Abstract

Since the beginning of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) pandemic, it has been clear that effective methods for the diagnosis of Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) are the key tools to control its epidemic. The current gold standard for diagnosing COVID‐19 is the real‐time quantitative reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR), which is a sensitive and specific method to detect SARS‐CoV‐2. Other RNA‐based methods include RNA sequencing (RNA‐seq), droplet digital reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (ddRT‐PCR), reverse transcription loop‐mediated isothermal amplification (RT‐LAMP), and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR). The serological testing of antibodies (IgM and IgG), nanoparticle‐based lateral‐flow assay, and enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) can be used to enhance the detection sensitivity and accuracy. Because antibodies are usually detected a week after the onset of symptoms, these tests are used to assess the overall infection rate in the community. Sine the fact that healthcare varies from country to country across the world, different types of diagnosing COVID‐19 imaging technologies including chest computed tomography (CT), chest radiography, and lung ultrasound are used in different degrees. Besides, the pooling test is an important public health tool to reduce cost and increase testing capacity in low‐risk area, while artificial intelligence (AI) may aid to increase the diagnostic efficiency of imaging‐based methods. Finally, depending on the type of samples and stages of the disease, a combination of information on patient demographics and histories, clinical symptoms, results of molecular and serological diagnostic tests, and imaging information is highly recommended to achieve adequate diagnosis of patients with COVID‐19.

Keywords: COVID‐19, diagnosis, reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction, SARS‐CoV‐2

Methods for the diagnosis of COVID‐19. 1. Summarizes the currently commonly used methods for diagnosing SARS‐CoV‐2. 2. The current gold standard for diagnosing COVID‐19 is qRT‐PCR. Other RNA‐based methods include RNA‐seq, ddRT‐PCR, RT‐LAMP, and CRISPR. The serological testing of antibodies (IgM and IgG), nanoparticle‐based lateral‐flow assay, and enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) can be used to enhance the detection sensitivity and accuracy. 3. The pooling test is an important public health tool to reduce cost and increase testing capacity in low‐risk area, while artificial intelligence (AI) may aid to increase the diagnostic efficiency of imaging‐based methods. 4. Depending on the type of samples and stages of the disease, a combination of information on patient demographics and histories, clinical symptoms, results of molecular and serological diagnostic tests, and imaging information is highly recommended to achieve adequate diagnosis of patients with COVID‐19.

1. INTRODUCTION

At the end of December 2019, there was a novel respiratory disease outbreak in Wuhan, China. In subsequent studies, this disease was named Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and proven to be caused by a novel coronavirus named Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). Due to convenient transportation and frequent international travel, COVID‐19 epidemic quickly spread to almost all countries in the world. Until November 2021, more than 247 million people are diagnosed and 5.01 million patients’ died due to COVID‐19. 1 Although vaccines and effective treatments have been developed, there are more than 35 thousand patients being diagnosed each day until now.

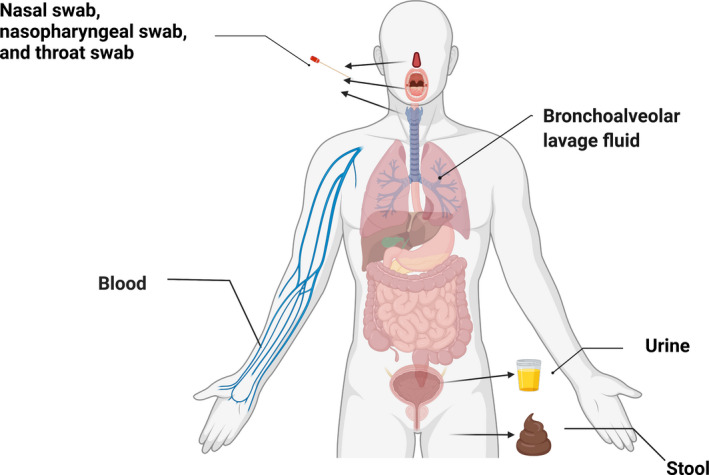

Researchers have developed several methods to diagnose the patients with COVID‐19. The nucleic acids, antigen, and antibodies of SARS‐CoV‐2 have been proved to exist in patients’ body fluids and excreta including blood, stool, urine, and saliva (Figure 1). Various sampling methods have been widely used during the epidemic. The swab testing methods including nasal swab, nasopharyngeal swab, and throat swab are convenient and fast methods while maintaining accuracy, suitable for large‐scale investigation. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7

FIGURE 1.

Samples for the diagnosis of COVID‐19. The manikin was created with BioRender.com

The rapid identification of infected patients from the crowd and isolating them have played an important role in control COVID‐19. Thousands or even millions of people have been tested in some locations. However, large‐scale general survey will consume a lot of medical resources and funds. To reduce the cost of medical resources, the pooled testing method was developed under the guidance of medical statistics to detect patients extensively and quickly. 4 , 5

There are many methods widely used for COVID‐19 diagnosis. They can be divided into four categories according to the detected targets (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

The categories of COVID‐19 diagnostic methods

| Target | Method | Advantage | Disadvantage | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA | RNA sequencing | High sensitivity, high specificity, and high accuracy |

Long testing time, high equipment requirements, and high personnel requirements |

8 |

| qRT‐PCR | 2, 16 | |||

| ddRT‐PCR | 18 | |||

| RT‐LAMP | 19, 20 | |||

| CRISPR | 16 | |||

| Antigen and Antibody | IgM and IgG |

High sensitivity, high specificity, and can detect recovered people |

Slow detection speed, and cumbersome steps | 9, 10, 11 |

| Nanoparticle‐based lateral‐flow assay | 12 | |||

| ELISA | 13 | |||

| Rapid antigen detection | 26 | |||

| Imaging | Chest X‐ray imaging | Low risk of infection, and low equipment equirements |

Need professional to analysis, difficult to detect mild symptoms |

35 |

| Chest CT scan | 31 | |||

| Lung ultrasound imaging | 8, 38, 39 | |||

| Blood | Blood cell counting | Low equipment requirements |

Low sensitivity, and low specificity |

19, 41 |

| Measurement of blood biochemistry parameters | 41 | |||

| Assistant technology | Pooling test | Reduce the cost | Need to be combined with other detection methods | 16, 42, 43, 44 |

| Artificial intelligence | Reduce the need for professionals | 36 | ||

| Omics analysis | Can study disease mechanisms | 45, 46 |

The most used techniques for rapidly detecting virus mainly fall into two categories: Nucleic acid‐based detection and antigen–antibody‐based immunoassay. Single‐sense RNA is the genetic material of SARS‐CoV‐2; and the detection of the unique characteristic nucleic acid sequence can identify the virus. 5 , 8 The antigens generated by virus can stimulate human body's immune response and then antibodies are produced in the body; therefore, specific antigens or antibodies can be used for the diagnosis of patients with COVID‐19. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13

2. RNA‐BASED METHODS

The technologies used for the detection of nucleic acid in COVID‐19 include RNA sequencing (RNA‐seq), real‐time quantitative reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR), droplet digital reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (ddRT‐PCR), reverse transcription loop‐mediated isothermal amplification (RT‐LAMP), and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR).

2.1. RNA sequencing

Despite the high cost and highly dependent on equipment, RNA‐seq has been firstly used to diagnose patients with COVID‐19 through bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and then identified a new RNA virus, which complete viral genome has 29,903 nucleotides and is most closely related Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)‐like coronaviruses. 14 More importantly, RNA‐seq is the most useful method for finding SARS‐CoV‐2 variants, which is a new concern during the COVID‐19 epidemic.

2.2. qRT‐PCR

Currently, qRT‐PCR is a standard method for the diagnosis of COVID‐19. 15 Samples are mostly collected via nasopharyngeal swab or oropharyngeal swab. The qRT‐PCR test provides a sensitive and specific method to detect SARS‐CoV‐2 and considered the current gold standard for diagnosing COVID‐19. 2 However, the insufficient RNA for early infection may give false negatives, and high requirements for equipment and operators limit its large‐scale use. 16

2.3. ddRT‐PCR

Due to preanalytical and technical limitations, samples with low viral load are often misdiagnosed as false‑negative samples using qRT‐PCR method. 17 To improve this situation, ddRT‐PCR using droplet technology to improve the sensitivity and specificity. 18 Despite the high requirements of equipment, Suo et al. proved that ddRT‐PCR could reduce the false‐negative reports when complemented with qRT‐PCR. 18 The ddRT‐PCR technology is the third‐generation RT‐PCR method and does not require a standard curve to achieve absolute quantitative detection of RNA. It greatly improves the accuracy of diagnosis, especially for the detection of samples with low copy SARS‐CoV‐2.

2.4. RT‐LAMP

LAMP is a new isothermal nucleic acid amplification method with great efficiency. It can be used to amplify RNAs and DNAs with high specificity and sensitivity because of its exponential amplification feature and six particular target sequences diagnosed by four separate primers. 19 The LAMP technology does not need high‐priced equipment and reagents with the advancement of saving time. Furthermore, it is very easy to observe the results for using gel electrophoresis method. So, the use of LAMP method may decrease the cost of SARS‐CoV‐2 detection. Several LAMP‐based strategies for the detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 have been developed and performed in clinical diagnosis. LAMP method uses four to six different primers binding under the Bst DNA polymerase to the distinct sequences. Within one hour and under the constant temperature (60–65°C), the templet can be amplified to 109~1010 times. Besides the fast and convenient, the results of LAMP can be easily judged by the turbidity or color of the test solution. 20 As a result, it is a new choice for the detection of SARS‐CoV‐2.

2.5. CRISPR

The novel detection method using enzyme Cas13a/C2c2 based on clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) is a fast, cheap, and highly sensitive diagnostic tool. 14 Under the guidance of CRISPR RNA (crRNA), the Cas13a detects the target RNA sequence and becomes active state. When the target RNA sequence is cut, it will emit a fluorescent signal. This method is easy to operate and can be tested quickly without the need for professionals, reducing the shortage of professionals in the large‐scale fight against COVID‐19. 21

Besides the above methods, the other RNA‐based method for the detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 is microarray. Microarray is a rapid and high‐throughput method for the diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2. Complementary DNA (cDNA) is first produced by coronavirus RNA templates. Then, the targets are hybridized to the probes. Free DNAs are removed by washing the solution. Finally, probes identify SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA. 19 , 22

3. IMMUNOLOGIC METHODS

The immunologic methods for the diagnosis of patients with COVID‐19 include the detection of antigens and the detection of antibodies. Spike protein and nucleocapsid protein (N‐protein) are the biomarkers of the SARS‐CoV‐2 antigens. 12 SARS‐CoV‐2 antigens can be collected in nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, sputum, and feces. However, compared with the detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 antigens, the detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies is more common.

The immunologic methods can detect recovered patients with COVID‐19. 22 Four kinds of methods including rapid antigen detection, antibody detection, nanoparticle‐based lateral‐flow assay, and enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) are widely used in the diagnosis of COVID‐19.

3.1. Rapid antigen detection

The variant of surface proteins causes the difference between infectiousness and pathogenicity. 23 , 24 Rapid antigen detection method uses specific monoclonal antibodies to detect the spike and nucleocapsid proteins of SARS‐CoV‐2 through antigen–antibody interaction. 2 , 25 Because of the low sensitivity and high false‐negative rate, the rapid antigen detection method is rarely used to diagnose COVID‐19 patient and only used as adjunct to other test methods. 26

3.2. Antibody detection method

The antibody detection methods are the methods by detecting the immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody levels to identify COVID‐19 patients. 9 , 10 Xie et al. found that both IgG and IgM increase during first week after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. 10 IgG level will be maintained at a high level for a long period; and IgM will be reduced to near‐background levels after 2 weeks. 10 Xie et al. confirmed that IgM‐IgG test is an accurate and sensitive diagnostic method. 11 Moreover, a combination of RNA and IgM‐IgG testing may be a more sensitive and accurate approach for the diagnosis COVID‐19 patients. 11

3.3. Nanoparticle‐based lateral‐flow assay

Nanoparticle‐based lateral‐flow assay is widely recognized for its simplicity, fastness, and high accuracy in the diagnosis of COVID‐19 patients. 12 Huang et al. coated SARS‐CoV‐2 nucleoprotein on an analytical membrane for sample capture and used antihuman IgM conjugated with AuNPs to form the detecting reporter. 12 They found that within a short time of 15 min and only a tiny serum usage of 10–20 μl, the test result showed a high sensitivity of 100% and a high specificity 93.3%, respectively. 12

3.4. ELISA

ELISA is an assay technique based on microwell plate. 13 The antiviral antibodies of SARS‐CoV‐2 can be detected qualitatively or quantitatively through colorimetric or fluorescent response in 1–5 h. 13 , 27 ELISA can test multiple samples each time and can automate detection with large throughput, conducive to the detection of COVID‐29. 22

4. IMAGING

In addition to technologies involving RNA, antigens, and antibodies, the changes in the lungs and respiratory tract make imaging diagnosis of COVID‐19 patients possible. Healthcare varies from country to country across the globe, so different types of diagnosing COVID‐19 imaging technology including chest computed tomography (CT), chest radiography, and lung ultrasound are used in different degrees. Several studies showed that SARS‐CoV‐2 mainly involved bilateral lungs, and that the imaging manifestations were mainly affected by the patient's age, disease severity, duration, and immune status. 7 , 28 Patients having fever and cough, chest discomfort, and difficulty in breathing are usually diagnosed by imaging examinations.

4.1. Chest Computed Tomography (CT)

Computed tomography equipment is widespread worldwide and the scan process is relatively simple and quick. These advantages make it a rapid screening method for suspected patients with COVID‐19. The chest CT imaging of COVID‐19 is similar to that of influenza. 29 The typical imaging of CT in COVID‐19 patients is ground‐glass opacities (GGO), commonly in the peripheral and lower lobes, bilateral multiple lobular and subsegmental areas of consolidation. 28 The same conclusion was reported by Chung et al. 30 Besides, Jin et al. described CT images of five stages in COVID‐19 patients according to the infection time and body condition. The five stages are ultra‐early stage, early stage, rapid progression stage, consolidation stage, and dissipation stage. 7

Chest CT is one of the main methods used in the diagnosis of COVID‐19 and in evaluating the situation of patients. This is because CT has a high sensitivity of 97%. 31 It is ideal for triage and screening. Although CT has high sensitivity, it has low specificity of 25%. 31 In some patients, CT imaging is not typical, which may also be found in non‐infectious and infectious origin, such as other viral pneumonia. However, its high sensitivity makes it very important.

To adapt to huge demand for CT examinations and the need for profound decisions, some groups have proposed the elaboration of CT structured reports. 32 , 33 It has been widely used in Radiological Society of North America. 32

4.2. Chest radiography

Chest radiography, also well known as chest X‐ray imaging, has an important role in the diagnosis of diseases, especially in field hospitals and intensive care unit (ICU) for its easy availability and cost. 34 Compared with CT, chest radiography in the diagnosis of infectious disease such as COVID‐19 takes shorter time and less manpower to sterilize before and after examination to avoid cross‐infection. 35

However, chest X‐ray has a lower sensitivity of 59%. 35 Representative radiographic imaging is irregular, reticular, patchy lung opacities with bilateral distribution, more common in the periphery and lower pulmonary fields. 34 Now, deep learning model has been used to diagnose COVID‐19 using X‐ray automatically to increase the efficiency of screening and diagnosis. 36

4.3. Lung ultrasound

Different from chest CT and chest radiography, lung ultrasound (LUS) has no radiation, so it is more suitable for children and pregnant women to screen out and for the diagnosis of COVID‐19. 37 Besides, LUS can be performed anywhere, such as emergency department, operating room, community, suspected patient's home, and various levels of medical care. LUS is small, miniaturized hand‐held ultrasound devices, the size just like a smart phone or tablet. 37 Another advantage of LUS is that it can be used to examine complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), pleural effusion or pneumothorax and support treatment, especially in patients who are extremely weak and unable to move in ICU.

The sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy of LUS for the severity of COVID‐19 pneumonia have been reported. 38 A study showed that LUS had lower specificity in the diagnosis of COVID‐19 compared with chest CT. 8 As a result, an Italian consensus proposed a standardization of the use of LUS for COVID‐19 patients. 39

Interstitial pneumonia is the most common clinical manifestation of COVID‐19. So, LUS can find interstitial pneumonia‐related imaging including irregular pleural line, B‐lines, and small consolidations. 40 But as we know, gas in lung leads to ultrasonic attenuation, and LUS only examines pleural and peripheral pulmonary lesions, so it is not widely used for lung assessment. More studies about application of LUS in the diagnosis of COVID‐19 are needed.

5. BLOOD TEST

The blood tests are usually nonspecific, but could help for the diagnosis of patients with COVID‐19. 19 A complete blood count typically showed that 25% and 63% patients had varying degrees of leucopenia and lymphopenia, respectively. 19 , 41 For critical patients with COVID‐19, the D‐dimer level, aspartate aminotransferase level, and hypersensitive troponin I have been found to be abnormally increased. 41 The abnormal blood test results are nonspecific and need to be confirmed by other diagnostic methods.

6. ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGY

6.1. Pooling test

In low‐risk area, the proportion of people infected is low and most test results are negative. 16 It is not necessary to do a complete test for each tester at the first time. Multiple samples to be tested can be pooled together because the test method has sufficient sensitivity to detected abnormal samples mixed with normal samples. After screening, the abnormal group is separated and do full set of testing for each sample. 16 , 42 , 43 , 44 Its obvious advantage is that the pooling test is an important public health tool to reduce workload and contain reagent costs, increase testing capacity, and fast isolate suspected patients and their close contacts.

6.2. Artificial intelligence

The imaging examinations are relatively cheap and have low equipment requirements while requiring professional analysis to get accurate results. A large number of experienced medical workers need to be involved in the diagnosis of patients with COVID‐19 when the epidemic breaks out. 36 To increase the diagnostic efficiency, some researchers have used artificial intelligence (AI) to solve this problem. 15 , 32 , 36 The images of patients share some same formats and can be transferred to digitizing datasets. 15 Then the datasets are used to train the deep learning architectures like convolutional neural networks. After training, the algorithm can automatically analyze diagnostic images. The speed and accuracy even exceed the performance of human experts in medical image diagnosis sometimes. 32 , 36

6.3. Omics analysis

The patients with COVID‐19 have been observed for symptoms including fever, sepsis, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, respiratory failure, and multiorgan injury. 45 Using RNA sequencing and mass spectrometric technologies, researchers can identify and quantify various proteins, RNAs, metabolites, and lipids from patients with COVID‐19. 46 Through omics analysis, researchers can shed light on disease mechanisms and evaluate the effects of different drugs and treatments at molecular levels. 45 , 46

7. CONCLUSION

Several methods including RNA‐based detections, immunologic measurements, and imaging examinations have been used in the diagnosis of patients with COVID‐19. They are playing very important roles in the control of SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic disease. Novel technologies, such as AI technology and pooling test, can greatly reduce the cost of funds and professionals. More importantly, more than 6 billion doses of vaccine have been administered to prevent the sensitive people to be infected. We believe that through the joint efforts of global researchers and medical workers, COVID‐19 gradually will become preventable and controllable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jie Guo, Jiaxin Ge, and Yanan Guo collected information; Jie Guo and Jiaxin Ge analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; Jie Guo designed the study; Jie Guo gave the final approval of the manuscript for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

None.

Guo J, Ge J, Guo Y. Recent advances in methods for the diagnosis of Corona Virus Disease 2019. J Clin Lab Anal.2022;36:e24178. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24178

Funding information

This work was supported by a grant from the K. C. Wong Magna Fund in Ningbo University

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. WHO Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed November 1,2021

- 2. Boger B, Fachi MM, Vilhena RO, Cobre AF, Tonin FS, Pontarolo R. Systematic review with meta‐analysis of the accuracy of diagnostic tests for COVID‐19. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(1):21‐29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. To KK, Sridhar S, Chiu KH, et al. Lessons learned 1 year after SARS‐CoV‐2 emergence leading to COVID‐19 pandemic. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2021;10(1):507‐535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dash GC, Rout UK, Nanda RR, et al. Pooled testing for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in an automated high‐throughput platform. J Clin Lab Anal. 2021;35(7):e23835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bloom JS, Sathe L, Munugala C, et al. Massively scaled‐up testing for SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA via next‐generation sequencing of pooled and barcoded nasal and saliva samples. Nat Biomed Eng. 2021;5(7):657‐665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wolters F, van de Bovenkamp J, van den Bosch B, et al. Multi‐center evaluation of cepheid xpert(R) xpress SARS‐CoV‐2 point‐of‐care test during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. J Clin Virol. 2020;128:104426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jin YH, Cai L, Cheng ZS, et al. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version). Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen X, Tang Y, Mo Y, et al. A diagnostic model for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) based on radiological semantic and clinical features: a multi‐center study. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(9):4893‐4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bryant JE, Azman AS, Ferrari MJ, et al. Serology for SARS‐CoV‐2: apprehensions, opportunities, and the path forward. Sci Immunol. 2020;5(47):eabc6347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hou H, Wang T, Zhang B, et al. Detection of IgM and IgG antibodies in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Transl Immunology. 2020;9(5):e01136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xie J, Ding C, Li J, et al. Characteristics of patients with coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) confirmed using an IgM‐IgG antibody test. J Med Virol. 2020;92(10):2004‐2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang C, Wen T, Shi FJ, Zeng XY, Jiao YJ. Rapid detection of IgM antibodies against the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus via colloidal gold nanoparticle‐based lateral‐flow assay. ACS Omega. 2020;5(21):12550‐12556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carter LJ, Garner LV, Smoot JW, et al. Assay techniques and test development for COVID‐19 diagnosis. ACS Cent Sci. 2020;6(5):591‐605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265‐269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alsharif W, Qurashi A. Effectiveness of COVID‐19 diagnosis and management tools: a review. Radiography (Lond). 2021;27(2):682‐687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Qin XS, Gao P, Zhang ZJ, et al. A low‐cost and high‐efficiency 10‐in‐1 test for the polymerase chain reaction‐based screening of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in low‐risk areas. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001627online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Falzone L, Musso N, Gattuso G, et al. Sensitivity assessment of droplet digital PCR for SARS‐CoV‐2 detection. Int J Mol Med. 2020;46(3):957‐964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Suo T, Liu X, Feng J, et al. ddPCR: a more accurate tool for SARS‐CoV‐2 detection in low viral load specimens. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):1259‐1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mohamadian M, Chiti H, Shoghli A, Biglari S, Parsamanesh N, Esmaeilzadeh A. COVID‐19: virology, biology and novel laboratory diagnosis. J Gene Med. 2021;23(2):e3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schmid‐Burgk JL, Gao L, Li D, et al. Highly parallel profiling of Cas9 variant specificity. Mol Cell. 2020;78(4):794‐800.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Broughton JP, Deng X, Yu G, et al. CRISPR‐Cas12‐based detection of SARS‐CoV‐2. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(7):870‐874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Majumder J, Minko T. Recent developments on therapeutic and diagnostic approaches for COVID‐19. AAPS J. 2021;23(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weisblum Y, Schmidt F, Zhang F, et al. Escape from neutralizing antibodies by SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein variants. Elife. 2020;9:e61312. doi: 10.7554/eLife.61312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang L, Jackson CB, Mou H, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 spike‐protein D614G mutation increases virion spike density and infectivity. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chaimayo C, Kaewnaphan B, Tanlieng N, et al. Rapid SARS‐CoV‐2 antigen detection assay in comparison with real‐time RT‐PCR assay for laboratory diagnosis of COVID‐19 in Thailand. Virol J. 2020;17(1):177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mak GC, Cheng PK, Lau SS, et al. Evaluation of rapid antigen test for detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 virus. J Clin Virol. 2020;129:104500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xiang J, Yan M, Li H, et al. Evaluation of enzyme‐linked immunoassay and colloidal gold‐immunochromatographic assay kit for detection of novel coronavirus (SARS‐Cov‐2) causing an outbreak of pneumonia (COVID‐19). medRxiv. 2020. 10.1101/2020.02.27.20028787. 2020.02.27.20028787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu YJ, et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Onigbinde SO, Ojo AS, Fleary L, Hage R. Chest computed tomography findings in COVID‐19 and influenza: a narrative review. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:6928368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chung M, Bernheim A, Mei X, et al. CT imaging features of 2019 novel Coronavirus (2019‐nCoV). Radiology. 2020;295(1):202‐207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT‐PCR testing for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E32‐E40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Simpson S, Kay FU, Abbara S, et al. Radiological society of North America Expert consensus statement on reporting chest CT findings related to COVID‐19. endorsed by the society of thoracic radiology, the American College of radiology, and RSNA ‐ secondary publication. J Thorac Imaging. 2020;35(4):219‐227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prokop M, van Everdingen W, van Rees VT, et al. CO‐RADS: a categorical CT assessment scheme for patients suspected of having COVID‐19‐definition and evaluation. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E97‐E104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wong HYF, Lam HYS, Fong AH, et al. Frequency and distribution of chest radiographic findings in patients positive for COVID‐19. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E72‐E78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M, et al. Chest CT findings in Coronavirus Disease‐19 (COVID‐19): relationship to duration of infection. Radiology. 2020;295(3):200463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pandit MK, Banday SA, Naaz R, Chishti MA. Automatic detection of COVID‐19 from chest radiographs using deep learning. Radiography (Lond). 2021;27(2):483‐489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Buda N, Segura‐Grau E, Cylwik J, Welnicki M. Lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of COVID‐19 infection ‐ a case series and review of the literature. Adv Med Sci. 2020;65(2):378‐385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lu W, Zhang S, Chen B, et al. A clinical study of noninvasive assessment of lung lesions in patients with coronavirus disease‐19 (COVID‐19) by bedside ultrasound. Ultraschall Med. 2020;41(3):300‐307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Soldati G, Smargiassi A, Inchingolo R, et al. Proposal for international standardization of the use of lung ultrasound for patients with COVID‐19: a simple, quantitative, reproducible method. J Ultrasound Med. 2020;39(7):1413‐1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Peng Q‐Y, Wang X‐T, Zhang L‐N. Findings of lung ultrasonography of novel corona virus pneumonia during the 2019–2020 epidemic. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(5):849‐850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Polvere I, Silvestri E, Sabatino L, et al. Sample‐pooling strategy for SARS‐CoV‐2 detection among students and staff of the University of Sannio. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(7):1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Martin A, Storto A, Le Hingrat Q, et al. High‐sensitivity SARS‐CoV‐2 group testing by digital PCR among symptomatic patients in hospital settings. J Clin Virol. 2021;141:104895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Giron‐Perez DA, Ruiz‐Manzano RA, Benitez‐Trinidad AB, et al. Saliva pooling strategy for the large‐scale detection of SARS‐CoV‐2, through working‐groups testing of asymptomatic subjects for potential applications in different workplaces. J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63(7):541‐547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shu T, Ning W, Wu D, et al. Plasma proteomics identify biomarkers and pathogenesis of COVID‐19. Immunity. 2020;53(5):1108‐1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Overmyer KA, Shishkova E, Miller IJ, et al. Large‐scale multi‐omic analysis of COVID‐19 severity. Cell Syst. 2021;12(1):23‐40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.