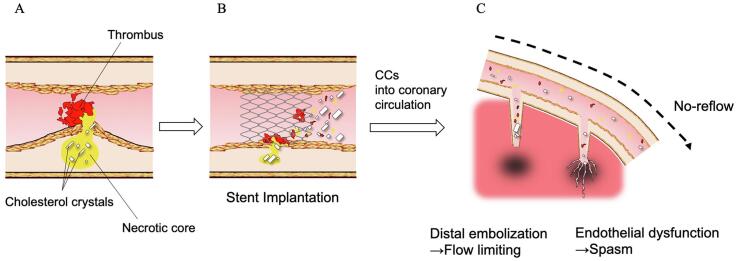

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction, Optical coherence tomography, Cholesterol crystal, No reflow

Abbreviations: PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CC, cholesterol crystal; OCT, optical coherence tomography; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; SCAD, spontaneous coronary artery dissection; TCFA, thin-cap fibroatheroma

Highlight

-

•

The number of in vivo cholesterol crystals at the culprit plaque is increased in patients with the no-reflow phenomenon.

-

•

The number of cholesterol crystals, lipid arch, and ostium lesion are independent predictors for the no-reflow phenomenon after PCI.

-

•

The combination of the number of cholesterol crystals and lipid arc can improve the prediction ability for the no-reflow phenomenon.

Abstract

Background

The release of lipid-laden plaque material subsequent to ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) may contribute to the no-reflow phenomenon. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between in vivo cholesterol crystals (CCs) detected by optical coherence tomography (OCT) and the no-reflow phenomenon after successful percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with acute STEMI.

Methods

We investigated 182 patients with STEMI. Based on the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow grade after PCI, patients were divided into a no-reflow group (n = 31) and a reflow group (n = 151). On OCT, CCs were defined as thin, high-signal intensity regions within a plaque. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to determine predictors for the no-reflow phenomenon.

Results

The prevalence of CCs was higher in the no-reflow group than the reflow group (no-reflow group, 77% vs. reflow group, 53%; p = 0.012). The multivariable logistic model showed that the CC number, lipid arc and ostial lesions were positive independent predictors of no-reflow. The combination of a lipid arc ≥ 139°and CC number ≥ 12 showed good predictive performance for the no-reflow phenomenon (sensitivity, 48%; specificity, 93%; and accuracy, 86%).

Conclusion

In vivo CCs at the culprit plaque are associated with the no-reflow phenomenon after PCI in patients with STEMI. The combination of the number of CCs and lipid arc can predict the no-reflow phenomenon after PCI with a high accuracy of 86%.

1. Introduction

The introduction of reperfusion therapies, such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), has improved the prognosis of patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) [1]. However, 13–18% of STEMI cases fall into a specific poor flow condition [2], [3]. The flow obstruction in the epi-coronary artery is relieved by PCI, although coronary flow can still be impeded at the myocardial level, a phenomenon known as no-reflow [4]. The no-reflow phenomenon has now been established as a predictor for poor outcomes [5].

In vivo coronary imaging studies have revealed that distal embolization of thrombi and/or plaque contents are considered to be the major cause of the no-reflow phenomenon [2], [6], [7]. However, it is still unclear what other kinds of material contribute to developing the no-reflow phenomenon. An in vivo study reported that catheter-derived materials from patients with the no-reflow phenomenon contained more cholesterol crystals (CCs) [6], suggesting that the release of CCs from atheromatous plaque by PCI contributes to the development of the no-reflow phenomenon. However, no in vivo study has addressed a relationship between in vivo CCs at the culprit plaque and the no-reflow phenomenon in patients with AMI due to the lack of an in vivo imaging tool for CCs.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a high-resolution imaging technique that provides a maximum axial resolution of 10 µm, which allows the in vivo identification of various plaque characteristics, including plaque rupture, fibrous cap thickness, intraluminal thrombus and intimal vasculature [8]. Very recently, our histopathological OCT comparison study indicated that the current commercially available OCT can identify CCs in vivo [9].

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between in vivo CCs at the culprit plaque and the no-reflow phenomenon after successful PCI in patients with AMI.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

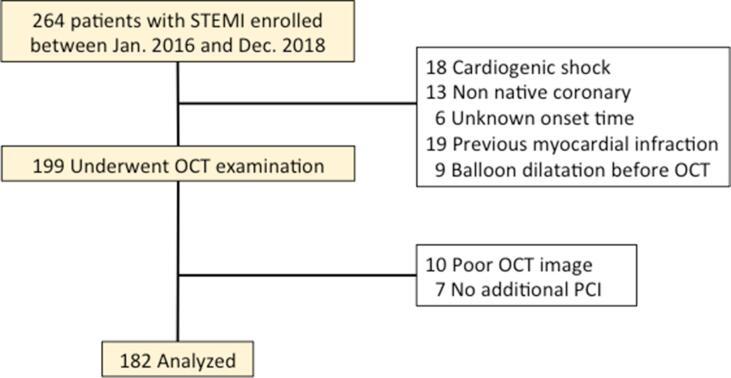

The present study investigated 264 patients with STEMI who were eligible for emergency coronary angiography between January 2016 and December 2018 at Wakayama Medical University. In the present study, patients with STEMI were defined using the criteria in current guidelines [10]. We excluded 65 patents because of cardiogenic shock (n = 18), STEMI occurring in a non-native coronary artery (n = 18), unknown STEMI onset time (n = 6), previous history of MI (n = 19), and balloon dilatation before OCT (n = 9). We performed OCT examination, although patients with large thrombi underwent thromboaspiration, and then excluded 17 patients due to poor OCT image quality (n = 10) and lack of additional intervention (n = 7). Thus, data from 182 patients were analyzed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

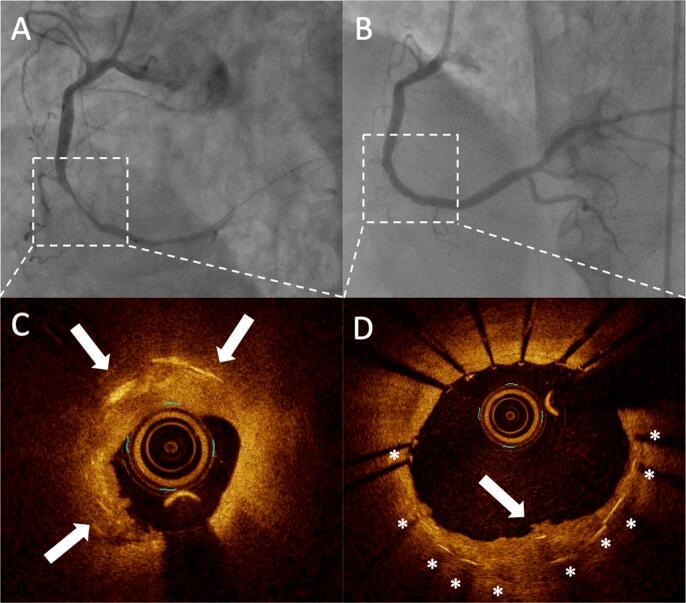

Cholesterol crystals at the culprit plaque are associated with acute myocardial infarction with the no-reflow phenomenon. Angiograms showing the lesion responsible for AMI (upper panels, dotted rectangle) and the corresponding optical coherence tomography (OCT) images. OCT shows several thin linear regions of high signal intensity within a plaque (white arrows). Fig. 1B and 1D show post stent implantation images. Cholesterol crystals are found in the protrusion after stent implantation.

This study was approved by the Wakayama Medical University Ethics Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients (approval number: 2442). The participants in this study provided informed consent permitting the use of their data and samples for research. This study was supported by grants from JSPS KAKENHI (17 K09557), (19 K22776) and (20 K17092).

2.2. Angiography and data analysis

Coronary angiography was performed using 5-Fr Judkins-type catheters via femoral or radial arteries. Before angiography, all patients received oral aspirin, an intravenous bolus heparin injection of 5,000 units, and intracoronary isosorbide dinitrate. Culprit lesions were identified based on coronary angiography findings as well as those of electrocardiography and echocardiography.

Quantitative coronary angiographic analysis was performed by an experienced investigator (Ozaki Y), who was blinded to the data and OCT findings, using a validated automated edge detection algorithm (CAAS-5, Pie Medical, Maastricht, the Netherlands). The reference lumen diameters, minimum lumen diameters, and percent diameter stenosis [(1 - minimum lumen diameter/reference lumen diameter) × 100] were measured. The Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade was determined as previously described [11]. Collateral flow was classified according to the Rentrop classification [12]. The no-reflow phenomenon was defined as a TIMI flow grade of 0, 1, or 2 without mechanical obstruction on final angiograms after PCI. On the basis of the no-reflow phenomenon immediately after stent implantation, patients were divided into a no-reflow group and a reflow group. Patients with the no-reflow phenomenon underwent the intracoronary administration of 1 or 2 mg of nicorandil. No GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors were administered in this study because these inhibitors have not been approved in Japan.

2.3. OCT imaging procedure

After completion of the diagnostic coronary angiography following a careful manual thrombectomy using an aspiration catheter (Thrombuster III®, KANEKA MEDIX, Osaka, Japan), a frequency domain OCT catheter (ILUMIEN and ILUMIEN OPTIS, Abbot Vascular, Santa Clara, California, USA or LUNAWAVE, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) over a 0.356 mm conventional angioplasty guidewire was advanced distal to the lesion using a 6F guiding catheter. X-ray contrast medium at 37 °C (Omnipaque 350 Injection, Daiichi Sankyo Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) was infused through the guiding catheter at 2–4 ml/sec for approximately 3–6 sec using an injector pump (Mark V; Medrad, Pennsylvania, USA). Then, an OCT imaging probe was retracted using a pullback device. The OCT images were digitally stored and analyzed using ImageJ.

2.4. OCT image analysis

All OCT images were analyzed by two experienced OCT investigators who were blinded to the clinical information (Taruya A and Kashiwagi M). These observers became proficient using the training set developed for CC interpretation. Our previous study using this training set showed that the κ-values for inter- and intraobserver variability in the reproducibility of CC assessments by OCT were 0.760 and 0.837, respectively [9]. The lesion characteristics of the culprit site were evaluated according to the consensus document [13]. Plaque rupture was defined by the presence of fibrous cap discontinuity and cavity formation within a plaque [8]. OCT erosion was defined by the absence of fibrous cap disruption but the presence of a thrombus, as described in a previous OCT report [14]. A calcified nodule was defined as an accumulation of nodular calcification (small calcium deposits) with disruption of the fibrous cap on the calcified plate [15]. The definition of spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD), visualized using OCT, was a separation between an intima-media flap and the media-adventitia, with the creation of a false lumen or intramural hematoma [16]. The diagnosis of thin-cap fibroatheroma (TCFA) was based on a pathologically validated OCT definition [17]. We classified the characteristics of residual thrombus and measured the volume in accordance with previous reports [13], [14]. The OCT definition of CCs as thin, high signal intensity, linear regions that do not present confluent punctuate regions but a well-defined area distinguish CCs from macrophages, which lack sharp borders, and was adopted for this clinical study [9], [13] (Fig. 1). We counted the number of CCs within the culprit plaque from distal to proximal sites every 0.5 mm. We defined proximal and distal reference sites as occurring at cross-sections adjacent to the target lesion that have the most normal appearance and are free of lipid plaque. In cases with diffuse atherosclerotic disease, the present study recommends that the reference site is the cross-section with a lipid arc of < 180° [13], [18].

2.5. Reproducibility of CC assessments and CC number by OCT

To assess the reproducibility of CC assessments by OCT, we randomly selected 30 cases. Two independent observers (Katayama Y and Ozaki Y) assessed the presence of CCs and counted the number of CCs. One observer (Ozaki Y) repeated the assessment two weeks after the first assessment. Regarding with the number of CCs, we evaluated the intra- and inter-rater reliability of the OCT using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP™ version 12 for Windows (SAS institute, Cary, NC, USA). Categorical variables are presented as counts (%) and were compared using the chi squared test or Fisher’s exact test if there was an expected cell value of < 5. Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation or median [Q1-Q3] if a continuous distribution could not be assumed and were compared using Student’s t-test. The Wilcoxon test was applied for non-parametric comparisons of continuous variables. The kappa value and ICC were calculated for the intra- and inter-observer variability assessment. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to establish the lipid arc and the number of CCs as predictors of the no-reflow phenomenon. The resulting sensitivity, specificity and area under the curve (AUC) were calculated. The best cutoff value was determined by the maximum sum of sensitivity and specificity. We selected variables with p < 0.02 in the univariate analysis and performed a multivariable logistic regression analysis to determine the predictors for the no-reflow phenomenon after PCI. OR indicates the unit’s odds ratio, and the p-value was calculated by the chunk test. The net reclassification improvement (NRI) calculation was performed using R software (version 4.0.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Significance in all analyses was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics and clinical results for both groups are summarized in Table 1. The no-reflow phenomenon was observed in 31 (17%) of the patients. Differences were not observed in the incidence of classical coronary risk factors between the two groups. No significant difference was observed in the time from onset to angiography between the two groups (no-reflow 302 ± 181 vs. reflow 290 ± 255 min, p = 0.805). Peak creatine kinase-MB levels after PCI were higher in the no-reflow group (no-reflow 381 ± 252 vs. reflow 253 ± 212 IU/L, p = 0.004). The ratio of Eo to WBC after PCI was higher in the no-reflow group (no-reflow 3.6 ± 2.7 vs. reflow 2.4 ± 2.1 %, p = 0.022).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and clinical results.

| No-reflow group (n = 31) |

Reflow group (n = 151) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 70 ± 13 | 70 ± 12 | 0.796 |

| Male | 25 (80) | 106 (70) | 0.238 |

| Hypertension | 24 (77) | 106 (70) | 0.418 |

| Dyslipidemia | 17 (55) | 74 (49) | 0.554 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (35) | 54 (36) | 0.977 |

| Obesity | 11 (35) | 38 (25) | 0.238 |

| Current smoking | 14 (45) | 79 (52) | 0.468 |

| Family history of IHD | 3 (10) | 22 (15) | 0.579 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 7 (23) | 24 (16) | 0.367 |

| Time from onset to angiography, min | 302 ± 181 | 290 ± 255 | 0.805 |

| Peak CK-MB levels, IU/L | 381 ± 252 | 253 ± 212 | 0.004 |

| Eo,/L | 219 ± 146 | 166 ± 152 | 0.112 |

| Eo/WBC, % | 3.6 ± 2.7 | 2.4 ± 2.1 | 0.022 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.47 ± 0.67 | 0.70 ± 2.38 | 0.595 |

Values are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation. IHD = ischemic heart disease; CK = creatine kinase; MB = myocardial band; Eo = eosinophil; WBC = white blood cell; CRP = C-reactive protein.

3.2. Angiographic and PCI procedure findings

The angiographic and PCI procedure findings are summarized in Table 2. Approximately 40% of patients underwent thromboaspiration in the two groups. The prevalence of ostial lesions was higher in the no-reflow group than in the reflow group (no-reflow 23%, vs reflow 7%, p = 0.009). The balloon diameter or stent diameter was larger in the no-reflow group than the reflow group (no-reflow 3.36 ± 0.47 mm vs reflow 3.04 ± 0.57 mm, p = 0.005).

Table 2.

Angiographic and PCI procedure findings.

| No-reflow group (n = 31) |

Reflow group (n = 151) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vessel-containing lesion | 0.173 | ||

| LAD | 20 (65) | 70 (46) | |

| LCx | 1 (3) | 15 (10) | |

| RCA | 10 (32) | 66 (44) | |

| Calcification | 5 (16) | 25 (17) | 0.953 |

| Ostial lesion | 7 (23) | 11 (7) | 0.009 |

| Bifurcation lesion | 15 (48) | 67 (44) | 0.682 |

| TIMI flow at initial angiogram | 0.121 | ||

| Grade 0 | 22 (71) | 88 (58) | |

| Grade 1 | 4 (13) | 14 (9) | |

| Grade 2 | 4 (13) | 47 (31) | |

| Grade 3 | 1 (3) | 2 (1) | |

| QCA analysis | |||

| Reference vessel diameter, mm | 3.36 ± 0.61 | 3.10 ± 0.64 | 0.066 |

| Minimum lumen diameter, mm | 0.15 ± 0.29 | 0.27 ± 0.36 | 0.088 |

| % Diameter stenosis | 95 ± 10 | 90 ± 14 | 0.052 |

| Lesion length, mm | 24 ± 9 | 22 ± 10 | 0.221 |

| Procedure | |||

| IABP use | 6 (19) | 23 (15) | 0.568 |

| Thromboaspiration | 13 (42) | 60 (40) | 0.820 |

| Stent use | 29 (94) | 129 (85) | 0.380 |

| Balloon diameter or stent diameter, mm | 3.36 ± 0.47 | 3.04 ± 0.57 | 0.005 |

| Balloon length or stent length, mm | 25 ± 9 | 22 ± 8 | 0.128 |

| Final inflation pressure, atm | 13.5 ± 2.3 | 12.9 ± 2.5 | 0.238 |

Values are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation. PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; LAD = left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx = left circumflex coronary artery; RCA = right coronary artery; TIMI = Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; QCA = quantitative coronary angiography; IABP = intra-aortic balloon pumping.

3.3. Reproducibility of CC assessments by OCT

The kappa values for the inter- and intra-observer variability were 0.734 and 0.830, respectively. The intra- and inter-rater reliabilities of the number of CCs had an ICC (1, 2) value of 0.949 and ICC (2, 2) value of 0.814, respectively.

3.4. OCT findings

OCT imaging was performed without serious complications, and the findings are summarized in Table 3. The number of CCs was higher in the no-reflow group (no-reflow 12 [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18] vs reflow 4 [0–9], p < 0.001). The lipid arc was also larger in the no-reflow group than in the reflow group (no-reflow 180 [103–220] degree vs reflow 96 [50–160] degree, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

OCT findings.

| No-reflow group (n = 31) |

Reflow group (n = 151) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plaque character | 0.080 | ||

| Fibrous plaque | 5 (16) | 33 (22) | |

| Lipid plaque | 25 (81) | 93 (62) | |

| Calcification | 1 (3) | 25 (17) | |

| TCFA | 18 (58) | 51 (34) | 0.011 |

| Thrombus | 28 (90) | 141 (93) | 0.467 |

| Thrombus characteristics | 0.320 | ||

| Erythrocyte-rich thrombus | 15 (54) | 95 (67) | |

| Platelet-rich thrombus | 4 (14) | 12 (9) | |

| Mix-type thrombus | 9 (32) | 34 (24) | |

| Etiology | |||

| Plaque rupture | 23 (74) | 88 (58) | 0.098 |

| OCT erosion | 5 (16) | 31 (21) | 0.805 |

| Calcified nodule | 0 (0) | 14 (9) | 0.132 |

| Presence of CCs | 24 (77) | 80 (53) | 0.012 |

| Number of CCs | 12 [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18] | 4 [0–9] | < 0.001 |

| Length of CCs, µm | 160 [10–210] | 20 [0–180] | 0.025 |

| Lipid arc, degree | 180 [103–220] | 96 [50–160] | < 0.001 |

| Measurement | |||

| Volume of thrombus, mm3 | 8.79 ± 6.78 | 10.76 ± 9.99 | 0.298 |

| Reference lumen area, mm2 | 9.15 ± 3.69 | 7.92 ± 3.52 | 0.080 |

| Minimum lumen area, mm2 | 1.67 ± 0.74 | 1.59 ± 1.09 | 0.680 |

| % area stenosis, % | 77 ± 17 | 74 ± 19 | 0.554 |

Values are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation. OCT = optical coherence tomography; TCFA = thin-cap fibroatheroma; CCs = cholesterol crystals.

3.5. Multivariate analysis as determinants of no-reflow

The results of multivariate analysis are summarized in Table 4. The ostial lesions (p = 0.021), CC number (p = 0.006), and lipid arc (p = 0.013) were independent predictors of the no-reflow phenomenon.

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis for no-reflow prediction.

| Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Age | 0.99 (0.97–1.03) | 0.795 | |||

| Male | 1.77 (0.68–4.61) | 0.224 | |||

| Hypertension | 1.46 (0.59–3.62) | 0.409 | |||

| Dyslipidemia | 1.29 (0.58–2.75) | 0.554 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.99 (0.44–2.22) | 0.977 | |||

| Current smoker | 0.75 (0.35–1.63) | 0.468 | |||

| Family history of IHD | 0.63 (0.18–2.25) | 0.454 | |||

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.54 (0.60–3.98) | 0.381 | |||

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.93 (0.70–1.23) | 0.544 | |||

| Calcification | 0.97 (0.34–2.77) | 0.953 | |||

| Ostial lesion | 3.71 (1.31–10.52) | 0.019 | 4.28 (1.28–13.02) | 0.021 | |

| Bifurcation | 1.18 (0.54–2.55) | 0.683 | |||

| TIMI flow grade 0 at initial angiogram | 1.80 (0.78–4.17) | 0.160 | |||

| Reference vessel diameter, mm | 1.77 (0.96–3.25) | 0.065 | |||

| Lesion length, mm | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.238 | |||

| IABP use | 1.34 (0.49–3.61) | 0.576 | |||

| Balloon diameter or stent diameter, mm | 2.84 (1.15–7.01) | 0.021 | |||

| Balloon length or stent length, mm | 1.02 (0.99–1.06) | 0.238 | |||

| Final inflation pressure | 1.10 (0.94–1.29) | 0.243 | |||

| Plaque rupture | 2.06 (0.86–4.90) | 0.090 | |||

| OCT erosion | 0.74 (0.26–2.10) | 0.568 | |||

| Number of CCs | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | 0.001 | 1.06 (1.02–1.10) | 0.006 | |

| Length of CCs, µm | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.028 | |||

| Lipid arc | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | < 0.001 | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | 0.013 | |

| TCFA | 2.71 (1.23–5.98) | 0.012 | 1.44 (0.58–3.57) | 0.427 | |

ORs indicate unit odds ratios, and p-values were calculated by the chunk test. CRP, reference vessel diameter, lesion length, stent diameter, stent length, final inflation pressure, CC number, CC length and lipid arc were defined as continuous variables. IHD = ischemic heart disease; CRP = C-reactive protein; TIMI = thrombolysis in myocardial infarction; IABP = intra-aortic balloon pumping; OCT = optical coherence tomography; CCs = cholesterol crystals; TCFA = thin-cap fibroatheroma.

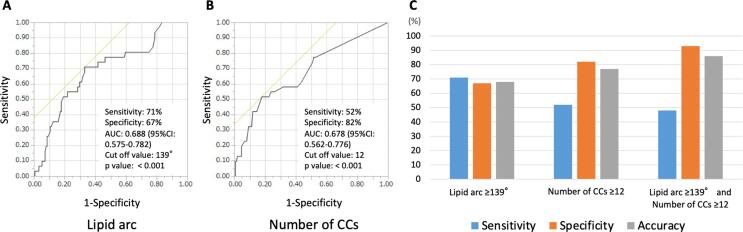

3.6. Diagnostic value of lipid arc and the number of CCs for no-reflow

As shown in Fig. 2, a cutoff value of lipid arc = 139° had the highest area under the curve (0.688, CI 95% 0.575–0.782, p < 0.001) for predicting the no-reflow phenomenon. The confusion matrices for the sensitivity and specificity calculation were summarized in Supplementary table 1. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy were 71%, 67%, 31%, 92% and 68%, respectively. The cutoff value of the number of CCs = 12 had the highest area under the curve (0.678, CI 95% 0.562–0.776, p = 0.001) for predicting the no-reflow phenomenon. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy were 52%, 82%, 37%, 89% and 77%, respectively. The combination of the lipid arc ≥ 139° and the number of CCs ≥ 12 shows moderate sensitivity but high specificity and very good accuracy for predicting the no-reflow phenomenon (sensitivity, 48%; specificity, 93%; positive predictive value, 60%; negative predictive value, 90%; and accuracy, 86%). The NRI was applied to estimate the incremental predictive ability of the number of CCs based on when the value is added to the lipid arc. The NRI calculation showed that combining the lipid arc with the number of CCs significantly improved the diagnostic accuracy (NRI [95 %CI], 0.567 [0.1894–0.9446], p = 0.0033) for the prediction of the no-reflow phenomenon compared to the lipid arc alone (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Diagnostic ability of lipid arc and number of cholesterol crystals for predicting no-reflow phenomenon. (A) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the lipid arc for predicting the no-reflow phenomenon A cutoff value of lipid arc = 139° had the highest area under the curve (0.688, CI 95% 0.575–0.782, p < 0.001) for predicting the no-reflow phenomenon. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were 71%, 67%, and 68%, respectively. (B) ROC curve of the number of cholesterol crystals (CCs) for predicting the no-reflow phenomenon A cutoff value of the number of CCs = 12 had the highest area under the curve (0.678, CI 95% 0.562–0.776, p < 0.001) for predicting the no-reflow phenomenon. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were 52%, 82%, and 77%, respectively. (C) Comparison of diagnostic accuracy for predicting the no-reflow phenomenon. The combination of the lipid arc > 139° and the number of CCs > 12 shows moderate sensitivity but high specificity and very good accuracy for predicting the no-reflow phenomenon (sensitivity 48%, specificity 93%, and accuracy 86%, respectively).

Fig. 3.

4. Discussion

In this study, we found that 1) the prevalence and number of in vivo CCs were higher in the no-reflow group than the reflow group; 2) the number of in vivo CCs, lipid arc, and ostial lesions were independent predictors of the no-reflow phenomenon; and 3) the combination of the CC number and lipid arc improved the diagnostic accuracy for predicting no-reflow.

4.1. No-reflow phenomenon and in vivo CCs

In this study, we first revealed the relationship between the no-reflow phenomenon and in vivo CCs at the culprit plaque in patients with STEMI.

The concept of the no-reflow phenomenon was proposed in an experimental study by Kloner et al. [19]. After the release of prolonged coronary occlusion, pericardial coronary flow was impeded by damage to the myocardial circulation level by a variety of pathological changes, including endothelial swelling, myocyte edema, capillary plugging by neutrophils and microthrombi, and neutrophil infiltration [19]. In a clinical setting, a contrast echocardiography study by Ito et al. first reported the occurrence of no-reflow in patients with AMI [5]. The no-reflow phenomenon is caused by the combination of reperfusion injury and distal embolization. It would be difficult to distinguish between the no-reflow phenomenon caused by this reperfusion injury and the slow flow or no-reflow caused by distal embolism. A previous study showed that the no-reflow phenomenon caused by reperfusion injury was associated with the duration of occlusion [20]. In our study, no significant difference was observed in the time from onset to angiography between the two groups. Compared with experimental studies, our IVUS study revealed that the presence of lipid-pool-like images is associated with the no-reflow phenomenon [2] and that the reduction in volume of the culprit plaque was inversely correlated with the coronary flow after PCI [21]. Okamura et al. [22] reported that the mean number of emboli throughout PCI was higher in patients with no reflow than in those with reflow using a Doppler guidewire. Kotani et al. reported that plaque debris containing the contents of a necrotic core, including inflammatory cells, cholesterol debris, and thrombi, are often retrieved from the distal portions of infarct-related arteries after PCI [6]. Kawamoto et al. reported that suspicious necrotic core components might be related to the liberation of small embolic particles during coronary stenting [7]. Thus, the predominant mechanism of the no-reflow phenomenon in patients with AMI is considered distal embolization of the contents of advanced fibroatheromas via the mechanical stress of PCI [23]. Based on this evidence, we propose two potential interpretations of our findings indicating that in vivo CCs at the culprit plaque are associated with the no-reflow phenomenon.

One interpretation is that the detection of CCs could increase the diagnostic accuracy of OCT for advanced fibroatheromas, of which contents are thought to cause the no-reflow phenomenon. Although the lipid arc by OCT that is associated with total atheroma volume by intravascular ultrasound [24] is a powerful predictor for the no-reflow phenomenon [25], it is well known from OCT and histologic studies that OCT cannot clearly distinguish the lipid contents within advanced atheromatous plaques from those in plaques with other characteristics [13]. Recently, a pathological study by Jinnnouchi et al. found that OCT identified CCs more frequently in the advanced atheromatous coronary plaque, suggesting that the detection of CCs by OCT may guide the identification of advanced atheromatous plaque [26].

The other interpretation is that CCs themselves could contribute to the no-reflow phenomenon, which is more likely to develop according to the number of CCs, suggesting that CCs themselves play a role in the development of no reflow. We have demonstrated that the numbers of CCs by OCT is correlated with the number of clefts in the pathological section [9]. Kotani et al. reported that catheter-derived materials from AMI patients with the no-reflow phenomenon contained a higher number of CCs [6]. The CC cluster area was negatively correlated with the TIMI flow grade in patients with AMI after PCI [27]. Extensive CC emboli plugging the distal coronary artery were noted in patients who died from the no-reflow phenomenon [28]. These results suggest that distal embolization of CCs is one of the underlying mechanisms for the development of the no-reflow phenomenon after PCI. Furthermore, severe microvascular dysfunction or loss of integrity is thought to be one of the principal causes of the no-reflow phenomenon [29]. The release of CCs from plaques into artery circulation can cause endothelial dysfunction and vasomotor dysfunction, resulting in subsequent no reflow [30]. We speculate that the release of CCs from plaques by PCI may cause endothelial dysfunction and subsequent vasomotor dysfunction. Substances that can dissolve CCs, including statins, aspirin, and high-density lipoproteins, have protective effects against the no-reflow phenomenon [27], [31], [32], [33]. Regardless of the interpretation, further investigations should be planned on the role of CCs in the no-reflow phenomenon.

4.2. Clinical implications

Because the no-reflow phenomenon has been associated with a worse prognosis, prediction of patients at high risk for no reflow before PCI would be beneficial to improve patient outcomes [34]. Our previous studies have indicated that the presence of lipid-pool-like images and lipid quadrants are predictors for the no-reflow phenomenon [2], [25]. In addition to lipids, the number of CCs is also an independent predictor for the no-reflow phenomenon. The net improvement in reclassification showed that the combination of the CC number and lipid arc improves the diagnostic accuracy for predicting the no-reflow phenomenon. We think that the high accuracy and positive predictive value are strengths for using the CC number and lipid arc when designing a treatment strategy. At the same time, the modest sensitivity should be considered. High resolution OCT could improve the sensitivity for prediction of the no-reflow phenomenon.

4.3. Study limitations

We are aware of several limitations in this study. First, this was a retrospective single-center study. Because of the observational nature of the study, our findings can be considered as hypothesis generating. Moreover, the no-reflow phenomenon may be limited in time; therefore, certain instances of this phenomenon may have been missed due to the retrospective nature of the study. Prospective studies should be performed to confirm our hypothesis. The procedure of PCI for STEMI was determined by the physician. Hence, selection bias may have occurred. Second, research with OCT in the setting of STEMI is hindered by multiple factors that introduce a substantial level of randomness and uncertainty to the results, namely, a thrombus randomly masking certain sectors of the vessel, tissue damage provoked by the wire, thrombus aspiration or the optical catheter itself. Some CCs were missed, possibly due to the spatial resolution and limited light penetration of current commercially available OCT systems. A pathological study reported the specific angle and distance from the exiting light source in OCT detection of CCs [26]. Because we counted the number of CCs within the culprit plaque from distal to proximal sites every 0.5 mm, some CCs between frames might have been missed. Furthermore, few histological studies have validated CCs from other crystals. Third, thrombectomy using an aspiration device was performed before OCT imaging. Although the routine use of thromboaspiration devices is not recommended following the results from the TASTE and TOTAL trials, approximately 40% of patients underwent thromboaspiration in our study [35], [36]. A thrombectomy catheter might have modified the culprit lesion morphologies. Furthermore, OCT systems cannot image the lesion morphology through a thick thrombus. In such cases, some plaque rupture may have been missed or misdiagnosed as the size of the lipid arc. Finally, the number of CCs ≥ 12 alone or in combination with lipids ≥ 139° showed relatively low sensitivity, suggesting that other factors are also involved in the occurrence of no reflow.

5. Conclusions

In vivo CCs at the culprit plaque are associated with the no-reflow phenomenon after PCI in patients with AMI. The combination of the CC number and lipid arc can improve the prediction accuracy for the no-reflow phenomenon.

Informed consent

This study was approved by the Wakayama Medical University Ethics Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients (approval number: 2442).

Funding

JSPS KAKENHI (17K09557), (19K22776) and (20K17092)

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Footnote. These authors take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretation.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcha.2022.100953.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Keeley E.C., Boura J.A., Grines C.L. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361(9351):13–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka A., Kawarabayashi T., Nishibori Y., Sano T., Nishida Y., Fukuda D., Shimada K., Yoshikawa J. No-reflow phenomenon and lesion morphology in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;105(18):2148–2152. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000015697.59592.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng C., Liu X.-B., Bi S.-J., Lu Q.-H., Zhang J., den Uil C. Serum cystatin C levels relate to no-reflow phenomenon in percutaneous coronary interventions in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):e0220654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eeckhout E., Kern M.J. The coronary no-reflow phenomenon: a review of mechanisms and therapies. Eur. Heart J. 2001;22:729–739. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito H., Maruyama A., Iwakura K., Takiuchi S., Masuyama T., Hori M., Higashino Y., Fujii K., Minamino T. Clinical implications of the 'no reflow' phenomenon. A predictor of complications and left ventricular remodeling in reperfused anterior wall myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1996;93(2):223–228. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotani J.-I., Nanto S., Mintz G.S., Kitakaze M., Ohara T., Morozumi T., Nagata S., Hori M. Plaque gruel of atheromatous coronary lesion may contribute to the no-reflow phenomenon in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2002;106(13):1672–1677. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000030189.27175.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawamoto T., Okura H., Koyama Y., Toda I., Taguchi H., Tamita K., Yamamuro A., Yoshimura Y., Neishi Y., Toyota E., Yoshida K. The relationship between coronary plaque characteristics and small embolic particles during coronary stent implantation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007;50(17):1635–1640. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka A., Imanishi T., Kitabata H., Kubo T., Takarada S., Tanimoto T., Kuroi A., Tsujioka H., Ikejima H., Ueno S., Kataiwa H., Okouchi K., Kashiwaghi M., Matsumoto H., Takemoto K., Nakamura N., Hirata K., Mizukoshi M., Akasaka T. Morphology of exertion-triggered plaque rupture in patients with acute coronary syndrome: an optical coherence tomography study. Circulation. 2008;118(23):2368–2373. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.782540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katayama Y., Tanaka A., Taruya A., Kashiwagi M., Nishiguchi T., Ozaki Y., Matsuo Y., Kitabata H., Kubo T., Shimada E., Kondo T., Akasaka T. Feasibility and clinical significance of in vivo cholesterol crystal detection using optical coherence tomography. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020;40(1):220–229. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.312934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Gara P.T., Kushner F.G., Ascheim D.D., et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:e362–e425. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chesebro J.H., Knatterud G., Roberts R., Borer J., Cohen L.S., Dalen J., Dodge H.T., Francis C.K., Hillis D., Ludbrook P. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Trial, Phase I: a comparison between intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and intravenous streptokinase. Clinical findings through hospital discharge. Circulation. 1987;76(1):142–154. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.1.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peter Rentrop K., Cohen M., Blanke H., Phillips R.A. Changes in collateral channel filling immediately after controlled coronary artery occlusion by an angioplasty balloon in human subjects. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1985;5(3):587–592. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80380-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tearney G.J., Regar E., Akasaka T., Adriaenssens T., Barlis P., Bezerra H.G., Bouma B., Bruining N., Cho J.-M., Chowdhary S., Costa M.A., de Silva R., Dijkstra J., Di Mario C., Dudeck D., Falk E., Feldman M.D., Fitzgerald P., Garcia H., Gonzalo N., Granada J.F., Guagliumi G., Holm N.R., Honda Y., Ikeno F., Kawasaki M., Kochman J., Koltowski L., Kubo T., Kume T., Kyono H., Lam C.C.S., Lamouche G., Lee D.P., Leon M.B., Maehara A., Manfrini O., Mintz G.S., Mizuno K., Morel M.-a., Nadkarni S., Okura H., Otake H., Pietrasik A., Prati F., Räber L., Radu M.D., Rieber J., Riga M., Rollins A., Rosenberg M., Sirbu V., Serruys P.W.J.C., Shimada K., Shinke T., Shite J., Siegel E., Sonada S., Suter M., Takarada S., Tanaka A., Terashima M., Troels T., Uemura S., Ughi G.J., van Beusekom H.M.M., van der Steen A.F.W., van Es G.-A., van Soest G., Virmani R., Waxman S., Weissman N.J., Weisz G. Consensus standards for acquisition, measurement, and reporting of intravascular optical coherence tomography studies: a report from the International Working Group for Intravascular Optical Coherence Tomography Standardization and Validation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;59(12):1058–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jia H., Dai J., Hou J., et al. Effective anti-thrombotic therapy without stenting: intravascular optical coherence tomography-based management in plaque erosion (the EROSION study) Eur. Heart J. 2017;38:792–800. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee T., Mintz G.S., Matsumura M., Zhang W., Cao Y., Usui E., Kanaji Y., Murai T., Yonetsu T., Kakuta T., Maehara A. Prevalence, Predictors, and Clinical Presentation of a Calcified Nodule as Assessed by Optical Coherence Tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(8):883–891. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishiguchi T., Tanaka A., Ozaki Y., Taruya A., Fukuda S., Taguchi H., Iwaguro T., Ueno S., Okumoto Y., Akasaka T. Prevalence of spontaneous coronary artery dissection in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care. 2016;5(3):263–270. doi: 10.1177/2048872613504310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujii K., Hao H., Shibuya M., Imanaka T., Fukunaga M., Miki K., Tamaru H., Sawada H., Naito Y., Ohyanagi M., Hirota S., Masuyama T. Accuracy of OCT, grayscale IVUS, and their combination for the diagnosis of coronary TCFA: an ex vivo validation study. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2015;8(4):451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ali Z.A., Maehara A., Généreux P., Shlofmitz R.A., Fabbiocchi F., Nazif T.M., Guagliumi G., Meraj P.M., Alfonso F., Samady H., Akasaka T., Carlson E.B., Leesar M.A., Matsumura M., Ozan M.O., Mintz G.S., Ben-Yehuda O., Stone G.W. Optical coherence tomography compared with intravascular ultrasound and with angiography to guide coronary stent implantation (ILUMIEN III: OPTIMIZE PCI): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10060):2618–2628. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31922-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kloner R.A., Ganote C.E., Jennings R.B. The “no-refow” phenome- non after temporary occlusion in the dog. J Clin Invest. 1974;54:1491–1508. doi: 10.1172/JCI107898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reffelmann T., Kloner R.A. Microvascular reperfusion injury: rapid expansion of anatomic no reflow during reperfusion in the rabbit. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002;283(3):H1099–H1107. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00270.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato H., Iida H., Tanaka A., Tanaka H., Shimodouzono S., Uchida E., Kawarabayashi T., Yoshikawa J. The decrease of plaque volume during percutaneous coronary intervention has a negative impact on coronary flow in acute myocardial infarction: a major role of percutaneous coronary intervention-induced embolization. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004;44(2):300–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamura A., Ito H., Iwakura K., Kawano S., Inoue K., Maekawa Y., Ogihara T., Fujii K. Detection of embolic particles with the Doppler guide wire during coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction: efficacy of distal protection device. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005;45(2):212–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ito H. Etiology and clinical implications of microvascular dysfunction in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int. Heart J. 2014;55(3):185–189. doi: 10.1536/ihj.14-057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie Z, Tian J, Ma L, et al. Comparison of optical coherence tomography and intravascular ultrasound for evaluation of coronary lipid-rich atherosclerotic plaque progression and regression. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015; 16: 1374-1380. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Tanaka A, Imanishi T, Kitabata H, et al. Lipid-rich plaque and myocardial perfusion after successful stenting in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: an optical coherence tomography study. Eur Heart J 2009;30:1348-1355. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Jinnouchi H., Sato Y.u., Torii S., Sakamoto A., Cornelissen A., Bhoite R.R., Kuntz S., Guo L., Paek K.H., Fernandez R., Kolodgie F.D., Virmani R., Finn A.V. Detection of cholesterol crystals by optical coherence tomography. EuroIntervention. 2020;16(5):395–403. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-20-00202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abela G.S., Kalavakunta J.K., Janoudi A., Leffler D., Dhar G., Salehi N., Cohn J., Shah I., Karve M., Kotaru V.P.K., Gupta V., David S., Narisetty K.K., Rich M., Vanderberg A., Pathak D.R., Shamoun F.E. Frequency of Cholesterol Crystals in Culprit Coronary Artery Aspirate During Acute Myocardial Infarction and Their Relation to Inflammation and Myocardial Injury. Am. J. Cardiol. 2017;120(10):1699–1707. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldstein J.A., Grines C., Fischell T., Virmani R., Rizik D., Muller J., Dixon S.R. Coronary embolization following balloon dilation of lipid-core plaques. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(12):1420–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Waha S, Patel MR, Granger CB, et al. Relationship between microvascular obstruction and adverse events following primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: an individual patient data pooled analysis from seven randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:3502-3510. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Gadeela N, Rubinstein J, Tamhane U, et al. The impact of circulating cholesterol crystals on vasomotor function: implications for no-reflow phenomenon. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2011;4:521-529. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Abela G.S. Cholesterol crystals piercing the arterial plaque and intima trigger local and systemic inflammation. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2010;4(3):156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abela G.S., Vedre A., Janoudi A., Huang R., Durga S., Tamhane U. Effect of statins on cholesterol crystallization and atherosclerotic plaque stabilization. Am. J. Cardiol. 2011;107(12):1710–1717. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.02.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams C.W., Abdulla Y.H. The action of human high density lipoprotein on cholesterol crystals. Part 1. Light-microscopic observations. Atherosclerosis. 1978;31:465–471. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(78)90142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehta R.H., Harjai K.J., Cox D., Stone G.W., Brodie B., Boura J., O'Neill W., Grines C.L. PAMI investigators: clinical and angiographic correlates and outcomes of suboptimal coronary flow inpatients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003;42(10):1739–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fröbert O., Lagerqvist B.o., Olivecrona G.K., Omerovic E., Gudnason T., Maeng M., Aasa M., Angerås O., Calais F., Danielewicz M., Erlinge D., Hellsten L., Jensen U., Johansson A.C., Kåregren A., Nilsson J., Robertson L., Sandhall L., Sjögren I., Östlund O., Harnek J., James S.K. Thrombus aspiration during ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369(17):1587–1597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jolly S.S., Cairns J.A., Yusuf S., Meeks B., Pogue J., Rokoss M.J., Kedev S., Thabane L., Stankovic G., Moreno R., Gershlick A., Chowdhary S., Lavi S., Niemelä K., Steg P.G., Bernat I., Xu Y., Cantor W.J., Overgaard C.B., Naber C.K., Cheema A.N., Welsh R.C., Bertrand O.F., Avezum A., Bhindi R., Pancholy S., Rao S.V., Natarajan M.K., ten Berg J.M., Shestakovska O., Gao P., Widimsky P., Džavík V. Randomized trial of primary PCI with or without routine manual thrombectomy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372(15):1389–1398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.