Abstract

Objective:

To investigate patients' experiences with the Forsus Fatigue Resistant Device (FFRD).

Methods:

This was a survey focused on patient's comprehensive experience with FFRD, both initially and after several months of wear, including the patient's overall impression of the appliance. The survey was administered to 70 patients wearing FFRD in both university and private practice settings.

Results:

A high percentage (81.5%) reported a neutral to favorable experience with FFRD; 89.8% reported growing accustomed to the appliance within 4 weeks. The majority of those who had previously worn rubber bands found FFRD to be “easier.” Cheek irritation was the most serious side effect (about 50%). Cheek irritation and other negative effects generally decreased over time.

Conclusions:

The FFRD is relatively well accepted by patients. Most patients experience some discomfort and functional limitations; however, the effect generally diminishes with time, and patients adapt to the appliance. Practitioners should be especially vigilant about problems with cheek irritation.

Keywords: Orthodontics, Class II malocclusion, Fixed functional appliances

INTRODUCTION

Class II malocclusions have been described as the most frequent treatment problem in orthodontic practice, with 20% to 30% of children having Class II malocclusions, and as one of the more difficult orthodontic problems to treat.1,2 There are many different appliances available for Class II correction. One category of appliances frequently used, typically in growing patients, is the functional orthopedic appliance.3 They can be grouped into removable or fixed devices.4,5

The Forsus Fatigue Resistant Device (FFRD) is a fixed, hybrid functional appliance.4 As opposed to rigid, fixed functional devices, such as the Herbst appliance, the spring of the FFRD allows flexibility in the position of the mandible.4 It is considered a noncompliance device, as it is fixed in the patient's mouth and a practitioner does not have to rely on a patient's cooperation.3

There is limited research available on the effectiveness of FFRD appliances. Previous studies6,7 reported that using the FFRD is an effective technique in the management of patients with Class II malocclusion. Durability of an appliance is another important consideration when evaluating an orthodontic device and certainly plays a major role in a patient's experience. No quantification of FFRD failures could be found in the literature, except a case report8 indicating two breakage incidents.

Successful orthodontic treatment depends on patient acceptance of the orthodontic techniques being used. Orthodontists wish to minimize patient discomfort and maximize satisfaction during treatment. Evaluation of patient experiences during orthodontic treatment will allow clinicians to better select a modality of treatment that will be best accepted by their patients. Currently, there is no published data to assess patient experiences with the FFRD. Therefore, the overall aim of this study was to develop and implement a survey in order to assess a patient's experience with the FFRD. Clinicians using FFRD may find this information useful in preparing a patient who will be treated using FFRD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Informed consent was obtained from the subjects' parents, and assent was obtained from the subjects in accordance with the protocols of the University at Buffalo Children and Youth Institutional Review Board (DB #2501).

The subjects were selected from patients treated at the University at Buffalo Department of Orthodontics or in seven other western New York private orthodontic practices. The subjects varied in age from 12 to 18 years old. Subjects older than 18 years old were excluded, as the content of the survey was intended for school-age patients.

In order to be eligible to take the survey, the subjects had FFRD in place for at least 2 months, and the subjects still had the FFRD present in their mouth when they took the survey. Subjects were included regardless of whether the appliance was unilateral or bilateral and regardless of the location of the pushrod. Patients treated with or without extractions were included. Subjects were excluded if the FFRD was placed as part of the X-Bow appliance, which typically involves a palatal expander and a lower lingual holding arch in addition to the FFRD. No modifications were made in any of the providers' treatment plans in order to suit the study. Therefore, timing and specific protocol of the use of FFRD were not standardized.

After the child and their parents agreed to participate in the study, the survey was completed and the respondent was asked to seal it in a provided envelope and either hand it back to their provider at the time of their appointment or to mail it directly to the Orthodontic Department at the University at Buffalo. The survey was given confidentially, and no identifying information was included in the survey. The providers did not have access to their patients' responses. Participation was voluntary and there was no compensation.

The survey developed for this study (Appendix) was based on two existing surveys. One was the “Smiles Better” survey that was used in the research of O'Brien et al.9 comparing the Herbst and Twin Block appliances. Adjustments were made to suit an American audience as well as to shorten the survey to a length that would be less burdensome to patients and practitioners administering the survey in their office. Other aspects of the survey were based on a survey developed by Lisa Alvetro and David Solid. During informal prepilot sessions, the lead investigator questioned current and former FFRD patients about their experiences, and this led to the inclusion of certain items were not covered in the other surveys. There was no attempt to further validate this survey.

At the end of the data collection period, all responses were collected and subjected to statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics of all questions were calculated. Analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS; Version 18.0; IBM, Armonk, NY) for Windows.

RESULTS

Seventy-four surveys were collected. From them, four surveys were excluded from analysis due to the age of the respondent: three respondents were over age 18, and one did not specify age. A total of 40 females and 29 males responded. One 14-year-old respondent chose not to disclose his or her sex. The mean age was 14.5 ± 1.5 years.

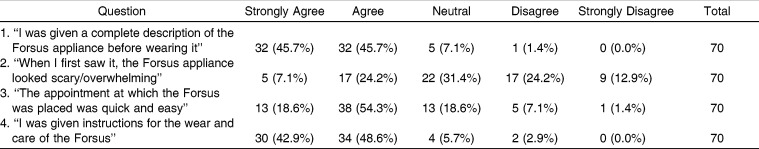

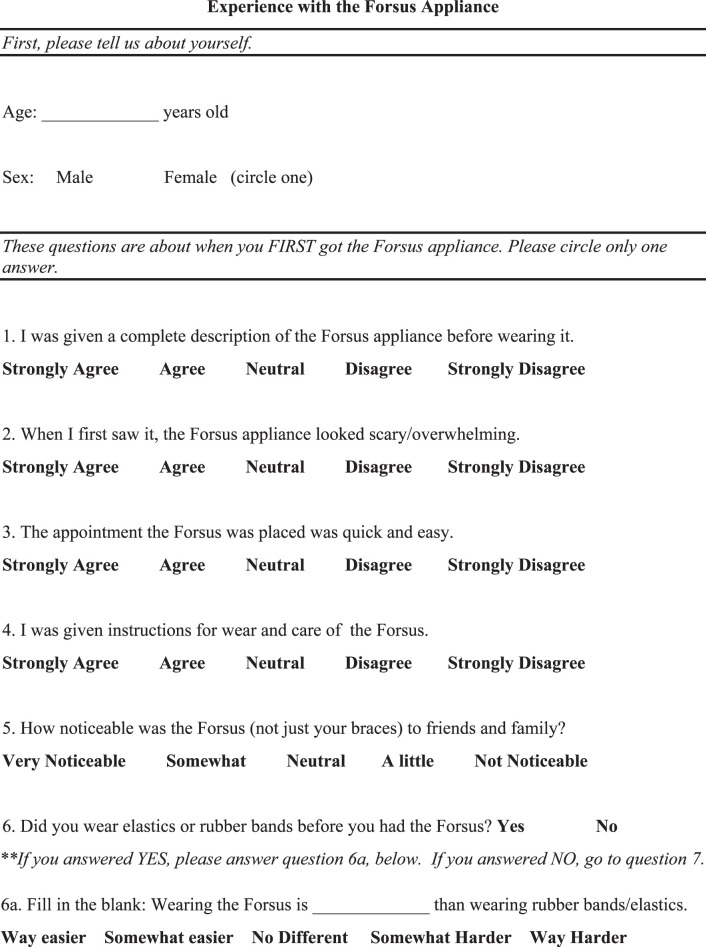

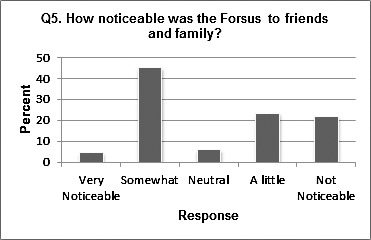

Table 1 shows the responses to questions 1 to 4. Most patients (91.4%) felt that they were given a complete description and usage instructions of the FFRD before wearing it. The majority of the patients (72.9%) found the placement of the FFRD to be quick and easy. Responses regarding “how noticeable FFRD was” appear to be normally distributed (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Responses to Questions 1 to 4

Figure 1.

Distribution of question 5.

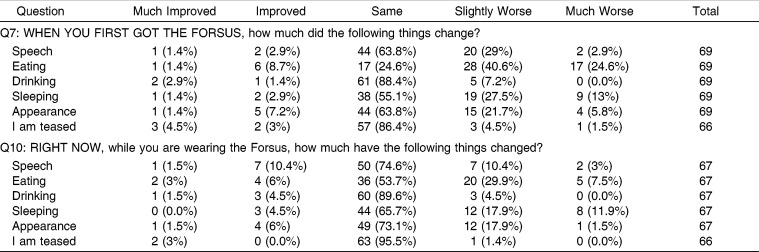

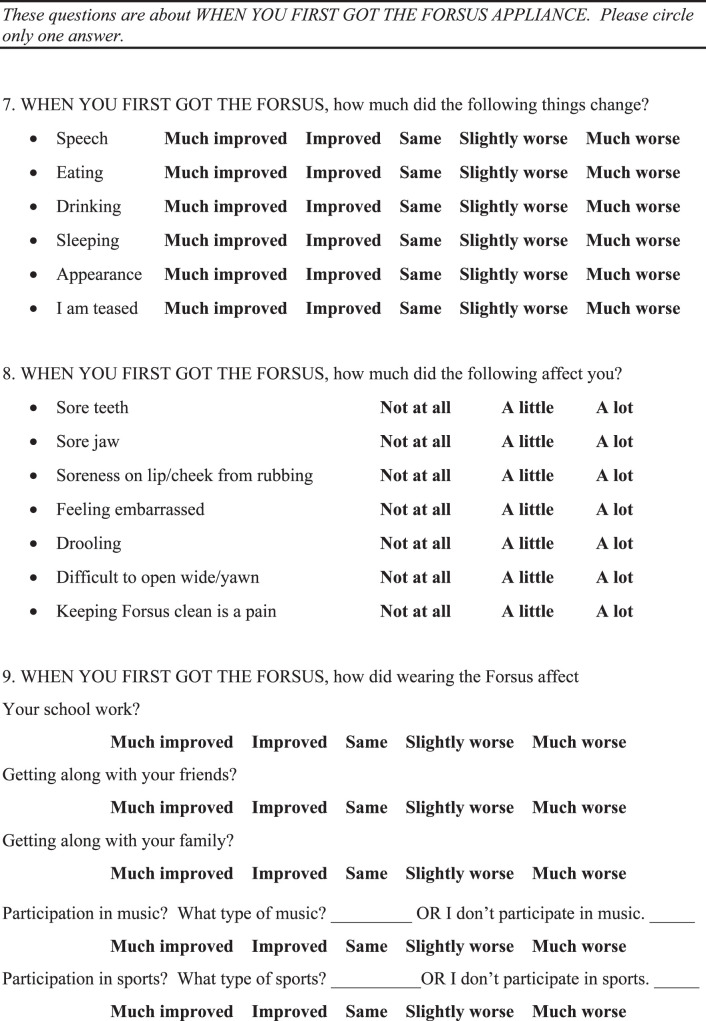

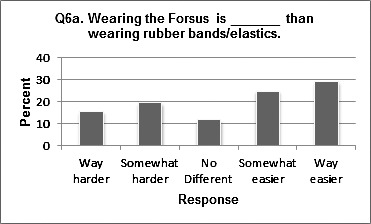

Fifty-one of the 70 respondents (72.9%) reported wearing Class II rubber bands prior to using FFRD and were able to answer a follow-up question comparing the two modalities of treatment. Responses varied, but favored the notion that wearing the FFRD appliance is easier than wearing elastics/rubber bands (Figure 2). Responses regarding the initial effects and the effects after at least 2 months of FFRD on certain functions (speech, eating, and sleeping) are shown in Table 2. They seemed to suffer the greatest initial negative impact, while drinking, appearance, and teasing did not seem to suffer as much.

Figure 2.

Distribution of question 6a.

Table 2.

Responses to Questions 7 and 10

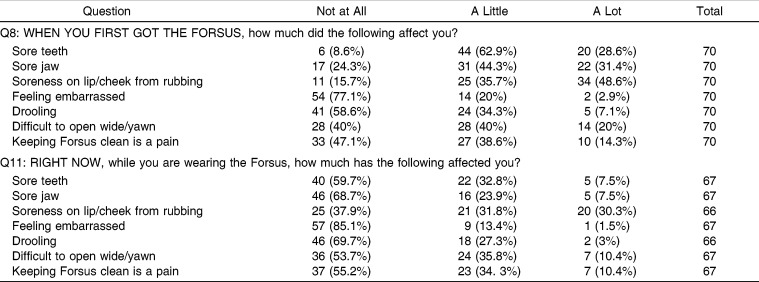

When asked about their experience with side effects when they first got the FFRD (Table 3), the majority of respondents reported being affected by (in descending order) sore teeth, soreness on lip/cheek from rubbing, sore jaw, difficulty opening wide, and difficulty in keeping FFRD clean. When asked to assess side effects after at least 2 months of use, only soreness on the lip/cheek from rubbing was significant.

Table 3.

Responses to Questions 8 and 11

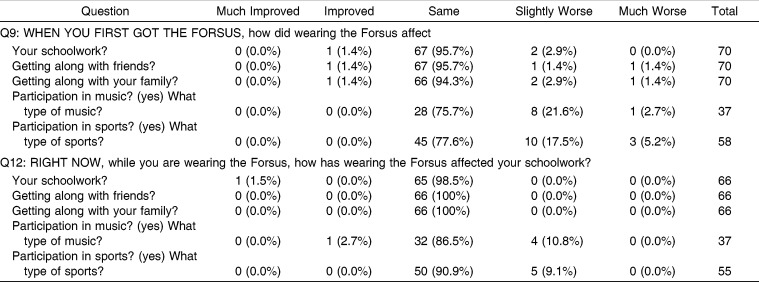

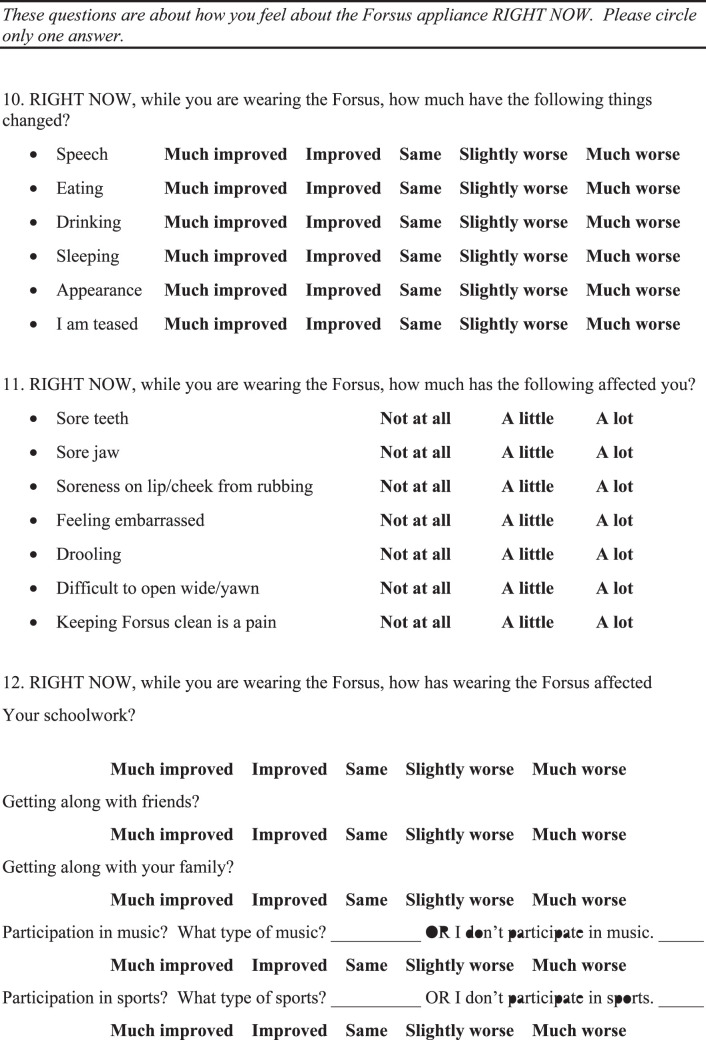

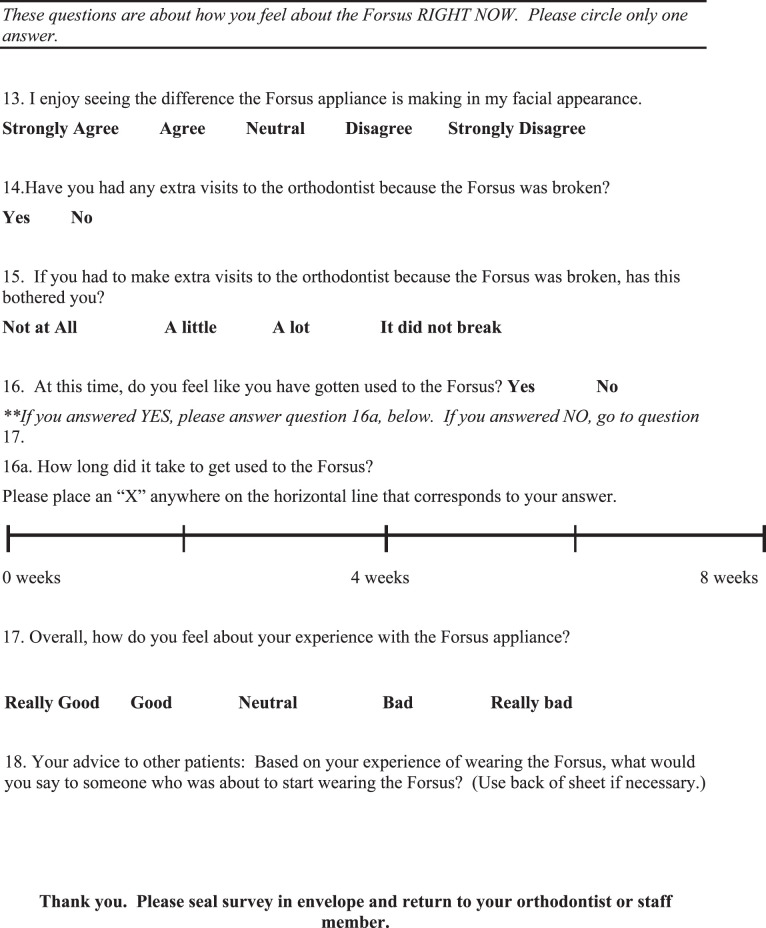

The survey also focused on how FFRD initially may have affected daily life, particularly relationships and activities. In most areas, such as schoolwork, getting along with friends, and getting along with family, FFRD initially had very little impact except for participation in music and sports, which suffered for some subjects (Table 4). When asked if they enjoyed seeing the difference FFRD was making in their facial appearance, most respondents (61.2%) agreed. Almost one third (29.9%) of respondents remained neutral on this question, while 9% disagreed that they enjoyed the difference in facial appearance that FFRD was making.

Table 4.

Responses to Questions 9 and 12

Breakage resulting in an extra trip to the orthodontist was reported by 25 subjects (37.3%). When the breakage resulted in an extra visit to the orthodontist, this bothered about half of the group, while the other half reported that this did not bother them at all.

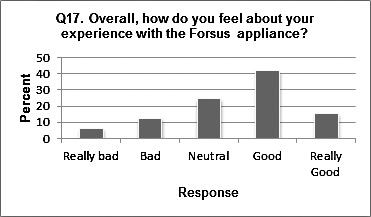

At the time that the survey was administered, which was at least 2 months into treatment with FFRD up until the day FFRD was removed, 87.9% reported that they had “gotten used to the FFRD.” Of those who reported that they had “gotten used to FFRD,” 66.1% reported that getting used to FFRD took up to 2 weeks, 23.7% reported that it took 2–4 weeks, 3.4% reported that it took 4–6 weeks, and 6.8% reported that it took 6–8 weeks. When asked to rate their overall experience with FFRD, most subjects reported positively (Figure 3): 15.4% felt “really good,” 41.5% felt “good,” 24.6% felt “neutral,” 12.3% felt “bad,” and 6.2% felt “really bad.”

Figure 3.

Distribution of question 17.

Question 18 was an open-ended question (58 responses). Subjects were asked to give advice to future FFRD patients. Answers were analyzed and categorized as “positive,” “neutral,” or “negative” in overall tone. Replies were also categorized by subject matter. Using this classification, 10% of the responses were positive, 78% were neutral, and the remaining 12% were negative. With respect to topics discussed, 31% of the replies related to accommodation to the appliance. The next most frequent subjects were brushing, cheek irritation, and discomfort, with 19% of the replies having something to do with one of these subjects.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated a patient's experience with the FFRD. The clinician who uses FFRD may find this information useful in preparing a patient who will be treated using FFRD.

Questions 1 through 4 dealt with the patients' initial experience with the FFRD. The vast majority of patients agreed that they were given a good description of the appliance, that the placement was quick and easy, and that they were provided with instructions for the care of the appliance. The varied responses to question 2 could be attributed to variability in patients, or it could be due to the different presentation styles of different providers.

For question 5, which dealt with how noticeable the subject felt the FFRD was, responses were varied. One variable that was not controlled or accounted for in the study design was the location of mandibular attachment of the FFRD. The pushrod can be attached distal to the canines or distal to the first premolars. If the appliance was placed further distally, it may have seemed less noticeable to the patient or less impeding on the cheeks. This variable should be controlled in future studies of the FFRD.

Regarding experience with Class II elastics, results were slightly less than what was found in Heinig and Goz's study,10 in which two thirds of respondents reported preferring the Forsus Nitinol Flat Spring Device (FNFD). It should be noted that in that study, patients were comparing the FNFD to a variety of Class II correctors, including headgear and activators as well as rubber bands. These findings may suggest that patients prefer noncompliance devices.

It is notable that although the group average indicates a downward trend in the experience of soreness on the lip or cheek from rubbing, when individual scores were compared, over 40% of individuals reported a worsening between the two time points. Presumably this is due to the development of ulcers subsequent to mechanical irritation. Practitioners should be aware of the worsening in lip and cheek irritation that tends to occur in some individuals, and they should be ready to manage this side effect.

The side effects, functional limitations, and impact on daily activities and relationships experienced by Forsus users have all been previously recorded in the literature with respect to other orthodontic appliances. In a study of fixed and removable appliances,11 it was found that discomfort, described as “tightness” and “sensitivity,” was the most frequently reported problem by the group in fixed appliances on the first day, with a mean score of 3 on a scale of 1 to 4. This is in agreement with the current Forsus study in that initial discomfort was the most frequently reported negative effect, more so than functional limitations. De Felippe et al.12 reported on problems with speech, chewing, and discomfort in patients with palatal expanders. Most (93.9%) respondents reported pain and discomfort associated with a palatal expander in the first few days of treatment. This is very similar to the rate of initial discomfort reported by patients with FFRD in this study. In De Felippe's study12, 89.4% reported that a palatal expander affected their speech, 90.2% reported it affected their chewing, and 67.9% reported that it affected swallowing, whereas in patients with FFRD, 13.4% of patients reported problems with speech, 65.2% reported problems with eating, and 41.4% reported problems with drooling. It seems that as compared to patients with palatal expanders, FFRD wearers experience a similar amount of discomfort but have fewer issues with speech and mastication. The lack of palatal coverage with an FFRD may contribute to the lesser effect on function as compared to a palatal expander.

Regarding the FNFS,10 difficulties were reported with yawning (62%), speech (8%), eating (8%), pain on the insides of the cheeks (38%), and difficulty in keeping the appliance clean (46%). No problems with teeth or jaw pain or difficulty sleeping were reported. With the exception of difficulty yawning, results with the FNFD differ greatly from this study's results with the FFRD, in which patients reported much higher rates of side effects and functional limitations. Thus, the experience of a patient with FFRD seems to have some similarities to the experience of patients with other orthodontic appliances as recorded by earlier studies.

In this study the group average of functional limitations, side effects, and impact on activities and relationships all decreased over time. This is in accordance with Stewart et al.,11 who also found similar decreases over time in patients wearing both fixed and removable appliances, and contrary to Mandall et al.,13 who did not observe diminishing effects over the course of three adjustment visits while patients were in fixed appliances.

In spite of the levels of side effects, both initially and present at the time of taking the survey, and the effects on function, both initial and those that lingered, 87.9% of respondents reported that they had gotten “used to FFRD” and 81.5% reported feeling positively or neutral about their overall experience with FFRD. This implies that orthodontic patients seem to accept a certain amount of discomfort and functional interference associated with their orthodontic treatment. This may also suggest that other factors play an important role in a patient's overall experience with an orthodontic appliance, such as relationship with the orthodontist, the value a patient places on orthodontic treatment, or a patient's general outlook on life. Stewart et al.11 suggest that patient attitude plays a role.

The breakage rate, which resulted in extra visits reported in this study, was seemingly much greater than that which was reported by Ross et al.8 Seventeen FFRD springs had been placed. Although they noted 10 incidents, eight incidents were lost split crimps. Although not specifically mentioned, a lost split crimp would most likely not result in an extra trip to the orthodontist, as the patient is not likely to find this particularly bothersome, if he or she notices it all. A 12% breakage rate can be extrapolated if the lost split crimps are not considered. In the current study, 38% of patients reported breakage that resulted in an extra visit. Since the current study included a university clinic and practitioners with varied levels of experience, inexperience may have contributed to the higher breakage rates. Further investigations might examine the breakage rate and mode of failure of the FFRD under controlled conditions.

It has been found11 that in patients with fixed appliances, most discomfort resolved within 4 to 7 days, while problems with speech and swallowing associated with the bulkier removable appliances persisted for up to 3 months. Problems with speech, chewing, and discomfort associated with palatal expanders resolved in about a week.12 Adaptation to discomfort occurs within 3–5 days, according to another author.14 The 2- to 4-week acclimation period with FFRD is somewhat longer than is reported in the literature for adaptation to pain but consistent with or shorter than reported times for functional adaptation. The wording of the FFRD survey question did not distinguish pain or function, so a respondent would likely take both into account when answering the question. This could explain the inconsistencies with adaptation to the FFRD appliance compared to reports in the literature.

Study Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

The results of this study provide a comprehensive understanding of the patient's overall experience with the FFRD; however, certain aspects of the study design could be improved for future studies. The design of this study introduced selection bias in that only patients who were able to maintain the FFRD for at least 2 months were asked to participate; therefore, patients who had to discontinue the appliance earlier for whatever reason were not included.

Also, the survey was given to patients in a private practice setting as well as a university clinic setting. The subjects were patients of numerous different doctors—some residents, some in practice over 20 years. The clinic setting, doctor, and clinician experience level could all be considered confounding factors in this study. Additionally, the results of this study could be strengthened with a larger sample size. Moreover, a significant percentage of the completed surveys included at least one missing or inappropriate response. This suggests that the survey might have been confusing or burdensome for some of the respondents. Shortening and simplifying the survey for future studies may result in more accurate responses. Finally, the survey should be tested for reliability and validity in order to draw general conclusions. With future research, we can gain further insight regarding a patient's experience with the FFRD and other orthodontic devices to better serve our patients.

CONCLUSIONS

The FFRD is relatively well accepted by patients.

Most patients experience some discomfort and functional limitations; however, the effect generally diminishes with time, and patients adapt to the appliance.

Practitioners should be especially vigilant about problems with cheek irritation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Lisa Alvetro and Dr Kevin O'Brien for their assistance in creating the survey for this study.

APPENDIX (Survey)

REFERENCES

- 1.McNamara J. Components of a Class II malocclusion in children 8–10 years of age. Angle Orthod. 1981;51:177–202. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1981)051<0177:COCIMI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Proffit W, Fields H, Moray L. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need in the United States: estimates from the NHANES III survey. Int J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg. 1998;13:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark W. Functional treatment objectives. In: Nanda R, Kapila S, editors. Current Therapy in Orthodontics. St Louis, Mo: Mosby Elsevier; 2010. pp. 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wahl N. Orthodontics in 3 millennia. Chapter 9: functional appliances to midcentury. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129:829–833. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dandajena T. Hybrid functional appliances for management of Class II malocclusions. In: Nanda R, Kapila S, editors. Current Therapy in Orthodontics. St Louis, Mo: Mosby Elsevier; 2010. pp. 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones G, Buschang P, Kim K, Oliver D. Class II non-extraction patients treated with the Forsus Fatigue Resistant Device versus intermaxillary elastics. Angle Orthod. 2008;78:332–338. doi: 10.2319/030607-115.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franchi L, Alvetro L, Giuntini V, Masucci C, Defraia E, Baccetti T. Effectiveness of comprehensive fixed appliance treatment used with the Forsus Fatigue Resistant Device in Class II patients. Angle Orthod. 2011;81:678–683. doi: 10.2319/102710-629.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross A, Gaffey B, Quick A. Breakages using a unilateral fixed functional appliance: a case report using The Forsus™ Fatigue Resistant Device. J Orthod. 2007;34:2–5. doi: 10.1179/146531207225021852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Brien K, Wright J, Conboy F, et al. Effectiveness of treatment for Class II malocclusion with the Herbst or Twin-block appliances: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;124:128–137. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(03)00345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinig N, Goz G. Clinical application and effects of the Forsus spring. A study of a new Herbst hybrid. J Orofac Orthop. 2001;62:436–450. doi: 10.1007/s00056-001-0053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart F, Kerr J, Taylor, P Appliance wear: the patient's point of view. Eur J Orthod. 1997;19:377–382. doi: 10.1093/ejo/19.4.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Felippe O, Silveira A, Viana G, Smith B. Influence of palatal expanders on oral comfort, speech and mastication. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandall N, Vine S, Hulland R, Worthington H. The impact of fixed orthodontic appliances on daily life. Comm Dent Health. 2006;23:69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sergl H, Klages U, Zentner Pain and discomfort during orthodontic treatment: causative factors and effects on compliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;114:684–691. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]