Abstract

Cognitive control describes the ability to use internal goals to strategically guide how we process and respond to our environment. Changes in the environment lead to adaptation in control strategies. This type of control-learning can be observed in performance adjustments in response to varying proportions of easy to hard trials over blocks of trials on classic control tasks. Known as the list-wide proportion congruent (LWPC) effect, increased difficulty is met with enhanced attentional control. Recent research has shown that motivational manipulations may enhance the LWPC effect, but the underlying mechanisms are not yet understood. We manipulated Stroop proportion congruency over blocks of trials and after each trial, provided participants with either performance-contingent feedback (“correct/incorrect”) or non-contingent feedback (“response logged”) above trial-unique, task-irrelevant images (reinforcement events). The LWPC task was followed by a surprise recognition memory task, which allowed us to test whether attention to feedback (incidental memory for the images) varies as a function of proportion congruency, time, performance-contingency, and individual differences. We replicated a robust LWPC effect in a large sample (N = 402), but observed no differences in behavior between feedback groups. Importantly, the memory data revealed better encoding of feedback images from context-defining trials (e.g., congruent trials in a mostly congruent block), especially early in a new context, and in congruent conditions. Individual differences in reward and punishment sensitivity were not strongly associated with control-learning effects. These results suggest that statistical learning of contextual demand may have a larger impact on control-learning than individual differences in motivation.

Keywords: cognitive control, memory, attention, motivation, reward

Introduction

Whether driving during heavy traffic or attending to difficult classroom lectures, people often need to engage cognitive control, exploiting their current context to adjust their processing strategies in line with internal goals. For example, people might approach a new situation with a heightened sense of attention, because similar environments have proven difficult in the past. This phenomenon is commonly described as control-learning, whereby previous experience (memory) guides our control strategies, like the level of attentional selectivity with which we approach a task (for reviews, see Braem et al., 2019; Bugg, 2017; Bugg & Crump, 2012; Chiu & Egner, 2019; Egner, 2014). Control-learning processes are presently not well understood, however, particularly with regard to their interaction with motivation. The current study therefore aimed to elucidate some key determinants of control-learning, including how (sensitivity to) reinforcement impacts that process.

Learning-Guided Conflict-Control

Control-learning is typically assessed by manipulating the proportion of easy to hard trials on classic attention tasks, such as the Stroop task (Stroop, 1935). In this conflict-control paradigm, participants identify the printed color of color-words (the target), while trying to ignore the meaning of those words (the distracter), and they usually respond more slowly and less accurately when the printed color is incongruent with the semantic meaning of the color-word (hard trials, e.g., GREEN printed in red) than when the color is congruent (easy trials, e.g., GREEN printed in green). Known as the congruency effect, this decrement in performance is thought to reflect the conflict between the instructed goal of categorizing the color and the overlearned, prepotent response of reading the color-word, which needs to be resolved via cognitive control. The conflict-monitoring theory (Botvinick et al., 2001) suggests that the cognitive system monitors conflict and triggers changes in the recruitment of control such that more conflict (e.g., an incongruent trial) recruits more control, and a conflict-triggered up-regulation of control results in a smaller congruency effect (e.g., on subsequent trials).

To assess adaptation of control in response to greater conflict, researchers have thus used proportion congruent (PC) manipulations (Bugg, 2017), whereby the incidence of congruent to incongruent trials is varied as a function of task context. The canonical finding is that mean congruency effects are smaller in contexts where conflict is more frequent, suggesting that participants learn the contextual probability of encountering conflict and adjust their level of control accordingly. For example, item-specific proportion congruent (ISPC) paradigms involve the association of incongruent and congruent distracter frequency with a particular target (e.g., a specific ink color in the Stroop task), such that the target becomes a cue for the recruitment of cognitive control (Bugg et al., 2011). Because participants in this manipulation do not know in advance which stimulus will be shown on a given trial and therefore cannot anticipate upcoming task demand, the ISPC is thought to reflect “reactive control”, i.e., control recruited in the moment on a trial-by-trial basis (Braver, 2012; Bugg, 2017).

In contrast to the ISPC, list-wide proportion congruent (LWPC) paradigms involve the association of incongruent and congruent trial frequency with blocks (or lists) of trials, so that task demand is temporally predictable. This may lead to the recruitment of “global” or “proactive control,” i.e., control recruited in anticipation of upcoming trials. Of note, in order to separate out the effects of list-wide control demand from lower-level effects of frequency-based learning (i.e., faster responses to more frequently encountered stimuli), LWPC tasks are ideally constructed by combining a set of “inducer items” that are heavily frequency-biased in their proportion of congruency and create the current context (either mostly congruent or mostly incongruent) with a set of “diagnostic items” that are presented equally often with congruent and incongruent distracters regardless of context (Braem et al., 2019; Bugg & Chanani, 2011). A modulation of congruency effects by list-wide context in these unbiased items is taken to reflect a generalization of learning of context-appropriate control settings from the biased items to the unbiased ones, a “pure” signature of list-wide control adjustments.

While there is a large literature documenting different types of learning-guided control, especially in the domain of conflict-control, the nature of the underlying learning processes is not yet well understood. Our main question concerned the role of reinforcement, here in the guise of either performance-contingent or non-contingent feedback, in driving control-learning.

The Impact of Reinforcement on Control-Learning

Current theories suggest that one core mechanism for contextually appropriate recruitment of control is based on the formation of bindings or associations between co-occurring perceptual stimulus features, motor responses, and attentional control states, as well as temporal frames, into “episodic event files” (Egner, 2014), and that re-occurring features lead to the retrieval of those files, including the associated control states (Abrahamse et al., 2016; Egner, 2014). This framework, based on associative learning principles, predicts that control-learning should be context-specific, primarily implicit, and sensitive to reinforcement. However, how precisely reinforcement impacts control-learning remains unclear.

Many studies investigating motivation-cognition interactions (for reviews, see Botvinick & Braver, 2015; Chiew & Braver, 2011; Yee & Braver, 2018) have found differences in proactive compared to reactive control recruitment in relation to incentives (e.g., Chiew & Braver, 2013; Fröber & Dreisbach, 2014, 2016; Qiao et al., 2018). Specifically, with explicitly instructed control tasks (e.g., the AX-CPT), researchers have shown that reward boosts the recruitment of proactive control and has little or inconclusive effects on reactive control. In the domain of conflict-control, research has indicated that incentivizing task performance with extrinsic reward (i.e., money, points) can enhance the recruitment of control when task timing and parameters allow participants to use the cue information (Bugg et al., 2015; Chiew & Braver, 2016; Kang et al., 2017; Kostandyan et al., 2019; Krebs et al., 2010; Soutschek et al., 2014, 2015; Veling & Aarts, 2010). Yet neither of these literatures have examined whether reinforcement impacts the learning and generalization of reactive and proactive control-demand associations, or whether its’ impact depends on the type of reinforcer.

To address this question, Bejjani and colleagues (2020) manipulated whether participants received trial-by-trial performance feedback (correct/incorrect) during the LWPC and ISPC paradigms. Performance feedback provides valuable information about goal attainment and can act as an intrinsic reward or punishment, boost motivation, and enhance learning (Bejjani et al., 2019; Peters & Crone, 2017; Tricomi & DePasque, 2016). The researchers predicted that if control-demand were learned via associative learning mechanisms and sensitive to reward, in the form of reinforcement from performance feedback, then feedback would result in larger control-learning effects. They found that performance feedback boosted the learned recruitment of proactive, anticipatory control (i.e., the LWPC effect) but had little impact on the recruitment of in-the-moment, reactive control (the ISPC effect). The exact mechanism through which performance feedback boosted the recruitment of proactive control, however, remains unclear. This is the primary question we sought to answer in the current study: how is reinforcement derived from performance feedback processed in the LWPC paradigm? We approached this question by testing how much participants attend to trial-by-trial feedback in this paradigm, and whether attention to feedback varies as a function of the performance-contingency of the feedback, proportion congruent (PC) context, time, and individual differences in reward and punishment sensitivity.

In order to shed new light on how performance feedback is processed during learning of control strategies in the LWPC protocol, we borrowed a design feature from recent studies of reinforcement learning, namely, the use of trial-unique feedback images, the incidental encoding of which is thought to reveal participants’ attention to reinforcement (e.g., Davidow et al., 2016; Gerraty et al., 2018; Höltje & Mecklinger, 2018, 2020). For example, Davidow and colleagues (2016) had participants learn to associate particular stimuli with their respective motor responses by providing task-relevant word and task-irrelevant trial-unique image feedback. The researchers later tested incidental memory for the feedback images as an implicit measure of how well participants attended (or were sensitive) to the reinforcement of the stimulus-response associations. The authors were thus able to quantify incremental learning of stimulus-response associations via trial-by-trial reinforcement, as well as episodic memory for reinforcement events. We here adopted this approach to the study of control-learning in the LWPC paradigm. Specifically, we combined the performance feedback LWPC paradigm from Bejjani and colleagues (2020) with trial-unique feedback images and a surprise recognition memory test, and analyzed incidental encoding as a proxy measure of reinforcement sensitivity. This design granted us a novel lens on whether and how attention to reinforcement events in the learning process impacts the recruitment of control.

In terms of reinforcement (feedback) events, we distinguished between two classes: performance-contingent feedback (the words “correct” of “incorrect” displayed above a trial-unique image) and non-contingent feedback (the words “response logged” displayed above a trial-unique image). Note that, unlike in tasks where participants need to use feedback to discover the correct stimulus-response mappings through trial-and-error, in typical LWPC tasks, participants are explicitly instructed what those mappings are and rehearse them prior to the main task. Therefore, participants likely do not need to process performance feedback in order to gain information about the correct stimulus-response mappings. Instead, feedback is here expected to provide more generic reinforcement, in that it represents an action effect (giving a response produces a stimulus on screen) and provides confirmation of a response being registered. Therefore, we consider both performance-contingent and non-contingent feedback as reinforcement events. However, we expected the performance-contingent feedback to produce a stronger motivational impact than the non-contingent feedback, since it supplied explicitly positive (correct) or negative (incorrect) information about the response. Thus, there are two types of reinforcement within this task: the Stroop stimuli creating and reinforcing the expectations that participants formed about the task statistics (relevant to both performance contingent and non-contingent groups) and the type of feedback itself reinforcing participant motivation (correct versus response logged) and subsequent learning.

A number of plausible hypotheses can be generated concerning the pattern of attention paid to feedback events in the LWPC protocol. We here highlight two of them, but additional ones are addressed in the General Discussion. First, it is commonly thought that control-learning in conflict tasks involves the linking of stimuli, context, and an appropriate level of attentional focus (Egner, 2014; Abrahamse et al., 2016). For example, in the case of a mostly incongruent block of trials, both individual stimuli that are frequently paired with incongruent distracters as well as the overall temporal context would become associated with a high selectivity of attention, because a high attentional focus is required for exclusively processing the task-relevant stimulus feature to select the correct response. Thus, one can conceive of control-learning as a case of statistical learning, where participants (likely implicitly) detect that some trial types are more frequent than others, and build up an internal model (or expectation) of likely forthcoming events (e.g., Perruchet & Pacton, 2006). Prior research in that literature has shown that contextually probable events both guide (e.g., Chun & Jiang, 1999) and attract attention (Zhao et al., 2013), possibly because people are biased towards seeking confirmatory evidence in building their internal model of the task structure (e.g., Klayman, 1995). In line with this confirmation bias idea, it has in fact been shown that feedback confirming current expectation has an irrationally stronger impact on reinforcement learning than feedback that disconfirms predictions (Palminteri et al., 2017). In other words, people are driven to learn task statistics, and evidence that conforms to expectations has a reinforcing effect. Note that this suggests that, in addition to potentially deriving reinforcement from performance feedback, encountering a contextually probable (expected) stimulus may be reinforcing in and of itself, a notion we here refer to as “statistical reinforcement”. Applying these insights from the statistical learning literature to the LWPC paradigm thus suggests that participants would preferably attend to feedback for contextually probable (or context-defining) trials, that is, congruent trials in mostly congruent blocks and incongruent trials in mostly incongruent blocks. This type of statistical reinforcement is thus agnostic to the feedback group (contingent versus noncontingent), and we explicitly assume that reinforcement derived from confirmed expectations will cause participants to attend more to the feedback images for context-defining trials, essentially transferring the reinforcement from an expected task stimulus to the subsequent feedback image.

Second, inspired by the idea that adaptation to conflict may be a form of avoidance learning (Botvinick, 2007), a substantial research literature has documented that conflict (in incongruent trials) is in fact perceived as aversive or costly (Cavanagh et al., 2014; Dignath et al., 2020; Dreisbach & Fischer, 2012, 2015), and that adaptation of control in response to conflict could serve the purpose of reducing negative affect (Dreisbach, Fröber, et al., 2018; Dreisbach, Reindl, et al., 2018; Schmidts et al., 2020; Torres-Quesada et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2019). Accordingly, responding successfully (correctly) to incongruent trials has been associated with more positive affect than correctly responding to congruent trials (Schouppe et al., 2015; see also Ivanchei et al., 2019). Considering this literature, motivation could boost learning, increasing a sense of achievement upon performing well on incongruent trials (cf. Schouppe et al., 2015). This would result in increased motivation in mostly incongruent blocks (thus ramping up control and reducing congruency effects) relative to mostly congruent blocks (where, under low motivation, attentional focus would be expected to be particularly loose, and congruency effects would be expected to be large). As the expression of this type of motivational mechanism may depend on individual differences in people’s sensitivity to reward (Braem et al., 2012) or punishment (Braem et al., 2013), we also acquired self-reported trait measures of reward and punishment sensitivity to relate to performance. These individual differences could interact with group-level motivational manipulations, such as whether participants receive performance-contingent feedback (more motivationally potent/rewarding) or non-contingent feedback (less motivationally potent). For instance, individuals high in reward sensitivity would presumably be more sensitive to performance-contingent feedback, causing greater levels of error monitoring and performance-related adjustments.

The Current Study

To evaluate these possibilities in the present study, participants first learned to associate particular color-words in the Stroop task with different levels of control-demand, accompanied by trial-by-trial feedback comprised of task-relevant words that were either performance-contingent (“correct/incorrect/respond faster”) or non-contingent (“response logged/respond faster”), and task-irrelevant trial-unique images. Some colors were more often presented with either incongruent or congruent distracter words (“biased” or “inducer” items), which created an overall bias for blocks of trials to be mostly congruent or incongruent contexts, while others were presented equally often with congruent and incongruent distracters (“unbiased” or “diagnostic” items). Next participants completed a filler phase, which provided a delay between encoding and retrieval. Here, we assessed participants’ trait reward and punishment sensitivity with the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) scale and the Behavioral Activation System (BAS) reward responsiveness subscale (Carver & White, 1994). Finally, participants performed a surprise recognition memory test, trying to discriminate the images they had seen as feedback during the learning phase from a set of comparable, new images.

We expected to replicate the basic LWPC effect (in both biased and unbiased items), and to observe a common modulation of that effect by block order (cf. Abrahamse et al., 2013; Bejjani, Tan, & Egner, 2020). One fundamental assumption of the LWPC paradigm we deployed is that learning a list-wide context from the biased (inducer) items drives the LWPC effect observed in unbiased (diagnostic) items (cf. ISPC in Bejjani, Tan, et al., 2020; Bugg & Dey, 2018). We thus assessed correlations between participant responses to each trial type within a proportion congruent (PC) context and LWPC effects in biased and unbiased items across individuals in a large sample. If learning from inducer items drives control for diagnostic items, we should find a positive correlation between these responses and effects. In order to test this individual difference hypothesis with reasonable power, we recruited a large sample (>400 participants).

Importantly, we additionally tested the following novel predictions: First, based on the statistical learning perspective outlined above, one would anticipate better memory for feedback events for the context-defining items (e.g., congruent item feedback in a mostly-congruent context). Note that given the self-reinforcing nature of statistical learning discussed above, this pattern may possibly be observed irrespective of the performance-contingency of the feedback. Second, updating of context-control associations in the LWPC protocol should be particularly relevant when a context is new or changing. Accordingly, we hypothesized better memory for reinforcement events at the beginning of a new context (at the beginning of the task and after a change in proportion congruency). Third, as outlined above, a motivation-based boost to control recruitment would suggest that feedback would be better attended in the mostly incongruent blocks (and generally, following incongruent more than following congruent trials). Finally, motivation-cognition interactions would also suggest that inter-individual differences in reward and punishment sensitivity should be associated with the impact of performance-contingent feedback on the LWPC, leading, for instance, to the prediction that individuals with higher reward sensitivity would show larger LWPC effects, and particularly so under conditions of performance-contingent feedback.

Method

Sample Size

Two factors determined the sample size of this study: the number of participants needed to observe a reliable control-learning effect, and the number of participants needed for a (possibly weak) cross-subject correlation to stabilize. Bejjani and colleagues (2020) reported ηp2 = 0.13 (RT) and 0.23 (inverse efficiency, i.e., corrected RT divided by proportion correct for each condition, Townsend & Ashby, 1983) for the proportion congruency context by congruency interaction for biased items and ηp2 = 0.05 (RT) and 0.13 (inverse efficiency) for unbiased items within the combined Experiment 2 feedback group (N = 90). With a power of 0.8, Type I error of 0.05 and similar experimental procedure, and using the most conservative effect size estimates, we would thus need to recruit between 56 and 153 participants for detecting control-learning effects.

No prior studies have investigated the relationship between individual differences in control-learning and reward responsiveness in a systematic manner. We assumed that the correlation in the population was a conservative r = 0.1, and we aimed for an 80% confidence level and small to medium corridor of stability for the correlation (cf. Schönbrodt & Perugini, 2013). These assumptions suggested that we needed to recruit between 110 and 252 participants.

Our target sample size was thus about two hundred participants.

Participants

Between February and March 2020, 124 Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) workers consented to participate for $5.85 ($0.13/minute), while 134 undergraduate (SONA) students consented to participate for one course credit. 36 MTurk workers were excluded for poor accuracy (<70%) in the learning phase (range [0.25, 68.29]), while 20 undergraduate students were similarly excluded (range [37.04, 69.68]). This resulted in a performance-contingent feedback group sample size of 88 MTurk workers (mean age = 37.85 ± 10.901) and 114 undergraduate students (mean age = 19.24 ± 1.04) for a total N = 202; see Supplementary Table 1 for additional demographics.

We collected data from the performance non-contingent feedback group during September and October 2020. We excluded 124 MTurk workers (range [4.40, 69.91])2 and 45 undergraduate students (range [5.79, 69.44]) for poor accuracy (consented MTurk: 202; undergraduate: 167). Our final non-contingent feedback group sample size was 78 MTurk workers (mean age = 36.27 ± 9.98) and 122 undergraduate students (mean age = 18.97 ± 1.03) for a total N = 200; see Supplementary Table 2 for additional demographics.

Recruiting an approximately equal amount (N ~ 100) of MTurk workers and undergraduate students was largely a matter of convenience, since both populations performed the study online in a browser and at their own pace, and we did not expect any differences in observed behavior. Entering participant population as a factor of no interest into our analyses revealed no interactions with any effects of interest, so we did not include that factor in the analyses reported below. Within the performance-contingent feedback group, one undergraduate student experienced an error during the recording of the BIS-BAS data while memory data for another student was not recorded, so these two participants were excluded from the relevant analyses.

Stimuli

As in previous studies (Bejjani et al., 2020; Bejjani & Egner, 2019), we obtained 544 feedback images from an online database (http://cabezalab.org/cabezalabobjects/) and Google searches of images with a license for noncommercial reuse with modification. All images were cropped to 500 × 300 pixels with a white background.

Procedure

The experimental procedure (Figure 1) consisted of consecutive learning, filler, and memory phases (cf. Bejjani et al., 2020; Davidow et al., 2016). The first block of the Learning Phase was a practice block to ensure that participants learned the stimulus-response mappings for the 6 color-words (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and purple). Here, all 120 trials were congruent. Participants categorized the color in which the color-words were printed by pressing the z, x, and c keys with their left ring, middle, and index fingers and the b, n, and m keys with their right index, middle, and ring fingers. Performance feedback (correct, incorrect; response time-out: respond faster) lasted 500 ms and was followed by a 500 ms blank intertrial interval. The feedback and color-words were presented in the center of the screen. Participants generally performed well on the practice block, with an average accuracy of 75%, and were not required to achieve a specific accuracy criterion before advancing in the study because of concerns about differences in time on task. Nonetheless, participants were reminded of the stimulus-response mappings during every break between task blocks, and these mappings were constant, with only four of six mappings relevant per block after the practice block.

Figure 1. Experiment design.

In the initial Learning Phase (A), participants performed a color-word Stroop task, which involved a list-wide proportion congruent (PC) manipulation. Participants received trial-unique picture feedback placed below either verbal performance-contingent feedback (correct/incorrect/respond faster) or performance non-contingent feedback (response logged/respond faster). Next, they completed a Filler Phase (B), which was designed as a delay between encoding and retrieval, and involved demographic questions, questions probing their explicit understanding of the PC manipulation, and the BIS-BAS questionnaire (Carver & White, 1994). Finally, in the Memory Phase (C), participants identified whether images were new (never seen) or old (previously seen as feedback in the Learning Phase).

On the 108 trials in each of the main four blocks of the Learning Phase (Figure 1a), participants had 1000 ms to respond to the color-word, which was directly followed by the feedback screen, also lasting 1000 ms. For the performance-contingent feedback group, feedback in the main blocks consisted of the same words from the practice block (correct, incorrect, respond faster), while for the non-contingent feedback group, the words were “response logged” and “respond faster.” Across both groups, the words were now accompanied by task-irrelevant, trial-unique images (see Fig. 1a). Word feedback was presented 5 pixels above the center of the screen, where the images were shown. This stimulus arrangement was intended to ensure that participants processed both the relevant feedback and irrelevant images while not obscuring one with the other. Participants were told that the color in which color-words were printed may no longer match the meaning of the color-words and that they would now be presented with object images as part of their feedback.

Critically, the Learning Phase involved a proportion congruent (PC) manipulation (Table 1): four color-words were more often congruent (PC-90) or incongruent (PC-10) (“biased, inducer items”), while two color-words were not biased at the stimulus level (PC-50) and could only be influenced by the context in which they were presented (“unbiased, diagnostic items”). Specifically, each block included 61 trials of the frequent type and 7 trials of the rare type for the biased items and 20 of each trial type for the unbiased items. The PC-90 and PC-10 items thus created an overall list-wide bias of PC-75/25, whereby half of the blocks of trials were mostly congruent (MC) and the other half mostly incongruent (MIC). Note that the PC-90 and PC-10 items indexed a combination of control-learning and stimulus-response contingency learning confounds, because they occur more frequently for each of their respective trial types and are biased by the context in which they are presented. However, the PC-50 items provided a pure index of control-learning (cf. Braem et al., 2019), because they occurred with the same frequency in the MC and MIC contexts and had no item-specific biases. Each PC-90 item was only incongruent with the other PC-90 item (e.g., if red and blue were PC-90 items, then red would only be shown in blue incongruent ink). The same was true for the PC-50 and PC-10 items.

Table 1.

Design of the Proportion Congruent Manipulation.

| MIC context | MC context | |

|---|---|---|

| Biased items | (e.g., red, yellow) | (e.g., orange, blue) |

| Congruent | 7 (14) | 61 (122) |

| Incongruent | 61 (122) | 7 (14) |

| Unbiased Items | (e.g., green, purple) | |

| Congruent | 20 (40) | 20 (40) |

| Incongruent | 20 (40) | 20 (40) |

Within the Learning Phase, we randomized color-word assignment to the proportion congruent contexts and ensured that at least one color-word of each PC probability was mapped to each hand (e.g., z, x, and c represented either PC 90, 50, or 10). We also counterbalanced for block order, which is important in list-wide PC manipulations, since extended timeframes of similar control-demand levels produce canonical control adaptations more readily than shorter blocks of intermixed control-demand (cf. Abrahamse et al., 2013). Our two block orders were thus MC-MC-MIC-MIC and MIC-MIC-MC-MC, and block order was entered as a between-participants factor into the analyses.

The Learning Phase was followed by the Filler Phase (Figure 1b), which provided a delay between encoding and the surprise retrieval phase. Here, participants filled out a basic demographics questionnaire and answered questions assessing their explicit awareness of the PC manipulation (see Supplementary Text for details and analysis). Finally, participants filled out the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) – Behavioral Activation System (BAS) (BIS-BAS) questionnaire (Carver & White, 1994), because we were interested in the BIS scale and BAS reward responsiveness subscale as a measure of trait reward and punishment sensitivity. Participants were informed that the button to submit the BIS-BAS would appear after ~4 minutes, ensuring that at a minimum, the self-paced Filler Phase would last 4 minutes.

Finally, in the Memory Phase (Figure 1c), participants performed a surprise recognition memory test, where the 432 images from the Learning Phase were randomly intermixed with 108 (i.e., 20%) new, lure images. Note that the use of less than 50% lure images is quite common in (especially neuroimaging) memory studies (Cansino et al., 2002; Gonsalves et al., 2004; Gottlieb et al., 2010; Ritchey et al., 2008; Uncapher et al., 2006). While this smaller percentage of new items can affect participants’ response bias (inducing a general tendency for more “old” responses), it would not do so differentially between our conditions of interest, and would not affect memory strength (d prime). On each Memory Phase trial, participants had 2000 ms to indicate whether the image was Old (previously seen as a feedback image in the Learning Phase) or New (not seen before), via the a/A and l/L keys and their left and right index fingers. Participants received time-out feedback (respond faster) if they did not respond within the 2s deadline. We considered incidental memory for the task-irrelevant feedback images as a measure of how much attention participants had paid to these feedback images during the Learning Phase or – in other words – how sensitive they were to reinforcement events.

Data Analysis

We analyzed accuracy rates and reaction time (RT) Learning Phase data for correct trials in the main task blocks that were not a direct stimulus repetition from the previous trial or excessively fast (< 200 ms) or slow (feedback time-out: > 1000 ms).

To establish whether the LWPC manipulation successfully induced a global adaptation in cognitive control, we ran a 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 repeated-measures ANOVA for unbiased (PC-50) items, with proportion congruent (mostly incongruent/mostly congruent) and current trial congruency (congruent/incongruent) as within-participants factors and block order (MC-MC-MIC-MIC/MIC-MIC-MC-MC) and feedback (performance contingent/non-contingent feedback) as between-participants factors. We report the same analyses for the biased (PC-90/10) items in the Supplementary Text. Simple main effects were also run to establish which level of the main effect was significant within the interaction.

Block order was considered in the analysis as another contextual factor that can modulate control-learning. For example, Abrahamse and colleagues (2013) examined how shifting from blocks of trials with different proportion congruencies impacts the learned control states recruited and the congruency effects observed. When participants shifted from a block with more control-demand (e.g., more conflict) to one with less control-demand (e.g., less conflict), the difference in their congruency effect across blocks was much smaller than when they switched from less to more control-demand, suggesting that the particular history of context (blocks of trials) influences current and subsequent recruitment of control.

Explicit awareness of the PC manipulation was assessed via t-tests performed on the Filler Phase data (see Supplementary Text). Additionally, to assess whether trait reward or punishment sensitivity impacted control-learning, we ran correlations between scores derived from the BAS reward responsiveness subscale (or the BIS scale) and behavioral measures from the Learning Phase. Trait reward and punishment sensitivity were also added as separate covariates to the Learning Phase ANOVA. Whenever possible, correlations for difference scores were corrected by dividing the difference score by the overall mean score on the behavioral measure (e.g., the RT interaction metric divided by overall RT for each participant) (see e.g., Hedge et al., 2018; Rouder & Haaf, 2019 for a discussion on the reliability of difference scores).

Finally, Memory Phase data were analyzed for trials that were not excessively fast (< 200 ms) or slow (feedback time-out: > 2000 ms). We calculated d-prime (z(hit rate) – z(false alarm rate)), replacing near-zero false alarm rates with 0.5/N and near-one hit rates with (N-0.5)/N (Macmillan & Kaplan, 1985), to assess average memory within the task. To assess the relative contributions of motivation and statistical learning, we ran a repeated-measures ANOVA on Hit rates with the same factors from the Learning Phase, but further excluded incorrect Learning Phase trials (which included responses that were too slow), since they could confound memory results, as well as excessively fast Learning Phase responses (i.e., < 200 ms), since these would not represent typical learning trials. Participants who had fewer than ten trials per cell were eliminated from the analysis.

In addition to the above frequentist statistics, we report inclusion Bayes Factors calculated using the R packages, bayestestR and BayesFactor, for the repeated-measures ANOVAs. Inclusion Bayes Factors (BF) answer the question, “Are the observed data more probable under models with a specific predictor than they are under models without that specific predictor?” For instance, an inclusion BF of 5 indicates that a model with that predictor is five times more likely than a model without that predictor. We calculate the inclusion BFs for matched models: model comparison is thus restricted to models without interactions that include the term of interest and for interactions specifically, averaging is restricted to models that include the main effect terms that comprise the interaction term. We chose matched model inclusion BFs to accurately account for the evidence of the interaction terms.

All materials (experimental and analysis code and data) are available online at https://github.com/christinabejjani/LWPCtufb.

Results

Robust LWPC Effects Within and Between Participants

The main analyses of interest for the Learning Phase concerned RT and accuracy rates for the unbiased, diagnostic items, in order to establish successful list-wide control-learning. A congruency × PC interaction for these items, whereby the congruency effect is reduced for low compared to high PC blocks (the LWPC effect), would reflect “pure” control-learning that is not confounded with S-R learning effects. For completeness, we report analyses of the biased items in the Supplementary Text (see Supplementary Tables 3–6 for mean behavioral data).

Reaction Time.

We observed significant main effects of congruency (F(1,398) = 1199.59, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.75, inclusion BF = 4.37 × 10211) and PC context (F(1,398) = 24.18, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06, inclusion BF = 1.52 × 104), whereby participants responded slower to incongruent (725 ms) than congruent (667 ms) trials and in the PC-75 (697 ms) than PC-25 (691 ms) context. Importantly, these two factors interacted (F(1,398) = 24.63, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06, inclusion BF = 47.94): the congruency effect was reduced in the PC-25 (54 ms) compared to the PC-75 (65 ms) context, which was driven primarily by speeded responses to incongruent (F(1) = 41.24, p < 0.001) rather than congruent trials (F(1) = 1.80, p = 0.181). Consistent with Abrahamse and colleagues (2013) and Bejjani and colleagues (2020), the LWPC effect was further modulated by block order (Figure 2; F(1,398) = 18.43, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04, inclusion BF = 14.25): the LWPC effect was larger when participants experienced the mostly congruent context first (21 ms) than the mostly incongruent context first (1 ms).

Figure 2. Learning Phase results for unbiased (PC-50) items.

Mean RT (ms) and error rate (%) congruency effects (Incongruent – Congruent) are shown as a function of proportion congruent context (PC-25/PC-75) and block order (A: MIC-MIC-MC-MC/B: MC-MC-MIC-MIC). On the left of each plot, light grey lines connect individual mean congruency effects for participants across PC contexts (PC-25 (left) connected to PC-75 (right), while the dark grey line connects the mean (±SEM) across PC contexts. Positive line slopes indicate the LWPC. The boxplots (left: PC-25, right: PC-75) show a box for the first through third quartiles of the data, a thick black line inside the box to represent the median (of participant mean data), and thin black lines extending from the boxes to indicate the range of non-outlier data. Next to the box plots are violin plots (orange: PC-25; green: PC-75) that represent the respective distributions of the congruency effect data.

We observed an additional modulation of the PC main effect by block order (PC × block order: F(1,398) = 90.95, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.19, inclusion BF = 1.70 × 1020), whereby the difference between PC contexts was larger when participants experienced the mostly congruent context first (−20 ms) than the mostly incongruent context (7 ms). No other effects were significant (F < 3.67, BFs < 1; feedback × PC × congruency: F(1,398) = 0.10, p = 0.747, ηp2 < 0.001, inclusion BF = 0.18).

Finally, note that the fact that we counterbalanced the order of PC conditions across participants also allowed us to assess the effect of PC between participants and in isolation from the effect of block order. This could be done by analyzing only the first two blocks per participant and treating the order factor as a between-participants PC factor, whereby half of the participants contribute their mostly congruent first two blocks, and the other half contribute their mostly incongruent first two blocks (PC-75 from Figure 2B vs. PC-25 from Figure 2A). This approach thus focuses on the early task phase(s), where presumably most of the initial learning from feedback takes place (see Incidental Memory results, below).

Via this analytic approach, we observed a significant main effect of congruency (F(1,398) = 916.34, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.70, inclusion BF = 4.67 × 1099) and a significant main effect of block order (i.e., between-participants PC context, F(1,398) = 9.73, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.02, inclusion BF = 15.01) that interacted, demonstrating a between-participants LWPC (compare PC-25 from Figure 2A to PC-75 from 2B; F(1,398) = 16.50, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04, inclusion BF = 302.03). Participants showed an expected smaller congruency effect when they experienced the mostly incongruent context (55 ms) relative to the mostly congruent context (73 ms), driven primarily by speeded responses to incongruent (F(1) = 19.60, p < 0.001) rather than congruent trials (F(1) = 1.86, p = 0.173). Finally, participants in the non-contingent feedback condition (706 ms) responded more slowly than participants in the performance-contingent feedback condition (695 ms) (F(1,398) = 5.50, p = 0.020, ηp2 = 0.01, inclusion BF = 2.29; all other effects, F < 2.19, BFs < 1; block order × congruency × feedback: F(1,398) = 0.42, p = 0.519, ηp2 = 0.001, inclusion BF = 0.17).

Accuracy.

We observed a significant main effect of congruency (F(1,398) = 442.00, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.53, inclusion BF = 2.18 × 1091) and of PC context (F(1,398) = 11.42, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03, inclusion BF = 14.84): participants were less accurate on incongruent (74.16%) than congruent (85.15%) trials and in the PC-75 (78.77%) than PC-25 (80.53%) context. Importantly, these two factors interacted (F(1,398) = 10.67, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03, inclusion BF = 1.20), as congruency effects were smaller within the PC-25 (−9.84%) compared to PC-75 (−12.13%) context, driven primarily by increased accuracy on incongruent trials (F(1) = 16.24, p < 0.001) rather than on congruent trials (F(1) = 1.40, p = 0.238). Notably, this interaction had larger evidence for a further modulation by block order (Figure 2; F(1,398) = 96.80, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.20, inclusion BF = 2.03 × 1010), as the LWPC effect was larger when participants first experienced the mostly congruent (−9.13%) vs. mostly incongruent context (4.56%).

We again observed modulation of the PC main effect by block order (F(1,398) = 162.97, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.29, inclusion BF = 4.28 × 1036): the difference between PC contexts was larger for participants who experienced the mostly congruent context first (−8.37%) than for those who experienced the mostly incongruent context first (4.86%). The same pattern was obtained for congruency effects, which were also smaller for participants who experienced the mostly incongruent context first (−9.19%) than for those who experienced the mostly congruent context first (−12.79%) (F(1,398) = 11.47, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03, inclusion BF = 58.3). Participants in the non-contingent feedback group also displayed larger congruency effects (−12.41%) than participants in the performance-contingent feedback group (−9.57%) (F(1,398) = 7.00, p = 0.008, ηp2 = 0.02, inclusion BF = 15.49). Moreover, participants who experienced the mostly incongruent context first (80.86%) were more accurate than participants who experienced the mostly congruent context first (78.45%) (F(1,398) = 6.69, p = 0.010, ηp2 = 0.02, inclusion BF = 2.77). No other effects were significant (F < 2.02, BFs < 0.19; feedback × PC × congruency: F(1,398) = 2.01, p = 0.157, ηp2 = 0.01, inclusion BF = 0.18).

Finally, when we removed the effect of context order by analyzing only the first two blocks, treating the block order factor as a between-participants PC factor, we found a significant congruency effect (F(1,398) = 430.13, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.52, inclusion BF = 1.05 × 1060) and a significant main effect of block order (between-participants PC) (F(1,398) = 12.74, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03, inclusion BF = 56.11) that interacted (i.e., between-participants LWPC) (compare PC-25 from Figure 2A to PC-75 from 2B; F(1,398) = 17.50, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04, inclusion BF = 465.51). Participants in the mostly incongruent context showed smaller congruency effects (−11.47%) than participants in the mostly congruent (−17.35%) context, driven primarily by increased accuracy on incongruent (F(1) = 21.31, p < 0.001) rather than on congruent trials (F(1) = 1.16, p = 0.281). No other effects were significant (F < 3.71, BFs < 0.68; block order × congruency × feedback: F(1,398) = 1.21, p = 0.273, ηp2 = 0.003, inclusion BF = 0.23).

In sum, we found that the PC manipulation provided by the biased items was effective (see Supplementary Text for additional analyses on biased items), such that the Learning Phase elicited pure control-learning for both feedback groups, as indexed by a frequency unbiased LWPC effect, across a large sample (N = 402). Across RT and accuracy, we showed a robust within-participants LWPC effect (though sometimes strongly moderated by context order) when analyzing the whole experiment, and a robust between-participants LWPC effect (in the absence of order effects) when only analyzing the first two blocks (cf. Spinelli et al., 2019). These effects were driven primarily by differences in responding to incongruent trials across PC contexts. Thus, participants recruited greater attentional focus when blocks of trials involved more incongruent trials or control-demand, and the performance-contingency of reinforcement events did not appear to boost learning, contrary to a motivational framework. Next, we sought to assess some possible determinants of this learning process.

Learning from Biased Items Predicts Effect in Unbiased Items

One key determinant of the unbiased LWPC effect should be the learning process taking place with respect to the biased items. Specifically, an underlying assumption of PC paradigms is that the biased items drive the learning, and the resultant adjustments in control are then extended to the unbiased items. Accordingly, congruency effects for biased and unbiased items should be positively correlated, but to the best of our knowledge this has not previously been assessed in the LWPC protocol (cf. Bugg & Dey, 2018; Gonthier et al., 2016). We therefore calculated correlations between congruency effects for biased and unbiased items across PC contexts (collapsed across block orders, for greater power). Of note, difference scores like congruency effects are more variable than standard behavioral metrics (Hedge et al., 2018; Rouder & Haaf, 2019), so these correlations would not be expected to be as large as those for condition-specific mean RTs.

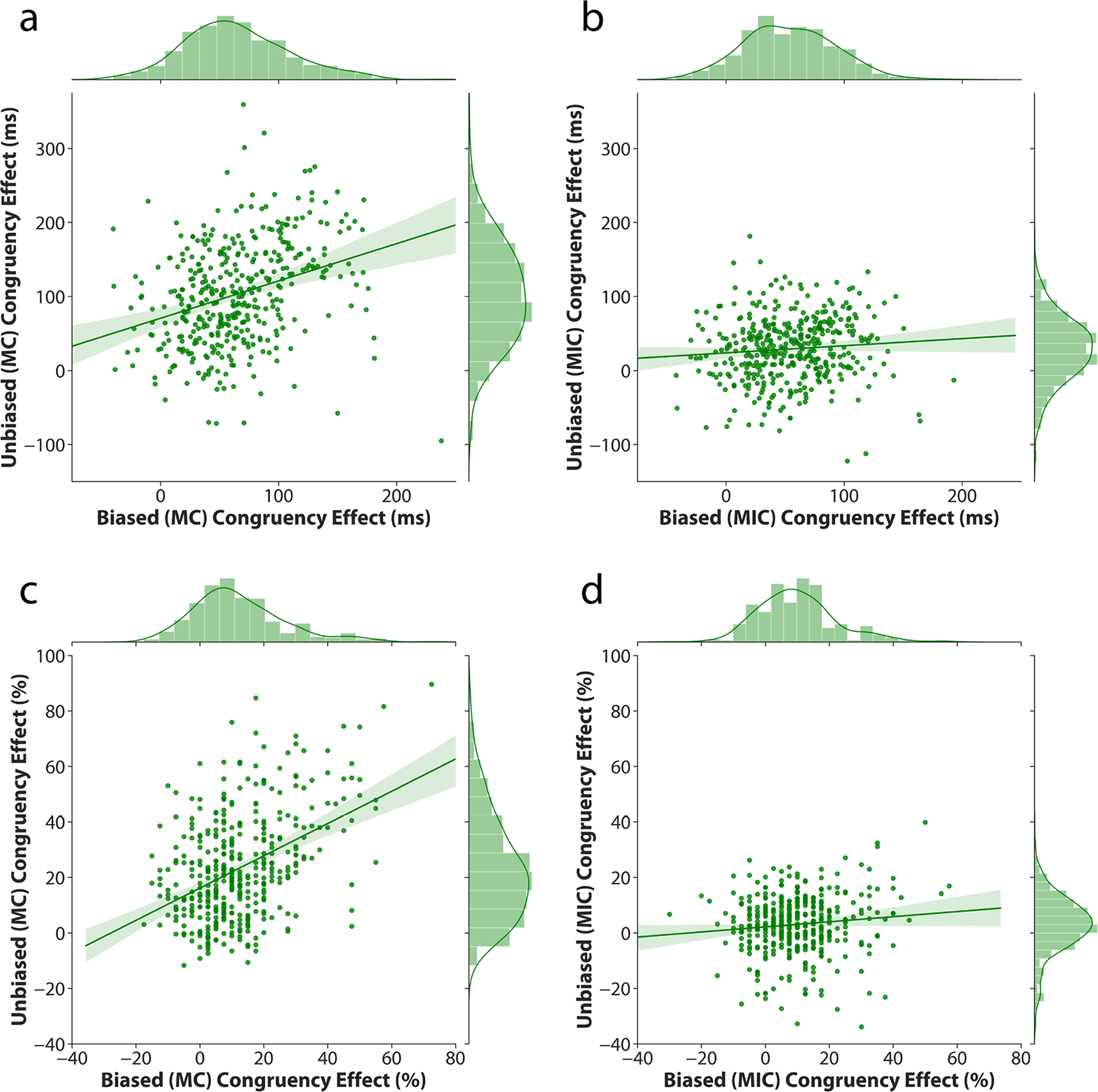

Congruency effects for biased and unbiased items were positively correlated in both contexts, though more so in the MC context (Figure 3A, RT, r(400) = 0.32, p < 0.001; corrected for overall RT: r(400) = 0.29, p < 0.001; Figure 3C, Accuracy, r(400) = 0.44, p < 0.001; corrected for overall Accuracy: r(400) = 0.47, p < 0.001) than the MIC context (Figure 3B, RT, r(400) = 0.08, p = 0.091; corrected: r(400) = 0.09, p = 0.058; Figure 3D, Accuracy, r(400) = 0.11, p = 0.030; corrected: r(400) = 0.14, p = 0.004). Notably, when we compared the correlation coefficients between the MC and MIC contexts with a Fischer’s r-to-z transformation, we found that the associations were stronger across both RT (uncorrected: z = 3.47, p < 0.001; corrected: z = 2.92, p = 0.004) and Accuracy (uncorrected: z = 5.08, p < 0.001; corrected: z = 5.10, p < 0.001) for the mostly congruent context. This may suggest a more consistent application of (low) control within the mostly congruent PC-75 context than (high control) in the mostly incongruent PC-25 context.

Figure 3.

Correlations between congruency effects (Incongruent – Congruent) for biased (PC-90/10) and unbiased (PC-50) items across the mostly congruent context (A, C) and mostly incongruent context (B, D) using RT (ms) and Error rates (%).

To examine this idea more, we ran correlations within each PC context for each trial type between responses to biased and unbiased items. Participants within the PC-75 context responded consistently across biased and unbiased items for both frequent congruent trials (RT: r(400) = 0.74, p < 0.001; Accuracy: r(400) = 0.61, p < 0.001) and rare incongruent trials (RT: r(400) = 0.63, p < 0.001; Accuracy: r(400) = 0.57, p < 0.001). The same was true of responding within the PC-25 context to frequent incongruent trials (RT: r(400) = 0.73, p < 0.001; Accuracy: r(400) = 0.59, p < 0.001) and rare congruent trials (RT: r(400) = 0.66, p < 0.001; Accuracy: r(400) = 0.38, p < 0.001). Accuracy correlations are smaller, but this is likely due to the binomial and not truly continuous distribution of accuracy as a dependent measure, which results in ceiling performance, and a select few participants driving the correlation strength. Interestingly, participants were more consistent at generalizing control from biased to unbiased items for frequent trials than rare trials (PC-75, RT: z = 2.86, p = 0.004; Accuracy: z = 0.898, p = 0.369; PC-25, RT: z = 1.83, p = 0.067; Accuracy: z = 3.90, p < 0.001), highlighting either instability in the biased items for rare items (due to trial count) or broad sensitivity to the statistical learning of the proportion manipulation. In short, these correlations suggest mostly acceptable reliability within blocks generalizing control from biased to unbiased items.

Overall, these results support the basic assumption of learning from biased items being extended to the application of control to the unbiased items.

Minimal Effect of Trait Reward Responsiveness and Punishment Sensitivity

If participants learn to recruit proactive control in the list-wide context via a motivational route, the expression of the LWPC effect across individuals should be positively associated with trait reward responsiveness and interact with feedback group. Trait reward responsiveness was assessed with the reward responsiveness subscale of the BIS-BAS (Carver & White, 1994), which participants filled out as part of the Filler Phase between the learning and memory phases. Moreover, we also ran exploratory correlations with BIS scores, since some work has suggested that individual differences in punishment sensitivity could also represent an important facet of motivation-cognition interactions (Braem et al., 2013), especially with relation to cost-benefits frameworks of control adjustments (cf. Shenhav et al., 2013).

Neither trait reward sensitivity nor punishment sensitivity were significantly associated with the RT interaction effect between PC and congruency for unbiased items (Figure 4A&C, BAS: r(399) = 0.04, p = 0.424; corrected for overall RT: r(399) = 0.04, p = 0.393; BIS: r(399) = 0.05, p = 0.288; corrected for overall RT: r(399) = 0.05, p = 0.303). Nor were these measures correlated with the Accuracy LWPC effect (Figure 4B&D, BAS: r(399) = 0.04, p = 0.458; corrected for overall Accuracy: r(399) = 0.04, p = 0.426; BIS: r(399) = 0.00, p = 0.982; corrected for overall Accuracy: r(399) = 0.00, p = 0.956).

Figure 4.

Correlations between trait/BAS reward responsiveness (A, B) and trait/BIS punishment sensitivity (C, D) and the LWPC effect for RT (A, C) and Error Rate (%) (B, D).

To explore further how trait reward or punishment sensitivity might impact conflict-control, we subsequently reran the repeated-measures ANOVAs from the Learning Phase, adding the BAS reward responsiveness and BIS punishment sensitivity scores as a covariate in separate analyses. There was no significant main effect or interactions associated with trait reward sensitivity for either RT or accuracy. With respect to trait punishment sensitivity, we found a significant but weak interaction between BIS scores and congruency (F(1,396) = 4.74, p = 0.030, ηp2 = 0.01) on RT. Participants who had higher punishment sensitivity had larger congruency effects. No other effects or interactions associated with trait punishment sensitivity were significant.

In sum, trait reward and punishment sensitivity showed mostly nonsignificant associations with performance speed and accuracy. Overall, these analyses suggest that trait reward sensitivity and punishment sensitivity may only play a very small role in determining whether an individual learns control-demand associations, which in turn can be seen as discounting a motivational basis for driving learning in the current study.

Modest Reliability of Control-Learning Measures

One possible explanation for why we did not observe stronger associations between the control-learning and reward responsiveness measures at the level of individual differences is a potential lack of internal reliability. For instance, difference scores may pose problems as psychometric measures (Rouder & Haaf, 2019), and self-report and task-based measures may sometimes diverge (Dang et al., 2020).

We thus tested whether our measures of control-learning were reliable, given general concerns about the reliability of cognitive control tasks (Whitehead et al., 2019). For greater power, we collapsed across block orders. We ran correlations for behavioral measures across the “early/first” (e.g., block 1 for MC-MC-MIC-MIC and block 3 for MIC-MIC-MC-MC) and “late/second” (e.g., block 2 for MC-MC-MIC-MIC and block 4 for MIC-MIC-MC-MC) blocks of each PC context for each trial type (congruent/incongruent) (cf. Bejjani, Siqi-Liu, et al., 2020). Mean participant RT for unbiased items showed acceptable reliability for congruent trials (Figure 5A–D; PC-75: r(400) = 0.72, p < 0.001; PC-25: r(400) = 0.70, p < 0.001) and incongruent trials (PC-75: r(398) = 0.67, p < 0.001; PC-25: r(399) = 0.67, p < 0.001) across early and late blocks. Mean error rates for unbiased items showed worse reliability than RT (Figure 5E–H; PC-75 congruent: r(400) = 0.49, p < 0.001; PC-75 incongruent: r(400) = 0.59, p < 0.001; PC-25 congruent: r(400) = 0.43, p < 0.001; PC-25 incongruent: r(400) = 0.47, p < 0.001), but as with the biased/unbiased item correlations, this is likely due to the psychometric properties of accuracy as a dependent measure. Importantly, even though block order led to differences in the LWPC effect, the behavioral metrics were nonetheless stable across time, and the correlation strength was similar across all contexts and trial types.

Figure 5.

Unbiased item correlations for early (first block) vs. late (second block) within the mostly congruent (A, B, E, F) and mostly incongruent (C, D, G, H) contexts across congruent (A, C, E, G) and incongruent (B, D, F, H) trials for RT (ms) and Error Rate (%) data.

Next, because researchers often use difference scores in individual difference research despite their poor psychometric properties, we ran correlations between congruency effects across the mostly congruent and incongruent contexts for unbiased items. Early (first block) compared to late (second block) congruency effects for unbiased items were moderately and positively correlated within both the mostly congruent (RT: r(398) = 0.25, p < 0.001; corrected: r(398) = 0.27, p < 0.001; Accuracy: r(400) = 0.45, p < 0.001; corrected: r(400) = 0.49, p < 0.001) and mostly incongruent (RT: r(399) = 0.20, p < 0.001; corrected: r(399) = 0.22, p < 0.001; Accuracy: r(400) = 0.35, p < 0.001; corrected: r(400) = 0.36, p < 0.001) contexts. Comparing these correlation coefficients, using a Fischer’s r-to-z transformation, we found slight evidence for greater reliability within the mostly congruent context via accuracy (uncorrected: z = 1.60, p = 0.109; corrected: z = 2.25, p = 0.025) but not RT (uncorrected: z = 0.65, p = 0.514; corrected: z = 0.70, p = 0.485). In short, these control-learning measures showed acceptable reliability and were stable across blocks within the study (for the corresponding analyses on biased items, see Supplementary Text), such that participants responded consistently to each trial type within and across PC contexts over time. Thus, the lack of correlations between these measures and metrics of reward and punishment sensitivity cannot be accounted for by poor reliability in the control-learning measurements.

Better Incidental Memory for Context-Defining Trials

In order to understand how performance feedback is processed in the LWPC protocol, we tested recognition memory for the trial-unique, task-irrelevant feedback images that had been shown during the Learning Phase. We interpret incidental memory for these images to reflect sensitivity (attention) to reinforcement events (cf., Davidow et al., 2016; Gerraty et al., 2018; Höltje & Mecklinger, 2018, 2020).

In analyzing incidental memory of reinforcement events, we combined data across biased and unbiased items. The list-wise context, which is created by the biased items, induces the learned recruitment of control-demand for unbiased items (as supported by the correlation analysis, above). Reinforcement following the biased items may serve to reinforce the induced list-wise context, and reinforcement following the unbiased items may serve to reinforce the generalization of the control-demand associations. Thus, in understanding how reinforcement shapes control-learning, we collapse across both metrics of control-learning.

Hit rates.

Participants remembered the trial-unique feedback images above chance (Hit > False Alarms, t(399) = 19.69, p < 0.001, Cohen’s dz = 0.98). However, since the images were task-irrelevant and there were many images to remember, d-prime (M = 0.31) and Hit rates (M = 0.36) were relatively low.

All subsequent analyses focus on memory performance as a function of Learning Phase factors. Because we were interested in understanding how reinforcement shapes learned control associations, we examined only the trials on which participants had responded correctly. This is consistent with the analysis of Learning Phase RT data, where we examine only successful applications of control because we cannot know why exactly participants are incorrect (e.g., due to distracter interference, not paying attention, misremembered S-R mapping, etc.). Filtering out error trials also allows us to disentangle the potential role of motivation, because the comparison between the non-contingent (response logged) and contingent (correct) feedback groups is one emphasizing the affective value and successful response. We disentangle the potential role of statistical learning on successful applications of control by examining context-dependency irrespective of feedback group. Thus, by examining correct trials, memory is not confounded by the type of feedback received (correct/incorrect vs. response logged on both).

Analysis of variance.

We ran a repeated-measures ANOVA on Hit Rates for feedback images across the entire dataset, probing how sensitivity to reinforcement varied as a function of the experimental factors within the Learning Phase.

We found a significant interaction between block order and PC context for memory of feedback images (Figure 6A; N = 383, F(1,379) = 40.40, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.10, inclusion BF = 5.97 × 1015). Participants who experienced the mostly congruent context first displayed a stronger context-dependent effect on memory: they better remembered images from the PC-75 context (Mdiff = 0.044), while participants who experienced the mostly incongruent context first had a smaller tendency for better memory from the PC-25 context (Mdiff = 0.034). Finally, this interaction was also moderated by congruency in frequentist but not Bayesian analysis (F(1,379) = 8.38, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.02, inclusion BF = 0.47). There was also a significant main effect of congruency with minimal Bayesian evidence (F(1,379) = 4.72, p = 0.030, ηp2 = 0.01, inclusion BF = 0.21). These effects are explored in more depth with analyses below. No other effects were significant (F < 2.20, BFs < 1).

Figure 6. Memory Phase data.

Mean Hit rates (±SEM) are displayed as a function of block order (MC-MC-MIC-MIC/MIC-MIC-MC-MC) and PC context (PC-25/PC-75) (A); congruency (congruent/incongruent) trials for the first two blocks (B); or context shift (first vs. last blocks of each PC Context), congruency (congruent/incongruent), and block order (C) for feedback images reinforcing PC-50 items.

These context-dependent memory effects indicate that participants generally had better memory for feedback from context-defining trials, i.e., congruent trials in mostly congruent blocks, and incongruent trials in mostly incongruent blocks, qualified by block order and PC context: participants generally remembered images better from the (frequent) trials that defined the first context they experienced, but this effect was more pronounced for participants whose first context was mostly congruent. Interestingly, we did not observe an effect of feedback group on memory data, suggesting that any motivational effect derived from receiving performance-contingent feedback did not affect attention to reinforcement. This pattern of memory data is compatible with the statistical learning perspective, whereby participants would be particularly sensitive to positive reinforcement of their current expectations (e.g., encountering a congruent trial in a mostly congruent context), as evident in sensitivity to context-defining trial feedback images. By contrast, we do not find evidence for effects of motivation in the shape of performance-contingent feedback, which is in line with the lack of evidence for the impact of individual differences of reward and punishment sensitivity on learning obtained in the correlation analyses above.

To test whether the block order by PC context interaction reflected the possibility that most learning from feedback might occur early on in the task, we reran the ANOVA on Hit rates from blocks 1 and 2 only. As with the Learning Phase analyses, we here drop the within-participants PC context factor (as we only include the initial context for each participant). The block order factor thus becomes a between-participants PC factor, allowing us to contrast reinforcement sensitivity between the MC and MIC contexts in the absence of context order effects. Here, we found a significant main effect of congruency in both groups (Figure 6B; N = 390, F(1,386) = 13.67, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03, inclusion BF = 60.06; all other effects, F < 0.90, BFs < 1). Participants were better at remembering feedback images associated with congruent trials (M = 0.38) than incongruent trials (M = 0.36). Thus, contrary to the prediction of a motivational-based account, especially early in the task, participants were more sensitive to reinforcement for congruent trials.

Finally, a core assumption underlying the control-learning perspective is that people adapt to changes in contextual control demand, which implies that learning should be taking place when moving from one PC context to another. This assumption would predict more attention to feedback when new control demands are being learned, that is, at the beginning of each context. Accordingly, we reanalyzed the data to focus on the “context shifts”, i.e., the first block in which participants experienced a new PC context. Here, we thus grouped blocks 1 and 3 together as the “first” blocks of each context and blocks 2 and 4 as the “last” blocks of each context, and dropped the within-participants PC factor within the analysis, since the new context shift factor and the block order factor already carry the PC information. We observed larger Hit rates for “first” context blocks (M = 0.38) relative to the “last” context blocks (M = 0.33) (N = 390, F(1,386) = 110.49, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.22, inclusion BF = 3.49 × 1025). This effect supports the notion that participants paid more attention to reinforcement events when a context was new (at the beginning of the task and when the context changes) or – put a different way – that they became less sensitive or attentive towards reinforcement later in the blocks within each PC context, when adaptation to the current level of control demand had presumably been achieved.

However, we also observed evidence of context-dependent shifts in attention towards reinforcement: there was both a significant block order by congruency interaction (F(1,386) = 29.89, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.07, inclusion BF = 7.87 × 105) and a block order by congruency by context shift interaction (F(1,386) = 21.44, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05, inclusion BF = 152.94; as before, congruency: F(1,386) = 4.30, p = 0.039, ηp2 = 0.05, inclusion BF = 0.66, all other effects, F < 1.85, BFs < 1). Recapitulating the effects reported in the previous analysis, participants who experienced the mostly congruent context first showed better memory for images following congruent trials (Mdiff = 0.03), while participants who experienced the mostly incongruent context first showed better memory for images following incongruent trials (Mdiff = 0.01). Participants were thus most sensitive to reinforcement for trials that were most frequent in the context they experienced first, i.e., the trials that established the context, and this effect faded over time. As shown in Figure 6C, participants showed the memory benefit for images following the most frequent trial type from their first context in early blocks (MC first: Mdiff = 0.05; MIC first: Mdiff = 0.02). This context-dependent benefit for memory diminished in the later context shifts (MC first: Mdiff = 0.01; MIC first: Mdiff = 0.00).

In sum, we obtained evidence suggesting that statistical learning plays a larger role in control-learning than potential differences in motivation. Participants had context-dependent memory benefits in that they were more sensitive to images that followed the most frequent (context-defining) trial type from the context they experienced first. This pattern of encoding of reinforcement events was stronger for the PC-75 context, consistent with the stronger correlation between biased and unbiased item congruency effects for the PC-75 context. Contrary to a more motivation-based account of control-learning, we also found generally stronger memory for images following congruent than following incongruent trials. Altogether, these results mirror what we observed in the Learning Phase data: participants appear to anchor their expectations of upcoming control-demand to the context they learned first.

Discussion

The present study aimed to shed light on the interplay between motivation and learning in the recruitment of global control. To this end, we manipulated list-wide proportion congruency in an inducer/diagnostic item version of the color-word Stroop task. Trial-unique, task-irrelevant images were shown below feedback that was either performance-contingent (“correct/incorrect”) or non-contingent (“response logged”). A surprise recognition memory phase was administered to examine incidental encoding of the feedback images as a measure of sensitivity to reinforcement. We viewed the memory data through two lenses: statistical learning and motivation. If motivation helped to boost control-learning, we would observe better memory for feedback following incongruent, difficult trials. We would also observe group-level and individual-driven differences in learning behavior, with larger LWPC effects in the performance-contingent feedback group and larger LWPC effects for individuals higher in reward and punishment sensitivity – or some larger modulation of learning behavior by these individual differences. On the other hand, if statistical learning of the control-demand associated with each context acted as its own reinforcement, we would expect better memory for feedback of context-defining trials and around context changes. Notably, these are not mutually exclusive possibilities.

Using a much larger sample, we replicated previous work (Bejjani et al., 2020; Bugg & Chanani, 2011) and demonstrated a successful context-demand association induction by the biased items (see also Supplementary Text): we found pure control-learning within participants as indexed by the unbiased items, with a reduced congruency effect in blocks where conflict was more frequent. The LWPC was not impacted by feedback group and was largely driven by adjustments to incongruent trials between PC contexts, and control-learning effects were observable as early as the first two blocks between participants. These effects were stable: participants responded consistently both within and across the mostly congruent and incongruent contexts. Participants showed strong associations between biased and unbiased item performance, and responses to each trial type within a PC context were further correlated between early and late blocks. Participants were also largely unaware of the PC associated with the unbiased items (see Supplementary Text; Bejjani et al., 2018; Bejjani, Tan, et al., 2020).

Similar to a study with a much smaller sample size (Braem et al., 2014), we did not find strong associations between control-learning and trait reward sensitivity. The only associations of note were with biased items: a weak main effect of reward responsiveness and a significant negative correlation with the error rate LWPC, which is the opposite of what we predicted assuming a motivational boost to learning (see Supplementary Text). With respect to punishment sensitivity, the only interaction of note was between BIS scores and congruency, with larger congruency effects given higher BIS scores, for both biased and unbiased items. This interaction was stronger in biased items. Because both these associations were weak in magnitude but stronger in biased items, this may suggest that they are a product of frequency-based learning rather than pure control-learning, and our sample size (N = 402) is well-powered to detect individual differences that would have at least a modest effect. Moreover, in neither analysis did we find an interaction between BIS or BAS scores with the performance-contingency feedback manipulation, which is what a reward-based account would predict, should motivational influences reinforce learned control-demand. Overall, the lack of evidence for a positive association between trait reward or punishment sensitivity and control-learning in the presence of accuracy feedback speaks against the idea that reinforcement events promote the expression of the LWPC effect via a motivational mechanism.

The memory results offer several interesting new insights into the nature of control-learning. First, we found a greater memory benefit for the context participants experienced first, an effect that was accentuated in the PC-75 context. This is not explainable by a primacy-based account, because participants did not simply show better memory for all images shown earlier in the task, but instead showed context-dependent memory effects. Second, participants showed better memory for images following the more frequent trial type of the context they experienced first (i.e., context-defining trials), an effect that was larger for the first vs. last blocks of each PC context, suggesting enhanced sensitivity for context-defining events when participants were still learning the statistical structure of a given context. Finally, we also observed a small but stable increase in the successful encoding of images following congruent trials. In sum, sensitivity to reinforcement events, as measured via incidental encoding of feedback images, clearly varied as a function of control demand and temporal context.

The specific pattern of these results is generally consistent with predictions we derived from the statistical learning literature, which has documented enhanced attention to (Chun & Jiang, 1999; Zhao et al., 2013), and greater reinforcement by, contextually expected stimuli (Palmiteri et al., 2017). In line with the idea that expected trials positively reinforce the build-up of a statistical model of the task environment, memory was enhanced for feedback from context-defining trials (despite the fact that memory is often found to be enhanced for rare or unexpected events), and in particular following context shifts. The fact that memory was best for early trials in the context participants experienced first suggests a fast learning process, reflected in quickly diminishing attention to reinforcers, as well as a special priority granted to the early context-defining trials. The latter suggests that participants might anchor their control demand expectations to the first context they experience. Note that a possible alternative interpretation could be that memory is better for feedback in the frequent context-defining trials because (due to control-learning) those trials are rendered less demanding, allowing for more time to process the reinforcement events. However, this explanation would predict that memory should be even better during later stages of each context (due to additional learning and task practice), which we did not observe.

If motivational influences were driving control-learning, we had predicted an increase in Hit rates for images following incongruent trials, based on the assumption that participants experience more positive affect after correctly responding to incongruent trials (Schouppe et al., 2015), which in turn would also lead to increased attention to reinforcement for incongruent trials. Instead, the memory data indicate greater reinforcement sensitivity following congruent trials. One possibility is that the lower attentional demand on congruent trials allowed participants to spend more time processing the feedback images or, conversely, that the higher attentional demand on incongruent trials meant participants had less time to process reinforcement, though it is not clear why either of these effects would dissipate over time. Based on the present data alone, we cannot assess the degree to which these scenarios might apply, as we did not include neutral distracter trials as a baseline comparison. Teasing apart these possibilities represents an interesting avenue for future research.

In sum, we interpret the overall pattern of results to provide support for the idea that control-learning is an instance of statistical learning, wherein the occurrence of a contextually predicted event acts as positive reinforcement. We next note some caveats to these conclusions before relating these results to the broader literature.

Caveats

One major limitation of this study is that the performance non-contingent feedback group was run during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States (September-October) while the performance-contingent feedback group was run before (February) and ended a little after (mid-March) the community spread of COVID-19 had been acknowledged by the American government3. The first case of COVID-19 was detected on March 3rd in North Carolina4, suggesting that the students within the performance-contingent feedback group were not yet impacted by the pandemic, and the case rates by mid-March across the United States were less than what they were by Fall 20205. These differences in context between recruitment necessitate caution in comparing the performance-contingent and non-contingent feedback groups.

First, participants in the latter cohort may have had a higher exclusion/dropout rate due to screen fatigue (especially pronounced for undergraduate students in the sample). Second, consistent with other work finding an increase in depression symptoms in the United States during the pandemic (Ettman et al., 2020), the Census Bureau collected data in May suggesting that at least a third of Americans showed signs of clinical anxiety or depression at that time6. While only few studies have examined how control-learning is impacted in mental health disorders (e.g., schizophrenia; Abrahamse et al., 2017; see review of control, motivation, and depression, Grahek et al., 2019), or how stress specifically impacts control-learning (cf. e.g., control tasks and stress: Otto et al., 2013), it is a safe assumption that a general decrease in mental health would impact performance on our task. Unfortunately, we did not have the foresight to collect any baseline anxiety or depressive symptom data for the performance-contingent feedback group, so we neither know how the groups differ in these individual differences, nor how these individual differences might impact our results.

Another limitation, unrelated to the pandemic, is that this task can be difficult for some participants. Since the practice task consisted primarily of congruent trials, participants may have relaxed their control and been less prepared for conflict in the first block of trials. Moreover, the response deadline is fairly fast (cf. Bejjani et al., 2020). On the plus side, however, the difficulty of the task provided enough variability that we could analyze both reaction time and accuracy with respect to control-learning, which is not typically done with vocal responding studies, where error rates are low. Similarly, although participants may have developed expectations of low conflict from the practice task, they were informed that the next block would involve conflicting trials, and one fundamental assumption of control-learning is that participants can readily adapt their control to new contexts. Participants would thus quickly realize that this block of trials is not like the practice task that they experienced and adjust their attention accordingly.