Abstract

Fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) continues to evolve and make an impact in the pharmaceutical sciences. We summarize successful fragment-to-lead studies that were published in 2020. Having systematically analyzed annual scientific outputs since 2015, we discuss trends and best practices in terms of fragment libraries, target proteins, screening technologies, hit-optimization strategies, and the properties of hit fragments and the leads resulting from them. As well as the tabulated Fragment-to-Lead (F2L) programs, our 2020 literature review identifies several trends and innovations that promise to further increase the success of FBDD. These include developing structurally novel screening fragments, improving fragment-screening technologies, using new computer-aided design and virtual screening approaches, and combining FBDD with other innovative drug-discovery technologies.

Introduction

Fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) has become a powerful approach for interrogating drug targets and discovering new biologically active compounds.1 Its success relies on screening compounds of low molecular weight and low complexity (i.e., “fragments”) during the hit-finding phase, employing sensitive and robust detection methods. By using rational approaches such as structure-based drug design, the hit fragments are efficiently grown, linked or merged into larger lead compounds that can be progressed into preclinical and clinical research. At present, six fragment-derived drugs have been approved for clinical use, with Lumakras (sotorasib) being approved in May 2021 and Scemblix (asciminib) being approved in October 2021. Many more candidates that have been developed using FBDD are now undergoing clinical studies.1,2

Due to the reduced molecular complexity of the initial chemical matter, FBDD is an ideal breeding ground for the continuous development of new technologies and their application in medicinal chemistry and chemical biology. All this makes it valuable to monitor the FBDD literature. Starting with FBDD literature published in 2015, we have been providing the community with a tabulated overview of successful Fragment-to-Lead (F2L) campaigns, and with commentary on trends extracted from the scientific publications that were published in each calendar year.3−7 Here we provide a similar review of FBDD articles published in 2020.

Articles of interest were identified as described in an earlier Perspective.5 In short, four different strategies were followed:

-

(i)

A literature search using SciFinder8 and a variety of FBDD-related keywords;

- (ii)

-

(iii)

Careful scrutiny of the 2020 issues of Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters, Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, and Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, which in an earlier analysis were found to have published many of the relevant F2L studies;5

-

(iv)

Publications that were discussed on the well-known Practical Fragments blog.2

The literature collected from these sources was evaluated and discussed. As well as identifying remarkable FBDD developments and trends, we used the criteria that have been applied since the first installment in 2015 to select publications that qualify for inclusion in the table of fragment-to-lead case studies. In brief:

A fragment hit has a molecular weight (MW) < 300 Da.

The fragment hit is identified using a screening technology (a biophysical, biochemical, or computational approach), adopted from the literature or obtained by the deconstruction of a known ligand.

The potency or affinity of the lead is equal to or better than 2 μM.

The improvement in potency or affinity from fragment to lead is at least 100-fold.

The publication date (as defined by the primary citation) for the article is in the calendar year 2020.

It was noted in an earlier F2L perspective5 that more recent literature searches require careful analysis, as an increasing number of relevant FBDD publications do not explicitly use the term fragment in the title or abstract. This was considered as a sign that FBDD was maturing. Conversely, we have noted for some time that a growing number of publications have adopted the term fragment or fragment-based without meeting our definition of FBDD. These studies use the term “fragment” as a synonym for “substructure”, for example, when combining features from different series of drug-like molecules—an approach we appreciate, but refer to as “knowledge-based design”. Authors, referees, and editors are encouraged to preserve the designation “fragment-based” for those approaches that actually determine (and ideally measure) the binding of the small fragments as unique molecular entities.

Results

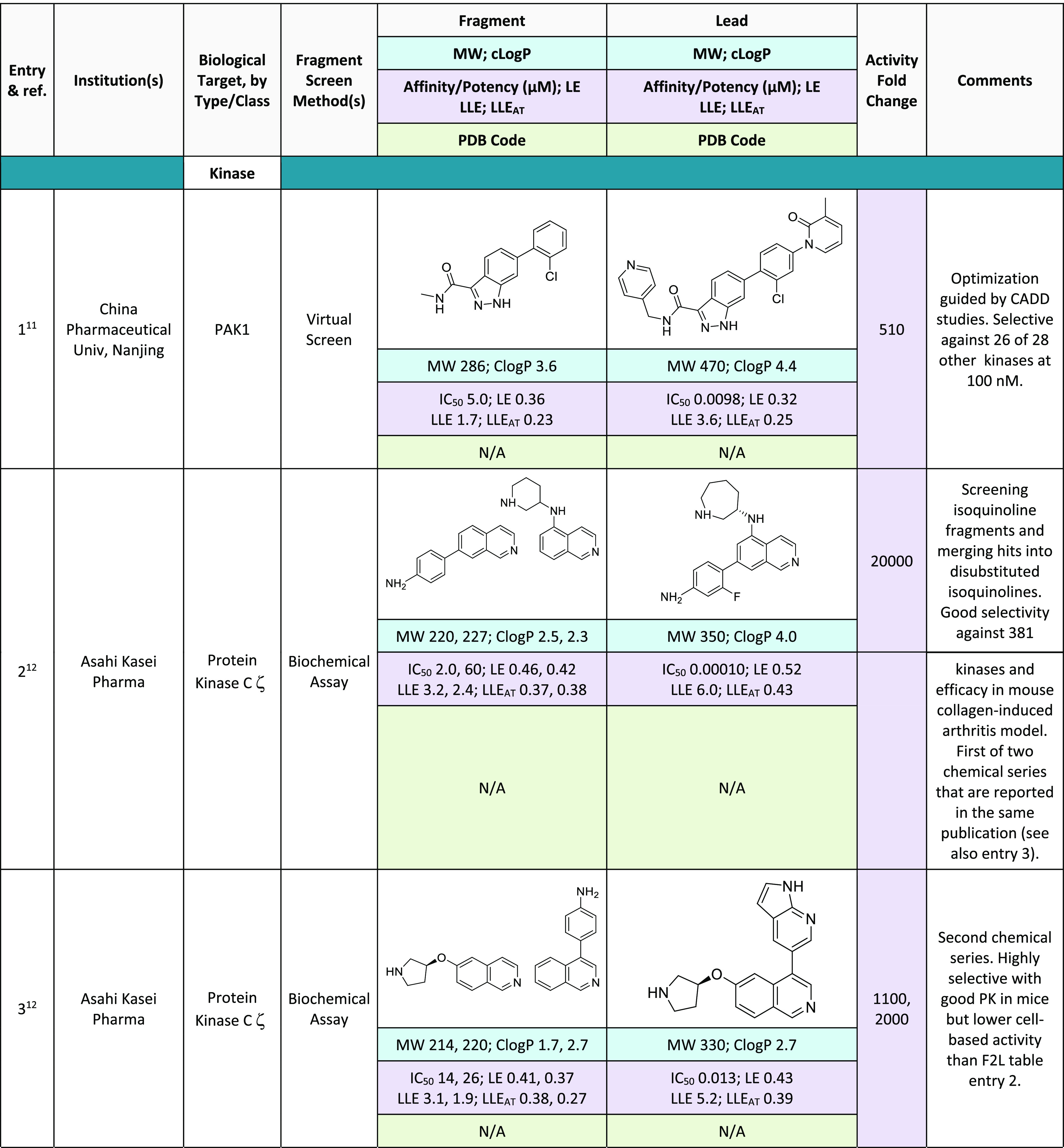

Careful triage of the 2020 literature resulted in the identification of 21 F2L studies that qualify for inclusion in Table 1. As always, the strict criteria for table inclusion resulted in several notable studies that have not been tabulated. In our discussion below, we outline some of these studies, which represent new developments, trends, and excitement in the field.

Table 1. Fragment-to-Lead Publications from 202011−32.

ClogP values were determined using Daylight version 4.9.33

Ligand efficiency34 (LE) is expressed in units of kcal·mol–1 per non-hydrogen atom and is calculated with R = 0.001 987 kcal·mol–1·K–1 and T = 298 K. Standard state is assumed to be 1 M. Ligand-lipophilicity efficiency35 (LLE, also called LipE36) is dimensionless; and Astex ligand-lipophilicity efficiency37 (LLEAT) has the same units as LE.

N/A: not applicable; X-ray structure not reported or used.

X-ray structure of a closely related compound.

X-ray structure of a closely related compound in a closely related protein.

NA: LE, LLE, and LLEAT are not applicable to irreversible inhibitors.

Analysis of the F2L entries in Table 1 showed that 28% of the entries are kinase inhibitors, a higher percentage than last year but close to the average for the last 6 years (Figure 1). It is remarkable that the majority of the 2020 kinase F2L programs did not rely on crystallography (Table 1, entries 1, 2, 3, and 6). Apparently, the structural understanding and molecular modeling capabilities suffice to guide fragment optimization. In line with this, we note that all 2020 kinase F2L entries target the important and highly conserved hinge region.38,39 As the work on Protein Kinase C ζ (entries 2 and 3) shows, fragment growing and fragment merging (i.e., combining the decoration of different hit fragments that have the same core) have proved to be very efficient. As seen in previous years, most hit fragments are relatively “flat” (or “2D-shaped”). Takeda’s work on ALK kinase (entry 4) and Leo Pharma’s work on JAK1 (entry 5) are good examples of F2L programs that identify 2D-shaped hit fragments and incorporate 3D-shape including chirality during the lead-optimization programs.

Figure 1.

Protein classes targeted by tabulated F2L case studies.

Figure 1 also shows that proteases (5% of the table entries) and other enzymes (38%) remain prominent targets in F2L studies. The work on Mycobacterium tuberculosis InhA (entry 8) involves the replacement of a carboxylic acid of the fragment hit by a sulfonamide. Table 1 entries 9 and 10 both result from a publication describing a program on the bacterial zinc metalloenzyme LpxC. In this work, two different hit fragments were optimized into unique lead compounds using structure-based design. Not captured in the F2L table is a 2020 publication that describes FBDD approaches to the development of enzyme activators, in this case targeting the fungal glycoside hydrolase TrBgl2 as an enzyme with industrial applications.40 In the Perspective covering the 2019 literature,7 we also discussed an example of an enzyme activator. Neither example meets the 100-fold improvement criterion specified for inclusion in the F2L tables, but nevertheless they represent interesting applications of FBDD.

Protein–protein interactions (PPI) also remain prominent. This year had three F2L table entries for bromodomains (14%), two of which reported crystal structures. The work by the Chinese Academy of Sciences on BRD4 illustrates an efficient fragment-merging approach in which a novel hit fragment is rapidly optimized by using substructure features of a clinical candidate that had been developed by AbbVie (who themselves used an FBDD approach to generate that clinical candidate, previously reported as entry 22 in the 2017 F2L table5). Table entry 19 is for another class of PPIs, in this case describing the development of inhibitors for the interaction of the WDR5 scaffolding protein with the intrinsically disordered transcription factor MYC, a promising cancer drug target. Here, too, fragment merging has proved to be efficient. A 2020 study that just missed the criteria for table inclusion focused on finding PPI inhibitors for p47phox-p22phox (a complex that is key to activating NADP oxidase isoform 2), work that led to a compound with a Ki of 20 μM.41 A more technology-focused study aimed to improve NMR fragment-screening protocols for finding PPI inhibitors after the introduction of point mutations to weaken the PPI, thereby making it easier for small screening fragments to compete.42 Other studies that did not meet the criteria for F2L table inclusion revealed a continued and growing interest in PPI stabilizers, including the continuing prolific work by Ottmann and co-workers on stabilizing interactions of the adaptor protein 14-3-3. These recent studies included work showing that small molecule stabilizers can differentiate between different PPI interfaces.43 Other publications by the same group describe the use of fluorescence anisotropy as a readout for monitoring disulfide tethering44 as an alternative to the previously reported MS-based screening;45 and complementary efforts to develop molecular glues using fragments that make a covalent imine-bond with lysines of the target protein.46 These early results and the tools developed hold promise for developing molecules that stabilize the interactions of 14-3-3 with various proteins. A spinout company has been established that aims to further utilize these tools in drug development.47

The 2020 table also contains a GPCR example (entry 20), a study that delivered a negative allosteric modulator of GPR7. Careful fragment library screening, hit exploration, and fragment growing resulted in a lead without using structural information or biophysical screening, i.e., types of data that remain difficult to obtain for GPCR targets.31

There are also several reports of FBDD targeting RNA.48−50 Although these programs have not yet produced leads that fulfill all F2L criteria for table inclusion, there is clearly growing interest in identifying fragments that bind to RNA.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has underlined the importance of scientific research to human health as evidenced by rapid development of COVID vaccines. The FBDD community has also responded to this situation, as illustrated by the very swift interrogation of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease MPro, although this work has not yet translated into leads meeting our tabulation criteria for the year under review. Only a few weeks after the COVID-19 pandemic struck, MPro was identified as a promising drug target and interrogated with covalent and noncovalent fragments using a combination of mass spectrometry and high throughput X-ray analysis.51 Importantly, as early as March 2020, nearly 100 structures of fragment-protein complexes had been made public, providing valuable starting points for inhibitors (Figure 2), thereby allowing the global research community to participate in drug discovery.42,52 These laudable efforts will hopefully soon result in potent leads and a string of F2L publications that originate from academia, industry and open-science initiatives53 around the world.

Figure 2.

Superposition of the structures of the XChem fragment screening hits shows the binding of covalent and noncovalent fragments to the SAR-CoV-2 main protease. Structures were downloaded from the Diamond web site (https://www.diamond.ac.uk/covid-19/for-scientists/Main-protease-structure-and-XChem/Downloads.html) where they were they were posted without delay to enable the international research community. Most fragments bind to the active site of the enzyme. The figure was generated using MOE (version 2020.09) software and is similar to an illustration used in the primary literature.51

A significant number of the 2020 FBDD publications describe fragment hit-finding efforts for microbial targets. Table 1 entries 8–10 and 12 focus on specific bacterial targets. All of these studies target (nonprotease) enzymes. Table 1 entry 8 (targeting the FAS II enzyme InhA that is involved in the reduction of long-chain fatty acids) reports that the high activity of the lead compound does not translate into antibiotic activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis.18Table 1 entries 9 and 10 target the zinc metalloenzyme UDP-3-O-acyl-N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase (LpxC).19 While both series resulted in very potent leads, only the latter resulted in in vivo efficacy. The work on DNA gyrase also resulted in antibacterial activities, but significant differences were found within the developed series of inhibitors, with efflux mechanisms being the most likely cause for these differences, illustrating some of the challenges in developing new antibiotics.22 While a string of other 2020 publications describe antimicrobial FBLD hit-finding and exploration studies, they do not meet all the criteria for F2L table inclusion. Examples include studies focused on bacterial targets such as metallo-β-lactamase(MBL)NDM-1,54 dihydrofolate reductase from M. tuberculosis (MtDHFR),55M. tuberculosis MabA (FabG1)56 and tRNA-modifying enzyme TGT, where a hit fragment opens a transient subpocket that can be exploited by a new series of ligands;57 tRNA modification enzyme TrmD,58 fungal targets such as glucosamine 6-phosphate N-acetyltransferase (Gna1), which is a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of an essential fungal cell-wall component;59 parasite targets such as the cysteine protease enzyme cruzain;60 allosteric binders for farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase of Trypanosoma brucei;61 bromodomain-containing factor 3 of Trypanosoma cruzi;62 membrane-bound pyrophosphatases (mPPases); virus targets (e.g., viral DNA-binding proteins Epstein–Barr nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) and latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA);63 and, as indicated above, several efforts to probe and target SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Another interesting study developed PqsR-targeting quorum-sensing inhibitors (a study that uses biophysical screening and enthalpic efficiency evaluations, and introduces relatively flexible linkers).64

Figure 3 presents the screening technologies that were used to identify the hit fragments in the F2L table entries. In 2020, we saw again that biochemical assays were the most frequently used method for fragment-hit identification (39%), followed by NMR screening (ligand-observed 17% and protein-observed 9%). The other well-established screening technologies are also represented in the 2020 F2L table, including thermal shift assays (9%), which were used in the successful M. tuberculosis InhA program (entry 8) and BRD4 program (entry 18). For the first time, the F2L table contains a publication (entry 12) that describes the use of isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) as the primary fragment-screening method for DNA gyrase. As high protein consumption can limit screening capacity, ITC has been used mainly as a secondary, orthogonal screen to validate fragment hits. In this case, the use of ITC was enabled by combining a focused screening library with an established protein target. The use of ITC enabled the authors to select a fragment whose binding to the target protein was enthalpy-driven and that was successfully optimized into a lead compound.

Figure 3.

Fragment-screening technologies used in successful F2L case studies.

Although not reflected in the table, a prominent feature of the collected 2020 literature involves the further development of fragment-screening technologies. Several studies describe new and improved NMR screening protocols, particularly those to increase throughput by automated analyses of FBDD data, e.g., using freely available software tools such as CcpNmr;65 or a new automated tool called CSP Analyzer, which uses machine-learning-driven analysis to assess multiple 2D HSQC spectra.6619F NMR assays also continue to be improved, for example through the use of novel broadband 19F NMR, which allows faster fragment screening and thus increases the throughput.67 Another study combines protein- and ligand-observed experiments in a multiplexed screen that contains mixtures of fragments and bromodomain proteins.68 Clearly, the NMR community remains very active in providing increasingly efficient FBDD screening technologies.

The year 2020 also brought several reports of fragment screening using techniques that have not yet made it into our F2L tables. Among others, two studies reported promising fragment screening using Weak Affinity Chromatography (WAC) including for a GPCR target.69,70 It will be interesting to see if these exploratory studies will result in lead compounds.

For X-ray crystallography, too, fragment-screening throughput continues to grow, as discussed in the context of SARS-CoV-2 above. In the form of FragMAX,71 the XChem and Frag2Xtal platforms now have a Swedish equivalent. Several reports also explore the use of crude reaction mixtures in high-throughput X-ray crystallography.72,73 These efforts aim to explore fragment hits more rapidly. As well as X-ray crystallography, the 2020 literature also describes exciting progress in applying cryo-EM to FBDD,74,75 an emerging technology that may open an expanded range of targets to structurally enabled drug design.

Considerable FBDD developments have also continued in computer-aided drug design (CADD) and virtual screening (VS). Among others, there is a continuous effort to evaluate and improve docking algorithms for the virtual screening of fragments, as their small size and low complexity represent a real challenge, particularly for scoring. The open source software SEED shows promising results and was successfully used in fragment-library enrichment for a variety of targets.76 Another method for improving the ranking of docked fragments (in this case using the rDock algorithm) is to evaluate the docking poses generated in silico using a short dynamic undocking experiment (a method dubbed DUck), essentially probing the robustness of the hydrogen bonds that are involved in fragment-protein interactions.77

Several publications describe benchmarking studies for the virtual screening of fragment libraries. A useful data set (LEADS-FRAG) has been released that allows proper comparison of various docking algorithms and scoring functions.78 In our analysis of the 2015–2020 F2L table entries that used virtual screening to identify the hit fragments, we found that the docking algorithm GLIDE was the most used (Figure 4). Unfortunately, GLIDE was not part of the benchmarking study referred to above,78 and its VS performance was therefore not compared to other algorithms. While there may be a bias in that institutes with the resources to complete F2L studies can also access the molecular-modeling tools provided by Schrödinger (including GLIDE), we note that this particular software has successfully delivered a F2L table entry every year since 2015.

Figure 4.

Docking algorithms used for virtual fragment screens in 14 F2L studies meeting tabulation criteria from the years 2015–2020 inclusive.

KinFragLib79 uses the structural kinome database KLIFS80 and a computational fragmentation method to split the cocrystallized ligands into fragments. The resulting library consists of over 7000 fragments that are organized by subpocket occupation. The data set is made available and can be used to explore detailed binding characteristics and to generate novel inhibitors. Other FBDD computational methods that have been developed help to identify binding hot spots,81 again with useful benchmarking sets being made available for testing and comparing computational methods that identify binding hot spots (with emphasis on FBDD). The potential of this approach was demonstrated by a group who used in silico hot-spot identification to identify an unexplored ligandable binding pocket outside the acetyl-lysine binding site of a BRD4 bromodomain, prompting researchers to probe the site in question with covalent binders (vide infra).82

New computational methods have been developed for fragment-linking approaches, combining 3D structural information with machine-learning techniques to design appropriate linkers.83 CADD tools like this may help fragment-linking strategies to achieve their full potential: so-far, as a recent review article describes,84 this F2L strategy has had mixed success. Other computational methods guide fragment growing, for example leading to dual-activity epoxide hydrolase and LTA4 hydrolase inhibitors (table entry 15), an approach that also involved machine learning using ligand-derived and structure-derived fingerprints to distinguish actives from inactives. Other in silico growing approaches that are described in the 2020 literature but did not meet the F2L criteria include a procedure called FragPELE, which uses a Monte Carlo stochastic approach that allows induced fit and the opening of cryptic pockets of the protein target.85 The continuous development of new CADD & VS protocols confirms once again the prominence of the computational chemistry community in FBDD.9

When monitoring the molecular properties of fragment–lead pairs, similar trends as discussed in the previous Perspective can be identified.7 For the interested reader, updated graphs that compare ClogP, LE, LLE, and deviation from planarity of hits and leads are provided in the Supporting Information. For a detailed discussion of the different graphs, see the 2019 F2L perspective.7 A noteworthy observation for the 2020 data set is that multiple table entries obtained 100-fold activity improvement by carefully modifying and optimizing the fragment scaffold (e.g., table entries 13, 14, 20). This is reflected in Figure 5 that suggests that the MW differences between the hits and corresponding leads of the 2020 F2L studies are smaller than for the complete 2015–2020 data set.

Figure 5.

Differences in molecular weight of fragment-lead pairs for all examples from the 2015–2020 data set (left panel) and for the 2020 table entries (right panel).

The complete fragment hit set from all F2L entries (2015–2020) was analyzed using the Scaffold Classification Approach.86 In this analysis, a scaffold is defined by the bonds that are part of a ring or that connect different rings (i.e., the acyclic side chains are pruned from the scaffold). Complexity is defined by the size and shape of the scaffold, and is increased by the number of rings, double bonds and heteroatoms. For example, a phenyl ring is a less complex scaffold than a pyridyl ring (see Figure 6). Cyclicity is defined as the ratio of the number of atoms that are part of the scaffold to the number of atoms of the complete fragment. For cyclicity = 1, there are no side chains; there are 17 hit fragments with cyclicity = 1, including the most complex scaffold (the orange diamond symbol in the top right corner of the plot, representing the mGluR5 hit described as table entry 27 of the 2015 Perspective3). Cyclicity is lowered by more and larger side chains (see structures in the column of diamond symbols with different hits containing the phenyl scaffold on the left side of Figure 6). The analysis shows that the fragment hit set is diverse in terms of complexity and cyclicity but a few prominent scaffolds can be identified. Fifteen of all 152 F2L hits contain a phenyl scaffold, and 8 hits contain a six-membered benzene ring fused to a five-membered ring that contains 2 nitrogen atoms (see the benzimidazole compounds in Figure 6). Strikingly, all the hit fragments contain at least one ring and one sp2-hybridized carbon atom. The complete data set is made available as part of a study that analyses the most common interactions that hit fragments make and to identify the nominal synthetic growth vectors.87

Figure 6.

Diversity analysis of the 2015–2020 F2L hit fragments using the Scaffold Classification Approach.86 Complexity and cyclicity were calculated using the sca.svl script and the modeling program Molecular Operating Environment 2018.01 (MOE) from Chemical Computing Group (Montreal, Canada) and the scatter chart was generated using Microsoft Excel (2019). Blue diamond symbols represent individual fragments, the structure of the orange diamond symbols are shown (carbon atoms in green, nitrogen atoms in blue, oxygen atoms in red, hydrogen atoms in gray).

The theme of “3D fragment libraries” is also prominent,102 following the realization that unexplored scaffolds represent a considerable opportunity.88 Especially when developing new chemistries, it makes sense to screen the new scaffolds as fragments as this optimizes the chance of finding hits. Publications from 2020 include DOS-derived and shape-diverse fragment libraries that allow rapid derivatization of hits in different directions;89 the design and synthesis of shape-diverse 3D fragments;90 the synthesis (and some screening) of a library of larger (seven-membered ring) aliphatic heterocycles with 1,4-thiazepanones and 1,4-thiazepanes as 3D-cores;91 a fluorinated Fsp3 rich fragment library for 19F NMR fragment screening;92 and a fragment library assembled from natural products that contains a high fraction of sp3 carbons (one of the metrics used as a proxy for 3D shape).93 Another study focuses on improving the synthetic accessibility of 3D fragments by decorating sp3-carbon atoms in order to grow from specific exit vectors.94 An unusual approach to incorporating 3D shape is to develop metallo-fragments.95 It will be interesting to see how often this type of fragment makes it into our F2L tables in the future; our 2019 Perspective included a table entry in which a rhodium conjugate was incorporated during lead development.96

In 2020, as in previous years, there were also examples in which FBDD was blended with established or emerging orthogonal technologies. Table 1 entry 16 shows work on BRD4 that merged a fragment hit with a scaffold that was identified using a DNA-encoded library. Other work on BRD4 (table entry 17) identified a small fragment-like hit in a HTS screen that was successfully grown into a lead-like compound using FBDD. Examples like these illustrate that combining different technologies enables a plethora of drug discovery opportunities.

Another continuing theme is the identification of novel binding sites, such as that for tRNA-modifying enzyme TGT,57 where one fragment opens up a transient subpocket that can be exploited by newly designed ligands. Other studies that did not meet the lead criteria explore allosteric pockets in enzymes, e.g., for farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase of the parasite T. brucei.61

The theme of covalent FBDD continues to grow. Principles for the design of electrophilic fragment libraries were reviewed by Keserű et al.,97 and a fragment hit that bound covalently to its target has been successfully used in the F2L program of Lp-PLA2 inhibitors (table entry 11). Also, as previously mentioned, a combined mass spectrometry and X-ray approach was used to target the SARS-CoV-2 main protease with electrophilic (and noncovalent) fragments.51 Covalent-fragment screening was also used to explore a ligandable binding pocket outside the acetyl-lysine binding site of BRD4 bromodomain.82 The use of cysteine-reactive fragments to target a computationally identified hotspot allowed the exploration of a new binding site next to the classic bromodomain binding site.82 Covalent binders were long avoided in the pharmaceutical sciences, but this reluctance has now eased. Some studies have even identified noncovalent fragments and then introduced reactive electrophilic moieties to enable a covalent link with the target. The work on cathepsin S inhibitors (F2L table entry 7) is an example of this approach in which a noncovalent fragment hit was identified using NMR screening and a nitrile warhead was introduced to improve potency.16 A similar 2020 example of adding a warhead during hit optimization is the development of NSD1 tool compounds, although in this latter case the potency change did not meet the criteria for table inclusion.98 Covalent binding is also used to probe proteins with photoreactive fragments that cross-link with protein targets (PhotoAffinity Bits or PhABits).99

Finally, two publications from 2020 described FBLD-derived clinical candidates. Pfizer disclosed their ketohexokinase inhibitor PF-06835919,100 which entered phase 2 studies for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The fragment-to-lead effort was entry 5 in our Perspective for 2017.5 And AbbVie described optimizing their pan-BET inhibitor ABBV-075 to the BD2-selective compound ABBV-744;101 the initial H2L efforts that led to ABBV-075 was entry 22 in our Perspective for 2017.5

Conclusions

FBDD continues to play a major role in drug discovery, as demonstrated by the progress reported in this Perspective. The impact is also apparent when considering the fact that FBDD has resulted in a fifth (sotorasib) and sixth (asciminib) approved drug,2 an increasing number of compounds in clinical trials,2 and the impressive impact of interrogating COVID-19 targets.

Acknowledgments

This Perspective is dedicated to the memory of the late Prof. Chris Abell of Cambridge University. Chris was one of the pioneers of FBDD, cofounder of Astex Pharmaceuticals, and a good friend and mentor to generations of FBDD enthusiasts. The authors thank Paul N. Mortenson from Astex Pharmaceuticals for general discussions and help with the cheminformatics analysis.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DFP

deviation from planarity

- FBDD

fragment-based drug discovery

- LE

ligand efficiency

- LLE

ligand lipophilicity efficiency

- LLEAT

Astex ligand lipophilicity efficiency

- MW

molecular weight

- PPI

protein–protein interaction

- CADD

computer-aided drug design

- VS

virtual screening

Biographies

Iwan J. P. de Esch is Professor at the Medicinal Chemistry Division of Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (“VU Amsterdam”). After obtaining a Ph.D. in Medicinal Chemistry at VU Amsterdam, he became Research Associate at the Drug Design Group of the University of Cambridge. The group spun out as De Novo Pharmaceuticals in 1999. Prof. de Esch returned to Amsterdam in 2003 and established a FBDD research line. He is coordinator of the FBDD-focused European training network FRAGNET. He is also cofounder of De Novo Pharmaceuticals Ltd. (1999), IOTA Pharmaceuticals Ltd. (2007), and Griffin Discoveries BV (2009).

Daniel A. Erlanson is VP of Innovation and Discovery at Frontier Medicines. Before that, he cofounded Carmot Therapeutics, whose Chemotype Evolution technology he codeveloped. Dr. Erlanson received his BA in Chemistry at Carleton College and his PhD in Chemistry at Harvard University in the laboratory of Gregory L. Verdine. He was an NIH postdoctoral fellow with James A. Wells at Genentech. From there he joined Sunesis Pharmaceuticals at its inception, and went on to develop fragment-based technologies and to lead medicinal chemistry programs. As well as coediting two books on fragment-based drug discovery, Dr. Erlanson is editor of Practical Fragments (https://practicalfragments.blogspot.com/).

Wolfgang Jahnke is a Director for Structural Biology and Biophysics at the Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research in Basel, Switzerland. He has helped to shape NMR spectroscopy for applications in fragment-based drug discovery. As well as coediting two books on FBDD, he has successfully led several interdisciplinary project teams and is coinventor and coauthor of more than 80 patents and scientific publications. Dr. Jahnke earned his Ph.D. in Chemistry at the Technical University of Munich and did a postdoc with Peter Wright at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, CA.

Christopher N. Johnson obtained an M.A. degree at the University of Cambridge and a Ph.D. at the University of Bristol, U.K. In 2008, after several years working as a medicinal chemist at GSK and legacy companies, he moved to Astex, where he has worked on fragment-based approaches applied to multiple target classes including PPI antagonists, with a particular focus on the oncology disease area. Dr. Johnson is a coinventor or coauthor of over 100 patents and scientific publications.

Louise Walsh joined Astex in 2017 as a medicinal chemist. Prior to this, she worked at Takeda Cambridge and legacy companies for 13 years. She has worked on a variety of projects targeting GPCRs and enzymes for both CNS and peripheral end points. She has an M.Chem from the University of Durham and a Ph.D in Chemistry from the University of Cambridge.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01803.

Graphs that compare ClogP, LE, LLE, and deviation from planarity of hits and leads (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): D.A.E. is a shareholder of Carmot Therapeutics Inc. and an employee and shareholder of Frontier Medicines. W.J. is an employee and shareholder of Novartis. C.N.J., L.W. are employees of Astex Pharmaceuticals.

Supplementary Material

References

- Osborne J.; Panova S.; Rapti M.; Urushima T.; Jhoti H. Fragments: Where Are We Now?. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020, 48, 271–280. 10.1042/BST20190694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Practical Fragments. https://practicalfragments.blogspot.com/ (accessed 2021-09-26).

- Johnson C. N.; Erlanson D. A.; Murray C. W.; Rees D. C. Fragment-to-Lead Medicinal Chemistry Publications in 2015. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60 (1), 89–99. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C. N.; Erlanson D. A.; Jahnke W.; Mortenson P. N.; Rees D. C. Fragment-to-Lead Medicinal Chemistry Publications in 2016. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61 (5), 1774–1784. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortenson P. N.; Erlanson D. A.; De Esch I. J. P.; Jahnke W.; Johnson C. N. Fragment-to-Lead Medicinal Chemistry Publications in 2017. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62 (8), 3857–3872. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlanson D. A.; De Esch I. J. P.; Jahnke W.; Johnson C. N.; Mortenson P. N. Fragment-to-Lead Medicinal Chemistry Publications in 2018. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (9), 4430–4444. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke W.; Erlanson D. A.; De Esch I. J. P.; Johnson C. N.; Mortenson P. N.; Ochi Y.; Urushima T. Fragment-to-Lead Medicinal Chemistry Publications in 2019. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (24), 15494–15507. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SciFinder. https://www.cas.org/solutions/cas-scifinder-discovery-platform/cas-scifinder (accessed 2021-09-26).

- Romasanta A. K. S.; van der Sijde P.; Hellsten I.; Hubbard R. E.; Keseru G. M.; van Muijlwijk-Koezen J.; de Esch I. J. P. When Fragments Link: A Bibliometric Perspective on the Development of Fragment-Based Drug Discovery. Drug Discovery Today 2018, 23 (9), 1596–1609. 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. W.; Rees D. C. The Rise of Fragment-Based Drug Discovery. Nat. Chem. 2009, 1 (3), 187–192. 10.1038/nchem.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.; Fang X.; Wang C.; Hua Y.; Huang C.; Wang M.; Zhu L.; Wang Z.; Gao Y.; Zhang T.; Liu H.; Zhang Y.; Lu S.; Lu T.; Chen Y.; Li H. Design and Synthesis of 1H-Indazole-3-Carboxamide Derivatives as Potent and Selective PAK1 Inhibitors with Anti-Tumour Migration and Invasion Activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 203, 112517. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atobe M.; Serizawa T.; Yamakawa N.; Takaba K.; Nagano Y.; Yamaura T.; Tanaka E.; Tazumi A.; Bito S.; Ishiguro M.; Kawanishi M. Discovery of 4,6- And 5,7-Disubstituted Isoquinoline Derivatives as a Novel Class of Protein Kinase C ζ Inhibitors with Fragment-Merging Strategy. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (13), 7143–7162. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori I.; Wakabayashi T.; Murakami M.; Okabe A.; Ishii T.; McGrath A.; Zou H.; Saikatendu K. S.; Imoto H. Discovery of Novel and Highly Selective Cyclopropane ALK Inhibitors through a Fragment-Assisted, Structure-Based Drug Design. ACS Omega 2020, 5 (49), 31984–32001. 10.1021/acsomega.0c04900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen B. B.; Jepsen T. H.; Larsen M.; Sindet R.; Vifian T.; Burhardt M. N.; Larsen J.; Seitzberg J. G.; Carnerup M. A.; Jerre A.; Mølck C.; Lovato P.; Rai S.; Nasipireddy V. R.; Ritzén A. Fragment-Based Discovery of Pyrazolopyridones as JAK1 Inhibitors with Excellent Subtype Selectivity. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (13), 7008–7032. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski J.; Liu B.; Pang S.; Ahmad N. H. B.; Wang G.; Poulsen A.; Yang H.; Poh Y. R.; Tee D. H. Y.; Ong E.; Retna P.; Dinie N.; Kwek P.; Wee J. L. K.; Manoharan V.; Low C. B.; Seah P. G.; Pendharkar V.; Sangthongpitag K.; Joy J.; Baburajendran N.; Jansson A. E.; Nacro K.; Hill J.; Keller T. H.; Hung A. W. Stepwise Evolution of Fragment Hits against MAPK Interacting Kinases 1 and 2. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (2), 621–637. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schade M.; Merla B.; Lesch B.; Wagener M.; Timmermanns S.; Pletinckx K.; Hertrampf T. Highly Selective Sub-Nanomolar Cathepsin S Inhibitors by Merging Fragment Binders with Nitrile Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (20), 11801–11808. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2FQ9: Cathepsin S with nitrile inhibitor. RCSB PDB. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/2FQ9 (accessed 2021-09-26).

- Sabbah M.; Mendes V.; Vistal R. G.; Dias D. M. G.; Záhorszká M.; Mikušová K.; Korduláková J.; Coyne A. G.; Blundell T. L.; Abell C. Fragment-Based Design of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Inha Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (9), 4749–4761. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y.; Takashima H.; Walmsley D. L.; Ushiyama F.; Matsuda Y.; Kanazawa H.; Yamaguchi-Sasaki T.; Tanaka-Yamamoto N.; Yamagishi J.; Kurimoto-Tsuruta R.; Ogata Y.; Ohtake N.; Angove H.; Baker L.; Harris R.; Macias A.; Robertson A.; Surgenor A.; Watanabe H.; Nakano K.; Mima M.; Iwamoto K.; Okada A.; Takata I.; Hitaka K.; Tanaka A.; Fujita K.; Sugiyama H.; Hubbard R. E. Fragment-Based Discovery of Novel Non-Hydroxamate LpxC Inhibitors with Antibacterial Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (23), 14805–14820. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F.; Hu H.; Wang K.; Peng C.; Xu W.; Zhang Y.; Gao J.; Liu Y.; Zhou H.; Huang R.; Li M.; Shen J.; Xu Y. Identification of Highly Selective Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2) Inhibitors by a Covalent Fragment-Based Approach. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (13), 7052–7065. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackie J. A.; Bloomer J. C.; Brown M. J. B.; Cheng H. Y.; Hammond B.; Hickey D. M. B.; Ife R. J.; Leach C. A.; Lewis V. A.; Macphee C. H.; Milliner K. J.; Moores K. E.; Pinto I. L.; Smith S. A.; Stansfield I. G.; Stanway S. J.; Taylor M. A.; Theobald C. J. The Identification of Clinical Candidate SB-480848: A Potent Inhibitor of Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13 (6), 1067–1070. 10.1016/S0960-894X(03)00058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushiyama F.; Amada H.; Takeuchi T.; Tanaka-Yamamoto N.; Kanazawa H.; Nakano K.; Mima M.; Masuko A.; Takata I.; Hitaka K.; Iwamoto K.; Sugiyama H.; Ohtake N. Lead Identification of 8-(Methylamino)-2-Oxo-1,2-Dihydroquinoline Derivatives as DNA Gyrase Inhibitors: Hit-to-Lead Generation Involving Thermodynamic Evaluation. ACS Omega 2020, 5 (17), 10145–10159. 10.1021/acsomega.0c00865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahy W.; Willis N. J.; Zhao Y.; Woodward H. L.; Svensson F.; Sipthorp J.; Vecchia L.; Ruza R. R.; Hillier J.; Kjær S.; Frew S.; Monaghan A.; Bictash M.; Salinas P. C.; Whiting P.; Vincent J. P.; Jones E. Y.; Fish P. V. 5-Phenyl-1,3,4-Oxadiazol-2(3 H)-Ones Are Potent Inhibitors of Notum Carboxylesterase Activity Identified by the Optimization of a Crystallographic Fragment Screening Hit. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (21), 12942–12956. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahy W.; Patel M.; Steadman D.; Woodward H. L.; Atkinson B. N.; Svensson F.; Willis N. J.; Flint A.; Papatheodorou D.; Zhao Y.; Vecchia L.; Ruza R. R.; Hillier J.; Frew S.; Monaghan A.; Costa A.; Bictash M.; Walter M. W.; Jones E. Y.; Fish P. V. Screening of a Custom-Designed Acid Fragment Library Identifies 1-Phenylpyrroles and 1-Phenylpyrrolidines as Inhibitors of Notum Carboxylesterase Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (17), 9464–9483. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefke L.; Hiesinger K.; Zhu W. F.; Kramer J. S.; Proschak E. Computer-Aided Fragment Growing Strategies to Design Dual Inhibitors of Soluble Epoxide Hydrolase and LTA4 Hydrolase. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11 (6), 1244–1249. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellaway C. R.; Amans D.; Bamborough P.; Barnett H.; Bit R. A.; Brown J. A.; Carlson N. R.; Chung C. W.; Cooper A. W. J.; Craggs P. D.; Davis R. P.; Dean T. W.; Evans J. P.; Gordon L.; Harada I. L.; Hirst D. J.; Humphreys P. G.; Jones K. L.; Lewis A. J.; Lindon M. J.; Lugo D.; Mahmood M.; McCleary S.; Medeiros P.; Mitchell D. J.; O’Sullivan M.; Le Gall A.; Patel V. K.; Patten C.; Poole D. L.; Shah R. R.; Smith J. E.; Stafford K. A. J.; Thomas P. J.; Vimal M.; Wall I. D.; Watson R. J.; Wellaway N.; Yao G.; Prinjha R. K. Discovery of a Bromodomain and Extraterminal Inhibitor with a Low Predicted Human Dose through Synergistic Use of Encoded Library Technology and Fragment Screening. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (2), 714–746. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal J. T.; Atkinson S. J.; Aylott H.; Bamborough P.; Chung C. W.; Copley R. C. B.; Gordon L.; Grandi P.; Gray J. R. J.; Harrison L. A.; Hayhow T. G.; Lindon M.; Messenger C.; Michon A. M.; Mitchell D.; Preston A.; Prinjha R. K.; Rioja I.; Taylor S.; Wall I. D.; Watson R. J.; Woolven J. M.; Demont E. H. The Optimization of a Novel, Weak Bromo and Extra Terminal Domain (BET) Bromodomain Fragment Ligand to a Potent and Selective Second Bromodomain (BD2) Inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (17), 9093–9126. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Xiao S.; Yang Y.; Chen C.; Lu T.; Chen Z.; Jiang H.; Chen S.; Luo C.; Zhou B. Discovery of 8-Methyl-Pyrrolo[1,2-a]Pyrazin-1(2 H)-One Derivatives as Highly Potent and Selective Bromodomain and Extra-Terminal (BET) Bromodomain Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (8), 3956–3975. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel K. F.; Wang L.; Soltwedel T.; Fidanze S. D.; Hasvold L. A.; Liu D.; Mantei R. A.; Pratt J. K.; Sheppard G. S.; Bui M. H.; Faivre E. J.; Huang X.; Li L.; Lin X.; Wang R.; Warder S. E.; Wilcox D.; Albert D. H.; Magoc T. J.; Rajaraman G.; Park C. H.; Hutchins C. W.; Shen J. J.; Edalji R. P.; Sun C. C.; Martin R.; Gao W.; Wong S.; Fang G.; Elmore S. W.; Shen Y.; Kati W. M. Discovery of N-(4-(2,4-Difluorophenoxy)-3-(6-Methyl-7-Oxo-6,7-Dihydro-1H-Pyrrolo[2,3-c]Pyridin-4-Yl)Phenyl)Ethanesulfonamide (ABBV-075/Mivebresib), a Potent and Orally Available Bromodomain and Extraterminal Domain (BET) Family Bromodomain Inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60 (20), 8369–8384. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacón Simon S.; Wang F.; Thomas L. R.; Phan J.; Zhao B.; Olejniczak E. T.; MacDonald J. D.; Shaw J. G.; Schlund C.; Payne W.; Creighton J.; Stauffer S. R.; Waterson A. G.; Tansey W. P.; Fesik S. W. Discovery of WD Repeat-Containing Protein 5 (WDR5)-MYC Inhibitors Using Fragment-Based Methods and Structure-Based Design. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (8), 4315–4333. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moningka R.; Romero F. A.; Hastings N. B.; Guo Z.; Wang M.; Di Salvo J.; Li Y.; Trusca D.; Deng Q.; Tong V.; Terebetski J. L.; Ball R. G.; Ujjainwalla F. Fragment-Based Lead Discovery of a Novel Class of Small Molecule Antagonists of Neuropeptide B/W Receptor Subtype 1 (GPR7). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30 (23), 127510. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H.; Zou Y.; Chen G.; Dou H.; Xie H.; Yuan X.; Zhang X.; Zhang N.; Li M.; Xu Y. Exploration of Fragment Binding Poses Leading to Efficient Discovery of Highly Potent and Orally Effective Inhibitors of FABP4 for Anti-Inflammation. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (8), 4090–4106. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b02107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo A.; Weininger D.. Clogp Reference Manual. Daylight Version 4.9. Daylight Chemical Information Systems, Inc. https://www.daylight.com/dayhtml/doc/clogp/ (accessed 2022-11-01).

- Hopkins A. L.; Groom C. R.; Alex A. Ligand Efficiency: A Useful Metric for Lead Selection. Drug Discovery Today 2004, 9, 430–431. 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeson P. D.; Springthorpe B. The Influence of Drug-like Concepts on Decision-Making in Medicinal Chemistry. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2007, 6 (11), 881–890. 10.1038/nrd2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckmans T.; Edwards M. P.; Horne V. A.; Correia A. M.; Owen D. R.; Thompson L. R.; Tran I.; Tutt M. F.; Young T. Rapid Assessment of a Novel Series of Selective CB2 Agonists Using Parallel Synthesis Protocols: A Lipophilic Efficiency (LipE) Analysis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19 (15), 4406–4409. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortenson P. N.; Murray C. W. Assessing the Lipophilicity of Fragments and Early Hits. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2011, 25 (7), 663–667. 10.1007/s10822-011-9435-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. Z.; Shi X. X.; Huang G. Y.; Hao G. F.; Yang G. F. Fragment-Based Drug Design Facilitates Selective Kinase Inhibitor Discovery. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 42, 551–565. 10.1016/j.tips.2021.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwood M. M.; Fabbro D.; Sokolov A. V.; Knapp S.; Schiöth H. B. Trends in Kinase Drug Discovery: Targets, Indications and Inhibitor Design. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2021, 20 (11), 839–861. 10.1038/s41573-021-00252-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makraki E.; Darby J. F.; Carneiro M. G.; Firth J. D.; Heyam A.; AB E.; O'Brien P.; Siegal G.; Hubbard R. E. Fragment-Derived Modulators of an Industrial β-Glucosidase. Biochem. J. 2020, 477 (22), 4383–4395. 10.1042/BCJ20200507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solbak S. M. Ø.; Zang J.; Narayanan D.; Høj L. J.; Bucciarelli S.; Softley C.; Meier S.; Langkilde A. E.; Gotfredsen C. H.; Sattler M.; Bach A. Developing Inhibitors of the P47phox-P22phox Protein-Protein Interaction by Fragment-Based Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (3), 1156–1177. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musielak B.; Janczyk W.; Rodriguez I.; Plewka J.; Sala D.; Magiera-Mularz K.; Holak T. Competition NMR for Detection of Hit/Lead Inhibitors of Protein-Protein Interactions. Molecules 2020, 25 (13), 3017. 10.3390/molecules25133017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillory X.; Wolter M.; Leysen S.; Neves J. F.; Kuusk A.; Genet S.; Somsen B.; Morrow J. K.; Rivers E.; Van Beek L.; Patel J.; Goodnow R.; Schoenherr H.; Fuller N.; Cao Q.; Doveston R. G.; Brunsveld L.; Arkin M. R.; Castaldi P.; Boyd H.; Landrieu I.; Chen H.; Ottmann C. Fragment-Based Differential Targeting of PPI Stabilizer Interfaces. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (13), 6694–6707. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijbesma E.; Somsen B. A.; Miley G. P.; Leijten-Van De Gevel I. A.; Brunsveld L.; Arkin M. R.; Ottmann C. Fluorescence Anisotropy-Based Tethering for Discovery of Protein-Protein Interaction Stabilizers. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15 (12), 3143–3148. 10.1021/acschembio.0c00646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijbesma E.; Hallenbeck K. K.; Leysen S.; De Vink P. J.; Skóra L.; Jahnke W.; Brunsveld L.; Arkin M. R.; Ottmann C. Site-Directed Fragment-Based Screening for the Discovery of Protein-Protein Interaction Stabilizers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (8), 3524–3531. 10.1021/jacs.8b11658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter M.; Valenti D.; Cossar P. J.; Levy L. M.; Hristeva S.; Genski T.; Hoffmann T.; Brunsveld L.; Tzalis D.; Ottmann C. Fragment-Based Stabilizers of Protein–Protein Interactions through Imine-Based Tethering. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (48), 21520–21524. 10.1002/anie.202008585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- https://ambagontx.com/ (accessed 2021-09-26).

- Suresh B. M.; Li W.; Zhang P.; Wang K. W.; Yildirim I.; Parker C. G.; Disney M. D. A General Fragment-Based Approach to Identify and Optimize Bioactive Ligands Targeting RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117 (52), 33197–33203. 10.1073/pnas.2012217117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzaoui K.; Blommers M.; Götte M.; Zimmermann K.; Liu H.; Fretz H. Discovery of Small Molecule Drugs Targeting the Biogenesis of MicroRNA-155 for the Treatment of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Chimia 2020, 74 (10), 798–802. 10.2533/chimia.2020.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul R.; Dutta D.; Paul R.; Dash J. Target-Directed Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition for Assembling HIV-1 TAR RNA Binding Ligands. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (30), 12407–12411. 10.1002/anie.202003461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douangamath A.; Fearon D.; Gehrtz P.; Krojer T.; Lukacik P.; Owen C. D.; Resnick E.; Strain-Damerell C.; Aimon A.; Ábrányi-Balogh P.; Brandão-Neto J.; Carbery A.; Davison G.; Dias A.; Downes T. D.; Dunnett L.; Fairhead M.; Firth J. D.; Jones S. P.; Keeley A.; Keserü G. M.; Klein H. F.; Martin M. P.; Noble M. E. M.; O’Brien P.; Powell A.; Reddi R. N.; Skyner R.; Snee M.; Waring M. J.; Wild C.; London N.; von Delft F.; Walsh M. A. Crystallographic and Electrophilic Fragment Screening of the SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 5047. 10.1038/s41467-020-18709-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlanson D. A. Many Small Steps towards a COVID-19 Drug. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 5048. 10.1038/s41467-020-18710-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodera J.; Lee A. A.; London N.; von Delft F. Crowdsourcing Drug Discovery for Pandemics. Nat. Chem. 2020, 12 (7), 581. 10.1038/s41557-020-0496-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H.; Cheng K.; Gao Y.; Bai W.; Wu C.; He W.; Li C.; Li Z. A Novel Potent Metal-Binding NDM-1 Inhibitor Was Identified by Fragment Virtual, SPR and NMR Screening. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28 (9), 115437. 10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberger T.; Ferreira G. M.; de Souza A. D. F.; da Silva Santos S.; Poso A.; Ribeiro J. A.; Tavares M. T.; Pavan F. R.; Trossini G. H. G.; Dias M. V. B.; Parise-Filho R. Design, Synthesis and Biological Activity of Novel Substituted 3-Benzoic Acid Derivatives as MtDHFR Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28 (15), 115600. 10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faïon L.; Djaout K.; Frita R.; Pintiala C.; Cantrelle F. X.; Moune M.; Vandeputte A.; Bourbiaux K.; Piveteau C.; Herledan A.; Biela A.; Leroux F.; Kremer L.; Blaise M.; Tanina A.; Wintjens R.; Hanoulle X.; Déprez B.; Willand N.; Baulard A. R.; Flipo M. Discovery of the First Mycobacterium Tuberculosis MabA (FabG1) Inhibitors through a Fragment-Based Screening. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 200, 112440. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassaan E.; Hohn C.; Ehrmann F. R.; Goetzke F. W.; Movsisyan L.; Hüfner-Wulsdorf T.; Sebastiani M.; Härtsch A.; Reuter K.; Diederich F.; Klebe G. Fragment Screening Hit Draws Attention to a Novel Transient Pocket Adjacent to the Recognition Site of the TRNA-Modifying Enzyme TGT. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (13), 6802–6820. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S. E.; Whitehouse A. J.; Brown K.; Burbaud S.; Belardinelli J. M.; Sangen J.; Lahiri R.; Libardo M. D. J.; Gupta P.; Malhotra S.; Boshoff H. I. M.; Jackson M.; Abell C.; Coyne A. G.; Blundell T. L.; Floto R. A.; Mendes V. Fragment-Based Discovery of a New Class of Inhibitors Targeting Mycobacterial TRNA Modification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48 (14), 8099–8112. 10.1093/nar/gkaa539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart D. E. A.; Stanley M.; Raimi O. G.; Robinson D. A.; Boldovjakova D.; Squair D. R.; Ferenbach A. T.; Fang W.; van Aalten D. M. F. Targeting a Critical Step in Fungal Hexosamine Biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295 (26), 8678–8691. 10.1074/jbc.RA120.012985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza M. L.; De Oliveira Rezende Junior C.; Ferreira R. S.; Espinoza Chávez R. M.; Ferreira L. L. G.; Slafer B. W.; Magalhães L. G.; Krogh R.; Oliva G.; Cruz F. C.; Dias L. C.; Andricopulo A. D. Discovery of Potent, Reversible, and Competitive Cruzain Inhibitors with Trypanocidal Activity: A Structure-Based Drug Design Approach. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60 (2), 1028–1041. 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münzker L.; Petrick J. K.; Schleberger C.; Clavel D.; Cornaciu I.; Wilcken R.; Márquez J. A.; Klebe G.; Marzinzik A.; Jahnke W. Fragment-Based Discovery of Non-Bisphosphonate Binders of Trypanosoma Brucei Farnesyl Pyrophosphate Synthase. ChemBioChem. 2020, 21, 3096–3111. 10.1002/cbic.202000246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurin C. M. C.; Bluck J. P.; Chan A. K. N.; Keller M.; Boczek A.; Scorah A. R.; See K. F. L.; Jennings L. E.; Hewings D. S.; Woodhouse F.; Reynolds J. K.; Schiedel M.; Humphreys P. G.; Biggin P. C.; Conway S. J. Fragment-Based Identification of Ligands for Bromodomain-Containing Factor 3 of Trypanosoma Cruzi. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7 (8), 2238–2249. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messick T. E.; Tolvinski L.; Zartler E. R.; Moberg A.; Frostell Å.; Smith G. R.; Reitz A. B.; Lieberman P. M. Biophysical Screens Identify Fragments That Bind to the Viral DNA-Binding Proteins EBNA1 and LANA. Molecules 2020, 25 (7), 1760. 10.3390/molecules25071760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zender M.; Witzgall F.; Kiefer A.; Kirsch B.; Maurer C. K.; Kany A. M.; Xu N.; Schmelz S.; Börger C.; Blankenfeldt W.; Empting M. Flexible Fragment Growing Boosts Potency of Quorum-Sensing Inhibitors against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Virulence. ChemMedChem 2020, 15 (2), 188–194. 10.1002/cmdc.201900621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mureddu L. G.; Ragan T. J.; Brooksbank E. J.; Vuister G. W. CcpNmr AnalysisScreen, a New Software Programme with Dedicated Automated Analysis Tools for Fragment-Based Drug Discovery by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 2020, 74 (10–11), 565–577. 10.1007/s10858-020-00321-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fino R.; Byrne R.; Softley C. A.; Sattler M.; Schneider G.; Popowicz G. M. Introducing the CSP Analyzer: A Novel Machine Learning-Based Application for Automated Analysis of Two-Dimensional NMR Spectra in NMR Fragment-Based Screening. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 603–611. 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingel A.; Vulpetti A.; Reinsperger T.; Proudfoot A.; Denay R.; Frommlet A.; Henry C.; Hommel U.; Gossert A. D.; Luy B.; Frank A. O. Comprehensive and High-Throughput Exploration of Chemical Space Using Broadband 19F NMR-Based Screening. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (35), 14809–14817. 10.1002/anie.202002463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. A.; Olson N. M.; Tooker M. J.; Bur S. K.; Pomerantz W. C. K. Combined Protein- And Ligand-Observed NMR Workflow to Screen Fragment Cocktails against Multiple Proteins: A Case Study Using Bromodomains. Molecules 2020, 25 (17), 3949. 10.3390/molecules25173949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman A.; Duong-Thi M. D.; Pervushin K.; Ohlson S.; Mehta J. S. Pharmaceutical Modulation of the Proteolytic Profile of Transforming Growth Factor Beta Induced Protein (TGFBIp) Offers a New Avenue for Treatment of TGFBI-Corneal Dystrophy. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 24, 529–543. 10.1016/j.jare.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecas L.; Hartmann L.; Caro L.; Mohamed-Bouteben S.; Raingeval C.; Krimm I.; Wagner R.; Dugas V.; Demesmay C. Miniaturized Weak Affinity Chromatography for Ligand Identification of Nanodiscs-Embedded G-Protein Coupled Receptors. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1113, 26–35. 10.1016/j.aca.2020.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima G. M. A.; Talibov V. O.; Jagudin E.; Sele C.; Nyblom M.; Knecht W.; Logan D. T.; Sjogren T.; Mueller U. FragMAX: The Fragment-Screening Platform at the MAX IV Laboratory. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Struct. Biol. 2020, 76 (8), 771–777. 10.1107/S205979832000889X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley M. R.; Ilyichova O. V.; Wang G.; Williams M. L.; Sharma G.; Alwan W. S.; Whitehouse R. L.; Mohanty B.; Scammells P. J.; Heras B.; Martin J. L.; Totsika M.; Capuano B.; Doak B. C.; Scanlon M. J. Rapid Elaboration of Fragments into Leads by X-Ray Crystallographic Screening of Parallel Chemical Libraries (REFiLX). J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (13), 6863–6875. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker L. M.; Aimon A.; Murray J. B.; Surgenor A. E.; Matassova N.; Roughley S. D.; Collins P. M.; Krojer T.; von Delft F.; Hubbard R. E. Rapid Optimisation of Fragments and Hits to Lead Compounds from Screening of Crude Reaction Mixtures. Commun. Chem. 2020, 3 (1), 3122. 10.1038/s42004-020-00367-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saur M.; Hartshorn M. J.; Dong J.; Reeks J.; Bunkoczi G.; Jhoti H.; Williams P. A. Fragment-Based Drug Discovery Using Cryo-EM. Drug Discovery Today 2020, 25 (3), 485–490. 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clabbers M. T. B.; Fisher S. Z.; Coinçon M.; Zou X.; Xu H. Visualizing Drug Binding Interactions Using Microcrystal Electron Diffraction. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3 (1), 417. 10.1038/s42003-020-01155-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens K.; Wroblowski B.; Langini C.; van Vlijmen H.; Caflisch A.; De Winter H. Assessment of the Fragment Docking Program SEED. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60 (10), 4881–4893. 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachman M.; Bajusz D.; Hetényi A.; Scarpino A.; Mero B.; Egyed A.; Buday L.; Barril X.; Keseru G. M. Discovery of a Novel Kinase Hinge Binder Fragment by Dynamic Undocking. RSC Med. Chem. 2020, 11 (5), 552–558. 10.1039/C9MD00519F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chachulski L.; Windshügel B. LEADS-FRAG: A Benchmark Data Set for Assessment of Fragment Docking Performance. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60 (12), 6544–6554. 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sydow D.; Schmiel P.; Mortier J.; Volkamer A. KinFragLib: Exploring the Kinase Inhibitor Space Using Subpocket-Focused Fragmentation and Recombination. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60 (12), 6081–6094. 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanev G. K.; De Graaf C.; Westerman B. A.; De Esch I. J. P.; Kooistra A. J. KLIFS: An Overhaul after the First 5 Years of Supporting Kinase Research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49 (D1), D562–D569. 10.1093/nar/gkaa895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield A. E.; Yueh C.; Beglov D.; Castilho M. S.; Kozakov D.; Keserü G. M.; Whitty A.; Vajda S. Benchmark Sets for Binding Hot Spot Identification in Fragment-Based Ligand Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60 (12), 6612–6623. 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olp M. D.; Sprague D. J.; Goetz C. J.; Kathman S. G.; Wynia-Smith S. L.; Shishodia S.; Summers S. B.; Xu Z.; Statsyuk A. V.; Smith B. C. Covalent-Fragment Screening of BRD4 Identifies a Ligandable Site Orthogonal to the Acetyl-Lysine Binding Sites. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15 (4), 1036–1049. 10.1021/acschembio.0c00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imrie F.; Bradley A. R.; Van Der Schaar M.; Deane C. M. Deep Generative Models for 3D Linker Design. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60 (4), 1983–1995. 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b01120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancet A.; Raingeval C.; Lomberget T.; Le Borgne M.; Guichou J. F.; Krimm I. Fragment Linking Strategies for Structure-Based Drug Design. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (20), 11420–11435. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez C.; Soler D.; Soliva R.; Guallar V. FragPELE: Dynamic Ligand Growing within a Binding Site. A Novel Tool for Hit-To-Lead Drug Design. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60 (3), 1728–1736. 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J. A New Approach to Finding Natural Chemical Structure Classes. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45 (24), 5311–5320. 10.1021/jm010520k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chessari G.; Grainger R.; Holvey R. S.; Ludlow R. F.; Mortenson P. N.; Rees D. C. C–H Functionalisation Tolerant to Polar Groups Could Transform Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD). Chem. Sci. 2021, 12 (36), 11976–11985. 10.1039/D1SC03563K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton D. J.; Dekker T.; Klein H. F.; Janssen G. V.; Wijtmans M.; O’Brien P.; de Esch I. J. P. Escape from planarity in fragment-based drug discovery: A physicochemical and 3D property analysis of synthetic 3D fragment libraries. Drug Discovery Today: Technol. 2020, 38, 77–90. 10.1016/j.ddtec.2021.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Denis J. D.; Hall R. J.; Murray C. W.; Heightman T. D.; Rees D. C. Fragment-Based Drug Discovery: Opportunities for Organic Synthesis. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12 (3), 321–329. 10.1039/D0MD00375A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd S. L.; Fowler E.; Reinhardt T.; Compton T.; Mateu N.; Newman H.; Bellini D.; Talon R.; McLoughlin J.; Krojer T.; Aimon A.; Bradley A.; Fairhead M.; Brear P.; Díaz-Sáez L.; McAuley K.; Sore H. F.; Madin A.; O’Donovan D. H.; Huber K. V. M.; Hyvönen M.; Von Delft F.; Dowson C. G.; Spring D. R. Demonstration of the Utility of DOS-Derived Fragment Libraries for Rapid Hit Derivatisation in a Multidirectional Fashion. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11 (39), 10792–10801. 10.1039/D0SC01232G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downes T. D.; Jones S. P.; Klein H. F.; Wheldon M. C.; Atobe M.; Bond P. S.; Firth J. D.; Chan N. S.; Waddelove L.; Hubbard R. E.; Blakemore D. C.; De Fusco C.; Roughley S. D.; Vidler L. R.; Whatton M. A.; Woolford A. J. A.; Wrigley G. L.; O’Brien P. Design and Synthesis of 56 Shape-Diverse 3D Fragments. Chem. - Eur. J. 2020, 26 (41), 8969–8975. 10.1002/chem.202001123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A. K.; Kirberger S. E.; Johnson J. A.; Kimbrough J. R.; Partridge D. K. D.; Pomerantz W. C. K. Efficient Synthesis of 1,4-Thiazepanones and 1,4-Thiazepanes as 3d Fragments for Screening Libraries. Org. Lett. 2020, 22 (10), 3946–3950. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troelsen N. S.; Shanina E.; Gonzalez-Romero D.; Danková D.; Jensen I. S. A.; Śniady K. J.; Nami F.; Zhang H.; Rademacher C.; Cuenda A.; Gotfredsen C. H.; Clausen M. H. The 3F Library: Fluorinated Fsp3-Rich Fragments for Expeditious 19F NMR Based Screening. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (6), 2204–2210. 10.1002/anie.201913125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanby A. R.; Troelsen N. S.; Osberger T. J.; Kidd S. L.; Mortensen K. T.; Spring D. R. Fsp3-Rich and Diverse Fragments Inspired by Natural Products as a Collection to Enhance Fragment-Based Drug Discovery. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56 (15), 2280–2283. 10.1039/C9CC09796A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osberger T. J.; Kidd S. L.; King T. A.; Spring D. R. C(Sp3)-H Arylation to Construct All-: Syn Cyclobutane-Based Heterobicyclic Systems: A Novel Fragment Collection. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56 (54), 7423–7426. 10.1039/D0CC03237A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison C. N.; Prosser K. E.; Stokes R. W.; Cordes A.; Metzler-Nolte N.; Cohen S. M. Expanding Medicinal Chemistry into 3D Space: Metallofragments as 3D Scaffolds for Fragment-Based Drug Discovery. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11 (5), 1216–1225. 10.1039/C9SC05586J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S. C.; Ball Z. T. Aminoquinoline-Rhodium(II) Conjugates as Src-Family SH3 Ligands. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10 (10), 1380–1385. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley A.; Petri L.; Ábrányi-Balogh P.; Keserű G. M. Covalent Fragment Libraries in Drug Discovery. Drug Discovery Today 2020, 25 (6), 983–996. 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Howard C. A.; Zari S.; Cho H. J.; Shukla S.; Li H.; Ndoj J.; González-Alonso P.; Nikolaidis C.; Abbott J.; Rogawski D. S.; Potopnyk M. A.; Kempinska K.; Miao H.; Purohit T.; Henderson A.; Mapp A.; Sulis M. L.; Ferrando A.; Grembecka J.; Cierpicki T. Covalent Inhibition of NSD1 Histone Methyltransferase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16 (12), 1403–1410. 10.1038/s41589-020-0626-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant E. K.; Fallon D. J.; Hann M. M.; Fantom K. G. M.; Quinn C.; Zappacosta F.; Annan R. S.; Chung C. wa; Bamborough P.; Dixon D. P.; Stacey P.; House D.; Patel V. K.; Tomkinson N. C. O.; Bush J. T. A Photoaffinity-Based Fragment-Screening Platform for Efficient Identification of Protein Ligands. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (47), 21096–21105. 10.1002/anie.202008361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futatsugi K.; Smith A. C.; Tu M.; Raymer B.; Ahn K.; Coffey S. B.; Dowling M. S.; Fernando D. P.; Gutierrez J. A.; Huard K.; Jasti J.; Kalgutkar A. S.; Knafels J. D.; Pandit J.; Parris K. D.; Perez S.; Pfefferkorn J. A.; Price D. A.; Ryder T.; Shavnya A.; Stock I. A.; Tsai A. S.; Tesz G. J.; Thuma B. A.; Weng Y.; Wisniewska H. M.; Xing G.; Zhou J.; Magee T. V. Discovery of PF-06835919: A Potent Inhibitor of Ketohexokinase (KHK) for the Treatment of Metabolic Disorders Driven by the Overconsumption of Fructose. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63 (22), 13546–13560. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faivre E. J.; McDaniel K. F.; Albert D. H.; Mantena S. R.; Plotnik J. P.; Wilcox D.; Zhang L.; Bui M. H.; Sheppard G. S.; Wang L.; Sehgal V.; Lin X.; Huang X.; Lu X.; Uziel T.; Hessler P.; Lam L. T.; Bellin R. J.; Mehta G.; Fidanze S.; Pratt J. K.; Liu D.; Hasvold L. A.; Sun C.; Panchal S. C.; Nicolette J. J.; Fossey S. L.; Park C. H.; Longenecker K.; Bigelow L.; Torrent M.; Rosenberg S. H.; Kati W. M.; Shen Y. Selective Inhibition of the BD2 Bromodomain of BET Proteins in Prostate Cancer. Nature 2020, 578 (7794), 306–310. 10.1038/s41586-020-1930-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.