Abstract

Background and Aims:

Lynch syndrome (LS) is the most common cause of hereditary colorectal cancer and is associated with an increased lifetime risk of gastric and duodenal cancers of 8–16% and 7% respectively, therefore, we aim to describe an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) surveillance program for upper gastrointestinal (GI) precursor lesions and cancer in LS patients.

Methods:

Patients who either had positive genetic testing or met clinical criteria for LS who had a surveillance EGD at our institution from 1996 to 2017 were identified. Patients were included if they had at least two EGDs or an upper GI cancer detected on the first surveillance EGD. EGD and pathology reports were extracted manually.

Results:

Our cohort included 247 patients with a mean age of 47.1 years (SD 12.6) at first EGD. Patients had a mean of 3.5 EGDs (range 1–16). Mean duration of follow-up was 5.7 years. Average interval between EGDs was 2.3 years. Surveillance EGD detected precursor lesions in 8 (3.2%) patients, two (0.8%) gastric cancers and two (0.8%) duodenal cancers. Two interval cancers were diagnosed: a duodenal adenocarcinoma was detected 2 years, 8 months after prior EGD and a jejunal adenocarcinoma was detected 1 year, 9 months after prior EGD.

Conclusions:

Our data suggest that surveillance EGD is a useful tool to help detect precancerous and cancerous upper GI lesions in LS patients. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine a program of surveillance EGDs in LS patients. More data are needed to determine the appropriate surveillance interval.

Keywords: Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, duodenal cancer

Introduction

Lynch syndrome (LS) is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by inherited germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes that correct spontaneous errors in DNA replication.1 Consequently, LS patients have a substantially increased risk of CRC and other extracolonic malignancies2 for which they are provided surveillance guidelines that are supported by the scientific literature.3–7

LS patients have an increased lifetime risk of gastric and duodenal cancers of 8–16 and 7% respectively.3,8–10 The majority of gastric cancers in LS patients are of the intestinal histologic subtype.11,12 Intestinal-type cancers often originate from chronic gastritis that progresses to intestinal metaplasia then dysplasia and, ultimately, to cancer.13 Therefore, performing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in LS patients may help detect precancerous upper GI lesions that can be treated as well as cancers at early, more curable stages. Currently available data in the literature examining the efficacy of endoscopic surviellance for gastric and duodenal cancers are limited and inconsistent.14–17

In contrast to CRC, guidelines for gastric and duodenal cancer surveillance in LS are conditional, inconsistent across organizations, and based on very low quality evidence. For example, suveillance guidelines by the American College of Gastroenterology recommend baseline EGD at age 30–35 and then consideration of ongoing surveillance every 2–3 years in patients with a positve family history of gastric or duodenal cancer, whereas the European Hereditary Tumor Group does not recommend surveillance EGD, and the American Socety of Clinical Oncology recommends EGD on an individuliazed basis.16–18 At Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), we now perform surveillance EGDs in LS patients beginning at age 30–35 and then every 2–5 years on and individualized basis.

Prior studies of surveillance EGD in LS patients showed mixed evidence for surveillance EGD.14–17 The aim of this study was to describe a program of surveillance EGD for precursor lesions and upper gastrointestinal (GI) cancers in LS patients.

Methods

Design

We performed a retrospective chart review of LS patients by identifying suspected LS patients using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes who had at least two EGDs between January 1996 and June 2017 and a pathology report or initial consult note that contains at least one of the following terms, “Lynch,” “HNPCC”, “hereditary nonpolyposis” or “hereditary non-polyposis.” We confirmed that all patients in our MSKCC Lynch database with at least 2 EGDs were included. Charts were reviewed for patient characteristics, cancer history, genetic testing, family history, endoscopy and pathology reports. MSKCC’s Institutional Review Board approved this study. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Patient Population

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of LS and had at least two EGDs or cancer detected on the initial baseline surveillance EGD. LS patients were defined as fulfilling at least one of the following criteria: 1) confirmed likely pathogenic or pathogenic germline mutation in one of the DNA MMR genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 or EPCAM) (68.0%); 2) met Amsterdam II or revised Bethesda criteria and had a diagnosis of a LS-related cancer (CRC, endometrial, ovarian, urothelial, pancreas, hepatobiliary, small bowel, transitional cell cancer of the renal pelvis and ureter, glioma, sebaceous neoplasm and medulloblastoma) with a loss of expression of one of the DNA MMR proteins on immunohistochemistry (IHC) or detection of microsatellite instability in the LS-related tumor (20.2%); 3) met Amsterdam II or revised Bethesda criteria alone (11.3%) or 4) presumed occult mutation as determined by an expert from the Clinical Genetics Service (0.4%).19,20 Among those in the Amsterdam II or revised Bethesda group alone, we included data prior to widespread germline testing so not all of our patients have an identified germline mutation or declined genetic testing. Patients who did not have LS, had a prior upper GI cancer, had fewer than two surveillance EGDs or did not have cancer diagnosed on the first surveillance EGD were excluded. EGDs performed exclusively for symptoms were excluded.

Germline Mutation Analysis

Genetic testing reports and consultation notes from the MSKCC Clinical Genetic Service were reviewed. Patients were determined to have a LS germline mutation if either their genetic report was positive for a likely pathogenic or pathogenic mutation or if the Clinical Genetic service made a clinical diagnosis of LS based upon family and/or personal history of malignancy. If there were any questions about the genetic test result data, the chart was reviewed by an expert from the Clinical Genetics Service.

Endoscopy and Pathology

The majority of surveillance EGDs were performed by MSKCC GI physicians and pathology was examined by MSKCC pathologists. We included a small number of surveillance EGD data from outside institutions when we had both the EGD and pathology reports, if biopsies were taken. If there were any questions about pathology results, the chart was reviewed by an expert GI pathologist.

Results

We identified 517 LS patients using CPT codes and the above described methods (Figure 1.) Twenty-five patients were excluded for having an upper GI cancer diagnosed prior to undergoing surveillance EGD. Two hundred and forty-five patients were excluded for not having had at least two surveillance EGDs or cancer detected on the initial baseline surveillance EGD.

Figure 1. Flow of Patients.

EGD – esophagogastroduodenoscopy

LS – lynch syndrome

GI - gastrointestinal

MMR – mismatch repair

MSI – microsatellite instability

Our final study cohort of two hundred and forty-seven LS patients had at least two surveillance EGDs or cancer detected on the initial baseline surveillance EGD. Of the 247 LS patients, 168 (68.0%) had confirmed germline mutations in DNA MMR genes (34% MLH1, 40% MSH2, 15% MSH6, 11% PMS2 and 0% EPCAM.) The remaining 79 patients had unknown germline mutation status but were classified as LS by clinical criteria based on either meeting Amsterdam II or revised Bethesda criteria and having a LS-related cancer with a deficiency in one of the DNA MMR proteins or MSI (63.3%), meeting Amsterdam II or revised Bethesda criteria alone (35.4%) or determined to likely have an occult mutation (1.3%). If there were any questions about genetic test result data, the chart was reviewed by an expert from the Clinical Genetics Service.

The study cohort of 247 LS patients was 66% female with mean age at initial baseline surveillance EGD of 47.1 years ± 12.6 (mean ± SD), ranging from 15 – 88 years (Table 1.) LS patients were followed for a mean of 5.7 years, (range 0.0 – 19.9), over which time patients had a mean of 3.5 EGDs (range: (1–16). Average interval between surveillance EGDs was 2.3 years.

Table 1.

Patient Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristic | All patients (n=247) |

Known germline mutation (n=168) |

LS by clinical criteria (n=79) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, female | 163 (66) | 109 (65) | 54 (68) |

| Age at first EGD | |||

| 15–24 | 8 (3) | 7 (4) | 1 (1) |

| 25–34 | 33 (13) | 31 (18) | 2 (3) |

| 35–44 | 64 (26) | 50 (30) | 14 (18) |

| 45–54 | 77 (31) | 49 (29) | 28 (35) |

| 55–64 | 46 (19) | 22 (13) | 24 (30) |

| 65–74 | 12 (5) | 7 (4) | 5 (6) |

| 75+ | 7 (3) | 2 (1) | 5 (6) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 14 (6) | 9 (5) | 5 (6) |

| Black | 6 (2) | 5 (3) | 1 (1) |

| White | 218 (88) | 147 (88) | 71 (90) |

| Other | 9 (4) | 7 (4) | 2 (3) |

| Mutation | |||

| MLH1 | 57 (23) | 57 (34) | N/A |

| MSH2 | 67 (27) | 67 (40) | N/A |

| MSH6 | 25 (10) | 25 (15) | N/A |

| PMS2 | 18 (7) | 18 (11) | N/A |

| EPCAM | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Cancer | |||

| Colorectal | 143 | 87 | 56 |

| Endometrial | 56 | 39 | 17 |

| Ovarian | 12 | 7 | 5 |

| Urothelial | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| Pancreas | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Hepatobiliary | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Small bowel (non-duodenum) | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Transitional cell of the renal pelvis and ureter | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Glioma | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Sebaceous neoplasms | 54 | 23 | 31 |

| Medulloblastoma | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Family History of Gastric Cancer | 74 (30) | 46 (27) | 28 (35) |

| Family History of Small Bowel Cancer | 11 (4) | 4 (2) | 7 (9) |

All values are n (%) unless otherwise specified

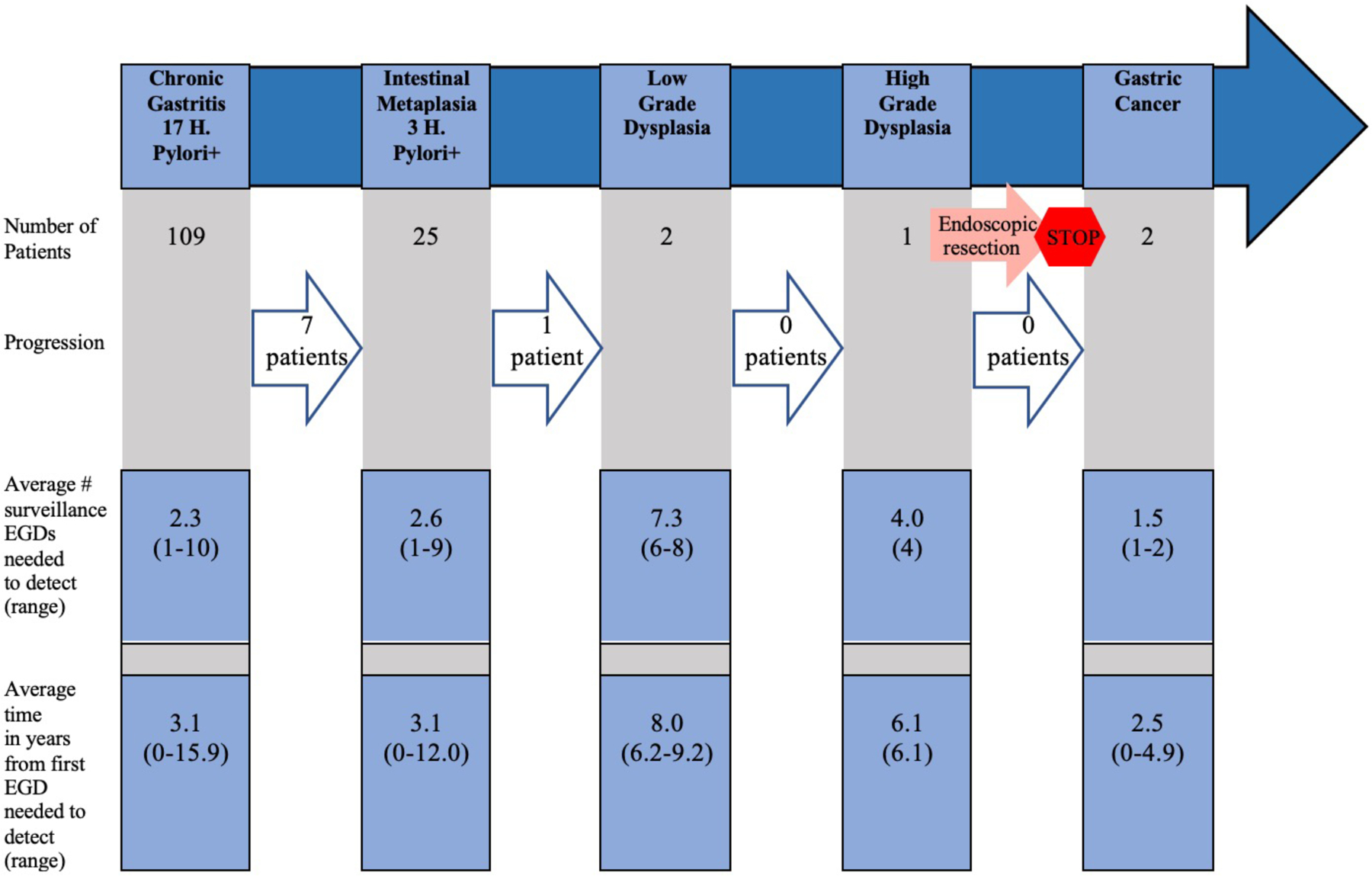

Chronic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia of the stomach were detected in 109 (44.1%) and 25 (10.1%) patients respectively (see Table 2.) Of those with chronic gastritis 17 (15.6%) were H. pylori positive and for the intestinal metaplasia group three (12.0%) were HP positive. Of those with chronic gastritis, seven (6.4%) showed progression to gastric intestinal metaplasia on subsequent EGDs. Chronic gastritis (n =109 patients), intestinal metaplasia (n = 25 patients) and gastric cancer (n = 2 patients) were detected after an average of 2.3, 2.6 and 1.5 EGDs respectively. Duodenal or ampullary adenomas (n = 6 patients) and duodenal cancer (n = 2 patients) were detected after an average of 3.8 and 1.5 EGDs respectively (Figure 2 and Figure 3.)

Table 2.

Surveillance EGD and pathology results

| Number of Patients | Number of EGDs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total LS Patients n = 247 |

Germline Mutation n = 168 |

Total LS Patients n = 873 |

Germline Mutation n = 559 |

||

| Stomach biopsies performed | 168 (68.0) | 112 (66.7) | 334 (38.3) | 214 (38.3) | |

| Chronic gastritis | 109 (44.1) | 72 (42.9) | 161 (18.4) | 100 (17.9) | |

| Chronic gastritis with H. pylori infection | 17 (6.9) | 10 (6.0) | 21 (2.4) | 11 (2.0) | |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 25 (10.1) | 16 (9.5) | 35 (4.0) | 20 (3.6) | |

| Intestinal metaplasia with H. pylori infection | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 6 (0.69) | 0 (0) | |

| Chronic gastritis with progression to intestinal metaplasia | 7 (2.8) | 2 (1.2) | 21 (2.4) | 6 (1.1) | |

| Precancerous lesions | 8 (3.2) | 2 (1.2) | 15 (1.7) | 7 (1.3) | |

| Gastric cancer | 2 (.81) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (0.23) | 2 (0.36) | |

| Duodenal cancer | 2 (.81) | 1 (0.60) | 2 (0.23) | 1 (0.18) | |

All values are n (%) unless otherwise specified

Figure 2.

Gastric Pathology Progression

EGD – esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Figure 3.

Duodenal Pathology Progression

EGD – esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Precancerous lesions were found in eight (3.2%) patients and were detected after an average of 5.1 EGDs. These included three total foci of polypoid low-grade foveolar dysplasia, one foveolar dysplasia, two gastric adenomas including one with high-grade dysplasia, seven duodenal adenomas and two ampullary adenomas. The patient with the polypoid low-grade foveolar dysplasia and foveolar dysplasia was a 63-year-old Caucasian woman, with Muir-Torre variant subtype of Lynch syndrome, who harbored an MSH2 germline mutation, and had a personal history of endometrial cancer, sebaceous neoplasm and vulvar cancer. Persistent low-grade dysplasia was detected on annual surveillance follow-up EGDs for the next two years, following which there was no further evidence of ongoing dysplasia on five subsequent follow-up EGDs. The patient with the gastric adenoma with high-grade dysplasia was a 42-year-old Caucasian woman who met Amsterdam II criteria and revised Bethesda criteria with a personal history of colon cancer and Hodgkin’s lymphoma (diagnosed at age nine, treated with chemotherapy and radiation therapy.) The adenoma was detected on her fourth surveillance EGD and noted as a polyp in the cardia of the stomach. The gastric polyp lesion was endoscopically resected following which four subsequent EGDs demonstrated no further evidence of dysplasia. Three of the eight patients with precancerous lesions had a family history of upper GI cancers. Of these three patients, one was MSH2 mutation positive, one met Amsterdam II criteria and had history of colon cancer with a deficiency in one of the MMR proteins and one met Amsterdam II criteria, revised Bethesda and had an LS-related cancer with a deficiency in one of the MMR proteins or MSI.

Two gastric cancers were found on surveillance EGD. One gastric cancer was detected on the first surveillance EGD of a 69-year-old Caucasian man with a MSH6 mutation and a personal history of two colorectal cancers and prostate cancer. His gastric cancer was an invasive moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma of intestinal type located in the antrum. He was also H. pylori positive at the time of diagnosis. This gastric cancer was early stage (pT1a) and was removed by endoscopic mucosal resection. The H. pylori infection was also successfully treated. The patient was alive after 5.5 years of follow-up. The other gastric cancer was detected on the second surveillance EGD of an 83-year-old Caucasian man with an MSH2 mutation and a personal history of pancreatic, urothelial, sebaceous neoplasm, and prostate cancer. His first surveillance EGD was 4 years and 10 months prior to his second surveillance EGD. The cancer was an invasive poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of mixed type at the gastric cardia, with a loss of MSH2 and MSH6 protein on IHC. The patient was H. pylori negative. This gastric cancer was late stage (pT3) at the time of diagnosis, and the patient was treated with chemotherapy and surgery. The patient died 3.5 years later due to metastatic urothelial cancer. Neither gastric cancer patients had a family history of upper GI cancers.

Two duodenal cancers were found on surveillance EGD. One duodenal cancer was detected on the first EGD at an outside institution of a 76-year-old Caucasian woman with an MLH1 mutation and a personal history of four prior colorectal cancers. The cancer was an invasive moderately to poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the intestinal type with loss of MLH1 and PMS2 protein on IHC, arising in a background of tubular adenoma, located at the second portion of the duodenum. The cancer was stage pT2 and the patient was treated with surgery and chemotherapy. The patient was alive at five year follow-up. The other duodenal cancer was detected on the second surveillance EGD of a 59-year-old Caucasian man with a personal history of colorectal cancer who met revised Bethesda criteria. His first surveillance EGD was 1 year and 2 months prior to his second surveillance EGD. The second EGD was performed for mild epigastric pain, for confirmation of H. pylori eradication detected on his first EGD and surveillance. The cancer was a low-grade endocrine neoplasm/carcinoid tumor in the duodenal bulb. Notably, duodenal carcinoid tumors are not associated with LS. The tumor was staged T1 by endoscopic ultrasound and removed by endoscopic mucosal resection. The patient was alive at two year follow-up, and then subsequently lost to further follow-up. Neither patient had a family history of stomach or duodenal cancer.

Two interval cancers were diagnosed during EGD surveillance in our LS cohort, including a duodenal adenocarcinoma at the third portion of duodenum, which may not have been seen on routine EGD, and a jejunal adenocarcinoma. The duodenal adenocarcinoma was detected in a 46-year-old Caucasian woman who met Amsterdam II criteria and had no germline genetic testing. Her duodenal cancer demonstrated deficiency in MLH1 and PMS2 protein expression by IHC, was stage pT3 and was detected at MSKCC 2 years and 8 months after a prior negative surveillance EGD at an outside institution. The patient was alive at 3.5 year follow-up. The jejunal adenocarcinoma was detected in a 60-year-old Caucasian man who met Amsterdam II criteria, but did not have genetic testing, and a personal history of two colorectal cancers. The jejunal cancer was located at the ligament of Treitz and was pT4 pN2. The cancer was detected 1 year and 9 months after a prior surveillance EGD. However, given the location of the tumor, this would likely not have been visualized on routine EGD. The patient died 4.5 years later due to his jejunal cancer. Neither of these small bowel cancer patients had a family history of upper GI cancers.

Discussion

In our cohort of 247 LS patients undergoing surveillance EGD we found 15 precancerous lesions in eight patients, two gastric cancers and two duodenal cancers. An average of more than one EGD was required to detect any gastric or duodenal pathology.

The hypothesized pathogenic mechanism of gastric cancer in LS patients is thought to follow the intestinal metaplasia – dysplasia – carcinoma pathway, while the influence of H.pylori is still under investigation. Intestinal-type adenocarcinoma is the predominant type of gastric cancer in LS patients and consists of glandular or tubular components with various degrees of differentiation12,14 Intestinal-type adenocarcinoma has been strongly linked to H.pylori infection.21,22 In 1994, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified H.pylori as a class I carcinogen.23

There are few prior studies that have looked at the utility of surveillance EGD in LS patients. Renkonen-Sinisalo et al reported a single EGD in 73 LS patients and found no gastric cancers and one duodenal cancer.14 Precursor lesions (gastric polyps, H.pylori, inflammation, atrophy and intestinal metaplasia of the stomach) were not significantly different in 73 mutation-positive vs. 32 mutation-negative patients. Galiatsatos et al reported surveillance EGDs in 21 patients (average 1.5 EGDs per patient) and found four out of 21 patients had precursor lesions (H.pylori gastritis, atrophic gastritis and gastric intestinal metaplasia of the stomach) and found no gastric cancers.15

To our knowledge, no prior study has evaluated a surveillance program of EGDs in LS. Strengths of our study include our large sample size of LS patients and long follow up time.

Some suggest identifying and performing surveillance in a subset of LS patients (MLH1 or MSH2 mutation carriers, male sex, older age, number of first degree relatives with gastric cancer or in countries with a high incidence of gastric cancer) who maybe at increased risk for gastric cancer.3,4,6,24,25 The gastric cancers in our cohort were diagnosed in MSH6 and MSH2 Caucasian men, both of whom had no family history of upper GI cancers. If more restrictive guidelines were followed, these cancers may perhaps have been detected at a more advanced stage.

Our study has several limitations. Our study is a retrospective study performed at a single center with multiple physicians with different practices. A small number of EGDs were performed outside of MSKCC. Our results may not generalize to other populations with LS. Next, half of the cancers identified in our study were detected upon first EGD, therefore it is challenging to determine an appropriate time interval for screening. Next, we did not have a control group of LS patients who did not undergo surveillance EGD for comparison. At first, we attempted to identify a control group from the literature as the Dutch have published on the prevalence and epidemiology of upper GI cancer in LS patients who have not undergone surveillance.12 However, it would have been challenging to match our cohort to the reported Dutch cohort by age and mutation status and our study only captures at minimum one EGD which is too small for an analysis. Next, patients did not routinely undergo gastric biopsy at time of all surveillance EGDs at MSKCC. Next, we included data prior to widespread germline testing so not all of our patients have an identified germline mutation. We felt that in order to examine a surveillance program of EGDs we needed long-term data and thus included a more heterogenous group.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine a program of surveillance EGDs in LS patients. Our data suggest that surveillance EGD is a useful tool to help detect precancerous and cancerous upper GI lesions in LS patients. More data are needed to determine the appropriate surveillance interval, its cost-effectiveness and whether there are subgroups who may perhaps benefit from surveillance more than others.

Funding:

This work was supported by grant P30 CA008748/CA/NCI NIH HHS/United States.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/competing interests: A.H.C., J.J.Y., A.L., A.J.M., J.S., J.M., D.C., H.G., E.L., M.A.S., E.K., M.D., and R.B.M. declare no conflicts of interest. Z.K.S. reports that an immediate family member holds consulting/advisory roles with Allergan, Adverum, Genentech/Roche, Gyroscope Tx, Novartis, Neurogene, Optos Plc, Regeneron, Regenxbio.

Ethics approval: MSKCC’s Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Availability of data and material:

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request (de-identified.)

References

- 1.Rustgi AK. The genetics of hereditary colon cancer. Genes Dev. 2007;21(20):2525–2538. doi: 10.1101/gad.1593107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynch HT, de la Chapelle A. Genetic susceptibility to non-polyposis colorectal cancer. J Med Genet. 1999;36(11):801–818. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Provenzale D, Gupta S, Ahnen DJ, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal. Version 3.2019. Accessed April 22, 2020. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_colon.pdf

- 4.Stoffel EM, Mangu PB, Gruber SB, et al. Hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline endorsement of the familial risk-colorectal cancer: European Society for Medical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2015;33(2):209–217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giardiello FM, Allen JI, Axilbund JE, et al. Guidelines on genetic evaluation and management of Lynch syndrome: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(2):502–526. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Syngal S, Brand RE, Church JM, et al. ACG clinical guideline: Genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(2):223–262; quiz 263. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubenstein JH, Enns R, Heidelbaugh J, Barkun A, Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Diagnosis and Management of Lynch Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(3):777–782; quiz e16–17. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aarnio M, Sankila R, Pukkala E, et al. Cancer risk in mutation carriers of DNA-mismatch-repair genes. Int J Cancer. 1999;81(2):214–218. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Møller P, Seppälä TT, Bernstein I, et al. Cancer risk and survival in path_MMR carriers by gene and gender up to 75 years of age: a report from the Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database. Gut. 2018;67(7):1306–1316. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park YJ, Shin K-H, Park J-G. Risk of Gastric Cancer in Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer in Korea. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(8):2994–2998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aarnio M, Salovaara R, Aaltonen LA, Mecklin JP, Järvinen HJ. Features of gastric cancer in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer syndrome. Int J Cancer. 1997;74(5):551–555. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capelle LG, Van Grieken NCT, Lingsma HF, et al. Risk and epidemiological time trends of gastric cancer in Lynch syndrome carriers in the Netherlands. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(2):487–492. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.10.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wroblewski LE, Peek RM, Wilson KT. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: factors that modulate disease risk. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(4):713–739. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00011-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Sipponen P, Aarnio M, et al. No support for endoscopic surveillance for gastric cancer in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37(5):574–577. doi: 10.1080/00365520252903134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galiatsatos P, Labos C, Jeanjean M, Miller K, Foulkes WD. Low yield of gastroscopy in patients with Lynch syndrome. Turk J Gastroenterol Off J Turk Soc Gastroenterol. 2017;28(6):434–438. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2017.17176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leach BH. Lynch Syndrome. American College of Gastroenterology. Accessed April 21, 2020. https://gi.org/topics/lynch-syndrome/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vasen HFA, Blanco I, Aktan-Collan K, et al. Revised guidelines for the clinical management of Lynch syndrome (HNPCC): recommendations by a group of European experts. Gut. 2013;62(6):812–823. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yurgelun MB, Hampel H. Recent Advances in Lynch Syndrome: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Cancer Prevention | American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. Accessed April 21, 2020. https://ascopubs.org/doi/full/10.1200/EDBK_208341 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Vasen HF, Watson P, Mecklin JP, Lynch HT. New clinical criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, Lynch syndrome) proposed by the International Collaborative group on HNPCC. Gastroenterology. 1999;116(6):1453–1456. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70510-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Umar A, Boland CR, Terdiman JP, et al. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(4):261–268. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danesh. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer: systematic review of the epidemiological studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13(7):851–856. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00546.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Helicobacter pylori Infection and the Development of Gastric Cancer. 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humans IWG on the E of CR to. Schistosomes, Liver Flukes and Helicobacter Pylori. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim J, Braun D, Ukaegbu C, et al. Clinical Factors Associated With Gastric Cancer in Individuals With Lynch Syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2020;18(4):830–837.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasen HFA, Möslein G, Alonso A, et al. Guidelines for the clinical management of Lynch syndrome (hereditary non‐polyposis cancer). J Med Genet. 2007;44(6):353–362. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.048991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request (de-identified.)