Key Points

Question

Do the sensitivity and specificity of the 2021 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) lung cancer screening eligibility criteria differ by race from other established lung cancer screening criteria?

Findings

This study of 912 patients with lung cancer and 1457 controls without lung cancer found that the sensitivity of the 2021 USPSTF criteria was better than that of the 2013 USPSTF criteria but worse than that of the 2012 modification of the model from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCOm2012), and the specificity of the 2021 USPSTF criteria was worse than that of the 2013 USPSTF criteria and PLCOm2012. While the 2013 USPSTF criteria selected more White cases and excluded more African American cases, there was no racial disparity in sensitivity or specificity with the 2021 USPSTF criteria and PLCOm2012.

Meaning

This study suggests that the 2021 USPSTF guideline changes improve on earlier, fixed screening criteria for lung cancer, broadening eligibility and reducing racial disparity in access to screening.

Abstract

Importance

In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) broadened its age and smoking pack-year requirement for lung cancer screening.

Objectives

To compare the 2021 USPSTF lung cancer screening criteria with other lung cancer screening criteria and evaluate whether the sensitivity and specificity of these criteria differ by race.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study included 912 patients with lung cancer and 1457 controls without lung cancer enrolled in an epidemiology study (INHALE [Inflammation, Health, Ancestry, and Lung Epidemiology]) in the Detroit metropolitan area between May 15, 2012, and March 31, 2018. Patients with lung cancer and controls were 21 to 89 years of age; patients with lung cancer who were never smokers and controls who were never smokers were not included in these analyses. Statistical analysis was performed from August 31, 2020, to April 13, 2021.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The study assessed whether patients with lung cancer and controls would have qualified for lung cancer screening using the 2013 USPSTF, 2021 USPSTF, and 2012 modification of the model from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCOm2012) screening criteria. Sensitivity was defined as the percentage of patients with lung cancer who qualified for screening, while specificity was defined as the percentage of controls who did not qualify for lung cancer screening.

Results

Participants included 912 patients with a lung cancer diagnosis (493 women [54%]; mean [SD] age, 63.7 [9.5] years) and 1457 control participants without lung cancer at enrollment (795 women [55%]; mean [SD] age, 60.4 [9.6] years). With the use of 2021 USPSTF criteria, 590 patients with lung cancer (65%) were eligible for screening compared with 619 patients (68%) per the PLCOm2012 criteria and 445 patients (49%) per the 2013 USPSTF criteria. With the use of 2013 USPSTF criteria, significantly more White patients than African American patients with lung cancer (324 of 625 [52%] vs 121 of 287 [42%]) would have been eligible for screening. This racial disparity was absent when using 2021 USPSTF criteria (408 of 625 [65%] White patients vs 182 of 287 [63%] African American patients) and PLCOm2012 criteria (427 of 625 [68%] White patients vs 192 of 287 [67%] African American patients). The 2013 USPSTF criteria excluded 950 control participants (65%), while the PLCOm2012 criteria excluded 843 control participants (58%), and the 2021 USPSTF criteria excluded 709 control participants (49%). The 2013 USPSTF criteria excluded fewer White control participants than African American control participants (514 of 838 [61%] vs 436 of 619 [70%]). This racial disparity is again absent when using 2021 USPSTF criteria (401 of 838 [48%] White patients vs 308 of 619 [50%] African American patients) and PLCOm2012 guidelines (475 of 838 [57%] White patients vs 368 of 619 [60%] African American patients).

Conclusions and Relevance

This study suggests that the USPSTF 2021 guideline changes improve on earlier, fixed screening criteria for lung cancer, broadening eligibility and reducing the racial disparity in access to screening.

This study compares the 2021 US Preventive Services Task Force lung cancer screening criteria with other lung cancer screening criteria and evaluates whether the sensitivity and specificity of these criteria differ by race.

Introduction

In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) broadened its lung cancer screening criteria to include adults aged 50 to 80 years with a 20 pack-year smoking history and who are either currently smoking or quit within the past 15 years.1 These criteria replaced the 2013 USPSTF recommendation2 (individuals aged 55-80 years with a 30 pack-year history), which was based mainly on the landmark National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) showing mortality benefit.3 However, NLST participants were predominantly White (90%), resulting in screening inclusion criteria vulnerable to missing certain underrepresented groups.

African American individuals tend to have a lower smoking pack-year history4 but still have the same or higher lung cancer risk than their White counterparts.5,6,7 African American individuals are also at risk for lung cancer at a younger age; the mean age at diagnosis is earlier for African American individuals than for White individuals.8,9 The results of the 2013 USPSTF guidelines in the Southern Community Cohort Study showed a lower percentage of African American smokers qualifying for screening compared with White smokers, mainly owing to the smoking pack-years requirement.10 Broader fixed criteria11 and the use of predictive model risk-based criteria have been proposed as an approach to better include those at high risk and address racial disparities in eligibility.12

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) introduced the NCCN group 2 criteria, which include patients older than 50 years, a smoking history of more than 20 pack-years, and at least 1 additional lung cancer risk factor.11 Compared with the NLST criteria, the NCCN group 2 guidelines were able to capture an additional 26% of patients who would otherwise not qualify for screening, while still maintaining a similar rate of screening positivity.13 However, the study did not evaluate the outcomes by race. The 2021 USPSTF guidelines are similar to the NCCN group 2 guidelines, except for requiring that smokers are either currently smoking or have quit within the past 15 years, but no additional lung cancer risk factors are required.

The dichotomous nature of fixed criteria based on smoking history and age alone may miss other important risk factors, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), family history, and personal history of cancer that are better accounted for by prediction model criteria. The 2012 modification of the model from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCOm2012) model is the most studied prediction model,14 to our knowledge, and was recommended by the NCCN in 2018 as an alternative guideline for the enrollment of patients into lung cancer screening if they do not fulfill the fixed criteria.11 Compared with the 2013 USPSTF criteria, the PLCOm2012 model was found to reduce the eligibility disparity between races, with increased sensitivity for African American individuals15; however, it requires a more comprehensive set of clinical measures to estimate risk, some of which are not readily available from patient electronic health records (ie, education status). Furthermore, risk probabilities must be dichotomized based on a risk threshold to determine screening eligibility.

With the lower age requirement of 50 years and lower smoking pack-year requirement of 20 pack-years, we evaluated the 2021 USPSTF criteria compared with the broader fixed criteria in NCCN group 2 (which has the same age and smoking pack-year requirement) and predictive model risk-based criteria using the PLCOm2012 criteria. Testing this new guideline in a real-world setting is crucial to assessing its sensitivity and specificity outside a research setting. Because the 2021 USPSTF criteria were just published, there has been no study comparing these new criteria for eligibility with the 2013 USPSTF criteria and predictive model risk-based criteria, to our knowledge. The aim of our study is to compare the 2021 USPSTF criteria with the 2013 USPSTF criteria, NCCN group 2 guidelines, and the PLCOm2012 predictive model risk-based criteria and evaluate whether the sensitivity and specificity of these criteria differ by race.

Methods

This study was a retrospective analysis of participants with or without lung cancer in the Detroit metropolitan area who were initially recruited for the INHALE (Inflammation, Health, Ancestry, and Lung Epidemiology) study. Detailed characteristics of the INHALE study participants have been published previously.16 In brief, patients with lung cancer were enrolled at the Karmanos Cancer Institute or Henry Ford Health System within 12 months of diagnosis, between May 15, 2012, and March 31, 2018, at Karmanos Cancer Institute and between May 15, 2012, and November 26, 2014, at Henry Ford Health System. Volunteer controls were enrolled either from the general metropolitan Detroit area or from Henry Ford Health System’s primary care patient population during this same time period. Patients with lung cancer and controls were 21 to 89 years of age and were able to complete a chest computed tomography scan. In addition, controls never had surgical removal of any portion of either lung or received a diagnosis of lung cancer and had health insurance (in the event that medical follow-up was required based on a clinical finding on the computed tomography scan or spirometry). Patients with lung cancer who were never smokers and controls who were never smokers were not included in these analyses. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation. Participants completed an interview and a low-dose chest computed tomography scan. Interview data included demographic information (age and race), clinical measures (body mass index and history of cancer), environmental exposures (asbestos and diesel fumes), and detailed smoking history. Educational level was ascertained via interview data as well (highest grade of school completed). Patients with lung cancer and controls also completed pulmonary function tests with either spirometry at the time of enrollment or, for some patients unable to complete spirometry at the time of interview, pulmonary function test results were abstracted from medical records around the time of diagnosis. Relevant characteristics of patients with lung cancer (disease stage and histologic characteristics) were either abstracted from medical record data or ascertained from the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System (MDCSS) registry. The MDCSS registry was also used to identify control participants who subsequently developed lung cancer. The Wayne State University and Henry Ford Health System institutional review boards approved the procedures used in collecting and processing participant information. This study followed the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) reporting guideline.

Lung Cancer Screening Criteria

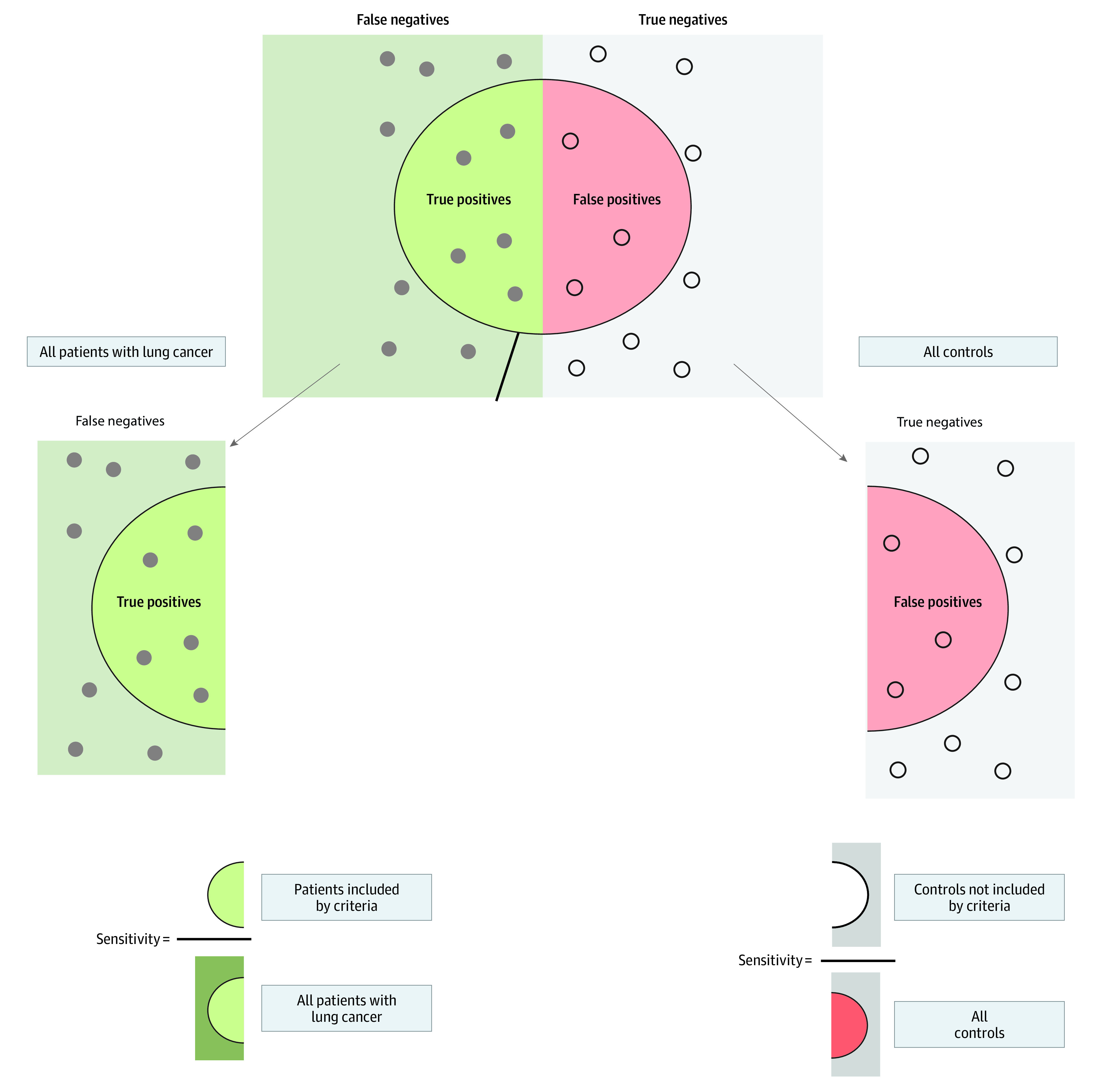

The patients with lung cancer and controls were used to assess the ability of the 2013 USPSTF criteria,2 NCCN group 2 criteria,11 2021 USPSTF criteria,1 and PLCOm201212 screening criteria to include patients with lung cancer and exclude patients without lung cancer. A risk threshold of more than 1.51% per 6 years was used to determine eligibility under the PLCOm2012 model.17 Because we did not have a large prospective cohort of individuals followed up over time, we used a set of patients with known lung cancer to calculate sensitivity. Similarly, a set of participants without lung cancer (controls) was used to calculate specificity. The Figure illustrates this process.18 eTable 1 in the Supplement describes the different screening criteria used for this comparison. Because the 2021 USPSTF criteria had similar age and pack-year requirements as the NCCN group 2 criteria but lacked the risk factor criteria, we further assessed the association of the addition of these risk factors with the sensitivity and specificity of the 2021 USPSTF guidelines. The lung cancer risk factors assessed were self-reported history of COPD, family history of lung cancer, and personal history of cancer. All analyses were also stratified by race.

Figure. Use of Separate Cohorts of Patients With Lung Cancer and Controls to Evaluate the Sensitivity and Specificity of Various Lung Cancer Screening Criteria18.

Long-term Follow-up of the Control Group

This was not a longitudinal study; however, members of the control group who resided in the metropolitan Detroit area could be monitored for lung cancer diagnoses through linkage with the MDCSS registry. Beginning 12 months after enrollment, controls were periodically linked with MDCSS through March 9, 2021, for the development of lung cancer. A total of 32 members of the control group subsequently received a diagnosis of new lung cancer. A new cancer diagnosis was counted only if it was made after 12 months of enrollment. Otherwise, the participants would be included as patients with lung cancer. Controls were enrolled between July 1, 2012, and October 31, 2016, and received a diagnosis between February 1, 2014, and September 1, 2020, with a median of 45 months from enrollment to diagnosis. This subset of controls was evaluated separately to determine how many patients would qualify for screening based on these criteria.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed from August 31, 2020, to April 13, 2021. Descriptive data were expressed as frequencies and percentages for categorical data and as mean (SD) values for the continuous measures. Sensitivity was defined as the percentage of patients with lung cancer who qualified for screening based on a particular set of criteria, while specificity was defined as the percentage of controls who did not qualify for lung cancer screening. Homogeneity of sensitivity (or specificity) by race was evaluated using the χ2 test. Data analysis was performed using R, version 4.0.4 (R Group for Statistical Computing). All P values were from 2-sided tests and results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

Participants included 912 patients with a lung cancer diagnosis (493 women [54%]; mean [SD] age, 63.7 [9.5] years) and 1457 controls without lung cancer at enrollment (795 women [55%]; mean [SD] age, 60.4 [9.6] years) (Table 1). Of the 912 patients with lung cancer, 625 (69%) were White, and 287 (31%) were African American; White patients had a mean (SD) age of 63.9 (9.6) years, and African American patients had a mean (SD) age of 63.2 (9.3) years. Most White patients with lung cancer and most African American patients with lung cancer were aged 60 to 69 years (233 [37%] and 101 [35%], respectively). Only 74 White patients with lung cancer (12%) and 29 African American patients with lung cancer (10%) were younger than 50 years or 80 years or older. Compared with African American patients with lung cancer, White patients with lung cancer had significantly higher mean (SD) pack-years (49.0 [29.6] vs 37.0 [24.0]) of exposure, and a higher proportion of White patients had 30 or more pack-years of exposure (468 [75%] vs 160 [56%]), although the African American patients with lung cancer had a significantly higher percentage of current smokers (156 [54%] vs 266 [43%]; P < .001). In terms of risk factors for lung cancer, African American patients with lung cancer had a significantly lower rate of self-reported COPD (86 [30%] vs 230 [37%]), personal history of cancer (41 [14%] vs 157 [25%]), and family history of cancer (61 [21%] vs 175 [28%]) than White patients with lung cancer. Cardiovascular comorbidity (stroke, congestive heart failure, or arrhythmia) was present in 175 White patients with lung cancer (28%) and 63 African American patients with lung cancer (22%).

Table 1. Description of Current or Former Smokers With Lung Cancer in the Inflammation, Health, Ancestry, and Lung Epidemiology Study.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White (n = 625 [69%]) | African American (n = 287 [31%]) | ||

| Age, y | |||

| <50 | 46 (7) | 17 (6) | .19 |

| 50-59 | 157 (25) | 94 (33) | |

| 60-69 | 233 (37) | 101 (35) | |

| 70-79 | 161 (26) | 63 (22) | |

| ≥80 | 28 (5) | 12 (4) | |

| Mean (SD) | 63.9 (9.6) | 63.2 (9.3) | .26 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 288 (46) | 131 (46) | .91 |

| Female | 337 (54) | 156 (54) | |

| BMI | |||

| <18.5 | 25 (4) | 17 (6) | .33 |

| 18.5-24.9 | 222 (36) | 109 (38) | |

| 25.0-29.9 | 211 (34) | 100 (35) | |

| ≥30.0 | 167 (27) | 61 (21) | |

| Mean (SD) | 26.7 (5.8) | 26.2 (6.0) | .17 |

| Smoking pack-years | |||

| ≥30 | 468 (75) | 160 (56) | <.001 |

| 20-29 | 73 (12) | 51 (18) | |

| 10-19 | 50 (8) | 59 (21) | |

| <10 | 34 (5) | 17 (6) | |

| Mean (SD) | 49.0 (29.6) | 37.0 (24.0) | <.001 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Former | 359 (57) | 131 (46) | .001 |

| Current | 266 (43) | 156 (54) | |

| Quit time, y (former smokers) | |||

| <15 | 147 (41) | 30 (23) | <.001 |

| ≥15 | 212 (59) | 101 (77) | |

| Mean (SD) | 14.6 (13.6) | 9.3 (13.0) | <.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Cardiovascular diseasea | 175 (28) | 63 (22) | .05 |

| COPD | 230 (37) | 86 (30) | .04 |

| Diabetes | 98 (18) | 64 (22) | .02 |

| Hypertension | 305 (49) | 195 (68) | <.001 |

| Personal history of cancer | |||

| No | 468 (75) | 246 (86) | <.001 |

| Yes | 157 (25) | 41 (14) | |

| Family history of cancer | |||

| No | 450 (72) | 226 (79) | .04 |

| Yes | 175 (28) | 61 (21) | |

| Educational level | |||

| High school or less | 320 (51) | 181 (67) | <.001 |

| Greater than high school | 305 (49) | 107 (33) | |

| Histologic characteristics | |||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 137 (23) | 75 (26) | .01 |

| Small cell carcinoma | 102 (17) | 27 (10) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 322 (53) | 163 (57) | |

| NSCLC (other) | 45 (8) | 20 (7) | |

| Unknown or missing | 19 | 2 | |

| Lung cancer stage | |||

| I | 123 (20) | 81 (28) | .03 |

| II | 67 (11) | 35 (12) | |

| III | 148 (25) | 69 (24) | |

| IV | 266 (44) | 101 (35) | |

| Missing | 21 | 1 | |

| PLCOm2012 risk score, mean (SD) | 0.05 (0.06) | 0.05 (0.06) | .68 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NSCLC, non–small cell lung cancer; PLCOm2012, 2012 modification of the model from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial.

Cardiovascular disease: stroke, arrhythmia, and congestive heart failure

The control group consisted of 838 White individuals (58%) and 619 African American individuals (43%), with a mean (SD) age of 61.1 (9.7) and 59.5 (9.3) years, respectively (Table 2). Compared with African American controls, White controls again reported a higher mean (SD) number of pack-years of smoking (36.4 [25.9] vs 26.6 [20.3]; P < .001), and a higher proportion of White controls had 30 or more pack-years of exposure (470 [56%] vs 232 [38%]; P < .001).

Table 2. Description of Current or Former Smokers Who Were White or African American Controls in the Inflammation, Health, Ancestry, and Lung Epidemiology Study.

| Characteristic | Controls, No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White (n = 838 [58%]) | African American (n = 619 [43%]) | ||

| Age, y | |||

| <50 | 101 (12) | 82 (13) | .04 |

| 50-59 | 267 (32) | 226 (37) | |

| 60-69 | 307 (37) | 226 (37) | |

| 70-79 | 144 (17) | 73 (12) | |

| ≥80 | 19 (2) | 12 (2) | |

| Mean (SD) | 61.1 (9.7) | 59.5 (9.3) | .002 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 398 (48) | 264 (43) | .08 |

| Female | 440 (53) | 355 (57) | |

| BMI | |||

| <18.5 | 4 (1) | 3 (1) | .13 |

| 18.5-24.9 | 219 (26) | 156 (25) | |

| 25.0-29.9 | 297 (35) | 189 (31) | |

| ≥30.0 | 318 (38) | 271 (44) | |

| Mean (SD) | 28.8 (5.8) | 29.9 (6.9) | .002 |

| Smoking pack-years | |||

| ≥30 | 470 (56) | 232 (38) | <.001 |

| 20-29 | 146 (17) | 128 (21) | |

| 10-19 | 122 (15) | 136 (22) | |

| <10 | 100 (12) | 123 (20) | |

| Mean (SD) | 36.4 (25.9) | 26.6 (20.3) | <.001 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Former | 467 (56) | 196 (32) | <.001 |

| Current | 371 (44) | 423 (68) | |

| Quit time, y (former smokers) | |||

| <15 | 229 (49) | 116 (59) | .02 |

| ≥15 | 238 (51) | 80 (41) | |

| Mean (SD) | 16.9 (13.3) | 13.7 (11.9) | .002 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Cardiovascular diseasea | 137 (16) | 84 (14) | .14 |

| COPD | 196 (23) | 120 (19) | .07 |

| Diabetes | 121 (14) | 128 (21) | .002 |

| Hypertension | 346 (41) | 380 (61) | <.001 |

| Personal history of cancer | |||

| No | 694 (83) | 560 (91) | <.001 |

| Yes | 144 (17) | 59 (10) | |

| Family history of cancer | |||

| No | 693 (83) | 525 (85) | .31 |

| Yes | 145 (17) | 94 (15) | |

| Educational level | |||

| High school or less | 240 (29) | 282 (46) | <.001 |

| Greater than high school | 598 (71) | 337 (54) | |

| PLCOm2012 risk score, mean (SD) | 0.03 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.07) | .87 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PLCOm2012, 2012 modification of the model from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial.

Cardiovascular disease: stroke, arrhythmia, and congestive heart failure.

Sensitivity of Criteria

If the patients with lung cancer were used to evaluate sensitivity, then 590 (65%) would have been eligible for screening using the 2021 USPSTF guidelines, but the PLCOm2012 guidelines increased that number to 619 (68%) (P = .04) (Table 3). The 2013 USPSTF criteria and the NCCN group 2 criteria would have resulted in 445 (49%) and 563 (62%) of the patients with lung cancer, respectively, to be eligible for screening. When racial subgroups were compared, the 2013 USPSTF criteria selected 324 of 625 White patients (52%), which was significantly more than the 121 of 287 African American patients (42%) selected (P = .007). This racial disparity is still present when using the NCCN group 2 criteria (417 of 625 [67%] White patients vs 146 of 287 [51%] African American patients; P < .001). The use of either the 2021 USPSTF criteria or the PLCOm2012 criteria mitigated this racial gap between White and African American patients (2021 USPSTF criteria: 408 of 625 [65%] White patients vs 182 of 287 [63%] African American patients; PLCOm2012 criteria: 427 of 625 [68%] White patients vs 192 of 287 [67%] African American patients).

Table 3. Sensitivity of NCCN and Risk Model Prediction Estimates for Screening Eligibility Among Patients With Lung Cancer in the Inflammation, Health, Ancestry, and Lung Epidemiology Study.

| Model | Patients, No. (%) | White vs African American patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 912) | White (n = 625) | African American (n = 287) | RR (95% CI) | P value | |

| NLST | 412 (45) | 298 (48) | 114 (40) | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | .03 |

| USPSTF 2013 | 445 (49) | 324 (52) | 121 (42) | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) | .007 |

| NCCN group 2 | 563 (62) | 417 (67) | 146 (51) | 1.3 (1.2-1.4) | <.001 |

| USPSTF 2021 | 590 (65) | 408 (65) | 182 (63) | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | .64 |

| PLCOm2012 ≥1.51% | 619 (68) | 427 (68) | 192 (67) | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) | .73 |

Abbreviations: NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NLST, National Lung Screening Trial; PLCOm2012, 2012 modification of the model from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial; RR, relative risk; USPSTF, US Preventive Services Task Force.

Specificity of Criteria

If the control group is used to evaluate specificity, then the 2013 USPTF guidelines excluded the most individuals (950 of 1457 [65%]), which decreased to 860 of 1457 (59%) using the NCCN group 2 guidelines (Table 4). The PLCOm2012 model excluded 843 of 1457 individuals (58%), while the 2021 USPSTF criteria excluded fewer individuals (709 of 1457 [49%]). Racial disparity was present when using the 2013 USPSTF and NCCN group 2 criteria, with fewer White individuals excluded compared with African American individuals (2013 USPSTF critera: 514 of 838 [61%] White individuals vs 436 of 619 [70%] African American individuals; P = .009; NCCN group 2 criteria: 463 of 838 [55%] White individual vs 397 of 619 [64%] African American individuals; P < .001). No racial differences in eligibility were seen when using the 2021 USPSTF criteria (401 of 838 [48%] White individuals vs 308 of 619 [50%] African American individuals; P = .51) or the PLCOm2012 guidelines (475 of 838 [57%] White individuals vs 368 of 619 [60%] African American individuals; P = .32).

Table 4. Specificity of NCCN and Risk Model Prediction Estimates for Screening Eligibility in White (N = 838) and African American (N = 619) Controls in the Inflammation, Health, Ancestry, and Lung Epidemiology Study.

| Model | Controls, No. (%) | White vs African American controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 1457) | White (n = 838) | African American (n = 619) | RR (95% CI) | P value | |

| NLST | 978 (67) | 534 (64) | 444 (72) | 0.9 (0.8-1.0) | .002 |

| USPSTF 2013 | 950 (65) | 514 (61) | 436 (70) | 0.9 (0.8-0.9) | .009 |

| NCCN group 2 | 860 (59) | 463 (55) | 397 (64) | 0.9 (0.8-0.9) | .001 |

| USPSTF 2021 | 709 (49) | 401 (48) | 308 (50) | 1.0 (0.8-1.1) | .51 |

| PLCOm2012 ≥1.51% | 843 (58) | 475 (57) | 368 (60) | 1.0 (0.9-1.0) | .32 |

Abbreviations: NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NLST, National Lung Screening Trial; PLCOm2012, 2012 modification of the model from the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial; RR, relative risk; USPSTF, US Preventive Services Task Force.

Addition of Lung Cancer Risk Factors to USPSTF 2021 Guidelines

The addition of lung cancer risk factors to the 2021 USPSTF criteria was associated with a reduction in sensitivity (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Selection of patients with lung cancer decreased to 26% (241 of 912) with the addition of a COPD history, 14% (123 of 912) with the addition of a personal history of cancer, and 17% (153 of 912) with the addition of a family history of lung cancer. Requiring any of the 3 risk factors was associated with the selection of 41% of the patients with lung cancer (370 of 912) for screening. The addition of these risk factors was also associated with an exacerbation of the racial disparity in eligibility, with fewer African American patients being eligible compared with White patients: addition of a COPD history (55 of 287 [19%] vs 186 of 625 [30%]; P < .001), personal history of cancer (27 of 287 [9%] vs 96 of 625 [15%]; P = .02), and any of the 3 risk factors (94 of 287 [33%] vs 276 of 625 [44%]; P = .001).

Follow-up of the Control Group

Of the 1457 ever smokers in the control group who were followed up longitudinally, 32 developed lung cancer more than 12 months after enrollment. If the 2021 USPSTF guidelines were used, then 24 of the controls (75%) would have been eligible for screening compared with 19 controls (59%) using the PLCOm2012 model.

Discussion

This study described the real-world sensitivity and specificity of the 2021 USPSTF lung cancer screening guidelines compared with other established lung cancer screening criteria. As expected, broader inclusion criteria increased sensitivity, but at the cost of decreased specificity. These guidelines effectively eliminated the racial disparity in eligibility seen with the previous fixed-criteria models of the NLST and 2013 USPSTF guidelines and the NCCN group 2 guidelines. In our study, the sensitivity and specificity of the 2021 USPSTF guidelines are close to those of the predictive model–based PLCOm2012 criteria but are much more straightforward to use in a clinical setting.

As seen in this study and described by others, African American individuals developing lung cancer tend to be younger and have fewer smoking pack-years than White individuals.4,7 Consistent with this finding, our study showed that lowering the age and smoking criteria successfully bridged the gap in racial disparity without the inclusion of other lung cancer risk factors. Reported lung cancer risk factors, such as COPD, personal history of cancer, and family history of lung cancer, may also vary by race, which may explain why the NCCN group 2 guidelines dichotomizing patients using risk factor criteria failed to bridge the gap in racial disparity regarding eligibility. The sensitivity and specificity of the NCCN group 2 guidelines fall somewhere between the NLST and 2013 USPSTF guidelines (most restrictive) and the 2021 USPSTF guidelines (least restrictive). Nonetheless, the NCCN group 2 guidelines are more similar to the NLST guidelines with regard to the presence of racial disparity in selection criteria.

The PLCOm2012 criteria for eligibility assign a risk score that includes race in the model. African American race is given a higher score than White race, which may explain the superior sensitivity and specificity of the PLCOm2012 criteria compared with the 2021 USPSTF criteria and the associated reduction in the racial disparity in eligibility. It is unfortunate that the superior prediction model–based criteria were left out during the development of the 2021 USPSTF criteria because of a lack of agreement on the threshold for screening.14 The USPSTF evidence review also cited fixed NLST population-based studies that showed similar false discovery rates (96.0%-97.9%) between the PLCOm2012 criteria and the NLST and 2013 USPSTF criteria.12,19,20 Nonetheless, the representation of African American individuals in those study cohorts was limited. Our real-world evaluation of these screening criteria showed a large gap between the NLST and 2013 USPSTF criteria and the PLCOm2012 guidelines in terms of eligibility, with the NLST and 2013 USPSTF criteria being more specific but less sensitive than the PLCOm2012 guidelines in our study participants ranging in age from 21 to 89 years. Our large age range does put the fixed screening criteria at a disadvantage, especially because age is a main selection criterion; however, only 11% of patients with lung cancer in INHALE (N = 103) fell outside any of the screening criteria age ranges (<50 years or ≥80 years). The large age range was used because this study is an exploration of lung cancer screening eligibility in adults. Hence, we included individuals aged 21 to 89 years rather than restrict ourselves to the current screening guideline age criteria.

The International Lung Screening Trial is an ongoing prospective cohort study comparing the accuracy and effectiveness of the 2013 USPSTF criteria with accuracy and effectiveness of the PLCOm2012 risk greater than 1.51% criteria.21 Preliminary analysis showed that the PLCOm2012 criteria had a better positive predictive value compared with the 2013 USPSTF criteria (1.9% vs 1.6%).22 With the change to the 2021 USPSTF guidelines’ broader criteria, our study suggests that the 2021 USPSTF criteria will have an even lower positive predictive value compared with the predictive model risk-based criteria.

Because this was a study of patients who did not receive lung cancer screening, the predominant stage of the lung cancer cases at diagnosis was stage IV, as is seen in the general population. At the national level, the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program database (1973-2015) found 18%, 24%, 48%, and 10% of lung cancers present as local, regional, distant, and unstaged, respectively, which is similar to our study.23

Because lung cancer screening has been covered by private and Medicare insurance, the uptake of screening has increased but was still only at 5% in 2018.24 Patient barriers to screening are mainly lack of awareness, poor perception, cost concerns, and limited access to screening centers.25 On the other hand, clinicians’ unfamiliarity with the screening guidelines, difficulty in determining patient eligibility, challenges of sharing decision-making, and skepticism regarding the evidence for screening are also associated with poor screening uptake. The comorbid conditions of patients that restrict their surgical candidacy also potentially limit eligibility for screening. However, the 2021 USPSTF guidelines lowered the age and smoking criteria, which allows for more patients with fewer comorbid conditions and are more likely to be fit for curative surgical resection of lung cancer. Nonetheless, the broadening of criteria improves sensitivity at the cost of lowering specificity. A lower specificity means that fewer cases of lung cancer are being detected for a given sample size, which reduces the cost-effectiveness of the screening and increases unnecessary workup for patients who end up never developing lung cancer.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. One inherent limitation is that the study was retrospective. Few lung cancers were diagnosed among our relatively small control group, which was not followed up with an additional 2 annual computed tomography scans. Owing to the lack of a large prospective cohort of individuals followed up over time, we used 2 separate sets of participants (patients with lung cancer and controls) to calculate the sensitivity and specificity, respectively. Ultimately, a large prospective trial with good racial representation is needed to provide data on the benefits of screening African American individuals to allow for the development of better guidelines.

Conclusions

The 2021 USPSTF guideline improves on earlier, fixed screening criteria for lung cancer and broadens eligibility to include more African American individuals. The predictive model risk-based criteria using PLCOm2012 still has higher sensitivity and specificity in selecting those who will most benefit from lung cancer screening, although its implementation remains difficult.

eTable 1. Comparison Between the Different Lung Cancer Screening Criteria

eTable 2. Sensitivity of Modified NCCN With Additional Factors From PLCOm2012 Risk Model for Determining Screening Eligibility in INHALE White (N=625) and African American (N=287) Lung Cancer Cases

References

- 1.Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(10):962-970. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):330-338. doi: 10.7326/M13-2771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. ; National Lung Screening Trial Research Team . Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395-409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross KC, Dempsey DA, St Helen G, Delucchi K, Benowitz NL. The influence of puff characteristics, nicotine dependence, and rate of nicotine metabolism on daily nicotine exposure in African American smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(6):936-943. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinsky PF. Racial and ethnic differences in lung cancer incidence: how much is explained by differences in smoking patterns? (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17(8):1017-1024. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0038-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haiman CA, Stram DO, Wilkens LR, et al. Ethnic and racial differences in the smoking-related risk of lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(4):333-342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiscella K, Winters P, Farah S, Sanders M, Mohile SG. Do lung cancer eligibility criteria align with risk among Blacks and Hispanics? PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0143789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robbins HA, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Shiels MS. Age at cancer diagnosis for Blacks compared with Whites in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(3):dju489. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanner NT, Gebregziabher M, Hughes Halbert C, Payne E, Egede LE, Silvestri GA. Racial differences in outcomes within the National Lung Screening Trial: implications for widespread implementation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(2):200-208. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201502-0259OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aldrich MC, Mercaldo SF, Sandler KL, Blot WJ, Grogan EL, Blume JD. Evaluation of USPSTF lung cancer screening guidelines among African American adult smokers. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(9):1318-1324. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood DE, Kazerooni EA, Baum SL, et al. Lung cancer screening, version 3.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(4):412-441. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tammemägi MC, Katki HA, Hocking WG, et al. Selection criteria for lung-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(8):728-736. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKee BJ, Hashim JA, French RJ, et al. Experience with a CT screening program for individuals at high risk for developing lung cancer. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12(2):192-197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonas DE, Reuland DS, Reddy SM, et al. Screening for Lung Cancer With Low-Dose Computed Tomography: An Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Synthesis No. 198. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2021. AHRQ publication 20-05266-EF-1. Accessed April 18, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK568573/ [PubMed]

- 15.Pasquinelli MM, Tammemägi MC, Kovitz KL, et al. Risk prediction model versus United States Preventive Services Task Force lung cancer screening eligibility criteria: reducing race disparities. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(11):1738-1747. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz AG, Lusk CM, Wenzlaff AS, et al. Risk of lung cancer associated with COPD phenotype based on quantitative image analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(9):1341-1347. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tammemägi MC, Church TR, Hocking WG, et al. Evaluation of the lung cancer risks at which to screen ever- and never-smokers: screening rules applied to the PLCO and NLST cohorts. PLoS Med. 2014;11(12):e1001764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walber. Precision and recall. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed September 3, 2021. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Precisionrecall.svg

- 19.Ten Haaf K, Jeon J, Tammemägi MC, et al. Risk prediction models for selection of lung cancer screening candidates: a retrospective validation study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(4):e1002277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber M, Yap S, Goldsbury D, et al. Identifying high risk individuals for targeted lung cancer screening: independent validation of the PLCOm2012 risk prediction tool. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(2):242-253. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim KP, Marshall H, Tammemägi M, et al. ; ILST (International Lung Screening Trial) Investigator Consortium . Protocol and rationale for the International Lung Screening Trial. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(4):503-512. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201902-102OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lam S, Myers R, Ruparel M, et al. PL02.02 lung cancer screenee selection by USPSTF versus PLCOm2012 criteria—interim ILST findings. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(10):S4-S5. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.08.055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu T, Yang X, Huang Y, et al. Trends in the incidence, treatment, and survival of patients with lung cancer in the last four decades. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:943-953. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S187317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fedewa SA, Kazerooni EA, Studts JL, et al. State variation in low-dose computed tomography scanning for lung cancer screening in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(8):1044-1052. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang GX, Baggett TP, Pandharipande PV, et al. Barriers to lung cancer screening engagement from the patient and provider perspective. Radiology. 2019;290(2):278-287. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018180212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Comparison Between the Different Lung Cancer Screening Criteria

eTable 2. Sensitivity of Modified NCCN With Additional Factors From PLCOm2012 Risk Model for Determining Screening Eligibility in INHALE White (N=625) and African American (N=287) Lung Cancer Cases