Abstract

Background

Tissue-agnostic drug development provides a paradigm shift in precision medicine and requires innovative trial designs. However, outcome selection for such trials can prove challenging. The objectives of this review were to:

-

(i)

Identify and map core outcome sets (COS), across 11 immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) in order to facilitate the selection of relevant outcomes across the conditions for innovative trials of tissue-agnostic drug therapies.

-

(ii)

Compare outcomes or endpoints recommended by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) to identify and highlight similarities and differences.

Methods

The Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET), International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM), FDA and EMA databases were searched from inception to 28th December 2019. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts of retrieved entries and conducted the subsequent full text screening. Hand searching of the reference lists and citation searching of the selected publications was conducted. The methodological quality of the included peer-reviewed articles was independently assessed by the reviewers based on the items of the COS–Standards for Development recommendations (COS–STAD) checklist. Core outcomes from the included publications were extracted and mapped across studies and conditions. Regulatory guidance from FDA and EMA, where available for clinical trials for the IMIDs, were obtained from their databases and recommendations on outcomes to measure directly compared.

Results

Forty-four COS publications were included in the final analysis. Outcomes such as disease activity, pain, fatigue, quality of life, physical function, work limitation/productivity, steroid use and biomarkers were recommended across majority of the conditions. There were significant similarities and differences in FDA and EMA recommendations. The only instance where either regulatory body directly referenced a COS was for jSLE—both referenced the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization (PRINTO) COS.

Conclusions

The findings from this systematic review provide valuable information to inform outcome selection in tissue-agnostic trials for IMIDs. There is a need for increased collaboration between regulators and COS developers and inclusion of regulators as key stakeholders in COS development to enhance the quality of COS.

Trial registration

Not registered.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13063-022-06000-w.

Keywords: Tissue-agnostic clinical trials, Core outcome set, COS, IMIDs, Rheumatoid arthritis, Rheumatology

Introduction

Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and Sjogren’s syndrome (SS) belong to a group of chronic and highly disabling inflammatory conditions [1]. Recent findings that these clinically dissimilar diseases share similar immune dysregulation and molecular drivers of inflammation has sparked an interest in the development of novel therapies that may be used across inflammatory diseases regardless of the specific diagnosis [2, 3]. Selection for such targeted treatment would be based on patients’ response to the novel drugs which would be determined by these molecular drivers [3].

This innovative approach mirrors the new ‘tissue-agnostic’ drug development paradigm in oncology where targeted therapies are developed based on molecular markers rather than organ or tissue type [4, 5]. Tissue-agnostic drug development has already shown considerable promise in oncology with the FDA granting accelerated approvals for drugs such as Keytruda (pembrolizumab) and Vitrakvi (larotrectinib) for the treatment of solid tumours [6]. The EMA recently granted the conditional approval of Vitrakvi [7].

Tissue-agnostic therapies in IMIDs may be evaluated in innovative clinical trials such as biomarker-adaptive and basket trials. Biomarker-adaptive trials incorporate adaptive clinical trial methodology to modify the trials according to the accumulating outcome data [8]. In basket trials, patients are primarily grouped according to molecular drivers rather than their specific diagnosis [9, 10]. The expectation is that group sensitivities to the therapies can be assessed and compared and populations most likely to benefit from treatment identified [9, 11]. The use of basket trials have increased over the past 5 years and is set to increase rapidly over the next few decades as it becomes more widely adopted [12].

To facilitate cross-disease comparisons, it is essential that trial data from the patient groups are comparable. However, at present, a wide variation exists in the outcomes, endpoints and measures selected for use in drug trials. It should be noted that there is a distinction between the terms ‘outcome’ and ‘endpoint’ [13]. According to the NIH Collaboratory ‘….outcome usually refers to the measured variable (e.g. peak volume of oxygen (VO2) or PROMIS Fatigue score), whereas an endpoint refers to the analysed parameter (e.g. change-from-baseline at 6 weeks in mean PROMIS Fatigue score)….’ [13] The variations in outcomes and endpoints measured in trials make it difficult to compare and/or synthesise outcome data within and across IMIDs [14]. As a result, there may be variations in the trial data submitted to support applications for drug approvals and health technology assessment making head-to-head comparisons of drug efficacy and cost-effectiveness analyses challenging.

Core outcome sets (COS), which propose a minimum set of outcomes to measure and report for all trials in specific condition(s), have been developed to assist with the standardisation of outcomes measured in clinical trials [14, 15]. However, there may be variations in the COS proposed for different IMIDs and by different organisations due to differing foci and interests. There is therefore a need to identify appropriate outcomes and endpoints to measure across IMIDs in innovative tissue-agnostic trials.

The Birmingham National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre for Inflammation was founded to improve healthcare for patients with chronic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, by developing and accelerating access to new diagnostic tests and new therapies. A programme of observational and experimental clinical trials will be undertaken to achieve this focusing on several IMIDs. The target IMIDs include the following: (i) rheumatoid arthritis (RA); (ii) juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA); (iii) ankylosing spondylitis (AS); (iv) psoriatic arthritis (PsA); (v) Sjogren’s syndrome (SS); (vi) Crohn’s disease (CD); (vii) ulcerative colitis (UC); (viii) uveitis (Uv); (ix) systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) including juvenile SLE (jSLE); (x) autoimmune hepatitis (AIH); and (xi) primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). This review therefore focuses on these 11 IMIDs.

The specific objectives were:

-

(i)

Identify and map core outcome sets (COS), across 11 IMIDs in order to facilitate the selection of relevant outcomes across the conditions for innovative trials of tissue-agnostic drug therapies.

-

(ii)

Compare outcomes or endpoints recommended by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) to identify and highlight similarities and differences.

Methods

This study was conducted in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [16] (see PRISMA checklist). Ethical approval was not required for this study as it did not use patient data.

Two reviewers (OLA, LFR) systematically searched from inception to 28th December 2019 four online resources namely the (i) Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET), (ii) International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM), (iii) European Medicines Agency (EMA) and (iv) US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) databases.

Search strategy

The search on the COMET database [17] was restricted by selecting 23 relevant disease terms from the ‘disease name’ menu (Additional file 1). The other databases did not have this function therefore the 11 disease terms listed above were entered directly into their search boxes. Guidance documents were obtained by specifically searching the ‘Guidance, Compliance, & Regulatory Information’ section of the FDA [18] and the ‘Scientific Guidelines, the Clinical Efficacy and Safety Guidelines’ section of the EMA website [19].

Selection of publications

Studies archived on the COMET database were eligible that reported preliminary or definitive COS and outcome measures established through ranked consensus-based methodologies [14]. Purely methodological studies, COS study protocols, reviews of outcomes, outcome measures or symptoms which do not report a consensus-based approach were excluded. Articles reporting COS developed for trials of non-pharmaceutical interventions were also excluded. Published COS from the ICHOM and regulatory guidance provided by the EMA and FDA databases were eligible if focussed on the conditions of interest.

Initial screening of all titles and abstracts was independently conducted by the reviewers (LFR, OLA). The full texts of publications potentially meeting the eligibility criteria were obtained and independently reviewed by the same reviewers. The reasons for exclusion at this stage were documented. At each stage, disagreements regarding eligibility were resolved through discussion and, if necessary, consultation with a third reviewer (MC). Reasons for exclusion were recorded. We conducted a hand search of reference lists and citation search of the included publications.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies peer-reviewed articles was independently assessed by the reviewers based on the items of the COS–Standards for Development recommendations (COS–STAD) checklist [20]. Differences in assessments were discussed and resolved.

Data extraction strategy

An electronic form was designed, piloted and used for data extraction by the reviewers (LFR, OLA). Data from all the COS publications (peer-reviewed COS articles and the regulatory guidance documents) were extracted verbatim by the two reviewers and cross-checked by a member of the research team (AR) for accuracy. Where available, the reviewers extracted information on:

-

(i)

Recommended core outcomes, endpoints and measures.

-

(ii)

Target patient populations (age, gender, inflammatory condition(s)), study design (e.g. interviews, focus groups, Delphi), contributing stakeholders (e.g. patients, healthcare professionals, carers), geographical location of stakeholders and setting for COS use.

-

(iii)

Methods used to derive, prioritise and/or select the final list of COS, endpoints and/or measures.

Data synthesis and presentation

The extracted outcomes and endpoints from the COS articles and regulatory guidance documents were grouped by OLA and LFR into sub-domains and domains based on their classification by the source publications. Where there were discrepancies in the domain and sub-domain classifications by different publications, the reviewers discussed and chose the most appropriate for this study. The reviewers inductively grouped domains into broad categories after completing data extraction based on characteristics of the domains.

A matrix was created for each condition displaying the core outcomes, endpoints and any recommended outcome measures extracted from each publication. Publications were arranged according to the COS’s target study design (e.g. longitudinal, clinical trial). These matrices were combined to form a single matrix showing all core outcomes, endpoints and measures recommended across all inflammatory conditions.

For the second study objective, the extracted outcomes, endpoints and measures recommended by the FDA and EMA in scientific guidance documents were separately compared to highlight similarities and differences. The findings were presented in a table. The matrix and the final tables were cross-checked by AR for accuracy.

Results

Characteristics of included publications

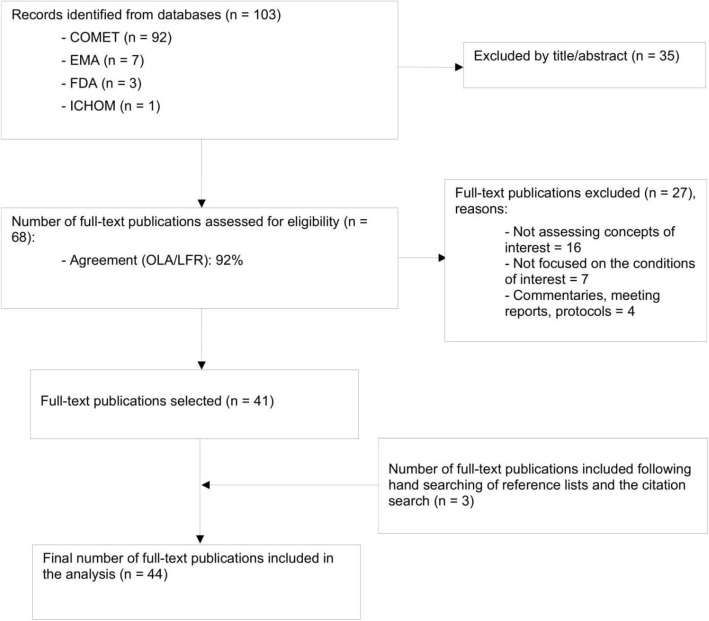

The selection process is depicted in a PRISMA flow diagram (see Fig. 1). Table 1 summarises the 44 included publications (peer-reviewed COS articles and regulatory guidance documents) and provides details on the characteristics of the included publications [21–64]. See Supplementary Table 2 for further details.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table 1.

Characteristics of included publications

| Characteristics | Inflammatory conditions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL | RA* | JIA | AS | PsA | SS | CD** | UC | Uv | SLE*** (jSLE) | |

| Total number included | 44 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 6 (2) |

| Type of publication: | ||||||||||

| Collaborative reports | 34 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 4 (2) |

| Regulatory guidance | 10 | 2X | 1e | 1e | 1e | 0 | 1e | 2X | 0 | 2X (0) |

| Patient population: | ||||||||||

| Adults | 37ap | 10ap | – | 4 | 8 | 2 | 5ap | 2ap | 0 | 6ap |

| Paediatric specific | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Purpose: | ||||||||||

| Trials and LOS | 43 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 6 (2) |

| Routine practice | 8 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Registries | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Methods: | ||||||||||

| Initial literature or systematic review/database search | 22 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 3 (0) |

| Surveys | 9 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 (1) |

| Interviews/focus groups | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Delphi/ NGT/other consensus group meeting | 32 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 4 (2) |

| Patient involvement | 14 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| HCP involvement | 34 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 4 (2) |

AS ankylosing spondylitis, CD Crohn’s disease, EMA European Medicines Agency, FDA Food and Drug Administration, HCP health care professionals, ICHOM International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement, JIA juvenile idiopathic arthritis, LOS longitudinal observation studies, NGT nominal group technique, PsA psoriatic arthritis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus, jSLE juvenile SLE, SS Sjogren’s syndrome, UC ulcerative colitis, uV uveitis

*ICHOM 2018 document for inflammatory arthritis covers RA, PsA, AS and JIA

**Kim 2018 and Ruemmele 2014 referred to both CD and UC (inflammatory bowel disease). To avoid confusion, these have been recorded under CD

***Values in brackets represent the subsets relating to jSLE (under SLE)

eDenotes an EMA publication whilst f represents an FDA document

xSignifies that both EMA and FDA produced documents for the condition

apSignifies the inclusion of publications with mixed patient populations

Number of publications included

COS were found for all conditions except AIH and PSC. A total of 92 publications from COMET were screened and of these 30 were included [22–25, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33, 35, 37–42, 45, 46, 48–51, 54–56, 58–61, 64]. EMA guidance for AS, CD, JIA, PsA, RA, SLE and UC [21, 26, 32, 34, 43, 52, 62], FDA guidance for RA, SLE and UC [44, 53, 63] and one document from the ICHOM database [47] were included. No regulatory guidance was found for Uv or SS. Following reference list and citation searching, three articles [29, 36, 57] were retrieved bringing the total number of publications included in the final analysis to 44 [21–64]. RA had the highest number of relevant publications (10 in all) whilst the only publication included for uveitis actually relates to JIA-related uveitis [64].

Study populations and settings

In terms of study populations, thirty-seven publications were associated with COS for adults or mixed populations [21–26, 28–30, 34–57, 60–63] whilst seven related to COS specifically for paediatric patients [27, 31–33, 58, 59, 64].

All the COS were designed/recommended for use in clinical trials and longitudinal observational studies (with the exception of the COS specifically developed for AS registries by Zochling et al. [24]). Five of these COS were also recommended for use in routine clinical practice for AS [23], perianal CD [28], inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [30], PsA [35] and RA [50]. The ICHOM COS was developed for use in clinical trials and routine practice for all ‘inflammatory arthritis’ [47].

Quality assessment

Consensus methods used

All the COS articles reported employing consensus methods—nine studies (28%) used Delphi/modified Delphi methods, 11 (34%) used nominal group technique and 12 (38%) employed unspecified consensus methods. The included articles generally provided adequate information pertaining to scope (COS-STAD items 1–4).

Stakeholder involvement

Information relating to stakeholder involvement (COS-STAD items 5–7) and consensus process (COS-STAD 8–11) were sometimes less detailed making it difficult to assess the degree of stakeholder involvement and the robustness of the consensus process. Whilst clinical experts were involved in the COS development process for 34 studies, only 14 publications explicitly reported patient involvement, with one reporting that patients were not involved [64]. Details about the characteristics of panels or working groups were often limited making it difficult to ascertain the inclusion of patients and their specific involvement. The period COS were developed seemed to influence the reporting of patient involvement. COS published within the last decade (such as Nikiphorou et al. [49] and Radner et al. [50] for RA; Orbai et al. [39] and Tillett et al. [41] for PsA) were more likely to report patient involvement explicitly than older ones (such as Felson et al. for RA [45] and Gladman et al. [37] for PsA). However, we were unable to rule out the possibility that the developers of some of the older COS might have involved patients to some degree but the authors have not reported this in their publication. See Additional file 2 for further details. It should be noted that the regulatory guidance documents did not report the use of any consensus process or stakeholder involvement to inform the recommendations provided.

Core outcomes proposed across the inflammatory conditions

Core outcomes proposed

Table 2 summarises the core outcomes extracted from the COS articles and the regulatory guidance documents across the nine included inflammatory conditions. Outcomes such as disease activity, joint/structural damage, pain, fatigue, quality of life, physical function, work limitation/productivity, steroid use and biomarkers (acute phase reactants) were recommended across majority of the conditions. Psychosocial function, psychological and emotional wellbeing were the least frequently recommended ‘generic’ outcomes across the conditions. Expectedly, outcomes such as rectal bleeding which is specific to UC and sicca symptoms which relate to SS had very low frequencies.

Table 2.

Core outcomes proposed across inflammatory conditions

| Category | Domain | Sub-domain/group | RA [50] | AS [22] | PsA [39] | SS [60] | CD [30] | UC [30] | SLE [56] | jSLE | JIA | Uv [64] | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease activity | |||||||||||||

| Patient global assessment of wellbeing | ✓† | ✓*† | ✓*† | ✓*† | ✓* | 5 | |||||||

| Clinician global assessment of disease activity | ✓† | ✓* | ✓* | ✓ | ✓*† | ✓* | 6 | ||||||

| Disease activity | ✓* | ✓ | ✓† | ✓*† | ✓*† | ✓*†~ | ✓*† | ✓* | 8 | ||||

| Low disease activity | ✓* | 1 | |||||||||||

| Musculoskeletal (MSK) disease activity | Peripheral joints | ✓*† | ✓*† | 2 | |||||||||

| Enthesitis | ✓*† | ✓*† | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| Dactylitis | ✓*† | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Spine symptoms | ✓*† | 1 | |||||||||||

| Tender joints | ✓*† | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Swollen joints | ✓*† | ✓* | 2 | ||||||||||

| Joint or structural damage | ✓*† | ✓*† | ✓* | ✓ | ✓† | 5 | |||||||

| Organ damage | ✓† | ✓*†~ | ✓* | 3 | |||||||||

| Systemic inflammation | ✓*† | 1 | |||||||||||

| Ocular surface damage | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Visual acuity | ✓† | 1 | |||||||||||

| Grade of cells in anterior chamber | ✓† | 1 | |||||||||||

| Grade of flare in anterior chamber | ✓† | 1 | |||||||||||

| Flares | ✓* | 1 | |||||||||||

| Comorbidities | ✓† | 1 | |||||||||||

| Biomarkers | Auto-antibody status | ✓† | ✓ | ✓† | 3 | ||||||||

| Anti-drug antibody | ✓* | 1 | |||||||||||

| Acute phase reactants | ✓*† | ✓*† | ✓* | ✓* | ✓* | ✓* | 6 | ||||||

| Unspecified | ✓ | ✓† | 2 | ||||||||||

| Laboratory indices | ✓*† | 1 | |||||||||||

| MAS | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Skin disease activity | Skin | ✓*† | 1 | ||||||||||

| Nails | ✓*† | 1 | |||||||||||

| Itching | ✓† | 1 | |||||||||||

| Perianal disease activity | |||||||||||||

| Dev of perianal abscess | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Dev of a new/recurrent fistula | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Unplanned surgical intervention | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Faecal diversion/ proctectomy | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Clinical endpoints | Mucosal healing (endoscopic) | ✓*~ | ✓* | 2 | |||||||||

| Histological evaluation of mucosal inflammation | ✓* | 1 | |||||||||||

| Symptomatic remission | ✓* | ✓* | 2 | ||||||||||

| Clinical remission | ✓*† | ✓*†~ | ✓†* | 3 | |||||||||

| Remission without steroid | ✓*~ | ✓* | 2 | ||||||||||

| Complete clinical response | ✓~ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Sustained clinical benefit | ✓~ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Radiological remission | ✓~ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Radiological response | ✓~ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Deep remission | ✓~ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Occlusive symptoms (absence) | ✓~ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Endoscopic remission | ✓~ | ||||||||||||

| Bowel damage progression | ✓~ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Treatment and therapeutic failure | ✓~ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Long term efficacy | ✓~ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Steroid free | ✓~ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Clinical success/benefit | ✓~ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Fistula healing | ✓* | 1 | |||||||||||

| Time to remission | ✓* | ✓* | 2 | ||||||||||

| Time to response | ✓* | ✓* | 2 | ||||||||||

| Clinical assessment of drainage | ✓* | 1 | |||||||||||

| Salivary flow | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Ophthalmic outcome | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Symptom free survival | ✓~ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Overall survival | ✓† | ✓† | 2 | ||||||||||

| Colorectal cancer | ✓† | ✓† | 2 | ||||||||||

| Symptoms, QOL, function | |||||||||||||

| Pain | ✓*† | ✓*† | ✓*† | ✓† | ✓† | ✓* | 6 | ||||||

| Anaemia | ✓† | ✓† | 2 | ||||||||||

| Morning stiffness | ✓* | 1 | |||||||||||

| Spinal stiffness and mobility | ✓*† | 1 | |||||||||||

| Fatigue | ✓* | ✓*† | ✓† | ✓ | ✓† | ✓† | ✓* | ✓ | 8 | ||||

| Fever | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| HRQOL (Generic) | ✓† | ✓* | ✓*† | ✓† | ✓ | ✓*†~ | ✓* | ✓ | ✓† | 9 | |||

| HRQOL (Specific) | ✓* | ✓*† | ✓ | ✓*~ | ✓* | ✓*~ | 6 | ||||||

| Physical function/Disability | ✓*† | ✓*† | ✓*† | ✓†~ | ✓†~ | ✓* | ✓† | 7 | |||||

| Function (General) | ✓* | ✓† | ✓* | 3 | |||||||||

| Psychosocial function | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| Psychological health/emotional well being | ✓ | ✓ | ✓# | ✓ | 4 | ||||||||

| Sexual activity | ✓# | 1 | |||||||||||

| Overall control | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Work limitation/productivity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓# | ✓* | 5 | |||||||

| Sicca symptoms | Dry eyes | ✓† | 1 | ||||||||||

| Dry mouth | ✓† | 1 | |||||||||||

| Change in bowel symptoms | ✓† | ✓† | 2 | ||||||||||

| Rectal bleeding | ✓* | 1 | |||||||||||

| Stool frequency | ✓* | 1 | |||||||||||

| Stool consistency | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Impact of fistula | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Global assessment of incontinence | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Healthcare utilisation | |||||||||||||

| Surgery | ✓ | ✓~ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||||

| Reduction in surgical procedures | ✓* | 1 | |||||||||||

| Time spent/number of hospital visits | ✓† | ✓† | ✓† | 3 | |||||||||

| DMARD use | ✓† | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Steroid use | ✓† | ✓† | ✓*† | ✓*~ | ✓ | 5 | |||||||

| Non-drug treatments | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Others | |||||||||||||

| SAE/safety outcomes | ✓ | ✓*† | ✓†~ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||||

| Toxicity | ✓ | ✓† | 2 | ||||||||||

| Death/cause of death | ✓ | ✓ | ✓~ | 3 | |||||||||

| Cost/Cost-effectiveness | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Weight | ✓† | ✓† | ✓† | 3 | |||||||||

| Nutritional status | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Disease duration | ✓† | 1 | |||||||||||

| Smoking | ✓† | 1 | |||||||||||

| Paediatric-specific | |||||||||||||

| Parent global assessment of disease activity | ✓ | ✓† | 2 | ||||||||||

| Growth | ✓* | ✓ | ✓† | ✓ | 4 | ||||||||

| Improved growth pattern | ✓* | 1 | |||||||||||

| Normalised growth | ✓* | 1 | |||||||||||

| School absence | ✓† | 1 | |||||||||||

| Extra-intestinal manifestations | ✓* | 1 |

AS ankylosing spondylitis, CD Crohn’s disease, DMARDs disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, HRQOL health-related quality of life, JIA juvenile idiopathic arthritis, MAS macrophage activation syndrome, PsA psoriatic arthritis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, SAE serious adverse event, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus, jSLE juvenile SLE, SS Sjogren’s syndrome, UC ulcerative colitis, uV uveitis

*Suggested by EMA and/or FDA

†Proposed as part of core outcome set by non-regulatory research groups

# It was suggested that these 3 domains along with ‘Lifestyle restriction based on toileting needs’ be combined to give a ‘patient priorities’ score (Sahnan 2018)

~ Proposed as critical or important endpoints for CD by Danese et al. [25] or suggested as endpoints for SLE by Gordon [54]

Definitions

Symptomatic remission—complete absence of occlusive symptoms—abdominal pain and/or nausea and/or vomiting and/or bloating and/or diet restriction after meals (Danese 2018)

Sustained clinical benefit—no additional treatment and daily life nearly symptom-free, or additional treatment (except surgery) with good function in society

Radiological remission—bowel wall thickness (< 3 mm), bowel dilation (diameter < 25 mm). Bowel stricture (diameter > 10 mm)

Deep remission—complete mucosal healing and clinical/biochemical remission (defined as HBI score < 5 ± CRP < 5 mg/L or calprotectin < 50 mg/g)

Treatment failure - Any CD-related surgery, or hospitalisation, or penetrating complication, or need for corticosteroids or biological drug

Therapeutic failure - CD-related surgery, or drug discontinuation because of lack of efficacy, or loss of response, or failure to respond to dose escalation or intolerance, or drug switched to another drug because of inadequate response/loss of response

Fistula healing - Closure and maintenance of closed fistula without development of new fistulas or abscesses

Approach to outcome recommendations

One of the issues identified by this review was the difference in approach by the various COS developers and regulatory bodies. Regulatory bodies often suggested a list of ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ endpoints from which trialists may make selections. On the other hand, COS developers propose a minimum set of outcomes (core items) to be measured in trials, sometimes complemented by optional or ‘outer core’ items [39].

Terminological inconsistencies

Another observation was the inconsistency in terminologies used by both regulatory bodies and COS developers. For example, the study by Heijde et al. [22] used the terms ‘measures’, ‘endpoints’ and ‘domains’ interchangeably to refer to outcomes such as pain and physical function [22]. Similarly, the 2015 EMA guidance for SLE [52] used the terms ‘outcomes’ and ‘endpoints’ interchangeably. The report stated ‘primary outcomes’ before going on to discuss ‘secondary endpoints’ [52].

Differences in recommendations

There were sometimes differences in the recommendations by regulatory bodies and COS developers. For example, the 2018 EMA guidance for Crohn’s disease [26] recommended fistula healing (demonstrated by MRI) as the primary endpoint for fistulising perianal Crohn’s disease whilst the COS developed by Shahan et al. [28], for the same population, included fistula response on MRI as optional [28].

There were disparities in recommendations for the use of biomarkers as outcomes or measures, with some studies cautioning against their use in specific patient subpopulations or disease stages. For instance, Ruemmele et al. [31] noted that C-reactive protein (CRP) is not elevated in all patients with active Crohn’s disease, limiting its usefulness, and although superior to CRP, faecal calprotectin has large variability in results and low responsiveness [31].

Outcome measures proposed across the target IMIDs

Outcome measures proposed across the target IMIDs can be found in Additional file 3.

Availability of outcome measures

It was observed that COS research groups tended to focus initially on achieving consensus and publishing their COS before commencing work on outcome measures to recommend in subsequent publications. For instance, Heijde et al. only reported the COS for AS in their initial article in 1997 [22]. However, 2 years later they published their work on outcome measures [23]. A similar scenario was observed with PsA where an earlier paper authored by Gladman et al. for the OMERACT PsA Working Group only reported COS [35] whilst a subsequent article presented outcome measures [36]. The latest publication from the group reported an update of the PsA COS and intimated that a thorough investigation of available measures would be commenced [38].

Information about validity of outcome measures

Although the COS studies suggested outcome measures to measure majority of the proposed COS, there was patchy information about the validity of these measures. Whilst the regulatory guidance and a few studies such as Gladman [36] explicitly discussed the available evidence of the validity of the measures proposed, the majority of the studies did not. Therefore, the basis of their recommendations was unclear, and this might explain the heterogeneity that was found in the recommendations.

Comparison of FDA and EMA recommendations

We were only able to compare FDA and EMA recommendations extracted for RA, SLE, jSLE and UC as these were the only conditions that had published FDA guidance documents. The findings are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of FDA and EMA guidance

| FDA | EMA | |

|---|---|---|

| RA |

FDA 2013 guidance [65] Key RA domains: (i) Clinical response: ACR20 to demonstrate reduction in disease activity. Supportive evidence of efficacy: (a) higher levels of response, measured by ACR50, ACR70 (b) measures of low disease activity (LDA): DAS28 (ii) Improvement in physical function: HAQ-DI Other domains: (i) Prevention of structural damage progression: Radiographic data using validated scoring methods. (ii) (ii) Clinical remission: ACR/EULAR Provisional Definition of Remission criteria may be acceptable. |

EMA 2017 guidance [66] Primary endpoint(s): (i) Remission (3–6 months): by a combined measure (studies on the treatment of naïve patient) (ii) LDA (3–6 months): In patients with inadequate response to synthetic or biologic DMARD treatment: DAS28-CRP, DAS28-ESR, SDAI or CDAI Secondary endpoints: (i) ACR20, ACR50, ACR70 responder rates (ii) Structural joint damage by X-rays (e.g. Sharp-van der Heijde scores) (iii) Physical function (e.g. HAQ-DI) (iv) Remission/LDA rates defined by SDAI, CDAI, DAS28-ESR or-CRP (if not already not chosen as primary endpoint) Others: (i) CRP (ii) Pain: VAS or Numeric Rating Scale (iii) Quality of Life: SF-36, AIMS (iv) Fatigue: FACIT-F (v) Ultrasonography of the joints (vi) MRI of the joints (RAMRIS scale) |

| SLE |

FDA 2010 guidance [68] Primary Efficacy Endpoints: (i) Reduction in disease activity: BILAG is the preferred index. SLEDAI, SELENA-SLEDAI, SLAM, ECLAM. The primary efficacy analysis can be based on the outcome of major clinical response (MCR) or partial clinical response (PCR) (ii) Complete clinical response or remission (iii) Reduction in flare/increase in time to flare (iv) Reduction in concomitant steroids (v) Treatment of serious acute manifestations Secondary endpoints: (i) PRO instruments: No existing PRO instrument was considered optimal for measurement of fatigue symptom complex. Others: (i) An assessment of damage caused by manifestations of SLE least 1-year duration (SLICC/ACR Damage Index measures) (ii) Biomarkers |

EMA 2015 guidance [67] Primary outcomes: (i) Control of the disease activity (SLEDAI and BILAG, SLE Responder Index [SRI] or BICLA (ii) Prevention of flares (Criteria for flares should be predetermined in the protocol: using SLEDAI-2 K, SELENA-SLEDAI, BILAG score; time to a new flare or the frequency/annual rate of flares) (iii) Prevention of long-term damage (the SLICC/ACR damage index, clinical trial should be at least 12 months) Secondary endpoints: (i) When a composite endpoint is used as a primary outcome measure components of this composite endpoint should be analysed separately as secondary outcomes (ii) Decrease in steroid dose (iii) Patients and investigators reported outcomes: (a) HRQOL – SF-36 and any of: Lupus QoL, SLE symptom checklist, SLE QOL; WPAI Lupus score; FSS; FACIT-F or BFI; ADL for change in physical function (iv) Biomarkers |

| jSLE |

FDA SLE 2010 [68] referencing PRINTO core set of domains: (i) A DAI: e.g. ECLAM, SLEDAI, SLAM, BILAG (ii) Renal function: 24-h proteinuria (iii) Parent’s global (iv) Physician’s global (v) Health status: CHQ physical summary score |

EMA 2015 [67] referenced the PRINTO domains: (i) Physician’s global assessment of disease activity (ii) A global DAI (e.g. ECLAM, SLEDAI, SLAM, BILAG (iii) 24-h proteinuria. Alternatively, the spot urine protein: creatinine ratio on first morning void urine sample (iv) Patient’s/Parent’s global assessment of the overall patient’s wellbeing (v) HRQOL: CHQ physical summary score |

| UC |

FDA 2016 [70] Primary endpoints: (i) Clinical remission (responder definition based on stool frequency, rectal bleeding and endoscopy scores). This is the recommended one. Until a valid PROM for UC signs and symptoms and a valid clinician rating scale for mucosal inflammation in UC become available, a modified Mayo or modified UCDAI score (omitting the physician’s global or disease activity ratings) can be used as an endpoint measure. Secondary endpoints: (i) Changes between the treatment arms of each of the subscores (Stool Frequency, Rectal Bleeding and Endoscopy) (ii) And/or the total score (i.e. sum of the Stool Frequency, Rectal Bleeding and Endoscopy subscores). (iii) Corticosteroid-free remission (based on a justified minimum duration of time over which a patient is considered to be both corticosteroid-free and in clinical remission) (iv) Endoscopic Appearance of the Mucosa - There are currently limitations of histologic scoring systems and of community standards for definitions of histologic improvement; thus, there are currently no criteria for histological assessment of mucosal healing. |

EMA 2018 [69] Stressed that the total Mayo score including physician’s global assessment is not of primary interest. Primary endpoint: (i) Proportion of patients with symptomatic remission (ii) Proportion of patients with endoscopic remission Secondary endpoints: (i) Patients achieving both MH and symptomatic remission (ii) Patients achieving response: Response should be defined according to the instruments used for evaluating symptoms and endoscopic appearance. (iii) Patients achieving remission defined more stringently than for the primary endpoint or vice versa (iv) In studies where steroids are not tapered at time of evaluation of the primary endpoint, (a) proportions of patients in whom either or both symptomatic and endoscopic remission are achieved without concomitant steroid treatment (b) proportions of patients in whom either or both symptomatic and endoscopic remission are achieved at particular doses of concomitant steroid treatment (v) Numerical, separate evaluations of the individual components of the symptom score and of MH score (vi) Histological evaluation of mucosal inflammation, including number of patients achieving histological normalisation (vii) Individual patients achieving MH, judged endoscopically, as well as combined symptomatic, biomarker and histological normalisation (viii) Changes in stool frequency (ix) Laboratory measures of inflammation (e.g. faecal calprotectin) (x) Time to remission (symptom scores and biomarkers only) (xi) Time to response (symptom scores and biomarkers only) Other secondary endpoints: (xii) Validated QoL measurement, e.g. inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (IBDQ) (xiii) Reduction in number of colectomies (primarily relevant in studies of acute severe ulcerative colitis). |

Lupus QoL Lupus Quality of Life, SLE QoL SLE symptom checklist and SLE Quality of Life, WPAI Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Lupus score, FSS fatigue severity scale, BFI FACIT fatigue or the Brief Fatigue Inventory, ECLAM ADL for change in physical function. European Consensus Lupus Activity Measure, SLEDAI Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index, SLAM Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Activity Measure, BILAG British Isles Lupus Assessment Group, DAI disease activity index, CHQ Child Health Questionnaire, IBDQ inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire, UCDAI Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity Index, HAQ-DI Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index, ACR American College of Rheumatology

Comparison of guidance for RA

Comparing the FDA 2013 guidance for RA [65] with the corresponding EMA 2017 document [66], there were three key differences. Whilst the FDA regards clinical response measured by the ACR20 as a key domain for RA, and clinical remission as a secondary domain, the EMA considers clinical remission as a primary endpoint and does not recommend improvement in measures such as ACR20 as primary endpoints as their ‘clinical relevance may not be immediately clear’. [65, 66] In addition, the FDA guidance considered improvement in physical function as a key domain to assess whilst the EMA considered it as a secondary endpoint [65, 66]. However, both recommended the HAQ-DI for the assessment of physical function [65, 66].

Comparison of guidance for SLE

The FDA 2010 guidance for SLE and the corresponding EMA 2015 guidance considered the assessment of disease activity index (DAI), and reduction in flares as primary endpoints [67, 68]. Similar measures including the BILAG, SLEDAI, SLAM and ECLAM were recommended by both regulatory bodies to assess these two endpoints [67, 68]. However, whilst the FDA guidance regarded a reduction in concomitant steroids as a primary endpoint and the assessment of damage as a secondary endpoint, the order was reversed in the EMA guidance. Both documents recommended that the SLICC/ACR Damage Index is used to assess damage over a minimum period of 12 months [67, 68]. The FDA opinion was that there were no optimal measures for fatigue and so did not recommend any PRO measures [68]. On the other hand, the EMA recommended combining the SF-36 with any of the SLE-specific measures and also the FACIT-F or the BFI for the assessment of fatigue [67].

Interestingly, the FDA and EMA recommendations for jSLE matched well as both referenced the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization (PRINTO) COS [59, 67, 68]. This was the only instance where either regulatory body directly referenced a COS.

Comparison of guidance for UC

The key difference between the FDA and EMA guidance for UC was their position on the use of endoscopic remission as a primary endpoint/outcome [69, 70]. The FDA stated that ‘there are currently limitations of histological scoring systems and of community standards for definitions of histological improvement; thus, there are currently no criteria for histological assessment of mucosal healing’ and recommends endoscopic remission as a secondary endpoint [70]. On the other hand, the EMA considered the proportion of patients with endoscopic remission as a primary endpoint [69]. Both regulatory bodies felt there were issues with using the total Mayo score due to the inclusion of physician’s global assessment [69, 70]. The FDA suggested using a modified Mayo or modified UCDAI score (omitting the physician’s global) whilst the EMA stated that the total Mayo score ‘is not of primary interest’. [69, 70] Again the FDA did not consider any PROM as suitable for evaluating the signs and symptoms of UC whilst the EMA recommended validated PROMs such as the IBDQ as a secondary endpoint [69, 70].

Discussion

This systematic review has identified and mapped, for the first time, existing COS currently recommended for efficacy trials across multiple immune-mediated inflammatory diseases and compared outcomes and/or endpoints recommended by FDA and EMA for similarities and differences.

COS were found for all the conditions except AIH and PSC. The COS found for uveitis was specifically for JIA-related uveitis [64]. Outcomes such as disease activity, joint/structural damage, pain, fatigue, quality of life, physical function, work limitation/productivity, steroid use and biomarkers (acute phase reactants) were recommended across majority of the conditions and should be considered when designing basket trials for tissue-agnostic drug development involving patients with inflammatory diseases. For basket trials, trialists should consider using these common outcomes identified across the conditions in this review as a minimum set and supplement with other outcomes as required for each condition. This will therefore facilitate the comparison of outcomes across IMIDs in basket trials. The review also provides a useful repository of COS for inflammatory diseases and regulatory guidance.

There were significant similarities and differences in FDA and EMA recommendations. The only instance where either regulatory body directly referenced a COS was for jSLE—both referenced the PRINTO COS.

The relatively voluminous literature for some of the conditions, notably for RA and PsA, attests to considerable progress in the recommendation of outcome measures for these conditions. On the other hand, our review highlights the research effort required to produce COS for other conditions, particularly uveitis and Sjogren’s syndrome, for which we found very limited published information.

The differences in approach and inconsistent terminologies used by the regulators and COS developers might explain the disparities we sometimes found in some of the recommendations. Efforts should be made to harmonise the terminologies used by all the organisations. The fact that there was only on instance of the FDA and the EMA directly referencing a COS also indicates the need for increased collaboration across regulators and COS developers and inclusion of regulators in COS development.

Less than half of the COS publications explicitly reported patient involvement and when presented details of this involvement were often vague, with the exception of Tillett et al. [41] The implication of this is that some outcomes included in the COS might not be outcomes meaningful or highly prioritised by patients. The selection of stakeholder relevant outcomes and the need for patient involvement in regulatory decision-making is increasingly recognised as important [71–73].

The main limitation of this study is its reliance on the information explicitly provided in the included publications. For instance, although we noticed a tendency for more recent publications to detail patient involvement in the development of COS, we were unable to rule out the possibility that the developers of some of the older COS might have involved patients to some degree but the authors have not reported this in their publication.

Another limitation of the study is the lack of publications for some conditions such as PSC and the overrepresentation by RA. However, we have ensured that our tables present the results in a manner that clearly reflects this issue. As FDA guidance documents were not available for all the conditions, we were unable to directly compare the recommendations provide by the FDA and EMA for a number of the conditions.

The scope of this review was determined by our programme-specific requirements. Therefore, our findings and conclusions may not be applicable to research that involves a different selection of IMIDs. As the purpose of the review is to facilitate the selection of outcomes across several IMIDs for basket trials, there may be differences between the outcomes recommended in this review and previously published disease-specific COS.

Despite these limitations, by allowing comparison of COS across conditions, this review could facilitate the selection of commonly relevant outcomes that may be measured in tissue-agnostic trials. Measuring the same outcomes across the conditions would demonstrate more accurately the similarities or variations in the response to drug interventions between patient groups. This information could also guide the subsequent recommendations for drug approval. However, further work needs to be done to address the gaps identified especially relating to outcome measures to use in trials. The review highlights the need for greater collaborations between regulatory bodies and COS developers so that stronger and more uniform recommendations can be made which may facilitate the adoption COS. There is also a need for collaboration on the development of COS for routine care which is particularly important for real-world evidence (RWE) generation [74].

Conclusions

Tissue-agnostic drug development which utilise current advances in precision medicine such as basket trials, have the potential to usher in a new era of drug development in IMIDs. The measurement of a core set of outcomes across the conditions in such trials could facilitate the collection of more robust efficacy data by facilitating direct comparisons between patient groups. This information could potentially improve and strengthen subsequent drug approvals, recommendations and labelling claims. Outcomes such as disease activity, joint/structural damage, pain, fatigue, quality of life, physical function, work limitation/productivity, steroid use and biomarkers (acute phase reactants) should be considered when designing basket trials for tissue-agnostic drug development involving patients with inflammatory diseases. There is a need for increased collaboration between regulators and COS developers and inclusion of regulators as key stakeholders in COS development to enhance the quality of COS.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: COMET database search

Additional file 2: Characteristics of included publications

Additional file 3: Outcome measures proposed across inflammatory conditions

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Drs Dan O’Connor and Bellinda L. King-Kallimanis for their helpful comments on the manuscript. The views expressed are not of the MHRA or the FDA.

Abbreviations

- ACR

American College of Rheumatology

- AIH

Autoimmune hepatitis

- AS

Ankylosing spondylitis

- BFI

Brief Fatigue Inventory

- BILAG

British Isles Lupus Assessment Group

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- CHQ

Child Health Questionnaire

- COMET

Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials

- COS

Core outcome set(s)

- COS-STAD

COS–Standards for Development recommendations

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- DAI

Disease Activity Index

- ECLAM

European Consensus Lupus Activity Measure

- EMA

European Medicines Agency

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FSS

Fatigue severity scale

- HAQ-DI

Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- IBDQ

Inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire

- ICHOM

International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement

- IMIDs

Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases

- JIA

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- jSLE

Juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus

- NIHR

National Institute for Health Research

- PRINTO

Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- PsA

Psoriatic arthritis

- PSC

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

- RWE

Real-world evidence

- SLAM

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Activity Measure

- SLE

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- SLEDAI

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index

- SLE QOL

SLE symptom checklist and SLE Quality of Life

- SS

Sjogren’s syndrome

- UC

Ulcerative colitis

- UCDAI

Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity Index

- Uv

Uveitis

- WPAI

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment

Authors’ contributions

Guarantor: OLA is the guarantor and accepts full responsibility for the work and the decision to publish. Specific author contributions: Study concept and design: MJC, OLA, LFR, CDB and PNN conceived the study. OLA, LFR, MJC and AR analysed and interpreted the data. OLA and LFR drafted the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final draft of the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding

This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Birmingham (Grant Reference Number BRC-1215-20009). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The funder played no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Relevant data has been provided in tables and additional files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

OLA, PNN and MC were supported by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre (BRC), West Midlands, Birmingham. OLA also receives funding from the Health Foundation and personal fees from Gilead Sciences Ltd.

MC is an NIHR Senior Investigator and reports grants from UKRI, NIHR, Macmillan Cancer Support, PCORI, Innovate UK, NIHR Surgical Reconstruction and Microbiology Research Centre (SRMRC), NIHR Applied Research Collaborative, West Midlands at the University of Birmingham and University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, HDRUK, Gilead, GSK and Janssen and personal fees from Astellas, Aparito Ltd, CIS Oncology, Takeda, Merck, Glaukos, GSK and Daiichi Sankyo outside the submitted work. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Olalekan Lee Aiyegbusi, Email: O.L.Aiyegbusi@bham.ac.uk.

Lavinia Ferrante di Ruffano, Email: L.FerrantediRuffano@bham.ac.uk.

Ameeta Retzer, Email: A.Retzer@bham.ac.uk.

Philip N. Newsome, Email: P.N.Newsome@bham.ac.uk

Christopher D. Buckley, Email: C.D.BUCKLEY@bham.ac.uk

Melanie J. Calvert, Email: M.Calvert@bham.ac.uk

References

- 1.El-Gabalawy H, Guenther LC, Bernstein CN. Epidemiology of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: incidence, prevalence, natural history, and comorbidities. J rheumatol. 2010;85:2. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Croft AP, Campos J, Jansen K, Turner JD, Marshall J, Attar M, et al. Distinct fibroblast subsets drive inflammation and damage in arthritis. Nature. 2019;570(7760):246–251. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1263-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker KF, Isaacs JD. Novel therapies for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: what can we learn from their use in rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(2):175–187. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flaherty KT, Le DT, Lemery S. Tissue-agnostic drug development. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book Am Soc Clin Oncol Meet. 2017;37(37):222–230. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_173855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dugger SA, Platt A, Goldstein DB. Drug development in the era of precision medicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;17(3):183–196. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemery S, Keegan P, Pazdur R. First FDA approval agnostic of cancer site - when a biomarker defines the indication. New Engl J Med. 2017;377(15):1409–1412. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1709968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.EMA. Vitrakvi: European Medicines Agency; 2019. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/vitrakvi. Accessed 30 Jan 2020.

- 8.Freidlin B, Korn EL. Biomarker-adaptive clinical trial designs. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;11(12):1679–1682. doi: 10.2217/pgs.10.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redig AJ, Jänne PA. Basket trials and the evolution of clinical trial design in an era of genomic medicine. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(9):975–977. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.8433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West H. Novel precision medicine trial designs: umbrellas and baskets. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(3):423. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ornes S. Core concept: basket trial approach capitalizes on the molecular mechanisms of tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(26):7007–7008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608277113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JJH, Siden E, Zoratti MJ, Dron L, Harari O, Singer J, Lester RT, Thorlund K, Mills EJ. Systematic review of basket trials, umbrella trials, and platform trials: a landscape analysis of master protocols. Trials. 2019;20(1):572. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3664-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtis L, Hernandez A, Weinfurt K. Choosing and specifying endpoints and outcomes: introduction. Bethesda, MD. NIH Health Care Syst Res Collab. Available from: https://rethinkingclinicaltrials.org/chapters/design/choosing-specifying-end-points-outcomes/choosing-and-specifying-endpoints-and-outcomes-introduction/.

- 14.Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, Barnes KL, Blazeby JM, Brookes ST, et al. The COMET Handbook: version 1.0. Trials. 2017;18(3):280. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1978-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tunis SR, Clarke M, Gorst SL, Gargon E, Blazeby JM, Altman DG, Williamson PR. Improving the relevance and consistency of outcomes in comparative effectiveness research. J Comp Eff Res. 2016;5(2):193–205. doi: 10.2217/cer-2015-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Search the COMET database. COMET Initiative. Available from: http://www.comet-initiative.org/studies/search.

- 18.Guidance, Compliance & Regulatory Information (Biologics). US Food and Drug Administration. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents. Accessed 28 Dec 2019.

- 19.European Medicines Agency. Clinical efficacy and safety guidelines. Eur Med Agency. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/scientific-guidelines/clinical-efficacy-safety/clinical-efficacy-safety-rheumatologymusculoskeletal-system. Accessed 28 Dec 2019.

- 20.Kirkham JJ, Gorst S, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Clarke M, Devane D, Gargon E, Moher D, Schmitt J, Tugwell P, Tunis S, Williamson PR. Core Outcome Set–STAndards for Reporting: The COS-STAR Statement. PLoS Med. 2016;13(10):e1002148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.EMA. Guideline on the Clinical Investigation of Medicinal Products for the Treatment of Axial Spondyloarthritis. European Medicines Agency. 2017. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-clinical-investigation-medicinal-products-treatment-axial-spondyloarthritis-revision-1_en.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

- 22.van der Heijde D, Bellamy N, Calin A, Dougados M, Khan MA, van der Linden S. Preliminary core sets for endpoints in ankylosing spondylitis. Assessments in Ankylosing Spondylitis Working Group. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(11):2225–2229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Heijde D, Calin A, Dougados M, Khan MA, van der Linden S, Bellamy N. Selection of instruments in the core set for DC-ART, SMARD, physical therapy, and clinical record keeping in ankylosing spondylitis. Progress report of the ASAS Working Group. Assessments in Ankylosing Spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(4):951–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zochling J, Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Braun J. Development of a core set of domains for data collection in cohorts of patients with ankylosing spondylitis receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(6):1079–1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danese S, Bonovas S, Lopez A, Fiorino G, Sandborn WJ, Rubin DT, Kamm MA, Colombel JF, Sands BE, Vermeire S, Panes J, Rogler G, D’Haens G, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Identification of endpoints for development of antifibrosis drugs for treatment of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(1):76–87. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.EMA. Guideline on the development of new medicinal products for the treatment of Crohn’s Disease. European Medicines Agency, 2018. Document number: CPMP/EWP/2284/99 Rev. 2. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-development-new-medicinal-products-treatment-crohns-disease-revision-2_en.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

- 27.Griffiths AM, Otley AR, Hyams J, Quiros AR, Grand RJ, Bousvaros A, Feagan BG, Ferry GR. A review of activity indices and end points for clinical trials in children with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11(2):185–196. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200502000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sahnan K, Tozer PJ, Adegbola SO, Lee MJ, Heywood N, McNair AGK, Hind D, Yassin N, Lobo AJ, Brown SR, Sebastian S, Phillips RKS, Lung PFC, Faiz OD, Crook K, Blackwell S, Verjee A, Hart AL, Fearnhead NS, ENiGMA collaborators Developing a core outcome set for fistulising perianal Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2019;68(2):226–238. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, Lochs H, Löfberg R, Modigliani R, Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Schölmerich J, Stange EF, Sutherland LR. A review of activity indices and efficacy endpoints for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(2):512–530. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim AH, Roberts C, Feagan BG, Banerjee R, Bemelman W, Bodger K, Derieppe M, Dignass A, Driscoll R, Fitzpatrick R, Gaarentstroom-Lunt J, Higgins PD, Kotze PG, Meissner J, O’Connor M, Ran ZH, Siegel CA, Terry H, van Deen WK, van der Woude CJ, Weaver A, Yang SK, Sands BE, Vermeire S, Travis SPL. Developing a standard set of patient-centred outcomes for inflammatory bowel disease-an international, cross-disciplinary consensus. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2018;12(4):408–418. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruemmele FM, Hyams JS, Otley A, Griffiths A, Kolho K-L, Dias JA, Levine A, Escher JC, Taminiau J, Veres G, Colombel JF, Vermeire S, Wilson DC, Turner D. Outcome measures for clinical trials in paediatric IBD: an evidence-based, expert-driven practical statement paper of the paediatric ECCO committee. Gut. 2015;64(3):438–446. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis, (2015).

- 33.Giannini EH, Ruperto N, Ravelli A, Lovell DJ, Felson DT, Martini A. Preliminary definition of improvement in juvenile arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(7):1202–9. 10.1002/1529-0131(199707)40:7<1202::AID-ART3>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis, (2006).

- 35.Gladman DD. Consensus exercise on domains in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005(64 Suppl 2):ii113–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Healy P, Helliwell PS, Fitzgerald O, Cauli A, Lubrano E, Krueger GG, van der Heijde D, Veale DJ, Kavanaugh A, Nash P, Ritchlin C, Taylor W, Strand V. Outcome measures in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(5):1159–1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Strand V, Healy P, Helliwell PS, Fitzgerald O, Gottlieb AB, Krueger GG, Nash P, Ritchlin CT, Taylor W, Adebajo A, Braun J, Cauli A, Carneiro S, Choy E, Dijkmans B, Espinoza L, van der Heijde D, Husni E, Lubrano E, McGonagle D, Qureshi A, Soriano ER, Zochling J. Consensus on a core set of domains for psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(5):1167–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orbai AM, de Wit M, Mease PJ, Callis Duffin K, Elmamoun M, Tillett W, Campbell W, FitzGerald O, Gladman DD, Goel N, Gossec L, Hoejgaard P, Leung YY, Lindsay C, Strand V, van der Heijde DM, Shea B, Christensen R, Coates L, Eder L, McHugh N, Kalyoncu U, Steinkoenig I, Ogdie A. Updating the Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA) Core Domain Set: a report from the PsA Workshop at OMERACT 2016. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(10):1522–1528. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.160904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orbai AM, de Wit M, Mease P, Shea JA, Gossec L, Leung YY, Tillett W, Elmamoun M, Callis Duffin K, Campbell W, Christensen R, Coates L, Dures E, Eder L, FitzGerald O, Gladman D, Goel N, Grieb SD, Hewlett S, Hoejgaard P, Kalyoncu U, Lindsay C, McHugh N, Shea B, Steinkoenig I, Strand V, Ogdie A. International patient and physician consensus on a psoriatic arthritis core outcome set for clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(4):673–680. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor WJ. Preliminary identification of core domains for outcome studies in psoriatic arthritis using Delphi methods. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl 2):ii110–ii112. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.030874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tillett W, Eder L, Goel N, De Wit M, Gladman DD, FitzGerald O, et al. Enhanced Patient Involvement and the Need to Revise the Core Set - Report from the Psoriatic Arthritis Working Group at OMERACT 2014. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(11):2198–2203. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aletaha D, Landewe R, Karonitsch T, Bathon J, Boers M, Bombardier C, Bombardieri S, Choi H, Combe B, Dougados M, Emery P, Gomez-Reino J, Keystone E, Koch G, Kvien TK, Martin-Mola E, Matucci-Cerinic M, Michaud K, O'Dell J, Paulus H, Pincus T, Richards P, Simon L, Siegel J, Smolen JS, Sokka T, Strand V, Tugwell P, van der Heijde D, van Riel P, Vlad S, van Vollenhoven R, Ward M, Weinblatt M, Wells G, White B, Wolfe F, Zhang B, Zink A, Felson D. Reporting disease activity in clinical trials of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: EULAR/ACR collaborative recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(10):1360–1364. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.091454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.EMA. Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. European Medicines Agency. 2017. Document number: CPMP/EWP/556/95 Rev. 2. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-clinical-investigation-medicinal-products-treatment-rheumatoid-arthritis_en.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb 2020.

- 44.FDA. Guidance for Industry Rheumatoid Arthritis: Developing Drug Products for Treatment - Draft guidance. US Food and Drugs Administration, 2013. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/86066/download. Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

- 45.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Chernoff M, Fried B, Furst D, Goldsmith C, Kieszak S, Lightfoot R, Paulus H, Tugwell P, Weinblatt M, Widmark R, James Williams H, Wolfe F. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary core set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. The Committee on Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(6):729–740. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Furst D, Goldsmith C, Katz LM, Lightfoot R, Paulus H, Strand V, Tugwell P, Weinblatt M, James Williams H, Wolfe F, Kieszak S. American College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(6):727–735. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.ICHOM. ICHOM Standard Set for Inflammatory Arthritis. 2018. International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement. Available from: https://ichom.org/files/medical-conditions/inflammatory-arthritis/inflammatory-arthritis-reference-guide.pdf. Accessed 14 Jan 2020.

- 48.Kirwan JR, Minnock P, Adebajo A, Bresnihan B, Choy E, de Wit M, Hazes M, Richards P, Saag K, Suarez-Almazor M, Wells G, Hewlett S. Patient perspective: fatigue as a recommended patient centered outcome measure in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(5):1174–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nikiphorou E, Mackie SL, Kirwan J, Boers M, Isaacs J, Morgan AW, Young A. Achieving consensus on minimum data items (including core outcome domains) for a longitudinal observational cohort study in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2017;56(4):550–555. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Radner H, Chatzidionysiou K, Nikiphorou E, Gossec L, Hyrich KL, Zabalan C, van Eijk-Hustings Y, Williamson PR, Balanescu A, Burmester GR, Carmona L, Dougados M, Finckh A, Haugeberg G, Hetland ML, Oliver S, Porter D, Raza K, Ryan P, Santos MJ, van der Helm-van Mil A, van Riel P, von Krause G, Zavada J, Dixon WG, Askling J. 2017 EULAR recommendations for a core data set to support observational research and clinical care in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(4):476–479. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tugwell P, Boers M. Developing consensus on preliminary core efficacy endpoints for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. OMERACT Comm J Rheumatol. 1993;20(3):555–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.EMA. Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. European Medicines Agency, 2015. Document number: EMA/CHMP/51230/2013 corr1. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-clinical-investigation-medicinal-products-treatment-systemic-lupus-erythematosus-lupus_en.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2020.

- 53.FDA. Guidance for Industry Systemic Lupus Erythematosus - Developing Medical Products for Treatment. US Food and Drugs Administration. 2010. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/71150/download. Accessed 08 Jan 2020.

- 54.Gordon C, Bertsias G, Ioannidis JP, Boletis J, Bombardieri S, Cervera R, et al. EULAR points to consider for conducting clinical trials in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(4):470–476. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.083022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liang MH, Schur P, Fortin P, St. Clair E W, E Balow J, Costenbader K, et al. The American College of Rheumatology response criteria for proliferative and membranous renal disease in systemic lupus erythematosus clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(2):421–432. doi: 10.1002/art.21625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smolen JS, Strand V, Cardiel M, Edworthy S, Furst D, Gladman D, Gordon C, Isenberg DA, Klippel JH, Petri M, Simon L, Tugwell P, Wolfe F. Randomized clinical trials and longitudinal observational studies in systemic lupus erythematosus: consensus on a preliminary core set of outcome domains. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(2):504–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strand V, Gladman D, Isenberg D, Petri M, Smolen J, Tugwell P. Endpoints: consensus recommendations from OMERACT IV. Lupus. 2000;9(5):322–327. doi: 10.1191/096120300678828424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruperto N, for the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials O, the Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group b, Ravelli A, for the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials O, the Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group b et al. Preliminary core sets of measures for disease activity and damage assessment in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus and juvenile dermatomyositis. Rheumatology. 2003;42(12):1452–1459. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ruperto N, Ravelli A, Oliveira S, Alessio M, Mihaylova D, Pasic S, Cortis E, Apaz M, Burgos-vargas R, Kanakoudi-tsakalidou F, Norambuena X, Corona F, Gerloni V, Hagelberg S, Aggarwal A, Dolezalova P, Saad CM, Bae SC, Vesely R, Avcin T, Foster H, Duarte C, HerliN T, Horneff G, Lepore L, Rossum M, Trail L, Pistorio A, Andersson-Gäre B, Giannini EH, Martini A, Pediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization (Printo), Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group (Prcsg) et al. The Pediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization/American College of Rheumatology provisional criteria for the evaluation of response to therapy in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus: prospective validation of the definition of improvement. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(3):355–363. doi: 10.1002/art.22002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bowman SJ, Pillemer S, Jonsson R, Asmussen K, Vitali C, Manthorpe R, Sutcliffe N, Contributors to and participants at the workshop Revisiting Sjogren’s syndrome in the new millennium: perspectives on assessment and outcome measures. Report of a workshop held on 23 March 2000 at Oxford, UK. Rheumatol (Oxford). 2001;40(10):1180–1188. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.10.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pillemer SR, Smith J, Fox PC, Bowman SJ. Outcome measures for Sjogren’s syndrome, April 10-11, 2003, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(1):143–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.EMA. Guideline on the development of new medicinal products for the treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. European Medicines Agency, 2018. Document number: CHMP/EWP/18463/2006 Rev.1. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-development-new-medicinal-products-treatment-ulcerative-colitis-revision-1_en.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

- 63.Colitis U. Clinical Trial Endpoints Guidance for Industry - Draft guidance. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heiligenhaus A, Foeldvari I, Edelsten C, Smith JR, Saurenmann RK, Bodaghi B, de Boer J, Graham E, Anton J, Kotaniemi K, Mackensen F, Minden K, Nielsen S, Rabinovich EC, Ramanan AV, Strand V, Multinational Interdisciplinary Working Group for Uveitis in Childhood Proposed outcome measures for prospective clinical trials in juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis: a consensus effort from the multinational interdisciplinary working group for uveitis in childhood. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(9):1365–1372. doi: 10.1002/acr.21674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.FDA. Guidance for Industry Rheumatoid Arthritis: Developing Drug Products for Treatment - Draft guidance. US Food and Drugs Administration. 2013. Document number: Revision 1. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/86066/download. Accessed 08 Jan 2020.

- 66.EMA. Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. 2017. Document number: CPMP/EWP/556/95 Rev. 2. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-clinical-investigation-medicinal-products-treatment-rheumatoid-arthritis_en.pdf. Accessed 04 Feb 2020.

- 67.EMA. Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. European Medicines Agency, 2015. Document number: EMA/CHMP/51230/2013 corr1. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-clinical-investigation-medicinal-products-treatment-systemic-lupus-erythematosus-lupus_en.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2020.

- 68.FDA. Guidance for Industry Systemic Lupus Erythematosus - Developing Medical Products for Treatment. US Food and Drugs Administration, 2010. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/71150/download. Accessed 08 Jan 2020.

- 69.EMA. Guideline on the development of new medicinal products for the treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. European Medicines Agency, 2018. Document number: CHMP/EWP/18463/2006 Rev.1. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-development-new-medicinal-products-treatment-ulcerative-colitis-revision-1_en.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2020.

- 70.FDA. Ulcerative Colitis: Clinical Trial Endpoints Guidance for Industry - Draft guidance. US Food and Drugs Administration, 2016. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/99526/download. Accessed 20 Jan 2020.

- 71.US Government. 21st Century Cures Act. 114th Congress of the United States of America. Document number: HR 34. 2016. Available from: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-114hr34enr/pdf/BILLS-114hr34enr.pdf. Accessed 14 Jan 2020.

- 72.Kluetz PG, O'Connor DJ, Soltys K. Incorporating the patient experience into regulatory decision making in the USA, Europe, and Canada. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(5):e267–ee74. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mavris M, Furia Helms A, Bere N. Engaging patients in medicines regulation: a tale of two agencies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(12):885–886. doi: 10.1038/d41573-019-00164-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Calvert MJ, O'Connor DJ, Basch EM. Harnessing the patient voice in real-world evidence: the essential role of patient-reported outcomes. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(10):731–732. doi: 10.1038/d41573-019-00088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: COMET database search

Additional file 2: Characteristics of included publications

Additional file 3: Outcome measures proposed across inflammatory conditions

Data Availability Statement

Relevant data has been provided in tables and additional files.