Abstract

Objectives:

To compare (1) speech performance based on an auditive analysis and sonagraphy and (2) levels of oral impairment between fixed lingual and labial orthodontic appliances.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty-four patients with Class I division 1 malocclusion and moderate crowding of upper teeth were distributed randomly into two groups. Seventeen patients in group A (mean age: 20.6 years; standard deviation [SD]: 2.9 years) were treated with fixed lingual appliances (Stealth®, AO, Sheboygan, Wisc), whereas 17 patients in group B (mean age: 21.8 years; SD: 3.3 years) were treated with conventional fixed labial appliances. Speech performance was tested using spectrographic analysis of fricative /s/ sound before, immediately after (T1), 1 month after, and 3 months after bracket placement. The levels of oral impairment were assessed using standardized questionnaires.

Results:

A significant deterioration in articulation was recorded at all assessment times in group A but only at T1 in group B. Significant intergroup differences were recorded at all assessment times (P < .001). Speech difficulties were significantly higher in the lingual brackets group after 1 month of bracket placement (P < .001). Soft tissue irritation and chewing difficulty were significantly higher in the lingual appliance group after 24 hours of bracket placement (P < .001).

Conclusions:

The lingual appliance is more problematic than the labial one in terms of speech articulation. Although patients with both appliances suffered from different degrees of oral impairment, patients with lingual appliances had more untoward effects, particularly during the first month of treatment.

Keywords: Lingual brackets, Labial brackets, Auditive analysis, Spectrography, Oral impairment, Chewing difficulty

INTRODUCTION

Since their advent, lingual orthodontic appliances have provided an ultimate esthetic solution for patients who do not want visible orthodontic appliances. Recently, lingual orthodontic treatment outcomes have become similar and comparable to those produced by labial orthodontic treatment.1–4 However, brackets that are positioned at the lingual surfaces of teeth cause a change in the morphology of these surfaces, which may result in articulation problems.5–9

Brackets that are positioned against the tongue cause not only speech disturbances but also oral discomfort, difficulty in chewing, and tongue irritation.10–13 Masticatory and speech disturbances induced by lingual brackets may lead to social embarrassment that is greater than that originating from visible labial brackets.14

Many studies have investigated discomfort during orthodontic treatment with fixed labial appliances15–20 and with fixed lingual appliances separately,10–13 but few studies have compared patient discomfort between lingual and labial appliances simultaneously.5,14,21 However, the intensity and duration of oral discomfort caused by lingual appliances compared to that caused by labial appliances are not clear yet, and to date there is no published study comparing speech performance between labial and lingual fixed orthodontic treatment that employed acoustic analysis and sonagraphy. Additionally, all of these studies comparing levels of discomfort and/or speech performance between the two treatment modalities have failed to assign patients to groups randomly (ie, selection bias may have been present in these investigations). The assessment of speech disturbances may differ from language to language,21 and it seems that there are no published data about speech impairment following bracket bonding in patients speaking Arabic as their native language. The objectives of the current randomized controlled trial were to compare (1) levels of speech performance based on auditive analysis and sonagraphy and (2) levels of oral impairment between lingual and labial orthodontic appliances.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Recruitment and Assignment

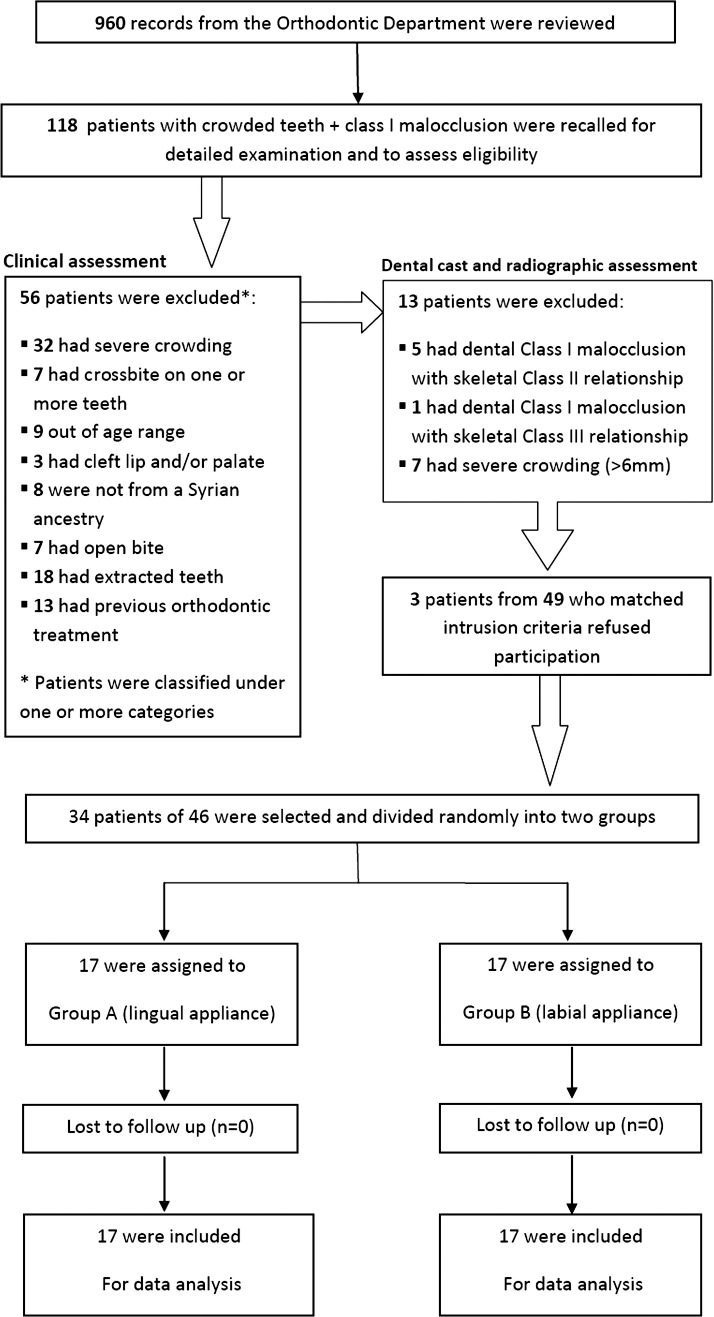

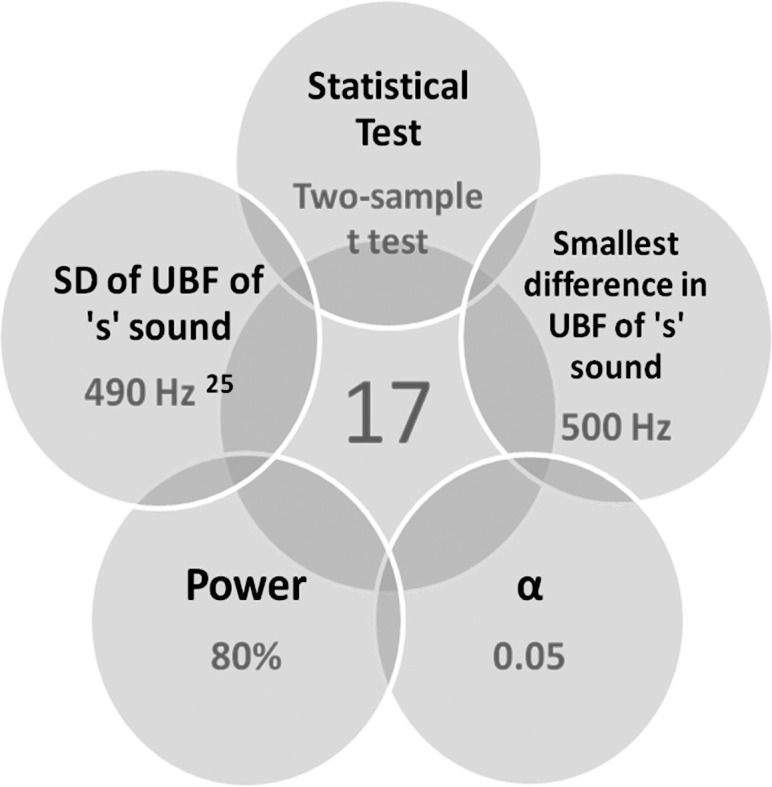

This was a parallel-group, randomized, controlled trial conducted in Syria. This research project was approved by the University Al-Baath Dental School (UBDS) Ethics Committee and was funded by the University of Al-Baath Postgraduate Research Budget. Sample size calculation was undertaken using Minitab® 15 (Minitab Inc, State College, Pa; Figure 1 with the calculation assumptions). Seventeen participants were required for each group. Records of 960 patients who were referred to the Orthodontic Department at UBDS (from January 2010 to January 2011) were reviewed. The UBDS is located in the middle of Hamah and provides a wide range of dental services for people coming from different places in the Hamah and Homs provinces, which are located in the middle of Syria. One hundred and eighteen patients were possible candidates for this research project because they had Class I malocclusion and crowding in their upper teeth, as documented in their records.

Figure 1.

Sample size estimation with its five assumptions. SD indicates standard deviation; UBF, upper boundary frequency.

Prospective participants were recalled for further assessment of eligibility. The first step involved a clinical examination to evaluate the following inclusion criteria: (1) Class I division 1 malocclusion on a Class I skeletal relationship; (2) moderate crowding in the upper dental arch (3 to 5–mm tooth-size arch-length discrepancy) that could be treated on a nonextraction basis (relying on a clinical judgment of the authors' approval of the treatment plan; (3) age range of 15 to 30 years; (4) the presence of all permanent teeth with the exclusion of third molars; (5) mother tongue of participants that was Arabic and from a Syrian ancestry; (6) no previous orthodontic treatment; (7) no anterior crossbites; and (8) no craniofacial syndromes, cleft lip and/or palate (soft and/or hard), dialects, or history of speech and hearing disorder.

Sixty-two patients met the inclusion criteria and were subjected in a second step to impression-taking, space analysis, and radiographic evaluation (eg, the ANB angle in the assessment of skeletal relationships) to confirm the above-mentioned inclusion criteria; this second step yielded 49 suitable participants. The clinical trial design was explained to the prospective patients orally and in a written format. Three patients declined participation in this study and preferred to undergo conventional orthodontic treatment, while 46 patients gave their informed consent. Thirty-four patients (21 females, 13 males; mean age: 21.25 years; standard deviation [SD]: 3.1 years) were selected randomly to construct the primary sample. They were divided into two groups; patient assignment was based on computer-generated random numbers (Figure 2). The allocation procedure was concealed from the researcher and was conducted by one of the co-authors.

Figure 2.

Participants flow chart.

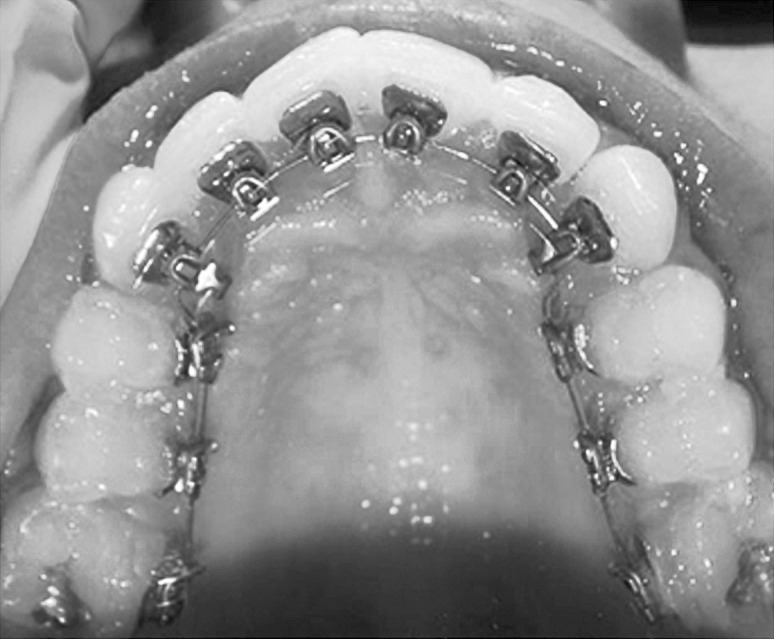

Group A consisted of 17 patients (11 females, six males; mean age: 20.6 years; SD: 2.9 years). Patients in this group were treated with lingual brackets (Stealth®, American Orthodontics, Sheboygan, Wisc). Lingual brackets were indirectly bonded in the upper arch only using the TARG+TR System (torque angulation reference guide + thickness & rotation).22 The initial archwires were 0.012-inch copper nickel-titanium (NiTi) wires (Figure 3). Slight bite ramps were bonded to the occlusal surfaces of lower first molars to achieve an approximately 1-mm bite-opening effect, which allowed slight contact between the incisal edges of at least three lower incisors and the upper lingual brackets.

Figure 3.

Stealth® brackets used in group A.

Figure 4.

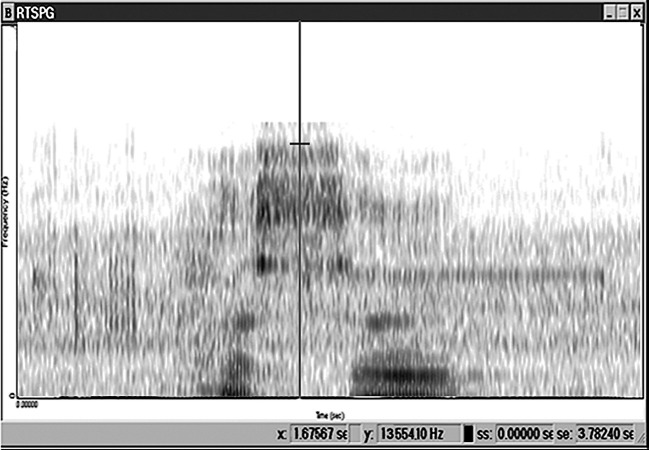

Spectrogram of the Arabic word ‘Hassan.’

Group B consisted of 17 patients (10 females, seven males; mean age: 21.8 years; SD: 3.3 years). Patients in group B were treated with labial straight-wire appliances (American Orthodontics brackets, Mini-Master series, Roth® prescription). Labial brackets were directly bonded on the upper arch only, and the initial archwires were 0.012-inch copper NiTi wires.

Auditive Analysis

Speech performance was evaluated by an auditive analysis conducted directly before bracket placement on the maxilla (T0), immediately following bracket placement (T1), 1 month later (±3 days) (T2), and 3 months later (±1 week) (T3). The word “Hassan” was read aloud in an anechoic quiet room and recorded digitally in standardized conditions; the target words were subsequently sampled into a computer. The frequency of the /s/ sound was measured using Kay Elemetrics CSL 3150b system (Kay Elemectrics, Pine Brook, NY). This method allowed the frequency and duration of the speech signal to be represented and recorded.23,24

A spectrogram was used to analyze the upper boundary frequency of the fricative sound /s/. This is defined as the maximum frequency of the band width of the fricative sound, represented in the spectrogram as the range of maximum grayness (Figure 4). The center 50 ms on the x-axis of each /s/ sound was used for measurement, as described by Hohoff et al.25

Oral Impairment Assessment

Using a standardized questionnaire comprising five questions with four-point Likert-scale possible answers, patients were asked to provide their subjective opinion about any possible effects—such as oral discomfort, speech impairment, mastication difficulties—at the following time points: T0, T1, T2, and T3.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Minitab® 15 (Minitab Inc, State College, Pa). Paired-sample t-tests or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank tests (the nonparametric equivalent) were employed to evaluate intragroup changes, whereas two-sample t-tests (or Mann-Whitney U-tests) were applied to examine intergroup differences (with α set at .05).

RESULTS

Auditive Analysis

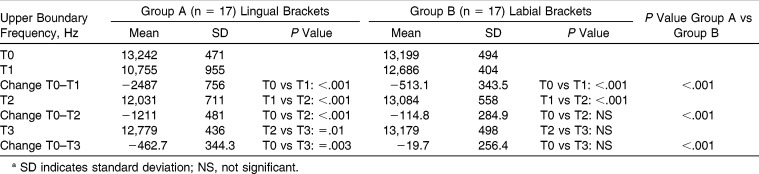

In group A and before bracket placement, the mean upper boundary frequency of the /s/ sound was 13,242 Hz (Table 1). At T1, a highly significant drop was observed, with a mean value of 10,755 Hz. The mean upper boundary frequency value arose to 12,031 Hz at T2. At T3, the mean upper boundary frequency value increased again to reach 12,779 Hz, and this value was significantly different from the mean value obtained at T2 (P = .01) but still significantly poorer than what was recorded before bracket placement at T0 (P = .003). Statistically significant differences were found at all assessment times (T1, T2, and T3) between the two groups with regard to the mean upper boundary frequency values (Table 1).

Table 1.

Speech Evaluation Before Bracket Placement (T0), Immediately Following Bonding (T1), 1 Month after Bonding (T2), and 3 Months Post–Bracket Placement (T3) by Auditive Analysis of Spectrographsa

In group B and before bracket placement, the mean upper boundary frequency of the /s/ sound was 13,199 Hz (Table 1). A highly significant drop (P ≤ .001) was observed at T1, with a mean value of 12,686 Hz. The mean upper boundary frequency value arose significantly to 13,084 Hz at T2 and to 13,179 Hz at T3. The differences between T0-T2 and T0-T3 were statistically insignificant (Table 1).

Questionnaire Findings

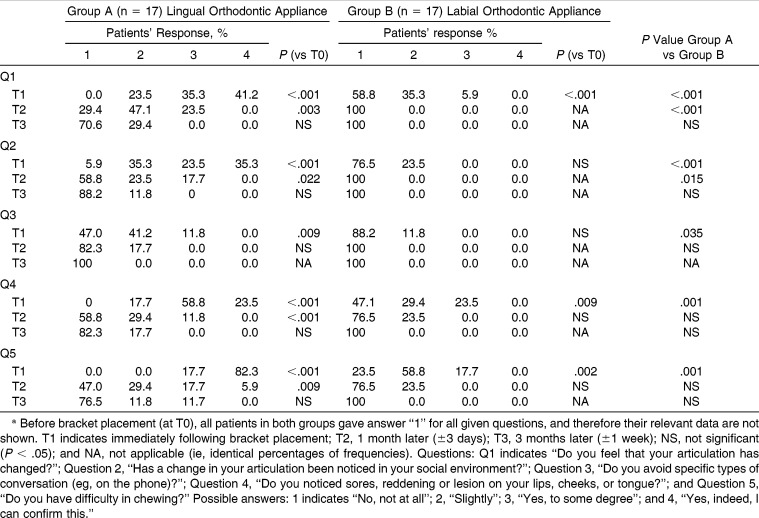

All of the answers in relation to the five questions given at T0 were identical (patients chose answer “no untoward effects”). Therefore, relevant data are omitted from Table 2, whereas responses at T1, T2, and T3 are presented.

Table 2.

Patient Responses on the Questionnaires Administered at Three Assessment Times Following Bracket Placement in the Two Groups (Group A: Lingual Brackets and Group B: Labial Brackets)a

Perception of Articulation Change (Question 1)

Immediately following bracket bonding (T1), patients in both groups reported a significant deterioration in their articulation, and a significant intergroup difference was observed (P < .001). One month later (at T2), all patients in group B reported that they were no longer perceiving a change in their speech, whereas 71% of group A patients had a mild to moderate perception of articulation change. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P < .001). Three months following appliance placement, moderate and severe articulation effects were not observed in either group.

Others' Observation of Articulation Change (Question 2)

Most patients (94.1%) in group A at T1 reported that their articulation change was noticed in their social environment to different degrees, whereas 24% of patients in group B had mild noticeable speech changes as reflected by others. The intergroup difference was statistically significant at T1 (P < .001) and significant at T2 (P = .015), but at T3, there were no significant differences between the two groups.

Avoidance of Some Types of Conversations (Question 3)

The only statistically significant difference between the two groups was observed immediately following appliance placement (P = .035), at which time 53% of patients in group A reported this trend of avoidance of certain types of conversations, in comparison with 11.8% of patients in group B.

Irritation to Soft Tissues (Question 4)

All patients (100%) in group A suffered from different degrees of irritation, compared to approximately 53% of patients in group B, who reported mild to moderate degrees of irritation at T1. The difference between the two groups was highly statistically significant (P < .001). The amount of irritation decreased at T2 and T3. The differences observed between the two groups were insignificant at T2 and T3.

Mastication Problems (Question 5)

Immediately following appliance placement, all patients (100%) in group A had moderate to severe mastication impairment, compared to 17.7% of patients in group B, who reported only moderate difficulties, and the difference between the two groups was highly significant (P < .001). There was an improvement in chewing abilities in both groups at the 1-month assessment, and approximately 24% of group A patients reported moderate to severe mastication problems, compared to none of the patients in group B. However, this difference was statistically insignificant. Finally, at T3, complete satisfaction with chewing in group B was observed, while this was not the case in group A.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first randomized, controlled trial to compare speech performance between lingual and labial fixed orthodontic treatment in a Syrian sample employing auditive analysis of spectrographic data of patients' speech supplemented by their subjective assessments of their articulation proficiency.

Patients in both groups showed a significant drop in the upper boundary frequency of the consonant /s/ sound directly after bracket bonding (T1). However, lingual brackets appeared to cause higher degrees of impairment in comparison to the labial brackets. The findings of consistent reduced levels of frequencies of the ‘s’ sound 1 and 3 months following bracket placement is in agreement with the findings of Hohoff et al.25 In another study,26 when upper incisors were tipped 30° palatally a similar reduction in the upper boundary frequency of the fricative ‘s’ sound was found. This indicates a similar pathomechanism, because the contact area of the tongue is also shifted further palatally by the lingual brackets.25

In our study, patients with lingual brackets showed more reduction in the upper boundary frequency of the /s/ sound than was recorded by Hohoff et al.25 This difference can be attributed to the type of lingual brackets used as well as the presence of the bite ramps in the current study. Hohoff et al.25 evaluated Ormco seventh-Generation brackets, which had rounded hooks, while the Stealth® brackets used in the current study had sharp hooks, which would have caused more irritation to the tongue and affected the production of the ‘s’ sound.

In the current study patients with labial brackets showed a statistically significant drop of the mean upper boundary frequency of the /s/ sound after bracket placement. Pain and tension following initial archwire engagement may change some oral habits and cause speech disturbances.27,28 After an adaptation period (which has been shown to be 2–3 weeks in a previous study27), the mean upper boundary frequency of the /s/ sound increased gradually at T2 and T3, with no significant differences when a comparison is made with the bottom-line data at T0.

The immediate speech impairment caused by labial appliances disappeared at the 1-month assessment, whereas patient complaints related to the lingual appliance persisted at 1 month and 3 months following the onset of treatment. These findings are generally in agreement with those of other previous studies.10–14,21 However, the intensity and overall duration of oral impairment are not similar in these studies, likely as a result of differences in study design, types of brackets, levels of tongue irritation, and the language employed. Speech difficulty was reported by a relatively high percentage (63.3%) of patients with labial appliances in a study conducted by Caniklioglu and Ozturk.21 However, these labial appliances were supplemented with several lingual auxiliaries, such as cleats and buttons, in addition to the use of transpalatal arches, which might explain their finding.

The amount of soft tissue discomfort was higher in the lingual appliance group. This finding does not agree with that of Caniklioglu and Ozturk,21 who reported the presence of tongue irritation in patients with labial appliances. This may be due to the same reasons mentioned above. The current study did not employ any lingual attachment in group B. Additionally, we used molar tubes that were bonded rather than molar bands that were cemented. Only three patients (17.6%) in the lingual appliance group had a persistent complaint of irritation and soreness in the tongue at the final assessment time. Miyawaki et al.29 reported that the feeling of irritation lasted for 3 months in some of their patients with lingual appliances, which is similar to our findings.

Mastication problems were observed in both groups but were significantly more common in the lingual group immediately following bracket placement. Perhaps irritation and pain caused by brackets and archwire engagement were beyond this problem with labial appliances. This finding is generally in agreement with the results of Fujita30 but contrasts with the findings of Caniklioglu and Ozturk21 and Wu et al.,14 who reported similar levels of eating difficulty between the two groups. This difference can be explained by the use of bite-blocks in the current study (rather than built-in bite-plane brackets) to raise the bite. Wiechmann et al.31 recorded lower levels of discomfort during eating when they used customized brackets (Incognito, TOP Service), in which brackets were bonded as close as possible to teeth surfaces and caused less oral discomfort compared to lingual brackets bonded with the BEST technique.

The results of the questionnaire-based analysis show that chewing difficulty was the most severe problem encountered by patients with lingual appliances, particularly in the immediate period following bracket placement. These findings do not concur with those of Caniklioglu and Ozturk21 and Wu et al.,14 who reported speech difficulty as the most serious problem with lingual appliances. Our findings also do not resemble those of Fillion12 and of Fritz et al.,13 who showed that tongue discomfort was the most common and severe problem in lingual patients. This may be due to the differences between the researched populations, study designs, types of brackets, samples' mean ages, types of questions used, assessment times, and the specific practical considerations during the treatment course.

CONCLUSIONS

Speech articulation was affected in both groups, but patients with lingual brackets had higher degrees of impairment. This was confirmed by both objective auditive analysis and subjective questionnaire-based analysis. Speech impairment seems to be a common consequence of any type of lingually bonded attachments in fixed orthodontic treatment.

Both types of appliances caused soft tissue irritation and chewing difficulty, but the lingual appliance group had significantly higher scores compared to the labial appliance group, particularly in the immediate postplacement phase.

Gradual improvements in oral impairment occurred during the first 3 months following insertion of lingual brackets, with the majority of lingual patients reporting satisfaction by the third assessment period.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gorman JC. Treatment of adults with lingual orthodontic appliances. Dent Clin North Am. 1988;32:589–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorman JC, Smith RJ. Comparison of treatment effects with labial and lingual fixed appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1991;99:202–209. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(91)70002-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grauer D, Proffit WR. Accuracy in tooth positioning with a fully customized lingual orthodontic appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140:433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pauls AH. Therapeutic accuracy of individualized brackets in lingual orthodontics. J Orofac Orthop. 2010;71:348–361. doi: 10.1007/s00056-010-1027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujita K. Multilingual bracket and mushroom arch wire technique. Am J Orthod. 1982;82:120–140. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90491-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly VM. Interviews on lingual orthodontics. J Clin Orthod. 1982;16:416–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander CM, Alexander R, Sinclair P. Lingual orthodontics: Part VI. J Clin Orthod. 1983;17:240–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marioti J. The Speech Effect of the Lingual Appliance [thesis] Rochester, NY: Eastman Dental Center; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith J, Gorman J, Kurz C, Dunn R. Keys to success in lingual therapy. Part 1. J Clin Orthod. 1986;20:252–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinclair PM, Cannito MF, Goates LJ, Solomos LF, Alexander CM. Patient responses to lingual appliances. J Clin Orthod. 1986;20:396–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Artun J. A post treatment evaluation of multibonded lingual appliances in orthodontics. Eur J Orthod. 1987;9:204–210. doi: 10.1093/ejo/9.3.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fillion D. Improving patient comfort with lingual brackets. J Clin Orthod. 1997;31:689–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fritz U, Diedrich P, Wiechmann D. Lingual technique—patients' characteristics, motivation and acceptance. J Orofac Orthop. 2002;63:227–233. doi: 10.1007/s00056-002-0124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu A, McGrath C, Wong RW, Wiechmann D, Rabie AB. Comparison of oral impacts experienced by patients treated with labial or customized lingual fixed orthodontic appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139:784–790. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngan P, Kess B, Willson S. Perception of discomfort by patients undergoing orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;96:47–53. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones M. An investigation into the initial discomfort caused by placement of an archwire. Eur J Orthod. 1984;6:48–54. doi: 10.1093/ejo/6.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White LW. Pain and cooperation in orthodontic treatment. J Clin Orthod. 1984;18:572–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones ML, Richmond S. Initial tooth movement: force application and pain—a relationship. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1985;88:111–116. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(85)90234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliver R, Knapman Y. Attitude to orthodontic treatment. Br J Orthod. 1985;12:179–188. doi: 10.1179/bjo.12.4.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willson S, Ngan P, Kess B. Time course of the discomfort in young patients undergoing orthodontic treatment. Paediatr Dent. 1989;11:107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caniklioglu C, Ozturk Y. Patient discomfort: a comparison between lingual and labial fixed appliances. Angle Orthod. 2005;75:86–91. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2005)075<0086:PDACBL>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caniklioglu C, Ozturk Y. Indirect bonding with TARG1TR system in lingual orthodontics: laboratory procedures. J Turk Orthod. 2003;16:71–81. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neppert J, Petursson M. Elemente Einer Akustischen Phonetik. Hamburg, Germany: Buske; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hohoff A, Seifert E, Ehmer U, Lamprecht-Dinnesen A. Articulation in children with Down's syndrome. J Orofac Orthop. 1998;59:220–228. doi: 10.1007/BF01579166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hohoff A, Seifert S, Fillion D, Stamm T, Heinecke A, Ehmer U. Speech performance in lingual orthodontic patients measured by sonagraphy and auditive analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;123:146–152. doi: 10.1067/mod.2003.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Runte C, Lawerino M, Dirksen D, Bollmann F, Lamprecht-Dinnesen A, Seifert E. The influence of maxillary central incisor position in complete dentures on /s/ sound production. J Prosthet Dent. 2001;85:485–495. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2001.114448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sergel HG, Klages U, Zentner A. Pain and discomfort during orthodontics treatment—causative factors and effects on compliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;114:684–691. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nanda RS, Kierl MJ. Prediction of co-operation in orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1992;102:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(92)70010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyawaki S, Yasuhara M, Koh Y. Discomfort caused by bonded lingual orthodontic appliances in adult patients as examined by a retrospective questionnaire. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;114:83–88. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(99)70320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujita K. Multilingual-bracket and mushroom arch wire technique. Am J Orthod. 1982;82:120–140. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90491-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiechmann D, Gerß J, Stamm T, Hohoff A. Prediction of oral discomfort and dysfunction in lingual orthodontics: a preliminary report. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]