Abstract

Acer L. (Sapindaceae) is one of the most diverse and widespread plant genera in the Northern Hemisphere. It comprises 124–156 recognized species, with approximately half being native to Asia. Owing to its numerous morphological features and hybridization, this genus is taxonomically and phylogenetically ranked as one of the most challenging plant taxa. Here, we report the complete chloroplast genome sequences of five Acer species and compare them with those of 43 published Acer species. The chloroplast genomes were 149,103–158,458 bp in length. We conducted a sliding window analysis to find three relatively highly variable regions (psbN-rps14, rpl32-trnL, and ycf1) with a high potential for developing practical genetic markers. A total of 76–103 SSR loci were identified in 48 Acer species. The positive selection analysis of Acer species chloroplast genes showed that two genes (psaI and psbK) were positively selected, implying that light level is a selection pressure for Acer species. Using Bayes empirical Bayes methods, we also identified that 20 cp gene sites have undergone positive selection, which might result from adaptation to specific ecological niches. In phylogenetic analysis, we have reconfirmed that Acer pictum subsp. mono and A. truncatum as sister species. Our results strongly support the sister relationships between sections Platanoidea and Macrantha and between sections Trifoliata and Pentaphylla. Moreover, series Glabra and Arguta are proposed to promote to the section level. The chloroplast genomic resources provided in this study assist taxonomic and phylogenomic resolution within Acer and the Sapindaceae family.

Keywords: Acer, chloroplast genome, sequence divergence, structural variation, phylogenetics

1 Introduction

With the rapid development of next-generation sequencing (NGS), the increasing chloroplast (cp) genome sequences of land plants offer comprehensive comparison in genome structure, horticultural improvement in plant breeding (Sonah et al., 2011; Xiong et al., 2015), and phylogenetic reconstruction (Cai et al., 2015; Ruhsam et al., 2015). The cp genome is maternally inherited with high copy numbers per cell, despite being much smaller than other genomes (Yi et al., 2013). The cp genome is commonly used in evolution and phylogenomic analysis, providing supplementary information hidden in nuclear genomes regarding, for instance, ancient taxa histories and population-area relationships (Timme et al., 2007; Zeb et al., 2019). The cp genome’s relatively conserved features make it being broadly applied to plant systematics, biodiversity, biogeography, adaptation, etc. (Wambugu et al., 2015; Brozynska et al., 2016).

Acer L. (Maple), composed of more than 124 species, is a diverse genus within the Sapindaceae L. family (Xu et al., 2008), which are primarily deciduous and distributed in temperate Asia, Europe, and North America (van Gelderen et al., 1994; Renner et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2008). Many Acer species provide important economic products, such as timber, furniture, and herbal medicines, especially gamma-linolenic acid, and the genus also includes many famous horticultural plants (Bi et al., 2016). Moreover, some Acer species are dominant in several forests, responsible for fundamental ecosystem processes (Bishop et al., 2015). High variable leaf characters and complex reproductive characteristics hinder Acer’s systematic classification (Cronquist, 1979; Rosado et al., 2018). An accurate phylogeny can facilitate the sustainable utilization of wild genetic resources (Xu et al., 2008). Previously, the phylogenetic trees of Acer have been reconstructed by cambial peroxidase isozymes (Santamour, 1982), restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) markers (Pfosser et al., 2002), cp DNA and nuclear DNA (Cho et al., 1996; Ackerly and Donoghue, 1998; Li et al., 2006; Renner et al., 2008; Li et al., 2019; Gao et al., 2020), and cp genome (Areces-Berazain et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020; Areces-Berazain et al., 2021). However, limited informative sites, taxa, and evolution models used for the phylogenetic analyses led to the phylogenetic relationship being poorly resolved. Therefore, large-scale plastome data is necessary to acquire a maximum phylogenetic signal in Acer.

In this study, we compiled a dataset with the cp genomes of 48 Acer species, five of which were newly generated in this study (A. palmatum, A. wilsonii, A. flabellatum, A. sino-oblongum, and A. laevigatum). Because of the importance of plastomes in systematics, it is necessary to confirm these plastomes’ gene order and sequence homology. Therefore, by comparing plastome studies, we aimed: 1) to determine the gene order and gene content of Acer cp genomes, 2) to identify divergence hotspots and the positive selective genes in the cp genomes, and 3) to reconstruct the phylogenomic relationships of Acer species.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Sampling and DNA Extraction

Young leaves of five Acer species (A. palmatum, A. wilsonii, A. flabellatum, A. sino-oblongum, and A. laevigatum) were collected and dried immediately with silica gel for DNA extraction with the modified CTAB method (Doyle, 1987). The sampling information is shown in Supplementary Table S1. Species identification was followed by Maples of the World (van Gelderen et al., 1994) and Flora of China (Xu et al., 2008). Voucher specimens were deposited at the College of Forestry, Beijing Forestry University, China.

2.2 Chloroplast Genome Sequencing, Assembling, and Annotation

Purified genomic DNA was sequenced using an Illumina MiSeq sequencer (Shanghai OE Biotech Co., Ltd.). A paired-end library was constructed with an insert size of 300 bp, yielding at least 8 GB of 150 bp paired-end reads for each species. Clean reads were obtained with NGSQC Toolkit v2.3.3 (cut-off read length for HQ = 70%, cut-off quality score = 20, trim reads from 5′ = 3, trim reads from 3′ = 7) (Dai et al., 2010). MITObim v. 1.8 (Hahn et al., 2013) was used to assemble the following reference cp genomes: A. buergerianum subsp. ningpoense (KF753631) (Yang et al., 2015), A. miaotaiense (KX098452) (Zhang et al., 2016), A. davidii (KU977442) (Jia et al., 2016), and A. morrisonense (KT970611) (Li et al., 2017). Annotation was performed using DOGMA (Wyman et al., 2004). Protein-encoding genes (PCG), tRNAs, rRNAs were annotated by BLAST searches (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) with manual adjustment error. The boundaries between the representative Acer cp genome regions were determined with the online tool IRscope (Amiryousefi et al., 2018), and ten representative species form main groups of Acer were highlighted.

2.3 Identifying Cp SSRs

MISA (MIcroSAtellite, http://pgrc.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/) was used to detect simple sequence repeats (SSRs) with criteria of minimal repeat numbers ten in mono-nucleotide SSR, four in di- and tri-nucleotide, and three in tetra-, penta-, and hexa-nucleotide SSRs motifs.

2.4 Divergence Hotspot Identification

Cp sequences were aligned by MAFFT (Katoh et al., 2005), and sliding window analysis was then used to estimate nucleotide variation (π) with 600-bp window length and 200-bp step size using DnaSP 5.0 (Librado and Rozas, 2009).

2.5 Positive Selected Analysis

The CodeML program in PAML 4.7.1 (Yang, 2007) was used to test the positive selection of Acer cp genes under the site-specific models. The dN, dS, and ω (= dN/dS) values were calculated with seqtype = 1, model = 0, Nssites = 0, 1, 2, 7, 8 based on 77 protein-coding genes shared by 48 Acer species. A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using whole cp genomes by PhyML v3.0 (Guindon et al., 2005). Likelihood ratio tests (LRT) were used to compare models between M1 (neutral) and M2 (positive selection) and between M7 (beta) and M8 (beta and ω). p-value was calculated using the internal CHI2 program in PAML 4.7.1 (Yang, 2007).

2.6 Phylogenomic Reconstruction

To reconstruct the phylogeny, 58 cp genome sequences comprising five new plastome sequences, 43 plastomes of Acer species from GenBank, and ten outgroup species were used (Supplementary Table S2). BioEdit version 7.1.11 (Hall, 1999) was used to align sequences with manual refinement and finally generated a total of 184,290 bp alignment length. The 5ʹ and 3ʹ ends of the sequences were trimmed to equal lengths for subsequent phylogenetic analyses. Phylogenetic relationships were reconstructed using Bayesian inference (BI), maximum likelihood (ML), and maximum parsimony (MP) by MrBayes 3.2 (Ronquist et al., 2012), PhyML v3.0 (Guindon et al., 2005), and PAUP*4.0b10 (Swofford, 2003), respectively. The best-fitting substitution model (GTR + I + G) was determined using Modeltest 3.7 (Posada and Buckley, 2004). In the Bayesian analyses, two independent Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) permutations were initiated. Each consisted of one cold and three heated MCMC chains for 108 generations and sampled every 104 generations. The first 2,000 trees were discarded as burn-in to ensure that the chains had become stationary. The ML analysis was initiated from a BIONJ tree, with support values for the nodes estimated by 1,000 bootstrap replicates. In the MP analysis, all character states were treated as unordered and equally weighted, and a heuristic search was performed with 1,000 replicates of random addition of sequences, tree-bisection-reconnection branch-swapping, and MULTREES. Bootstrap analysis was conducted in 1,000 replicates with the same heuristic search settings described above.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Choroplast Genome Organization of Acer

The nucleotide sequences of the 48 Acer cp genomes ranged from 149,103 bp (A. paxii) to 158,458 bp (A. caudatifolium) (Table 1). These cp genomes revealed a typical quadripartite structure similar to most angiosperms, with LSC, SSC, and IRs (IRa and IRb) regions. The LSC, SSC, and IR regions were 78,768–86,911 bp, 17,474–18,232 bp, and 25,508–26,798 bp long, respectively (Table 1). The guanine (G) and cytosine (C) proportion (GC%) varied from 37.5 to 38.1%, in which 34 species have a stable GC content of 37.9%. The GC content was higher in the IR region than the LSC and SSC regions.

TABLE 1.

General features of the Acer chloroplast genomes compared in this study.

| Species | Total (bp) | GC (%) | LSC (bp) | SSC (bp) | IR (bp) | Accession no |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acer acuminatum | 155,548 | 37.9 | 85,358 | 18,046 | 26,072 | MN864496 |

| Acer amplum | 156,225 | 37.9 | 86,121 | 18,066 | 26,019 | NC034932 |

| Acer buergerianum subsp. ningpoense | 156,911 | 37.9 | 85,315 | 18,094 | 26,751 | NC034744 |

| Acer caesium subsp. giraldii | 154,176 | 38.1 | 82,759 | 17,895 | 26,761 | MK479225 |

| Acer cappadocicum | 157,353 | 37.9 | 85,723 | 18,040 | 26,798 | NC051956 |

| Acer carpinifolium | 155,212 | 38.0 | 85,448 | 17,724 | 26,020 | MN864497 |

| Acer catalpifolium | 157,349 | 37.9 | 85,745 | 18,066 | 26,769 | MF179637 |

| Acer caudatifolium | 158,458 | 37.8 | 86,911 | 18,059 | 26,744 | MK479226 |

| Acer cinnamomifolium | 156,227 | 37.9 | 85,928 | 18,121 | 26,079 | NC056164 |

| Acer cissifolium | 155,997 | 37.9 | 85,790 | 18,051 | 26,078 | MW067037 |

| Acer davidii | 157,044 | 37.9 | 85,410 | 18,112 | 26,761 | KU977442 |

| Acer fenzelianum | 156,535 | 37.9 | 85,166 | 18,077 | 26,646 | NC045527 |

| Acer flabellatum | 156,472 | 37.9 | 84,876 | 18,088 | 26,754 | MF787384 a |

| Acer tataricum subsp. ginnala | 156,184 | 38.1 | 85,485 | 18,032 | 26,047 | MN864511 |

| Acer glabrum | 156,373 | 37.9 | 86,034 | 18,211 | 26,064 | MN864498 |

| Acer griseum | 156,857 | 37.9 | 85,227 | 18,134 | 26,748 | KY511609 |

| Acer henryi | 156,325 | 37.9 | 86,034 | 18,097 | 26,097 | MW067048 |

| Acer laevigatum | 156,905 | 37.9 | 85,323 | 18,084 | 26,749 | MF521832 a |

| Acer longipes | 157,137 | 37.9 | 85,531 | 18,068 | 26,769 | MG751775 |

| Acer lucidum | 157,612 | 38.1 | 86,838 | 18,094 | 26,340 | MK479214 |

| Acer mandshuricum | 156,234 | 37.9 | 86,043 | 18,059 | 26,066 | MW067055 |

| Acer miaotaiense | 156,595 | 37.9 | 86,327 | 18,068 | 26,100 | KX098452 |

| Acer micranthum | 156,399 | 37.9 | 86,147 | 18,128 | 26,062 | MN864500 |

| Acer morrisonense | 157,197 | 37.8 | 85,655 | 18,086 | 26,728 | KT970611 |

| Acer negundo | 155,938 | 37.9 | 85,678 | 18,092 | 26,084 | MN841452 |

| Acer nikoense | 156,082 | 37.9 | 85,866 | 18,148 | 26,034 | MN864499 |

| Acer nipponicum | 156,225 | 37.8 | 85,823 | 18,232 | 26,085 | MN864502 |

| Acer oblongum | 155,686 | 38.0 | 85,665 | 17,821 | 26,100 | NC056208 |

| Acer palmatum | 157,023 | 37.9 | 85,342 | 18,167 | 26,757 | KY457568 a |

| Acer paxii | 149,103 | 37.5 | 78,768 | 17,474 | 26,366 | MK479215 |

| Acer pentaphyllum | 156,220 | 37.9 | 85,938 | 18,148 | 26,067 | MN864505 |

| Acer pictum subsp. mono | 156,985 | 37.9 | 85,378 | 18,069 | 26,769 | MG751776 |

| Acer pilosum | 155,586 | 38.0 | 85,313 | 18,139 | 26,076 | MN864506 |

| Acer platanoides | 156,385 | 37.9 | 86,098 | 18,107 | 26,090 | NC051959 |

| Acer pseudosieboldianum | 157,053 | 37.9 | 85,392 | 18,169 | 26,746 | MW067066 |

| Acer robustum | 156,790 | 37.9 | 85,127 | 18,115 | 26,774 | MK479212 |

| Acer rubrum | 155,683 | 37.9 | 85,383 | 18,086 | 26,107 | MN864509 |

| Acer saccharum | 155,684 | 37.9 | 85,393 | 18,033 | 26,129 | NC051960 |

| Acer sino-oblongum | 157,121 | 37.9 | 85,558 | 18,119 | 26,722 | KY987160 a |

| Acer sterculiaceum subsp. sterculiaceum | 156,258 | 38.0 | 86,014 | 18,048 | 26,098 | MN864510 |

| Acer sutchuenense subsp. tienchuanense | 156,063 | 37.9 | 85,127 | 18,115 | 26,774 | NC049166 |

| Acer takesimense | 157,023 | 37.9 | 85,371 | 18,160 | 26,746 | NC046488 |

| Acer tegmentosum | 156,435 | 37.8 | 86,139 | 18,103 | 26,097 | NC056233 |

| Acer tetramerum | 154,078 | 38.1 | 83,199 | 17,895 | 26,492 | MK479228 |

| Acer truncatum | 156,262 | 37.9 | 86,019 | 18,073 | 26,085 | MH716034 |

| Acer wilsonii | 157,067 | 37.9 | 85,419 | 18,128 | 26,760 | MG012225 a |

| Acer yangbiense | 155,706 | 38.0 | 86,593 | 18,097 | 25,508 | MN315285 |

| Acer yangjuechi | 157,088 | 37.9 | 85,483 | 18,069 | 26,768 | MG770234 |

Sequences obtained in this study.

A total of 117 genes included four unique rRNAs, 31 tRNAs, and 82 PCGs (Table 2). Most cp genes were single copy, whereas 23 genes exhibited double copies, including four rRNA (4.5S, 5S, 16S, and 23S rRNA), nine tRNA genes (trnA-UGC, trnI-CAU, trnI-GAU, trnL-CAA, trnM-CAU, trnN-GUU, trnR-ACG, trnT-GGU, and trnV-GAC), and 10 PCG (ndhB, rpl2, rps12, rpl23, rps19, rps7, ycf1, orf42, ycf2, and ycf15). A total of 18 genes had introns, and three genes (ycf3, clpP, and rps12) contained two introns. Despite typically highly conserved, gene relocation and structural variation in IR and single-copy regions are very common (de Santana Lopes et al., 2018; Shearman et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2021). The cp genome structures of 10 representative Acer species are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Two main types of Acer species were recognized: the first group was represented by A. catalpifolium, A. buergerianum, A. negundo, whose LSC-IRB junction region comprised the rpl22 gene; the second group was composed of A. micranthum, A. lucidum, A. yangbiense, A. tataricum subsp. ginnala, A. carpinifolium, A. glabrum, and A. caesium, whose LSC-IRB junction comprised the rps19 or rpl2 gene regions, or the spacer region between rps19 and rpl2. The structure of the three species in the first group was relatively stable and had the same distance between rpl22 and the LSC-IRB junction. However, in the second group, the distance of rps19 and rpl2 from the LSC-IRB junction significantly varied. These structural pattern variations are similar to those of Saxifragaceae species (Li et al., 2019). Compared with the LSC-IRB junction, the SSC-IRB junction showed clear conservativeness, except for the deletion of pseudogene ycf1 (φ ycf1) in A. trigonatum. SSC-IRB junctions of Acer species were all located in the ycf1 gene, and the length of the ycf1 fragment in the IRB region was 1,244–1,284 bp. The length of the ndhF gene starting site from the SSC-IRB junction was 32–48 bp.

TABLE 2.

Genes present in the Acer chloroplast genome.

| Group of gene | Genes name |

|---|---|

| Photostsyem I | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ |

| Photostsyem II | psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbh, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbT, psbZ |

| Cytochrome b/f complex | petA, petB*, petD*, petG, petL, petN |

| ATP synthase | atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF*, atpH, atpI |

| NADH dehydrogenase | ndhA*, ndhB*, ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK |

| RubisCO large subunit | rbcL |

| RNA polymerase | ropA, ropB, ropC1*, ropC2 |

| Ribosomal proteins (SSU) | rps2, rps3, rps4, rps7, rps8, rps11, rps12**, rps14, rps15, rps16*, rps18, rps19 |

| Ribosomal proteins (LSU) | rpl2*, rpl14, rpl16*, rpl20, rpl22, rpl23, rpl32, rpl33, rpl36 |

| Other gene | clpP**, matK, accD, ccsA, infA, cemA |

| Proteins of unknown function | ycf1, ycf2, ycf3**, ycf4, ycf15 |

| ORFs | Orf42 |

| Transfer RNAs | 31 tRNAs (six contain a single intron) |

| Ribosomal RNAs | rrn4.5, rrn5, rrn16, rrn23 |

A single asterisk (*) preceding gene names indicate intron-containing genes, and double asterisks (**) preceding gene names indicate two introns in the gene.

3.2 SSRs Analysis of the Acer Cp Genomes

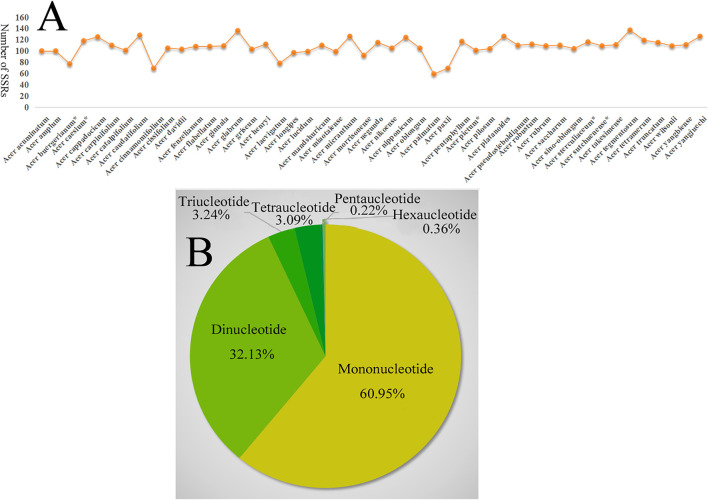

A total of 5,136 SSR loci were detected in the 48 Acer species, with the highest number in A. tegmentosum (137) and the lowest number in A. palmatum (59) (Figure 1A), in which six SSR types in A. negundo, five types in 21 species, four types in other 24 species, and three types in the remaining two species (A. palmatum and A. buergerianum). Most SSRs were mono- and di-nucleotide motifs; the former was the most abundant SSR type, being detected at 3,251 loci (60.95% of the total number), while 1,714 di-nucleotide repeats (32.13%) were detected. The least frequent type was penta-nucleotide, which was detected in only 12 loci in all Acer species (Figure 1B). The mono-nucleotide SSRs mostly comprised short polyA and polyT repeats, which have also been reported in other species, including Salvia miltiorrhiza (Lamiaceae) (Qian et al., 2013) and three Veroniceae species (Plantaginaceae) (Choi et al., 2016). Most SSRs were detected in intergenic regions. Within the coding regions, the SSRs were concentrated in ycf1 and ycf2, which is consistent with other species such as Cynara cardunculus (Curci et al., 2015) and Vigna radiata (Tangphatsornruang et al., 2009). Thus, the highly variable ycf1 coding region may potentially be applied as an alternative marker for plastid candidate barcodes to solve the phylogenetic controversy (Dong et al., 2015). SSR information may be crucial for understanding the genetic diversity status of Acer species worldwide.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Number of SSRs in the Acer species chloroplast genome. (B) Number of SSRS types of chloroplast genome in 48 Acer species.

3.3 Divergence Hotspot of Acer Species

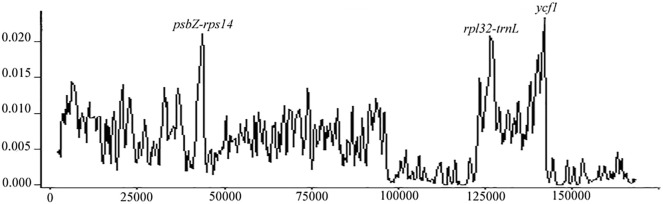

The sliding window analysis showed that nucleotide variability was higher in psbZ-rps14, rpl32-trnL, and ycf1 than in other regions (Figure 2). Maximum nucleotide polymorphism was 0.023, showing that those cp genomes were relatively conserved.

FIGURE 2.

Sliding-window analysis on the cp genomes for Acer species.

One highly variable region was found in the LSC region, and two were distributed in the SSC region, indicating the most stable region in the IR, followed by the LSC. In the Acer section Platanoidea, the trnH-psbA, psbN-trnD, psaA-ycf3, petA-psbJ, and ndhA introns were suggested as highly variable (Yu et al., 2020). With a comparison of 16 Acer, Areces-Berazain et al. (2020) defined the most variable regions in the SSC, in which ycf1, ndhF-rpl32, and rpl32-trnL had the highest nucleotide polymorphisms (Areces-Berazain et al., 2020). Accordingly, we concluded that the SSC region could apply for molecular barcoding in Acer, where rpl32-trnL and ycf1 are the most appropriate candidates. The function of the ycf1 gene in the cp genome has not been determined and is generally treated as an open reading frame (Dong et al., 2012). The ycf1 gene, which showed high polymorphism in previous studies, may be designed as the molecular marker for phylogenetic analyses (Dong et al., 2015; He et al., 2017).

3.4 Positive Selection Analysis

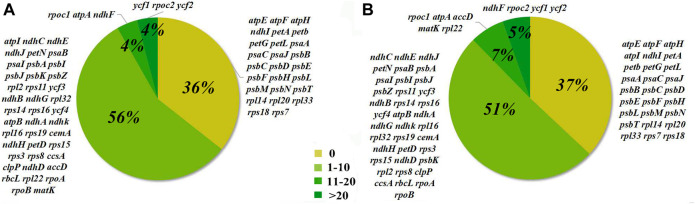

Seventy-three protein-coding gene sites were identified to be positively selected under the CodeML codon substitution models. Two genes (psaI and psbK) were detected to be positively selected with ω > 1 under the one-ratio model (M0), and nine genes (rps8, rpoC2, rps16, ycf1, ndhG, matK, rpl22, petN, and ycf2) with ω between 0.5 and 1.0, indicating relaxation of selective constraint. We also identified cp genes with sites under positive selection in models M2 and M8, which rejected the null models M1 and M7, respectively (Table 3). In model M2, 41 genes had 1–10 sites, three genes had 11–20 sites, and three genes had more than 20 sites under positive selection. In model M8, 37 genes had 1–10 sites, five genes had 11–20 sites, and four genes had more than 20 sites under positive selection (Figure 3). Among them, 20 genes have significantly positively-selected sites based on Bayes empirical Bayes (BEB) posterior probability, including two subunits of the ATP gene (atpA and atpB), three NADH dehydrogenase genes (ndhA, ndhD, and ndhH), one of the cytochrome b/f complex genes (petD), one of Photostsyem I (psaI), one of RubisCO large subunit gene (rbcL), four RNA polymerase genes (ropA, ropB, ropC1, and ropC2), three ribosomal protein genes (rps8, rps11, and rps19), and accD, clpP, ycf1, ycf2, and ycf3.

TABLE 3.

Detection of positive selection sites of chloroplast genes in Acer genus.

| Genes | Model | Parameters | 2ΔL | Sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| accD | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.312 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −3,194.888 | 4.319 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −3,192.729 | 8 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −3,194.917 | 4.405 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −3,192.714 | 13 | ||

| atpA | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.414 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −3,062.544 | 68.257 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −3,028.416 | 12 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −3,062.550 | 68.092 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −3,028.500 | 12 | ||

| atpB | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.195 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −2,767.483 | 19.820 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −2,757.573 | 3 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −2,768.353 | 21.511 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −2,757.597 | 3 | ||

| clpP | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.290 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −1,222.189 | 75.140 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −1,184.619 | 5 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −1,222.474 | 70.978 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −1,186.985 | 6 | ||

| ndhA | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.215 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −2,101.206 | 16.580 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −2092.916 | 3 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −2,101.626 | 17.610 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −2092.821 | 3 | ||

| ndhD | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.238 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −2,926.687 | 24.031 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −2,914.671 | 5 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −2,926.898 | 24.425 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −2,914.686 | 5 | ||

| ndhF | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.398 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −5,574.424 | 97.807 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −5,525.520 | 13 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −5,577.921 | 109.337 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −5,523.252 | 22 | ||

| PetD | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.271 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −942.151 | 11.366 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −936.469 | 4 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −942.381 | 11.793 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −936.484 | 4 | ||

| psaI | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 3.320 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −190.292 | 23.988 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −178.298 | 2 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −192.000 | 27.404 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −178.298 | 2 | ||

| rbcL | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.323 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −2,649.421 | 94.692 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −2,602.075 | 8 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −2,649.889 | 95.034 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −2,602.372 | 8 | ||

| rpoA | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.425 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −1960.904 | 18.516 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −1951.646 | 9 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −1961.168 | 19.006 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −1951.665 | 9 | ||

| rpoB | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.170 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −6,023.244 | 25.005 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −6,010.741 | 9 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −6,023.711 | 25.873 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −6,010.775,053 | 9 | ||

| rpoc1 | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.263 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −4,017.309 | 50.238 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −3,992.190 | 11 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −4,018.563 | 51.186 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −3,992.970 | 11 | ||

| rpoc2 | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.528 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −10233.557 | 465.104 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −10001.005 | 45 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −10233.873 | 461.100 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −10003.323 | 48 | ||

| rps8 | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.524 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −856.327 | 14.975 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −848.840 | 4 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −854.884 | 12.935 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −848.417 | 5 | ||

| rps11 | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.273 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −746.510 | 7.472 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −742.774 | 1 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −746.512 | 7.466 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −742.779 | 1 | ||

| rps19 | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.320 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −603.312 | 16.924 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −594.850 | 3 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −603.357 | 17.004 | ||

| M8 (betaω) | −594.855 | 3 | ||

| ycf1 | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.632 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −14774.834 | 157.711 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −14695.978 | 42 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −14774.915 | 156.596 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −14696.617 | 61 | ||

| ycf2 | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.840 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −10754.288 | 44.430 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −10732.073 | 81 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −10754.623 | 45.095 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −10732.076 | 81 | ||

| ycf3 | M0 (one ratio) | ω = 0.161 | ||

| M1 (neutral) | −899.336 | 16.519 | ||

| M2 (selection) | −891.077 | 1 | ||

| M7 (beta) | −900.724 | 19.279 | ||

| M8 (beta&ω) | −891.084 | 1 |

FIGURE 3.

Percentages of the number of sites selected from 73 coding genes in 48 Acer species. A, analysis results of Model M2. B, analysis results of Model M8.

The positive selection of cp genes has been widely studied in angiosperms and demonstrated at the protein level (Li et al., 2020). In this study, psbK and psbI, the subunits of the cp photosynthetic system (Li et al., 2019), were positively selected in Acer. To our knowledge, the positive selection of psbK and psbI was not common in angiosperms. The high ω implies a unique attribute of Acer to adapt to different light environments. Most of the 20 genes with codons positively selected detetced under the BEB algorithm had one or two positively selected codons, but the ycf1, ycf2, and rpoC2 genes contained more than 40 sites under selection. Although we don’t have enough evidence to make definite inferences, past researches, for example, have indicated that ycf1 is exceptionally divergent across land plants (Dong et al., 2015; Mower et al., 2019) and rpoC2 had the most positive selective sites among the cp genes in Siraitia species (Shi et al., 2019). They indicated that rpoC2 had a higher evolutionary rate in several species. These genes that undergo positive selection might result from adaptation to specific ecological niches.

3.5 Phylogenetic Analysis

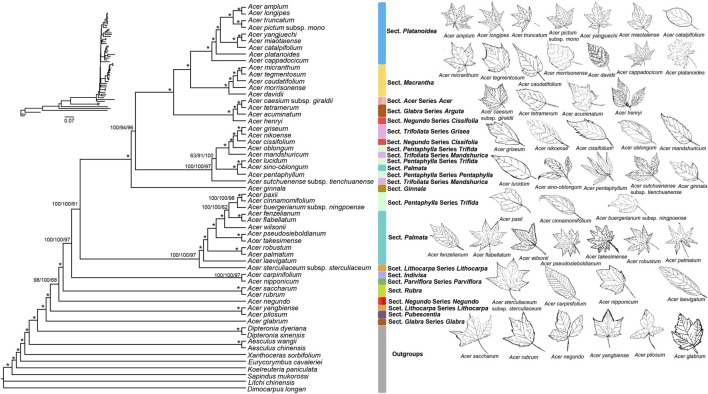

Most nodes of the reconstructed phylogenomic tree had 100% bootstrap support values, indicating a suitable evolutionary placement for Acer species (Figure 4). The results showed that Acer and Dipteronia are monophyly, which is consistent with previous studies (Renner et al., 2008; Gao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Areces-Berazain et al., 2021). Acer pictum subsp. mono is traditionally considered sister to A. truncatum but not to A. yangjuechi (van Gelderen et al., 1994; Xu et al., 2008). However, Yu et al. (2020) proposed A. pictum subsp. mono and A. yangjuechi as sister species according to the “local varieties.” The leaves of A. pictum subsp. mono and A. truncatum has 5-lobed and glabrous abaxially, while A. yangjuechi (synonym for A. miaotaiense in Maples of the World and Flora of China) is 3-lobed, undulate margin and obtuse lobes. In addition, our study showed that each branch within the Platanoidea section had high support, which is consistent with morphological classification (van Gelderen et al., 1994; Xu et al., 2008). Our results strongly support that section Platanoidea and section Macrantha are sister sections (Figure 4), similar to previous studies (Renner et al., 2008; Areces-Berazain et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). The morphological characteristics of the two sections are similar, such as simple leaves with 3- or 5-lobed or unlobed (Xu et al., 2008). However, this result is still inconsistent with some studies, such as Li et al. (2019) and Areces-Berazain et al. (2021), which may be due to different marker selection and single model in the phylogenetic analysis.

FIGURE 4.

Phylogenetic tree of 48 Acer species inferred by Bayesian Inference (BI), Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Maximum Parsimony (MP) methods, based on the whole cp genome sequences. The numbers above the branches are the posterior probabilities of BI and bootstrap values of ML and MP. Asterisks represent nodes with maximal support values in all methods. Each Section was marked in the same colour.

In Maples of the World, section Glabra comprises species from the Glabra and Arguta series (van Gelderen et al., 1994). However, many studies, including the present one, have shown a certain genetic distance between these two series (Li et al., 2019; Areces-Berazain et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2020; Areces-Berazain et al., 2021). Series Glabra is monotypic, containing only A. glabrum and its subspecies. They are mainly shrubs with 5-merous and 8-stamens flowers distributed in North America, unlike Series Arguta, with 4-merous and 4-6 stamens distributed in East Asia (van Gelderen et al., 1994). Therefore, dividing the two series into two sections is more appropriate, as de Jong (2004) proposed. Species of sections Trifoliata and Pentaphylla were mixed (Figure 4), suggesting their sister relationship (Li et al., 2019; Gao et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Areces-Berazain et al., 2021). These two sections have compound leaves, distinguishing them from most other sections in Acer (Xu et al., 2008). The Section Palmata was not monophyletic as it lacked A. sino-oblongum, which is consistent with previous studies (Gao et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020). Although many studies have placed A. sino-oblongum in Section Palmata (van Gelderen et al., 1994; Xu et al., 2008), the taxonomic status of this species must be revisited. Acer yangbiense, a rare and critically endangered species, is herein shown to be genetically distant from the other species in Section Lithocarpa, as in previous studies (Li et al., 2019; Areces-Berazain et al., 2021). This species has pale white to pale gray leaf blade abaxially, entire leaf margin, and slender fruiting pedicels, which are pretty different from other species in the Section Lithocarpa (van Gelderen et al., 1994; Xu et al., 2008). Determining the systematic position of A. yangbiense is of great significance to conserving this rare and endangered species.

4 Conclusion

This study compared 48 whole cp genome sequences of Acer, which exhibited a typical quadripartite structure and genomic content. The comparative study allowed us to identify hotspot loci and several transferable polymorphic SSR applied as DNA barcodes for species identification and phylogenetic inference. Moreover, the complete plastome data allowed us to obtain the highest phylogenetic resolution to date for the 48 Acer species, showing that the cp phylogenomic approach could be employed to tackle the intractable phylogenic problems in Acer. The comparative genomic information constitutes a valuable resource in advancing our understanding of plastid evolution and molecular breeding application for the agro-horticulture in Acer species.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

TY and JG conceived and designed the work. TY, JG, and W-BM collected samples. TY and JG performed the experiments and analyzed the data. TY and JG wrote the manuscript. P-CL and J-QL critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the paper.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the program “The biogeographical feature and competitive hybridization of Maple (Acer L.) in East Asia” of National Natural Science Foundation of China (41901063) and Research Program of Science and Technology at Universities of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (NJZZ19185) to JG, “Reintroduction Technologies and Demonstration of Extremely Rare Wild Plant Population” of National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFC0503106) to J-QL, Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST 109-2621-B-003-003-MY3 and 109-2628-B-003-001) to P-CL.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2021.791628/full#supplementary-material

References

- Ackerly D. D., Donoghue M. J. (1998). Leaf Size, Sapling Allometry, and Corner's Rules: Phylogeny and Correlated Evolution in Maples (Acer). The Am. Naturalist 152, 767–791. 10.1086/286208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiryousefi A., Hyvönen J., Poczai P. (2018). IRscope: an Online Program to Visualize the junction Sites of Chloroplast Genomes. Bioinformatics 34, 3030–3031. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Areces-Berazain F., Hinsinger D. D., Strijk J. S. (2021). Genome-wide Supermatrix Analyses of Maples (Acer, Sapindaceae) Reveal Recurring Inter-continental Migration, Mass Extinction, and Rapid Lineage Divergence. Genomics 113, 681–692. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2021.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Areces-Berazain F., Wang Y., Hinsinger D. D., Strijk J. S. (2020). Plastome Comparative Genomics in Maples Resolves the Infrageneric Backbone Relationships. Peer J. 8, e9483. 10.7717/peerj.9483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi W., Gao Y., Shen J., He C., Liu H., Peng Y., et al. (2016). Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacology of the Genus Acer (maple): a Review. J. Ethnopharmacology 189, 31–60. 10.1016/j.jep.2016.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop D. A., Beier C. M., Pederson N., Lawrence G. B., Stella J. C., Sullivan T. J. (2015). Regional Growth Decline of Sugar maple (Acer Saccharum) and its Potential Causes. Ecosphere 6, art179. 10.1890/ES15-00260.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brozynska M., Furtado A., Henry R. J. (2016). Genomics of Crop Wild Relatives: Expanding the Gene Pool for Crop Improvement. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 1070–1085. 10.1111/pbi.12454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J., Ma P.-F., Li H.-T., Li D.-Z. (2015). Complete Plastid Genome Sequencing of Four Tilia Species (Malvaceae): A Comparative Analysis and Phylogenetic Implications. PLoS ONE 10, e0142705. 10.1371/journal.pone.0142705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H. J., Kim S. T., Suh Y. B., Park C. W. (1996). ITS Sequences of Some Acer Species and Phylogenetic Implication. Korean J. Pl. Taxon 26, 271–291. 10.11110/kjpt.1996.26.4.271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. S., Chung M. G., Park S. (2016). The Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequences of Three Veroniceae Species (Plantaginaceae): Comparative Analysis and Highly Divergent Regions. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 355. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronquist A. (1979). The Evolution and Classication of Flowering Plants. Brittonia 31, 293. 10.2307/2806668 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curci P. L., De Paola D., Danzi D., Vendramin G. G., Sonnante G. (2015). Complete Chloroplast Genome of the Multifunctional Crop Globe Artichoke and Comparison with Other Asteraceae. PLoS ONE 10, e0120589. 10.1371/journal.pone.0120589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M., Thompson R. C., Maher C., Contreras-Galindo R., Kaplan M. H., Markovitz D. M., et al. (2010). NGSQC: Cross-Platform Quality Analysis Pipeline for Deep Sequencing Data. BMC Genomics 11, S7. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-s4-s7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong P. C. (2004). “World maple Diversity,” in International Maple Symposium, Westonbirt Arboretum and Royal Agricultural College in Gloucestershire, England, Gloucestershire: Westonbirt Arboretum. Editors Wiegrefe S. J., Angus H., Otis D., Gregory P., 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- de Santana Lopes A., Gomes Pacheco T., Nimz T., do Nascimento Vieira L., Guerra M. P., Nodari R. O., et al. (2018). The Complete Plastome of Macaw palm [Acrocomia Aculeata (Jacq.) Lodd. Ex Mart.] and Extensive Molecular Analyses of the Evolution of Plastid Genes in Arecaceae. Planta 247, 1011–1030. 10.1007/s00425-018-2841-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W., Liu J., Yu J., Wang L., Zhou S. (2012). Highly Variable Chloroplast Markers for Evaluating Plant Phylogeny at Low Taxonomic Levels and for DNA Barcoding. PLoS ONE 7, e35071. 10.1371/journal.pone.0035071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W., Xu C., Li C., Sun J., Zuo Y., Shi S., et al. (2015). ycf1, the Most Promising Plastid DNA Barcode of Land Plants. Sci. Rep. 5, 8348. 10.1038/srep08348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle J. J. (1987). A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small amounts of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Liao P.-C., Huang B.-H., Yu T., Zhang Y.-Y., Li J.-Q. (2020). Historical Biogeography of Acer L. (Sapindaceae): Genetic Evidence for Out-Of-Asia Hypothesis with Multiple Dispersals to North America and Europe. Sci. Rep. 10, 21178. 10.1038/s41598-020-78145-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Liao P.-C., Meng W.-H., Du F. K., Li J.-Q. (2017). Application of DNA Barcodes for Testing Hypotheses on the Role of Trait Conservatism and Adaptive Plasticity in Acer L. Section Palmata Pax (Sapindaceae). Braz. J. Bot. 40, 993–1005. 10.1007/s40415-017-0404-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., Lethiec F., Duroux P., Gascuel O. (2005). PHYML Online-Aa Web Server for Fast Maximum Likelihood-Based Phylogenetic Inference. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W557–W559. 10.1093/nar/gki352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q., Li H., Qian Z., Lu J., Zheng W. (2021). Comparative Study on the Chloroplast Genomes of Five Larix Species from the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and the Screening of Candidate DNA Markers. J. For. Res. 32, 2219–2226. 10.1007/s11676-020-01279-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn C., Bachmann L., Chevreux B. (2013). Reconstructing Mitochondrial Genomes Directly from Genomic Next-Generation Sequencing Reads-A Baiting and Iterative Mapping Approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e129. 10.1093/nar/gkt371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T. A. (1999). BioEdit: a User-Friendly Biological Sequence Alignment Editor and Analysis Program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl. Acid. S. 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- He L., Qian J., Li X., Sun Z., Xu X., Chen S., et al. (2017). Complete Chloroplast Genome of Medicinal Plant Lonicera japonica: Genome Rearrangement, Intron Gain and Loss, and Implications for Phylogenetic Studies. Molecules 22, 249. 10.3390/molecules22020249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y., Yang J., He Y.-L., He Y., Niu C., Gong L.-L., et al. (2016). Characterization of the Whole Chloroplast Genome Sequence of Acer Davidii Franch (Aceraceae). Conservation Genet. Resour. 8, 141–143. 10.1007/s12686-016-0530-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Kuma K., Toh H., Miyata T. (2005). MAFFT Version 5: Improvement in Accuracy of Multiple Sequence Alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 511–518. 10.1093/nar/gki198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Stukel M., Bussies P., Skinner K., Lemmon A. R., Lemmon E. M., et al. (2019). Maple Phylogeny and Biogeography Inferred from Phylogenomic Data. Jnl Sytematics Evol. 57, 594–606. 10.1111/jse.12535 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Yue J., Shoup S. (2006). Phylogenetics of Acer (Aceroideae, Sapindaceae) Based on Nucleotide Sequences of Two Chloroplast Non-coding Regions. Harv. Pap. Bot. 11, 101–115. 10.3100/1043-4534(2006)11[101:poaasb]2.0.co;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Dong Y., Liu Y., Yu X., Yang M., Huang Y. (2020). Comparative Analyses of Euonymus Chloroplast Genomes: Genetic Structure, Screening for Loci with Suitable Polymorphism, Positive Selection Genes, and Phylogenetic Relationships within Celastrineae. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 2307. 10.3389/fpls.2020.593984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Jia L., Wang Z., Xing R., Chi X., Chen S., et al. (2019). The Complete Chloroplast Genome of Saxifraga Sinomontana (Saxifragaceae) and Comparative Analysis with Other Saxifragaceae Species. Braz. J. Bot. 42, 601–611. 10.1007/s40415-019-00561-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Sylvester S. P., Li M., Zhang C., Li X., Duan Y., et al. (2019). The Complete Plastid Genome of Magnolia Zenii and Genetic Comparison to Magnoliaceae Species. Molecules 24, 261. 10.3390/molecules24020261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.-H., Xie Y.-S., Zhou T., Jia Y., He Y.-L., Yang J. (2017). The Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence of Acer Morrisonense (Aceraceae). Mitochondrial DNA A 28, 309–310. 10.3109/19401736.2015.1118091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Librado P., Rozas J. (2009). DnaSP V5: a Software for Comprehensive Analysis of DNA Polymorphism Data. Bioinformatics 25, 1451–1452. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mower J. P., Ma P. F., Grewe F., Taylor A., Michael T. P., Vanburen R., et al. (2019). Lycophyte Plastid Genomics: Extreme Variation in GC , Gene and Intron Content and Multiple Inversions between a Direct and Inverted Orientation of the rRNA Repeat. New Phytol. 222, 1061–1075. 10.1111/nph.15650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfosser M. F., Guzywróbelska J., Sun B., Stuessy T. F., Sugawara T., Fujii N. (2002). The Origin of Species of Acer (Sapindaceae) Endemic to Ullung Island, Korea. Syst. Bot. 27, 351–367. 10.1043/0363-6445-27.2.351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D., Buckley T. R. (2004). Model Selection and Model Averaging in Phylogenetics: Advantages of Akaike Information Criterion and Bayesian Approaches over Likelihood Ratio Tests. Syst. Biol. 53, 793–808. 10.1080/10635150490522304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J., Song J., Gao H., Zhu Y., Xu J., Pang X., et al. (2013). The Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence of the Medicinal Plant Salvia Miltiorrhiza . PLoS ONE 8, e57607. 10.1371/journal.pone.0057607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner S. S., Grimm G. W., Schneeweiss G. M., Stuessy T. F., Ricklefs R. E. (2008). Rooting and Dating Maples (Acer) with an Uncorrelated-Rates Molecular Clock: Implications for north American/Asian Disjunctions. Syst. Biol. 57, 795–808. 10.1080/10635150802422282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Teslenko M., van der Mark P., Ayres D. L., Darling A., Höhna S., et al. (2012). MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference and Model Choice across a Large Model Space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542. 10.1093/sysbio/sys029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosado A., Vera-Vélez R., Cota-Sánchez J. H. (2018). Floral Morphology and Reproductive Biology in Selected maple (Acer L.) Species (Sapindaceae). Braz. J. Bot. 41, 1–14. 10.1007/s40415-018-0452-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhsam M., Rai H. S., Mathews S., Ross T. G., Graham S. W., Raubeson L. A., et al. (2015). Does Complete Plastid Genome Sequencing Improve Species Discrimination and Phylogenetic Resolution inAraucaria? Mol. Ecol. Resour. 15, 1067–1078. 10.1111/1755-0998.12375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamour F. S., Jr (1982). Cambial Peroxidase Isoenzymes in Relation to Systematics of Acer . Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 109, 152–161. 10.2307/2996255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shearman J. R., Sonthirod C., Naktang C., Sangsrakru D., Yoocha T., Chatbanyong R., et al. (2020). Assembly of the Durian Chloroplast Genome Using Long PacBio Reads. Sci. Rep. 10, 15980. 10.1038/s41598-020-73549-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Yang M., Mo C., Xie W., Liu C., Wu B., et al. (2019). Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Two Siraitia Merrill Species: Comparative Analysis, Positive Selection and Novel Molecular Marker Development. PLoS ONE 14, e0226865. 10.1371/journal.pone.0226865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonah H., Deshmukh R. K., Singh V. P., Gupta D. K., Singh N. K., Sharma T. R. (2011). Genomic Resources in Horticultural Crops: Status, Utility and Challenges. Biotechnol. Adv. 29, 199–209. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford D. L. (2003). PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony. [Google Scholar]

- Tangphatsornruang S., Sangsrakru D., Chanprasert J., Uthaipaisanwong P., Yoocha T., Jomchai N., et al. (2009). The Chloroplast Genome Sequence of Mungbean (Vigna Radiata) Determined by High-Throughput Pyrosequencing: Structural Organization and Phylogenetic Relationships. DNA Res. 17, 11–22. 10.1093/dnares/dsp025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timme R. E., Kuehl J. V., Boore J. L., Jansen R. K. (2007). A Comparative Analysis of the Lactuca and Helianthus (Asteraceae) Plastid Genomes: Identification of Divergent Regions and Categorization of Shared Repeats. Am. J. Bot. 94, 302–312. 10.3732/ajb.94.3.302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gelderen D. M., De Jong P. C., Oterdoom H. J. (1994). Maples of the World. Portland: Timber Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wambugu P. W., Brozynska M., Furtado A., Waters D. L., Henry R. J. (2015). Relationships of Wild and Domesticated Rices (Oryza AA Genome Species) Based upon Whole Chloroplast Genome Sequences. Sci. Rep. 5, 13957. 10.1038/srep13957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Chen S., Zhang X. (2020). Complete Plastomes of 17 Species of Maples (Sapindaceae: Acer): Comparative Analyses and Phylogenomic Implications. Plant Syst. Evol. 306, 61. 10.1007/s00606-020-01690-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wyman S. K., Jansen R. K., Boore J. L. (2004). Automatic Annotation of Organellar Genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics 20, 3252–3255. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J. S., Ding J., Li Y. (2015). Genome-editing Technologies and Their Potential Application in Horticultural Crop Breeding. Hortic. Res. 2, 15019. 10.1038/hortres.2015.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T. Z., Chen Y. S., de Jong P. C., Oterdoom H. J. (2008). “C. C. Aceraceae,” in Flora of China. Editors Wu Z. Y., Raven P. H., Hong D. Y., 11, 515–553. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. B., Li D. Z., Li H. T. (2015). Highly Effective Sequencing Whole Chloroplast Genomes of Angiosperms by Nine Novel Universal Primer Pairs. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 14, 1024–1031. 10.1111/1755-0998.12251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. (2007). PAML 4: Phylogenetic Analysis by Maximum Likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591. 10.1093/molbev/msm088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi X., Gao L., Wang B., Su Y.-J., Wang T. (2013). The Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence of Cephalotaxus Oliveri (Cephalotaxaceae): Evolutionary Comparison of Cephalotaxus Chloroplast DNAs and Insights into the Loss of Inverted Repeat Copies in Gymnosperms. Genome Biol. Evol. 5, 688–698. 10.1093/gbe/evt042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T., Gao J., Huang B.-H., Dayananda B., Ma W.-B., Zhang Y.-Y., et al. (2020). Comparative Plastome Analyses and Phylogenetic Applications of the Acer Section Platanoidea . forests 11, 462. 10.3390/F11040462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeb U., Dong W. L., Zhang T. T., Wang R. N., Shahzad K., Ma X. F., et al. (2019). Comparative Plastid Genomics of Pinus Species: Insights into Sequence Variations and Phylogenetic Relationships. J. Syst. Evol. 58, 118–132. 10.1111/jse.12492 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Li B., Chen H., Wang Y. (2016). Characterization of the Complete Chloroplast Genome of Acer Miaotaiense (Sapindales: Aceraceae), a Rare and Vulnerable Tree Species Endemic to China. Conservation Genet. Resour. 8, 383–385. 10.1007/s12686-016-0564-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.