomized to receive a verbal statement on the potential harms of CPOX to determine whether conveying the concept of overdiagnosis can change parental preferences on monitoring frequency. An aggregate variable measuring favorable perceptions of CPOX was created to determine CPOX affinity predictors.

Results:

In-hospital interviews were completed on 357 patients, of which 306 (86%) completed the 1-week follow-up. Though 25% of parents “agreed or strongly agreed” that hospital monitors made them feel anxious, 98% agreed that the monitors were helpful. Compared to other vital signs, respiratory rate (87%) and oxygen saturation (84%) were commonly rated as “extremely important”. Providing an educational statement on CPOX decreased parental desire for continuous monitoring (40 vs. 20%, p<0.001). While there were no significant predictors of CPOX affinity, the effect size of the educational intervention was higher in college-educated parents.

Conclusions:

Parents find security in CPOX. A brief statement on the potential harm of CPOX use had an impact on monitoring preferences. Parental perspectives are important to consider, as they may be barriers to the implementation of intermittent monitoring.

Introduction

Bronchiolitis, the leading cause of infant hospitalizations in the United States, has been a common target for high-value care (HVC) efforts.1 The introduction of pulse oximetry into routine practice several decades ago was associated with a tripling of bronchiolitis hospitalization rates without an apparent reduction in mortality.2,3 Since then, convincing evidence has emerged suggesting that the overdiagnosis of hypoxemia through pulse oximetry is common in bronchiolitis and is associated with excessive hospitalization and prolonged length-of-stay (LOS).4 Concern about overdiagnosis of hypoxemia has triggered recommendations for intermittent, rather than continuous pulse oximetry (CPOX) monitoring when a child with bronchiolitis is improving.5,6 However, compliance with these recommendations remains poor,7 leading to a national effort to identify barriers to the de-implementation of CPOX.8

Parental preferences for monitoring may impact the transition to intermittent pulse oximetry use as some families see frequent monitoring as a form of reassurance.9 HVC strategies can be difficult to implement in these situations where the recommendation for physicians is to do less than the prior standard.10 This is particularly true when patients do not understand the potential harms of medical interventions and over-rely on diagnostic tests.11 The challenge however is that overdiagnosis is a poorly understood concept among patients, families, and physicians alike.12

Prior studies have shown that involving parents and patients in shared decision-making is a critical component of promoting HVC.13 Specific scripts that invite parents to share their perspectives on their child’s illness and to discuss treatment alternatives with the physician can lead to a decrease in the inappropriate utilization of antibiotics in the case of respiratory illnesses14 and acute otitis media.15 But in the unique context of pulse oximetry use in bronchiolitis hospitalizations, parental understanding of the potential harms of CPOX use may be more nuanced.

Our aims were to 1) characterize how parents of children hospitalized for bronchiolitis understand and value the importance of pulse oximetry monitoring and 2) assess whether providing information on the potential harms of CPOX use can change parental perspectives on monitoring.

Methods

Study Design

As part of a multicenter, randomized trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03354325) comparing follow-up strategies after bronchiolitis hospitalizations, we conducted an ancillary cross-sectional survey on parental perspectives on CPOX use. Participants underwent a structured interview led by a member of the research team during their child’s hospitalization (In-Hospital Interview) and received a follow-up structured interview by phone approximately one week after hospital discharge (Post-Discharge Interview). Half of the participants were randomized to receive an additional statement (Appendix) during the post-discharge interview on the potential harms of CPOX use to determine whether conveying the concept of overdiagnosis of hypoxemia can change parental preferences on the frequency of monitoring.

Study Population and Setting

We identified children <2 years of age hospitalized with a primary diagnosis of bronchiolitis during the respiratory seasons (December through April) of 2017–18 and 2018–19. Children with the following comorbidities were excluded: chronic lung disease, complex or hemodynamically significant heart disease, immunodeficiency, or neuromuscular disease. For the purpose of the primary clinical trial, enrollment was limited to patients for whom parents and medical providers were comfortable with randomization to either a scheduled or as-needed follow-up plan.

This study took place within the inpatient units of two freestanding tertiary children’s hospitals (Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford- Palo Alto, CA; Primary Children’s Hospital- Salt Lake City, UT) and two affiliated community hospitals (Packard El Camino Hospital- CA; Riverton Hospital- UT). The local institutional review boards at Stanford University and the University of Utah approved this study.

Recruitment and Data Collection

Consent, screening, and study enrollment occurred while the child was hospitalized for bronchiolitis and within 48 hours of hospital discharge. Eligibility confirmation and socio-demographic factors were obtained from the electronic medical record.

Each structured interview was conducted in either English or Spanish and responses were then transcribed into REDCap. For the in-hospital questions about monitors, research coordinators oriented the family by pointing to the monitoring devices as a prompt. We provided incentive for parents to participate in the form of a $25 dollar gift card at the completion of the first interview with an additional $25 gift card after study completion.

Interview Instrument Development

Interview questions were either adapted from existing surveys regarding parental views on other methods of continuous monitoring, including home apnea monitors for premature babies 16,17 or created de novo. Local expert consensus on both content and survey development was obtained prior to finalization of the questionnaires. To assure clarity, accuracy, and consistency of questions, initial surveys were reviewed and modified by Lucile Packard’s Family Advocacy Committee. Cognitive interview pretesting was performed on all newly written or modified interview questions and then piloted on 10 recruited participants in October 2017.

The in-hospital interview contained questions regarding parental views on vital signs, hospital monitors, and monitor alarms. The post-discharge interview contained questions specific to the pulse oximetry machine including parental knowledge of oximetry target values and their overall preference for frequency of CPOX monitoring. Monitoring preferences were obtained under the hypothetical situation of another bronchiolitis hospitalization. To reflect current recommendations of when it is appropriate to switch from continuous to intermittent pulse oximetry monitoring, parents were given the specific scenario where their child is improving and no longer requiring oxygen support.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistical techniques were performed on demographic and baseline characteristics of survey participants. Responses to 5-point Likert questions on the degree of agreement were dichotomized to agree (agree and strongly agree) and disagree (uncertain, disagree, and strongly disagree). A similar dichotomy was applied to questions on the degree of comfort. For the analysis of parental perceptions of vital sign importance, Likert responses were uniquely dichotomized to extremely important or not extremely important (all other responses) given the highly skewed distribution of parents assigning importance to all vital signs.

Responses from five questions in the post-discharge interview were combined to measure parental desire for CPOX both in the hospital and at home. From these questions, an aggregate variable, representing “CPOX affinity”, was created on a matching Likert scale of 1 through 5, with 1 representing the lowest parental desire for continuous monitoring and 5 representing the greatest. Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess internal consistency among the five questions. The standard minimum threshold of 0.7 was used to verify if the subset of questions measured the same construct.

To determine if various parent or patient characteristics could predict CPOX affinity, we conducted bivariate linear regressions with the following predictor variables: parental education, parental anxiety levels, patient race, patient insurance type, hospital LOS, and whether the patient required ICU level care. We examined potential predictors of CPOX affinity only in the control group (those who did not receive the educational intervention) given that predictors in the group who received the intervention may not be generalizable to the broader population. Because no predictor variables had a P-value <0.1, we did not perform multivariable regression.

The comparison of parental preferences for monitoring with and without the educational intervention was analyzed by Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact test, as appropriate. A two-sided P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted by using Stata 14.1 (College Station, TX).

Results

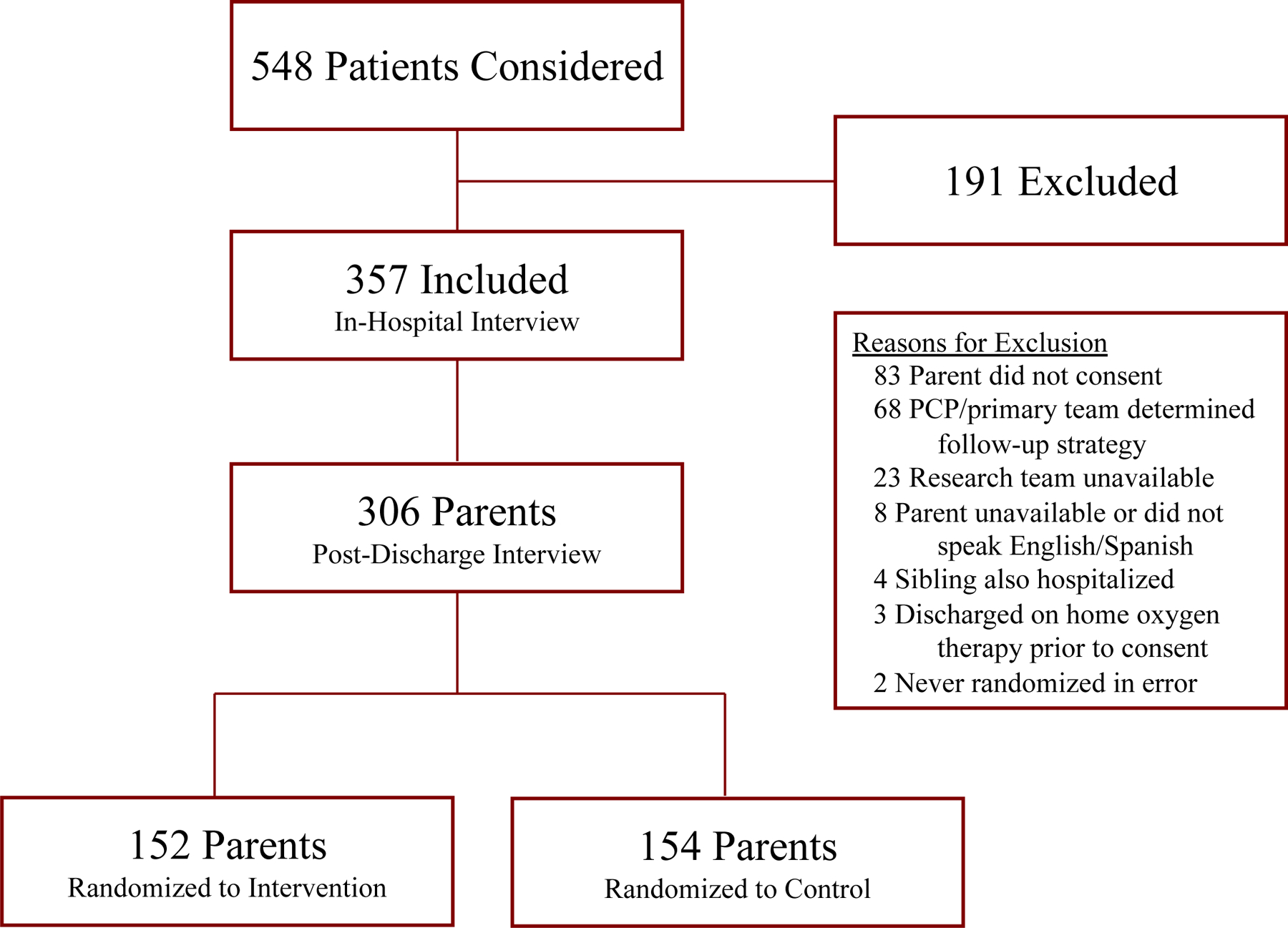

Of the 548 patients considered for enrollment, 357 (65%) patients were ultimately enrolled in the study (Figure 1). There were 306 parent responses to the post-discharge interview, representing 86% retention of enrolled patients approximately one week after hospitalization. Patient and parental demographics are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participant recruitment. PCP, primary care provider.

Table 1.

Patient and Parent Demographics

| Demographics | |

|---|---|

| Characteristic of Patient | n (%) |

|

| |

| Male | 207 (58.0) |

| Race | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 3 (0.8) |

| Asian | 23 (6.4) |

| Black/African American | 9 (2.5) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 29 (8.1) |

| White | 276 (77.3) |

| Other | 17 (4.8) |

| Hispanic | 102 (28.6) |

| Insurance | |

| Government | 143 (40.1) |

| Private/Unknown | 214 (59.9) |

| Discharged Home on Supplemental Oxygen | 53 (14.9) |

| Required ICU Care | 95 (26.6) |

|

| |

| Characteristic of Parent | n (%) |

|

| |

| Education | |

| Did not attend college | 177 (49.6) |

| Graduated college | 180 (50.4) |

| Needed Spanish Interpreter | 26 (7.3) |

Among vital signs, parents of children hospitalized with bronchiolitis viewed respiratory rate (87%) and oxygen saturation (84%) as “extremely important” (Table 2). During the in-hospital interview, nearly all parents either “strongly agreed or agreed” that having hospital monitors on their child was helpful (98%) and made them feel secure (94%) (Table 3). At the same time, some parents also “strongly agreed or agreed” that having the hospital monitors on their child was annoying (23%) and made them feel anxious (25%). When asked about monitor alarms, 140/336 (42%) of parents who spent the night “strongly agreed or agreed” that the alarms woke them up from sleep with 49% reporting more than one awakening in the night. However, only 36/357 (10%) of parents felt that the monitor alarms woke their child up from sleep.

Table 2.

Parental Perception of Vital Sign Importance, n=357

| Parents Rating Extremely Important | 95% Confidence Intervals | Mean Score* | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Blood Pressure | 38% | (33.0–43.4) | 4.1 |

| Temperature | 64% | (59.2–69.4) | 4.5 |

| Heart Rate | 67% | (62.1–72.1) | 4.6 |

| Oxygen Saturation | 84% | (80.0–87.9) | 4.8 |

| Respiratory Rate | 87% | (83.5–90.7) | 4.9 |

|

|

|||

Mean Value on Likert Scale 1–5, 1 Not at all Important and 5 Extremely Important

Table 3.

Parental Perspectives of Hospital Monitors, n=357

| Having the monitor on my child… | |

|

Strongly Agree or Agree, n (%)

|

|

| Was Helpful | 349 (97.8%) |

| Made Me Feel Secure | 336 (94.1%) |

| Was Annoying | 82 (23.0%) |

| Made Me Feel Anxious | 89 (24.9%) |

|

|

|

|

| |

| The monitor alarms in the room often… | |

|

Strongly Agree or Agree, n (%)

|

|

| Woke Up Child | 36 (10.1%) |

| Woke Up Parent* | 140 (41.9%) |

n=334 given some parents did not stay overnight

During the post-discharge phone interview, 215/306 (70%) parents reported that they were told what is considered a low oxygen level for their child. When asked to identify the oxygen saturation level at which additional oxygen support was warranted, 41% of parents reported that they “did not know”. Of the 181 that did report a value, the median response was an oxygen saturation level of 89% (range 30%−98%, interquartile range 88%−90%). To explore (post-hoc) whether this median level varied by sites, we compared responses from the California hospitals (low altitude) and Utah hospitals (high altitude) and found no differences.

The effects of the randomized, brief educational intervention explaining the potential harms of CPOX monitoring on parental preferences are summarized in Table 4. The intervention resulted in a decrease in the proportions of parents who still preferred continuous monitoring should their child be hospitalized again with bronchiolitis (40 vs. 20%, p<0.001) and an increase in parents who either strongly disagreed or disagreed with the statement, “Even if I knew it might lead to a longer hospital stay, I would prefer continuous pulse oximetry monitoring at all times,” (18 vs. 42%, p<0.001). A similar increase was observed in those who “strongly disagreed or disagreed” with the option for a home pulse oximetry machine after discharge (18 vs. 32%, p=0.003). Of note, when parents were specifically asked to agree or disagree with the statement, “There is no harm to checking the oxygen level continuously,” there was no difference between the control and intervention groups (11 vs. 10%, p=0.74).

Table 4.

Effects of an Educational Intervention on Parental Preferences, n=306

| If your child were hospitalized for bronchiolitis again and no longer needed oxygen support, how often do you think the pulse oximeter should measure your child’s oxygen level? | ||

| Intervention, n (%) | Control, n (%) | |

| Continuously | 31 (20.4) | 60 (40.0) |

| Fisher’s exact p<0.001 | ||

| If your child were hospitalized for bronchiolitis again and no longer needed oxygen support, how comfortable would you be if your doctor recommended only checking an oxygen level in your child every four hours? | ||

| Intervention, n (%) | Control, n (%) | |

| Not At All/Not Very Comfortable | 22 (14.5) | 41 (26.6) |

| Fisher’s exact p=0.009 | ||

| If I could, I would want a home machine to check oxygen levels of my child after discharge from the hospital. | ||

| Intervention, n (%) | Control, n (%) | |

| Strongly Disagree/Disagree | 49 (32.2) | 27 (17.5) |

| Fisher’s exact p=0.003 | ||

| Even if I knew it might lead to a longer hospital stay, I would prefer continuous pulse oximetry monitoring at all times. | ||

| Intervention, n (%) | Control, n (%) | |

| Strongly Disagree/Disagree | 64 (42.1) | 27 (17.5) |

| Fisher’s Exact p<0.001 | ||

| There is no harm to checking the oxygen level continuously. | ||

| Intervention, n (%) | Control, n (%) | |

| Strongly Disagree/Disagree | 15 (9.9) | 17 (11.0) |

| Fisher’s exact p=0.74 | ||

For the aggregate CPOX affinity variable, the minimum Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.7 was achieved using all 5 questions outlined in Table 4. There were no statistically significant predictors of CPOX affinity in the control group. Post-hoc, we explored the hypothesis that the efficacy of the educational intervention varied by college education. Among parents who had a college education or higher, the impact of the intervention on the CPOX affinity scale was −0.51, 95% CI [0.27, 0.75], while the impact on parents who did not have a college education was only −0.2, 95% CI [−0.04, 0.46].

Discussion

In this multicenter, cross-sectional investigation of parental perspectives on continuous pulse oximetry use, we observed several important findings. We demonstrate that parents of children hospitalized with bronchiolitis identify respiratory rate and oxygen saturation as the most important vital signs to monitor. Most parents reported that the hospital monitors gave them a sense of reassurance. We also demonstrate that a brief description of the potential harms of CPOX use can influence parental monitoring preferences.

In the last few years, the national discourse on reducing healthcare spending has identified specific areas of overtreatment in the field of pediatrics.12,18,19 One of the most frequently cited opportunities for improvement is the management of viral bronchiolitis, which has an estimated annual cost of over $1.7 billion dollars.20 Continuous pulse oximetry has been associated with the overdiagnosis of hypoxemia in bronchiolitis, driving unnecessary and prolonged hospitalizations.2,3 However, the practice of transitioning from continuous to intermittent pulse oximetry may cause anxiety for families. The majority of parents in our study reported that hospital monitors “were helpful” and “made them feel secure”. These findings are consistent with one single-institution study in Qatar by Hendaus et al. where 80% of parents supported the idea of CPOX monitoring in children hospitalized with bronchiolitis.21 The same paper speculated that parental preference for continuous monitoring may be a barrier to the widespread adoption of intermittent usage, calling for further exploration of parental perspectives and identifying the possible need to develop educational tools for parents.

In this multi-center study, we validate and expand the current understanding of parental preferences for CPOX monitoring. While parents appreciate the use of CPOX, they also acknowledge that hospital monitors “made them feel anxious” and “were annoying”. Among the parents who spent the night with their hospitalized child, 4 out of 10 parents reported that alarms woke them up from sleep. Despite these sentiments however, many parents still prefer CPOX, suggesting that the security of continuous monitoring outweighs many negative aspects of its use. While these parental preferences do not imply that parents refuse intermittent monitoring when it is recommended, they do represent an important consideration when engaging in shared decision making in the hospital and at times of recommended transition to intermittent monitoring.

The second aim of our study explores whether parental counseling can change monitoring preferences. Recent frameworks for approaching overtreatment highlight the importance of incorporating patient factors and experiences, acknowledging that patients can otherwise be barriers to reducing waste when they equate more tests and treatments to higher quality.22,23 In 2001, the Institute of Medicine stated that high quality care should be customized to individual patient needs and values.24 The challenge however is that overdiagnosis is a difficult concept to communicate.25,26 Various strategies have been proposed in an attempt to improve both patient and clinician understanding of overdiagnosis but few have proven to minimize overtreatment in practice.27 We found that a brief educational intervention on the potential harm of CPOX use could decrease parental affinity for continuous monitoring. This study provides one example where the concept of overdiagnosis was appreciated by some parents, demonstrating the impact of educational interventions on family members. This further highlights the value of patient education and how strategies to promote understanding and transparency can potentially improve compliance with recommendations.

Interventions that target patients and family members however require thoughtful consideration of various patient factors. In particular, we observed that word choice could have a direct impact on how parents interpret information that is provided to them. When parents were asked specifically to agree or disagree with the statement, “There is no harm to checking the oxygen level continuously”, the majority of parents agreed with the statement regardless of whether they received the educational intervention. The fact that many parents changed their preferences for monitoring after intervention implies that while they can appreciate the negative aspects of CPOX, they still did not equate an unnecessary and prolonged hospitalization as “harm” to their child. Another factor for consideration is the diverse spread of health literacy among patients. When stratified by parental education, we saw that the impact of our intervention had a greater effect size in parents who were college educated. This finding suggests that while overdiagnosis is a complex concept to understand, there may be opportunities to reframe our interventions to communicate effectively with a broader audience. Future endeavors hoping to incorporate parental education in HVC efforts require an astute understanding of parental health literacy and vocabulary.

Our study has several limitations. The educational intervention in this study was provided one week after hospital discharge. This decision was made both to prevent contamination of the primary study but also to avoid interfering with the care and information provided by the primary team. While the intervention changed preferences for monitoring under a hypothetical situation, it will be important to replicate the efficacy of similar interventions during the acute stress of a hospitalization in real time. Another limitation is the applicability of our educational intervention. For parents who did not change their preferences after intervention, it is possible that a different way of presenting the same information or perhaps additional facts would have been effective. Focus groups on this particular subset of parents may reveal what educational information, if any, could have changed their monitoring preferences.

Conclusion

Parents find security in continuous pulse oximetry use but a brief statement on the potential harm of overdiagnosis had an impact on preferences for monitoring. Parental perspectives are important to consider as they may be barriers to the implementation of intermittent monitoring and other high value care practices. These findings in the setting of bronchiolitis could have implications for broader strategies to combat overdiagnosis and to better engage families in high value care efforts.

Supplementary Material

Table of Contents Summary:

Through a multicenter survey, this study describes parental perspectives on continuous pulse oximetry use during bronchiolitis hospitalizations.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Continuous pulse oximetry use in bronchiolitis can lead to unnecessary or prolonged hospitalizations. Recommendations exist to transition hospitalized bronchiolitis patients to intermittent monitoring when they are improving and off oxygen supplementation. Parental perspectives on continuous pulse oximetry are largely unknown.

What This Study Adds:

In this prospective multicenter study, parents of children hospitalized for bronchiolitis find comfort in continuous monitoring even when their child is improving. A brief statement on the harms of continuous monitoring can change parental preferences.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge Carrie Rassbach, Nivedita Srinivas, Amit Singh, Natalie Pageler, and Daniel Imler for providing feedback and oversight for this project. We would like to thank the individual study coordinators for their contributions to this study. The Stanford University coordinators included: Alicia Harnett, Juliana Moreno-Ramirez, Nick Bondy, Stephanie Escobar, and Trinh Nguyen. The University of Utah coordinators included: Alexander Platt-Koch, Stacy Erickson, Evan Heller, Eun Hea Unsicker, Jillian Ivie, Karee Nicholson, Kelsee Stromberg, Lindsay Curtis, Megan Jenkins, Sharon Noorda, Tammi Lewis, and Taylor Mathie. We would also like to thank Greg Stoddard for his advice in statistical analysis.

Funding Source:

This study was funded under a joint program between Intermountain Healthcare and Stanford School of Medicine. Kevin Chi was also supported by the Stanford Maternal Child Health Research Institute through a Elizabeth and Russell Siegelman Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Abbreviations:

- CPOX

continuous pulse oximetry

- HVC

high-value care

- LOS

length-of-stay

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Clinical Trial Registration: The Bronchiolitis Follow-up Intervention Trial (BeneFIT), NCT03354325, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03354325 (Parent study). Data Sharing Statement: De-identified individual participant data will not be made immediately available.

References

- 1.Sanchez-Luna M, Elola FJ, Fernandez-Perez C, Bernal JL, Lopez-Pineda A. Trends in respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis hospitalizations in children less than 1 year: 2004–2012. Curr Med Res Opin 2016;32(4):693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinonez RA, Coon ER, Schroeder AR, Moyer VA. When technology creates uncertainty: pulse oximetry and overdiagnosis of hypoxaemia in bronchiolitis. BMJ 2017;358:j3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bajaj L, Zorc JJ. Bronchiolitis and Pulse Oximetry: Choosing Wisely With a Technological Pandora’s Box. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170(6):531–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schroeder AR, Marmor AK, Pantell RH, Newman TB. Impact of pulse oximetry and oxygen therapy on length of stay in bronchiolitis hospitalizations. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004;158(6):527–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quinonez RA, Schroeder AR. Safely doing less and the new AAP bronchiolitis guideline. Pediatrics 2015;135(5):793–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinonez RA, Garber MD, Schroeder AR, et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med 2013;8(9):479–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ralston SL, Garber MD, Rice-Conboy E, et al. A Multicenter Collaborative to Reduce Unnecessary Care in Inpatient Bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2016;137(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rasooly IR, Beidas RS, Wolk CB, et al. Measuring overuse of continuous pulse oximetry in bronchiolitis and developing strategies for large-scale deimplementation: study protocol for a feasibility trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2019;5:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly MM, Thurber AS, Coller RJ, et al. Parent Perceptions of Real-time Access to Their Hospitalized Child’s Medical Records Using an Inpatient Portal: A Qualitative Study. Hosp Pediatr 2019;9(4):273–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owens DK, Qaseem A, Chou R, Shekelle P, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of P. High-value, cost-conscious health care: concepts for clinicians to evaluate the benefits, harms, and costs of medical interventions. Ann Intern Med 2011;154(3):174–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pathirana T, Clark J, Moynihan R. Mapping the drivers of overdiagnosis to potential solutions. BMJ 2017;358:j3879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coon ER, Young PC, Quinonez RA, Morgan DJ, Dhruva SS, Schroeder AR. Update on Pediatric Overuse. Pediatrics 2017;139(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oshima Lee E, Emanuel EJ. Shared decision making to improve care and reduce costs. N Engl J Med 2013;368(1):6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altiner A, Brockmann S, Sielk M, Wilm S, Wegscheider K, Abholz HH. Reducing antibiotic prescriptions for acute cough by motivating GPs to change their attitudes to communication and empowering patients: a cluster-randomized intervention study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007;60(3):638–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merenstein D, Diener-West M, Krist A, Pinneger M, Cooper LA. An assessment of the shared-decision model in parents of children with acute otitis media. Pediatrics 2005;116(6):1267–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia J, Corry M, MacDonald D, Elbourne D, Grant A. Mothers’ views of continuous electronic fetal heart monitoring and intermittent auscultation in a randomized controlled trial. Birth 1985;12(2):79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Killien MG, Shy K. A randomized trial of electronic fetal monitoring in preterm labor: mothers’ views. Birth 1989;16(1):7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coon ER, Quinonez RA, Moyer VA, Schroeder AR. Overdiagnosis: how our compulsion for diagnosis may be harming children. Pediatrics 2014;134(5):1013–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chassin MR, Galvin RW. The urgent need to improve health care quality. Institute of Medicine National Roundtable on Health Care Quality. JAMA 1998;280(11):1000–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasegawa K, Tsugawa Y, Brown DF, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA Jr. Trends in bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the United States, 2000–2009. Pediatrics 2013;132(1):28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendaus MA, Nassar S, Leghrouz BA, Alhammadi AH, Alamri M. Parental preference and perspectives on continuous pulse oximetry in infants and children with bronchiolitis. Patient Prefer Adherence 2018;12:483–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan DJ, Leppin AL, Smith CD, Korenstein D. A Practical Framework for Understanding and Reducing Medical Overuse: Conceptualizing Overuse Through the Patient-Clinician Interaction. J Hosp Med 2017;12(5):346–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(2):223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.In: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century Washington (DC)2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghanouni A, Renzi C, Waller J. Improving public understanding of ‘overdiagnosis’ in England: a population survey assessing familiarity with possible terms for labelling the concept and perceptions of appropriate terminology. BMJ Open 2018;8(6):e021260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ralston SL, Schroeder AR. Why It Is So Hard to Talk About Overuse in Pediatrics and Why It Matters. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171(10):931–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCaffery KJ, Jansen J, Scherer LD, et al. Walking the tightrope: communicating overdiagnosis in modern healthcare. BMJ 2016;352:i348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.