Abstract

Disease course in multiple sclerosis is notably heterogeneous, and few prognostic indicators have been consistently associated with multiple sclerosis severity. In the general population, socioeconomic disparity is associated with multimorbidity and may contribute to worse disease outcomes in multiple sclerosis.

Herein, we assessed whether indicators of socioeconomic status are associated with disease progression in patients with multiple sclerosis using highly sensitive imaging tools such as optical coherence tomography, and determined whether differential multiple sclerosis management or comorbidity mediate any observed socioeconomic status-associated effects. We included 789 participants with longitudinal optical coherence tomography and low contrast letter acuity (at 1.25 and 2.5%) in whom neighbourhood- (derived via nine-digit postal codes) and participant-level socioeconomic status indicators were available ≤10 years of multiple sclerosis symptom onset. Sensitivity analyses included participants with socioeconomic status indicators available ≤3years of symptom onset (n = 552). Neighbourhood-level indicators included state and national area deprivation indices, median household income and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Socioeconomic Status Index. Participant-level indicators included education level. Biannual optical coherence tomography scans were segmented to quantify thickness of the composite macular ganglion cell+inner plexiform (GCIPL) layer. We assessed the association between socioeconomic status indicators and GCIPL atrophy or low contrast letter acuity loss using mixed models adjusting for demographic (including race and ethnicity) and disease-related characteristics. We also assessed socioeconomic status indicators in relation to multiple sclerosis therapy changes and comorbidity risk using survival analysis.

More disadvantaged neighbourhood-level and patient-level socioeconomic status indicators were associated with faster retinal atrophy. Differences in rate of GCIPL atrophy for individuals in the top quartile (most disadvantaged) relative to the bottom quartile (least) for state area deprivation indices were −0.12 µm/year faster [95% confidence interval (CI): −0.19, −0.04; P = 0.003], for national area deprivation indices were −0.08 µm/year faster (95% CI: −0.15, −0.005; P = 0.02), for household income were −0.11 µm/year faster (95% CI: −0.19, −0.03; P = 0.008), for AHRQ Socioeconomic Status Index were −0.12 µm/year faster (95% CI: −0.19, −0.04) and for education level were −0.17 µm/year faster (95% CI: −0.26, −0.08; P = 0.0002). Similar associations were observed for socioeconomic status indicators and low contrast letter acuity loss. Lower socioeconomic status was associated with higher risk of incident comorbidity during follow-up. Low socioeconomic status individuals had faster rates of therapy escalation, suggesting the association between socioeconomic status and GCIPL atrophy may not be explained by differential contemporaneous multiple sclerosis therapy management.

In conclusion, socioeconomic disparity is associated with faster retinal neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. As low socioeconomic status was associated with a higher risk of incident comorbidities that may adversely affect multiple sclerosis outcomes, comorbidity prevention may mitigate some of the unfavourable socioeconomic status-associated consequences.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis, socioeconomic status (SES), optical coherence tomography (OCT)

See Green (doi:10.1093/brain/awab424) for a scientific commentary on this article.

Vasileiou et al. report that socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals with multiple sclerosis have an increased risk of retinal neurodegeneration and, subsequently, faster subclinical disease progression.

See Green (doi:10.1093/brain/awab424) for a scientific commentary on this article.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis is a chronic autoimmune neurodegenerative disease of the CNS affecting nearly 1 million individuals in the USA.1,2 Multiple sclerosis is complex, and the disease course is highly heterogeneous. Some individuals rapidly progress to a disabled state whereas others experience only mild symptoms.3 A number of previous studies have identified comorbidity and non-white race as potential contributors to the observed variability in disease evolution.4-8 Broader underlying societal features including socioeconomic status (SES) may be intricately related to some of the observed prognostic indicators and could additionally play a role in multiple sclerosis course.

SES is a combination of financial, educational and occupational influences, and evidence implicates an interaction of SES with individual mental and physical health.9–11 Other studies suggest low SES is related to a more proinflammatory phenotype, in which disadvantaged individuals are more susceptible to aberrant inflammatory responses.12 In multiple sclerosis, few studies have examined the association of SES with disease course. A previous study of multiple sclerosis patients in the UK and Canada found that lower SES was associated with a higher risk of disability progression.13 However, limited longitudinal studies have (i) evaluated contributions of SES to emerging, potentially more sensitive biomarkers of disease progression like optical coherence tomography (OCT)-based biomarkers of retinal neurodegeneration; or (ii) explored associations between SES and multiple sclerosis outcomes in more racially and socially diverse cohorts, where societal disadvantage may have a more prominent effect on individual health and disease prognosis. Last, few studies have also considered whether any association between SES and multiple sclerosis outcomes is mediated by changes in body weight or is related to differences in risk for comorbidity or changes in disease management, as previous research links each of these characteristics with differences in outcomes.5,14–16

In the following study, we assess the association between SES and the rate of retinal neurodegeneration, as a robust indicator of disease progression, as well as evaluate how race, comorbidity risk and contemporaneous multiple sclerosis disease modifying therapy timing could potentially play a role.

Materials and methods

Standard protocol approvals, registrations and patient consents

Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the study protocol, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before study enrolment.

Study population and clinical data

Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (according to the 2010 revised McDonald criteria) were followed at the JH Multiple Sclerosis Center as part of an ongoing prospective retinal imaging cohort study in which roughly biannual OCT scans were obtained.17 Individuals with other known neurological or ophthalmological disorders, glaucoma or refractive errors exceeding ±6 dioptres were excluded. Retinal imaging was performed roughly biannually using spectral domain Cirrus HD-OCT (model 5000, software v.11.5; Carl Zeiss Meditec) as described in detail previously.18,19 Briefly, peripapillary and macular retinal layer thicknesses were obtained with the Optic Disc Cube 200 × 200 protocol and Macular Cube 512 × 128 protocol, respectively. Segmentation of the ganglion and inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) was performed using an automated segmentation algorithm that calculates the average GCIPL thickness within an annulus, centred at the fovea, with an internal diameter of 1 mm and an external diameter of 5 mm.3,20 All scans underwent rigorous quality control in accordance with the OSCAR-IB criteria; scans with signal strength below 7/10, with artefact or with segmentation errors were excluded from the study.21 OCT methods and results are reported in accordance with the consensus Advised Protocol for OCT Study Terminology and Elements (APOSTEL) recommendations.22 We selected rates of changes in the composite GCIPL layer as the primary outcome because in people with multiple sclerosis, the GCIPL is less vulnerable to swelling associated with inflammation of the optic nerve (unlike the retinal nerve fibre layer) and GCIPL degeneration also correlates more strongly with grey matter loss and disability in multiple sclerosis.19 Secondary analyses also considered change in the peripapillary retinal fibre layer thickness (pRNFL). Standardized visual function testing was performed with retro-illuminated eye charts in a darkened room before OCT examination approximately biannually. To assess visual acuity at 2.5 and 1.25% contrast, we used low contrast letter acuity (LCLA) Sloan letter charts; the number of letters correctly identified were recorded, and participants also used their habitual glasses or contact lenses. Other multiple sclerosis characteristics including disease duration, subtype, relapse incidence and disease modifying therapy (DMT) were also recorded at each study visit. Clinical and lifestyle information, including smoking status, serum vitamin D levels and body mass index (BMI) as kg/m2 were abstracted from the electronic medical record. Likewise, diagnosis of comorbidity [diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, migraine, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), depression, anxiety, coronary artery disease, obstructive sleep apnoea or osteoporosis] were also abstracted from the electronic medical record using diagnostic codes.

Indicators of socioeconomic status

SES was estimated using a combination of both neighbourhood and patient-level indicators. We linked patient home nine-digit postal code (available for each encounter) with measures of neighbourhood SES at the census block group level. Measures included median household income, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) SES Index, and the State and National Area Deprivation Index (ADI) as estimated from 5-year American Community Surveys. The AHRQ SES Index is a composite measure of neighbourhood SES calculated that incorporates median household income, households below federal poverty line, employment, education, property values and household crowding. AHRQ SES indices range from 0 (most disadvantaged) to 100 (least disadvantaged).23,24 The ADI is another composite neighbourhood SES measure that incorporates 17 different measures of SES, some of which are distinct from the AHRQ SES Index (e.g. income disparity, access to telephones, vehicles or plumbing, occupational composition, single-parent household rate, divorce rate, English language proficiency, among others). National ADI values range from 1 (least disadvantaged) to 100 (most disadvantaged) and state ADI values range from 1 (least disadvantaged) to 10 (most disadvantaged).25,26 Multiple composite measures of neighbourhood-level SES were selected as while these measures are correlated, each is composed of different indicators and could be measuring aspects of SES that may be differentially associated with health outcomes. SES indicators at the participant level included years of education. Absolute values of correlations between various neighbourhood-level and participant-level SES indices range from 0.23 to 0.88.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible participants included patients in whom neighbourhood-level SES indices (derived using nine-digit postal codes) were available within 10 years of multiple sclerosis symptom onset and who had longitudinal OCT assessments (n = 810). We excluded participants with optic neuritis within 6 months of initial OCT scan or censored individuals who experienced optic neuritis during follow-up (n = 15), as inflammatory pathology associated with optic neuritis may contribute to initial peripapillary swelling and subsequent accelerated pRNFL and GCIPL loss, unrelated to the progressive retinal layer atrophy that portraits subclinical disease activity and ultimately, disease outcome, which is of interest in this study.19,27

Statistical analysis

Initial analyses assessed differences in participant demographic and clinical characteristics according to quartile of national ADI. Longitudinal analyses assessed the association between neighbourhood and individual SES indicators and GCIPL rate of change using mixed effects models. Primary analyses included participants with neighbourhood-level SES indicator (e.g. nine-digit postal code) within 10 years of multiple sclerosis symptom onset. To minimize the risk of reverse causation, we performed additional analyses in which we further restricted eligible participants to those with neighbourhood-level SES indicators within 3 years from multiple sclerosis symptom onset to ensure that early multiple sclerosis-related disability was not adversely affecting SES. We modelled all SES indicators using quartiles, linear terms and restricted cubic splines (to ensure linear models provided adequate fit). All models were adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, disease duration, disease subtype, history of optic neuritis, number of DMTs before first OCT assessment, baseline BMI, any comorbidity at baseline, highest DMT class before study, smoking status and the interval between SES assessment and initial OCT. We also adjusted models for whether or not a participant resident lived in a state geographically close to the JHU Multiple Sclerosis Center (e.g. Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Washington D.C. or West Virginia) to account for possible differences in financial resources for participants who travel to longer distances to the JHU Multiple Sclerosis Center. Additional analyses considered smoking status, vitamin D levels and DMT exposure as time-varying covariates. Further, as Black/African Americans may have faster rates of GCIPL decline, we evaluated potential effect modification by race.7,8 Initial analyses did not exclude individuals with prevalent hypertension, as this exclusion may differentially exclude individuals with low SES. However, because prevalent diabetes or hypertension may influence OCT assessments, we performed additional sensitivity analyses excluding these individuals with baseline diabetes or hypertension (n = 67) as well as analyses excluding those developing diabetes or hypertension during follow-up (n = 74). Similar multivariable-adjusted models and sensitivity analyses assessed the association between SES indicators and rate of pRNFL atrophy as well as LCLA loss.

Next, we assessed whether the observed association between SES and GCIPL atrophy was potentially related to differential contemporaneous multiple sclerosis therapy strategies (e.g. low-SES individuals may have fewer opportunities to change DMTs over follow-up). To do so, we evaluated the association between SES and rate of therapy escalation (defined as switching from a lower potency DMT to a higher potency DMT) using an Andersen Gill model for recurrent events to allow for multiple therapy changes. We considered injectable therapies (glatiramer acetate, interferon beta) as low potency DMTs, oral therapies (dimethyl fumarate, teriflunomide or fingolimod) as moderate efficacy DMTs, and monocloncal therapies (rituximab, natalizumab, ocrelizumab, daclizumab, alemtuzumab) as higher potency DMTs. We considered similar models for time to any therapy change (regardless of class) or time to therapy de-escalation (defined as switching from a higher potency DMT to a lower potency DMT) using similar Andersen Gill models. Models adjusted for a similar set of covariates as for GCIPL atrophy analyses.

Last, given the well-known relationship between socioeconomic disparity and chronic disease risk in the general population and emerging evidence suggesting comorbidity increases risk of adverse multiple sclerosis outcomes, we then assessed whether the observed association between SES and GCIPL atrophy was consistent with a differential risk of comorbidity among those with low SES, as an example of a potential contributor for the observed SES effect on multiple sclerosis outcomes.11 To do so, we assessed the association between SES indicators and incident comorbidity using Cox proportional hazards models (excluding those with prevalent comorbidity at study baseline). We considered a composite measure of comorbidity as developing any of the following during follow-up: hypertension, depression, dyslipidaemia, COPD, diabetes, migraine, coronary artery disease, obstructive sleep apnoea or osteoporosis. We also considered individual comorbidities in which ≥50 incident events occurred over follow-up. Next, formal causal mediation analyses assessed whether the association between SES indicators and GCIPL atrophy was mediated through change in BMI, as BMI is associated with GCIPL thinning and has strong links to comorbidity risk.5,28,29 For this analysis, we matched BMI values measured within 90 days of an OCT scan and updated values throughout follow-up. We estimated 95% confidence intervals (CI) for indirect and direct effects using bootstrapping. Sensitivity analyses also modelled SES indices as predictors for longitudinal change in BMI using mixed effects models. We adjusted for a similar set of covariates for both incident comorbidity and BMI analyses as in models for GCIPL atrophy and therapy changes (with the exception of baseline BMI). All statistical analyses were conducted using R programming (v.3.6.1). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Data availability

De-identified data may be available on request for investigators whose proposed use has been approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of institution of the principal investigator.

Results

Study population

For primary analyses, we included 789 participants who were followed for a median of 4.5 years [interquartile range (IQR): 2.2, 7.4]. Demographic and clinical characteristics for participants according to quartile of national ADI (increasing socioeconomic disadvantage) are presented in Table 1. Relative to patients in the bottom quartile of national ADI (least disadvantaged), patients in the top quartile (most disadvantaged) were significantly more likely to be female (78.9 versus 68.9%), Black/African American (37.6 versus 8.7%), current smokers (18.5 versus 7.7%), obese (42.4 versus 20.8%) or have additional comorbidity (16.6 versus 11.7%). Demographic characteristics were similarly distributed across national ADI quartiles when restricting to 552 participants with neighbourhood-level SES indices available within 3 years of symptom onset (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of included study participants across quartile of National ADI

| Approximate quartile of National ADI |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Q1 (least disadvantaged) | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 (most disadvantaged) | |

| n | 789 | 196 | 188 | 200 | 205 |

| ADI state, mean (SD) | 4.36 (2.67) | 1.39 (0.55) | 3.17 (0.94) | 5.12 (1.51) | 7.55 (1.90) |

| ADI national, mean (SD) | 26.60 (21.60) | 4.96 (2.53) | 15.18 (3.08) | 27.78 (4.52) | 56.61 (17.06) |

| Median household income, median (SD) | 96 497.64 (44 326.56) | 155 071.56 (38 707.45) | 99 694.81 (17 501.74) | 77 839.26 (14 239.70) | 55 561.87 (18 872.18) |

| AHRQ SES Index, mean (SD) | 63.49 (7.77) | 71.07 (4.28) | 65.61 (4.69) | 62.40 (4.62) | 54.87 (6.56) |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 15.84 (2.56) | 16.72 (2.28) | 15.88 (2.72) | 15.80 (2.40) | 14.99 (2.56) |

| Residence in MD, VA, DE, D.C., WV or PA, n (%) | 737 (93.4) | 183 (93.4) | 178 (94.7) | 187 (93.5) | 189 (92.2) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 40.01 (11.21) | 42.28 (10.98) | 41.42 (11.43) | 37.83 (10.78) | 38.67 (11.13) |

| Hispanic or Latino, n (%) | 20 (2.5) | 4 (2.0) | 5 (2.7) | 5 (2.5) | 6 (2.9) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||

| White | 586 (74.3) | 165 (84.2) | 150 (79.8) | 153 (76.5) | 118 (57.6) |

| Black/African American | 157 (19.9) | 17 (8.7) | 29 (15.4) | 34 (17.0) | 77 (37.6) |

| Other | 46 (5.8) | 14 (7.1) | 9 (4.8) | 13 (6.5) | 10 (4.9) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 200 (25.3) | 61 (31.1) | 57 (30.3) | 39 (19.5) | 43 (21.0) |

| Disease duration, mean (SD) | 5.58 (5.07) | 5.38 (4.70) | 6.26 (5.80) | 5.48 (4.77) | 5.23 (4.98) |

| Progressive MS, n (%) | 28 (14.3) | 33 (17.6) | 24 (12.0) | 28 (13.7) | |

| Number of DMT switches before first OCT, median (range) | 0.48 (0.93) | 0.53 (0.94) | 0.52 (0.94) | 0.47 (0.92) | 0.42 (0.92) |

| History of optic neuritis, n (%) | 94 (11.9) | 19 (9.7) | 23 (12.2) | 32 (16.0) | 20 (9.8) |

| Baseline DMT, n (%) | |||||

| Infusion | 139 (17.6) | 37 (19.0) | 34 (18.1) | 38 (19.0) | 30 (14.6) |

| Injectable | 364 (46.2) | 95 (48.7) | 96 (51.1) | 84 (42.0) | 89 (43.4) |

| Oral | 111 (14.1) | 23 (11.8) | 21 (11.2) | 30 (15.0) | 37 (18.0) |

| None | 171 (21.7) | 40 (20.5) | 35 (18.6) | 47 (23.5) | 49 (23.9) |

| Other | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 28.21 (6.89) | 26.72 (5.47) | 28.39 (6.12) | 27.91 (7.70) | 29.76 (7.59) |

| Any comorbiditya, n (%) | 113 (14.3) | 23 (11.7) | 26 (13.8) | 30 (15.0) | 34 (16.6) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 104 (13.2) | 15 (7.7) | 28 (14.9) | 23 (11.5) | 38 (18.5) |

Any comorbidity denotes a history of hypertension, depression, dyslipidaemia, COPD, diabetes, migraine, coronary artery disease, obstructive sleep apnoea or osteoporosis.

Socioeconomic status indicators and GCIPL atrophy in patients with multiple sclerosis

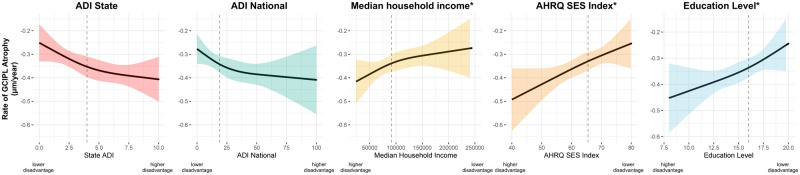

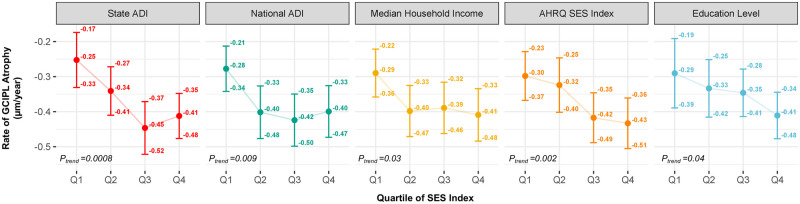

Using the neighbourhood-level SES indices, individuals with lower SES (more disadvantaged) had faster rates of GCIPL atrophy (Table 2). For example, the differences in annual rate of GCIPL atrophy from multivariable-adjusted models for participants in the top quartile (most disadvantaged) relative to the lowest quartile (least disadvantaged) was −0.12 µm/year faster (95% CI: −0.20, −0.04) for state ADI, −0.08 µm/year faster (95% CI: −0.16, −0.004) for national ADI, −0.08 µm/year faster (95% CI: −0.16, −0.001) for median household income and −0.12 µm/year faster (95% CI: −0.19, −0.04) for AHRQ SES Index. Consistent results were observed for participant-level SES indicators with individuals in the bottom quartile of education (least educated) having faster rates of GCIPL atrophy relative to those in the top quartile of education (most educated; −0.17 µm/year faster; 95% CI: −0.26, −0.08). Results were also similar in linear models and models using restricted cubic splines where continuous neighbourhood and patient-level SES indices were associated with faster GCIPL atrophy (Fig. 1). We did not detect significant deviations from linearity for the national ADI, median household income, AHRQ SES Index or education (all P > 0.05). We did note some deviation from linearity and a potential threshold effect for state ADI (P = 0.05). Similar findings were observed when we restricted the study population to individuals with SES indices available within 3 years of symptom onset (n = 552; Fig. 2). Consistent findings for both neighbourhood-level and participant-level indices were observed when we considered rate of change in pRNFL as the outcome (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Table 2.

SES indices and rate of GCIPL atrophy

| Approximate Quartile of National ADI |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (least disadvantaged) | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 (most disadvantaged) | P for trend* | |

| Neighbourhood-level SES indicators | |||||

| ADI state, rate of changea (95% CI) | −0.26 (−0.32, −0.20) | −0.33 (−0.38, −0.28) | −0.38 (−0.44, −0.32) | −0.38 (−0.43, −0.33) | 0.002 |

| ADI national, rate of change (95% CI) | −0.29 (−0.34, −0.24) | −0.36 (−0.41, −0.30) | −0.36 (−0.42, −0.30) | −0.37 (−0.43, −0.31) | 0.04 |

| Median household income, rate of change (95% CI)b | −0.30 (−0.35, −0.25) | −0.35 (−0.40, −0.29) | −0.35 (−0.41, −0.29) | −0.38 (−0.44, −0.32) | 0.05 |

| AHRQ SES Index (95% CI)b | −0.29 (−0.35, −0.24) | −0.30 (−0.36, −0.24) | −0.37 (−0.43, −0.32) | −0.41 (−0.47, −0.35) | 0.001 |

| Participant-level SES indicators | |||||

| Education level, rate of change (95% CI)b | −0.23 (−0.31, −0.16) | −0.32 (−0.39, −0.26) | −0.31 (−0.36, −0.26) | −0.41 (−0.46, −0.35) | 0.0004 |

All rates of change are adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, history of optic neuritis, disease subtype, resident of Maryland, Virginia, Washington D.C., Delaware or Pennsylvania, number of DMTs before first OCT, highest DMT class before first OCT, smoking status, BMI and any comorbidity at baseline, time between SES indicator and first OCT.

For median household income, AHRQ SES Index, and education level quantiles scores were reversed such that higher quantiles (quartile 4) denote higher levels of disparity to match ADI indices.

P for trend denotes the P-value derived from a test of trend across quartiles in which an individual’s quartile value was modelled as a continuous covariate.

Figure 1.

Association between continuous SES indices and rate† of GCIPL decline*. Association between SES indices and rate of change in GCIPL (P-values for likelihood ratio tests for state ADI: P = 0.002, national ADI: P = 0.02, median household income: P = 0.18, AHRQ SES Index: P = 0.001 and years of education: P = 0.005) using restricted cubic splines. The dotted lines denote the median of the distribution of a given SES Index. Solid lines denote the rate of change in GCIPL associated with a given SES Index value (centred around the median SES Index value), and shaded regions denote the 95% CI. †All models are adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, history of optic neuritis, disease subtype, resident of Maryland, Virginia, Washington D.C., Delaware or Pennsylvania, number of DMTs before first OCT, highest DMT class before first OCT, smoking status, baseline BMI, any comorbidity at baseline, time between SES indicator and first OCT. We did not detect significant deviations from linearity for the AHRQ SES Index (P = 0.42), median household income (P = 0.79), national ADI (P = 0.11) or education (P = 0.37). We did note some marginal deviation from linearity and a potential threshold effect for state ADI (P = 0.06). *For median household income, AHRQ SES Index and years of education, higher values denote higher levels of SES.

Figure 2.

SES indices and rate† of GCIPL atrophy* among individuals with neighbourhood-level SES within 3 years of multiple sclerosis symptom onset (n = 552). †All rates of change are adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, history of optic neuritis, disease subtype, resident of Maryland, Virginia, Washington D.C., Delaware or Pennsylvania, number of DMTs before first OCT, highest DMT class before first OCT, smoking status, BMI, any comorbidity, time between SES indicator and first OCT. *Ptrend denotes the P-value derived from a test of linear trend across quartiles in which an individual’s quartile value was modelled as a continuous covariate. For median household income, AHRQ SES Index and education level quantiles scores were reversed such that higher quantiles (quartile 4) denote higher levels of disparity to match ADI indices.

In sensitivity analyses, we also observed consistent results when we adjusted for DMT or smoking as time-varying covariates as well as when we excluded individuals with hypertension or diabetes. Results were relatively similar when adjusting for measured vitamin D levels, which were available in a subset of individuals (n = 630). We also obtained relatively consistent results of faster GCIPL atrophy with increasing socioeconomic disadvantage when we created race-specific quartiles (e.g. cut-off points to assign quartile rankings were derived separately in each racial group) and when we excluded traditionally marginalized groups (e.g. Black/African Americans and Hispanic or Latino individuals) suggesting the observed association is also apparent in other populations as well (Supplementary Figs 2 and 3). Formal tests for effect modification did not detect significant differences in associations of neighbourhood-level SES indices and GCIPL decline between Black/African American (n = 157) and white participants (n = 586; Supplementary Fig. 4; all P for interaction >0.05). Interestingly, we did note a potential difference in the association between education level and GCIPL decline between Black/African American and white participants (P for interaction = 0.05).

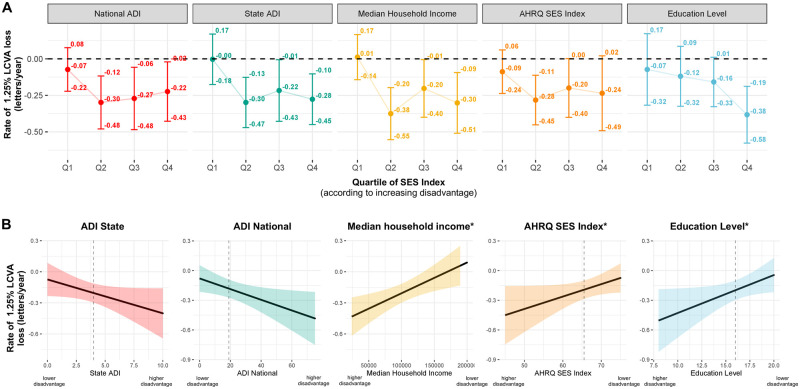

Socioeconomic status indicators and LCLA loss in patients with multiple sclerosis

LCLA information was available in a subset of 652 individuals. We observed generally similar findings in models assessing SES indices as they relate to LCLA (Fig. 3A). For example, differences in the rate of LCLA loss at 1.25% contrast for individuals in the top quartile (most disadvantaged) relative to the bottom quartile (least disadvantaged) for state ADI were −0.27 letters per year faster (95%CI: −0.52, −0.02; P = 0.03), for median household income were −0.31 letters per year faster (95%CI: −0.57, −0.05; P = 0.02), and for education level were −0.31 letters per year faster (95% CI: −0.62, 0.00; P = 0.05) than those in the bottom quartile (least disadvantaged). Results were also similar in linear models where continuous neighbourhood and patient-level SES indices were associated with faster LCLA loss (Fig. 3B). Consistent findings were also observed in models assessing SES indices and LCLA at 2.5% contrast.

Figure 3.

SES indices and rate of LCLA loss† at 1.25% (n = 652) using (A) quartiles* and (B) and using linear models**. †All rates of change are adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, history of optic neuritis, disease subtype, resident of Maryland, Virginia, Washington D.C., Delaware or Pennsylvania, number of DMTs before first OCT, highest DMT class before first OCT, smoking status, BMI, any comorbidity, time between SES indicator and first OCT. ‡For median household income, AHRQ SES Index and education level quantiles scores were reversed such that higher quantiles (quartile 4) denote higher levels of disparity to match ADI indices. *Ptrend denotes the P-value derived from a test of linear trend across quartiles in which an individual’s quartile value was modelled as a continuous covariate. **Association between SES indices and rate of change in LCLA at 1.25% (P-values for likelihood ratio tests for state ADI: P = 0.04, national ADI: P = 0.02, median household income: P = 0.02, AHRQ SES Index: P = 0.07 and years of education: P = 0.04).

Socioeconomic status indicators and multiple sclerosis therapy changes

We next explored whether the observed associations between SES indices and GCIPL were potentially related to contemporaneous differential multiple sclerosis management across different levels of SES. Individuals with greater than or equal to the median of national ADI scores (higher disadvantage) had a 39% faster time to therapy escalation and a 32% faster rate of any therapy change relative to those with lower than the median national ADI scores (lower disadvantage) [Supplementary Fig. 5; hazard ration (HR) for therapy escalation: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.12, 1.73; HR for any therapy change: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.62]. In sensitivity analyses, when we considered shifts from low or moderate to higher potency DMTs, we observed consistent results. For example, individuals with greater than or equal to the median of national ADI scores had a 35% faster rate of therapy escalation relative to those with lower than the median national ADI (HR: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.68). Relatively consistent results were observed for other neighbourhood-level SES indices and therapy escalation (Supplementary Table 2). SES indices were not associated with therapy de-escalation (HR: 1.05; 95% CI: 0.51, 2.17).

Socioeconomic status indicators and incident comorbidity

Last, we assessed whether lower SES was associated with higher risk of comorbidity among 676 individuals without comorbidities at baseline; 213 developed a new comorbidity over follow-up. For each neighbourhood-level and participant-level SES Index, individuals with lower SES (more disadvantaged) had a higher risk of new comorbidity development relative to those with higher SES (less disadvantaged; Table 3). For example, those in the top quartile of national ADI had a 90% increase risk of developing a new comorbidity over follow-up relative to those in the bottom quartile of national ADI (HR: 1.90; 95% CI: 1.23, 2.93). With respect to individual comorbidities, new onset depression was the most common (105 cases over follow-up); we detected a significant trend towards increased risk of depression across quartiles of national ADI (increasing disadvantage) (Supplementary Table 3; P for trend = 0.04). Lower SES was also associated with a faster rate of BMI increases over the course of follow-up. Individuals in the top quartile of national ADI (most disadvantaged) had a significant increase of 1.00 (0.69, 1.30) BMI units per 5 years, whereas those in the bottom quartile of national ADI (least disadvantaged) had an insignificant increase of 0.15 (−0.09, 0.39) BMI units per 5 years (Supplementary Fig. 6). In formal mediation analyses where we evaluated whether changes in BMI mediated the observed effect between national ADI and GCIPL atrophy, we observed that a small percentage (3.16%) of the observed association (slope) between national ADI and GCIPL thickness was mediated through change in BMI specifically (natural indirect effect: −0.001; 95% CI: −0.006, 0.000; natural direct effect: −0.046; 95% CI: −0.10, −0.004). Similar results were observed for models using continuous measures of SES and for other SES indices.

Table 3.

SES indices and risk of new onset comorbiditya

| Quartile of SES variable |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (least disadvantaged) |

Q2 | Q3 | Q4 (most disadvantaged) |

P for trend* | |

| Neighbourhood-level SES indicators | |||||

| ADI state, HRa (95% CI) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.35 (0.88, 2.07) | 1.23 (0.77, 1.94) | 1.90 (1.23, 2.93) | 0.006 |

| ADI national, HR (95% CI) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.23 (0.83, 1.84) | 1.58 (1.05, 2.36) | 1.69 (1.12, 2.55) | 0.006 |

| Median household income, HR (95% CI)b | 1.00 (reference) | 1.44 (0.96, 2.14) | 1.88 (1.26, 2.81) | 1.80 (1.17, 2.76) | 0.003 |

| AHRQ SES Index HR (95% CI)b | 1.00 (reference) | 1.29 (0.86, 1.92) | 1.32 (0.87, 2.00) | 1.76 (1.15, 2.68) | 0.01 |

| Participant-level SES indicators | |||||

| Education level, HR (95% CI)b | 1.00 (reference) | 1.32 (0.78, 2.24) | 1.04 (0.63, 1.71) | 1.76 (1.08, 2.89) | 0.03 |

Denotes new onset hypertension, depression, dyslipidaemia, COPD, diabetes, migraine, coronary artery disease, obstructive sleep apnoea or osteoporosis. We excluded participants with these comorbidities at baseline; 213 developed new onset comorbidity among 676 eligible participants. All rate ratios are adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, disease subtype, resident of Maryland, Virginia, Washington D.C., Delaware or Pennsylvania, number of DMTs before first OCT, and smoking status.

For median household income, AHRQ SES Index and education level quantiles scores were reversed such that higher quantiles (quartile 4) denote higher levels of disparity to match ADI indices.

P for trend denotes the P-value derived from a test of trend across quartiles in which an individual’s quartile value was modelled as a continuous covariate.

Discussion

In this large longitudinal study of nearly 800 individuals with multiple sclerosis, we found that socioeconomic disparity is associated with significantly increased rates of progressive retinal atrophy and vision loss. Consistent results were generally observed when considering various neighbourhood-level (e.g. those derived using participant nine-digit postal codes) as well as participant-level indicators of SES (e.g. education level). Secondary analyses also found that socioeconomic disparity was associated with a higher risk of new comorbidities, and a portion of the observed effect between SES and GCIPL atrophy may be mediated through changes in BMI specifically. Moreover, our analyses also show that the observed differences in rates of GCIPL atrophy or LCLA loss may not be related to differences in contemporaneous multiple sclerosis management, as lower SES individuals tended to escalate their multiple sclerosis therapies at a faster rate when compared to those with higher SES.

Substantial previous literature has detailed significant associations between lower SES and higher risk of chronic disease, greater functional limitations and poorer health outcomes in the general population.30 With respect to multiple sclerosis, relatively few studies have explored whether SES affects disease risk or progression, especially in distinct societal settings where socioeconomic inequalities exhibit a pronounced adverse effect on individual welfare, ergo an overt impact on disease outcome.31,32 A previous study including multiple sclerosis patients from the UK and Canada found that greater socioeconomic disadvantage at disease onset was associated with a faster time to needing a cane and conversion to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Another French study found consistent results in the association between socioeconomic deprivation and faster rates of reaching disability milestones.33 Other retrospective and cross-sectional studies have found similar associations between lower education or lower self-reported income were associated with greater disability levels, time to reaching a cane, cognitive dysfunction and affective symptom burden.34–37 Our study builds on existing studies as our primary outcome, GCIPL thinning, is a highly sensitive marker reflecting global CNS neurodegeneration and disease progression in multiple sclerosis, with the potential to more readily capture subtle changes than clinical outcomes often focused on in previous studies (e.g. the broadly classified disability outcomes including time to use of a cane). Thus, it is likely the observed differences in disease outcomes associated with socioeconomic disadvantages were detected at a much earlier stage in disease course or among participants with a less pronounced clinical course.

We also note that the association between SES indices and GCIPL atrophy was observed, despite adjustment for multiple other demographic, clinical and multiple sclerosis characteristics, and though the observed effect size is not demonstrably large, our results highlight important health disparities. Also, while average follow-up for this study is nearly 5 years, multiple sclerosis is a disease that evolves over decades; the relative increase in retinal neurodegeneration associated with SES is likely to be meaningful downstream. Taken together, findings implicate the importance of understanding contributing sociobiological mechanisms as well as motivating policy-level changes that may facilitate improved care and better disease outcomes for disadvantaged individuals. Last, taking into account that low-SES participants had higher risk of incident comorbidity during follow-up, the effect of SES in combination to comorbidity-induced GCIPL thickness loss could be impactful, highlighting the need of appropriate management of preventable risk factors, particularly in this group.

The mechanisms accounting for the observed associations are not easily delineated, as SES is a highly complex construct. Previous studies have linked comorbidity with worse multiple sclerosis outcomes.4 Notably, in this study we observed an association between higher levels of socioeconomic disparity and risk of newly developed comorbidities. Future larger studies should formally assess mediation by incident comorbidity and assess whether targeted comorbidity prevention or more optimal comorbidity management among low-SES individuals is an intervenable way to mitigate some adverse SES consequences. It is also worth noting that socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods often have a higher exposure to multiple environmental hazards including air pollution, contaminated water sources and proximity to industrial facilities, which have known links to adverse health outcomes.38–40 Chronic stress of socioeconomic disadvantage could also promote neurodegeneration.41 Evaluation of these specific measures in relation to multiple sclerosis outcomes is also likely to be relevant.

In multiple sclerosis, therapeutic management is crucial in modifying multiple sclerosis outcomes. We had hypothesized that individuals with lower SES may have additional challenges in accessing to healthcare, limited insurance coverage or higher co-pays that may hinder their access to higher efficacy (and typically more costly) treatments than people of higher SES. While SES may have affected previous therapeutic strategies before study initiation, our results indicate that over the study period, more disadvantaged patients exhibited faster retinal neurodegeneration despite their tendency to have faster rates therapeutic escalation. These observations suggest a multi-faceted impact of SES on disease outcomes that could not be attributed solely to differential cotemporaneous therapeutic approaches.

Also notable was our finding that lower SES was associated with a faster rate of increasing BMI or weight gain (as in our population of adults, height is relatively constant). Excess adiposity tends to accrue during early and middle adulthood for most individuals in the USA, where a modest increase of 0.5–1.0 kg per year eventually results in obesity over time.29 Previous large-scale studies demonstrate that moderate weight gain (e.g. 2.5–10 kg) over a 15-year period during early to middle adulthood was associated with a higher risk of hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease or obesity-related cancers.29 In our study, we found that low-SES individuals with multiple sclerosis have an increase of ∼2.75 kg in weight over course of a 5-year period, which is consistent with the observed higher risk of comorbidity detected. Our results also suggest that at least a portion of the observed association between SES and GCIPL atrophy may be mediated through changes in weight and links excess adiposity specifically with multiple sclerosis outcomes.

Strengths of this study are highlighted by our use of an imaging phenotype, GCIPL thickness, as a robust, highly sensitive measure of disease course with the capacity to detect subtle degenerative changes in people with multiple sclerosis. Previous studies also strongly link GCIPL thinning with rates of brain and grey matter volume loss as well as 10-year disability outcomes in people with multiple sclerosis.19,42 Similarly, higher lesion volume, lower brain volume and increased damage to optic radiations are associated with impaired LCLA in multiple sclerosis.43,44 The use of a clinical measure such as LCLA as a surrogate of disease progression, with similar outcomes across different SES quartiles, functions as a second layer of validation and enhances the association of socioeconomic disadvantage with unfavourable disease outcomes in multiple sclerosis. We also included a population of nearly 800 well-phenotyped multiple sclerosis patients who were followed systematically for ∼5 years. Analyses considered several measures of SES indices that are each composed of unique components thought to be contributors to an individual’s overall estimated SES. We also incorporated education as our individual-level SES Index. Relative to other patient-level indicators such as income status, education level may be a more robust measure of SES to consider, as the highest level of education attained commonly occurs before disease onset. Our analysis was also unique in that we considered the effects of SES and comorbidity risk as well as performed mediation analyses in which we evaluated whether any of the observed association between SES and GCIPL atrophy was mediated through change in BMI, a previous predictor of GCIPL thinning with strong links to comorbidity risk.5 Last, we performed several sets of sensitivity analyses in which we assessed how varying assumptions of our analyses could affect the findings and our conclusions.

Our study has several important limitations. First, we included neighbourhood-level SES indices that are derived using nine-digit postal codes at an ecologic/group level rather than at individual level. While this could introduce measurement error, nine-digit postal codes translate to a relatively small geographic area and each index has been extensively validated. Further, we also included education level as a participant-level proxy for SES to address this potential bias. Second, participants in our study are US residents, mostly of urban or suburban areas of Maryland or Washington D.C., a population cohort that may not be representative of the USA or world multiple sclerosis population. Nevertheless, given the unique pattern of societal structure and health inequalities across the US social gradient, our model represents a highly applicable platform for the in-depth study of the effect of SES on clinical progression of multiple sclerosis patients in other regions. While the use of OCT as a clinical monitoring tool in multiple sclerosis is becoming increasingly common, future studies should incorporate more traditional brain imaging and other clinical outcome metrics. Additionally, while we evaluated potential effect modification by race and adjusted all analyses for race and ethnicity, it is possible these analyses were underpowered since our population of Black/African Americans was relatively limited and tended to be at greater socioeconomic disadvantage when compared to white participants. Thus, identification of overt differences in SES’s impact on GCIPL atrophy across races may have been particularly challenging, especially given longstanding housing and education discrimination disproportionally affecting Black/African Americans. Future studies using more geographically representative and racially and ethnically diverse populations should evaluate similar hypotheses detailed herein. We also present results including participants for which SES indices were measured within 10 years of symptom onset when it is possible that individual’s adverse multiple sclerosis-related health consequences could have negatively impacted SES during that period. Still, consistent findings were observed when we further restricted the interval between symptom onset and SES assessment to 3 years. We also lacked detailed measures of diet (beyond vitamin D levels), exercise, alcohol use and sleep for participants, which could vary by SES and could impact rates of disease progression in multiple sclerosis. Last, comorbidities considered in this analysis were identified using diagnostic codes derived from the electronic medical record, which could be inaccurate.

Socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals have an increased risk of retinal neurodegeneration and subsequently, faster subclinical disease progression in multiple sclerosis. Underlying contributing mechanisms are undoubtedly complex. However, acknowledging the impact of such inequalities on the variability of disease outcomes may aid in the implementation of more efficient management strategies as well as therapeutic approaches that may benefit the less privileged.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients who made this study possible and all those who helped in carrying out this project.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (1K01MH121582-01 to K.C.F., R01NS082347 to P.A.C.), the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (TA-1805–31136 to K.C.F., RG-1606–08768 to S.S.), Race to Erase Multiple Sclerosis Foundation (to S.S.), Biogen Idec (to S.S.) and Genentech Corporation (to S.S.).

Competing interests

E.S.S. has served on scientific advisory boards for Alexion, Viela Bio and Genentech, and has received speaker honoraria from Viela Bio and Biogen. S.S. has received consulting fees from Medical Logix for the development of CME programs in neurology and has served on scientific advisory boards for Biogen, Genzyme, Genentech Corporation, EMD Serono & Celgene. He is the PI of investigator-initiated studies funded by Genentech Corporation and Biogen Idec, received support from the Race to Erase MS foundation, and was the site investigator of a trial sponsored by MedDay Pharmaceuticals. He has received equity compensation for consulting from JuneBrain LLC, a retinal imaging device developer. E.M.M. has grants from Biogen, is site PI for studies sponsored by Biogen and Genentech, has received free medication for a clinical trial from Teva, and receives royalties for editorial duties from UpToDate. P.A.C. has received consulting fees from Disarm, NervGen and Biogen and is PI on grants to JHU from Genentech. All other authors report no competing interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

Glossary

- ADI

area deprivation index

- AHRQ

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; BMI = body mass index

- DMT

disease modifying therapy

- GCIPL

ganglion and inner plexiform layer

- LCLA

low contrast letter acuity

- OCT

optical coherence tomography

- SES

socioeconomic status

References

- 1.Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al. ; US Multiple Sclerosis Prevalence Workgroup. The prevalence of MS in the United States: A population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1029–e1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reich DS, Lucchinetti CF, Calabresi PA.. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2014;83(3):278–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marrie RA. Comorbidity in multiple sclerosis: Implications for patient care. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(6):375–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filippatou AG, Lambe J, Sotirchos ES, et al. Association of body mass index with longitudinal rates of retinal atrophy in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2020;26(7):843–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzgerald KC, Damian A, Conway D, Mowry EM.. Vascular comorbidity is associated with lower brain volumes and lower neuroperformance in a large multiple sclerosis cohort. Mult Scler. 2021:27(12):1914–1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimbrough DJ, Sotirchos ES, Wilson JA, et al. Retinal damage and vision loss in African American multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol. 2015;77(2):228–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caldito NG, Saidha S, Sotirchos ES, et al. Brain and retinal atrophy in African-Americans versus Caucasian-Americans with multiple sclerosis: A longitudinal study. Brain. 2018;141(11):3115–3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winkleby MA, Jatulis DE, Frank E, Fortmann SP.. Socioeconomic status and health: How education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(6):816–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bircher J, Kuruvilla S.. Defining health by addressing individual, social, and environmental determinants: New opportunities for health care and public health. J Public Health Policy. 2014;35(3):363–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kivimäki M, Batty GD, Pentti J, et al. Association between socioeconomic status and the development of mental and physical health conditions in adulthood: A multi-cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(3):e140–e149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loucks EB, Pilote L, Lynch JW, et al. Life course socioeconomic position is associated with inflammatory markers: The Framingham Offspring Study. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(1):187–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harding KE, Wardle M, Carruthers R, et al. Socioeconomic status and disability progression in multiple sclerosis: A multinational study. Neurology. 2019;92(13):e1497–e1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mowry EM, Azevedo CJ, McCulloch CE, et al. Body mass index, but not vitamin D status, is associated with brain volume change in MS. Neurology. 2018;91(24):e2256–e2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown JWL, Coles A, Horakova D, et al. ; MSBase Study Group. Association of initial disease-modifying therapy with later conversion to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. JAMA. 2019;321(2):175–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kowalec K, McKay KA, Patten SB, et al. ; CIHR Team in Epidemiology and Impact of Comorbidity on Multiple Sclerosis (ECoMS). Comorbidity increases the risk of relapse in multiple sclerosis: A prospective study. Neurology. 2017;89(24):2455–2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Syc SB, Warner CV, Hiremath GS, et al. Reproducibility of high-resolution optical coherence tomography in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2010;16(7):829–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saidha S, Al-Louzi O, Ratchford JN, et al. Optical coherence tomography reflects brain atrophy in multiple sclerosis: A four-year study. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(5):801–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petzold A, Balcer LJ, Calabresi PA, et al. Retinal layer segmentation in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(10):797–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tewarie P, Balk L, Costello F, et al. The OSCAR-IB consensus criteria for retinal OCT quality assessment. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cruz-Herranz A, Balk LJ, Oberwahrenbrock T, et al. ; IMSVISUAL consortium. The APOSTEL recommendations for reporting quantitative optical coherence tomography studies. Neurology. 2016;86(24):2303–2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, et al. Racial variation in medical outcomes among living kidney donors. New Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):724–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moy E, Greenberg LG, Borsky AE.. Community variation: Disparities in health care quality between Asian and white Medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(2):538–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kind AJH, Jencks S, Brock J, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: A retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):765–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh GK. Area deprivation and widening inequalities in US mortality, 1969-1998. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(7):1137–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trip SA, Schlottmann PG, Jones SJ, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer axonal loss and visual dysfunction in optic neuritis. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(3):383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bind M.-A C, Vanderweele TJ, Coull BA, Schwartz JD.. Causal mediation analysis for longitudinal data with exogenous exposure. Biostatistics. 2016;17(1):122–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng Y, Manson JE, Yuan C, et al. Associations of weight gain from early to middle adulthood with major health outcomes later in life. JAMA. 2017;318(3):255–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minkler M, Fuller-Thomson E, Guralnik JM.. Gradient of disability across the socioeconomic spectrum in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(7):695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crimmins EM, Preston SH, Cohen B; National Research Council (US) Panel on Understanding Divergent Trends in Longevity in High-Income Countries. International differences in mortality at older ages. National Academies Press (US; ); 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi H, Steptoe A, Heisler M, et al. Comparison of health outcomes among high- and low-income adults aged 55 to 64 years in the US vs England. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(9):1185–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calocer F, Dejardin O, Kwiatkowski A, et al. Socioeconomic deprivation increases the risk of disability in multiple sclerosis patients. Multiple Scler Related Disord. 2020;40:101930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilski M, Tasiemski T, Kocur P.. Demographic, socioeconomic and clinical correlates of self-management in multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(21):1970–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.D'hooghe MB, Haentjens P, Van Remoortel A, De Keyser J, Nagels G.. Self-reported levels of education and disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2016;134(6):414–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Tian F, Fitzgerald KC, et al. Socioeconomic status and race are correlated with affective symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;41:102010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martins Da Silva A, Cavaco S, Moreira I, et al. Cognitive reserve in multiple sclerosis: Protective effects of education. Mult Scler. 2015;21(10):1312–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su JG, Jerrett M, Morello-Frosch R, Jesdale BM, Kyle AD.. Inequalities in cumulative environmental burdens among three urbanized counties in California. Environ Int. 2012;40:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morello-Frosch R, Shenassa ED.. The environmental “riskscape” and social inequality: Implications for explaining maternal and child health disparities. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(8):1150–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morello-Frosch R, Zuk M, Jerrett M, Shamasunder B, Kyle AD.. Understanding the cumulative impacts of inequalities in environmental health: Implications for policy. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(5):879–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madore C, Yin Z, Leibowitz J, Butovsky O.. Microglia, lifestyle stress, and neurodegeneration. Immunity. 2020;52(2):222–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rothman A, Murphy OC, Fitzgerald KC, et al. Retinal measurements predict 10-year disability in multiple sclerosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6(2):222–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maghzi A-H, Revirajan N, Julian LJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging correlates of clinical outcomes in early multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3(6):720–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu GF, Schwartz ED, Lei T, et al. Relation of vision to global and regional brain MRI in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2007;69(23):2128–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

De-identified data may be available on request for investigators whose proposed use has been approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of institution of the principal investigator.