Abstract

This secondary analysis reports the survival outcome in patients with EGFR variant-positive non–small-cell lung cancer who had a body mass index that was higher or lower than 24.

Evidence of the synergistic association between epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)–tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and metformin hydrochloride has been controversial, with conflicting results reported from phase 2 trials.1,2 Several reasons have been cited for the lack of consistent results, including differences in patient demographic characteristics (ie, brain metastases), genetic background, dose of metformin used (500 mg vs 1000 mg twice a day), and study design. One factor that was not evaluated was whether the benefit from metformin was dependent on body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared). This parameter seemed particularly relevant given that previous studies found that the salutary effect of metformin on cancer was observed only in patients with a high BMI.3

Methods

This post hoc secondary analysis used data from a previously published, prospective, phase 2 randomized clinical trial (RCT).1 The trial (NCT03071705), along with this analysis, received approval from the Scientific and Bioethical Committees of the Instituto Nacional de Cancerología. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. We followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Briefly, the trial included patients with EGFR (OMIM 131550) variant-positive non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). These patients were randomly assigned to receive treatment with EGFR-TKIs only (as per the National Consensus of Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer guidelines4) or concomitant treatment with EGFR-TKIs plus metformin 500 mg twice a day (Supplement 1). A certified nutritionist (J.G.T.) retrieved anthropometric variables from the trial data. Using the median BMI (24) of trial participants as the cutoff, we stratified patients into those with a high BMI (≥24) and those with a low BMI (<24). Race and ethnicity were not collected for this study given that it was conducted in Mexico where racial information is not collected in protocols.

Statistical significance was set at P < .05 using a 2-tailed test. All analyses were performed with SPSS for Mac, version 20 (IBM Corp).

Results

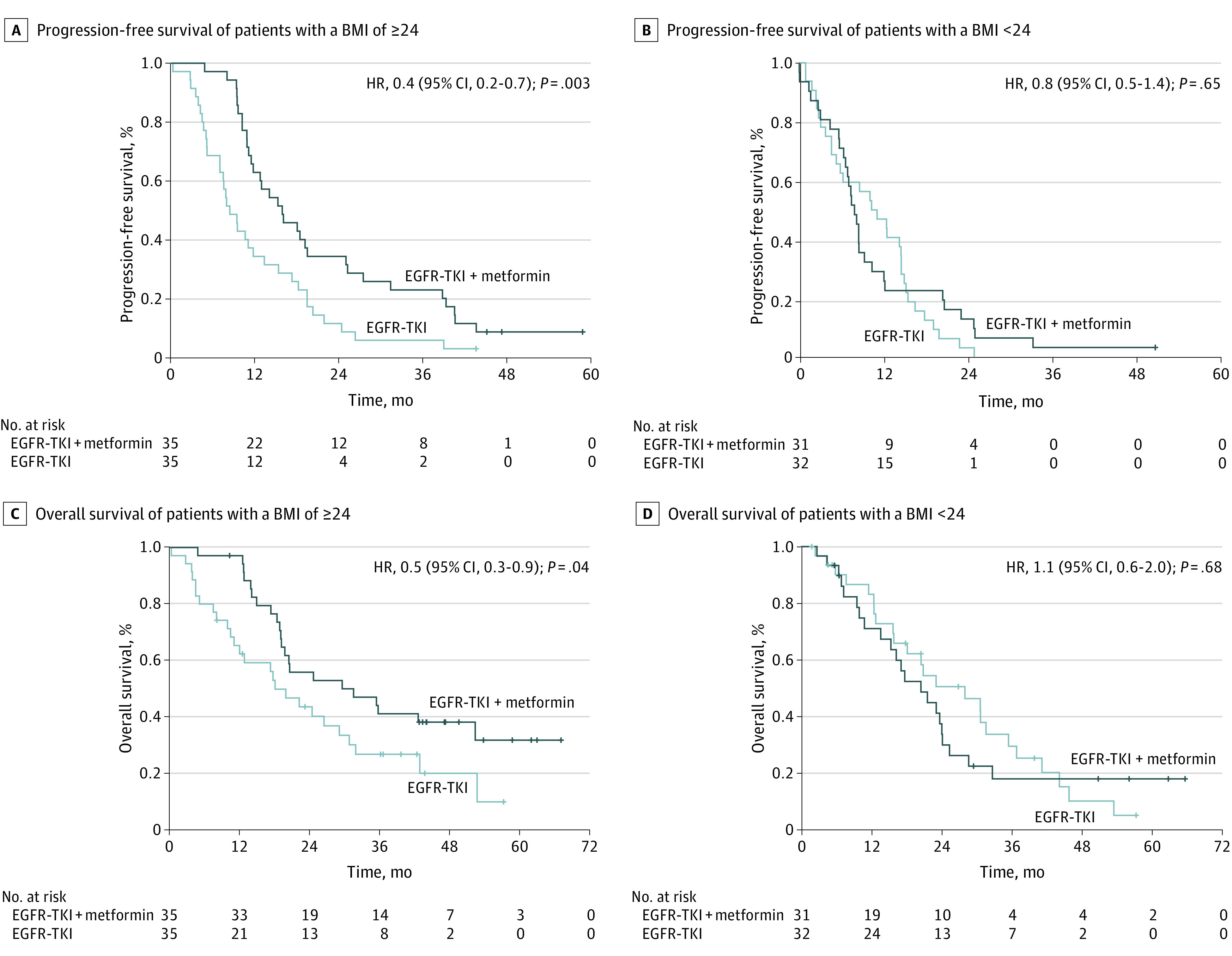

A total of 133 patients (mean [SD] age, 59.39 [13.07] years; 86 female [64.7%] and 47 male [35.3%] individuals) had complete information and were included in the analysis. Overall progression-free survival (PFS) was 10.54 (95% CI, 8.92-12.17) months. Patients who had a BMI of 24 or higher (n = 70 [52.6%]) had an improved PFS from the addition of metformin to EGFR-TKIs, which was independent from other factors, compared with those who received EGFR-TKIs only (15.83 [95% CI, 9.93-21.73] months vs 8.34 [95% CI, 6.09-10.59] months; hazard ratio [HR]: 0.47 [95% CI, 0.28-0.78]; P = .003). This result was not found in patients with a BMI lower than 24 (n = 63 [47.4%]) who were randomized to EGFR-TKIs plus metformin vs EGFR-TKIs only (7.88 [95% CI, 6.60-9.16] months vs 10.31 [95% CI, 4.98-15.64] months; P = .65) (Figure, A and B).

Figure. Survival Outcomes According to Body Mass Index.

BMI indicates body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Similarly, patients with a BMI lower than 24 did not show improved overall survival (OS) from the addition of metformin to EGFR-TKIs compared with those who received EGFR-TKIs only (20.46 [95% CI, 12.90-28.03] months vs 27.99 [95% CI, 16.21-39.76] months; P = .68). However, patients with a BMI of 24 or higher showed significantly greater OS from EGFR-TKIs plus metformin vs EGFR-TKIs only (31.44 [95% CI, 10.28-52.60] months vs 18.00 [95% CI, 11.31-24.70] months; P = .04). The addition of metformin in patients with a BMI of 24 or higher was independently associated with a prolonged OS (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.31-0.98; P = .04) (Table; Figure, C and D).

Table. Univariate and Multivariate Analyses of Factors Associated With Progression-Free Survival and Overall Survival in Patients With a Body Mass Index of 24 or Higher.

| Variable | No. of participants (%) | Median (95% CI), mo | P value | Univariate HR (95% CI) | P value | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progression-free survival | 70 (100) | 11.69 (9.17-14.22) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| CNS metastases | |||||||

| Without metastases | 43 (61.4) | 15.83 (9.08-22.59) | .04 | 1.69 (1.02-2.80) | .04 | 1.57 (0.94-2.61) | .08 |

| With metastases | 27 (38.6) | 10.54 (8.26-12.83) | NA | NA | |||

| Liver metastases | |||||||

| Without metastases | 66 (94.3) | 11.69 (7.47-15.91) | .01 | 3.42 (1.21-9.69) | .02 | 4.96 (1.69-14.58) | .004 |

| With metastases | 4 (5.7) | 3.48 (0.0-9.95) | NA | NA | |||

| Treatment group | |||||||

| EGFR-TKI only | 35 (50.0) | 8.34 (6.09-10.59) | .003 | 0.47 (0.28-0.78) | .003 | 0.45 (0.27-0.75) | .002 |

| EGFR-TKI plus metformin | 35 (50.0) | 15.83 (9.93-21.73) | NA | NA | |||

| Overall survival | 70 (100) | 22.14 (13.02-31.27) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| CNS metastases | |||||||

| Without metastases | 43 (61.4) | 31.80 (20.44-43.16) | .001 | 2.59 (1.44-4.68) | .002 | 2.41 (1.39-4.53) | .002 |

| With metastases | 27 (38.6) | 14.85 (9.44-20.25) | NA | NA | |||

| Treatment group | |||||||

| EGFR-TKI only | 35 (50.0) | 18.00 (11.31-24.70) | .04 | 0.55 (0.31-0.98) | .04 | 0.55 (0.31-0.98) | .04 |

| EGFR-TKI plus metformin | 35 (50.0) | 31.44 (10.28-52.60) | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Discussion

Use of metformin as an antitumor drug is not currently recommended because of conflicting results from clinical trials in patients with NSCLC.1,2 A recent meta-analysis found that the addition of metformin to NSCLC therapy significantly improved OS (HR, 0.74) and PFS (HR, 0.81), although the meta-analysis included studies involving patients with and without diabetes.1,5 When considering RCTs in patients without diabetes who had NSCLC, Li et al2 found that adding metformin to gefitinib did not improve PFS or OS for patients in China. In contrast to the findings from Li et al,2 results from another RCT showed a significant improvement in PFS and OS, although the study was not powered to detect OS.1

The conflicting results could be related to anthropometric differences, which were marked between Asian and Hispanic populations (overweight rate, 64.1% in Mexico vs 33.8% in China).6 The influence of BMI on the salutary effects of metformin for patients with NSCLC has been reported.3 In a study that included 434 patients with stage I NSCLC who were undergoing lobectomy, the authors identified a significant association between use of metformin and better survival outcomes exclusively in patients with a BMI higher than 25.3 The authors concluded that a high BMI might sensitize patients to the antitumor effects of metformin, and therefore the benefit would be circumscribed to this specific population.3 Given the considerable differences in overweight and obesity rates between the Mexican and Chinese populations, it is plausible that the differences in both study results were partially caused by a discrepancy in population BMI.

Limitations of this study included its post hoc design and the exclusion of patients owing to incomplete data. Therefore, the results should be prospectively validated.

Trial Protocol.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Arrieta O, Barrón F, Padilla MS, et al. Effect of metformin plus tyrosine kinase inhibitors compared with tyrosine kinase inhibitors alone in patients with epidermal growth factor receptor-mutated lung adenocarcinoma: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(11):e192553. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li L, Jiang L, Wang Y, et al. Combination of metformin and gefitinib as first-line therapy for nondiabetic advanced NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations: a randomized, double-blind phase II trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(23):6967-6975. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yendamuri S, Barbi J, Pabla S, et al. Body mass index influences the salutary effects of metformin on survival after lobectomy for stage I NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(12):2181-2187. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arrieta O, Guzmán-de Alba E, Alba-López LF, et al. National consensus of diagnosis and treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Article in Spanish. Rev Invest Clin. 2013;65(suppl 1):S5-S84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arrieta O, Varela-Santoyo E, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, et al. Metformin use and its effect on survival in diabetic patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:633. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2658-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ritchie H, Roser M. Obesity. Accessed December 3, 2021. https://ourworldindata.org/obesity

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.

Data Sharing Statement