Abstract

Background and Aims:

Patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) assessing the tolerability of endoscopic procedures are scarce. In this study, we designed and validated a PREM to assess tolerability of endoscopy using conscious sedation.

Methods:

The patient-reported scale for tolerability of endoscopic procedures (PRO-STEP) consists of questions within 2 domains and is administered to outpatients at discharge from the endoscopy unit. Domain 1 (intraprocedural) consists of 2 questions regarding discomfort/pain and awareness, whereas domain 2 (postprocedural) consists of 4 questions on pain, nausea, distention, and either throat or anal pain. All questions are scored on a Likert scale from 0 to 10. Cronbach’s alpha was used to measure internal consistency of the questions. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to assess predictors of higher scores, reported using adjusted odds ratios and confidence intervals.

Results:

Two hundred fifty-five patients (91 colonoscopy, 73 gastroscopy, and 91 ERCP) were included. Colonoscopy was the least tolerable procedure by recall, with mean intraprocedural awareness and discomfort scores of 5.1 ± 3.8, and 2.6 ± 2.7, respectively. Consistency between intraprocedural awareness and discomfort/pain yielded an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha of .71 (95% confidence interval, .62-.78). Higher use of midazolam during colonoscopy was inversely associated with an intraprocedural awareness score of 7 or higher (per additional mg: adjusted odds ratio, .23; 95% confidence interval, .09-.54).

Conclusions:

PRO-STEP is a simple PREM that can be administered after multiple endoscopic procedures using conscious sedation. Future work should focus on its performance characteristics in adverse event prediction. (Gastrointest Endosc 2021;94:103–10.)

GI endoscopy is widely performed, with an estimated 18 million procedures carried out annually in the United States alone.1 Quality assurance in endoscopy is sought by all major GI societies and most institutions, as are methods to standardize or improve performance. The quality of a procedure or service can generally be measured by comparing a provider’s performance metrics with established benchmarks.2 Importantly, there is significant established provider-level variability in quality for several endoscopic procedures.3 Quality indicators exist for all commonly performed endoscopic procedures in an attempt to reduce this variability.4–7

Although the field of provider-related quality in endoscopy is well established, the experiences of patients undergoing endoscopic procedures have been relatively understudied. Patient experience is a key component to overall quality, having been linked to both safety and effectiveness,8 in addition to reimbursement in some healthcare models.9 Patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) and patient-reported outcome measures are instruments designed for patients to self-report their experiences and health status, respectively.10,11 The overall experience of a patient undergoing an endoscopic procedure depends on several factors requiring close consideration, including the booking process, pretest preparation, departmental checkin, communication of results, and follow-up, in addition to undergoing the actual procedure. PREMs designed to capture the overall patient experience during each of these steps are important and the subject of necessary research.12

PREMs specifically measuring both the intra- and postprocedural tolerability of endoscopic procedures are scarce, especially for procedures other than colonoscopy. Nurse- or provider-reported scales of patient comfort and tolerability have been validated for endoscopic procedures performed under conscious sedation,13–15 but none relies on the input of the patient. A patient satisfaction questionnaire relating to endoscopy has been designed but does not specifically assess intra- and postprocedural symptoms in detail.16 Measuring patient-reported intra- and postprocedural tolerability is important both for unit-level quality reporting and for research studies comparing patient characteristics, sedation types, or procedural parameters in endoscopy. Thus, in this study, we aimed to design and validate a PREM specifically assessing the tolerability of endoscopic procedures performed under conscious sedation and to examine predictors of inferior tolerability.

METHODS

Overview

The patient-reported scale for tolerability of endoscopic procedures (PRO-STEP) was designed to be delivered at the time of discharge after outpatient endoscopic procedures using endoscopist-administered conscious sedation. It was developed with the aim of measuring the intraprocedural and postprocedural physical tolerability of endoscopic procedures. It is not intended to measure patient attitudes, expectations, or emotions relating to endoscopy, although these domains are undoubtedly important, requiring separate dedicated efforts to study.

Development and implementation

The domains and questions in PRO-STEP were drafted by the authors based on a literature review of prior studies describing the symptoms experienced by patients undergoing endoscopic procedures under conscious sedation. After this, the tool was circulated for feedback by 4 endoscopists, 2 endoscopy nurses, and 2 patients having recently undergone endoscopy under conscious sedation, after which the current iteration was finalized.

PRO-STEP was administered prospectively at our institution in Calgary, Alberta, Canada between October 2019 and March 2020 on consecutive outpatients having signed informed consent for 2 other enrolling studies. Institutional ethics approval was granted for PRO-STEP administration as part of both these studies (REB18–0410 and REB19–1028). Any outpatient aged 18 or over undergoing EGD, colonoscopy, or ERCP was eligible for inclusion. Patients undergoing planned therapeutic EGD or colonoscopy procedures were not included in the cohort, although patients with inflammatory bowel disease undergoing colonoscopy with mapping biopsy sampling were included, as were patients undergoing incidental polypectomy during screening colonoscopy. Patients undergoing EGD and receiving biopsy sampling were also included. All procedures in the cohort were performed with endoscopist-administered conscious sedation with benzodiazepines, narcotics, and/or diphenhydramine by any of 14 endoscopists.

At our institution, outpatients are discharged after endoscopy if they have recovered for a minimum of 60 minutes and have an Aldrete score of 9/10 or higher.17 PRO-STEP was administered to outpatients immediately before discharge from the endoscopy unit after having undergone any of the above endoscopic procedures under conscious sedation. Each procedure type was analyzed separately, given potential differences between procedural parameters and/or responses.

Domains and questions

PRO-STEP consists of 2 broad domains relating to the overall physical tolerability of endoscopic procedures from the patient perspective: intraprocedural and postprocedural. Two questions comprise the intraprocedural domain (domain 1) and 4 questions the postprocedural domain (domain 2). Each question is measured using an 11-point Likert scale, with possible answers ranging from 0 to 10. Each question is prefaced with the verbal instruction “if 0 is none at all and 10 is the worst possible” to provide context to the patient or, in the case of intraprocedural awareness, with the instruction “if 0 is not aware at all and 10 is fully aware.” For purposes of comparison, scores of 0 to 2, 3 to 6, and 7 to 10 were arbitrarily considered mild (or none), moderate, and severe, respectively. The domains and questions comprising PRO-STEP are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Patient-reported scale for tolerability of endoscopic procedures domains and questions

| Intraprocedural domain (domain 1) |

| 1) What was your level of awareness during the procedure |

| (if 0 is not aware at all and 10 is fully aware) |

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

| 2) What was your level of discomfort or pain during the procedure? |

| (if 0 is none at all, and 10 is the worst possible) |

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

| Postprocedural domain (domain 2) |

| 1) What is your level of NEW abdominal pain after the procedure? |

| (if 0 is none at all, and 10 is the worst possible) |

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

| 2) What is your level of NEW nausea after the procedure? |

| (if 0 is none at all, and 10 is the worst possible) |

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

| 3) What is your level of NEW bloating or distention after the procedure? |

| (if 0 is none at all, and 10 is the worst possible) |

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

| 4a) What is your level of NEW mouth or throat pain after the procedure?* |

| (if 0 is none at all, and 10 is the worst possible) |

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

| 4b) What is your level of NEW bottom pain after the procedure?* |

| (if 0 is none at all, and 10 is the worst possible) |

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

Depending on whether the endoscopic procedure was performed via the mouth or anus, only 1 of questions 4a or 4b were asked.

Statistical analysis and outcomes

We determined a priori that domain 1 would be used for sample size determination given that a larger sample would be required to validate a questionnaire with 2 Likert questions rather than 4.18 Assuming a relative tolerable error of 10%, a coefficient of variation of 1.0, and a pairwise correlation coefficient of .3, a minimum sample size of 250 patients was determined.18 To validate the internal consistency of patient responses, Cronbach’s alpha test was used to determine correlations among intraprocedural awareness and intraprocedural discomfort/pain, postprocedural pain and postprocedural bloating/distention, and intraprocedural discomfort/pain and postprocedural pain. Medical records were reviewed at 30 days from index procedures to assess for adverse events (AEs), defined using the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Lexicon.19 Quantitative analyses correlating scores with the occurrence of AEs were not performed given a paucity of events.

Patient demographic variables were analyzed using the Student t test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to assess predictors of 2 a priori outcomes: a response of 3 or higher for each question or 7 or higher for each question. Potential confounders in the multivariable model included sex; age; current or former heavy use of alcohol (defined as >14 alcoholic drinks per week for men or >7 for women); any benzodiazepine use at baseline; any opiate use at baseline; doses of fentanyl, midazolam, and/or diphenhydramine used intraprocedurally; and procedure time (measured from the initial administration of sedation to extubation). Results are reported using adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All analyses were performed using R version 3.6.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Patients and procedural details

Two hundred fifty-five patients were included, with 91 having undergone colonoscopy, 73 EGD, and 91 ERCP. Baseline patient demographics are provided in Table 2. The proportion of male patients was similar across procedure types, ranging from 47.3% to 53.8% (P = .63). Mean age ranged between 53.6 and 56.3 years (P = .54). Mean doses of fentanyl, midazolam, and diphenhydramine were significantly different between procedure types, with the most used for ERCP (P < .001 for all 3 medications). The overall procedure time (from administration of sedation to extubation) was longest for colonoscopy, with a mean of 27.1 minutes.

TABLE 2.

Patient and procedural characteristics of the patient-reported scale for tolerability of endoscopic procedures cohort

| Colonoscopy (n = 91) | EGD (n = 73) | ERCP (n = 91) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male, % | 53.8 (49) | 47.9 (35) | 47.3 (43) | .63 |

|

| ||||

| Mean age, y | 54.4 (15.3) | 53.6 (13.2) | 56.3 (18.5) | .54 |

|

| ||||

| Current or former heavy ethyl alcohol use, % | 8.8 (8) | 13.7 (10) | 6.6 (6) | .08 |

|

| ||||

| Any baseline benzodiazepine use, % | 5.5 (5) | 4.1 (3) | 2.2 (2) | .52 |

|

| ||||

| Any baseline opiate use, % | 2.2 (2) | 5.5 (4) | 4.4 (4) | .54 |

|

| ||||

| Mean midazolam dose, mg | 3.89 (1.30) | 4.42 (1.22) | 5.33 (1.93) | <.001 |

|

| ||||

| Mean fentanyl dose, μg | 65.93 (21.58) | 73.97 (22.61) | 100.27 (39.53) | <.001 |

|

| ||||

| Mean diphenydramine dose, mg | 4.40 (14.24) | 5.48 (15.73) | 45.60 (13.23) | <.001 |

|

| ||||

| Mean overall procedure time, min | 27.13 (9.95) | 14.93 (6.21) | 17.46 (10.42) | <.001 |

|

| ||||

Values are % (n) or mean (standard deviation).

Distribution of responses

Endoscopic procedures with the patient under conscious sedation were generally well tolerated overall. Intraprocedural tolerability (assessed by domain 1) was highest for ERCP, where 87.9% and 91.2% of patients reported mild or lower levels of intraprocedural awareness or discomfort, respectively (mean scores ± standard deviation, 1.01 ± 2.45 and .63 ± 1.70, respectively). EGD was slightly less well-tolerated intraprocedurally, with 65.8% and 69.9% of patients reporting only mild or lower levels of intraprocedural awareness or discomfort, respectively (2.51 ± 3.36 and 1.99 ± 2.89, respectively). Colonoscopy was the least tolerable procedure, with 65.9% and 41.8% of patients reporting moderate or severe levels of intraprocedural awareness or discomfort, respectively (5.10 ± 3.83 and 2.63 ± 2.71, respectively).

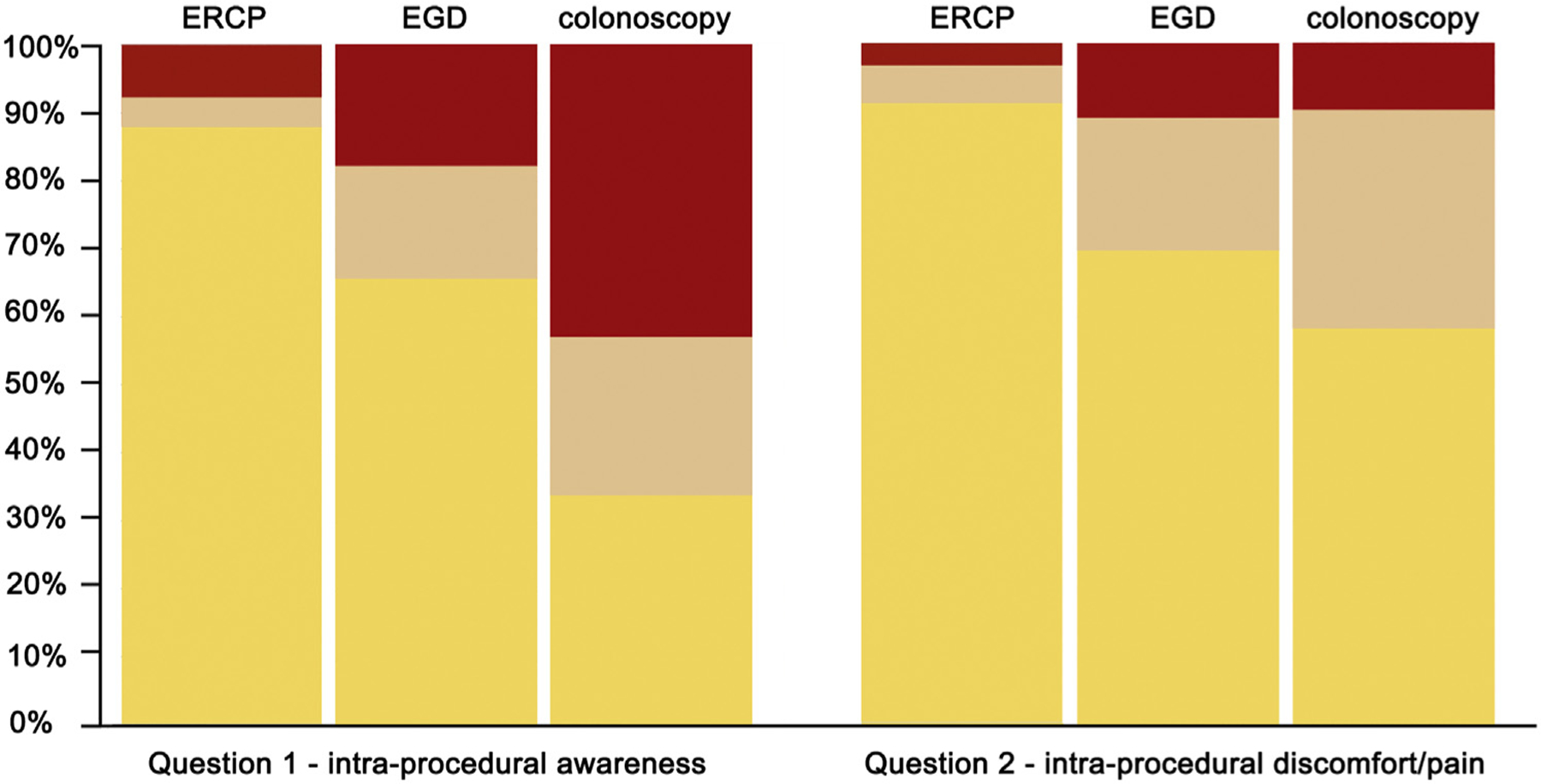

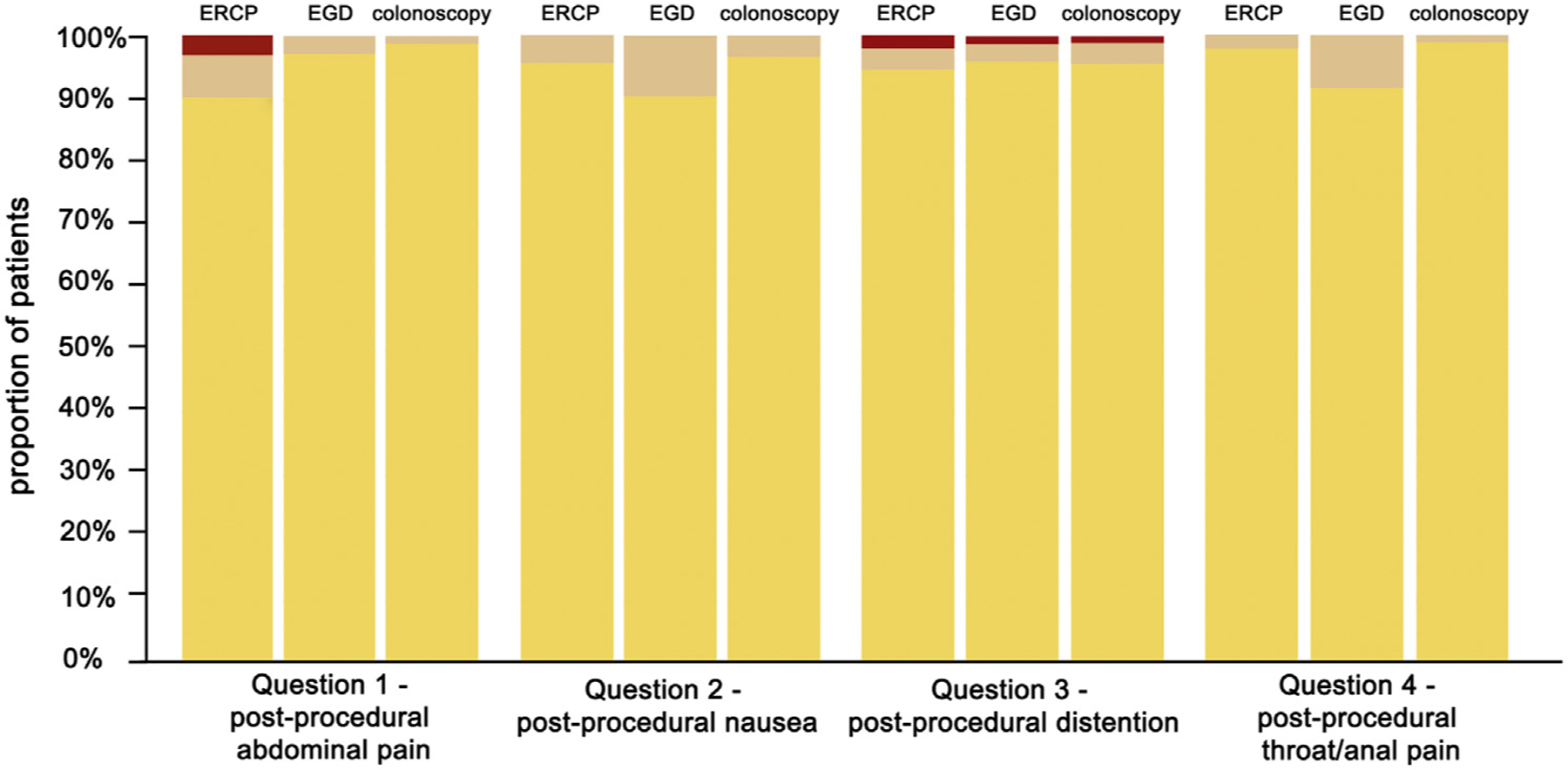

At the time of discharge, patients reported low levels of abdominal pain, nausea, bloating/distention, or throat/anal pain, regardless of the procedure performed, as evidenced by at least 90% of patients reporting only mild or lower symptoms across all questions in the postprocedural domain (domain 2). Three patients (3.3%) self-reported severe abdominal pain at the time of discharge after ERCP; no patients reported severe pain after EGD or colonoscopy. Mean PRO-STEP responses are provided in Table 3. Distributions of PRO-STEP responses by procedure are provided in Figures 1 and 2.

TABLE 3.

Mean patient-reported scale for tolerability of endoscopic procedures responses by procedure type (on Likert scale of 0–10)

| Question | Mean response ± standard deviation |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Colonoscopy (n = 91) | EGD (n = 73) | ERCP (n = 91) | |

| Intraprocedural awareness (domain 1) | 5.10 ± 3.83 | 2.51 ± 3.36 | 1.01 ± 2.45 |

|

| |||

| Intraprocedural discomfort/pain (domain 1) | 2.63 ± 2.71 | 1.99 ± 2.88 | .63 ± 1.70 |

|

| |||

| Postprocedural pain (domain 2) | .13 ± .54 | .21 ± .78 | .56 ± 1.65 |

|

| |||

| Postprocedural nausea (domain 2) | .16 ± .78 | .42 ± 1.12 | .15 ± .65 |

|

| |||

| Postprocedural bloating/distention (domain 2) | .40 ± 1.26 | .38 ± 1.30 | .44 ± 1.56 |

|

| |||

| Postprocedural anal/rectal pain (domain 2) | .09 ± .38 | N/A | N/A |

|

| |||

| Postprocedural throat/mouth pain (domain 2) | N/A | .61 ± 1.08 | .18 ± .75 |

|

| |||

N/A, Not applicable.

Figure 1.

Distribution of patient-reported scale for tolerability of endoscopic procedures responses for domain 1 (intraprocedural) questions. Yellow represents responses of 0, 1, or 2 (mild or none); tan represents responses of 3, 4, 5, or 6 (moderate); and red represents responses of 7, 8, 9, or 10 (severe).

Figure 2.

Distribution of patient-reported scale for tolerability of endoscopic procedures responses for domain 2 (postprocedural) questions. Yellow represents responses of 0, 1, or 2 (mild or none); tan represents responses of 3, 4, 5, or 6 (moderate); and red represents responses of 7, 8, 9, or 10 (severe).

Internal consistency of responses

Intradomain consistency between intraprocedural awareness and intraprocedural discomfort or pain yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of .71 (95% CI, .62-.79), indicating an acceptable level of internal consistency between these questions in domain 1. There was poor intradomain consistency between questions in domain 2, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .29 (95% CI, .04-.55) between postprocedural pain and postprocedural bloating. The interdomain consistency between intraprocedural pain and postprocedural pain was also poor, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .18 (95% CI, .01-.34).

Predictors of PRO-STEP responses

Increasing use of midazolam (per 1 mg) during colonoscopy was associated with lower intraprocedural awareness, with an AOR of .23 (95% CI, .09-.54) for an intraprocedural awareness score of 7 or higher and of .43 (95% CI, 0.25-.75) for a score of 3 or higher. Higher use of fentanyl (by 25 μg) was associated with an awareness score of 7 or higher (AOR, 3.03; 95% CI, 1.11–8.34). There were no other significant associations between any variable and responses of 7 or higher (or 3 or higher) to any intra- or postprocedural question. Associations for scores of 7 or higher for intraprocedural awareness are provided in Table 4, whereas associations for all other questions and procedures are provided in Supplementary Tables 1 to 4 (available online at www.giejournal.org).

TABLE 4.

Predictors of a score ≥7 on the patient-reported scale for tolerability of endoscopic procedures intraprocedural awareness question (domain 1) by multivariable regression

| Variable | Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Colonoscopy (n = 91) | EGD (n = 73) | ERCP (n = 91) | |

| Male sex | .87 (.31–2.49) | .98 (.21–4.61) | 1.39 (.24–7.93) |

|

| |||

| Age (per increasing year) | .99 (.94–1.03) | .95 (.89–1.01) | .99 (.94–1.05) |

|

| |||

| Current or former heavy ethyl alcohol use | .58 (.09–4.04) | 5.97 (.80–44.70) | N/S |

|

| |||

| Any baseline benzodiazepine use | 1.24 (.12–12.18) | N/S | N/S |

|

| |||

| Any baseline opiate use | N/S | N/S | N/S |

|

| |||

| Midazolam dose (per additional 1 mg) | .23 (.09-.54) | .86 (.41–1.80) | 1.81 (.63–5.23) |

|

| |||

| Fentanyl dose (per additional 25 μg) | 3.03 (1.11–8.34) | .56 (.19–1.64) | .98 (.27–3.54) |

|

| |||

| Diphenydramine dose (per additional 25 mg) | 1.37 (.48–3.72) | 2.07 (.65–6.56) | .28 (.05–1.60) |

|

| |||

| Overall procedure time (per increasing minute) | 1.05 (.90–1.11) | .98 (.86–1.12) | .99 (.92–1.08) |

|

| |||

N/S, Non-significant with unreliable point estimate and wide confidence intervals.

Adverse events

There were no AEs or related admissions after any of the performed EGDs or colonoscopies. Of 91 ERCPs in the cohort, 5 patients experienced pancreatitis (5.5%), 1 patient experienced postsphincterotomy bleeding (1.1%), and 1 experienced cholangitis (1.1%). Of the 5 patients who experienced pancreatitis, self-reported scores for postprocedural abdominal pain at the time of discharge were 0, 0, 3, 5, and 6, respectively, of 10. The 2 patients who experienced bleeding and cholangitis had postprocedural pain scores of 3 and 0, respectively. Among 9 patients reporting moderate or severe abdominal pain at discharge after ERCP (score of 3–10), 5 experienced an AE as described above. No patients self-reporting a moderate or severe level of bloating or distention at discharge after any procedure were readmitted for any reasons including AEs. No patients reporting moderate levels of nausea or throat/anal pain experienced any readmissions or AEs (none reported severe levels).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we described the design, implementation, and validation of PRO-STEP, an easy-to-use tool designed to measure the patient-reported tolerability of endoscopic procedures performed using conscious sedation. In addition, we assessed predictors of higher scores. Administering this tool to outpatients at the time of discharge provides a benchmark for both intraprocedural and postprocedural tolerability of commonly performed endoscopic procedures, including colonoscopy, EGD, and ERCP. Going forward, PRO-STEP can be used equally efficiently for quality assurance and/or research purposes.

Several prior studies have examined the patient experience as it relates to GI endoscopy.20 The focus of these has ranged from describing the holistic endoscopy experience12 to addressing aspects of pre- or postprocedural satisfaction.21–23 Few studies have specifically aimed to assess the physical tolerability of procedures.21,24,25 Furthermore, although intraprocedural abdominal pain has been studied,26 little consideration has been given to measuring other physical symptoms that are common after endoscopy, such as nausea, distention, or throat/anal pain. Equally importantly, most studies in this area have focused on experiences during colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy, leaving a large knowledge gap pertaining to benchmarking of experiences during ERCP and EGD. Finally, specific nurse- and/or provider-reported scales of patient comfort and tolerability have been validated,13–15 but none relies solely on the input of the patient and therefore cannot be considered PREMs.

The importance of PREMs is only recently beginning to be broadly recognized. Within endoscopy, there are multiple reasons to measure and compare patient-reported measures of experience. First, there is an established correlation between positive patient experiences and favorable clinical outcomes.27 Second, a patient’s experience has the ability to (positively or negatively) influence future follow-up, compliance, screening uptake, and/or willingness to undergo repeat endoscopy, particularly in a previously endoscopy-naive patient.10 Third, influences from the fields of quality assurance and quality improvement are now widespread in endoscopy, as evidenced by the rising prevalence of endoscopy unit rating scales and continuous audit and feedback efforts.28,29 Furthermore, patient satisfaction is now commonly tied to reimbursement in several healthcare models.9,30 PREMs are therefore crucial to add the important patient perspective to these initiatives and identify potential areas for improvement. Finally, validated PREMs can be applied in future endoscopy studies.

Our results demonstrate good levels of tolerability for all endoscopic procedures studied. Colonoscopy was the least tolerable procedure in our cohort but was still well tolerated overall, with a mean intraprocedural pain/discomfort score of 2.63 of 10 and a standard deviation of 2.71. These patient-reported scores are consistent with provider-reported pain/discomfort scores reported in other studies. For instance, the mean nurse-assessed patient comfort score was 3.2 of a possible 9 points for outpatients undergoing colonoscopy in a study of 300 patients.15 Similarly, in a cohort of 317 patients, a novel scale yielded mean pain/ discomfort scores ranging from 2.1 to 2.5 of 9 when administered by health providers 30 minutes after the completion of colonoscopy.13 Thus, our novel PREM yields results consistent with previously published provider-reported parameters for colonoscopy, suggesting good generalizability and external validity of the tool.

Few existing tools have assessed the physical tolerability of ERCP or EGD procedures. Sedation practices related to the performance of ERCP are variable and region-specific. For instance, ERCP performed using endoscopist-administered conscious sedation is almost nonexistent in the United States,31 whereas it is commonplace in Canada and much of the United Kingdom.32 For regions performing ERCP using conscious sedation, a validated measure of procedural tolerability is key for future benchmarking and research endeavors. Perhaps surprisingly, ERCP procedures were the most well-tolerated procedures in our cohort from an intraprocedural perspective according to domain 1 PRO-STEP responses. Of note, the administered doses of fentanyl and midazolam were both significantly higher for these procedures, likely impacting intraprocedural recall. Importantly, the preferential use of diphenhydramine for ERCP procedures could also account for the high tolerability of these procedures. Diphenhydramine is a useful and safe adjunct to benzodiazepine- and narcotic-based conscious sedation whose use during colonoscopy has been demonstrated to be efficacious in decreasing patient pain and awareness in a randomized trial.33 Also contributing to the high tolerability of ERCP procedures is that although the endoscope is advancing or moving more often than not during colonoscopy or EGD, the scope is static for most of the procedure during ERCP. Although ERCP may subject patients to more painful interventions,34 this phenomenon may be partially counteracted by the static nature of the scope, which, in addition to the above drug-related factors, could explain our findings.

A primary shortcoming of PRO-STEP is its lack of depth and scope as a holistic endoscopy PREM. For instance, PRO-STEP does not measure any aspects of a patient’s pre-endoscopy experience. Although we believe PRO-STEP captures an accurate range of physical symptoms associated with endoscopy, it does not measure the emotional or psychological impacts of procedures or aspects of patient communication, preferences, or overall degrees of satisfaction—all crucial to improve overall patient care.12 Therefore, PRO-STEP responses should not be used as a surrogate for overall patient satisfaction or willingness to undergo future procedures. Similarly, we did not distinguish between intraprocedural discomfort and pain. Although for many patients these terms are synonymous, one must also acknowledge that “discomfort” could encompass several other factors including embarrassment, modesty, anxiety, and/or gender issues.12 Additionally, the tool does not take into account the day(s) after endoscopic procedures, where persistent mild symptoms or residual sedation effects can be an issue.35 It would be instructive to learn whether such patients would accept higher degrees of intraprocedural discomfort or awareness if they could be assured of an absence of a lingering sedation effect in the day(s) after their procedure. Related to this, it is also important to acknowledge that some patients may prefer higher (rather than lower) levels of intraprocedural awareness, which is a limitation of PRO-STEP. Furthermore, higher awareness levels could potentially be beneficial in colonoscopy, where dynamic position changes improve quality.36 Endoscopists should always strive to administer the lowest possible levels of sedation that permit safe and tolerable performance of a procedure.

Limitations of our study methodology also require acknowledgment. Although individual feedback was obtained from patients, endoscopy nurses, and physicians during the tool’s design, we did not perform a formal thematic analysis or conduct structured focus groups. Given the limited intended scope of our tool, we believed these steps were unnecessary; however, it is possible that important themes or values may have been missed as a result. We did not internally correlate PRO-STEP scores with physician- or nurse-estimated measures of discomfort or pain; however, as discussed, our patient-reported pain scores for colonoscopy are consistent with those previously reported using nurse- and/or endoscopist-based estimates. Importantly, we did not have an adequate number of AEs for any procedure (a byproduct of our overall sample size) to quantify potential associations between PRO-STEP scores at discharge and either AEs or unplanned healthcare encounters. This is an important area for future study that could have implications on patient-specific monitoring protocols, investigations, and/or or admissions. Importantly, the tool was not administered to inpatients or non-English speakers, potentially limiting its generalizability. Furthermore, our study design was susceptible to protopathic bias, whereby an intervention is delivered in response to a measured outcome rather than preceding it; specifically, this phenomenon could explain the unexpected relationship between increasing fentanyl doses and higher intraprocedural awareness in some procedures. Finally, this was a study performed at a single institution, which also limits its generalizability.

In conclusion, PRO-STEP is an easy-to-use PREM for outpatient endoscopic procedures using conscious sedation. This tool can be used to measure and standardize patients’ physical symptoms during and after most endoscopic procedures for quality assurance and/or research purposes. Future work should focus on the performance characteristics of PRO-STEP in predicting AEs and/or unplanned healthcare encounters. Future studies should also compare patient-reported assessments of endoscopic tolerability with evaluations of overall patient satisfaction to determine whether these are correlated.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations:

- AE

adverse event

- AOR

adjusted odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- PREM

patient-reported experience measure

- PRO-STEP

patient-reported scale for tolerability of endoscopic procedures

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: Dr Forbes is a consultant for Boston Scientific, Pentax Medical, and Pendopharm and has received research funding from Pentax Medical. Dr Elmunzer is a consultant for Takeda Pharmaceuticals. All other authors disclosed no financial relationships. Research support for this study (Forbes, Heitman) was provided by the NB Hershfield Chair in Therapeutic Endoscopy, University of Calgary.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, et al. Burden and cost of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the United States: update 2018. Gastroenterology 2019;156:254–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chassin MR, Galvin RW. The urgent need to improve health care quality. Institute of Medicine National Roundtable on Health Care Quality. JAMA 1998;280:1000–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keswani RN, Qumseya BJ, O’Dwyer LC, et al. Association between endoscopist and center endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography volume with procedure success and adverse outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:1866–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adler DG, Lieb JG 2nd, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:54–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:72–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wani S, Wallace MB, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for EUS. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:102–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park WG, Shaheen NJ, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for EGD. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:60–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open 2013;3:e001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston KJ, Wiemken TL, Hockenberry JM, et al. Association of clinician health system affiliation with outpatient performance ratings in the medicare merit-based incentive payment system. JAMA 2020;324:984–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black N, Jenkinson C. Measuring patients’ experiences and outcomes. BMJ 2009;339:b2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kingsley C, Patel S. Patient-reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures. BJA Educ 2017;17:137–44. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neilson LJ, Patterson J, von Wagner C, et al. Patient experience of gastrointestinal endoscopy: informing the development of the Newcastle ENDOPREM™. Frontline Gastroenterol 2020;11:209–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Telford J, Tavakoli I, Takach O, et al. Validation of the St. Paul’s Endoscopy Comfort Scale (SPECS) for colonoscopy. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol 2020;3:91–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munson GW, Van Norstrand MD, O’Donnell JJ, et al. Intraprocedural evaluation of comfort for sedated outpatient upper endoscopy and colonoscopy: the La Crosse (WI) intra-endoscopy sedation comfort score. Gastroenterol Nurs 2011;34:296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rostom A, Ross ED, Dube C, et al. Development and validation of a nurse-assessed patient comfort score for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2013;77:255–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko HH, Zhang H, Telford JJ, et al. Factors influencing patient satisfaction when undergoing endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69:883–91; quiz 891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aldrete JA, Kroulik D. A postanesthetic recovery score. Anesth Analg 1970;49:924–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park J, Jung M. A note on determination of sample size for a Likert scale. Commun Korean Stat Soc 2009;16:669–73. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken L, et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;71:446–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown S, Bevan R, Rubin G, et al. Patient-derived measures of GI endoscopy: a meta-narrative review of the literature. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:1130–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bytzer P, Lindeberg B. Impact of an information video before colonoscopy on patient satisfaction and anxiety—a randomized trial. Endoscopy 2007;39:710–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin OS, Schembre DB, Ayub K, et al. Patient satisfaction scores for endoscopic procedures: impact of a survey-collection method. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:775–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin EH, Hong KS, Lee Y, et al. How to improve patient satisfaction during midazolam sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy? World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:1098–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heuss LT, Sughanda SP, Degen LP. Endoscopy teams’ judgment of discomfort among patients undergoing colonoscopy: “How bad was it really?”. Swiss Med Wkly 2012;142:w13726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chlan L, Evans D, Greenleaf M, et al. Effects of a single music therapy intervention on anxiety, discomfort, satisfaction, and compliance with screening guidelines in outpatients undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy. Gastroenterol Nurs 2000;23:148–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geir H, Michael B, Gert H-H, et al. The Norwegian Gastronet project: continuous quality improvement of colonoscopy in 14 Norwegian centres. Scand J Gastroenterol 2006;41:481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anhang Price R, Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med Care Res Rev 2014;71:522–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacIntosh D, Dube C, Hollingworth R, et al. The endoscopy Global Rating Scale-Canada: development and implementation of a quality improvement tool. Can J Gastroenterol 2013;27:74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bishay K, Causada-Calo N, Scaffidi MA, et al. Associations between endoscopist feedback and improvements in colonoscopy quality indicators: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2020;92:1030–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zamora D Using patient satisfaction as a basis for reimbursement: political, financial, and philosophical implications. Creat Nurs 2012;18: 118–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buxbaum J, Roth N, Motamedi N, et al. Anesthetist-directed sedation favors success of advanced endoscopic procedures. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:290–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forbes N, Koury HF, Bass S, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of ERCP at a Canadian tertiary centre: initial results from a prospective high-fidelity biliary endoscopy registry. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol Epub 2020. Mar 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Nusrat S, Madhoun MF, Tierney WM. Use of diphenhydramine as an adjunctive sedative for colonoscopy in patients on chronic opioid therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;88: 695–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg E, Kuipers E, et al. The burden of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) performed with the patient under conscious sedation. Surg Endosc 2012;26:2213–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dong MH, Kalmaz D, Savides TJ. Missed work related to mid-week screening colonoscopy. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:2114–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li P, Ma B, Gong S, et al. Effect of dynamic position changes during colonoscope withdrawal: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc 2021;35:1171–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.