Abstract

Background

HIV‐infected people and AIDS patients often seek complementary therapies including herbal medicines due to reasons such as unsatisfactory effects, high cost, non‐availability, or adverse effects of conventional medicines.

Objectives

To assess beneficial effects and risks of herbal medicines in patients with HIV infection and AIDS.

Search methods

Electronic searches included the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS, Science Citation Index, the Chinese Biomedical Database, TCMLARS; plus CISCOM, AMED, and NAPRALERT; combined with manual searches. The search ended in December 2004.

Selection criteria

Randomized clinical trials on herbal medicines compared with no intervention, placebo, or antiretroviral drugs in patients with HIV infection, HIV‐related disease, or AIDS. The outcomes included mortality, HIV disease progression, new AIDS‐defining event, CD4 cell counts, viral load, psychological status, quality of life, and adverse effects.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors extracted data independently and assessed the methodological quality of trials according to randomization, allocation concealment, double blinding, and drop‐out.

Main results

Nine randomized placebo‐controlled trials involving 499 individuals with HIV infection and AIDS met the inclusion criteria. Methodological quality of trials was assessed as adequate in five full publications and unclear in other trials. Eight different herbal medicines were tested.

A compound of Chinese herbs (IGM‐1) showed significantly better effect than placebo in improvement of health‐related quality of life in 30 symptomatic HIV‐infected patients (WMD 0.66, 95% CI 0.05 to 1.27). IGM‐1 appeared not to affect overall health perception, symptom severity, CD4 count, anxiety or depression (Burack 1996a). An herbal formulation of 35 Chinese herbs did not affect CD4 cell counts, viral load, AIDS events, symptoms, psychosocial measure, or quality of life (Weber 1999). There was no statistical difference between SPV30 and placebo in new AIDS‐defining events, CD4 cell counts, or viral load (Durant 1998) although an earlier pilot trial showed positive effect of SPV30 on CD4 cell count (Durant 1997). Combined treatment of Chinese herbal compound SH and antiretroviral agents showed increased antiviral benefit compared with antiretrovirals alone (Sangkitporn 2004). SP‐303 appeared to reduce stool weight (p = 0.008) and abnormal stool frequency (p = 0.04) in 51 patients with AIDS and diarrhoea (Holodniy 1999). Qiankunning appeared not to affect HIV‐1 RNA levels (Shi 2003), Curcumin ineffective in reducing viral load or improving CD4 cell counts (Hellinger 1996), and Capsaicin ineffective in relieving pain associated with HIV‐related peripheral neuropathy (Paice 2000).

The occurrence of adverse effects was higher in the 35 Chinese herbs preparation (19/24) than in placebo (11/29) (79% versus 38%, p = 0.003) (Weber 1999). Qiankunning was associated with stomach discomfort and diarrhoea (Shi 2003).

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence to support the use of herbal medicines in HIV‐infected individuals and AIDS patients. Potential beneficial effects need to be confirmed in large, rigorous trials.

Plain language summary

There is no compelling evidence to support the use of the herbal medicines identified in this review for treatment of HIV infection and AIDS.

People with HIV infection or AIDS frequently seek alternative or 'complementary' therapies for their illness. Although many trials of these therapies exist, very few meet the scientific standards necessary to support the claims of beneficial effects in the therapies studied. This review identified nine randomized clinical trials, which tested eight different herbal medicines, compared with placebo, in HIV‐infected individuals or AIDS patients with diarrhoea. The results showed that a preparation called SPV30 may be helpful in delaying the progression of HIV disease in HIV‐infected people who do not have any symptoms of this infection. A Chinese herbal medicine, IGM‐1, seems to improve the quality of life in HIV‐infected people who do have symptoms. Another herbal compound ,SH, showed an increase of antiviral benefit when combined with antiretroviral agents. A South American herb preparation, SP‐303, may reduce the frequency of abnormal stools in AIDS patients with diarrhoea. Other herbs tested were no better than placebo; however, the beneficial effects need to be considered with caution because the number of patients in these trials was small and the size of the effects quite moderate. In one trial the use of medicinal herbs was related to adverse effects such as gastrointestinal discomfort. Conclusion: No compelling evidence exists to support the use of the herbal medicines identified in this review for treatment of HIV infection and AIDS. To ensure that evidence is reliable, there need to be larger and more rigorously‐designed trials.

Background

The introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) into clinical practice in 1996 has dramatically changed the development of HIV‐related diseases in industrialized countries (Bonfanti 1999; Shafer 1999; Tirelli 2001; Vella 2000). Although they cannot cure HIV infection and AIDS, the antiretrovirals have an impact on reducing morbidity and mortality, prolonging lives, and improving the quality of life of many people living with HIV/AIDS (WHO 2002). However, many people with HIV/AIDS in developing countries cannot afford the high costs of HAART. Moreover, HAART has a limited response in some patients, includes a complicated dosage regimen, and is associated with some drug toxicities. There is also a problem with cross‐resistance among antiretroviral drugs of the same class (Bonfanti 1999; Vella 2000). The therapeutic options of treating HIV/AIDS are currently still limited, and alternative approaches are needed. Because of the chronicity and impact of HIV‐related diseases on quality of life and the possibility of severe complications and death, patients with HIV/AIDS are likely to seek alternative and complementary therapies (Ozsoy 1999), particularly in areas of the world where HAART is not available or economically feasible.

Complementary medicine is defined as diagnostic, treatment, or preventive measures that complement mainstream medicine by contributing to a common whole, by satisfying a demand not met by orthodox medicine, or by diversifying the conceptual frameworks of medicine (Ernst 1995). Complementary therapies are increasingly being used (Eisenberg 1998; Vickers 2000). The number of randomized trials of complementary treatments has doubled every five years (Vickers 2000), and The Cochrane Library now includes over 100 systematic reviews of complementary medicine interventions. Many people turn to these therapies when conventional medicine fails them, or when they believe strongly in the effectiveness of complementary medicine. The majority of people living with HIV/AIDS are using complementary medicine (Ozsoy 1999). The conception that complementary therapies do more good than harm needs to be reviewed systematically.

Herbal medicines, among the most popular of complementary therapeutic modalities, are defined in this review as products derived from plants or parts of plants used for the treatment of HIV/AIDS. Some HIV‐infected people use herbs for potential cure or symptom treatment. For example, in China and South Africa these treatments are used as primary treatments. Some clinical studies have shown that herbal medicines might have the potential to alleviate symptoms, reduce viral load, and increase CD4+ cells for HIV‐infected individuals and AIDS patients (Burack 1996a; Durant 1998; Kang 1999a; Liu 2000; Lu 1993; Zheng 1999). On the other hand, there is an increasing number of reports in the medical literature about liver toxicity and other adverse events from some herbal products (Ishizaki 1996; Melchart 1999), as well as possible herb‐drug interactions (Izzo 2001). Accordingly, further research and systematic evaluation are necessary.

Objectives

The objective of this review is to assess the beneficial and harmful effects of herbal medicines on patients with HIV infection or AIDS compared with no intervention, placebo, or antiretroviral drug. The outcomes of interest would be mortality and morbidity, adverse events, immunological and virological responses, quality of life, and health economics.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized clinical trials and quasi‐randomized trials irrespective of publication status or language. Observational studies and case series were excluded.

Types of participants

Male or female patients of any age or ethnic origin who have HIV infection, HIV‐related disease, or AIDS. Since co‐infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) or hepatitis B virus (HBV) may affect AIDS disease progression and survival time (Anonymous 2002; Dorrucci 1995; Martin 2001; Monga 2001; Sud 2001), patients co‐infected with HCV or HBV are included and analyzed in subgroup analysis.

Types of interventions

Herbal medicines defined as preparations derived from plants or parts of plants used for treatment of disease could be extracts from a single herb, or a compound of herbs. They were compared with no intervention, placebo, and antiretrovirals (monotherapy and combination therapies including HAART). Trials of herbal medicine plus antiretroviral drug(s) versus antiretroviral drug(s) alone were also included.

Types of outcome measures

Primary Outcomes: ‐ mortality (all‐cause and AIDS related); ‐ HIV disease progression; ‐ new AIDS‐defining event; ‐ number and type of adverse events. Two types of adverse events were collected: serious adverse events and adverse events not considered serious. The serious adverse events were any untoward medical occurrence that resulted in death, was life‐threatening, required hospitalization or prolongation of hospitalization, resulted in persistent or significant disability, was a congenital anomaly/birth defect or was an event that may jeopardize the patient or require intervention to prevent one of the former serious adverse events (ICH‐GCP 1997). All other adverse events were considered non‐serious.

Secondary Outcomes: ‐ immunological indicators considered in this review include but are not limited to: CD4 count and white blood cell count (cells/mm3); ‐ virological indicator: viral load; ‐ psychological status and health‐related quality of life (HRQOL), measured by but not limited to: Montgomery‐Asberg Scale for Depression, General Health Questionnaire, Quality of Life Questionnaire, SF‐20, MOS‐HIV, SF‐36, SF‐12, SF‐56, SF‐38, SF‐21, HCSUS, Quality of Well‐Being Scale, Q‐TWIST, Quality of Life Index, EuroQol, EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire, Sickness Impact Profile, and Health Utility Assessment.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic Searches The following databases were searched: ‐Cochrane HIV/AIDS Group Trials Register (August 2004), CENTRAL database (The Cochrane Library Issue 4, 2004), the Cochrane Complementary Medicine Field (August 2004); ‐ MEDLINE (1966 ‐ 2004), EMBASE (1998 ‐ 2004), LILACS (www.bireme.br, 2004), Science Citation Index (SCI, www.isinet.com/cgi‐bin/), and the Chinese Biomedical CD‐ROM Database (1979 ‐ 12/2004), Traditional Chinese Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System (TCMLARS) (1984 ‐ 2004); ‐ CISCOM (The Centralised Information Service for Complementary Medicine: http://www.rccm.org.uk/cisc.htm), AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database: http://www.bl.uk/services/information/amed.html). The search terms (both MeSH term and free‐text terms) included HIV, acquired‐immunodeficiency‐syndrome (AIDS), medicine‐traditional, herbal‐medicine, medicine‐Chinese, medicine‐Chinese‐traditional, plants‐medicinal, drugs‐herbal, plants extracts, herbs, herbs‐medicinal, medicinal‐herbs, herbal teas, drugs‐Chinese‐herbal, herbal preparations, drugs‐non‐prescription, alternative‐medicine, complementary‐medicine, traditional‐medicine, phytotherapy, and medicine‐traditional‐oriental.

Handsearches Chinese Journal of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Journal of Dermatovenereology, Journal for China AIDS/STD Prevention and Control, Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine, Research of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine were handsearched from the first publication date onwards to December 2004. Conference proceedings in Chinese were also handsearched.

Additional Search Manufacturers of herbal preparations and experts in relevant fields were contacted for potential trials. The bibliographies of identified trials and review articles were checked in order to find randomised trials not identified by the electronic searches or handsearches.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of Trials for Inclusion Two authors (JL and MY) independently selected trials to be included in the review according to the pre‐specified selection criteria. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion.

Assessment of Methodological Quality The methodological quality was assessed by the following four quality components: adequacy of generation of the allocation sequence, allocation concealment, double blinding, and follow‐up (Jadad 1996; Kjaergard 2001; Moher 1998; Schulz 1995).

The quality components included: ‐ generation of the allocation sequence: adequate (computer‐generated random numbers or similar) or inadequate (other methods or not described); ‐ allocation concealment: adequate (central independent unit, serially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes, or similar) or inadequate (not described or open table of random numbers or similar); ‐ double blinding: adequate (identical placebo or similar) or inadequate (not performed or tablets versus injections or similar); ‐ follow‐up: adequate (number and reasons for dropouts and withdrawals described) or inadequate (number or reasons for dropouts and withdrawals not described).

In order to assess adverse effects, guidelines developed by the Cochrane Non‐Randomized Studies Methods Group were used to evaluate the quality of the observational studies, and the data were treated as descriptive analysis.

Further, we noted whether or not the randomized clinical trials reported using intention‐to‐treat analysis (Wright 2003).

Data Extraction Two authors (JL and MY) extracted data independently using a self‐developed data extraction form. Papers not in Chinese, English, German, Japanese, or French were translated with the help of the Cochrane HIV/AIDS Group. The following characteristics and data were extracted from each included trial: primary author, methodological quality, mean age, male/female ratio, disease stage, CD4 count and ethnicity of patients, duration of infection (if known), co‐infection with HCV or HBV (if known), number of randomized patients and number lost during follow‐up, patient inclusion and exclusion criteria, prior antiretroviral therapy and its duration, dosage, regimen, and duration of intervention, quality of the herb extract, outcome measures, and number and type of adverse events.

Data on the number of patients with each outcome by allocated treatment group irrespective of compliance or follow‐up were sought to allow an intention‐to‐treat analysis. If the above data were not available in the trial reports, further information was sought by correspondence with the principal investigator.

Data Synthesis Dichotomous data were presented as relative risk (RR) and continuous outcomes as weighted mean difference (WMD), both with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Analyses were performed by intention‐to‐treat where possible. Heterogeneity was tested using the Z score and Chi square with significance being set at p < 0.10. Whenever there was significant heterogeneity, the random effects model was used. The analyses were carried out using Statistical analysis of the Cochrane software.

We were limited by the number of trials identified and the heterogeneity of participants and interventions; meta‐analysis and the pre‐specified subgroup or sensitivity analyses were not performed.

Results

Description of studies

We completed searches of electronic databases and journals combined with bibliographic searches in December 2004. Forty‐two studies were excluded; the reasons described in the table 'Characteristics of excluded studies'. The majority of the excluded studies were case series without control: three were observational studies (Jiang 2003; Li 1996; Lin 2002), and two were randomized trials (Gowdey 1995; James 2000). One randomized trial aimed to treat AIDS‐related leukaemia, and relevant outcomes to this review were not reported (Gowdey 1995). Another randomized trial tested marijuana (James 2000) and will be included in an accompanying Cochrane review on cannabis. Three conference abstracts were identified that reported three randomized trials were eligible to be included (Durant 1997; Hellinger 1996; Sangkitporn 2004). We got further information from one of the investigators from correspondence with the trialists (Durant 1997). In total, we included nine randomized, placebo‐controlled trials that were eligible for this review (Burack 1996a; Durant 1997; Durant 1998; Hellinger 1996; Holodniy 1999; Paice 2000; Sangkitporn 2004; Shi 2003; Weber 1999). They tested eight different kinds of herbal medicines in a total of 499 patients with HIV infection or AIDS (Table 1). The basic characteristics of the included trials were listed in the table 'Characteristics of included studies'. One trial was underway (Tian 2002). They were heterogenous in terms of the participants, interventions, and outcomes. Our additional search in Chinese database TCMLARS recommended by one of the peer reviewers did not find any further eligible trial.

1. The preparation and composition of herbal medicines in the included trials.

| Name | Preparation | Composition | Study ID |

| '35 herbs' | pills | Preparation from 35 herbs including: Ganoderma lucidum, Isatis tinctoria, Milletia reticulata, Astragalus membranaceus, Tremella fuciformis, Andrographis paniculata, Lonicera japonica, Aquilaria agallocha, Epimedium macranthum, Oldenladia diffusa, Cistanche salsa, Lycium chinense fructus, Laminaria japonica, Angelica sinensis, Polygonum cuspidatum, Panax quinquefolium, Schizandra chinensis, Ligustrum lucidum, Atractylodes macrocephala, Rehmannia glutinosa, Salvia miltiorrhiza, Curcuma longa, Viola yedonensis, Citrus reticulata, Paeonia lactiflora, Polygonum multiflorum, Eucommia ulmoides, Amomum villosum, Glycyrrhiza uralensis, Prunella vulgaris, Cordyceps sinensis, Pogostemum cablin, Crataegus cuneata, Massa medica fermentata, Hordeum vulgare, Oryza sativa, plus magnesium stearate, silicon dioxide, and gum acacia as tableting agents. | Weber 1999 |

| IGM‐1 (Chinese herbal treatment) | tablet | A standardised preparation of 31 Chinese herbs developed by one of the investigators. Of 31 herbal ingredients in the 650 mg tablet, those present in high concentration included Ganoderma lucidum, Isatis tinctoria, Astragalus membranaceus, Andrographis paniculata, Lonicera japonica, Milletia reticulata, Oldenlandia diffusa, and Laminaria japonica. | Burack 1996 |

| Capsaicin | cream | A natural substance derived from chili peppers of the Solanaceae family in a form of commercially available cream (containing 0.075% of capsaicin) produced by Zostrix‐HP; Gen‐Derm Corporation, Lincolnshire, IL, USA. | Paice 2000 |

| Chinese herbal compound SH | capsule | Herbal extracts from five Chinese medicinal herbs screening from more than 1000 herbs. | Sangkitporn 2004 |

| Curcumin | tablet | A plant extract from spice Turmeric. | Hellinger 1996 |

| Qiankunning | tablet | An herbal compound of extracts from 14 herbs: Gardeniae jasminoidis, Artemisiae yinchenhao, Rhizoma coptidis, Forsythiae suspensae, Cnidii monnieri, Astragalus membranaceus, Rhizoma polygonati, Poriae cocos, Sparganii stoloniferi, Curcumae ezhu, Corydalis yanhusuo, Scrophulariae ningpoensis, Rhizoma Arisaematis, Rhois chinensis. | Shi 2003 |

| SP‐303 (Provir) | capsule | Containing proanthocyanidin oligomer that is isolated and purified from the latex of Croton lechleri (family Euphorbiaceae). | Holodniy 1999 |

| SPV30 | capsule | A preparation of Boxwood (Buxus sempervirens L.), a plant listed in the French Pharmacopoeia (10th edition). | Durant 1997 Durant 1998 |

One pilot trial tested a Chinese herbal formulation (IGM‐1) composed of 31 herbs (Table 1) in 30 HIV‐infected adults with symptoms and decreased CD4 cell count (200‐499/mm3) for treatment of HIV‐related symptoms (Burack 1996a). The herbal preparation was prescribed by one of the investigators, and the treatment duration was 12 weeks. There were no statistically significant differences between the treatment groups with respect to any of the baseline demographic variables examined, including age, gender, race, weight, receiving antiretrovirals, CD4 count, haemoglobin, initial health perception, functional status, cognitive function, and quality of life scales.

Interestingly, three years after the above trial was published, the same investigator who prescribed IGM‐1 prescribed another Chinese herbal formulation that was tested in a trial in Switzerland (Weber 1999). The formulation was composed of 35 Chinese herbs containing most of the herbs listed in IGM‐1 (Table 1). A trial tested the Chinese herbal formulation in 68 HIV‐infected adults with decreased CD4 cell count (less than 500/mm3) for a treatment period of six months (Weber 1999). Over 70% of the patients had received previous antiretroviral therapy. The treatment group and placebo group were similar at the study entry with respect to sociodemographic characteristics, clinical findings, median psychosocial test scores, median CD4 cell counts, plasma viral loads, and other clinical laboratory tests as well as number of patients receiving concomitant antiretroviral therapy.

A preparation called SPV30 is made from an herb Buxus sempervirens L. (boxwood) listed in the French Pharmacopoeia (10th edition). It was identified as containing active ingredients such as alkaloids and flavonoids (Durant 1997; Durant 1998). A pilot study was done on SPV30 at a dose of 990 mg/day for 30 weeks in 43 asymptomatic HIV‐positive people in 1992 (Durant 1997). Based on the findings, a multicenter three‐arm randomized trial tested SPV30 in 145 HIV‐infected asymptomatic adults for its efficacy and safety (Durant 1998). Two dosages (990 mg/day and 1980 mg/day) of SPV30 for an average of 37 weeks were compared with placebo respectively. The demographic and biological characteristics of the treatment groups were similar at entry with respect to age, gender, weight, risk factors, CD4 cell count, and viral load.

An extract from spice turmeric called curcumin was tested in two doses (4800 mg/day versus 2700 mg/day for eight weeks) in 40 HIV‐positive people (Hellinger 1996).

Another multicenter trial tested extracts (SP‐303) from a medicinal plant Croton lechleri in 51 AIDS patients with chronic diarrhoea for symptomatic treatment of diarrhoea (Holodniy 1999). Of the 51 patients, 94% had no recognized pathogen identified from stool screening. There were no significant differences between the treatment arms with respect to any of the baseline demographic variables examined, including age, gender, race, past medical history, stool output history, CD4 count, or viral load. The primary efficacy parameters were stool weight and abnormal stool frequency.

SP‐303 is a proanthocyanidin oligomer that has been isolated and purified from the latex of Amazonian plant Croton lechleri. The latex from the plant is widely known for its medicinal properties, including use for diarrhoea in South America (Holodniy 1999).

Qiankunning, an herbal extract from 14 different herbs (Table 1), is produced by the Enwei Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Sichuan, China. A recently published Chinese trial tested Qiankunning in 36 male adults with HIV infection or AIDS (Shi 2003). Age, body weight, average duration of drug use, and pre‐trial HIV‐RNA levels were claimed to be comparable (p > 0.05). The data analyses were based on participants who had completed the trial; no intention‐to‐treat analysis was applied.

A Chinese herbal compound called SH that contains five herbs was combined with zidovudine and zalcitabine in the treatment of 60 HIV‐infected Thai patients in a randomized trial (Sangkitporn 2004). The compound was composed of a formula screened from more than 1000 medicinal herbs from 120 plant families by Kunming Insitute of Botany of the China Academy of Science. Original data of relevant outcome were not available from the abstract, and there was no response from correspondence with the investigators.

Capsaicin (a topical cream prepared from chili peppers of Solanaceae) was tested against placebo for relieving pain in 26 participants with HIV‐related peripheral neuropathy (Paice 2000). The outcome measured was pain, sensory perception, quality of life, mood, and function.

Majority of the included trials reported outcome of adverse events.

Risk of bias in included studies

Eight included trials were double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group, randomized studies, and one was an open‐label trial. Among them, five trials were multicenter studies (Durant 1997; Durant 1998; Holodniy 1999; Paice 2000; Sangkitporn 2004). Five trials published in full‐text journals had adequate methods for generation of the random allocation sequence, and three reported an adequate allocation concealment (Durant 1998; Shi 2003; Weber 1999;). Blinding was adequate in the five trials for subjects including participants, investigators, and care providers. Five trials reported numbers and reasons of withdrawal/dropouts, and three used intention‐to‐treat principle in their data analyses (Burack 1996a; Durant 1998; Weber 1999). We had insufficient information from the trials published only in abstract form for assessing their methodological quality (Durant 1997; Hellinger 1996; Sangkitporn 2004). The sample size ranged from 26 to 145 patients (11 to 49 per arm). Overall, the methodological quality of the trials in full publication was adequate.

Effects of interventions

Due to each trial testing different herbal preparations, we did not perform meta‐analyses. The number of trials identified precluded pre‐specified sensitivity or subgroup analyses.

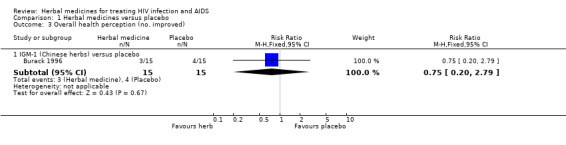

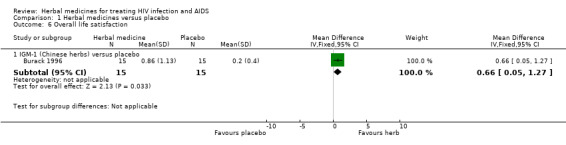

IGM‐1 (Chinese herbs): Thirty patients with at least two HIV‐related symptoms were randomly assigned to receive herbs (n = 15) or placebo (n = 15) (Burack 1996a). Overall life satisfaction (scored from 1 to 7; 1 = terrible, 7 = delightful) appeared to be improved in patients treated with herbs (WMD 0.66, 95% CI 0.05 to 1.27; p = 0.03) compared with placebo. The number of symptoms was reduced in patients receiving herbs (‐2.2, 95% CI ‐4.1 to ‐0.3), but not in those receiving placebo (‐0.3, 95% CI ‐3.2 to 2.7). This finding was based on an analysis of data between baseline and end‐of‐treatment comparisons within groups. The trial report did not provide us primary data for comparison between the two groups. There was no significant reported difference between treatment groups in overall health perception, symptom severity, absolute CD4 count, anxiety or depression. No other relevant outcomes were reported.

No adverse events were reported or detected among subjects randomized to herbs.

Chinese medicinal herbs ('35 herb'): Sixty‐eight HIV‐infected adults were randomized to receive a preparation of 35 Chinese herbs (n = 34) or placebo (n = 34) (Weber 1999); however, fifty‐three (78%) patients completed a six‐month treatment, including 24 in the herb group and 29 in the placebo group. Analyses were based on completer data and on intention‐to‐treat principle in the trial report. There were no significant differences between the groups regarding CD4 cell counts and HIV‐1 RNA load (comparison 01‐04 and 05) on intention‐to‐treat analysis. There were no significant differences between the groups regarding new AIDS‐defining events (1/34 versus 1/34), number of reported symptoms, psychosocial measurements, or quality of life.

The occurrence of adverse effects was higher in the herb group (19/24) than in the placebo group (11/29) (79% versus 38%, p = 0.003). The total number of reported adverse effects was 46 in the herb group and 20 in the placebo group and included diarrhoea, increased number of daily bowel movements, abdominal pain, constipation, flatulence, and nausea. Haematologic or serum chemistry laboratory values showed no evidence of toxicity from the study drugs; however, two patients in the herb group died during the study period, and the causes of death were believed to be due to severe immunodeficiency and pre‐enrollment history of multiple severe opportunistic complications not related to the study medication.

Chinese herbal compound SH: The herbal compound SH was combined with zidovudine and zalcitabine in the treatment of 60 HIV‐infected Thai patients (Sangkitporn 2004). The trial found that adding the SH compound to the two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors led to greater antiviral activity than in the antiretrovirals without SH; however, this benefit needs to be considered with caution because the number of patients in this trial was small, and we did not have raw data from the trial report.

Curcumin: Forty HIV‐positive people treated by two doses of oral curcumin showed no significant difference in decrease of viral load or change of CD4 cell counts during eight weeks of therapy (Hellinger 1996) .

Qiankunning: Thirty‐six male adults with HIV infection or AIDS were randomized to receive Qiankunning (n = 18) or placebo (n = 18) (Shi 2003). The Chinese herbal preparation is composed of 14 herbs (Table 1). Among the outcomes reported, data of HIV‐1 RNA levels were available. An intention‐to‐treat analysis showed that there was no significant difference in HIV‐1 RNA levels between Qiankunning and placebo (WMD ‐0.16, 95% CI ‐0.52 to 0.20) after the end of seven months' treatment. There was also no significant difference between the treatment groups (WMD ‐0.16, 95% CI ‐0.55 to 0.23) based on completer data analysis. We could not perform data analysis on CD4 cell count due to inadequate reporting.

Two patients from the Qiankunning treatment developed adverse effects. One patient had mild stomach discomfort during the early treatment. The other patients appeared to experience mild stomach discomfort and diarrhoea, but the symptoms disappeared after 10 days treatment. No adverse effects were reported from the placebo group. There were no serious adverse events observed.

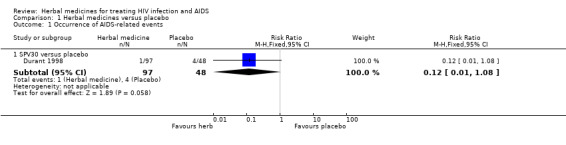

SPV30: In a pilot trial in France (Durant 1997), 43 asymptomatic HIV patients with CD4 cell counts between 250 and 500/mm3 were included in the SPV30 group (n = 22) and placebo group (n = 21). The results showed that patients receiving SPV30 had a lower risk for progressing to AIDS‐related complications and a decrease of CD4 cell count below 200/mm3. There was a significant increase of CD4 cell count in people treated by SPV30 after 30 weeks compared with placebo. Based on these findings, 145 previously untreated participants with asymptomatic HIV infection and decreased CD4 cell count (250‐500/mm3) were randomized to SPV30 990 mg/day (n = 48), SPV30 1980 mg/day (n = 49), or placebo (n = 48) (Durant 1998). There was a tendency for AIDS‐defining events such as candidiasis, herpes zoster, weight loss, and diarrhoea to occur less frequently in the SPV30 group (combination of two dosages) than in the placebo group (RR 0.12, 95% CI 0.01 to 1.08; p = 0.06). For the outcome of the number of participants who developed CD4 cell count less than 200/mm3, there was no significant difference between SPV30 and placebo. There was no significant difference between either SPV30 990 mg/day or SPV30 1980 mg/day and placebo with respect to CD4 cell counts and viral load.

There were no reported significant differences among the groups regarding adverse effects in the trial reports. The trial did not observe serious adverse effects, and biochemical parameters did not show abnormal changes in the participants.

SP‐303: In the SP‐303 trial, 51 patients with AIDS and diarrhoea were randomized to receive SP‐303 (n = 26) or placebo (n = 25) (Holodniy 1999). According to an analysis of the treatment effect over four days based on daily measurements by random regression models, patients treated with SP‐303 experienced a statistically significant reduction in stool weight (p = 0.008) and in abnormal stool frequency (p= 0.04) when compared with placebo. The trial also reported outcome of stool chloride concentration. No other relevant outcomes were reported.

The trial reported that treatment with SP‐303 was well tolerated, with no major difference between SP‐303 and placebo in the occurrence of adverse events or in laboratory abnormalities. No data were provided in the trial report. There were no serious adverse events reported in either treatment group.

Capsaicin: In a small multicenter trial of participants with HIV‐related peripheral neuropathy (Paice 2000), topical application of capsaicin for four weeks did not show beneficial effect regarding pain intensity, pain relief, sensory perception, quality of life, mood, or function compared with placebo; however, the trial reported a large proportion (46%) of participants dropped out (67% in capsaicin group compared with 18% in placebo group).

No adverse events were reported from Chinese herbs in two observational studies (Li 1996; Lin 2002).

Discussion

Our review identified only nine trials of eight different herbal remedies in people with HIV or AIDS patients. A pilot trial showed a positive effect on CD4 cell count from SPV30; however, a later trial of SPV30 did not confirm the benefit and found only a borderline effect on the development of AIDS‐related complications. One herbal treatment SP‐303 was found to be effective in decreasing the frequency and weight of diarrhoeal stools among AIDS patients with diarrhoea. The apparent beneficial effect of adding the Chinese herbal compound SH to two antiretroviral agents needs to be confirmed in large trial.

A previous systematic review published in 1999 identified only two randomized trials on herbal medicines for HIV infection (Ozsoy 1999). Our searches for trials, including a search of the Chinese language literature, ended in December 2004. Few trials on herbal medicines for treating HIV infection and AIDS have been conducted and reported during the past five years. Many clinical reports are case series without controls. In this review, nine included trials tested four different Chinese herbal compounds, one European herbal preparation (SPV30), two American spice extracts, and one South American herbal preparation (SP‐303). Three out of the nine trials concluded with positive findings and suggest promising effects from three herbal medicines. Unpublished data from the Enwei Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Sichuan, China, claimed beneficial effects from Qiankunning (Enwei 2002); however, our analysis from a later published trial report (Shi 2003) did not confirm the claim either by intention‐to‐treat or by completer data.

A recent study examined the effects of two African herbs widely used against HIV‐AIDS in Africa on antiretroviral metabolism, and it showed that extracts from Hypoxis hemerocallidea and Sutherlandia inhibited cytochrome P450 metabolism and P‐glycoprotein expression (Mills 2005). The study highlights the importance of undertaking pharmacokinetic studies to unveil potential interaction of herbal medicines and antiretroviral agents. Failure to undertake such studies may result in drug interactions, treatment failure, resistant HIV, and drug toxicities (Mills 2005).

This review shows several limitations. First, all included trials were quite small in size, which may cause random error for both positive and negative findings. Second, although we did a comprehensive search the majority of included trials were published studies, while unpublished abstracts provided insufficient information on data. There may be other studies remaining unpublished and thus missing from this review. Third, there are large variations among tested herbal remedies. Only one herbal preparation has been tested twice, but it resulted in inconsistent findings. The treatment duration is not long enough for end‐point outcomes such as mortality or new AIDS‐related events.

In summary, the Chinese herbal preparation IGM‐1 may contribute to improved quality of life and a decrease of symptoms among HIV‐infected patients with symptoms (Burack 1996a). A four‐day treatment using SP‐303 (extract from the Amazonian plant Croton lechleri) may have an effect in reducing abnormal stool frequency in patients with AIDS and diarrhoea (Holodniy 1999). A promising antiviral benefit was found from the Chinese herbal compound SH combined with antiretroviral agents (Sangkitporn 2004). Other herbal preparations tested in trials did not find statistically significant effects on quality of life, clinical manifestations, viral load, or CD4 cell counts between the herbs and placebo (Durant 1998; Paice 2000; Shi 2003; Weber 1999). The use of herbal remedies are associated with non‐serious adverse effects; however, potential risk of the interaction between herbs and antiretroviral agents warrants caution.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

It is very common for HIV‐infected individuals and AIDS patients to seek complementary therapies, especially herbal remedies. This systematic review finds insufficient evidence to support the use of herbal medicines for HIV infection or AIDS. Small to moderate effects for care of HIV/AIDS from three trials in this review need to be verified in large trials.

Implications for research.

Future trials of herbal medicines for HIV/AIDS should be large and should take account of clinical outcomes, such as progression to AIDS or AIDS‐related illness and quality of life. Since studies have demonstrated the relationship between plasma HIV RNA loads, CD4 cell counts, and disease progression in HIV infection, it is worthwhile to include these surrogate outcomes in trials. Potential interaction between herbs and antiretroviral agents warrants caution.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2002 Review first published: Issue 3, 2005

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 April 2005 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Gail Kennedy and Dr George W Rutherford and the anonymous peer reviewers of the Cochrane HIV/AIDS Group for their help and input in the development of the protocol and review, and Dr Heather Dubnick for providing useful comments on the review. We are also grateful to Dr J Durant for providing further information on their trials.

Eric Manheimer was funded by Grant Number R24 AT001293 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCCAM or the National Institutes of Health.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Herbal medicines versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Occurrence of AIDS‐related events | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 SPV30 versus placebo | 1 | 145 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.12 [0.01, 1.08] |

| 2 CD4 cell count less than 20 millions per litre | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 SPV30 versus placebo | 1 | 145 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.33, 1.69] |

| 3 Overall health perception (no. improved) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 IGM‐1 (Chinese herbs) versus placebo | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.20, 2.79] |

| 4 CD4 cell count ( X 10 6/L) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 SPV30 (990 mg/day) versus placebo | 1 | 96 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 39.70 [‐14.00, 95.40] |

| 4.2 SPV30 (1980 mg/day) versus placebo | 1 | 97 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 16.0 [‐35.12, 67.12] |

| 4.3 Chinese medicinal herbs versus placebo | 1 | 68 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐80.0 [‐183.25, 23.25] |

| 5 Viral load (log unit or copies/ml) | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 SPV30 (990 mg/day) versus placebo | 1 | 77 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [‐0.22, 0.44] |

| 5.2 SPV30 (1980 mg/day) versus placebo | 1 | 79 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.15 [‐0.49, 0.19] |

| 5.3 Chinese medicinal herbs versus placebo | 1 | 68 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 20117.0 [‐29673.20, 69907.20] |

| 5.4 Qiankunning versus placebo | 1 | 36 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.16 [‐0.52, 0.20] |

| 6 Overall life satisfaction | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 IGM‐1 (Chinese herbs) versus placebo | 1 | 30 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.05, 1.27] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Herbal medicines versus placebo, Outcome 1 Occurrence of AIDS‐related events.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Herbal medicines versus placebo, Outcome 2 CD4 cell count less than 20 millions per litre.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Herbal medicines versus placebo, Outcome 3 Overall health perception (no. improved).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Herbal medicines versus placebo, Outcome 4 CD4 cell count ( X 10 6/L).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Herbal medicines versus placebo, Outcome 5 Viral load (log unit or copies/ml).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Herbal medicines versus placebo, Outcome 6 Overall life satisfaction.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Burack 1996.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐ controlled trial. Generation of allocation sequence: random number. Double blind: study personnel and subjects. Withdrawal/dropouts: numbers and reasons reported. Intention to treat analyses: yes. | |

| Participants | Study country: USA.

Setting: HIV/AIDS clinics.

30 HIV positive persons with decreased CD4 cell count and currently experiencing at least two HIV‐related symptoms without prior AIDS‐defining diagnosis by 1987 CDC criteria (15 in herb group and 15 in placebo group). Exclusion criteria: subjects with a history of sensitivity to Chinese herbs; active opportunistic infection; any significant hematologic, renal, or hepatic laboratory abnormalities; presently receiving herbal treatment or used herbs in the past six months; or participating in a blinded antiviral drug trial. |

|

| Interventions | Experiment:

IGM‐1 (a standardized oral preparation of Chinese herbs), seven pills four times daily (650 mg), for 12 weeks. Control: Placebo, the same regimen as above. |

|

| Outcomes | Symptoms, perceptions, physical and social function, mental health, depression, anxiety, body weight, CD4 counts, quality of life, adherence, and adverse events. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Durant 1997.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Generation of allocation sequence: unclear. Double blind: not specified. Withdrawal/dropouts: not reported. Intention to treat analyses: yes. | |

| Participants | Study country: France. Setting: hospitals. 43 asymptomatic HIV positive patients with CD4 cell counts between 25 and 50 millions per litre (22 in SPV30 (990 mg/day) group, and 21 in placebo group). Diagnostic criteria not described. | |

| Interventions | Experiment:

SPV30 (Buxus sempervirens L. preparations), two capsules (165 mg each) every eight hours daily (990 mg/d), for 30 weeks. Control: Placebo, two capsules every eight hours, for 30 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | AIDS related complex; CD4 cell count , and adverse events. | |

| Notes | Raw data were not available from the abstract. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Durant 1998.

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐ controlled trial. Generation of allocation sequence: computer generated randomisation code. Double blind: study personnel and subjects. Withdrawal/dropouts: numbers and reasons reported. Intention to treat analyses: yes. | |

| Participants | Study country: France. Setting: hospitals. 145 HIV positive patients with CD4 cell counts between 25 and 50 millions per litre, and without symptoms (49 in SPV30 (1980 mg/day) group, 48 in SPV30 (990 mg/day) group, and 45 in placebo group). Diagnostic criteria not described. | |

| Interventions | Experiment:

SPV30 (Buxus sempervirens L. preparations), two capsules (165 mg each) every eight hours daily (990 mg/d), for 37 weeks (median treatment duration). SPV30: two capsules (330 mg each) every eight hours daily (1980 mg/d); for 38 weeks (median treatment duration). Control: Placebo, two capsules every eight hours, for 37 weeks (median treatment duration). |

|

| Outcomes | Therapeutic failures defined by the occurrence of one of the following: 1) AIDS; 2) AIDS related complex; 3) decrease of CD4 cell count < 200 times six squares per litre twice, viral load, and adverse events. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Hellinger 1996.

| Methods | Randomised, open‐label, placebo‐controlled trial. Generation of allocation sequence: unclear. Double blind: not used. Withdrawal/dropouts: unclear. Intention to treat analyses: unclear. | |

| Participants | Study country: USA. Setting: unclear. 40 HIV‐positive people into two doses of curcumin groups or placebo group. | |

| Interventions | Experiment:

Curcumin(extract from spice turmeric), 4800 mg/day oral, for eight weeks; Curcumin, 2700 mg/day orally, for eight weeks. Control: Placebo, the same regimen as above. |

|

| Outcomes | HIV viral load, CD4 cell count. | |

| Notes | Raw data were not available from the abstract. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Holodniy 1999.

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Generation of allocation sequence: table of random numbers. Double blind: study personnel and subjects. Withdrawal/dropouts: unclear. Intention to treat analyses: unclear. | |

| Participants | Study country: USA. Setting: hospital‐based inpatients. 51 AIDS patients with diarrhoea (26 in SP‐303 group and 25 in placebo group). AIDS diagnosed by CDC criteria. | |

| Interventions | Experiment:

SP‐303 (herbal extract from Croton lechleri), two capsules (500 mg) oral, every 6 hours, for a total of 16 consecutive doses (32 capsules); Control: Placebo, two capsules, the same regimen as above. 41 out of 51 patients received antiretroviral therapy and 39 received at least one protease inhibitor during herbal therapy. |

|

| Outcomes | Stool weight, abnormal stool frequency, stool chloride output, daily gastrointestinal index score, and adverse events. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Paice 2000.

| Methods | Multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Generation of allocation sequence: unclear. Double blind: stated but no information about who were blinded. Withdrawal/dropouts: 12 participants (46%) dropped out before the end of 4 weeks period. Intention to treat analyses: no. | |

| Participants | Study country: USA. Setting: two hospital‐based inpatients and outpatients. 26 participants with HIV‐related DSPN (distal symmetrical peripheral neuropathy) (15 in capsaicin group and 11 in placebo group). Diagnostic criteria not described. | |

| Interventions | Experiment:

Capsaicin (chili peppers of the Solanaceae) cream (0.075%), topical use, 4 times daily for 4 weeks; Control: Placebo (only vehicle of the cream), topically 4 times daily for 4 weeks. Co‐intervention: usual analgesic therapy in both arms. |

|

| Outcomes | Pain intensity, pain relief, sensory perception, quality of life, mood and function. | |

| Notes | Containers were used for tested drug or placebo. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Sangkitporn 2004.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Generation of allocation sequence: unclear. Double blind: not specified. Withdrawal/dropouts: not reported. Intention to treat analyses: unclear. | |

| Participants | Study country: Thailand. Setting: five hospitals. 60 adults with HIV‐1 infected (40 in herb group and 20 in placebo group). | |

| Interventions | Experiment:

Chinese herbal compound SH (composed of five herbs), 2.5 g orally; plus ZDV 200 mg, ddC 0.75 mg; three times per day, for 24 weeks. Control: Placebo, 2.5 g, plus ZDV 200 mg, ddC 0.75 mg, orally, three times per day, for 24 weeks. |

|

| Outcomes | CD4 cell counts, HIV RNA, and adverse events. | |

| Notes | Raw data were not available from the abstract. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Shi 2003.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Generation of allocation sequence: random number table. Double blind: study personnel and subjects. Withdrawal/dropouts: numbers and reasons reported. Intention to treat analyses: no. | |

| Participants | Study country: China. Setting: not stated. 36 male adults of intravenous drug users including HIV‐infected and AIDS patients (18 in herb group and 18 in placebo group). HIV infection and AIDS were diagnosed by CDC criteria in 1993. | |

| Interventions | Experiment:

Qiankunning ( extracts from 14 herbs), four tablets orally, three times daily, for consecutive seven months. Control: Placebo, four tablets orally, three times daily, for consecutive seven months. After seven months treatment, all patients received Qiankunning (six tablets, thrice daily) for another three months. During the treatment period, all other drugs were stopped. There is no information about quality standard of the preparations. |

|

| Outcomes | CD4 cell counts, viral loads, and adverse events. The outcomes were assessed during treatment bimonthly and at the end of the treatment. |

|

| Notes | Five patients from herb group and one patient from placebo group were lost during treatment because of relocation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Weber 1999.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐ controlled trial. Generation of allocation sequence: computer programme. Double blind: study personnel and subjects. Withdrawal/dropouts: numbers and reasons reported. Intention to treat analyses: yes. | |

| Participants | Study country: Switzerland. Setting: HIV outpatient clinic. 68 HIV‐infected adults with reduced CD4 cell counts (34 in herb group and 34 in placebo group). HIV diagnosis criteria not described. | |

| Interventions | Experiment:

Chinese herbs (35 different herbs), seven pills oral, four times daily, for six months. Control: Placebo, the same regimen as above. All participants continued their previous treatment during the trial. |

|

| Outcomes | CD4 and CD8 cell counts, viral loads, quality of life, adverse events, and safety (hematologic tests and chemistry variables). | |

| Notes | 24 in herb group and 29 in placebo group finished the study. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Calabrese 2000 | A phase I trial of Andrographolide (major active constituent of Andrographis paniculata) in 13 HIV positive patients to assess safety, tolerability, and effects on HIV‐1 RNA levels and CD4+ lymphocyte levels. |

| Cohen 2000 | Case series. |

| Gowdey 1995 | Randomised controlled trial testing extracted resin from plant podophyllum for treating leukoplakia in HIV infected patients. The outcome relevant to the review was not reported. |

| Guan 2003 | Case series. |

| Guo 1994 | Case series. |

| Huang 1998a | Case series. |

| Huang 1998b | Case series. |

| Huang 1998c | Case series. |

| Huang 1999 | Case series. |

| Huang 2002 | Case series. |

| James 2000 | Randomised controlled trial comparing marijuana versus dronabinol versus placebo in three arms. This trial is excluded from this review but will be included in another separate review. |

| Jia 1998 | Case series. |

| Jiang 2003 | Observational study to compare Chinese medicine with symptomatic treatment in 27 individuals with HIV infection or AIDS patients. |

| Kang 1999a | Case series. |

| Kang 1999b | Case series. |

| Kusum 2004 | Case series. |

| Li 1993 | Observational study to compare five different Chinese medicines with integrated Chinese and western medicine in 80 AIDS patients with respiratory infections. |

| Li 1996 | Observational study to compare traditional Chinese medicine alone with integrated traditional Chinese and western medicine in 80 AIDS patients with respiratory infections. |

| Li 1997 | Case series. |

| Li 1998 | Case series. |

| Lin 2002 | Observational study in 73 cases of HIV infected persons treated with cocktail therapy in 6 patients, Chinese herbs in 36 patients, and no treatment in 31 patients. |

| Liu 1999 | Case series. |

| Liu 2000 | Case series. |

| Lu 1993 | Case series. |

| Lu 1995 | Case series. |

| Lu 1997 | Case series. |

| Lu 1998 | Case series. |

| Lu 2000 | Case series. |

| Su 1990 | Case series. |

| Sun 1999 | Case series. |

| Tani 2002 | Case series. |

| Tshibangu 2004 | Case series. |

| Wang 2000 | Case series. |

| Wang 2001 | Case series. |

| Wei 2001 | Case series. |

| Wu 1992 | Review article. |

| Yang 1999 | Case series. |

| Zhan 2000 | Case series. |

| Zhang 1999 | Case series. |

| Zhao 1996 | Case series. |

| Zhao 1997 | Case series. |

| Zheng 1999 | Case series. |

Contributions of authors

Jianping Liu: Review conceiving, protocol and search strategy development, study selection, quality assessment and data extraction, data analysis, development of final review, corresponding author. Eric Manheimer: Co development of search strategy, searching for trials, selecting studies, assessing quality of trials, co development of final review. Min Yang: Searching for trials, selecting studies, assessing quality of trials, extracting data, and co development of final review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

National Research Centre in Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NAFKAM), Norway.

External sources

Pilot Fund for Chinese Oversea Scholars, Ministry of Education, China.

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (grant number 1 R24 AT001293‐01), USA.

Declarations of interest

We certify that we have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity that has direct or indirect financial interest in the subject matter of the review.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Burack 1996 {published data only}

- Burack JH, Cohen MR, Hahn JA, Abrams DI. Pilot randomized controlled trial of Chinese herbal treatment for HIV‐associated symptoms. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome Human Retrovirology 1996;12(4):386‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Durant 1997 {published data only}

- Durant J, Rebouillat A, Dellamonica P, Condom R, Patino N, Pugliese P, et al. Efficacy of SPV on asymptomatic HIV‐positive patients: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo controlled trial. IV Congress of the Mediterranean Society of Infectious and Parasitic Diseases. Paris, 1997:P30/59.

Durant 1998 {published data only}

- Durant J, Chantre PH, Gonzalez G, Vandermander J, Halfon PH, Rousse B. Efficacy and safety of Buxus semperirens L. preparations (SPV 30) in HIV‐infected asymptomatic patients: a multicentre, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Phytomedicine 1998;5(1):1‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hellinger 1996 {published data only}

- Hellinger JA. Phase I/II randomized, open‐label study of oral curcumin safety, and antiviral effects on HIV‐RT PCR in HIV+ individuals. Third Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic infections. Washington, 1996:140.

Holodniy 1999 {published data only}

- Holodniy M, Koch J, Mistal M, Schmidt JM, Khandwala A, Pennington JE, et al. A double blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled phase II study to assess the safety and efficacy of orally administered SP‐303 for the symptomatic treatment of diarrhea in patients with AIDS. American Journal of Gastroenterology 1999;94(11):3267‐73. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Paice 2000 {published data only}

- Paice JA, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR, Shott S, Vizgirda V, Pitrak D. Topical capsaicin in the management of HIV‐associated peripheral neuropathy. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2000;19(1):45‐52. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sangkitporn 2004 {published data only}

- Sangkitporn DR, Luo SD, Klinbuayaem DR, Leenasirimakul DR, Wirayutwatthana DR, Leechanachai DR, et al. Efficacy and safety of Zidovudine and Zalcitabine combined with combination of herbs in the treatment of HIV‐infected Thai patients. Abstract of XV International AIDS Conference. Bankok, Thailand, July, 2004:B10233.

Shi 2003 {published data only}

- Shi D, Peng ZL. Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical study on Qiankunning for HIV/AIDS. Study Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2003;21(9):1472‐4. [Google Scholar]

Weber 1999 {published data only}

- Weber R, Christen L, Loy M, Schaller S, Christen S, Joyce CR, et al. Randomized, placebo‐controlled trial of Chinese herb therapy for HIV‐infected individuals. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome 1999;22(1):56‐64. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Calabrese 2000 {published data only}

- Calabrese C, Berman SH, Babish JG, Ma X, Shinto L, Dorr M, et al. A phase I trial of Andrographolide in HIV positive patients and normal volunteers. Phytotherapy Research 2000;14:333‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cohen 2000 {published data only}

- Cohen MR, Mitchell TF, Bacchetti P, Chil C, Crawford S, Gaeddert A, et al. Use of a Chinese herbal medicine for treatment of HIV‐associated pathogen‐negative diarrhea. Integrative Medicine 2000;2(2):79‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gowdey 1995 {published data only}

- Gowdey G, Lee RK, Carpenter WM. Treatment of HIV‐related hairy leukoplakia with podophyllum resin 25% solution. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1995;79(1):64‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guan 2003 {published data only}

- Guan CF, Wang J, Xu SL, Yu ZM, Zhang YX, Li GQ, et al. Clinical and experimental study on treatment of HIV/AIDS patients by Zhongyan No. 2. Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine 2003;23(7):494‐7. [Google Scholar]

Guo 1994 {published data only}

- Guo QS. Effect of Garlic in AIDS: treatment report of 98 cases. General Clinical Medicine 1994;10(3):163. [Google Scholar]

Huang 1998a {published data only}

- Huang RZ, Zhang LX, Liu G, Huang WP, Jia XY, Naomi Mpemba. Clinical observation on 16 cases of AIDS complicated with herpas zoster treated with Ji Desheng's snake‐venom remedy. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1998;39(12):726‐7. [Google Scholar]

Huang 1998b {published data only}

- Huang RZ, Zhang LX, Huang WP, Liu G, Jin LX, Jia XY. Clinical observation on 12 cases of AIDS thrush treated by Gargling with Gemma Agrimoniae powder. Chinese Journal of Information on Traditional Chinese Medicine 1998;5(11):33‐4. [Google Scholar]

Huang 1998c {published data only}

- Huang RZ, Zhang LX, Liu G, Huang WP, Liu H, Jia XY, et al. Clinical observation of 13 cases of AIDS treated by Hongmao Wujia polysaccharide. Chinese Journal of Information on Traditional Chinese Medicine 1998;5(10):32‐3. [Google Scholar]

Huang 1999 {published data only}

- Huang WP, Lu WB, Huang RZ, Zhang WX, Liu G, Jia XY, et al. Clinical observation on 22 cases of HIV infection treated with Ai Tong. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1999;40(10):606‐8. [Google Scholar]

Huang 2002 {published data only}

- Huang WP, Wang J, Yu ZM, Wen RX, Zhang YX. Ai Tong for treatment of 15 individuals with HIV infeciton or AIDS. Chinese Journal of Information on Traditional Chinese Medicine 2002;9(11):49‐50. [Google Scholar]

James 2000 {published data only}

- James JS. Marijuana safety study completed: weight gain, no safety problems. AIDS Treat News 2000, issue 348:3‐4. [PubMed]

Jia 1998 {published data only}

- Jia XY, Lu WB, Zhang LX, Huang RZ, Huang WP, Liu G, et al. Observation on the laboratory criteria in 10 cases infected with HIV by using Chinese traditional medicine which can invigorate the circulation of blood and reduce the thrombosis. Chinese Journal of Prevention and Control of STD & AIDS 1998;4(6):273‐4. [Google Scholar]

Jiang 2003 {published data only}

- Jiang WM, Pan JZ, Kang LY, Lu HZ, Wong XH. Evaluation of efficacy of XQ‐9302 a Chinese herb, in the treatment of HIV carriers and AIDS patients. Chinese Journal of AIDS and STD 2003;9(6):341‐2. [Google Scholar]

Kang 1999a {published data only}

- Kang LY, Pan XZ, Pan QC, Li GH, Jin ZC, Xue YL, et al. Preliminary study of Chinese herbs in the treatment of 18 cases of HIV carriers and AIDS patients. Chinese Journal of Infectious Diseases 1999;17(1):44‐6. [Google Scholar]

Kang 1999b {published data only}

- Kang LY, Pan XZ, Yang WX, Pan QC, Weng XH, Yang WQ. Chinese herbal formula XQ‐9302: pilot study of its clinical and in vitro activity against human immunodeficiency virus. Hong Kong Medical Journal 1999;5(2):135‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kusum 2004 {published data only}

- Kusum M, Klinbuayaem V, Bunjob M, Sangkitporn S. Preliminary efficacy and safety of oral suspension SH, combination of five chinese medicinal herbs, in people living with HIV/AIDS ; the phase I/II study. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand 2004;87(9):1065‐70. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Li 1993 {published data only}

- Li GQ, Lu WB, Zhou ZK, Yue YH. Clinical observation of Chinese medicine for treating AIDS patients with respiratory infection. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1993;34(11):671‐2. [Google Scholar]

Li 1996 {published data only}

- Li G, Yue Y, Lu W, Zhou Z. Clinical investigation of traditional Chinese medicine and pharmacy in treating respiratory tract infections in AIDS. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1996;16(1):3‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Li 1997 {published data only}

- Li JM. Ai moxibustion for treatment of diarrhea in 60 cases of AIDS. Yunnan Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Materia Medica 1997;18(2):29. [Google Scholar]

Li 1998 {published data only}

- Li M, Li YK, Wang K, Wu LM, Feng XZ, Li TF, et al. Extract Spring of Life (ESOL) for treatment of AIDS and its relevant syndrome. Chinese Journal of Prevention and Control of STD & AIDS 1998;Suppl:131‐5. [Google Scholar]

Lin 2002 {published data only}

- Lin XD, Xu LZ, Feng Y, Li J, Pei LJ, Shen TQ, et al. Clinical study on treatment of HIV infected persons based on viral load detection and CD4+ T lymphocyte counting. Chinese Journal of Experimental and Clinical Virology 2002;16(3):211‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Liu 1999 {published data only}

- Liu G, Lu WB. Sheng Dahuang powder for treating 9 HIV infected cases with herpes zoster infection. Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine 1999;19(2):123. [Google Scholar]

Liu 2000 {published data only}

- Liu G, Zhang WX, Huang WP, Jia XY, Huang RZ. Treatment of 38 cases of advanced AIDS patients using 'Jianpi Yishen' recipe. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2000;41(3):186. [Google Scholar]

Lu 1993 {published data only}

- Lu WB. A report of 60 cases of HIV infection by treatment of herbal medicine 'Ke Ai Ke'. Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine 1993;13(6):340‐2. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lu 1995 {published data only}

- Lu W. Prospect for study on treatment of AIDS with traditional Chinese medicine. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1995;15(1):3‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lu 1997 {published data only}

- Lu WB, Wen RX, Guan CF, Wang YZ, Shao J, Mshiu E, et al. A report on 8 seronegative converted HIV/AIDS with traditional Chinese medicine. Chinese Journal of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine 1997;17(5):271‐3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lu 1998 {published data only}

- Lu WB, Zhao XM, Guan MK, Gu YH, Huang WP, Mpemba N, et al. Clinical study on 21 Shiji Kangbao for treating 13 cases of HIV infection. China Journal of Basic Medicine in Traditional Chinese Medicine 1998;4(2):50‐1. [Google Scholar]

Lu 2000 {published data only}

- Lu WB, Tang JJ, Huang RZ, Zhao XM, Huang WP, Mu PB, et al. Clinical report of Xinshiji Kangbao for treating 43 AIDS patients. Chinese Journal of Prevention and Control of STD & AIDS 2000;6(3):168‐9. [Google Scholar]

Su 1990 {published data only}

- Su CL. Clinical report of traditional Chinese medicine for treating 30 AIDS patients. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1990;10(1):27‐30. [Google Scholar]

Sun 1999 {published data only}

- Sun Y, Wu ZP, Ni YP, An KG, Wang SY, Zhang XS. Clinical observation of treating AIDS 31 cases with Aitaiding. Chinese Journal of Ethnomedicine and Ethnopharmacy 1999;5(5):258‐61. [Google Scholar]

Tani 2002 {published data only}

- Tani M, Nagase M, Nishiyama T. The effects of long‐term herbal treatment for pediatric AIDS. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine 2002;30(1):51‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tshibangu 2004 {published data only}

- Tshibangu KC, Worku ZB, Jongh MA, Wyk AE, Mokwena SO, Peranovic V. Assessment of effectiveness of traditional herbal medicine in managing HIV/AIDS patients in South Africa. East African Medical Journal 2004;81(10):499‐504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wang 2000 {published data only}

- Wang J, Lu WB, Li GQ, Yu ZM, Pan WX, Lu Y, et al. Clinical study of Jin Sheng Bao capsule for treating 22 cases of HIV infection. Chinese Journal of Basic Medicine of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2000;6(7):33‐5. [Google Scholar]

Wang 2001 {published data only}

- Wang J, Yu Z, Li G, Zhang Y, Guan C, Lu W. Clinical observation on the therapeutic effects of zhongyan‐2 recipe in treating 29 HIV‐infected and AIDS patients. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine [English version] 2002;22(2):93‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Yu ZM, Li GQ, Zhang YX, Guan CF, Lu WB. Clinical observation on 29 cases of HIV infection and AIDS treated with Zhong Yan No. 2. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2001;42(7):418‐20. [Google Scholar]

Wei 2001 {published data only}

- Wei JA, Sun LM, Zhang W, Liu G, Tang KT, Su XY, et al. Ai Ling granule for treatment of 40 cases of HIV infected persons in ARC stage. Chinese Journal of TCM Information 2001;8(7):62‐63. [Google Scholar]

Wu 1992 {published data only}

- Wu B. Recent development of studies on traditional Chinese medicine in prophylaxis and treatment of AIDS. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1992;12(1):10‐20. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yang 1999 {published data only}

- Yang WX, Kang LY, Pan XZ, Pan QC, Yang WQ, Li HG, et al. Preliminary study on therapeutic effect of XQ‐9302 Chinese herbal preparation to AIDS. Shanghai Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1999;33(1):4‐8. [Google Scholar]

Zhan 2000 {published data only}

- Zhan L, Yue ST, Xue YX, Attele AS, Yuan CS. Effects of qian‐kun‐nin, a Chinese herbal medicine formulation, on HIV positive subjects: a pilot study. American Journal of Chinese Medicine 2000;28(3‐4):305‐12. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zhang 1999 {published data only}

- Zhang YL, Zhang TY, Chen JS. Clinical observation of Shuang Huang Lian powder injection for treatment of AIDS. Journal of Shanxi Medical University 1999;30(2):47‐8. [Google Scholar]

Zhao 1996 {published data only}

- Zhao XM, Zhou ZK. Therapeutic study on 55 AIDS patients with herpes zoster. Chinese Journal of Information on Traditional Chinese Medicine 1996;3(8):36‐7. [Google Scholar]

Zhao 1997 {published data only}

- Zhao XM, Lu WB, Guan MH. Experiences in syndrome differentiation treatment of AIDS diarrhea by administration of Ban Xia Xie Xin decoction. Chinese Journal of Information on Traditional Chinese Medicine 1997;4(5):41. [Google Scholar]

Zheng 1999 {published data only}

- Zheng WY, Pi GH, Xu KY, Hu CF, Jiang LS, Hu XF, et al. Therapeutic observation of Chinese medicine 'Zai Sheng Dan' in patients with HIV infection. Chinese Journal of Experimental and Clinical Virology 1999;13(3):291‐4. [MEDLINE: ] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

Tian 2002 {unpublished data only}

- Xinhua News Agency/BBC Monitoring Africa. Testing of herbal HIV/AIDS drug in Zambia. http://www.kaisernetwork.org/daily_reports/rep_index.cfm?DR_ID=12852 10/08/2002.

Additional references

Anonymous 2002

- Authors unknown. Evidence shows hepatitis C virus is playing major role in AIDS deaths. AIDS ALERT 2002; Vol. 17, issue 2:13‐6. [PubMed]

Bonfanti 1999

- Bonfanti P, Capetti A, Rizzardini G. HIV disease treatment in the era of HAART. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 1999;53:93‐105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Burack 1996a

- Burack JH, Cohen MR, Hahn JA, Abrams DI. Pilot randomized controlled trial of Chinese herbal treatment for HIV‐associated symptoms. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes and human retrovirology 1996;12(4):386‐93. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dorrucci 1995

- Dorrucci M, Pezzotti P, Phillips AN, Lepri AC, Rezza G. Coinfection of hepatitis C virus with human immunodeficiency virus and progression to AIDS. Italian Seroconversion Study. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1995;172(6):1503‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Durant 1998

- Durant J, Chantre Ph, Gonzalez G, Vandermander J, Halfon Ph, Rousse B. Efficacy and safety of Buxus sempervirens preparations (SPV30) in HIV‐infected asymptomatic patients: a multicentre, randomized, double‐blind, placebo controlled trial. Phytomedicine 1998;5(1):1‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eisenberg 1998

- Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Rompay MV, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990‐1997. Results of a follow‐up national survey. Journal of the American Medical Association 1998;280(18):1569‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Enwei 2002

- Anonymous. Summarized report of clinical study of Chinese medicine Qiankunning in HIV/AIDS [in Chinese]. Webpage: http://www.enwei.com.cn/medicine/products/ 2002.

Ernst 1995

- Ernst E. Complementary medicine: common misconceptions. Journal of The Royal Society of Medicine 1995;88(5):244‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ICH‐GCP 1997

- International Conference on Harmonisation Expert Working Group. Code of Federal Regulations & International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines. Pennsylvania: Parexel/Barnett, 1997. [Google Scholar]

Ishizaki 1996

- Ishizaki T, Sasaki F, Ameshima S, Shiozaki K, Takahashi H, Abe Y, et al. Pneumonitis during interferon and/or herbal drug therapy in patients with chronic active hepatitis. European Respiratory Journal 1996;9(12):2691‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Izzo 2001

- Izzo AA, Ernst E. Interactions between herbal medicines and prescribed drugs: a systematic review. Drugs 2001;61(15):2163‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jadad 1996

- Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary?. Controlled Clinical Trials 1996;17(1):1‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kjaergard 2001

- Kjaergard LL, Villumsen J, Gluud C. Reported methodological quality and discrepancies between large and small randomized trials in meta‐analyses. Annal of Internal Medicine 2001;135(11):982‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Liu 2000

- Liu G, Zhang WX, Huang WP, Jia XY, Huang RZ. Treatment of 38 cases of advanced AIDS patients using 'Jianpi Yishen' recipe. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2000;41(3):186. [Google Scholar]

Lu 1993

- Lu WB. A report of 60 cases of HIV infection by treatment of herbal medicine 'Ke Ai Ke'. Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine 1993;13(6):340‐2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Martin 2001

- Martin‐Carbonero L, Soriano V, Valencia E, Garcia‐Samaniego J, Lopez M, Gonzalez‐Lahoz J. Increasing impact of chronic viral hepatitis on hospital admissions and mortality among HIV‐infected patients. AIDS research and human retroviruses 2001;17(16):1467‐71. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Melchart 1999

- Melchart D, Linde K, Weidenhammer W, Hager S, Shaw D, Bayer R. Liver enzyme elevations in patients treated with traditional Chinese medicine. Journal of the American Medical Association 1999;282(1):28‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mills 2005

- Mills E, Foster BC, Heeswijk RV, Phillips E, Wilson K, Leonard B, et al. Impact of African herbal medicines on antiretroviral metabolism. AIDS 2005;19(1):95‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moher 1998

- Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M, et al. Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta‐analyses?. Lancet 1998;352:609‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Monga 2001

- Monga HK, Rodriquez‐Barradas MC, Breaux K, Khattak K, Troisi CL. Hepatitis C virus infection‐related morbidity and mortality among patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2001;33:240‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ozsoy 1999

- Ozsoy M, Ernst E. How effective are complementary therapies for HIV and AIDS? ‐ a systematic review. International Journal of STD & AIDS 1999;10(10):629‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schulz 1995

- Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes R, Altman D. Empirical evidence of bias. Journal of the American Medical Association 1995;273(5):408‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shafer 1999

- Shafer RW, Vuitton DA. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) for the treatment of infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 1999;53:73‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sud 2001

- Sud A, Singh J, Dhiman RK, Wanchu A, Singh S, Chawla Y. Hepatitis B virus co‐infection in HIV infected patients. Tropical Gastroenterology 2001;22(2):90‐2. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tirelli 2001

- Tirelli U, Bernardi D. Impact of HAART on the clinical management of AIDS‐related cancers. European Journal of Cancer 2001;37:1320‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vella 2000

- Vella S, Palmisano L. Antiretroviral therapy: state of the HAART. Antiviral Research 2000;45:1‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vickers 2000

- Vickers A. Recent advances: complementary medicine. The British Medical Journal 2000;321:683‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 2002

- World Health Organization (WHO). Scaling up antiretroviral therapy in resource‐limited settings. http://www.who.int/HIV_AIDS/first.html 2002.

Wright 2003

- Wright CC, Sim J. Intention‐to‐treat approach to data from randomized controlled trials: a sensitivity analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2003;56(9):833‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zheng 1999

- Zheng WY, Pi GH, Xu KQ, Hu CF, Jiang LS, Hu XF, et al. Therapeutic observation of Chinese medicine 'Zai Sheng Dan' in patients with HIV infection. Chinese Journal of Experimental and Clinical Virology 1999;13(3):291‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]