Abstract

Reproduction is a crucial process in the life span of flowering plants, and directly affects human basic requirements in agriculture, such as grain yield and quality. Typical receptor-like protein kinases (RLKs) are a large family of membrane proteins sensing extracellular signals to regulate plant growth, development, and stress responses. In Arabidopsis thaliana and other plant species, RLK-mediated signaling pathways play essential roles in regulating the reproductive process by sensing different ligand signals. Molecular understanding of the reproductive process is vital from the perspective of controlling male and female fertility. Here, we summarize the roles of RLKs during plant reproduction at the genetic and molecular levels, including RLK-mediated floral organ development, ovule and anther development, and embryogenesis. In addition, the possible molecular regulatory patterns of those RLKs with unrevealed mechanisms during reproductive development are discussed. We also point out the thought-provoking questions raised by the research on these plant RLKs during reproduction for future investigation.

Keywords: anther, embryo, floral meristem, ovule, receptor-like protein kinase, reproductive development

RLKs play essential roles in regulating plant reproductive development. This review summarizes our current understanding of the roles of RLKs in controlling floral organ development, ovule and anther development, and embryogenesis. The possible signaling pathways mediated by these RLKs during plant reproductive development and the related perspectives are discussed.

Introduction

The whole life cycle of higher plants can be divided into two phases: the vegetative phase and the reproductive phase. Plants in the vegetative phase generate vegetative organs such as roots, stems, and leaves, whereas in the reproductive stage they can form the floral organs (Coen and Meyerowitz, 1991; Meyerowitz, 1997). The successful reproduction of plants depends on the fine coordination of the entire reproductive process, including flower transition, floral organ development, gametophyte development, gamete formation, male-female recognition, double fertilization, and embryogenesis, which ultimately produces the seeds to continue the plant species. The model plant Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) has a typical cruciferous flower structure, and numerous mechanisms about its floral organ development, fertilization, and embryo development have been well studied (Coen and Meyerowitz, 1991; Weigel and Meyerowitz, 1994; Sreenivasulu and Wobus, 2013; Johnson et al., 2019).

During the reproductive stage of Arabidopsis, the shoot apical meristem (SAM) acquires the identity of the inflorescence meristem, which will then produce the floral meristem flanking the inflorescence meristem (Meyerowitz, 1997; Kwiatkowska, 2006, 2008; Han et al., 2020). Although the floral meristem is similar to the SAM regarding their structures, the floral meristem belongs to terminal meristems (Lenhard et al., 2001; Lohmann et al., 2001; Sun and Ito, 2010). The floral meristem undergoes a series of cell differentiation and finally produces a flower composed of four whorls of organs in Arabidopsis, from outside to inside including sepals, petals, stamens, and carpels (Coen and Meyerowitz, 1991; Irish, 2010). Sepals and petals are perianth organs that constitute the first and second floral layers, respectively, whereas stamens and carpels are reproductive organs that make up the third and innermost floral layers, respectively. Stamens are the male reproductive organs, which are composed of anthers and filaments. After a series of continuous developmental processes, pollen grains, the male gametophytes, are finally formed in the anther to produce sperm cells (Sanders et al., 1999; Ma, 2005; Chang et al., 2011; Schmidt et al., 2015). Ovules, which are packaged and protected by the carpels, provide space for the development of embryo sacs, the female gametophytes that generate the egg and the central cell (Yang et al., 2010; Schmidt et al., 2015; Hater et al., 2020). Reproduction of Arabidopsis requires the transfer of sperm cells into the embryo sac, where double fertilization is performed to generate the embryo and endosperm (Lau et al., 2012; Shin et al., 2020; Hafidh and Honys, 2021; Kim et al., 2021).

The whole reproductive process relies on complex cell-to-environment and cell-to-cell communications. Especially, many events are controlled by extracellular signaling molecules that are perceived by their receptors to transduce the signals into the nucleus (Kim and Wang, 2010; Hohmann et al., 2017). In Arabidopsis, receptor-like protein kinases (RLKs) constitute one of the most studied protein families, which play vital roles in the perception of extracellular signals such as plant hormones and secreted peptides. A typical RLK is usually composed of at least three protein domains: an extracellular domain mainly responsible for the perception of a ligand molecule, a transmembrane domain anchoring the protein in the cell membrane system, and a cellular kinase domain transducing the signal to downstream regulators mainly through phosphorylation (Shiu and Bleecker, 2001a, 2001b; Torii, 2004; Hohmann et al., 2017; Dievart et al., 2020; Gou and Li, 2020). More and more reports have shown that RLKs are involved in a number of developmental processes during vegetative growth. One well studied among them is BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1 (BRI1), the major receptor of brassinosteroid (BR), which mediates the BR signal to regulate cell elongation required for normal growth and development of the plant (Clouse et al., 1996; Li and Chory, 1997; Hothorn et al., 2011; She et al., 2011). The perception of BR by BRI1 often leads to the recruitment of their co-receptor, BRI1-ASSOCIATED RECEPTOR KINASE 1 (BAK1). Formation of the receptor-co-receptor complex can activate the downstream BR signaling cascade via phosphorylation (Li et al., 2002; Nam and Li, 2002; She et al., 2011). Besides the canonical phytohormone BR, extracellular small peptides can be perceived by RLKs to regulate plant growth and development. For example, CLAVATA 3 (CLV3) can be recognized by its receptor CLV1 to maintain the homeostasis of the SAM. Loss of function of either CLV3 or CLV1 leads to fasciated SAM (Clark et al., 1993, 1997; Fletcher et al., 1999; Trotochaud et al., 2000; Ogawa et al., 2008). EPIDERMAL PATTERNING FACTOR (EPF) and EPF-LIKE (EPFL) family peptides can be sensed by ERECTA family (ERf) RLKs to promote cell proliferation, which determines plant architecture (Shpak et al., 2003; Uchida et al., 2012), stomatal formation and patterning (Shpak et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2012), and SAM homeostasis (Chen et al., 2013; Uchida et al., 2013; Mandel et al., 2014; Kosentka et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021). It has been well established that BAK1 and its homologues, SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASES (SERKs), function as essential co-receptors of many RLK receptors to regulate a variety of plant growth and development processes. For instance, SERKs function with ER, PHLOEM INTERCALATED WITH XYLEM/TRACHEARY ELEMENT DIFFERENTIATION INHIBITORY FACTOR RECEPTOR (PXY/TDR), PHYTOSULFOKINE RECEPTOR 1 (PSKR1), and RGF RECEPTORS/RGF1 INSENSITIVES (RGFRs/RGIs) to control stomatal patterning, vascular development, root growth, and root meristem maintenance, respectively (Meng et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2016; Ou et al., 2016; Song et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Gou and Li., 2020).

Actually, RLKs play crucial roles in regulating many reproductive development processes of plants. Reproduction is a multistage process and relies on the coordination of growth and development through endogenous signals and environmental factors, in which RLKs represent an important type of signaling mediator linking the extracellular signaling molecules and the intracellular signaling components. For example, EXCESS MICROSPOROCYTES1/EXTRA SPOROGENOUS CELLS (EMS1/EXS) functions together with SERK1/2 to sense the microspore mother cell-originated small peptide TAPETUM DETERMINANT 1 (TPD1), which determines the differentiation of the tapetum by activating the downstream core transcription factor BRI1 EMS SUPPRESSOR 1 (BES1) and its homologues (Yin et al., 2002; Jia et al., 2008; Li et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2019). During embryogenesis, GASSHO 1 (GSO1) and GSO2 function with SERKs to perceive the endosperm-processed TWISTED SEED 1 (TWS1) signal, mediating the communications between the embryo and the endosperm to control the cuticle integrity in embryonic epidermal cells (Tsuwamoto et al., 2008; Fiume et al., 2016; Doll et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022). In addition, it was revealed that POLLEN-SPECIFIC RECEPTOR KINASE 3/6 (PRK3/6), MALE DISCOVERER 1 (MDIS1), and MDIS1-INTERACTING RLK 1 (MIK1) play important roles to guide pollen tube growth by sensing the LURE signals during fertilization in Arabidopsis (Takeuchi and Higashiyama, 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017b). Besides the aforementioned leucine-rich repeat (LRR) RLKs, FERONIA (FER), ANXUR1/2 (ANX1/2), and BUDDHA'S PAPER SEAL 1/2 (BUPS1/2), members of the Catharanthus roseus RLK1-like (CrRLK1L) subfamily, play critical roles in mediating male-female recognitions during fertilization (Escobar-Restrepo et al., 2007; Miyazaki et al., 2009; Ge et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2018). Since RLK-mediated male-female recognition and pollen tube guidance have been well summarized recently (Zhong and Qu, 2019; Hafidh and Honys, 2021; Kim et al., 2021), this review mainly focuses on the current understanding of RLK-mediated floral organ morphogenesis, anther differentiation, ovule development, and embryogenesis. The possible open questions worth future investigation are discussed.

RLKs regulate floral meristem identity and floral organ development

Flower development can be divided into several stages according to specific morphological structures. During stage 1 and stage 2, a group of cells start to form the hemispherical floral meristem at the edge of the inflorescence meristem. Then the floral meristem gradually increases its size. At stage 3, an obvious feature is the appearance of the sepal primordia, which elongate to generate the sepals partly overtopping the floral meristem at stage 4 (Figure 1A). At stage 5, the stamen and petal primordia are arising on the flanks of the floral meristem. At stage 6, the sepals completely cover the internal structures. In addition, the floral meristem undergoes terminal differentiation, and the carpels are differentiated at the position of the central zone. During stages 7–9, floral organ development continues and stigma arises at the top of the gynoecium (Figure 1A). During stages 10–12, all floral organs, especially the petals and filaments, rapidly elongate, resulting in petals with similar length to the stamens. Anthesis occurs at stage 13, and the filaments elongate faster than the gynoecium to reach the top of the stigma for self-pollination and successful fertilization of the ovules. During stages 14–19, the siliques and seeds develop to be mature, and the petals and sepals gradually wither (Smyth et al., 1990; Kwiatkowska, 2006) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

RLKs regulate floral meristem identity and floral organ development.

(A) Diagrams showing the process of flower development. At stage 3 (ST3), the sepal primordia begin to form at the edge of the meristem. At ST6, the petal primordia start to form; as the floral meristem terminates, the carpels begin to develop. At ST9, the floral organs in each whorl continue to develop. At ST14, the siliques elongate and the seeds begin to develop after pollination is completed.

(B) RLKs regulate floral meristem and floral organ development. CLV1, CLV2-CRN, and RPK2 recruit CIKs to form receptor-co-receptor complexes that mediate the CLV3-WUS feedback loop signaling to control floral meristem size and termination, and floral organ number. BAM1/2 regulate floral meristem size. ERf members play a role in determining floral meristem size and floral organ morphology. ACR4 regulates sepal morphology. SUB is involved in petal and carpel development. HAE/HSL2 and SERKs form a receptor-co-receptor complex that perceives the IDA signal processed by SBTs to regulate the initiation of floral organ abscission via a MAPK cascade pathway. Putative ligands and co-receptor RLKs are shown in gray. Colored ovals in the extracellular domains of RLKs represent predicted LRR motifs, except ACR4, which is a CR4-L-RLK.

FM, floral meristem; g, gynoecium; pe, petals; se, sepals; st, stamens.

The CLV-WUS pathway regulates floral meristem identity and floral organ development

Successful floral organ production requires strict maintenance and regulation of the floral meristem, which results in proper number of floral organs arranged in normal positions. At stage 1 to stage 2 of flower development, the floral meristem employs regulatory mechanisms similar to those of the SAM. Those genes affecting the size of the SAM usually affect the size of the floral meristem so that they can control the number of floral organs. RLKs play key roles in regulating the floral meristem and the development of floral organs. CLV1 is associated with meristematic activity (Clark et al., 1997). The clv1 mutants display a series of phenotypes, such as enlarged floral meristems, leading to increased number of organs in four floral whorls and even additional whorls (Clark et al., 1993). In addition, in wild-type flowers at stage 6, the pistil primordium is established at the floral meristem, and the floral meristem is terminally differentiated. However, in clv1 flowers at stage 6, the fifth whorl of the floral organ appears in the center where the floral meristem should terminate, and CLV3 continues to be expressed in this extra whorl of the organ (Clark et al., 1993; Fletcher et al., 1999). CLV3, a small secreted polypeptide, is a CLV3/EMBRYO SURROUNDING REGION-related (CLE) family member (Opsahl-Ferstad et al., 1997; Cock and McCormick, 2001). It has been demonstrated that CLV3 can be directly perceived by CLV1 to suppress the expression of WUSCHEL (WUS), an essential homeodomain transcription factor that can diffuse into the central zone of the SAM to promote the expression of CLV3. The CLV-WUS feedback loop thus maintains homeostasis of the SAM (Clark et al., 1993; Fletcher et al., 1999; Schoof et al., 2000; Trotochaud et al., 2000; Yadav et al., 2011). The clv3 mutants show floral meristem defects similar to clv1, suggesting that CLV3 functions together with CLV1 to maintain floral meristem identity through the same CLV-WUS feedback loop (Fletcher et al., 1999; Sun and Ito, 2010; Han et al., 2020).

After floral stage 3, the molecular mechanism regulating floral meristem is obviously different from that of the SAM. During floral stage 3–6, WUS promotes the expression of floral organ-specific AGMOUS (AG) (Lenhard et al., 2001; Lohmann et al., 2001). With floral development, AG and the polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) together begin to inhibit the expression of WUS on the one hand (Liu et al., 2011). On the other hand, AG begins to gradually induce the expression of KNUCKLES (KNU), a C2H2-type zinc finger repressor that further recruits PRC2 to inhibit the expression of WUS (Sun et al., 2009, 2014, 2019). Finally, when the flower develops to stage 6, the floral meristem is terminally differentiated, and the carpels begin to develop. A recent study showed that KNU can directly inhibit the expression of CLV1 and CLV3 during floral meristem determinacy. In addition, KNU can interact with WUS to inhibit CLV3 expression in the central zone, and the KNU-WUS interaction interrupts the WUS homodimers and WUS-HAIRYMERISTEM 1 heterodimers, resulting in the termination of the floral meristem (Shang et al., 2021). In the wild type, the expression of WUS can be timely repressed by KNU to terminate the floral meristem and initiate the carpels (Ming and Ma, 2009; Sun et al., 2009, 2014, 2019). However, why the clv floral meristem cannot carry out timed termination is largely unknown. One possibility is that the clv floral meristem may partially acquire the identity of the SAM (Clark et al., 1993). It is worth noting that CLV1 has three homologues, namely BARELY ANY MERISTEM 1/2/3 (BAM1/2/3). Although the clv-related mutants exhibit an increased number of floral organs, the bam1/2/3 triple mutants show a decreased number of stamens and carpels and a smaller floral meristem when compared with the wild type (DeYoung et al., 2006; Deyoung and Clark, 2008), indicating that the functions of CLV1 and BAM1/2/3 differentiate in maintaining meristem homeostasis (Figure 1B; Table 1). A recent study may help us to understand how BAM1/2/3 and CLV1 differentially regulate meristem homeostasis. CLE40 and CLV3 are closely related secreted small peptides that are required to coordinate homeostasis of the shoot stem cells. The expression patterns of CLV3 and CLE40 are complementary; i.e., CLV3 is expressed in the center zone, and CLE40 is expressed in the peripheral zone of the SAM. Consistently, CLV1 and BAM1, the receptors of CLV3 and CLE40, are expressed in the organizing center and the meristem region except the organizing center, respectively. The CLE40-BAM1 signaling pathway promotes the expression of WUS, and the CLV3-CLV1 signaling pathway inhibits the expression of WUS, coordinately maintaining the homeostasis of the SAM (Schlegel et al., 2021). Therefore, differential expression of ligands and their corresponding receptors and different ligand-receptor pairs possibly provide an effective way to finely regulate meristem homeostasis.

Table 1.

Receptors, co-receptors, and ligands regulating plant reproductive development.

| Ligand | Receptor | Subfamily | Co-receptor/RLCK | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLV3 | CLV1 | LRR XI-RLK | CIKs | floral meristem size floral meristem termination floral organ number anther lobe development anther morphogenesis |

Clark et al. (1993), Clark et al. (1997), Fletcher et al. (1999), Trotochaud et al. (2000), Sun and Ito (2010), Cui et al. (2018), Hu et al. (2018), Han et al. (2020) and Shang et al. (2021) |

| CLV3 | CLV2 | RLP | CIKs, CRN | Kayes and Clark (1998), Jeong et al. (1999), Müller et al. (2008) and Bleckmann et al. (2010) | |

| CLV3 | RPK2 | LRR XV-RLK | CIKs | floral meristem size floral meristem termination floral organ number |

Kinoshita et al. (2010) and Hu et al. (2018) |

| ? | RPK2 | LRR XV-RLK | CIKs | archesporial cell division primary parietal cell and inner secondary parietal cell division and differentiation anther dehiscence |

Mizuno et al. (2007) and Cui et al. (2018) |

| ? | RPK1/TOAD2 | LRR XV-RLK | ? | radial pattern formation hypophysis differentiation cotyledon initiation |

Nodine et al. (2007), Nodine and Tax (2008), Luichtl et al. (2013) and Fiesselmann et al. (2015) |

| ? | BAM1/2/3 | LRR XI-RLK | ? | floral meristem size | DeYoung et al. (2006) |

| ? | BAM1/2 | LRR XI-RLK | CIKs | archesporial cell division and differentiation | Hord et al., (2006) and Cui et al. (2018) |

| EPFL2/9 | ER/ERL1/2 | LRRXIII-RLK | ? | ovule and seed density | Kawamoto et al. (2020) |

| EPFL2 | ER/ERL1/2 | LRRXIII-RLK | ? | cotyledon development | Chen and Shpak (2014) and Fujihara et al. (2021) |

| ? | ER/ERL1/2 | LRRXIII-RLK | ? | floral meristem size floral organ morphology anther lobe development integument and embryo sac development |

Shpak et al. (2004), Pillitteri et al. (2007), Hord et al. (2008), Bemis et al. (2013) and Mandel et al. (2014) |

| ? | ER/ERL1/2 | LRR XIII-RLK | BSK1/2 | zygote polarization suspensor development |

Neu et al. (2019) and Wang et al. (2021) |

| / | / | / | SSP | zygote polarization suspensor development |

Bayer et al. (2009) and Neu et al. (2019) |

| ? | ACR4 | CR4-L-RLK | ? | sepal development integument development epidermal development |

Gifford et al. (2003) and Tanaka et al. (2007) |

| ? | SUB | LRR V-RLK | ? | petal and carpel development outer integument development |

Chevalier et al. (2005) |

| IDA | HAE/HSL2 | LRR XI-RLK | SERKs | floral organ abscission | Jinn et al. (2000), Butenko et al. (2003), Cho et al. (2008), Stenvik et al. (2008), Meng et al. (2016) and Santiago et al., 2016 |

| / | EVR/SOBIR1 | LRR XI-RLK | / | floral organ abscission | Leslie et al. (2010) |

| / | / | RLCK VII | CST | floral organ abscission | Burr et al. (2011) |

| TPD1 | EMS1/EXS | LRR X-RLK | SERK1/2 | tapetum identity microspore mother cell development |

Zhao et al. (2002), Canales et al. (2002), Yang et al. (2003), Albrecht et al. (2005), Colcombet et al. (2005), Jia et al. (2008) and Li et al. (2017) |

| ? | EMS1/EXS | LRR X-RLK | ? | seed size | Canales et al. (2002) |

| BR | BRI1 | LRR X-RLK | SERKs | tapetum and pollen development ovule and seed number outer integument development |

Ye et al. (2010), Huang et al. (2013) and Jia et al. (2020) |

| ? | ? | ? | SERKs | vascular precursor division ground tissue stem cell division |

Li et al. (2019) |

| ? | AtVRLK1 | LRR VIII-RLK | ? | anther dehiscence | Huang et al. (2018) |

| ? | ALE2 | extensin RLK | ? | integument development embryo sac development epidermal development |

Tanaka et al. (2007) |

| ESF1 | ? | ? | ? | embryo development suspensor elongation |

Costa et al. (2014) |

| ? | ZAR1 | LRRIII-RLK | zygotic division | Yu et al. (2016) | |

| KRS | ? | ? | ? | embryo sheath formation embryo-endosperm separation |

Moussu et al. (2017) |

| TWS1 | GSO1/2 | LRR XI-RLK | SERKs | embryonic cuticle integrity | Tsuwamoto et al. (2008), Fiume et al. (2016), Doll et al. (2020) and Zhang et al. (2021b) |

CLV2, a receptor-like protein (RLP), consists of an extracellular domain and a transmembrane domain, but lacks a kinase domain. Loss of CLV2 function leads to enlarged floral meristem and over-production of floral organs (Kayes and Clark, 1998; Jeong et al., 1999). CORYNE (CRN) is a plasma membrane-localized receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase (RLCK). CLV2 and CRN form a receptor complex that can also transduce the CLV3 signal to maintain the floral meristem (Müller et al., 2008; Bleckmann et al., 2010). RECEPTOR-LIKE PROTEIN KINASE 2/TOADSTOOL 2 (RPK2/TOAD2) is another key RLK component for meristem maintenance. The rpk2 mutants show expanded stem cells and increased number of carpels. Although the rpk2 single mutant exhibits a weaker phenotype with abnormal floral organ number when compared with clv1, clv2, and crn, all of the clv1-101 rpk2-2, clv2-101 rpk2-2, and clv1-101 clv2-101 double mutants exhibit more severe floral meristem defects than the clv1, clv2, and rpk2 single mutants, with increased carpels similar to the clv3-8 mutant. In addition, biochemical results indicated that RPK2 forms homo-oligomers, which are independent of CLV1 or the CRN-CLV2 complex. Therefore, CLV1, CLV2-CRN, and RPK2 independently mediate the CLV3-WUS pathway to regulate floral meristem and floral organ development (Kinoshita et al., 2010) (Figure 1B; Table 1).

In recent years, a group of homologous genes, named CLAVATA3 INSENSITIVE RECEPTOR KINASES (CIKs), were found to have essential roles in regulating CLV3-mediated stem cell homeostasis. The cik1/2/3/4 quadruple mutants exhibit a series of phenotypes similar to the clv mutants, such as enlarged SAM and more flowers and floral organs. In addition, CLV3 can induce the phosphorylation of CIKs, and the cik1/2/3/4 quadruple mutants are insensitive to exogenously applied CLV3. Genetic and biochemical analyses revealed that CIKs play a critical role in the CLV-WUS feedback pathway (Hu et al., 2018). The phenotype of abnormally increased number of carpels in the cik1/2/3/4 quadruple mutants is more severe than that of the clv3, clv1, clv2, and rpk2 mutants, but similar to the clv1-20 cik1/2/3/4, clv2-101 cik1/2/3/4, and rpk2-1 cik1/2/3/4 mutants. Moreover, CIKs can interact with CLV1, CRN, and RPK2, and can be phosphorylated by CLV1 and CRN (Hu et al., 2018). Therefore, it is possible that CIKs function as co-receptors of CLV1, CLV2-CRN, and RPK2 to mediate the CLV3 signal in regulating floral meristem and floral organ development (Figure 1B; Table 1).

It has been revealed that the CLV-WUS signaling pathway is conserved in plants. Loss of function of FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER 1 (FON1), a rice (Oryza sativa) RLK similar to CLV1 in Arabidopsis, leads to an enlarged floral meristem and increased floral organ number (Suzaki et al., 2004). FON4, also referred to as FON2, is a putative ortholog of Arabidopsis CLV3. Similarly, the fon4 mutants show increased number of floral organs (Chu et al., 2006; Suzaki et al., 2006). In tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.), mutations of FASCIATED AND BRANCHED (FAB) and FASCIATED INFLORESCENCE (FIN) cause enlarged meristems that can produce larger fruits. FAB is the ortholog gene of CLV1, and FIN encodes an arabinosyltransferase that is essential for CLV3 glycosylation (Xu et al., 2015). In maize (Zea mays), the thick tassel dwarf1 (td1) mutants display increased tassel spikelet density, increased ear inflorescence meristem size, and larger kernel row number, which is caused by a mutation in the maize ortholog of CLV1 (Bommert et al., 2005). Since mutations of CLV genes result in enlarged floral meristem, these genes are potential targets that can be utilized to increase production in agriculture.

Other RLKs regulating floral meristem identity and floral organ development

ERf RLKs, including ER, ER-LIKE 1 (ERL1), and ERL2 in Arabidopsis, regulate floral meristem and floral organ development. Loss of function of ERf genes results in distorted and asymmetrical floral meristem with off-center expressed CLV3 and carpelloid sepals, indicating that ERf RLKs are involved in the regulation of floral meristem and floral organ identity (Bemis et al., 2013; Mandel et al., 2014). Although the er-3 single mutant shows slightly enlarged floral meristems, loss of function of ER can enhance the floral meristem defects of clv mutants, suggesting that ER regulates floral meristem independent of the CLV signaling pathway (Durbak and Tax, 2011; Mandel et al., 2014) (Figure 1B; Table 1).

STRUBBELIG/SCRAMBLED (SUB/SCM), another LRR-RLK without kinase activity, plays an important role in controlling floral organ shape and size (Chevalier et al., 2005; Kwak et al., 2005; Yadav et al., 2008). The sub mutants generate twisted petals and carpels, fused two neighboring sepals as well as unfused carpels, which may be caused by abnormal cell morphogenesis in sub. Petals and stamens of the sub mutant are fewer than the wild type. In addition, the sub mutants generate abnormal petals with sepal or anther characteristics, indicating that SUB may be involved in establishing the petal identity in Arabidopsis (Chevalier et al., 2005). However, other signaling molecules involved in SUB-mediated floral development have not been identified yet (Figure 1B; Table 1).

Besides the aforementioned LRR-RLKs, some non-LRR-RLKs are required to regulate floral development. For example, ARABIDOPSIS CRINKLY 4 (ACR4) plays a role in regulating sepal morphology. ACR4 is mainly expressed in the outer cells of most developing organs, such as the embryo, ovule, apical meristem, and inflorescence meristem. Although there are not major defects in sepals, the acr4 mutants show disordered arrangement of cells at the sepal margins (Gifford et al., 2003) (Figure 1B; Table 1).

HAE and HSL2 regulate floral organ abscission

In the wild type, the senescent floral organs usually fall off after they complete their functions. In Arabidopsis, at stage 17 of flower development, the senescent floral organs abscise from the receptacle, a process called abscission, which requires HAESA (HAE) and HAESA-like 2 (HSL2), two closely related LRR-RLKs (Jinn et al., 2000; Cho et al., 2008). HAE is mainly expressed in the abscission zones where the sepals, petals, and stamens attach to the receptacle. Mutation of HAE and HSL2 leads to impaired floral organ abscission so that the senescent sepals, petals, and stamens cannot abscise in time (Jinn et al., 2000; Cho et al., 2008). Abscission defects of floral organs occur when INFLORESCENCE DEFICIENT IN ABSCISSION (IDA), which encodes a small secreted peptide, is impaired. The floral organs of ida mutants remain attached to the receptacle after the siliques mature, similar to that of hae hsl2. In contrast, over-expression of IDA leads to earlier abscission of the floral organs (Butenko et al., 2003; Stenvik et al., 2006). The mature and active IDA peptides need to be processed from the IDA precursors by three subtilisin-like proteinases (SBTs), SBT4.12, SBT4.13, and SBT5.2 (Schardon et al., 2016). Over-expression of IDA or exogenous application of synthetic IDA peptides cannot rescue the abscission deficiency of hae hsl2, demonstrating that IDA acts through HAE/HSL2 to regulate floral organ abscission (Stenvik et al., 2008). Biochemical and structural biology results further confirmed that IDA functions as a ligand of HAE and HSL2 in regulating floral organ abscission (Santiago et al., 2016). It has been revealed that SERKs are employed to be co-receptors of HAE and HSL2. High-order serk mutants exhibit floral organ abscission defects similar to ida and hae hsl2. Moreover, IDA can significantly enhance the interactions between HAE/HSL2 and SERKs (Meng et al., 2016; Santiago et al., 2016). After the HAE/HSL2-SERK receptor complex perceives the IDA signal, a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade consisting of MAPK kinase 4/5 (MKK4/5) and MPK3/6 is triggered and transduces the signal to the nucleus, thus inducing separation between abscission zone cells (Cho et al., 2008). The MAPK cascade further suppresses the function of BREVIPEDICELLUS (BP)/KNOTTED-LIKE FROM ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA1 (KNAT1), which inhibits floral organ cell separation, and promotes expression of KNAT2 and KNAT6 to induce floral organ abscission (Shi et al., 2011) (Figure 1B; Table 1).

Membrane trafficking of receptor kinases likely plays a critical role in modulating signaling during development (Geldner and Robatzek, 2008). It was reported that an ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein, named NEVERSHED (NEV), regulates floral organ abscission through modulating membrane trafficking. Loss of function of two LRR-RLKs, EVERSHED/SUPPRESSOR OF BIR1 1 (EVR/SOBIR1) and SERK1, can restore floral organ shedding in the nev mutant (Leslie et al., 2010; Lewis et al., 2010). In addition, loss-of-function CAST AWAY (CST), a membrane-associated RLCK, can suppress the defective floral organ abscission of the nev mutant. However, mutation of EVR, SERK1, or CST cannot restore floral organ abscission of the ida or hae hsl2 mutants. CST forms a complex with HAE and EVR to regulate floral organ shedding through membrane trafficking (Burr et al., 2011). Floral organs of the serk1/2/3 triple mutants cannot normally abscise (Meng et al., 2016), whereas additional serk1 mutation can restore floral organ abscission of the nev mutant (Lewis et al., 2010), suggesting that SERK1 may play different roles in multiple pathways to regulate floral organ abscission. How the NEV-EVR-SERK1-CST pathway and the IDA-HAE/HSL2-SERK signaling coordinately regulate floral organ abscission needs to be explored next. Whether turnover of HAE/HSL2 by NEV-mediated membrane trafficking regulates floral organ abscission is worthy of further investigation.

RLKs regulate anther development

In Arabidopsis, the stamen primordium begins to initiate in the flower at stage 5. The anther primordium includes three layers of cells from outside to inside. The outer L1 layer develops to form the anther epidermis. The L2-derived cells differentiate to form the archesporial cells, finally forming the pollen and the parietal cell layers. Cells of the L3 layer differentiate to form the vascular and connective tissue linking four lobes in the anther (Hord et al., 2006). With division and differentiation of the stamen primordium cells, the L2-derived archesporial cells are formed in the four corners of the anther at stage 2 of anther development (Figure 2A). The archesporial cells undergo two rounds of periclinal cell division, forming two layers of parietal cells outward, and the sporogenous cells inward. The sporogenous cells further differentiate to form the microspore mother cells. At stage 5 of anther development, a typical period of early anther development, each lobe contains the epidermis, endothecium, middle layer, tapetum, and microspore mother cells from outside to inside (Chang et al., 2011). It is worth noting that the parietal cells adjacent to the connective tissue in each lobe are formed by differentiated surrounding cells induced by the sporogenous cells (Sanders et al., 1999; Scott et al., 2004; Ma, 2005). After stage 6 of anther development, the microspore mother cells undergo meiosis to form microspores that form mature three-cell pollen grains after two rounds of mitosis. At the same time, the tapetum layer is degenerated, the endothecium is lignified and thickened, and mature pollen grains are finally released (Sanders et al., 1999; Ma, 2005; Schmidt et al., 2015) (Figure 2A).

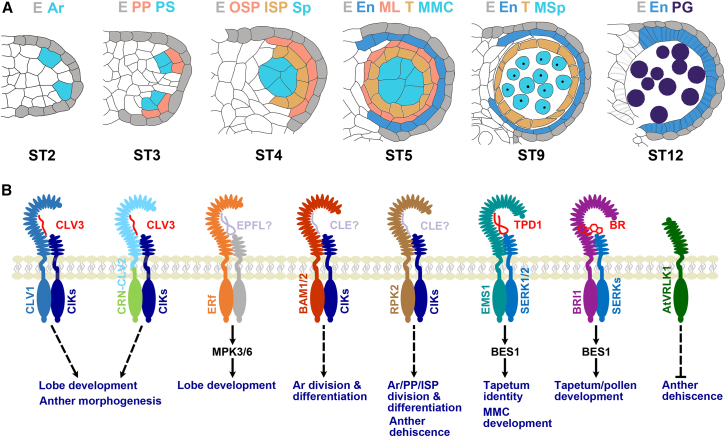

Figure 2.

RLK regulates anther development.

(A) Diagrams showing the process of anther development. At ST2, the archesporial cells are formed at four corners of the anther. At ST3, the archesporial cells divide periclinally to produce the primary sporogenous cells and primary parietal cells. At ST4, the primary parietal cells divide to generate the inner and outer secondary parietal cells. At ST5, the inner secondary parietal cells divide to generate the middle layer and tapetum. At ST9, the middle layer degenerates and the pollen wall begins to develop. At ST12, mature pollen grains are formed and the endothecium is lignified and thickened.

(B) RLKs regulate anther development. CLV1 and CLV2-CRN recruit CIKs to form the receptor-co-receptor complexes that may sense CLV3 to regulate anther morphogenesis and lobe development. ERf members function with MPK3/6 to regulate lobe development. The BAM1/2-CIK receptor-co-receptor complex determines archesporial cell division and differentiation. The RPK2-CIK receptor-co-receptor complex regulates archesporial cell division, primary parietal cell and inner secondary parietal cell division and differentiation, and anther dehiscence. The TPD1-EMS1-SERK1/2 signaling activates BES1 family transcription factors to determine tapetum identity and microspore mother cell development. BRI1 and SERKs mediate BR signaling to regulate the development of tapetum, microspores, and pollen. AtVRLK1 is involved in anther dehiscence. Colored ovals in the extracellular domains of RLKs represent predicted LRR motifs. Putative ligands and co-receptor RLKs are shown in gray.

Ar, archesporial cell; E, epidermis; En, endothecium; ISP, inner secondary parietal cell; ML, middle layer; MMC, microspore mother cell; MSp, microspores; OSP, outer secondary parietal cell; PG, pollen grains; PP, primary parietal cell; PS, primary sporogenous cell; Sp, sporogenous cell; T, tapetum.

RLKs regulate morphogenesis of anther lobe

The LRR-RLK family members play key roles in anther development. It is well known that the CLV signaling pathway regulates meristem homeostasis. CLV genes also regulate anther morphogenesis. The clv3, clv1, and cik1/2/3/4 mutants generate some anthers lacking one or two lobes, and some club-shaped anthers missing all lobes (Cui et al., 2018). Club-shaped anthers also occur in crn mutants (Müller et al., 2008). The clv2 mutants produce some defective anthers with only three lobes (Kayes and Clark, 1998). These defects suggest that the CLV genes may be necessary for early anther development at stage 1 to stage 2. Although the CLV signaling pathway inhibits expression of WUS in the process of meristem maintenance, the wus mutants produce defective anthers lacking one or two lobes (Deyhle et al., 2007), similar to the clv and cik mutants, suggesting that the mechanism regulating anther morphogenesis by CLV signaling may be different from that of CLV-WUS-mediated meristem maintenance (Figure 2B; Table 1).

Early anther lobe development requires ERf members (Shpak et al., 2004; Hord et al., 2008). Although no obvious anther defects can be observed before stage 3, the er-105 erl1-2/2-1 triple mutants produce defective anthers lacking one or more lobes, and the developed lobes exhibit abnormal cell division and differentiation, which eventually leads to complete sterility. Similar to the er-105 erl1-2/2-1 triple mutants, the mpk3/+ mpk6/– mutants also generate anthers lacking one or more lobes. Therefore, ERf and MPK3/6 may function in the same pathway to regulate early anther development (Hord et al., 2008). SPOROCYTELESS/NOZZLE (SPL/NZZ), a key transcription factor involved in early anther development (Schiefthaler et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999; Wei et al., 2015), can interact with and be phosphorylated by MPK3/6. The phosphorylation can enhance the stability of SPL, which is important for the initiation of the archesporial cells in the adaxial anther lobes (Zhao et al., 2017). In spite of the fact that some EPF and EPFL peptides function as ligands of ERf members to regulate various developmental processes, such as stomatal patterning, inflorescence architecture, and ovule numbers (Lee et al., 2012; Uchida et al., 2012; Kawamoto et al., 2020), EPFLs that may act as ERf ligands regulating early anther development have not been clarified. On the other hand, it has been revealed that SERKs function as co-receptors of ERf to regulate stomatal development (Meng et al., 2015). However, what co-receptor RLKs are recruited by ERf to regulate early anther development are still unknown. It is worth investigating whether EPFLs and SERKs are key components of the ERf-MPK3/6-SPL signaling module to regulate anther lobe morphogenesis in the near future (Figure 2B; Table 1). OsER, an ortholog of ERf in rice, is involved in the establishment of anther lobes (Liu et al., 2021), suggesting that ERf functions in regulating early anther development are possibly conserved in dicots and monocots.

RLKs regulate anther locule development

After the establishment of lobes in early anthers, several LRR-RLKs are required for appropriate differentiation of the archesporial cells and formation of the parietal cells. The bam1/2 double mutants exhibit disordered division and differentiation of the L2-derived cells, which results in anthers lacking the endothecium, middle layer, and tapetum and generating more microspore mother cell-like cells (Hord et al., 2006), indicating that BAM1/2 determine the fate of the archesporial cells and then their division and differentiation patterns. RPK2/TOAD2 is required to control division and differentiation of the archesporial cells. The archesporial cells divide anticlinally in rpk2-1 anthers, leading to defective locules without parietal cells (Cui et al., 2018). Besides, RPK2 plays a critical role in regulating divisions of the primary parietal cells and the inner secondary parietal cells. Most rpk2 anthers generate locules without the middle layer or lacking two parietal cell layers, together with abnormally hypertrophic tapetal cells, and inadequately thickened and lignified endothecium cells, finally failing to produce and release functional pollen grains (Mizuno et al., 2007; Cui et al., 2018) (Figure 2B; Table 1).

A paradigm has been well established that the ligand-binding RLKs usually recruit other RLKs as co-receptors to transduce the perceived signals (Gou and Li, 2020). Although SERKs play crucial roles as co-receptors in a variety of biological processes, no evidence supports that they function as co-receptors of BAM1/2 and RPK2 to control division and differentiation of the archesporial cells. A recent study revealed that CIKs determine the fate of the archesporial cells (Cui et al., 2018). Anthers of the cik1/2/3 triple mutants and cik1/2/3/4 quadruple mutants generate defective archesporial cells, primary parietal cells, and secondary parietal cells with abnormal division and differentiation, eventually resulting in excess microspore mother cells and lack of one to three parietal cell layers in anther locules. These anther phenotypes are similar to those of the bam1/2 and rpk2-1 mutants. Genetic and biochemical results demonstrated that CIKs function with BAM1/2 or RPK2 in a common pathway. Therefore, CIKs act as co-receptors of BAM1/2 and RPK2, and function together to regulate archesporial cell division and parietal cell formation during early anther development (Figure 2B; Table 1). However, the ligand signals mediated by the BAM-CIK and RPK2-CIK complexes and the key downstream factors remain to be explored. Studies have shown that the BAM family members mediate several CLE signals to maintain stem cell homeostasis and regulate drought resistance and root protophloem development (Shinohara and Matsubayashi, 2015; Takahashi et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2022). In addition, RPK2 mediates CLE signals to regulate stem cell homeostasis and root protophloem differentiation (Kinoshita et al., 2010; Gujas et al., 2020). Therefore, it is possible that a class of CLE ligands can be recognized by the BAM1/2-CIK and RPK2-CIK complexes to regulate early anther development.

Proper division and differentiation of the microspore mother cells and parietal cells in early anthers require EMS1/EXS (Canales et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2002). The ems1 anthers exhibit abnormally increased microspore mother cells and dysfunctional middle layer, and lack the tapetum. Although the microspore mother cells in the ems1 mutants can complete meiosis, they cannot undergo cytoplasmic division, thus causing anther abortion. However, no female defects were reported in ems1. As EMS1 regulates an important and conserved biological process, it is not surprising that MULTIPLE SPOROCYTE 1 (MSP1), an ortholog of EMS1, exists in monocot rice (Nonomura et al., 2003). The msp1 mutants cannot differentiate the tapetum, and they not only generate abnormally increased microspore mother cells and disordered anther wall cell layers but also produce abnormally increased megaspore mother cells. Eventually, both male and female are abortive in msp1. Therefore, EMS1 and its orthologs may possess differentiated functions during reproductive development in dicots and monocots. The serk1/2 double mutant anthers are completely abortive for lack of the tapetum and abnormally increased microspore mother cells, which is similar to the ems1/exs mutants (Albrecht et al., 2005; Colcombet et al., 2005). Unsurprisingly, GhSERK1, an ortholog of SERKs in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), has a role in regulating pollen production, although whether it regulates tapetum differentiation is not known (Shi et al., 2014).

TAPETUM DETERMINANT 1 (TPD1) is a small cysteine-rich peptide that can be secreted outside of the cell and specifically determines the formation of the tapetum (Yang et al., 2003, 2005). In the tpd1 mutant, the precursor cells that should have formed the tapetum differentiate into microspore mother cells. As a result, the microspore mother cells are abnormally increased and the tapetum is missing. TPD1-like 1A/MICROSPORELESS 2 (OsTDL1A/MIL2) is an orthologous gene of TPD1 in rice. The ostdl1 mutants generate primary parietal cells that are unable to divide and differentiate to form the secondary parietal cells, resulting in the absence of the middle layer and tapetum, and abnormally increased microspore mother cells (Zhao et al., 2008; Hong et al., 2012). Mutation of MULTIPLE ARCHESPORIAL CELLS 1 (MAC1), an orthologous gene of TPD1 in maize, leads to the absence of the tapetum and increased archesporial cells (Wang et al., 2012). Although all of TPD1, OsTDL1A, and MAC1 function as small peptides to regulate anther parietal cell differentiation, it looks like their functions take place at different stages during early anther development.

The ems1, serk1/2, and tpd1 mutants exhibit very similar defects of parietal cell differentiation, suggesting that they regulate early anther development in a common signaling pathway (Zhao et al., 2002; Canales et al., 2002; Ma et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2003). This conclusion is supported by several other lines of evidence. Ectopic expression of TPD1 causes abnormal increase of somatic cell layers in the wild-type anthers but not in the serk1/2 mutants, indicating that TPD1 functions through SERK1/2 to regulate anther wall cell differentiation. Moreover, ems1-1, serk1-1/2-1, and ems1-1 serk1-1/2-1 exhibit similar parietal cell defects, indicating that EMS1, SERK1/2, and TPD1 function in the same genetic pathway (Li et al., 2017). Furthermore, TPD1 can bind to the extracellular LRR region of EMS1 and induce phosphorylation of EMS1 (Jia et al., 2008). Transphosphorylation occurs between EMS1 and SERK1 (Li et al., 2017). Taken together, the sporogenous cell- and microspore mother cell-secreted TPD1 ligands are recognized by the EMS1-SERK receptor-co-receptor complex to determine tapetum formation and microspore mother cell development. Recently, BES1 and its homologous transcription factors were identified to be the key signaling components downstream of TPD1-EMS1-SERK1/2 to determine the development of the tapetum and microspore mother cells in early anthers (Chen et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2019) (Figure 2B; Table 1). Ectopic expression of BRI1 in the tapetum of ems1 can partially restore the lacked tapetum in ems1. In addition, co-expression of TDP1 and EMS1 by a BRI1 promoter in the bri1-116 mutant can activate BES1 and finally suppress the defects of bri1-116, whereas co-expressed TDP1 and EMS1 cannot rescue the BR signaling defects of bin2-1D, a mutant with activated BIN2 that represses BRI1-mediated BR signaling. Furthermore, the bzr1-D and bes1-D mutations with activated BR signaling can rescue the tapetum defects of tpd1 and ems1 anthers. Therefore, the TPD1-EMS1-SERK1/2 signaling pathway shares the same downstream key factors of the BR-BRI1-SERK signaling pathway to regulate tapetum differentiation (Zheng et al., 2019), suggesting that very similar or even the same signaling module can be employed by different ligand-RLK pairs to regulate distinct biological processes during evolution.

As a downstream key transcription factor in response to BR signaling (Yin et al., 2002), BES1 can directly regulate the expression of SPL/NZZ, TAPETUM DEVELOPMENT AND FUNCTION 1 (TDF1), ABORTED MICROSPORES (AMS), MALE STERILITY 1 (MS1), and MS2, key genes involved in anther development. Consistently, BRI1, the major BR receptor, regulates the development of tapetum, microspores, and pollen. The bri1-116 mutants show abnormal tapetum, defective pollen grain release, and distorted exine pattern formation, resulting in reduced fertility (Ye et al., 2010) (Figure 2B; Table 1).

Other RLKs regulating anther development

Several RLKs have been identified in Arabidopsis and rice to regulate other aspects of anther development. For example, AtVRLK1, an LRR-RLK, is expressed in cells with secondary cell wall thickening, and upregulation of AtVRLK1 affects anther dehiscence in Arabidopsis (Huang et al., 2018) (Figure 2B; Table 1). Rice LRR II-RLK family members THERMO-SENSITIVE GENIC MALE STERILE 10 (TMS10) and TMS10-LIKE (TMS10L) redundantly control tapetal degeneration and pollen viability. The tapetal development and pollen fertility are sensitive to higher environmental temperature in the tms10 mutants (Yu et al., 2017). DWARF AND RUNTISH SPIKELET1 (DRUS1) and DRUS2, two rice CrRLKs orthologous to FER, redundantly sustain anther development by repressing cell death and regulate pollen maturation by affecting sugar utilization in rice (Pu et al., 2017). OsLecRK5, a lectin receptor-like protein kinase, phosphorylates the callose synthesis enzyme UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase 1 (UGP1) to promote its activity in callose biosynthesis during meiosis of the microspore mother cells in rice anthers (Wang et al., 2020). Unfortunately, the detailed signaling pathways mediated by these RLKs still need to be deciphered. Since anther development is a complex process requiring numerous communications among anther cells, it will not be surprising if more RLKs involved in anther development are identified in the future.

RLKs mediate ovule development

Following the development of four-whorled floral organs, two carpels of the pistil are closed. The ovule begins to develop in the carpel, and eventually an embryo sac is generated in the mature ovule with an inner and an outer integument (Gasser et al., 1998; Yang et al., 2010; Endress, 2011). The ovule primordium is initiated in the subepidermal tissue of carpel margin meristem. Following division and differentiation of the ovule primordium cells, the ovule primordium elongates, and an archesporial cell appears under the epidermis at the top of the ovule (Figure 3A). The archesporial cell further differentiates to form a megaspore mother cell whose morphology is significantly different from that of the surrounding cells. The megaspore mother cell undergoes meiosis to form four megaspores, and the three megaspores at the end of the micropylar undergo programmed cell death and finally degenerate. The megaspore located at the chalazal end develops into the functional megaspore. With the development, the ovule gradually increases its volume, and the functional megaspore produces two daughter nuclei through a nuclear division, and the two daughter nuclei are separated by a central vacuole. The daughter nuclei located on both sides of the central large vacuole undergo two nuclear divisions to form an eight-nucleus embryo sac. Then, one daughter nucleus from each end of the embryo sac moves to the center and fuses to form the central nucleus. At the same time, each nucleus is cellularized to establish a cell structure. The final embryo sac consists of three antipodal cells at the chalazal end, a diploid central cell, two synergids, and an egg cell at the micropylar end. With the development of the embryo sac, the ovule starts to develop the inner and outer integuments coordinately (Yang et al., 2010; Schmidt et al., 2015) (Figure 3A). The inner integument is developed around the nucellus, and the outer integument develops to wrap the inner integument and the nucellus. Finally, the inner and outer integuments completely cover the nucellus and the embryo sac, with only a narrow opening at the micropyle end, which is the channel for the pollen tube to enter and complete the fertilization process (Yang et al., 2010) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

RLKs mediate ovule development.

(A) Diagrams showing the process of ovule development. ST1-II is ovule primordium initiation and elongation. At ST2-III, the integument initiates to development. At ST2-V, the integument is stretched to the top of the nucellus. At ST3-VI, the ovule generates an embryo sac wrapped by the inner and outer integuments.

(B) RLKs regulate ovule development. ERf members regulate initiation patterns of the ovule primordium and development of the integument and embryo sac. The BR signaling pathway is involved in the determination of ovule number and outer integument development. ACR4 regulates integument development. ALE2 controls integument and embryo sac development. SUB regulates outer integument development. Colored ovals in the extracellular domains of RLKs represent predicted LRR motifs except the CR4-L-RLK ACR4 and the extensin RLK ALE2. Putative ligands and co-receptor RLKs are shown in gray.

es, embryo sac; i, integument; ii, inner integument; n, nucellus; oi, outer integument.

ERf- and BRI1-mediated signaling pathways regulate ovule density and number

The initiation patterns of the ovule primordium are strictly monitored by ERf RLKs. ERf members promote fruit elongation, which requires the EPFL9 ligand from the valves. The er mutants generate short fruits with higher seed density when compared with the wild type. Consistently, the EPFL9 RNAi plants show decreased fruit length with a higher seed density. In contrast, ERL1 and ERL2 regulate spacing of ovules, which depends on the EPFL2 ligand. Both epfl2-1 and erl1-2/2-1 mutants develop shorter fruits with a lower seed density (Kawamoto et al., 2020) (Figure 3B; Table 1).

Ovule and seed numbers are regulated by the BRI1-mediated BR signaling pathway (Huang et al., 2013). Impaired BR biosynthesis and signaling in the det2 and bri1-5 mutants result in decreased ovule and seed counts, whereas loss function of BIN2, a negative BR regulator, leads to increased ovule and seed numbers. As one of the core transcription factors in BR signaling, BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT 1 (BZR1) plays a key role in ovule and seed number determination (Huang et al., 2013). Consistently, the BR gain-of-function mutant bzr1-1D produces more ovules and seeds (Figure 3B; Table 1).

RLKs regulate integument development

Besides the ovule number and density, ERf- and BRI1-mediated signaling pathways play critical roles in regulating integument development. Mature er-105 erl1-2 erl2-1/+ ovules display aberrant morphology, with dramatically compromised inner and outer integuments (Pillitteri et al., 2007). It was reported that ERf regulates inflorescence architecture, stomatal patterning, and anther development through the MAPK cascades (Shpak et al., 2003, 2005; Hord et al., 2008). Interestingly, MPK3/6 are involved in ovule development. In the mpk3/+ mpk6 mutants, the integuments are abnormally developed and cannot wrap the nucellus, leading to failure of the embryo sac (Wang et al., 2008). In addition, EPF and EPFL peptides are perceived by ERf members to regulate inflorescence architecture, stomatal patterning, and ovule and seed density (Lee et al., 2012; Uchida et al., 2012; Kawamoto et al., 2020). The similar integument defects between er-105 erl1-2 erl2-1/+ and mpk3/+ mpk6 suggest that ERf may perceive as-yet unknown EPF/EPFL peptides to regulate integument development through the MAPK signaling cascade (Figure 3B; Table 1). Different from ERf-mediated signaling, BRI1-mediated BR signaling plays an important role in regulating development of the outer integument (Jia et al., 2020). The outer integument in null bri1-116 and bri1-701 brl1/3 is not fully developed and cannot cover the inner integument and the nucellus. In addition, both bri1-116 and bri1-701 brl1/3 generate similarly defective outer integuments, indicating that BRI1 is the dominant player in mediating BR signaling to regulate outer integument development. Consistently, the dominant gain-of-function mutation bzr1-1D can partially restore the abnormal outer integument phenotype in bri1-116. The key transcription factor INNER NO OUTER (INO), which regulates the development of the outer integument, is significantly downregulated in bri1-116, and INO expression can be induced by BZR1 (Villanueva et al., 1999; Jia et al., 2020). The sextuple mutant of BZR1 family genes generates outer integument arrested immediately after initiation, which is more severe than that of null bri1 mutants, suggesting that the outer integument development is regulated by the BRI1-mediated BR signaling pathway and possibly other unknown pathways through the BZR1 family of transcription factors that directly modulate expression of genes involved in outer integument development (Jia et al., 2020). The embryo sac in null bri1 mutants is abortive, suggesting that either orchestrated development of the outer and inner integuments is required for proper formation of the embryo sac, or development of the embryo sac requires functional BRI1 (Figure 3B; Table 1).

ACR4, a non-LRR-RLK, is required for normal cell organization during ovule integument development. ACR4 is expressed in L1 cells of all apical meristems and young organ primordia. The acr4 mutants generate integuments that are initiated unevenly, and the integuments grow more slowly (Gifford et al., 2003). It is known that the ACR4-CIK receptor complex regulates homeostasis of the columella stem cells in the root by sensing the CLE40 signal to inhibit WUSCHEL RELATED HOMEOBOX 5 (WOX5) expression (Zhu et al., 2021). On the other hand, WUS, a homologous gene of WOX5, can regulate integument formation (Groβ-Hardt et al., 2002). Therefore, whether an unknown CLE peptide might be sensed by ACR4 to suppress WUS expression and then regulate integument development needs to be investigated (Figure 3B; Table 1).

ABNORMAL LEAF SHAPE 2 (ALE2) and SUB/SCM, two other RLKs, regulate ovule development, although the detailed mechanisms still need to be clarified. The ale2 mutants cause defective development of the integument and endothelium, and the embryo sac degenerates. Since ALE2 is involved in cuticle formation in epidermis development, the abnormal ovule development in the ale2 mutant may be due to the defects of the epidermal cells (Tanaka et al., 2007). Loss of function of ACR4 and ALE2 results in similar defective integument development, and the ale2 acr4 double mutants exhibit ovule defects similar to ale2. In addition, the phosphorylation activities of ALE2 and ACR4 kinase domains can be mutually enhanced in vitro. Therefore, ACR4 and ALE2 may regulate integument development in the same pathway (Tanaka et al., 2007). SUB/SCM regulates outer integument development. The sub mutants generate irregular ovules, and the defective outer integument fails to spread around the circumference of the ovule, which results in a scoop-like incomplete outer integument and an abortive embryo sac (Chevalier et al., 2005), further suggesting that orchestrated development of the sporophytic tissue and the female gametophyte is critically required for successful development of the ovule (Figure 3B; Table 1).

RLKs regulate embryo development

Embryogenesis of angiosperms starts immediately after double fertilization. The egg cell fertilized by one sperm cell develops into the zygote that will then generate the embryo, and the other sperm fertilizes the central cell to generate the endosperm. The resulting diploid embryo and triploid endosperm will coordinately develop to form a seed (Dresselhaus and Jürgens, 2021). In Arabidopsis, an asymmetric division of the zygote leads the smaller apical cell to form the embryos and the bigger basal cell to form the extraembryonic suspensor. The apical cell develops to the octant-stage embryo through two successive longitudinal cell divisions and one transverse cell division. The octant-stage embryo cells undergo a round of periclinal cell division to form the radially symmetric dermatogen-stage embryo with eight inner cells and an outer layer of protodermal cells. Then, the four inner basal cells undergo a round of longitudinal division to generate the inner four vascular precursors and the outer four ground tissue stem cells adjacent to the protoderm. The basal cell divides horizontally a couple of times to form a suspensor with six to nine cells. The uppermost cell of the suspensor is incorporated into the embryo proper at the early globular stage and is named the hypophysis, and will generate the upper quiescent center and the lower columella initial after an asymmetric cell division. After successive cell divisions, the globular embryo develops to form a bilaterally symmetric heart-shaped embryo with two protruding cotyledon primordia flanking the medial SAM precursors (Kawashima and Goldberg, 2010; Nodine et al., 2011; Lau et al., 2012; Dresselhaus and Jürgens, 2021) (Figure 4A). During embryo development, RLK-mediated intercellular signaling is important for the specification and spatiotemporal coordination of various cell types in the embryo.

Figure 4.

RLKs regulate embryo development.

(A) Diagrams showing the process of embryo development, including the typical zygote, 1-cell, octant, dermatogen, globular, transition, hart, and torpedo stages.

(B) RLKs regulate embryo development. ESF1, ERf-BSK1/2, SSP, and ZAR1 share the YDA-mediated signaling cascade to regulate zygote development. SERKs play a critical role in maintaining identity of the ground tissue stem cells through the YDA-MKK4/5 signaling pathway. RPK1 and TOAD2 maintain identity of radial pattern formation, and regulate hypophysis differentiation and cotyledon development. ACR4 and ALE2 function in the same process to regulate development of the protoderm and epidermis. The KRS peptide signal regulates formation of the embryo sheath formation. The GSO1/2-SERK receptor-co-receptor complex perceives the TWS1 peptide processed by ALE1 to control integrity of the embryonic cuticle via MPK6. ERf members play a role in cotyledon development. EXS regulates seed size. Colored ovals in the extracellular domains of RLKs represent predicted LRR motifs except the CR4-L-RLK ACR4 and the extensin RLK ALE2. Putative ligands, receptor RLKs, and co-receptor RLKs are shown in gray.

RLKs regulate zygote division and suspensor development

Elongation and asymmetric division of the zygote are critical for the fate of the two resulting daughter cells. SHORT SUSPENSOR (SSP) is the first identified RLCK that plays a key role in regulating zygote elongation and asymmetric division (Bayer et al., 2009). SSP is a membrane-associated protein kinase of the BRASSINOSTEROID SIGNALING KINASE (BSK) family. Intriguingly, the transcripts of SSP are specifically produced in sperm cells, but SSP proteins can only be detected after fertilization in the zygote (Bayer et al., 2009; Neu et al., 2019). The ssp mutants produce zygotes with reduced cell length, and the defective zygote generates a smaller basal cell than the wild type after a defective asymmetric division (Bayer et al., 2009; Neu et al., 2019). Research of SSP functions in embryogenesis revealed a paradigm that some paternally originated gene products may play crucial roles during embryo development. Similar defects in zygote elongation and embryogenesis were observed in mutants losing functions of the MAPK cascade members YODA (YDA), MKK4/5, and MPK3/6 (Lukowitz et al., 2004; Bayer et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2017a). The yda zygote fails to elongate, leading to a nearly equal zygote division, so that the much smaller basal cell eventually cannot produce a recognizable suspensor after irregular divisions (Lukowitz et al., 2004). MPK3/6 can interact with and phosphorylate WRKY2, which leads to upregulated expression of WOX8 in the zygote during the initiation of asymmetric zygote division (Ueda et al., 2017). Although YDA can at least in part be activated by the SSP protein, ssp embryos display less severe defects than the yda mutant (Bayer et al., 2009), suggesting that there are other factors contributing to activation of YDA in the zygote. Loss of function of BSK1/2, two SSP close paralogs, leads to defective zygote elongation and division, similar to ssp. The bsk1/2 ssp mutant exhibits defective zygote development similar to but slightly weaker than yda, which can be rescued by constitutively activated YDA. However, BSK1 cannot rescue the ssp loss of function phenotype in the zygote and early embryo. The current model shows that BSK1/2 activate YDA in parallel to SSP in regulating zygote elongation and division (Neu et al., 2019) (Figure 4B). Besides paternal factor SSP contribution to early embryogenesis, maternal factors play essential roles in regulating early embryogenesis. The central cell-originated small cysteine-rich peptides EMBRYO SURROUNDING FACTOR 1.1 to 1.3 (ESF1.1 to ESF1.3) regulate gene expression programs in the basal cell lineage during early embryogenesis in a non-cell-autonomous manner. The esf1_RNAi lines exhibit abnormal embryogenesis with patterning defects in the embryo proper and reduced suspensor length. However, genetic analyses revealed that ESF1 peptides may regulate early embryo development in a way that is independent of SSP but dependent on YDA (Costa et al., 2014) (Figure 4B; Table 1).

Since expression of SSP can directly activate the YDA signaling cascade, possibly because SSP lacks intramolecular regulatory interaction, it was proposed that a canonical RLK may not be required by SSP to pattern embryogenesis (Neu et al., 2019). However, as typical RLCKs, BSK1/2 may still need an RLK receptor to perceive extracellular signals in regulating zygote elongation and asymmetric division. Very recently, ERf receptor kinases were found to act as maternal factors upstream of BSK1/2 to activate the YDA-dependent signaling during zygotic polarization. Therefore, the paternally initiated SSP and maternal ERf-BSK signal converge at YDA to control zygote elongation and asymmetric division (Wang et al., 2021). It is already known that ERf-mediated ligand signaling of EPFLs regulates inflorescence development and stomata patterning through the YDA-mediated MAPK cascade (Lee et al., 2012; Uchida et al., 2012; Meng et al., 2012, 2015). In addition, similar to EPFL peptides, the ESF1 peptide contains multiple Cys residues that form disulfide bonds to stabilize ESF1 function and regulate zygote development through the YDA-mediated MAPK cascade (Costa et al., 2014). However, the receptor of ESF1 is currently unknown (Figure 4B; Table 1).

RLK-mediated extracellular signals may be integrated with intracellular pathways to regulate early embryo development. For instance, a mutant named zygotic arrest 1 (zar1) shows impaired asymmetric zygote division and defective cell fate of its daughter cells (Yu et al., 2016). ZAR1 encodes a plasma membrane-located LRR VIII-RLK that contains a putative Calmodulin (CaM)-binding domain and a Gβ subunit-binding site in its cytoplasmic kinase domain. The zar1 zygote fails to perform asymmetric division, which results in a shorter basal cell and an apical cell with basal cell identity. CaM and Gβ (AGB1) form a complex with ZAR1 and promote its kinase activity, suggesting that ZAR1 may integrate an as-yet unknown extracellular cue, the intracellular Ca2+ signal, and G protein pathway to regulate zygote development (Yu et al., 2016). In addition, AGB1 interacts with YDA, MKK4/5, and MPK3/6 to function in the same genetic pathway during zygote elongation and division (Yuan et al., 2017). Therefore, ERf-BSK1/2, ESF1, SSP, and ZAR1 possibly share the YDA signaling cascade to coordinately regulate zygote development (Figure 4B; Table 1).

RLKs mediate proper embryo patterning

Once the zygote successfully completes its elongation and asymmetric division, the embryo proper will be created by programmed patterning, a critical biological process that requires RLK’s functions. RPK1 and RPK2/TOAD2 are redundantly required to regulate radial pattern formation and hypophysis differentiation in Arabidopsis embryos (Nodine et al., 2007; Nodine and Tax, 2008). Approximately half of the embryos in the rpk1 toad2/+ mutant fail to set up the normal radial pattern of cell types. Specifically, protodermal cells in the embryo exhibit aberrant cell division patterns at the globular stage. Expression pattern analysis of marker genes in mutant embryos indicated that the fates of embryo outer cells are replaced by inner cell fates. In addition, the hypophyses of the mutant embryos exhibit abnormal division and differentiation, which was indicated by defective expression of marker genes (Nodine et al., 2007). At the heart stage, both the embryo and suspensor of the rpk1 toad2 mutant undergo abnormal morphogenesis, resulting in impaired embryos typically arrested at the late globular stage with a characteristic toadstool shape (Nodine et al., 2007). Moreover, RPK1 and TOAD2 are required to specify cell types of the apical embryonic domain that produces cotyledon primordia (Nodine and Tax, 2008; Fiesselmann et al., 2015). Some rpk1 seedlings miss one cotyledon due to disturbed PIN1 polarity and auxin homeostasis in defective embryos at early developmental stages (Luichtl et al., 2013). It is known that RPK1 and RPK2/TOAD2 are involved in apical meristem maintenance and root development by sensing CLE peptides (Kinoshita et al., 2010; Racolta et al., 2018). In addition, CIKs are required by RPK2 to function as co-receptors in regulating apical meristem and early anther development (Cui et al., 2018). Therefore, unidentified CLE peptides might be recognized by a receptor complex of RPK1/2 and other co-receptor RLKs to regulate embryonic patterning (Figure 4B; Table 1).

Proper specification of embryonic stem cells guarantees continuous production of cells and tissues in the embryo. For example, the ground tissue stem cells generate daughter cells that are specified to form the endodermis and the cortex; the vascular precursors are required for generation of the vascular cells in the embryo. Four Arabidopsis SERKs (SERK1, SERK2, BAK1, and BKK1) have overlapping functions required for programmed transverse division of the vascular precursors and ground tissue stem cells during early embryo development (Li et al., 2019). The vascular precursors in the serk1/2 bak1 embryos at the mid-globular stage divide longitudinally, which is different from the transverse division in the wild-type embryos. On the other hand, the second transverse division of the ground tissue stem cells is altered to a longitudinal division in the serk1/2 bak1 embryos at the early-heart stage. Consistently, expression of WOX5 is expanded into the vascular tissue cells in serk1/2 bak1 embryos, indicating that the stem cell niche in the mutant embryos is impaired. Since the identities of the vascular precursors and the ground tissue stem cells cannot be properly maintained in the serk1/2 bak1 embryos, decreased tiers of vascular cells and fewer cortical and endodermal cells are generated in the serk1/2 bak1 embryos at the torpedo stage. Genetic evidence supports that SERKs act upstream of the YDA-MKK4/5 signaling cascade to maintain the proper division pattern of the ground tissue stem cell. However, no evidence shows that the YDA-MKK4/5 signaling cascade is involved in regulating SERK-mediated vascular precursor division (Li et al., 2019), suggesting that SERKs may recruit a cytoplasmic signaling cascade other than the YDA-mediated one to control vascular precursor identity. It is known that SERKs function as co-receptors of a variety of receptor RLKs to regulate multiple biological processes, such as stomata patterning and floral organ shedding, through MAPK cascades (Meng et al., 2015, 2016), suggesting that SERKs may be recruited by an as-yet unknown RLK receptor to regulate identity of the ground tissue stem cell (Figure 4B; Table 1).

RLKs regulate protodermal development during embryogenesis

Proper differentiation of the epidermis plays a pivotal role for successful embryogenesis. ACR4 and ALE2 play overlapping roles in regulating differentiation of the protoderm during embryogenesis (Tanaka et al., 2002, 2007). ACR4 exhibits relatively high level of expression in the protoderm when compared with the inner cell layers, suggesting that ACR4 plays a role in protoderm development. Consistently, the mutants expressing antisense ACR4 produce abnormal embryos (Tanaka et al., 2002). The ale2 mutation results in deformed embryos with rough surfaces because of swollen protodermal cells. Genetic investigations suggested that ALE2 and ACR4 function in the same process (Tanaka et al., 2007). Loss of function of ALE1, a subtilisin-like serine protease gene expressed in the endosperm surrounding young embryos, results in impaired embryonic cuticle integrity (Tanaka et al., 2001). Both ale1/2 and ale1 acr4 double mutants exhibit very deformed protodermal cells and altered expression patterns of protoderm marker genes in the embryo, which are more severe than each single mutant, supporting that ALE2 and ACR4 may respectively cooperate with ALE1 to regulate embryonic protoderm development (Tanaka et al., 2007) (Figure 4B; Table 1).

Appropriate separation of the embryo from the surrounding endosperm is crucial during embryogenesis, which is at least partially achieved by the cuticle covering the epidermis of the embryo. This compartmentation process is orchestrated by GASSHO1/2 (GSO1/2)-mediated communications between the embryo and the endosperm (Tsuwamoto et al., 2008). TWISTED SEED 1 (TWS1), a small peptide synthesized in the developing embryo at the early globular stage, can spread into the endosperm in the absence of a complete cuticle barrier on the embryo surface and be processed by ALE1 in the surrounding endosperm to produce active mature TWS1. The active TWS1 peptides then bind to GSO1/2 on the plasma membrane of epidermal cells in the embryo through the cuticle gaps to activate the downstream signaling, resulting in successful deposition of continuous cuticle on embryonic epidermis (Doll et al., 2020). As the cuticle of the embryo develops gradually intact, the TWS1 precursors are confined in the embryo and remain inactive (Doll et al., 2020). Consistently, all of the gso1/2, tws1, and ale1 mutants generate similar abnormal embryos with defective cuticle layer and abnormal adherence of the embryo to the inside of the seed (Tanaka et al., 2001; Tsuwamoto et al., 2008; Fiume et al., 2016). Very recently, it was revealed that the serk1/2/3 triple mutants exhibit embryonic cuticle defects similar to gso1/2 and tws1. Exogenously applied TWS1 peptide can enhance the interaction between GSO1/2 and SERKs, and the phosphorylation levels of GSO1/2 and SERKs. Moreover, the phosphorylation enhancement of SERKs in response to TWS1 is dependent on GSO1/2 (Zhang et al., 2022). Therefore, SERKs are recruited by GSO1/2 to form a receptor-co-receptor complex that recognizes TWS1 and regulates embryonic cuticle development. However, the downstream signaling events are largely unknown, although genetic and biochemical results indicated that MPK6 acts in this process (Creff et al., 2019) (Figure 4B). ZHOUPI (ZOU), a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH)-type transcription factor specifically expressed in the endosperm, controls embryonic cuticle integrity by regulating the expression of ALE1 (Yang et al., 2008; Xing et al., 2013). ZOU also promotes the expression of KERBEROS (KRS), a cysteine-rich peptide with a C-terminal proline-rich domain, to regulate the formation of the extracuticular sheath on the surface of the embryo, which separates the embryo from the endosperm (Moussu et al., 2017). The receptor perceiving KRS, however, has not been characterized yet (Figure 4B; Table 1).

Cell size and proliferation are regulated by RLKs during embryogenesis. The exs mutants generate smaller embryonic cells, delayed embryo development, and eventually seeds with strikingly reduced size (Canales et al., 2002) (Figure 4B; Table 1). In addition, ERf members are expressed in the upper half of developing embryos. The er erl1/2 mutants produce defective cotyledons with decreased size during embryogenesis because of decreased cell proliferation (Chen and Shpak, 2014). It is known that EPFLs usually act as ligands of the ERf members to regulate the SAM size and ovule initiation patterns (Kosentka et al., 2019; Kawamoto et al., 2020). A recent study revealed that EPFL2 is expressed in the boundary region between two cotyledons, where EPFL2 functions in a non-cell-autonomous way to promote cotyledon growth during Arabidopsis embryogenesis (Fujihara et al., 2021). It is notable that the serk1/2/3 embryo generates two very short cotyledons (Li et al., 2019), which is similar to the cotyledon defects observed in er erl1 erl3 and epfl2 embryos (Chen and Shpak, 2014). Together with the fact that SERKs function as co-receptors of ERf RLKs to mediate stomatal patterning (Meng et al., 2015), we propose that SERKs may be required as co-receptors in the EPFL2-ERf signaling pathway to control cotyledon elongation and growth during embryogenesis in Arabidopsis (Figure 4B; Table 1).

Concluding remarks and perspectives

When plants develop to the reproductive growth stage, they specialize to form reproductive organs with complex structures. The male and female gametophytes are finally generated and enclosed in the anther and ovule, respectively (Yang et al., 2010). Therefore, coordinated and finely regulated development of various tissues and strict specification of cell fates in reproductive organs are required to ensure successful reproductive development of plants. To achieve this goal, close communications in reproductive organs play particularly important roles. In the past two decades, studies have shown that many RLKs play essential roles to regulate orchestrated development of reproductive organs by mediating a variety of ligand signals, and several important achievements were made. For example, the TPD1-EMS1-SERK1/2 signaling in tapetum specification, TWS1-GSO1/2-SERK signaling in embryonic cuticle formation, and the HAE/HSL2-SERK complex-mediated IDA signaling in the floral organ abscission process have been largely clarified (Li et al., 2017; Jia et al., 2008; Cho et al., 2008; Meng et al., 2016; Santiago et al., 2016; Doll et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022) (Figures 1B, 2B, and 4B; Table 1). Furthermore, CIKs from the same LRR II-RLK family have been recently identified to be novel co-receptors that play crucial roles in meristem maintenance and anther cell specification (Cui et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2018; Gou and Li, 2020) (Figure 2B; Table 1). However, the detailed molecular mechanisms mediated by many other RLKs in reproductive development have not been revealed yet.