A third-dose COVID-19 vaccination was recommended in US long-term care settings on September 24, 2021,1 though only half of eligible nursing home residents have received a third dose as of December 5, 2021.2 On August 17, 2021, the province of Ontario, Canada, was relatively early to recommend a third-dose mRNA vaccination for residents in nursing home and assisted living settings in response to waning protection.3 Early real-world vaccine effectiveness data suggest substantially greater protection from Omicron (B.1.1.529; hereafter Omicron) infection for persons who have received a third-dose mRNA vaccine, compared with a 2-dose vaccination series.4 It is unclear if residents in long-term care settings mount a robust response to a third mRNA vaccination that may confer protection.

Methods

In this serial cross-sectional analysis, we examined SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody titers after both second and third vaccination in nursing home residents, and after third vaccination in assisted living (also known as retirement home) residents from Ontario, Canada. Residents were recruited from 17 nursing homes between March and November 2021, and 8 assisted living facilities between August and November 2021. Nursing home residents were administered Moderna Spikevax 100 μg (mRNA-1273; hereafter Moderna) or Pfizer-BioNTech Comirnaty 30 μg (BNT162b2; hereafter Pfizer) as per recommended 2 dose schedules. Nursing home and assisted living participants were administered either Moderna or Pfizer third-dose vaccine no earlier than 6 months post second dose. All protocols were approved by an ethics board, and informed consent was obtained.

Neutralization capacity of antibodies was assessed by cell culture assays with live SARS-CoV-2 virus, with data reported as geometric microneutralization titers at 50% (MNT50), which ranged from below detection (MNT50 < 10) to an MNT50 of 1280.3 , 5 Antibody neutralization was measured against the wild-type strain of SARS-CoV-2 and the beta variant of concern (B.1.351; hereafter beta variant). The beta variant, the most immunologically similar to omicron to date, was obtained through BEI Resources, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health: SARS-Related Coronavirus 2, Isolate hCoV-19/South Africa/KRISP-K005325/2020, NR-54009, contributed by Alex Sigal and Tulio de Oliveira.

Median serum microneutralization levels by days since vaccination for the SARS-CoV-2 wild-type strain and the beta variant were plotted for comparisons. Median serum microneutralization levels were compared by Kruskal-Wallis test for overlapping time points, and proportion below detection by chi-square, using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

A total of 418 nursing home residents were recruited 12-240 days post second dose, with an average (SD) age of 82.3 (11.5) years and 63.5% (263) being female sex. The Moderna-Moderna series was administered to 52.9% (221) residents, and the Pfizer-Pfizer series to 46.4% (194) residents. A total of 103 nursing home residents were recruited 12-77 days post third dose, with an average (SD) age of 83.8 (10.3) years and 62.8% (64) being female sex, whereas 95 assisted living residents were also recruited 12-77 days post third dose, with an average (SD) age of 85.0 (7.0) years and 65.3% (62) being female sex (P > .050 for comparisons). Nursing home residents received Moderna-Moderna-Moderna (66.0%), Pfizer-Pfizer-Moderna (17.5%), and Pfizer-Pfizer-Pfizer (16.5%), whereas assisted living residents received Pfizer-Pfizer-Pfizer (61.1%), Moderna-Moderna-Moderna (22.1%), Pfizer-Pfizer-Moderna (14.7%), and Moderna-Moderna-Pfizer (2.1%).

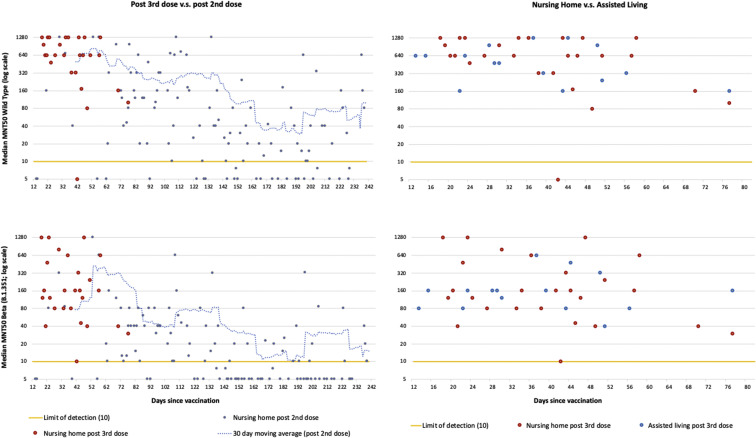

Figure 1 shows that, for the equivalent 12-77 days post vaccine period, residents post third dose had substantially higher neuralization titers for both the wild-type and beta variant (P < .001). For beta variant neuralization, 20.8% (11) of post–second dose residents were below the level of detection compared to none of the post–third dose residents (P < .001). Neutralization titers were substantially lower for beta variant neuralization (P < .001). There were no differences in median microneutralization titers between nursing home residents and assisted living residents 12-77 days post third dose, though 5.3% (5) of assisted living residents were below detection (P < .05).

Fig. 1.

Median microneutralization (MNT50) plots for SARS-Cov-2 wild-type strain (top) and beta variant of concern (B.1.351) (bottom). Nursing home residents post second compared to third mRNA dose (left), and post third mRNA dose for nursing home residents compared to assisted living residents (right).

Discussion

Our data strongly support third-dose vaccine recommendations, and equivalent polices for nursing homes and assisted living settings. Consistent with nonfrail populations,6 our findings suggest that residents mount a robust humoral response to a third mRNA vaccination, with greater neuralization capacity compared to a second-dose series. Continued monitoring of neutralization titers over time will determine the rate of degradation. Neutralization performance for the beta variant may not mimic performance for the omicron variant, which at the time of writing remains a concern.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge administrative and technical assistance from Tara Kajaks, PhD, Ahmad Rahim, MSc, Komal Aryal, MSc, Megan Hagerman, Braeden Cowbrough, MSc, Lucas Bilaver, Sheneice Joseph, Angela Huynh, PhD, and Leslie Tan who were compensated for their contributions by a grant funded by the Canadian COVID-19 Immunity Task Force at McMaster University.

Footnotes

Funding Sources: This work was funded by a grant from Canadian COVID-19 Immunity Task Force and Public Health Agency of Canada, Canada awarded to APC and DMEB. DMEB is the Canada Research Chair in Aging & Immunity. APC is the Schlegel Chair in Clinical Epidemiology and Aging. Funding support for this work was provided by grants from the Ontario Research Foundation, Canada, COVID-19 Rapid Research Fund, and by the Canadian COVID-19 Immunity Task Force awarded to IN. MSM is supported, in part, by an Ontario Early Researcher Award.

Additional Information: Data in this study were collected by the COVID-in-LTC Study Group. Members of the COVID-in-LTC Study Group include Jonathan L. Bramson, PhD, Eric D. Brown, PhD, Kevin Brown, PhD, David C. Bulir, MD, PhD, Judah A. Denburg, MD, George A. Heckman, MD, MSc, Michael P. Hillmer, PhD, John P. Hirdes, PhD, Aaron Jones, PhD, Mark Loeb, MD, MSc, Janet E. McElhaney, MD, Ishac Nazy, PhD, Nathan M. Stall, MD, Parminder Raina, PhD, Marek Smieja, MD, PhD, Kevin J. Stinson, PhD, Ahmad Von Schlegell, Arthur Sweetman, PhD, Chris Verschoor, PhD, Gerry Wright, PhD.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.12.035.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Press Release - CDC statement on ACIP booster recommendations. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/p0924-booster-recommendations-.html

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Nursing home COVID-19 vaccination data dashboard. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/covid19/ltc-vaccination-dashboard.html#4

- 3.Breznik J.A., Zhang A., Huynh A., et al. Antibody responses 3-5 months post-vaccination with mRNA-1273 or BNT163b2 in nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22:2512–2514. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UK Health Security Agency SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and variants under investigation in England. Technical briefing 31. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1040076/Technical_Briefing_31.pdf

- 5.Huynh A., Arnold D.M., Smith J.W., et al. Characteristics of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in recovered COVID-19 subjects. Viruses. 2021;13:697. doi: 10.3390/v13040697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falsey A.R., Frenck R.W., Jr., Walsh E.E., et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralization with BNT162b2 vaccine dose 3. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1627–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2113468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.