Abstract

The present study entails the usefulness of thermophilic amidase-producing bacterium in the biotransformation of benzamide to benzohydroxamic acid (BHA). A bacterium Bacillus smithii IIIMB2907 was isolated from a soil sample collected from hot springs of Manikaran, Himachal Pradesh, India. The whole cells of the bacterium displayed versatile substrate specificity by exhibiting significant activity with a diverse range of amides. In addition, amidase from thermophilic bacterium was induced by adding Ɛ-caprolactam in the mineral base media. The optimum temperature and pH of acyltransferase activity of amidase enzyme were found to be 50 °C and 7.0, respectively. Interestingly, half-life (t1/2) of this enzyme was 17.37 h at 50 °C. Bench-scale production and purification of BHA was carried out at optimized conditions which resulted in the recovery of 64% BHA with a purity of 96%. Owing to this, the reported process in the present study can be considered of immense industrial significance for the production of BHA.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-022-03109-2.

Keywords: Acyltransferase activity, Benzohydroxamic acid, Biotransformation, Thermophilic amidase

Introduction

Hydroxamic acids (R-CONHOH), known for their ability to form stable chelates with metal ions, find applications as growth factors, food additives, antibiotics, antifungal agents, tumor inhibitors, siderophores, enzyme inhibitors and bioremediation (Bhatia et al. 2013a; Kumari and Chand 2017; Ruan et al. 2016; Pandey et al. 2019; Bhalla et al. 2018). These compounds are being synthesized by chemical routes which includes N-alkylation of simple o-substituted hydroxylamine with a variety of alkylating agents or by the direct oxidation of lysine and ornithine using dimethyldioxirane (Bertrand et al. 2013). The synthesis of hydroxamic acids by chemical processes is accompanied with by-products; thus, further processing is required to get pure hydroxamic acids and their derivatives (Bhatia et al. 2013a). One such important hydroxamic acid which finds application in pharmaceutical industries is benzohydroxamic acid (BHA). Many bioactivities have been attributed to BHA including anti-HIV, antimicrobial, antineoplastic agent, antianemic, and potential inhibitor of leukemia and in the treatment urea plasma. Considering the aforementioned properties of BHA, it is indeed pertinent to carry out its green synthesis using amidase.

The utility of amidase for the synthesis of hydroxamic acid is being explored by researchers using the acyltransferase activity of the enzyme (Fournand et al. 1998). Among the reported amidases from various microorganisms, thermophilic amidase is preferred for synthesizing various pharmaceutically essential hydroxamic acids. Some of the amides are poorly soluble in an aqueous system at lower temperatures and therefore require a relatively higher temperature to get completely solubilized for the better action of enzyme. Therefore, thermophilic amidase-producing microorganisms may be beneficial for the efficient production of hydroxamic acids at higher temperature from their respective amides (Sharma et al. 2012; Kumari and Chand 2017). For example, Mehta et al. (2016) reported identification, purification, and characterization of a novel thermo-active amidase from Geobacillus subterraneus RL-2a. Furthermore, Sogani et al. (2012) also reported the biotransformation of an amide using Bacillus sp. with resting cells of the strain containing active acyltransferase enzyme. Sodium alginate enzyme immobilized beads were used for the biotransformation reaction under optimized conditions, i.e., 55 °C for 20 min. In addition, Bhatia et al. (2013a) reported the production of BHA from benzamide using acyltransferase activity of amidase from Alcaligenes sp. MTCC 10,674 at 50 °C. In view of the vast applications of thermophilic amidase for the synthesis of pharmaceutically active hydroxamic acids, the present study embarks on the isolation and screening of an efficient amidase-producing bacterial culture from water and soil samples collected from hot water springs of Manikarna, Himachal Pradesh, India. Subsequently, potential bacterial culture was used to synthesize pharmaceutically important benzohydroxamic acid using its acyltransferase activity under optimized conditions.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and media components

All amides and media components used for the present study were of analytical grade and procured from Sigma-Aldrich, USA, Merck (Germany), and Himedia (India). DNA isolation kit was purchased from Zymoresearch.

Location of the study area and sample collection

Soil (from the bottom of hot water spring) and water samples were collected from hot water springs of Manikaran, Himachal Pradesh, India (Latitude 32.0268° N, Longitude 77.3511° E). The soil samples were collected in autoclaved bags, while the water samples were collected in 30 mL glass vials. The temperature of the samples at the sampling site was 80 ± 2 °C, whereas the pH was ~ 7.0 ± 0.5, which was analyzed by pH strips. Samples were further processed after 48 h of sample collection.

Sample processing, isolation, and characterization of amidase-producing microorganism

Isolation of amidase-producing microorganisms was carried out by inoculating one gram of soil or 1 mL of water to 50 mL modified mineral base (MB) media (Babu and Choudhury 2013; Singh et al. 2018, 2019) containing 20 mM benzamide as a nitrogen source in a 250 mL conical flask supplemented with 1 mL/L trace elements. The flask was incubated at 50 °C with 200 rpm for 5 days that also served as a seed culture. Furthermore, 1% of seed culture was used to inoculate 50 mL of the same media and incubated at the above-mentioned conditions for 5 days. Subsequently, 50 µL from the media was taken and plated on MB agar plates containing benzamide as a nitrogen source. The composition of mineral base media was as follows: 5 g/L glycerol, 0.2 g/L citric acid, 0.27 g/L KH2PO4, 0.174 g/L K2HPO4, 5 g/L NaCl, 0.2 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 0.01 g/L CaCl2, and trace elements solution (0.3 g/L H3BO3, 0.2 g/L CoCl2·6H2O, 0.1 g/L ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.03 g/L MnCl2·4H2O, 0.03 g/L Na2MoO4·H2O, 0.02 g/L NiCl2·6H2O, and 0.01 g/L CuCl2·2H2O. Based on their morphology, individual colonies were picked and streaked on MB agar plates containing benzamide as a nitrogen source for obtaining pure cultures. The purified cultures were then screened for the amidase-producing bacteria by examining their amide hydrolase activity.

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from the selected bacterial strains using bacterial DNA isolation kit. gDNA of the purified culture was subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify the 16S rDNA sequence using B27F forward primer (5’-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3') and B1507R reverse primer (5’-TACCTTGTTACGACTT-3'). PCR was carried out in a BioRad T100™ thermocycler under the following amplification conditions: an initial denaturation step of 5 min at 95 °C followed by 35 amplification cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 53 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1.3 min and a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min (Sharma et al. 2018). The sequenced PCR products were compared to known existing DNA sequences in NCBI GenBank using BLASTn program (Dhagat and Jujjavarapu 2020). In addition to molecular characterization, the isolated strains were also identified based on their morphological and biochemical features. Morphological identification was carried out by examining their colony morphology, gram staining followed by microscopic analysis. Whereas biochemical characterization was performed using indole, methyl red, Voges–Proskauer, citrate, casein, starch hydrolysis, gelatin hydrolysis, nitrate reduction, catalase, oxidase, esculin hydrolysis, and H2S gas production test.

Screening of amidase-producing microorganism

Isolated cultures were grown in 50 mL MB media containing 20 mM benzamide as a nitrogen source in a 250 mL conical flask supplemented with 1 mL/L trace elements. Successively 5 ml of culture broth was centrifuged at 13,000 g (4 °C) and the pellet was washed twice with 0.1 M potassium phosphate-buffer solution (pH 7) (PBS) and re-dissolved in 100 μL of PBS. Amide hydrolase activity of amidase was assayed using benzamide as a substrate. The main reaction mixture contained 400 μL of 10 mM benzamide (prepared in 0.1 M PBS) and 100 μL of whole-cell suspension. In addition to this, a control in which 100 μL of whole-cell suspension was taken with 400 μL of 0.1 M PBS and a reagent blank containing 400 μL of 10 mM benzamide along with 100 μL of 0.1 M PBS were also processed for any possible spontaneous reactions. The reaction was incubated at 50 °C for 30 min and terminated by adding 10 μL of 1 N HCl followed by centrifugation at 13,000 g, 4 °C. The supernatant was collected and ammonia that was released in the reaction was determined using the Berthelot method (Mehta et al. 2016; Babu et al. 2010; Sharma et al. 2018). One unit of amidase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme catalyzing the hydrolysis of amide for the formation of one micromole of ammonia per min under assay conditions.

For acyltransferase assay, 400 μL of 10 mM benzamide and 100 μL of whole-cell suspension with 250 μL of 1.5 M hydroxylamine solution (prepared in 0.1 M PBS) as a co-substrate were used in the primary reaction mixture. In control, 100 μL of whole-cell suspension, 400 μL of 0.1 M PBS, 250 μL of 1.5 M hydroxylamine solution as a co-substrate were taken. Additionally, a reagent blank containing 400 μL of 10 mM benzamide, 100 μL of 0.1 M PBS, and 250 μL of co-substrate 1.5 M hydroxylamine solution was also processed for any possible spontaneous reactions. The reaction was allowed to run for 30 min at 50 °C and terminated by adding 10 μL of 1 N HCl followed by centrifugation at 13,000 g, 4 °C. Furthermore, the supernatant from all the three samples were collected. The hydroxamic acid produced in the reaction was determined by Brammar and Clarke’s method for the colorimetric determination of the red–brown complexes with Fe (III) (Bhatia et al. 2013a, b). One unit of acyltransferase activity of amidase was defined as the amount of enzyme required to convert one micromole of benzamide to benzohydroxamic acid per min under the assay conditions.

Determination of thermophilic nature of the screened microorganism

The thermophilic nature of isolated microorganism was determined by studying the effect of temperature on growth and amidase production with temperatures ranging from 30 to 60 °C with an interval of 10 °C. Acyltransferase activity assay was also performed under similar assay conditions.

Substrate specificity

The substrate specificity of the isolated culture was determined using cells grown in MB media for 20 h and harvested by centrifugation. Subsequently, the obtained cell pellet was washed twice and suspended in 0.1 M PBS to determine its substrate specificity. Amide hydrolase activity of the culture was analyzed with different amides (20 mM each of acrylamide, acetamide, benzamide, butyramide, nicotinamide, propionamide, adipamide, malonamide, succinamide, valeramide, pyrazinamide, isonicotinamide, isobutyramide, and methacrylamide) dissolved in 0.1 M PBS and incubated with their control and reagent blank at 50 °C for 30 min.

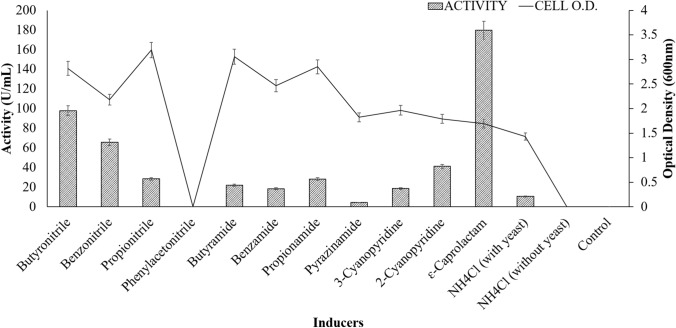

Effect of inducers on cell growth and amidase activity

The isolated strain was grown in MB media to determine the effect of different inducers on cell growth and its acyltransferase activity. The media was supplemented with 20 mM of butyronitrile, benzonitrile, propionitrile, phenylacetonitrile, butyramide, benzamide, propionamide, pyrazinamide, 3-cyanopyridine, 2-cyanopyridine, Ɛ -caprolactam, NH4Cl (with yeast extract), and NH4Cl (without yeast extract), and incubated for 20 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 g followed by washing with 0.1 M PBS. Cell pellets of induced culture were suspended in PBS for growth and activity analysis. Simultaneously, a culture grown in MB media without an inducer was also taken as a control.

Effect of substrate concentration, temperature, and pH

The effect of substrate concentration on enzyme activity was analyzed by taking the substrate concentrations from 1 to 100 mM while keeping the co-substrate concentration constant at 500 mM. Furthermore, to study the effect of temperature on acyltransferase activity of the isolated strain, cells were grown at 50 °C for 20 h and harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 g followed by washing with 0.1 M PBS. The enzyme assay was carried out in the temperature range of 30–70 °C using whole-cell suspension. Subsequently, the effect of pH on the reaction mixture was determined by taking sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0–5.8), PBS (pH 5.8–8.0) and borate buffer (pH 8.0–9.2). After that, acyltransferase assay was also determined under similar conditions.

Stability of amidase

Cell pellet harvested after 20 h of bacterial growth was suspended in 0.1 M PBS and incubated at 50 °C in water bath. The samples were taken after every 6 h followed by acyltransferase activity analysis under standard assay conditions.

Effect of cell concentration and reaction time on BHA production

Cells were harvested after a growth period of 20 h and subjected to lyophilization. Lyophilized cells were stored at − 20 °C for further use. The effect of cell concentration on BHA production was determined using different concentration of lyophilized cells, i.e., 0.5 mg, 1 mg, 2 mg, 3 mg, 4 mg, and 5 mg/mL (final). Lyophilized cells (2 mg/mL) suspended in 0.1 M PBS were used to determine the optimum reaction time for BHA production. Acyltransferase reaction was carried out at 50 °C for a period of 3.5 h (210 min) with sampling at an interval of 30 min. The enzyme assay was performed under standard assay conditions.

Bench-scale production

A batch reaction for BHA production was carried out at a 150 mL scale under optimized conditions using 100 mM benzamide, 500 mM hydroxylamine (co-substrate), and 2 mg/mL lyophilized cells. The reaction was carried out at 50 °C for 180 min under shaking conditions in an incubator shaker. After that, the reaction mixture was extracted thrice with equal volume of ethyl acetate and dried under vacuum. Furthermore, the product formation was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) {Solvent system: methanol in 1% dichloromethane, flow rate-0.5 mL/min, columnC-18 at 60 °C}.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed to understand the statistical significance of collected data using Past 4.03 (Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis) and excel data analysis tool. All the parameters were tested with a 95% confidence level (alpha value as 0.05).

The relationship between reaction temperature and pH with the acyltransferase activity of the enzyme was determined by trend line analysis. Furthermore, co-relation analysis was carried out between acyltransferase activity and reaction time for elucidating the effect of reaction time on enzyme activity. It was also used to understand the effect of different cell concentrations and reaction time on BHA production. Finally, regression analysis was performed on the observed values to examine the role of substrate concentration on enzyme activity.

Results

Isolation, characterization, and identification of isolated strain

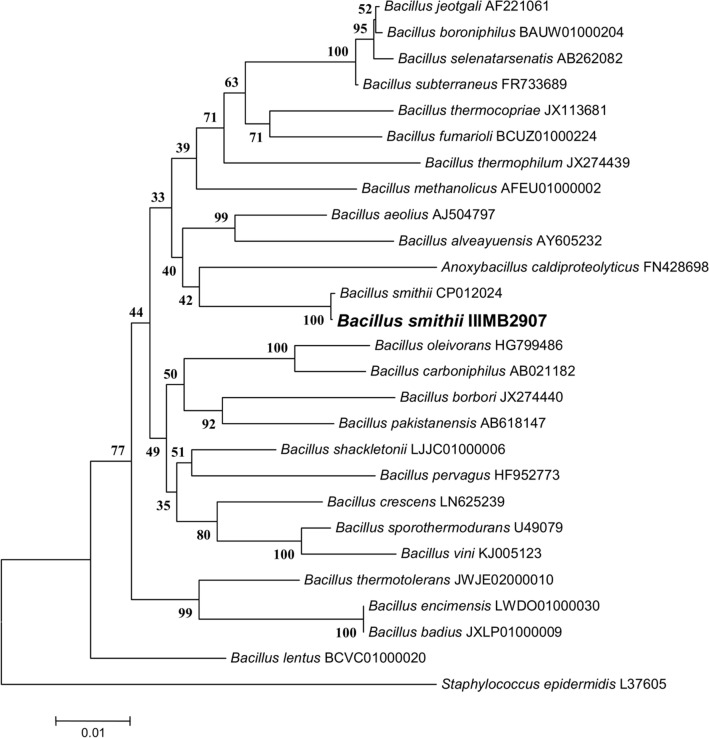

A total of 22 microorganisms were isolated from soil and water samples using enrichment media containing 20 mM benzamide as a nitrogen source. Among them, one bacterial isolate was identified from the soil sample that exhibited amide hydrolase activity and also showed acyltransferase activity with benzamide. The selected isolate was identified morphologically by examining its macroscopic and microscopic features. The bacterial strain formed pale yellow-colored colonies on MB agar plates. Based on the gram’s staining test, the isolate was identified as Gram positive due to the presence of rod-shaped, violet-colored colonies. Biochemical characterization revealed positive results toward citrate, methyl red, catalase, and oxidase (Table 1). In addition, molecular characterization was performed by amplifying 16 s rDNA region. BLAST analysis of the sequenced product exhibited 100% similarity with Bacillus smithii strain (Accession no. CP012024) and significant similarity with other Bacillus species. The identified sequence was also submitted to the GenBank database with accession no. KX509969. Furthermore, phylogenetic tree was constructed by neighbor-joining method (Fig. 1). The isolated strain was named Bacillus smithii (B. smithii) IIIMB2907.

Table 1.

Biochemical analysis of the amidase-producing strain Bacillus smithii IIIMB2907

| Biochemical test | Results |

|---|---|

| Growth on MacConkey agar media | − |

| Indole test | − |

| Methyl red test | + |

| Voges–Proskauer test | − |

| Citrate test | + |

| Casein test | − |

| Starch hydrolysis | − |

| Gelatin hydrolysis | − |

| Nitrate reduction | − |

| Catalase | + |

| Oxidase | + |

| Esculin hydrolysis | − |

| H2S gas production | − |

| Urease | − |

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree showing evolutionary relationship of Bacillus smithii IIIMB2907 with closely related strains based on the 16S rDNA sequences. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (500 replicates) are shown next to the branches. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7

Substrate specificity

Enzymes through evolution and adaptation are able to catalyze specific chemical transformations on specific type of substrates. However, some enzymes may also catalyze wide range of substrates, although their catalytic efficiency may not be same for structurally related substrates (Galmes et al. 2020). Among such enzymes, some amidases have reported broad substrate specificity toward aliphatic, aromatic, and heterocyclic amides (Xi et al. 2021).

In our study, amide hydrolase activity of the isolated culture was performed with various amides and significant activity was observed with aromatic amides (isonicotinamide, pyrizanamide, nicotinamide, and benzamide) and aliphatic amides (butyramide, acrylamide, propionamide, vaeramide, acetamide, isobutyramide, adipamide, methacrylamide, and succinamide) (Table 2). However, it was maximum for isonicotinamide (68.21 ± 1.36 U/mL). As isolated strain exhibited significant amide hydrolase activity with benzamide; hence, its acyltransferase activity was explored for the production of BHA at bench scale.

Table 2.

Substrate affinity of amidase from Bacillus smithii IIIMB2907 [enzyme assay conditions: substrate concentration: 20 mM reaction temperature: 50 °C, pH 7.0, and incubation time: 30 min]

| Substrates | ≈Solubility in water (mg/mL) | Structure | Activity (U/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide | 33.3 |

|

40.58 ± 2.03 |

| Acetamide | 2000 |

|

34.00 ± 1.70 |

| Benzamide | 13 |

|

33.67 ± 1.68 |

| Butyramide | 170 |

|

45.00 ± 2.25 |

| Nicotinamide | 100 |

|

65.63 ± 3.28 |

| Propionamide | 360 |

|

38.00 ± 1.90 |

| Adipamide | 4.4 |

|

29.38 ± 1.47 |

| Malonamide | 180 |

|

6.08 ± 0.30 |

| Succinamide | 3.30 |

|

11.54 ± 0.58 |

| Valeramide | 92 |

|

34.33 ± 1.72 |

| Pyrazinamide | 50 |

|

66.17 ± 3.31 |

| Isonicotinamide | 191 |

|

68.21 ± 3.41 |

| Isobutyramide | 225 |

|

30.17 ± 1.51 |

| Methacrylamide | 202 |

|

27.50 ± 1.38 |

Determination of thermophilic nature of B. smithii IIIMB2907

Based on the environmental adaptation, thermophilic microbes produce enzymes higher than the moderate temperature range (20–45 °C). Our results revealed that maximum enzyme production and cell growth were observed in MB medium incubated at 50 °C, whereas no cell growth was observed at 30 °C and 40 °C (Fig. 2), which confirms the thermophilic nature of the isolated bacteria. However, significant cell growth was observed at 60 °C, but there was no enzyme activity at this temperature.

Fig. 2.

Effect of temperature on amidase production (enzyme assay conditions: substrate—20 mM benzamide, co-substrate—0.5 M hydroxylamine—HCl, pH 7.0, and incubation time—30 min). Straight line indicates cell growth with error bars indicating standard deviation of the mean as all experiments were performed in triplicates and checkered box indicates enzyme activity (U/mL)

Effect of inducers

An inducer is a critical component in the medium as it is responsible for the enhancement of enzyme production and also acts as a nitrogen source in the MB medium. The maximum acyltransferase activity was observed with the cells grown in MB medium containing Ɛ-caprolactam as an inducer (Fig. 3). In decreasing trend, significant activity was observed with butyronitrile followed by benzonitrile, 2-cyanopyridine, propionamide, and propionitrile. Although, cell growth was also observed in MB media containing propionitrile followed by butyramide, propionamide, benzamide, and benzonitrile (with lesser activity), but no growth and activity were observed in control (without any nitrogen source), NH4Cl (without yeast), and media containing phenylacetonitrile.

Fig. 3.

Effect of different inducers on amidase production (enzyme assay conditions: substrate—20 mM benzamide, co-substrate—0.5 M hydroxylamine—HCl, pH 7.0, reaction temperature—50 °C, and incubation time—30 min). Straight line indicates cell growth with error bars indicating standard deviation of the mean as all experiments were performed in triplicates and boxes indicate enzyme activity (U/mL)

Effect of temperature and pH

Enzymatic and chemical reactions require a particular temperature and pH condition for maximum productivity. The maximum acyltransferase activity was observed in the reaction mixture incubated at 50 °C (Fig. 4a). The activity followed an increasing trend from 30 to 50 °C and further decreased at 60 °C. The cells exposed to 60 °C exhibited rapid acyltransferase activity loss. Trend line analysis of temperature profile followed a polynomial pattern, as data points showed a non-linear trend, with a regression value of 0.8096. The pattern formed thus confirmed the previous assumption wherein maximum enzyme production and cell growth were observed in MB media incubated at 50 °C.

Fig. 4.

Effect of acyltransferase activity of amidase from Bacillus sp. IIIMB2907 at different (a) temperature and (b) pH (enzyme assay conditions: substrate—20 mM benzamide, Co-substrate—0.5 M hydroxylamine-HCl, reaction temperature-50 °C, 2 mg/mL cell concentration, incubation time-30 min). Straight line indicates enzyme activity (U/mL) with error bars indicating standard deviation of the mean as all experiments were performed in triplicates

In pH analysis, it was observed that B. smithii IIIMB2907 was active over a wide range of pH (4.0–9.2). Maximum acyl transferase activity was observed in PBS of pH 7.0 (295 ± 14.75 U/mL) (Fig. 4b). However, the relative activities at pH 6.0 and 8.0 were 65% and 87% of the maximum activity, respectively, which decreased significantly above pH 8.0 and below pH 5.8. The data points obtained had regression values of 0.6548 (pH 4.0–6.0), 0.8681 (pH 6.0–8.0), and 0.9383 (pH 8.0–9.0), which were found to be statistically significant.

Effect of substrate concentration

Substrate concentration finds application in industries that relate substrate tolerance with productivity enhancement. However, higher substrate concentration sometimes results in inhibition of the enzyme. The effect of substrate concentration on acyltransferase activity was observed by enzyme assay performed under standard assay conditions using different substrate concentrations (1–100 mM). The results in Fig. 5 suggested that acyltransferase activity was initially maximum (213.25 U/mL) at 20 mM substrate concentration, but enzyme activity decreased marginally up to 100 mM benzamide concentration. Statistical analysis using regression on the measured values revealed significance of the data with a p value of 0.0033.

Fig. 5.

Effect of substrate concentration on acyltransferase activity of amidase (enzyme assay conditions: substrate, co-substrate—0.5 M hydroxylamine—HCl, pH 7.0, reaction temperature—50 °C, 2 mg/mL cell concentration, and incubation time—30 min). Straight line indicates enzyme activity (U/mL) with error bars indicating standard deviation of the mean as all experiments were performed in triplicates

Operational stability of amidase

The stability of amidase in whole cells of B. smithii IIIMB2907 was determined, as shown in Fig. 6. The curve was plotted between the natural logarithm of acyltransferase and time. The slope (0.0399) of the curve for the whole cell is represented by the value of "k" in the equation: t1/2 = 0.693/k. The half-life of the amidase was calculated to be 17.37 h that revealed high stability of the enzyme at 50 °C.

Fig. 6.

(a) Operational stability of amidase on incubation of cell suspension at 50 °C before the standard assay. (b) Plot between the natural logarithm of acyltransferase with respect to incubation time (enzyme assay conditions: substrate—20 mM benzamide, Co-substrate—0.5 M hydroxylamine—HCl, pH 7.0, reaction temperature—50 °C, 2 mg/mL cell concentration, and incubation time—30 min). Straight line indicates relative enzyme activity (%) with error bars indicating standard deviation of the mean as all experiments were performed in triplicates

Data analysis of the observed values demonstrated a negative correlation of − 0.97341 with a p value of 2.11648E-06, indicating an inverse relationship between incubation time and enzyme activity. So far, no other Bacillus strain has been reported for amidase production with such high stability. Therefore, these results are of industrial importance as enzyme stability is an important aspect that may find applications for pharmaceutically important biotransformation.

Effect of cell concentration and reaction time on BHA production

To assess the optimum biocatalyst concentration for acyltransferase activity, 0.5–5 mg/mL cell concentrations were added in reactions, and acyltransferase activity was analyzed. BHA production increased with the increase in cell concentration (Fig. 7) up to 5 mg/mL. Cell concentration had a positive correlation of 0.9982 with respect to the final product. As the amount of cells increased in the reaction mixture, enhancement in BHA production was also detected. The observed data points had a p value of 5.0233E-06, depicting their accuracy as the obtained p value is less than 0.05 (alpha-threshold). However, minimum cell concentration is required for biotransformation-based process development. Therefore, the effect of reaction time on the biotransformation process was studied using 2 mg/mL cells.

Fig. 7.

Effect of cell concentration on BHA production (enzyme assay conditions: substrate—20 mM benzamide, co-substrate—0.5 M hydroxylamine—HCl, pH 7.0, reaction temperature—50 °C, and incubation time—30 min). Checkered box indicates benzohydroxamic acid (mM) with error bars indicating standard deviation of the mean as all experiments were performed in triplicates

Maximum conversion (89% approx.) of benzamide to BHA was observed with 2 mg/mL cells after 180 min of incubation, after which there was a slight decrease in the conversion rate (Fig. 8). The trend line analysis showed a polynomial curve with a regression value of 0.9855 as BHA production was positively correlated (0.97577) with incubation time. The results revealed that as the incubation time of the reaction was increased, BHA production also increased till a certain point, after which it started to decline. Also, the regression analysis of the observed data was highly significant, as revealed by the p value of 0.0002.

Fig. 8.

Effect of incubation time on BHA production (enzyme assay conditions: substrate—20 mM benzamide, co-substrate—0.5 M hydroxylamine—HCl, pH 7.0, 2 mg/mL cell concentration, and reaction temperature—50 °C). Checkered box indicates benzohydroxamic acid (mM) with error bars indicating standard deviation of the mean as all experiments were performed in triplicates

Bench-scale production

In bench-scale production, light pinkish powder of BHA (89% w/w) was obtained after the processing of terminated reaction. The crude extract was then subjected to purification by column chromatography, in which 64% recovery of BHA was obtained with the purity of 96% (determined by HPLC).

Discussion

In the present study, an amidase-producing thermophilic bacterium was isolated from the soil collected from the bottom of a hot water spring. It was identified as B. smithii IIIMB2907 and was explored for its potential for the production of BHA, which is a pharmaceutically important hydroxamic acid. Subsequently, it was observed that it had amide hydrolase and acyltransferase activities similar to the earlier reported organisms. For instance, Agarwal and Choudhury (2014) reported the presence of both amide hydrolase and acyltransferase activity of two different enzymes with distinct substrate specificities extracted from B. smithii IITR6b2 named as acyltransferase A and acyltransferase B. Furthermore, with respect to amide hydrolase activity of the reported enzymes, acyltransferase B, which resembles the enzyme properties of our strain exhibited affinity with a broad spectrum of aliphatic, aromatic, and heterocyclic amides such as isonicotinamide, benzamide, nicotinamide, hexanamide, and butyramide. However, on comparison, only one amidase was present as observed in the total cell lysate of B. smithii IIIMB2907 in lane 1 (L1) of zymogram. Subsequently, the enzyme was partially purified, and the same band was found in lane 2 (L2) (Figure S1). To be more specific, amidase of B. smithii IIIMB2907 had strong affinity toward aromatic amides (isonicotinamide, pyrizanamide, nicotinamide, and benzamide) followed by aliphatic amides (butyramide, acrylamide, propionamide, vaeramide, acetamide, isobutyramide, adipamide, methacrylamide, and succinamide) which can be used for hydroaxmic acid production at higher scale under optimized conditions. Apart from this, the reported strain has also been used to produce acetohydroxamic acid (Singh et al. 2019).

The effect of temperature on growth and enzyme production of the isolated strain revealed that the culture could grow at temperatures higher than 50 °C, whereas its growth was suppressed at lower temperatures. Interestingly, even though it could grow at higher temperatures, enzyme production at and above 60 °C was negligible. Similarly, another strain, Geobacillus subterraneus RL-2a, reported in the literature could also grow and produce amidase initially at 50 °C (Mehta et al. 2016).

In addition to its temperature sensitivity, the culture showed no activity when grown in MB media containing ammonium chloride (with and without yeast extract). Subsequently, based on earlier reports, the culture was induced with different compounds to analyze their effect on enzyme production. It was found that Ɛ-caprolactam among other, showed maximum enzyme activity. This can be correlated with the fact that Ɛ-caprolactam is highly soluble in aqueous solutions, which enhances its absorptivity and utilization by whole cells, thus resulting in high enzyme induction and significant cell growth. Inducing the culture for enhanced enzyme activity has also been reported for amidase from B. smithii IITR6b2 where 10 mM phenyl acetonitrile in MB media was found to be the best inducer (Altschul et al. 1997). Similarly, Sharma et al. (2012) induced an amidase from thermophile Geobacillus pallidus BTP-5 × MTCC 9225 by addition of 0.3% formamide. Another study from Bhatia et al. (2013b) reported an amidase from thermophile Alcaligenes sp. MTCC 10,674, which could be induced with 0.4% isobutyronitrile. Hence, based on existing results and literature, inducing the culture for enzyme production might be essential.

Thermophilic enzymes are always of industrial significance as some of the substrates require higher temperatures for proper solubility and chances of contamination in culturing processes are low. Therefore, the enzyme (amidase) discussed here, because of its inherent thermophilic nature, could work efficiently at 50 °C which is similar to the amidase of Alcaligenes sp. MTCC 10,674 with almost complete inactivation at 70 °C (Bhatia et al. 2013a; Cha and Chambliss 2011).

From a commercial point of view, maximum acyltransferase activity at pH 7.0 is desirable for biotransformation reaction. The pH optima (7.0) for the amidase of B. smithii IIIM2907 was similar to the optimum pH of amidases from Geobacillus Pallidus RAPc8, and Rhodopseudomonas palustris (Guan et al. 2017; Suzuki and Ohta 2006). Furthermore, it is always desirable to have better enzyme stability for industrial applications. Here, in this study, the reported amidase has a half-life of 17.37 h at 50 °C, which is very high among the stability of reported thermophilic enzymes. Suzuki and Ohta (2006) studied the stability of the recombinant amidase from Sulfolobus tokodaii strain 7. They reported 100% activity after 2 h of incubation at 75 °C, pH 7.5 with benzamide as a substrate, and its activity gradually decreased at 80 °C with a half-life of about 45 min at 85 °C. Furthermore, high stability of amidase from Geobacillus pallidus RAPc8 with a half-life greater than 5 h was reported at 50 and 60 °C (Makhongela et al. 2007).

Furthermore, for a bio catalyzed reaction to be efficient, its conversion rate and recovery should be high. In our study, biotransformation of benzamide to BHA was carried out, wherein 64% BHA was recovered from batch reaction with 96% purity. Bhatia et al. (2013a) reported very high substrate (100 mM benzamide) and product (90 mM BHA) tolerance for amidase of Alcaligenes sp. MTCC 10,674 which is almost similar to the trend in the present study. They also reported maximum acyltransferase activity with 90% conversion of benzamide to BHA in 80 min using 4 mg/mL cell concentration, whereas in the present study, 89% BHA was produced using cell concentration of 2 mg/mL which is better than the earlier studies.

Conclusion

In the present study, we have explored thermophilic amidase from B. smithii IIIMB2907 to produce BHA, which is otherwise chemically synthesized and is pharmaceutically important hydroxamic acid. In the current research, 64% of purified BHA was recovered after biotransformation. In addition to that, the enzyme has good operational stability, i.e., a half-life of 17.37 h at 50 °C, which is relatively high when compared to the existing literature. Similar enzymes have been reported from other strains with different substrate specificities; however, few reports are available utilizing amidase for BHA production. Hence, the results obtained in the current study showed an industrial potential in developing an efficient biocatalytic reaction process for BHA production.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Fig S1. Zymogram of (L1) Total cell lysate and; (L2) Partially purified amidase (Brown colour band indicating amidase of Bacillus sp. IIIMB2907) (TIFF 1118 KB)

Funding

The authors are thankful for the financial assistance from the Science and Engineering Research Board, Department of Science and Technology, Government of India (Grant no-SB/YS/LS-15/2014 and LAB Projects (MLP 1003 MLP1008). A Fellowship grant by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) to Hitesh Sharma is also acknowledged. In addition, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) is also appreciated for the fellowship grant of Ananta Ganjoo (Letter no. 5/3/8/ITR-F/2020 Dated: 28/02/2020). IIIM communication no. CSIR-IIIM/IPR/00129, Dated: 11/27/2019.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this work.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

References

- Agarwal S, Choudhury B. Presence of multiple acyltransferases with diverse substrate specificity in Bacillus smithii strain IITR6b2 and characterization of unique acyltransferase with nicotinamide. J Mol Catal B Enzymatic. 2014;107:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2014.05.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu V, Choudhury B. Methods of cell lysis and effect of detergents for the recovery of nitrile metabolizing enzyme from Amycolatopsis sp. IITR215. J Gen Engg Biotechnol. 2013;11:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jgeb.2013.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babu V, Shilpi, Choudhury B. Nitrile-metabolizing potential of Amycolatopsis sp. IITR215. Process Biochem. 2010;45:866–873. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2010.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand S, Helesbeux JJ, Larcher G. Hydroxamate, a key pharmacophore exhibiting a wide range of biological activities. Mini-Rev Med Chem. 2013;13:1311–1326. doi: 10.2174/13895575113139990007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla TC, Kumar V, Kumar V, Thakur N, Savitri Nitrile metabolizing enzymes in biocatalysis and biotransformation. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2018;185:925–946. doi: 10.1007/s12010-018-2705-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia RK, Bhatia SK, Mehta PK. Bench scale production of benzohydroxamic acid using acyl transfer activity of amidase from Alcaligenes sp. MTCC 10674. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;40:21–27. doi: 10.1007/s10295-012-1206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia SK, Mehta PK, Bhatia RK. An isobutyronitrile-induced bienzymatic system of Alcaligenes sp. MTCC 10674 and its application in the synthesis of α-hydroxyisobutyric acid. Bioprocess Biosys Eng. 2013;36:613–625. doi: 10.1007/s00449-012-0817-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha M, Chambliss GH. Characterization of acrylamidase isolated from a newly isolated acrylamide-utilizing bacterium, Ralstonia eutropha AUM-01. Curr Microbiol. 2011;62:671–678. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9761-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhagat S, Jujjavarapu S. Isolation of a novel thermophilic bacterium capable of producing high-yield bioemulsifier and its kinetic modelling aspects along with proposed metabolic pathway. Braz J Microbiol. 2020;51:135–143. doi: 10.1007/s42770-020-00228-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournand D, Bigey F, Arnaud A. Acyl transfer activity of an amidase from Rhodococcus sp. strain R312: formation of a wide range of hydroxamic acids. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2844–2852. doi: 10.1128/AEM.64.8.2844-2852.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmes MA, García-Junceda E, Swiderek K, Moliner V. Exploring the origin of amidase substrate promiscuity in CALB by a computational approach. ACS Catal. 2020;10:1938–1946. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b04002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Cj, Ji Yj, Hu Jl, et al. Biotransformation of rutin using crude enzyme from Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Curr Microbiol. 2017;74:431–436. doi: 10.1007/s00284-017-1204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari P, Chand D. Immobilization of whole resting cell of Bacillus sp. APB-6 exhibiting amido-transferase activity on sodium alginate beads and its comparative study with whole resting cells. J Innov Pharm Biol Sci. 2017;4:121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Makhongela HS, Glowacka AE, Agarkar VB. A novel thermostable nitrilase superfamily amidase from Geobacillus pallidus showing acyl transfer activity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;75:801–811. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0883-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PK, Bhatia SK, Bhatia RK, Bhalla TC. Enhanced production of thermostable amidase from Geobacillus subterraneus RL-2a MTCC 11502 via optimization of physicochemical parameters using Taguchi DOE methodology. 3 Biotech. 2016;6:66. doi: 10.1007/s13205-016-0390-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey D, Patel SKS, Singh R, Kumar P, Thakur V, Chand D. Solvent-tolerant acyltransferase from Bacillussp. APB-6: purification and characterization. Indian J Microbiol. 2019;59:500–507. doi: 10.1007/s12088-019-00836-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan L, Zheng R, Zheng Y. A novel amidase from Brevibacterium epidermidis ZJB-07021: gene cloning, refolding and application in butyrylhydroxamic acid synthesis. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;43:1071–1083. doi: 10.1007/s10295-016-1786-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Sharma NN, Bhalla TC. Biotransformation of acetamide to acetohydroxamic acid at bench scale using acyl transferase activity of amidase of Geobacillus pallidus BTP-5x MTCC 9225. Indian J Microbiol. 2012;52:76–82. doi: 10.1007/s12088-011-0211-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma H, Singh RV, Raina C, Babu V. Amide hydrolyzing potential of amidase from halotolerant bacterium Brevibacteriumsp. IIIMB2706. Biocatal Biotransfor. 2018;37:59–65. doi: 10.1080/10242422.2018.1494733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Sharma H, Koul A, Babu V. Exploring a broad spectrum nitrilase from moderately halophilic bacterium Halomonas sp. IIIMB2797 isolated from saline lake. J Basic Microbiol. 2018;58:867–874. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201800168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RV, Sharma H, Gupta P, Kumar A, Babu V. Green synthesis of acetohydroxamic acid by thermophilic amidase of Bacillus smithii IIIMB2907. Indian J Biochem Bio. 2019;56:373–377. [Google Scholar]

- Sogani M, Mathur N, Bhatnagar P. Biotransformation of amide using Bacillussp.: isolation strategy, strain characteristics and enzyme immobilization. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2012;9:119–127. doi: 10.1007/s13762-011-0005-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Ohta H. Identification of a thermostable and enantioselective amidase from the thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus tokodaii strain 7. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;45:368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi L, Tan W, Li J, Qu J, Liu J. Cloning and characterization of a novel thermostable amidase, Xam, from Xinfangfangia sp. DLY26. Biotech Lett. 2021;43:1395–1402. doi: 10.1007/s10529-021-03124-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig S1. Zymogram of (L1) Total cell lysate and; (L2) Partially purified amidase (Brown colour band indicating amidase of Bacillus sp. IIIMB2907) (TIFF 1118 KB)

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.