Abstract

Purpose

The study aimed to investigate imaging abnormalities associated with post-acute COVID-19 using F-18 FDG PET/CT and PET/ rsfMRI brain.

Methods

We retrospectively recruited 13 patients with post-acute COVID-19. The post-acute COVID-19 symptoms and neuropsychiatric tests were performed before F-18 FDG PET/CT whole body with PET/rsfMRI brain. Qualitative and semiquantitative analyses were also conducted in both whole body and brain images.

Results

Among the 13 patients, 8 (61.5%) had myositis, followed by 8 (61.5%) with vasculitis (mainly in the thoracic aorta), and 7 (53.8%) with lung abnormalities.. Interestingly, one patient with a very high serum RBD IgG antibody demonstrated diffuse myositis throughout the body which potentially associated with immune-mediated myositis. One patient experienced psoriasis exacerbation with autoimmune-mediated after COVID-19. Most patients had multiple areas of abnormal brain connectivity involving the frontal and parieto-temporo-occipital lobes, as well as the thalamus.

Conclusion

The whole body F-18 FDG PET can be a potential tool to assess inflammatory process and support the hyperinflammatory etiology, mainly for lesions in skeletal muscle, vascular wall, and lung, as well as, multiple brain abnormalities in post-acute COVID-19. Nonetheless, further studies are recommended to confirm the results.

Keywords: Post-acute COVID-19, Long COVID-19, Inflammation, F-18 FDG PET, Fluorodeoxyglucose, Resting-state functional MRI

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) was declared as a pandemic disease by the World Health Organization in March 2020 [1]. Post-acute COVID-19 refers to a group of various abnormal symptoms in multiple organs that persist for more than 28 days after the first onset of SARS-CoV-2 symptoms, e.g., fatigue, muscular weakness, dyspnea, sleep disturbance, cognitive disturbance (brain fog), headaches, palpitation, chest pain, thromboembolism [2]. Between 32 and 87% of patients with COVID-19 experienced at least one symptom of post-acute COVID-19 [2–10]. The etiology of post-acute COVID-19 remains unclear. Recently, some study raised the hypothesis including hyperinflammation caused by autoantibodies and persistent SARS-CoV-2 virus in the body [11].

F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is a glucose analog used for positron emission tomography (PET), with the degree of FDG uptake related to cellular metabolic rate and number of glucose transporter. Inflammatory process increases inflammatory cytokines and activates inflammatory cells for high level of glucose transporter expression [12]. Thus, F-18 FDG PET can detect such inflammatory process throughout the body. Additionally, brain parenchyma mainly uses glucose metabolism for neuronal function, so the alteraltion in glucose metabolism also reflects synaptic dysfunctions within the brain [13, 14]. According to the hypothesis of inflammatory etiology of post-acute COVID-19, F-18 FDG PET might be helpful for evaluating abnormalities of the whole body and brain. Nonetheless, only few studies using the whole body F-18 FDG PET/CT in patients with post-acute COVID-19 reported abnormalities mainly in multiple areas, such as lung, bone marrow, vascular wall, and joints compared with healthy control groups [15, 16]. Whereas, some of those studies of brain abnormalities in post-acute COVID-19 patients yielded hypometabolism in multiple brain parenchyma areas, including frontal, parietal, temporal, thalamus, cerebellar vermis, and brain stem [14, 15, 17–19]. From our review, F-18 FDG PET study might be a potential tool to detect abnormality in the whole body and brain in post-acute COVID-19 patients. However, studies of F-18 FDG PET for evaluation in post-acute COVID-19 patients are still limited. This study aimed to investigate imaging abnormalities associated with post-acute COVID-19 using F-18 FDG PET/CT and PET/resting state functional MRI brain.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This retrospective study was conducted between August 2021 and September 2021. All patients with a history of COVID-19 (confirmed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for SARS-CoV-2) with persistent abnormal symptoms more than 28 days after the first onset of SARS-CoV-2 symptoms, e.g., post viral fatigue, cognitive impairment, shortness of breath, were requested PET study by a clinician. Patients younger than 20 years old, patients with disabilities, those with a history of cancer, and pregnant or lactating women were excluded from this study. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Chulabhorn Research Institute. However, the informed consent of patient was waived due to our retrospective design. Baseline patient data were collected including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), history of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, the severity of COVID-19, symptoms of post-acute COVID-19, serum anti-receptor binding domain (RBD) IgG antibody, and the time interval between the first detection of SARS-CoV-2 and F-18 FDG PET study. The severity of COVID-19 was classified as follow: asymptomatic/mild illness, positive SARS-CoV-2 test with no or mild symptoms (e.g., fever cough, or change in taste or smell) without dyspnea; moderate, clinical, or chest film evidence of lower respiratory tract disease with oxygen saturation more than 94%; severe, oxygen saturation less than 94%, a respiratory rate more than 30 breaths/min, or lung infiltration more than 50%; and critical, evidence of respiratory failure, shock, or multiorgan dysfunction [20]. Test for post-acute COVID-19 and the following neuropsychiatric tests were administered before F-18 FDG PET imaging: Newcastle Post-COVID Syndrome Follow-up Screening Questionnaire, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

F-18 FDG PET/CT Whole Body

F-18 FDG PET data were obtained after intravenous injection of 2.59 MBq/kg of F-18 FDG. Whole body PET/CT was performed on a 64-slice Siemens/Biograph Vision Scanner (Siemens Healthcare GmbH) about 90 min after radiotracer injection. CT imaging was performed from vertex to toe for attenuation correction and structural images. A three-dimensional (3D) emission scan of the same area was acquired with continuous bed motion over 17 min. The reconstruction parameters for attenuation correction were as follows: ultra-HD PET (point spread function + time of flight) with two iterations and five subsets, image size 440 × 440, all-pass filters, zoom factor of 1. PET data were used to be reconstructed into whole body static images.

F-18 FDG PET/Resting-State Functional MRI Brain (rsfMRI Brain)

F-18 FDG PET/rsfMRI brain imaging data were acquired about 40–50 min after injection (before F-18 FDG PET/CT study). Data were acquired using PET-MRI 3 Tesla (Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany) with single bed PET dynamic list-mode acquisition simultaneously with MRI acquisition using molecular head and neck coil (corrected attenuation correction coil). The DIXON high-resolution brain sequence with a voxel size of 1.3 × 1.3 × 2.0 mm, TE = 1.28/2.51 ms, TR = 4.14 ms, and five compartment segmentations (air, water, lung adaptive, bone) postprocessing method was applied for magnetic resonance-based attenuation correction (MRAC). MRI sequences included sagittal high-resolution three-dimensional T1-weighted images with weighted multiplanar gradient recall (T1-3D MPREG), axial diffusion weight image (DWI) with b0 and b1000, axial T2-weighted-fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) with fat suppression, coronal T2-weighted imaging, axial susceptibility-weighted image (SWI), resting-state functional MRI, diffusion tensor image (DTI), and axial T1 MPREG. PET data were reconstructed using the following parameters: ordered subset expectation maximization plus point spread function (OSEM + PSF of HD-PET) with six iterations and 21 subsets, matrix size = 512 × 512, zoom = 2, and all-pass filter.

Image Analysis

F-18 FDG PET/CT Whole Body Analysis

Visual Analysis

F-18 FDG whole body analysis was interpreted by two experienced nuclear medicine physicians using Syngovia Dicom viewer software (Siemens Healthineers, Munich, Germany). Any abnormal focus of increased F-18 FDG uptake that was not associated with physiologic uptake was considered as a positive lesion. For vascular lesion, visual grading score was used as follow: 0 = no uptake (≤ mediastinum), 1 = low-grade uptake (< liver), 2 = intermediate-grade uptake (= liver), 3 = high-grade uptake (> liver). A score of 2 or more was considered to represent vasculitis [21].

Semiquantitative Analysis

The maximal standardized uptake value (SUVmax) in each lesion was achieved using the volume of interest (VOI) drawn by nuclear medicine physicians in areas with highest radiotracer activity. The VOI in each lesion was adjusted manually to avoid a false positive from normal physiologic uptake. The background mean SUV, using automated AI from Syngovia Dicon Viewer software with VOI size 3 cm in diameter, was acquired at liver parenchyma, inferior vena cava (IVC), and jugular vein. Several 2D-axial ROIs were drawn on the jugular vein and IVC (eight ROI per each background) for obtaining average SUVmean in each venous background [22]. Target-to-background ratio (TBR) was calculated compared with each background regions.

F-18 FDG PET/rsfMRI Brain Analysis

During F-18 FDG PET brain analysis, brain images were displayed in orthogonal planes. Visual assessments were interpreted by two experienced nuclear medicine physicians using Syngovia Dicom Viewer software. Any abnormal decreased FDG uptake within the brain parenchyma was considered a positive lesion.

For rsfMRI, data were processed using a connectomic diagram analysis from Infinitome (Omniscient Neurotechnology, Sydney, Australia). The axial T1 3D MPREG high-resolution anatomical data coupled with DTI images were analyzed for highly accurate brain parcellation. Subsequently, a brain connectivity matrix was generated by comparison of each patient’s functional connectivity to that of 300 healthy control DTI and rsfMRI datasets. Finally, the functional connectivity diagram was rendered into a 3D image; structural and functional abnormalities were analyzed within specific brain regions according to metabolic imaging.

Statistical Analysis

Qualitative variables were reported as number and percentage. Normally distributed quantitative variables were reported as means ± standard deviations (SD), and non-normally distributed quantitative variables were reported as median and interquartile ranges (IQR).

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 13 patients were enrolled in this study (six men and seven women) with a median (IQR) age was 47 (42–54) years, and median (IQR) BMI was 21.1 (20–27.7) kg/m2. Six patients (46.15%) had not received any SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Nine patients (69.2%) had mild COVID-19, two patients (15.4%) had moderate COVID-19, and two patients (15.4%) had severe COVID-19. Among the seven patients who had received SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, six had mild COVID-19 and one had severe COVID-19. Among six patients who had not received any SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, three had mild COVID-19, two had moderate COVID-19, and one had severe COVID-19.

The three most common symptoms of post-acute COVID-19 were fatigue/myalgia (11 patients, 84.6%), sleep disturbance (8 patients, 61.5%), and cough/shortness of breath (7 patients, 53.8%). Neurocognitive and neuropsychiatric tests showed that six patients (46.1%) had mild cognitive impairment (MCI), four (30.7%) had anxiety, and four (30.7%) had depression. Only 11 patients had recent serum anti-receptor binding domain (RBD) IgG antibody data with median (IQR) time between from first onset SARS-CoV-2 symptom and antibody testing of 30 (28–33.5) days. Three patients had very high serum anti-receptor binding domain (RBD) IgG antibody titer of more than 1000 U/mL; however, two had a history of recent SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. The F-18 FDG PET was performed at a median time of 32 days (range: 28–91 days) after the first detection of SARS-CoV-2. In two patients, F-18 FDG PET was performed approximately 3 months after first detection of SARS-CoV-2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristic of patients with post-acute COVID-19

| Case | Age (year) | Sex | BMI | Comorbidity | SARS-CoV-2 vaccine | COVID-19 severity | Post-acute COVID-19 symptoms | Time between date of PCR SARS-CoV-2 detected and antibody testing (day) | Anti-RBD IgG antibody (BAU/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54 | F | 21 | GD in euthyroid state | 1st ChAdOx-2 | Mild |

- Severe generalized myalgia - Sleep disturbance |

14 | 11,035 |

| 2 | 54 | M | 24.9 |

HTN DLP |

1st ChAdOx-2 | Mild |

- Sensorineural hearing loss at left ear - Chronic hoarseness - Sleep disturbance |

30 | 27 |

| 3 | 66 | F | 22.9 |

HTN DLP |

None | Mild |

- Myalgia - Dyspnea - Dysgeusia - Weight loss - Sympathetic overactivity - MCI (MoCA 21) - Bacterial pneumonia on the 14th day* |

32 | 171 |

| 4 | 46 | F | 28.1 |

DM HTN CKD |

1st BBIBP-CorV | Severe |

- Fatigue and weakness - Cough and dyspnea - Myocarditis with heart failure - Palpitation - Negative mood - Sleep disturbance - Weight loss - MCI (MoCA 20) - Mild anxiety (HADS 10) - Bacterial pneumonia on the 36th day* |

N/A | N/A |

| 5 | 42 | F | 21.1 | Asthma | 2nd Coronavac | Mild |

- Brain fog - Fatigue - Dyspnea - Negative mood - Nightmare & sleep disturbance - Weight loss - Moderate depression (HADS 14) - Moderate anxiety (HADS 14) |

N/A | N/A |

| 6 | 45 | F | 20.0 | None | 1st BBIBP-CorV | Mild |

- Cough and dyspnea - Fatigue and myalgia - Anosmia - Dysgeusia - Sleep disturbance |

14 | 178.5 |

| 7 | 35 | M | 17.1 | None | None | Mild |

- Dyspnea - Fatigue and myalgia - Tension headache - MCI (MoCA 20) |

29 | 26.26 |

| 8 | 30 | F | 18.6 | None | None | Mild |

- Cough - Sleep disturbance - Negative mood - Binge eating syndrome with excessive weight gain |

30 | 3 |

| 9 | 55 | M | 27.7 |

DM HTN |

None | Moderate |

- Fatigue - Proximal muscle weakness - Palpitations - Negative mood - Weight loss - Dysosmia - Dysgeusia - MCI (MoCA 20) - Mild depression (HADS 10) - Mild anxiety (HADS 8) |

27 | 104.5 |

| 10 | 62 | M | 15.8 |

HTN DLP |

None | Severe |

- Fatigue and myalgia - Cough - Palpitation - Sleep disturbance - Weight loss - MCI (MoCA 19) |

32 | 303.7 |

| 11 | 47 | M | 32 |

DM HTN SLE (inactive) |

None | Moderate |

- Fatigue and myalgia - Palpitation - Negative mood - Axonal polyneuropathy - Attention deficit - Mild depression (HADS 7) |

35 | 260 |

| 12 | 36 | F | 21.1 | HTN | 2nd ChAdOx-2 (after COVID-19) | Mild |

- Fatigue - Palpitation - Decreased appetite - Sleep disturbance and nightmare - Negative mood - Moderate anxiety (HADS 12) - Mild depression (HADS 10) - MCI (MoCA 20) |

84 (17 days after 2nd SARS-CoV-2 vaccination) |

1,720 |

| 13 | 54 | M | 28.6 |

Psoriasis DM Gout |

2nd ChAdOx-2 (after COVID-19) | Mild |

- Fatigue - Weakness - Telogen effluvium - Psoriasis exacerbation |

91 (13 days after 2nd SARS-CoV-2 vaccination) |

5,484 |

N/Anot available, GD in RMGraves’ disease in remission, HTN hypertension, DLP dyslipidemia, CKD chronic kidney disease, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus, MCI mild cognitive impairment, MoCA Montreal Cognitive Assessment, HADSHospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, BAU binding antibody unit

*Complication after COVID−19

Whole Body F-18 FDG PET/CT

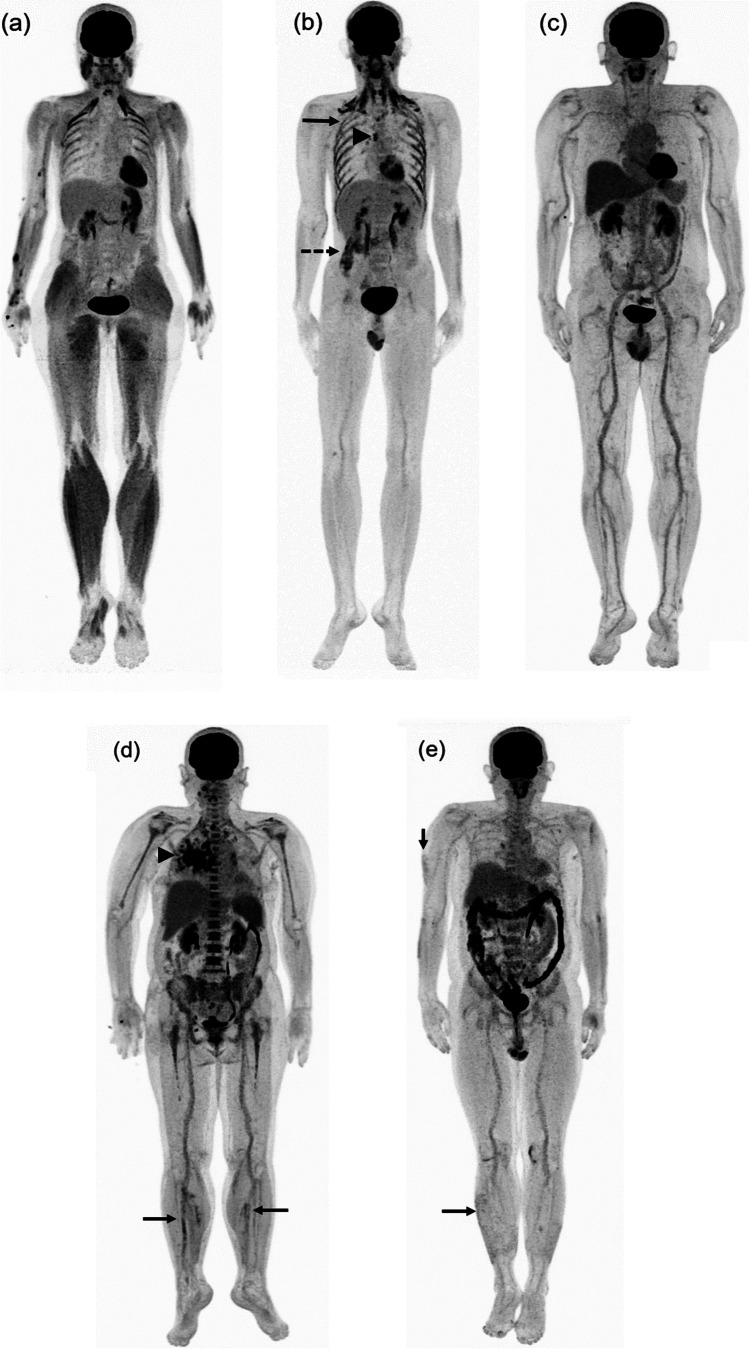

Whole body analysis revealed F-18 FDG uptake in the lymph nodes (12 patients, 92.3%), skeletal muscle (8 patients, 61.5%), vascular wall (8 patients, 61.5%), lung (7 patients, 53.8%), spleen (2 patients, 15.4%), bone marrow (1 patient, 7.7%), thyroid (1 patient, 7.7%), soft tissue at chin (1 patient, 7.7%), and skin (1 patient, 7.7%) (Table 2). During quantitative analysis, the mean and standard deviation of background SUVmean of the liver, inferior vena cava, and jugular vein were 2.25 ± 0.51, 1.38 ± 0.26, and 1.29 ± 0.29, respectively. The median and IQR of SUVmax and TBR for all background regions are shown in Table 3. Among eight patients with skeletal muscle uptake, we observed non-specific patterns of F-18 FDG uptake (Fig. 1a–b). However, one patient with markedly high serum anti-receptor binding domain (RBD) IgG antibody had diffuse increased F-18 FDG skeletal muscle uptake throughout the body (Fig. 1a). Among eight patients with vascular uptake, increased F-18 FDG uptake was commonly found at the thoracic aorta (six of eight patients, Fig. 2a–c) although one patient had diffused vascular uptake (Figs. 1c and 2a). Two patients with history of bacterial pneumonia showed intense F-18 FDG uptake in the lung parenchyma, adjacent lymph nodes, spleen, and bone marrow (Fig. 1d). One patient had psoriasis exacerbation following COVID-19 and F-18 FDG PET showed multiple areas of skin uptake compatible with worsening skin lesion (Fig. 1e).

Table 2.

F-18 FDG PET/CT and PET/rsfMRI brain imaging findings in patients with post-acute COVID-19

| Case | Time between first detected SARS-CoV-2 and F18-FDG PET (day) | F-18 FDG PET/CT | F-18 FDG PET/rsfMRI brain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | Lymph nodes | Muscle | Vascular wall | Other | |||

| 1 | 30 | No | Yes | Yes (diffused) | Yes | No | Right parietal |

| 2 | 30 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes (diffused) | No | Left temporal |

| 3 | 32 | Yes* | Yes | No | Yes | Spleen | Bilateral medial frontal, bilateral parieto-temporal |

| 4 | 36 | Yes* | Yes | Yes | Yes | Spleen, bone marrow (diffused), and right thyroid nodule | N/A** |

| 5 | 44 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Soft tissue at chin | Bilateral parieto-temporal, bilateral thalamus |

| 6 | 31 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Bilateral parieto-temporo-occipital |

| 7 | 32 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Bilateral medial frontal, bilateral parieto-temporo-occipital |

| 8 | 31 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Bilateral medial frontal, bilateral parieto-temporo-occipital |

| 9 | 28 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Bilateral parieto-temporal |

| 10 | 33 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Bilateral frontal, bilateral parieto-temporo-occipital |

| 11 | 36 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Bilateral frontal, bilateral parieto-temporo-occipital |

| 12 | 85 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Bilateral parieto-temporal |

| 13 | 91 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Skin | Bilateral medial frontal, bilateral parieto-temporo-occipital |

*Bacterial pneumonia after COVID−19

**Brain study cannot be acquired due to patient condition

Table 3.

Quantitative results of F-18 FDG PET/CT in patients with post-acute COVID-19

| An |

n (case) |

n (lesion) |

Median (IQR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUVmax | TBRliver | TBRcaval | TBRjugular | |||

| Muscle | 8 | 25 | 3.06 (2.24–4.49) | 1.68 (1.2–2.62) | 2.37 (1.84–3.62) | 2.96 (2.08–4.04) |

| Vascular wall | 8 | 16 | 3.42 (2.93–3.79) | 1.32 (1.15–1.57) | 1.99 (1.81–2.41) | 2.05 (1.80–2.80) |

| Lymph node | 12 | 21 | 4.55 (3.40–7.55) | 1.93 (1.52–2.99) | 2.90 (2.36–5.13) | 3.58 (2.67–5.89) |

| Lung | 7 | 8 | 4.45 (2.33–10.05) | 1.65 (1.08–4.77) | 3.06 (1.79–7.04) | 2.99 (1.85–8.79) |

| Spleen | 2 | 2 | 5.08 (5.06–5.09) | 1.86 (1.82–1.91) | 3.03 (2.98–3.08) | 3.46 (3.21–3.72) |

| Skin | 1 | 6 | 2.16 (1.95–2.39) | 0.86 (0.78–0.95) | 1.37 (1.23–1.51) | 1.44 (1.30–1.59) |

| Bone marrow | 1 | 1 | 6.97 | 2.42 | 3.98 | 4.03 |

| Thyroid | 1 | 1 | 17.14 | 5.95 | 9.79 | 9.97 |

| Soft tissue at chin | 1 | 1 | 10.05 | 4.21 | 7.34 | 6.57 |

SUVmaxmaximal standardized uptake value, TBRtarget−to−background ratio

Fig. 1.

Maximal intensity projection F-18 FDG PET images of patients with post-acute COVID-19. (a) Case 1: diffuse hypermetabolism of the skeletal muscle throughout the body (arrow). (b) Case 7: multiple hypermetabolism at respiratory muscle (arrow) and quadratus lumbrolum muscle (dot arrow) with hypermetabolic node at right hilar region (arrow head). (c) Case 2: diffuse hypermetabolism along the vascular wall throughout the body. (d) Case 4 with bacterial pneumonia: focal hypermetabolism along the vascular walls of bilateral popliteal vessels (arrow) with focal hypermetabolism in the right lung (arrowhead) and diffuse bone marrow and splenic uptake. (e) Case 13 with psoriasis exacerbation: multiple hypermetabolic skin lesions (arrow). Abbreviation: FDG fluorodeoxyglucose, PET positron emission tomography, COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019

Fig. 2.

Coronal F-18 FDG PET images in patients with post-acute COVID-19. (a–c) Diffuse hypermetabolism was observed along the vascular wall of the thoracic aorta (dot arrows) with hypermetabolism at the bilateral carotid arteries (arrows). Abbreviation: FDG fluorodeoxyglucose, PET positron emission tomography, COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019

F-18 FDG PET/rsfMRI Brain

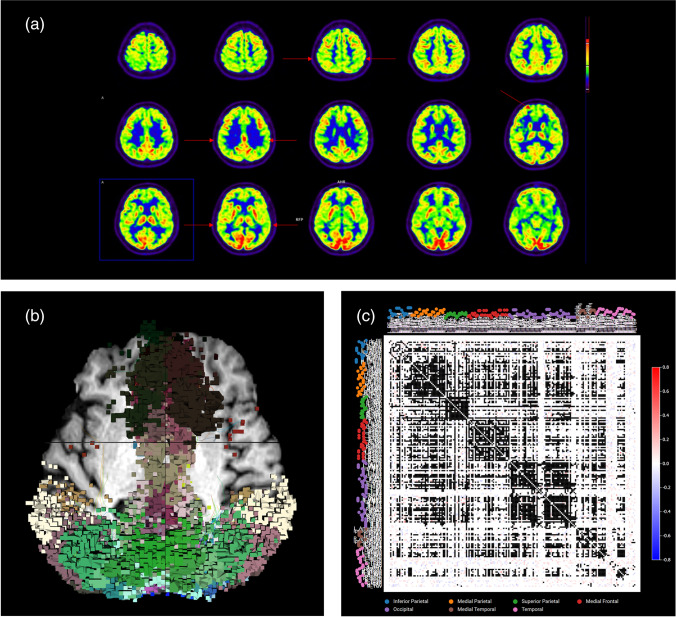

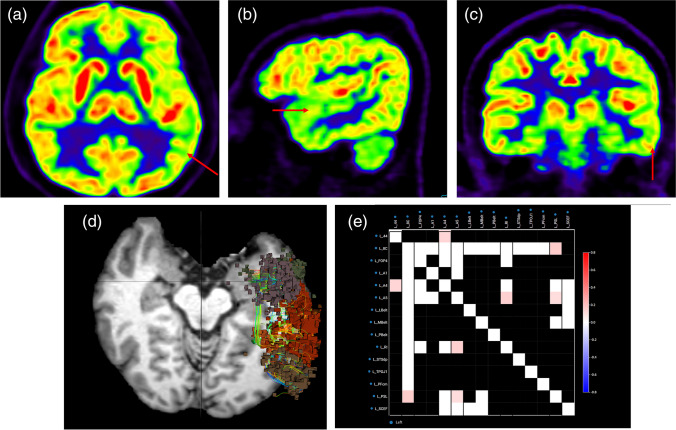

Brain analysis could not be performed for one patient because of medical condition. Most patients had various neurological symptoms including fatigue/myalgia, negative mood, depression, anxiety, MCI, and loss of taste and smell. F-18 FDG PET showed multiple areas of hypometabolism in the parietal lobe (11 patients, 91.7%), temporal lobe (11 patients, 91.7%), frontal lobe (5 patients, 41.7%), occipital lobe (5 patients, 41.7%), and thalamus (1 patient, 8.3%) (Fig. 3a). rsfMRI could not be performed in one patient because of a metallic artifact. The rsfMRI results showed abnormal brain connectivity which is concordant with F-18 FDG PET results (Fig. 3b–c). One patient had sensorineural hearing loss of the left ear, and F-18 FDG PET showed hypometabolism of the left temporal region (Fig. 4a–c) as well as abnormality in the same region shown on the rsfMRI results (Fig. 4d–e).

Fig. 3.

Brain imaging analysis in case 13. (a) F-18 FDG PET axial images showed multiple hypometabolism in the bilateral medial frontal, bilateral parieto-temporal, and bilateral lateral occipital lobes (arrow). (b) Functional connectomic activity axial images from rsfMRI brain showed abnormal brain connectivity in the same regions as the F-18 FDG PET images. (c) Connectivity matrix images from rsfMRI brain also showed multiple abnormal brain connectivity in these regions. Abbreviation: COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, FDG fluorodeoxyglucose, PET positron emission tomography, rsfMRI resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging

Fig. 4.

Brain imaging analysis in a Case 2 with sensorineural hearing loss of left ear. (a–c) F-18 FDG PET axial, sagittal, and coronal images showing hypometabolism in the left temporal lobe (arrow). (d) Functional connectomic activity axial images from rsfMRI brain showed abnormal brain connectivity in the left temporal lobe. (e) Connectivity matrix images from rsfMRI brain also showed abnormal brain connectivity in multiple areas of the left temporal lobe. Abbreviation: COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, FDG fluorodeoxyglucose, PET positron emission tomography, rsfMRI resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we found increased F-18 FDG uptake in multiple organs of patients with post-acute COVID-19, reflecting inflammatory processes. Our results agree with those of Sollini et al. [15] and support multiple organ involvement in post-acute COVID-19. Skeletal muscle uptake of F-18 FDG was observed up to 61.5% of patients, although the extent of muscle involvement during SARS-CoV-2 infection remains unclear. Some studies have proposed hematogenous spreading and direct invasion of skeletal muscle by SARS-CoV-2, while others have suggested that muscle involvement occurs secondary to inflammatory responses from cytokine storms and activation of immune cells [23]. A post-mortem case–control study of severe COVID-19 found that patients had signs of myositis ranging from mild to severe despite low or negative viral loads, supporting the hypothesis of immune-mediated myopathy [24]. In our study, one patient had very serum anti-receptor binding domain (RBD) IgG antibody titer (11,035 U/mL) and showed diffuse increased F-18 FDG uptake in the skeletal muscle throughout the body (Fig. 1a). Thus, there may be an association between myositis and serum anti-receptor binding domain (RBD) IgG antibody titer.

Sollini et al. [16] studied 10 patients with long-COVID-19 compared with healthy controls. Six of 10 patients had increased F-18 FDG uptake in blood vessels. Additionally, quantitative target-to-blood pool ratios were significantly higher in patients compared with controls in the thoracic aorta, right iliac artery, and femoral arteries. In our study, we observed vasculitis in eight patients (61.5%), including diffuse vasculitis in one patient and increased F-18 FDG uptake in the thoracic aorta. During COVID-19, various types of vasculopathy can occur following inflammation triggered in response to the virus from inflammatory mediators, leading to endothelial damage, vascular dysfunction, and thrombosis [25]. Despite the unknown pathophysiology of vasculitis in post-acute COVID-19, we speculate that the etiology might be associated with autoantibodies. Further data are required to test this hypothesis.

Seven patients had different levels of F-18 FDG uptake in lung parenchyma. SARS-CoV-2 virus mainly caused viral pneumonia with intense F-18 FDG uptake during the infectious process. However, persistent F-18 FDG uptake in the lung parenchyma could be observed even the improvement of clinical symptoms and CT finding, while F-18 FDG uptake remained unknown on the exact time period for resolution [26, 27]. Persistent intense F-18 FDG uptake in lung parenchyma even at the recovery stage might potentially indicate a high level of inflammatory process for prediction of further damages to lung parenchyma [27].

One patient with post-acute COVID-19 had underlying psoriasis that was inactive for many years. However, following COVID-19, the patient’s psoriasis became worsened, and he developed skin lesions throughout the body. F-18 FDG PET also showed multiple hypermetabolic skin lesions associated with psoriasis. Recent studies [28, 29] showed that COVID-19 may be associated with autoimmune diseases such as Guillain- Barré syndrome, Kawasaki-like syndrome, and anti-phospholipid syndrome. Thus, COVID-19 might also have triggered psoriasis exacerbation in this patient.

F-18 FDG uptake in lymph nodes was observed in most of our patients during the inflammatory process. This then reflected the immunoreaction activated by inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils, monocytes, and T-cells. COVID-19 could also activate immune responses with increased number of monocytes in lymphoid tissues, causing an increased F-18 FDG uptake in lymph nodes [27]. Diffused bone marrow and splenic uptake were only obtained in patients with a history of bacterial on top pneumonia (Fig. 1c), which could potentially be a result from bacteremia [30]. We detected a hypermetabolic thyroid nodule in one patient, with reviewed incidence of about 8.4% [31]. However, there was a risk of 30% for malignancy in this nodule. Neck ultrasound or FNA should be thus further investigated. Additionally, one patient had hypermetabolic soft tissue lesion at chin which might also be incidental finding.

Brain imaging data were obtained using both F-18 FDG PET and rsfMRI brain. One patient has sensorineural hearing loss at the left ear. We observed abnormal brain connectivity in the left temporal region. The primary auditory cortex is found in the temporal lobe and plays a major role in the ability to perceive sounds; dominant function is found on the left side of the brain [32]. Thus, abnormal brain connectivity in the primary auditory cortex might explain the symptoms in this patient. Most patients had multiple neurological symptoms including fatigue/myalgia, depression, anxiety, MCI, negative mood, loss of taste, and smell. In these patients, we found multiple hypometabolic areas of the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes as well as in the thalamus, which is assumed as global abnormal brain connectivity. Our results are concordance with Blazhenets et al. [19], showing hypometabolism in multiple areas of the neocortex with frontoparietal predominance, but differed from Sollini et al. [15] and Guedj et al. [17] at multiple hypometabolic areas in the brain, such as right temporal lobe, orbitofrontal gyrus, right thalamus, bilateral pons/medulla, bilateral cerebellum, and parahippocampal gyrus. However, there are still limited data regarding the effects of post-acute COVID-19 on the brain. Furthermore, patients with COVID-19 might have neuropsychological sequelae following COVID-19 that could affect F-18 FDG PET results [13, 33, 34].

The pathophysiology of brain change in post-acute COVID-19 might be related to changes in brain parenchyma and blood brain barrier during SARS-CoV-2 infection, resulting in encephalitis; another mechanism might be associated with dysfunctional lymphatic drainage [2]. Even though post-acute COVID-19 is associated with various symptoms of neuropsychological and neurocognitive abnormalities, recent studies [35] showed that patients with cognitive impairment following COVID-19 had significant improvement in both clinical and F-18 FDG PET findings at 6-month follow-up compared with baseline.

Conclusion

The whole body F-18 FDG PET can be a potential tool for the assessment of inflammatory process and hyperinflammatory etiology with multiple organ involvement, particularly lesions in skeletal muscle, vascular wall, and lung, as well as, multiple brain abnormalities in post-acute COVID-19. Nonetheless, further studies in a larger sample size are recommended to elucidate and ratify the outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Edanz (https://www.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author Contribution

The study was designed by PK and CC. Material preparation and data collection were performed by PK and DS. The data analysis was performed by ST and AJ. The first draft of the manuscript was written by PK, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

Contact the corresponding author for data requests.

Declarations

Competing Interests

Peerapon Kiatkittikul, Chetsadaporn Promteangtrong, Anchisa Kunawudhi, Dheeratama Siripongsatian, Taweegrit Siripongboonsitti, Piyanuj Ruckpanich, Supachoke Thongdonpua, Attapon Jantarato, Chaiyawat Piboonvorawong, Nirawan Fonghoi, and Chanisa Chotipanich declare no competing interests.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This report was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Chulabhorn Research Institute in accordance with the Helsinki declaration.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Authors’ information

We are nuclear medicine physicians at National Cyclotron and PET Centre, Chulabhorn Hospital, Chulaborn Royal Academy, Bangkok, Thailand. A centre for diagnosis of cancer, neurological, and heart diseases through advanced technology (PET/MRI and PET/CT) as well as radionuclide treatment. The centre commits and strives for service continuous research and development in the many kinds of radiopharmaceutical.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19, https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020; 2020 Accessed 30 Sept 2021.

- 2.Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27:601–615. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F, for the Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324:603–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chopra V, Flanders SA, O’Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC. Sixty-day outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:576–578. doi: 10.7326/M20-5661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carvalho-Schneider C, Laurent E, Lemaignen A, Beaufils E, Bourbao-Tournois C, Laribi S, et al. Follow-up of adults with noncritical COVID-19 two months after symptom onset. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnold DT, Hamilton FW, Milne A, Morley AJ, Viner J, Attwood M, et al. Patient outcomes after hospitalisation with COVID-19 and implications for follow-up: Results from a prospective UK cohort. Thorax. 2021;76:399–401. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreno-Pérez O, Merino E, Leon-Ramirez J-M, Andres M, Ramos JM, Arenas-Jiménez J, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Incidence and risk factors: a Mediterranean cohort study. J Infect. 2021;82:378–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halpin SJ, McIvor C, Whyatt G, Adams A, Harvey O, McLean L, et al. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of COVID-19 infection: a cross-sectional evaluation. J Med Virol. 2021;93:1013–1022. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garrigues E, Janvier P, Kherabi Y, Bot AL, Hamon A, Gouze H, et al. Post-discharge persistent symptoms and health-related quality of life after hospitalization for COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;81:e4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crook H, Raza S, Nowell J, Young M, Edison P. Long COVID—mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374:n1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jamar F, Buscombe J, Chiti A, Christian PE, Delbeke D, Donohoe KJ, et al. EANM/SNMMI guideline for 18F-FDG use in inflammation and infection. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2013;54:647–658. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.112524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varrone A, Asenbaum S, Vander Borght T, Booij J, Nobili F, Någren K, et al. EANM procedure guidelines for PET brain imaging using [18F]FDG, version 2. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:2103–2110. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fontana IC, Bongarzone S, Gee A, Souza DO, Zimmer ER. PET imaging as a tool for assessing COVID-19 brain changes. Trends Neurosci. 2020;43:935–938. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2020.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sollini M, Morbelli S, Ciccarelli M, Cecconi M, Aghemo A, Morelli P, et al. Long COVID hallmarks on [18F]FDG-PET/CT: a case-control study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:3187–3197. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05294-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sollini M, Ciccarelli M, Cecconi M, Aghemo A, Morelli P, Gelardi F, et al. Vasculitis changes in COVID-19 survivors with persistent symptoms: an [18F]FDG-PET/CT study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:1460–1466. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05084-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guedj E, Campion JY, Dudouet P, Kaphan E, Bregeon F, Tissot-Dupont H, et al. 18F-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in patients with long COVID. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:2823–2833. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05215-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kas A, Soret M, Pyatigoskaya N, Habert M-O, Hesters A, Le Guennec L, et al. The cerebral network of COVID-19-related encephalopathy: a longitudinal voxel-based 18F-FDG-PET study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:2543–2557. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05178-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blazhenets G, Schröter N, Bormann T, Thurow J, Wagner D, Frings L, et al. Altered regional cerebral function and its association with cognitive impairment in COVID-19: A prospective FDG PET study. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:41–41. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.121.262128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, del Rio C. Mild or moderate COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1757–1766. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp2009249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slart RHJA. FDG-PET/CT(A) imaging in large vessel vasculitis and polymyalgia rheumatica: joint procedural recommendation of the EANM, SNMMI, and the PET Interest Group (PIG), and endorsed by the ASNC. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45:1250–1269. doi: 10.1007/s00259-018-3973-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Besson FL, de Boysson H, Parienti J-J, Bouvard G, Bienvenu B, Agostini D. Towards an optimal semiquantitative approach in giant cell arteritis: an 18F-FDG PET/CT case-control study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:155–166. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramani SL, Samet J, Franz CK, Hsieh C, Nguyen CV, Horbinski C, et al. Musculoskeletal involvement of COVID-19: review of imaging. Skeletal Radiol. 2021;50:1763–1773. doi: 10.1007/s00256-021-03734-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aschman T, Schneider J, Greuel S, Meinhardt J, Streit S, Goebel H-H, et al. Association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and immune-mediated myopathy in patients who have died. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:948–960. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker RC. COVID-19-associated vasculitis and vasculopathy. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50:499–511. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02230-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodríguez-Alfonso B, Ruiz Solís S, Silva-Hernández L, Pintos Pascual I, Aguado Ibáñez S, Salas AC. 18F-FDG-PET/CT in SARS-CoV-2 infection and its sequelae. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol (Engl Ed) 2021;40:299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.remnie.2021.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minamimoto R, Hotta M, Ishikane M, Inagaki T. FDG-PET/CT images of COVID-19: a comprehensive review. Glob Health Med. 2020;2:221–226. doi: 10.35772/ghm.2020.01056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novelli L, Motta F, De Santis M, Ansari AA, Gershwin ME, Selmi C. The JANUS of chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases onset during COVID-19—a systematic review of the literature. J Autoimmun. 2021;117:102592. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodríguez Y, Novelli L, Rojas M, De Santis M, Acosta-Ampudia Y, Monsalve DM, et al. Autoinflammatory and autoimmune conditions at the crossroad of COVID-19. J Autoimmun. 2020;114:102506. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pijl JP, Kwee TC, Slart RHJA, Yakar D, Wouthuyzen-Bakker M, Glaudemans AWJM. Clinical implications of increased uptake in bone marrow and spleen on FDG-PET in patients with bacteremia. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48:1467–1477. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05071-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bae JS, Chae BJ, Park WC, Kim JS, Kim SH, Jung SS, et al. Incidental thyroid lesions detected by FDG-PET/CT: prevalence and risk of thyroid cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:63. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-7-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devlin JT, Raley J, Tunbridge E, Lanary K, Floyer-Lea A, Narain C, et al. Functional asymmetry for auditory processing in human primary auditory cortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11516–11522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-37-11516.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engel K, Bandelow B, Gruber O, Wedekind D. Neuroimaging in anxiety disorders. J Neural Transm. 2009;116:703–716. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0077-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su L, Cai Y, Xu Y, Dutt A, Shi S, Bramon E. Cerebral metabolism in major depressive disorder: a voxel-based meta-analysis of positron emission tomography studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:321. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0321-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blazhenets G, Schröter N, Bormann T, Thurow J, Wagner D, Frings L, et al. Slow but evident recovery from neocortical dysfunction and cognitive impairment in a series of chronic COVID-19 patients. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:910–915. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.121.262128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Contact the corresponding author for data requests.