Abstract

In the search for domestic natural additives favored by consumers for food flavor and antioxidant enhancement, this work aimed to estimate the influence of the substitution of sucrose by date syrup treated with gamma rays on the physico-chemical properties, antioxidant capacity and organoleptic quality of yogurt. Date syrup was irradiated by two different doses: 1 kGy and 2 kGy and incorporated into yogurt with different sucrose substitution percentages. The obtained results showed that gamma irradiation improved the microbiological quality of the date syrup while retaining its physicochemical quality. In fact, a significant reduction of the microbial charge was observed. The two-irradiation doses were proven not affected the total sugars, proteins, phenols or the syrup antioxidant activity. Besides, water content and color indices were found to decrease. The substitution of sucrose at the rate of 75 and 100% with date syrup irradiated by the dose of 1 kGy enhances the antioxidant activity, phenol, protein and sugar content of the prepared yogurt. Furthermore, yogurt with irradiated date syrup gave good sensory scores. The treated syrup, especially by the dose of 1 kGy, could be a promising technological path. This gamma irradiation guarantees a biological method for preserving the syrup for its use in the engineering of processes applied to the dairy industry.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13197-021-05000-z.

Keywords: Date syrup, Gamma radiation, Yogurt, Physico-chemical, Antioxidant capacity, Sensory properties

Introduction

Dates are extremely important in people’s diets in the arid and semi-arid regions. They are high-energy fruits, whose contained carbohydrates that are easily used by the human body (Al-Farsi et al. 2007). Besides, in fresh consumption, dates are processed into various products like paste, juice or syrup (Kader and Hussein 2009). Date syrup, locally named Rub, is produced in southern Tunisia from certain cultivars and the process needs extraction and boiling juice dates. It is consumed directly or used as an ingredient because it has useful functional properties as well as the ability to replace sugar in certain foods such as ice cream, beverages, confectionery and bakery goods (Abbes et al. 2013). El-Nagga and El-Tawab (2012) tried to use syrup in the preparation of Zabady and biogarde and concluded that the caloric values, total solids, soluble nitrogen, titratable acidity and ash content were increased. In addition, Zabady and biogarde with 2% syrup were richer in most of the essential amino acids. Salama (2004) studied the use of fresh date syrup as a sweetening and flavoring ingredient in ice cream manufacture and increase the nutritive value by fortifying it with proteins, minerals and vitamins.

Syrup beneficial application requires free microbe’s contamination which could be from the raw materials or arising from syrup manipulation handlers and equipment (Finola et al. 2007). The same problems are faced by many other beverages and different techniques have been used to reduce contamination. Although many treatments such as pasteurization and blanching are realized, they can damage the characteristics of the product. Irradiation is the treatment that has the lowest impact on food properties. Gamma irradiation is a nonchemical treatment that is widely used to control the postharvest losses of date fruits (Abd El-Moneim et al. 2011). It is a safe disinfection technology with a good ability to improve food hygienic and physicochemicals properties of the product (Khattak et al. 2008) such as fruit juices (Kalaiselvan et al. 2018) by killing bacteria that cause food poisoning (Munir and Federighi 2020). Sixty countries have now approved this process and the recommended dose for each food product was defined (Munir and Federighi 2020).

Consequently, the incorporation of irradiated syrup to substitute sucrose in products such as yogurt may offer desirable characteristics. This alternative is in the context of incorporating processed fruit into yogurt which is an approach aiming to increase the content of phenolic compounds in the product as well as to improve its antioxidant profile. The enrichment of yogurt with antioxidants of natural origin also responds to consumer demand for "clean and healthy" foods (Granato et al. 2018). A preliminary study should be undertaken to evaluate the functionality and influence of irradiated syrup to replace sugar in yogurt products. Thus, the objective of this study is to evaluate the irradiated syrup properties and its capacity to modify the physico-chemical properties and the sensory acceptability of yogurts.

Material and methods

Material

Dates of Deglet Nour variety were collected from “Nefzaoua” oases which belong to continental oases, situated in Southern Tunisia. This area was chosen for its production which is the highest in comparison with the other continental oases. The fruits were pitted and the flesh was sliced and kept refrigerated in sealed polyethylene bags until processing.

Date syrup process

Firstly, date juice was extracted using hot water (60 °C, 1:3). Juice clarification was done by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 15 min and then concentrated in a rotary evaporator under vacuum at 70 °C to about 70 °Brix. The produced date syrup was placed in glass bottles and stored at 4 °C until analysis.

Gamma irradiation

The processing of the extracted syrup was done by gamma radiation technology at the National Center of Nuclear Sciences and Technologies in Sidi Thabet, Tunisia (CNSTN). Irradiation process was carried out by Co-60 gamma ray source at the rate of 100 Gy/min. The syrup was exposed to radiation in polyethylene tubes with a total volume of 40 ml. Samples were irradiated with two different doses 1 and 2 kGy during 20 min. Ionization treatments were carried out at room temperature.

Manufacture of yogurt

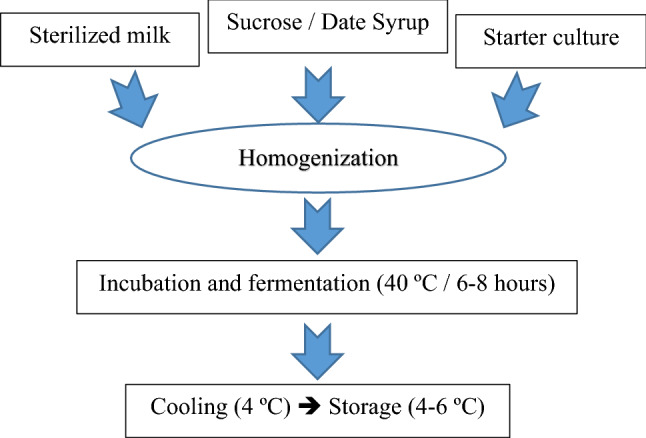

Yogurt mixes were prepared according to a previous study (Hussein and Aumara 2006; Akpinar et al. 2020) (Fig. 1). Mixes’ compositions are shown in Table 1 and divided into four parts. While the first part was prepared by sucrose 100% (control), the other three parts were prepared by replacing sucrose with different date syrup (non-irradiated, irradiated with 1 kGy and irradiated with 2 kGy) and with different percentages, 25, 50, 75 and 100%. Each mix was extensively homogenized and the incubation was in 40 °C until clotting and cooled at 4 °C.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of yogurt production (Akpinar et al. 2020, modified)

Table 1.

Composition of yogurt (SN: Non irradiated Syrup; ST1: Syrup treated by 1 kGy, ST2: Syrup treated by 2 kGy)

| Control | Yogurt + SN | Yogurt + ST1 | Yogurt + ST2 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sterilized Milk (ml) | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 |

| Yogurt starter (g) | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Sucrose (g) | 6.5 | 4.9 | 3.25 | 1.6 | 0 | 4.9 | 3.25 | 1.6 | 0 | 4.9 | 3.25 | 1.6 | 0 |

| Syrup (g) | 0 | 1.6 | 3.25 | 4.9 | 6.5 | 1.6 | 3.25 | 4.9 | 6.5 | 1.6 | 3.25 | 4.9 | 6.5 |

| Sucrose Substitution (%) | 0 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 |

| Formulation label | Control | Y + 25%SN | Y + 50%SN | Y + 75%SN | Y + 100%SN | Y + 25%ST1 | Y + 50%ST1 | Y + 75%ST1 | Y + 100%ST1 | Y + 25%ST2 | Y + 50%ST2 | Y + 75%ST2 | Y + 100%ST2 |

Chemical composition analysis

To see the effect of irradiation on syrup chemical quality as well as its introduction in yogurt, the chemical analysis of syrups and yogurts were conducted in triplicate. For the moisture content, up to 10 g of syrup or yogurt was freeze-dried and the moisture content was determined by the difference in weight before and after the assay and expressed as a percent. Yogurt extract was prepared according to Raikos et al. (2019). Soluble sugars were determined according to the anthrone method and proteins as described by Fuentes-Alventosa et al. (2009). Ash content was determined according to the method of the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (1990). Total polyphenol content was quantified according to the Folin − Ciocalteu spectrophotometric method, using gallic acid as a reference standard. Aliquots of 20 µl of each liquid fraction were dosified in triplicate, and 100 µL of Folin − Ciocalteu phenol reagent (0.2 M) was added to each tube and mixed. Afterward, 80 µl of Na2CO3 (75 g/L) was added and mixed well. A microplate reader (iMark, BioRad) was set at 655 nm, and the absorbance was measured after 6 min. Results are expressed as gallic acid equivalents (EAG/100 g). Soluble antioxidant activity was determined by the DPPH• method (2,2-diphényl-1-picrylhydrazyle) (Rodríguez et al. 2005). Ten µl of the sample was added to 190 µl of DPPH• (3.8 mg/50 mL methanol), after 30 min in obscurity the absorbance was measured (in triplicate) at 480 nm. Antioxidant activities were expressed as ascorbic acid equivalents (mg EAc Asc/100 g).

Color measurement

Color analysis of the yogurt beverages was performed using a Konica Minolta CR300 colorimeter (Konica Minolta Solutions Ltd., Basildon, UK). The measurements were conducted under artificial light. The color parameters L* (lightness), a* (red/greenness), and b* (yellow/blueness) of the yogurt samples were evaluated according to the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) L*a*b* system (CIE 1976).

Microbial analysis

For microbial enumeration, appropriate decimal dilutions were prepared with sterile peptone water and plated in triplicate on different media: Violet Red Bile Lactose agar for total coliforms Sabouraud dextrose + chloramphenicol agar for yeasts and moulds, Tryptone Bile X-glucuronide agar for Escherichia coli βGlucuronidase+, Baird-Parker Agar for Staphylocoques Coagulase (+) and Hektoen Enteric Agar for Salmonella enumeration.

Yogurt sensory evaluation

Sensory tests were conducted by 40 panelists from the Department of Food Process Engineering (Higher Institute of Technological Studies, Kebilli Tunisia). Yogurts were evaluated on the basis of acceptability of their appearance, flavor, texture and after-taste by a 9-point scale, where 9 means most liked and 1 most disliked. The samples were placed into a 30 ml plastic cup and identified with random numbers. During the panel session, water was provided to panelists to minimize any residual effect before testing a new sample (Stone et al. 1974).

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean value ± standard deviation. The studied parameters were analyzed separately by ANOVA (Analysis of variance) with post-hoc Student–Newman–Keuls comparisons. Hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using the Euclidean distance, and the Wards linkage was used to categorize yogurt groups and the statistical program was SPSS 16.0 (13 Sep. 2007, SPSS Inc.). XLSTAT (2020) was used to perform a principal component analysis (PCA) to assess relationships between the physico-chemical data of the yogurt samples.

Result and discussion

Gamma irradiation effect on date syrup

The physico-chemical properties of the different samples of syrup are presented in Table 2. The analyses showed that moisture was in the range from 30.02 to 35.20%, gamma irradiation caused significant decrease in the moisture content. During storage, the stability of syrup is highly correlated with water content. In this way, gamma irradiation could be an important technology to strengthen the syrup freshness by reducing moisture, and subsequently avoiding its spoilage by microbes. Undesirable molecules such as alcohol and carbon dioxide could be released during fermentation and caused bad taste (Nakasaki et al. 2013).

Table 2.

Physicochemical properties of the different samples of syrup (SN: None irradiated Syrup; ST1: Syrup treated by 1 kGy, ST2: Syrup treated by 2 kGy)

| Water % | Total sugar g/100 g | Protein g/100 g | Phenol mgEAG / 100 g | Antioxidant mgEAA/100 g | Color | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* Lightness | a* (red/greenness) | b* (yellow/blueness) | ||||||

| SN | 35.20 ± 2.02 a | 64.58 ± 4.12 a | 1.70 ± 0.20 a | 501.97 ± 39.31 a | 240.73 ± 4.03 a | 26.99 ± 0.65 a | 7.50 ± 0.76 a | 7.47 ± 0.431 a |

| ST1 | 30.02 ± 1.80 b | 64.64 ± 3.50 a | 1.74 ± 0.05 a | 556.06 ± 4.08 a | 239.44 ± 3.38 a | 24.58 ± 0.11 b | 4.61 ± 0.33 b | 3.24 ± 0.252 c |

| ST2 | 30.67 ± 1.36 b | 65.08 ± 3.23 a | 1.80 ± 0.02 a | 510.25 ± 13.24 a | 239.78 ± 4.08 a | 24.63 ± 0.14 b | 4.27 ± 0.16 b | 5.13 ± 0.272 b |

Mean and standard deviation values with the same letter within the same parameter were not significantly different (p ≥ 0.05)

Sugar contents in different syrups are shown in Table 2 and the values ranged between 64.58 and 65.08 g/100 g. Similarly to previous studies, it has been reported that irradiation does not change total sugar contents in Hawaiian fruits (Mitchell et al. 1992) and fresh tamarind juice (Lee et al. 2009) even at higher irradiation doses. In general, irradiation was found to break down complex carbohydrates to simpler sugars (Wu et al. 2002). In the current research, these insoluble carbohydrates were discarded during syrup process, which may explain the sugar content stabilization. Protein content in non-irradiated syrup (Table 2) was similar to those obtained previously by El-Nagga & Abd El-Tawab (2012) with a value of 1.70 g/100 g. Despite the insignificant effect of irradiation, a slight enhancement was observed in protein content and the values became 1.74 and 1.80 g/100 g for 1 kGy and 2 kGy, respectively. Similar results have reported that gamma irradiation has no effect on protein content of rice (Dianxing et al. 2004). However, Imdadullah et al. (2010) have noted a decrease of up to 1% in protein content in irradiated dates. In fact, Amino acids and protein are more sensitive to irradiation when it is practiced in solution and the content of the remaining protein is dependent on the irradiation dose (Abd El-Moneim et al. 2011). The trivial effect of gamma radiation on the protein content of syrup could be explained by the fact that protein aggregates under irradiation, which decreases its solubility (Manjaya et al. 2007).

Phenol is an important bioactive compound that gives antioxidative property of the diet. Non irradiated syrup showed a quantity of 501.67 mg EAG/100 g. Irradiation with 1 kGy and 2 kGy have increased total phenolic content and the values were 556.06 and 510.25 mg EAG/100 g, respectively but the ANOVA showed it was not significant. The increase of the total phenol has been detected after the irradiation of several vegetal materials (Khattak et al. 2008) and attributed to the estrangement of phenolic compounds from glycosidic components and the decomposition of the larger phenolic compounds. However, Campos (2005), noted that X-ray and gamma rays did affect total phenolic content in Maytenus aquifolium leaves. The result on phenol content depends on the phenol profile of the extract (Rodríguez-Pérez et al. 2015) and could be attributed to the dose of radiation (Khattak et al. 2008). While some phenolic molecules are resistant to the irradiation, others are sensitive when broken and release other molecules (Rodríguez-Pérez et al. 2015).

Concerning the DPPH scavenging activity, no significant change was detected when the sample was subjected to the gamma radiation. The antioxidant capacity of non-irradiated and irradiated syrups are up to 240 mgEAA/100 g. These results are in agreement with those reported by Kim et al. (2009), indicating that gamma irradiation resulted in the maintenance of the natural antioxidants necessary for the quality of product. Rajurkar and Samdani (2012) noted the differential effect of irradiation on antioxidant capacity depending on the solvent extract of Amoora rohitaka. No significant effect was observed in methanol extract, however, ethanol and aqueous ones antioxidant capacities were increased after irradiation.

Syrup color changing from light brown to dark brown after irradiation was well reflected by the combined decrease of L*, a* and b*. Compared to the control, both 1 kGy and 2 kGy showed significant changes in L*, a* and b* due to irradiation treatments (Table 2). Chniti (2015) has stated that the coloring substances are the result of a non-enzymatic browning (Maillard Reaction), which is defined as the set of interactions resulting from the initial reaction between a reducing sugar and an amino group. The melanoids produced by Maillard reaction are the major contributors to the dark color of the syrup (Wang et al. 2001; Nasehi and Ansari 2012). The dark color in addition to Maillard reactions could be attributed to other condensation reactions caused by proteins, sugars and phenols naturally present in the processing.

The effect of gamma irradiation on the survival microbes in syrups are shown in the Table 3. The total mesophilic bacteria were found in non-irradiated syrup with 2.9 × 103 cfu/g. Coliforms and salmonella were not detected, which accords well with the results found in the studies conducted by Ramadan (2000), Belala et al. (2010) and Aleid et al. (2014). However, these authors have noted a total of moulds and yeasts, which is not detected in our study. This difference in microbial total could be attributed to the syrup manipulation handlers and equipment. After gamma irradiation, we noted a significant decrease of the total mesophilic bacteria populations in syrup. Although the irradiation dose used in this study is low (1–2 kGy), it is sufficient to inactivate the majority of microbe populations. Different doses have been used by other studies. For example, the inactivation of aerobic mesophiles and yeasts and moulds in shredded iceberg lettuce was realized using a dose of 0.55 kGy (Foley et al. 2002). In fruit juices, the dose values of 1 to 3 kGy was reported to destroy yeasts and moulds (Narvaiz et al. 1992) and from 0.3 to 0.7 kGy for pathogenic bacteria (Buchanan et al. 1998). Alighourchi et al. (2014) have revealed that while the gamma radiation dose of 1 kGy reduced E. coli by 6.66 log10 cfu/mL, that of 3 kGy reduced S. cerevisiae by 5.08 log10 cfu/mL. The microbial destruction can be explained by the interaction of gamma rays with water, which produces reactive free radicals that provoke double strand DNA rupture unrepairable by the cells (Hall and Giaccia 2006).

Table 3.

Microbiological enumeration (log10cfu/g) of the different date syrups (SN: None irradiated Syrup; ST1: Syrup treated by 1 kGy, ST2: Syrup treated by 2 kGy)

| Total mesophilic bacteria | Thermotolerant coliforms | Total coliforms | Yeasts and moulds | Salmonella entiridis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SN | 2.9 ± 0.55 a | - | - | - | - |

| ST1 | 0.033 ± 0.01 b | - | - | - | - |

| ST2 | 0.04 ± 0.01 b | - | - | - | - |

Mean and standard deviation values with the same letter within the same parameter were not significantly different (p ≥ 0.05)

Effect of incorporation of irradiated syrup in yogurt

The physicochemical properties of yogurt samples substituted with different percentages of syrup are shown in Table 4. Whereas the water content has been slightly enhanced, no significant difference with the control was observed. As for syrup addition, it has affected the water activity, thus increasing the available water for microbial growth (Troller and Christian 1978). The enrichment of yogurt with syrup enhanced the water activity, and hence irradiation is proven to be a reliable method of limiting the growth of pathogenic and spoilage organisms.

Table 4.

Physico-chimical proprieties and color analysis of the different formulations of yogurt (Y: Yogurt; SN: Non irradiated Syrup; ST1: Syrup treated by 1 kGy, ST2: Syrup treated by 2 kGy)

| Formulations | Water content % | Aw | pH | Total sugar g/100 g | Protein g/100 g | Phenols mg EAG/100 g | Antioxidant capacity mg EAc Asc/100 g | L* | a* | b* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 80.00 ± 0.00a | 0.91 ± 0.01c | 4.12 ± 0.10ab | 12.88 ± 0.04c | 1.29 ± 0.06bcd | 146.41 ± 7.55bc | 23.86 ± 6.64bc | 74.31 ± 2.80a | − 3.40 ± 0.05 h | 8.16 ± 1.13a |

| Y + 25%SN | 83.67 ± 5.77a | 0.93 ± 0.01b | 4.13 ± 0.13ab | 12.98 ± 0.01abc | 1.33 ± 0.20abc | 135.15 ± 10.62bc | 24.47 ± 1.20abc | 70.78 ± 3.71a | − 2.34 ± 0.26ef | 9.28 ± 0.861a |

| Y + 50%SN | 86.67 ± 5.24a | 0.95 ± 0.01a | 4.09 ± 0.11ab | 13.01 ± 0.01ab | 1.35 ± 0.05abc | 127.25 ± 1.63d | 22.57 ± 3.40c | 75.67 ± 4.58a | − 1.79 ± 0.28de | 10.49 ± 1.01a |

| Y + 75%SN | 83.33 ± 5.66a | 0.95 ± 0.00a | 4.16 ± 0.14ab | 13.04 ± 0.04a | 1.33 ± 0.02abc | 173.41 ± 12.66b | 29.34 ± 3.59abc | 73.95 ± 3.70a | − 1.15 ± 0.62bc | 9.82 ± 0.676a |

| Y + 100%SN | 83.33 ± 5.77a | 0.95 ± 0.00a | 4.05 ± 0.01b | 13.06 ± 0.02a | 1.35 ± 0.09abc | 150.31 ± 17.60bc | 33.14 ± 3.75ab | 71.53 ± 1.2a | − 0.35 ± 0.30a | 10.54 ± 0.307a |

| Y + 25%ST1 | 80.00 ± 0.00a | 0.95 ± 0.01a | 4.23 ± 0.01a | 13.04 ± 0.04a | 1.32 ± 0.03abc | 143.38 ± 20.41bc | 30.49 ± 1.43abc | 74.37 ± 2.87a | − 2.90 ± 0.13gh | 8.66 ± 0.555a |

| Y + 50%ST1 | 85.00 ± 7.07a | 0.96 ± 0.00a | 4.19 ± 0.12ab | 13.04 ± 0.02a | 1.34 ± 0.02abc | 138.56 ± 22.02bc | 29.28 ± 2.57abc | 74.52 ± 2.92a | − 2.21 ± 0.26ef | 10.22 ± 0.406a |

| Y + 75%ST1 | 83.33 ± 5.77a | 0.95 ± 0.00a | 4.26 ± 0.03a | 13.03 ± 0.01a | 1.37 ± 0.03ab | 209.67 ± 20.33a | 34.02 ± 2.12a | 74.35 ± 1.77a | − 1.52 ± 0.17 cd | 10.28 ± 0.703a |

| Y + 100%ST1 | 85.00 ± 4.92a | 0.96 ± 0.00a | 4.04 ± 0.10b | 13.04 ± 0.02a | 1.39 ± 0.03a | 157.53 ± 21.71b | 33.30 ± 0.72ab | 72.14 ± 0.38a | − 0.94 ± 0.03b | 9.82 ± 0.285a |

| Y + 25%ST2 | 80.00 ± 0.00a | 0.96 ± 0.00a | 4.33 ± 0.01a | 12.94 ± 0.08abc | 1.27 ± 0.08cd | 119.89 ± 13.04d | 26.43 ± 2.25abc | 75.69 ± 0.89a | − 3.06 ± 0.03gh | 9.16 ± 0.438a |

| Y + 50%ST2 | 83.33 ± 5.66a | 0.96 ± 0.00a | 4.29 ± 0.03a | 12.90 ± 0.01bc | 1.24 ± 0.08d | 121.12 ± 7.84c | 24.74 ± 6.06abc | 74.11 ± 1.30a | − 2.65 ± 0.12 fg | 9.09 ± 0.191a |

| Y + 75%ST2 | 83.33 ± 5.82a | 0.96 ± 0.00a | 4.36 ± 0.04a | 12.89 ± 0.01bc | 1.35 ± 0.05abc | 153.19 ± 6.53b | 27.65 ± 3.35abc | 75.38 ± 1.90a | − 1.81 ± 0.06de | 10.02 ± 1.00a |

| Y + 100%ST2 | 84.00 ± 0.00a | 0.95 ± 0.00a | 4.14 ± 0.11ab | 12.89 ± 0.01bc | 1.32 ± 0.00abc | 157.76 ± 11.13b | 29.34 ± 2.29abc | 71.46 ± 3.64a | − 1.50 ± 180c | 8.60 ± 2.67a |

Mean and standard deviation values with the same letter within the same parameter were not significantly different (p ≥ 0.05)

The samples with 100% syrup substitution had slightly lower pH values compared to the control and those of samples with 25–50–75% syrup substitution. The pH of the control was 4.12, which is close to that found by De et al. (2014) but slightly lower than that found by Akpinar et al. (2020). This pH level is ideal for yogurt, giving it the acidity characteristics and acting as a preservative against undesirable bacteria. The total sugar values of the yogurts with any level of syrup substitution were slightly different (Table 4) and the mean value was around 13 g/100 g. Significant effect was observed on the total phenol and antioxidant capacity. Actually, they increase with the level of substitution with non-irradiated or irradiated syrup (Table 4). The same results were reported by Raikos et al. (2019), which noted that the antioxidant capacity of the yogurt was increased with the fortification with Salal Berries and Blackcurrant pomace.

Moreover, the L*, a* and b* values of the yogurt samples with various degrees of sucrose substitution by syrup are shown in Table 4. No significant effects were observed after the replacement of sugar with syrup on the L* and b* values. However, a* values increased significantly with the increase in the substitution degree of sucrose especially by irradiated syrup. This may be attributed to the relatively lower solubility of syrup compared to sucrose (Taylor et al. 2008). Syrup might have slight indissoluble nature in the mixing of the yogurts affecting consequently the color.

Unwanted microbes in yogurt were studied during three weeks of storage at 4 °C. The analyses showed that all yogurt samples were freed off from total moulds and yeasts, coliforms and salmonella. This is due to using sterile compounds of yogurt and no microbial contamination during processing.

Multivariate analysis of syrup substituted yogurts

The dendrogram was obtained by the hierarchical cluster analysis of all formulations considering the physico-chemical attributes (Supplementary File 1). Three main groups were identified: group 1 (Y + 75%ST1), group 2 (Y + 75%SN, Y + 75%ST2, Y + 100%SN, Y + 100%ST2 and Y + 100%ST1) and group 3 (Y + 25%ST1, Control, Y + 50%ST1, Y + 25%SN, Y + 50%SN, Y + 25%ST2 and Y + 50%ST2). As indicated by the linkage distance, Yogurt with 75% ST1 had the largest cluster discrimination compared to that of the other treatments. The samples with high substitution (75 and 100%) have a shorter cluster distance to Y + 75%ST1 sample, compared to that of the samples with low substitution (25 and 50%) and the control. This reflects the significant effect of sucrose substitution by date syrup on the overall parameters.

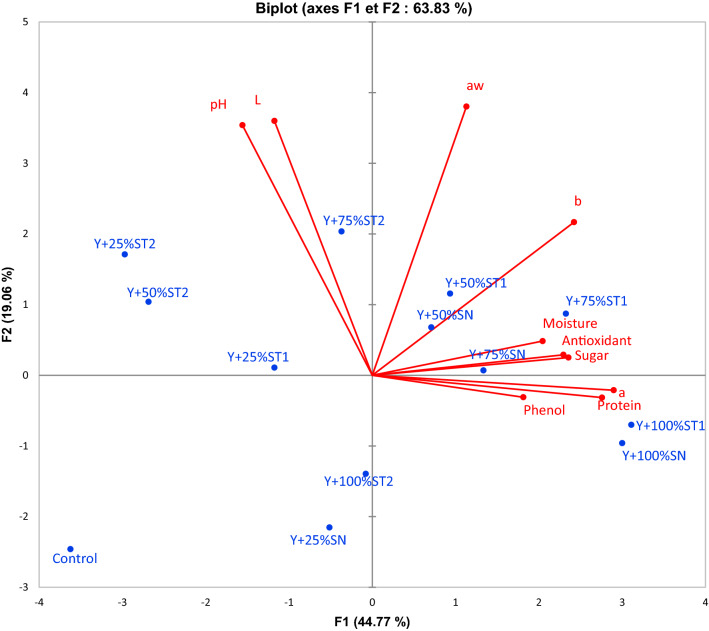

The results obtained by the principal component analysis of all yogurt samples considering the physico-chemical attributes are presented in Fig. 2a. The PCA described the interrelations of the physico-chemical with the yogurt formulations. It showed that 63.83% of the total variation was explained by the first two principal components (F1 = 44.77% and F2 = 19.06%), which indicates a strong pattern of differentiation between formulations. The F1 was highly correlated with antioxidant (+ 0.722), phenol (+ 0.571), protein (+ 0.868), sugar (+ 0.741), moisture (+ 0.643), a* (+ 0.912) and b* (+ 0.762). The F2 was correlated with aw (+ 0.780), L* (+ 0.739) and pH (+ 0.726) (Fig. 2b, Supplementary File 2). In terms of formulations, four main yogurt groups were separated along F1 and F2. Concerning the first one, it is composed of Y + 100%ST1, Y + 75%ST1and Y + 100% SN samples which is strongly associated with the moisture, phenol, antioxidant, sugar, protein a*, b* and color values. As for the second component analysis, it opposes Y + 75%ST2 to Y + 25%SN and it is linked mostly to pH, L* and aw parameters. Finally, the control sample is negatively correlated with the two component analyses, so it is characterized by the lowest value of all measurements. The Y + 100%ST1, Y + 75%ST1and Y + 100%SN were associated with the higher moisture, phenol, antioxidant, sugar, protein a*, b* and color values.

Fig. 2.

Representation of yogurt formulations and the variables on the plane 1–2 of principal component analysis. (Y: Yogurt; SN: Non irradiated Syrup; ST1: Syrup treated by 1 k Gy, ST2: Syrup treated by 2 kGy)

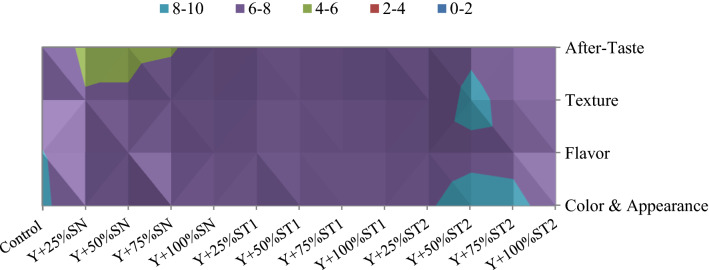

Sensory evaluation of syrup enriched yogurts

The effects of irradiated sucrose substitution with date syrup on the sensory evaluation of yogurts are presented in Fig. 3. In fact, the majority of formulations were similar in color and appearance, except control, Y + 50%ST2 and Y + 75%ST2, which has higher scores. For the flavor, the control showed higher rate than the other formulations but the difference was not significant. Regarding Y + 25%SN, Y + 50%SN and Y + 75%SN formulations, they have lower texture and after-taste scores. Irradiated syrup seems to affect the relative intensity of the yogurt sensory evaluation more. Indeed, the scores of the Y + 50%ST2 formulation with lower degree Y + 75%ST2 were the best for all attributes when compared to other yogurt treatments. As indicated by Torrico et al. (2019) who have noticed that sucrose and fruit aroma interact with each other in the form of potentiation, and thus irradiated syrup could interact with yogurt components to give a good appreciation and therefore better acceptability.

Fig. 3.

Sensory evaluation of different formulations of yogurt (Y: Yogurt; SN: Non irradiated Syrup; ST1: Syrup treated by 1 kGy, ST2: Syrup treated by 2 kGy)

Conclusion

Date syrup irradiation is a promised technology to improve the microbiology quality and with keeping very good physicochemical properties. Furthermore, sucrose substitution in yogurt with 1 kGy irradiated syrup especially by a percentage of 75% is a promising formulation to be considered not only to increase the content of phenolic compounds of the product but also to improve its antioxidant profile and sensory quality. Further investigations should be done to understand interaction between date syrup and yogurt components and to evaluate the acceptability of date syrup enriched yogurt during extended storage periods.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

HH, SA and MS collected the material and designed the trial. HH, SA, and MS, BMN and JM conducted the experiments. HH performed the statistical analyses. HH investigated literature and wrote the original draft. HH, BMN and JM revised the draft. HH responsible for research planning, administration and funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The research was supported by the ministry of higher education and scientific research of Tunisia.

Availability of data and material

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary files.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflicts of interest exist.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abbes F, Kchaou W, Blecker C, Ongena M, Lognay G, Attia H, Besbes S. Effect of processing conditions on phenolic compounds and antioxidant properties of date syrup. Ind Crops Prod. 2013;44:634–642. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Moneim MR, Afify MR, Ebtesam AM, Hossam SE. Effect of Gamma Radiation on Protein Profile, Protein Fraction and Solubility’s of Three Oil Seeds: Soybean, Peanut and Sesame. Not Bot HortiAgrobo. 2011;39(2):90–98. doi: 10.15835/nbha3926252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akpinar A, Saygili D, Yerlikaya O. Production of set-type yoghurt using Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus durans strains with probiotic potential as starter adjuncts. Int J Dairy Technol. 2020;73(4):726–736. doi: 10.1111/1471-0307.12714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aleid M, Bakri H, Hassan L, Salah A, Safar H, Sobhy M. Microbial Loads and Physicochemical Characteristics of Fruits from Four Saudi Date Palm Tree Cultivars: Conformity with Applicable Date Standards. Food NutrSci. 2014;5:316–327. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Farsi M, Alasalvar C, Al-Abid M, Al-Shoaily K, Al-Amry M, Al-Rawahy F. Compositional and fonctional characteristics of date syrup and their by-products. Food Chem. 2007;104:934–947. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.12.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alighourchi H, Barzegar M, Sahari MA, Abbasi S. The effects of sonication and gamma irradiation on the inactivation of Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae in pomegranate juice. Iranian J microbial. 2014;6(1):51–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC (1990) Association of official analytical chemists. In: Helrich K (ed) Official methods of analysis, 15th edn. Arlington, VA, pp 1025–1034

- Belala EH, Mohammed S, Mustafa IA, Mohammed N, Al-Dosari N. Evaluation of date-feed ingredients mixes. Anim Feed SciTechnol. 2010;81:291–298. doi: 10.1016/S0377-8401(99)00091-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan R, Edelson S, Snipes K, Boyd G. Inactivation of Escherichia coli O157: H7 in apple juice by irradiation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4533–4535. doi: 10.1128/AEM.64.11.4533-4535.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos P, Yariwake JH, Lancas FM. Effect of X- and gamma-rays on phenolic compounds from Maytenus aquifoliumMartius. J RadioanalNuclChem. 2005;264:707–709. [Google Scholar]

- Chniti S (2015) Optimisation de la bioproduction d’éthanol par valorisation des refus de l’industrie de conditionnement des dattes. Thèse de doctorat. Université de Rennes

- CIE (Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage) (1976) Recommendations on uniformcolor spaces-color difference equations, Psychometric Color Terms. CIE Publication, Paris

- De N, Goodluck TM, Bobai M. Microbiological quality assessment of bottled yogurt of different brands sold in Central Market, Kaduna Metropolis, Kaduna, Nigeria. Int J CurrMicrobiol App Sci. 2014;3(2):20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dianxing W, Qingfu Y, Wang Z, Xia Y. Effect of gamma irradiation on the nutritional components and CrylAb protein in the transgenic rice with a synthetic CrylAb gen from Bacillus thuringiensis. RadiatPhysChem. 2004;69:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- El-Nagga EA, Abd El–Tawab YA. Compositional characteristics of date syrup extracted by different methods in some fermented dairy products. Food SciTechnol. 2012;57(1):29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Finola MS, Lasagno MC, Marioli JM. Microbiological and chemical characterization of honeys from central Argentina. Food Chem. 2007;100:1649–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.12.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foley DM, Dufour A, Rodriguez L, Caporaso F, Prakash A. Reduction of Escherichia coli 0157:H7 in shredded iceberg lettuce by chlorination and gamma irradiation. RadiatPhysChem. 2002;63:391–396. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Alventosa JM, Rodríguez-Gutiérrez G, Jaramillo-Carmona S, Spejo-Calvo JA, Rodríguez-Arcos R, Fernández- Bolaños J, Guillén-Bejarano R, Jiménez-Araujo A. Effect of extraction method on chemical composition and functional characteristics of high dietary fibre powders obtained from asparagus byproducts. Food Chem. 2009;113:665–671. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.07.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Granato D, Santos JS, Salem RDS, Mortazavian AM, Rocha RS, Cruz AG. Effects of herbal extracts on quality traits of yogurts, cheeses, fermented milks, and ice creams: a technological perspective. CurrOpin Food Sci. 2018;19:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hall EJ, Giaccia AJ. Radiobiology for the Radiologist. 6. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein GAM, Aumara IE. Preparation and properties of probiotic frozen yoghurt made with sweet potato and pumpkin. Arab Univ J AgricSci. 2006;14:679–692. [Google Scholar]

- Imdadullah M, Shah Z, Ihsanullah I, Khan H, Rashid H. Effect of gamma irradiation, packaging and storage on the nutrients and shelf life of Palm dates. J Food ProcPres. 2010;34:622–638. [Google Scholar]

- Kader A, Hussein A (2009v Harvesting and postharvest handling of dates. The International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), pp 1–18

- Kalaiselvan RR, Sugumar A, Radhakrishnan M (2018) Gamma irradiation usage in fruit juice extraction. In: Rajauria G, Tiwari BK (eds.), Fruit juices. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 423–435

- Khattak KF, Simpson TJ, Ihasnullah X. Effect of gamma irradiation on the extraction yield, total phenolic content and free radical-scavenging activity of Nigella staiva seed. Food Chem. 2008;110:967–972. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Shin MH, Hwang YJ, Srinivasan P, Kim JK, Park HJ, Byun MW, Lee JW. Role of gamma irradiation on the natural antioxidants in cumin seeds. RadiatPhysChem. 2009;78:153–157. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Kim JK, Srinivasan P, Choi J, Kim JH, Han SB, Kim DJ, Byun MW. Effect of gamma irradiation on microbial analysis, antioxidant activity, sugar content and color of ready-to-use tamarind juice during storage. LWT: Food SciTechnol. 2009;42(1):101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2008.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manjaya JG, Suseelan KN, Gopalakrishna T, Pawar SE, Bapat VA. Radiation induced variability of seed storage proteins in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merrill] Food Chem. 2007;100:1324–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.11.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GE, McLauchlan RL, Isaacs RL, Williams DJ, Nottingham SM. Effect of low dose gamma radiation on composition of tropical fruits and vegetables. J Food Compos Anal. 1992;5:291–311. doi: 10.1016/0889-1575(92)90063-P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munir MT, Federighi M. Control of foodborne biological hazards by ionizing radiations. Foods. 2020;9(878):1–23. doi: 10.3390/foods9070878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakasaki K, Kwon SH, Ikeda HI. Identification of microorganisms in the granules generated during methane fermentation of the syrup wastewater produced while canning fruit. Process Biochem. 2013;48(5–6):912–919. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2013.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Narvaiz P, Lescano G, Kairiyama E. Irradiation of almonds and cashew nuts. LWT-Food SciTechnol. 1992;25:232–235. [Google Scholar]

- Nasehi SM, Ansari S. Removal of dark colored compounds from date syrup using activated carbon: a kinetic study. J food Eng. 2012;111(3):490–495. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2012.02.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raikos V, He N, Helen H, Viren R. Antioxidant properties of a yogurt beverage enriched with salal (Gaultheria shallon) berries and blackcurrant (Ribesnigrum) pomace during cold storage. Beverages. 2019;5(2):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rajurkar NS, Samdani KG. Effect of gamma irradiation on antioxidant activity of Amoorarohitaka. J RadioanalNuclChem. 2012;93(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan BR (2000) Storage stability and utilization of date syrup. 1st Mansoura conference for food & dairy science and technology

- Rodríguez R, Jaramillo S, Rodríguez G, Espejo JA, Guillén R, Fernández-Bolaños J, Heredia A, Jiménez A. Antioxidant activity of ethanolic extracts from several asparagus cultivars. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:5212–5217. doi: 10.1021/jf050338i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Pérez C, Quirantes-Piné R, Contreras MM, Uberos J, Fernández-Gutiérrez A, Segura-Carretero A. Assessment of the stability of proanthocyanidins and other phenolic compounds in cranberry syrup after gamma-irradiation treatment and during storage. Food Chem. 2015;174:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama FMM. The use of some natural sweeteners in ice cream manufacture. J Dairy Sci. 2004;32:355–366. [Google Scholar]

- Stone HH, Sidel J, Oliver S, Woolsey A, Singleton RC. Sensory evaluation by quantitative descriptive analysis. Food Technol. 1974;28(11):24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor T, Fasina O, Bell L. Physical properties and consumer liking of cookies prepared by replacing sucrose with tagatose. J Food Sci. 2008;73:145–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrico D, Tam J, Fuentes S, Gonzalez VC, Frank DR. D-Tagatose as a sucrose substitute and its effect on the physico-chemical properties and acceptability of strawberry-flavored yogurt. Foods. 2019;8(256):1–18. doi: 10.3390/foods8070256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troller JA, Christian JHB. Water activity and food. London: Academic Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wang HY, Qian H, Yao WR. Melanoidins produced by the Maillard reaction structure and biological activity. Food Chem. 2001;128(3):573–584. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.03.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Shu Q, Wang Z, Xia Y. Effect of gamma irradiation on starch viscosity and physico-chemical properties of different rice. RadiatPhysChem. 2002;65:79–86. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary files.