Abstract

Art has been an integral part of the field of medicine, and has served, since the beginning of the time, in its development. This literature review explores the deep relationship between art and medicine through history, and how they are inextricably linked. Even during this current era and evolution, art has found its way in the different aspects of medicine from academic literature, digital health, and medical curriculum. Moreover, the increasing prevalence of mental health disorders, especially in those with chronic diseases, has resulted in art being used as a tool to alleviate symptoms and offer emotional relief. With the emergence of a new era of medicine, art is expected to play a major role in its foundation.

Keywords: Art, Cartoon, Poetry, Academia, Health, Rheumatology

Introduction

Art is an expression of the human condition. It is a reflection of our memories and experiences, which are more often than not rooted in the world around us. Since the beginning of modern civilization, artists have captured the human body and either purposefully or subconsciously, made studies about the form, movement, and disease that affects it. Art is closely intertwined with every aspect of life and has found its way into academia in the form of medical illustrations, including anatomical diagrams, infographics, videos and therapeutic methodologies. Art can be expressed in several forms like drawing, painting, sculptures, cartoons, animations, tapestry, poetry, literature, cinema, music, theatre and so on.

Tracing the etymology of the word humanities, it becomes evident that it encompasses an amalgamation of artistic, ethical, moral, philosophical, medical, sociological, political and psychological aspects. This furthermore reinforces the co-dependence of the arts and life sciences.

This literature review explores the deep relationship between art and medicine in general, and rheumatology in particular, through history, and how they are inextricably linked. For this article, an extensive review of PubMed and Scopus was done using the search terms Art, Rheumatology and Medicine. [1] Through this opinion piece, we hope to familiarize readers with the oft-forgotten role of art in life in general, and the possibilities with respect to the practice of medicine. The utilization of art in various forms, and situations—such as by the patients for art therapy, by the physicians for their release, and for entertainment in academia, in general, may offer a unique opportunity to bridge the healthcare professional and patient community.

Art and medicine through history

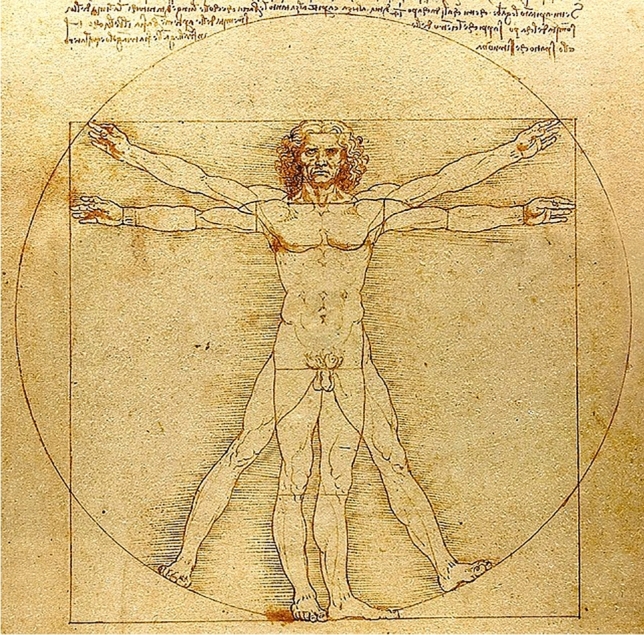

Art, medicine, and academia have been inextricably linked throughout history. Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (Fig. 1) [2] symbolizes the confluence of art, architecture, mathematics, religion, and philosophy of the Renaissance period. Drawing inspiration from Vitruvius, a Roman architect, da Vinci put a man in the context of the universe to solve the irreconcilable areas of a circle and a square. It introduced the beauty of diagrams, especially with respect to anatomy, highlighting the harmonic proportions in the human body. If geometry is the language the universe is written in, then the Vitruvian Man seems to say we can exist within all its elements. Mankind can fill whatever shape he pleases, both geometrically and philosophically.

Fig. 1.

“The Vitruvian Man” by Leonardo da Vinci, circa 1492. Sourced from Wikimedia Commons under the public domain license from the Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice. Materials used: Pen, ink, watercolor and metal point on paper

To accurately illustrate the anatomy and proportions of the body, artists would study human models for endless hours by observation. They would even exhume and dissect corpses to gain further insight into this aspect. Today, dissection forms a core learning module for all medical students for much of the same goals.

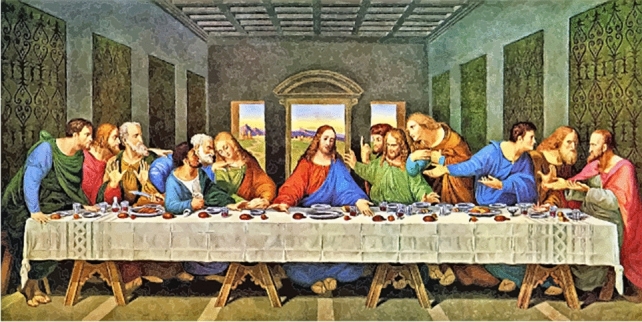

Historically, art began as imitations of the artists’ surroundings, drawing inspiration from their everyday sightings and experiences. The diseases and deformities prevalent at the time were also captured by them. In this context, The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci portrays one of the diners with a hand deformity in a depiction of arthritic illnesses in that era (Fig. 2) [3].

Fig. 2.

“The Last Supper” by Leonardo da Vinci, circa 1492. Sourced from Creative Commons under the public domain license. Located in the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria Delle Grazie, Milan, Italy. Materials used: Fresco painting by mixing pigments into wet plaster to create a permanent bond

Apart from establishing the occurrence of these diseases over the centuries, these art forms may also provide a bird’s eye view into the natural history of arthritic illnesses, such as the classic deformities seen in the rheumatoid hand [4]. Archaeological digs in Tennessee revealed the first traces of arthritis in 4500 BC. Cravings in stone dating way back to the 200 A.D. depict deformities seen in osteoarthritis of the hand, while later images depict rheumatoid, gout [5], and giant cell arteritis. The first formal descriptions of rheumatoid were much delayed, the first one is by a French surgeon, Dr. Augustine Jacob Landré- Beauvais in 1800, and the term rheumatoid arthritis was coined as later as 1859 by Sir Alfred Garrod. A near epidemic of hand deformities described in French Renaissance paintings of Jean and François Clouet has been much debated as possible ‘beautifying variations’; a stylistic approach in paintings of this period [6]. The real challenge, therefore, may be distinguishing substance and style [7].

Art enabled the discovery of rheumatic disease characteristics prior to them being defined as pathological entities. Rheumatologists incorporated and utilized art as a method of diagnosis and medical education long before modern medicine [8]. Hence, as discussed, several pieces of art have been identified from the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the Baroque and the Post-Impressionist periods regarding rheumatic diseases [9]. Moreover, several pieces by artists such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Antoni Gaudi, Raoul Dufy, Frida Kahlo, and Paul Klee, were influenced by the chronic pain associated with rheumatic diseases, with this being apparent in the technique used and the overall content of their work [9]. Manifest hypermobility of the hand has also been found in various ancient paintings, including “Saint Cyriaque” by Mathias Grünewald (1450-1528), Frankfurt, and “The wounded man” by Gaspare Traversi, Venice (1732-1769). As keen observers of nature, artists observed and reported changed way before the physicians did, paving the way for art of the past being an adjunct to the field of paleopathology [10].

Thus, art provides us with a window into the natural history of various diseases [6]. Looking at the art of a particular period reflects the then-current standing of society in all realms, including the health of the people, prevalent diseases at the time and modes of therapy implemented. Furthermore, studying the art of rheumatology provides an influential resource to understand the progression of these diseases throughout time, enabling rheumatologists today to trace the history of several conditions [11].

Art by the diseased

Art has also been a medium of catharsis for mental agony and distress. This statement could not be truer than within the field of medicine and humanities. The term ‘catharsis’ itself was first coined by Aristotle and was further propounded by Freud in his theory of catharsis in “Selected papers on Hysteria” to mean- a purging through vicarious experience. [12] So naturally, the artists that themselves suffered from conditions and continued to create their works, often reflect their illness in their themes and technique and may serve as a medium for the physicians’ emotional release of pain from continued observation of human suffering. In this context, Paul Klee, a famous artist who developed systemic sclerosis, had a remarkable turnaround in the output and character of art forms created over the course of his disease and life. Whilst the diagnosis culminated into an immediate reduction of artwork, there is a sharp change in character from intricate, small drawings to rugged, coarse, larger compositions possibly influenced by reduced effort tolerance or disability in holding pens. Later, a deluge of over a thousand dull paintings in dark colors and disfigured faces resembling a scleroderma-like appearance depicting suffering and reflections of his introspections into the illness and self-image surfaced in the last year before his demise [13].

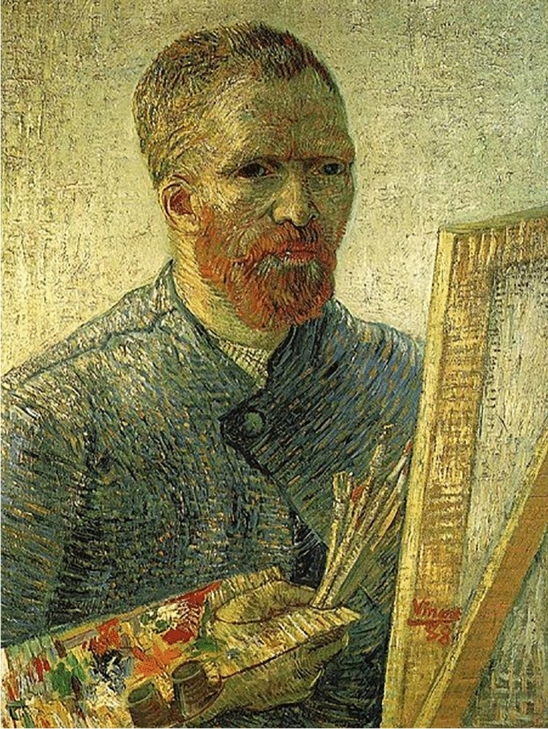

Another example is the famous post-Impressionist Vincent Van Gogh, who was afflicted with mental illness in his early adulthood, argued to be bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. The darker color schemes and harsh strokes during episodes of mania become clear on analysis, as opposed to smoother, calmer-themed paintings in periods of remission (Fig. 3) [14]. These findings coincide with his letters, in which he describes his episodes [15]. Michelangelo, the great Renaissance artist, is often included on lists of celebrated gout patients. Ankylosing spondylitis affected Cosimo de Medici and the poet Scarron, while the disability of Columbus is thought to be more compatible with Reiter’s syndrome [16].

Fig. 3.

“Self Portrait as an Artist” by Vincent van Gogh, early 1888. Sourced from Wikimedia Commons under the public domain license from the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam Netherlands. Materials used: Oil on canvas in the Neo-impressionist style

In recent times as well, patients with rheumatoid, fibromyalgia and other arthritic illnesses have created art to express pain and life struggles. Support from other patients on social media helps them cope with the illness by reminding them that they are not alone on this journey. An emerging patient movement of support communities online may have much to offer to fellows suffering from chronic diseases, by the portrayal of suffering and catharsis using art forms [17]. These artworks take several forms, ranging from visual arts to prose and poetry (Table 1).

Table 1.

Artistic depiction of rheumatic illnesses in history [40]

| Timeline | Artist | Artwork | Diseases depicted |

|---|---|---|---|

| 200–1200 |

Mexico Jalisco, Mexico |

Clay sculpture Sculpture |

Heberden’s node Osteomyelitis/fracture/Tumor |

| 1400–1500 |

Dieric Bouts, Denmark Jan van Eyck, Belgium Hieronymus Bosch, Netherlands Quinten Metsys, Belgium |

‘The Last Supper’, ‘Mater Dolorosa’ and ‘The Ascension of Maria’ ‘Adoration of the Lamb’ ‘John IV, Duke of Brabant’ ‘The Virgin with the Canon’ ‘The Procession of the Cripples’ ‘A Grotesque Old Woman’ |

Camptodactyly Heberden’s node Swan-neck, Boutonnière deformities Temporal Arteritis with PMR Pott’s disease, SpA, Hyperostosis vertebralis, Post-infectious osteomyelitis Osteitis deformans |

| 1600–1800 |

Caravaggio, Italy Peter Paul Rubens, Belgium (Himself suffered from RA) Claes Cornelisz Moeyaert, Denmark Murillo, Spain Vincent van Gogh, Netherlands |

‘The Sleeping Cupid’ ‘Saint Mathew’, ‘The Drunken Sleeping Satyr’, ‘Suzanna and the Elders’, ‘Portrait of Marie de Medici’, ‘Saint Augustine between Christ and the Virgin’, and ‘The Holy Family with St Anne’ ‘The Three Graces’ Portraits of priest Siebrands Sixties ‘Archangel Raphael and Bishop Francisco Domonte’ ‘La Berceuse (Augustine Roulin)’ |

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Hand Arthritis Benign Familial Hypermobility Syndrome, Trendelenburg sign Rheumatoid Arthritis Scleroderma Hand Arthritis |

Art serves as a powerful form of expression that enables people, and in this instance, patients suffering from any given disorder, to put their feelings and their experience into a tangible form. This in turn enables them to not only gain insight into their condition during the process but also to connect with others that share similar experiences. These result in building confidence and positive support communities to encourage oneself, inspire others and even possibly convert into a plausible means of livelihood. Such results were remarkably seen in the study conducted in patients with Bipolar Affective disorder [18]. Patients with chronic illnesses, palliative care patients and those suffering from intractable pains have benefitted hugely from the implementation of daily pain journals and discussion clubs [19]. These foster an atmosphere of empathy and shake the taboo shrouding these topics. That being said, Art could be could also be an addiction, imperative obsession, compulsion, sophisticated vocation or religious coercion. Its practice within the permitted boundaries of medicine and academic communication can bring out the best of practice.

Medicine as both—a science and art

Just like two sides of a coin, medicine is both an art and a science. The age-old question poses a thought-provoking discussion. Opposing schools of thought exist on the matter. Is medicine an art? According to some, medicine is an art based on science [20]. Medicine cannot be without the inherent art of caring, comforting and acting upon our core human values. At the same time, medicine is undeniably now a technically sophisticated field and falls under the umbrella term of Applied Sciences—throwing weight to the question- Is medicine a science? Yet another interesting perspective is the Art of Medicine—which highlights the art of being a physician, patient welfare, patient autonomy and justice for the community at large. It is imperative that we, as the future of the medical field, preserve the dying art of medicine to uphold the morals our great physicians strive to imbibe in future generations. Contemporary medicine is largely based on schemes, standardized algorithms, evidence, and has therefore not much art in practice. The lost art of medicine may be revived in light of this opinion piece, which discusses the important role of creative activity in medicine, in myriad forms.

On another note, many writers and researchers have argued that art and literature should be instilled in the medical curriculum for the reason that art helps doctors and medical practitioners to understand experiences, illness and human values and that art and literature may additionally play a therapeutic role.

Artforms in medical literature

While an artist’s depiction of illnesses is subject to their perceptions and perspectives, the use of Art and visual content in academic literature can be challenging. Used correctly this visual presentation can provide an efficient demonstration of its purpose.

Poems and prose have been important forms of literary art in history. Poems have been used to depict pain and suffering by the patients or their kin, or for entertainment and humor. Poems are also considered in academic literature, mainly poems which are related to the medical experience, whether from the point of view of a healthcare worker or patient, or simply an observer. It is a great way to color a patient’s perspective while facing a disease or give an artist’s words to express a medical observation [22–24].

Cartoons are a different form of art sometimes featured in academic literature and considered a valuable visual aid in medical and health education. They hold the potential to portray a range of social, pragmatic, and scientific issues with a tinge of humor. The pandemic saw a surge in medical cartoons on the internet with various memes and pictures afloat to let out emotional overreactions among healthcare workers and the public.

Medical humor is no exception and has found its place in academic journals on occasion [21]. Comics are well known to be one of the best and well-suited way for visualizing and explaining complex processes and ideas, and in the time of the 2020 pandemic, a lot of authors and journalists has used the different categories of this art form, from instructional comics, personal stories, and therapeutic comics to introduce the novel virus to the general public by showing how it’s transmitted and what people can do to protect themselves. As a way of dealing with stress anxiety and isolation a lot of people have also opted for the use of comics-making via online drawing sessions and the publication of reflective activities. Comics are also helping to document and narrate the variety of lived experiences during the coronavirus pandemic, including the absurdity of the social lockdown and social distancing [25, 26].

Besides the pandemic, cartoons and other graphic materials have often been used to improve doctor-patient communication in rheumatology, and even at times to educate the medical fraternity about gray areas in medical ethics [27]. A 1986 study assessed the communicational value of several art forms, including cartoons and photographs, presented as educational booklets concerning osteoarthritis. The patient’s comprehension of the information provided in these booklets was evaluated using a multiple-choice questionnaire. The findings were indicative of the enhanced communication associated with pictures in booklets, with cartoons being the most effective art form in this respect [28]. In young children in pediatric rheumatology set up, especially, utilizing art as a form of education about their condition not only increases comprehension but also enhances the rapport with the rheumatologist, building up a level of trust. Overloading patients with lots of medical terms and information about rheumatic diseases can be overwhelming; hence, presenting this information in an easy-to-understand artform may improve their psychological reaction to their diagnosis.

Art in scholarly journals

While the artwork was traditionally considered the prime domain of newsletters in the medical community, in the last decades, many journals have started to allow the publication of these art forms. The JAMA Network, which is a monthly open-access medical journal published by the American medical association has created a specific rubric called “The arts and Medicine” specifically for this type of publication. Various leading medical journals promote poetry and other art forms, usually as single-author publications, with minimal specifications on the length and scope [7]. Among rheumatology, Rheumatology International and the Indian Journal of Rheumatology have been publishing artwork relevant to Rheumatic Diseases and others such as Rheumatology Oxford and Mediterranean J Rheumatology have published reviews on the subject [28].

With the increasing numbers of publications and the accelerated speed of scientific discoveries, the journals have opted for a more stringent peer review to prevent any sort of unethical methods such as blatant copying, plagiarism, or the misuse of confidential information. However, how stringent a peer-review should be allowed for art forms is subject to debate and may vary from one art form to another. Thus, it is imperative to know the various forms of art in academic literature and to follow certain guidelines and recommendations to ensure a good presentation of it.

Art for therapeutics

Since the early 1980s, the assemblage of design, environments and arts in healthcare environments have been proven to reduce anxiety and depression. Artistic features in the healthcare environment have also been found to affect staff and patients, and improvements in visual and acoustic conditions may reduce risks of errors in some care settings. Numbered Research has suggested that naturalistic environments are uplifting for recovery and rehabilitation, while on the other hand, noisy and unhealthy environments may contribute to increased stress, anxiety, and depression.

Over the decades, various therapeutic modalities revolve around the principles of art [29]. Medical art therapy is defined as the use of art expression and imagery with individuals who are physically or mentally ill, experiencing trauma to the body, or who are undergoing aggressive medical treatment such as surgery or chemotherapy. Visual art therapy has now become an established form of treatment in mental illnesses, as a self-response tool to alleviate anxiety and panic attacks, as a part of rehabilitation and special education. Various resources can be used such as drawing, painting, sculpture, collage, writing, photography, textiles and digital art and videography with the core principle of expression and communication of the more non-verbal aspects of the human condition. In regard to applications in rheumatology, visual art therapy has been proposed as an equally effective and feasible intervention, when compared with conventional physiotherapy, for the enhancement of hand functions in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [14]. This, in turn, enhances a patient’s self-perception and overall quality of life.

A recent study assessed the efficacy of visual art therapy as a creative therapeutic procedure to enhance hand functions in 17 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The control group in this study received conventional physiotherapy, focusing on single-plane movements and strengthening exercises targeted at improving function and preventing deformities. The treatment group, on the other hand, received an art-based intervention with bimanual projects, including origami, paper quilling, clay modeling, and oil painting. The study found that a similar improvement in hand functions and both two-point and three-point pinch strength was apparent in both groups [30].

Music, being the auditory expression of art, is widely used as a form of therapy in diverse areas of health—in physical rehabilitation, hospice care, and special education for children and adolescents, and as an adjunctive modality in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. It is broadly characterized as the use of music in a therapeutic context to enhance a person’s mental health and societal wellbeing [31]. It involves listening to live or recorded music, singing along to familiar songs, playing instruments (which could be as simple as hand percussion) and music-assisted relaxation techniques such as Progressive Muscle Relaxation [32]. Music for rheumatism has been described in a vast amount of historical literature. Music therapy, today, is used to alleviate the symptoms and chronic pain associated with rheumatic diseases; however, historical literature describes the use of music therapy for patients with “gout (podagra)” or “joint pain”, presentations indicative of rheumatic diseases. The historical perceptions and comprehension of music therapy differed greatly, with the middle Ages and the Baroque period determining music to be a useful tool in the fight against pain, whereas, in the Romantic period, music was deemed a casual therapy. In modern medicine, music is recognized as an active therapy in the care and management of patients with rheumatism, with the wide success of this intervention in rehabilitation and palliative therapy being accepted [33].

Oftentimes a combination of music and visual art therapy is recommended, in accordance with the capacity and effect on the patient. This form of therapy has the inherent advantage of being able to be individualized to each patient’s needs while being cost-effective as well [34]. Art has also proven to be an effective mode of therapy for rheumatic diseases, both singularly and collaboratively with traditional methods, as seen in patients with Marfan’s Syndrome [35]. Additionally, it has been shown to bring about significant improvements in the pediatric demographic, for instance in children affected with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis [36]. These promising results have established the role of art therapy within the field, and its expanding use in other rheumatic afflictions.

Art for mental health

Rheumatic diseases are often chronic and encompass several emotional dimensions as well. The emotional burden of long-term treatment and medical surveillance significantly hinders a patient’s mental health and must be considered when medical care is considered [37]. Rheumatoid arthritis patients have been shown to be more prone to presenting with anxiety, depression and cognitive impairments when compared to their healthy peers [38]. It is not only the burden that these diseases present to a patient’s mental health that must be taken into consideration, but also the knock-on effect that this may have on their responsiveness to treatment and the exacerbation of their symptoms as a result. Several therapeutics that are administered in rheumatology may offer some relief for a patient’s anxiety and depression; however, these only improve symptoms to a certain extent and do not offer a complete cure [36]. Hence, other appropriate and feasible approaches must be employed to monitor mental wellbeing and quality of life in rheumatology patients to optimize care [39].

Art interventions, including music engagement, visual arts therapy, movement-based creative expression, and expressive writing, have been widely used to improve health outcomes in those with mental health disorders. The current literature supports the use of art and the engagement with creative activities not only to contribute to the reduction of stress and depression in patients but also to serve as a tool to alleviate the global burden of chronic disease [37]. Psychologists, in recent years, have assessed how art may be implemented to aid in healing emotional injuries, develop a capacity for self-reflection, offer symptom alleviation, increase understanding of both oneself and others, and alter a patient’s behaviors and thinking patterns. Art represents a holistic approach to medicine, especially in those with chronic diseases, including rheumatic diseases. A recent literature review recommended that clinical arts interventions and participatory art activities be more prevalently incorporated and made more widely available in both health and social settings to enhance mental health wellbeing [40].

In conclusion, Art had and continues to have a major role in all aspects of the medical field, ranging from delivering complex medical ideas in a comprehensible and accessible manner to the population at large, to therapeutics and rehabilitation. Various art forms are deeply entwined with medicine in general, and rheumatology in particular. Further investigation, exploration and implementation of art forms may offer another pillar of strength for the diligent practice of medicine (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Original artwork by Kamakshi Bansal. This piece depicts an amalgamation of symptoms seen in various rheumatological diseases. The features representing the symptoms have been hatched out by the artist to make them stand out. On the face of the figurine, one can visualize malar rash seen in SLE, Bluish black discoloration of ear cartilage as seen in Ochronosis and the Heliotrope rash of Dermatomyositis. In the hand, the ulnar deviation of fingers in RA, Dactylitis and shortening of fingers in Psoriatic Arthritis can be seen. One can also see a literal take on the Bamboo spine seen in Ankylosing Spondylitis on the left side of the painting

Author contributions

SV, LG and KB prepared the first draft. All authors reviewed the final version and offered critical intellectual inputs. All authors agree with the submitted version of the manuscript, take responsibility for the content of the entire manuscript, and affirm that any queries related to any aspect of the same are appropriately managed.

Funding

This study was not funded.

Availability of data and material

All data pertaining to the study is included in the manuscript and as supplementary material.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest relevant to the manuscript.

Ethical approval information

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Swapna Vijayan and Kamakshi Bansal have contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Swapna Vijayan, Email: swapnavjyn@gmail.com.

Kamakshi Bansal, Email: kamakshi.ucms@gmail.com.

Ashish Goel, Email: ashgoe@gmail.com.

Souhail Ouardouz, Email: souhail.oua@gmail.com.

Arvind Nune, Email: arvind.nune@nhs.net.

Latika Gupta, Email: drlatikagupta@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Blackmore H, et al. Writing a narrative biomedical review: considerations for authors, peer reviewers, and editors. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31:1409. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-1999-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Vitruvian Man restored Leonardo Da Vinci. Openclipart (2021) https://openclipart.org/detail/327614/the-last-supper-restored-leonardo-da-vinci. Accessed 22 Aug 2021

- 3.da Vinci L (1495) The last supper at the Louvre. Available under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan, Italy

- 4.Albury WR, Weisz GM. Three Saints with Deformed extremities in an Italian Renaissance altarpiece. Rheumatol Int. 2016;37(3):465–468. doi: 10.1007/s00296-016-3599-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manolios N. Arthritis in the hands of saints. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41(9):1705–1706. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-04786-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weisz GM, Albury WR, Matucci-Cerinic M, Lazzeri D. ‘Epidemic’ of Hand deformities in the French Renaissance paintings of Jean and François Clouet. QJM. 2016;109(9):633–635. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcw067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothschild B. Re: style versus substance in artistic depiction. Rheumatology. 2005;44(11):1464–1465. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Checa A. Valentin dancing at the Moulin rouge: a very good depiction of joint hypermobility by Toulouse-lautrec. Rheumatol Int. 2012;33(10):2675–2676. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinojosa-Azaola A, Alcocer-Varela J. Art and rheumatology: the artist and the rheumatologist's perspective. Rheumatology. 2014;53(10):1725–1731. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.J Dequeker Benign familial hypermotility syndrome and trendelenburg sign in a painting “The Three graces” by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640). Ann Rheum Dis. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11502619/. Accessed 12 Jan 2022 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Ashrafian H. Differential diagnosis of a Wrist mass on the Delphic Sybil of the Sistine chapel ceiling (1508–1512) by Michelangelo (1475–1564) Rheumatol Int. 2017;38(2):311–312. doi: 10.1007/s00296-017-3869-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheff TJ, Bushnell DD. A theory of catharsis. J Res Pers. 1984;18(2):238–264. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(84)90032-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatzidionysiou K (2019) Rheumatic disease and artistic creativity. Mediterr J Rheumatol. https://www.mjrheum.org/850/newsid792/181/showfulltext792/1. Accessed 19 Aug 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Une vie DE Vincent van Gogh par l'image. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Une_vie_de_Vincent_van_Gogh_par_l%27image. Accessed 19 Aug 2021

- 15.Blumer D (2002) Paris. Am J Psychiatry

- 16.Appelboom T The past: a gallery of arthritics. Clin Rheumatol. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF02032095. Accessed 18 Aug 2021 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Walker J (2019) Art for arthritis: a new approach. Arthritis Rheumatol. 71. https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/art-for-arthritis-a-new-approach/. Accessed 9 Aug 2021

- 18.Palupi GRP, Rahmanto SW, dan Lestari S. Art as a catharsis medium for people with bipolar disorder and synesthesia. Jurnal Ilmiah Psikologi. 2020;5(2):175–194. doi: 10.23917/indigenous.v5i2.11229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kearney R. Narrating pain: the power of catharsis. Paragraph. 2007;30(1):51–66. doi: 10.3366/prg.2007.0013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldman L, Schafer AI. Goldman’s Cecil medicine. Elsevier; 2012. Approach to medicine, the patient, and the medical profession: medicine as a learned and humane profession; pp. 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hogue C. The "possible poet": pain, form, and the embodied poetics of Adrienne rich in Wallace Stevens' Wake. Wallace Stevens J. 2001;25(1):40–51. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saha S, Bhatia A, Gupta L Perspectives on poetry in rheumatology. Indian J Rheumatol https://www.indianjrheumatol.com/preprintarticle.asp?id=315680. Accessed 8 Aug 2021

- 23.Elwadhi D. Gnarled fingers and broken youth. Indian J Rheumatol. 2021;16(2):231. doi: 10.4103/injr.injr_169_20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinto B, Ahmed S. The muscle rap. Indian J Rheumatol. 2020;15(6):225. doi: 10.4103/injr.injr_49_20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendelson A, Rabinowicz N, Reis Y, et al. Comics as an educational tool for children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2017;15:69. doi: 10.1186/s12969-017-0198-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rheumatoid arthritis comics: caption this comic (2019). Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/rheumatoid-arthritis/caption-this-comic#4. Accessed 15 Aug 2021

- 27.Coskun Benlidayi I. Diet in osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2019;41(9):1699–1700. doi: 10.1007/s00296-019-04379-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moll JM. Doctor-patient communication in rheumatology: studies of visual and verbal perception using educational booklets and other graphic material. Ann Rheum Dis. 1986;45(3):198–209. doi: 10.1136/ard.45.3.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hassan AA, Nasr MH, Mohamed AL, et al. Psychological affection in rheumatoid arthritis patients in relation to disease activity. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98(19):e15373. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000015373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khedekar S, Shimpi A, Shyam A, Sancheti P. Use of art as therapeutic intervention for enhancement of hand function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot study. Indian J Rheumatol. 2017 doi: 10.4103/0973-3698.199130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daykin N, Byrne E, Soteriou T, O'Connor S. The impact of art, design and environment in mental healthcare: a systematic review of the literature. J R Soc Promot Health. 2008;128(2):85–94. doi: 10.1177/1466424007087806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martha S, McCallie BSW, Claire M, et al. Progressive muscle relaxation. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2006;13(3):51–66. doi: 10.1300/J137v13n03_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evers S. Music for rheumatism—a historical overview. Z Rheumatol. 1990;49(3):119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Green MJ, Wall S. Graphic medicine—the best of 2020. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watts P, Walsh J (2019) Art therapy and rheumatology: using a collaborative approach to address the emotional needs of a child with Marfan syndrome. OUP Academic. Oxford University Press. https://academic.oup.com/rheumatology/article/58/Supplement_4/kez416.008/5575896. Accessed 2 Sep 2021

- 36.Watts P, Farrugia E, Davidson J, Leith K (2019) Does art therapy make a difference in the management of children and young people with rheumatic diseases: a multi-site service review to explore the impact of art therapy in two tertiary paediatric rheumatology services in Scotland. Ann Rheum Dis. https://ard.bmj.com/content/78/Suppl_2/1061.2.abstract

- 37.Camic PM. Playing in the mud: health psychology, the arts and creative approaches to health care. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(2):287–298. doi: 10.1177/1359105307086698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lwin MN, Serhal L, Holroyd C, Edwards CJ. Rheumatoid arthritis: the impact of mental health on disease: a narrative review. Rheumatol Ther. 2020;7(3):457–471. doi: 10.1007/s40744-020-00217-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jensen A, Bonde LO. The use of arts interventions for mental health and wellbeing in health settings. Perspect Public Health. 2018;138(4):209–214. doi: 10.1177/1757913918772602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stuckey HL, Noble J. The connection between art, healing, and public health: a review of current literature. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):254–263. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data pertaining to the study is included in the manuscript and as supplementary material.

Not applicable.