Abstract

Digital technology use plays an essential role in adolescents’ psychological adjustment, impacting their mental health and well-being. In this scenario, Problematic Internet Use (PIU) is a risky condition for developing behavioral addiction in adolescence. Most of the research on PIU in adolescence focus on dimensions that may amplify or buffer it, finding significant associations between PIU and interpersonal problems with peers, maladaptive personality traits, low self-esteem, emotion dysregulation, and increasing psychological difficulties. It has been suggested that PIU might represent a maladaptive coping strategy to tackle problematic psychosocial functioning. In this line, the current cross-sectional study focused on PIU’s role in the association between personality dimensions and internalizing/externalizing problems. Two-hundred thirty-one middle and late adolescents (age range 15–19 years; 62% Female) attending public junior high schools in Italy completed the Internet Addiction Test (IAT), the Adolescent Personality Structure Questionnaire (APS-Q), and the Youth Self Report (YSR). Moderation analyses were used to test the hypothesis that higher PIU amplifies the relationship between maladaptive personality dimensions and psychological symptoms. Results indicated that only high PIU influenced the relationship between difficulties in building significant relationships with peers and internalizing problems. Conversely, PIU buffered the relationship between difficulties in adolescents’ sense of self (identity) and internalizing problems and the association between aggression regulation and internalizing problems, supporting the role of PIU as a maladaptive coping strategy. These findings encourage accurately evaluating PIU as a risk factor in adolescence: (1) considering how high PIU’s presence should impact the relationship between adolescent personality and the quality of their relationships with peers; (2) acknowledging the role of PIU as a regulation strategy for identity difficulties and aggression dysregulation.

Keywords: Personality development, Problematic internet use, Psychopathological symptoms, Adolescence, Internalizing problems, Externalizing problems

Introduction

Adolescence represents an evolutionary “middle ground” where, perhaps more than in any other phase of the life cycle, sometimes abrupt changes occur that involve body and psychological well-being. Indeed, during these tumultuous years, adolescents face the significant challenge of developing their personality structure in its future adult form, tackling some fundamental tasks that include the establishment of a coherent, stable, and original identity, the ability to regulate overwhelming emotions, and the maturation of interpersonal relationships, both romantic and with significant friends (Kroger, 2007). The development of a healthy personality structure is an essential building block for adolescents’ quality of psychosocial functioning, resulting from their ability to navigate typical adolescent’s crises and developmental challenges successfully (Sharp & Wall, 2018; Benzi et al., 2018).

However, personality pathology can occur when adolescents fail their developmental tasks fostering a more rigid functioning that significantly affects their quality of life and experiences. In this regard, literature highlighted the strong association between developing personality pathology in adolescence and the presence of internalizing and externalizing problems (Stepp et al., 2016). Internalizing problems include pathological features such as anxiety, dissociation, and depression, while externalizing problems comprise pathological features such as conduct disorder, substance use disorder, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Research has demonstrated that internalizing and externalizing problems represent significant predictors of maladaptive personality and are associated with personality functioning through adolescence (Chanen et al., 2007; Ammaniti et al., 2015).

A substantial contribution in understanding developmental processes of adolescence comes from developmental neuroscience that highlights how the adolescent brain is wired for social exploration and experimentation with new contexts and situations (Casey et al., 2008; Benzi et al., 2020). In this sense, adolescents’ experience in everyday life guarantees the possibility of structuring their personality both related to the quality of the relationship with the self and with significant others (Kernberg et al., 2000).

However, nowadays, an integral part of the daily experience of adolescents encompasses the use of digital technologies (Giovanelli et al., 2020). Even more so, during this crucial developmental stage, the use of digital technologies represents another way for adolescents to play out dimensions of their developing personality, both related to the self (identity) and to interpersonal relationship (Benzi et al., 2021).

In this sense, the role of digital technologies in adolescents’ psychological adjustment and well-being is twofold. On the one hand, the very potential that digital technologies offer contributes to forming an engaging and stimulating experience that leverages adolescents’ motivation to explore. In this line, the Internet is an easily accessible comprehensive repository, and social media act as relational playgrounds where adolescents can engage with peers beyond their everyday experience to forge relationships and expand their boundaries (Guinta & John, 2018). Also, research shows that adolescents do not view technology use in a mutually exclusive way but rather as something to integrate within their cognitive and affective experience (Reich et al., 2012).

On the other hand, technology can foster negative impacts on the adolescents’ mental health and well-being. Interestingly, as digital technologies enormously developed from the beginning of the twenty-first century, research has found different variables to help understanding this phenomenon in adolescence (Spada, 2014). Indeed, a first important focus was just the observation of the amount of time spent using digital technologies: Gross et al. (2002) pointed out that the time spent on the Internet was not associated with the well-being of young people, but rather the perception of the intimacy of instant messaging was linked to greater social anxiety and loneliness of daily experience.

Over the years, as the available technologies have diversified, research has focused on their possible adverse effects, mostly following the idea that internet use does not allow adolescents to experiment with social reality and therefore deprives them of the possibility of developing a healthy social functioning (Milani et al., 2009). Therefore, if on the one hand it has been shown that new technologies can act as social facilitators and stimulate the creativity of adolescents, on the other hand, as in situations of pre-existing fragility, they can act as a trigger for the exacerbation of internalizing and externalizing problems (Selfhout et al., 2009).

Problematic Internet Use in Adolescence

In this context, a useful construct is that of Problematic Internet Use (PIU), which refers to the subject’s inability to control their Internet use, leading to negative consequences in their daily life. There are no agreed-upon criteria to define PIU, but researchers highlight its similarities to addictive behaviors and impulse control disorders (Spada, 2014).

Indeed, Block (2008) suggested considering four diagnostic criteria for PIU that stressed its addictive features: (1) excessive use of the medium at the expense of other essential activities of daily life; (2) presence of externalizing and internalizing problems when it is not possible to access them (abstinence); (3) need for continuous hardware and software upgrades and in general an increasing use of technologies, as to obtain the desired effect (tolerance); (4) presence of negative consequences related to PIU (generalized fatigue, lowered school performance, social isolation). However, as the Internet gaming disorder was introduced in Section III of the DMS-5 (APA, 2013), PIU is not considered a psychiatric disorder yet (Griffiths et al., 2016).

Overall, prevalence of PIU amongst adolescents has been thoroughly investigated finding rates range up to 14% for males and 10% for females (e.g., Siomos et al., 2008; Vigna-Taglianti et al., 2017). Another recent study found prevalence of PIU of 20%, further highlighting the importance of considering the implications of this phenomenon in adolescence (Laconi et al., 2017).

Most of the research on PIU in adolescence focus on dimensions that may amplify or buffer it. One area concerns the relationship between the quality of interpersonal relationships and PIU. A study by Milani et al. (2009) showed that lower quality of peer relationships can result in PIU. Another interesting contribution underlines how “loneliness is the cause and the effect of PIU” (Kim et al., 2009), showing that any kind of Internet use can lead to an uncontrolled use with maladaptive outcomes (both considering its use for social networking and instant messaging as well as for entertainment purposes, like downloading files). Moreover, over the years, along with questions related to the identification of a set of diagnostic criteria, research has questioned the need for a framework in which to include PIU. In this context, the role played by self-esteem and internalizing aspects such as anxiety and depression has been emphasized: higher self-confidence corresponds to a lower probability of PIU, just as higher internalizing problems are significantly associated to PIU (Kim & Davis, 2009). Overall, research showed significant association between PIU and several psychopathological features such as anxiety (Caplan, 2006), depression (Gámez-Guadix, 2014), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Anderson et al., 2017), emerging personality disorders (Fontana et al., 2018), and substance use disorders (Rücker et al., 2015).

Besides, significant associations have been found between maladaptive personality functioning and PIU. In a recent study, Laconi et al. (2017) showed that PIU was predicted by personality traits related to cluster B features (such as emotional dysregulation and impulsivity) and cluster C features (such as dimensions of anxiety, control, and dependency).

All in all, research stressed PIU more as an outcome related to pre-existent fragilities or as a trigger for other psychological problems such as internalizing and externalizing features.

Interestingly, it has been suggested that PIU might represent a maladaptive coping strategy to tackle problematic psychosocial functioning (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014). Although, to our knowledge, no study explored its potential effect on the relationship between personality functioning and psychological symptoms. In this line, the current research focused on PIU’s role in the association between personality dimensions and internalizing/externalizing problems.

The Current Study: Aims and Hypotheses

This study aims to evaluate the role of PIU in the association between maladaptive personality functioning and externalizing/internalizing problems in adolescence. Therefore, we hypothesize that maladaptive personality functioning would be associated with increasing externalizing/internalizing problems. However, we expect the strength of the association between personality dimensions and psychopathological symptoms (respectively, internalizing and externalizing problems) to vary as a function of the level of PIU. Indeed, we hypothesize that higher PIU influences the strength and the direction of the relationship between personality functioning and psychopathological symptoms. Thus, we expect that the relationship between maladaptive personality functioning and externalizing/internalizing problems will be positive and stronger when PIU is higher.

In other words, we hypothesize that PIU moderates the relationship between personality and externalizing/internalizing problems. As noted by Wu and Zumbo (2008), moderation and mediation imply two different models for understanding a relationship between two variables. Mediation explains the process of why and how a cause-and-effect happens, while moderation postulates when or for whom the independent variable (i.e., maladaptive personality functioning) causes the dependent variables (i.e., externalizing/internalizing symptoms). Within the limits of our cross-sectional design, we consider higher PIU as a risk factor that amplifies the relationship between personality and externalizing/internalizing problems rather than consider PIU as an intermediate effect between personality and psychopathology (as done in a mediation model, see Wu & Zumbo, 2008).

Method

Participants

Participants were 231 adolescents (142 females; age range 15–19 years old; M age = 17.1, SD = 1.10) attending four public junior high schools in the metropolitan area of Rome, Italy. Participants were mainly Italian natives (96.5% of the total sample), with a residual percentage of students born in other areas (2.2% in Eastern Europe, 1.3% in North Africa) but fluently speaking Italian. Socio-economic status was assessed at a household level, asking adolescents about their parents’ employment. 22.5% of parents were high-qualified professionals, 16.5% clerks, 13% workers, 9.1% of parents were businessmen or managers, 8.7% technical professionals, 4.8% dealers, 3.5% belonged to military forces, 2.6% others, while 19.3% of adolescents did not report their parents’ job.

Procedure

All students participated voluntarily. The survey was designed to respect privacy and anonymity, ensuring information confidentiality and aggregated data. Signed consent, with the description of the research purpose, was provided from participants’ parents. Adolescents completed the paper and pencil version of the self-reports in their classrooms during school hours. Completion required between 40- and 50-min. Data were collected before the COVID-19 pandemic by M.A. students attending their degree in clinical psychology, supervised during data collection by a senior researcher. The present research procedure complied with APA ethical standards in the treatment of participants, and the study was conducted following the Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects (Declaration of Helsinki). Data analyses were performed by IBM SPSS v.24.

Measures

The Adolescent Personality Structure Questionnaire (APS-Q; Benzi et al., 2021) is a self-report measure consisting of 35 items that assess personality structure in adolescence according to 7 dimensions: Sense of Self, Self-acceptance, Sexuality, Investments and Goals, Relationship with Family, Relationship with Friends, and Aggression. For each item, the questionnaire asks participants to rate their level of agreement on a 5-point scale (1 = Never true to 5 = Always true). The APS-Q is developed based on the Interview of Personality Organization Processes in Adolescence (IPOP-A; Fontana et al., 2020), a semi-structured interview based on the object relations approach to personality pathology that was explicitly created for evaluating personality functioning in adolescence (Kernberg et al., 2000). The APS-Q is a reliable and practical measure to assess personality functioning in clinical and non-referred settings, evidencing convergent and incremental validity with existing measures of severity of personality pathology, maladaptive personality traits, and psychological distress. Sense of Self measures stability and clarity of the self-image and ability to mentalize internal states and behaviors; Self-acceptance encompasses acceptance of physical development or the presence of shame; Aggression evaluates the capacity to regulate aggression or, on the contrary, the tendency to acting-out toward self or others; Investments and goals indicates the presence and stability of goals and investments in school; Relationship with Family measures the quality of the relations inside the familiar context; Sexuality refers to how adolescents are comfortable with their sexual desires/impulses, and Relationship with Friends evaluates the capacity to build intimate and significant relationships with friends. Higher scores on the APS-Q scales indicate an increasing impairment in the dimension investigated. In general, the reliabilities of the APS-Q scales ranged from acceptable to good (Cronbach’s α ranging from .63 to .82).

The Internet Addiction Test (IAT; Young, 1998; Fioravanti & Casale, 2015) assesses the presence of Internet Addiction and the severity of symptomatology and compulsiveness among adults and adolescents. The IAT is a self-report questionnaire structured in 20 items evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale. Internet Addiction is a disorder of impulse control, with the term ‘Internet’ referring to any online activity. The 20 items of the questionnaire measure the aspects and behaviors associated with compulsive internet use that include: compulsiveness, escape, and addiction, and IAT items also investigate the impact of problematic internet use on personal and interpersonal functioning. The scoring is calculated by summing together the scores of each response. Higher IAT total score indicates increasing problematic internet use. Scores ranging between 0 and 30 indicate subjects that do not have problems using the Internet, scores between 31 and 49 indicate the presence of a moderate form of Internet Addiction, as these people may occasionally surf the Internet but still have adequate control of their use, scores between 50 and 79 point out problems related to the impact that network use has on the subject’s life. Finally, scores ranging between 80 and 100 indicate that pathological Internet use causes major addiction problems and negatively impacts the subject’s life. For the aim of the present study, we used only the IAT total score, which showed good internal consistency (α = .87).

The Youth Self Report (YSR, Achenbach, 1991; Ivanova et al., 2007) is a self-report questionnaire covering behavioral and emotional problems in the past six months of an adolescent’s life. It contains 112 problem items scored on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“not true”) to 1 (“somewhat or sometimes true”) to 2 (“very or often true”), which refer to eight First-Order scales like Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, Rule-Breaking Behavior, and Aggressive Behavior, and six DSM-Oriented scales. Measurement invariance was found between youth self-ratings across 19 different societies (Ivanova et al., 2019). This study employed only the Second-Order scales Internalizing and Externalizing Problems. As also indicated by Mathyssek et al. (2012), the Internalizing Problems score is the sum of the three scales Anxious/Depressed, Somatic Complaints and Withdrawn, thus assessing anxious (“I am nervous or tense”), withdrawn (“I am too shy”), and somatic symptoms (“I am overly tired without a clear cause”). Externalizing Problems consists of the sum of two scales, Aggressive Behavior, and Rule-Breaking Behavior, thus assessing aggressive (“I fight a lot”) and rule-breaking behaviors (“I lie or cheat”). Higher scores on these two domains indicate an increasing presence of internalizing and externalizing problems. For the aim of the present study, we used only Internalizing and Externalizing Problems scales, which showed good internal consistency (α = .85 and .84).

Data Analyses

To test whether maladaptive personality functioning was associated with psychopathology symptoms, we computed Pearson’s correlations between the APS-Q scales and the YSR Internalizing and Externalizing Problems. To test whether the level of internet addiction would moderate the effect of personality dimensions on the adolescent’s psychopathological problems, we performed a series of moderation analyses following Hayes’ (2013) recommendation for generating conditional effects of the moderator (PROCESS). We considered the seven APS-Q subscales (Sense of Self, Self-acceptance, Sexuality, Investments and Goals, Relationship with Family, Relationship with Friends, and Aggression) as separate independent variables, the YSR Externalizing and Internalizing Problems scales as the dependent variables, and IAT Total Score as the moderator, controlling for gender as covariates. Significant interactions were decomposed using simple slope analyses at low (-1SD), Medium, and High (+1SD) of the moderator. However, to better understand the moderator’s value at which the effect of the predictor was significant or not, we used the Johnson-Neyman technique. We centered variables before the analyses, but we reported raw values for the Johnson-Neyman technique and the figures for easiness of reading results.

Results

Correlations between Maladaptive Personality Functioning and Internalizing/Externalizing Problems

The associations between the seven APS-Q scales and the YSR Internalizing and Externalizing Problems scales are reported in Table 1. Overall, the pattern of correlations indicates that all the APS-Q scales except Aggression and Relationship with Friends are associated with greater internalizing problems. Moreover, all the APS-Q scales except Self-acceptance and Relationship with Friends are associated with greater externalizing problems.

Table 1.

Correlations between the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) and Adolescent Personality Structure Questionnaire (APS-Q) and Youth Self Report 11–18 (N = 231)

| YSR | IAT Total score | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Internalizing | Externalizing | ||

| APS-Q | |||

| Sense of Self | .51*** | .35*** | .27*** |

| Self-Acceptance | .57*** | .09 | .18** |

| Sexuality | .15* | −.27*** | .16** |

| Investments and Goals | .17** | .12* | .35*** |

| Relationship with Family | .23** | .34*** | .29*** |

| Relationship with Friends | .08 | −.06 | .05 |

| Aggression | .12 | .53*** | .34*** |

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

Moderation of the Personality Functioning – Internalizing/Externalizing Problems Association by the Level of Problematic Internet Use

We adopted a moderation model to test whether the Internet Addiction Total Score moderated the effect of any APS-Q scales on the YSR scales. Not all the moderation models examined were significant (see Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Conditional effect of maladaptive personality functioning (APS-Q) on Internalizing Problems (YSR) for levels of Internet Addiction (IAT Total Score)

| B | SE | t | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of Self | 5.75 | 0.66 | 8.78*** | [4.46, 7.04] |

| IAT Total Score | 4.87 | 1.47 | 3.32*** | [1.98, 7.77] |

| Sense of Self X IAT | −1.73 | 0.55 | −3.16** | [−2.81,-0.65] |

| Regression Model R2 | .35*** | |||

| Δ R2 | .03** | |||

| Conditional Effect on YSR Internalizing Problems: | ||||

| Low IAT score: 30 | 7.48 | 0.80 | 9.36*** | [5.91, 9.06] |

| Sense of Self X Med IAT score: 42 | 5.75 | 0.66 | 8.78*** | [4.46, 7.04] |

| High IAT score: 53 | 4.02 | 0.91 | 4.44*** | [2.24, 5.81] |

| Self-Acceptance | 5.05 | 0.57 | 9.58*** | [4.37, 6.63] |

| IAT Total Score | 0.65 | 1.74 | 0.38 | [−2.77, 4.08] |

| Self-Acceptance X IAT | 0.11 | 0.64 | 0.17 | [−1.16,1.38] |

| Sexuality | 1.14 | 0.74 | 1.53 | [−0.32, 2.61] |

| IAT Total Score | 3.30 | 1.80 | 1.83 | [−0.25, 6.86] |

| Sexuality X IAT | −0.76 | 0.73 | −1.03 | [−2.21, 0.67] |

| Investment and Goals | 1.00 | 0.76 | 1.33 | [−0.49, 2.49] |

| IAT Total Score | 1.66 | 1.75 | 0.95 | [1.79, 5.12] |

| Investment and Goals X IAT | −0.11 | 0.63 | −0.17 | [−1.36, 1.14] |

| Relationship with Family | 3.85 | 0.92 | 4.19*** | [2.04, 5.65] |

| IAT Total Score | 4.52 | 2.38 | 1.90 | [−0.18, 9.22] |

| Relationship with Family X IAT | −1.14 | 0.80 | −1.41 | [−2.72, 0.44] |

| Relationship with Friends | 0.83 | 0.70 | 1.18 | [−0.55, 2.22] |

| IAT Total Score | −1.61 | 1.54 | −1.05 | [−4.64, 1.41] |

| Relationship with Friends x IAT | 1.51 | 0.61 | 2.48** | [0.31, 2.71] |

| Regression Model R2 | .14*** | |||

| Δ R2 | .024** | |||

| Conditional Effect on YSR Internalizing Problems: | ||||

| Low IAT score: 30 | −0.66 | −0.99 | −0.67 | [−2.63, 1.29] |

| Relationship with Friends x Med IAT score: 42 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 1.18 | [−0.55, 2.22] |

| High IAT score: 53 | 2.34 | 0.86 | 2.72** | [0.64, 4.04] |

| Aggression | 1.99 | 0.86 | 2.32* | [0.30, 3.67] |

| IAT Total score | 4.61 | 1.34 | 3.46*** | [1.98, 7.25] |

| Aggression X IAT | −1.79 | 0.65 | −2.74** | [−3.07, −0.50] |

| Regression Model R2 | .12*** | |||

| Δ R2 | .03** | |||

| Conditional Effect on YSR Internalizing Problems: | ||||

| Low IAT score: 30 | 3.78 | 1.27 | 2.98** | [1.28, 6.27] |

| Aggression X Med IAT score: 42 | 1.99 | 0.86 | 2.32* | [0.30, 3.67] |

| High IAT score: 53 | 0.20 | 0.84 | 0.24 | [−1.46, −1.86] |

*** p ≤ .001; **p ≤ .01; *p ≤ .05

YSR = Youth Self-Report questionnaire; IAT = Internet Addiction Test; CI=Confidence Interval. IAT moderator values represent the mean and ± 1 SD of the total score

For the model where Relationship with Friends was the independent variable: F4,228 = 8.76; for the model where Sense of Self was the independent variable: F4,230 = 31.03; for the model where Aggression was the independent variable: F4,230 = 7.55

Gender as a covariate: for the model where Relationship with Friends was the independent variable: B = 5.07, p = .001, CI = [2.66, 7.48]; for the model where Sense of Self was the independent variable: B = 4.86, p = .001, CI = [2.78, 6.94]; for the model where Aggression was the independent variable: B = 5.25, p = .001, CI = [2.73, 7.77]

Table 3.

Conditional effect of maladaptive personality functioning (APS-Q) on Externalizing Problems (YSR) for levels of Internet Addiction (IAT Total Score)

| B | SE | t | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of Self | 4.07 | 0.63 | 6.48*** | [2.83, 5.31] |

| IAT Total Score | 1.43 | 1.41 | 1.02 | [−1.34, 4.21] |

| Sense of Self X IAT | 0.01 | 0.52 | 0.02 | [−1.02, 1.04] |

| Self-Acceptance | 0.72 | 0.59 | 1.22 | [−0.44, 1.89] |

| IAT Total Score | 5.19 | 1.79 | 2.90** | [1.66, 8.73] |

| Self-Acceptance X IAT | −1.19 | 0.66 | −1.80 | [−2.51, 0.11] |

| Sexuality | −3.14 | 0.62 | −5.06*** | [−4.37, −1.92] |

| IAT Total Score | 4.15 | 1.50 | 2.76** | [1.19, 7.12] |

| Sexuality X IAT | −0.66 | 0.61 | −1.08 | [−1.87, 0.54] |

| Investment and Goals | 0.69 | 0.66 | 1.03 | [−0.61, 1.99] |

| IAT Total Score | 0.77 | 1.53 | 0.50 | [−2.26, 3.79] |

| Investment and Goals X IAT | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.88 | [−0.60,1.58] |

| Relationship with Family | 3.12 | 0.81 | 3.86*** | [1.53, 4.71] |

| IAT Total Score | 0.04 | 2.10 | 0.02 | [−4.10, 4.20] |

| Relationship with Family X IAT | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.87 | [−0.78, 2.01] |

| Relationship with Friends | −1.10 | 0.62 | −1.75 | [−2.33, 0.14] |

| IAT Total Score | 2.24 | 1.37 | 1.64 | [−0.45, 4.94] |

| Relationship with Friends x IAT | 0.11 | 0.54 | 0.21 | [−0.95, 1.18] |

| Aggression | 5.57 | 0.64 | 8.68*** | [4.31, 6.84] |

| IAT Total score | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0.13 | [−1.84, 2.10] |

| Aggression X IAT | 0.25 | 0.49 | 0.51 | [−0.72, 1.21] |

*** p ≤ .001; **p ≤ .01; *p ≤ .05

YSR = Youth Self-Report questionnaire; IAT = Internet Addiction Test; CI=Confidence Interval

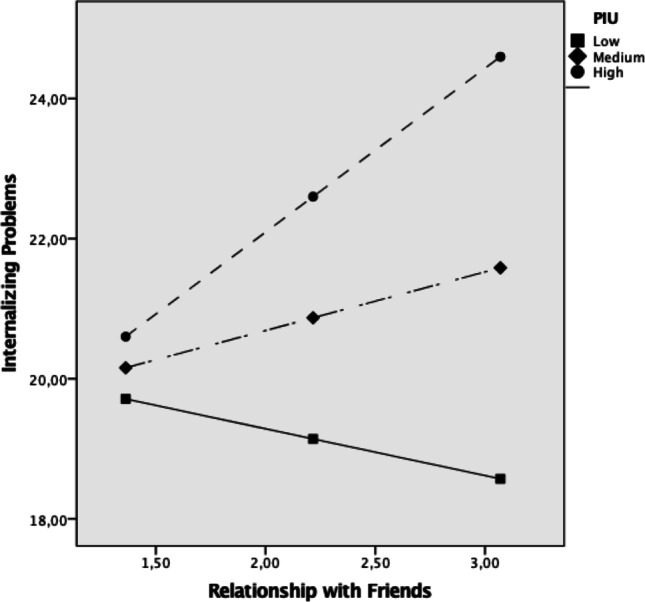

First, difficulties in Relationship with Friends predicted Internalizing Problems severity only high levels of problematic internet use (high IAT Total Score), but not at a medium or low level of problematic internet use (low and medium IAT Total Score) (Table 2; Fig. 1). Specifically, the Johnson-Neyman technique showed that difficulties in their relationships with friends were no longer associated with Internalizing Problems for adolescents with the IAT Total Score below 46. In other words, difficulties in Relationship with Friends predicts increasing Internalizing Problems only for adolescents who showed greater problematic internet use.

Fig. 1.

Interaction between Relationship with Friends (APS-Q) and level of Problematic Internet Use (IAT – Total Score) for predicting Internalizing Problems in the Youth Self Report 11–18 (YSR)

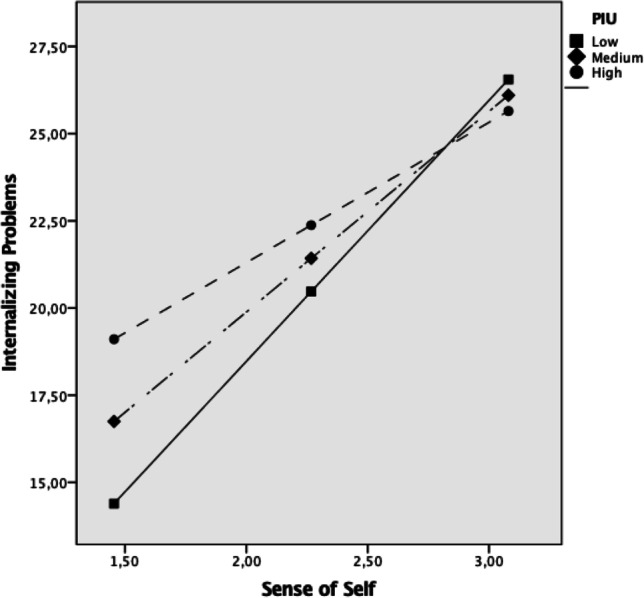

Second, difficulties in Sense of Self predicted greater Internalizing Problems, but its impact was the lowest at higher levels of PIU (higher IAT Total Score); the magnitude of the conditional effect of difficulties in Sense of Self on Internalizing Problems increased when moving from high to medium to low IAT Total Scores (Table 2; Fig. 2). In particular, the Johnson-Neyman technique showed that greater difficulties in Sense of Self were associated with greater Internalizing Problems only at IAT Total Score values below 62.

Fig. 2.

Interaction between Sense of Self (APS-Q) and level of Problematic Internet Use (IAT – Total Score) for predicting Internalizing Problems in the Youth Self Report 11–18 (YSR)

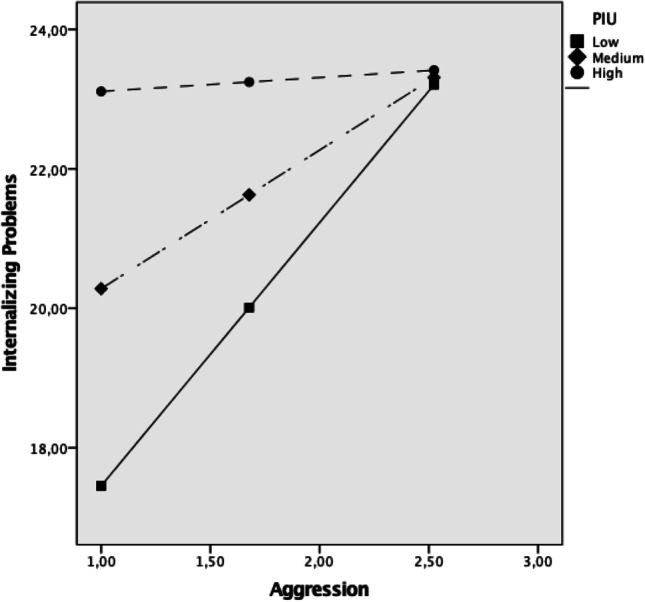

Third, Aggression was significantly associated with increased severity of Internalizing Problems only among adolescents with low and medium PIU (low and medium IAT Total Score). Conversely, Aggression was unrelated to Internalizing Problems for adolescents who exhibited greater PIU difficulties (Table 2; Fig. 1). The Johnson-Neyman technique clarified that greater Aggression was associated with greater Internalizing Problems only for adolescents with an IAT Total Score below 43.

Briefly, difficulties in PIU (IAT Total Score) moderated the association between maladaptive personality functioning and Internalizing Problems in different ways. For example, greater PIU enhanced the relationship between difficulties in Relationship with Friends and Internalizing Problems. At the same time, PIU buffers the relationship between difficulties in Sense of Self and Internalizing Problems and the association between Aggression regulation and Internalizing Problems.

Discussion

This study explored the role of PIU in the relationship between personality functioning and psychological problems in adolescence. More specifically, we investigated if the relationship between maladaptive personality dimensions and internalizing/externalizing symptoms changed because of adolescents’ inability to control their Internet use, expecting that the relationship between maladaptive personality functioning and externalizing/internalizing problems would be positive and stronger when PIU is higher (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Interaction between Aggression (APS-Q) and level of Problematic Internet Use (IAT – Total Score) for predicting Internalizing Problems in the Youth Self Report 11–18 (YSR)

First, we investigated the associations between personality functioning and externalizing/internalizing problems. Recently, Sharp and Wall (2018) reviewed the research on personality pathology in adolescence and suggested a developmental model for psychopathology that underlines the crucial relationship between internalizing/externalizing symptoms and maladaptive personality. The pattern of the associations found in our sample is coherent with this model.

Second, data highlighted the specificity of the relationship between the quality of interpersonal relationships and PIU, in line with the adolescent-specific need for social exploration and experimentation of new contexts and situations (Casey et al., 2008).

Indeed, it seems like, considering personality functioning, the dimension of externalizing symptoms, which also include aspects of addiction and conduct disorders, is not affected by the presence of PIU. This result may be explained by the intrinsic characteristic of PIU, namely that of the virtual-only relationships. However, one could then discuss the importance of identifying a “quality of online relationships”. This could be beneficial for clinicians and researchers, considering the prevalence of this phenomenon among adolescents who, even when not in the presence of PIU, spend a lot of time experimenting and building peer relationships in the online world (Spada, 2014).

However, the role played by PIU in the relationship between personality pathology and internalizing symptoms is different. The first interesting point is that the association between the quality of the relationships with peers and internalizing symptoms (i.e. anxious-depressive symptoms, somatic complaints and withdrawn) is significant only at a pathological level of PIU. As we have pointed out, the quality of peer relationships represents an essential factor for developing a stable and integrated personality in adolescence (Kernberg et al., 2000). Therefore, it seems that a significant high PIU exacerbates the presence of anxious-depressive symptomatology, somatic complaints and withdrawn with its relationship with difficulties in building intimate interpersonal relations.

Contrary to what was expected, we found a buffer effect of the presence of PIU that affects the relationship between the adolescent’s ability to get in touch with his thoughts, emotions, and behaviors (Sense of Self) and the presence of internalizing symptoms. In line with Gioia et al. (2021), this result may mean that for adolescents a dysregulated online experience represents a maladaptive coping strategy useful to regulate the relationships between identity difficulties and anxiety, depressive and somatic complaints. Another buffer effect of the presence of PIU is that which also is linked to the relationship between the ability to regulate aggression and internalizing symptoms. Here, the background effect exerted by the presence of PIU emerges. The regulation of aggression (self-and other-directed, as well as imagined and acted out) represents an essential factor in adolescents’ ability to cope with this developmental phase’s emotional storms. It appears that the presence of low to moderate PIU favors the occurrence of internalizing symptoms and rage dysregulation, while this occurrence becomes non-significant at high level of PIU. Here, again, we could interpret PIU as a maladaptive coping strategy that helps adolescents to contain anxiety, depression and withdrawn associated to aggressive feelings toward others. Furthermore, it would be interesting to investigate the specific quality of aggression related to these psychological problems, perhaps amplified by the use of video games or antisocial quality behaviors within the online world (Selfhout et al., 2009).

The results of this study may be better understood within the context of its limitations. For example, the use of self-report measures may not have adequately delved into the quality of the PIU experience. In a future study, it would be helpful to use methodologies such as the experience sampling method (ESM) that allows for a more three-dimensional exploration of adolescents’ daily experience through an intensive longitudinal type of study. Moreover, our results may be limited from the observation of this specific sample, albeit numerically representative: in this direction, the authors favor the importance of replicating observations on different samples. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design of the study precludes any inference on causality among the study variables. Longitudinal studies could clarify how increasing adolescent inability to control their internet use should impact on the relationship between personality functioning and internalizing/externalizing symptoms. Finally, as Wu and Zumbo (2008) noted, a moderator is a relatively stable trait or disposition rather than a fluctuating state. However, looking to Strittmatter et al. (2016) study, the stability of PIU over time is questionable, advocates for a transient nature of PIU. On the contrary, Gentile et al. (2011) report different adolescent trajectories over two years with transient, stable, increasing PIU and a class of adolescents that never involved in PIU. In light of these studies, our results need to be replicated in different samples of adolescents, considering the differences in the stability of PIU. In future research, we expect higher and stable PIU to amplify the relationship between difficulties in creating significant bonds with peers and internalizing symptoms. At the same time, a more transient PIU would act as a regulatory strategy between the sense of self and aggression from one side and internalizing symptoms from the other side.

Clinical Implications

Overall, these findings emphasize the importance of considering possible applications to clinical work with adolescents (Ammaniti et al., 2015; Parolin et al., 2017). Namely, they encourage accurately evaluating PIU as a risk factor in adolescence: (1) considering how high PIU’s presence should impact the relationship between adolescent personality and the quality of their relationships with peers; (2) acknowledging the role of PIU as a regulation strategy for identity difficulties and aggression dysregulation. The first point underlines the importance of focusing in clinical work with adolescents on the presence of a high PIU. A high PIU amplifies the link between difficulty in building intimate and deep bonds with peers and intense feelings of anxiety and sadness, creating maladaptive interpersonal cycles in an adolescent’s life. Therefore, clinicians should pay particular attention to the presence of PIU in light of its role as a retreat from relational experiences outside the family and its consequences on anxious-depressive feelings. The second point can be fascinating considering clinical practice: an increasing problematic internet use diminishes the strength of the relationship between identity difficulties/rage dysregulation and internalizing symptoms representing a regulation strategy. This point should help understand why teenagers struggle to stop their problematic internet use despite its adverse effects on their psychological functioning and relationships outside the family (Montag & Reuter, 2017).

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist and 1991 profile. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ammaniti M, Fontana A, Nicolais G. Borderline personality disorder in adolescence through the lens of the interview of personality organization processes in adolescence (IPOP-A): Clinical use and implications. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy. 2015;14(1):82–97. doi: 10.1080/15289168.2015.1003722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson EL, Steen E, Stavropoulos V. Internet use and problematic internet use: A systematic review of longitudinal research trends in adolescence and emergent adulthood. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2017;22(4):430–454. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2016.1227716. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benzi I, Sarno I, Di Pierro R. Maladaptive personality functioning and non-suicidal self injury in adolescence. Clinical Neuropsychiatry: Journal of Treatment Evaluation. 2018;15(4):215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Benzi IMA, Di Pierro R, De Carli P, Cristea IA, Cipresso P. All the faces of research on borderline personality pathology: Drawing future trajectories through a network and cluster analysis of the literature. Journal of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies. 2020;20(2):3–30. doi: 10.24193/jebp.2020.2.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benzi, I. M. A., Fontana, A., Di Pierro, R., Perugini, M., Cipresso, P., Madeddu, F., Clarkin, J. F., & Preti, E. (2021). Assessment of personality functioning in adolescence: Development of the adolescent personality structure questionnaire. Assessment. Advance online publication. 10.1177/1073191120988157. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Block JJ. Issues for DSM-V: Internet addiction. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(3):306–307. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07101556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan SE. Relations among loneliness, social anxiety, and problematic internet use. Cyberpsychology & Behavior. 2006;10(2):234–242. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Getz S, Galvan A. The adolescent brain. Developmental Review. 2008;28(1):62–77. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanen AM, McCutcheon LK, Jovev M, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD. Prevention and early intervention for borderline personality disorder. Medical Journal of Australia. 2007;187(S7):S18–S21. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebesutani C, Bernstein A, Nakamura BJ, Chorpita BF, Higa-McMillan CK, Weisz JR, The Research Network on Youth Mental Health Concurrent validity of the child behavior checklist DSM-oriented scales: Correspondence with DSM diagnoses and comparison to syndrome scales. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2010;32(3):373–384. doi: 10.1007/s10862-009-9174-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A, Callea A, Casini E, Curti V. Rejection sensitivity and internet addiction in adolescence: Exploring the mediating role of emerging personality disorders. Clinical Neuropsychiatry: Journal of Treatment Evaluation. 2018;15(4):206–214. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, A., Ammaniti, M., Callea, A., Clarkin, A., Clarkin, J.F., & Kernberg, O.F. (2020). Development and validation of the interview of personality organization processes in adolescence (IPOP-A). Journal of Personality Assessment. Advance online publication. 10.1080/00223891.2020.1753753. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gámez-Guadix M. Depressive symptoms and problematic internet use among adolescents: Analysis of the longitudinal relationships from the cognitive–behavioral model. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking. 2014;17(11):714–719. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile DA, Choo H, Liau A, Sim T, Li D, Fung D, et al. Pathological video game use among youths: A two-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):e319–e329. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioia F, Rega V, Boursier V. Problematic internet use and emotional dysregulation among young people: A literature review. Clinical Neuropsychiatry: Journal of treatment Evaluation. 2021;18(1):41–54. doi: 10.36131/cnfioritieditore20210104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanelli A, Ozer EM, Dahl RE. Leveraging technology to improve health in adolescence: A developmental science perspective. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020;67(2):S7–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Billieux J, Pontes HM. The evolution of internet addiction: A global perspective. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;53:193–195. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross EF, Juvonen J, Gable SL. Internet use and well-being in adolescence. Journal of Social Issues. 2002;58(1):75–90. doi: 10.1111/1540-4560.00249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guinta MR, John RM. Social media and adolescent health. Pediatric Nursing. 2018;44(4):196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova MY, Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA, Dumenci L, Almqvist F, Bilenberg N, Erol N. The generalizability of the youth self-report syndrome structure in 23 societies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:729–738. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova MY, Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA, Guo J, Althoff RR, Kan K-J, Almqvist F, Begovac I, Broberg AG, Chahed M, da Rocha MM, Dobrean A, Döepfner M, Erol N, Fombonne E, Fonseca AC, Forns M, Frigerio A, Grietens H, et al. Testing syndromes of psychopathology in parent and youth ratings across societies. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2019;48(4):596–609. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2017.1405352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardefelt-Winther D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;31:351–354. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg P, Weiner A, Bardenstein K. Personality disorders in children and adolescence. Basic Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Davis KE. Toward a comprehensive theory of problematic internet use: Evaluating the role of self-esteem, anxiety, flow, and the self-rated importance of internet activities. Computers in Human Behavior. 2009;25(2):490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2008.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, LaRose R, Peng W. Loneliness as the cause and the effect of problematic internet use: The relationship between internet use and psychological well-being. Cyberpsychology & Behavior. 2009;12(4):451–455. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger J. Why is identity achievement so elusive? Identity. 2007;7(4):331–348. doi: 10.1080/15283480701600793. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laconi S, Vigouroux M, Lafuente C, Chabrol H. Problematic internet use, psychopathology, personality, defense and coping. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;73:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathyssek CM, Olino TM, Verhulst FC, van Oort FV. Childhood internalizing and externalizing problems predict the onset of clinical panic attacks over adolescence: The TRAILS study. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milani L, Osualdella D, Di Blasio P. Quality of interpersonal relationships and problematic internet use in adolescence. Cyberpsychology & Behavior. 2009;12(6):681–684. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2009.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montag C, Reuter M. Internet addiction. Neuroscientific approaches and Therapeutical implications including smartphone addiction (Second Edition) Springer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Parolin L, De Carli P, Solomon F, Locati F. Emotional aspects of metacognition in anxious rumination: Clues for understanding the psychotherapy process. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. 2017;27(4):561–576. doi: 10.1037/int0000085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reich SM, Subrahmanyam K, Espinoza G. Friending, IMing, and hanging out face-to-face: Overlap in adolescents' online and offline social networks. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48(2):356–368. doi: 10.1037/a0026980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rücker J, Akre C, Berchtold A, Suris JC. Problematic internet use is associated with substance use in young adolescents. Acta Paediatrica. 2015;104(5):504–507. doi: 10.1111/apa.12971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selfhout MH, Branje SJ, Delsing M, ter Bogt TF, Meeus WH. Different types of internet use, depression, and social anxiety: The role of perceived friendship quality. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32(4):819–833. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp C, Wall K. Personality pathology grows up: Adolescence as a sensitive period. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2018;21:111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siomos KE, Dafouli ED, Braimiotis DA, Mouzas OD, Angelopoulos NV. Internet addiction among Greek adolescent students. Cyberpsychology & Behavior. 2008;11(6):653–657. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spada MM. An overview of problematic internet use. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(1):3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepp SD, Lazarus SA, Byrd AL. A systematic review of risk factors prospectively associated with borderline personality disorder: Taking stock and moving forward. Personality disorders: Theory, research, and treatment. 2016;7(4):316–323. doi: 10.1037/per0000186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strittmatter E, Parzer P, Brunner R, et al. A 2-year longitudinal study of prospective predictors of pathological internet use in adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016;25:725–734. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0779-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigna-Taglianti F, Brambilla R, Priotto B, Angelino R, Cuomo G, Diecidue R. Problematic internet use among high school students: Prevalence, associated factors and gender differences. Psychiatry Research. 2017;257:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu AD, Zumbo BD. Understanding and using mediators and moderators. Social Indicators Research. 2008;87(3):367–392. doi: 10.1007/s11205-007-9143-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.