Abstract

Most species in Rosaceae usually need to undergo several years of juvenile phase before the initiation of flowering. After 4–6 years’ juvenile phase, cultivated loquat (Eriobotrya japonica), a species in Rosaceae, enters the reproductive phase, blooms in the autumn and sets fruits during the winter. However, the mechanisms of the transition from a seedling to an adult tree remain obscure in loquat. The regulation networks controlling seasonal flowering are also largely unknown. Here, we report two RELATED TO ABI3 AND VP1 (RAV) homologs controlling juvenility and seasonal flowering in loquat. The expressions of EjRAV1/2 were relatively high during the juvenile or vegetative phase and low at the adult or reproductive phase. Overexpression of the two EjRAVs in Arabidopsis prolonged (about threefold) the juvenile period by repressing the expressions of flowering activator genes. Additionally, the transformed plants produced more lateral branches than the wild type plants. Molecular assays revealed that the nucleus localized EjRAVs could bind to the CAACA motif of the promoters of flower signal integrators, EjFT1/2, to repress their expression levels. These findings suggest that EjRAVs play critical roles in maintaining juvenility and repressing flower initiation in the early life cycle of loquat as well as in regulating seasonal flowering. Results from this study not only shed light on the control and maintenance of the juvenile phase, but also provided potential targets for manipulation of flowering time and accelerated breeding in loquat.

Keywords: flowering time, juvenility, annual flowering, FT, branching, loquat, RAV

Introduction

Flowering is a crucial process required for reproductive success, integrating external and internal signals (Song et al., 2013). This process is energy-consuming and therefore plants need to undergo diverse juvenile periods to accumulate sufficient reserves before flowering (Andrés and Coupland, 2012). For annual plants, such as Arabidopsis, the whole life cycle is limited to several months with a short juvenile phase followed by flowering and fruit setting in the adult phase, and the life cycle ends as fruits become mature (Somerville and Koornneef, 2002). In contrast, the long-lived perennial trees, such as poplar and eucalyptus, have a long juvenile phase that lasts for several years (Missiaggia et al., 2005; Hsu et al., 2006). Although perennial plants bloom annually or seasonally after the initiation of the first flowering, the long juvenile period is time-consuming and needs to be shortened to accelerate breeding and other research programs for economically important perennial plants (Watson et al., 2018).

As a key developmental event of a plant’s life cycle, the juvenile-to-adult transition of both annual Arabidopsis and perennial trees is regulated by gradually decreasing the miR156/157 expressions as well as increasing the expressions of its target genes encoding a set of plant specific SPL (SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE) proteins (Xu et al., 2016; Jia et al., 2017). Commonly, the miR156 levels would decline as the plant age increases, which elevates the expression levels of SPL transcription factors to promote flowering by inducing the expressions of floral integrator genes including FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CO1 (SOC1), APETALA1 (AP1), and LEAFY (LFY) (Wang, 2014; Xu et al., 2018).

The Rosaceae family possesses approximately 90 genera and 3,000 species with several fruit trees like apple, pear, Prunus, and strawberry producing delicious and nutritious fruits; ornamental plants such as rose, Prunus mume and oriental cherry as well as medicinal plants like loquat (also a fruit tree), Potentilla chinensis and hawthorn (Potter et al., 2007; Xiang et al., 2016). The growth habits vary greatly in this family, from herbaceous rosette plants to deciduous or evergreen trees. For example, the herbaceous strawberry could flower in its first season, while woody fruit trees usually need several years to end the juvenile period (Kurokura et al., 2013). FT, a major component of florigen, and its antagonistic homolog TERMINAL FLOWER 1 (TFL1) are vital regulators of plant flowering (Daniel, 2015), and their homologs in Rosaceae have proven to initiate the reproductive phase and regulate seasonal flowering (Kotoda et al., 2010; Kurokura et al., 2013). Overexpression of FT orthologs derived from fruit tree species in Arabidopsis induced its early flowering (Tränkner et al., 2010; Yarur et al., 2016). Currently available studies in fruit trees suggested the conserved role of FT in promoting the floral transition, and additional functions were implied in these studies based on the observations of pleiotropic transgenic phenotypes (Goeckeritz and Hollender, 2021). In some other fruit species such as kiwifruit, the FT orthologs were reported to play a role in maturity regulation and vegetative phenology in addition to flowering (Voogd et al., 2017). As another key flowering integrator, SOC1 was frequently reported to regulate the endodormancy break (Gómez-Soto et al., 2021). In sweet cherry, the PavSOC1 gene was reported to interact with dormancy-associated MADS-box (DAM) genes to co-regulate flower development (Wang J. et al., 2020). In peach (Prunus persica), PpSOC1 has been used as a marker for the timing of endodormancy break (Halász et al., 2021). Meanwhile, efforts have been made to use these genes as targets to shorten the juvenile period and accelerate breeding (Yamagishi et al., 2016; McGarry et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the gene network regulating the initiation of flowering in Rosaceae is still rarely reported, resulting in limited novel gene targets.

Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica) is a subtropical evergreen fruit tree native to China (Su et al., 2021). The seedlings need to undergo 4–6 years of juvenile phase before the first flowering (Zheng et al., 1991). Its deciduous relatives, such as apple and pear, induce inflorescence in early summer, develop flower meristems in autumn, enter endodormancy in late autumn, and finally bloom in the next spring (Kurokura et al., 2013). By contrast, the cultivated loquat induces inflorescence and develops flower in the same year (Jiang et al., 2019), but the process from flowering to fruit setting occurs quickly in the winter season and fruits ripen in spring. The life history and annual growth cycle of cultivated loquat were illustrated in Supplementary Figure 1. As for loquat, previous works from our group and other researchers have identified some activators including EjAP1 (Liu et al., 2013), EdFT and EdFD (Zhang et al., 2016), EjLFY (Liu et al., 2017), EjSOC1 (Jiang et al., 2019), EdCO and EdGI (Zhang et al., 2019) and EjSPL3/4/5/9 (Jiang et al., 2020a), as well as repressors like EjTFL1 (Jiang et al., 2020b) and EjFRI (Chen W. et al., 2020). The functions of these genes were conserved between Arabidopsis and loquat. However, whether these genes or other genes in loquat have any relation with the control or maintenance of juvenility is still unknown. Meanwhile, the pathways of these genes to induce flowering remain to be elucidated.

RELATED TO ABI3 AND VP1 (RAV) family genes, including TEMPRANILLO (TEM), play vital roles in linking photoperiod-, gibberellin- as well as other pathways to control flowering and juvenility in Arabidopsis (Castillejo and Pelaz, 2008; Osnato et al., 2012; Matias-Hernandez et al., 2014). However, it is unknown whether the homologs of RAV modulate flower initiation in long-lived perennial trees. To test this idea, here we cloned two RAV homologs (EjRAV1 and EjRAV2) from E. japonica. EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 turned out to be good biomarkers that maintain juvenility and vegetative stages in loquat with abundant transcripts at these stages and rarely expressed at reproductive stages. In this study, we examined the roles of EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 in the transition from juvenile phase to reproductive phase in loquat, and investigated their functions in seasonal flowering in trees during fruit production. Our work revealed that EjRAV proteins could bind to the CAACA motifs in promoter regions of FT homologs to repress flower signal integration in loquat.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

According to our previous observations, the cultivated loquat trees start flower primordial differentiation and inflorescence formation from late June to July (Liu et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2019). Hence, shoot apical meristem (SAM) observation as well as the collection of SAM and mature leaf samples of “Zaozhong-6,” a main cultivar in China, were performed from 16th May to 8th August in 2018 at the loquat germplasm resource preservation garden (South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China). The samples were collected at around 10:00–11:00 a.m. in every 7 days (except for 23rd May) during this time window. To decipher the correlations of gene expression levels between EjRAV1/2 and other flowering regulating genes for the duration of juvenile phase, mature leaves from 1-year-old seedlings, 2-year-old seedlings, 2-year-old grafted trees and fruit-bearing adult trees (all trees with “Zaozhong-6” background) were collected on 11th July, 2018 (at around 10:00–11:00 a.m.) with three biological replicates from our germplasm resource preservation garden. For each replicate, three mature leaves were randomly collected from one plant and were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Arabidopsis and Nicotiana benthamiana were used for stable and transient genetic transformation, respectively. Columbia-0 (Col-0) ecotype Arabidopsis and N. benthamiana were preserved by our research group, and tem2 (Col-0 background) mutant was purchased from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center1 with a stock number of CS909678. All these plants were planted in a long-day (16 h light/8 h dark) greenhouse at 22°C. The 4-week-old T3 Arabidopsis plants were collected for gene expression assays.

RAV Gene Family Identification in Loquat Genome

The six RAV family protein sequences of Arabidopsis were downloaded from GenBank and used as queries to Blast search for homologs in “Jiefangzhong” loquat genome (Su et al., 2021) using TBtools software with an E-value cutoff at 1e–10, protein identity≥40 and bit score≥100 (Chen C. et al., 2020). Expression level heat maps of the six identified EjRAVs in 10 tissues were drawn based on FPKM values from transcriptome data (available at China National GeneBank database with accession number CNP0001531) using TBtools software (Chen C. et al., 2020). Multiple sequence alignment was performed using ClustalX2. The phylogenetic relationship of the RAV genes was calculated by MEGA5 (Tamura et al., 2011), with the bootstrap values at the branch nodes calculated from 100 replications. The following proteins were used for phylogenetic analysis: AtTEM/EDF1 (NP_173927.1), AtRAV2/EDF2/TEM2 (NP_173927.1), AtE DF3 (NP_189201.1), AtRAV1/EDF4 (NP_172784.1), AtRA V3 (CAA0284621.1), AtRAVL3 (NP_175524.1); CaRAV (AAQ05799.1), CsRAV1 (AEZ02303.1), DkERF32 (QFU8520 5.1), DkERF34 (QFU85207.1), EjRAV1 (QBQ58100.1), EjRAV2 (QBQ58101.1), FaRAV1 (AZL19498.1), FaRAV3 (AZL19 500.1), FaRAV5 (AZL19502.1), FaRAV6 (AZL19503.1), GmRAV (NP_001237600.1), MdRAV1 (MD13G1046100), MdRAV2 (AU Z96416.1), MtRAV1 (XP_003591822.1), MtRAV2 (AES97413.2), MtRAV3 (AES63108.1), NtRAV (NP_001311676.1), OsRAVL1 (ADJ57333.1), OsRAV6 (XP_015624169.1), PtRAV1 (XP_00 2315958.2), PtRAV2 (XP_002311438.2), PtRAV3 (XP_00230 4025.1), SlRAV2 (ABY57635.1). AtDRN-LIKE (NP_173864.1) was selected as an out-group.

RNA Extraction and cDNA Preparation

Total RNA of loquat leaves and Arabidopsis plants were extracted with the EASYspin Plus plant RNA extraction kit (Aidlab, China) under the manufacturers’ instructions. Then, the PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit (TaKaRa, Japan) was used to prepare the first-strand cDNA of all the samples.

Gene Transformation in Arabidopsis

EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 sequences were amplified and cloned into the pGreen-35S vector to construct the pGreen-35S:EjRAV1 and pGreen-35S:EjRAV2 vectors with the primer pairs listed in Supplementary Table 1 using the PrimeSTAR® HS DNA Polymerase (TaKaRa, Japan). The PCR amplicons and linearized vector (digested by HindIII and EcoRI; New England Biolabs, United States) were fused with a Hieff Clone® Plus One Step Cloning Kit (Yeasen Biotech, China). 35S:EjRAV1 and 35S:EjRAV2 vectors were first transformed into the Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101:psoup cells, then floral-dip method was used to transfer overexpression vectors into Arabidopsis as previously described (Henriques et al., 2006).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR Assays

Gene expression levels were analyzed using quantitative real-time PCR as previously done (Su et al., 2019). The specific quantitative primers were designed using the Primer Premier 6.0 software3. EjRPL18 (MH196507) and AtUBQ10 (AL161503) were used as the reference genes for loquat and Arabidopsis gene expression assays. Detailed primer sequence information for all the detected genes were listed in Supplementary Table 1. All the biological samples were detected in triplicates using iTaq™ universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, United States) in the LightCycler480 system (Roche, Sweden).

Transient Expression Assays in Nicotiana benthamiana

The coding regions without stop codon of EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 were fused into pGreen-35S-GFP (green fluorescent protein) with primer pairs listed in Supplementary Table 1. The vectors were then transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101:psoup, GV3101:psoup cells at OD600 = 1.0 were centrifuged at 4,500 g for 5 min, and the pellets were suspended with MMA solution (MES, MgCl2 and Acetosyringone) to OD600 = 0.2 (Hellens et al., 2005). The dilute Agrobacterium cells were then incubated in dark under room temperature for 1 h and finally used to inject into N. benthamiana leaves. The tobacco leaves were incubated in long day greenhouse for 2 days, images of EjRAV1-GFP, EjRAV1-GFP and 35S-GFP were captured with the Observer. D1 fluorescence microscope system (Carl Zeiss, Germany).

The pGreen-0800:EjSOC1 vectors were previously prepared (Jiang et al., 2020a). EjFT1 and EjFT2 promoter sequences were fused into pGreen-0800 vector with primer pairs listed in Supplementary Table 1, and the protocol for pGreen-0800 reporter vector construction was similar to that used in pGreen-35S:EjRAV1 vector preparation. Then, PLACE website4 was used to check the binding sites for RAV proteins on each promoter. The positions of predicted RAV binding sites on these promoters were highlighted in Supplementary Figure 2 and listed in the Supplementary Table 2.

The coding regions of EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 were fused into the pSAK277 vector to construct the effector vector (Hellens et al., 2005) with primer pairs listed in Supplementary Table 1. The effector and reporter vectors were then transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101:psoup cells. Then, the mixed Agrobacterium solution with effector and reporter vectors was injected into N. benthamiana leaves as formerly performed (Hellens et al., 2005). The activities of firefly and renilla dual-luciferase were detected using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay kit (Promega, America) under the instruction of the manufacturers 2–3 days after leaf injection.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

The coding sequences of EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 were cloned into pET28a using primers listed in Supplementary Table 1. The 6 × His-EjRAV recombinant proteins and 6 × His control were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells and induced at OD600 = 0.6∼0.8 by 1 mM isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG), and oscillated for 4 h at 220 rpm (revolutions per minute) after addition of IPTG. The raw induced proteins were then purified with Amylose Magnetic Beads (NEB, United States). Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) assays were performed as previously described (Yu et al., 2020). An EMSA Probe Biotin Labeling Kit (Beyotime, China) was then used to label biotin to the ends of oligonucleotide probes. Excessive unlabeled wild type or mutant probes were used for competition experiments. The probe sequences were listed in Supplementary Table 1. The EMSA assay was performed with an EMSA/Gel Shift kit and detected with a chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Beyotime, China). Ultimately, photos of all the gel shift experiments were taken with a ChimeScope series 3300 mini system (Clinxscience, China).

Yeast One-Hybrid Assays

Yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assays were performed according to the Matchmaker Gold Y1H system user manual (Clontech, America) to detect the binding capacities of EjRAV1/2 to the EjFT promoters. Both EjFT1 and EjFT2 promoters contain five putative RAV binding elements (CAACA motif or CACCTG motif, see in Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2). According to Supplementary Figure 2, four promoter segments containing all the binding motifs were designed for yeast binding assays, and the segment regions were separately inserted into the pAbAi reporter vector to obtain baits. Meanwhile, the CDS of EjRAV1/2 was fused to the pGADT7 vector. Then, the recombinant pGADT7-EjRAV1 or pGADT7-EjRAV2 was transformed into the Y1HGold yeast strain with linearized reporter plasmid pAbAi-proFT1 or pAbAi-proFT2 to further determine the protein–DNA interactions. The primers used in these assays were listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Results

Identification of RAV Family Genes

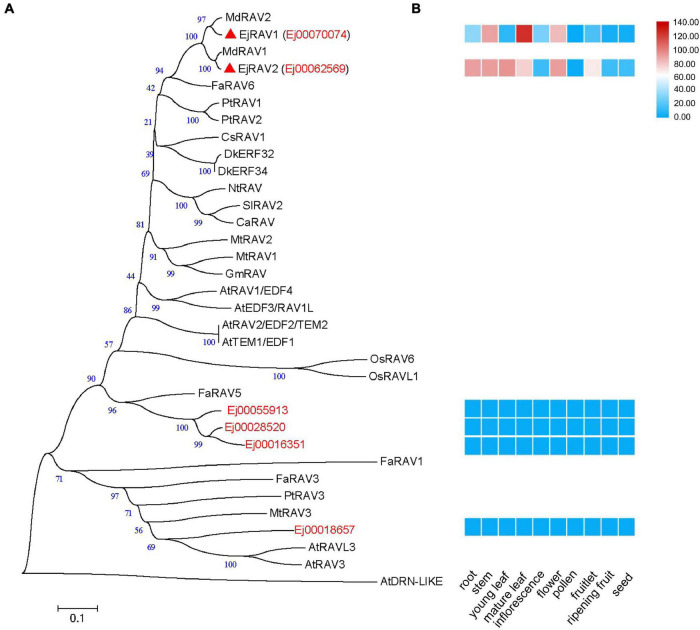

A total of six RAV family genes were identified in the loquat genome (Figure 1A). These genes were clustered into three clades, among which Ej00070074 and Ej00062569 were clustered with four Arabidopsis RAV/TEM genes (RAV1, RAV1-LIKE, RAV2 and RAV2-LIKE), Ej00055913, Ej00028520 and Ej00016351 grouped with FaRAV5, while Ej00018657 clustered into the RAV3 clade. These genes showed different expression patterns. Ej00070074 and Ej00062569 (formerly named as EjRAV1 and EjRAV2) were found to be highly expressed in most of the vegetative tissues while the expression levels of the other four genes were scarcely detected (Figure 1B). The highly expressed EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 were speculated to possibly play a role in repressing flowering or repressing flower bud differentiation in loquat.

FIGURE 1.

A phylogenetic tree and expression heat map of RAV family genes in loquat. (A) A phylogenetic tree containing RAV homologs identified in loquat genome and other species. AtDRN-LIKE was selected as an outer-group. The red triangles indicate candidate RAVs that play role in the transition of reproductive phase in loquat. At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Ca, Capsicum annuum; Cs, Castanea sativa; Dk, Diospyros kaki; Ej, Eriobotrya japonica; Fa, Fragaria ananassa; Gm, Glycine max; Md, Malus domestica; Mt, Medicago truncatula; Nt, Nicotiana tabacum; Os, Oryza sativa; Pt, Populus trichocarpa; Sl, Solanum lycopersicum. (B) Tissue expression patterns of EjRAV family genes based on FPKM values from 10 tissues.

EjRAV1/2 Abundance Negatively Associated With the Annual Flowering Pattern

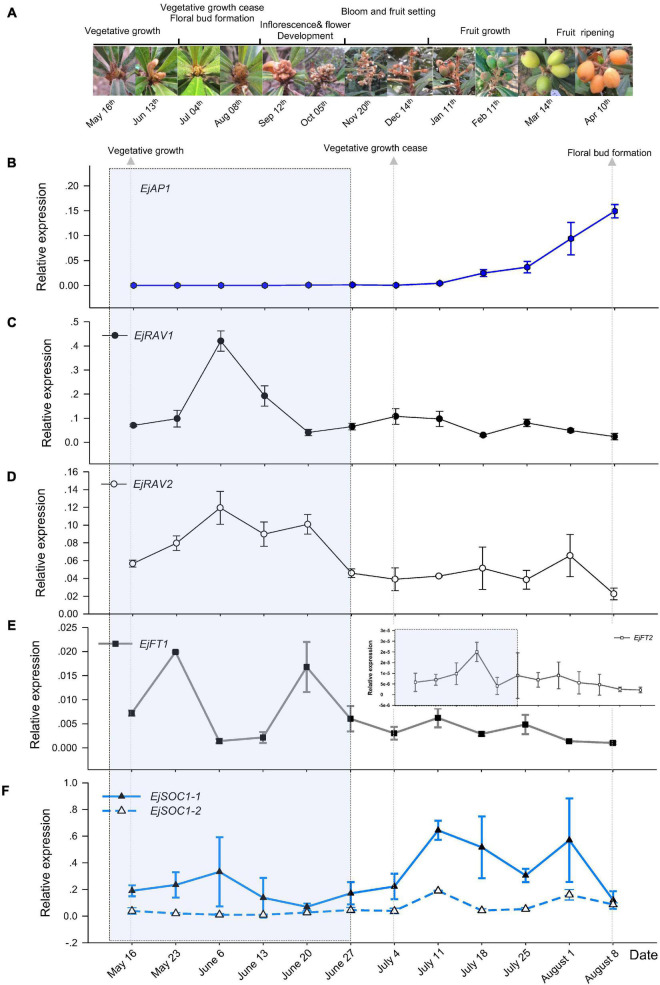

To understand the potential roles of EjRAV1 and EjRAV2, we first analyzed their expression patterns in fruit producing trees of Zaozhong-6 during inflorescence development. We started observations in May because fruits ripened in April and the SAM was still at vegetative growth stage. At this moment, the expression of EjAP1, a marker gene for floral initiation, was almost undetectable (Figures 2A,B). The SAM of trees stopped growing in July as the vegetative growth ceased, and the floral initiation and inflorescence development started. Ultimately, the SAM was transformed into inflorescence from shoot as the transcription levels of EjAP1 started to elevate dramatically from 18th July (Figures 2A,B).

FIGURE 2.

Floral initiation and expressions of flowering regulating gene homologs in “Zaozhong-6” loquat. (A) Developmental changes in shoot apical meristem (SAM) of “Zaozhong-6” loquat from May 2018 to April 2019. (B–F) Expression patterns of EjAP1 (B), EjRAV1 (C), EjRAV2 (D), EjFT1/2 (E), and EjSOC1-1/2 (F) during floral initiation and early inflorescence development. EjAP1 was detected in SAM, while other genes were detected in mature leaves. The error bars represent standard deviation for three biological replicates. The light gray colored window indicates vegetative phase.

Abundant EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 transcripts were detected at the vegetative growth stage. When the vegetative bud growth ceased, their expression levels were dramatically decreased and maintained at extremely low levels till the floral initiation started (Figures 2C,D). In contrast, the expressions levels of EjFT1 and EjFT2 increased as EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 were down-regulated (Figure 2E). Interestingly, the expression levels of both EjSOC1-1 and EjSOC1-2 increased after the up-regulation of EjFT1 and EjFT2, and a remarkable increase in the expression levels of EjAP1 was also detected (Figure 2F). The gene expression assays suggested that EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 may act as negative regulatory factors in the initiation of flowering in a fruit producing loquat tree.

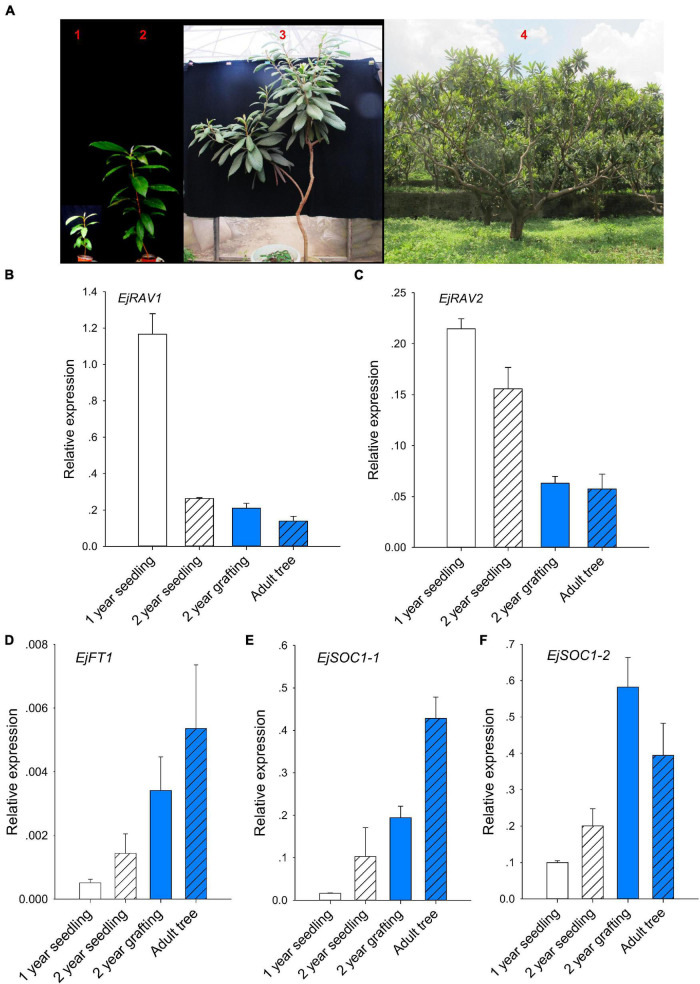

Abundant EjRAV1/2 and Rare EjFT and EjSOC1 Transcription Levels in Seedlings at Juvenile Phase

Prolonged juvenile phase is one of the most important ways that guarantee species survival. However, it reduces breeding efficiency, especially for perennial crops. To further confirm whether EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 play roles in the regulation of juvenile phase in loquat, we analyzed the expression patterns of EjRAV1/2 and other important flowering regulating genes in 1-year-old seedlings, 2-year-old seedlings, 2-year-old grafted trees, and fruit-bearing trees (Figure 3A). The 1-year-old seedlings and 2-year-old seedlings were still at the juvenile phase. The SAMs of both 2-year-old grafted trees (the scions were cut from fruit-bearing trees) and fruit-bearing trees were transformed into inflorescence in the autumn and set fruits later. The abundance of EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 transcripts were gradually reduced as the tree achieved the ability to form floral bud step by step (Figures 3B,C). By contrast, the expression levels of EjFT1, EjSOC1-1 and EjSOC1-2 increased continuously over this period (Figures 3D–F). Overall, the gene expression analyses suggested that EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 may act as important regulators of juvenility phase by repressing the flowering activator gene expressions.

FIGURE 3.

Association of abundant EjRAVs expressions and rare flowering activator gene expressions with the juvenile phase. (A) “Zaozhong-6” plants at different developmental stages in July, 2018. The red numbers, 1–4, in A showed plants of a 1-year-old seedling, a 2-year-old seedling, a 2-year-old grafted tree and an adult fruit-bearing tree used for gene expression assays, respectively. (B–F) Expression patterns of EjRAV1 (B), EjRAV2 (C), EjFT1 (D), EjSOC1-1 (E), and EjSOC1-2 (F) in mature leaves of these trees. The expression level of EjFT2 was almost undetectable in all the trees and data were not shown. The error bars in (B–F) represent standard deviation for three biological replicates.

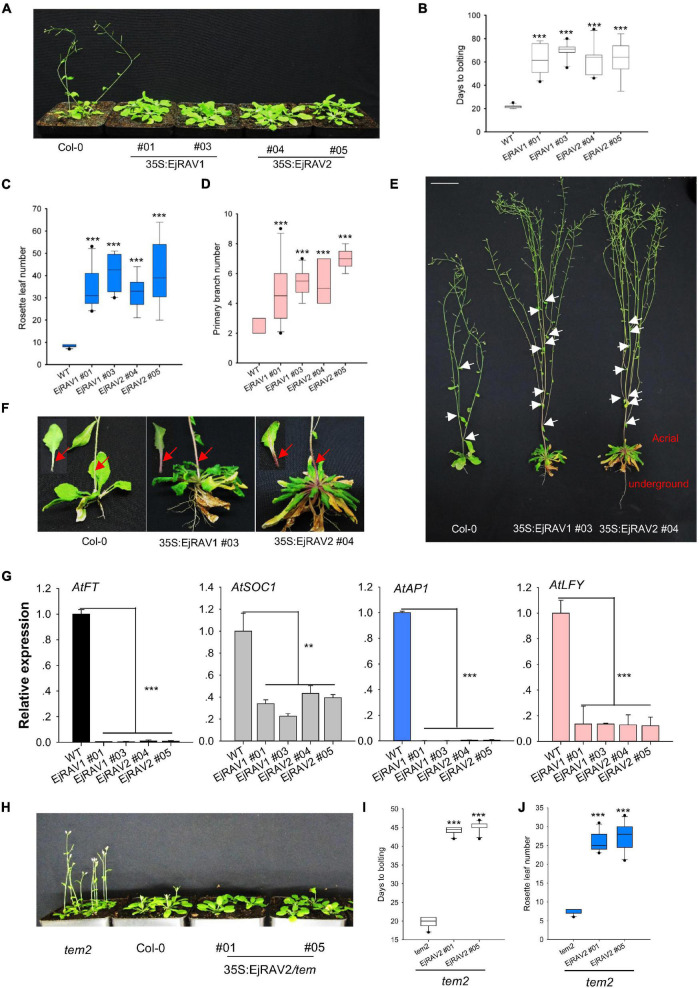

Overexpression of EjRAV1/2 Prolonged the Juvenile Phase in Arabidopsis

To confirm the above-mentioned speculation on the functions of EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 in the regulation of flowering time, we cloned each of them into a pGreen-35S plant overexpression vector for overexpression (OE) in Arabidopsis. Sequence alignment revealed that the encoded proteins of both genes are characterized by an AP2 domain and a B3 domain, as well as by a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and a B3 repression domain (Supplementary Figure 3). OE of both EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 in Columbia-0 (Col-0) background significantly delayed flowering (Figure 4A). The days to bolting after germination strikingly increased (3–4-fold) for all the OE transgenic plants than the wild type plants (Figure 4B), which indicated that EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 prolonged the juvenile phase in transgenic plants. At the same time, the number of rosette leaves of each OE transgenic line also greatly increased (Figure 4C). Unexpectedly, all the OE transgenic plants had a larger number of branches (about twofold) (Figures 4D,E) and stronger root systems than that of Col-0 (Figure 4E). It was also interesting that abundant anthocyanins were enriched in the basal parts of petiole and stem for all the OE transgenic plants (Figure 4F). Gene expression quantification confirmed that the expression levels of flowering activating genes, including AtFT, AtSOC1, AtAP1, and AtLFY, were significantly reduced in EjRAV1-OE and EjRAV2-OE transgenic plants compared to the wild type plants (Figure 4G). In addition, EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 were overexpressed in the tem2 mutant. Only stable EjRAV2-OE lines were obtained on the tem2 background. EjRAV2-OE/tem2 rescued the phenotype of tem2 to that of Col-0 wild type plant (Figure 4H). The days to bolting and numbers of rosette leaves of EjRAV2-OE/tem2 transgenic plants were strikingly larger (> 2 fold) than that of the tem2 mutant (Figures 4I,J). In summary, the OE experiments conducted here indicated that EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 repress the flowering and activate branching and anthocyanin accumulation in transgenic plants.

FIGURE 4.

Overexpression of EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 delay flowering and promote stem branching in Arabidopsis thaliana. (A) EjRAV1-OE and EjRAV2-OE delay flowering in Col-0 ecotype Arabidopsis. (B) The juvenile length (days to bolting) of all the overexpressed lines were strikingly prolonged. (C) The numbers of rosette leaves were greatly increased in the EjRAV1/2-OE lines. (D) EjRAV1-OE and EjRAV2-OE promoted lateral branching. (E) The phenotypes of Col-0 and EjRAV1/2-OE transgenic Arabidopsis plants. The ectopic expression of EjRAV1/2 was not only involved in the regulation of plant architecture (see leaf floral and axis branch numbers) but also associated with strong root system. Arrows indicate the growing point of the primary branch. (F) EjRAV1/2-OE activated anthocyanin accumulation in petiole and stem. Arrows represent abundant anthocyanin enriched in the basal parts of petiole and stem. (G) EjRAV1-OE and EjRAV2-OE repressed the expressions of flower inducer genes (FT, SOC1, AP1, and LFY) in Arabidopsis. (H) EjRAV2-OE rescues the phenotype of tem2 mutant (Col-0 background) to Col-0 at 4 weeks post germination. The (I) juvenile lengths and (J) rosette leaf numbers of the EjRAV2-OE transgenic plants (on tem2 background). The ** and *** indicate significant differences at P < 0.01 and < 0.001. The error bars in (B–D,I,J) represent standard deviation for 15 T3 plants. The error bars in (G) represent standard deviation for three replicates.

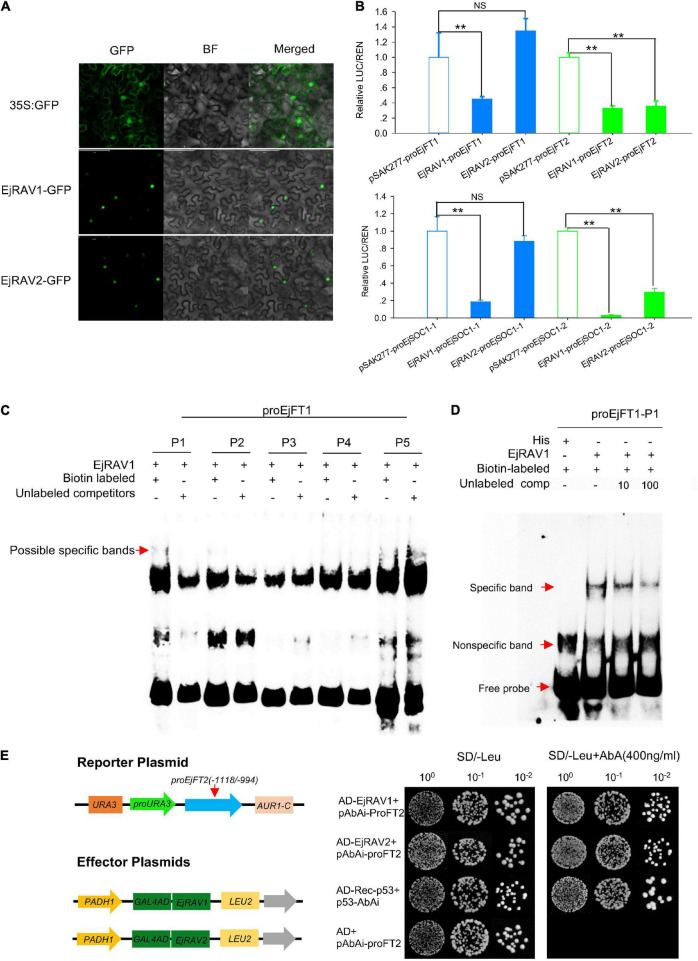

EjRAV1/2 Localized in Cell Nuclei and Bind to CAACA Motifs to Repress the Expressions of EjFT and EjSOC1

In agreement with the conserved NLS) appeared at the 5’ terminals of the encoded amino acid sequences (Supplementary Figure 3), EjRAV1-GFP and EjRAV2-GFP were localized in the cell nuclei of tobacco leaf cells (Figure 5A). To understand whether these two proteins play a role in EjFT or EjSOC1 expression modulation, dual-luciferase assays were performed. A total of 5, 5, 5, and 1 candidate RAV family protein binding sites were identified in the promoter regions of EjFT1, EjFT2, EjSOC1-1 and EjSOC1-2, respectively (Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2). The luciferase assay data showed that EjRAV1 greatly reduced the expressions of EjFT1/2 and EjSOC1-1/2, while EjRAV2 could significantly inhibit the expressions of EjFT2 and EjSOC1-2 (Figure 5B). Overall, these results suggested that the EjRAV1/2 proteins localized in the cell nucleus play regulatory roles in loquat.

FIGURE 5.

Protein localization, binding and regulation abilities of EjRAVs on FT and SOC1 homologs in loquat. (A) Subcellular localization of EjRAV1/2 proteins expressed in tobacco epidermal cells. (B) EjRAV1/2 regulation on EjFTs and EjSOC1s expressions in N. benthamiana leaves by using the dual-luciferase (LUC) system. Relative renilla (REN) luciferase activity was used as an internal control. Data represent means ± standard error from three replicates. **P < 0.01 and NS indicate significance and non-significance, respectively. (C,D) Binding ability of EjRAV1 to P1 of EjFT1 promoter in EMSA assays. P1, P2, P3, P4, and P5 are presumptive RAV protein binding sites on promoter of EjFT1 at (−1583 to −1579 bp), (−1059 to −1054 bp), (−1033 to −1029 bp), (−782 to −778 bp), and (−73 to −66 bp). Unlabeled probe could reduce binding ability of EjRAV1 to P1 in (D). (E) Binding ability of EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 to segment3 (−1118 to −994 bp) of EjFT2 promoter in Y1H assays.

To further check the abilities of EjRAV1 and/or EjRAV2 to regulate the expression levels of these genes, EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 proteins were prepared with Escherichia coli cells. Specific bands were induced by IPTG with protein size between 40 and 55 KDa and purified with Amylose Magnetic Beads. Protein-DNA binding was then assayed for EjRAV1-proEjFT1/2 and EjRAV2-proEjFT1/2 (Supplementary Figure 4), EjRAV1-proEjSOC1-1/2 and EjRAV2-proEjSOC1-1/2 (Supplementary Figure 5) combinations. The EMSA assays indicated that EjRAV1, but not EjRAV2, can bind directly to the CAACA motif at P1 (−1583 to −1579 bp) of proEjFT1, but not proEjFT2, in vitro (Figures 5C,D and Supplementary Figure 4). Yeast one-hybrid assay was performed to identify other binding sites on proEjFT2, which showed that EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 can directly bind in vivo to segment3 (−1118 to −994 bp) that contains two CAACA motifs (Figure 5E).

Discussion

Loquat, a Distinct Evergreen Fruit Tree, Blooms in Autumn

The decision to flower in plants during both the early life cycle and annual growth season is a complicated process that ultimately affects reproductive ability, breeding efficiency as well as other research progresses on the species (Somerville and Koornneef, 2002). In addition, flowering time determines the season for fruit, cut-flower and other horticultural products supplies (Wilkie et al., 2008). Loquat is one of the minor fruit trees whose fruits ripen from spring to early summer to meet the market demand of fresh fruits in spring, which benefits the growers greatly (Badenes et al., 2009). Commonly, SAM of perennial plants such as poplar (Tylewicz et al., 2018) and deciduous fruit trees (Kurokura et al., 2013) would cease growth and enter dormancy in fall to enable survival in the cold-drought stressful winter. The time of dormancy release is closely related to the flowering time of deciduous fruit trees including apple, pear, peach, and apricot (Falavigna et al., 2019). Here, we found that loquat initiated floral bud formation (Figure 2A) in a similar season compared with that of apple and pear in summer (Wilkie et al., 2008); however, the loquat SAM developed into an indeterminate panicle and bloomed immediately after floral initiation (Figure 2A) without the growth cease of reproductive buds or entering dormancy in fall. These results were in accordance with previous observations on the morphological transition of SAM, which also revealed immediate floral initiation in loquat (Liu et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2019). Collectively, the results from the present and previous studies revealed that the constant development of inflorescence and flower bud without entering dormancy leads to the unique flowering habit (in autumn) of cultivated loquat. Future in-depth studies are required to elucidate how cultivated loquat has evolved this distinct flowering ability.

RAV Homologs Maintain Juvenility and Repress Floral Induction in Loquat

The peculiar flowering habit of loquat ensures the availability of its fresh fruits in spring, a season short of fresh fruits in the market. Lots of endeavors aiming to identify pathways modulating flower induction in loquat have been carried out in the last decade (Esumi et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2007; Fernández et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2016; Reig et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2019, 2020a,b; Chen W. et al., 2020; Xia et al., 2020). FT and SOC1 are floral integrators that link upstream photoperiod and other environmental or internal signals to promote flowering, while the downstream AP1 controls the identity of floral meristem during flower bud transition (Blümel et al., 2015; Bouché et al., 2016). In loquat, using orthologs of these genes as biomarkers, the developmental stages of SAM during the annual growth cycle were classified as vegetative growth, vegetative growth cease and floral bud initiation (Figure 2), in accordance with our former histological observations (Jiang et al., 2019). In reference to these stages, negative correlations were detected between the expressions of EjRAV1/2 and the flowering activators, FT, SOC1, and AP1. Notably, the elevation of expressions of flowering activators occurred after the down-regulation of EjRAV1/2 (Figures 2B–F). These results implied that EjRAV1/2 are repressors of flowering during the vegetative phase of an annual growth season.

The long juvenile phase would severely reduce breeding efficiency of a perennial crop. Therefore, identifying targets to promote flower initiation at early stage became utmost important (Watson et al., 2018). Although a few flowering regulating genes have been reported to shorten the juvenile period (Hsu et al., 2006; Kotoda et al., 2010; Li et al., 2019), few studies were focused on the identification of candidate genes associated with the promotion or release of juvenility (Missiaggia et al., 2005). In the current study, remarkable negative correlations were discovered between the expressions of EjRAV1/2 and three flowering activator genes in loquat trees at different growth stages. The abundant accumulation of EjRAV1/2 was related with the low expressions of EjFT and EjSOC1s at seedling stage, while high expression levels of EjFT and EjSOC1s and low levels of EjRAV1/2 were detected in fruit bearing trees. Similarly in olive and antirrhinum, high DeTEM or AmTEM gene expressions were detected during the juvenile phase (Sgamma et al., 2015). To further validate the functions of EjRAV1/2, we generated overexpressed EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 transgenic plants of Arabidopsis with two different backgrounds (Col-0 ecotype and tem2), and the flowering time of all the transgenic plants were delayed while the juvenile period prolonged strikingly with a sharp decline of expression levels of flowering activator genes (Figure 4G). Our results were consistent with previous studies on the overexpression of AtTEM1/AtTEM2 (Castillejo and Pelaz, 2008) and DeTEM/AmTEM (Sgamma et al., 2015). Here, the gene expression analyses and overexpression experiments revealed that EjRAV1/2 are vital regulators of prolonged juvenility and repress floral induction in loquat.

EjRAVs Bind to the CAACA Motif of Flowering Signal Integrators to Delay Flower Bud Induction

Binding to the CAACA or CACCTG motif is essential for RAV genes to link photoperiod and gibberellin pathways to modulate flowering in Arabidopsis (Kagaya et al., 1999; Castillejo and Pelaz, 2008; Osnato et al., 2012). The expression of FT, modulated by the balance between CO and TEM, is an integrated signal that triggers flowering (Castillejo and Pelaz, 2008). Here, we identified the binding and transcriptional regulation capacities of EjRAV1/2 on FT and SOC1 homologs. Our results confirmed that cell nuclei localized EjRAV1/2 bind to the CAACA motif upstream of EjFT1 and EjFT2 promoters to repress their expressions. Although SOC1 is also a flowering pathway integrator and EjRAV1/2 sharply reduced the expression of EjSOC1, no binding site was detected on EjSOC1’s promoter region by EMSA (Supplementary Figure 5). This might be due to that EjRAV1/2 influence EjSOC1’s expression through another way instead of directly binding to the promoter region of EjSOC1, or due to other reasons, which requires future investigations. While AtRAVs and EjRAVs bind to the CAACA motifs upstream of FT promoter regions (Castillejo and Pelaz, 2008), OsRAVL1, a RAV homolog from rice, binds to the E-Box (CACCTG) in the promoters of Brassinosteroid (BR) signaling and the biosynthetic genes (Je et al., 2010).

EjRAVs Promote Branching and Anthocyanin Accumulation

Plant architecture is one of the most important factors modulating grain/fruit production (Wang L. et al., 2020). Loquat is particularly robust in apical dominance and deficient of lateral branches, which remarkably limit the potential of fruit yield improvement (Badenes et al., 2009). Interestingly, the overexpression of EjRAV1/2 remarkably promoted lateral branches in Arabidopsis, similar to the role of their close homologs CsRAV1 (Moreno-Cortés et al., 2012) and PtRAV1 (Moreno-Cortés et al., 2017) in the induction of sylleptic branches. Transgenic plants overexpressing RAV1 lost shoot apical dominance in Arabidopsis. In rice, OsRAVL1 (Je et al., 2010) and OsRAV6 (Xianwei et al., 2015) maintain BR homeostasis to modulate leaf angle and seed size. Meanwhile, the TEM genes in Arabidopsis can link photoperiod and gibberellin signals to control flowering (Osnato et al., 2012) and jasmonic acid signaling in salt tolerance (Osnato et al., 2020). These studies suggest that RAVs may act to reprogram hormone homeostasis and signal transduction to further promote lateral branches. In Arabidopsis, changes on strigolactone signaling affected shoot branching and anthocyanin biosynthesis via binding to BRANCHED1 (BRC1) and PRODUCTION OF ANTHOCYANIN PIGMENT 1 (PAP1) promoters (Wang L. et al., 2020). Consistent with this speculation, research in strawberry revealed that FaRAV1 can positively regulate anthocyanin accumulation in the fruit by activating FaMYB10, a homolog of PAP1 (Zhang et al., 2020). Meanwhile, the vital branching regulators including BRC1 (Niwa et al., 2013) and it homologs TEOSINTE BRANCHED 1, CYCLOIDEA, PCF/TCP transcription factors (Lucero et al., 2017) were involved in flowering time regulation via interacting with FT or direct regulation of SOC1 transcription. Therefore, the RAV gene family play vital roles in many developmental processes.

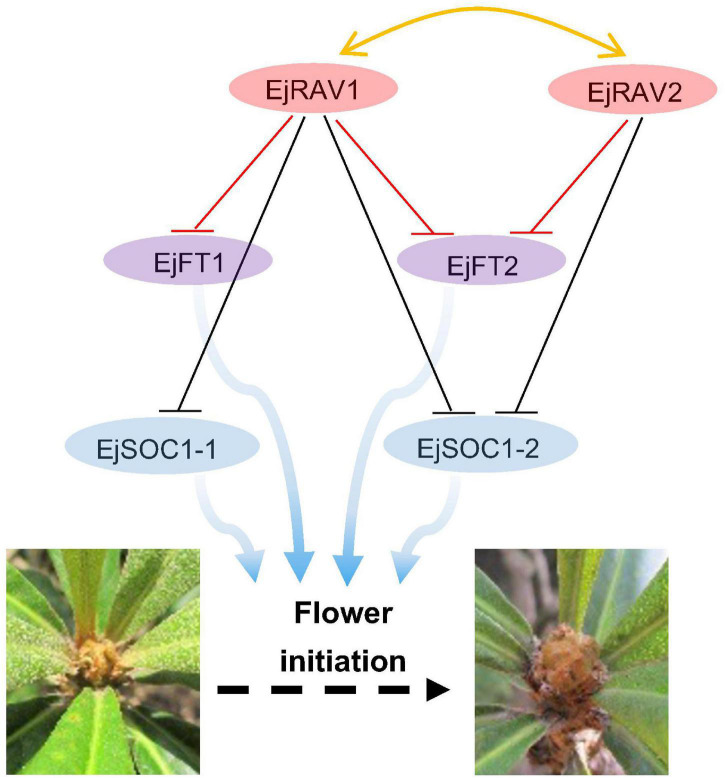

Here, we identified two multifunctional RAV homologs in loquat with major roles in maintaining juvenility and delaying flowering in an annual growth cycle. Based on these results, we presented a potential model of pathways of EjRAV1/2 to modulate floral bud formation during the tree life cycle and annual growth cycle based on molecular assays (Figure 6). In this putative model, EjRAV1/2 bind directly to the CAACA motifs upstream of EjFT1 and EjFT2 promoters and repress their expressions to keep loquat trees in the juvenile phase and delay flowering in an annual growth cycle. In addition, EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 are important regulators of shoot branching and anthocyanin biosynthesis. The substantial evidence revealed that EjRAV1/2 play vital roles in the initiation of flowering, and both could be potential targets for breeding programs to accelerate loquat breeding by shortening the juvenile phase and extend the fruit supply season.

FIGURE 6.

A proposed model for EjRAV1/2 to regulate flowering time. The central network shows that EjRAV1/2 repress FT and SOC1 homologs expressions to delay flowering in an annual production season of loquat. The arrows represent promotion of FT and SOC1 homologs on flower initiation. The T arrows represent transcriptional repression of EjRAV1/2 on FT and SOC1 expressions.

Conclusion

Two RELATED TO ABI3 AND VP1 (RAV) homologs were isolated in loquat. These two genes maintained high expressions during the juvenile or vegetative phase, which was negatively correlated with flowering promoting genes like EjFT1/EjFT2 and EjSOC1-1/EjSOC1-2. Overexpression of EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 delayed flowering and repressed FT, SOC1 and AP1 expressions in Arabidopsis. Both EjRAV1 and EjRAV2 proteins are localized to the cell nuclei and could bind to the CAACA motifs and repress the expressions of EjFTs and EjSOC1s. These findings contribute to our understanding of the molecular mechanism of loquat phase change and flowering time regulation and provide gene targets to shorten the fruit tree juvenility and accelerate breeding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

XY, WS, and YG designed the research and obtained the funding. MW and WS performed the transgenic transformation and Y1H assays. MW, WS, and YJ performed the luciferases reporter assays. LZ and WS prepared the proteins and performed the EMSA assays. MW, ZP, WS, CZ, YB, JH, JP, and YG performed the other experiments. WS, MW, and ZP analyzed the data. ZP, WS, XY, and MS prepared the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank the experimental instrument service supported by the Key Laboratory of Innovation and Utilization of Horticultural Crop Resources in South China (Ministry of Agriculture). We wish to acknowledge Profs. Wangjin Lu and Jianye Chen for providing pGreen-0800, pGADT7 and pAbAi vectors. We sincerely thank Prof. Shunquan Lin for the guidance and suggestions to this project.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2019YFD1000200), the Key Areas of Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (2018B020202011), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31901973), the Collaborative Innovation Project from the People’s Government of Fujian Province and Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (XTCXGC2021006), and Research Start-up Funding (to ZP) from South China Agricultural University.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2021.816086/full#supplementary-material

References

- Andrés F., Coupland G. (2012). The genetic basis of flowering responses to seasonal cues. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13 627–639. 10.1038/nrg3291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badenes M. L., Lin S., Yang X., Liu C., Huang X. (2009). “Loquat (Eriobotrya Lindl.),” in Plant Genetics and Genomics: Crops and Models, eds Folta K. M., Gardiner S. E. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 525–538. [Google Scholar]

- Blümel M., Dally N., Jung C. (2015). Flowering time regulation in crops—what did we learn from Arabidopsis? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 32 121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouché F., Lobet G., Tocquin P., Périlleux C. (2016). FLOR-ID: an interactive database of flowering-time gene networks in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 D1167–D1171. 10.1093/nar/gkv1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillejo C., Pelaz S. (2008). The balance between CONSTANS and TEMPRANILLO activities determines FT expression to trigger flowering. Curr. Biol. 18 1338–1343. 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Chen H., Zhang Y., Thomas H. R., Frank M. H., He Y., et al. (2020). TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13 1194–1202. 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Wang P., Wang D., Shi M., Xia Y., He Q., et al. (2020). EjFRI, FRIGIDA (FRI) ortholog from Eriobotrya japonica, delays flowering in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:1087. 10.3390/ijms21031087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel P. W. Y. H. (2015). The FLOWERING LOCUS T/TERMINAL FLOWER 1 gene family: functional evolution and molecular mechanisms. Mol. Plant 8 983–997. 10.1016/j.molp.2015.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esumi T., Tao R., Yonemori K. (2005). Isolation of LEAFY and TERMINAL FLOWER 1 homologues from six fruit tree species in the subfamily Maloideae of the Rosaceae. Sex. Plant Reproduct. 17 277–287. [Google Scholar]

- Falavigna V. D. S., Guitton B., Costes E., Andrés F. (2019). I want to (bud) break free: the potential role of DAM and SVP-Like genes in regulating dormancy cycle in temperate fruit trees. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1990. 10.3389/fpls.2018.01990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández M. D., Hueso J. J., Cuevas J. (2010). Water stress integral for successful modification of flowering dates in ‘Algerie’ loquat. Irrigat. Sci. 28 127–134. 10.1007/s00271-009-0165-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goeckeritz C., Hollender C. A. (2021). There is more to flowering than those DAM genes: the biology behind bloom in rosaceous fruit trees. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 59:101995. 10.1016/j.pbi.2020.101995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Soto D., Ramos-Sánchez J. M., Alique D., Conde D., Triozzi P. M., Perales M., et al. (2021). Overexpression of a SOC1-related gene promotes bud break in ecodormant poplars. Front. Plant Sci. 12:670497. 10.3389/fpls.2021.670497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halász J., Hegedűs A., Karsai I., Tósaki Á., Szalay L. (2021). Correspondence between SOC1 genotypes and time of endodormancy break in peach (Prunus persica L. Batsch) cultivars. Agronomy 11:1298. 10.3390/agronomy11071298 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hellens R. P., Allan A. C., Friel E. N., Bolitho K., Grafton K., Templeton M. D., et al. (2005). Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods 1:13. 10.1186/1746-4811-1-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques R., Lin S., Chua N., Zhang X., Niu Q. (2006). Agrobacterium -mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana using the floral dip method. Nat. Protoc. 1 641–646. 10.1038/nprot.2006.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C. Y., Liu Y., Luthe D. S., Yuceer C. (2006). Poplar FT2 shortens the juvenile phase and promotes seasonal flowering. Plant Cell 18 1846–1861. 10.1105/tpc.106.041038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Je B. I., Piao H. L., Park S. J., Park S. H., Kim C. M., Xuan Y. H., et al. (2010). RAV-Like1 maintains brassinosteroid homeostasis via the coordinated activation of BRI1 and biosynthetic genes in rice. Plant Cell 22 1777–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia X. L., Chen Y. K., Xu X. Z., Shen F., Zheng Q. B., Du Z., et al. (2017). miR156 switches on vegetative phase change under the regulation of redox signals in apple seedlings. Sci. Rep. 7 14213–14223. 10.1038/s41598-017-14671-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Peng J., Wang M., Su W., Gan X., Jing Y., et al. (2020a). The role of EjSPL3, EjSPL4, EjSPL5, and EjSPL9 in regulating flowering in loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:248. 10.3390/ijms21010248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Peng J., Zhu Y., Su W., Zhang L., Jing Y., et al. (2019). The role of EjSOC1s in flower initiation in Eriobotrya japonica. Front. Plant Sci. 10:253. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Zhu Y., Zhang L., Su W., Peng J., Yang X., et al. (2020b). EjTFL1 genes promote growth but inhibit flower bud differentiation in loquat. Front. Plant Sci. 11:576. 10.3389/fpls.2020.00576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagaya Y., Ohmiya K., Hattori T. (1999). RAV1, a novel DNA-binding protein, binds to bipartite recognition sequence through two distinct DNA-binding domains uniquely found in higher plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 27 470–478. 10.1093/nar/27.2.470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotoda N., Hayashi H., Suzuki M., Igarashi M., Hatsuyama Y., Kidou S., et al. (2010). Molecular characterization of FLOWERING LOCUS T-Like genes of apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.). Plant Cell Physiol. 51 561–575. 10.1093/pcp/pcq021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokura T., Mimida N., Battey N. H., Hytonen T. (2013). The regulation of seasonal flowering in the Rosaceae. J. Exp. Bot. 64 4131–4141. 10.1093/jxb/ert233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Yamagishi N., Kasajima I., Yoshikawa N. (2019). Virus-induced gene silencing and virus-induced flowering in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) using apple latent spherical virus vectors. Hortic. Res. 6:18. 10.1038/s41438-018-0106-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Song H., Liu Z., Hu G., Lin S. (2013). Molecular characterization of loquat EjAP1 gene in relation to flowering. Plant Growth Regul. 70 287–296. 10.1007/s10725-013-9800-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Zhao Q., Meng N., Song H., Li C., Hu G., et al. (2017). Over-expression of EjLFY-1 leads to an early flowering habit in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) and its asexual progeny. Front. Plant Sci. 8:496. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero L. E., Manavella P. A., Gras D. E., Ariel F. D., Gonzalez D. H. (2017). Class I and class II TCP transcription factors modulate SOC1-dependent flowering at multiple levels. Mol. Plant 10 1571–1574. 10.1016/j.molp.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matias-Hernandez L., Aguilar-Jaramillo A. E., Marin-Gonzalez E., Suarez-Lopez P., Pelaz S. (2014). RAV genes: regulation of floral induction and beyond. Ann. Bot. 114 1459–1470. 10.1093/aob/mcu069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry R. C., Klocko A. L., Pang M., Strauss S. H., Ayre B. G. (2017). Virus-Induced flowering: an application of reproductive biology to benefit plant research and breeding. Plant Physiol. 173 47–55. 10.1104/pp.16.01336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiaggia A. A., Piacezzi A. L., Grattapaglia D. (2005). Genetic mapping of Eef1, a major effect QTL for early flowering in Eucalyptus grandis. Tree Genet. Genomes 1 79–84. 10.1007/s11295-005-0011-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Cortés A., Hernández-Verdeja T., Sánchez-Jiménez P., González-Melendi P., Aragoncillo C., Allona I. (2012). CsRAV1 induces sylleptic branching in hybrid poplar. New Phytol. 194 83–90. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.04023.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Cortés A., Ramos-Sánchez J. M., Hernández-Verdeja T., González-Melendi P., Alves A., Simoes R., et al. (2017). Impact of RAV1-engineering on poplar biomass production: a short-rotation coppice field trial. Biotechnol. Biofuels 10:110. 10.1186/s13068-017-0795-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa M., Daimon Y., Kurotani K., Higo A., Pruneda-Paz J. L., Breton G., et al. (2013). BRANCHED1 interacts with FLOWERING LOCUS T to repress the floral transition of the axillary meristems in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25 1228–1242. 10.1105/tpc.112.109090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osnato M., Castillejo C., Matías-Hernández L., Pelaz S. (2012). TEMPRANILLO genes link photoperiod and gibberellin pathways to control flowering in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 3:808. 10.1038/ncomms1810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osnato M., Cereijo U., Sala J., Matias-Hernandez L., Aguilar-Jaramillo A. E., Rodríguez-Goberna M. R., et al. (2020). The floral repressors TEMPRANILLO1 and 2 modulate salt tolerance by regulating hormonal components and photo-protection in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 105 7–12. 10.1111/tpj.15048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter D., Eriksson T., Evans R. C., Oh S., Smedmark J. E. E., Morgan D. R., et al. (2007). Phylogeny and classification of Rosaceae. Plant Syst. Evol. 266 5–43. 10.1007/s00606-007-0539-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reig C., Gil-Muñoz F., Vera-Sirera F., García-Lorca A., Martínez-Fuentes A., Mesejo C., et al. (2017). Bud sprouting and floral induction and expression of FT in loquat [Eriobotrya japonica (Thunb.) Lindl.]. Planta 246 915–925. 10.1007/s00425-017-2740-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgamma T., Jackson A., Muleo R., Thomas B., Massiah A. (2015). TEMPRANILLO is a regulator of juvenility in plants. Sci. Rep. 4:3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville C., Koornneef M. (2002). A fortunate choice: the history of Arabidopsis as a model plant. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3 883–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. H., Ito S., Imaizumi T. (2013). Flowering time regulation: photoperiod- and temperature-sensing in leaves. Trends Plant Sci. 18 575–583. 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W., Jing Y., Lin S., Yue Z., Yang X., Xu J., et al. (2021). Polyploidy underlies co-option and diversification of biosynthetic triterpene pathways in the apple tribe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118:e2101767118. 10.1073/pnas.2101767118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W., Yuan Y., Zhang L., Jiang Y., Gan X., Bai Y., et al. (2019). Selection of the optimal reference genes for expression analyses in different materials of Eriobotrya japonica. Plant Methods 15:7. 10.1186/s13007-019-0391-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S., et al. (2011). MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28 2731–2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tränkner C., Lehmann S., Hoenicka H., Hanke M. V., Fladung M., Lenhardt D., et al. (2010). Over-expression of an FT-homologous gene of apple induces early flowering in annual and perennial plants. Planta 232 1309–1324. 10.1007/s00425-010-1254-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tylewicz S., Petterle A., Marttila S., Miskolczi P., Azeez A., Singh R. K., et al. (2018). Photoperiodic control of seasonal growth is mediated by ABA acting on cell-cell communication. Science 360 212–215. 10.1126/science.aan8576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voogd C., Brian L. A., Wang T., Allan A. C., Varkonyi-Gasic E. (2017). Three FT and multiple CEN and BFT genes regulate maturity, flowering, and vegetative phenology in kiwifruit. J. Exp. Bot. 68 1539–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. (2014). Regulation of flowering time by the miR156-mediated age pathway. J. Exp. Bot. 65 4723–4730. 10.1093/jxb/eru246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Gao Z., Li H., Jiu S., Qu Y., Wang L., et al. (2020). Dormancy-associated MADS-Box (DAM) genes influence chilling requirement of sweet cherries and co-regulate flower development with SOC1 gene. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:921. 10.3390/ijms21030921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Wang B., Yu H., Guo H., Lin T., Kou L., et al. (2020). Transcriptional regulation of strigolactone signalling in Arabidopsis. Nature 583 277–281. 10.1038/s41586-020-2382-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson A., Ghosh S., Williams M. J., Cuddy W. S., Simmonds J., Rey M. D., et al. (2018). Speed breeding is a powerful tool to accelerate crop research and breeding. Nat. Plants 4 23–29. 10.1038/s41477-017-0083-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie J. D., Sedgley M., Olesen T. (2008). Regulation of floral initiation in horticultural trees. J. Exp. Bot. 59 3215–3228. 10.1093/jxb/ern188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y., Xue B., Shi M., Zhan F., Wu D., Jing D., et al. (2020). Comparative transcriptome analysis of flower bud transition and functional characterization of EjAGL17 involved in regulating floral initiation in loquat. PLoS One 15:e239382. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y., Huang C., Hu Y., Wen J., Li S., Yi T., et al. (2016). Evolution of Rosaceae fruit types based on nuclear phylogeny in the context of geological times and genome duplication. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34 262–281. 10.1093/molbev/msw242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xianwei S., Zhang X., Sun J., Cao X. (2015). Epigenetic mutation of RAV6 affects leaf angle and seed size in rice. Plant Physiol. 169 2118–2128. 10.1104/pp.15.00836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M., Hu T., Zhao J., Park M., Earley K. W., Wu G., et al. (2016). Developmental functions of miR156-regulated SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE (SPL) genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 12:e1006263. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Zhang L., Wu G. (2018). Epigenetic regulation of juvenile-to-adult transition in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1048. 10.3389/fpls.2018.01048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi N., Li C., Yoshikawa N. (2016). Promotion of flowering by apple latent spherical virus vector and virus elimination at high temperature allow accelerated breeding of apple and pear. Front. Plant Sci. 7:171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S., Hu Y., Zhou B. (2007). Studies on floral induction phase and carbohydrate contents in apical bud during floral differentiation in loquat. Acta Hortic. 750 395–400. [Google Scholar]

- Yarur A., Soto E., León G., Almeida A. M. (2016). The sweet cherry (Prunus avium) FLOWERING LOCUS T gene is expressed during floral bud determination and can promote flowering in a winter-annual Arabidopsis accession. Plant Reproduct. 29 311–322. 10.1007/s00497-016-0296-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Zhang L., Wang W., Tian P., Wang W., Wang K., et al. (2020). TCP5 controls leaf margin development by regulating the KNOX and BEL-like transcription factors in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 72 1809–1821. 10.1093/jxb/eraa569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Jiang Y., Zhu Y., Su W., Long T., Huang T., et al. (2019). Functional characterization of GI and CO homologs from Eriobotrya deflexa Nakai forma koshunensis. Plant Cell Rep. 38 533–543. 10.1007/s00299-019-02384-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Yu H., Lin S., Gao Y. (2016). Molecular characterization of FT and FD homologs from Eriobotrya deflexa Nakai forma koshunensis. Front. Plant Sci. 7:8. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Shi Y., Ma Y., Yang X., Yin X., Zhang Y., et al. (2020). The strawberry transcription factor FaRAV1 positively regulates anthocyanin accumulation by activation of FaMYB10 and anthocyanin pathway genes. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18 2267–2279. 10.1111/pbi.13382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S., Huang J., Xu X. (1991). Research on early maturing and related properties in loquat. Southeast Hortic. 5 1–5. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.