Abstract

Diets link human health with environmental sustainability, offering promising pressure points to enhance the sustainability of food systems. We investigated the health, environmental, and economic dimensions of the current diet in Argentina and the possible effects of six dietary change scenarios on nutrient adequacy, dietary quality, food expenditure, and six environmental impact categories (i.e., GHG emissions, total land occupation, cropland use, fossil energy use, freshwater consumption, and the emission of eutrophying pollutants). Current dietary patterns are unhealthy, unsustainable, and relatively expensive, and all things being equal, an increase in income levels would not alter the health dimension, but increase environmental impacts by 33–38%, and costs by 38%. Compared to the prevailing diet, the six healthier diet alternatives could improve health with an expenditure between + 27% (National Dietary Guidelines) to -5% (vegan diet) of the current diet. These dietary changes could result in trade-offs between different environmental impacts. Plant-based diets showed the lowest overall environmental impact, with GHG emissions and land occupation reduced by up to 79% and 88%, respectively, without significant changes in cropland demand. However, fossil energy use and freshwater consumption could increase by up to 101% and 220%, respectively. The emission of eutrophying pollutants could increase by up to 54% for all healthy diet scenarios, except for the vegan one (18% decrease). We conclude that the health and environmental crisis that Argentina (and other developing countries) currently face could be mitigated by adopting healthy diets (particularly plant-based), bringing in the process benefits to both people and nature.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11625-021-01087-7.

Keywords: Healthy diets, Food system, Land–Water–Food–Energy Nexus, South America, Food affordability, Greenhouse gas emissions

Introduction

Throughout history, humankind has faced major shifts in dietary patterns. However, during the twentieth century, there was an acceleration of dietary changes worldwide, from scarce, plant-based diets based on fresh and unprocessed foods towards diets rich in sugar, fat, salt, animal products, and ultra-processed foods (Popkin 2006). This nutrition transition has caused a major shift in public health challenges from undernutrition-related diseases and neonatal disorders towards Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) related to overconsumption such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases (Fanzo et al. 2018; Bodirsky et al. 2020). At present, unhealthy eating is the most important morbidity and mortality risk factor worldwide (Afshin et al. 2019). Globally, inadequate diets explain 23% of total deaths and the loss of 15% of disability-adjusted life years, with low- and middle-income countries disproportionately affected (Murray et al. 2020).

In addition to being a key factor for human health, food consumption and production affects substantially environmental sustainability (Clark et al. 2018; Fanzo et al. 2021). With its sheer scale, agriculture is one of the human activities with the highest environmental impact and plays a major role in the transgression of planetary boundaries (Campbell et al. 2017). Food systems account for approximately 34% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Crippa et al. 2021), alter the biogeochemical cycles of nitrogen and phosphorus (Cordell et al. 2012; Lassaletta et al. 2016), and occupy nearly 40% of Earth’s land, being the main driver of land-use change, deforestation, and biodiversity loss in tropical and subtropical regions (Arneth et al. 2019; Díaz et al. 2019). Also, agriculture consumes almost 70% of Earth’s freshwater (Hoekstra and Wiedmann 2014) and accounts for a sizeable fraction of the global fossil energy use (Schramski et al. 2020), as well as other valuable and scarce resources such as metals, plastics, wood, and chemical substances (Hajer et al. 2016).

Because of expected population trends, changing demographic structure, and increasing household food waste, projections indicate that the impacts of food systems will continue to increase in the coming decades unless significant changes occur in the ways in which food is produced, transformed, and consumed (Springmann et al. 2018). Some scholars perceive this as a joint health-environmental crisis, and suggest that identifying potential dietary transitions with better health and environmental outcomes to be a global scientific and policy priority (Willett et al. 2019).

As the rest of Latin America, Argentina faces all forms of malnutrition: undernutrition, overweight, stunting, and anemia (Batis et al. 2020; Zapata et al. 2020). However, the country has comparatively lower undernutrition indices, higher overweight prevalence, and a more Western dietary pattern than the rest of the region (Afshin et al. 2017a; NNGS 2019), undergoing a transition where socio-demographic factors play a major role in shaping health profiles (Pou et al. 2017; Tumas et al. 2019). Even though only 6% of the population reaches the recommended intake level of fruits and vegetables (INDEC 2018), and most people do not consume an adequate amount of other major healthy food groups such as legumes, fish, nuts and seeds (Kovalskys et al. 2019), only one-third of the population recognizes following an unhealthy diet (NRFS 2018). This overlooked unhealthy dietary pattern contributes to the high prevalence of NCDs in the country (Afshin et al. 2019).

In addition, Argentina has an agriculture-oriented economy, with food production being a major driver of natural resources’ use and depletion, and environmental degradation (Nanni et al. 2020; Jobbágy et al. 2021). Agriculture is well established and developed in the central part of the country, mainly in the Pampas, and it has expanded in the last decades, particularly towards the warmer and generally drier North (Viglizzo et al. 2011). Accordingly, Argentina faces a combination of the environmental impacts associated with intensive agriculture in developed countries (e.g., eutrophication and ecotoxicity) and those of more extensive agriculture in developing countries (e.g., increase in agricultural area and deforestation) (Pellegrini and Fernández 2018). In fact, the advance of the agricultural frontier at the cost of natural and semi-natural ecosystems, with the consequent loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services, constitutes one of the country's main environmental concerns (MESD 2020). Although the majority of food produced in Argentina is exported, most of the meat, milk, and eggs are consumed domestically, showcasing the importance of terrestrial animal source foods in the country (FAOSTAT 2021). These levels of animal source foods’ consumption are uncommon for a mid-income country, and in particular, the total amount of beef consumed per capita exceeds that of high-income countries (OECD 2021). In this sense, because of the large resource requirements of animal farming (Clark and Tilman 2017), the environmental footprint of the Argentine diet is very high, particularly regarding land use and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Alexander et al. 2016; Arrieta and González 2018; Arrieta et al. 2021a).

While the promotion of healthy diets has been proposed as an important strategy to improve public health, there are many synergies and trade-offs between food, health, and the environment (Clark et al. 2019; Tuomisto 2019). National Dietary Guidelines (NDG) represent a powerful tool for the design of policies that allow to change the population's food consumption patterns, improve public health, and modify food-related environmental footprints (Gonzalez Fischer and Garnet, 2016; Behrens et al. 2017). However, such changes will be determined by the baseline (i.e., the current diet), the target (i.e., the proposed healthy diet), and the production systems supplying the food (Halpern et al. 2019). Thus, changes in the environmental footprint of a given diet will not be the same for all countries, and could even generate different productive and environmental challenges (Tuomisto 2019). Hence, understanding these dimensions of current diets, especially in the light of alternative diets, is critical for assessing synergies and trade-offs, and for promoting integrative, evidence-based public policies in the country.

The present study aimed to assess the health, environmental, and economic implications of potential dietary transitions in Argentina. First, we describe the quality and nutrient adequacy of each of eight modelled diets. Second, we report the environmental impacts of the dietary scenarios at national scale for six impact categories, namely GHG emissions, total land occupation, cropland demand, fossil energy use, freshwater consumption, and emissions of eutrophying pollutants. Third, we compare the daily cost of each diet. Finally, we discuss the implications of our results within the broader context of healthy diets from sustainable food systems.

Methodology

Study design and dietary scenarios

We modelled the health impacts of current food consumption and the environmental impacts of its production in Argentina, and assessed the effects of potential dietary changes in the whole population under seven scenarios: one based on improved income and six based on healthier diets. All eight dietary scenarios were built taking into account the current population (40,370,737 people or 32,368,554 adult-male equivalents) (INDEC 2021) and present-day agricultural technologies and practices, as well as food losses and waste levels. Thus, the effects analyzed here correspond only to dietary changes, which are assumed to be homogenous across the population. Table 1 describes in detail the diet composition for all scenarios.

Table 1.

Diet composition for the eight modelled diets

| Food item | Unit | Baseline | II | NDG | EL | EL-ARG | EL-NRM | EL-LOV | EL-VEG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beef | g/day | 113.7 | 156.2 | 35.0 | 15.0 | 85.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Chicken | g/day | 68.6 | 76.4 | 24.0 | 30.0 | 28.6 | 57.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Pork | g/day | 5.5 | 8.9 | 35.0 | 15.0 | 28.6 | 57.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Lamb and mutton | g/day | 1.2 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Fish and seafood | g/day | 7.1 | 11.4 | 47.0 | 40.0 | 28.6 | 57.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Processed meats | g/day | 21.5 | 60.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other meats | g/day | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Milk | mL/day | 135.7 | 146.3 | 600.0 | 300.0 | 350.0 | 350.0 | 400.0 | 0.0 |

| Other dairy products | g/day | 53.8 | 75.6 | 35.0 | 30.0 | 35.0 | 35.0 | 40.0 | 0.0 |

| Eggs | g/day | 14.9 | 19.1 | 32.0 | 30.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 55.0 | 0.0 |

| Refined grains | g/day | 231.4 | 255.3 | 120.0 | 58.8 | 80.8 | 68.8 | 50.0 | 60.5 |

| Whole grains | g/day | 9.6 | 10.9 | 147.0 | 270.0 | 170.0 | 170.0 | 260.0 | 300.0 |

| Legumes and pulses | g/day | 5.1 | 6.5 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 150.0 | 150.0 |

| Nuts and seeds | g/day | 0.6 | 1.0 | 7.5 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 40.0 | 30.0 | 55.0 |

| Fruits | g/day | 67.0 | 102.4 | 375.0 | 250.0 | 250.0 | 250.0 | 250.0 | 250.0 |

| Vegetables | g/day | 144.3 | 183.4 | 500.0 | 350.0 | 250.0 | 350.0 | 350.0 | 350.0 |

| Starchy vegetables | g/day | 95.0 | 101.7 | 67.0 | 50.0 | 100.0 | 70.0 | 50.0 | 100.0 |

| Oil and fats (plants) | mL/day | 24.6 | 33.8 | 30.0 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 55.0 |

| Oil and fats (animal) | g/day | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Stimulants | g/day | 19.7 | 30.9 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| Sweet. candies and sugar | g/day | 39.8 | 57.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Snacks | g/day | 1.6 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Spices | g/day | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Salt | g/day | 3.9 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Dressings | g/day | 7.8 | 12.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other foods | g/day | 2.2 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Sugar-free drinks | mL/day | 91.1 | 158.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Sugary drinks | mL/day | 192.5 | 265.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Alcoholic beverages | mL/day | 42.2 | 72.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

II: improved income scenario (diet of the upper middle group)

NDG National Dietary Guidelines scenario, EL EAT-Lancet scenario, EL-ARG EAT-Lancet scenario adapted to Argentine culture, EL-NRM same as EAT-ARG but replacing ruminants with chicken, pork, and fish, EL-LOV EAT-Lancet lacto-ovo vegetarian scenario, EL-VEG EAT-Lancet vegan scenario

*Includes bottled water, ice, and sparkling water

The baseline scenario represents the current dietary pattern in Argentina. It was obtained by combining food purchase data from the 2017/2018 National Survey of Household Income and Expenditure (NSHIE) (INDEC 2021) for an individual adult-male from the average income group (Weisell and Dop 2012), with coefficients of food waste at the household level (Menchú and Mendez 2007). A total of 376 food and beverage items were considered and classified into 29 food groups to facilitate the analysis (see Table S1 in Supplementary Material for more details). To explore the impact of a desirable and expected increase in household income, we developed the improved income (II) scenario, which represents the food consumption pattern of an adult male of the upper middle-income group (obtained following the methodology described for the baseline scenario; see Table S1 in Supplementary Material). Further details can be found in Arrieta et al. (2021a).

Additionally, six scenarios based on healthier diets were also considered, one based on the National Dietary Guidelines (Ministry of Health 2016) and the other five based on the dietary recommendations from the EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems, with some local adaptations (Willett et al. 2019). Since 44% of the Argentine population do not exercise regularly (NRFS 2018) and because increasing physical activity is a global public health goal (WHO 2019a), the six healthy diets were designed to match the energetic requirement of an adult-male with a moderate physical activity level of 2500 kcal/day (WHO 2020a). The National Dietary Guidelines (NDG) scenario represents the adoption of the diet recommended by the official national organisations. The EAT-Lancet (EL) scenario was represented by the EAT-Lancet diet. The EL-ARG scenario is an adaptation of the EL diet to the beef-loving Argentine population, including 1 large beef-based meal (600 g) and 3 other meat-based meals (200 g per meal) per week. The NRM scenario (non-ruminant meat) represents the same diet as EL-ARG but replacing ruminants with chicken, pork, and fish in equal proportions (400 g/week of each one). The EL-LOV scenario represents a lacto-ovo vegetarian diet, with no meat of any type and extra legumes, whole grains, dairy products, and eggs. Finally, the EL-VEG scenario represents a vegan or strict vegetarian diet, replacing all animal products with legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds.

Health dimension evaluation

The health dimension was assessed by estimating nutrient adequacy and dietary quality. Nutrient adequacy was calculated for each diet considering its nutrient content and comparing their values to international guidelines. First, we obtained 25 nutrients for the 376 food items and beverages using the Food Composition Database from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA 2021). Second, we estimated the weighted mean of nutrient density for the 29 food groups by considering the current diet (Table 2 in Supplementary Material). Third, we paired the consumption of each food group with its nutrient density in each modelled diet. We then compared the calculated nutrient content of the scenarios with the recommendations of the Institute of Medicine for an adult-male (USDA 2017).

Table 2.

Daily nutrient supply for the eight modelled diets

| Nutrient | Unit | Recommendation | Baseline | II | NDG | EL | EL-ARG | EL-NRM | EL-LOV | EL-VEG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | kcal | 2200 | 2177 | 2843 | 2500 | 2500 | 2500 | 2500 | 2500 | 2500 |

| Protein | g | 56 | 86 | 112 | 113 | 101 | 107 | 109 | 94 | 80 |

| Total fat | % kcal | 20–35 | 38% | 41% | 33% | 36% | 40% | 40% | 35% | 35% |

| Saturated fatty acids | % kcal | < 10% | 11% | 12% | 9% | 8% | 10% | 9% | 8% | 4% |

| Monounsaturated fatty acids | % kcal | > 15% | 18% | 20% | 16% | 21% | 22% | 23% | 20% | 23% |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acids | % kcal | > 5% | 4.50% | 4.60% | 4.10% | 5.10% | 4.90% | 5.50% | 5.00% | 5.70% |

| Carbohydrate | % kcal | 40–55 | 46% | 43% | 52% | 50% | 45% | 45% | 53% | 56% |

| Fiber | g | 30.8 | 19.91 | 23.7 | 47.52 | 49 | 42.49 | 44.12 | 53.15 | 59.37 |

| Calcium | mg | 1000 | 710 | 861 | 1318 | 957 | 962 | 988 | 1094 | 565 |

| Iron | mg | 8 | 14 | 18 | 24 | 28 | 24 | 24 | 29 | 31 |

| Magnesium | mg | 420 | 288 | 350 | 521 | 561 | 501 | 532 | 564 | 613 |

| Phosphorus | mg | 700 | 1284 | 1623 | 2035 | 1847 | 1828 | 1898 | 1853 | 1535 |

| Potassium | mg | 4.7 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 5 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.0 |

| Sodium | mg | < 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.2 |

| Zinc | mg | 11 | 12 | 17 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 13 |

| Vitamin A | μg | 900 | 614 | 780 | 1323 | 920 | 875 | 938 | 986 | 708 |

| Thiamin | mg | 1.2 | 1.6 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.4 |

| Riboflavin | mg | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 2 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 2 |

| Niacin | mg | 16 | 15 | 17 | 25 | 30 | 23 | 24 | 30 | 34 |

| Vitamin B-6 | mg | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| Folate | μg | 400 | 383 | 452 | 757 | 707 | 662 | 666 | 845 | 858 |

| Vitamin B-12 | mg | 2.4 | 6.1 | 8.1 | 5.7 | 3 | 6 | 3.7 | 2.5 | 0 |

| Vitamin C | μg | 90 | 63 | 80 | 190 | 134 | 128 | 138 | 139 | 147 |

| Vitamin D | μg | 5 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 9.4 | 5.4 | 5.8 | 6.5 | 6.1 | 0.0 |

| Vitamin E | μg | 15 | 16 | 21 | 22 | 28 | 27 | 28 | 28 | 32 |

| Vitamin K | μg | 120 | 92 | 128 | 249 | 194 | 153 | 194 | 200 | 208 |

Values in bold denote inadequate levels (i.e., either lower than minimum recommendations or higher than maximum recommendations). II: improved income scenario (diet of the upper middle group)

NDG National Dietary Guidelines scenario, EL EAT-Lancet scenario, EL-ARG EAT-Lancet scenario adapted to Argentine culture, EL-NRM same as EAT-ARG but replacing ruminants with chicken, pork, and fish, EL-LOV EAT-Lancet lacto-ovo vegetarian scenario, EL-VEG EAT-Lancet vegan scenario. The red line represents the current diet (baseline scenario)

Dietary quality was estimated using the Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 (AHEI-2010). The AHEI-2010 is a diet quality index validated as a strong predictor of major chronic disease risk, mortality, and biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial function (Sotos-Prieto et al. 2017; Morze et al. 2020). The AHEI has been shown to be useful for analyzing the diet quality in different geographical contexts (Morze et al. 2020), while the Argentine population follows a western dietary pattern very similar to the one found in the United States, where the AHEI was originally developed (Wang et al. 2019). The AHEI-2010 encompasses key components of healthy eating, including higher consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, whole grains, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), long-chain n-3 PUFAs (mainly from seafood), and lower consumption of red/processed meat, sugar-sweetened beverages (including fruit juice), trans fats, alcohol, and sodium. We excluded alcohol from the analysis because of a lack of reliable data, since its consumption is usually underestimated in household expenditure surveys (WHO 2019b). The 10-component AHEI-2010 used here ranged from 0 (nonadherence) to 100 (perfect adherence), and each of the components was scored from 0 to 10.

Environmental dimension evaluation

To analyze the environmental impact of the dietary scenarios, we developed a national food-system model that connects food consumption and production at the national scale. Then, production estimates were paired with a set of six environmental impact categories related to GHG emissions, total land occupation, cropland demand, fossil energy use, freshwater consumption, and the emissions of eutrophying pollutants. We considered 18 food groups that represent 93% of the food consumed in the current diet (Table S3 in Supplementary Material).

To estimate food production and its environmental impact, food consumption was converted into food demand by considering food losses and waste at the processing, retailing, and household levels (Gustavsson et al. 2011; Poore and Nemecek 2018). Then, food demand was combined with the environmental impacts obtained from previous studies that conducted life cycle assessments at the farm gate (Clark and Tilman 2017; Pernollet et al. 2017). Environmental impacts were assumed to occur within the country, since most calories consumed are fulfilled by the national food system (see section “Acknowledgements and limitations” for more details). Due to the large effect of animal products in the environmental footprint of diets (Godfray et al. 2018) and the distinct livestock production systems found in Argentina, we used our own estimations for GHG emissions, total land occupation, cropland demand, and fossil energy use for beef, chicken, pork, milk, and egg (Arrieta and González 2019a, b; Arrieta et al. 2020, Arrieta et al. unpublished results). The emissions of eutrophying pollutants from livestock products were estimated using GHG emissions as a proxy, due to the strong and significant correlation between these impact categories (Röös et al. 2013). Local data on freshwater consumption for all food groups were obtained from Mekonnen and Hoekstra (2011, 2012). Table S4 in Supplementary Material shows the food losses and waste coefficients used, and the indicators of environmental impact considered for the 18 food groups analyzed.

Economic dimension evaluation

Food prices and household income are major determinants of food consumption patterns and dietary quality (Darmon and Drewnowski 2015; Carolan 2018). Thus, we estimated the daily monetary cost of diets to explore the economic opportunities and limitations associated with dietary transitions in Argentina. The daily expenditure in 376 food items and beverages for an average adult-male was obtained from the 2017/2018 National Survey of Household Income and Expenditure (INDEC 2021). Then, food items were classified into 29 food and beverage groups. After considering the non-edible fraction of food (Menchú and Mendez 2007), prices by food and beverage groups were expressed in 2018 USD/100 g or 2018 USD/100 ml. Therefore, the cost of each food and beverage group (Table S5 in Supplementary Material) does not represent a specific food item but rather the average of the main preferences in Argentina. Finally, the food composition of diets was matched with food prices to obtain the daily monetary expenditure of each modelled diet.

Acknowledgements and limitations

We acknowledge three main shortcomings in our study that have, arguably, little impact on our conclusions: (i) the role of food imports, (ii) post-farm environmental impacts, and (iii) levels of uncertainty.

First, the proportion of the apparent domestic food consumption that is supplied through imports is very minimal. In more detail, according to the Food Balance Sheets of the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), only 2% of the kilocalories consumed domestically come from imports (FAOSTAT 2021). Therefore, our analysis did not consider imported food and projected scenarios, assuming that changes in the demand of the different food items could be fulfilled by domestic production. Food imports include some fish and seafood items, coffee, cocoa, and some fruits such as pineapple, bananas, and plantains; see more details in Table S6 in Supplementary Material.

Second, as the environmental impacts were estimated considering only the on-farm production stage, the overall environmental impacts of diets may be underestimated. Although post-farm activities, such as industrial processing, packaging, transport, storage and household preparation, and waste, could in some cases represent an important share of the environmental impacts of food systems, food production accounts for a considerably larger fraction (Poore and Nemecek 2018). However, whether and how alternative diets may affect post-farm inputs and impacts still remains an open question requiring additional research (Poore and Nemecek 2018). Similar to the previous limitation, although the overall effects to our results might be low, the actual extent might be vary between different diets depending on the level of processing for each diet (i.e., cooking methods) (Arrieta and González 2019a, b).

Third, although it would have been interesting to explore the statistical significance for the differences between diets, we could not comply, because we only have one estimation for each impact per diet (and no estimation of internal variability). Undoubtedly, the estimation of each parameter used to calculate all the impacts has some error associated; however, most of them are unknown to us, and thus, we can neither provide a measure of uncertainty. Still, as all diets were evaluated using the same parameters, all estimations would share the same uncertainty; thus, we are confident that the relative differences among diets reported here are representative of the real relative differences.

Results

Health dimension

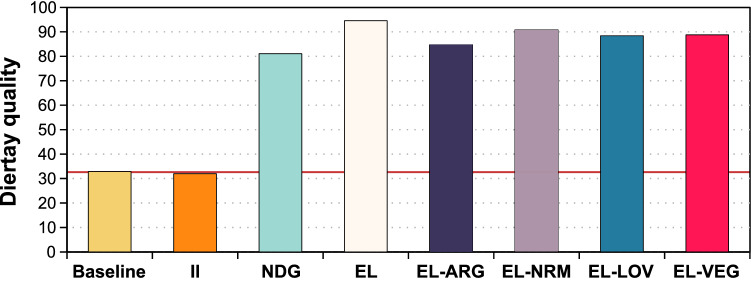

The current Argentine diet is characterized by a high consumption of red and processed meat, refined grains, starchy vegetables, ultra-processed foods, and sugar-sweetened beverages, as well as low intake of fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, fish, nuts, and seeds. This dietary pattern leads to an inadequate intake of several minerals and vitamins that are only found in plants (Fig. 1). This explains the very-low-quality index of the current dietary pattern (AHEI score of 33 over 100); see Table S7 in Supplementary Material for details).

Fig. 1.

Dietary quality of the eight modelled diets as measured with the Alternate Healthy Eating Index. II: improved income scenario (diet of the upper middle group). NDG National Dietary Guidelines scenario, EL EAT-Lancet scenario, EL-ARG EAT-Lancet scenario adapted to Argentine culture, EL-NRM same as EAT-ARG but replacing ruminants with chicken, pork, and fish, EL-LOV EAT-Lancet lacto-ovo vegetarian scenario, EL-VEG EAT-Lancet vegan scenario. The red line represents the current diet (baseline scenario)

Under the improved income (II) scenario, the overall dietary quality index is similar to the baseline scenario (AHEI score of 32/100). In this case, the benefits related to an increase in fruit and vegetable consumption were counterbalanced with a higher intake of red and processed meats and sugar-sweetened beverages. As a result, nutrient availability is improved, but not to the extent necessary to meet the recommendations for most of them (Table 2).

For all six healthy diet scenarios, nutrient adequacy increased for almost all nutrients due to the higher consumption of healthy foods and the decreased intake of unhealthy foods. This resulted in a much higher dietary quality (AHEI score of 81–95 over 100), see Fig. 1 and Table S7 in Supplementary Material. Calcium intake in the EL, EL-ARG, and EL-NRM scenarios is just below the recommended level, while in the EL-VEG scenario, the intake is half of the recommended level (Table 2). This, in addition to a low intake of vitamin D, could have detrimental effects for bone health. Calcium intake could be improved by adding green vegetables, beans, dairy products, or fortified foods to the diet. Furthermore, bone health would benefit from an increase in exercise and the vitamin D found in all alternative healthy scenarios. EL-VEG also lacks vitamin B-12 which is only found in animal products, but can be easily obtained from fortified foods and supplements.

Environmental dimension

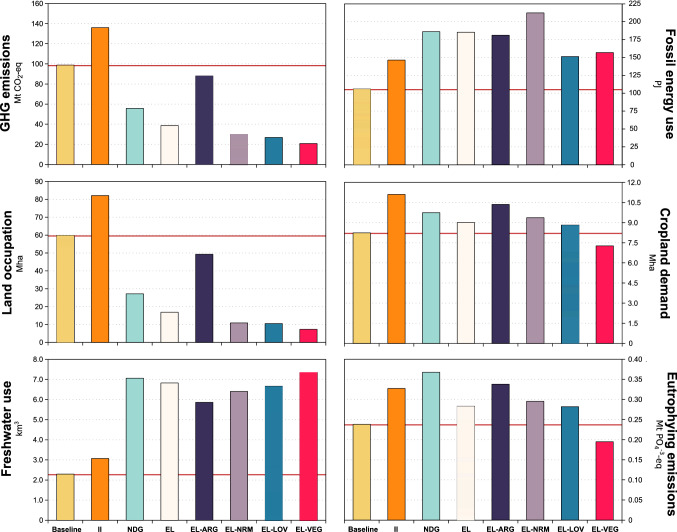

To supply the domestic demand of food in 2018, Argentina required 59.8 Mha of land (including 8.24 Mha of croplands), 106 PJ of fossil energy, and 2.29 km3 of fresh water, and emitted 98.9 Mt CO2-eq and 0.238 Mt PO4-eq (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

National-level environmental impacts associated with food production for the eight modelled diets. II: improved income scenario (diet of the upper middle group). NDG National Dietary Guidelines scenario, EL EAT-Lancet scenario, EL-ARG EAT-Lancet scenario adapted to the Argentine culture, EL-NRM same as EAT-ARG but replacing ruminants with chicken, pork, and fish, EL-LOV EAT-Lancet lacto-ovo vegetarian scenario, EL-VEG EAT-Lancet vegan scenario. Red line represents the current diet (baseline scenario)

Beef was the food item with the largest effect on the levels of all studied environmental impacts, except for freshwater consumption, which was dominated by vegetables and fruits (23% and 21%, respectively). Beef production accounted for 89% of total land occupation (53.2 Mha), covering 43 Mha of native pastures, 7.3 Mha of sown pastures, and 2.8 Mha of croplands (34% of total cropland demand). Similarly, 85% of GHG emissions originated from beef cattle, followed by dairy cattle (4%). Regarding fossil energy use, beef production accounted for 21% of the total, followed by oil crops (17%) and chicken (15%). Finally, beef, dairy and chicken operations accounted for 65% of the emissions of eutrophying pollutants (see Table S9 in Supplementary Material).

Under the improved income scenario (II), the environmental impact increased by 33–38% for all impact categories in comparison to the current diet, which was driven by an increase of the demand of animal source foods, fruits, and vegetables: 136 Mt CO2-eq, 82.1 Mha of land, 11.1 Mha of cropland, 146 PJ of fossil energy, 3.07 km3 of freshwater, and 0.327 Mt PO4-eq.

Changes towards healthier diets have the potential to reduce some environmental impacts while increasing others but, overall, more plant-based diets exhibits the lowest total environmental impacts; see Fig. 2 and Table S8 in Supplementary Material. Compared with the baseline scenario, the adoption of healthy diets would reduce GHG emissions by between 11 to 79% and land occupation by 18–88%, mainly due to decreases in the consumption of animal source foods (particularly beef). However, cropland demand would increase by 18% and 26% under the NDG and EL-ARG scenarios (with more animal source foods), but only 7–13% in EL-NR, EL and EL-LOV. Only under the EL-VEG scenario cropland demand decreases (by 12%), but in this case, fossil energy use and freshwater consumption would increase by 43–101% and 156–220%, respectively, due to the increase in consumption of healthy foods such as fruits, vegetables, fish, milk, and nuts. The emission of eutrophying pollutant increased by 18–54% in all healthy diet scenarios, except in EL-VEG where they decreased by 18%.

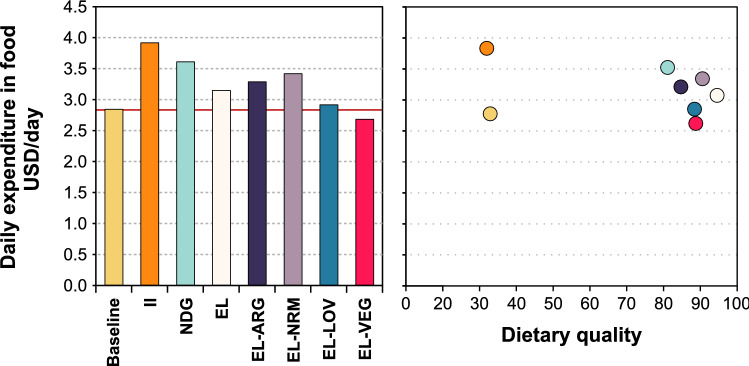

Economic dimension

The daily food expenditure of the current diet was 2.78 USD/day (or 2.24 USD/day excluding sweets, snacks, and beverages incl. sugar-sweetened, alcoholic, and non-alcoholic). This main expenses included beef (26%), refined grains (19%), dairy products (13%), and chicken (10%). Under the II scenario, food expenditure rose to 3.07 USD/day (3.83 USD/day including sweets, snacks, and beverages) because of the higher intake of beef, processed meats, and dairy products.

In general, healthy diets were more expensive than the current diet, but the difference varied greatly across scenarios (Fig. 3). In particular, NDG was the most expensive diet (3.54 USD/day), followed by EL-NRM (3.35 USD/day), EL-ARG (3.21 USD/day), and EL (3.09 USD/day). The plant-based diets were the least-expensive, with EL-LOV costing almost the same as the baseline scenario diet (2.86 USD/day), and EL-VEG actually being cheaper than the baseline diet (2.63 USD/day). Fruits, vegetables, and whole grains represent an important share of the cost in all healthy diets, while milk and fish are consistently prominent in the cost of the diet scenarios containing animal-sourced foods. Legumes and nuts are among the top five food groups in terms of expenditure only in the lacto-ovo vegetarian and vegan diets (cf. Table S10 in Supplementary Material).

Fig. 3.

Daily expenditure for the eight modelled diets. II: improved income scenario (diet of the upper middle group). NDG National Dietary Guidelines scenario, EL EAT-Lancet scenario, EL-ARG EAT-Lancet scenario adapted to Argentine culture, EL-NRM same as EAT-ARG but replacing ruminants with chicken, pork and fish, EL-LOV EAT-Lancet lacto-ovo vegetarian scenario, EL-VEG EAT-Lancet vegan scenario. Red line represents the current diet (baseline scenario)

Discussion

Synthesis of findings

Similar to many other developing countries, Argentina is facing an unprecedented health and environmental crisis that requires a more holistic and coordinated approach than the traditional sector-focused attempts (FAO 2018a). What is needed is a framework that recognizes the totality of food systems and considers all its elements, as well as the main interlinked activities and feedbacks. This would help to understand how to minimize trade-offs, improve resource-use efficiency, and internalize social and environmental impacts related to food production and consumption (Bortolleti and Lomax 2018).

We found that the current food consumption pattern in Argentina is unhealthy and environmentally unsustainable, and that the general adoption of diets associated with the more affluent segments of society would make the situation even worse. The higher consumption of food sourced from animals in high-income households found in this study has already been reported for Argentina (Zapata et al. 2016; Arrieta et al., 2021a). In fact, an increase in income has been consistently associated with a higher consumption of animal protein, as well as a reduction in the preference for plant protein in other low- and middle-income countries (Komarek et al. 2021). Thus, any policy oriented to reduce poverty through increased household income should also include education, incentives, and nudging towards dietary changes that avoid rebound effects for the benefit of both people and nature (Lartey et al. 2016).

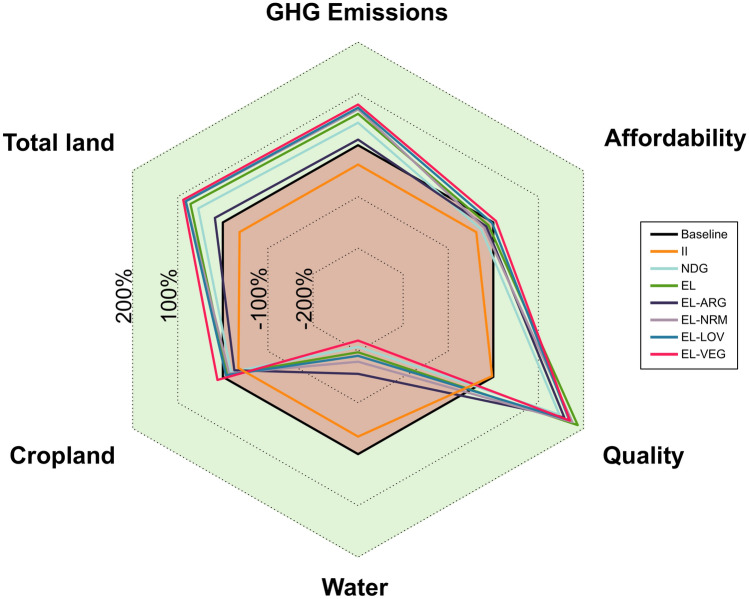

Furthermore, our results show that changes towards healthier diets offer multiple benefits. However, as Fig. 4 shows, there are multiple environmental and economic trade-offs that must be taken into account (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO 2020a, b). For instance, while healthy diets would require less land to produce food than the current diet, they would demand more freshwater (although a deeper water footprint analysis might be necessary) (Vanham and Mekonnen 2021). Furthermore, most healthy diets cost more than the current one and, considering that people can afford to spend more money on food, diverting household income towards healthier diets could have a negative impact on other dimensions.

Fig. 4.

Changes for the health, environmental, and economic dimensions of the alternative diets, relative to the current diet (baseline diet, black line). Positive values (green area) indicate improvements (i.e., higher benefits or lower impacts) and negative values (red area) indicate worsening (i.e., lower benefits or higher impacts). Fossil energy use and emissions of eutrophying pollutants were not included. II: improved income scenario (diet of the upper middle group). NDG National Dietary Guidelines scenario, EL EAT-Lancet scenario, EL-ARG EAT-Lancet scenario adapted to the Argentine culture, EL-NRM same as EAT-ARG but replacing ruminants with chicken, pork, and fish, EL-LOV EAT-Lancet lacto-ovo vegetarian scenario, EL-VEG EAT-Lancet vegan scenario

Finally, the increased demand of fish, seafood, and plant products in the healthy scenarios cannot be satisfied by the current national food system (Arrieta et al. 2021b). This could be solved by increasing imports and lowering food self-sufficiency, or by increasing national production, which could result in increasing the pressure on the natural environment. Given Argentina's agricultural history, the most logical path would be to increase the domestic food production to meet the domestic demand. For fish, it would imply increasing catches from fisheries (with possible negative impacts on marine biodiversity and environment) (Grip and Blomqvist 2020) or increase aquaculture production that is still rather undeveloped in the country compared to other countries (FAO 2018b). For other commodities such as fruits, nuts, and vegetables, it might require greater land and water investments (more details in the section “Environmental implications”). In the following sections, we expand the discussion on the health, environmental, economic, and political implications of such dietary transitions.

Health implications

NCDs kill 41 million people each year, which is equivalent to 71% of all deaths globally, with most of them occurring in low- and middle-income countries (Murray et al. 2020). This fraction increases to 80% in Argentina, representing 279,801 deaths in 2019 (Murray et al. 2020). The high prevalence of NCDs in Argentina is attributed mainly to the unhealthy lifestyle of the population, such as physical inactivity, tobacco use, harmful consumption of alcohol, and poor-quality diets (NRFS 2018). In addition, demographic and socioeconomic factors such as urbanization and poverty further complicate the prevalence and distribution of NCDs (Pou et al. 2017). United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 3.4 (SDG 3.4) seeks to reduce premature mortality from NCDs by a third by 2030 (Bennett et al. 2018). However, the current rate of change is too slow to achieve such a target in most countries, including Argentina (Bennett et al. 2020). Since poor-quality diets are recognized as one of the five most important risk factors for NCDs’ development (Afshin et al. 2019), healthy diets are more important than ever (Godlee 2020). For instance, a recent modelling study found that improved diets could prevent nearly 24% of total premature deaths worldwide (28% in Argentina), putting dietary changes into the centre of NCD prevention strategies (Wang et al. 2019). Promoting healthy eating becomes even more important in Argentina where only one-third of the population recognizes following an unhealthy diet, and only 6% meet the optimal level of intake for fruits and vegetables (NRFS 2018). In addition, two food items that are highly desired and consumed by the Argentine population (red meat and processed meat) represent the most important dietary risk factors for morbidity (GBD 2021).

As the COVID-19 outbreak exposes the fragility of health systems globally and the poor health status of the general population (WHO 2020b; Chang et al. 2020), particularly in relation with NCDs (Clark et al. 2020; CDC 2020; Popkin et al. 2020); new insights on current diets and desirable dietary transitions become urgent (IATF 2020; Horton 2020). Nevertheless, healthy diets must be promoted together with physical activity and discouraging tobacco and alcohol use to increase well-being and to reduce NCDs prevalence as much as possible (Li et al. 2020).

Environmental implications

As for other developing countries with an agriculture-oriented economy, deforestation and land-use change are among the most important environmental issues in Argentina (MESD 2020). We have shown that healthy diets have the potential to relieve the pressure on natural and semi-natural ecosystems by reducing land occupation up to sixfold without substantially increasing the cropland area needed. This would be achieved mainly by reducing beef consumption, and could help prevent the further loss of terrestrial biodiversity and ecosystem services, restore degraded land, and enable better landscape management (Leclère et al. 2020; Díaz et al. 2020; Benton et al. 2021).

In addition, regardless of dietary changes, other strategies would be needed to increase the sustainability of food production and consumption. For instance, technical and technological improvements in food production, as well as reductions in food losses and waste, are important pathways to enhance food systems sustainability (Springmann et al. 2018; Willett et al. 2019). However, no single measure is enough to stay within all planetary boundaries simultaneously, and thus, a synergistic combination of measures will be needed to mitigate the projected increases in environmental pressures (Alexander et al. 2019; Gerten et al. 2020).

It is worth mentioning that the realization of the potential environmental benefits described in this study is contingent with the degree on which the reduction in beef domestic demand results in a reduction in production (with the associated environmental benefits) versus an increase in exports which would negate possible environmental benefits but would favor the economy through its effects on labor demand and trade balance (Arrieta et al. 2021b). The discussion around which of these options should be encouraged or discouraged on behalf of the national interest is not likely to be easy, as it touches on questions of cultural identity and the role that beef and cattle ranching plays in it. Furthermore, reduced beef consumption in a country as associated with beef as Argentina could provide momentum to the global movement calling for reduced meat consumption. At the same time, an increase in beef exports would increase the influence of global demand and the importing countries’ preferences and regulations on the Argentine beef industry, which could alter both production levels and systems (i.e., how much and how is produced), affecting the overall environmental impact of Argentine beef. For instance, China currently is the main importer of Argentine beef, but its national government has recently formulated policies to cut meat consumption by half by 2030 to reduce pollution and combat obesity (Lei and Shimokawa 2020).

It is worth noting that despite beef having one of the largest environmental impacts among the studied food items, under certain production systems, cattle can have some positive effects on grassland ecosystems, at least relatively to extensive cropping (Herrero et al. 2015). Grasslands are one of the most threatened ecosystems worldwide (Díaz et al. 2019), but their grazing can help maintain them to provide valuable ecosystem services such as habitat for biodiversity, water regulation, and carbon sequestration (Bengtsson et al. 2019). In this sense, Argentina has suitable grazing lands and an historical tradition of beef production, with recent studies suggesting that by improving management practices, the Argentine beef cattle sector can produce more meat without increasing its environmental impact (Pacín and Oesterheld, 2015; González Fischer and Bilenca 2020). Nevertheless, the displacement of cattle ranching from the Pampas towards less productive rangelands has in the past increased the pressure over native forests and the dependence on grains to increase the energy intake of the cattle (Viglizzo et al. 2011). Currently more than half of the land devoted to beef production is located in the northern regions of the country (Arrieta et al. 2020; Fernández et al. 2020), including the Dry Chaco, which is a global deforestation hotspot due to the conversion of forest into pastures and annual crops (e.g., soybean, maize) for animal feed (Baumann et al. 2017). Although not considered in this analysis, the conversion of native forests to pasture land could significantly increase direct and indirect cattle-related GHG emissions from this region (De Vries et al. 2015). In this sense, even when good management practices have the potential of increasing carbon sequestration in grazing lands, it is still not clear how much sequestration is possible as it depends on the initial conditions, as well as the local environmental characteristics (Smith et al. 2020). Furthermore, despite some claims to the contrary (Viglizzo et al. 2019; 2020), it is unlikely that soil carbon sequestration would come even close to compensating for aboveground livestock emissions (Alvarez et al. 2020; Baldassini and Paruelo 2020). Thus, beef production presents important trade-offs that require more and better quality data, as well as multiple approaches to improve the understanding, assessments, and planning of appropriate interventions (Villarino et al. 2020; Sahlin et al. 2020).

Interestingly, the adoption of healthy diets poses environmental challenges that could be possibly transformed into opportunities. For instance, the higher demand for freshwater to produce fruits, vegetables, and nuts seems to be a major challenge (Sokolow et al. 2019; Tuomisto 2019). Despite having very good agro-ecological conditions for agricultural production, Argentina does not produce enough of these food items to fulfill domestic demand (Mason-D'Croz et al. 2019; Vanham et al. 2020; Arrieta et al. 2021b). Currently, a large fraction of the production of these food items occurs in irrigated oases, and while freshwater is abundant in some of them (e.g., Río Negro valley, San Rafael oasis), in others (e.g., Mendoza and San Juan oases), glacier melting and climate change present huge challenges for increasing the production of fruits and vegetables in the future (Schwank et al. 2014; Parajuli et al. 2019). Therefore, to satisfy healthier diets, the diversification of domestic production and the better distribution of crops across the country could be some alternative avenues that somewhat surprisingly have not received enough attention yet (Davis et al. 2017; Aguiar et al. 2020). Domestically, the production of fruits, vegetables, and nuts could be promoted around urban belts in the more humid areas of the country following agro-ecological production models. With properly managed community participation, this could not only save water but also reduce the competition between residential and extensive agricultural land uses, mainly because of pesticide use (particularly herbicides), in many suburban fringes of the country (Russo et al. 2014; Mac Loughlin et al., 2017; Goites et al. 2020).

Economic implications

Increasing the local availability of healthy food is an important step towards the adoption of healthy diets, but it is not enough on its own (Carolan 2018). Food choice is an extremely complex phenomenon (Leng et al. 2017), shaped by physiological and psychosocial drivers. In this sense, it is both a conscious and an unconscious process that is affected both by internal (e.g., taste preferences) and external factors (e.g., advertisement, social media). However, it is well established that food prices and household income are the most important determinants of food purchases (Darmon and Drewnowski 2015; Muhammad et al. 2017).

In this study, we found that in Argentina, healthy diets are more expensive than the current one, and that half of the population could not afford them, though this figure is probably higher after the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (CEPAL 2021).

Hirvonen et al. (2020) estimated that, at a global average cost of 2.84 USD/day, ~ 20% of people in the world could not afford the EAT-Lancet diet.

Many nutrition interventions in the developing world have focused on improving nutritional knowledge (Dewey and Adu-Afarwuah 2008). Such interventions could be life-saving for infants and young children that need only small quantities of each food, but could remain unaffordable if larger food volumes are needed for older children and adults. This suggests that achieving healthy diets for the entire population will likely require transfer programs and social protection, in addition to lower food prices and nutrition education programs that steer consumers towards healthier dietary choices (Bai et al. 2021). In this sense, by achieving nutrient adequacy with minimal costs (and similarly use low-cost approaches to housing and other basic needs) could alleviate poverty in a manner that is more relevant to policymakers’ development goals than conventional poverty interventions (Allen 2017).

Policy implications

Our results support the proposition that improving the quality of diets can help to reduce the health and economic burden of NCDs, and deliver benefits for the environment (Willett et al. 2019). Good nutrition is key for proper individual development and, as such, governments should not ignore the issue. This calls for the need of holistic and well-rounded policies, at the foundation of which lay Food Based Dietary Guidelines (Bechthold et al. 2018). Besides providing guidance for individuals on what to eat, these are intended to set out the official dietary “vision” for the country and related public policies. Thus, they should also incorporate economic and environmental considerations for a more holistic approach to sustainability (Gonzalez Fischer and Garnett 2016). We have shown that the adoption of the NDG would result in reduced GHG emissions and land occupation when compared with the baseline diet scenario, but less so than the other healthy diets (particularly compared to the plant-based ones). We have also shown that the NDG is the most expensive diet among the healthy diets. These results call for updating the NDG to reflect the latest nutritional evidence, focusing on NCDs prevention and including economic and environmental sustainability criteria to provide the best guidance according to the latest evidence (Springmann et al. 2020).

The great challenge of promoting dietary transitions to reduce NCDs could be tackled by implementing public policies that can complement and strengthen the ongoing strategies for reducing tobacco and alcohol consumption, together with other well understood health interventions for hypertension, diabetes, and cancer (Bennett et al. 2020). For instance, in the Argentine context, at the time of writing the present work, a bill is being intensely discussed in the National Congress regarding front-of-pack labeling for ultra-processed foods, as an important measure to help consumers avoid unhealthy food choices (Shangguan et al. 2019; Popkin et al. 2021). Another controversial nudging approach was recently taken by the Buenos Aires City Council, which declared of “environmental interest” the international Meatless Monday initiative. Other strategies, such as taxation and subsidies, have been suggested to be among the most promising policies for dietary improvement and NCDs’ prevention (Thow et al. 2018). Even modest dietary improvements could significantly reduce the burden of NCDs and a small price difference seems to be effective in decreasing the exposure to the dietary risk factors (Afshin et al. 2017b). However, a common argument against labeling and taxes for unhealthy foods (which was also used by the tobacco industry in the past) despite the fact that it will disproportionately affect the poorest. However, NCDs are a particularly important cause of death, suffering, and economic loss within this group (Bukhman et al. 2020).

Any measure oriented to improve the quality of diets would need to be coordinated in a way to avoid clashing with current initiatives that favor unhealthy diets such as the traditional meat-rich “Argentine plate”. For instance, since 1997, the Value-Added Tax on beef is nearly half of that of other meats (9.5% vs. 21%). Furthermore, in 2001, the national government established the Argentine Beef Promotion Institute to increase beef consumption (IPCVA; Law N° 25.507). Since 2014, Argentina has implemented a price-control policy to protect consumers against price distortion and inflation (see “Protected Prices Program”, https://www.argentina.gob.ar/precios-cuidados). This policy is based on a voluntary agreement between the government, producers, processors, distributors, supermarkets, and wholesalers, where the price of widely consumed products are standardized and controlled nationally. The specific products largely reflect the food basket of low-income households and the list includes 203 food items of which 101 are ultra-processed foods. Of the remaining 102 food items, 12 are alcoholic beverages (wine was declared the National Beverage in 2013), and 3 are beef products. Only 13 out of the 203 items included in the program are among those whose consumption should be encouraged to improve health: apples, onions, lettuce, pumpkin, 2 cornmeal products (“polenta”), canned chicken peas, and 13 milk products (5 types of fresh milk, 4 of long-life milk and 4 of powder milk). On the other hand, food programs and subsidies such as the “Feed card”, school canteens, and other initiatives developed within the “Argentina Against Hunger” Plan provide valuable opportunities to improve the dietary quality of low-income groups.

Because of the deep cultural roots associated with meat in general and beef in particular, we believe that the transition of the culinary culture in the country would be one of the most challenging aspects towards achieving a healthy and sustainable diet. However, young generations are increasingly leaning towards more plant-based diets and the consumer niche of meat substitutes is growing every year. Surprisingly, the first in-vitro meat tasting event in Latin America took place in Argentine after being produced by a local foodtech (AgroVerdad, 2021).

However, in the absence of incentives to choose healthy foods, it is unlikely that the general population will spontaneously improve the quality of its diet. An updated NDG with a holistic approach to food sustainability (including all components of the food system and all aspects of the food environment) and strong policy links across the multiple sectors involved in food production, processing, distribution, and consumption could help to integrate health, agricultural, and environmental policy and deliver broad sustainability benefits (Gonzalez Fischer and Garnett 2016; Fanzo et al. 2020; FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO 2020a, b).

Conclusions

The changes towards healthy and sustainable diets represent a major challenge in Argentina because of the poor quality of the current diet and the deep cultural roots associated with beef. Our modelling exercise shows that the health and environmental crisis currently unfolding in Argentina could be mitigated through the adoption of healthy diets that bringing benefits to both people and the environment. While replacing meat with plants (partially or totally) is logistically and culturally challenging, it offers multidimensional benefits.

Improving the Argentine diet would entail reducing the consumption of red and processed meats, ultra-processed foods, and sugar-sweetened and alcoholic beverages, and increasing the intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, fish, nuts, and seeds. Such transition towards healthy and sustainable diets may be interpreted as a homogenization with global diets and a loss of local culture and identity. However, international recommendations for healthy and sustainable diets simply provide a sense of direction, towards an ideal that every society needs to adapt to its own characteristics and circumstances. More awareness on the sustainability impacts of what we eat can be seen as an opportunity for the positive appraisal of local products and traditional food items, as well as the integration of novel combinations that draw inspiration from the multicultural nature of the country. In addition, reducing meat consumption should not necessarily imply the abandonment of traditional culinary practices, but a progressive modification of some of them, such as limiting the consumption of beef to special occasions (e.g., the weekend “asado” or roasted-meat party) and the inclusion of more plant foods in traditional preparations.

Remarkably, even with a population willing to adopt a healthy and sustainable diet, the national food system has significant limitations in catering for the necessary food items for everybody. Fortunately, the country's agro-ecological conditions provide great potential to meet this demand and contribute to the supply of healthy foods to domestic and overseas markets. In this sense, the alignment of agricultural production and environmental policies with those related to human diet and nutrition could have important synergistic benefits for enhancing sustainability. However, achieving these goals would require a more holistic and coordinated approach than the current sector-focused attempts. A framework that recognizes the totality of food systems (the “foodscape”) and considers all their inter-weaving elements is crucial to avoid sustainability trade-offs, improve resource-use efficiency (while minimizing rebound effects), and internalize health, environmental, and social impacts related to food production and consumption. In this sense, the NDG should be updated to reflect the latest nutritional evidence, focusing on NCDs’ prevention and including economic and environmental sustainability criteria to provide the best guidance according to the latest evidence.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the support of the National Scientific Research Council of Argentina (CONICET) for the Doctoral fellowship of E.M.A. and C.M.S., the Post-doctoral fellowship of S.A. and M.G., and the Researcher positions of R.J.F, A.R., A.L., and E.J.G. The editor and two anonymous reviewers provided valuable comments and suggestions that greatly improved the manuscript.

Footnotes

Handled by Alexandros Gasparatos, University of Tokyo, Japan.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estepet K, Murray CJL. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. New Engl J Med. 2017;377:13–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afshin A, Penalvo JL, Del Gobbo L, Silva J, Michaelson M, O'Flaherty M, Capewell S, Spiegelman D, Danaei G, Mozaffarian D. The prospective impact of food pricing on improving dietary consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0172277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, Cornaby L, Ferrara G, Salama JS, Mullany EC, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abebe Z, Afarideh M. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2019;393:1958–1972. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agroverdad (2021) Cultured meat: Argentine laboratory held a first tasting in Buenos Aires (in Spanish). Available at: https://agroverdad.com.ar/2021/07/carne-cultivada-laboratorio-argentino-realizo-en-buenos-aires-una-primera-degustacion Accessed July 29, 2021

- Aguiar S, Texeira M, Garibaldi LA, Jobbágy EG. Global changes in crop diversity: trade rather than production enriches supply. Glob Food Sec. 2020;26:100385. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander P, Brown C, Arneth A, Finnigan J, Rounsevell MD. Human appropriation of land for food: the role of diet. Glob Environ Chan. 2016;41:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander P, Reddy A, Brown C, Henry RC, Rounsevell MD. Transforming agricultural land use through marginal gains in the food system. Glob Environ Chan. 2019;57:101932. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RC. Absolute poverty: When necessity displaces desire. Am Econ Rev. 2017;107:3690–3721. doi: 10.1257/aer.20161080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez R, Berhongaray G, Gimenez A. Are grassland soils of the pampas sequestering carbon? Sci Total Environ. 2020;763:142978. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arneth A, Barbosa H, Benton T, Calvin K, Calvo E, Connors S, Driouech F (2019) IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. Summary for Policy Makers. Geneva, Switzerland Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

- Arrieta EM, González AD. Impact of current, National Dietary Guidelines and alternative diets on greenhouse gas emissions in Argentina. Food Policy. 2018;79:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta EM, González AD. Energy and carbon footprints of chicken and pork from intensive production systems in Argentina. Sci Total Environ. 2019;673:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta EM, González AD. Energy and carbon footprints of food: investigating the effect of cooking. Sustai Prod Consum. 2019;19:44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta EM, Cabrol DA, Cuchietti A, González AD. Biomass consumption and environmental footprints of beef cattle production in Argentina. Agric Syst. 2020;185:102944. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta EM, Geri M, Coquet JB, Scavuzzo CM, Zapata ME, González AD. Quality and environmental footprints of diets by socio-economic status in Argentina. Sci Tot Environ. 2021;801:149686. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta EM, González AD, Fernández RJ. Dietas saludables y sustentables, ¿Son posibles en la Argentina? Ecol Aust. 2021;31:148–169. doi: 10.25260/EA.21.31.1.0.1096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Alemu R, Block SA, Headey D, Masters WA. Cost and affordability of nutritious diets at retail prices: evidence from 177 countries. Food Policy. 2021;99:101983. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldassini P, Paruelo JM. Deforestation and current management practices reduce soil organic carbon in the semi-arid Chaco Argentina. Agric Syst. 2020;178:102749. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2019.102749. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batis C, Mazariegos M, Martorell R, Gil A, Rivera JA. Malnutrition in all its forms by wealth, education and ethnicity in Latin America: who are more affected? Public Health Nutr. 2020;23:s1–2. doi: 10.1017/S136898001900466X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann M, Gasparri I, Piquer-Rodríguez M, Gavier Pizarro G, Griffiths P, Hostert P, Kuemmerle T. Carbon emissions from agricultural expansion and intensification in the Chaco. Glob Chan Biol. 2017;23:1902–1916. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechthold A, Boeing H, Tetens I, Schwingshackl L, Nöthlings U. Perspective: food-based dietary guidelines in Europe - scientific concepts, current status, and perspectives. Adv Nutr. 2018;9:544–560. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmy033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens P, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Bosker T, Rodrigues JF, De Koning A, Tukker A. Evaluating the environmental impacts of dietary recommendations. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:13412–13417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1711889114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson J, Bullock JM, Egoh B, Everson C, Everson T, O'Connor T, O'Farrell PJ, Smith HG, Lindborg R. Grasslands—more important for ecosystem services than you might think. Ecosphere. 2019;10:e02582. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.2582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett JE, Stevens GA, Mathers CD, Bonita R, Rehm J, Kruk ME, et al. NCD countdown 2030: worldwide trends in non-communicable disease mortality and progress towards sustainable development goal target 3.4. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1072–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31992-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett JE, Kontis V, Mathers CD, Guillot M, Rehm J, Ezzati M. NCD countdown 2030: pathways to achieving sustainable development goal target 3.4. Lancet. 2020;396:918–934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31761-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton TG, Bieg C, Harwatt H, Pudasaini R, Wellesley L. Food system impacts on biodiversity loss. London: Chatham House; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bodirsky BL, Dietrich JP, Martinelli E, Stenstad A, Pradhan P, Gabrysch S, Mishra A, Weindl I, Le Mouël C, Rolinski S, Baumstark L. The ongoing nutrition transition thwarts long-term targets for food security, public health and environmental protection. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75213-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolleti M, Lomax J. Collaborative framework for food systems transformation. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bukhman G, Mocumbi AO, Atun R, Becker AE, Bhutta Z, Binagwaho A, Clinton C, Coates MM, Dain K, Ezzati M, Gottlieb G. The lancet NCDI poverty commission: bridging a gap in universal health coverage for the poorest billion. Lancet. 2020;396:991–1044. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31907-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell BM, Beare DJ, Bennett EM, Hall-Spencer JM, Ingram JS, Jaramillo F, et al. Agriculture production as a major driver of the earth system exceeding planetary boundaries. Ecol Soc. 2017;22(4):8. doi: 10.5751/ES-09595-220408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carolan M. The real cost of cheap food. London: Routledge; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- CDC . Evidence used to update the list of underlying medical conditions that increase a person’s risk of severe illness from COVID-19. Washington D.C: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CEPAL . Latin American Social Panorama 2020 (in Spanish) Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. Chile: Santiago de Chile; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chang AY, Cullen MR, Harrington RA, Barry M. The impact of novel coronavirus COVID-19 on noncommunicable disease patients and health systems: a review. J Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1111/joim.13184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark M, Tilman D. Comparative analysis of environmental impacts of agricultural production systems, agricultural input efficiency, and food choice. Environ Res Lett. 2017;12:064016. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa6cd5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark M, Hill J, Tilman D. The diet, health, and environment trilemma. Ann Rev Environ Resour. 2018;43:109–134. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-102017-025957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MA, Springmann M, Hill J, Tilman D. Multiple health and environmental impacts of foods. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:23357–23362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1906908116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A, Jit M, Warren-Gash C, Guthrie B, Wang HH, Mercer SW, Sanderson C, McKee M, Troeger C, Ong KL, Checchi F. Global, regional, and national estimates of the population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions in 2020: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1003–e1017. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30264-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordell D, Neset TSS, Prior T. The phosphorus mass balance: identifying ‘hotspots’ in the food system as a roadmap to phosphorus security. Curr Opin Biotech. 2012;23:839–845. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crippa M, Solazzo E, Guizzardi D, Monforti-Ferrario F, Tubiello FN, Leip A. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nature Food. 2021;2:198–209. doi: 10.1038/s43016-021-00225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: a systematic review and analysis. Nutr Rev. 2015;73:643–660. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuv027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KF, Rulli MC, Seveso A, D’Odorico P. Increased food production and reduced water use through optimized crop distribution. Nat Geosci. 2017;10:919–924. doi: 10.1038/s41561-017-0004-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries MD, Van Middelaar CE, De Boer IJM. Comparing environmental impacts of beef production systems: a review of life cycle assessments. Livest Sci. 2015;178:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2015.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey KG, Adu-Afarwuah S. Systematic review of the efficacy and effectiveness of complementary feeding interventions in developing countries. Matern Child Nutr. 2008;4:24–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00124.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz S, Zafra-Calvo N, Purvis A, Verburg PH, Obura D, Leadley P, Chaplin-Kramer R, De Meester L, Dulloo E, Martín-López B, Shaw MR. Set ambitious goals for biodiversity and sustainability. Science. 2020;370:411–413. doi: 10.1126/science.abe1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz SM, Settele J, Brondízio E, Ngo H, Guèze M, Agard J, Chan K (2019) The global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services: Summary for policymakers. Bonn, Germany. Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)

- Fanzo J, Hawkes C, Udomkesmalee E, Afshin A, Allemandi L, Assery O, Baker P, Battersby J, Bhutta Z, Chen K, Corvalan C. Global nutrition report: shining a light to spur action on nutrition. Washington D.C: International Food Policy Research Institute; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fanzo J, Covic N, Dobermann A, Henson S, Herrero M, Pingali P, Staal S. A research vision for food systems in the 2020s: defying the status quo. Glob Food Sec. 2020;26:100397. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanzo J, Bellows AL, Spiker ML, Thorne-Lyman AL, Bloem MW. The importance of food systems and the environment for nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;113:7–16. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO . Sustainable food systems: concept and framework. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- FAO (2018b) National Aquaculture Sector Overview: Argentina. Food and Agriculture Organization. Rome, Italy. Available at https://www.fao.org/fishery/countrysector/naso_argentina/en Accessed July 29, 2021

- FAOSTAT (2021) Statistical databases. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available at http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/ Accessed July 29, 2021

- Fernández PD, Kuemmerle T, Baumann M, Grau HR, Nasca JA, Radrizzani A, Gasparri NI. Understanding the distribution of cattle production systems in the South American Chaco. J Land Use Sci. 2020;15:52–68. doi: 10.1080/1747423X.2020.1720843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- GBD (2021). GBD Compare. Global Burden of Disease Study. Available at: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ Accessed July 29, 2021

- Gerten D, Heck V, Jägermeyr J, Bodirsky BL, Fetzer I, Jalava M, Kummu M, Lucht W, Rockström J, Schaphoff S, Schellnhuber HJ. Feeding ten billion people is possible within four terrestrial planetary boundaries. Nat Sust. 2020;3:200–208. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0465-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Godfray HC, Aveyard P, Garnett T, Hall JW, Key TJ, Lorimer J, Pierrehumbert RT, Scarborough P, Springmann M, Jebb SA. Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science. 2018;361:eaam5324. doi: 10.1126/science.aam5324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godlee F. COVID-19: What we eat matters all the more now. BMJ. 2020;370:m2840. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2840. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goites E, Tito GM, Nugent P, Patrouilleau MM, Vitale Gutierrez JA, Perez MA, Giobellina BL, Cardozo F, Hernandez Toso F, Dalmasso C. (2020) Espacios agrícolas periurbanos: oportunidades y desafíos para la planificación y gestión territorial en Argentina. Ediciones INTA

- Gonzalez Fischer C, Bilenca D. Can we produce more beef without increasing its environmental impact? Argentina as a case study. Persp Ecol Conserv. 2020;18:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez Fischer C, Garnett T. Plates, pyramids, planet. Oxford: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and University of Oxford; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grip K, Blomqvist S. Marine nature conservation and conflicts with fisheries. Ambio. 2020;49:1328–1340. doi: 10.1007/s13280-019-01279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson J, Cederberg C, Sonesson U, Van Otterdijk R, Meybeck A. Global food losses and food waste. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer MA, Westhoek H, Ingram J, van Berkum S, Özay L (2016) Food systems and natural resources. United Nations Environmental Programme

- Halpern BS, Cottrell RS, Blanchard JL, Bouwman L, Froehlich HE, Gephart JA, Jacobsen NS, Kuempel CD, McIntyre PB, Metian M, Moran DD. Putting all foods on the same table: achieving sustainable food systems requires full accounting. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:18152–18156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1913308116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero M, Wirsenius S, Henderson B, Rigolot C, Thornton P, Havlík P, de Boer I, Gerber PJ. Livestock and the environment: What have we learned in the last decade? Ann Rev Environ Res. 2015;40:177–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-031113-093503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen K, Bai Y, Headey D, Masters WA. Affordability of the EAT–Lancet reference diet: a global analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e59–e66. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30447-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra AY, Wiedmann TO. Humanity’s unsustainable environmental footprint. Science. 2014;344:1114–1117. doi: 10.1126/science.1248365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton R. Offline: COVID-19 is not a pandemic. Lancet. 2020;396:874. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32000-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IATF . Joint statement on noncommunicable diseases and COVID-19 Inter-American task force on noncommunicable diseases. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- INDEC (2021) Household expenditure (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos. Available at: https://www.indec.gob.ar/indec/web/Nivel4-Tema-4-45-151 Accessed July 29, 2021

- Jobbágy EG, Aguiar S, Garibaldi LA, Piñeiro G. Impronta ambiental de la agricultura de granos en Argentina: Revisando desafíos propios y ajenos. Ciencia Hoy. 2021;29:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Komarek AM, Dunston S, Enahoro D, Godfray HCJ, Herrero M, Mason-D'Croz D, Rich KM, Scarborough P, Springmann M, Sulser TB, Wiebe K. Income, consumer preferences, and the future of livestock-derived food demand. Glob Environ Chan. 2021;70:102343. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalskys I, Rigotti A, Koletzko B, Fisberg M, Gómez G, Herrera-Cuenca M, Cortés Sanabria LY, Yépez García MC, Pareja RG, Zimberg IZ, Del Arco A. Latin American consumption of major food groups: results from the ELANS study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0225101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartey A, Hemrich G, Amoroso L, Remans R, Grace D, Albert JL, Gonzalez Fischer C, Garnett T. Influencing food environments for healthy diets. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lassaletta L, Billen G, Garnier J, Bouwman L, Velazquez E, Gerber JS. Nitrogen use in the global food system: past trends and future trajectories of agronomic performance, pollution, trade, and dietary demand. Environ Res Lett. 2016;11:095007. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/11/9/095007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leclère D, Obersteiner M, Barrett M, Butchart SH, Chaudhary A, De Palma A, DeClerck FA, Di Marco M, Doelman JC, Dürauer M, Freeman R. Bending the curve of terrestrial biodiversity needs an integrated strategy. Nature. 2020;585:551–556. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2705-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei L, Shimokawa S. Promoting dietary guidelines and environmental sustainability in China. China Econ Rev. 2020;59:101087. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2017.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leng G, Adan RA, Belot M, Brunstrom JM, de Graaf K, Dickson SL, Hare T, Maier S, Menzies J, Preissl H, Reisch LA. The determinants of food choice. Proc Nutr Soc. 2017;76:316–327. doi: 10.1017/S002966511600286X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Schoufour J, Wang DD, Dhana K, Pan A, Liu X, Song M, Liu G, Shin HJ, Sun Q, Al-Shaar L. Healthy lifestyle and life expectancy free of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;368:l6669. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mac Loughlin TM, Peluso L, Marino DJ. Pesticide impact study in the peri-urban horticultural area of Gran La Plata, Argentina. Sci Total Environ. 2017;598:572–580. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason-D'Croz D, Bogard JR, Sulser TB, Cenacchi N, Dunston S, Herrero M, Wiebe K. Gaps between fruit and vegetable production, demand, and recommended consumption at global and national levels: an integrated modelling study. Lancet Planetary Health. 2019;3:e318–e329. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30095-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen MM, Hoekstra AY. The green, blue and grey water footprint of crops and derived crop products. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci Discuss. 2011;15:1577–1600. doi: 10.5194/hess-15-1577-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen MM, Hoekstra AY. A global assessment of the water footprint of farm animal products. Ecosyst. 2012;15:401–415. doi: 10.1007/s10021-011-9517-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menchú M, Mendez H. Central American food composition table (in Spanish) Guatemala: Instituto de Nutrición de Centro América y Panamá; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- MESD . State of the environment report 2019 (in Spanish) Buenos Aires: Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health . National dietary guidelines for Argentina (Spanish) Buenos Aires: Ministry of Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]