Abstract

Background

Chemoimmunotherapy has become a standard treatment option for patients with untreated advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC). However, numerous patients with advanced NSCLC develop disease progression. Therefore, the selection of second‐line treatment after chemoimmunotherapy is crucial for improving clinical outcomes.

Methods

Of 88 enrolled patients with advanced NSCLC who received chemoimmunotherapy, we retrospectively evaluated 33 who received second‐line chemotherapy after progression of chemoimmunotherapy at six centers in Japan. Among them, 18 patients received docetaxel plus ramucirumab and 15 patients received single‐agent chemotherapy.

Results

The objective response rate in patients treated with docetaxel plus ramucirumab was significantly higher than that in patients treated with a single‐agent chemotherapy regimen (55.6% vs. 0%, p < 0.001). The median progression‐free survival (PFS) of patients who received docetaxel plus ramucirumab and single‐agent chemotherapy was 5.8 months and 5.0 months, respectively (log‐rank test p = 0.17). In the docetaxel plus ramucirumab regimen group, patients who responded to chemoimmunotherapy for ≥8.8 months had a significantly longer response to docetaxel plus ramucirumab than those who responded for <8.8 months (not reached vs. 4.1 months, log‐rank test p = 0.003). In contrast, in the single‐agent chemotherapy group, there was no significant difference in PFS between the ≥8.8‐ and <8.8‐month PFS groups with chemoimmunotherapy (5.0 vs. 1.6 months, log‐rank test p = 0.66).

Conclusion

Our retrospective observations suggest that the group with longer PFS with chemoimmunotherapy might be expected to benefit from docetaxel plus ramucirumab treatment in second‐line settings for patients with advanced NSCLC.

Keywords: chemoimmunotherapy, docetaxel plus ramucirumab, non‐small‐cell lung cancer, performance status

We investigated the benefit of docetaxel plus ramucirumab as a second‐line therapy after chemoimmunotherapy compared to single‐agent chemotherapy in a real world setting. In second‐line settings, longer PFS with chemoimmunotherapy might be expected to benefit from docetaxel plus ramucirumab treatment for patients with advanced NSCLC.

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer‐related deaths worldwide. 1 In recent years, the prognosis of patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been gradually improving. 2 One of the main reasons is that combination therapy of imuune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and chemotherapy has been established as a standard treatment option for patients with advanced NSCLC. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 However, even with chemoimmunotherapy in the initial phase, numerous patients with NSCLC eventually develop disease progression.

Docetaxel plus ramucirumab is now frequently used as the standard chemotherapeutic regimen for second‐line treatment based on the results of a clinical phase III trial. 7 The efficacy and safety of docetaxel plus ramucirumab as a second‐line treatment for advanced NSCLC have been similarly demonstrated in a Japanese cohort. 8 In addition, single‐agent chemotherapy, such as with docetaxel, TS‐1, and nab‐paclitaxel, has been administered in the second‐line setting for patients with advanced NSCLC. 9 , 10 , 11 More recently, a retrospective study showed that docetaxel plus ramucirumab is an effective and safe second‐line therapy after chemoimmunotherapy. 12 However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have compared docetaxel plus ramucirumab and single‐agent chemotherapy after chemoimmunotherapy in the real‐world setting. This is important because the real‐world setting includes ineligible patients for clinical trials, such as patients with poor performance status (PS) and central nervous system metastases. 13

In this retrospective study, we investigated the safety, efficacy, and biomarkers of docetaxel plus ramucirumab as a second‐line therapy after chemoimmunotherapy compared to single‐agent chemotherapy in a real‐world setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients with NSCLC who received chemoimmunotherapy between January and December 2019 were selected. Among them, those who received second‐line chemotherapy after progression of chemoimmunotherapy were included. All patients had target lesions at the start of second‐line chemotherapy. Patients were excluded if they had epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) activating mutations or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) arrangement fusion, received platinum‐containing therapy, or had missing data on second‐line chemotherapy. All patients underwent conventional procedures such as conventional computed tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version1.1. Assessment of treatment effect by CT scans was performed every 1–3 months. The programmed death‐ligand 1 (PD‐L1) expression was analyzed by SRL, Inc. using a PD‐L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx assay (Agilent Technologies). Progression‐free survival (PFS) was defined as the date from the start of docetaxel plus ramucirumab or single‐agent chemotherapy to the date of the first tumor progression event. Overall survival (OS) was also calculated from the start of docetaxel plus ramucirumab or single‐agent chemotherapy. The median follow‐up time from the start date of second‐line treatment was 9 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 7.5–10.5 months) while the median follow‐up time from the first treatment start date was 23 months (95% CI 20.8–25.2 months). The following clinical data were obtained from medical records retrospectively: age, gender, smoking status, histological subtype, PD‐L1 tumor proportion score (TPS), disease stage, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group PS (ECOG‐PS), PFS, OS, overall response rate (ORR), and history of chemoimmunotherapy before and after treatment with docetaxel plus ramucirumab or single‐agent anticancer drugs. The tumor–node–metastasis (TNM) stage was classified using version 8 of the TNM stage classification system. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine and the Ethics Committees of each hospital (approval no. ERB‐C‐1803). Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Definition of neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio, Glasgow prognostic score, prognostic nutritional index, and cancer cachexia

The cut‐off values for the neutrophil‐to‐lymphocyte ratio, Glasgow prognostic score, and prognostic nutritional index were determined according to previous studies. 14 , 15 , 16 For cancer cachexia, we used the following previously reported criteria: weight loss exceeding 5% of the total body weight or a body mass index of <20 kg/m2 and weight loss of more than 2% of the total body weight within 6 months before treatment initiation, with laboratory results exceeding reference values (C‐reactive protein >0.5 mg/dl, serum albumin <3.2 g/dl, or hemoglobin <12 g/dl). 17

Statistical analysis

PFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences were compared using the log‐rank test. Statistical analyses for continuous and categorical variables were conducted using Student's t‐test, Mann–Whitney U test, and Fisher's exact test. The hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% CIs were estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model in univariate and multivariate analyses. In the subgroup analysis of the overall population, the docetaxel‐plus ramucirumab regimen was used as a covariate to correct for differences in regimens. In the pivotal clinical studies, the median PFS of chemoimmunotherapy was 6.4–8.8 months, 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 therefore we divided the patients into two groups, those who responded to chemoimmunotherapy and those who did not respond, using a cutoff of 8.8 months, to evaluate the impact of prior chemoimmunotherapy on the outcomes of second‐line chemotherapy. Statistical analyses were performed using the EZR statistical software, version 1.54. 18 All statistical tests were two‐sided and statistical significance was set at p values <0.05.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

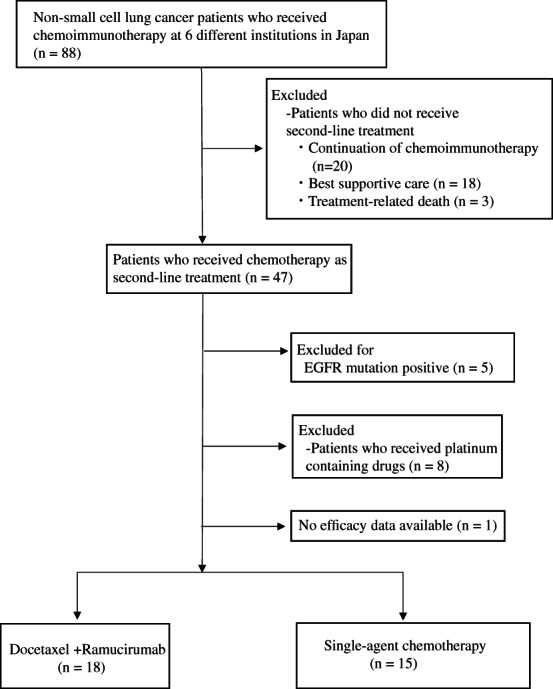

We enrolled 88 patients with advanced NSCLC who received chemoimmunotherapy at six different institutions in Japan. Sixty‐seven patients with advanced NSCLC developed disease progression. Forty‐seven patients with advanced NSCLC received second‐line chemotherapy following chemoimmunotherapy. Among them, 18 patients who received docetaxel plus ramucirumab and 15 patients who received single‐agent chemotherapy were evaluated. NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations or ALK arrangement fusion were excluded from this analysis. Patients who were alive and progression‐free until the end of May 2021 were censored. Finally, 33 patients who received second‐line treatment were enrolled and analyzed in this study (Figure 1). Eighteen patients (52.7%) received docetaxel and ramucirumab, and 15 patients (47.3%) received single‐agent chemotherapy (Table 1). The median age of the patients with NSCLC treated with docetaxel and ramucirumab was 68.5 years (range 43–79 years), 11 (69.7%) patients were male, 16 (88.9%) had a history of smoking, and three (16.7%) had a PD‐L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) ≥50%. Among those who received single‐agent chemotherapy, 11 received docetaxel and four received TS‐1. The median age was 73 years (range, 63–79 years), 12 (80.0%) patients were male, 12 (80.0%) had a history of smoking, and six (40%) had a PD‐L1 TPS ≥50%. The docetaxel plus ramucirumab cohort was significantly younger than the single‐agent chemotherapy regimen cohort (p = 0.03).

FIGURE 1.

Consort diagram of the study

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 33) | DOC + RAM (n = 18, 52.7%) | Single‐agent chemotherapy a (n = 15, 47.3%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Median (range) | 70 (43–79) | 68.5 (43–79) | 73 (63–79) | 0.03 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 23 (69.7%) | 11(61.1%) | 12 (80.0%) | 0.28 |

| Female | 10 (30.3%) | 7 (38.9%) | 3 (20.0%) | |

| ECOG‐PS | ||||

| 0 | 9 (27.3%) | 5 (27.8%) | 4 (26.7%) | 1.0 |

| 1 | 20 (60.6%) | 11 (61.1%) | 9 (60.0%) | |

| 2 | 4 (12.1%) | 2 (11.1%) | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Stage | ||||

| III/IV | 5 (15.2%) | 3 (16.7%) | 2 (13.3%) | 1.0 |

| Recurrence | 28 (84.8%) | 15 (83.3%) | 13 (86.7%) | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current/former | 28 (84.8%) | 16 (88.9%) | 12 (80.0%) | 0.64 |

| Never | 5 (15.2%) | 2 (11.1%) | 3 (20.0%) | |

| Histology | ||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 8 (24.2%) | 2 (11.1%) | 6 (40.0%) | 0.10 |

| Nonsquamous cell carcinoma | 25 (75.8%) | 16 (88.9%) | 9 (60.0%) | |

| Previous chemoimmunotherapy regimen | ||||

| Platinum + pemetrexed + pembrolizumab | 18 (54.5%) | 12 (66.7%) | 6 (40.0%) | |

| Carboplatin + paclitaxel/nab‐paclitaxel + pembrolizumab | 12 (36.4%) | 3 (16.7%) | 9 (60.0%) | |

| Carboplatin + paclitaxel + atezolizumab + bevacizumab | 2 (6.0%) | 2 (11.1%) | 0 | |

| Carboplatin + nab‐paclitaxel + atezolizumab | 1 (3.0%) | 1 (5.6%) | 0 | |

| PD‐L1 TPS | ||||

| ≥50% | 9 (27.3%) | 3 (16.7%) | 6 (40%) | 0.25 |

| 1%–49% | 14 (42.4%) | 7 (38.9%) | 7 (46.7%) | |

| <1% | 6 (18.2%) | 5 (27.8%) | 1 (6.7%) | |

| Unknown | 4 (12.1%) | 3 (16.7%) | 1 (6.7%) | |

| Brain metastasis | ||||

| Yes | 5 (15.2%) | 2 (11.1%) | 3 (20.0%) | 0.64 |

| No | 28 (84.8%) | 16 (88.9%) | 12 (80.0%) | |

| Liver metastasis | ||||

| Yes | 5 (15.2%) | 2 (11.1%) | 3 (20.0%) | 0.64 |

| No | 28 (84.8%) | 16 (88.9%) | 12 (80.0%) | |

| Time from last ICI administration to start of second‐line chemotherapy | ||||

| Median months (range) | 1.1 months (0.7–18.4) | 1.55 months (0.7–9.3) | 1.0 months (0.7–18.4) | 0.68 |

| Best response to chemoimmunotherapy, n (%) | ||||

| CR/PR/SD | 29 (87.9%) | 16 (88.9%) | 13 (86.7%) | 1.0 |

| PD | 1 (3.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (6.7%) | |

| NE | 3 (9.1%) | 2 (11.1%) | 1 (6.7%) | |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; DOC, docetaxel; ECOG‐PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; NE, not evaluable; PD, progressive disease; PD‐L1 TPS, Programmed Death Ligand 1 Tumor Proportion Score; PR, partial response; RAM, ramucirumab; SD, stable disease.

11 patients received docetaxel and four patients received TS‐1.

Efficacy of docetaxel and ramucirumab in patients with advanced NSCLC after chemoimmunotherapy

The ORR in patients with NSCLC treated with docetaxel plus ramucirumab was significantly better than that in patients treated with single‐agent chemotherapy (55.6%, 95% CI 30.8–78.5% vs. 0%, 95% CI 0–21.6%, p < 0.001). In contrast, there was no significant difference in the disease control rate (DCR) between patients with NSCLC treated with docetaxel and ramucirumab and those treated with single‐agent chemotherapy regimens (83.3%, 95% CI 58.6–96.4% vs. 60.0%, 95% CI 32.3–83.7%, p = 0.24). The response after initiation of second‐line chemotherapy could not be evaluated in one patient (Table 2). The median PFS and OS of patients with advanced NSCLC who received second‐line treatment were 5.0 and 11.2 months, respectively (Supporting Information Figure SS1a,b). The median PFSs of patients with advanced NSCLC who received docetaxel plus ramucirumab and single‐agent chemotherapy were 5.8 and 5.0 months (HR 0.56, 95% CI 0.25–1.29, log‐rank test p = 0.17), respectively, with no significant difference. The median OS of patients with advanced NSCLC who received docetaxel and ramucirumab was 10.7 months and that of patients who received single‐agent chemotherapy was 17.6 months (HR 1.25, 95% CI 0.42–3.69, log‐rank test p = 0.69) (Supporting Information Figure SS1). The median PFS and OS with chemoimmunotherapy were 9.1 and 27.4 months, respectively, for the 33 patients with advanced NSCLC (Supporting Information Figure S2a,b).

TABLE 2.

Response to second‐line treatment

| Response | All patients (n = 33) | DOC + RAM (n = 18, 52.7%) | Single‐agent chemotherapy (n = 15, 47.3%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Complete response (95% CI) |

0 (0%) (0–10.6) |

0 (0%) (0–18.5) |

0 (0%) (0–21.8) |

|

|

Partial response (95% CI) |

10 (30.3%) (15.6–48.7) |

10 (55.6%) (30.8–78.5) |

0 (0%) (0–21.8) |

|

|

Stable disease (95% CI) |

14 (42.4%) (25.5–60.8) |

5 (27.8%) (9.7–53.5) |

9 (60.0%) (32.3–83.7) |

|

|

Progressive disease (95% CI) |

8 (24.2%) (11.1–42.3) |

3 (16.7%) (3.6–41.4) |

5 (33.3%) (11.8–61.6) |

|

|

Not evaluable (95% CI) |

1 (3.0%) (0.1–15.8) |

0 (0%) (0–18.5) |

1 (6.7%) (0.2–31.9) |

|

|

Objective response rate (95% CI) |

10 (30.3%) (15.6–48.7) |

10 (55.6%) (30.8–78.5) |

0 (0%) (0–21.8) |

<0.001 |

|

Disease control rate (95% CI) |

24 (72.7%) (54.5–86.7) |

15 (83.3%) (58.6–96.4) |

9 (60.0%) (32.3–83.7) |

0.24 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DOC, docetaxel; RAM, ramucirumab.

To investigate the association with PFS between chemoimmunotherapy and second‐line chemotherapy, we divided the patients into two groups based on a PFS cut‐off of 8.8 months for chemoimmunotherapy. In the docetaxel plus ramucirumab regimen group, the group with PFS ≥8.8 months (n = 8) with chemoimmunotherapy had significantly longer PFS than the PFS < 8.8‐month group (n = 10) (not reached vs. 4.1 months; HR 0.12, 95% CI 0.03–0.48, log‐rank test p = 0.003) (Figure 2a). In contrast, in the single‐agent chemotherapy group, there was no significant difference in the PFS with single‐agent chemotherapy between the PFS ≥8.8‐month (n = 8) and <8.8‐month (n = 7) groups with chemoimmunotherapy (5.0 vs. 1.6 months; HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.23–2.57, log‐rank test p = 0.66) (Figure 2b).

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve for progression‐free survival (PFS) in non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients who received (a) second‐line treatment, (b) second‐line treatment compared with docetaxel plus ramucirumab and single‐agent chemotherapy, (c) docetaxel plus ramucirumab compared with PFS 1st (≥8.8 vs. <8.8 months), and (d) single‐agent chemotherapy compared with PFS 1st (≥8.8 vs. <8.8). PFS 1st, PFS in chemoimmunotherapy

Finally, we investigated the prognostic factors of second‐line treatment after chemoimmunotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC. In the univariate and multivariate analyses, ECOG‐PS = 2 was associated with PFS (HR 7.58, 95% CI 2.21–26.1, p = 0.001 and HR 6.66, 95% CI 1.77–25.0, p = 0.005, respectively) and OS (HR 3.56, 95% CI 1.11–11.4, p = 0.03 and HR 3.73, 95% CI 1.06–13.1, p = 0.04, respectively). In the multivariate analyses, the docetaxel plus ramucirumab regimen was associated with PFS (HR 0.40, 95% CI 0.16–0.98, p = 0.045) (Tables 3 and 4).

TABLE 3.

Cox proportional hazard models for progression‐free survival (PFS) in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer who received second‐line treatment

| Items | PFS (univariate analysis) | PFS (multivariate analysis) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Male sex | 0.39 (0.16–0.96) | 0.04 | 0.43 (0.16–1.13) | 0.09 |

| Age, years, ≥75 | 2.00 (0.73–5.46) | 0.18 | ||

| Recurrence | 0.47 (0.11–2.04) | 0.32 | ||

| ECOG‐PS = 2 a | 7.58 (2.21–26.1) | 0.001 | 6.66 (1.77–25.0) | 0.005 |

| PD‐L1 ≥ 50% b | 1.12 (0.45–2.83) | 0.80 | ||

| Cachexia c | 1.16 (0.48–2.79) | 0.74 | ||

| DOC+RAM d | 0.56 (0.25–1.29) | 0.17 | 0.40 (0.16–0.98) | 0.045 |

| Smoker | 0.41 (0.13–1.24) | 0.12 | ||

| Liver metastasis | 2.65 (0.95–7.43) | 0.06 | ||

| Brain metastasis | 2.10 (0.69–6.45) | 0.19 | ||

| GPS ≥1 | 2.37 (0.97–5.77) | 0.06 | ||

| NLR ≥3 | 1.72 (0.72–4.07) | 0.22 | ||

| PNI ≥45.5 | 0.67 (0.26–1.71) | 0.40 | ||

Note: Univariate and multivariate analyses.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DOC, docetaxel; ECOG‐PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group‐Performance Status; GPS, Glasgow Prognostic Score; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PD‐L1, programmed death ligand 1; PNI, Prognostic Nutritional Index; RAM, ramucirumab.

ECOG‐PS = 2 vs. ECOG‐PS <2.

PD‐L1 TPS ≥50% vs. all others, except for unknown.

Weight loss amounting to >5% of body weight (BW) or body mass index <20 kg/m2 and weight loss amounting to >2% of BW with laboratory results exceeding reference values. Laboratory results exceeding reference values: C‐reactive protein > 0.5 mg/dl, serum Albumin < 3.2 g/dl, or Hemoglobin < 12 g/dl.

DOC + RAM versus single‐agent chemotherapy.

TABLE 4.

Cox proportional hazard models for overall survival (OS) in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer who received second‐line treatment

| Items | OS (univariate analysis) | OS (multivariate analysis) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Male sex | 0.44 (0.16–1.22) | 0.11 | ||

| Age, years, ≥75 | 2.14 (0.67–6.79) | 0.20 | ||

| Recurrence | NA | NA | ||

| ECOG‐PS = 2 a | 3.56 (1.11–11.4) | 0.03 | 3.73 (1.06–13.1) | 0.04 |

| PD‐L1 ≥ 50% b | 0.64 (0.20–2.08) | 0.46 | ||

| Cachexia c | 1.91 (0.70–5.20) | 0.21 | ||

| DOC + RAM d | 1.25 (0.42–3.69) | 0.69 | 0.89 (0.29–2.78) | 0.84 |

| Smoker | 0.97 (0.26–3.58) | 0.96 | ||

| Liver metastasis | 2.16 (0.68–6.83) | 0.19 | ||

| Brain metastasis | 1.31 (0.29–5.91) | 0.73 | ||

| GPS ≥1 | 2.06 (0.72–5.88) | 0.18 | ||

| NLR ≥3 | 2.08 (0.73–5.92) | 0.17 | ||

| PNI ≥45.5 | 0.40 (0.11–1.40) | 0.15 | ||

Note: Univariate and multivariate analyses.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DOC, docetaxel; ECOG‐PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group‐Performance Status; GPS, Glasgow Prognostic Score; NLR, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio; PD‐L1, programmed death ligand 1; PNI, Prognostic Nutritional Index; RAM, ramucirumab.

ECOG‐PS = 2 vs. ECOG‐PS <2.

PD‐L1 TPS ≥50% vs. all others, except for unknown.

Weight loss amounting to >5% of the body weight (BW) or body mass index <20 kg/m2 and weight loss amounting to >2% of BW with laboratory results exceeding reference values. Laboratory results exceeding reference values: C‐reactive protein > 0.5 mg/dl, serum Albumin <3.2 g/dl, or Hemoglobin < 12 g/dl.

DOC + RAM versus single‐agent chemotherapy.

Safety of docetaxel and ramucirumab in patients with advanced NSCLC after chemoimmunotherapy

The incidence of grade ≥3 adverse events is shown in Table 5. In patients with NSCLC treated with docetaxel plus ramucirumab, the incidence of grade ≥3 neutropenia was 16.7% (three of 18). In patients with NSCLC treated with single‐agent chemotherapy, the incidence of grade ≥3 neutropenia was 33.3% (five of 15). There was no significant difference in the incidence of grade ≥3 hematological (p = 0.13) and nonhematological toxicities (p = 0.58) between the docetaxel plus ramucirumab and single‐agent chemotherapy groups. There were no treatment‐related deaths in either cohort. In the docetaxel plus ramucirumab regimen group, one patient discontinued treatment due to cutaneous recall phenomenon at the site of previous docetaxel extravasation.

TABLE 5.

The incidence of grade ≥3 adverse events

| Adverse events | DOC + RAM (n = 18, 52.7%) | Single‐agent chemotherapy (n = 15, 47.3%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade ≥3, n (%) | Grade ≥3, n (%) | ||

| Hematologic toxicity | |||

| Any | 3 (16.7%) | 7 (46.7%) | 0.13 |

| Neutropenia | 3 (16.7%) | 5 (33.3%) | |

| Febrile neutropenia | 1 (6.7%) | ||

| Anemia | 1 (6.7%) | ||

| Nonhematologic toxicity | |||

| Any | 1 (5.6%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0.58 |

| Fatigue | 2 (13.3%) | ||

| Diarrhea | 1 (6.7%) | ||

| Vasculitis | 1 (5.6%) | ||

Abbreviations: DOC, docetaxel; RAM, ramucirumab.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we retrospectively evaluated the benefit of docetaxel plus ramucirumab following chemoimmunotherapy compared to single‐agent chemotherapy in a second‐line setting. The ORR was significantly higher in patients treated with docetaxel plus ramucirumab than in those treated with single‐agent chemotherapy, consistent with a pivotal study. 7 Previous studies showed that the previous administration of ICIs increases the efficacy of docetaxel plus ramucirumab therapy due to the maintenance of the efficacy of prior ICI treatment for several months. 19 , 20 It is possible that prior chemoimmunotherapy use induces the increase in ORR to docetaxel plus ramucirumab. Interestingly, PFS positively correlated with prior chemotherapy and second‐line docetaxel plus ramucirumab. In contrast, PFS with single‐agent chemotherapy did not correlate with prior chemoimmunotherapy. Considering this difference in the impact of prior chemoimmunotherapy, the subsequent angiogenesis inhibitor ramucirumab might play an important role in the second‐line treatment. One hypothesis is that the vascular epithelial growth factor (VEGF)/VEGFR axis may be involved in resistance after long‐term disease stabilization by chemoimmunotherapy. Functional abnormalities of blood vessels in tumors result in poor blood flow and promotion of a hypoxic tumor microenvironment (TME). Hypoxia within the tumor attenuates the therapeutic effects of immunotherapy, radiation therapy, and cytotoxic anticancer agents. 21 Theoretically, the anti‐VEGFR2 antibody ramucirumab may have a positive impact on overcoming resistance after long‐term chemoimmunotherapy through improvement of the hypoxic TME.

Previous reports have shown that primary or adaptive resistance to immunotherapy has several mechanisms, including lack of tumor antigens, activation of various signaling pathways (mitogen‐activated protein kinase, PI3K, and WNT), lack of antigen presentation function, and constitutive expression of PD‐L1. 22 Highly heterogeneous tumors also result in a poor response to anticancer therapy, including molecular‐targeted therapy and chemotherapy. 23 These findings suggest that the heterogeneity of pretreatment tumors might be closely related to the involvement of various resistances with a complicated TME, therefore additional inhibition of VEGF might lead to insufficient clinical outcome.

In our study, two patients who received the anti‐VEGF antibody bevacizumab‐containing chemoimmunotherapy were enrolled in the docetaxel plus ramucirumab group. An exploratory analysis of pivotal studies reported that the response rate to docetaxel plus ramucirumab was reduced with prior bevacizumab treatment compared to no prior bevacizumab treatment, although PFS and OS were unchanged. 24 In this study, the number of cases to evaluate the efficacy of docetaxel plus ramucirumab treatment after chemoimmunotherapy, including angiogenesis inhibitors, was quite small, and further validation is needed. In the East‐LC trial, with a total of 1154 patients enrolled, the response rates were 8.3% and 9.9% in the S‐1 and docetaxel arms after platinum‐based chemotherapy, respectively. 10 In contrast, in this study, the response rate in patients treated with single‐agent chemotherapy after chemoimmunotherapy was 0%. The difference in the response rate might be as a result of the sample size (n = 15) because the 95% CI for the response rate in the single‐agent chemotherapy was 0.0–21.6%. Previous studies have shown that ECOG‐PS = 2 is a poor prognostic factor for docetaxel alone or docetaxel plus ramucirumab therapy in previously treated patients with NSCLC. 25 , 26 We retrospectively demonstrated that a poor PS (ECOG‐PS = 2) was an independent prognostic factor for PFS and OS in the second‐line setting after chemoimmunotherapy. Therefore, the decision to use second‐line therapy following chemoimmunotherapy for NSCLC patients with a poor PS should be made with caution.

Our study had several limitations. First, the sample size was small. The reason for the lack of significant differences in PFS between the docetaxel plus ramucirumab and single‐agent chemotherapy groups may be due to the sample size. Further investigations are needed to verify these results. Second, there may be a bias in the choice of docetaxel plus ramucirumab as a second‐line therapy. For example, the docetaxel plus ramucirumab group was younger than the single‐agent chemotherapy group. In addition, in cases where there are contraindications to the administration of angiogenesis inhibitors, single‐agent chemotherapy was chosen. Third, all the patients in the cohort were Japanese. Racial differences must also be considered.

Together, our retrospective findings showed that longer PFS with chemoimmunotherapy might be expected to benefit from docetaxel plus ramucirumab treatment in the second‐line setting for patients with advanced NSCLC. Further studies are required to confirm these observations.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

T.Y. received grants from Pfizer, Ono Pharmaceutical, Chugai Pharmaceutical, and Takeda Pharmaceutical. K.T. received grants from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, MSD, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi Sankyo. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information Figure S1 Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival (OS) (A) in non‐small‐cell lung cancer patients who received second line treatment. Kaplan–Meier curves for OS (B) in non‐small‐cell lung cancer patients who received second‐line treatment compared with docetaxel plus ramucirumab and single‐agent chemotherapy

Supporting Information Figure S2 Kaplan–Meier curves for progression‐free survival (A) and overall survival (B) in chemoimmunotherapy

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patients, their families, and all investigators involved in this study. Additionally, we thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for their help with English language editing.

Ishida M, Morimoto K, Yamada T, Shiotsu S, Chihara Y, Yamada T, et al. Impact of docetaxel plus ramucirumab in a second‐line setting after chemoimmunotherapy in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer: A retrospective study. Thorac Cancer. 2022;13:173–181. 10.1111/1759-7714.14236

REFERENCES

- 1. Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Ortiz AP, Fedewa SA, Pinheiro PS, Tortolero‐Luna G, et al. Cancer statistics for Hispanics/Latinos, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):425–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Howlader N, Forjaz G, Mooradian MJ, Meza R, Kong CY, Cronin KA, et al. The effect of advances in lung‐cancer treatment on population mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):640–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gandhi L, Rodríguez‐Abreu D, Gadgeel S, Esteban E, Felip E, de Angelis F, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2078–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paz‐Ares L, Luft A, Vicente D, Tafreshi A, Gümüş M, Mazières J, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(21):2040–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, Orlandi F, Stroyakovskiy D, Nogami N, et al. Atezolizumab for first‐line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(24):2288–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paz‐Ares L, Ciuleanu TE, Cobo M, Schenker M, Zurawski B, Menezes J, et al. First‐line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): an international, randomised, open‐label, phase 3 trial [published correction appears in Lancet Oncol. 2021 Mar;22(3):e92]. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(2):198–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garon EB, Ciuleanu TE, Arrieta O, Prabhash K, Syrigos KN, Goksel T, et al. Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel for second‐line treatment of stage IV non‐small‐cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum‐based therapy (REVEL): a multicentre, double‐blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9944):665–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoh K, Hosomi Y, Kasahara K, Yamada K, Takahashi T, Yamamoto N, et al. A randomized, double‐blind, phase II study of ramucirumab plus docetaxel vs placebo plus docetaxel in Japanese patients with stage IV non‐small cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum‐based therapy. Lung Cancer. 2016;99:186–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, Mattson K, Gralla R, O'Rourke M, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum‐based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(10):2095–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nokihara H, Lu S, Mok TSK, Nakagawa K, Yamamoto N, Shi YK, et al. Randomized controlled trial of S‐1 versus docetaxel in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum‐based chemotherapy (East Asia S‐1 trial in lung cancer). Ann Oncol. 2017;28(11):2698–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yoneshima Y, Morita S, Ando M, Nakamura A, Iwasawa S, Yoshioka H, et al. Phase 3 trial comparing nanoparticle albumin‐bound paclitaxel with docetaxel for previously treated advanced NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(9):1523–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brueckl WM, Reck M, Rittmeyer A, Kollmeier J, Wesseler C, Wiest GH, et al. Efficacy of docetaxel plus ramucirumab as palliative second‐line therapy following first‐line chemotherapy plus immune‐checkpoint‐inhibitor combination treatment in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) UICC stage IV. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021;10(7):3093–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kawachi H, Fujimoto D, Morimoto T, Ito M, Teraoka S, Sato Y, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer who are ineligible for clinical trials. Clin Lung Cancer. 2018;19(5):e721–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Akinci Ozyurek B, Sahin Ozdemirel T, Buyukyaylaci Ozden S, Erdogan Y, Kaplan B, Kaplan T. Prognostic value of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in lung cancer cases. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18(5):1417–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Angerson WJ, Dunlop DJ. Comparison of an inflammation‐based prognostic score (GPS) with performance status (ECOG) in patients receiving platinum‐based chemotherapy for inoperable non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(9):1704–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shoji F, Takeoka H, Kozuma Y, Toyokawa G, Yamazaki K, Ichiki M, et al. Pretreatment prognostic nutritional index as a novel biomarker in non‐small cell lung cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Lung Cancer. 2019;136:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morimoto K, Uchino J, Yokoi T, Kijima T, Goto Y, Nakao A, et al. Impact of cancer cachexia on the therapeutic outcome of combined chemoimmunotherapy in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer: a retrospective study. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;10(1):1950411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy‐to‐use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(3):452–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shiono A, Kaira K, Mouri A, Yamaguchi O, Hashimoto K, Uchida T, et al. Improved efficacy of ramucirumab plus docetaxel after nivolumab failure in previously treated non‐small cell lung cancer patients. Thorac Cancer. 2019;4:775–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yoshimura A, Yamada T, Okuma Y, Kitadai R, Takeda T, Kanematsu T, et al. Retrospective analysis of docetaxel in combination with ramucirumab for previously treated non‐small cell lung cancer patients. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019;4:450–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fukumura D, Kloepper J, Amoozgar Z, Duda DG, Jain RK. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using antiangiogenics: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(5):325–40. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sharma P, Hu‐Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, Ribas A. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;168(4):707–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dagogo‐Jack I, Shaw AT. Tumor heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(2):81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Garon EB, Scagliotti GV, Gautschi O, Reck M, Thomas M, Iglesias Docampo L, et al. Exploratory analysis of front‐line therapies in REVEL: a randomised phase 3 study of ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus docetaxel for the treatment of stage IV non‐small‐cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum‐based therapy. ESMO Open. 2020;5:e000567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Califano R, Griffiths R, Lorigan P, Ashcroft L, Taylor P, Burt P, et al. Randomised phase II trial of 4 dose levels of single agent docetaxel in performance status (PS) 2 patients with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): DOC PS2 trial. Manchester lung cancer group. Lung Cancer. 2011;73(3):338–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matsumoto K, Tamiya A, Matsuda Y, Taniguchi Y, Atagi S, Kawachi H, et al. Impact of docetaxel plus ramucirumab on metastatic site in previously treated patients with non‐small cell lung cancer: a multicenter retrospective study. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021;10(4):1642–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information Figure S1 Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival (OS) (A) in non‐small‐cell lung cancer patients who received second line treatment. Kaplan–Meier curves for OS (B) in non‐small‐cell lung cancer patients who received second‐line treatment compared with docetaxel plus ramucirumab and single‐agent chemotherapy

Supporting Information Figure S2 Kaplan–Meier curves for progression‐free survival (A) and overall survival (B) in chemoimmunotherapy