Abstract

The gut microbiome and the immune system co-develop around the time of birth, well after genetic information has been passed from the parents to the offspring. Each of these “organ systems” displays plasticity. The immune system can mount highly specific adaptive responses to newly encountered antigens, and the gut microbiota is affected by changes in the environment. Despite this plasticity, there is a growing appreciation that these organ systems, once established, are remarkably stable. In health, the immune system rapidly mounts responses to infections, and once cleared, resolves inflammatory responses to return to homeostasis. However, a skewed immune system, such as seen in allergy, does not easily return to homeostasis. Allergic responses are often seen to multiple antigens. Likewise, a dysbiotic gut microbiota is seen in multiple diseases. Attempts to reset the gut microbiota as a therapy for disease have met with varied success. Therefore, how these co-developing “organ systems” become established is a central question relevant to our overall health. Recent observations suggest that maternal factors encountered both in utero and after birth can directly or indirectly impact the development of the offspring’s gut microbiome and immune system. Here we discuss how these nongenetic maternal influences can have long term effects on the progeny’s health.

Introduction:

Our intestinal tract is home to trillions of organisms comprising a diverse community termed the gut microbiota (Human Microbiome Project, 2012). The microbes comprising the gut microbiota are not merely passengers, but actively contribute to our health in a symbiotic relationship that has existed on an evolutionary timescale (Moeller et al., 2016). An imbalance in this community, or dysbiosis, increases our risk of multiple diseases including obesity, malnutrition, allergy, inflammatory bowel disease, and diabetes (Cho et al., 2012; Gilbert et al., 2016; Gill et al., 2006; Halfvarson et al., 2017; Jostins et al., 2012; Subramanian et al., 2014; Tsabouri, Priftis, Chaliasos, & Siamopoulou, 2014). The gut microbiota begins assembly at or around the time of birth. Once established, this complex microbial community remains remarkably stable over time (Faith et al., 2013), emphasizing that the proper assemblage of this community is a critical component of our long-term health. The gut microbiota affects and is affected by the intestinal immune system. These organ systems co-develop in early life to establish a stable relationship, which is necessary to prevent inflammation and dysbiosis. There is growing evidence of maternal influences on the assemblage of the gut microbiota and the development of the intestinal immune system. We thus inherit these organ systems in a manner that is at least partially independent of genetics. Alterations in this inheritance by extension can have long-standing impacts on health.

How and when the gut microbiota is acquired

Trillions of microbes reside in our intestine. Their impact on health includes positive and negative effects on metabolic, immune, and endocrine functions. In the healthy state, symbiotic mutualism characterizes our relationship with our gut microbiota. An imbalance in this community, or dysbiosis, increases our risk of multiple diseases including obesity, malnutrition, allergy, inflammatory bowel disease, and diabetes (Gilbert et al., 2016). Once established, this complex microbial community remains remarkably stable over time (Faith et al., 2013), emphasizing that the proper assemblage of this community is a critical component of our long-term health. Thus, how our gut microbiota develops is a fundamental question.

The current understanding is that at the time of birth our gastrointestinal tract is sterile, or contains few microbes, and quickly becomes colonized by microbes encountered in the environment. The functional maturation of the human gut microbiota is relatively conserved between individuals in markedly different environments and concludes around three years of life (Yatsunenko et al., 2012), suggesting that development of this community is not solely dependent upon serendipitous encounters with microbes. While individuals have unique gut microbial communities, their gut microbiota most resembles those of other members of their family (Schloss, Iverson, Petrosino, & Schloss, 2014). This raises the possibility of a parental contribution to the development of the gut microbiota and by extension a non-genetic inherited contribution to our long term health. Indeed, transplant of fetuses into genetically disparate mice revealed the offspring’s microbiota was most similar to the birth mother (Friswell et al., 2010), indicating a strong role for nongenetic factors in the development of the mammalian gut microbiota.

How and when the microbes comprising the gut microbiota are acquired and how this community becomes assembled are not well understood. At the time of delivery, babies become exposed to a plethora of microbes. The microbes encountered are at least partially dependent upon delivery mode, with vaginally delivered babies having microbial communities similar to their mother’s vaginal microbiota and caesarian section delivered babies having microbial communities similar to those of their mother’s skin (Backhed et al., 2015; Dominguez-Bello et al., 2010). While this suggests that delivery mode influences the offspring’s gut microbiota, this has not been universally observed across studies (Bokulich et al., 2016; Chu et al., 2017; Korpela et al., 2018), raising the possibility that other sources of microbes are also important for the developing microbiota. In addition to birth, the developing gut microbiota undergoes substantial changes at the time of the introduction of solid foods (Bokulich et al., 2016; Koenig et al., 2011; Palmer, Bik, DiGiulio, Relman, & Brown, 2007), and accordingly it is not surprising that early life feeding practices have been observed to effect the developing gut microbiota (Azad et al., 2016; Bokulich et al., 2016; Gregory et al., 2016). Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) are abundant in breastmilk where they can serve as a prebiotic supporting the growth of specific beneficial bacterial species (Underwood et al., 2017; Underwood et al., 2014) and in part underlies differences seen in the gut microbiota of breastfed and formula fed children (Bokulich et al., 2016; Gregory et al., 2016).

Breastmilk may contribute to the offspring’s developing gut microbiota beyond providing a nutrient source for microbes. Breastmilk has been found to have its own microbiome (Fernandez et al., 2013; Latuga, Stuebe, & Seed, 2014; Martin, Heilig, Zoetendal, Smidt, & Rodriguez, 2007), raising the possibility that breastmilk could directly seed microbes in the offspring’s gastrointestinal tract. Interestingly, the breastmilk microbiome is comprised of bacteria commonly seen on the skin and within the gastrointestinal tract (Cabrera-Rubio et al., 2012; Gueimonde, Laitinen, Salminen, & Isolauri, 2007; Heikkila & Saris, 2003; Hunt et al., 2011; Thompson, Pickler, Munro, & Shotwell, 1997; Tyson, Edwards, Rosenfeld, & Beer, 1982). Traditionally the bacteria seen in breastmilk were have been thought to be contaminants, but they persist even after collecting breastmilk using aseptic techniques (Thompson et al., 1997). Skin microbes might inoculate the breast during nursing, but how the gut-associated microbes could enter breastmilk is less clear. Enteromammary trafficking of gut bacteria during lactation has been observed in mice, and the peripheral blood and breastmilk from healthy mothers were observed to contain bacteria and bacterial DNA suggesting a gut origin (Perez et al., 2007). Moreover, some of these bacterial DNA signatures were found in the offspring’s feces (Perez et al., 2007), which suggests the seeding of live microbes from the gut microbiota of mothers to their offspring via breastmilk. How enteromammary trafficking of live bacteria occurs, how this process is restricted to a period during lactation, and whether this is a significant and important contributor to the offspring’s developing gut microbiota remain interesting questions whose answers may underlie inherited nongenetic contributions of the gut microbiota to our long-term health.

Whether the healthy human fetus is sterile, and if not, the origins of the microbes in the fetus, are issues of increasing debate(Funkhouser & Bordenstein, 2013; Perez-Munoz, Arrieta, Ramer-Tait, & Walter, 2017; Willyard, 2018). Decades of research using traditional culture based methods have suggested that the fetus develops in a sterile environment. However, modern molecular and sequencing-based techniques challenge this dogma. Not surprisingly, only a few studies have evaluated the presence of live bacteria in the healthy human fetus. Live bacteria have been cultured from the amniotic fluid and cord blood of term pregnancies undergoing cesarean section (Bearfield, Davenport, Sivapathasundaram, & Allaker, 2002; Jimenez et al., 2005). Moreover, studies using culture-independent methods have identified the presence of an array of bacteria associated with the fetus in the absence of preterm labor. These microbes may originate from the mother’s vagina, oral cavity, or gut (Bearfield et al., 2002; S. Rautava, Collado, Salminen, & Isolauri, 2012; Steel et al., 2005). In addition, meconium, the intestinal contents of fetuses and newborns, contains its own microbiota (Gosalbes et al., 2013; Jimenez et al., 2008). However, other studies have found that the bacterial microbiota of term placentas and amniotic fluid resemble that of negative controls (Lauder et al., 2016; Lim, Rodriguez, & Holtz, 2018; Rehbinder et al., 2018). Thus, while there is evidence that the human fetus is not necessarily sterile and is exposed to maternally derived microbes prior to birth, the concept that the healthy human fetus is exposed to microbes prior to rupture of the fetal membranes remains controversial.

Whether this transfer of microbes to the fetus represents normal physiology remains to be proven. If the fetus is exposed in utero, potential sources could be the vaginal, gut, and oral microbiomes. Bacteria are assumed to ascend the vaginal canal to colonize the fetus and fetal membranes. Indeed, bacterial vaginosis has been associated with the presence of bacteria in utero and preterm delivery (Gravett, Hummel, Eschenbach, & Holmes, 1986; Hillier et al., 1995). Bacteria originating from the oral cavity and gut may disseminate and colonize the fetus as bacteremia occurs following oral procedures, teeth brushing, minor manipulations of the lower gastrointestinal tract, and potentially even bowel movements (Hoffman, Kobasa, & Kaye, 1978; Lockhart et al., 2008; Maharaj, Coovadia, & Vayej, 2012; Slavin & Goldwyn, 1979; Tandberg & Reed, 1978). While these sporadic events might be sufficient to expose the fetus to microbes, this alone is insufficient to explain why pregnancy is associated with increased incidence of bacteremia (Perez et al., 2007). Bacteremia during pregnancy might be a physiologic event, potentially related to immune suppression during pregnancy.

From an evolutionary perspective, a regulated mechanism for the maternal-fetal transmission of microbes would ensure the transfer of components crucial to multiple aspects of health. Indeed, the maternal-fetal transfer of microbes is seen across the animal kingdom (Funkhouser & Bordenstein, 2013). A prime example is the obligate endosymbiotic relationship between the pea aphid and the bacteria Buchnera aphidicola. The pea aphid acquired the bacterium hundreds of millions of years ago. Their genomes have co-evolved such that the pea aphid depends upon Buchnera for digestion and Buchnera cannot survive outside of the pea aphid. Buchnera is transferred to the ovaries or developing embryo in the pea aphid to ensure survival of both species (Baumann, 2005; Koga, Meng, Tsuchida, & Fukatsu, 2012). That a similar relationship exists between humans and their gut microbiota and that essential components of the gut microbiota might have a mechanism of enforced vertical transmission in utero are intriguing concepts. However, this is at odds with the ability to generate germ-free humans (Barnes, Fairweather, Reynolds, Tuffrey, & Holliday, 1968) and might suggest that if there is enforced vertical transmission of gut microbes in utero in humans these microbes are transient inhabitants.

A time-dependent nature to the benefit of the gut microbiota on health

While the transfer of microbes in utero remains debatable, the transfer of microbes from mothers to children during breastfeeding and touching to colonize and develop the gut microbiota is well supported. Moreover, evidence is mounting that there is a critical period in the proper assemblage of the gut microbiota for some aspects of health. Perturbations of the microbiota during this developmental window can have long-term consequences. Multiple studies have found that increased hygienic practices increase the risk for immune-mediated diseases such as asthma, allergy, and inflammatory bowel disease (Lopez-Serrano et al., 2010; Strachan, 1989; von Mutius, 2007). These practices are associated with changes in the gut microbiota in individuals from developed countries (Yatsunenko et al., 2012) providing a link between dysbiosis and immune-mediated diseases. Attempts to restore the normal gut microbiota, however, have had varied therapeutic success (Malikowski, Khanna, & Pardi, 2017; Moayyedi et al., 2015; Rossen et al., 2015). The inability of fecal microbial transfer as a therapy could be due to inappropriate donor microbiota, inefficient colonization, or the presence of a critical window of benefit from the normal gut microbiota, which cannot be reset once it has passed. Several observations suggest that this window is in early life. Disruption of the gut microbiota by antibiotic use in children in the first year of life is associated with an increased risk of allergic disorders and inflammatory bowel disease (Han, Forno, Badellino, & Celedon, 2017; Love et al., 2016; Mitre et al., 2018; Pitter et al., 2016; Shaw, Blanchard, & Bernstein, 2010; Yamamoto-Hanada, Yang, Narita, Saito, & Ohya, 2017; Yoshida, Ide, Takeuchi, & Kawakami, 2018). This effect is also seen in animal models of allergy. In mice, antibiotic exposure before, but not after weaning increases allergic outcomes (Russell et al., 2012; Russell et al., 2013). Moreover, colonization of germ-free mice with a normal gut microbiota before but not after weaning offers protection from colitis and allergy (Olszak et al., 2012). This is a strong implication that the effects of antibiotic use on the risk for allergic disorders and inflammatory bowel disease is largely mediated by a time limited changes in the gut microbiota pre-weaning.

A reduction in T regulatory (Treg) cells, which suppresses inflammatory responses, is seen in allergic disorders (Stelmaszczyk-Emmel, Zawadzka-Krajewska, Szypowska, Kulus, & Demkow, 2013) and inflammatory bowel disease (Eastaff-Leung, Mabarrack, Barbour, Cummins, & Barry, 2010) suggesting that the basis for benefit of exposure to the gut microbiota on decreasing the risk of allergic disorders and inflammatory bowel disease may lie in the development of Tregs. Studies in mice identified a population of Tregs that develop in early life in response to gut bacteria. This Treg population is particularly adept at suppressing allergic responses and colitis (Ohnmacht et al., 2015; Sefik et al., 2015). Further supporting this concept, the induction of a Treg cell population during a distinct pre-weaning interval produces antigen-specific tolerance to gut commensal bacteria in mice (Knoop, Gustafsson, et al., 2017). The timing of this interval is proposed to be under maternal control via temporal changes in breastmilk (Al Nabhani & Eberl, 2017; Knoop, Gustafsson, et al., 2017). Thus, maternal breast milk may provide both the microbes and the cues to develop this unique population of Tregs resulting a reduction in the risk of allergic diseases and colitis. Combined with observations that a significant proportion of the microbes constituting our gut microbiota in the first year of life are of maternal origin, this suggests that the gut microbiota and its effects on the developing immune system are an inherited trait affecting our long term health.

Nongenetic inherited influences directly on the immune system

The gut microbiota and intestinal immune system co-develop in early life with each affecting the other. Environmental influences on the gut microbiota in early life will thus affect the immune system. As noted above, some of these effects may be long lived and not easily reset. Beyond this, there is evidence supporting nongenetic influences directly affecting the development of the immune system resulting in life long alterations. Salient examples of this are maternal influences on the development of secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs) and the effects of maternal microchimerism (MMc) on the offspring’s immune system.

Secondary lymphoid organs, which include lymph nodes and Peyer’s Patches, are tissues integral for the initiation of adaptive immune responses whose development is imprinted in utero (Newberry & Lorenz, 2005; Randall, Carragher, & Rangel-Moreno, 2008). New SLOs cannot be formed after the window for SLO development has passed. Thus, the number of SLOs becomes fixed after birth and alterations in SLO development occurring in utero will have lifelong effects. A subset of type 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3) or lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells initiates the development of SLOs (Newberry & Lorenz, 2005; Randall et al., 2008). Retinoids from the maternal diet control the development of LTi cells in the fetus, and by extension control the development of secondary lymphoid tissues in the offspring (van de Pavert et al., 2014). Accordingly, disrupting the signals delivered by retinoids in the maternal diet during gestation results in life long alterations in secondary lymphoid organs and immune deficits (van de Pavert et al., 2014). In addition to this role, retinoids are important for other functions of the immune system, including gut-homing specificity of plasma cells and T cells, the development of T regulatory cells (Tregs), and the prevention of allergic responses (Coombes et al., 2007; Kang, Lim, Andrisani, Broxmeyer, & Kim, 2007; Mora et al., 2006; Sun et al., 2007; Yokota-Nakatsuma et al., 2014). Whether these functions extend to the retinoids derived from the maternal diet and the developing fetus and whether alterations in retinoid signals in utero have durable impacts on these aspects of the offspring’s immune system remain to be explored.

Maternal microchimerism (MMc) is an incompletely understood phenomenon that refers to the presence of cells of maternal origin within the offspring (Adams & Nelson, 2004). The acquisition of maternal cells occurs in utero and during nursing. The transferred cells persist into adulthood (Dutta et al., 2009; Vernochet, Caucheteux, & Kanellopoulos-Langevin, 2007). MMc occurring in utero vs. during nursing seem to have slightly different effects, with the exposure to maternal antigens during nursing being more efficient at inducing tolerance to maternal antigens and facilitating the long term persistence of MMc (Dutta et al., 2009). The cells transferred during MMc are largely of hematopoietic origin and include mature lymphocytes, antigen presenting cells, and stem cells (Dutta & Burlingham, 2010; Nijagal et al., 2011; Stelzer, Thiele, & Solano, 2015). MMc has been observed in a wide variety of organs in the offspring including the gut (Stelzer et al., 2015). The maternal cells are functional in the offspring and have been observed to have various effects on the offspring’s immune system including contributing to protective responses such as antibody production, induction of tolerance to maternal antigens and potentially tolerance to other non-self environmental antigens acquired by antigen presenting cells within the mother, or conversely contributing to autoimmunity in the offspring (Stelzer et al., 2015). The effects of MMc are most apparent in studies of transplants and autoimmunity demonstrating that recipients of maternal tissue had a reduced rate of rejection when compared with recipients of paternal tissue and that autoimmune disorders are associated with higher levels of MMc (Artlett, Miller, Rider, & Childhood Myositis Heterogeneity Collaborative Study, 2001; Joo et al., 2013; van Rood et al., 2002; Vanzyl et al., 2010; Ye, Vives-Pi, & Gillespie, 2014). This suggests that MMc shapes the offspring’s immune system to promote tolerance toward maternal antigens and maternally acquired environmental antigens, but maternal cells also respond to antigens in the offspring to promote autoimmunity.

There are other examples of maternal influences on the developing immune system occurring in utero or through breast milk. Whether these influences have durable effects on the offspring’s immune system, similar to MMc and effects on SLO development, are less clear. Some of these maternal contributions are to protect the fetus and infant during a time when the offspring’s immune system is underdeveloped and unable to properly combat infection, while others help guide the tone of immune responses, especially intestinal immune responses, to promote tolerance toward microbial and dietary antigens. Microbial products from the maternal intestine encountered in utero directly affect innate immunity in the fetus by increasing the population of ILC3s and mononuclear cells and increasing the expression of genes involved in innate defense of the intestine (Gomez de Agüero et al., 2016). The effects of exposure to microbial products from the maternal gut in utero persists for some time after birth, providing the offspring enhanced protection from infection (Gomez de Agüero et al., 2016). Following birth, maternal cues continue to promote the development of the offspring’s immune system. Breastmilk provides nutrition, but also shapes the developing immune system. Breastmilk is rich in immunoglobulins (Ig), including the well-appreciated microbial-specific IgA necessary to prevent pathogen infection in the offspring’s intestinal lumen (Brandtzaeg, 2003). The impact of maternal Ig extends beyond the gut. IgG from breast milk can be transcytosed across the offspring’s intestinal epithelium via the neonatal-Fc-receptor (Roopenian & Akilesh, 2007). Once internalized, maternal Ig containing bound proteins efficiently support the induction of oral tolerance. Complexes of allergens and maternal IgG were superior at inducing allergen-specific Foxp3+CD25+ Tregs in the nursing offspring, compared to oral introduction of allergen alone (Bernard et al., 2014; Mosconi et al., 2010; Nakata et al., 2010; Ohsaki et al., 2018). Additionally, maternal T-independent IgG antibodies limit the exposure of the offspring’s immune system to commensal microbial antigens from the developing gut microbiome, thus preventing the development of inflammatory adaptive responses toward the microbiome and dysbiosis (Koch et al., 2016). Biologically active proteins in breast milk, such as cytokines and growth factors, also direct the offspring’s immune system away from inflammation and toward tolerogenic responses (Järvinen, Suárez-Fariñas, Savilahti, Sampson, & Berin, 2015). Maternal TGF-β can inhibit IL-1β-driven inflammation in the offspring (Samuli Rautava et al., 2011). Maternal IL-6 promotes the development of IgA responses in the offspring (Saito, Maruyama, Kato, Moriyama, & Ichijo, 1991), which is essential for maintaining homeostasis with the microbiome. Breast milk derived epidermal growth factor promotes tolerance by inhibiting TLR4-driven inflammation (Good et al., 2015) and regulates the exposure of offspring to microbial antigens (Knoop, McDonald, et al., 2017). Interestingly, living conditions influence the composition of such cytokines and proteins in the breastmilk. One study reported concentrations of cytokines and growth factors decreased at different rates in women in England, Italy, and Russia (Munblit et al., 2016). Another study found Estonian women had increased IL-10, IFN-g, and SIgA when compared with Swedish women living in more affluent conditions, who had increased IL-13 within colostrum. (Tomičić et al., 2010) These differences were correlated to environmental endotoxin concentrations in Swedish women suggesting decreased microbial exposure in mothers could result in increased IL-13 in breastmilk and promote the development of allergies in offspring. Environmental exposures of mothers during lactation could hence greatly influence the offspring’s immune system, potentially recapitulating the “hygiene hypothesis” whereby increased hygiene and reduced microbial exposure contributes to the development of allergic disorders.

The metabolites found in breastmilk can also influence the offspring’s immune system. As previously discussed, human milk oligosaccharides, the composition of which may be subject to environmental factors and diet (Davis et al., 2017), support the development of the offspring’s microbiome (Marcobal & Sonnenburg, 2012), which in turn drives the development of the immune system (Maynard, Elson, Hatton, & Weaver, 2012). Milk fat globule membrane from lactation contains biologically active fatty acids (Lindquist & Hernell, 2010) that can drive differentiation of intestinal secretory cells and protect against inflammation (Bhinder et al., 2017). The composition of the mother’s dietary fats affects the fatty acid composition of her breastmilk. Diets rich in unsaturated fats might thus be protective, and diets rich in saturated fats may promote inflammation and TLR4 signaling (Caplan et al., 2001; Lu, Jilling, Li, & Caplan, 2007; Robinson & Caplan, 2014). These non-inherited maternal contributions once again show how the mother’s environment and diet can influence the offspring’s immune system via breastmilk.

While it remains to be seen how a maternal deficiency in any of the above contributions may influence the offspring, infants without access to breastmilk clearly fare worse in multiple disease outcomes during early life (Lamberti et al., 2013; Turin & Ochoa, 2014). The World Health Organization Global Breastfeeding Collective current initiative is to promote breastfeeding within an hour of a child’s birth and exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life (Grummer-Strawn et al., 2017; Khan, Vesel, Bahl, & Martines, 2015). Since this is not always possible for multiple reasons, physiological and emotional, use of donor milk through milk banks, have become a popular diet choice compared to infant formula (Chen, 2018; Parra-Llorca et al., 2018). Though the biologically active proteins reviewed above can be destroyed during the pasteurization process (Untalan, Keeney, Palkowetz, Rivera, & Goldman, 2009) (Reeves, Johnson, Vasquez, Maheshwari, & Blanco, 2013), increasingly neonatal intensive care units have begun providing donor milk in an effort to provide complete nutrition and protection to premature infants (Adhisivam et al., 2017). Preterm infants fed donor milk had gut microbiomes that more closely resembled infants fed their mother’s own milk compared with formula fed infants (Parra-Llorca et al., 2018). Additionally, some groups have tested the viability of “spiking” donor milk with infants’ own mothers milk to inoculate the infants with a personalized microbiome (Cacho et al., 2017), a concept similar to a recent push to include probiotics in infant formula (Mugambi, Musekiwa, Lombard, Young, & Blaauw, 2012; S. Rautava et al., 2012) (Aceti et al., 2016) (Villamor-Martínez et al., 2017) (Cavallaro, Villamor-Martínez, Filippi, Mosca, & Villamor, 2017). These interventions showcase the importance of breastfeeding, or in lieu of breastfeeding, a diet reflecting the myriad of components maternally transferred that support the development of the offspring’s immune system and shape gut homeostasis during early life.

Conclusion

The immune system and the gut microbiota develop jointly around the time of birth. Although both display some degree of plasticity, once established these “organ systems” are remarkably stable. There is a growing appreciation of the many influences that our parents, and particularly our mothers, have on the development of the gut microbiota and immune system through events occurring in utero and after birth. Our parents give us much more than genes.

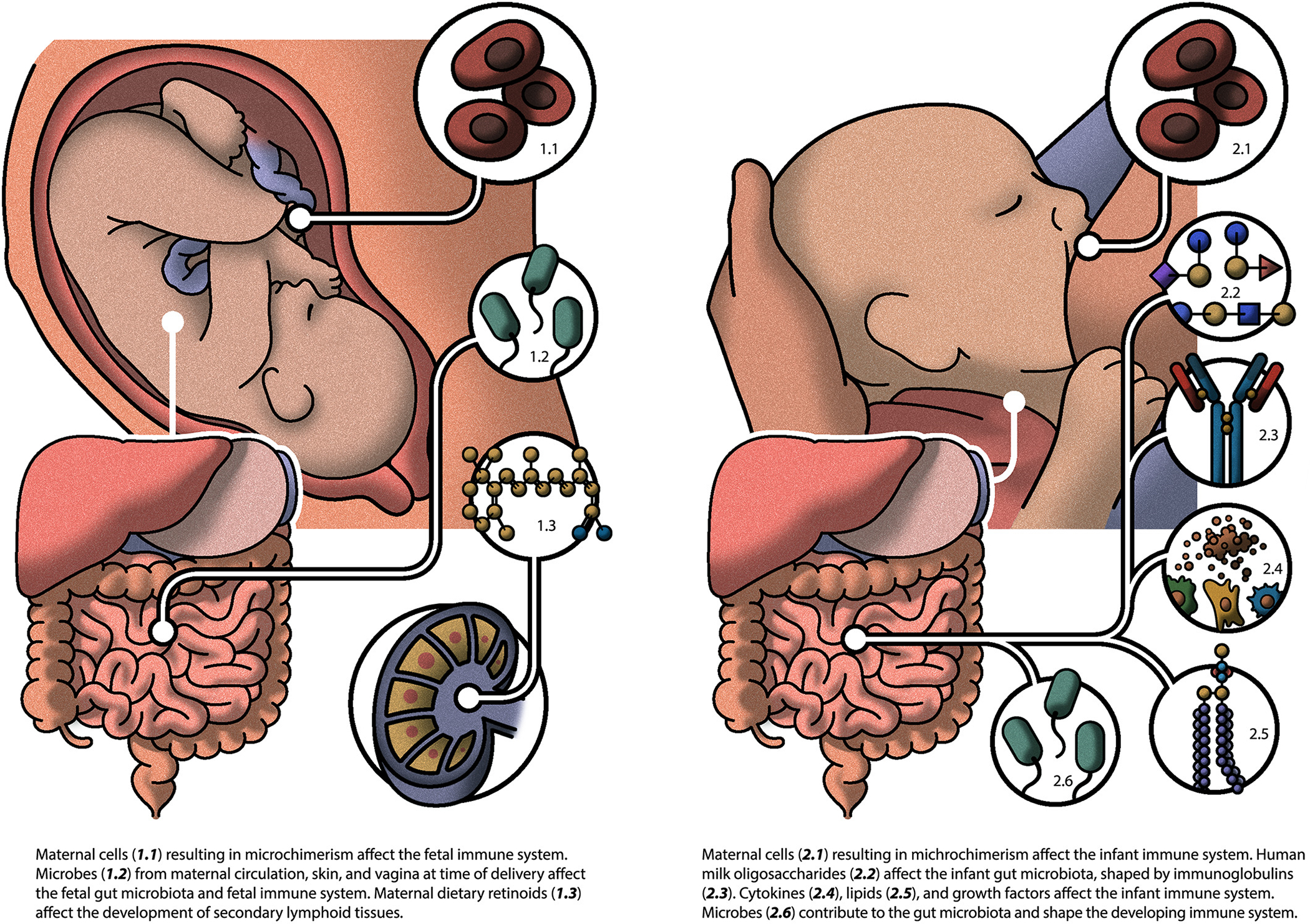

Figure 1.

Inherited influences on the gut microbiome and immune system

References

- Aceti A, Gori D, Barone G, Callegari ML, Fantini MP, Indrio F, … Corvaglia L (2016). Probiotics and Time to Achieve Full Enteral Feeding in Human Milk-Fed and Formula-Fed Preterm Infants: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 8(8), 471. doi: 10.3390/nu8080471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams KM, & Nelson JL (2004). Microchimerism: an investigative frontier in autoimmunity and transplantation. Jama, 291(9), 1127–1131. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhisivam B, Vishnu Bhat B, Banupriya N, Poorna R, Plakkal N, & Palanivel C (2017). Impact of human milk banking on neonatal mortality, necrotizing enterocolitis, and exclusive breastfeeding – experience from a tertiary care teaching hospital, south India. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 1–4. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1395012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Nabhani Z, & Eberl G (2017). GAPs in early life facilitate immune tolerance. Science Immunology, 2(18). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artlett CM, Miller FW, Rider LG, & Childhood Myositis Heterogeneity Collaborative Study G. (2001). Persistent maternally derived peripheral microchimerism is associated with the juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Rheumatology (Oxford, England), 40(11), 1279–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azad MB, Konya T, Persaud RR, Guttman DS, Chari RS, Field CJ, … Investigators CS (2016). Impact of maternal intrapartum antibiotics, method of birth and breastfeeding on gut microbiota during the first year of life: a prospective cohort study. BJOG, 123(6), 983–993. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhed F, Roswall J, Peng Y, Feng Q, Jia H, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, … Wang J (2015). Dynamics and Stabilization of the Human Gut Microbiome during the First Year of Life. Cell Host Microbe, 17(6), 852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes RD, Fairweather DV, Reynolds EO, Tuffrey M, & Holliday J (1968). A technique for the delivery of a germfree child. The Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology of the British Commonwealth, 75(7), 689–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann P (2005). Biology bacteriocyte-associated endosymbionts of plant sap-sucking insects. Annu Rev Microbiol, 59, 155–189. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearfield C, Davenport ES, Sivapathasundaram V, & Allaker RP (2002). Possible association between amniotic fluid micro-organism infection and microflora in the mouth. BJOG, 109(5), 527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard H, Ah-Leung S, Drumare MF, Feraudet-Tarisse C, Verhasselt V, Wal JM, … Adel-Patient K (2014). Peanut allergens are rapidly transferred in human breast milk and can prevent sensitization in mice. Allergy, 69(7), 888–897. doi: 10.1111/all.12411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhinder G, Allaire JM, Garcia C, Lau JT, Chan JM, Ryz NR, … Vallance BA (2017). Milk Fat Globule Membrane Supplementation in Formula Modulates the Neonatal Gut Microbiome and Normalizes Intestinal Development. Scientific Reports, 7, 45274. doi: 10.1038/srep45274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokulich NA, Chung J, Battaglia T, Henderson N, Jay M, Li H, … Blaser MJ (2016). Antibiotics, birth mode, and diet shape microbiome maturation during early life. Sci Transl Med, 8(343), 343ra382. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandtzaeg P (2003). Mucosal immunity: integration between mother and the breast-fed infant. Vaccine, 21(24), 3382–3388. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00338-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Rubio R, Collado MC, Laitinen K, Salminen S, Isolauri E, & Mira A (2012). The human milk microbiome changes over lactation and is shaped by maternal weight and mode of delivery. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 96(3), 544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacho NT, Harrison NA, Parker LA, Padgett KA, Lemas DJ, Marcial GE, … Lorca GL (2017). Personalization of the Microbiota of Donor Human Milk with Mother’s Own Milk. Frontiers in Microbiology, 8, 1470. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan MS, Russell T, Xiao Y, Amer M, Kaup S, & Jilling T (2001). Effect of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid (PUFA) Supplementation on Intestinal Inflammation and Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) in a Neonatal Rat Model. Pediatric research, 49, 647. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200105000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro G, Villamor-Martínez E, Filippi L, Mosca F, & Villamor E (2017). Probiotic supplementation in preterm infants does not affect the risk of retinopathy of prematurity: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scientific Reports, 7, 13014. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13465-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y (2018). Considerations in Donor Human Milk Use in Premature Infants. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Publish Ahead of Print. doi: 10.1097/mpg.0000000000002095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho I, Yamanishi S, Cox L, Methe BA, Zavadil J, Li K, … Blaser MJ (2012). Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity. Nature, 488(7413), 621–626. doi: 10.1038/nature11400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu DM, Ma J, Prince AL, Antony KM, Seferovic MD, & Aagaard KM (2017). Maturation of the infant microbiome community structure and function across multiple body sites and in relation to mode of delivery. Nat Med. doi: 10.1038/nm.4272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y, & Powrie F (2007). A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med, 204(8), 1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JCC, Lewis ZT, Krishnan S, Bernstein RM, Moore SE, Prentice AM, … Zivkovic AM (2017). Growth and Morbidity of Gambian Infants are Influenced by Maternal Milk Oligosaccharides and Infant Gut Microbiota. Scientific Reports, 7, 40466. doi: 10.1038/srep40466 https://www.nature.com/articles/srep40466#supplementary-information [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Fierer N, & Knight R (2010). Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(26), 11971–11975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta P, & Burlingham WJ (2010). Stem cell microchimerism and tolerance to non-inherited maternal antigens. Chimerism, 1(1), 2–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta P, Molitor-Dart M, Bobadilla JL, Roenneburg DA, Yan Z, Torrealba JR, & Burlingham WJ (2009). Microchimerism is strongly correlated with tolerance to noninherited maternal antigens in mice. Blood, 114(17), 3578–3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastaff-Leung N, Mabarrack N, Barbour A, Cummins A, & Barry S (2010). Foxp3+ regulatory T cells, Th17 effector cells, and cytokine environment in inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Clinical Immunology, 30(1), 80–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith JJ, Guruge JL, Charbonneau M, Subramanian S, Seedorf H, Goodman AL, … Gordon JI (2013). The long-term stability of the human gut microbiota. Science (New York, N Y ), 341(6141), 1237439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez L, Langa S, Martin V, Maldonado A, Jimenez E, Martin R, & Rodriguez JM (2013). The human milk microbiota: origin and potential roles in health and disease. Pharmacol Res, 69(1), 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friswell MK, Gika H, Stratford IJ, Theodoridis G, Telfer B, Wilson ID, & McBain AJ (2010). Site and strain-specific variation in gut microbiota profiles and metabolism in experimental mice. PLoS ONE, 5(1), e8584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funkhouser LJ, & Bordenstein SR (2013). Mom knows best: the universality of maternal microbial transmission. PLoS Biol, 11(8), e1001631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JA, Quinn RA, Debelius J, Xu ZZ, Morton J, Garg N, … Knight R (2016). Microbiome-wide association studies link dynamic microbial consortia to disease. Nature, 535(7610), 94–103. doi: 10.1038/nature18850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SR, Pop M, Deboy RT, Eckburg PB, Turnbaugh PJ, Samuel BS, … Nelson KE (2006). Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science, 312(5778), 1355–1359. doi: 10.1126/science.1124234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez de Agüero M, Ganal-Vonarburg SC, Fuhrer T, Rupp S, Uchimura Y, Li H, … Macpherson AJ (2016). The maternal microbiota drives early postnatal innate immune development. Science (New York, N Y ), 351(6279), 1296–1302. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good M, Sodhi CP, Egan CE, Afrazi A, Jia H, Yamaguchi Y, … Hackam DJ (2015). Breast milk protects against the development of necrotizing enterocolitis through inhibition of Toll-like receptor 4 in the intestinal epithelium via activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Mucosal Immunol. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosalbes MJ, Llop S, Valles Y, Moya A, Ballester F, & Francino MP (2013). Meconium microbiota types dominated by lactic acid or enteric bacteria are differentially associated with maternal eczema and respiratory problems in infants. Clin Exp Allergy, 43(2), 198–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravett MG, Hummel D, Eschenbach DA, & Holmes KK (1986). Preterm labor associated with subclinical amniotic fluid infection and with bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol, 67(2), 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory KE, Samuel BS, Houghteling P, Shan G, Ausubel FM, Sadreyev RI, & Walker WA (2016). Influence of maternal breast milk ingestion on acquisition of the intestinal microbiome in preterm infants. Microbiome, 4(1), 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grummer-Strawn LM, Zehner E, Stahlhofer M, Lutter C, Clark D, Sterken E, … Ransom EI (2017). New World Health Organization guidance helps protect breastfeeding as a human right. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13(4), e12491. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueimonde M, Laitinen K, Salminen S, & Isolauri E (2007). Breast milk: a source of bifidobacteria for infant gut development and maturation? Neonatology, 92(1), 64–66. doi: 10.1159/000100088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfvarson J, Brislawn CJ, Lamendella R, Vazquez-Baeza Y, Walters WA, Bramer LM, … Jansson JK (2017). Dynamics of the human gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Microbiol, 2, 17004. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y-Y, Forno E, Badellino HA, & Celedon JC (2017). Antibiotic Use in Early Life, Rural Residence, and Allergic Diseases in Argentinean Children. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology In practice, 5(4), 1112–1118.e1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkila MP, & Saris PEJ (2003). Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus by the commensal bacteria of human milk. J Appl Microbiol, 95(3), 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier SL, Nugent RP, Eschenbach DA, Krohn MA, Gibbs RS, Martin DH, … Rao AV (1995). Association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm delivery of a low-birth-weight infant. The Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. The New England journal of medicine, 333(26), 1737–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman BI, Kobasa W, & Kaye D (1978). Bacteremia after rectal examination. Annals of internal medicine, 88(5), 658–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Microbiome Project C. (2012). Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature, 486(7402), 207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt KM, Foster JA, Forney LJ, Schutte UM, Beck DL, Abdo Z, … McGuire MA (2011). Characterization of the diversity and temporal stability of bacterial communities in human milk. PLoS ONE, 6(6), e21313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Järvinen KM, Suárez-Fariñas M, Savilahti E, Sampson HA, & Berin MC (2015). Immune factors in breast milk related to infant milk allergy are independent of maternal atopy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 135(5), 1390–1393.e1396. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.10.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez E, Fernandez L, Marin ML, Martin R, Odriozola JM, Nueno-Palop C, … Rodriguez JM (2005). Isolation of commensal bacteria from umbilical cord blood of healthy neonates born by cesarean section. Curr Microbiol, 51(4), 270–274. doi: 10.1007/s00284-005-0020-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez E, Marin ML, Martin R, Odriozola JM, Olivares M, Xaus J, … Rodriguez JM (2008). Is meconium from healthy newborns actually sterile? Res Microbiol, 159(3), 187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2007.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo SY, Song EY, Shin Y, Ha J, Kim SJ, & Park MH (2013). Beneficial effects of pretransplantation microchimerism on rejection-free survival in HLA-haploidentical family donor renal transplantation. Transplantation, 95(11), 1375–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, … Whittaker P (2012). Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature, 491(7422), 119–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SG, Lim HW, Andrisani OM, Broxmeyer HE, & Kim CH (2007). Vitamin A metabolites induce gut-homing FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol, 179(6), 3724–3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan J, Vesel L, Bahl R, & Martines JC (2015). Timing of Breastfeeding Initiation and Exclusivity of Breastfeeding During the First Month of Life: Effects on Neonatal Mortality and Morbidity—A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19(3), 468–479. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1526-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoop KA, Gustafsson JK, McDonald KG, Kulkarni DH, Coughlin PE, McCrate S, … Newberry RD (2017). Microbial antigen encounter during a preweaning interval is critical for tolerance to gut bacteria. Sci Immunol, 2(18). doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aao1314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoop KA, McDonald K, Gustafsson J, Hogan SP, Elson C, Tarr PI, & Newberry RD (2017). Microbial and Maternal Factors Control the Development of ROR gamma t plus Regulatory T Cells Promoting Durable Tolerance and Preventing Allergy. Journal of Immunology, 198(1). [Google Scholar]

- Koch Meghan A., Reiner Gabrielle L., Lugo Kyler A., Kreuk Lieselotte S. M., Stanbery Alison G., Ansaldo E, … Barton Gregory M. (2016). Maternal IgG and IgA Antibodies Dampen Mucosal T Helper Cell Responses in Early Life. Cell, 165(4), 827–841. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig JE, Spor A, Scalfone N, Fricker AD, Stombaugh J, Knight R, … Ley RE (2011). Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 108 Suppl 1, 4578–4585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000081107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga R, Meng XY, Tsuchida T, & Fukatsu T (2012). Cellular mechanism for selective vertical transmission of an obligate insect symbiont at the bacteriocyte-embryo interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 109(20), E1230–1237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119212109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpela K, Costea P, Coelho LP, Kandels-Lewis S, Willemsen G, Boomsma DI, … Bork P (2018). Selective maternal seeding and environment shape the human gut microbiome. Genome Res, 28(4), 561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberti LM, Zakarija-Grković I, Fischer Walker CL, Theodoratou E, Nair H, Campbell H, & Black RE (2013). Breastfeeding for reducing the risk of pneumonia morbidity and mortality in children under two: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 13(Suppl 3), S18–S18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-S3-S18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latuga MS, Stuebe A, & Seed PC (2014). A review of the source and function of microbiota in breast milk. Semin Reprod Med, 32(1), 68–73. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1361824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauder AP, Roche AM, Sherrill-Mix S, Bailey A, Laughlin AL, Bittinger K, … Bushman FD (2016). Comparison of placenta samples with contamination controls does not provide evidence for a distinct placenta microbiota. Microbiome, 4(1), 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim ES, Rodriguez C, & Holtz LR (2018). Amniotic fluid from healthy term pregnancies does not harbor a detectable microbial community. Microbiome, 6(1), 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S, & Hernell O (2010). Lipid digestion and absorption in early life: an update. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 13(3), 314–320. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328337bbf0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart PB, Brennan MT, Sasser HC, Fox PC, Paster BJ, & Bahrani-Mougeot FK (2008). Bacteremia associated with toothbrushing and dental extraction. Circulation, 117(24), 3118–3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Serrano P, Perez-Calle JL, Perez-Fernandez MT, Fernandez-Font JM, Boixeda de Miguel D, & Fernandez-Rodriguez CM (2010). Environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel diseases. Investigating the hygiene hypothesis: a Spanish case-control study. Scand J Gastroenterol, 45(12), 1464–1471. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.510575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love BL, Mann JR, Hardin JW, Lu ZK, Cox C, & Amrol DJ (2016). Antibiotic prescription and food allergy in young children. Allergy, asthma, and clinical immunology : official journal of the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 12, 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Jilling T, Li DAN, & Caplan MS (2007). Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Supplementation Alters Proinflammatory Gene Expression and Reduces the Incidence of Necrotizing Enterocolitis in a Neonatal Rat Model. Pediatric research, 61(4), 427–432. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e3180332ca5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharaj B, Coovadia Y, & Vayej AC (2012). An investigation of the frequency of bacteraemia following dental extraction, tooth brushing and chewing. Cardiovasc J Afr, 23(6), 340–344. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2012-016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malikowski T, Khanna S, & Pardi DS (2017). Fecal microbiota transplantation for gastrointestinal disorders. Curr Opin Gastroenterol, 33(1), 8–13. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcobal A, & Sonnenburg JL (2012). Human milk oligosaccharide consumption by intestinal microbiota. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 18(0 4), 12–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03863.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Heilig GH, Zoetendal EG, Smidt H, & Rodriguez JM (2007). Diversity of the Lactobacillus group in breast milk and vagina of healthy women and potential role in the colonization of the infant gut. J Appl Microbiol, 103(6), 2638–2644. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03497.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard CL, Elson CO, Hatton RD, & Weaver CT (2012). Reciprocal Interactions of the Intestinal Microbiota and Immune System. Nature, 489(7415), 231–241. doi: 10.1038/nature11551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitre E, Susi A, Kropp LE, Schwartz DJ, Gorman GH, & Nylund CM (2018). Association Between Use of Acid-Suppressive Medications and Antibiotics During Infancy and Allergic Diseases in Early Childhood. JAMA pediatrics, 172(6), e180315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moayyedi P, Surette MG, Kim PT, Libertucci J, Wolfe M, Onischi C, … Lee CH (2015). Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Induces Remission in Patients With Active Ulcerative Colitis in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology, 149(1), 102–109 e106. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller AH, Caro-Quintero A, Mjungu D, Georgiev AV, Lonsdorf EV, Muller MN, … Ochman H (2016). Cospeciation of gut microbiota with hominids. Science (New York, N Y ), 353(6297), 380–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora JR, Iwata M, Eksteen B, Song SY, Junt T, Senman B, … von Andrian UH (2006). Generation of Gut-Homing IgA-Secreting B Cells by Intestinal Dendritic Cells. Science, 314(5802), 1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1132742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosconi E, Rekima A, Seitz-Polski B, Kanda A, Fleury S, Tissandie E, … Verhasselt V (2010). Breast milk immune complexes are potent inducers of oral tolerance in neonates and prevent asthma development. Mucosal Immunol, 3(5), 461–474. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugambi MN, Musekiwa A, Lombard M, Young T, & Blaauw R (2012). Probiotics, prebiotics infant formula use in preterm or low birth weight infants: a systematic review. Nutrition Journal, 11, 58–58. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-11-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munblit D, Treneva M, Peroni DG, Colicino S, Chow L, Dissanayeke S, … Warner JO (2016). Colostrum and Mature Human Milk of Women from London, Moscow, and Verona: Determinants of Immune Composition. Nutrients, 8(11), 695. doi: 10.3390/nu8110695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata K, Kobayashi K, Ishikawa Y, Yamamoto M, Funada Y, Kotani Y, … Nishimura Y (2010). The transfer of maternal antigen-specific IgG regulates the development of allergic airway inflammation early in life in an FcRn-dependent manner. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 395(2), 238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newberry RD, & Lorenz RG (2005). Organizing a mucosal defense. Immunological reviews, 206, 6–21. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00282.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijagal A, Wegorzewska M, Jarvis E, Le T, Tang Q, & MacKenzie TC (2011). Maternal T cells limit engraftment after in utero hematopoietic cell transplantation in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation, 121(2), 582–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnmacht C, Park JH, Cording S, Wing JB, Atarashi K, Obata Y, … Eberl G (2015). The microbiota regulates type 2 immunity through RORgammat+ T cells. Science. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsaki A, Venturelli N, Buccigrosso TM, Osganian SK, Lee J, Blumberg RS, & Oyoshi MK (2018). Maternal IgG immune complexes induce food allergen–specific tolerance in offspring. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 215(1), 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszak T, An D, Zeissig S, Vera MP, Richter J, Franke A, … Blumberg RS (2012). Microbial exposure during early life has persistent effects on natural killer T cell function. Science, 336(6080), 489–493. doi: 10.1126/science.1219328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer C, Bik EM, DiGiulio DB, Relman DA, & Brown PO (2007). Development of the human infant intestinal microbiota. PLoS biology, 5(7), e177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Llorca A, Gormaz M, Alcántara C, Cernada M, Nuñez-Ramiro A, Vento M, & Collado MC (2018). Preterm Gut Microbiome Depending on Feeding Type: Significance of Donor Human Milk. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9, 1376. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez PF, Dore J, Leclerc M, Levenez F, Benyacoub J, Serrant P, … Donnet-Hughes A (2007). Bacterial imprinting of the neonatal immune system: lessons from maternal cells? Pediatrics, 119(3), e724–732. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Munoz ME, Arrieta M-C, Ramer-Tait AE, & Walter J (2017). A critical assessment of the “sterile womb” and “in utero colonization” hypotheses: implications for research on the pioneer infant microbiome. Microbiome, 5(1), 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitter G, Ludvigsson JF, Romor P, Zanier L, Zanotti R, Simonato L, & Canova C (2016). Antibiotic exposure in the first year of life and later treated asthma, a population based birth cohort study of 143,000 children. European journal of epidemiology, 31(1), 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall TD, Carragher DM, & Rangel-Moreno J (2008). Development of secondary lymphoid organs. Annu Rev Immunol, 26, 627–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautava S, Collado MC, Salminen S, & Isolauri E (2012). Probiotics modulate host-microbe interaction in the placenta and fetal gut: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neonatology, 102(3), 178–184. doi: 10.1159/000339182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautava S, Nanthakumar NN, Dubert-Ferrandon A, Lu L, Rautava J, & Walker WA (2011). Breast Milk-Transforming Growth Factor-β(2) Specifically Attenuates IL-1β-Induced Inflammatory Responses in the Immature Human Intestine via an SMAD6- and ERK-Dependent Mechanism. Neonatology, 99(3), 192–201. doi: 10.1159/000314109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves AA, Johnson MC, Vasquez MM, Maheshwari A, & Blanco CL (2013). TGF-β2, a Protective Intestinal Cytokine, Is Abundant in Maternal Human Milk and Human-Derived Fortifiers but Not in Donor Human Milk. Breastfeeding Medicine, 8(6), 496–502. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2013.0017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehbinder EM, Lodrup Carlsen KC, Staff AC, Angell IL, Landro L, Hilde K, … Rudi K (2018). Is amniotic fluid of women with uncomplicated term pregnancies free of bacteria? Am J Obstet Gynecol, 219(3), 289.e281–289.e212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DT, & Caplan MS (2014). Linking fat intake, the intestinal microbiome, and necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants. Pediatric research, 77, 121. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roopenian DC, & Akilesh S (2007). FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age. Nature Reviews Immunology, 7, 715. doi: 10.1038/nri2155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossen NG, Fuentes S, van der Spek MJ, Tijssen JG, Hartman JH, Duflou A, … Ponsioen CY (2015). Findings From a Randomized Controlled Trial of Fecal Transplantation for Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology, 149(1), 110–118 e114. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.03.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell SL, Gold MJ, Hartmann M, Willing BP, Thorson L, Wlodarska M, … Finlay BB (2012). Early life antibiotic-driven changes in microbiota enhance susceptibility to allergic asthma. EMBO Rep, 13(5), 440–447. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell SL, Gold MJ, Willing BP, Thorson L, McNagny KM, & Finlay BB (2013). Perinatal antibiotic treatment affects murine microbiota, immune responses and allergic asthma. Gut Microbes, 4(2), 158–164. doi: 10.4161/gmic.23567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S, Maruyama M, Kato Y, Moriyama I, & Ichijo M (1991). Detection of IL-6 in human milk and its involvement in IgA production. Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 20(3), 267–276. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(91)90051-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schloss PD, Iverson KD, Petrosino JF, & Schloss SJ (2014). The dynamics of a family’s gut microbiota reveal variations on a theme. Microbiome, 2, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sefik E, Geva-Zatorsky N, Oh S, Konnikova L, Zemmour D, McGuire AM, … Benoist C (2015). Individual intestinal symbionts induce a distinct population of RORgamma+ regulatory T cells. Science, 349(6251), 993–997. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa9420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw SY, Blanchard JF, & Bernstein CN (2010). Association between the use of antibiotics in the first year of life and pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol, 105(12), 2687–2692. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavin S, & Goldwyn RM (1979). Is there postdefecation bacteremia? Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill : 1960), 114(8), 937–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel JH, Malatos S, Kennea N, Edwards AD, Miles L, Duggan P, … Sullivan MHF (2005). Bacteria and inflammatory cells in fetal membranes do not always cause preterm labor. Pediatr Res, 57(3), 404–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelmaszczyk-Emmel A, Zawadzka-Krajewska A, Szypowska A, Kulus M, & Demkow U (2013). Frequency and activation of CD4+CD25 FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in peripheral blood from children with atopic allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol, 162(1), 16–24. doi: 10.1159/000350769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelzer IA, Thiele K, & Solano ME (2015). Maternal microchimerism: lessons learned from murine models. Journal of reproductive immunology, 108, 12–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strachan DP (1989). Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ, 299(6710), 1259–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S, Huq S, Yatsunenko T, Haque R, Mahfuz M, Alam MA, … Gordon JI (2014). Persistent gut microbiota immaturity in malnourished Bangladeshi children. Nature, 510(7505), 417–421. doi: 10.1038/nature13421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun CM, Hall JA, Blank RB, Bouladoux N, Oukka M, Mora JR, & Belkaid Y (2007). Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 T reg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med, 204(8), 1775–1785. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandberg D, & Reed WP (1978). Blood cultures following rectal examination. Jama, 239(17), 1789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson N, Pickler RH, Munro C, & Shotwell J (1997). Contamination in expressed breast milk following breast cleansing. Journal of human lactation : official journal of International Lactation Consultant Association, 13(2), 127–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomičić S, Johansson G, Voor T, Björkstén B, Böttcher MF, & Jenmalm MC (2010). Breast Milk Cytokine and IgA Composition Differ in Estonian and Swedish Mothers—Relationship to Microbial Pressure and Infant Allergy. Pediatric research, 68, 330. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181ee049d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsabouri S, Priftis KN, Chaliasos N, & Siamopoulou A (2014). Modulation of gut microbiota downregulates the development of food allergy in infancy. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr), 42(1), 69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2013.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turin CG, & Ochoa TJ (2014). The Role of Maternal Breast Milk in Preventing Infantile Diarrhea in the Developing World. Current tropical medicine reports, 1(2), 97–105. doi: 10.1007/s40475-014-0015-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson JE, Edwards WH, Rosenfeld AM, & Beer AE (1982). Collection methods and contamination of bank milk. Archives of disease in childhood, 57(5), 396–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood MA, Davis JCC, Kalanetra KM, Gehlot S, Patole S, Tancredi DJ, … Simmer K (2017). Digestion of Human Milk Oligosaccharides by Bifidobacterium breve in the Premature Infant. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 65(4), 449–455. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood MA, Kalanetra KM, Bokulich NA, Mirmiran M, Barile D, Tancredi DJ, … Mills DA (2014). Prebiotic oligosaccharides in premature infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr, 58(3), 352–360. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untalan PB, Keeney SE, Palkowetz KH, Rivera A, & Goldman AS (2009). Heat Susceptibility of Interleukin-10 and Other Cytokines in Donor Human Milk. Breastfeeding Medicine, 4(3), 137–144. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2008.0145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Pavert SA, Ferreira M, Domingues RG, Ribeiro H, Molenaar R, Moreira-Santos L, … Veiga-Fernandes H (2014). Maternal retinoids control type 3 innate lymphoid cells and set the offspring immunity. Nature, 508(7494), 123–127. doi: 10.1038/nature13158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rood JJ, Loberiza FR Jr., Zhang M-J, Oudshoorn M, Claas F, Cairo MS, … Horowitz MH (2002). Effect of tolerance to noninherited maternal antigens on the occurrence of graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation from a parent or an HLA-haploidentical sibling. Blood, 99(5), 1572–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanzyl B, Planas R, Ye Y, Foulis A, de Krijger RR, Vives-Pi M, & Gillespie KM (2010). Why are levels of maternal microchimerism higher in type 1 diabetes pancreas? Chimerism, 1(2), 45–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernochet C, Caucheteux SM, & Kanellopoulos-Langevin C (2007). Bi-directional cell trafficking between mother and fetus in mouse placenta. Placenta, 28(7), 639–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villamor-Martínez E, Pierro M, Cavallaro G, Mosca F, Kramer B, & Villamor E (2017). Probiotic Supplementation in Preterm Infants Does Not Affect the Risk of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients, 9(11), 1197. doi: 10.3390/nu9111197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Mutius E (2007). Allergies, infections and the hygiene hypothesis--the epidemiological evidence. Immunobiology, 212(6), 433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willyard C (2018). Could baby’s first bacteria take root before birth? Nature, 553(7688), 264–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto-Hanada K, Yang L, Narita M, Saito H, & Ohya Y (2017). Influence of antibiotic use in early childhood on asthma and allergic diseases at age 5. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology, 119(1), 54–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, … Gordon JI (2012). Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature, 486(7402), 222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature11053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, Vives-Pi M, & Gillespie KM (2014). Maternal microchimerism: increased in the insulin positive compartment of type 1 diabetes pancreas but not in infiltrating immune cells or replicating islet cells. PLoS ONE, 9(1), e86985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota-Nakatsuma A, Takeuchi H, Ohoka Y, Kato C, Song SY, Hoshino T, … Iwata M (2014). Retinoic acid prevents mesenteric lymph node dendritic cells from inducing IL-13-producing inflammatory Th2 cells. Mucosal Immunol, 7(4), 786–801. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Ide K, Takeuchi M, & Kawakami K (2018). Prenatal and early-life antibiotic use and risk of childhood asthma: A retrospective cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol, 29(5), 490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]