Abstract

Objective

Paediatric vision screening programs identify children with ocular abnormalities who would benefit from treatment by an eye care professional. A questionnaire was conducted to assess existence and uptake of school-based vision screening programs across Canada. A supplementary questionnaire was distributed among Ontario’s public health units to determine implementation of government mandated vision screening for senior kindergarten children.

Methods

Chief Medical Officers of Health for each province and territory, and Ontario’s thirty-four public health units were sent a questionnaire to determine: 1) whether school-based vision screening is being implemented; 2) what age groups are screened; 3) personnel used for vision screening; 4) the type of training provided for vision screening personnel; and 5) vision screening tests performed.

Results

Of the thirteen provinces/territories in Canada, six perform some form of school-based vision screening. Two provinces rely solely on non-school-based programs offering eligible children an eye examination by an optometrist and three rely on ocular assessment conducted by a nurse at well-child visits. In Ontario, where since 2018 vision screening for all senior kindergarten students is government mandated, only seventeen public health jurisdictions are implementing universal vision screening programs using a variety of personnel ranging from food safety workers to optometrists.

Conclusion

Good vision is key to physical and emotional development. There is an urgent need for a universal, evidence-based and cost-effective multidisciplinary approach to standardize paediatric vision screening across Canada and break down barriers preventing children from accessing eye care.

Keywords: Ophthalmology, Public Health, Vision Screening

Paediatric vision screening programs are designed to identify children with ocular abnormalities and refer them to eye care professionals. A child’s inability to self-identify as having poor vision due to failure of one eye to develop means amblyopia may not be identified until later in life when they are left with irreversible monocular vision loss. It has been estimated that for each forty-eight children screened at age 3 to 4 years, one case of adult amblyopia is prevented (1). In developed countries, amblyopia is the primary cause of monocular blindness in the 20 to 70-year-old age range (2). Amblyopia affects an individual’s health and function and confers a significantly higher risk of total blindness (3).

An amblyopic individual is almost twice as likely to develop total blindness compared to the general population (4,5). A retrospective chart review conducted at the University of California found nearly seventeen per cent of all monocular patients eventually developed blindness in their fellow eye (6).

Growing up with amblyopia also means routine ocular procedures such as cataract surgery not only carry significantly higher risks than when performed on an individual with only one seeing eye, but also are often delayed, causing increased, continued morbidity to the patient (7). Furthermore, with the increasing prevalence of age-related macular degeneration (projected to affect one in ten Americans by 2050), a growing number of amblyopic adults will suffer with bilateral vision loss due to macular degeneration (8).

Numerous studies have shown that health consequences associated with vision loss extend beyond the eye and visual system. A child left untreated for visual abnormalities can experience reduced function and quality of life, increased psychological problems, decreased educational attainment, and loss of income (3,9). An Australian study conducted on grade three children highlights the importance of early screening, as those that failed a standard vision screening were found to have the lowest academic standing (10). In fact, eighty-eight per cent of visually impaired Canadian adults felt their impaired vision directly impacted their educational attainment, career choice, and employability (11).

The aim of vision screening is to detect reduced vision at an early age allowing for timely intervention and treatment (12). Early vision screening targeted at encouraging treatment of amblyopia directly and indirectly benefits all children by preventing amblyopia; improving psychosocial health; preventing increased risk of future bilateral vision loss; and decreasing societal economic burdens. Early vision screening has been associated with a sixty per cent improvement in visual acuity and an overall decrease in the prevalence of amblyopia (13). In Sweden, a national paediatric vision screening program has shown a ten-fold decrease in the incidence of amblyopia (14,15). An estimated twenty-five per cent of school-aged children suffer from visual impairment (16) and may be mistakenly labelled as having a learning disability or behavioural problems (10,15,16).

Economically, a 2013 study found the annual cost to the USA due to vision loss to be $139 billion (9). In Canada, the total financial cost of vision loss in 2007 was estimated to be $27.5 billion. This figure is expected to rise as the number of Canadians with vision loss is projected to double over the next twenty-five years (17). Providing school-based vision screening to detect amblyogenic eye disease, increase awareness, and encourage parents to take children to an eye care specialist can help ameliorate this emerging vision health crisis. Doing so could, in turn, mitigate the substantial economic burden related to vision loss. The cost of vision screening is minimal, having been estimated to be only $19 per child after initial startup costs (18).

Although many developed countries including Canada, the UK, and the USA have vision screening programs, the consistency of such programs vary in terms of age groups examined and methods of screening (19,20). The US Preventative Services Task Force recommends screening for all children aged 3 to 5 years in order to detect amblyopia (14,21). Forty states across the USA require children entering school for the first time to have vision screening, while three states require full examination by an optometrist (22).

In 2018, Ontario’s Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) mandated vision screening for all school children in senior kindergarten (SK) (23). The Canadian Association of Optometrists recommends all children receive an eye examination by an optometrist or an ophthalmologist at 6 to 9 months of age, at least once between ages 2 to 5 years and annually from age 6 through 19 (24). Despite the above, over eighty-six per cent of children under the age of 6 in Canada have never had an eye examination (25).

METHODS

A national questionnaire was distributed to Chief Medical Officers of Health for each province and territory to assess the existence and uptake of school-based vision screening programs across Canadian provinces and territories. A supplementary questionnaire was distributed among Ontario’s thirty-four public health units to determine the province-wide implementation of school-based vision screening. The aim of both surveys was to determine: 1) how many provinces and territories are implementing a school-based vision screening program for children; 2) what age groups are screened; 3) the personnel used for vision screening; 4) the type of training provided for those performing the vision screening when it is carried out by non-eye care professionals; and 5) the battery of vision screening tests being performed. In contrast with previous similar studies, such as Mema et al. (20), our survey specifically asked about school-based programs, as schools provide a uniquely universal access point for children to receive public health services. The surveys were created on Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) and sent electronically. REDCap is a secure web-based data-management application for creating and managing online surveys and databases. It is specifically used by hospitals and academic institutions to capture data for research studies and operations (26,27). The surveys were confidential, and all information is stored within the study team’s password protected research computer at McMaster Children’s Hospital.

The public health surveys comprised both open-ended and multiple-choice questions. Respondents were given the opportunity to elaborate on answers where necessary in order to provide any additional valuable information. (The questionnaires have been submitted as supplemental material).

RESULTS

Survey responses were received from the public health departments of all thirteen provinces and territories. Only four provinces reported public health-administered vision screening in a school setting: Ontario, British Columbia, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Nova Scotia. The remaining nine provinces and territories either perform school-based vision screening through the Ministry of Education (e.g., Manitoba and Quebec) or rely on opportunistic programs where the onus is on parents to determine when their child will have their vision checked and arrange to take their child to a scheduled appointment.

Table 1 provides a nationwide summary of all current vision screening programs as well as optometric coverage available for children across Canada. Programs such as Eye See…Eye Learn (ESEL) offer eligible children a comprehensive eye examination by a local optometrist and one complimentary pair of eyeglasses if required (28–37). ESEL has rapidly expanded and is carried out in eight provinces while the remaining two provinces (Quebec and New Brunswick) have implemented their own equivalent programs. In Quebec, Participe pour voir (Join and See) covers vision assessments for participating school boards and See Better to Succeed provides a $250 reimbursement for the purchase of eyeglasses or contact lenses for all children under the age of 18 (38,39). In New Brunswick, Healthy Smiles, Clear Vision – Vision Benefit for Four Year Olds encourages parents to have their child’s vision assessed by an eye care professional prior to commencing school (40). Eight of the thirteen provinces and territories in Canada provide optometric coverage for children annually or biennially (30–33,35,39,41,42). Indigenous children (First Nations and Inuit) receive vision care coverage by the federal government through the Non-Insured Health Benefits Program (NIHB) (41). However, the challenge for tens of thousands of indigenous children living on-reserve is that they need to travel hundreds of miles to the nearest eye care professionals in order to receive eye care. In Ontario, children are entitled to an annual comprehensive eye examination by an eye care professional, which is covered by the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) (33).

Table 1.

Provincial and territorial vision care programs for children

| Province or Territory | School-based vision screening program | Children’s age group for school-based vision screening program | Non-school-based vision programs available based on eligibility | Children’s age group for non-school-based vision program eligibility | Optometric coverage for children |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | Yes | 3 years old (daycares) and Kindergarten | Eye See…Eye Learn | Kindergarten (31) | Yes: annually for 0–18 years by Medical Services Plan (MSP) (31) |

| Alberta | No | NA | Eye See…Eye Learn | Kindergarten (32) | Yes: annually for 0–18 years by Alberta Health Insurance Plan (32) |

| Saskatchewan | No | NA | Eye See…Eye Learn | Pre-kindergarten, Kindergarten, G1 (32) | Yes: annually for 0–17 years by Saskatchewan Health Insurance Plan(32) |

| Manitoba | Yes* | Kindergarten and Grades 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 and 11 | Eye See…Eye Learn | Kindergarten (34) |

Yes: every 2 years for 0–18 years by Manitoba Health (34) |

| Ontario | Yes | SK | Eye see…Eye Learn | JK (35) | Yes: annually for 0–19 years by Ontario Health Insurance Plan (35) |

| Quebec |

Yes* | Kindergarten | Particapate pour voir (Join and See – eye examination) See Better to Succeed (eyeglasses) |

5–12 years old (40) Everyone under 18 years reimbursement of fixed amount of $250 for eyeglass/ contact lenses |

Yes: annually for 0–17 years by Quebec Health Insurance Plan (41) |

| Nova Scotia | Yes | Kindergarten | Eye See…Eye Learn | 4 years and 5 years old (36) | Yes: every 2 years for 0–9 years by Medical Services Insurance (MSI) (37) |

| New Brunswick | No | NA | Healthy Smiles, Clear Vision – \ Vision Benefit for Four Year Olds | 4 years old (42) |

No universal provincial eye health coverage |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Yes | Up to G6 | Eye See…Eye Learn** | Kindergarten (39) | No universal provincial eye health coverage |

| Prince Edward Island | No | N/A | Eye See…Eye Learn | Kindergarten (38) | No universal provincial eye health coverage |

| Nunavut | No | NA | No | NA | No*** |

| Yukon | No | NA | No | NA | No |

| Northwest Territories | No | NA | No | NA | Yes: every 2 years for 0–19 years by Northwest Territories Health Care Plan *** (43) |

JK Junior Kindergarten; NA Not Applicable as no program is offered; SK Senior Kindergarten.

*Program is in school setting but is administered by Ministry of Education.

**Program has been postponed due to COVID-19, previously scheduled commencement date of April 1, 2020.

***No optometrists practice in this territory.

In Manitoba and Quebec, there exists a vision screening program for children administered by the Ministry of Education rather than Public Health. In Manitoba, government-supported vision screening is offered to schools, but uptake is declining in favour of opportunistic programs such as ESEL, where the onus is on parents to take their child to a participating optometrist. Conversely, a new pilot program started in 2019 in Quebec called ‘L’école de la vue’, also administered by the Ministry of Education in a public-private partnership (44), has been halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It remains to be seen whether it will continue in future years and what the uptake of such programs will be.

Supplementary Appendix 1 illustrates the supplementary questionnaire response rate of the thirty-four public health units across Ontario. The results identify disparities in province-wide implementation of the government mandated vision screening program. Of the thirty-four Ontario public health units, twenty-one responded to the supplementary survey. All twenty-one of the responding units indicated that they are aware of the Ontario government’s vision screening protocol for SK children, but only seventeen indicated that they have actively begun implementation. The remaining four units that responded to the survey indicated they do not have any vision screening program in place for children.

The four provinces where public health performs school-based vision screening include a wide age range of children from infancy up to older children. At a minimum, all four provinces and all seventeen Ontario public health units performing screening included SK children. Two Ontario units also screened junior kindergarten (JK) children.

These four provinces rely on a variety of personnel such as dental hygienists, nurses, and other non-eye care professionals to perform the screenings. Of the seventeen public health units performing vision screening in Ontario, only one public health unit has eye care professionals (optometrists) directly involved in the administration of vision screening alongside trained non-eye care screeners. Eleven others included personnel with medical training (nurses and dental hygienists) with trained non-eye care screeners (Lions Club Members, university students, public health food workers, administrative assistants, and secretaries). Research has shown non-eye care volunteers can be trained within a short period of time to an accuracy rate of seventy-five percent in correctly identifying a child as having or not having vision impairment (18,43). While a reduction in overall screening cost is one clear benefit to using volunteer vision screeners, the possibility of establishing volunteer-run, robust screening programs in remote communities with less access to health care professionals is of great potential value and importance.

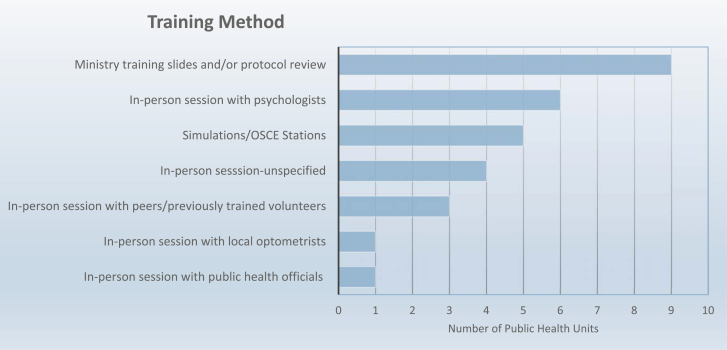

The supplementary Ontario survey also inquired into vision screening training methods employed by public health units. Figure 1 shows the training methods used. Eleven of the seventeen public health units implement measures to assess the skills of vision screening personnel after the initial training session. The majority of units monitor the referral rate from the school-based vision screening programs to eye-care specialists, while two units have unannounced drop-in visits to observe the vision screeners during in-school screening sessions. Six Ontario public health units lacked any form of quality control to ensure adherence to the original standards of training.

Figure 1.

Methods of training for personnel carrying out school-based vision screening programs across Ontario.

The four provinces and seventeen Ontario public health units carrying out school-based vision screening administered by public health all perform a minimum of three screening tests: measurement of visual acuity and stereopsis (depth perception) as well as an autorefractor test, which checks for the presence of strabismus, and whether eyeglasses are needed. All public health units in Ontario performing vision screening provide communication to the child’s parents informing them of the vision screening results.

DISCUSSION

The results of the survey show disparities in vision screening for children and the urgent need to address the issue nationally. These inconsistencies result in children having unequal access to eye care, which can ultimately lead to them falling behind in terms of development and learning.

As there is a persistent lack of public and parental awareness regarding the importance of vision testing for children, school-based vision screening can not only capture children with poor vision, but also help raise public and parental awareness regarding the need for regular comprehensive eye examination for all children.

Vision screening programs differ in terms of the age groups assessed, the screening personnel and the battery of screening tests employed. In Canada, Mema et al. performed a 2012 survey of all thirteen provinces and territories which found seven had public health-operated vision screening programs while ten had optometric coverage for children (20). Since that research was published, some provinces have chosen to end their universal screening programs in favour of opportunistic programs such as ESEL. This trend, ostensibly a cost-saving measure, may end up being the more expensive option if amblyopic children are left untreated as the societal cost and burden of adults with poor vision is more than the cost of vision screening for children.

Unfortunately, even when a jurisdiction mandates universal, in-school vision screening, barriers exist to program uptake. Despite the 2018 Ontario government mandate requiring vision screening for all SK children, only half of public health units had enacted a school-based vision screening program at the time of response. In fact, four public health units that responded to the province-wide survey indicated they have no intention of implementing a paediatric vision screening program in their catchment area. Future research should focus on the barriers that may be preventing public health units from implementing vision screening for school children. Understanding and removing these barriers will allow more children to benefit from vision screening.

Implementing school-based vision screening programs allows for early detection of eye disorders and promotes parental awareness regarding the importance of regular eye examinations for all children. The results of this survey show that the majority of Canadian provinces and territories are not implementing such programs and in those cases where programs exist, uptake is poor. Thus, there is an urgent call to action for a national set of standards for evidence-based, universal vision screening utilizing a multidisciplinary approach and standardized training protocols. Such programs would assist provinces in prioritizing the implementation of universal, school-based vision screening while meeting their unique needs, with the eventual common, national goal of ensuring that no child is left behind due to inadequate vision care.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Paediatrics & Child Health Online.

Supplementary Appendix 1: Supplementary questionnaire response rate among public health units surveyed in Ontario (n=number of public health units).

Author Contributions: YJ conceptualized and designed the study, collected the data, carried out the initial analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript. DN conceptualized and designed the study, collected the data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. NF conceptualized and designed the study, designed the data collection, collected data, carried out the initial analyses, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. KS conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: There are no funders to report.

Potential Conflicts of Interest: All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Guimaraes S, Soares A, Freitas C, et al. Amblyopia screening effectiveness at 3-4 years old: A cohort study. BMJ Open Ophthalmol 2021;6(1):e000599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ederer F, Krueger D.. Report on the National Eye Institute’s Visual Acuity Impairment Survey Pilot Study. Washington, D.C.: National Eye Institute; 1984. [cited March 15, 2021]. 81–84. Available from: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100927812 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Wallace IF, et al. Vision screening in children aged 6 months to 5 years: Evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2017;318(9):845–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Leeuwen R, Eijkemans MJ, Vingerling JR, Hofman A, de Jong PT, Simonsz HJ. Risk of bilateral visual impairment in individuals with amblyopia: The Rotterdam study. Br J Ophthalmol 2007;91(11):1450–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tommila V, Tarkkanen A. Incidence of loss of vision in the healthy eye in amblyopia. Br J Ophthalmol 1981;65(8):575–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu F, Cole JA, Ramanathan S. Fellow eye status in monocular patients in an academic optometry and ophthalmology practice | IOVS | ARVO Journals. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2020;61(7). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hale JE, Murjaneh S, Frost NA, Harrad RA. How should we manage an amblyopic patient with cataract? Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90(2):132–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pennington KL, DeAngelis MM. Epidemiology of age-related macular degeneration (AMD): Associations with cardiovascular disease phenotypes and lipid factors. Eye Vis (Lond) 2016;3:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on Public Health Approaches to Reduce Vision Impairment and Promote Eye Health; Welp A, Woodbury RB, McCoy MA, et al. , editors. The Impact of Vision Loss. September 15, 2016. [cited March 14, 2021]; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK402367/

- 10. White SLJ, Wood JM, Black AA, Hopkins S. Vision screening outcomes of Grade 3 children in Australia: Differences in academic achievement. Int J Educ Res. 2017;83:154–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang MY, Rousseau J, Boisjoly H, et al. Activity limitation due to a fear of falling in older adults with eye disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53(13):7967–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Solebo AL, Rahi JS. Vision screening in children: Why and how? Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2014;21(4):207–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Williams C, Northstone K, Harrad RA, Sparrow JM, Harvey I; ALSPAC Study Team . Amblyopia treatment outcomes after screening before or at age 3 years: Follow up from randomised trial. BMJ 2002;324(7353):1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zimmerman DR, Ben-Eli H, Moore B, Toledano M, Stein-Zamir C, Gordon-Shaag A. Evidence-based preschool-age vision screening: Health policy considerations. Isr J Health Policy Res 2019;8(1):70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kvarnström, P, Jakobsson, G G. Screening for visual and ocular disorders in children, evaluation of the system in Sweden. Acta Paediatrica. 1998;87(11):1173–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Amit M, Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS), Community Paediatrics Committee . Vision screening in infants children and youth. Paediatrics and Child Health. 2009;14(4):246–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cost of Vision Loss in Canada: Summary Report. Toronto; 2009. [cited March 14, 2021]. Available from: http://vision2020canada.ca/en/resources/Study/COVL%20Summary%20Report%20EN.PDF

- 18. Sabri K, Easterbrook B, Khosla N, Davis C, Farrokhyar F. Paediatric vision screening by non-healthcare volunteers: Evidence based practices. BMC Med Educ 2019;19(1):65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schmucker C, Grosselfinger R, Riemsma R, et al. Effectiveness of screening preschool children for amblyopia: A systematic review. BMC Ophthalmol 2009;9:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mema SC, McIntyre L, Musto R. Childhood vision screening in Canada: Public health evidence and practice. Can J Public Health. 2012;103:40–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Vision screening in children aged 6 months to 5 years: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 2017;318:836–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shakarchi AF, Collins ME. Referral to community care from school-based eye care programs in the United States. Surv Ophthalmol 2019;64(6):858–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chief Medical Officer of Health. Child Visual Health and Vision Screening Protocol, 2018. Toronto; 2018. [cited June 23, 2019]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/docs/protocols_guidelines/Child_Visual_Health_and_Vision_Screening_Protocol_2018_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24. Canadian Association of Optometrists. Position Statement: Comprehensive Vision Examination of Preschool Children.2014. [cited September 29, 2020]. p. 1–3. Available from: https://opto.ca/sites/default/files/resources/documents/cao_position_statement_-_comprehensive_vision_examination_of_preschool_children_en_2015.pdf

- 25. Vision Loss in Canada 2011. Canadian Ophthalmological Society. http://www.cos-sco.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/VisionLossinCanada_e.pdf.2010;

- 26. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. ; REDCap Consortium . The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bennett KP, Maloney W. Weighing in on Canadian school-based vision screening: A call for action. Can J Public Health 2017;108(4):e421–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. BC Doctors of Optometry. Children’s Vision Resources.2020. [cited September 30, 2020]. Available from: https://bc.doctorsofoptometry.ca/patients/children/

- 30. Alberta Association of Optometrists. Children’s Vision and Eye Health. [cited September 30, 2020]. Available from: http://www.optometrists.ab.ca/web/AAO/Patients/Childrens_Vision_and_Eye_Health/Children’s_Vision_and_Eye_Health.aspx

- 31. Saskatchewan Association of Optometrists. Eye See…Eye LearnTM – Saskatchewan Association of Optometrists. [cited September 30, 2020]. Available from: https://optometrists.sk.ca/childrens-vision-esel/

- 32. Manitoba Association of Optometrists. Eye See...Eye Learn®. [cited September 30, 2020]. Available from: https://www.optometrists.mb.ca/patients/childrens-vision/eye-see-eye-learn

- 33. Ontario Association of Optometrists. Eye See...Eye Learn. [cited September 30, 2020]. Available from: https://www.optom.on.ca/OAO/ESEL/OAO/ESEL/Eye_See...Eye_Learn.aspx?hkey=8b82d150-0cc6-433b-aa15-9aa5180dfb41

- 34. Nova Scotia Association of Optometrists. Initiatives.2020. [cited September 30, 2020]. Available from: https://www.nsoptometrists.ca/site/initiatives

- 35. Catano J. A Healthy Start to School.Halifax; 2012. [cited September 30, 2020]. Available from: https://novascotia.ca/dhw/healthy-development/documents/A-Healthy-Start-to-School.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 36. Prince Edward Island Association of Optometrists. Eye See…Eye Learn®. [cited September 30, 2020]. Available from: https://peioptometrists.ca/eye-see-eye-learn-program/

- 37. NL Association of Optometrists. [cited September 30, 2020]. Available from: https://nlao.org/

- 38. Fondation des maladies de l’oeil. Programme Jeunesse Participe Pour Voir.Fondation des maladies de l’oeil; [cited September 29, 2020]. Available from: https://www.fondationdesmaladiesdeloeil.org/fr/programme-jeunesse-participe-pour-voir.php [Google Scholar]

- 39. Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec (RAMQ). Optometric Services.2020. [cited September 29, 2020]. Available from: https://www.ramq.gouv.qc.ca/en/citizens/health-insurance/optometric-services

- 40. Government of New Brunswick. Healthy Smiles, Clear Vision – Vision Benefit for Four Year Olds. [cited September 29, 2020]. Available from: https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/corporate/promo/4yr_visionbenefit.html

- 41. Government of Canada. Vision care benefits.2020. [cited September 29, 2020]. Available from: https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1574179499096/1574179544527

- 42. Yellowknife Morale and Welfare Services. Vision Services. [cited September 30, 2020]. Available from: https://www.cafconnection.ca/Yellowknife/Adults/Health/Yellowknife-Medical-Services/Vision-Services.aspx

- 43. Sabri K, Thornley P, Waltho D, et al. Assessing accuracy of non–eye care professionals as trainee vision screeners for children. Can J Ophthalmol. 2016;51(1):25–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. History - École de la Vue. 2021. [cited March 15, 2021]. Available from: https://lecoledelavue.ca/en/historical

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.