Abstract

Chloroplasts overproduce reactive oxygen species (ROS) under unfavorable environmental conditions, and these ROS are implicated in both signaling and oxidative damage. There is mounting evidence for their roles in translating environmental fluctuations into distinct physiological responses, but their targets, signaling cascades, and mutualism and antagonism with other stress signaling cascades and within ROS signaling remain poorly understood. Great efforts made in recent years have shed new light on chloroplast ROS-directed plant stress responses, from ROS perception to plant responses, in conditional mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana or under various stress conditions. Some articles have also reported the mechanisms underlying the complexity of ROS signaling pathways, with an emphasis on spatiotemporal regulation. ROS and oxidative modification of affected target proteins appear to induce retrograde signaling pathways to maintain chloroplast protein quality control and signaling at a whole-cell level using stress hormones. This review focuses on these seemingly interconnected chloroplast-to-nucleus retrograde signaling pathways initiated by ROS and ROS-modified target molecules. We also discuss future directions in chloroplast stress research to pave the way for discovering new signaling molecules and identifying intersectional signaling components that interact in multiple chloroplast signaling pathways.

Keywords: ROS, 1O2, H2O2, oxidation, operational retrograde signaling, proteostasis

Chloroplast-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) cause oxidative damage to macromolecules. However, oxidation-/damage-associated signaling pathways and their interplay with other signaling pathways remain largely unexplored. This review focuses mainly on chloroplast-mediated signaling pathways elicited by ROS and ROS-modified target molecules and discusses their potential interplay with other known stress-related signaling pathways.

Introduction

Oxygenic photosynthesis provides oxygen and food for most life forms through the use of sunlight, CO2, and water. Although oxygenic photosynthesis is a life-supporting process, inefficient utilization of sunlight yields harmful by-products, namely reactive oxygen species (ROS). Because only a minor portion of the absorbed photons (particles representing light quanta) are used to produce chemical energy in chloroplasts, excess photons must be safely dissipated (Apel and Hirt, 2004; Asada, 2006; Triantaphylides and Havaux, 2009; Kim and Apel, 2013; Khorobrykh et al., 2020). A combination of spontaneous and directed dissipation processes scatters the excess sunlight to some extent, but not entirely, inevitably producing ROS, especially under adverse environmental conditions. These excess ROS tend to oxidize macromolecules in their vicinity, thereby significantly damaging the structural and functional integrity of the chloroplast. In addition to being implicated in chloroplast damage, ROS are also involved in signaling that alerts other subcellular compartments to readjust whole-cell metabolic homeostasis and repair or turn over damaged macromolecules. Photorespiration and oxidative phosphorylation also lead to ROS production in peroxisomes and mitochondria, respectively. Thus, understanding ROS compartmentalization, crosstalk, and organelle-specific effects is crucial for understanding ROS-triggered plant stress responses.

During plastid acquisition by early eukaryotes, the plastid genome underwent significant reduction by endosymbiotic gene transfer to the host genome and by simple loss compared to its cyanobacterial ancestor (Timmis et al., 2004). Less than 5% of the original genes remain in the plastid genome, encoding mostly housekeeping and photosynthesis-associated proteins. As a result, the assembly of protein complexes in plastids necessitates, when required, the coordinated expression of nuclear and plastid genomes, referred to as genome-coupled expression (Chan et al., 2016a). This coordination is crucial for the punctual assembly of photosynthetic complexes during chloroplast biogenesis (e.g., during de-etiolation of dark-grown etiolated seedlings), which is critical for sustaining a photoautotrophic lifestyle. Likewise, dysfunctional plastids with attenuated transcription and translation require the equivalent repression of nuclear genes that encode cognate companions (Oelmuller and Mohr, 1986; Susek et al., 1993). All these related findings indicate that the functional status of the plastid is transmitted to the nucleus for genome-coupled expression, a process referred to as retrograde signaling. This process is further divided into biogenic and operational retrograde signaling (BRS and ORS) (Pogson et al., 2008; Kleine and Leister, 2016). Whereas BRS is critical for assembling chloroplast complexes during development, ORS is generally associated with stress and mainly directed by mature, photosynthesizing chloroplasts. The discovery of stress-associated ORS pathways has established chloroplasts as environmental sensors, translating perceived environmental stimuli as distinct forms of signals. Therefore, chloroplast signaling may make a significant contribution to cellular homeostasis and plant resilience upon exposure to stress. In addition to ROS, chloroplasts also produce other stress-related signaling molecules such as reactive carbonyl species, reactive nitrogen species (RNS), reactive sulfur species (RSS), volatile compounds, secondary metabolites, and precursors of stress hormones such as salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and abscisic acid (ABA). Shedding further light on how and when these signaling-associated molecules are synthesized under distinct stress conditions may provide essential clues to understanding the impact of chloroplast stress signaling on the broad spectrum of plant stress responses.

Chloroplast ROS: Production and oxidative damage

Chloroplasts produce ROS through both photosystems because of the excess photons trapped in photosystem (PSII) and the electron sink to molecular oxygen via photosystem I (PSI) (Apel and Hirt, 2004; Asada, 2006; Triantaphylides and Havaux, 2009). Excess energy in PSII leads to the formation of the triplet state of light-excited chlorophyll (3Chl) in the PSII light-harvesting antenna complex (LHC) and of P680 Chl molecules (3P680) in the reaction center (PSII RC) (Figure 1). Because of their increased lifespan, these 3Chl molecules can transfer the absorbed energy to ground-state oxygen (O2), facilitating the production of highly reactive singlet oxygen (1O2) (Figure 1). A group of carotenoids closely associated with the antenna complex can quench 3Chl and the 3Chl-produced 1O2, whereas PSII RC-generated 1O2 oxidizes β-carotene and D1 proteins (Dogra et al., 2018) (Figure 1). In PSII, 1O2 formation by energy transfer is well described, and the production of superoxide anion (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (OH•) by PSII has also been demonstrated (Pospisil et al., 2004; Pospisil, 2009, 2014, 2016). Electron leakage on the PSII electron acceptor side produces O2−, which undergoes dismutation to H2O2. H2O2 is then further converted to OH• by non-heme iron. On the PSII electron donor side, incomplete water oxidation results in the formation of H2O2, which is further reduced to OH• (Pospisil, 2016). The molecular basis for ROS production and the impact of ROS on target molecules in PSII provide new insight into the protection and repair of PSII. Interestingly, the phosphorylation and subsequent conformational changes of the D1 protein during PSII repair were found to be critical for inhibiting O2− production at the PSII acceptor side (Chen et al., 2012). Consistent with this finding, a rice STN8 kinase mutant defective in D1 phosphorylation exhibits elevated O2− levels upon exposure to high-light stress (Poudyal et al., 2016).

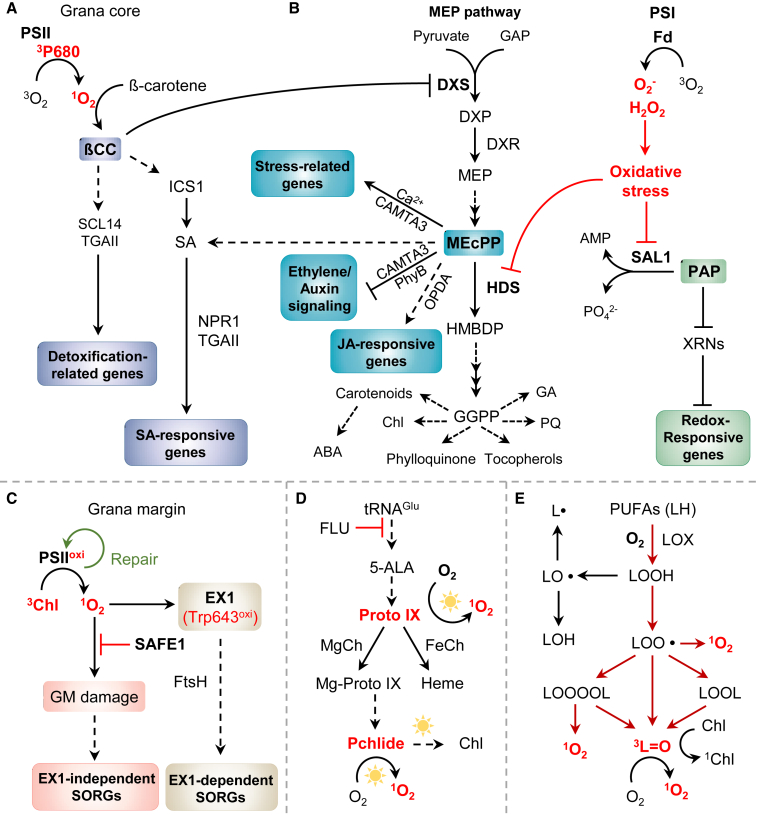

Figure 1.

ROS metabolism in the chloroplast.

The light energy captured in the photosystem II (PSII) light-harvesting antenna complex (LHC) drives photosynthetic electron transfer. Upon absorption of light energy, the chlorophyll (Chl) molecule converts to the singlet-state Chl (1Chl). Part of the excess energy is re-emitted as fluorescence or dissipated as heat, a process referred to as non-photochemical quenching (NPQ). Alternatively, the spontaneous decay of 1Chl results in triplet excited state 3Chl with an increased lifespan (Muller et al., 2001). 3Chl is quenched by carotenoids in the LHC, returning to its ground state. Otherwise, 3Chl transfers the absorbed energy to the ground state of O2, producing 1O2. The LHC-generated 1O2 can also be quenched by carotenoids. Energy that reaches the PSII RC Chl (P680) from the antenna complex also leads to the formation of 1O2 via 3P680 when the electron (e−) transfer chain becomes over-reduced. 1O2 then oxidizes β-carotene and D1 proteins in its vicinity. H2O2 and O2− can be generated through two-electron oxidations of H2O at the electron donor side of PSII and a one-electron reduction of O2 at the acceptor side of PSII, respectively. The subsequent conversion of H2O2 and O2− into other forms of ROS is described in Pospisil (2009). PSI is also involved in the production and detoxification process of O2− and H2O2. The photosystem I (PSI) electron acceptor ferredoxin (Fd)-NADP+ oxidoreductase (FNR) transfers electrons from ferredoxin to NADP+ to produce NADPH. NADPH and ATP produced by ATP synthase are used to produce glucose as the final product of photosynthesis via the Calvin–Benson cycle. To maintain PSII in a partly oxidized form under conditions in which the electron transfer chain becomes over-reduced, FNR transfers an electron to O2, thereby generating O2−. O2− is further converted into H2O2 by SUPEROXIDE DISMUTASEs (SODs). ASCORBATE PEROXIDASEs (APXs) then contribute to H2O2 scavenging through the ascorbate–glutathione cycle (Apel and Hirt, 2004). OH• is generated via the Fenton reaction by the interaction of H2O2 with reduced transition metal ions such as Fe2+ and Cu+. βCC, β-cyclocitral; PQH2, plastoquinone; PQ, oxidized form of plastoquinone; Cytb6f, cytochrome b6f complex; PC, plastocyanin.

In PSI, the stepwise production of O2− and H2O2 depends on ineffective photochemical and non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) (Havaux et al., 1991), giving away PSII-derived electrons to O2 through PSI-associated electron transport components (Figure 1). While SUPEROXIDE DISMUTASEs (SODs) catalyze the dismutation of O2− to O2 and H2O2, thylakoid membrane-associated and stromal ASCORBATE PEROXIDASEs (APXs) function in H2O2 detoxification through the ascorbate–glutathione cycle (Apel and Hirt, 2004) (Figure 1). Such an electron sink (also called the water–water cycle) is critical to balancing oxidation and reduction of the electron transport chain to maximize photosynthetic efficiency (Asada, 2006). The highly abundant stromal 2-Cys peroxiredoxins are also known to detoxify H2O2 in the presence of thioredoxin and NADPH-dependent thioredoxin reductase (NTRC) (Dietz et al., 2002; Konig et al., 2002; Broin and Rey, 2003). Chloroplasts that lack the cognate thioredoxin or NTRC thus experience overoxidation of 2-Cys peroxiredoxins, leading to increased lipid peroxidation and oxidative damage to the thylakoid membrane. Like 2-Cys peroxiredoxins, glutathione peroxidases are thought to catalyze H2O2 reduction and to reduce oxidative damage (Chang et al., 2009). Inefficient photochemical quenching under various stress conditions results in the over-reduction of the electron transport chain. The excess energy trapped in PSII then promotes 1O2 generation, thus also promoting the oxidation of PSII-associated electron acceptors. OH•, the most reactive free radical, is produced from H2O2 through the Fenton reaction in the presence of reduced transition metal ions such as copper (Cu+) or iron (Fe2+) that are generated by the O2−-dependent reduction of Cu2+ and Fe3+ (Figure 1). Although chloroplasts evolved with antioxidants and scavenging systems to maintain ROS homeostasis, severe or long-lasting stress conditions can rapidly deplete detoxifiers and inactivate scavenging systems. Hence, adversity results in ROS overproduction and enhanced chloroplast damage because of the reactivity of ROS toward macromolecules in their vicinity.

Among these chemically distinct ROS, 1O2 is primarily responsible for photodamage to proteins and lipids in chloroplasts (Triantaphylides and Havaux, 2009). Unlike H2O2, 1O2 has an extremely short lifespan and diffusion distance, limiting its release into the cytosol. Given 1O2 production in PSII and its immense reactivity toward electron-rich molecules, the rapid turnover rate of the D1 protein in PSII RC, regardless of light intensity, is attributed to the constant generation of 1O2 as a by-product of photosynthesis (Dreaden et al., 2011; Kale et al., 2017; Kumar et al., 2021; Mitra et al., 2021). Not only D1 but also other PSII core proteins (such as D2, CP43, and CP47), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), and other pigments (including β-carotene) can be oxidized by excess 1O2 (Lupinkova and Komenda, 2004; Duan et al., 2019). 1O2 oxidizes PUFAs, such as linoleic acid and linolenic acid, thereby producing reactive electrophile species (RES) that are implicated in cellular signaling networks (Dogra et al., 2018). Specific RES molecules appear to induce detoxification responses, conferring adaptive stress response to photo-oxidative stress. Similar to carotenoids, antioxidants such as α-tocopherol, ascorbate, and glutathione are known to be oxidized by 1O2, generating their own oxidized derivatives. More information regarding the 1O2-dependent oxidation of biomolecules is presented in Dogra et al. (2018). When the photon utilization and detoxification system becomes impaired under various stress conditions, oxidation of PSII core proteins may compromise the entire photosynthetic process unless the photosystem is reassembled rapidly by PSII quality control (also known as the PSII repair cycle) (Kato and Sakamoto, 2018). To date, research on PSII quality control has focused primarily on phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of the photodamaged D1 protein, direction of damaged PSII core migration from the grana core (appressed regions of the grana) to the grana margin (non-appressed regions), and turnover by the membrane-bound heterohexameric FtsH protease (Li et al., 2018). However, it remains unknown how ROS-driven oxidation of the D1 protein initiates PSII quality control. Perhaps its oxidation drives a conformational change of the PSII core, leading to the activation of PSII quality control.

Upon generation, 1O2 oxidizes only specific amino acid residues. Aromatic and hydrophobic amino acid residues (including tryptophan (Trp), tyrosine (Tyr), and phenylalanine (Phe)), histidine (His), methionine (Met), and cysteine (Cys) are known to be oxidized by 1O2 (Michaeli and Feitelson, 1994). Among these 1O2-sensitive residues, Trp is reported to scavenge 1O2 by both physical quenching and chemical reactions, rendering the Trp residue highly susceptible and rapidly reactive with 1O2. Given the short lifespan of 1O2 (∼200 ns) (Li et al., 2012; Telfer, 2014), a relatively small physical distance between Trp and 1O2 is a precondition for oxidation of the Trp residue in vivo. In addition, the Trp residue must be exposed on the surface of the target protein. Nonetheless, 1O2-driven oxidation of Trp leads to cleavage of the indole ring, generating oxidized Trp variants such as the dihydro-hydroxy derivative N-formylkynurenine (NFK) and kynurenine, with corresponding mass shifts of +32 and +4 Da, respectively (Perdivara et al., 2010; Dreaden et al., 2011; Dogra et al., 2019) (Figure 2A). Because Trp residues have been implicated in various biological processes, including protein–protein interaction and anchorage of peripheral membrane proteins on the lipid bilayer (Samanta and Chakrabarti, 2001; Feng et al., 2002; Clark et al., 2003; Dogra et al., 2019), cleavage of the indole ring could modulate Trp-linked biological processes. However, as mentioned above, the site of 1O2 generation and the physical distance to the Trp residue of the target protein must first be considered before further investigation. Similar to 1O2, ozone (O3) also oxidizes Trp residues, generating NFK and kynurenine (Figure 2A), and ultraviolet light (UV) oxidizes the indole side chain of Trp. Direct UV absorption produces a triplet state of Trp (3Trp), which rapidly undergoes electron transfer reactions and deprotonation to generate neutral Trp indolyl radicals (Figure 2A). The superoxide radical anion (O2−) further reacts with Trp indolyl radicals, forming Trp hydroperoxide and its subsequent end products NFK and kynurenine (Figure 2A). The interaction between HO• and Trp produces distinct oxidized Trp variants, such as oxindolealanine or several hydroxytryptophan molecules (Berlett et al., 1996; Ehrenshaft et al., 2015) (Figure 2A). The complex flow of Trp oxidation pathways suggests that PSI-associated proteins may also undergo O2−-dependent oxidation. In addition to Trp residues, a recent study demonstrated that another aromatic amino acid residue, tyrosine (Y) 246 in the D1 protein, can also be oxidized by OH• and O2− in PSII (Kumar et al., 2021). Its oxidation in the Arabidopsis vte1 mutant suggested the significance of α-tocopherol for preventing oxidative modification of the D1-Y246 residue. Considering the generation of other ROS in PSII through different mechanisms (Kumar et al., 2021), the oxidative modifications of PSII proteins under various stress conditions remain to be further explored.

Figure 2.

Oxidative post-translational modifications of Trp and Cys residues.

(A) The complex Trp oxidation network. HO•-mediated oxidation of Trp produces oxidized Trp variants, including oxindolealanine and several hydroxytryptophan molecules. The oxidation of Trp by O2−, 1O2, and O3 leads to Trp conversion into N-formylkynurenine and kynurenine with the cleavage of the indole ring.

(B) Cys thiol (RSH) oxidation. The RSH of the Cys residue undergoes various oxidative modifications by reacting with ROS (H2O2 and 1O2), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), reactive sulfur species (RSS), and oxidized glutathione (GSSG). The reduced form of glutathione (GSH) functions as a reducing agent, cleaving the disulfide bond and restabilizing the conformation. Different oxidations convert the RSH into oxidized Cys variants, including persulfide, S-nitrosothiol, S-glutathione, sulfenic acid, disulfide, sulfinic acid, zwitterion peroxide, and sulfonic acid. Reversible and irreversible modifications are indicated. The persulfide, S-nitrosothiol, S-glutathione, sulfenic acid, and disulfide can be reduced by small ubiquitous redox proteins such as thioredoxin (TRX) or glutaredoxin (GRX) (Klatt and Lamas, 2000). Sulfiredoxin (SRX) is responsible for reducing sulfinic acid into sulfenic acid (Biteau et al., 2003). Sulfinic acid can be further oxidized to an irreversible form of sulfonic acid, affecting protein functionality, conformation, and turnover rate.

The diffusible and long-lived H2O2 produced through the electron sink in PSI primarily oxidizes the thiol group of a Cys residue (Wang et al., 2012). However, given its relatively long lifespan, H2O2 may oxidize chloroplast proteins carrying Cys residues by chance. It is important to note that not only ROS but also other oxidizing agents such as RNS, RSS, and an oxidant—oxidized glutathione—can oxidize the thiol group of Cys, as shown in Figure 2B. Nonetheless, H2O2 induces reversible and irreversible oxidations of Cys residues (Figure 2B). Whereas irreversible Cys oxidation would facilitate protein degradation, reversible Cys oxidation may involve the on/off switching of biological processes or redox-sensitive signaling (Pajares et al., 2015). Bacterial elongation factor G (EF-G, including that of cyanobacteria) has been shown to form an ROS-dependent and thioredoxin (Trx)-reversible inter-disulfide bond between two Cys residues (Nishiyama et al., 2006; Kojima et al., 2009; Nagano et al., 2012). The disulfide bond (DSB) inactivates EF-G, thereby slowing protein translation. The Trx-dependent reactivation of EF-G enables the versatile regulation of translation in response to ever-changing environmental conditions. Interestingly, 1O2 can oxidize a DSB, generating reactive zwitterion peroxide (R-S+-OO−) (Figure 2B). This oxidized protein can form a disulfide crosslink with thiol-containing proteins (Jiang et al., 2021). This process can be reversed by reduced glutathione (GSH) (Figure 2B). Consecutive thiol oxidations by different ROS may escalate chloroplast damage by increasing the oxidation of target proteins, further impairing proteostasis. However, it remains unclear whether zwitterion peroxide occurs in plants.

Operational retrograde signaling pathways

βCC and MEcPP pathways

The discovery of two Arabidopsis mutants, chlorina1 (ch1) and fluorescent (flu), changed the classical view of 1O2 from toxin to signal and led us to gain insights into two distinct 1O2-signaling pathways (Meskauskiene et al., 2001; Ramel et al., 2013b). The ch1 mutant genome contains a mutation inactivating Chl a oxygenase, the enzyme that catalyzes Chl b synthesis. Because Chl b is required for the assembly of the peripheral light-harvesting antenna complexes, the ch1 mutant exhibits exacerbated photoinhibition in PSII RC under light-stress conditions (Ramel et al., 2013a, 2013b). Whereas excess light is required to generate 1O2 in PSII RC of ch1, the flu mutant produces 1O2 conditionally in the thylakoid membrane upon a dark-to-light shift (Dogra et al., 2018). FLU protein blocks the Mg2+ branch of tetrapyrrole synthesis in the dark, and the flu mutant therefore accumulates free protochlorophyllide (Pchlide) in the dark because the next conversion step from Pchlide to chlorophyllide requires light-dependent Pchlide oxidoreductase (POR) enzymes (Meskauskiene et al., 2001; Goslings et al., 2004). The excess free Pchlide serves as a photosensitizer, transferring absorbed light energy to molecular oxygen and thereby generating highly reactive 1O2. Through an unbiased forward genetic screen, 1O2-triggered stress responses, such as nuclear gene expression changes, cell death in young seedlings, and growth inhibition in mature flu mutant plants, were shown to be mediated by a nuclear-encoded chloroplast EXECUTER1 (EX1) protein (Wagner et al., 2004). Collectively, 1O2-triggered ORS pathways can be investigated under both photoinhibitory and non-photoinhibitory conditions by exploiting ch1 and flu, respectively.

Excess light-driven 1O2 production leads to oxidation and cleavage of β-carotene in the PSII RC in the grana core, producing various carbonyl products, namely apocarotenoids, in ch1 mutant and wild-type (WT) plants (Ramel et al., 2012a, 2012b, 2013a, 2013b) (Figure 3A). Among these products, β-cyclocitral (βCC) and dihydroactinidiolide (DhA) have been shown to be biologically active volatile compounds that mediate ORS (Ramel et al., 2012b). βCC- and DhA-induced nuclear transcriptomes confer plant tolerance under various abiotic stress conditions. The findings that PSII produces 1O2 and that 1O2 generates volatile signaling compounds through the oxidation of β-carotene suggest that PSII acts as a sensory apparatus, translating critical levels of 1O2 into the form of volatile signals. The excess light-released βCC induces detoxification-responsive genes via the GRAS protein transcription factor SCARECROW LIKE 14 (SCL14), primarily to mitigate lipid peroxidation-driven toxicity (D'Alessandro et al., 2018) (Figure 3A). The class II TGA factors TGA2, TGA5, and TGA6 recruit SCL14 to the promoters of SCL14 target genes that encode proteins required for detoxification responses (Fode et al., 2008). The SCL14-induced ANAC102 transcription factor is crucial for inducing detoxification-responsive genes (Christianson et al., 2009; D'Alessandro et al., 2020).

Figure 3.

Chloroplast ORS pathways.

(A) βCC-mediated ORS. High-light stress leads to a burst of 1O2 in PSII enriched in the grana core, resulting in the accumulation of oxidized β-carotene-derived volatile products such as βCC. βCC induces detoxification genes via the GRAS protein SCL14 and TGAII transcription factors. βCC also induces the ICS1 gene, encoding a key SA synthesis enzyme. The increased SA level then evokes SA-responsive genes through the SA receptor NPR1 and TGAII transcription factors. βCC also inhibits DXS, the rate-limiting enzyme in the MEP pathway.

(B) PAP- and MEcPP-mediated ORS pathways. Environmental factors, such as high light and drought, increase O2− and H2O2 levels in PSI, changing the chloroplast redox status. Such oxidative stress inactivates SAL1 phosphatase and HDS in the MEP pathway, resulting in PAP and MEcPP accumulation, respectively. PAP then mediates an ORS to induce plastid redox-associated genes by blocking the RNA-degrading activity of XRNs in the nucleus. Like PAP, MEcPP migrates to the nucleus to evoke the expression of stress-responsive genes in a Ca2+- and CAMTA3-dependent manner. The activation of CAMAT3 by MEcPP stabilizes the red-light photoreceptor PhyB with concurrent reductions in ethylene and auxin. MEcPP also elicits SA- and JA-responsive genes to modulate plant stress responses.

(C) EX1-mediated ORS in the grana margin. The 1O2-dependent oxidation of the Trp643 residue (Trp643oxi) in EX1 leads to FtsH2-dependent EX1 proteolysis, eliciting ORS. Another chloroplast protein, SAFE1, protects grana margin proteins from 1O2. The loss of SAFE1 induces EX1-independent 1O2-responsive genes (SORGs).

(D)1O2 generation by tetrapyrrole intermediates. The tetrapyrrole biosynthesis (TPB) pathways are divided into Chl and heme branches. In the Chl branch, MAGNESIUM CHELATASE (MgCh) inserts Mg2+, whereas in the heme branch, FERROCHELATASE (FeCh) inserts Fe2+. Most of the free tetrapyrrole intermediates containing the macrocycle structure can act as photosensitizers upon exposure to light, thereby generating 1O2. In the dark, the FLU protein negatively regulates the accumulation of Pchlide by repressing the synthesis of 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), the universal precursor of TPB.

(E) Lipid peroxidation-dependent 1O2 signaling. LOX-mediated oxidation of PUFAs (LH) generates lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH). LOOH can be reduced to lipid alkoxyl radical (LO•) in the presence of transition metals. Further reduction of LO• produces lipid radical (L•) and lipid hydroxide (LOH). Under oxidation-prone conditions, LOOH is oxidized into LOO•, which spontaneously forms high-energy intermediates such as cyclic endoperoxide (LOOL) and linear tetroxide (LOOOOL). Both LOO• and LOOOOL may directly generate triplet ketones (3L=O) or 1O2 through disproportionation reactions based on the Russell mechanism (Girotti, 1985). The thermal cleavage of LOOL is also known as the source of 3L=O. As an excited-state carbonyl, 3L=O can transfer excitation energy to O2 and Chl to form 1O2 and 1Chl, respectively. GAP, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; DXP, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate; DXR, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase; GGPP, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate; GA, gibberellic acid; tRNAGlu, glutamyl-tRNA.

βCC also rapidly induces a nuclear gene encoding ISOCHORISMATE SYNTHASE 1 (ICS1), a key enzyme involved in SA synthesis in chloroplasts. Induction of ICS1 leads to increased cellular SA levels and activation of NPR1 (NONEXPRESSER OF PR GENES1, an SA receptor), conferring plant acclimation to high-light stress (Lv et al., 2015; Mitra et al., 2021) (Figure 3A). This finding, along with the other reports mentioned above, confirms that βCC can activate both detoxification and SA signaling via SCL14-TGAIIs and NPR1-TGAIIs, respectively. Perhaps βCC-induced SA signaling antagonizes the lipid peroxidation-driven stress responses that are controlled in part by another stress hormone, JA, considering their well-established antagonism (Thaler et al., 2012). How Recent studies also indicate that the SA and JA signaling pathways synergistically aid plants in adapting to high-light stress (D'Alessandro et al., 2020). The synergistic activation of SA and JA signaling pathways has been found to confer basal thermotolerance in Arabidopsis (Clarke et al., 2009). Nonetheless, simulated herbivory (i.e., Spodoptera littoralis, oral secretion) also causes βCC release with a coincident upregulation of 1O2-responsive nuclear genes, suggesting that herbivory can lead to 1O2 release in chloroplasts, that excess light is dispensable for βCC generation, and that βCC signaling functions in response to biotic stress. βCC then suppresses the plastidial methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway by directly inhibiting DXP SYNTHASE (DXS), a rate-limiting enzyme in the MEP pathway, and repressing the expression of DXS (Mitra et al., 2021) (Figure 3B). The MEP pathway produces essential organic compounds that are ubiquitous precursors for Chl, carotenoids (including β-carotene), tocopherols (antioxidants), phylloquinone, gibberellic acid (GA), and ABA, connecting the MEP pathway to various important biological processes (especially photosynthesis) (Figure 3B). Therefore, DXS inhibition by βCC will significantly decrease plant growth and carbon assimilation, in addition to its positive roles in SA signaling and detoxification responses. βCC induced by mechanical wounding has a similar effect on the MEP pathway.

The significance of the MEP pathway for photosynthesis suggests that, like PSII, MEP components may act in ORS upon perturbation of the pathway by environmental factors. Indeed, the inactivation of the MEP pathway by excess light leads to the accumulation of an intermediate, methylerythritol cyclodiphosphate (MEcPP), which has been identified as an ORS molecule (Walley et al., 2015; Jiang and Dehesh, 2021) (Figure 3B). Consistently, various oxidative stresses inhibit HYDROXYMETHYL-BUTENYL DIPHOSPHATE SYNTHASE (HDS), which catalyzes the conversion of MEcPP to 2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl 4-diphosphate (HMBDP), resulting in MEcPP accumulation and ORS induction (Jiang and Dehesh, 2021) (Figure 3B). Further study demonstrated that CALMODULIN-BINDING TRANSCRIPTION ACTIVATOR 3 (CAMTA3) acts as a downstream signaling component of MEcPP to induce a suite of stress-related genes in the nucleus, including genes involved in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response (erUPR) (Benn et al., 2016) (Figure 3B). MEcPP also elicits JA-responsive genes upon an increased level of the JA precursor cis-(+)-12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (produced in chloroplasts via lipid peroxidation) but with nearly negligible levels of JA in the MEcPP-overproducing mutant, ceh1 (constitutively expressing hydroperoxide lyase1) (Lemos et al., 2016) (Figure 3B). The ceh1 mutant has been shown to have elevated cellular SA content and SA-responsive genes (Bjornson et al., 2017) (Figure 3B). Perhaps SA signaling may antagonize or modulate JA signaling to adjust MEcPP-triggered cellular stress responses (Gil et al., 2005). A forward genetic study aimed at finding suppressors of ceh1 demonstrated that MEcPP-dependent ORS stabilizes the red-light photoreceptor PHYTOCHROME B (PhyB) in a CAMTA- and Ca2+-dependent manner, suggesting that MEcPP functions in photomorphogenic growth in addition to its role in stress responses (Jiang et al., 2019) (Figure 3B). MEcPP also reduces auxin and ethylene levels by transcriptionally repressing PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 4 (PIF4) and PIF5, which are responsible for activating auxin and ethylene biosynthetic genes such as FLAVIN MONOOXYGENASEs and ACC SYNTHASEs, respectively (Figure 3B). These findings have established MEcPP as an upstream regulator that coordinates light and hormone signaling pathways. Not only stress but also developmental processes such as hypocotyl elongation and flowering are regulated by MEcPP in a dose-dependent manner (Wang et al., 2014, 2015). The multiple functions of MEcPP in adaptive plant stress responses through phytohormones and in plant growth through well-known molecular components such as PhyB suggest that MEcPP acts as a critical retrograde signal involved in the growth–stress tradeoff.

The facts that βCC inhibits the MEP pathway under various stress conditions and that β-carotene is one of the downstream products of the MEP pathway suggest a multifaceted interplay between 1O2-triggered and MEcPP-dependent ORS pathways. For instance, 1O2-driven βCC-mediated inhibition of the MEP pathway may attenuate the biosynthesis of β-carotene and photosynthesis, thereby repressing 1O2 generation (Figure 3A and 3B). Inhibition of the MEP pathway by βCC could also alter MEcPP-mediated plant stress responses that are coordinated by induced stress hormones, as mentioned above (Figure 3A and 3B). Thus, further investigation of the interlocking regulation of βCC- and MEcPP-mediated ORS pathways under controlled stress conditions or in mutants may unravel the complex modes of action of these two signaling molecules and their signaling cascades.

EX1-mediated 1O2 signaling and lipid peroxidation-dependent 1O2 signaling pathways

βCC is released from the photosynthetic PSII RC, which is enriched in the grana core, but the EX1 protein is exclusively localized in the grana margin (Wang et al., 2016), indicating a spatial separation of these two 1O2 sensors in the thylakoid membrane (Figure 3A and 3C). EX1 interacts with PSII core proteins, Chl synthesis enzymes (especially POR enzymes), the PSII quality control-associated FtsH protease, and a protein elongation factor in the grana margin (Wang et al., 2016; Dogra et al., 2018, 2019). Because all of these proteins are required for PSII quality control and reassembly, EX1 is thought to sense 1O2 generated by free Chl molecules or intermediate tetrapyrroles released accidentally during PSII quality control or reassembly (Dogra and Kim, 2019; Wang and Apel, 2019) (Figure 3C). Indeed, it is unknown whether the P680 Chl molecule must be replaced during D1 degradation/co-translational insertion or sequestered before recycling to avoid 1O2 production. Identifying a suite of Chl-binding proteins linked to PSII quality control suggests that such proteins may quench 1O2 in the grana margin or sequester free Chl molecules before recycling, thereby sustaining/protecting PSII repair (Yao et al., 2007, 2012; Nixon et al., 2010; Knoppova et al., 2014). In the event that stress factors disturb any steps in PSII quality control (e.g., sequestration of free tetrapyrroles by Chl-binding proteins), the accidentally released free Chl or tetrapyrrole molecules may generate 1O2 in the grana margin, enabling an EX1-dependent ORS independent of βCC. ROS also deactivate cyanobacterial EF-G by promoting intra-disulfide bond formation between two Cys residues (Nishiyama et al., 2006, 2011). Assuming that EF-G oxidation occurs in plant chloroplasts, the compromise of PSII reassembly by EF-G oxidation may increase the probability of free tetrapyrrole release in the grana margin, leading to a release of 1O2 in or on the grana margin and thereby stimulating EX1-dependent ORS. This notion encourages further study of chloroplast EF-G in the context of PSII repair, 1O2 generation, and EX1-dependent signaling from the grana margin.

Dogra et al. (2019) proposed a model of how EX1 protein senses 1O2 to initiate downstream physiological events, including cell death. Mass spectrometry analysis accurately determined an oxidation-prone Trp643 residue located in the 1O2 sensor domain (previously annotated as the domain of unknown function 3506) of EX1 (Figure 3C). In the flu mutant background, the conditional release of 1O2 in chloroplasts increases Trp643 oxidation, whereas Trp643 is maintained intact in darkness (Goslings et al., 2004; Dogra et al., 2019). The replacement of Trp643 with 1O2-insensitive but hydrophobic residues such as alanine (Ala) and leucine (Leu) completely abrogates 1O2-triggered stress responses in the flu mutant-like flu ex1 double mutant. The resulting FtsH2-dependent EX1 degradation in response to 1O2 appears to be an integral part of 1O2 signaling (Wang et al., 2016; Dogra et al., 2017; Kim, 2019), suggesting that EX1 proteolysis may promote the release of an actual signaling molecule (Figure 3C). Despite the apparent abrogation of 1O2 signaling by either EX1(Trp643Leu) or EX1(Trp643Ala), it is unclear whether Trp643 oxidation triggers FtsH-dependent EX1 turnover. Perhaps its replacement with a less oxidation-prone Phe (Ehrenshaft et al., 2015) may provide a piece of additional information to address this question. Among 1O2-responsive genes induced by EX1-mediated ORS, SIGMA FACTOR BINDING PROTEIN 1 (SIB1), WRKY33, and WRKY40 are also known to be rapidly induced by SA, suggesting possible crosstalk or interplay between 1O2 (EX1-dependent) and SA signaling. SA-induced SIB1 accumulates in both the nucleus and the chloroplasts (Lv et al., 2019). Nuclear SIB1 reinforces the expression of photosynthesis-associated nuclear genes (PhANGs), whereas chloroplast-localized SIB1 represses photosynthesis-associated plastid genes (PhAPGs), leading to genomes-uncoupled expression (especially of PSII components) and 1O2 generation due to impaired PSII stoichiometry. This genomes-uncoupled expression of PhANGs and PhAPGs appears to potentiate SA-mediated stress responses by activating EX1-mediated 1O2 signaling, collectively providing a first glimpse of the impact of genomes-uncoupled expression. In agreement with this finding, Arabidopsis mutants deficient in PSII proteostasis exhibit reinforced SA signaling in a light-dependent manner (Duan et al., 2019) (see “Chloroplast protein homeostasis and the unfolded protein response”).

A recent forward genetic study aimed at finding EX1-independent 1O2 signaling unveiled a novel chloroplast protein, dubbed SAFEGUARD 1 (SAFE1), which protects grana margin-associated proteins from oxidative damage and degradation (Wang et al., 2020) (Figure 3C). Interestingly, together with other proteins in the grana margin, the light-dependent POR enzymes that catalyze Pchlide conversion to chlorophyllide undergo rapid proteolysis upon release of 1O2 in the flu ex1 safe1 triple mutant. Consistently, the loss of SAFE1 re-evokes 1O2 signaling in the flu ex1 double mutant background, perhaps through increased oxidative damage to other proteins or lipids in the grana margin. Indeed, upon release of 1O2, an increased number of plastoglobules (oxidative stress markers) were observed in flu ex1 safe1 compared with flu and flu ex1. However, given its exclusive localization in the stroma and the absence of recognizable functional domains in SAFE1, the mechanism underlying the reactivation of 1O2 signaling in flu ex1 safe1 requires further exploration.

In flu, a 1O2 burst upon a dark-to-light shift results in chloroplast leakage, manifested by the release of stromal proteins to the cytosol, followed by vacuole rupture (Kim et al., 2012). This 1O2-driven chloroplast leakage was abrogated by the loss of EX1, indicating that it was ORS dependent. A similar cellular process was also observed in the ferrochelatase 2 (fc2) mutant owing to accumulated free protoporphyrin IX (Proto IX), as FC2 catalyzes the conversion of Proto IX to heme (Scharfenberg et al., 2015; Woodson et al., 2015) (Figure 3D). As free Pchlide generates 1O2 upon exposure to light, free Proto IX also acts as a photosensitizer. Like the flu mutant, the fc2 mutant exhibits chloroplast leakage and vacuole rupture upon release of 1O2 via accumulated free Proto IX. However, despite the similar cellular process associated with cell death, EX1 was found to be dispensable for the cell death response in the fc2 mutant (Woodson et al., 2015), indicating the presence of additional 1O2 signaling. Given the dual localization of FC2 in the envelope and thylakoid membranes (Roper and Smith, 1997), this 1O2-triggered but EX1-independent cell death suggests that 1O2 produced in the envelope membrane rather than in the thylakoid membrane may trigger EX1-independent cell death. Therefore, further exploration of the precise location of FC2 and of the spatial accumulation of free tetrapyrroles in chloroplasts may reveal an additional 1O2 signaling pathway in addition to the βCC- and EX1-mediated 1O2 signaling pathways. Like EX1-independent cell death in the fc2 mutant, OXIDATIVE SIGNAL-INDUCIBLE 1 (OXI1) kinase was found to mediate high-light-induced cell death in the ch1 mutant independently of the EX1 protein (Shumbe et al., 2016).

Similar to photosynthetic 1O2, non-photosynthetic 1O2 triggers programmed cell death accompanied by vacuole rupture (Chen and Fluhr, 2018). Multiple lines of evidence point to the generation of non-photosynthetic 1O2 in plants. It has been proposed that lipid peroxidation and its peroxyl radical products cause 1O2 generation (Kanofsky and Axelrod, 1986; Miyamoto et al., 2003; Prasad et al., 2017). Consistently, wounding and osmotic stress in dark-adapted leaves and roots lead to the production of 1O2 (Flors et al., 2006; Chen and Fluhr, 2018). LIPOXYGENASE (LOX)-mediated oxidation of PUFAs also elicits electronically excited triplet carbonyls, which generate 1O2 following interaction with ground-state oxygen (Kanofsky and Axelrod, 1986; Miyamoto et al., 2003; Prasad et al., 2017) (Figure 3E). Perhaps LOX-dependent 1O2 generation occurs in dark-adapted leaves in response to wounding or in roots upon osmotic stress (Flors et al., 2006; Chen and Fluhr, 2018), where stress-related phytohormones induce the expression of LOXs (Zhou et al., 2014; Upadhyay and Mattoo, 2018). However, 1O2 formation from triplet excited carbonyls in PSII has also been demonstrated (Pathak et al., 2017; Pospisil and Yamamoto, 2017), linking lipid peroxidation-dependent 1O2 generation to photosynthesis. ROS-dependent lipid peroxidation may also induce the expression of LOXs, further reinforcing LOX-dependent 1O2 generation. Indeed, an earlier study showed rapid upregulation of LOX2 and LOX3 in the flu mutant upon release of 1O2 in chloroplasts (Danon et al., 2005). Nevertheless, given the vital role of LOXs in JA synthesis, additional crosstalk between 1O2 and JA signaling can be proposed, in addition to the crosstalk between 1O2 and SA signaling. Because 1O2 positively contributes to SA signaling, as mentioned above, either antagonism or synergism may be expected to occur between 1O2 and JA signaling.

SAL1-dependent ORS pathway

The electron sink via PSI-associated ferredoxin generates O2− and H2O2, which undergo stepwise detoxification in which SODs and APXs play critical roles (Figure 1). This process is essential for maintaining PSII-associated electron acceptors in a partially oxidized state, allowing continuous electron transfer from PSII to PSI to produce chemical energy in the form of NADPH (Figure 1). However, unfavorable growth conditions lead to the accumulation of O2− and H2O2 in chloroplasts, perhaps because of their limited detoxification capacity. On the other hand, detoxification limitation and the existence of ORS pathways led us to consider chloroplasts as environmental sensors, translating ROS levels that exceed their detoxification capacity into signaling. The Arabidopsis sal1 mutant, which lacks the chloroplast nucleotide phosphatase SAL1, constitutively expresses APX2 under normal growth conditions and overexpresses APX2 upon exposure to high-light stress (Estavillo et al., 2011; Chan et al., 2016a, 2016b). The lack of SAL1 results in chloroplast accumulation of one of the SAL1 substrates, 3′(2′)-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphate (PAP) (Figure 3B). This PAP inhibits nuclear 5′-to-3′ EXORIBONUCLEASEs (XRNs), thereby affecting RNA catabolism and eliciting a post-transcriptionally altered nuclear transcriptome (Estavillo et al., 2011) (Figure 3B). Chan et al. (2016b) demonstrated that SAL1 undergoes ROS-dependent inactivation by forming intra- and inter-disulfide bridges at oxidation-prone Cys residues. In particular, PSI-sourced ROS notably diminish SAL1 activity in Arabidopsis (Figure 3B). Because high-light stress leads to the accumulation of MEcPP, PAP, and βCC via PSII/PSI-driven ROS, their crosstalk seems to be far more complicated than we can imagine (Figure 3A and 3B). The relative concentrations of each ROS, their lifespans, and their crosstalk with stress hormones must also be considered. Thus, mutants that constitutively overproduce these ORS molecules must have pleiotropic phenotypes rather than specific phenotypes, . Consistent with this concern, recent studies on PAP-XRN ORS revealed its impact on various biological processes, including the circadian clock, iron homeostasis, ABA signaling, and drought stress responses (Pornsiriwong et al., 2017; Litthauer et al., 2018; You et al., 2019; Balparda et al., 2020).

A study showed that PAP signaling contributes to ABA-mediated stress responses by upregulating multiple ABA and Ca2+ signaling components such as CALCIUM DEPENDENT PROTEIN KINASEs (CDPKs), CALCINEURIN B-LIKE PROTEINs (CBLs), and CBL-INTERACTING PROTEIN KINASEs (Pornsiriwong et al., 2017). The sal1 mutant thus shows increased stomatal closure under excess light as well as enhanced drought resistance, implying a positive correlation between PAP and ABA signaling (Rossel et al., 2006; Pornsiriwong et al., 2017). Consistent with this notion, the inactivation of SAL1 restores the ABA responses of Arabidopsis mutants defective in ABA response.

As the interplay between chloroplast H2O2 and ABA response in guard cells has been demonstrated, PAP-mediated ORS appears to activate ABA signaling upon an increase in H2O2 in chloroplasts.

Chloroplast protein homeostasis and the unfolded protein response

Chloroplast protein homeostasis is controlled by the balance of de novo translation and degradation of unfolded/misfolded/damaged proteins in response to internal and external cues. Because nuclear DNA encodes the vast majority of chloroplast proteins, chloroplast proteostasis also requires nuclear genome coordination for dynamic protein quality control. In particular, a dysfunctional chloroplast defective in proteostasis would require the constant transcription/translation of a suite of nuclear genes encoding proteins involved in protein quality control in order to compensate for the chloroplast dysfunction. For instance, the chloroplasts in the Arabidopsis yellow variegated 2 (var2) mutant, lacking the membrane-bound FtsH2 metalloprotease involved in PSII repair, induce a chloroplast unfolded/misfolded/damaged protein response (cpUPR), primarily due to excess accumulation of oxidized PSII core proteins (Dogra et al., 2019a) (Figure 4A). Similar to the erUPR and the mitochondrial UPR (Walter and Ron, 2011; Naresh and Haynes, 2019), the ftsh2-elicited cpUPR leads to upregulation of a group of nuclear transcripts that encode chloroplast proteins involved in protein quality control and ROS detoxification (Dogra et al., 2019a) (Figure 4A). These chloroplast-targeted proteins may compensate for the ftsh2-induced deficiency in proteostasis. A comparable molecular phenotype caused by the cpUPR was also observed in Chlamydomonas and Arabidopsis mutants that exhibited reduced stromal Clp protease activity (Ramundo et al., 2014; Llamas et al., 2017; Kessler and Longoni, 2019). Interestingly, the clp-induced chloroplast-targeted chaperones Hsp70 and ClpB3 refold aggregated DXS, the rate-limiting enzyme in the MEP pathway, in Arabidopsis clp mutant and WT plants treated with lincomycin, a prokaryotic translation inhibitor (Figure 4B). Increased levels of both chaperones are also observed in var2 (Figure 4A), indicating that the MEP pathway is likely to be inactivated under chloroplast proteostasis-impairing, ROS-overproducing stress conditions. Moreover, enhanced levels of SA (ICS-dependent) and SA signaling were observed in the var2 mutant (Figure 4A), linking impaired proteostasis or increased photodamage in chloroplasts to the constitutive activation of SA signaling (Duan et al., 2019). Consistent with this finding, a recent study on PSII photoinhibition revealed a novel function of SA in protecting PSII and alleviating photoinhibition (Chen et al., 2020).

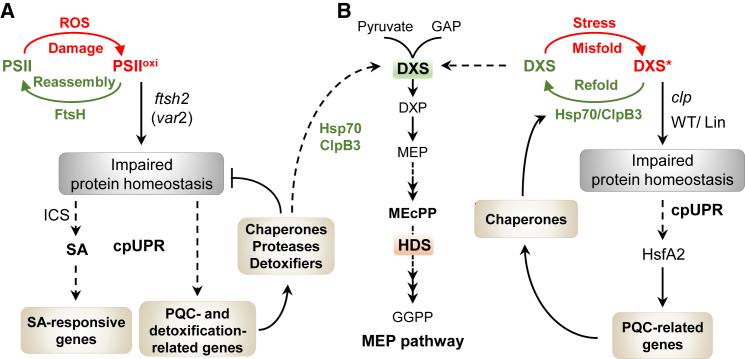

Figure 4.

Impaired chloroplast proteostasis triggers an unfolded protein response.

(A) ROS-driven PSII damage (PSIIoxi) is inevitable during photosynthesis. The thylakoid membrane FtsH protease, a heterohexameric complex, degrades damaged PSII core proteins, promoting PSII reassembly. The Arabidopsis var2 mutant, which lacks the major subunit of the FtsH hexamer FtsH2, accumulates oxidized PSII core proteins with a concurrent expression of genes required for chloroplast protein quality control (PQC) and ROS detoxification, a signaling pathway dubbed the chloroplast UPR (cpUPR). The var2-evoked cpUPR facilitates the removal of damaged chloroplast proteins, thereby restoring chloroplast proteostasis to a certain extent. Impaired PSII proteostasis causes accumulation of SA via the chloroplast isochorismate (ICS) pathway, resulting in the enhanced expression of SA-responsive genes.

(B) A similar molecular response has also been shown in Arabidopsis and Chlamydomonas mutants with reduced stromal Clp protease activity. The cpUPR restores the aggregated enzyme DXS∗ in the MEP pathway in both the Arabidopsis clp mutant and WT plants treated with lincomycin (Lin, a prokaryotic translation inhibitor). Treating WT seedlings with Lin impairs the expression of plastid-encoded Clp protease subunits, thereby repressing Clp protease activity and inducing the cpUPR. The cpUPR-induced HEAT STRESS TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR A-2 (HsfA2) positively regulates the expression of PQC-related nuclear genes. Among them, chaperones Hsp70 and ClpB3 refold the aggregated DXS enzyme. Increased levels of both chaperones are also observed in the var2 mutant, suggesting that var2-driven oxidative stress may lead to aggregation of the DXS enzyme in the MEP pathway.

It is worth mentioning that MEcPP induces erUPR genes in the ceh1 mutant (Walley et al., 2015), connecting MEcPP-mediated ORS with the erUPR. Similarly, 1O2 generation in the ch1 mutant under moderate light or excess light conditions and in the flu mutant after a dark-to-light transition appears to activate the erUPR and the upregulation of nucleus-encoded genes involved in the erUPR (op den Camp et al., 2003; Ramel et al., 2013b; Beaugelin et al., 2020). Consistent with these observations, the erUPR modulates plant resistance to high-light stress to varying degrees. Mild induction of the erUPR in plants treated with a low concentration of tunicamycin (Tm, an inhibitor of protein glycosylation, which thus induces ER stress) protects the plant from photo-oxidative damage under high-light stress. By contrast, a high concentration of Tm, which strongly induces the erUPR, leads to extensive photo-oxidative damage and cell death upon exposure to high-light stress (Beaugelin et al., 2020). Collectively, these findings suggest that 1O2 and MEcPP production in chloroplasts stimulate induction of the erUPR, affecting whole-cell stress responses, including proteostasis.

Concluding remarks and future directions

Although photosynthesis is one of the oldest metabolic pathways, it is also known, paradoxically, to be the most sensitive to light. For chloroplast biologists, whose research focuses mainly on stress, the most intriguing products of photosynthesis are the ROS. Because they primarily attack photosystems, aggravating PSII photoinhibition and thus compromising photosynthesis, it is surprising that ROS still cause such problems in plants after almost 2.5 billion years of oxygenic photosynthesis. If photosynthetic ROS only cause photodamage, plants must suffer during their entire lifespan. In this regard, ROS-triggered ORS involved in various physiological processes provides an essential clue to how plants have co-evolved with oxygenic photosynthesis together with ROS. However, our understanding of ROS pathways remains superficial, especially regarding their communication with other well-known signaling pathways triggered by various stress factors. Although the chloroplast is the leading factory producing stress hormones, it is yet unknown how chloroplast ROS signaling pathways interact with SA, JA, and ABA signaling pathways and whether there are signaling hubs that integrate these signaling pathways and regulate them appropriately. Combining “omics” technologies and reverse genetic approaches with conditional ROS and stress hormone biosynthesis/signaling mutants would help us to resolve the complexity of these signaling networks.

Given that chloroplasts rapidly overaccumulate chemically distinct ROS upon exposure to various stress factors, investigating oxidative modification of chloroplast proteins in a non-targeted manner may facilitate the study of sensory proteins involved in ORS. Perhaps various stress factors induce different and distinct oxidation profiles of chloroplast proteins, providing an important clue regarding the primary ROS that plays a dominant role under specific stress conditions. Not only signaling but also detoxification of ROS and lipid peroxides can be modulated by replacing oxidation-prone residues, such as Trp and Cys, in target proteins. For instance, oxidation-prone Trp residues in PSII core proteins can be substituted in Chlamydomonas or model plants to explore the biological significance of these oxidations in the context of photodamage and photoprotection. It would also be inspiring to examine whether ROS-detoxifying enzymes undergo ROS-dependent oxidation, by which one could also modulate their stability and activity.

Like beneficial bacteria, which enhance plant growth and stress tolerance by producing volatile compounds, the endosymbiont chloroplasts also produce volatile compounds that play critical roles in promoting plant growth and stress resistance. The positive nature of volatile apocarotenoids and their electrophilic characteristics already indicate the next goal of this research, i.e., finding the receptor or receptor complex responsible for the physiological responses under volatile-inducible oxidative environmental conditions. The receptor may be present within the chloroplast or the cytoplasm. However, given their versatile impact on abiotic and biotic stress responses, the volatile apocarotenoids may converge with known signaling pathways (e.g., stress hormone signaling pathways). Not only single but perhaps multiple signaling components may sense biologically active concentrations of volatile apocarotenoids to enhance or repress their signaling cascades. Because βCC modulates the MEP pathway and phytohormone-mediated stress signaling, finding its receptor(s) and/or interacting protein(s) may unravel the complexity of βCC-related signaling networks.

Chloroplast-to-nucleus retrograde signaling pathways contribute to plant stress responses, including acclimation and cell death, in response to various stress factors rather than being central signaling pathways. Otherwise, earlier forward genetic screens to find vital components of plant stress responses under abiotic and biotic stress conditions would have revealed chloroplast proteins as central regulators. Instead, chloroplast signaling pathways seem to modulate plant stress responses by utilizing various oxidation-prone signaling components and oxidation-sensitive metabolisms. The genetic and chemical manipulation of their sensitivity toward ROS and redox changes could pave the way for agricultural innovation.

Funding

Research in the Kim laboratory has been supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant XDB27040102), the 100-Talent Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 31871397 to C.K.).

Acknowledgments

We thank anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and critical suggestions on the manuscript. We also apologize to those authors whose findings are not mentioned in this review due to restricted space. No conflict of interest declared.

Published: November 9, 2021

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and CEMPS, CAS.

References

- Apel K., Hirt H. Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004;55:373–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada K. Production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species in chloroplasts and their functions. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:391–396. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.082040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balparda M., Armas A.M., Estavillo G.M., Roschzttardtz H., Pagani M.A., Gomez-Casati D.F. The PAP/SAL1 retrograde signaling pathway is involved in iron homeostasis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2020;102:323–337. doi: 10.1007/s11103-019-00950-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaugelin I., Chevalier A., D'Alessandro S., Ksas B., Havaux M. Endoplasmic reticulum-mediated unfolded protein response is an integral part of singlet oxygen signalling in plants. Plant J. 2020;102:1266–1280. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benn G., Bjornson M., Ke H., De Souza A., Balmond E.I., Shaw J.T., Dehesh K. Plastidial metabolite MEcPP induces a transcriptionally centered stress-response hub via the transcription factor CAMTA3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2016;113:8855–8860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602582113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlett B.S., Levine R.L., Stadtman E.R. Comparison of the effects of ozone on the modification of amino acid residues in glutamine synthetase and bovine serum albumin. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:4177–4182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biteau B., Labarre J., Toledano M.B. ATP-dependent reduction of cysteine-sulphinic acid by S. cerevisiae sulphiredoxin. Nature. 2003;425:980–984. doi: 10.1038/nature02075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornson M., Balcke G.U., Xiao Y., de Souza A., Wang J.Z., Zhabinskaya D., Tagkopoulos I., Tissier A., Dehesh K. Integrated omics analyses of retrograde signaling mutant delineate interrelated stress-response strata. Plant J. 2017;91:70–84. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broin M., Rey P. Potato plants lacking the CDSP32 plastidic thioredoxin exhibit overoxidation of the BAS1 2-cysteine peroxiredoxin and increased lipid peroxidation in thylakoids under photooxidative stress. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:1335–1343. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K.X., Phua S.Y., Crisp P., McQuinn R., Pogson B.J. Learning the languages of the chloroplast: retrograde signaling and beyond. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2016;67:25–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-111854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K.X., Mabbitt P.D., Phua S.Y., Mueller J.W., Nisar N., Gigolashvili T., Stroeher E., Grassl J., Arlt W., Estavillo G.M., et al. Sensing and signaling of oxidative stress in chloroplasts by inactivation of the SAL1 phosphoadenosine phosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2016;113:E4567–E4576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604936113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.C., Slesak I., Jorda L., Sotnikov A., Melzer M., Miszalski Z., Mullineaux P.M., Parker J.E., Karpinska B., Karpinski S. Arabidopsis chloroplastic glutathione peroxidases play a role in cross talk between photooxidative stress and immune responses. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:670–683. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.135566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Jia H., Tian Q., Du L., Gao Y., Miao X., Liu Y. Protecting effect of phosphorylation on oxidative damage of D1 protein by down-regulating the production of superoxide anion in photosystem II membranes under high light. Photosynth. Res. 2012;112:141–148. doi: 10.1007/s11120-012-9750-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Fluhr R. Singlet oxygen plays an essential role in the root’s response to osmotic stress. Plant Physiol. 2018;177:1717–1727. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.E., Mao, H.T., Wu, N., Mohi Ud Din, A., Khan, A., Zhang, H.Y., and Yuan, S. (2020). Salicylic Acid Protects Photosystem II by Alleviating Photoinhibition in Arabidopsis thaliana under High Light. Int J Mol Sci, 21, 10.3390/ijms21041229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Christianson J.A., Wilson I.W., Llewellyn D.J., Dennis E.S. The low-oxygen-induced NAC domain transcription factor ANAC102 affects viability of Arabidopsis seeds following low-oxygen treatment. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:1724–1738. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.131912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark E.H., East J.M., Lee A.G. The role of tryptophan residues in an integral membrane protein: diacylglycerol kinase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11065–11073. doi: 10.1021/bi034607e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S.M., Cristescu S.M., Miersch O., Harren F.J.M., Wasternack C., Mur L.A.J. Jasmonates act with salicylic acid to confer basal thermotolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2009;182:175–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alessandro S., Ksas B., Havaux M. Decoding beta-cyclocitral-mediated retrograde signaling reveals the role of a detoxification response in plant tolerance to photooxidative stress. Plant Cell. 2018;30:2495–2511. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Alessandro S., Beaugelin I., Havaux M. Tanned or sunburned: how excessive light triggers plant cell death. Mol. Plant. 2020;13:1545–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danon A., Miersch O., Felix G., Camp R.G., Apel K. Concurrent activation of cell death-regulating signaling pathways by singlet oxygen in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2005;41:68–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz K.J., Horling F., Konig J., Baier M. The function of the chloroplast 2-cysteine peroxiredoxin in peroxide detoxification and its regulation. J. Exp. Bot. 2002;53:1321–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogra V., Kim C. Singlet oxygen metabolism: from genesis to signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:1640. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogra V., Rochaix J.D., Kim C. Singlet oxygen-triggered chloroplast-to-nucleus retrograde signalling pathways: an emerging perspective. Plant Cell Environ. 2018;41:1727–1738. doi: 10.1111/pce.13332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogra V., Li M., Singh S., Li M., Kim C. Oxidative post-translational modification of EXECUTER1 is required for singlet oxygen sensing in plastids. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2834. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10760-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogra V., Duan J., Lee K.P., Lv S., Liu R., Kim C. FtsH2-Dependent proteolysis of EXECUTER1 is essential in mediating singlet oxygen-triggered retrograde signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:1145. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogra V., Duan J., Lee K.P., Kim C. Impaired PSII proteostasis triggers a UPR-like response in the var2 mutant of Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2019;70:3075–3088. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreaden T.M., Chen J., Rexroth S., Barry B.A. N-formylkynurenine as a marker of high light stress in photosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:22632–22641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.212928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J., Lee K.P., Dogra V., Zhang S., Liu K., Caceres-Moreno C., Lv S., Xing W., Kato Y., Sakamoto W., et al. Impaired PSII proteostasis promotes retrograde signaling via salicylic acid. Plant Physiol. 2019;180:2182–2197. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.00483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenshaft M., Deterding L.J., Mason R.P. Tripping up Trp: modification of protein tryptophan residues by reactive oxygen species, modes of detection, and biological consequences. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;89:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estavillo G.M., Crisp P.A., Pornsiriwong W., Wirtz M., Collinge D., Carrie C., Giraud E., Whelan J., David P., Javot H., et al. Evidence for a SAL1-PAP chloroplast retrograde pathway that functions in drought and high light signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2011;23:3992–4012. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.091033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J., Wehbi H., Roberts M.F. Role of tryptophan residues in interfacial binding of phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:19867–19875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200938200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flors C., Fryer M.J., Waring J., Reeder B., Bechtold U., Mullineaux P.M., Nonell S., Wilson M.T., Baker N.R. Imaging the production of singlet oxygen in vivo using a new fluorescent sensor, Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:1725–1734. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fode B., Siemsen T., Thurow C., Weigel R., Gatz C. The Arabidopsis GRAS protein SCL14 interacts with class II TGA transcription factors and is essential for the activation of stress-inducible promoters. Plant Cell. 2008;20:3122–3135. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil M.J., Coego A., Mauch-Mani B., Jorda L., Vera P. The Arabidopsis csb3 mutant reveals a regulatory link between salicylic acid-mediated disease resistance and the methyl-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway. Plant J. 2005;44:155–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girotti A.W. Mechanisms of lipid peroxidation. J. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1985;1:87–95. doi: 10.1016/0748-5514(85)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goslings D., Meskauskiene R., Kim C., Lee K.P., Nater M., Apel K. Concurrent interactions of heme and FLU with Glu tRNA reductase (HEMA1), the target of metabolic feedback inhibition of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis, in dark- and light-grown Arabidopsis plants. Plant J. 2004;40:957–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havaux M., Strasser R.J., Greppin H. A theoretical and experimental analysis of the qP and q N coefficients of chlorophyll fluorescence quenching and their relation to photochemical and nonphotochemical events. Photosynth Res. 1991;27:41–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00029975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Dehesh K. Plastidial retrograde modulation of light and hormonal signaling: an odyssey. New Phytol. 2021;230:931–937. doi: 10.1111/nph.17192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Zeng L., Ke H., De La Cruz B., Dehesh K. Orthogonal regulation of phytochrome B abundance by stress-specific plastidial retrograde signaling metabolite. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2904. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10867-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S., Carroll L., Mariotti M., Hagglund P., Davies M.J. Formation of protein cross-links by singlet oxygen-mediated disulfide oxidation. Redox Biol. 2021;41:101874. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.101874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale R., Hebert A.E., Frankel L.K., Sallans L., Bricker T.M., Pospisil P. Amino acid oxidation of the D1 and D2 proteins by oxygen radicals during photoinhibition of Photosystem II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2017;114:2988–2993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618922114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanofsky J.R., Axelrod B. Singlet oxygen production by soybean lipoxygenase isozymes. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:1099–1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y., Sakamoto W. FtsH protease in the thylakoid membrane: physiological functions and the regulation of protease activity. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:855. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, F., and Longoni, P. (2019). How chloroplasts protect themselves from unfolded proteins. Elife 8, 10.7554/eLife.51430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Khorobrykh S., Havurinne V., Mattila H., Tyystjarvi E. Oxygen and ROS in photosynthesis. Plants. 2020;9:91. doi: 10.3390/plants9010091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. ROS-driven oxidative modification: its impact on chloroplasts-nucleus communication. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:1729. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C., Apel K. Singlet oxygen-mediated signaling in plants: moving from flu to wild type reveals an increasing complexity. Photosynth. Res. 2013;116:455–464. doi: 10.1007/s11120-013-9876-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C., Meskauskiene R., Zhang S., Lee K.P., Lakshmanan Ashok M., Blajecka K., Herrfurth C., Feussner I., Apel K. Chloroplasts of Arabidopsis are the source and a primary target of a plant-specific programmed cell death signaling pathway. Plant Cell. 2012;24:3026–3039. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.100479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatt P., Lamas S. Regulation of protein function by S-glutathiolation in response to oxidative and nitrosative stress. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:4928–4944. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleine T., Leister D. Retrograde signaling: organelles go networking. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1857:1313–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoppova J., Sobotka R., Tichy M., Yu J., Konik P., Halada P., Nixon P.J., Komenda J. Discovery of a chlorophyll binding protein complex involved in the early steps of photosystem II assembly in Synechocystis. Plant Cell. 2014;26:1200–1212. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.123919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima K., Motohashi K., Morota T., Oshita M., Hisabori T., Hayashi H., Nishiyama Y. Regulation of translation by the redox state of elongation factor G in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:18685–18691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.015131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig J., Baier M., Horling F., Kahmann U., Harris G., Schurmann P., Dietz K.J. The plant-specific function of 2-Cys peroxiredoxin-mediated detoxification of peroxides in the redox-hierarchy of photosynthetic electron flux. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99:5738–5743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072644999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Prasad A., Sedlarova M., Kale R., Frankel L.K., Sallans L., Bricker T.M., Pospisil P. Tocopherol controls D1 amino acid oxidation by oxygen radicals in Photosystem II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2019246118. e2019246118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos M., Xiao Y., Bjornson M., Wang J.Z., Hicks D., Souza A., Wang C.Q., Yang P., Ma S., Dinesh-Kumar S., et al. The plastidial retrograde signal methyl erythritol cyclopyrophosphate is a regulator of salicylic acid and jasmonic acid crosstalk. J. Exp. Bot. 2016;67:1557–1566. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Melo T.B., Arellano J.B., Razi Naqvi K. Temporal profile of the singlet oxygen emission endogenously produced by photosystem II reaction centre in an aqueous buffer. Photosynth. Res. 2012;112:75–79. doi: 10.1007/s11120-012-9739-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Aro E.M., Millar A.H. Mechanisms of photodamage and protein turnover in photoinhibition. Trends Plant Sci. 2018;23:667–676. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llamas E., Pulido P., Rodriguez-Concepcion M. Interference with plastome gene expression and Clp protease activity in Arabidopsis triggers a chloroplast unfolded protein response to restore protein homeostasis. PLoS Genet. 2017;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litthauer S., Chan K.X., Jones M.A. 3′-Phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphate accumulation delays the circadian system. Plant Physiol. 2018;176:3120–3135. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupinkova L., Komenda J. Oxidative modifications of the Photosystem II D1 protein by reactive oxygen species: from isolated protein to cyanobacterial cells. Photochem. Photobiol. 2004;79:152–162. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2004)079<0152:omotpi>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv F., Zhou J., Zeng L., Xing D. beta-cyclocitral upregulates salicylic acid signalling to enhance excess light acclimation in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2015;66:4719–4732. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv R., Li Z., Li M., Dogra V., Lv S., Liu R., Lee K.P., Kim C. Uncoupled expression of nuclear and plastid photosynthesis-associated genes contributes to cell death in a lesion mimic mutant. Plant Cell. 2019;31:210–230. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meskauskiene R., Nater M., Goslings D., Kessler F., Op den Camp R., Apel K. FLU: a negative regulator of chlorophyll biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2001;98:12826–12831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221252798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaeli A., Feitelson J. Reactivity of singlet oxygen toward amino acids and peptides. Photochem. Photobiol. 1994;59:284–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1994.tb05035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S., Estrada-Tejedor R., Volke D.C., Phillips M.A., Gershenzon J., Wright L.P. Negative regulation of plastidial isoprenoid pathway by herbivore-induced beta-cyclocitral in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2008747118. e2008747118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S., Martinez G.R., Medeiros M.H., Di Mascio P. Singlet molecular oxygen generated from lipid hydroperoxides by the russell mechanism: studies using 18(O)-labeled linoleic acid hydroperoxide and monomol light emission measurements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:6172–6179. doi: 10.1021/ja029115o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller P., Li X.P., Niyogi K.K. Non-photochemical quenching. A response to excess light energy. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:1558–1566. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.4.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano T., Kojima K., Hisabori T., Hayashi H., Morita E.H., Kanamori T., Miyagi T., Ueda T., Nishiyama Y. Elongation factor G is a critical target during oxidative damage to the translation system of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:28697–28704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.378067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naresh, N.U., and Haynes, C.M. (2019). Signaling and Regulation of the Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 11; 10.1101/cshperspect.a033944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama Y., Allakhverdiev S.I., Murata N. A new paradigm for the action of reactive oxygen species in the photoinhibition of photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1757:742–749. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama Y., Allakhverdiev S.I., Murata N. Protein synthesis is the primary target of reactive oxygen species in the photoinhibition of photosystem II. Physiol. Plant. 2011;142:35–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2011.01457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon P.J., Michoux F., Yu J., Boehm M., Komenda J. Recent advances in understanding the assembly and repair of photosystem II. Ann. Bot. 2010;106:1–16. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcq059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelmuller R., Mohr H. Photooxidative destruction of chloroplasts and its consequences for expression of nuclear genes. Planta. 1986;167:106–113. doi: 10.1007/BF00446376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- op den Camp R.G., Przybyla D., Ochsenbein C., Laloi C., Kim C., Danon A., Wagner D., Hideg E., Gobel C., Feussner I., et al. Rapid induction of distinct stress responses after the release of singlet oxygen in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2320–2332. doi: 10.1105/tpc.014662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajares M., Jimenez-Moreno N., Dias I.H.K., Debelec B., Vucetic M., Fladmark K.E., Basaga H., Ribaric S., Milisav I., Cuadrado A. Redox control of protein degradation. Redox Biol. 2015;6:409–420. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak V., Prasad A., Pospisil P. Formation of singlet oxygen by decomposition of protein hydroperoxide in photosystem II. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdivara I., Deterding L.J., Przybylski M., Tomer K.B. Mass spectrometric identification of oxidative modifications of tryptophan residues in proteins: chemical artifact or post-translational modification? J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2010;21:1114–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogson B.J., Woo N.S., Forster B., Small I.D. Plastid signalling to the nucleus and beyond. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:602–609. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pornsiriwong W., Estavillo G.M., Chan K.X., Tee E.E., Ganguly D., Crisp P.A., Phua S.Y., Zhao C., Qiu J., Park J., et al. A chloroplast retrograde signal, 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphate, acts as a secondary messenger in abscisic acid signaling in stomatal closure and germination. eLife. 2017;6:e23361. doi: 10.7554/eLife.23361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pospisil P. Production of reactive oxygen species by photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1787:1151–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pospisil P. The role of metals in production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species in photosystem II. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:1224–1232. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pospisil P. Production of reactive oxygen species by photosystem II as a response to light and temperature stress. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1950. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pospisil P., Yamamoto Y. Damage to photosystem II by lipid peroxidation products. BBA Gen. Subj. 2017;1861:457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pospisil P., Arato A., Krieger-Liszkay A., Rutherford A.W. Hydroxyl radical generation by photosystem II. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6783–6792. doi: 10.1021/bi036219i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]