Abstract

Intrinsic circadian clocks are present in all forms of photosensitive life, enabling daily anticipation of the light/dark cycle and separation of energy storage and utilization cycles on a 24-hr timescale. The core mechanism underlying circadian rhythmicity involves a cell-autonomous transcription/translation feedback loop that in turn drives rhythmic organismal physiology. In mammals, genetic studies have established that the core clock plays an essential role in maintaining metabolic health through actions within both brain pacemaker neurons and peripheral tissues and that disruption of the clock contributes to disease. Peripheral clocks, in turn, can be entrained by metabolic cues. In this review, we focus on the role of the nucleotide NAD(P)(H) and NAD+-dependent sirtuin deacetylases as integrators of circadian and metabolic cycles, as well as the implications for this interrelationship in healthful aging.

Keywords: Circadian clock, metabolism, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), sirtuins, aging

1. Introduction: Transcriptional and metabolic circadian oscillators

1.1. A transcription/translation feedback loop drives 24-hr periodic behavioral and physiological rhythms

Circadian clocks (from circa diem, about a day) are found in all photosensitive organisms where they drive the temporal organization of a wide variety of behavioral and physiological functions in ~24-hr cycles. In the early 18th century, Jean-Jacques d’Ortous de Mairan first demonstrated that daily leaf movements in the Mimosa plant were self-sustained under constant darkness. The principal criteria defining circadian processes were later delineated by Jurgen Aschoff and Colin Pittendrigh in the mid-20th century, including: (i) the persistence of an ~24-hr rhythm in the absence of external zeitgebers (i.e., under constant conditions); (ii) the ability to be entrained by environmental cues; and (iii) constant period length across a wide range of environmental temperatures (i.e., temperature compensation).

A transformation in understanding the molecular basis of the circadian clock came in 1971, when Benzer and Konopka identified three alleles of the same gene that altered 24-hr eclosion and locomotor patterns in Drosophila melanogaster in the absence of external zeitgebers using deliberate mutagenesis [1]. In 1984, these mutants were positionally cloned to the locus encoding the period (PER) gene [2-5]. Chemical mutagenesis in mice ultimately led to the discovery of the first mammalian circadian gene, circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (CLOCK) [6]. Both CLOCK and PER belong to the basic helix-loop-helix period-ARNT-single minded (bHLH-PAS) superfamily. CLOCK heterodimerizes with Brain and Muscle ARNT-Like 1 (BMAL1), also a bHLH-PAS transcription factor (TF). CLOCK/BMAL1 activate transcription of target genes containing E-boxes, including the period (PER1, PER2, PER3) and cryptochrome (CRY1, CRY2) repressors, which in turn feedback to inhibit CLOCK/BMAL1 in an ~24-hr cycle [7] (see Figure 1). In addition to Pers and Crys, CLOCK/BMAL1 activate transcription of genes encoding the orphan nuclear receptors ROR and REV-ERB, which generate reinforcing feedback loops [7]. Cell-autonomous expression of factors in this transcription-translation feedback loop (TTFL) drives 24-hr rhythms in nearly all mammalian cells and tissues [8,9].

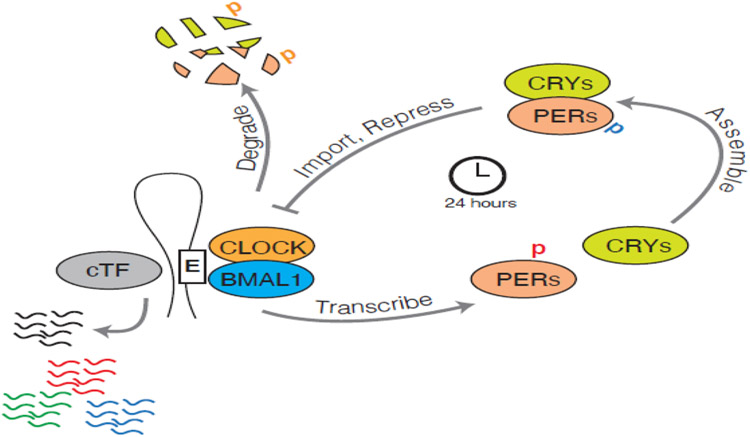

Figure 1: Molecular clock mechanism.

Core clock transcriptional activators, CLOCK and BMAL1, heterodimerize and drive the expression of the repressor period (Per) and cryptochrome (Cry) genes by binding to E-box elements (E) within their promoters. Cytoplasmic sequestration of the repressor proteins occurs through assembly of the cytoplasmic repressor complex. Nuclear import of PERs and CRYs in the early dark period triggers inhibition of CLOCK/BMAL1 activity. Degradation of PERs and CRYs allows the 24-hr cycle to begin anew. CLOCK/BMAL1 bind at diverse and tissue-specific enhancers defined by lineage-specific TFs. Phase-specific CLOCK/BMAL1 binding drives long-range chromosome interactions and remodels nucleosome positioning at promoters of target genes through co-recruitment of numerous epigenetic enzymes. Collaborative TFs (cTF) then bind to these newly opened DNA regulatory elements and drive nascent transcription in multiple phases of the circadian cycle. The recruitment of clock factors to tissue-specific enhancers and the involvement of tissue-specific cTFs help tune the oscillatory transcriptional program for each organ.

1.2. Early evolution of a transcription-independent metabolic oscillator

Although genetic studies have established a heritable basis for circadian rhythms, a surprise finding has been that 24-hr oscillations can also persist in the absence of transcription, first demonstrated in the green algae Acetabularia. For example, oxygenic respiration in Acetabularia persists with a ~24-hr periodicity even in enucleated cells [10]. Similarly, circadian rhythms of photosynthesis persist in Acetabularia in the presence of actinomycin D (a RNA Polymerase II inhibitor that blocks transcription) and chloramphenicol (a ribosome inhibitor that blocks translation) [11].

More recently, hyperoxidation of a reactive cysteine on the peroxiredoxin (PRX) antioxidant protein was found to rhythmically accumulate in anucleate red blood cells, suggesting that metabolic circadian oscillation in the absence of transcription can also occur in higher eukaryotes [12]. PRX oxidation rhythms were also shown to be entrainable to the external environment and constant across a wide temperature gradient, fulfilling the Pittendrigh hallmarks of “circadian” processes [12]. Finally, PRX oxidation rhythms persist in the presence of pharmacological inhibitors of transcription and translation [13]. These experiments suggested that metabolic oscillations can exist in the absence of a transcriptional oscillator.

Interestingly, circadian rhythms of oxidation of PRX homologs have been observed across all three kingdoms of life [14]. In contrast, the low level of homology between transcriptional clocks in mammals, Synechococcus, and Arabidopsis suggests that the transcriptional clock machinery has evolved independently in different kingdoms of life [15]. While the aforementioned studies in eubacteria and red blood cells revealed that some metabolic oscillators can act independently of transcription, the following sections detail the universal interdependence of metabolic and transcriptional rhythms.

2. Crosstalk Between Circadian and Metabolic Pathways

2.1. A forward direction of circadian transcription controlling metabolism

Evidence for transcriptional control of metabolic rhythms was demonstrated by nuclear transplantation studies in Acetabularia, revealing that photosynthetic rhythms follow the endogenous cycle of the donor nucleus transferred into an organism with a different period length of oscillation [16]. PRX oxidation rhythms, as discussed above, are also regulated by the transcriptional core clock network across species [12,14]. In animals, the strongest evidence that the clock drives metabolic and physiological rhythms came with analyses using experimental genetic mouse models of circadian disruption. For example, whole-body Clock mutant mice have defects not only in behavioral rhythms, but they also develop diet-induced obesity, hyperleptinemia, hepatic steatosis, hypoinsulinemia, and metabolic syndrome [17]. These mice also display increased activity and feeding during the light period when mice are typically inactive and fasting [17]. Further, the finding of hypoinsulinemia, rather than hyperinsulemia, paired with obesity-induced diabetes, suggested concurrent pancreatic β-cell failure. Indeed, subsequent conditional ablation of Bmal1 within the endocrine pancreas confirmed profound hypoinsulinemic hyperglycemia, revealing an essential role of peripheral tissue clocks in normal physiology, particularly in the postprandial state [18]. In contrast, tissue-specific ablation of Bmal1 in hepatocytes leads to hypoglycemia in fasted mice [19,20], while Cry deletion in liver leads to hyperglycemia with enhanced gluconeogenesis in response to glucagon and glucocorticoid [21,22]. Further, muscle-specific Bmal1-deficient mice display reduced glucose uptake and metabolism [23]. Studies of the clock network in brain further indicate time-of-day-specific effects on post-prandial and fasting metabolism. For example, Bmal1 ablation within the hypothalamus and within AgRP/NPY-expressing leptin-sensitive cells leads to altered day-night food consumption rhythms and elevated endogenous hepatic glucose production [24,25]. Together, these genetic studies suggest a role for tissue-specific clocks in metabolic homeostasis.

2.2. Clock TTFL generates tissue-specific transcriptional oscillations

CLOCK/BMAL1 heterodimers promote transcription of Per and Cry genes by binding to E-box elements within their regulatory regions [26,27]. E-boxes are also present within the regulatory regions of many genes, accounting for rhythmic oscillation of the transcriptome across tissues [9,28,29]. An intriguing finding has been that ~10% of genes within any given tissue exhibit 24-hr oscillations, yet the subset of genes that oscillate within each tissue are largely unique, while the few RNAs that oscillate in multiple tissues do so in the same phase throughout the body [28]. ChIP-sequencing (ChIP-seq) experiments in liver revealed that the core clock components bind at nearly 50,000 locations across the genome [29], with surprisingly only 1,444 sites shared amongst all of the clock proteins. Whereas the binding sites of CLOCK and BMAL1 significantly overlapped, CRY1, CRY2, and PER2 bound to unique locations throughout the genome. Analysis of DNA motifs at clock protein binding sites revealed the canonical E-box motif, as expected, as well as the D-box motif, the nuclear receptor binding motif, and a number of motifs associated with tissue-specific TFs [29]. Interestingly, ~80% of clock factor binding sites were within intronic or intergenic enhancers [29], with transcription promoted from these sites in liver [30]. Comparison of CLOCK/BMAL1 enhancer cistromes in pancreatic β cells and liver revealed that the distribution of CLOCK/BMAL1 throughout the genome is determined by the unique chromatin landscape of the tissue [31]. Clock TFs also participate in the formation of long-range chromatin interactions across the circadian timeframe that link distal enhancers to the promoters of rhythmically-controlled genes [32-34]. The rhythmic expression of metabolic genes arises due to three-dimensional chromatin looping approximating core clock and tissue-specific collaborative factors.

How might the core clock TFs promote long-range chromatin interactions? The core clock factors themselves do not contain histone-modifying activity, but are instead part of multi-protein clock-activator and -repressor complexes [35-37]. These complexes contain epigenetic enzymes such as: (i) the transcriptional coactivator and acetyltransferase P300/CBP [38]; (ii) methyltransferases associated with heterochromatin, EZH2 [39] and gene activation MLL1/MLL3 [40,41]; (iii) the demethylase JARID1a [42]; (iv) the deacetylases HDAC3 [43] and SIRT1 [44-47]; and (v) the nucleosome remodeler and deacetylase (NuRD) complex [37]. Recruitment of epigenetic enzymes and TFs are thought to facilitate enhancer/promoter interactions at rhythmically-expressed genes.

Studies of enhancer RNA expression have shown that rhythmic transcription in liver occurs across many phases of the 24-hr cycle, whereas core clock proteins bind only within limited times each day [9,28-30,48]. In silico analyses of rhythmically-expressed genes and enhancer RNAs has led to the identification of tissue-specific TFs that collaborate with core clock factors, including the E26-transformation specific (ETS) and heat shock (HSF) TFs [30,49,50]. In addition to recruitment of epigenetic enzymes and collaborative TFs, post-transcriptional processes have also been shown to drive rhythmic cell physiology, including RNA-processing, translation, and protein ubiquitination/degradation [29,51-53].

2.3. Transcriptional control of NAD+ by the clock

One of the transcripts exhibiting the most robust rhythmic expression across diverse tissues encodes the rate-limiting enzyme in NAD+ biosynthesis (i.e., nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase, NAMPT) [54,55]. The demand for daily NAD+ biosynthesis is high due to its rapid turnover, having a half-life of ~3-10 hrs [56]. The NAD+ salvage pathway underlies ~70% of the daily biosynthesis of NAD+ in liver and up to ~95% in other tissues [57]. Rhythmic expression of Nampt has been observed across numerous tissues in-phase with Per2 expression [48], producing 24-hr oscillations in NAD+ with a zenith in the early dark period (ZT16) (~ 4 hrs following the zenith of Nampt) and a nadir in the early light period (~ZT4) in mouse liver [20,44,54,55]. 24-hr oscillations in NAD+ have also been detected both in vitro and in liver, soleus muscle, and adipose tissues [20,55]. NAD+ rhythms have not been experimentally quantified in intact human tissue, but are predicted to peak in the early morning following the daily zenith in Nampt and Per2 gene expression in human skeletal muscle [58]. Genetic ablation of the clock activator Bmal1 in MEFs decreases total cellular concentration of NAD+, whereas ablation of the clock repressors Cry1 and Cry2 increases NAD+ [55]. 24-hr oscillations in NAD+ in turn drive activity of the major NAD+-dependent deacetylase in the mitochondria, SIRT3. NAD+ oscillations also parallel daily cycles of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and oxygen consumption in liver and skeletal muscle cells [20]. Further, pharmacologic supplementation of the NAD+ precursor nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) restores SIRT3 activity and mitochondrial oxygen consumption in Bmal1 mutant cells [20]. While these studies demonstrate clock control of NAD+ biosynthesis, the relationship between clocks and metabolism is not unidirectional, and sections 3.2 and 3.3 below detail how changes in metabolism and NAD+ can reciprocally impact clock function.

3. Reciprocal metabolic signaling to the clock

3.1. Post-translational regulation of the circadian clock

Although the periodicity of the Earth’s rotation on its axis is nearly 24-hr, mice exhibit a shorter period length, whereas humans exhibit a somewhat longer cycle [59,60]. Phase alignment of internal rhythmic processes with the external light-dark cycle involves “entrainment” of internal clocks through time-givers (“zeitgebers”) [61]. In animals, phase alignment involves the master circadian clock located within the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) that receives direct innervation by intrinsically-photosensitive retinal ganglionic cells (ipRGCs) [62]. Recent discovery that opsin photoreceptors are expressed in skin cells raises the possibility that other cell types may also be entrained to light [63-67]. Heat can also entrain the circadian cycle in peripheral tissues [50,68]. Identification of heat shock response elements (HSE) in the Per2 promoter revealed a direct link between temperature and clock control [69]. Glucocorticoid receptor also regulates Per1 expression in peripheral tissues in a ligand-dependent manner [70]. Thus, numerous entrainment mechanisms align internal rhythms with the environmental light/dark cycle.

Post-translational regulation of core clock TFs also impacts molecular and metabolic rhythms. An early clue came with identification of the gene responsible for the Tau-mutant golden hamster phenotype (a short period length and elevated metabolic rate) as casein kinase (CK1) [71,72]. Mutant alleles of the Drosophila homolog of CK1, Doubletime (Dbt), were also shown to affect rhythmic behavior in flies [73]. Genetic complementation experiments showed that the PER-S mutation, originally identified by Konopka and Benzer in 1971, reduces DBT-dependent phosphorylation of PER [74,75]. Subsequent analyses have identified a myriad of phosphorylation events within every component of the clock, with PER having more than 30 phosphorylated sites [76]. Generation of phospho-mimetic and -null mutants of many of these sites in Drosophila has led to the identification of numerous roles for post-translational modifications of PER in the recruitment of E3-ubiquitin ligases, temperature compensation, degradation rates, activity, complex formation, and subcellular trafficking [77-79]. These studies demonstrate that post-translational modification is critical in circadian homeostasis.

Post-translational regulation has also been shown to underlie circadian variants in human families. Linkage studies of Familial Advanced Sleep Phase Syndrome (FASPS), which is characterized by extremely early bedtime and awaking, provided the first entry point into identifying genes underlying sleep-wake rhythms in humans. Mapping of a single nucleotide polymorphism tied to the sleep phenotype within a family with FASPS identified a serine-to-glycine polymorphism on PER2 that abrogates response to CK1 [80]. Subsequent studies in additional families identified distinct variants that map to other clock genes and contribute to either Advanced Sleep Phase (ASP) or Delayed Sleep Phase (DSP) syndrome in humans [81]. PER2 phosphorylation is also tied to metabolism through serine modification involving O-GlcNAcylation [82]. How cell metabolism influences the post-translational modification of PER2 will be reviewed in the next sections.

3.2. The core molecular clock senses energy availability within cells

Whereas genetic studies demonstrate that clock TFs are necessary for metabolic homeostasis, mounting evidence suggests that molecular clocks within peripheral tissues are also sensitive to changes in metabolic milieu. For example, mice provided high-fat diet (HFD) demonstrate atypical 24-hr behavioral patterns with increased wheel-running activity and food intake during the light period, in addition to disrupted core clock gene expression in peripheral tissues, especially within adipocytes [83]. Moreover, HFD leads to genome-wide reprogramming, with surprising de novo oscillating transcripts, loss of previously rhythmic transcripts, and phase-shifts in rhythmic transcripts in liver [84]. HFD also leads to remodeling within distal regulatory enhancers through pathways involving de novo oscillation of the lipogenic TF sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 (SREBP1) and the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha (PPARα) [85]. In addition to studies of calorie-dense diets, rhythmic gene expression patterns also change under low-energy states induced by caloric restriction and ketogenic diet, although the mechanisms that mediate these changes remain incompletely understood [86-89].

Consideration of feeding time is also important for metabolic health. Mice provided HFD exclusively during the rest (light) period gain significantly more weight than animals provided isocaloric HFD only during the dark period – the active period in mice [90]. Further, the metabolic phenotypes arising from ad lib HFD feeding can be significantly ameliorated by restricting the time of high-fat feeding to the dark (active) period [91]. Human studies also support the importance of meal timing on metabolic health [92]. Together, these data suggest that feeding during the time of day in which the animal is normally awake is critical for maintaining metabolic health.

A variety of signals may transmit information regarding the nutrient status of the cell to the circadian clock. Many metabolic endocrine hormones, such as insulin, ghrelin, and leptin, are rhythmically-expressed, can alter clock function, and are influenced by altered nutrient conditions [93]. Glucocorticoid administration can inhibit the food-induced phase-shifting of peripheral clocks [94]. Body temperature likewise displays 24-hr variation, is affected by the nutrient milieu, and regulates HSF1 binding to the Per2 promoter [50,68,95-97]. Altered feeding schedules also impact peripheral clocks in a tissue-specific manner, with the molecular clock network in liver entraining most rapidly to changes in the nutrient milieu [98]. While body temperature and activity rhythms shift in response to changes in food availability in wild-type mice, they do not in mice with liver-specific ablation of Per2 [99]. It is currently unknown how the liver clock transmits changes in nutrient state to affect body temperature and behavior, but clock control of ketones [99], glucose [19], fatty acids [19,20], and methionine [100,101] in the liver may alter circadian cycles across multiple tissues.

Finally, numerous cell-autonomous metabolic signaling pathways within peripheral tissues may communicate changes in nutrient availability or content to the molecular clock. For example, the NAD+-dependent Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase 1 (PARP1) is regulated by feeding and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ates CLOCK, as well as other target proteins involved in DNA damage response, differentiation, and metabolism [102,103]. PARP1 regulates the ability of mice to entrain to alternative feeding cycles, although the mechanism that stimulates PARP1 activity under these conditions is unknown [103]. Further, glucose- and glutamine-derived O-GlcNAc modifications of PER2 compete with phosphorylation by casein kinase and link glucose availability to activity of the core clock [82]. Finally, interplay between phosphorylases and nutrient-sensitive kinases affect clock function [104,105]. Temperature, metabolic hormones, and glucose availability thus contribute to entrainment of the molecular clock. The next section reviews emerging evidence for nucleotide cycles and sirtuin deacetylases as an additional layer in the regulation of clock activity.

3.3. Reciprocal metabolic regulation of the circadian clock through NAD(P)(H) signaling

Recent studies have highlighted a role for the sirtuin family of NAD+-dependent deacetylases in the bidirectional feedback between energy state and circadian rhythms. Sirtuins are conserved nutrient-sensing deacetylases that catalyze the transfer of acetyl moieties from lysines on histones and other target proteins to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), generating nicotinamide (NAM) and O-acetyl ADP-ribose, in addition to the deacetylated lysine [106]. The first clue that SIRT1 might be linked to the circadian clock came with studies that showed that SIRT1 interacts with the clock activator complex CLOCK/BMAL1 and is rhythmically recruited to the promoter of Nampt, the rate-limiting enzyme in the NAD+ salvage pathway [54,55]. As NAD+ biosynthesis is driven by the molecular clock (described in section 2.3 above), these findings revealed a feedback loop involving clock-driven oscillations of Nampt expression and NAD+ in turn controlling SIRT1 and CLOCK/BMAL1 activity. As discussed below, the decline in NAD+ levels during aging may contribute to attenuation in sleep/wake cycles across the lifespan (see section 4.2).

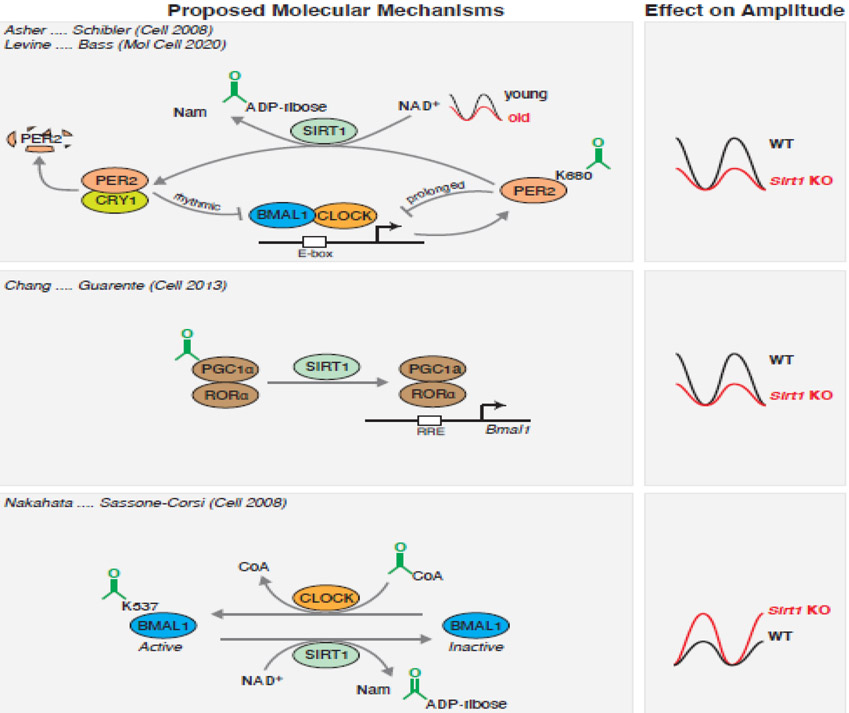

Mechanistically, SIRT1 controls clock activity by regulating PER2 acetylation. Loss of SIRT1 in MEFs and liver increased PER2 acetylation and stability and decreased the amplitude of clock rhythms [45]. Subsequent studies identified the specific site of NAD+/SIRT1-induced PER2 deacetylation at lysine 680, which led to enhanced PER2 stability and repressive activity, yet reduced heterodimerization with CRY1 within the nucleus [44]. Of note, PER2K680 falls within a domain containing a casein kinase recognition site that is mutated in Familial Advanced Sleep Phase Syndrome (FASPS) in humans and the PER-S phosphorylation site that alters circadian behavior in flies [44]. Reduced expression or activity of NAMPT altered PER2 phosphorylation and advanced the phase of activity offset in wheel-running behavior in mice, similar to the behavior observed in animals harboring FASPS or PER-S mutations [44]. In addition to PER2, SIRT1 has been suggested to regulate the clock through deacetylation of BMAL1. Loss of Sirt1 in MEFs increased BMAL1 acetylation and expression of its target genes [47]. Sirt1 knockout also increased PGC1α acetylation in neurons, which decreased the amplitude of clock oscillations through interactions with RORα [46] (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Proposed molecular mechanisms underlying SIRT1-mediated regulation of the core clock.

Summary of proposed mechanisms and consequences of SIRT1-mediated NAD+-dependent deacetylation on clock amplitude from indicated papers. Sirt1 knockout or decline in NAD+ with age decreases clock amplitude by increasing K680 acetylation and stability of PER2 (top). Loss of SIRT1 has also been described to prevent PGC1α co-activation of Bmal1 expression (middle). In contrast, Sirt1 knockout also has been proposed to increase clock amplitude by enabling persistent CLOCK-dependent acetylation of BMAL1 on K537 (bottom). Citations associated with each finding are indicated.

In addition to regulating the activity of the core clock components, SIRT1 also contributes to rhythmic transcription by regulating the activity of FOXO1 and PPARα, which drive nutrient-sensitive transcription [107,108]. Indeed, pharmacologic or genetic modulation of NAD+ or SIRT1 causes transcriptional reprogramming of ~50% of the genes that display 24-hr variation in liver [44,109]. Unbiased promoter motif analysis further revealed that most of these reprogrammed genes contain binding sites for non-clock SIRT1-target TFs, such as HSF1 [44]. Interestingly, NR increased HSF1 recruitment to promoters of phase-shifted genes only in wild-type mice but not in clock-defective Bmal1 knockout mice [44]. These results suggest that the rhythmic transcription arises from collaborative interactions between clock and other TF targets of SIRT1.

A remaining question has been whether SIRT1 or NAD+ are responsible for the transcriptional and behavioral reprogramming observed during high fat diet feeding and other dietary states. For example, ad lib wild-type mice display two daily peaks of NAD+ in liver, whereas fasted mice have a single peak [20,44,55]. NAD+ levels may vary according to oscillation in availability of its dietary precursors tryptophan, nicotinic acid, and nicotinamide riboside [110]. Light sensed by opsins in adipocytes may also contribute to NAD+ homeostasis [63].

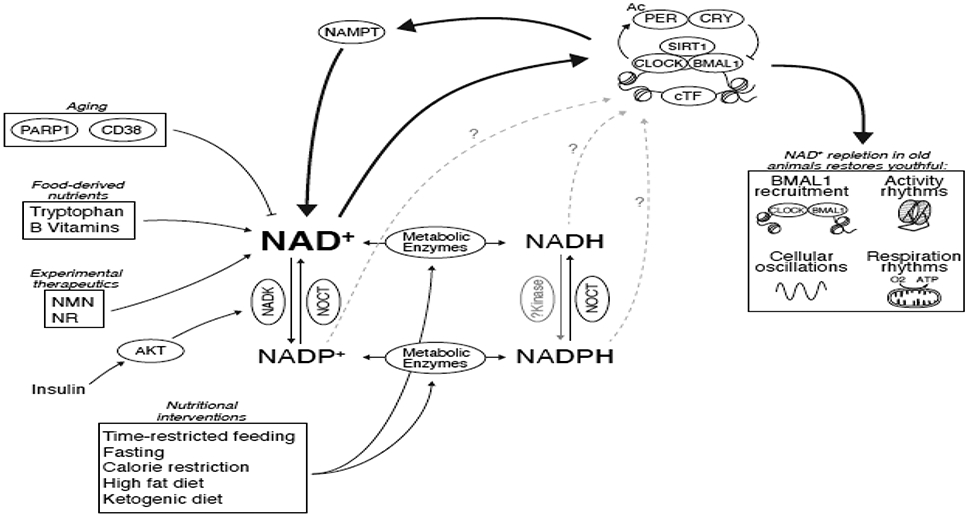

NAD+ levels are also affected by diet indirectly through reductive/oxidative enzymes that interconvert NAD+ with NADH. The activity of NAD(H) redox enzymes within glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, the TCA cycle, the electron transport chain, and fatty acid oxidation varies according to dietary state, in turn affecting NAD(H) balance (Figure 3). Further, flux through these pathways exhibits both cell autonomous circadian- and nutrient-dependent oscillations [111]. Indeed, during glucose limitation (caloric restriction, “CR”) in yeast, NAD+ levels increase while NADH decreases [112]. In contrast, in mammals, CR leads to tissue-specific alterations in NAD(H) balance, as NADH increases in liver and adipose, but is unchanged in muscle [113]. Prolonged fasting has also been shown to increase NADH and decrease NAD+ in mouse liver [114]. Surprisingly, high-fat feeding in mice decreased the NAD+/NADH ratio in liver, underscoring the diverse metabolic pathways that contribute to NAD(H) homeostasis [115]. A challenge remains in understanding the interdependence of circadian and nutrient signals as determinants of NAD(H) balance [86].

Figure 3: NAD(P)(H) at the nexus of metabolism, circadian rhythms, and aging.

Circadian control of Nampt and nutrients derived from feeding/fasting cycles drive 24-hr oscillations in NAD+ levels. Conversion between NAD+ and NADP+ is mediated by insulin-sensitive or mitochondrially-localized proteins. Oxidation/reduction reactions in metabolic pathways convert NAD(P)+ to NAD(P)H and are influenced by dietary nutrient content and timing. While NAD+ feeds back to control circadian transcriptional cycles through SIRT1, potential contributions of the other nicotinamide-containing nucleotides remain unknown. Aging decreases NAD+ as a result of increased PARP1 activity that is stimulated by DNA-damage and through increased expression of the CD38 NAD+-hydrolase. Decline in NAD+ during aging can be counteracted by supplementation of experimental therapeutic precursors, nicotinamide riboside (NR) and nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN). In old mice, NAD+ repletion rescues defects in BMAL1 chromatin recruitment, transcriptional oscillations, rhythmic respiration, and evening locomotor activity in old mice [44].

While NADH levels are influenced by diet in mammals, how NADH influences mammalian sirtuin activity remains uncertain. In yeast, NADH has been reported to be a competitive inhibitor of ySir2p and its closest mammalian ortholog human SIRT1, increasing the KM 3-fold without affecting Vmax when NADH was 250 μM and 300 μM, respectively [112]. However, another study concluded that NADH was a poor inhibitor of sirtuins, with NADH inhibiting ySir2p (IC50 = 15 mM) and the yeast Homolog of Sir2 (HST2, an NAD+-dependent deacetylase with closest homology to human SIRT2) (IC50 = 28 mM) at concentrations significantly higher than reported NADH levels in yeast (300-800 μM) [112,116,117]. They reported similar IC50 values for human SIRT2 (IC50 = 11 mM) [117], which were also significantly higher than the reported range of 50-400 μM NADH observed in mammalian muscle, kidney, liver, and brain [118]. While these studies used similar assays to measure sirtuin activity (i.e., deacetylation of radiolabeled acetyl-histone substrates), reaction conditions differed, such as concentrations of salts, metals, and NAD+, and different histone substrates were used, which may impact KM for NAD+ and Ki or NADH [119,120]. A third study attempted to systematically interrogate the differences in NADH sensitivity across a range of techniques, but generated contradictory results depending on the assay used [121]. Thus, uncertainty remains not only as to whether mammalian sirtuins are inhibited by physiologically-relevant concentrations of NADH in vitro, but also whether there are conditions in vivo where NADH may regulate sirtuin activity and downstream clock function.

The phosphorylated form of NAD(H), NADP(H), is involved in detoxification of reactive oxygen species and in macromolecule biosynthesis. NADP(H) levels may also contribute to circadian rhythmicity. The DNA binding capacity of bHLH-PAS heterodimers (which includes the core-clock heterodimers CLOCK/BMAL1 and NPAS2/BMAL1) was altered by NAD(P)(H) in vitro [122]. Specifically, the reduced form of the two nicotinamide-containing redox factors, NADPH and NADH, enhanced the ability of bHLH-PAS heterodimers (CLOCK/BMAL1, NPAS2/BMAL1, CLOCK/ARNT1, NPAS2/ARNT1) to bind to short DNA oligonucleotides by in vitro EMSA [122]. While these studies were conducted in vitro, there is evidence that the phosphorylated nucleotides may also be important in clock function in vivo. NAD(P)H oscillations have been detected in anucleate red blood cells where PRX oxidation rhythms persist independent of transcription [12]. Genetic deletion or siRNA-mediated knockdown of PRX isoforms in Neurospora or Synechococcus (which could disrupt NAD(P)H rhythms) altered the transcriptional phase and amplitude of oscillation, respectively, but not period length [14]. An intriguing recent finding has been that Nocturnin (Noct), a robustly-oscillating transcript [123], possesses NADP(H) phosphatase activity, converting NADPH to NADH and NADP+ to NAD+ in the mitochondria [124,125]. Conversely, NADK, the enzyme that converts NAD+ to NADP+, is affected by AKT activity in response to nutrient availability [126]. As changes in nutrient flux impact NADP(H) levels, it is intriguing to speculate that the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated pools of nucleotide cofactors exhibit both time-of-day and nutrient-dependent variation.

3.4. Metabolic redox state and circadian control of cell cycle

Elucidating the interdependence of nucleotide metabolism with the circadian clock may have implications in the context of cell cycle regulation and cancer cell metabolism. For example, the circadian clock gates the transition from both the G1 to S and the G2 to M phases [8,127] by driving the expression and activity of the cell cycle regulators Wee1/Cyclin-B1, p16-Ink4a, p21, and Chk2 [128-131]. In mouse keratinocytes, the clock aligns the S phase with the dark period, thus reducing exposure to UV-induced genotoxic stress [132]. A broad range of studies have further implicated each of the core clock factors in the coupling of cell cycle and proliferation [133-136].

An intriguing hypothesis for why the circadian clock and the cell cycle might be linked is that clock control of the cell cycle may help maintain genome integrity by temporally separating periods of DNA replication from the peak time-of-day of oxidative stress. Studies in animals may ultimately support observations in yeast, which indicate alignment of metabolic and cell division cycles. The cell autonomous metabolic cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (termed a “Yeast Metabolic Cycle”, YMC) [137] has been shown to exhibit a periodicity of approximately 5 hours depending on the concentration of glucose in the media. Further analyses suggest that distinct “sub” phases of the YMC (oxidative, reductive/building, and reductive/charging) correspond with distinct transcriptional programs. Expression of cell cycle regulators during the reductive/building phase tightly constrains the cell division cycle with the YMC and restricts DNA replication to the reductive phase of the YMC. Treatment with reactive oxygen species in turn phase-shifts the YMC. Mutants that allow DNA replication during the oxidative phase of the YMC demonstrate a higher rate of DNA damage and mutations [138]. Thus, coupling of redox oscillations to cell cycle may help preserve genome integrity by separating the time when DNA is most sensitive to oxidative genotoxic stress. Whether alignment of reductive and oxidative phases of cell metabolism with cell cycle might protect animal cells from cancer remains an area of open inquiry.

4. Metabolism of NAD+ as a Factor in Circadian Aging

4.1. Circadian decline during aging

Aging is associated with a decline in the robustness of circadian rhythmicity at the behavioral, physiological, and biochemical levels. Elderly individuals are prone to wake early in the morning and go to bed early, similar to patterns associated with syndromic FASPS [139-141]. Aging is also associated with increased daytime napping, sleep fragmentation and reduced sleep duration, and shorter bouts of REM sleep [139]. Sleep and circadian disruption have also been implicated in the increased incidence of metabolic disorders with aging [142,143]. Similar to the advanced sleep pattern associated with aging in humans, old-age mice also exhibit an earlier phase of offset of daily wheel-running behavior, leading to a phase advance in activity rhythms compared with younger mice [44]. At the cellular level, both central and peripheral molecular oscillators become desynchronized and display dampened amplitude with aging in mice [44,144]. Genome-wide rhythmic transcription is also reprogrammed in liver and muscle stem cells of old mice, with a significant decrease in the number of genes that peak during the night, consistent with dampened circadian amplitudes with age [88]. Thus, deterioration of behavioral and molecular rhythms is a feature of aging in both humans and mice.

A question that arises is whether deterioration of the clock with age actively contributes to diseases of aging or is instead simply a byproduct of aging. Evidence supporting a causative role for clock deregulation in aging is the finding that genetic abrogation of Bmal1 in mice shortens lifespan and causes premature aging [145]. The idea that circadian misalignment may contribute to aging disorders was originally proposed by Pittendrigh, who observed that fruit flies maintained in atypical day lengths (21 or 26 hrs) had shorter life spans than flies maintained on a 24-hr day length [146]. Further, period-mutant Drosophila maintained in atypical day lengths that corresponded to their endogenous periods displayed longer lives than those housed in standard day lengths [147]. An interesting finding was that Tau mutant hamsters, which have hypomorphic CK1ε activity and short period length, live longer than controls when maintained in a standard 24-hr day length [148]. In sum, the robustness of the clock and resonance between the internal molecular timekeeper and the external environment are important for promoting health span.

4.2. Circadian decline and metabolic aging linked through NAD+

As reviewed above, a well-characterized mechanism linking circadian and metabolic aging involves the NAD+-SIRT1 pathway (see section 3.3). Sirtuins were originally identified for their role in lifespan extension during caloric restriction (CR) [149], as deletion of the yeast homolog of SIRT1, ySIR2p, or NPT1, an enzyme in the NAD+ biosynthetic pathway, abrogated the increased replicative lifespan observed during CR [150]. Numerous studies have demonstrated reduced NAD+ levels during aging and decreased activity of NAD+-dependent epigenetic enzymes, including the sirtuins [151-156]. While the cause of the decline in NAD+ with age is not completely understood, possible mechanisms include consumption of NAD+ by PARPs as the result of accumulating genotoxic stress throughout life [157], the increased expression of the NAD+ hydrolase CD38 in late life [152], and/or the decreased expression of Nampt with age due to either clock-dependent or -independent mechanisms [54,55,156].

Discovery of small-molecule activators of sirtuins (sirtuin-activating compounds, “STACs”) may ultimately open a therapeutic pathway to intervene in circadian disorders of aging. For example, allosteric activators of the sirtuins have been identified [158]; however, the assay used to identify sirtuin activators has been questioned [159,160]. A second strategy to augment sirtuin function has been to pharmacologically boost NAD+ levels. Attempts to raise NAD+ levels with niacin (nicotinic acid, NA) caused flushing at low doses and was not well-tolerated in humans [161]. Nicotinamide (NAM), a precursor for the NAD+ salvage enzyme NAMPT, is also frequently utilized to elevate NAD+, although the direct impact of NAM on SIRT1 is difficult to interpret because it is unclear whether effects are through increased NAMPT activity or reduced NAD+ consumption as a result of NAM-mediated inhibition of the PARP and SIRT enzymes themselves [117,162]. More recent efforts have utilized well-tolerated, orally-bioavailable precursors of NAD+, including nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) and nicotinamide riboside (NR), which both elevate NAD+ and activate NAD+-dependent enzymes without changing NAM across tissues [163].

Use of NR to elevate NAD+ in old-age mice revealed that the age-associated decline in NAD+ is responsible for the decreased amplitude of molecular, behavioral, and metabolic circadian rhythms [44]. Old mice with low NAD+ levels display increased PER2, dampened rhythms of BMAL1 chromatin recruitment and activity, reduced amplitude of oxidative respiration in liver mitochondria, and an early phase of offset of wheel running behavior. Strikingly, NR supplementation in old mice leads to youthful levels of NAD+, PER2, rhythms of BMAL1 chromatin recruitment and activity, and late-night activity rhythms [44] (see Figure 3). Overexpression of SIRT1 in the brain also counteracted behavioral changes from aging [46]. Thus, the age-associated decline in NAD+ levels and SIRT1 activity plays a role in circadian decline with aging.

Changes in NAD+ during aging have also been shown to contribute to reduced insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion, glaucoma, neurodegenerative disease and movement disorders, reduced vascular function, and longevity [163]. In particular, a recent study showed that elevation of NAD+ through supplementation of NMN improves measures of insulin signaling in prediabetic women [164], though a gap remains in our understanding of the effects of NAD+ supplementation on aging and circadian measures in humans. On a mechanistic level, NAD+ repletion during aging restores SIRT1 and SIRT3 activity, contributing to stress response pathways important in health [163]. Finally, a decline in NAD+ during aging has also been shown to limit efficient DNA damage repair [165]. Together, these studies demonstrate that NAD+ repletion may counter aging through mechanisms involving enhanced clock function.

5. Conclusions

The past several decades have witnessed a transformation in our understanding of biological clocks, with an early focus on identifying components of the molecular clock and metabolic processes that exhibit circadian variation. However, the bridge between understanding the molecular underpinnings of the clock with clinical studies remains less well established. The identification of both the nucleotide NAD(P)(H) and NAD+-dependent sirtuin deacetylases opens new avenues for understanding how changes in redox cycles in different nutrient states may impact whole-body energetics. For example, the circadian control of the phosphorylation state of NAD+ by nocturnin and insulin signaling may represent one node to intervene in circadian metabolism [124]. An exciting additional arena for future research will be to probe how circadian decay throughout life contributes to aging disease and to expand such studies towards new therapeutics to improve health.

Acknowledgements:

We thank all members of the Bass laboratory for helpful discussions.

Funding:

Research support was from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grants R01DK090625, R01DK100814, and 1R01DK113011-01A1, the Chicago Biomedical Consortium S-007, and the National Institute on Aging (NIA) grant P01AG011412 (to J.B.).

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Works Cited:

- [1].KONOPKA RJ, BENZER S, Clock mutants of Drosophila melanogaster., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 68 (1971) 2112–2116. 10.1073/pnas.68.9.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bargiello TA, Young MW, Molecular genetics of a biological clock in Drosophila., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 81 (1984) 2142–2146. 10.1073/pnas.81.7.2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bargiello TA, Jackson FR, Young MW, Restoration of circadian behavioural rhythms by gene transfer in Drosophila., Nature. 312 (1984) 752–754. 10.1038/312752a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Reddy P, Zehring WA, Wheeler DA, Pirrotta V, Hadfield C, Hall JC, Rosbash M, Molecular analysis of the period locus in Drosophila melanogaster and identification of a transcript involved in biological rhythms., Cell. 38 (1984) 701–710. 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zehring WA, Wheeler DA, Reddy P, KONOPKA RJ, Kyriacou CP, Rosbash M, Hall JC, P-element transformation with period locus DNA restores rhythmicity to mutant, arrhythmic Drosophila melanogaster., Cell. 39 (1984) 369–376. 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Vitaterna MH, King DP, Chang AM, Kornhauser JM, Lowrey PL, McDonald JD, Dove WF, Pinto LH, Turek FW, Takahashi JS, Mutagenesis and mapping of a mouse gene, Clock, essential for circadian behavior., Science. 264 (1994) 719–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bass J, Lazar MA, Circadian time signatures of fitness and disease., Science. 354 (2016) 994–999. 10.1126/science.aah4965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nagoshi E, Saini C, Bauer C, Laroche T, Naef F, Schibler U, Circadian Gene Expression in Individual Fibroblasts Cell-Autonomous and Self-Sustained Oscillators Pass Time to Daughter Cells, Cell. 119 (2004) 693–705. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zhang R, Lahens NF, Ballance HI, Hughes ME, Hogenesch JB, A circadian gene expression atlas in mammals: Implications for biology and medicine., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. (2014) 201408886. 10.1073/pnas.1408886111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sweeney BM, Haxo FT, Persistence of a Photosynthetic Rhythm in Enucleated Acetabularia., Science. 134 (1961) 1361–1363. 10.1126/science.134.3487.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sweeney BM, Tuffli CF, Rubin RH, The circadian rhythm in photosynthesis in Acetabularia in the presence of actinomycin D, puromycin, and chloramphenicol., The Journal of General Physiology. 50 (1967) 647–659. 10.1085/jgp.50.3.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].O’Neill JS, Reddy AB, Circadian clocks in human red blood cells., Nature. 469 (2011) 498–503. 10.1038/nature09702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].O’Neill JS, van Ooijen G, Dixon LE, Troein C, Corellou F, Bouget F-Y, Reddy AB, Millar AJ, Circadian rhythms persist without transcription in a eukaryote., Nature. 469 (2011) 554–558. 10.1038/nature09654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Edgar RS, Green EW, Zhao Y, van Ooijen G, Olmedo M, Qin X, Xu Y, Pan M, Valekunja UK, Feeney KA, Maywood ES, Hastings MH, Baliga NS, Merrow M, Millar AJ, Johnson CH, Kyriacou CP, O’Neill JS, Reddy AB, Peroxiredoxins are conserved markers of circadian rhythms., Nature. 485 (2012) 459–464. 10.1038/nature11088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rosbash M, The implications of multiple circadian clock origins., PLOS Biology. 7 (2009) e62. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Schweiger E, Wallraff HG, Schweiger HG, Endogenous Circadian Rhythm in Cytoplasm of Acetabularia: Influence of the Nucleus., Science. 146 (1964) 658–659. 10.1126/science.146.3644.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Turek F, Joshu C, Kohsaka A, Lin E, Ivanova G, McDearmon E, Laposky A, Losee-Olson S, Easton A, Jensen D, Eckel R, Takahashi JS, Bass J, Obesity and metabolic syndrome in circadian Clock mutant mice, Science. 308 (2005) 1043–1045. 10.1126/science.1108750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Marcheva B, Ramsey KM, Buhr ED, Kobayashi Y, Su H, Ko CH, Ivanova G, Omura C, Mo S, Vitaterna MH, Lopez JP, Philipson LH, Bradfield CA, Crosby SD, JeBailey L, Wang X, Takahashi JS, Bass J, Disruption of the clock components CLOCK and BMAL1 leads to hypoinsulinaemia and diabetes, Nature. 466 (2010) 627–631. 10.1038/nature09253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lamia KA, Storch K-F, Weitz CJ, Physiological significance of a peripheral tissue circadian clock., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (2008) 15172–15177. 10.1073/pnas.0806717105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Peek CB, Affinati AH, Ramsey KM, Kuo H-Y, Yu W, Sena LA, Ilkayeva O, Marcheva B, Kobayashi Y, Omura C, Levine DC, Bacsik DJ, Gius D, Newgard CB, Goetzman E, Chandel NS, Denu JM, Mrksich M, Bass J, Circadian Clock NAD+ Cycle Drives Mitochondrial Oxidative Metabolism in Mice., Science. 342 (2013) 1243417. 10.1126/science.1243417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lamia KA, Papp SJ, Yu RT, Barish GD, Uhlenhaut NH, Jonker JW, Downes M, Evans RM, Cryptochromes mediate rhythmic repression of the glucocorticoid receptor., Nature. 480 (2011) 552–556. 10.1038/nature10700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhang EE, Liu Y, Dentin R, Pongsawakul PY, Liu AC, Hirota T, Nusinow DA, Sun X, Landais S, Kodama Y, Brenner DA, Montminy M, Kay SA, Cryptochrome mediates circadian regulation of cAMP signaling and hepatic gluconeogenesis., Nature Medicine. 16 (2010) 1152–1156. 10.1038/nm.2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dyar KA, Ciciliot S, Wright LE, Biensø RS, Tagliazucchi GM, Patel VR, Forcato M, Paz MIP, Gudiksen A, Solagna F, Albiero M, Moretti I, Eckel-Mahan KL, Baldi P, Sassone-Corsi P, Rizzuto R, Bicciato S, Pilegaard H, Blaauw B, Schiaffino S, Muscle insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism are controlled by the intrinsic muscle clock., Molecular Metabolism. 3 (2014) 29–41. 10.1016/j.molmet.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cedernaes J, Waldeck N, Bass J, Neurogenetic basis for circadian regulation of metabolism by the hypothalamus., Genes & Development. 33 (2019) 1136–1158. 10.1101/gad.328633.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cedernaes J, Huang W, Ramsey KM, Waldeck N, Cheng L, Marcheva B, Omura C, Kobayashi Y, Peek CB, Levine DC, Dhir R, Awatramani R, Bradfield CA, Wang XA, Takahashi JS, Mokadem M, Ahima RS, Bass J, Transcriptional Basis for Rhythmic Control of Hunger and Metabolism within the AgRP Neuron., Cell Metabolism. 29 (2019) 1078–1091.e5. 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hao H, Allen DL, Hardin PE, A circadian enhancer mediates PER-dependent mRNA cycling in Drosophila melanogaster., Molecular and Cellular Biology. 17 (1997) 3687–3693. 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yoo S-H, Ko CH, Lowrey PL, Buhr ED, Song E, Chang S, Yoo OJ, Yamazaki S, Lee C, Takahashi JS, A noncanonical E-box enhancer drives mouse Period2 circadian oscillations in vivo., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (2005) 2608–2613. 10.1073/pnas.0409763102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mure LS, Le HD, Benegiamo G, Chang MW, Rios L, Jillani N, Ngotho M, Kariuki T, Dkhissi-Benyahya O, Cooper HM, Panda S, Diurnal transcriptome atlas of a primate across major neural and peripheral tissues., Science. 22 (2018) eaao0318. 10.1126/science.aao0318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Koike N, Yoo S-H, Huang H-C, Kumar V, Lee C, Kim T-K, Takahashi JS, Transcriptional architecture and chromatin landscape of the core circadian clock in mammals., Science. 338 (2012) 349–354. 10.1126/science.1226339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fang B, Everett LJ, Jager J, Briggs E, Armour SM, Feng D, Roy A, Gerhart-Hines Z, Sun Z, Lazar MA, Circadian enhancers coordinate multiple phases of rhythmic gene transcription in vivo., Cell. 159 (2014) 1140–1152. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Perelis M, Marcheva B, Ramsey KM, Schipma MJ, Hutchison AL, Taguchi A, Peek CB, Hong H, Huang W, Omura C, Allred AL, Bradfield CA, Dinner AR, Barish GD, Bass J, Pancreatic β cell enhancers regulate rhythmic transcription of genes controlling insulin secretion., Science. 350 (2015) aac4250–aac4250. 10.1126/science.aac4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kim YH, Marhon SA, Zhang Y, Steger DJ, Won K-J, Lazar MA, Rev-erbα dynamically modulates chromatin looping to control circadian gene transcription., Science. 359 (2018) 1274–1277. 10.1126/science.aao6891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Aguilar-Arnal L, Hakim O, Patel VR, Baldi P, Hager GL, Sassone-Corsi P, Cycles in spatial and temporal chromosomal organization driven by the circadian clock., Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 20 (2013) 1206–1213. 10.1038/nsmb.2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Menet JS, Pescatore S, Rosbash M, CLOCK:BMAL1 is a pioneer-like transcription factor., Genes & Development. 28 (2014) 8–13. 10.1101/gad.228536.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Aryal RP, Kwak PB, Tamayo AG, Gebert M, Chiu P-L, Walz T, Weitz CJ, Macromolecular Assemblies of the Mammalian Circadian Clock., Molecular Cell. 67 (2017) 770–782.e6. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Brown SA, Ripperger J, Kadener S, Fleury-Olela F, Vilbois F, Rosbash M, Schibler U, PERIOD1-associated proteins modulate the negative limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator., Science. 308 (2005) 693–696. 10.1126/science.1107373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kim JY, Kwak PB, Weitz CJ, Specificity in circadian clock feedback from targeted reconstitution of the NuRD corepressor., Molecular Cell. 56 (2014) 738–748. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Etchegaray J-P, Lee C, Wade PA, Reppert SM, Rhythmic histone acetylation underlies transcription in the mammalian circadian clock., Nature. 421 (2003) 177–182. 10.1038/nature01314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Etchegaray J-P, Yang X, DeBruyne JP, Peters AHFM, Weaver DR, Jenuwein T, Reppert SM, The polycomb group protein EZH2 is required for mammalian circadian clock function., Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (2006) 21209–21215. 10.1074/jbc.m603722200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Valekunja UK, Edgar RS, Oklejewicz M, van der Horst GTJ, O’Neill JS, Tamanini F, Turner DJ, Reddy AB, Histone methyltransferase MLL3 contributes to genome-scale circadian transcription., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. (2013). 10.1073/pnas.1214168110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Katada S, Sassone-Corsi P, The histone methyltransferase MLL1 permits the oscillation of circadian gene expression., Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 17 (2010) 1414–1421. 10.1038/nsmb.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].DiTacchio L, Le HD, Vollmers C, Hatori M, Witcher M, Secombe J, Panda S, Histone lysine demethylase JARID1a activates CLOCK-BMAL1 and influences the circadian clock., Science. 333 (2011) 1881–1885. 10.1126/science.1206022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Alenghat T, Meyers K, Mullican SE, Leitner K, Adeniji-Adele A, Avila J, Bućan M, Ahima RS, Kaestner KH, Lazar MA, Nuclear receptor corepressor and histone deacetylase 3 govern circadian metabolic physiology., Nature. 456 (2008) 997–1000. 10.1038/nature07541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Levine DC, Hong H, Weidemann BJ, Ramsey KM, Affinati AH, Schmidt MS, Cedernaes J, Omura C, Braun R, Lee C, Brenner C, Peek CB, Bass J, NAD+ Controls Circadian Reprogramming through PER2 Nuclear Translocation to Counter Aging., Molecular Cell. 78 (2020) 835–849.e7. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Asher G, Gatfield D, Stratmann M, Reinke H, Dibner C, Kreppel F, Mostoslavsky R, Alt FW, Schibler U, SIRT1 regulates circadian clock gene expression through PER2 deacetylation., Cell. 134 (2008) 317–328. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chang H-C, Guarente L, SIRT1 Mediates Central Circadian Control in the SCN by a Mechanism that Decays with Aging, Cell. 153 (2013) 1448–1460. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Nakahata Y, Kaluzova M, Grimaldi B, Sahar S, Hirayama J, Chen D, Guarente LP, Sassone-Corsi P, The NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1 modulates CLOCK-mediated chromatin remodeling and circadian control., Cell. 134 (2008) 329–340. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Storch K-F, Lipan O, Leykin I, Viswanathan N, Davis FC, Wong WH, Weitz CJ, Extensive and divergent circadian gene expression in liver and heart., Nature. 417 (2002) 78–83. 10.1038/nature744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Ciarleglio CM, Resuehr HES, Axley JC, Deneris ES, McMahon DG, Pet-1 deficiency alters the circadian clock and its temporal organization of behavior., PloS One. 9 (2014) e97412. 10.1371/journal.pone.0097412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Reinke H, Saini C, Fleury-Olela F, Dibner C, Benjamin IJ, Schibler U, Differential display of DNA-binding proteins reveals heat-shock factor 1 as a circadian transcription factor., Genes & Development. 22 (2008) 331–345. 10.1101/gad.453808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Rizzini L, Levine DC, Perelis M, Bass J, Peek CB, Pagano M, Cryptochromes-Mediated Inhibition of the CRL4Cop1-Complex Assembly Defines an Evolutionary Conserved Signaling Mechanism., Current Biology : CB. 29 (2019) 1954–1962.e4. 10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Marcheva B, Perelis M, Weidemann BJ, Taguchi A, Lin H, Omura C, Kobayashi Y, Newman MV, Wyatt EJ, McNally EM, Fox JEM, Hong H, Shankar A, Wheeler EC, Ramsey KM, MacDonald PE, Yeo GW, Bass J, A role for alternative splicing in circadian control of exocytosis and glucose homeostasis, Gene Dev. 34 (2020) 1089–1105. 10.1101/gad.338178.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Atger F, Gobet C, Marquis J, Martin E, Wang J, Weger B, Lefebvre G, Descombes P, Naef F, Gachon F, Circadian and feeding rhythms differentially affect rhythmic mRNA transcription and translation in mouse liver., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (2015) E6579–88. 10.1073/pnas.1515308112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Nakahata Y, Sahar S, Astarita G, Kaluzova M, Sassone-Corsi P, Circadian control of the NAD+ salvage pathway by CLOCK-SIRT1., Science. 324 (2009) 654–657. 10.1126/science.1170803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Ramsey KM, Yoshino J, Brace CS, Abrassart D, Kobayashi Y, Marcheva B, Hong H-K, Chong JL, Buhr ED, Lee C, Takahashi JS, Imai S-I, Bass J, Circadian clock feedback cycle through NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis., Science. 324 (2009) 651–654. 10.1126/science.1171641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Ijichi H, Ichiyama A, Hayaishi O, Studies on the biosynthesis of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. 3. Comparative in vivo studies on nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, and quinolinic acid as precursors of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide., Journal of Biological Chemistry. 241 (1966) 3701–3707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Liu L, Su X, Quinn WJ, Hui S, Krukenberg K, Frederick DW, Redpath P, Zhan L, Chellappa K, White E, Migaud M, Mitchison TJ, Baur JA, Rabinowitz JD, Quantitative Analysis of NAD Synthesis-Breakdown Fluxes., Cell Metabolism. 27 (2018) 1067–1080.e5. 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Perrin L, Loizides-Mangold U, Chanon S, Gobet C, Hulo N, Isenegger L, Weger BD, Migliavacca E, Charpagne A, Betts JA, Walhin J-P, Templeman I, Stokes K, Thompson D, Tsintzas K, Robert M, Howald C, Riezman H, Feige JN, Karagounis LG, Johnston JD, Dermitzakis ET, Gachon F, Lefai E, Dibner C, Transcriptomic analyses reveal rhythmic and CLOCK-driven pathways in human skeletal muscle, Elife. 7 (2018) e34114. 10.7554/elife.34114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Czeisler CA, Duffy JF, Shanahan TL, Brown EN, Mitchell JF, Rimmer DW, Ronda JM, Silva EJ, Allan JS, Emens JS, Dijk D-J, Kronauer RE, Stability, precision, and near-24-hour period of the human circadian pacemaker., Science. 284 (1999) 2177–2181. 10.1126/science.284.5423.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Schwartz WJ, Zimmerman P, Circadian timekeeping in BALB/c and C57BL/6 inbred mouse strains., Journal of Neuroscience. 10 (1990) 3685–3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Pittendrigh CS, Circadian rhythms and the circadian organization of living systems., Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 25 (1960) 159–184. 10.1101/sqb.1960.025.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Berson DM, Dunn FA, Takao M, Phototransduction by retinal ganglion cells that set the circadian clock., Science. 295 (2002) 1070–1073. 10.1126/science.1067262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Nayak G, Zhang KX, Vemaraju S, Odaka Y, Buhr ED, Holt-Jones A, Kernodle S, Smith AN, Upton BA, D’Souza S, Zhan JJ, Diaz N, Nguyen M-T, Mukherjee R, Gordon SA, Wu G, Schmidt R, Mei X, Petts NT, Batie M, Rao S, Hogenesch JB, Nakamura T, Sweeney A, Seeley RJ, Gelder RNV, Sanchez-Gurmaches J, Lang RA, Adaptive Thermogenesis in Mice Is Enhanced by Opsin 3-Dependent Adipocyte Light Sensing, Cell Reports. 30 (2020) 672–686.e8. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Sato M, Tsuji T, Yang K, Ren X, Dreyfuss JM, Huang TL, Wang C-H, Shamsi F, Leiria LO, Lynes MD, Yau K-W, Tseng Y-H, Cell-autonomous light sensitivity via Opsin3 regulates fuel utilization in brown adipocytes, Plos Biol. 18 (2020) e3000630. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Upton BA, Díaz NM, Gordon SA, Gelder RNV, Buhr ED, Lang RA, Evolutionary Constraint on Visual and Nonvisual Mammalian Opsins, J Biol Rhythm. 36 (2021) 109–126. 10.1177/0748730421999870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Buhr ED, Vemaraju S, Diaz N, Lang RA, Gelder RNV, Neuropsin (OPN5) Mediates Local Light-Dependent Induction of Circadian Clock Genes and Circadian Photoentrainment in Exposed Murine Skin, Curr Biol. 29 (2019) 3478–3487.e4. 10.1016/j.cub.2019.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Zhang KX, D’Souza S, Upton BA, Kernodle S, Vemaraju S, Nayak G, Gaitonde KD, Holt AL, Linne CD, Smith AN, Petts NT, Batie M, Mukherjee R, Tiwari D, Buhr ED, Gelder RNV, Gross C, Sweeney A, Sanchez-Gurmaches J, Seeley RJ, Lang RA, Violet-light suppression of thermogenesis by opsin 5 hypothalamic neurons, Nature. 585 (2020) 420–425. 10.1038/s41586-020-2683-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Buhr ED, Yoo S-H, Takahashi JS, Temperature as a universal resetting cue for mammalian circadian oscillators., Science. 330 (2010) 379–385. 10.1126/science.1195262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Tamaru T, Hattori M, Honda K, Benjamin I, Ozawa T, Takamatsu K, Synchronization of circadian Per2 rhythms and HSF1-BMAL1:CLOCK interaction in mouse fibroblasts after short-term heat shock pulse., PloS One. 6 (2011) e24521. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Balsalobre A, Brown SA, Marcacci L, Tronche F, Kellendonk C, Reichardt HM, Schütz G, Schibler U, Resetting of circadian time in peripheral tissues by glucocorticoid signaling., Science. 289 (2000) 2344–2347. 10.1126/science.289.5488.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Lowrey PL, Shimomura K, Antoch MP, Yamazaki S, Zemenides PD, Ralph MR, Menaker M, Takahashi JS, Positional syntenic cloning and functional characterization of the mammalian circadian mutation tau., Science. 288 (2000) 483–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Ralph MR, Menaker M, A mutation of the circadian system in golden hamsters., Science. 241 (1988) 1225–1227. 10.1126/science.3413487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Price JL, Blau J, Rothenfluh A, Abodeely M, Kloss B, Young MW, double-time is a novel Drosophila clock gene that regulates PERIOD protein accumulation., Cell. 94 (1998) 83–95. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Rothenfluh A, Abodeely M, Young MW, Short-period mutations of per affect a double-time-dependent step in the Drosophila circadian clock, Current Biology. 10 (2000) 1399–1402. 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00786-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Kivimäe S, Saez L, Young MW, Activating PER repressor through a DBT-directed phosphorylation switch., PLOS Biology. 6 (2008) e183. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Vanselow K, Vanselow JT, Westermark PO, Reischl S, Maier B, Korte T, Herrmann A, Herzel H, Schlosser A, Kramer A, Differential effects of PER2 phosphorylation: molecular basis for the human familial advanced sleep phase syndrome (FASPS)., Genes & Development. 20 (2006) 2660–2672. 10.1101/gad.397006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Gallego M, Virshup DM, Post-translational modifications regulate the ticking of the circadian clock., Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 8 (2007) 139–148. 10.1038/nrm2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Ko HW, Jiang J, Edery I, Role for Slimb in the degradation of Drosophila Period protein phosphorylated by Doubletime., Nature. 420 (2002) 673–678. 10.1038/nature01272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Zhou M, Kim JK, Eng GWL, Forger DB, Virshup DM, A Period2 Phosphoswitch Regulates and Temperature Compensates Circadian Period., Molecular Cell. 60 (2015) 77–88. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Toh KL, Jones CR, He Y, Eide EJ, Hinz WA, Virshup DM, Ptácek LJ, Fu Y-H, An hPer2 phosphorylation site mutation in familial advanced sleep phase syndrome., Science. 291 (2001) 1040–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Ashbrook LH, Krystal AD, Fu Y-H, Ptáček LJ, Genetics of the human circadian clock and sleep homeostat, Neuropsychopharmacol. 45 (2020) 45–54. 10.1038/s41386-019-0476-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Kaasik K, Kivimäe S, Allen JJ, Chalkley RJ, Huang Y, Baer K, Kissel H, Burlingame AL, Shokat KM, Ptáček LJ, Fu Y-H, Glucose sensor O-GlcNAcylation coordinates with phosphorylation to regulate circadian clock., Cell Metabolism. 17 (2013) 291–302. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Kohsaka A, Laposky AD, Ramsey KM, Estrada C, Joshu C, Kobayashi Y, Turek FW, Bass J, High-fat diet disrupts behavioral and molecular circadian rhythms in mice., Cell Metabolism. 6 (2007) 414–421. 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Eckel-Mahan KL, Patel VR, de Mateo S, Orozco-Solis R, Ceglia NJ, Sahar S, Dilag-Penilla SA, Dyar KA, Baldi P, Sassone-Corsi P, Reprogramming of the circadian clock by nutritional challenge., Cell. 155 (2013) 1464–1478. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Guan D, Xiong Y, Borck PC, Jang C, Doulias P-T, Papazyan R, Fang B, Jiang C, Zhang Y, Briggs ER, Hu W, Steger D, Ischiropoulos H, Rabinowitz JD, Lazar MA, Diet-Induced Circadian Enhancer Remodeling Synchronizes Opposing Hepatic Lipid Metabolic Processes, Cell. 174 (2018) 831–842.e12. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Acosta-Rodríguez VA, de Groot MHM, Rijo-Ferreira F, Green CB, Takahashi JS, Mice under Caloric Restriction Self-Impose a Temporal Restriction of Food Intake as Revealed by an Automated Feeder System., Cell Metabolism. 26 (2017) 267–277.e2. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Patel SA, Velingkaar N, Makwana K, Chaudhari A, Kondratov R, Calorie restriction regulates circadian clock gene expression through BMAL1 dependent and independent mechanisms., Scientific Reports. 6 (2016) 25970. 10.1038/srep25970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Sato S, Solanas G, Peixoto FO, Bee L, Symeonidi A, Schmidt MS, Brenner C, Masri S, Benitah SA, Sassone-Corsi P, Circadian Reprogramming in the Liver Identifies Metabolic Pathways of Aging., Cell. 170 (2017) 664–677.e11. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Tognini P, Murakami M, Liu Y, Eckel-Mahan KL, Newman JC, Verdin E, Baldi P, Sassone-Corsi P, Distinct Circadian Signatures in Liver and Gut Clocks Revealed by Ketogenic Diet., Cell Metabolism. 26 (2017) 523–538.e5. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Arble DM, Bass J, Laposky AD, Vitaterna MH, Turek FW, Circadian timing of food intake contributes to weight gain., Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.). 17 (2009) 2100–2102. 10.1038/oby.2009.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Hatori M, Vollmers C, Zarrinpar A, DiTacchio L, Bushong EA, Gill S, Leblanc M, Chaix A, Joens M, Fitzpatrick JAJ, Ellisman MH, Panda S, Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet., Cell Metabolism. 15 (2012) 848–860. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Gill S, Panda S, A Smartphone App Reveals Erratic Diurnal Eating Patterns in Humans that Can Be Modulated for Health Benefits., Cell Metabolism. 22 (2015) 789–798. 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Reinke H, Asher G, Crosstalk between metabolism and circadian clocks, Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio. 20 (2019) 227–241. 10.1038/s41580-018-0096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Minh NL, Damiola F, Tronche F, Schütz G, Schibler U, Glucocorticoid hormones inhibit food-induced phase-shifting of peripheral circadian oscillators, Embo J. 20 (2001) 7128–7136. 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Mahat DB, Salamanca HH, Duarte FM, Danko CG, Lis JT, Mammalian Heat Shock Response and Mechanisms Underlying Its Genome-wide Transcriptional Regulation, Molecular Cell. 62 (2016) 63–78. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Saini C, Morf J, Stratmann M, Gos P, Schibler U, Simulated body temperature rhythms reveal the phase-shifting behavior and plasticity of mammalian circadian oscillators., Genes & Development. 26 (2012) 567–580. 10.1101/gad.183251.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Laposky A, Easton A, Dugovic C, Walisser J, Bradfield C, Turek F, Deletion of the mammalian circadian clock gene BMAL1/Mop3 alters baseline sleep architecture and the response to sleep deprivation., Sleep. 28 (2005) 395–409. 10.1093/sleep/28.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Stokkan KA, Yamazaki S, Tei H, Sakaki Y, Menaker M, Entrainment of the circadian clock in the liver by feeding., Science. 291 (2001) 490–493. 10.1126/science.291.5503.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Chavan R, Feillet C, Costa SSF, Delorme JE, Okabe T, Ripperger JA, Albrecht U, Liver-derived ketone bodies are necessary for food anticipation, Nat Commun. 7 (2016) 10580. 10.1038/ncomms10580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Greco CM, Cervantes M, Fustin J-M, Ito K, Ceglia N, Samad M, Shi J, Koronowski KB, Forne I, Ranjit S, Gaucher J, Kinouchi K, Kojima R, Gratton E, Li W, Baldi P, Imhof A, Okamura H, Sassone-Corsi P, S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine hydrolase links methionine metabolism to the circadian clock and chromatin remodeling, Sci Adv. 6 (2020) eabc5629. 10.1126/sciadv.abc5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Koronowski KB, Kinouchi K, Welz P-S, Smith JG, Zinna VM, Shi J, Samad M, Chen S, Magnan CN, Kinchen JM, Li W, Baldi P, Benitah SA, Sassone-Corsi P, Defining the Independence of the Liver Circadian Clock, Cell. 177 (2019) 1448–1462.e14. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Ryu KW, Kim D-S, Kraus WL, New Facets in the Regulation of Gene Expression by ADP-Ribosylation and Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerases, Chemical Reviews. 115 (2015) 2453–2481. 10.1021/cr5004248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Asher G, Reinke H, Altmeyer M, Gutierrez-Arcelus M, Hottiger MO, Schibler U, Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 participates in the phase entrainment of circadian clocks to feeding., Cell. 142 (2010) 943–953. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Narasimamurthy R, Virshup DM, The phosphorylation switch that regulates ticking of the circadian clock, Mol Cell. (2021). 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Kula-Eversole E, Lee DH, Samba I, Yildirim E, Levine DC, Hong H-K, Lear BC, Bass J, Rosbash M, Allada R, Phosphatase of Regenerating Liver-1 Selectively Times Circadian Behavior in Darkness via Function in PDF Neurons and Dephosphorylation of TIMELESS., Current Biology : CB. (2020). 10.1016/j.cub.2020.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L, Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase, Nature. 403 (2000) 795–800. 10.1038/35001622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Purushotham A, Schug TT, Xu Q, Surapureddi S, Guo X, Li X, Hepatocyte-specific deletion of SIRT1 alters fatty acid metabolism and results in hepatic steatosis and inflammation., Cell Metabolism. 9 (2009) 327–338. 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Daitoku H, Hatta M, Matsuzaki H, Aratani S, Ohshima T, Miyagishi M, Nakajima T, Fukamizu A, Silent information regulator 2 potentiates Foxo1-mediated transcription through its deacetylase activity., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (2004) 10042–10047. 10.1073/pnas.0400593101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Masri S, Rigor P, Cervantes M, Ceglia N, Sebastian C, Xiao C, Roqueta-Rivera M, Deng C, Osborne TF, Mostoslavsky R, Baldi P, Sassone-Corsi P, Partitioning Circadian Transcription by SIRT6 Leads to Segregated Control of Cellular Metabolism., Cell. 158 (2014) 659–672. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Bogan KL, Brenner C, Nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, and nicotinamide riboside: a molecular evaluation of NAD+ precursor vitamins in human nutrition., Annual Review of Nutrition. 28 (2008) 115–130. 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Ch R, Rey G, Ray S, Jha PK, Driscoll PC, Santos MSD, Malik DM, Lach R, Weljie AM, MacRae JI, Valekunja UK, Reddy AB, Rhythmic glucose metabolism regulates the redox circadian clockwork in human red blood cells., Nature Communications. 12 (2021) 377–14. 10.1038/s41467-020-20479-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Lin SJ, Ford E, Haigis M, Liszt G, Guarente L, Calorie restriction extends yeast life span by lowering the level of NADH, Genes & Development. 18 (2004) 12–16. 10.1101/gad.1164804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Chen D, Bruno J, Easlon E, Lin S-J, Cheng H-L, Alt FW, Guarente L, Tissue-specific regulation of SIRT1 by calorie restriction., Genes & Development. 22 (2008) 1753–1757. 10.1101/gad.1650608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Williamson DH, Lund P, Krebs HA, The redox state of free nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide in the cytoplasm and mitochondria of rat liver., The Biochemical Journal. 103 (1967) 514–527. 10.1042/bj1030514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Goodman RP, Markhard AL, Shah H, Sharma R, Skinner OS, Clish CB, Deik A, Patgiri A, Hsu Y-HH, Masia R, Noh HL, Suk S, Goldberger O, Hirschhorn JN, Yellen G, Kim JK, Mootha VK, Hepatic NADH reductive stress underlies common variation in metabolic traits., Nature. 352 (2020) 231–5. 10.1038/s41586-020-2337-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Afshar G, Murnane JP, Characterization of a human gene with sequence homology to Saccharomyces cerevisiae SIR2., Gene. 234 (1999) 161–168. 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Schmidt MT, Smith BC, Jackson MD, Denu JM, Coenzyme specificity of Sir2 protein deacetylases: implications for physiological regulation., J Biol Chem. 279 (2004) 40122–40129. 10.1074/jbc.m407484200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Houtkooper RH, Cantó C, Wanders RJ, Auwerx J, The secret life of NAD+: an old metabolite controlling new metabolic signaling pathways., Endocrine Reviews. 31 (2010) 194–223. 10.1210/er.2009-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Borra MT, Langer MR, Slama JT, Denu JM, Substrate specificity and kinetic mechanism of the Sir2 family of NAD+-dependent histone/protein deacetylases., Biochemistry. 43 (2004) 9877–9887. 10.1021/bi049592e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Jin L, Wei W, Jiang Y, Peng H, Cai J, Mao C, Dai H, Choy W, Bemis JE, Jirousek MR, Milne JC, Westphal CH, Perni RB, Crystal structures of human SIRT3 displaying substrate-induced conformational changes., Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (2009) 24394–24405. 10.1074/jbc.m109.014928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Madsen AS, Andersen C, Daoud M, Anderson KA, Laursen JS, Chakladar S, Huynh FK, Colaço AR, Backos DS, Fristrup P, Hirschey MD, Olsen CA, Investigating the Sensitivity of NAD+-dependent Sirtuin Deacylation Activities to NADH., J Biol Chem. 291 (2016) 7128–7141. 10.1074/jbc.m115.668699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Rutter J, Reick M, Wu LC, McKnight SL, Regulation of clock and NPAS2 DNA binding by the redox state of NAD cofactors., Science. 293 (2001) 510–514. 10.1126/science.1060698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Baggs JE, Green CB, Nocturnin, a Deadenylase in Xenopus laevis Retina A Mechanism for Posttranscriptional Control of Circadian-Related mRNA, Curr Biol. 13 (2003) 189–198. 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Estrella MA, Du J, Chen L, Rath S, Prangley E, Chitrakar A, Aoki T, Schedl P, Rabinowitz J, Korennykh A, The metabolites NADP+ and NADPH are the targets of the circadian protein Nocturnin (Curled), Nat Commun. 10 (2019) 2367. 10.1038/s41467-019-10125-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Laothamatas I, Gao P, Wickramaratne A, Quintanilla CG, Dino A, Khan CA, Liou J, Green CB, Spatiotemporal regulation of NADP(H) phosphatase Nocturnin and its role in oxidative stress response, Proc National Acad Sci. 117 (2020) 993–999. 10.1073/pnas.1913712117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Hoxhaj G, Ben-Sahra I, Lockwood SE, Timson RC, Byles V, Henning GT, Gao P, Selfors LM, Asara JM, Manning BD, Direct stimulation of NADP+ synthesis through Akt-mediated phosphorylation of NAD kinase, Science. 363 (2019) 1088–1092. 10.1126/science.aau3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]