Abstract

The G and P types of 2,912 rotavirus-positive fecal specimens collected from eight geographical areas of the United Kingdom between 1995 and 1998 were determined by reverse transcription-PCR. Although 15 different G-P combinations were identified, G1P[8], G2P[4], G3P[8], and G4P[8] strains constituted 95% of all the rotaviruses typed. Other genotypes included G9P[6] and G9P[8], which were first identified in the United Kingdom in 1995, or other uncommon G and/or P types of strains that may have had an animal origin. Unusual combinations of G1 or G4 with P[4] and G2 with P[8] which may have arisen by reassortment between human strains were also identified. G1P[8] was the genotype most frequently found (57 to 87%) in each season, followed by G2P[4] in the 1995–1996 (18%) and 1997–1998 (16%) seasons, although the incidence of infection with this virus decreased significantly to 2% during the 1996–1997 season. Significant differences were seen in the distributions of G1P[8], G2P[4], and G9P[8] strains between children and adults, in the temporal distributions of G4P[8] and G9P[8] strains within a season, and in the geographical distributions of each of the four most common genotypes from one season to the next.

Group A rotaviruses are the major etiological agents of acute gastroenteritis in infants and children and in the young of many animals (31). Rotavirus infections are associated with high rates of morbidity throughout the world and high rates of mortality in developing countries, accounting for more than 800,000 infant deaths per year (5).

Rotaviruses are triple-layered icosahedral particles, and their genome consists of 11 segments of double-stranded RNA (15). The outer layer of rotaviruses is composed of two proteins, VP7 and VP4, encoded by RNA segments 9 (or segment 7 or 8, depending on the strain) and 4, respectively. These proteins elicit neutralizing antibody responses and form the basis of the current dual classification of group A rotaviruses into G and P types, with G standing for glycoprotein (VP7) and P standing for protease-sensitive protein (VP4) (15). Gene reassortment can take place upon dual infection of a single cell with two different strains both in vitro and in vivo (15). As the VP7 and VP4 genes segregate independently (15, 40), various combinations of P and G types have been detected in natural isolates. At least 14 different G types (G1 to G14) and 20 different P types (P1 to P20) have been identified (15). Of those, at least 10 G types and 11 P types have so far been found to infect humans (14).

Serotyping by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and with anti-VP7 serotype-specific monoclonal antibodies and genotyping by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and/or DNA sequencing have been widely used for G typing (for a review, see reference 14), and all G serotypes have been confirmed to be G genotypes. By contrast, not all P genotypes have been confirmed to be P serotypes yet, and therefore, molecular biology-based methods, mainly RT-PCR, have been used to define P types (20, 29).

The incidence of infection with particular group A rotavirus sero- and genotypes varies between geographical areas during a rotavirus season and from one season to the next. Globally, viruses carrying either G1, G2, G3, or G4 and P[4] or P[8] are the most common causes of rotavirus disease in humans, and different surveys indicate that G1P[8], G2P[4], G3P[8], and G4P[8] are the most common G and P types (for a review, see references 14 and 21). However, since the introduction and wider use of molecular biology-based typing methods over the last 10 years, rotavirus strains with G and P types other than those mentioned above have increasingly been reported in different parts of the world (for a review, see reference 14).

Human group A rotavirus strains that possess genes commonly found in animal rotaviruses have been isolated from infected children in both developed and developing countries. Strains such as G3 (found commonly in humans and also in many animal species such as cats, dogs, monkeys, pigs, mice, rabbits, and horses), G5 (found in pigs and horses), G6 and G8 (both found in cattle), G9 (found in pigs and lambs), and G10 (found in cattle) have been recorded in the human population throughout the world. Rotavirus G5 strains have been identified from children in Brazil, G6 strains have been found to infect children in Australia, and G8 strains have been identified in children from Australia, Malawi, Nigeria, Kenya, Guinea-Bissau, South Africa, and the United Kingdom. G9 rotavirus strains have been found to infect the human population in Brazil, Australia, India, the United States, Bangladesh, Malawi, Italy, France, The Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. G10 strains have been found to infect humans in India and the United Kingdom (for a review, see reference 14).

Unusual P types detected in humans include P[6] (common porcine type), P[9] (common feline type), P[11] (common bovine type), P[14] (found in porcine and lapine rotavirus strains), and P[19] (found in porcine rotavirus strains) (for a review, see reference 14). Repeated infection with group A rotaviruses occurs throughout life (42), with many of these infections being asymptomatic. The role of asymptomatic carriage in human-to-human transmission and transmission among other species is not known.

Research on a safe and effective rotavirus vaccine has been ongoing since the late 1970s, and two types of live-attenuated vaccines (with attenuation based upon gene reassortment of human rotaviruses with rotaviruses of animal origin), monovalent and multivalent, have been evaluated in several clinical trials (30, 32, 36). Other candidate rotavirus vaccines such as DNA vaccines, baculovirus-expressed virus-like particles, and microencapsidated rotavirus antigens are also actively being investigated, and some have shown promising results in animal models (10, 16, 26).

The extent to which rotavirus vaccines will produce heterotypic immunity is not yet established. Therefore, intensive surveillance of circulating wild-type rotavirus strains will be an important component of any vaccine implementation program. The emergence of new and immunologically distinct rotaviruses, possibly through the transmission of viruses across species barriers or through reassortment between animal and human rotaviruses, may make it necessary to modify vaccines from time to time.

We describe the molecular epidemiology of the rotavirus genotypes circulating in eight geographical regions of the United Kingdom (north, south, east, west, and middle England; Northen Ireland; Scotland; and Wales) during all or some of the rotavirus seasons between 1995 and 1998.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens.

A total of 3,453 fecal specimens obtained from children, adults, and elderly patients with diarrhea and determined to be rotavirus positive by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay, passive particle agglutination test, or electron microscopy were received for rotavirus typing. Samples were collected during the rotavirus seasons of 1995–1996 (n = 918), 1996–1997 (n = 1,233), and 1997–1998 (n = 1,302) by 15 collaborating laboratories throughout the United Kingdom (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The date of sample collection was available for 3,270 of 3,453 (94.7%) samples received, and the age or date of birth was provided for 2,824 of 3,453 (81.8%) patients. Details of the patients' attendance at a general practice or admission to a hospital were available for 1,556 of 3,453 (45.1%) of the patients included in this study. A rotavirus season was defined as a 12-month period that commenced in September of a year and that continued through to the end of August of the following calendar year.

TABLE 1.

Number of fecal specimens received from public health laboratories and other collaborating laboratories in the United Kingdom

| Location | Collaborating laboratory | No. of fecal specimens received in the following rotavirus season:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995–1996 | 1996–1997 | 1997–1998 | Total | ||

| Northern Ireland | Belfast | 118 | 111 | 229 | |

| East England | Cambridge | 121 | 58 | 76 | 255 |

| Norwich | 117 | 46 | 163 | ||

| Peterborough | 14 | 14 | 126 | 154 | |

| Middle England | Birmingham | 124 | 105 | 229 | |

| North England | Newcastle | 178 | 219 | 107 | 504 |

| Leeds | 41 | 107 | 121 | 269 | |

| South England | London | 160a | 15b | 175 | |

| Reading | 67 | 169 | 163 | 399 | |

| Portsmouth | 14 | 14 | |||

| West England | Bristol | 80 | 140 | 220 | |

| Plymouth | 219 | 154 | 373 | ||

| Wales | Cardiff | 21 | 21 | ||

| Rhyl | 80 | 157 | 105 | 342 | |

| Scotland | Dundee | 22 | 51 | 33 | 106 |

| Total | 918 | 1,233 | 1,302 | 3,453 | |

Samples collected at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital; typing data provided by D. Cubitt, Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, United Kingdom.

Outbreak specimens from two London hospitals.

FIG. 1.

Map of the United Kingdom indicating the eight geographical regions and the locations of the 15 laboratories from which rotavirus-positive samples were obtained. 1, Belfast; 2, Dundee; 3, Newcastle; 4, Leeds; 5, Rhyl; 6, Birmingham; 7, Peterborough; 8, Norwich; 9, Cambridge; 10, Bristol; 11, Cardiff; 12, Reading; 13, London; 14, Plymouth; 15, Portsmouth. The numbers of rotavirus-positive samples investigated in each region are indicated in parentheses.

All specimens were stored at 4°C as 10% fecal extracts in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2) or balanced salt solution prior to testing.

Genotyping.

Genotyping was performed by RT-PCR by published methods. Briefly, the viral double-stranded RNA was extracted from 200 μl of fecal suspension by the guanidinium isothiocyanate-silica method (7) and was transcribed into cDNA with random or specific oligonucleotide primers and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (27). The G- and P-typing nested PCRs were performed by using the primers and methods described elsewhere (20, 24, 29).

RESULTS

Combinations of G and P types of the rotavirus strains collected in the United Kingdom between 1995 and 1998.

A total of 150 of 3,453 (4.3%) of the samples were negative by both G- and P-specific RT-PCRs and were therefore excluded from further evaluation. For 2,912 of 3,303 samples (88.2%), both G and P types were determined by RT-PCR. Of the remaining 391 samples, 16 provided a first-round PCR amplicon but the virus could not be typed, in 298 samples one of the types, G or P, could not be determined, and 75 samples contained multiple virus types. The presence of multiple types was indicated by either a single G type and dual P types (2 and 52 samples in 1995–1996 and 1996–1997, respectively; no sample in 1997–1998), dual G types and a single P type (16, 2, and 3 samples in 1995–1996, 1996–1997, and 1997–1998, respectively), or dual G and P types (2 samples found in 1995–1996). The percentages of strains that were successfully typed or that had negative or incomplete results were not significantly different in the three rotavirus seasons. However, a significantly greater proportion of strains gave dual P types during the 1996–1997 season compared to the proportions in the other two seasons (52 of 1,233 in 1996–1997, compared to 2 of 918 in 1995–1996 and none in 1997–1998 [by the χ2 test, P < 0.001]). These strains were predominantly G1 in combination with P[4] and P[8], and the majority (80.4%) were from one geographical location.

Overall, 94.7% of the 2,912 strains fully typed had the G- and P-type combinations which are most commonly found in humans with rotavirus infections in temperate climates: G1P[8], G2P[4], G3P[8], and G4P[8]. G1P[8] was the most frequently found genotype in each of the rotavirus seasons (Table 2). Significant differences in the incidence of infection with common genotypes were identified between the three seasons studied: a significant increase in the incidence of infection with G1P[8] strains occurred between 1995–1996 and 1996–1997 (by the χ2 test, P < 0.001), and there was a subsequent decrease between 1996–1997 and 1997–1998 (by the χ2 test, P < 0.001). A significantly lower incidence of infection with G2P[4] strains was detected during the 1996–1997 season than during the 1995–1996 and 1997–1998 seasons (by the χ2 test, P < 0.001), and decreases in the incidences of infection with G3P[8] strains year by year (by the χ2 test, P < 0.001) and with G4P[8] strains between 1995–1996 and 1996–1997 (by the χ2 test, P < 0.001) were detected.

TABLE 2.

G and P genotype combinations of rotavirus strains collected from 15 different catchment areas in the United Kingdom during the 1995–1996, 1996–1997, and 1997–1998 rotavirus seasons

| Type by RT-PCR | No. (%) of strains collected in the following rotavirus seasons:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995–1996 | 1996–1997 | 1997–1998 | Total | |

| Common genotypes | ||||

| G1P[8] | 407 (56.9) | 919 (86.5) | 830 (73.1) | 2,156 (74.0) |

| G2P[4] | 128 (17.9) | 20 (1.9) | 180 (15.9) | 326 (11.2) |

| G3P[8] | 45 (6.3) | 45 (4.2) | 5 (0.4) | 95 (3.3) |

| G4P[8] | 83 (11.6) | 45 (4.2) | 53 (4.7) | 181 (6.2) |

| Subtotal | 663 (92.7) | 1,029 (96.8) | 1,068 (94.1) | 2,758 (94.7) |

| Uncommon genotypes | ||||

| G1P[4] | 11 (1.5) | 13 (1.2) | 9 (0.8) | 33 (1.1) |

| G1P[6] | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) |

| G1P[9] | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) |

| G2P[8] | 6 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.3) | 9 (0.3) |

| G3P[6] | 11 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (0.4) |

| G3P[9] | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.03) |

| G4P[4] | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 5 (0.2) |

| G4P[6] | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.03) |

| G8P[8] | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) |

| Subtotal | 33 (4.6) | 16 (1.5) | 18 (1.6) | 67 (2.3) |

| G9 strains | ||||

| G9P[6] | 18 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (0.7) | 26 (0.9) |

| G9P[8] | 1 (0.1) | 18 (1.7) | 42 (3.7) | 61 (2.1) |

| Subtotal | 19 (2.7) | 18 (1.7) | 50 (4.4) | 87 (3.0) |

| Total | 715 | 1,063 | 1,136 | 2,912 |

Less common genotypes were found for 154 of 2,912 (5.3%) of the rotavirus strains typed. These strains had either unusual combinations of the most common G and P types (G1P[4], G2P[8], and G4P[4]) or more unusual G and/or P types, such as G8, G9, P[6], and P[9], of which type G9 was the most numerous (Table 2).

Temporal distribution of rotavirus infections and genotypes in the United Kingdom.

Dates of sample collection were available for 3,156 of 3,303 (95.5%) of the samples confirmed to be rotavirus positive by RT-PCR. In 1995–1996, significant numbers of rotavirus isolates were detected in January, and the incidence peaked in April. In the following two seasons, rotavirus infections were observed in significant numbers in December, and the incidence peaked in March. A greater number of rotavirus-positive samples were also received in the summer and autumn months of 1997 than in the summer and autumn months of 1996 (Fig. 2). The temporal distribution of rotavirus infections in each of the eight geographical regions studied was not significantly different from the distribution throughout the whole country (data not shown).

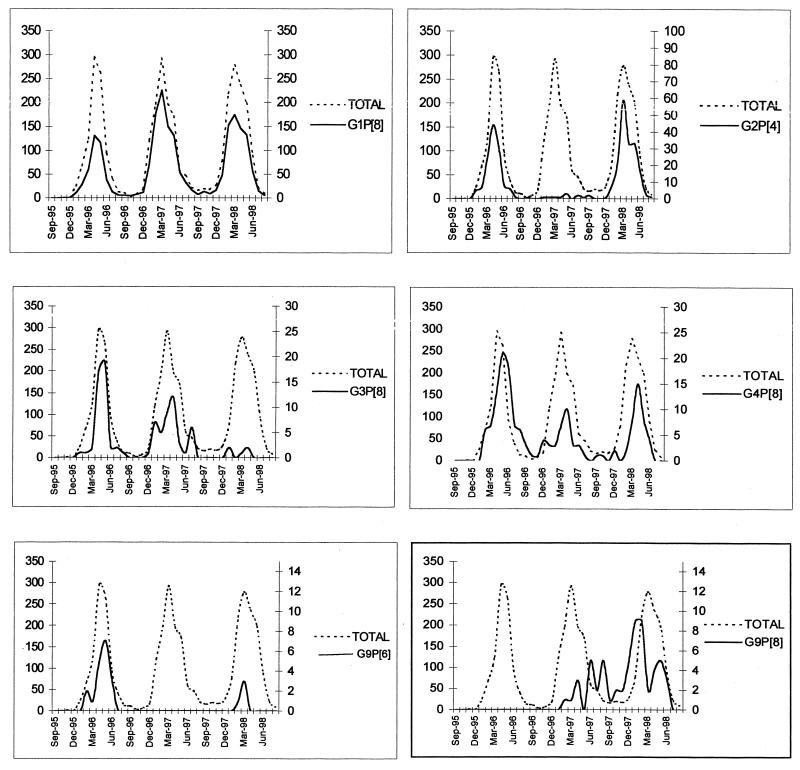

FIG. 2.

Temporal distribution of the more prevalent rotavirus genotypes typed during the rotavirus seasons of 1995–1996, 1996–1997 and 1997–1998 (solid line). The temporal distributions of all rotavirus-positive samples tested are represented (broken line) in each of the graphs for comparison. Numbers of samples are represented on the y axes; the scales of the y axes (right) have been adjusted to represent the incidences of the different types.

Three of the four most common rotavirus genotypes, G1P[8], G2P[4], and G3P[8], had contiguous patterns of temporal distribution in each of the rotavirus seasons, whereas the emergence and peak incidence of G4P[8] strains was delayed 4 to 6 weeks in comparison to the overall incidence of rotavirus infection during the 1995–1996 season (Fig. 2).

G9P[6] strains were detected in 1995–1996 and 1997–1998 but not in 1996–1997 (Table 2; Fig. 2). The temporal distribution of G9P[6] strains coincided with that of the strains of other rotavirus types (Fig. 2). However, the temporal distribution of G9P[8] strains in the 1996–1997 and 1997–1998 rotavirus seasons differed significantly from that of the strains of the other rotavirus genotypes. The incidence of infection with G9P[8] strains peaked toward the end of the 1996–1997 season (during the spring and early summer), and in 1997–1998 the highest incidence was observed at the beginning of the season (during the autumn months), with a second peak occurring in May (Fig. 2).

Distribution of rotavirus genotypes by age.

The age or date of birth was provided for a total of 2,714 of the 3,303 (82.2%) patients who were confirmed to be rotavirus positive, and of those, the G and P types of the rotavirus isolates were determined for 2,704. Most of the rotavirus infections were in children under 2 years of age, with a peak incidence between the ages of 6 to 12 months, although rotavirus infections were detected in the adult population (age range, 18 to 99 years; mean age, 66 years; median age, 75 years).

A significant decrease in the relative incidence of infections with G1P[8] strains was observed in individuals over 5 years of age, and in this age group, the incidences of infection with G2P[4] and G9P[8] strains were increased significantly in comparison to the incidences of infection with these strains in children under 5 years of age (Table 3). The highest incidence of infection with the G9 strains (both G9P[6] and G9P[8]) was found in the group aged 6 to 12 months. However, a statistically significant lower percentage of G9P[6] strains infected children under 2 years of age compared to the percentage of other rotavirus genotypes that infected children in this age group, and a higher percentage of G9P[6] strains than strains of other genotypes infected children ages 2 to 5 years (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Age distribution of patients infected with different rotavirus genotypes found between the 1995–1996 and 1997–1998 rotavirus seasons

| G-P combination | No. (%) of isolates from patients of the following ages:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| <5 yr | 5–99 yr | P value by χ2 test | |

| G1P[8] | 1,844 (77.1) | 189 (60.4) | <0.001 |

| G2P[4] | 247 (10.3) | 73 (23.3) | <0.001 |

| G3P[8] | 79 (3.3) | 16 (5.1) | NSa |

| G4P[8] | 95 (4.0) | 11 (3.5) | NS |

| G1P[4] | 27 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) | NCb |

| G1P[6] | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | NC |

| G1P[9] | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | NC |

| G2P[8] | 6 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | NC |

| G3P[6] | 10 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | NC |

| G3P[9] | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NC |

| G4P[4] | 5 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | NC |

| G4P[6] | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NC |

| G8P[8] | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | NC |

| G9P[6] | 21 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | NC |

| G9P[8] | 49 (2.0) | 18 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Total | 2,391 | 313 | |

NS, not significant.

NC, not calculated when the number of samples in one age group was less than 5.

Geographical distributions of the G1P[8], G2P[4], G3P[8], and G4P[8] rotavirus genotypes during consecutive seasons.

G1P[8] was the most prevalent rotavirus genotype, accounting for 74% of typed strains that originated from all geographical regions from which rotavirus-positive samples were collected during consecutive seasons (Table 2).

The incidence of infection with G2P[4] strains in most geographical regions was inversely related to that of infection with G1P[8], and G2P[4] the second most commonly found type in 1995–1996 and 1997–1998 in all regions except Wales, where G3P[8] was the second most frequently isolated type in 1995–1996. In the 1996–1997 season the percentages of G3P[8] and G4P[8] strains found were significantly higher that the percentage of G2P[4] strains found, although in total, over the three seasons, the incidence of infection with G3P[8] and G4P[8] strains was lower than the incidence of infection with G1P[8] and G2P[4] strains, a decrease year by year in the total numbers of G3P[4] and G4P[8] strains found was observed.

Incidence and distribution of G9 strains in the United Kingdom from 1995 to 1998.

Totals of 19, 18, and 51 G9 rotavirus strains were detected during the 1995–1996, 1996–1997, and 1997–1998 seasons, respectively. In 1995–1996, G9 strains were detected in only three of eight regions of the United Kingdom (south, north, and east of England), increasing to five regions (Wales and south, middle, north, and west of England) in 1996–1997 and to six regions (Scotland and south, middle, north, west, and east England) in 1997–1998 (Fig. 1). No G9 strains were found in Northern Ireland throughout the study. A concomitant year-by-year increase in the number of G9 isolates was detected in two locations (Leeds and Reading) over 3 years and in four different locations (Dundee, Peterborough, Birmingham, and Bristol) over 2 years. Statistically significant increases in the percentage of G9 strains isolated in Leeds and Birmingham were also detected, rising in Leeds from 3.2% of all strains in 1995–1996 to 5% of all strains in 1996–1997 and 28% of all strains in 1997–1998 (by the χ2 test, P < 0.001) and rising in Birmingham from 4% of all strains in 1996–1997 to 13% of all strains in 1997–1998 (by the χ2 test, P < 0.001). G9 rotaviruses were the second most frequently found type in Leeds and Birmingham in 1997–1998.

In 1995–1996, 18 of 19 (94.7%) of the G9 strains identified were of the G9P[6] type and 1 of 19 (5.3%) was of the G9P[8] type. In the next two rotavirus seasons, the numbers of G9P[8] strains increased significantly (from 1 in 1995–1996 to 18 in 1996–1997 and 42 in 1997–1998 [by the χ2 test, P < 0.001]), while that of G9P[6] decreased (from 18 in 1995–1996 to 8 in 1997–1998 [by the χ2 test, P < 0.001]; none were found in 1996–1997).

Distribution of genotypes in patients attending a general practice compared with those admitted to a hospital.

Details of patients' attendance at a general practice or admission to a hospital were available for 1,346 of the 3,303 (40.8%) patients confirmed to be rotavirus positive. No significant differences in the proportion of patients infected with G1P[8], G3P[8], and G4P[8] strains were observed between the two groups. The number of patients who were infected with G2P[4] strains and who remained in the community was significantly higher than the number of patients who required hospitalization (107 versus 72 [by the χ2 test, P < 0.001). The number of patients who were infected with rotavirus G9 strains (G9P[6] and G9P[8]) and who were admitted to a hospital was significantly higher than the number of patients who remained in the community (36 versus 8 [by the χ2 test, P < 0.001). The 11 patients infected with G3P[6] strains all resided in the same location (London), were infected during the same season (1995–1996), and were all admitted to a hospital.

DISCUSSION

A total of 43,719 cases of rotavirus infection were reported in England and Wales during the three rotavirus seasons from 1995 to 1998 (from Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre laboratory reports [www.phls.co.uk]). A study of infectious intestinal disease in England estimated that 32.4% of patients with rotavirus infection in the community present to a general practice and that only 3% are reported to a national surveillance system (43).

It can therefore be estimated that during the three seasons included in this study, approximately 1.5 million cases of acute gastroenteritis in England and Wales would have been caused by group A rotaviruses. The rotavirus-positive samples analyzed in this study thus represent ∼0.2% of the total estimated number of cases of rotavirus infections in England and Wales.

This study of the molecular epidemiology of rotavirus strains circulating in the United Kingdom between 1995 and 1998 is, to our knowledge, the most systematic study of rotavirus diversity in one country encompassing several consecutive rotavirus seasons. In the whole of Europe, from published results, the total number of samples typed, excluding those typed in this study, adds up to <7,000 in a total of 14 studies covering periods from 1 to 10 years (33). Similarly, rotavirus surveillance in the United States, undertaken in 1996 as a prelude to the introduction of a comprehensive rotavirus vaccination program, examined a total of 1,316 rotavirus-positive samples between the rotavirus seasons of 1996–1997 and 1998–1999 (25, 37), representing 0.01% of the 3.5 million rotavirus infections estimated to occur each year in the United States (9).

In the current study conducted in the United Kingdom, 4% of the samples were negative by RT-PCR. This result is in agreement with the proportion of 3 to 5% false-positive results for rotavirus seen by commercial assays used to detect rotavirus antigens in clinical samples (J. J. Gray et al., unpublished data).

Although rotaviruses of 15 different G and P combinations were detected during the three seasons in the eight geographical regions studied, strains of genotypes G1P[8], G2P[4], G3P[8], and G4P[8] constituted almost 95% of all the viruses typed (93, 97, and 94% in the 1995–1996, 1996–1997 and 1997–1998 seasons, respectively), in agreement with other published studies (for reviews, see references 14 and 21). Significant differences in the incidence and distribution of the four most common G-P genotype combinations were observed within each season and between seasons.

Although G1P[8] was the most frequently found G-P combination overall and in each of the three seasons, G2P[4] strains made up a significant proportion of the strains in the 1995–1996 and 1997–1998 seasons, while in the 1996–1997 season only very small numbers were detected in some of the geographical regions. G2P[4] strains have been found worldwide in a number of studies in which a season of high relative incidence is followed by one of low incidence (4, 17, 19, 22). The significantly higher relative incidence in older age groups may suggest antigenic variability among G2P[4] strains. Also, the failure to detect G2P[4] strains with three different G2-specific monoclonal antibodies may suggest a significant antigenic change since these antibodies were raised (27). In this study we have found no association between the severity of illness, defined by hospitalization, and infection with G2P[4] strains, although a possible association of G2 strains with more severe disease has been reported (6).

Approximately 5% of the specimens either had unusual combinations of the common G and P types, which may have arisen through the reassortment in nature of the more common strains, or possessed uncommon G and/or P types. These could have an animal origin and could have emerged through reassortment between animal and human rotavirus strains or by zoonotic transmission. Numerous studies carried out in different countries have increasingly found unusual genotypes and significant percentages of samples with mixtures of genotypes (for a review, see reference 14). The mixtures of genotypes are likely be the result of dual infections, which may lead to the emergence of novel rotavirus G-P combinations through reassortment (8). Mixed infections with rotaviruses from different species in tissue culture produce large numbers of virus reassortants (2), and several studies have found evidence of reassortment in vivo between different human strains and also between animal and human strains (8, 13, 23, 38, 44). In this study rotaviruses G1P[9], G3P[9], G8P[8], G9P[6], and G9P[8] were found to be circulating in the United Kingdom, and there is now evidence of reassortment between cocirculating strains in the population in the United Kingdom (M. Iturriza-Gómara et al., unpublished data), and previous studies have also identified human rotavirus G8 and G10 strains in the United Kingdom (3, 39).

Dual infections, characterized by more than one G, P, or G and P type, were found in 2.2% of the rotavirus-positive samples genotyped in this study. Samples containing two G types and two P types were found on two occasions in 1995–1996 and contained a mixture of the G2, G4, P[4], and P[8] genotypes. Samples containing dual G types in combination with a single P type (P[8]) were associated with the majority of dual infections in the two seasons (1995–1996 and 1997–1998), in which a greater diversity of cocirculating genotypes was detected. The dual infections found in 1995–1996, characterized by samples containing G1 and G9 with P[6] and G1 and G9 with P[8], may have resulted in reassortment, with G9P[8] becoming the predominant G9 strain in subsequent years. Reassortment of rotaviruses in the developing world is thought to be facilitated by close contact among humans and between humans and domestic livestock, especially in areas prone to flooding or with a monsoon climate, where dual infections are frequent (1). In the United Kingdom, contact with farm animals is limited, but opportunities for animal rotaviruses to infect humans arise through close contact with domestic pets, in particular, cats and dogs. The unusual strains found in the United Kingdom may have been introduced by importation from other countries where unusual genotypes are more prevalent or may have been introduced into the human population, by zoonotic transmission from animals such as dogs and cats, in which G3P[9] strains are common, and lambs or pigs, in which G9 strains are common (18, 34, 35, 38), or by reassorment between animal and human strains. By analogy to influenza surveillance, in which the analysis of influenza virus isolates from animals is recognized as increasingly important for the evaluation of its epidemiology in humans, characterization of rotavirus strains from animals in close contact with humans would have to complement the surveillance of human rotavirus infections.

G9 strains were first identified in the human population in the United States in 1983 (11), but they were not reported again until more than a decade later (37). The first finding of G9 strains in the United Kingdom in 1995–1996 coincides with the emergence of G9 strains in Bangladesh (41) and the reemergence and spread of G9 strains in the United States (41); V. Jain, F. Clark, P. Dennehy, K. Zangwill, C. Kirkwood, R. Glass, and J. Gentsch, Abstr. ASV 18th Annu. Meet. abstr. w43-4, p. 136, 1999). Retrospective studies of strains from the United Kingdom isolated before 1995 currently under way in our laboratory have so far failed to identify any G9 strains.

Although the incidence of infection with G9 strains in the United Kingdom was low in comparison to the incidence of infection with the more common G1, G2, or G4 strains, there was an increase in the geographical spread year by year, and the incidence in those geographical areas from which samples were received and tested over three consecutive seasons also increased significantly. In 1997, G9P[8] strains were found in the summer months, outside the normal rotavirus season.

Sequencing of the VP7 and VP4 genes revealed the existence of lineages within the G9 strains found in the United Kingdom (28). The sequences of the G9 VP7 genes were highly homologous, and a chronological clustering into three lineages was observed. Sequencing of the P[6] and P[8] VP4 genes revealed that the sequences obtained from G9P[6] strains were highly conserved; however, those from G9P[8] strains clustered into global lineages previously described for the VP4 genes associated with other G types (28). These data as well as the temporal distribution of G9P[8] strains in 1997 appear to indicate a recent introduction of G9P[6] and G9P[8] strains into the population in the United Kingdom as two separate events, or more likely, G9P[8] may have originated through reassortment between the newly introduced G9P[6] strains and the more frequently occurring cocirculating G1P[8], G3P[8], or G4P[8] viruses. G9P[8] strains spread throughout the United Kingdom from one region during the 1995–1996 season to six different regions during the 1997–1998 season, although the incidence of G9P[6] strains decreased throughout this period and may suggest that they have a replicative disadvantage in humans, consistent with strains of animal origin. The VP4 gene of P[8] strains may confer a replicative advantage to the G9P[8] strains compared with the replication efficiencies of G9P[6] strains.

The emergence of G9 strains, G9P[6] and G9P[8], in the United Kingdom presents a unique opportunity to study the introduction and spread of emerging viruses into the community and their interactions with other cocirculating rotaviruses. Sequencing and phylogenetic analyses of the 11 genome segments of these strains may reveal their origin and evolution and possibly provide an insight into why some strains predominate year by year.

Since G9 strains are not represented in any of the proposed candidate rotavirus vaccines (12, 16, 26, 32, 36), cross-protection against infection and/or disease caused by strains other than G1 to G4 strains may or may not be conferred. The higher prevalence of G9 strains in the older age groups and the spread and increased incidence of infection with G9 types in some of the locations where they have been present for a longer period may indicate a lack of cross-protection by antibodies specific to the other common types. Recently, G9P[6] rotaviruses have been found in outbreaks in nurseries in The Netherlands (M. Koopmans, Eurosurveillance weekly, ProMED 200000107124931 [www.promed.org]). This may also indicate a lack of cross-protection by maternal antibodies and would support the idea that G9 strains are a recent introduction into Europe. If cross-protection is not achieved, a selective increase in the prevalence of G9 or other emerging rotavirus strains could result after widespread use of vaccines, threatening the utility of a vaccine specific for G1 to G4 rotaviruses and requiring vaccines to be modified from time to time.

Although geographical and temporal differences in the distributions of the most prevalent genotypes have been reported in numerous studies, to date no epidemiological pattern has emerged globally. This may be due to the relatively small number of strains genotyped worldwide or may be associated with the constant introduction of new virus variants into the population (14, 23).

The complex relationships among cocirculating rotavirus strains, the relative infectivities of different genotypes, and the correlates of immunological protection still require elucidation before an accurate model of the epidemiology of rotaviruses can be established.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all colleagues in collaborating laboratories (listed in Table 1), H. O'Neill, M. Sillis, P. Nielsen, G. Beards, A. Turner, R. Eglin, J. Sellwood, G. Underhill, O. Caul, D. Dance, D. Westmoreland, N. Looker, and P. McIntyre, for their interest and effort in collecting and providing specimens; David Cubitt, Hospital for Children, Great Ormond Street, London, United Kingdom, contributed rotavirus typing data.

This work was supported by a grant from the Public Health Laboratory Service, London, United Kingdom.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed M U, Urasawa S, Taniguchi K, Urasawa T, Kobayashi N, Wakasugi F, Islam A I, Sahikh H A. Analysis of human rotavirus strains prevailing in Bangladesh in relation to nationwide floods brought by the 1988 monsoon. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2273–2279. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2273-2279.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen A, Desselberger U. Reassortment of human rotaviruses carrying rearranged genomes with bovine rotavirus. J Gen Virol. 1985;66:2703–2714. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-66-12-2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beards G, Xu L, Ballard A, Desselberger U, McCrae M A. A serotype 10 human rotavirus. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1432–1435. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.6.1432-1435.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beards G M, Desselberger U, Flewett T H. Temporal and geographical distributions of human rotavirus serotypes, 1983 to 1988. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2827–2833. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.12.2827-2833.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bern C, Martines J, Zoysa I, Glass R I. The magnitude of the global problem of diarrhoeal disease: a ten-year update. Bull W H O. 1992;70:705–714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bern C, Unicomb L, Gentsch J R, Banul N, Yunus M, Sack R B, Glass R I. Rotavirus diarrhea in Bangladeshi children: correlation of disease severity with serotypes. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:3234–3238. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.12.3234-3238.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boom R, Sol C J A, Salismans M M M, Jansen C L, Wertheim-van Dillen P M E, van den Noordaa J. Rapid and simple method for the purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:495–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Browning G F, Snodgrass D R, Nakagomi O, Kaga E, Sarasini A, Gerna G. Human and bovine serotype G8 rotaviruses may be derived by reassortment. Arch Virol. 1992;125:121–128. doi: 10.1007/BF01309632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Laboratory-based surveillance for rotavirus—United States, July 1996–June 1997. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46:1092–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen S C, Jones D H, Fynan E F, Farrar G H, Clegg J C, Greenberg H B, Herrmann J E. Protective immunity induced by oral immunization with a rotavirus DNA vaccine encapsulated in microparticles. J Virol. 1998;72:5757–5761. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5757-5761.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark H F, Hoshino Y, Bell L M, Groff J, Hess P, Bachman P, Offit P A. Rotavirus isolate WI61 representing a presumptive new human serotype. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1757–1762. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.9.1757-1762.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark H F, Offit P A, Ellis R W, Eiden J J, Krah D, Shaw A R, Pichichero M, Treanor J J, Borian F E, Bell L M, Plotkin S A. The development of multivalent bovine rotavirus (strain WC3) reassortant vaccine for infants. J Infect Dis. 1996;174(Suppl. 1):S73–S80. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.supplement_1.s73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunliffe N A, Gondwe J S, Broadhead R L, Molyneux M E, Woods P A, Bresee J S, Glass R I, Gentsch J R, Hart C A. Rotavirus G and P types in children with acute diarrhea in Blantyre, Malawi, from 1997 to 1998: predominance of novel P[6]G8 strains. J Med Virol. 1999;57:308–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desselberger, U., M. Iturriza-Gómara, and J. Gray. Rotavirus epidemiology and surveillance. In D. Chadwick, J. Goode, M. K. Estes, and U. Desselberger (ed.), Viral gastroenteritis. Novartis Foundation Symposium, vol. 238, in press. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Estes M. Rotaviruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, et al., editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 1625–1655. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estes M K, Ball J M, Crawford S E, O'Neal C, Opekun A A, Graham D Y, Conner M E. Virus-like particle vaccines for mucosal immunization. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;412:387–395. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1828-4_61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer T K, Steinsland H, Molbak K, Ca R, Gentsch J R, Valentiner-Branth P, Aaby P, Sommerfelt H. Genotype profiles of rotavirus strains from children in a suburban community in Guinea-Bissau, Western Africa. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:264–267. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.264-267.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzgerald T A, Munoz M, Wood A R, Snodgrass D R. Serological and genomic characterisation of group A rotaviruses from lambs. Arch Virol. 1995;140:1541–1548. doi: 10.1007/BF01322528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flores J, Taniguchi K, Green K, Pérez-Schael I, Garcia D, Sears J, Urasawa S, Kapikian A Z. Relative frequencies of rotavirus serotypes 1, 2, 3, and 4 in Venezuelan infants with gastroenteritis. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2092–2095. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.10.2092-2095.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gentsch J R, Glass R I, Woods P, Gouvea V, Gorziglia M, Flores J, Das B K, Bhan M K. Identification of group A rotavirus gene 4 types by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1365–1373. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.6.1365-1373.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gentsch J R, Woods P A, Ramachandran M, Das B K, Leite J P, Alfieri A, Kumar R, Bhan M K, Glass R I. Review of G and P typing results from a global collection of rotavirus strains: implications for vaccine development. J Infect Dis. 1996;174(Suppl. 1):S30–S36. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.supplement_1.s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Georges Courbot M C, Beraud A M, Beards G M, Campbell A D, Gonzalez J P, Georges A J, Flewett T H. Subgroups, serotypes, and electrophoretypes of rotavirus isolated from children in Bangui, Central African Republic. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:668–671. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.4.668-671.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gouvea V, Brantly M. Is rotavirus a population of reassortants? Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:159–162. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88908-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gouvea V, Glass R I, Woods P, Taniguchi K, Clark H F, Forrester B, Fang Z Y. Polymerase chain reaction amplification and typing of rotavirus nucleic acid from stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:276–282. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.2.276-282.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffin D, Kirkwood C, Parashar U, Woods P, Bresse J, Glass R, Gentsch J the National Rotavirus Surveillance System Collaborating Laboratories. Surveillance of rotavirus strains in the United States: identification of unusual strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2784–2787. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.7.2784-2787.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrmann J E, Chen S C, Fynan E F, Santoro J C, Greenberg H B, Wang S, Robinson H L. Protection against rotavirus infections by DNA vaccination. J Infect Dis. 1996;174(Suppl. 1):S93–S97. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.supplement_1.s93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iturriza-Gómara M, Green J, Brown D W, Desselberger U, Gray J J. Comparison of specific and random priming in the reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction for genotyping group A rotaviruses. J Virol Methods. 1999;78:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iturriza-Gómara M, Cubitt D, Steele D, Green J, Brown D, Kang G, Desselberger U, Gray J. Characterisation of rotavirus G9 strains isolated in the UK between 1995 and 1998. J Med Virol. 2000;61:510–517. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200008)61:4<510::aid-jmv15>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iturriza-Gómara M, Green J, Brown D W, Desselberger U, Gray J J. Diversity within the VP4 gene of rotavirus P[8] strains: implications for reverse transcription-PCR genotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:898–901. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.898-901.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joensuu J, Koskenniemi E, Pang X L, Vesikari T. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of rhesus-human reassortant rotavirus vaccine for prevention of severe rotavirus gastroenteritis. Lancet. 1997;350:1205–1209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)05118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kapikian A Z, Chanock R M. Rotaviruses. In: Fields B N, et al., editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 1657–1708. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kapikian A Z, Hoshino Y, Chanock R M, Pérez-Schael I. Jennerian and modified Jennerian approach to vaccination against rotavirus diarrhea using a quadrivalent rhesus rotavirus (RRV) and human-RRV reassortant vaccine. Arch Virol Suppl. 1996;12:163–175. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6553-9_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koopmans M, Brown D. Seasonality and diversity of group A rotaviruses in Europe. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1999;88:14–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1999.tb14320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mochizuki M, Nakagomi T, Nakagomi O. Isolation from diarrheal and asymptomatic kittens of three rotavirus strains that belong to the AU-1 genogroup of human rotaviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1272–1275. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1272-1275.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakagomi T, Nakagomi O. RNA-RNA hybridization identifies a human rotavirus that is genetically related to feline rotavirus. J Virol. 1989;63:1431–1434. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.3.1431-1434.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pérez-Schael I, Guntiñas M J, Perez M, Pagone V, Rojas A M, Gonzalez R, Cunto W, Hoshino Y, Kapikian A Z. Efficacy of the rhesus rotavirus-based quadrivalent vaccine in infants and young children in Venezuela. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1181–1187. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710233371701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramachandran M, Gentsch J R, Parashar U D, Jin S, Woods P A, Holmes J L, Kirkwood C D, Bishop R F, Greenberg H B, Urasawa S, Gerna G, Coulson B S, Taniguchi K, Bresee J S, Glass R I. Detection and characterization of novel rotavirus strains in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3223–3229. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3223-3229.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santos N, Lima R, Nozawa C, Linhares R, Gouvea V. Detection of porcine rotavirus type G9 and of a mixture of types G1 and G5 associated with Wa-like VP4 specificity: evidence for natural human-porcine genetic reassortment. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2734–2736. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2734-2736.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steele A, Parker S, Peenze I, Pager C, Taylor M, Cubbitt W. Comparative studies of human rotavirus serotype G8 strains recovered in South Africa and the United Kingdom. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:3029–3034. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-11-3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taniguchi K, Urasawa T, Urasawa S. Independent segregation of the VP4 and the VP7 genes in bovine rotaviruses as confirmed by VP4 sequence analysis of G8 and G10 bovine rotavirus strains. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:1215–1221. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-6-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Unicomb L E, Podder G, Gentsch J R, Woods P A, Hasan K Z, Faruque A S, Albert M J, Glass R I. Evidence of high-frequency genomic reassortment of group A rotavirus strains in Bangladesh: emergence of type G9 in 1995. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1885–1891. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1885-1891.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Velazquez F R, Matson D O, Calva J J, Guerrero L, Morrow A L, Carter Campbell S, Glass R I, Estes M K, Pickering L K, Ruiz Palacios G M. Rotavirus infections in infants as protection against subsequent infections. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1022–1028. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wheeler J G, Sethi D, Cowden J M, Wall P G, Rodrigues L C, Tompkins D S, Hudson M J, Roderick P J. Study of infectious intestinal disease in England: rates in the community, presenting to general practice, and reported to national surveillance. The Infectious Intestinal Disease Study Executive. Br Med J. 1999;318:1046–1050. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7190.1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zao C L, Yu W N, Kao C L, Taniguchi K, Lee C Y, Lee C N. Sequence analysis of VP1 and VP7 genes suggests occurrence of a reassortant of G2 rotavirus responsible for an epidemic of gastroenteritis. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1407–1415. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-6-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]