Abstract

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor containing pyrin domain 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation in podocytes is reportedly associated with enhanced release of exosomes containing NLRP3 inflammasome products from these cells during hyperhomocysteinemia (hHcy). This study examined the possible role of increased exosome secretion during podocyte NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the glomerular inflammatory response. Whether exosome biogenesis and lysosome function are involved in the regulation of exosome release from podocytes during hHcy in mice and upon stimulation of homocysteine (Hcy) in podocytes was tested. By nanoparticle tracking analysis, treatments of mice with amitriptyline (acid sphingomyelinase inhibitor), GW4869 (exosome biogenesis inhibitor), and rapamycin (lysosome function enhancer) were found to inhibit elevated urinary exosomes during hHcy. By examining NLRP3 inflammasome activation in glomeruli during hHcy, amitriptyline (but not GW4869 and rapamycin) was shown to have an inhibitory effect. However, all treatments attenuated glomerular inflammation and injury during hHcy. In cell studies, Hcy treatment stimulated exosome release from podocytes, which was prevented by amitriptyline, GW4869, and rapamycin. Structured illumination microscopy revealed that Hcy inhibited lysosome–multivesicular body interactions in podocytes, which was prevented by amitriptyline or rapamycin but not GW4869. Thus, the data from this study shows that activation of exosome biogenesis and dysregulated lysosome function are critically implicated in the enhancement of exosome release from podocytes leading to glomerular inflammation and injury during hHcy.

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor containing pyrin domain 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation in podocytes plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of hyperhomocysteinemia (hHcy)-induced glomerular disease and end-stage renal disease.1 Nevertheless, NLRP3 inflammasome products such as IL-1β, IL-18, and high mobility group protein B1 may not be released out of podocytes via a classic, Golgi apparatus–mediated delivery pathway, given that the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome mainly occurs in the cytosol. Increasing evidence indicates that the secretion of NLRP3 inflammasome products to the extracellular space may be mediated by exosomes, a subtype of extracellular vesicles.2, 3, 4 As a vital mediator of cell-to-cell communication, exosomes can deliver mRNAs, miRNAs, proteins, and other constituents to acceptor cells to regulate both physiological and pathophysiological processes.5,6 As a biomarker of glomerular diseases, increased exosome release is also implicated in the pathogenesis of glomerular diseases.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Recently, NLRP3 inflammasome activation in podocytes was shown to be associated with robust release of exosomes containing NLRP3 inflammasome products from these cells during hHcy.13 However, how exosome release from podocytes is regulated during hHcy remains unclear. It is imperative to understand whether exosome secretion from podocytes determines NLRP3 inflammasome activation to trigger glomerular inflammation and injury during hHcy.

Exosome release occurs when multivesicular bodies (MVBs) fuse to the plasma membrane and release their contents as exosomes into the extracellular space. Based on previous studies, there are several control points of exosome secretion, including exosome biogenesis, lysosome–MVB interaction, and the fusion of MVB to plasma membrane for exosome release.14 As a neutral sphingomyelinase inhibitor, GW4869 has been widely used to pharmacologically block exosome biogenesis via inhibition of ceramide-mediated inward budding of MVBs.15, 16, 17, 18 In recent studies, lysosome-dependent degradation of MVBs was shown to regulate exosome release from podocytes.13,19, 20, 21, 22 The lysosome–MVB interaction is altered in response to different pathological stimuli such as homocysteine (Hcy) and d-ribose,13,19,22 indicating that enhancement of lysosome function may be a potential therapeutic strategy to prevent robust release of exosomes under pathologic conditions. Recently, it has been reported that inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 enhances the lysosome–MVB interaction and thereby inhibits exosome secretion from smooth muscle cells.23 Moreover, the acid sphingomyelinase (ASM)–ceramide signaling pathway has been found to contribute to NLRP3 inflammasome activation and release of inflammatory exosomes in podocytes during hHcy.13 As an ASM inhibitor, amitriptyline reportedly inhibits both NLRP3 inflammasome activation and exosome release.19,24,25

In the present study, the exosome biogenesis inhibitor GW4869, the lysosome function enhancer rapamycin, and the ASM inhibitor amitriptyline were used to test whether hHcy-induced exosome release from podocytes is determined by exosome biogenesis and lysosome function. In addition, we hypothesized that inhibition of exosome release from podocytes may prevent the development of glomerular inflammation and sclerosis during hHcy.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Podocyte-specific Cre recombinase (Podocre) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory [Bar Harbor, ME; B6.Cg-Tg(NPHS2-Cre)295Lbh/J; stock number 008205]. Smpd1trg mice with the floxed STOP cassette inserted between the beta-actin fusion promoter and mouse cDNA were obtained from Dr. Erich Gulbins (University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany). Smpd1trg/Podocre mice and their littermates are on a C57/BL6 background. Eight-week–old male WT/WT and Smpd1trg/Podocre mice were used in the present study. To speed up the damaging effects of hHcy on glomeruli, all mice were uninephrectomized, as described previously.26 This model has been shown to induce glomerular damage unrelated to the uninephrectomy and arterial blood pressure but specific to hHcy. After allowing 1 week for surgical recovery, mice were fed either a normal diet (ND) or a folate-free (FF) diet (Dyets Inc., Bethlehem, PA) for 8 weeks. At the same time, different groups of mice received amitriptyline at 10 mg/kg,27,28 GW4869 at 1 mg/kg,29,30 or rapamycin at 6 mg/kg31,32 every other day by intraperitoneal injection. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Virginia Commonwealth University.

Immunofluorescent Staining

Frozen slides with mouse kidney tissue were fixed in acetone, blocked, then incubated with primary antibodies, including anti-podocin antibody (1:200; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), anti-desmin antibody (1:200; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), anti-NLRP3 antibody (1:50; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and anti-ASC antibody (1:50; Sigma-Aldrich), overnight at 4°C. Immunofluorescent staining was accomplished by incubating slides with Alexa 488– or Alexa 594–labeled secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) for 1 hour at room temperature.33 Slides were washed, mounted, and observed by using a confocal laser scanning microscope (FluoView FV1000; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Image Pro Plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD) was used to analyze colocalization, which was expressed as the Pearson correlation coefficient.

Immunohistochemistry

Kidneys were embedded with paraffin, and 5 μm sections were cut and mounted onto microscope slides. After heat-induced antigen retrieval, washing with 3% hydrogen peroxide, and 30 minutes of blocking with fetal bovine serum, slides were incubated with anti-CD8 antibody (1:100; Abcam Biotechnology, Cambridge, UK) and anti-F4/80 antibody (1:100; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), and then diluted in phosphate-buffered saline with 4% fetal bovine serum overnight. The sections were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with biotinylated IgG (1:200) for 1 hour at room temperature and then with streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase for 30 minutes. Each kidney section was then stained with diaminobenzidine for 1 minute followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin for 5 minutes. The slides were mounted and observed under a microscope.33

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis

Nanoparticle tracking analysis measurements were performed by using a NanoSight NS300 with NTA3.2 Dev Build 3.2.16 analysis software (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern, UK), equipped with a sample chamber with a 638-nm laser and a Viton Fluoroelastomer O-Ring (Chemours, Wilmington, DE).20, 21, 22 The samples were injected in the sample chamber with sterile syringes (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) until the liquid reached the tip of the nozzle. All measurements were performed at room temperature. The screen gain and camera level settings were 10 and 13, respectively. Each sample was measured by using the standard measurement protocol, 30 seconds with manual shutter and gain adjustments; three measurements of each sample were performed. Three-dimensional figures were exported from the software. Particles sized between 50 and 140 nm were measured. At the end of the 8-week treatment, mice were placed in metabolic cages for 24 hours to collect urine samples. After nanoparticle tracking analysis, we compared urinary exosome excretion of different groups of mice in 24 hours [(urinary exosome concentration × urine volume)/mouse body weight] versus WT/WT-ND.13

Glomerular Morphologic Examination

Fixed kidney tissues were paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with periodic acid-Schiff. Fifty glomeruli per slide were counted under a light microscope and scored as 0 to 4 (0 = no lesion; 1 = sclerosis <25%; 2 = sclerosis of 25% to 50%; 3 = sclerosis of 50% to 75%; and 4 = sclerosis >75%) by an observer (G.L.) who was blinded to treatment groups. Glomerular sclerosis was expressed as the glomerular damage index, which was calculated by the formula [(N1 × 1) + (N2 × 2) + (N3 × 3) + (N4 × 4)]/n. In this formula, N1, N2, N3, and N4 represent the numbers of glomerular damage grades 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, and n represents the total scored number of glomeruli.34

Primary Culture of Murine Podocytes

Primary culture of murine podocytes was performed as described in previous studies.21 Briefly, we infused 20 mL of Dynabeads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) from the abdominal aorta below the renal artery at a flow rate of 7.4 mL/min per gram of kidney. After infusion, kidneys were removed, decapsulated, and dissected. The cortex was minced into small pieces and digested with a mixture of collagenase A (1 mg/mL) and deoxyribonuclease I (0.2 mg/mL) in Hanks’ balanced salt solution at 37°C for 20 minutes with gentle agitation. The digested tissue was placed on a 100 μmol/L strainer and gently pressed with ice-cold medium. After washing the glomeruli with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline six times, the isolated glomeruli was resuspended with beads into 5 mL medium and transferred them into a collagen I–coated culture flask. After 3 days of culture of isolated glomeruli, cellular outgrowths were detached with a trypsin-EDTA solution and transferred to a glass tube. The glass tube was then placed onto a magnetic particle concentrator for 1 minute to remove the glomerular cores and Dynabeads. The supernatant was passed through a 40 μm sieve to remove the remaining glomerular cores. The filtered podocytes were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12) (1:1) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Cansera International, Etobicoke, ON, Canada) supplemented with 0.5% Insulin–Transferrin–Selenium-A liquid media supplement (Invitrogen), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin on a new collagen I–coated flask at 37°C before use in experiments. Podocytes were treated with l-homocysteine, which is considered to be the pathogenic form of Hcy, at a concentration of 40 μmol/L for 24 hours; dose and treatment time were chosen based on previous studies.22,26 Before Hcy stimulation, podocytes were pretreated with amitriptyline (20 μmol/L),27,28 GW4869 (10 μmol/L),29 or rapamycin (100 nmol/L).35

Structured Illumination Microscopy

After treatments followed by fixation, the cells were incubated with rabbit anti-Rab7a antibody (1:100; Abcam Biotechnology) and rat anti–Lamp-1 antibody (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) overnight at 4°C. After slides were washed, Alexa 488–labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and Alexa 594–labeled anti-rat secondary antibody (1:200; Life Technologies) were added to the cell slides and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Slides were then washed, stained with DAPI, and mounted. A Nikon fluorescence microscope in the structured illumination microscopy mode was used to obtain images. Image Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD) was used to analyze colocalization, expressed as the Pearson correlation coefficient.22

Statistical Analysis

SigmaPlot 14.0 was used for statistical analysis of data. All values are expressed as means ± SEM. Significant differences among multiple groups were examined by using analysis of variance followed by a Student-Newman-Keuls test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Regulation of Urinary Exosome Excretion by Pharmacologic Manipulation of Exosome Biogenesis, Lysosome Function, or ASM Activity during hHcy

To test whether exosome release from podocytes is required for the pathogenesis of glomerular inflammation and injury during hHcy, WT/WT and Smpd1trg/Podocre mice were fed either an ND or an FF diet and treated with amitriptyline (ASM inhibitor), GW4869 (exosome biogenesis inhibitor), or rapamycin (lysosome function enhancer) for 8 weeks. According to nanoparticle tracking analysis, hHcy remarkably increased urinary exosome excretion in WT/WT mice, as evidenced by the enlarged peaks of the three-dimensional histogram (Figure 1A). Compared with that in WT/WT mice, urinary exosome excretion in Smpd1trg/Podocre mice was elevated by podocyte-specific overexpression of the Smpd1 gene, an effect that was further amplified by feeding the mice an FF diet. Treatment with amitriptyline, GW4869, and rapamycin prevented hHcy-induced elevation of urinary exosome excretion in both WT/WT and Smpd1trg/Podocre mice. In Figure 1B, summarized data show that hHcy or podocyte-specific ASM overexpression significantly elevated urinary exosome excretion. Compared with vehicle treatment, amitriptyline, GW4869, and rapamycin blocked hHcy-induced enhancement of urinary exosome excretion in mice fed an FF diet.

Figure 1.

Regulation of urinary exosome excretion by pharmacologic manipulation of exosome biogenesis, lysosome function, or acid sphingomyelinase activity during hyperhomocysteinemia. A: Representative images showing the urinary exosome excretion in different groups of mice. B: Summarized data showing the urinary exosome excretion in different groups of mice. n = 6 (B). ∗P < 0.05 versus WT/WT; †P < 0.05 versus normal diet (ND). AMI, amitriptyline; FF, folate-free; GW, GW4869; RAP, rapamycin; Vehl, vehicle.

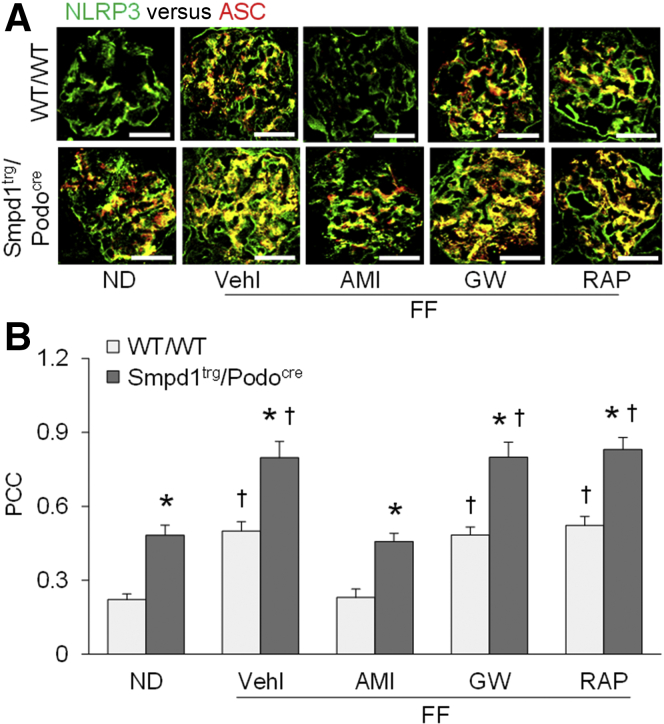

NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation is Not Affected by Pharmacologic Intervention of Exosome Release

To determine whether NLRP3 inflammasome activation in podocytes is affected by pharmacologic intervention of exosome release, NLRP3 inflammasome formation was studied in glomeruli of WT/WT and Smpd1trg/Podocre mice after treatments. Glomeruli of WT/WT mice on the FF diet had an elevated overlay of NLRP3 (green fluorescence) with ASC (red fluorescence) compared with ND-fed WT/WT mice, which was blocked by amitriptyline but not by GW4869 or rapamycin (Figure 2A). Compared with that in WT/WT mice, the formation of NLRP3 inflammasome indicated by the overlay of green fluorescence and red fluorescence was enhanced in glomeruli of Smpd1trg/Podocre mice with podocyte-specific overexpression of the Smpd1 gene, on either diet. Similarly, amitriptyline, but not GW4869 or rapamycin, attenuated NLRP3 inflammasome activation in glomeruli of Smpd1trg/Podocre mice.

Figure 2.

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor containing pyrin domain 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation not affected by pharmacologic intervention of exosome release. A: Representative images showing the colocalization of NLRP3 and ASC in glomeruli of different groups of mice. B: Summarized data showing the colocalization of NLRP3 and ASC in glomeruli of different groups of mice. n = 5 (B). ∗P < 0.05 versus WT/WT; †P < 0.05 versus normal diet (ND). Scale bars = 50 μm (A). AMI, amitriptyline; GW, GW4869; PCC, Pearson correlation coefficient; RAP, rapamycin; Vehl, vehicle.

Quantitation of the colocalization of NLRP3 and ASC by measurement of the Pearson correlation coefficient is presented in Figure 2B. Compared with that in ND-fed WT/WT mice, hHcy remarkably increased the colocalization of NLRP3 and ASC in glomeruli of WT/WT mice fed an FF diet. Podocyte-specific Smpd1 gene overexpression significantly enhanced the colocalization of NLRP3 and ASC in glomeruli of Smpd1trg/Podocre mice on either diet. In both WT/WT and Smpd1trg/Podocre mice, the inhibition of hHcy-induced formation of NLRP3 inflammasome in glomeruli by amitriptyline was significant. GW4869 and rapamycin, however, had no effect on NLRP3 inflammasome activation in glomeruli during hHcy.

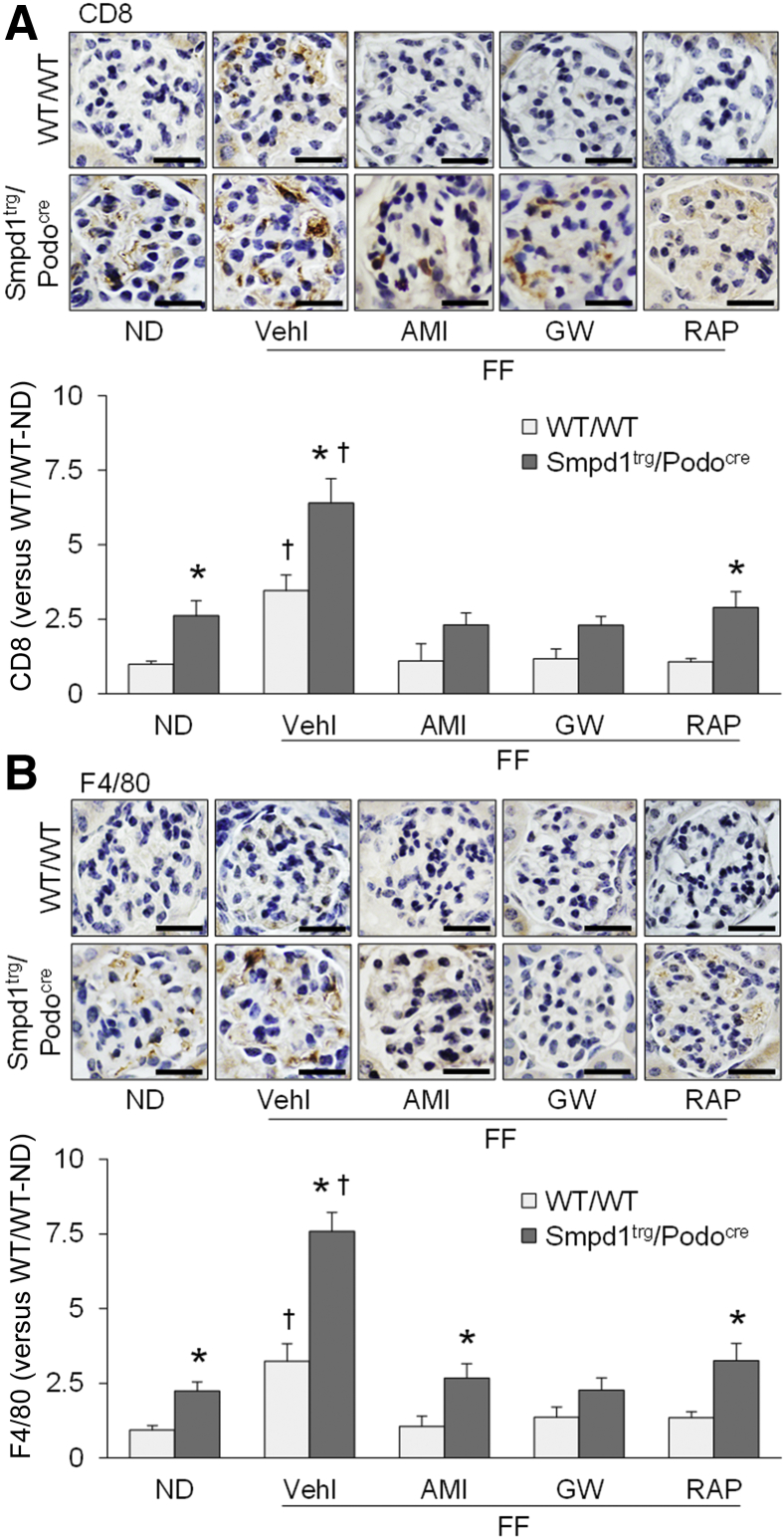

Prevention of hHcy-Induced Immune Cell Infiltration into Glomeruli by Blockade of Exosome Secretion

Immunohistochemistry was used to examine whether hHcy-induced immune cell infiltration into glomeruli was altered by amitriptyline, GW4869, or rapamycin. Immunohistochemical staining of CD8, a T-cell marker, revealed greater infiltration of T cells into glomeruli of WT/WT mice on the FF diet compared with those fed the ND (Figure 3A). The infiltration of T cells into glomeruli was significantly increased by podocyte-specific ASM overexpression in Smpd1trg/Podocre mice on either diet. Compared with that in vehicle-treated mice, hHcy-induced elevation of CD8 staining in glomeruli was not observed in mice treated with amitriptyline, GW4869, or rapamycin. A similar analysis assessed infiltration of macrophages using F4/80, a macrophage marker (Figure 3B). Compared with that in ND-fed WT/WT mice, greater macrophage infiltration was detected in glomeruli of WT/WT mice with hHcy. Podocyte-specific Smpd1 gene overexpression significantly enhanced the infiltration of macrophage in glomeruli of Smpd1trg/Podocre mice on either diet. Nevertheless, amitriptyline, GW4869, and rapamycin prevented hHcy-induced infiltration of macrophage in glomeruli of both WT/WT and Smpd1trg/Podocre mice (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Prevention of hyperhomocysteinemia-induced immune cell infiltration into glomeruli by blockade of exosome secretion. A: Representative images and summarized data showing the immunohistochemical staining of CD8 in glomeruli of different groups of mice. B: Representative images and summarized data showing the immunohistochemical staining of F4/80 in glomeruli of different groups of mice. n = 6 (A and B). ∗P < 0.05 versus WT/WT; †P < 0.05 versus normal diet (ND). Scale bars = 50 μm (A and B). AMI, amitriptyline; GW, GW4869; RAP, rapamycin; Vehl, vehicle.

Abolishment of Glomerular Injury by Inhibition of Exosome Release during hHcy

The glomerular level of podocin (a protein component of the filtration slits of podocytes) was remarkably decreased in WT/WT mice fed an FF diet compared with ND-fed WT/WT mice (Figure 4A). Podocyte-specific ASM overexpression reduced the level of podocin in glomeruli of Smpd1trg/Podocre mice on either diet. However, treatment with amitriptyline, GW4869, or rapamycin blocked the hHcy-induced reduction of podocin expression in glomeruli of both WT/WT and Smpd1trg/Podocre mice. Additionally, WT/WT mice with hHcy had a significantly elevated level of desmin, a marker of podocyte injury, in glomeruli compared with WT/WT mice fed an ND. The glomerular level of desmin was increased by podocyte-specific Smpd1 gene overexpression in Smpd1trg/Podocre mice. The hHcy-induced elevation of glomerular level of desmin, however, was prevented by amitriptyline, GW4869, and rapamycin in both WT/WT and Smpd1trg/Podocre mice (Figure 4B). hHcy increased urinary protein excretion in FF diet–fed WT/WT mice compared with ND-fed WT/WT mice (Figure 5A). Furthermore, WT/WT mice with hHcy exhibited signs of abnormal glomerular morphology, characterized as accumulation of extra matrix, collagen deposition, capillary collapse, and mesangial cell expansion (Figure 5B). Correspondingly, the glomerular damage index of FF diet–fed WT/WT mice was significantly higher than that of the ND-fed WT/WT mice. Proteinuria and glomerular injury were both exaggerated by podocyte-specific ASM overexpression in Smpd1trg/Podocre mice on either diet. However, amitriptyline, GW4869, and rapamycin suppressed these pathologic changes induced by hHcy in both WT/WT and Smpd1trg/Podocre mice.

Figure 4.

Attenuation of podocyte injury by blockade of hyperhomocysteinemia-induced exosome release. A: Representative images and summarized data showing the immunofluorescent staining of podocin in glomeruli of different groups of mice. B: Representative images and summarized data showing the immunofluorescent staining of desmin in glomeruli of different groups of mice. n = 5 (A and B). ∗P < 0.05 versus WT/WT; †P < 0.05 versus normal diet (ND). Scale bars = 50 μm (A and B). AMI, amitriptyline; GW, GW4869; RAP, rapamycin; Vehl, vehicle.

Figure 5.

Abolishment of glomerular damage by inhibition of exosome release during hyperhomocysteinemia. A: Urinary protein excretion of different groups of mice. B: Representative images and summarized data showing the glomerular morphologic changes [periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining] of different groups of mice. n = 6 to 10 (A); n = 3 to 5 (B). ∗P < 0.05 versus WT/WT; †P < 0.05 versus normal diet (ND). Scale bars = 50 μm (B). AMI, amitriptyline; GDI, glomerular damage index; GW, GW4869; RAP, rapamycin; Vehl, vehicle.

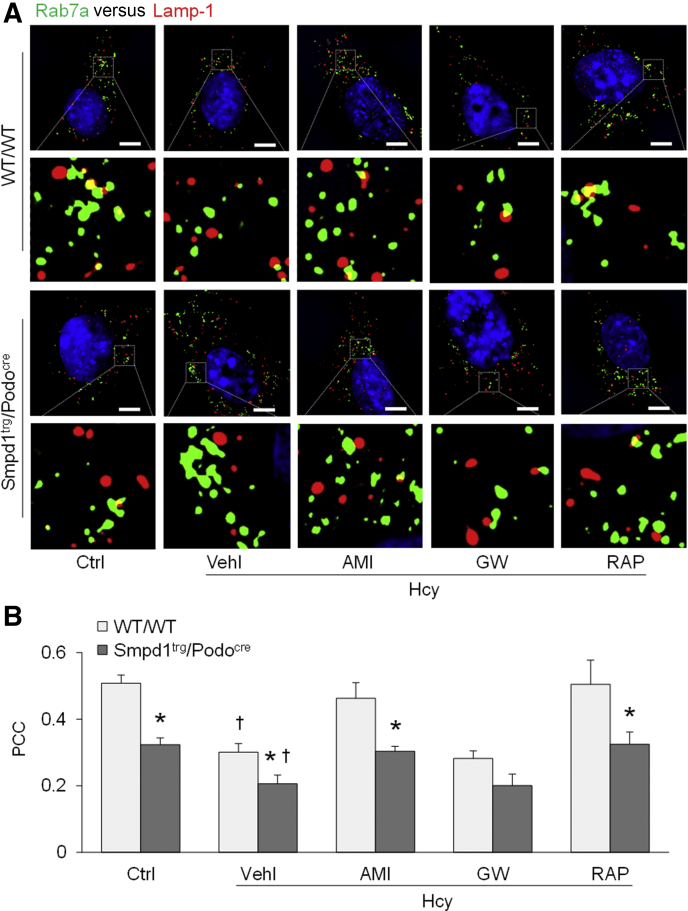

Exosome Release from Podocytes is Determined by Exosome Biogenesis and Lysosome–MVB Interaction

To explore the molecular mechanism by which exosome release from podocytes is regulated, podocytes of WT/WT and Smpd1trg/Podocre mice were isolated and cultured for in vitro studies. Treatment of the cells with Hcy remarkably elevated exosome secretion from WT/WT podocytes to the culture medium (Figure 6). Overexpression of the Smpd1 gene significantly enhanced exosome release from podocytes of Smpd1trg/Podocre mice compared with WT/WT podocytes. Amitriptyline, GW4869, and rapamycin, however, prevented Hcy-induced elevation of exosome secretion from podocytes of both WT/WT and Smpd1trg/Podocre mice. Moreover, structured illumination microscopy was performed to detect lysosome–MVB interaction in podocytes. Under the control condition, greater overlay of Rab7a (MVB marker, green fluorescence) and Lamp-1 (lysosome marker, red fluorescence) was observed in the podocyte cytosol, as shown by the yellow spots in the representative image (Figure 7A). Hcy stimulation decreased the overlay of green fluorescence and red fluorescence in the cytosol of WT/WT podocytes, which was exaggerated by ASM overexpression in podocytes of Smpd1trg/Podocre mice. GW4869 had no effects on Hcy-induced reduction of the lysosome–MVB interaction in the podocyte cytosol. However, amitriptyline and rapamycin recovered the lysosome–MVB interaction in Hcy-treated podocytes of both WT/WT and Smpd1trg/Podocre mice to the level of control podocytes. Quantitation of the colocalization of Rab7a and Lamp-1 by measurement of the Pearson correlation coefficient is presented in Figure 7B. Compared with that in WT/WT podocytes under the control condition, the colocalization of Rab7a and Lamp-1 was remarkably lower in WT/WT podocytes treated with Hcy. ASM overexpression significantly decreased the colocalization of Rab7a and Lamp-1 in podocytes of Smpd1trg/Podocre mice. Hcy-induced reduction of the colocalization of Rab7a and Lamp-1 in podocytes of both WT/WT and Smpd1trg/Podocre mice was not affected by GW4869 but blocked by amitriptyline and rapamycin.

Figure 6.

Elevation of exosome release from podocytes induced by homocysteine (Hcy). A: Representative images showing exosome release from different groups of podocytes. B: Summarized data showing exosome release from different groups of podocytes. n = 5 to 6 (B). ∗P < 0.05 versus WT/WT; †P < 0.05 versus control (Ctrl). AMI, amitriptyline; GW, GW4869; RAP, rapamycin; Vehl, vehicle.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of the lysosome–multivesicular body interaction in podocytes by homocysteine. A: Representative images showing the colocalization of Rab7a and Lamp-1 in different groups of podocytes. Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification below. B: Summarized data showing the colocalization of Rab7a and Lamp-1 in different groups of podocytes. n = 4 (B). ∗P < 0.05 versus WT/WT; †P < 0.05 versus control (Ctrl). Scale bars = 5 μm (A). AMI, amitriptyline; GW, GW4869; PCC, Pearson correlation coefficient; RAP, rapamycin; Vehl, vehicle.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to test whether hHcy-induced exosome release from podocytes is determined by exosome biogenesis and lysosome function. The results showed that hHcy induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation and robust exosome release in podocytes and glomerular inflammation and injury, which were amplified by podocyte-specific Smpd1 gene overexpression. Moreover, this hHcy-stimulated release of exosomes from podocytes was prevented by inhibition of ASM activity (amitriptyline), blockade of exosome biogenesis (GW4869), and enhancement of lysosome function (rapamycin). Meanwhile, amitriptyline attenuated NLRP3 inflammasome activation in podocytes, but GW4869 and rapamycin had no effects on NLRP3 inflammasome. Similar to amitriptyline, both GW4869 and rapamycin inhibited glomerular inflammation and sclerosis even though they failed to interfere with activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in podocytes (Figure 8). These findings indicate that exosome biogenesis and lysosome function determine exosome release from podocytes during hHcy. Without robust exosome release, NLRP3 inflammasome activation in podocytes may not initiate the development of glomerular inflammation and sclerosis during hHcy.

Figure 8.

Exosome biogenesis and lysosome function determine podocyte exosome release and glomerular inflammatory response during hyperhomocysteinemia. When plasma homocysteine (Hcy) levels increase, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor containing pyrin domain 3 inflammasomes in podocytes are activated to produce inflammatory cytokines, which enter the late endosomes that form multivesicular bodies (MVBs). At the same time, lysosomal acid sphingomyelinase (ASM) activity is enhanced to produce ceramide and associated sphingolipids, which inhibit lysosome trafficking and reduce the interactions of lysosomes and MVBs, a process determining the MVB fate. Under such conditions, decreased lysosome degradation of MVBs leads to robust release of MVB contents as exosomes from podocytes. These exosomes, now referred to as inflammatory exosomes, recruit and activate inflammatory cells, leading to glomerular inflammation and sclerosis. Amitriptyline (AMI) attenuates nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor containing pyrin domain 3 inflammasome activation and recovers lysosome function via inhibition of ASM activity. GW4869 (GW) suppresses the function of neutral sphingomyelinase (NSM) to decrease exosome biogenesis. Rapamycin (RAP), as an inhibitor of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), enhances lysosome function, leading to increased lysosome–MVB interaction and decreased exosome release. All treatments attenuate glomerular inflammation and sclerosis during hyperhomocysteinemia. EC, endothelial cell; GBM, glomerular basement membrane.

Previous studies have reported that NLRP3 inflammasome activation in podocytes contributes to podocyte injury, glomerular inflammation, and glomerulosclerosis during hHcy.26,34,36, 37, 38 As a cytosolic multiprotein oligomer, the NLRP3 inflammasome is composed of three major proteins: nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain–like receptor NLRP3, adaptor protein apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC), and caspase-1.1 Following the recognition of danger signals by NLRP3, the aggregation of NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1 leads to the formation of a protein complex in which caspase-1 is activated. In addition to the proteolytic cleavage of IL-1β and IL-18 into biologically active form, the active caspase-1 can produce damage-associated molecular patterns. All these products of the NLRP3 inflammasome can act to initiate local inflammation and induce pyroptosis.39, 40, 41, 42 However, how NLRP3 inflammasome products are released out of podocytes to trigger glomerular inflammation during hHcy remains unclear.

Recently, NLRP3 inflammasome activation in podocytes was shown to be associated with the release of exosomes containing NLRP3 inflammasome products from these cells during hHcy, indicating that exosome secretion may be the molecular mechanism mediating the release of NLRP3 inflammasome products to the extracellular space for triggering of glomerular inflammation.13 Nevertheless, the pathologic role of these inflammatory exosomes in hHcy-induced glomerular inflammation and sclerosis remains poorly understood. To test whether exosome release contributes to glomerular inflammation during hHcy, GW4869 was used to block exosome biogenesis in podocytes. Given that lysosomes can determine MVB fate in podocytes,20,21 rapamycin was also used to enhance lysosome-dependent degradation of MVB for inhibition of exosome release. Moreover, based on the findings that the ASM–ceramide signaling pathway plays an important role in NLRP3 inflammasome activation and exosome release in podocytes during hHcy,13 amitriptyline was used to attenuate both NLRP3 inflammasome activation and exosome release in podocytes via inhibition of ASM activity. The results showed that hHcy induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in glomeruli and increased urinary exosome excretion, which were amplified by podocyte-specific Smpd1 gene overexpression. Moreover, hHcy-induced elevation of urinary exosome excretion was prevented by amitriptyline, GW4869, and rapamycin. However, hHcy-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in glomeruli was only inhibited by amitriptyline but not by GW4869 or rapamycin.

The impact of podocyte-specific Smpd1 gene overexpression and amitriptyline on NLRP3 inflammasome activation and exosome release suggest that the ASM–ceramide signaling pathway contributes to both of these hHcy-induced effects, which is consistent with previous findings.13,43 GW4869, as a neutral sphingomyelinase inhibitor, has been reported to block exosome biogenesis, leading to reduction of exosome release.16 The blockade of hHcy-induced robust release of exosome by rapamycin was consistent with previous findings that the lysosome–MVB interaction determines exosome release.20, 21, 22

To test whether exosome release from podocytes contributes to glomerular inflammation, the infiltration of immune cells into glomeruli during hHcy was evaluated. It was found that hHcy triggered infiltration of T cells and macrophages into glomeruli, which was exaggerated by podocyte-specific Smpd1 gene overexpression, but inhibited by amitriptyline, GW4869, and rapamycin. These findings revealed the critical role of exosome release from podocytes in the development of glomerular inflammation during hHcy. Given that GW4869 and rapamycin inhibited exosome secretion but had no significant effects on NLRP3 inflammasome, the results provide the first evidence that NLRP3 inflammasome activation in podocytes is unable to induce glomerular inflammation without robust release of exosomes from these cells

In previous studies, it has been reported that exosomes can induce the activation of T cells.44, 45, 46, 47 In mice, exosomes released from antigen-primed macrophages have been found to activate T cells on their own.44 Moreover, mature dendritic cells can secrete exosomes to activate T cells in which CD54 and B7 may be importantly involved.45,46 Studies on human T cells show that exosomes from monocyte-derived dendritic cells can stimulate human T cells to produce interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α.47 Based on the molecular constituents, exosomes can switch the phenotype of macrophages either to M1, a classically activated phenotype, or to M2, an alternatively activated phenotype.48 In various types of cancers, tumor cell–derived exosomes have been shown to switch the macrophages to M1 phenotype, leading to enhanced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by macrophages.49, 50, 51 In addition, colorectal cancer cells can secret exosomes to induce the conversion of macrophages from M1 phenotype to M2 phenotype.52 Macrophages stimulated by triple-negative breast cancer cell–derived exosomes display higher expression of CD206, a marker of M2 macrophages, than the expression of NOS2, a marker of M1 macrophages.53 The present study revealed, for the first time, that podocyte-derived exosomes play a critical role in hHcy-induced glomerular inflammation via recruitment of immune cells.

Various approaches were used to determine whether podocyte injury and glomerular damage were altered by manipulation of exosome release in mice with hHcy. It was found that hHcy induced podocyte damage, glomerular sclerosis, and proteinuria, which were amplified by podocyte-specific Smpd1 gene overexpression. Amitriptyline, GW4869, and rapamycin blocked or inhibited these pathologic changes induced by hHcy, indicating that NLRP3 inflammasome activation and robust exosome release are both required for the induction of glomerular injury by hHcy. In the presence of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in podocytes, blockade of exosome secretion from these cells may attenuate the development of podocyte injury and glomerular sclerosis during hHcy.

As an intrarenal cell-to-cell communication mediator, exosomes reportedly contribute to the development of various renal diseases.54 In diabetic mice, podocyte-derived exosomes increased before the onset of albuminuria.55 In some patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and nephrotic syndrome, the elevation of exosome release from podocytes is associated with albuminuria and glomerular degeneration.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 In mice with podocyte-specific Asah1 gene deletion, podocytopathy is associated with a remarkable increase in exosome release from podocytes, indicating that exosomes may contribute to the development of podocytopathy in these mice.21,33 These previous studies suggest that exosomes are importantly implicated in the pathogenesis of glomerular diseases. Recently, Hcy and d-ribose have been shown to induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation and inflammatory exosome release in podocytes.19,22 Although hHcy-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in podocytes is shown to be associated with robust release of exosomes from these cells,13 the pathologic role of these inflammatory exosomes in hHcy-induced glomerular inflammation and injury remains unclear. The present study, for the first time, confirms that robust exosome release from podocytes is essential for the development of glomerular inflammation and injury during hHcy. Targeting exosome release may be a novel therapeutic strategy for glomerular diseases under various pathologic conditions such as hHcy.

Previous studies showed that hHcy enhanced urinary excretion of exosomes containing a podocyte marker and NLRP3 inflammasome products and that this effect was mediated through the ASM–ceramide signaling pathway.13 However, how exosome release from podocytes is enhanced by hHcy or how the ASM–ceramide signaling pathway is involved in the regulation of exosome secretion from podocytes remained unclear. In the present study, podocytes were isolated from WT/WT and Smpd1trg/Podocre mice for exploration of the underlying molecular mechanism. It was found that Hcy stimulation enhanced exosome secretion from podocytes, which was amplified by ASM overexpression. However, amitriptyline, GW4869, and rapamycin blocked the elevation of exosome release from podocytes induced by Hcy. To explore the regulatory mechanism of exosome release from podocytes, lysosome–MVB interaction was studied in these cells. Hcy stimulation impaired the lysosome–MVB interaction in podocytes, which was exaggerated by ASM overexpression. In podocytes treated with Hcy, the reduction of the lysosome–MVB interaction was prevented by amitriptyline and rapamycin but was not affected by GW4869. These findings indicate that hHcy-induced elevation of exosome release from podocytes is attributed to the reduction of the lysosome–MVB interaction in these cells. The ASM–ceramide signaling pathway contributes to hHcy-induced elevation of exosome release from podocytes via regulation of the lysosome–MVB interaction in these cells. Previous studies have shown that ceramide and associated sphingolipids regulate lysosome trafficking and fusion with other vesicles in different cell types.9,56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61 Recently, Hcy was shown to inhibit lysosomal TRPML1 channel activity via enhancement of reactive oxygen species production by NADPH oxidase, which caused less lysosome–MVB interaction and more exosome release in podocytes.22 Given that the ASM–ceramide signaling pathway contributes to reactive oxygen species production by NADPH oxidase,43,62, 63, 64 it is possible that amitriptyline may enhance the lysosome–MVB interaction via inhibition of reactive oxygen species production by NADPH oxidase. As an inhibitor of mammalian target of rapamycin, rapamycin has been reported to inhibit exosome release from neuronal cells and glial cells.65 Moreover, mammalian target of rapamycin reportedly regulates the lysosome–MVB interaction and exosome release in smooth muscle cells.23 The results with rapamycin confirmed the vital role of lysosomes in the regulation of exosome release in podocytes. In contrast to the regulators of lysosome function, GW4869 blocks exosome biogenesis via inhibition of ceramide-mediated inward budding of MVBs from plasma membranes.15, 16, 17, 18 The results with GW4869 indicate that in addition to enhancement of lysosome function, blockade of exosome biogenesis may be another potential therapeutic strategy for inhibition of exosome release from podocytes during hHcy.

In summary, the present study shows that exosome biogenesis and lysosome function determine podocyte exosome release and glomerular inflammatory response during hHcy. The ASM–ceramide signaling pathway contributes to hHcy-induced glomerular inflammation via inhibition of lysosome-MVB interaction and enhancement of exosome release in podocytes. Both enhancement of lysosome function and inhibition of exosome biogenesis can attenuate exosome release from podocytes during hHcy. These results indicate that enhancement of exosome biogenesis and dysregulation of lysosome function importantly contribute to robust exosome release from podocytes during hHcy and that targeting the regulatory pathway of exosome release from podocytes may be a novel therapeutic strategy for hHcy-induced glomerular inflammation and injury.

Author Contributions

D.H. conceptualized the study, established methods, formally analyzed data, performed experiments, wrote the original draft, and visualized data; G.L. established methods, formally analyzed data, performed experiments, and wrote (reviewed and edited) the manuscript; O.M.B., and Y.Z. formally analyzed data and performed experiments; N.L. and J.K.R. wrote (reviewed and edited) the manuscript; and P.-L.L. conceptualized the study, provided resources, wrote (reviewed and edited the manuscript), supervised the study, and acquired funding.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants DK054927 and DK120491 (P.-L.L.).

Disclosures: None declared.

References

- 1.Martinon F., Mayor A., Tschopp J. The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:229–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colombo M., Raposo G., Théry C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:255–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schorey J.S., Harding C.V. Extracellular vesicles and infectious diseases: new complexity to an old story. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:1181–1189. doi: 10.1172/JCI81132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubartelli A., Cozzolino F., Talio M., Sitia R. A novel secretory pathway for interleukin-1 beta, a protein lacking a signal sequence. EMBO J. 1990;9:1503–1510. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eitan E., Suire C., Zhang S., Mattson M.P. Impact of lysosome status on extracellular vesicle content and release. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;32:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Balkom B.W., Pisitkun T., Verhaar M.C., Knepper M.A. Exosomes and the kidney: prospects for diagnosis and therapy of renal diseases. Kidney Int. 2011;80:1138–1145. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erdbrügger U., Le T.H. Extracellular vesicles in renal diseases: more than novel biomarkers? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:12–26. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015010074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hara M., Yanagihara T., Kihara I., Higashi K., Fujimoto K., Kajita T. Apical cell membranes are shed into urine from injured podocytes: a novel phenomenon of podocyte injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:408–416. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee H., Han K.H., Lee S.E., Kim S.H., Kang H.G., Cheong H.I. Urinary exosomal WT1 in childhood nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:317–320. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-2035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lytvyn Y., Xiao F., Kennedy C.R., Perkins B.A., Reich H.N., Scholey J.W., Cherney D.Z., Burger D. Assessment of urinary microparticles in normotensive patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2017;60:581–584. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-4190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ståhl A.L., Johansson K., Mossberg M., Kahn R., Karpman D. Exosomes and microvesicles in normal physiology, pathophysiology, and renal diseases. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34:11–30. doi: 10.1007/s00467-017-3816-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tkaczyk M., Baj Z. Surface markers of platelet function in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2002;17:673–677. doi: 10.1007/s00467-002-0865-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang D., Li G., Zhang Q., Bhat O.M., Zou Y., Ritter J.K., Li P.-L. Contribution of podocyte inflammatory exosome release to glomerular inflammation and sclerosis during hyperhomocysteinemia. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2021;1867:166146. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2021.166146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hessvik N.P., Llorente A. Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75:193–208. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2595-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kosaka N., Iguchi H., Yoshioka Y., Takeshita F., Matsuki Y., Ochiya T. Secretory mechanisms and intercellular transfer of microRNAs in living cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:17442–17452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.107821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X., Huang W., Liu G., Cai W., Millard R.W., Wang Y., Chang J., Peng T., Fan G.-C. Cardiomyocytes mediate anti-angiogenesis in type 2 diabetic rats through the exosomal transfer of miR-320 into endothelial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;74:139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulshreshtha A., Ahmad T., Agrawal A., Ghosh B. Proinflammatory role of epithelial cell-derived exosomes in allergic airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1194–1203, 1203.e1-14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J., Liu K., Liu Y., Xu Y., Zhang F., Yang H., Liu J., Pan T., Chen J., Wu M., Zhou X., Yuan Z. Exosomes mediate the cell-to-cell transmission of IFN-alpha-induced antiviral activity. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:793–803. doi: 10.1038/ni.2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong J., Bhat O.M., Li G., Dempsey S.K., Zhang Q., Ritter J.K., Li W., Li P.-L. Lysosomal regulation of extracellular vesicle excretion during d-ribose-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in podocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2019;1866:849–860. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li G., Huang D., Hong J., Bhat O.M., Yuan X., Li P.-L. Control of lysosomal TRPML1 channel activity and exosome release by acid ceramidase in mouse podocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2019;317:C481–C491. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00150.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li G., Huang D., Bhat O.M., Poklis J.L., Zhang A., Zou Y., Kidd J., Gehr T.W.B., Li P.-L. Abnormal podocyte TRPML1 channel activity and exosome release in mice with podocyte-specific Asah1 gene deletion. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2021;1866:158856. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2020.158856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li G., Huang D., Li N., Ritter J.K., Li P.-L. Regulation of TRPML1 channel activity and inflammatory exosome release by endogenously produced reactive oxygen species in mouse podocytes. Redox Biol. 2021;43:102013. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhat O.M., Yuan X., Kukreja R.C., Li P.-L. Regulatory role of mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in exosome secretion and osteogenic changes in smooth muscle cells lacking acid ceramidase gene. FASEB J. 2021;35:e21732. doi: 10.1096/fj.202100385R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alcocer-Gómez E., de Miguel M., Casas-Barquero N., Núñez-Vasco J., Sánchez-Alcazar J.A., Fernández-Rodríguez A., Cordero M.D. NLRP3 inflammasome is activated in mononuclear blood cells from patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;36:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeon S.-A., Lee E., Hwang I., Han B., Park S., Son S., Yang J., Hong S., Kim C.H., Son J., Yu J.-W. NLRP3 inflammasome contributes to lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behaviors via indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase induction. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20:896–906. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyx065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li G., Chen Z., Bhat O.M., Zhang Q., Abais-Battad J.M., Conley S.M., Ritter J.K., Li P.-L. NLRP3 inflammasome as a novel target for docosahexaenoic acid metabolites to abrogate glomerular injury. J Lipid Res. 2017;58:1080–1090. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M072587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng H., Li C., Kadow S., Henry B.D., Steinmann J., Becker K.A., Riehle A., Beckmann N., Wilker B., Li P.-L., Pritts T., Edwards M.J., Zhang Y., Gulbins E., Grassmé H. Acid sphingomyelinase inhibition protects mice from lung edema and lethal Staphylococcus aureus sepsis. J Mol Med (Berl) 2015;93:675–689. doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1246-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhat O.M., Yuan X., Cain C., Salloum F.N., Li P.-L. Medial calcification in the arterial wall of smooth muscle cell-specific Smpd1 transgenic mice: a ceramide-mediated vasculopathy. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:539–553. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Essandoh K., Yang L., Wang X., Huang W., Qin D., Hao J., Wang Y., Zingarelli B., Peng T., Fan G.-C. Blockade of exosome generation with GW4869 dampens the sepsis-induced inflammation and cardiac dysfunction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:2362–2371. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tabatadze N., Savonenko A., Song H., Bandaru V.V.R., Chu M., Haughey N.J. Inhibition of neutral sphingomyelinase-2 perturbs brain sphingolipid balance and spatial memory in mice. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:2940–2951. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang Y., Hill C.M., Darcy J., Reyes-Ordonez A., Arauz E., McFadden S., Zhang C., Osland J., Gao J., Zhang T., Frank S.J., Javors M.A., Yuan R., Kopchick J.J., Sun L.Y., Chen J., Bartke A. Effects of rapamycin on growth hormone receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E1495–E1503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717065115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen C., Liu Y., Liu Y., Zheng P. mTOR regulation and therapeutic rejuvenation of aging hematopoietic stem cells. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra75. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li G., Kidd J., Kaspar C., Dempsey S., Bhat O.M., Camus S., Ritter J.K., Gehr T.W.B., Gulbins E., Li P.-L. Podocytopathy and nephrotic syndrome in mice with podocyte-specific deletion of the Asah1 gene: role of ceramide accumulation in glomeruli. Am J Pathol. 2020;190:1211–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abais J.M., Xia M., Li G., Gehr T.W., Boini K.M., Li P.-L. Contribution of endogenously produced reactive oxygen species to the activation of podocyte NLRP3 inflammasomes in hyperhomocysteinemia. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;67:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li G., Li C.-X., Xia M., Ritter J.K., Gehr T.W., Boini K., Li P.-L. Enhanced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition associated with lysosome dysfunction in podocytes: role of p62/Sequestosome 1 as a signaling hub. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;35:1773–1786. doi: 10.1159/000373989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xia M., Conley S.M., Li G., Li P.-L., Boini K.M. Inhibition of hyperhomocysteinemia-induced inflammasome activation and glomerular sclerosis by NLRP3 gene deletion. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;34:829–841. doi: 10.1159/000363046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abais J.M., Xia M., Li G., Chen Y., Conley S.M., Gehr T.W.B., Boini K.M., Li P.-L. Nod-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation and podocyte injury via thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) during hyperhomocysteinemia. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:27159–27168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.567537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li G., Xia M., Abais J.M., Boini K., Li P.-L., Ritter J.K. Protective action of anandamide and its COX-2 metabolite against l-homocysteine-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation and injury in podocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;358:61–70. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.233239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen G.Y., Nuñez G. Sterile inflammation: sensing and reacting to damage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:826–837. doi: 10.1038/nri2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lamkanfi M. Emerging inflammasome effector mechanisms. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:213–220. doi: 10.1038/nri2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martinon F., Burns K., Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Srinivasula S.M., Poyet J.-L., Razmara M., Datta P., Zhang Z., Alnemri E.S. The PYRIN-CARD protein ASC is an activating adaptor for caspase-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21119–21122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boini K.M., Xia M., Li C., Zhang C., Payne L.P., Abais J.M., Poklis J.L., Hylemon P.B., Li P.-L. Acid sphingomyelinase gene deficiency ameliorates the hyperhomocysteinemia-induced glomerular injury in mice. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2210–2219. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raposo G., Nijman H.W., Stoorvogel W., Liejendekker R., Harding C.V., Melief C.J., Geuze H.J. B lymphocytes secrete antigen-presenting vesicles. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1161–1172. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hwang I., Shen X., Sprent J. Direct stimulation of naive T cells by membrane vesicles from antigen-presenting cells: distinct roles for CD54 and B7 molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6670–6675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1131852100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Utsugi-Kobukai S., Fujimaki H., Hotta C., Nakazawa M., Minami M. MHC class I-mediated exogenous antigen presentation by exosomes secreted from immature and mature bone marrow derived dendritic cells. Immunol Lett. 2003;89:125–131. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(03)00128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Admyre C., Johansson S.M., Paulie S., Gabrielsson S. Direct exosome stimulation of peripheral human T cells detected by ELISPOT. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1772–1781. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baig M.S., Roy A., Rajpoot S., Liu D., Savai R., Banerjee S., Kawada M., Faisal S.M., Saluja R., Saqib U., Ohishi T., Wary K.K. Tumor-derived exosomes in the regulation of macrophage polarization. Inflamm Res. 2020;69:435–451. doi: 10.1007/s00011-020-01318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jang J.-Y., Lee J.-K., Jeon Y.-K., Kim C.-W. Exosome derived from epigallocatechin gallate treated breast cancer cells suppresses tumor growth by inhibiting tumor-associated macrophage infiltration and M2 polarization. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao M., Zhang J., Chen W., Chen W. M1-like tumor-associated macrophages activated by exosome-transferred THBS1 promote malignant migration in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:143. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0815-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krementz E.T., Kokame G.M. Regional chemotherapy of cancer of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 1966;76:880–892. doi: 10.1288/00005537-196605000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Z., Yang L., Cui Y., Zhou Y., Yin X., Guo J., Zhang G., Wang T., He Q.-Y. Cytoskeleton-centric protein transportation by exosomes transforms tumor-favorable macrophages. Oncotarget. 2016;7:67387–67402. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piao Y.J., Kim H.S., Hwang E.H., Woo J., Zhang M., Moon W.K. Breast cancer cell-derived exosomes and macrophage polarization are associated with lymph node metastasis. Oncotarget. 2018;9:7398–7410. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li G., Kidd J., Li P.-L. Podocyte lysosome dysfunction in chronic glomerular diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1559. doi: 10.3390/ijms21051559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hara M., Yamagata K., Tomino Y., Saito A., Hirayama Y., Ogasawara S., Kurosawa H., Sekine S., Yan K. Urinary podocalyxin is an early marker for podocyte injury in patients with diabetes: establishment of a highly sensitive ELISA to detect urinary podocalyxin. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2913–2919. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2661-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alvarez-Erviti L., Seow Y., Schapira A.H., Gardiner C., Sargent I.L., Wood M.J., Cooper J.M. Lysosomal dysfunction increases exosome-mediated alpha-synuclein release and transmission. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;42:360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cui Y., Luan J., Li H., Zhou X., Han J. Exosomes derived from mineralizing osteoblasts promote ST2 cell osteogenic differentiation by alteration of microRNA expression. FEBS Lett. 2016;590:185–192. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li C.M., Hong S.B., Kopal G., He X., Linke T., Hou W.S., Koch J., Gatt S., Sandhoff K., Schuchman E.H. Cloning and characterization of the full-length cDNA and genomic sequences encoding murine acid ceramidase. Genomics. 1998;50:267–274. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li P.-L., Zhang Y., Abais J.M., Ritter J.K., Zhang F. Cyclic ADP-ribose and NAADP in vascular regulation and diseases. Messenger (Los Angel) 2013;2:63–85. doi: 10.1166/msr.2013.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liebau M.C., Braun F., Höpker K., Weitbrecht C., Bartels V., Müller R.-U., Brodesser S., Saleem M.A., Benzing T., Schermer B., Cybulla M., Kurschat C.E. Dysregulated autophagy contributes to podocyte damage in Fabry’s disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63506. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lorber D. Importance of cardiovascular disease risk management in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2014;7:169–183. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S61438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bao J.-X., Jin S., Zhang F., Wang Z.-C., Li N., Li P.-L. Activation of membrane NADPH oxidase associated with lysosome-targeted acid sphingomyelinase in coronary endothelial cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:703–712. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bao J.-X., Xia M., Poklis J.L., Han W.-Q., Brimson C., Li P.-L. Triggering role of acid sphingomyelinase in endothelial lysosome-membrane fusion and dysfunction in coronary arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H992–H1002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00958.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boini K.M., Zhang C., Xia M., Han W.-Q., Brimson C., Poklis J.L., Li P.-L. Visfatin-induced lipid raft redox signaling platforms and dysfunction in glomerular endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:1294–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Currim F., Singh J., Shinde A., Gohel D., Roy M., Singh K., Shukla S., Mane M., Vasiyani H., Singh R. Exosome release is modulated by the mitochondrial-lysosomal crosstalk in Parkinson’s disease stress conditions. Mol Neurobiol. 2021;58:1819–1833. doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-02243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]