Abstract

Quantum dots (QDs) are nanometer scale fluorescent semiconductors that are increasingly used as labeling tools in biological research. These nanoparticles have physical properties, such as high quantum yield and resistance to photobleaching, that make them attractive molecular probes for tracking hematologic cells. Here, we show that QDs attached to a transporter protein effectively label all hematologic cells tested, including cell lines and malignant and non-malignant patient samples. We demonstrate that dividing cells can be tracked through at least four cell divisions. In leukemic cell lines, some cells remain labeled for 2 weeks. We show that QDs can be used to follow cells as they differentiate. QDs are seen in monocyte-like and neutrophil-like progeny of labeled HL-60 myeloblasts exposed to Vitamin D analogues and DMSO, respectively. QDs are also observed in monocytes generated from labeled CD34+ cells. In addition, QDs attached to streptavidin can target cells with differing cell surface markers, including CD33. In summary, QDs have the ability to bind to specific cells of interest, be taken up by a diverse range of hematologic cells, and followed through many divisions and through differentiation. These results establish QDs as extremely useful molecular imaging tools for the study of hematologic cells.

Keywords: Nanotechnology, Cell tracking, Hematopoiesis, Fluorescence microscopy

1. Introduction

Many questions in hematology, particularly in the area of hematopoiesis, can only be answered by labeling a cell of interest and assessing potential descendant cells. Currently available labeling systems have several shortcomings. Creating cell lines that express fluorescent proteins can be laborious, and this process generally cannot be utilized for studying patient samples. Conventional fluorescent organic dyes have small Stokes shifts (distance between excitation and emission peaks). So, excitation and emission filters must be of similar wavelength, resulting in reduced detection sensitivity and difficulty distinguishing dye fluorescence from cellular autofluorescence. The emission spectrum of conventional dyes is often broad, limiting the ability to use multiple fluorophors in a single assay. In addition, conventional dyes photobleach, often in a matter of seconds, compromising the ability to view the same region repeatedly or over time.

Quantum dots have recently been utilized as fluorescent tags for in vivo and in vitro labeling experiments [1–20]. They can be tailored, through control of size, composition, and shape, to provide broad spectral coverage with symmetric narrow emission profiles. Generally, larger particles emit light at longer wavelengths. The most commonly used QDs are composed of a CdSe core surrounded by a ZnS shell. Most QDs are spheres less than 10 nm in diameter, placing them on a scale of biological molecules. Due to their continuous absorption band, QDs are efficiently excited at shorter wavelengths than conventional dyes, improving detection sensitivity and shifting QD signals to a spectral region where autofluorescence is reduced. In addition, when combined with narrow emission peaks, the broad absorption profile allows simultaneous excitation of QDs of multiple colors for multiplex labeling.

The very large extinction coefficient of QDs (5 × 105 to 5 × 106 M−1 cm−1) make them very bright (high quantum yield) fluorescent probes. As demonstrated in several applications, these nanocrystals are also significantly more stable emitters than conventional dyes (low photobleaching), and are thus well-suited for continuous tracking studies over long periods of time [21].

Quantum dots are hydrophobic. To disperse in solution, the surface chemistry must be modified to render them hydrophilic. Without further modifications, QDs are not endocytosed, limiting their use in biological experiments to studies using electroporation. With chemical modification, QDs can be attached to molecules that allow biologic specificity. For instance, commercially available QDs are attached to secondary antibodies or streptavidin. In addition, commercially available cell labeling kits contain QDs attached to proteins that are non-specifically endocytosed [22,23]. Newer kits also allow attachment of QDs to specific antibodies or nucleic acids [24] and the potential exists to use these molecules for in situ hybridization. Despite all of this progress in the field, QDs have been used little in the field of hematology.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell lines and cell culture

The KG-1 cell line was established in our laboratory [25] and the HL-60 cell line was provided by Robert Gallo of the University of Maryland. The SUDHL-16 cell line was from Alan Epstein. All three cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 50 IU/ml penicillin and 50 mg/ml streptomycin (RPMI).

2.2. Preparing primary samples

Human bone marrow samples were obtained from the Pathology Department at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center with approval of the institutional review board (IRB). Mononuclear cells were separated via ficoll gradient and non-adherent cells were removed as previously described [26]. Murine bone marrow was prepared in the same manner after euthanizing mice and extracting bone marrow from the femurs. Human umbilical cord blood was obtained under an IRB approved protocol at Childrens Hospital, Los Angeles. CD34+ cells were enriched from cord blood by ficoll gradient followed by magnetic bead separation using the MACS system (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). CD34+ cells were further purified from this enriched population by staining with FITC labeled anti-HPCA-2 (CD34) (Becton Dickenson, San Jose, CA) and sorting by FACS.

2.3. Labeling cells with quantum dots

Q-tracker 565 cell labeling kit and Q-tracker 655 cell labeling kit were purchased from the Quantum Dot Corporation (Hayward, CA). 5 × 105 to 1 × 106 cells in 200 μl of the appropriate growth media containing 10% FCS were added to wells with 1 μl of Q-tracker reagent A and 1 μl of reagent B. The cells were incubated for 10 h at 37 μC and then washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

2.4. Imaging quantum dot labeled fixed cells

Slides were prepared by performing cytospins and fixing in 100% methanol. Slides from the differentiation assays were stained with Wright-Giemsa, and slides for sorting experiments were stained with Giemsa. Imaging was performed using a BH2-RFCA fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) using a 100 W mercury lamp. The excitation filter was 425DF45, the dichroic was 475DCLP and the emission filters were 655WB20 and 565WB20, all from Omega Optical (Brattleboro, VT). Images were captured and analyzed with a Magnafire digital camera (Olympus, Melville, NY). Exposure times were one minute for fluorescent images, except for the Q-tracker 565 labeled KG-1 with minimal white light (five seconds), and monocytes derived from labeled CD34+ cells (3 min).

2.5. Imaging quantum dot labeled live cells

Live cell imaging was conducted using Zeiss Axiovert 200 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging Inc., Thornwood, NY) with 40× and 63× water-immersion objectives. Images were obtained using AxisCam MRm (Carl Zeiss Microimaging Inc., Thornwood, NY). Z-stack images were taken from the top to the bottom of cells and three-dimensional images were reconstructed after deconvolution using Axiovision software (Carl Zeiss Microimaging Inc., Thornwood, NY). The excitation filter and dichroic for the live cell image were the same as in the fixed cells, and the emission filters were 565WB20 (Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT) and 580 nm long pass. All images were processed using Adobe Photoshop 7.0. The only operations performed using this software were layering, cropping and adjusting brightness and contrast.

2.6. Labeling cell membrane with PKH26

1 × 107 KG-1 cells were labeled with PKH26 as previously reported [27]. CD34+ cells were treated the same way, except that the initial cell number was approximately 1 × 106. In all experiments, PKH26 staining directly preceded labeling with QDs. After staining with PKH26 and labeling with QDs, a narrow band at the midpeak of PKH26 staining was isolated by FACS, and these cells were cultured to track cell divisions as previously described [28].

2.7. Differentiation assays

After labeling with Q-trackers, HL-60 cells were grown in RPMI alone or with either 1 × 10−7 M 1,25(OH)2 Vitamin D3 or 1.25% DMSO (v/v). After labeling with Q-trackers, CD34+ cells were grown in X-Vivo 15 (Cambrex Corporation, East Rutherford, New Jersey) with 5% FCS, 5ng/ml IL-3, 20 ng/ml SCF, 50 ng/ml GM-CSF ± 50 ng/ml G-CSF.

2.8. FACS analysis and cell sorting

All cells were sorted by FACStar Plus (Becton Dickenson, San Jose, CA) or MoFlo (Dako Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA). All analyses of cells were performed with FACScan (Becton Dickenson, San Jose, CA) after washing cells in PBS and resuspending in 1% paraformaldehyde. Number of cell divisions based on PKH26 staining was analyzed using the Modfit software (Verity Software, Topsham, ME).

2.9. Labeling with biotinylated anti-CD33 antibody and streptavidinated QDs

A 17.5 μl of biotinylated anti-CD33 antibody (Caltag, Burlingame, CA) and 7 μl of Qdot 585 Streptavidin Conjugate (QD-SA) from the Quantum Dot Corporation (Hayward, CA) were placed in 150.5 μl of PBS with 2% FCS at 4μC for 2h. 50 μl of this combination was added to 5 × 105 SUDHL-16 and HL-60 cells in 100 μl of PBS with 2% FCS. Control wells used 7 μl of (QD-SA) in 168 μl of PBS with 2% FCS and no anti-CD33 antibody. All cells were incubated with the QD-SA solution for 30 min. They were then washed in PBS with 2% FCS three times and placed in 1% paraformaldehyde. FACS analysis was subsequently performed.

3. Results

3.1. Labeling of hematologic cells and imaging with fluorescence microscopy

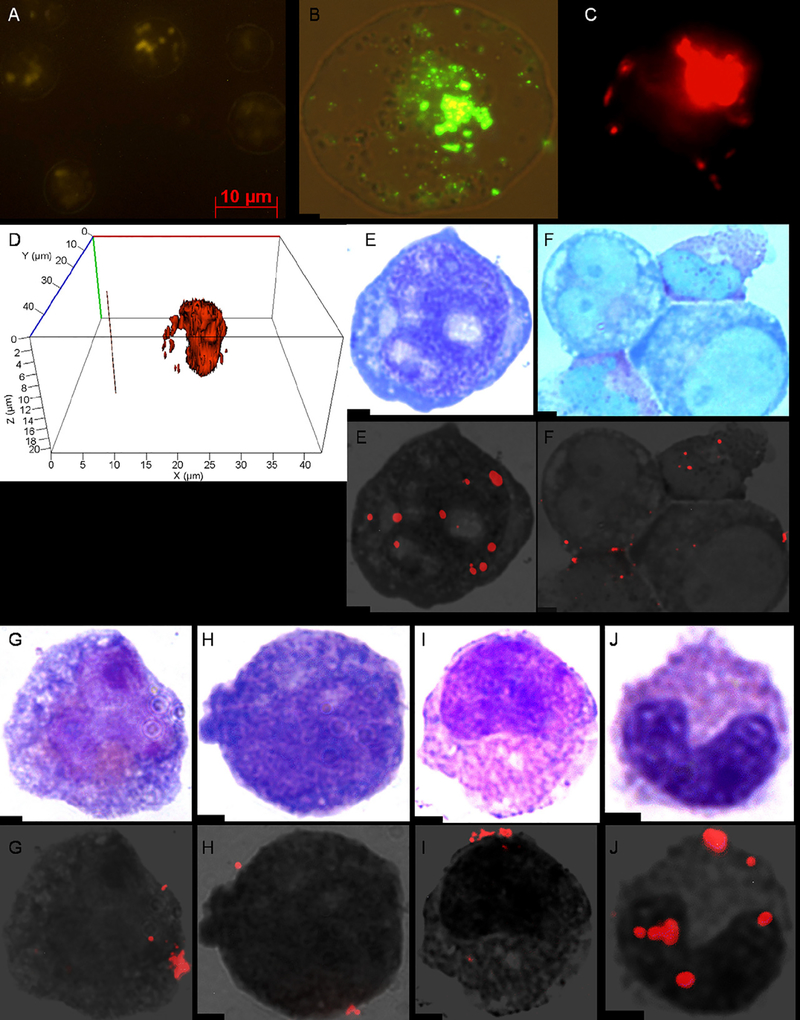

Labeling of hematologic cells with QDs was achieved in all cell lines and primary samples that we tested after a 10 h incubation with Q-trackers. 99% of KG-1 cells had visible QDs by fluorescence microscopy in live cells (Fig. 1A), fixed cells (Fig. 1B) and FACS analysis (data not shown). The location of QDs was largely intracellular (Fig. 1C and D). 97% of HL-60 cells had visible QDs by FACS (data not shown). 90% of cells in AML (Fig. 1E) and 55% of cells in CML patient samples (Fig. 1F) had visible QDs by fluorescence microscopy. In the CML sample, the more differentiated cells were labeled preferentially. 95% of normal human bone marrow cells had visible QDs by fluorescence microscopy, including cells of the myeloid lineage (Fig. 1G–J), erythroid lineage, lymphocytes and megakaryocytes (data not shown). Nearly 100% of normal mouse bone marrow cells demonstrated QDs by fluorescence microscopy (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

KG-1, normal human bone marrow and human leukemic cells after incubation with QDs. Fluorescent image of a live (A) and fixed (B) KG-1 cell after a 10 h incubation with Q-trackers 565. A Z-stack image from the cell center (C) and three dimensional reconstruction (D) of a live KG-1 cell after a 10 h incubation with Q-trackers 655 demonstrate the interior location of the QDs. AML (E) and CML (F) patient bone marrow samples after 10 h incubations with Q-trackers 655. Myeloblast (G), promyelocyte (H), metamyelocyte (I), and band (J) after a 10 h incubation of normal human bone marrow with Q-trackers 655 (G-J). Top row for images E-J: conventional microscopy of Wright-Giemsa stained cells; bottom row for images E-J: the corresponding merged fluorescence imaging microscopy and grayscale. All images at 100× magnification, except A (40×) and C (64×). Scale bar: 2 μm unless otherwise stated.

3.2. Labeling of hematologic cells and analysis via FACS through multiple generations

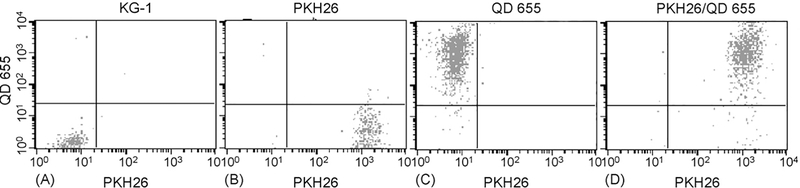

Two advantages of QDs are their high photon yield and narrow emission peak. Therefore, we hypothesized that flow cytometry would distinguish QDs from other dyes. So, we labeled KG-1 cells with PKH26 (567 nm emission), a cell membrane dye validated for tracking the number of cell divisions, and then incubated the cells with Q-trackers 655 (655 nm emission). FACS detected the QDs and discriminated them from PKH26 (Fig. 2). QDs did not increase fluorescence in the FACS channel that detects PKH26. However, PKH26 has an asymmetric emission spectrum which is biased towards longer wavelengths. As a result, PKH26 caused some increased fluorescence in the FACS channel that detects QDs. Still, over 99% of KG-1 cells were seen in the appropriate quadrant by FACS when unstained, stained with PKH26, QDs or both fluorophors (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

FACS discriminates between QD 655 and PKH26 in KG-1 cells. KG-1 cells were either stained with PKH26 and/or exposed to Q-trackers 655 and then subjected to flow cytometry. (A) KG-1 cells with no PKH26 or QDs; (B) PKH26 alone; (C) QD 655 alone; (D) PKH26 and QD655.

FACS analysis also showed that when CD34+ cells were labeled with only QDs (no PKH26), 98% had visible QDs after a 10 h incubation (Fig. 3). However, only 73% of cells had visible QDs when also stained with PKH26 (data not shown). This decreased detection sensitivity after PKH26 staining occurred because some fluorescence from PKH26 was seen in the FACS channel that detects QD 655, requiring an increased threshold for considering a cell QD positive. Of note, QD staining was brighter when CD34+ cells were separated from CD34− cells prior to staining with QDs (data not shown). This mirrored results in leukemic primary samples in which greater homogeneity led to more effective labeling whereas less homogeneity led to preferential labeling of more differentiated cells.

Fig. 3.

Labeling of cord blood CD34+ cells with Q-trackers 655. (A) CD34+ cells not stained with either PKH26 or Q-trackers 655. (B) CD34+ cells after a 10h incubation with Q-trackers 655.

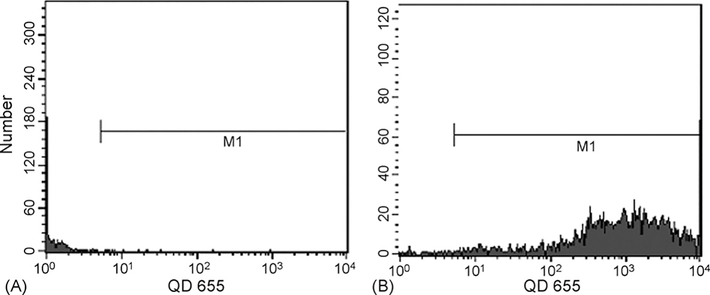

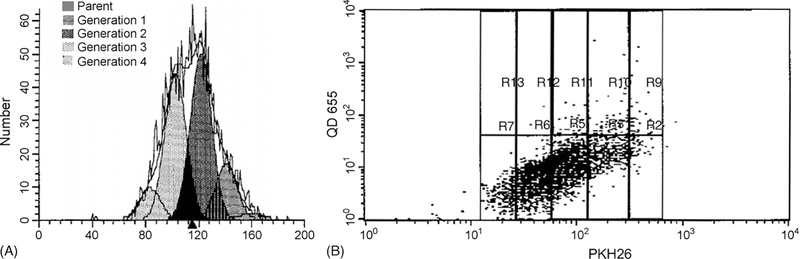

KG-1 cells were labeled with PKH26 and incubated for 10 h with Q-trackers 655. Cells were sorted to select the midpeak of PKH26, thereby isolating a population with uniform fluorescence. Two days after labeling with QDs, 97% of the cells contained QDs by FACS (Fig. 4A). By 6 days, 45% of the cells had QDs seen by FACS (Fig. 4C). The Modfit software determined the number of divisions that the cells had undergone during culture (Fig. 4D). Four days after the sort for the PKH midpoint, 3% of cells were undivided, 7% had undergone a single division, 24% had undergone two divisions, 61% had undergone three divisions and 5% had undergone four divisions. When cells from each generation were evaluated on the dot blot, it was apparent that QD fluorescence fell progressively with each cell division. QDs were detectable by FACS in over 95% of cells that had undergone less than three divisions, 66% of cells after three divisions and 20% of cells that had undergone four divisions (Fig. 4E). By fluorescence microscopy, in which the exposure was one minute as opposed to a fraction of a second for FACS, QDs could be seen longer (Fig. 4F and G). 5% of KG-1 cells demonstrated QDs by fluorescence microscopy after 2 weeks (data not shown), but this population could not be appreciated by FACS.

Fig. 4.

QDs are maintained in KG-1 cells through several days and four divisions. (A) QDs were detectable in 97% of KG-1 cells 2 days after staining, (B) 71% after 4 days, and (C) 45% after 6 days. (D) Four days after the incubation, most of the cells had undergone three divisions, denoted by the pink generation. (E) When extrapolating the data on generation number from the Modfit data to the dot blot, cells that had divided 0, 1 or 2 times (the three columns on the right) demonstrated QDs in over 95% of cells (dots above the horizontal line). Cells that had undergone three divisions demonstrated QDs in 66% and cells that had undergone four divisions demonstrated QDs in 20%. (F) Conventional microscopy at 100× magnification of a Wright-Giemsa stained KG-1 cell 8 days after incubation with Q-trackers 655. (G) The corresponding merged fluorescence imaging microscopy and grayscale. Scale bar: 2 μm.

Similar studies in CD34+ cells showed a much faster decrement in QD fluorescence (Fig. 5). Four days after the sort on the PKH midpoint, fluorescence was assessed. CD34+ cells (without QDs) 1 day after PKH26 staining served as a negative control. QDs were seen in only 38% of undivided cells, 10% of cells that had undergone a single division and 2% of cells that had undergone two divisions. Five days after the sort, 1% of CD34+ cells demonstrated QDs by fluorescence microscopy, and no QD positive cells were seen after that time.

Fig. 5.

Rare QD positive cells are seen 4 days after CD34+ cells were incubated with QDs. (A) Four days after incubation with Q-trackers 655, most CD34+ cells had undergone two or three divisions. (B) When extrapolating the data on generation number from the Modfit data to the dot blot, the cells that were part of the parent generation (far right) had QDs (denoted by a dot above the line) in 38%. 10% of cells that had undergone one division and 2% of cells that had undergone two divisions had visible QDs. Only rare QD positive cells were found among cells that had divided three or more times.

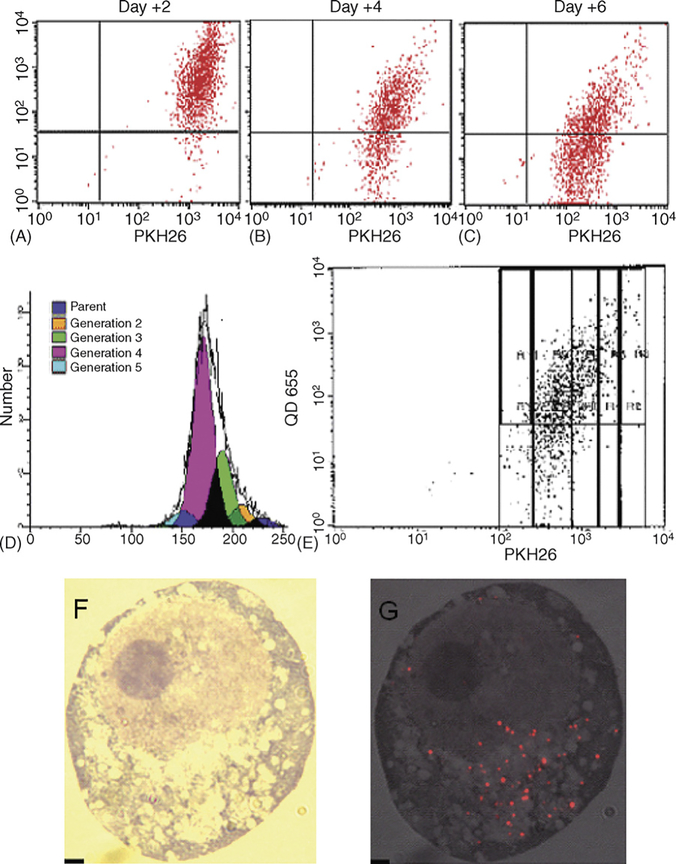

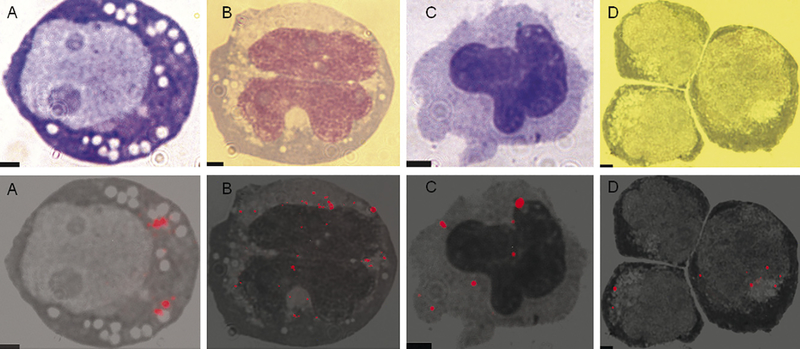

3.3. Differentiation of HL-60 and CD34+ cells

HL-60 is an acute myeloid leukemia cell line. These cells differentiate into neutrophil-like cells when cultured with either ATRA or DMSO [29]. When cultured with 1,25(OH)2 Vitamin D3, HL-60 cells differentiate into monocyte-like cells. HL-60 cells were labeled with Q-trackers 655 and cultured with either 1.25% DMSO or 1 × 10−7 M 1,25(OH)2 Vitamin D3. Four days later, 90% of the cells cultured with l,25(OH)2 Vitamin D3 had differentiated into monocyte-like cells, while 20% of the cells cultured with 1.25% DMSO had differentiated into neutrophil-like cells. 5% of the cells that differentiated into monocyte-like cells and 10% of cells that had differentiated into neutrophil-like cells contained QDs by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 6A–C).

Fig. 6.

QDs in differentiated progeny of HL-60 myeloblasts and CD34+ cells. (A) An HL-60 cell after a 10 h incubation with Q-trackers 655. (B) Resultant monocyte-like cell after 4 days of culture in 1 × 10−7 M 1,25(OH)2 Vitamin D3. (C) Resultant neutrophil-like cell after 4 days of culture in 1.25% (v/v) DMSO. (D) Monocytes derived from QD labeled CD34+ cells. Top row: conventional microscopy of Wright-Giemsa stained cells; bottom row: the corresponding merged fluorescence imaging microscopy and grayscale. All images at lOO× magnification. Scale bar: 2 μm.

After demonstrating retention of QDs during differentiation of HL-60 cells, we performed similar experiments in cord blood CD34+ cells. CD34+ cells were isolated from umbilical cord blood by incubating with FITC labeled anti-CD34 antibodies and sorting by FACS to select FITC positive cells. The CD34+ cells were incubated with Q-trackers 655 for 10h. After this incubation, 98% of the cells had visible QDs by FACS (Fig. 3). The cells were cultured with IL-3, SCF, G-CSF and GM-CSF to cause differentiation to neutrophils and monocytes. Neutrophilic differentiation was not robust, but QDs could be seen in rare (about 1%) monocytes 5 days after the completion of the incubation with Q-trackers 655 (Fig. 6D).

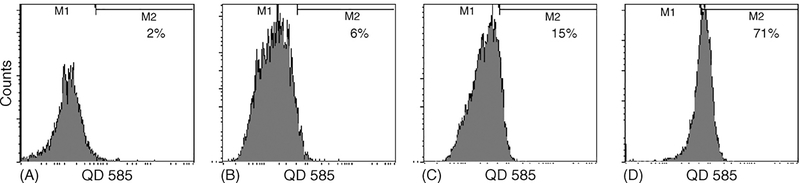

3.4. Specific labeling of cells with CD33

Ideal fluorophors target cells of interest. Thus, we evaluated the ability of Qdot 585 Streptavidin Conjugate (QD-SA) to target cells with specific cell surface antigens. First, QD-SAs were incubated with biotinylated anti-CD33 antibody at 4μC for 2h. QD-SAs without the primary antibody served as a negative control. The QD-SA/antibody combination was added to SUDHL-16 cells, a diffuse large B cell lymphoma cell line which does not express CD33, and HL-60 cells, which express CD33. 71% of HL-60 cells incubated with the biotinylated antibody and QD-SAs were positive by FACS. In contrast, only 15% of HL-60 cells incubated with QD-SA alone and 6% of the SUDHL-16 cells incubated with the biotinylated antibody and QD-SA were positive for QDs as measured by FACS (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Biotinylated QDs specifically targeted to cells expressing CD33. (A) 2% of SUDHL-16 lymphoblasts exposed to QD-SA alone demonstrated QDs. (B) 6% of SUDHL-16 lymphoblasts exposed to biotinylated anti-CD33/QD-SA demonstrated QDs. (C) 15% of HL-60 myeloblasts exposed to QD-SA alone had detectable fluorescence. (D) 71% of HL-60 cells had detectable fluorescence after exposure to biotinylated anti-CD33/QD-SA.

4. Discussion

Many of the current questions in hematology revolve around origin of cells of interest. Many techniques are available to address these questions, but they have drawbacks. Quantum dots have high quantum yield, narrow emission peaks, and they resist photobleaching, overcoming many of the pitfalls of other approaches.

Our results suggest that QDs are a potentially powerful, novel tool to help answer cell origin questions in hematology. With proper packaging, their small size allows QDs to be effectively endocytosed in a wide range of hematologic cells, both malignant and normal. Fluorescence can be seen in some of the resultant cells up to weeks. Fluorescence can also be maintained as cells differentiate, an essential property of a fluorescent tag. In addition to applications in hematology, this cell tracking capability could prove to be an important tool for studying cancer stem cells or embryonic stem cells.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to follow dividing human hematologic cells with QDs. Previous studies of QDs in hematology are limited to studies using QDs for immuno-histochemistry in red blood cells [30,31] and cell tracking in mouse lymphoma cell lines [32], This paucity of studies is likely related to the relatively recent development of semiconductor quantum dots as fluorescent nanoparticles for use in biology and medicine. Commercially available QDs, which have been available for an even shorter time, relieved major barriers for laboratories with a biological rather than chemical focus.

Limitations to the use of these nanoparticles exist. Some of the benefits of a narrow emission bandwith are hampered by the limitations of currently available conventional dyes. For instance, in our cell division analyses, a percentage of the fluorescence from the PKH26 was seen in the FACS channel that detects QD 655. This non-specific fluorescence from PKH26 forced an increase in the threshold of detection for QD 655, leading to lower sensitivity for QDs by FACS.

One barrier to studies in which cells are incubated with QDs is the potential for cytotoxicity [33]. In this study, we did not formally evaluate the cytotoxicity of the QDs. However, we grossly observed that proliferation of cells labeled with QDs did not appear different than cells without QDs. This, of course, does not definitively exclude subtle changes in growth. Although surrounded by a ZnS shell, the cadmium and selenium that make the core of the QDs are known to be toxic. The tolerability of these particles in vivo will require extensive evaluation prior to clinical use. QDs with less toxic materials are currently being developed and may prove to be even better agents for hematologic use.

With the extensive attention that these nanoparticles are receiving in the field of chemistry, newer generations of QDs will likely have even superior imaging properties. In addition, imaging technologies are improving at a rapid rate. Imaging systems specifically designed to detect multiple spectra on a single slide using a single light source [34] will likely revolutionize the field. Other improvements will likely include even more efficient intercellular uptake and retention strategies. These rapidly evolving technological improvements should make QDs even more effective tools.

QDs can probably be effectively targeted to any cell surface protein on any cell. As we show here, QDs attached to streptavidin can bind biotinylated anti-CD33 antibodies and specifically label myeloid leukemic cells and not lymphoid cells. In our assays, less than 100% of HL-60 cells were effectively labeled with QDs attached to an antibody against CD33. This likely indicates that we have not yet optimized the technique, and further fine-tuning is necessary.

Besides tracking cells, QDs could be used to image drugs as they interact with cells. For instance, rituximab is a monoclonal antibody directed against CD20 which is widely used in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Waldenstroms macroglobulinemia and autoimmune disorders. QD-labeled rituximab could home to lymph nodes, allowing the tumor to be imaged. Rituximab would likely maintain its clinical efficacy, allowing combined imaging and treatment. Although rituximab remains on the cell surface, other drugs enter cells. The intracellular activity of these drugs could be followed by QDs, allowing a better understanding of intracellular drug trafficking.

In summary, QDs are nanometer scale light emitting particles that are emerging as a new class of fluorescent probes for labeling and tracking biomolecular processes in living cells. This study is the first comprehensive analysis of QDs in hematologic cells and the first study of QDs in dividing human hematologic cells. With improvements in biologic techniques, as well as improvement in the chemistry and imaging of QDs, this technology should offer great opportunities as a research tool in the study of hematologic disorders and as a duel imaging and delivery system for various malignancies including lymphomas.

Acknowledgements

We thank Thanassis Papaioannou for his help with microscopy; Yinghua Sun, Jingjing Wang and Meng-Tse Chen for their assistance in cell imaging; Patricia Lim for her help with FACS sorting and analysis; and Yuhua Zhu for her help in handling the umbilical cord blood.

This research was funded in part by NIH grant number 5-T32-HL6699201-04, RO1 CA26038-22, RO1-HL 077912 (GMC) and PO1-HL073104 (GMC), Inger Fund, Parker Hughes Trust, and C. & H. Koeffler Foundation.

References

- [1].Wu X, Liu H, Liu J, Haley KN, Treadway JA, Larson JP, et al. Immunofluorescent labeling of cancer marker Her2 and other cellular targets with semiconductor quantum dots. Nat Biotechnol 2003;21(1):41–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tokumasu F, Dvorak J. Development and application of quantum dots for immunocytochemistry of human erythrocytes. J Microsc 2003;211(Pt 3):256–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wang HZ, Wang HY, Liang RQ, Ruan KC. Detection of tumor marker CA125 in ovarian carcinoma using quantum dots. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2004;36(10):681–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Goldman ER, Clapp AR, Anderson GP, Uyeda HT, Mauro JM, Medintz IL, et al. Multiplexed toxin analysis using four colors of quantum dot fluororeagents. Anal Chem 2004;76(3): 684–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Liang RQ, Li W, Li Y, Tan CY, Li JX, Jin YX, et al. An oligonucleotide microarray for microRNA expression analysis based on labeling RNA with quantum dot and nanogold probe. Nucl Acids Res 2005;33(2):el7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hoshino A, Fujioka K, Oku T, Nakamura S, Suga M, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Quantum dots targeted to the assigned organelle in living cells. Microbiol Immunol 2004;48(12):985–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pathak S, Choi SK, Arnheim N, Thompson ME. Hydroxylated quantum dots as luminescent probes for in situ hybridization. J Am Chem Soc 2001;123(17):4103–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dahan M, Levi S, Luccardini C, Rostaing P, Riveau B, Triller A. Diffusion dynamics of glycine receptors revealed by single-quantum dot tracking. Science 2003;302(5644):442–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wang L, Chen H, Wang L, Wang G, Li L, Xu F. Determination of proteins at nanogram levels by synchronous fluorescence scan technique with a novel composite nanoparticle as a fluorescence probe. Spectrochim Acta A: Mol Biomol Spectrosc 2004;60(11):2469–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kaul Z, Yaguchi T, Kaul SC, Hirano T, Wadhwa R, Taira K. Mortalin imaging in normal and cancer cells with quantum dot immuno-conjugates. Cell Res 2003;13(6):503–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Otsuka Y, Hanaki K, Zhao J, Ohtsuki R, Toyooka K, Yoshikura H, et al. Detection of Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guerin using quantum dot immuno-conjugates. Jpn J Infect Dis 2004;57(4):183–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lidke DS, Nagy P, Heintzmann R, Arndt-Jovin DJ, Post JN, Grecco HE, et al. Quantum dot ligands provide new insights into erbB/HER receptor-mediated signal transduction. Nat Biotechnol 2004;22(2): 198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mansson A, Sundberg M, Balaz M, Bunk R, Nicholls IA, Omling, et al. In vitro sliding of actin filaments labelled with single quantum dots. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004;314(2):529–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jaiswal JK, Mattoussi H, Mauro JM, Simon SM. Long-term multiple color imaging of live cells using quantum dot bioconjugates. Nat Biotechnol 2003;21(1):47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Voura EB, Jaiswal JK, Mattoussi H, Simon SM. Tracking metastatic tumor cell extravasation with quantum dot nanocrystals and fluorescence emission-scanning microscopy. Nat Med 2004; 10(9):993–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kim S, Lim YT, Soltesz EG, De Grand AM, Lee J, Nakayama A, et al. Near-infrared fluorescent type II quantum dots for sentinel lymph node mapping. Nat Biotechnol 2004;22(l):93–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Soltesz EG, Kim S, Laurence RG, DeGrand AM, Parungo CP, Dor DM, et al. Intraoperative sentinel lymph node mapping of the lung using near-infrared fluorescent quantum dots. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;79(l):269–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Parungo CP, Ohnishi S, Kim SW, Kim S, Laurence RG, Soltesz EG, et al. Intraoperative identification of esophageal sentinel lymph nodes with near-infrared fluorescence imaging. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005; 129(4):844–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Parungo CP, Colson YL, Kim SW, Kim S, Cohn LH, Bawendi MG, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping of the pleural space. Chest 2005; 127(5): 1799–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gao X, Cui Y, Levenson RM, Chung LW, Nie S. In vivo cancer targeting and imaging with semiconductor quantum dots. Nat Biotechnol 2004;22(8):969–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhelev Z, Jose R, Nagase T, Ohba H, Bakalova R, Ishikawa M, et al. Enhancement of the photoluminescence of CdSe quantum dots during long-term UV-irradiation: privilege or fault in life science research? J Photochem Photobiol B 2004;75(l-2):99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Umezawa N, Gelman MA, Haigis MC, Raines RT, Gellman SH. Translocation of a beta-peptide across cell membranes. J Am Chem Soc 2002; 124(3):368–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Morris MC, Depollier J, Mery J, Heitz F, Divita G. A peptide carrier for the delivery of biologically active proteins into mammalian cells. Nat Biotechnol 2001; 19(12): 1173–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pathak S, Choi SK, Arnheim N, Thompson ME. Hydroxylated quantum dots as luminescent probes for in situ hybridization. J Am Chem Soc 2001; 123(17):4103–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Koeffler HP, Golde DW. Acute myelogenous leukemia: a human cell line responsive to colony-stimulating activity. Science 1978;200(4346): 1153–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Koerner J, Nesic D, Romero JD, Brehm W, Mainil-Varlet P, Grogan SP. Equine peripheral blood-derived progenitors in comparison to bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 2006;24(6): 1613–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jabs A, Moncada GA, Nichols CE, Waller EK, Wilcox JN. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells acquire myofibroblast characteristics in granulation tissue. J Vasc Res 2005;42(2): 174–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Case SS, Price MA, Jordan CT, Yu XJ, Wang L, Bauer G, et al. Stable transduction of quiescent CD34(+)CD38(−) human hematopoietic cells by HIV-1-based lentiviral vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999;96(6):2988–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Miranda MB, Dyer KF, Grandis JR, Johnson DE. Differential activation of apoptosis regulatory pathways during monocytic vs. granulocytic differentiation: a requirement for Bcl-X(L)and XIAP in the prolonged survival of monocytic cells. Leukemia 2003; 17(2):390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tokumasu F, Dvorak J. Development and application of quantum dots for immunocytochemistry of human erythrocytes. J Microsc 2003;211(Pt 3):256–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tokumasu F, Fairhurst RM, Ostera GR, Brittain NJ, Hwang J, Wellems TE, et al. Band 3 modifications in Plasmodium falciparum-infected AA and CC erythrocytes assayed by autocorrelation analysis using quantum dots. J Cell Sci 2005;118(Pt 5): 1091–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hoshino A, Hanaki K, Suzuki K, Yamamoto K. Applications of T-lymphoma labeled with fluorescent quantum dots to cell tracing markers in mouse body. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004;314(1): 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Shiohara A, Hoshino A, Hanaki K, Suzuki K, Yamamoto K. On the cyto-toxicity caused by quantum dots. Microbiol Immunol 2004;48(9):669–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tsurui H, Nishimura H, Hattori S, Hirose S, Okumura K, Shirai T. Seven-color fluorescence imaging of tissue samples based on Fourier spectroscopy and singular value decomposition. J Histochem Cytochem 2000;48(5):653–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]