Abstract

The reported frequency and types of adverse events following initial vaccination and revaccination with Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) varies worldwide. Using active surveillance in a randomised controlled trial of BCG vaccination (the BRACE trial), we determined the incidence and risk factors for the development of BCG injection site abscess and regional lymphadenopathy. Injection site abscess occurred in 3% of 1387 BCG-vaccinated participants; the majority (34/41, 83%) resolved without treatment. The rate was higher in BCG-revaccinated participants (OR 3.6, 95% CI 1.7–7.5), in whom abscess onset was also earlier (median 16 vs. 27 days, p = 0.008). No participant with an abscess had a positive interferon-gamma release assay. Regional lymphadenopathy occurred in 48/1387 (3%) of BCG-vaccinated participants, with a higher rate in revaccinated participants (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.1–3.9). BCG-associated lymphadenopathy, but not injection site abscess, was influenced by age and sex. A previous positive tuberculin skin test was not associated with local reactions. The increased risk of injection site abscess or lymphadenopathy following BCG revaccination is relevant to BCG vaccination policy in an era when BCG is increasingly being considered for novel applications.

Subject terms: Outcomes research, Live attenuated vaccines

Introduction

The most common adverse reactions to Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination are injection site abscess and regional lymphadenitis1,2. The reported frequency of these local adverse events following immunisation (AEFI) varies worldwide, likely attributable to different surveillance methods, case definitions, vaccine dose and strain, vaccine administration route, as well as host immune status3–5.

Using standard case definitions and active surveillance data from a multicentre randomised controlled trial of BCG vaccination to reduce the impact of COVID-19 in healthcare workers (the BRACE trial; ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04327206; date of registration 31 March 2020), we aimed to determine the incidence, and the risk factors for the development, of BCG injection site abscess and regional lymphadenopathy.

Results

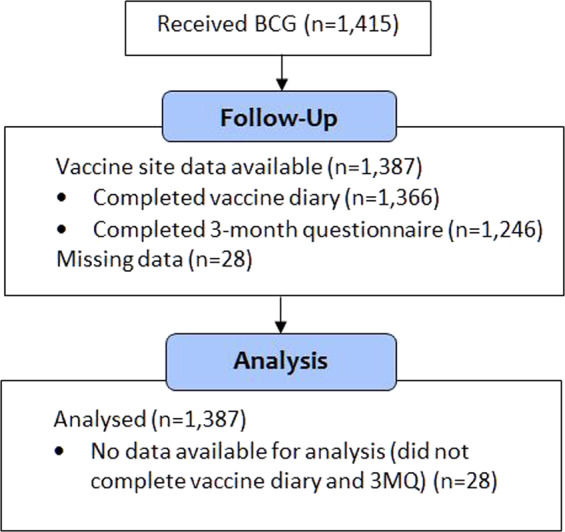

Among the 1415 participants who received BCG, 1387 (98%) provided vaccine safety data (Fig. 1). Vaccinees ranged in age from 19 to 74 years old (median 41) and comprised predominantly healthcare workers (HCW) in clinical roles (77% nurses, doctors or allied health clinicians) (Table 1). The majority were female (76%) and a half (51%) had a prior history of BCG vaccination.

Fig. 1. BRACE stage 1 participants who received BCG.

BCG Bacille Calmette-Guérin, 3MQ 3-month questionnaire.

Table 1.

Factors investigated for association with the development of BCG adverse reaction.

| Factor | Total | BCG injection site abscess | BCG-associated lymphadenopathy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCG | Univariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| n = 1387 | n = 41 (%) | OR (95% CI) | Adjusteda OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | n = 48 (%) | OR (95% CI) | Adjusteda OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 1048 | 32 (3.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | — | 43 (4.1) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Male | 339 | 9 (2.7) | 0.87 (0.41–1.83), p = 0.71 | 0.83 (0.39–1.76), p = 0.62 | 5 (1.5) | 0.35 (0.14–0.89), p = 0.03 | 0.34 (0.13–0.87), p = 0.02 | 0.33 (0.13–0.86), p = 0.02 | |

| Age | |||||||||

| 18–49 | 932 | 29 (3.1) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | — | 39 (4.2) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 50+ | 455 | 12 (2.6) | 0.84 (0.43–1.67), p = 0.63 | 0.57 (0.28–1.16), p = 0.12 | 9 (2.0) | 0.46 (0.22–0.95), p = 0.04 | 0.35 (0.17–0.78), p = 0.007 | 0.35 (0.16–0.75), p = 0.007 | |

| State | |||||||||

| Western Australia | 891 | 16 (1.8) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | — | 36 (4) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | — |

| Victoria | 496 | 25 (5.0) | 2.91 (1.54–5.51), p = 0.001 | 3.20 (1.68–6.09), p < 0.001 | 12 (2.4) | 0.59 (0.30–1.14), p = 0.12 | 0.61 (0.31–1.19), p = 0.15 | ||

| Study site | |||||||||

| A | 268 | 9 (3.4) | 1.18 (0.56–2.50), p = 0.67 | 1.15 (0.54–2.45), p = 0.72 | 1.15 (0.54–2.45), p = 0.72 | 13 (4.9) | 1.58 (0.82–3.03), p = 0.17 | 1.56 (0.81–2.99), p = 0.18 | — |

| B | 362 | 2 (0.6) | 0.14 (0.03–0.58), p = 0.007 | 0.13 (0.03–0.55), p = 0.006 | 0.13 (0.03–0.55), p = 0.006 | 16 (4.4) | 1.43 (0.78–2.65), p = 0.25 | 1.41 (0.76–2.60), p = 0.28 | |

| C | 261 | 5 (1.9) | 0.59 (0.23–1.52), p = 0.28 | 0.57 (0.22–1.48), p = 0.25 | 0.57 (0.22–1.48), p = 0.25 | 7 (2.7) | 0.73 (0.32–1.64), p = 0.45 | 0.72 (0.32–1.62), p = 0.43 | |

| D | 368 | 22 (6.0) | 3.35 (1.79–6.26), p < 0.001 | 3.94 (2.09–7.44), p < 0.001 | 3.94 (2.09–7.44), p < 0.001 | 10 (2.7) | 0.72 (0.36–1.46), p = 0.37 | 0.76 (0.37–1.55), p = 0.45 | |

| E | 113 | 3 (2.7) | 0.89 (0.27–2.92), p = 0.84 | 0.80 (0.24–2.65), p = 0.72 | 0.80 (0.24–2.65), p = 0.72 | 1 (0.9) | 0.23 (0.03–1.71), p = 0.15 | 0.22 (0.03–1.62), p = 0.14 | |

| F | 15 | 0 (0.0) | — | — | — | 1 (6.7) | 2.01 (0.26–15.63), p = 0.50 | 2.06 (0.26–16.08), p = 0.49 | |

| Role | |||||||||

| Nurse/midwife | 569 | 17 (3.0) | 1.02 (0.54–1.91), p = 0.95 | 1.08 (0.57–2.03), p = 0.82 | — | 22 (3.9) | 1.23 (0.69–2.18), p = 0.49 | 1.26 (0.70–2.24), p = 0.44 | 1.01 (0.56–1.83), p = 0.98 |

| Medical practitioner | 261 | 13 (5.0) | 2.06 (1.05–4.03), p = 0.04 | 1.81 (0.92–3.56), p = 0.09 | 11 (4.2) | 1.30 (0.65–2.57), p = 0.46 | 1.22 (0.61–2.43), p = 0.58 | 1.48 (0.72–3.05), p = 0.28 | |

| Allied health | 230 | 4 (1.7) | 0.54 (0.19–1.51), p = 0.24 | 0.55 (0.19–1.56), p = 0.26 | 4 (1.7) | 0.45 (0.16–1.26), p = 0.13 | 0.45 (0.16–1.27), p = 0.13 | 0.42 (0.15–1.20), p = 0.11 | |

| Administrative/clerical | 190 | 4 (2.1) | 0.67 (0.24–1.91), p = 0.46 | 0.69 (0.24–1.97), p = 0.49 | 5 (2.6) | 0.73 (0.28–1.85), p = 0.50 | 0.73 (0.29–1.88), p = 0.52 | 0.87 (0.34–2.26), p = 0.78 | |

| Scientist (medical/research) | 45 | 1 (2.2) | 0.74 (0.10–5.50), p = 0.77 | 0.65 (0.09–4.86), p = 0.68 | 6 (13.3) | 4.76 (1.91–11.86), p = 0.001 | 4.53 (1.81–11.32), p = 0.001 | 4.30 (1.70–10.88), p = 0.002 | |

| PSA/hospital maintenance | 78 | 1 (1.3) | 0.41 (0.06–3.04), p = 0.38 | 0.45 (0.06–3.36), p = 0.44 | 0 (0.0) | — | — | — | |

| Dentist/dental therapy | 6 | 1 (16.7) | 6.71 (0.77–58.72), p = 0.09 | 5.96 (0.66–53.77), p = 0.11 | 0 (0.0) | — | — | — | |

| Other | 8 | 0 (0.0) | — | — | 0 (0.0) | — | — | — | |

| BCG history | |||||||||

| 1st BCG | 673 | 10 (1.5) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 18 (2.7) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| BCG revaccination | 714 | 31 (4.3) | 3.01 (1.46–6.19), p = 0.003 | 3.01 (1.46–6.19), p = 0.003 | 3.61 (1.74–7.51), p = 0.001 | 30 (4.2) | 1.60 (0.88–2.89), p = 0.12 | 1.60 (0.88–2.89), p = 0.12 | 2.11 (1.14–3.95), p = 0.02 |

| Vaccinator experience | |||||||||

| Experienced | 563 | 25 (4.4) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | — | 14 (2.5) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | — |

| Trained | 743 | 14 (1.9) | 0.41 (0.21–0.80), p = 0.009 | 0.39 (0.13–2.37), p = 0.006 | 31 (4.2) | 1.71 (0.90–3.24), p = 0.10 | 1.68 (0.88–3.18), p = 0.12 | ||

| Learner | 81 | 2 (2.5) | 0.54 (0.13–2.34), p = 0.42 | 0.55 (0.13–2.37), p = 0.42 | 3 (3.7) | 1.51 (0.42–5.37), p = 0.53 | 1.52 (0.43–5.40), p = 0.52 | ||

| BCG batch | |||||||||

| 118006D Exp 08/2020 | 675 | 27 (4.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | — | 22 (3.3) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | — |

| 118017 F Exp 11/2020 | 683 | 14 (2.0) | 0.50 (0.26–0.97), p = 0.04 | 0.46 (0.24–0.89), p = 0.02 | 24 (3.5) | 1.08 (0.60–1.95), p = 0.80 | 1.04 (0.58–1.88), p = 0.89 | ||

| 118017H Exp 11/2020 | 29 | 0 (0.0) | — | — | 2 (6.9) | 2.20–0.49–9.83), p = 0.30 | 2.06 (0.46–9.26), p = 0.35 | ||

| Satisfactory vaccination | |||||||||

| Yes | 1205 | 32 (2.7) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | — | 44 (3.7) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | — |

| No | 22 | 1 (4.5) | 1.75 (0.23–13.38), p = 0.59 | 1.81 (0.23–14.09), p = 0.57 | 1 (4.5) | 1.26 (0.17–9.55), p = 0.83 | 1.27 (0.17–9.71), p = 0.82 | ||

| Unknown | 160 | 8 (5.0) | 1.93 (0.87–4.27), p = 0.10 | 2.29 (1.02–5.11), p = 0.04 | 3 (1.9) | 0.50 (0.15–1.64), p = 0.26 | 0.54 (0.16–1.76), p = 0.3 | ||

| Lived in TB endemic country | |||||||||

| No | 1189 | 34 (2.8) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | — | 43 (3.6) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | — |

| Yes | 171 | 7 (4.0) | 1.45 (0.63–3.32), p = 0.38 | 1.12 (0.48–2.60) p = 0.80 | 5 (2.9) | 0.80 (0.31–2.04), p = 0.64 | 0.69 (0.27–1.80), p = 0.45 | ||

| Unknown | 27 | 0 (0.0) | — | — | 0 (0.0) | — | — | ||

| Previous known LTBI | |||||||||

| No | 1357 | 41 (3.0) | — | — | — | 46 (3.4) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | — |

| Yes | 18 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.1) | 3.56 (0.80–15.95), p = 0.10 | 3.26 (0.72–14.71), p = 0.12 | ||||

| Unknown | 12 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | — | — | ||||

| Previous TST | |||||||||

| Negative/None | 1032 | 38 (3.7) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | — | 34 (3.3) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | — |

| Positive (>5mm) | 103 | 3 (2.9) | 0.78 (0.24–2.59), p = 0.69 | 0.52 (0.16–1.75), p = 0.29 | 4 (3.9) | 1.19 (0.41–3.41), p = 0.75 | 1.04 (0.49–2.19), p = 0.93 | ||

| Unknown | 252 | 0 (0.0) | — | — | 10 (4.0) | 1.21 (0.59–2.49), p = 0.60 | — | ||

BCG Bacille Calmette-Guérin, LTBI latent tuberculosis infection, OR odds ratio, PSA patient services assistant, TB tuberculosis, TST tuberculin skin test.

aAdjusted for revaccination.

BCG injection site abscess

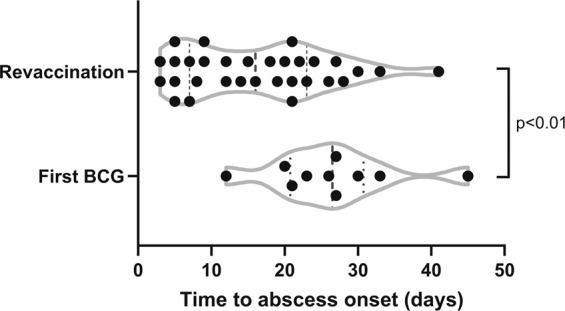

BCG injection site abscess occurred in 41/1387 (3.0%) participants: 10 of 673 (1.5%) BCG-naïve participants; 31 of 714 (4.3%) with a prior history of BCG vaccination (Table 1). Of the 1387 participants, 1200 (87%) reported erythema and/or swelling at the injection site, but did not meet the criteria for BCG injection site abscess. The median time to abscess onset was 20 days (interquartile range [IQR] 9–26) (Table 2), occurring earlier in revaccinated participants (median 16 days (IQR 8–23) vs. 27 days (IQR 22–30), p = 0.008) (Fig. 2). In BCG-revaccinated participants, the previous dose had been administered 9 to 55 years (median 34) prior. Five participants had two prior BCG vaccinations.

Table 2.

Clinical features of BCG local adverse reactions.

| Injection site abscess | Any BCG dose | First BCG | BCG revaccinated | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 41 | n = 10 | n = 31 | ||

| Clinical features | ||||

| Time to onset, days | 20 (3–45) | 27 (12–45) | 16 (3–41) | 0.008 |

| Maximum size, cm | 2 (1.5–5.0) | 2.5 (1.5–5.0) | 2 (1.5–4.5) | 0.12 |

| Abscess with discharge | 41 (100%) | 10 (100%) | 31 (100%) | |

| Abscess with persistent discharge (>2w) | 24 (59%) | 5 (50%) | 19 (61%) | 0.39 |

| Abscess with pain/tenderness at site | 40 (98%) | 10 (100%) | 30 (97%) | |

| Management | ||||

| Observation | 34 (83%) | 7 (70%) | 27 (87%) | |

| Maximum size, cm | 2 (1.5–5.0) | 2 (1.5–5.0) | 2 (1.5–4.0) | |

| Time to resolution, days | 27 (2–243) | 28 (8–81) | 22 (2–243) | 0.43 |

| Antimicrobial only | 5 (12%) | 2 (20%) | 3 (10%) | |

| Topical antibiotic (mupirocin) | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Maximum size, cm | 2.5 | — | 2.5 | |

| Time to resolution, days | 28 | — | 28 | |

| Oral antibiotics (cephalexin/flucloxacillin) | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Maximum size, cm | 3.5 | 5.0 | 2.0 | |

| Time to resolution, days | 15 (8–21) | 8 | 21 | |

| Oral isoniazid | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Maximum size, cm | 4.3 (4.0–4.5) | 4.0 | 4.5 | |

| Time to resolution, days | 131 | 113 | 149 | |

| Fine needle aspiration + cephalexin | 2 (5%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Maximum size, cm | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) | 2.0 | 2.0 | |

| Time to resolution, days | 43 (30–56) | 56 | 30 | |

| Lymphadenopathy | Any BCG dose | First BCG | BCG revaccinated | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 48 | n = 18 | n = 30 | ||

| Clinical features | ||||

| Time to onset, days | 6 (1–56) | 6 (1–56) | 6 (1–42) | 0.29 |

| Maximum size, cm | 1.8 (0.5–4.0) | 1.8 (0.5–4.0) | 1.5 (0.5–3.0) | 0.46 |

| No. (%) with pain/tenderness at site | 30 (63%) | 14 (78%) | 16 (53%) | 0.13 |

| Time to resolution, days | 4 (1–30) | 6 (1–30) | 3 (1–14) | 0.47 |

Categorical variables are reported as number (%), continuous variables are reported as median (range).

Fig. 2. Injection site abscess onset.

Time at which injection site abscess apparent after BCG vaccination.

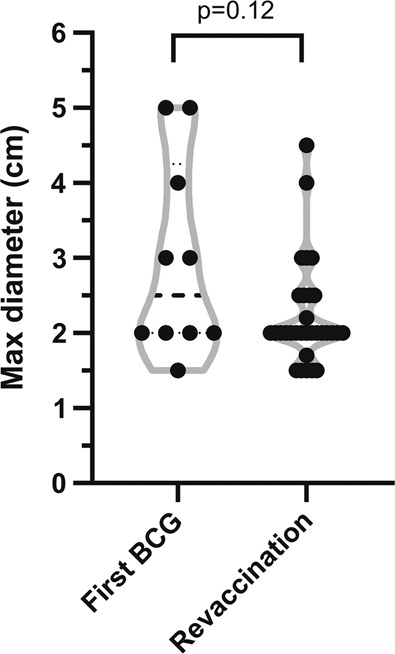

The median diameter was 2.0 cm (IQR 2.0–2.5) (Fig. 3). All abscesses, except for one, were discharged (most commonly ‘yellow cloudy’ fluid) and 24/41 (59%) had persistent discharge for more than 2 weeks. All participants, except for one, experienced pain or tenderness at the abscess site. One participant with a 5.0 cm abscess presented to an emergency department with severe injection site pain. Three participants, with 4.0, 2.5 or 2.0 cm abscess each, had associated axillary lymphadenopathy.

Fig. 3. Injection site abscess size.

Maximum diameter of injection site abscess.

The safety medical doctors (SMDs) recommended a conservative approach for all, except two participants who were referred to an Infectious Diseases specialist due to persistent large abscesses (≥4.0 cm diameter). External providers prescribed antimicrobial treatment in 7/41 (17%) participants, including two who additionally self-performed fine needle aspiration and two who received isoniazid treatment (both negative interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) results). The remaining cases (34/41, 83%) resolved spontaneously without treatment, in a median time of 27 days (IQR 11–45).

Factors associated with the development of BCG injection site abscess

In the univariate analysis (Table 1), an abscess was more common among medical practitioners compared to other HCW, those with a history of prior BCG vaccination, and those in study site D. An abscess was less likely in participants vaccinated by trained vaccinators compared with experienced vaccinators, with BCG batch 118017 F and in study site B. All factors remained significant when adjusted for revaccination, except for the participant role. In the multivariate analysis, revaccination (OR 3.61, 95% CI 1.74–7.51) and study site (site D, OR 3.94, 95% CI 2.09–7.44) were the only two factors associated with an injection site abscess.

There was no significant association with age group, sex, history of living in tuberculosis (TB) endemic country or prior positive tuberculin skin test (TST). All participants with an injection site abscess had no known previous latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI). Of the 27 (67%) participants who developed an injection site abscess and had an IGRA test 3 months post vaccination, all had negative IGRA results.

BCG-associated lymphadenopathy

Lymphadenopathy was reported in 48/1387 (3%) BCG-vaccinated participants. Reported lymphadenopathy comprised: ipsilateral axillary (n = 22, 46%), axillary and cervical (n = 6, 12%), axillary and supraclavicular (n = 1, 2%), cervical (n = 15, 31%), submandibular (n = 2, 4%) or supraclavicular (n = 2, 4%). The median time to onset was 6 days (IQR 3–9) after vaccination (Table 2).

The median diameter was 1.8 cm (IQR 1–2), and 30/48 (63%) participants experienced overlying tenderness. None were suppurative or had overlying redness. All self-resolved, in a median time of 3 days (IQR 2–8). One participant was treated with isoniazid for a concomitant injection site abscess of 4.0 cm diameter.

Two participants took prescribed opioid analgesia for axillary pain associated with lymphadenopathy; one took codeine for two days and the other for buprenorphine for four days following an emergency department presentation.

Factors associated with the development of BCG lymphadenopathy

In the univariate analysis (Table 1), lymphadenopathy was more common among laboratory and research scientists, and less likely in males and in older participants. All factors remained significant when adjusted for revaccination. In the multivariate analysis, revaccination (OR 2.11, 95% CI 1.14–3.95), in addition to scientist role (OR 4.3, 95% CI 1.70–10.88), male sex (OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.13–0.86) and older age group (OR 0.35 95% CI 0.16–0.75) influenced the risk of lymphadenopathy.

There was no significant association with study site, BCG batch, vaccinator experience, history of living in TB endemic country, prior positive TST or LTBI.

Discussion

In this large study of over 1000 HCW recruited in Australia and actively followed for AEFI, we assessed the incidence and factors predictive of BCG injection site abscess and regional lymphadenopathy.

Studies reporting BCG injection site abscesses are scarce. However, the observed rate of injection site abscess in our study is similar to the reported 2.5% incidence in another Australian study in which half of the participants were children1 and 2.5% in a French study6 in children (Table 3).

Table 3.

Previously reported incidence of BCG-related adverse reactions.

| Source country BCG strain age at BCGa | BCG | Injection site abscess | Regional lymphadenopathy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | Risk (95% CI) | n/N | Risk (95% CI) | Comments for lymphadenopathy | ||

| Adults | ||||||

|

BRACE Australia BCG-Denmark (AJ Vaccines) 19–74 y |

All | 41/1387 | 3.0% (21/1000 to 38/1000) | 48/1387 | 3.5% (33/1000 to 36/1000) | Any size |

| V | 10/673 | 1.5% (6/1000 to 24/1000) | 18/673 | 2.7% (14/1000 to 39/1000) | All were non-suppurative | |

| R | 31/714 | 4.3% (28/1,000 to 58/1000) | 30/714 | 4.2% (27/1,000 to 57/1000) | ||

|

Hatherill et al.34, 2014 South Africa BCG-Denmark (SSI) 18–40 y |

R | NA | — | 10/72 | 14% (53/1,000 to 225/1000) | All 72 axillary and had prior positive TST >15 mm |

| All ages | ||||||

|

Product Characteristics9 BCG-Denmark (AJ vaccines) |

NA | — | <0.1% (≥0.1/1000 to <1/1000) | — | <1% (≥1/1000 to <10/1000) | Size >1.0 cm |

|

Turnbull et al.1, 2002 Australia BCG Connaught (Montreal strain) 1d–54y |

All | 23/918 | 2.5% (15/1000 to 35/1000) | 10/918 | 1.1% (4/1000 to 18/1000) | Size ≥1.5 cm |

|

Ponnighaus et al.35, 1993 Malawi BCG-Glaxo 0–71 y |

R | NA | — | 4/54,865 | 0.01% (0.001/1000 to 0.14/1000) | Only included suppurative lymphadenitis |

| Adolescents | ||||||

|

Nemes et al.15, 2018 South Africa BCG-Denmark (SSI) 12–17 y |

R | NA | — | 2/330 | 0.6% (<1/1000 to 14/1000) | — |

|

Dourado et al.37, 2003 Brazil BCG-Moreau 7–14 y |

All V R |

NA | — |

7/71347 2/11,981 5/59,366 |

0.01% (0.03/1000 to 0.17/1000) 0.02% (<1/1000 to 0.40/1000) 0.01% (0.01/1000 to 0.16/1000) |

Axillary |

|

Cunha et al.38, 2008 Brazil BCG-Moreau 7–14 y |

R | 8/47,307 | 0.02% (0.05/1000 to 0.3/1,1000) | 1/47,307 | 0.002% (<1/1000 to 0.06/1000) | Axillary |

| Children | ||||||

|

Aydinlioglu et al.39, 1993 Turkey BCG-Pasteur 3–12 m |

All | NA | — | 15/219 | 6.8% (34/1000 to 103/1000) | 4 of 15 were suppurative lymphadenitis |

|

Roth et al.11, 2010 Guinea-Bissau BCG-Denmark (SSI) 19m–5y |

All V R |

NA | — |

38/787 14/393 24/394 |

4.8% (33/1000 to 64/1000) 3.6% (17/1000 to 54/1000) 6.1% (37/1000 to 85/1000) |

Axillary LN >1.5 cm |

|

Lotte et al.5, 1984 17 countries BCG intradermal, various strains <12 m |

All | NA | — | 3/4.8mill to 9994/263,000 | Range <0.0001% (East Germany) to 3.8% (Algeria) | Only included suppurative lymphadenitis |

|

Chaves-Carballo et al.40, 1972 Panama (BCG strain NR) Children |

Vb | NA | — | 25/1295 | 1.9% (12/1000 to 27/1000) |

Size ≥1.0 cm 12 of 25 were suppurative lymphadenitis |

|

Kim et al.41, 2016 Korea BCG-Denmark Children |

Vb | NA | — | 5/721 | 0.7% (<1/1000 to 13/1000) |

Any size 3 of 5 were ≥1.5 cm |

|

Nissen et al.42, 2016 Denmark BCG-Denmark (SSI) |

V | NA | — | 13/2118 | 0.6% (3/1000 to 9/1000) |

Size >1.0 cm 10 of 13 were suppurative lymphadenitis |

| Neonates | ||||||

|

Jeena et al.36, 2001 South Africa BCG-Denmark (SSI) Neonates |

V | 123/9763 | 1.3% (10/1000 to 15/1000) | 54/9763 | 0.6% (4/1000 to 7/1000) | Size >1.5 cm |

|

Dommergues et al.6, 2009 France BCG-Denmark (SSI) 1d–6y |

Vb | 60/2435 | 2.5% (18/1000 to 31/1000) | 3/2435 | 0.1% (<1/1000 to 3/1000) |

Size >1.0 cm All three were non-suppurative lymphadenitis |

Abscess minimum diameter size only specified for BRACE Trial (≥1.5 cm) and Dommergues et al. (>1.0 cm).

BCG Bacille Calmette-Guérin, d days, SPC summary of product characteristics, SSI Statens Serum Institute, LN lymph node, m months, mill million, n number of cases, N number of vaccinees, NA not reported, R revaccinated, TST tuberculin skin test, V first BCG vaccination, y years.

aLatest dose.

bPresumed as children <6 years and revaccination not specified.

Despite the persistence of discharge from the injection site abscess in half of the affected participants, the majority of abscesses healed within a month without medical/surgical intervention. In those that were treated, a variety of management strategies were used, highlighting the lack of robust evidence for optimal treatment7. Two trial participants undertook self-directed aspiration of the abscess. No side effects of treatment were reported by these participants.

Definitions for BCG-associated lymphadenopathy vary in the literature8. Ipsilateral regional lymph node enlargement has also been called ‘BCG-associated regional lymphadenitis’, which can be non-suppurative or suppurative, the latter potentially causing significant morbidity. Non-suppurative lymphadenitis (or lymphadenopathy) is commonly considered a normal reaction to BCG vaccination and usually has a benign course with resolution over time, especially if infracentimetric8,9. However, according to the WHO, any BCG-associated local lymphadenitis is a reportable AEFI10.

The incidence of BCG-associated lymphadenopathy in our study was higher than has been previously reported in studies that include both adults and children (Table 3), although data from studies including exclusively adults is limited. In a study in adults with a history of latent TB infection in South Africa, a rate of 14% was reported but the study included only 72 individuals. A large review5 of BCG AEFI from 17 countries reported risk in infants ranging from <0.0001% (East Germany) to 3.8% (Algeria). However, these risks were solely for suppurative lymphadenitis, and were for different time periods in the 1950s to 1970s, using unspecified surveillance methods.

In our study, even though many participants experienced pain or tenderness in their regional enlarged lymph glands, none reported symptoms or signs suggestive of a suppurative lymphadenitis. The higher incidence in our study is likely to be the result of the active surveillance used, with systematic and frequent questioning of participants, a lower threshold for defining lymphadenopathy using a broader definition than previous studies and the higher dose of BCG used in adults compared to studies in infants and children.

The higher incidence of local AEFI in BCG-revaccinated participants is consistent with the higher rate of BCG-associated lymphadenopathy reported in a smaller study in children in Guinea-Bissau11. BCG revaccination programmes have been generally discontinued due to a lack of evidence for efficacy against TB12,13. However, revaccination has been recently reconsidered for the protection of adolescents14,15. In addition, there is growing interest in the broader applications of BCG for its beneficial ‘off-target’ effects on the immune system that protect against a variety of infections, including COVID-1916,17, and its role in the management of autoimmune conditions such as diabetes18. For these off-target effects, BCG revaccination may be required and the increased risks of injection site abscess and regional lymphadenopathy are therefore relevant.

To prevent the risk of AEFI, TST screening of adults prior to BCG vaccination or revaccination has been suggested. We did not find any association between prior history of a positive TST and local adverse event following BCG, in line with the previous studies5. Therefore, TST screening is unlikely to be helpful in screening subjects prior to BCG vaccination.

In addition, none of the participants who developed an injection site abscess had a positive IGRA when tested 3 months after vaccination, suggesting abscess development is unlikely to be associated with LTBI (in a low TB-prevalence setting such as Australia).

Factors associated with the development of BCG injection site abscess included the study site as well as other determinants. Participants vaccinated in one study site were more likely to develop an abscess. In a study in Denmark that found scar prevalence after BCG vaccination varied by study site, it was suggested that differences between vaccinators’ technique was an explanation19. In our study, the proportion of trained and experienced vaccinators varied by study site. In univariate analysis, participants vaccinated by ‘inexperienced’ vaccinators were less likely to develop an abscess than those vaccinated by ‘experienced’. This is somewhat counterintuitive as incorrect administration has been linked to injection site reactions and lymphadenitis2. However, this association did not persist in the multivariate analysis. It is difficult to explain this finding but it is possible that the recently trained vaccinators rapidly gained expertise during the trial.

Batch variability has been shown to affect the frequency of AEFI20. Each study site used two to three different batches. The higher rate of abscess formation with one particular vaccine batch in the univariate analysis was no longer present in the multivariate analysis suggesting the disproportionate use of this batch in one site explained the initial finding.

Factors associated with the development of BCG lymphadenopathy included sex and age. Our finding that lymphadenopathy was more common in females than males is consistent with previous reports of more frequent reporting of AEFI by females1. Gender differences in health-reporting behaviour21 may play a role. However, the influence of sex on immunogenicity has been increasingly recognised for many vaccines22,23, including BCG24,25. Therefore, there may be a plausible biological sex difference in the occurrence of lymphadenopathy post vaccination.

Age-related differences in BCG lymphadenitis frequency amongst children have been reported, with lymphadenitis occurring more commonly in infants less than 6 months old, compared with older children and adults1,8. In our study, the lower risk of lymphadenopathy in older participants may be related to immunosenescence26. With increasing age, alterations in lymph node architecture (such as lymph node fibrosis) and declining node size occurs27. Consistent with this paradigm, in a recent COVID-19 vaccine trial, axillary swelling (suggesting lymphadenopathy) or tenderness was reported less frequently in adults older than 65 years old, compared with younger adults28,29.

There are some limitations to this study. First, our study was confined to adults; the clinical course of BCG abscess and lymphadenitis may differ in infants as the immune response varies with age30,31. Second, lymphadenopathy relied on self-palpation. However, those reporting nodes enlarged more than 1.5 cm in diameter and those with lymphadenopathy persisting more than two weeks had medical assessments arranged. Also, most participants were clinicians and all those reporting possible lymphadenopathy were contacted by an SMD. Third, data on the accuracy of intradermal vaccination techniques were not available for all participants. BCG strain and vaccination technique have been previously reported to influence the frequency of AEFI1,4,6.

Strengths include the use of active safety surveillance and the availability of safety data for 98% of participants, which allowed detailed evaluation of potential risk factors (both host- and vaccination-related) for AEFI. Review of clinical photographs helped the SMD assessment and follow-up.

In conclusion, we found that revaccination was associated with a higher risk of developing a BCG local adverse reaction than initial BCG vaccination. In those who developed an injection site abscess, this occurred earlier in revaccinated participants. Most local reactions self-resolved within 1 month. BCG-associated regional lymphadenopathy, but not injection site abscess, was influenced by age at vaccination and sex. In the low TB endemic setting of this study, a local adverse reaction was not attributable to LTBI. Our study has important implications for BCG vaccination policy in an era when BCG vaccination and revaccination is increasingly being considered for novel applications, including to reduce the impact of COVID-1932.

Methods

Setting and participants

Healthcare workers (HCW) were recruited in Stage 1 of the BRACE trial in six hospitals in Australia from March to May 2020, and randomised in a 1:1 ratio and open-label design to receive BCG vaccine or no BCG32. All participants received influenza vaccine to the contralateral arm within three days. Exclusion criteria comprised any contra-indication to BCG, including previous significant local BCG adverse reaction.

Intervention

Participants randomised to BCG received a single dose of BCG-Denmark (AJ Vaccines, Copenhagen), 0.1 ml (corresponding to 2–8 × 105 colony-forming units of Mycobacterium bovis, Danish strain 1331) intradermally in the left upper arm, using a short (10 mm) bevel needle (25 G to 30 G).

Three different BCG vaccine batches were used. BCG study vaccinators were classified as ‘experienced’ (previous experience in BCG clinics), ‘trained’ (trained in advance for the trial) or ‘learners’ (supervised training during the trial).

The administration was defined as ‘satisfactory’ when an intradermal bleb of 7 mm minimum diameter was documented after vaccination. Participants were informed about the normal expected local reaction to BCG vaccination and were instructed to contact study staff if they had any concerns.

Data collection

Data were collected using REDCap33, including details on vaccine administration, and previous tuberculin skin tests (TST) and BCG vaccinations.

Information on vaccine site evolution and any subsequent lymphadenopathy were collected through participant-completed web-based daily questionnaires for 2 weeks post vaccination (vaccine diary) and at 3 months post vaccination (questionnaire). Serial vaccine site photographs were also collected. Additionally, participants could contact the investigators at any time after vaccination (via e-mail or telephone) if they had any concerns about their injection site.

Active safety surveillance

Safety medical doctors (SMD) were trained for the BRACE trial to actively follow up any participant who reported a potential AEFI. Adverse events were recorded on standard forms. Photographs of potential injection site abscesses were reviewed by SMDs at regular quality and safety team meetings for consensus decision on classification. An interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) test for latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) was arranged 3 months after vaccination for participants with an injection site abscess.

Case definitions

BCG injection site abscess was defined as a localised collection of pus, ≥1.5 cm in diameter at the injection site. BCG-associated lymphadenopathy was defined as palpable regional (axilla or neck) lymph node enlargement. Participants reporting lymphadenopathy ≥1.5 cm in diameter or persistent (>2 weeks duration) were recommended to seek medical assessment.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using StataIC 14.0 (Statacorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The cumulative incidence of AEFI in the 3 months post-BCG vaccination was calculated among participants who provided vaccine safety data. Adverse events were compared between participants whose BCG vaccine was their first and those who had previously received BCG (‘revaccinated’) using Mann–Whitney and Chi-square test. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were determined using univariate logistic regression. Significant factors (p value < 0.2) were included as possible covariates in a multivariate model. Backward stepwise exclusion of factors with p value > 0.05 was done to create the model.

Ethical approval was obtained from The Royal Children’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 62586), with reciprocal ethics and governance approvals at each participating site. All participants provided signed informed consent prior to enrolment.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the BRACE trial participants for making this study possible. We would also like to thank the large number of people involved in establishing the BRACE trial (see Supplementary Material for the BRACE trial Consortium Group), in particular: Dr. Wendy Norton, Dr. Samantha Bannister, Ms. Sonja Elia, Ms. Veronica Abruzzo, Ms. Casey Goodall, Dr. Ellie McDonald, Mr. Richard Hall, Ms. Grace Gell, Dr. Niki Tan, Dr. Joyce Chan, Dr. Susan Hermann, Ms. Erin Latkovic, Ms. Michelle England, Dr. Christina Guo, Dr. Tina Zhou and Dr. Laura Tate.

The Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI) leads the BRACE trial across 36 sites in five countries. It is supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Programme. P.V. is supported by the Australian Government Research Training Programme Scholarship provided by the Australian Commonwealth Government and the University of Melbourne, and an MCRI Ph.D. Top-Up Scholarship. L.F.P. is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation [Early Postdoc Mobility Grant, P2GEP3_178155]. N.C. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant [GNT1197117].

The trial is supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation [INV-017302], the Minderoo Foundation [COV-001], Sarah and Lachlan Murdoch, the Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation [2020-1263 BRACE Trial], Health Services Union NSW, the Peter Sowerby Foundation, the Ministry of Health Government of South Australia, the NAB Foundation, the Calvert-Jones Foundation, the Modara Pines Charitable Foundation, the UHG Foundation Pty Ltd, Epworth Healthcare and individual donors. The sponsors had no role in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation or design of the work: N.C., L.F.P. and P.V. Acquisition of data: P.V. and U.W. Analysis or interpretation of data: P.V., L.F.P. and N.C. Original drafting: P.V. Revising, editing and final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main tables and figures. All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Laure F. Pittet, Nigel Curtis.

Contributor Information

Paola Villanueva, Email: paola.villanueva@rch.org.au.

Nigel Curtis, Email: nigel.curtis@rch.org.au.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41541-021-00421-5.

References

- 1.Turnbull FM, et al. National study of adverse reactions after vaccination with bacille Calmette-Guerin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002;34:447–453. doi: 10.1086/338462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Observed rate of vaccine reactions Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. https://www.who.int/vaccine_safety/initiative/tools/BCG_Vaccine_rates_information_sheet.pdf (2012).

- 3.Fekrvand S, et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases and Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG)-vaccine-derived complications: a systematic review. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020;8:1371–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milstien JB, Gibson JJ. Quality control of BCG vaccine by WHO: a review of factors that may influence vaccine effectiveness and safety. Bull. World Health Organ. 1990;68:93–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lotte A, et al. BCG complications. Estimates of the risks among vaccinated subjects and statistical analysis of their main characteristics. Adv. Tuberc. Res. 1984;21:107–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dommergues MA, et al. Local and regional adverse reactions to BCG-SSI vaccination: a 12-month cohort follow-up study. Vaccine. 2009;27:6967–6973. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villanueva P, Pittet LF, Curtis N. Management of Bacille Calmette-Guérin lymphadenitis and abscess in immunocompetent children: a systematic review. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021;40:1037–1045. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goraya JS, Virdi VS. Bacille Calmette-Guerin lymphadenitis. Postgrad. Med. J. 2002;78:327–329. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.920.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.EMC Electronic medicines compendium. BCG vaccine AJV summary of product characteristics. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/9890#gref (2019).

- 10.World Health Organization. Global Manual on Surveillance of Adverse Events Following Immunization (WHO, 2014).

- 11.Roth AE, et al. Effect of revaccination with BCG in early childhood on mortality: randomised trial in Guinea-Bissau. Bmj. 2010;340:c671. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. WHO statement on BCG revaccination for the prevention of tuberculosis. Bull. World Health Organ. 1995;73:805–806. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bannister S, Sudbury E, Villanueva P, Perrett K, Curtis N. The safety of BCG revaccination: A systematic review. Vaccine. 2021;39:2736–2745. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster M, et al. BCG-induced protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: Evidence, mechanisms, and implications for next-generation vaccines. Immunol Rev. 2021;301:122–144. doi: 10.1111/imr.12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nemes E, et al. Prevention of M. tuberculosis infection with H4:IC31 vaccine or BCG revaccination. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:138–149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benn CS, Fisker AB, Rieckmann A, Sørup S, Aaby P. Vaccinology: time to change the paradigm? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:e274–e283. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30742-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis N, Sparrow A, Ghebreyesus TA, Netea MG. Considering BCG vaccination to reduce the impact of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1545–1546. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31025-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ristori G, Faustman D, Matarese G, Romano S, Salvetti M. Bridging the gap between vaccination with Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) and immunological tolerance: the cases of type 1 diabetes and multiple sclerosis. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018;55:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen TM, et al. Determinants of Bacille Calmette-Guérin scarification in Danish children. Heliyon. 2021;7:e05757. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soh SB, et al. Investigations into an outbreak of suppurative lymphadenitis with BCG vaccine SSI(®) in Singapore. Vaccine. 2014;32:5809–5815. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caroli E, Weber-Baghdiguian L. Self-reported health and gender: the role of social norms. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016;153:220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aaby P, et al. The non-specific and sex-differential effects of vaccines. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:464–470. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0338-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flanagan KL, Fink AL, Plebanski M, Klein SL. Sex and gender differences in the outcomes of vaccination over the life course. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017;33:577–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jensen KJ, et al. Heterologous immunological effects of early BCG vaccination in low-birth-weight infants in Guinea-Bissau: a randomized-controlled trial. J. Infect. Dis. 2015;211:956–967. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freyne B, et al. Neonatal BCG vaccination influences cytokine responses to Toll-like receptor ligands and heterologous antigens. J. Infect. Dis. 2018;217:1798–1808. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crooke SN, Ovsyannikova IG, Poland GA, Kennedy RB. Immunosenescence and human vaccine immune responses. Immun. Ageing. 2019;16:25. doi: 10.1186/s12979-019-0164-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson HL, Smithey MJ, Surh CD, Nikolich-Žugich J. Functional and homeostatic impact of age-related changes in lymph node stroma. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:706. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention- National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD). Local reactions, systemic reactions, adverse events, and serious adverse events: Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/moderna/reactogenicity.html (2020)

- 29.Baden LR, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simon AK, Hollander GA, McMichael A. Evolution of the immune system in humans from infancy to old age. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2015;282:20143085–20143085. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whittaker E, Nicol MP, Zar HJ, Tena-Coki NG, Kampmann B. Age-related waning of immune responses to BCG in healthy children supports the need for a booster dose of BCG in TB endemic countries. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:15309–15309. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33499-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pittet LF, et al. BCG vaccination to reduce the impact of COVID-19 in healthcare workers: protocol for a randomised controlled trial (BRACE trial) BMJ Open. 2021;11:e052101. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris PA, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hatherill M, et al. Safety and reactogenicity of BCG revaccination with isoniazid pretreatment in TST positive adults. Vaccine. 2014;32:3982–3988. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ponnighaus JM, et al. The Karonga prevention trial: a leprosy and tuberculosis vaccine trial in Northern Malawi - I: methods of the vaccination phase. Lepr. Rev. 1993;64:338–356. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19930039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeena PM, Chhagan MK, Topley J, Coovadia HM. Safety of the intradermal Copenhagen 1331 BCG vaccine in neonates in Durban, South Africa. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001;79:337–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dourado I, et al. Rates of adverse reactions to first and second doses of BCG vaccination: results of a large community trial in Brazilian schoolchildren. Int J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2003;7:399–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cunha SS, et al. BCG revaccination does not protect against leprosy in the Brazilian Amazon: a cluster randomised trial. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2008;2:e167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aydinlioglu H, et al. The decline of BCG immunity after neonatal vaccination: what about revaccination at one year? Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 1993;7:334–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1993.tb00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chaves-Carballo E, Sanchez GA. Regional lymphadenitis following BCG vaccination (BCGitis). Clinical comments based upon 25 instances among 1295 childhood vaccinees. Clin. Pediatr. 1972;11:693–697. doi: 10.1177/000992287201101211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim J, et al. The incidence rate of lymphadenitis after Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccination. [Korean] Pediatr. Infect. Vaccin. 2016;23:54–61. doi: 10.14776/piv.2016.23.1.54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nissen TN, et al. Adverse reactions to the Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine in new-born infants-an evaluation of the Danish strain 1331 SSI in a randomized clinical trial. Vaccine. 2016;34:2477–2482. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main tables and figures. All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.