Abstract

Objective:

To test the hypothesis that malocclusion does not have an independent and negative effect on quality of life of adolescents.

Materials and Methods:

The cross-sectional design study comprised a sample of 519 children, aged 11 to 14 years, attending public schools in Osorio, a city in southern Brazil. One calibrated examiner carried out clinical examinations and recorded dental caries (decayed/missing/filled teeth), malocclusion (Dental Aesthetic Index), and dental trauma. Participants completed the Brazilian version of the Child Perceptions Questionnaire (CPQ11–14), Impact Short Form, and their parents or guardians answered questions about socioeconomic status. Simple and multivariate linear regressions were performed to assess covariates for the overall CPQ11–14 scores.

Results:

Greater impacts on oral health–related quality of life were observed for girls (P = .007), children with a lower household income (P = .016), those living in nonnuclear families (P < .001), and those with more decayed/missing/filled teeth (P = .001). Malocclusion was also associated with oral health–related quality of life: the severity of malocclusion was significantly related to higher scores of CPQ11–14 even after scores were adjusted for control variables. CPQ11–14 increased by approximately 1 point for each increase in the severity of malocclusion.

Conclusions:

Malocclusion has a negative effect on adolescents' quality of life, independent of dental caries or traumatic dental injuries. Socioeconomic inequalities and clinical conditions are important features in adolescents' quality of life.

Keywords: Oral health–related quality of life, Malocclusion, Adolescent

INTRODUCTION

Malocclusion can play an important role in social acceptance and interactions for esthetic reasons and can also result in functional limitations in more severe cases.1–4 Data from the most recent national oral health survey in Brazil demonstrate the presence of malocclusion in 38.8% of 12-year-old children.5 In such studies, the assessment of malocclusion is commonly conducted using predefined criteria such as the Dental Aesthetic Index (DAI).6 The DAI is an orthodontic index based on socially defined esthetic standards.7 It has been used in epidemiological studies of orthodontic treatment need, and it was integrated into the International Collaboration Study of Oral Health Outcomes by the World Health Organization (WHO).8 The index links clinical and esthetic components mathematically to produce a single score that reflects physical and esthetic patterns of occlusion, including patients' perceptions.9–11

A determination of oral health and treatment needs exclusively with normative indicators does not capture the full impact of oral abnormalities on a child's oral health.12 Over the last two decades, increasing attention has been paid to the assessment of oral health–related quality of life (OHRQoL) in oral health investigations.13–18 The Child Perceptions Questionnaire (CPQ) is one of the instruments that was developed specifically to assess the perception of adolescents on how oral health conditions impact them physically and psychologically.15 Previous studies confirmed the validity and reliability of its original and short versions for the Brazilian population.19–21

Although studies have been published associating DAI scores with patients' perceptions of treatment needs, there is scarce information regarding its association with measurements of OHRQoL and well-being using validated instruments.1,11,22,23 Recently it was found that 8- to 10-year-old schoolchildren with malocclusion experienced 30% more negative effects on OHRQoL than those without malocclusion.24 However, few studies have assessed the impact of malocclusion on OHRQoL and daily performance in adolescents, especially with regard to the possible confounding effects of other clinical and socioeconomic variables.25 This is important from a public health perspective, especially for a broader evaluation of treatment outcomes and for planning public health policies for prioritization of care.26

This study assessed and quantified the impact of malocclusion on OHRQoL in a representative sample of adolescents from Brazil. The study hypothesis is that adolescents (ages 11–14) with more severe forms of malocclusion will report higher scores on the Brazilian version of the CPQ – Impact Short Form than those without malocclusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study comprised 509 adolescents attending public schools in Osorio, a city in southern Brazil. The city has an estimated population of 40,000 inhabitants; 1996 of the 11- to 14-year-old children living in the city were enrolled in public schools in 2009, representing approximately 85% of the population of this age group living in the city. Students with previous or current experience with orthodontic or orthopedic treatment and those who were not intellectually capable of responding to the questionnaire were excluded from the study.

For the sample size calculation, we considered the following parameters: 5% standard error, 80% power, confidence level of 95%, and a mean CPQ11–14 score of 15.5 (± standard deviation [SD] 12.2) in the unexposed group (those without treatment needs, as defined by the DAI) and 20.5 (± SD 16.9) in the exposed group (those with treatment needs, as defined by the DAI).27 The ratio of exposed to unexposed was 3∶1, and a correction factor of 1.4 (effect design) was applied to increase precision. The minimum sample size to satisfy the requirements was estimated to be 498 children. Taking into consideration possible nonresponse attrition of 20% and the fact that 10% of adolescents have previous or current experience with orthodontic treatment, we determined that 700 adolescents should initially be assessed for eligibility.

To obtain a representative sample, a two-stage cluster sampling procedure was adopted, with all the public schools of Osorio considered as the primary survey unit. Five of the 12 schools were randomly selected after the schools were categorized as either large (n = 1 of 3), medium (n = 2 of 5), or small (n = 2 of 4).

The children's parents were mailed consent documentation and a questionnaire with items regarding socioeconomic and demographic data, time since last dental visit, and whether the child had received orthodontic treatment. After consent was obtained, the children completed the CPQ at school, and a dental examination was then performed.

Socioeconomic and Demographic Data

Socioeconomic characteristics were provided via a structured questionnaire that was completed by the child's parents or guardians. The questionnaire provided information on age, gender, ethnic group, family structure, the mother's educational level, and household income. The mother's educational level was measured in years of formal education; family structure compared those children living with both parents (nuclear) with those who lived with only one parent or neither of them (nonnuclear).

Household income was measured in terms of Brazilian minimum wage (BMW), which corresponded to approximately 240 US dollars per month. Regarding the variable “ethnic group,” children were classified by their parents as “white” (children of European descent) or “nonwhite” (black children of African and mixed descent). The feasibility of the questionnaire was assessed during the calibration process.

Oral Health–Related Quality of Life

OHRQoL was measured using the Brazilian version of the CPQ – Impact Short Form (ISF:16). The CPQ11–14/ISF:16 comprises 16 items distributed among four subscales: oral symptoms, functional limitations, emotional well-being, and social well-being. Each item addresses the frequency of events related to the teeth, lips, jaws, and mouth during the previous 3 months. Each question has five alternatives (never, once or twice, sometimes, often, almost every day, or every day), scaled from 0 to 4, with higher scores corresponding to poorer status. CPQ11–14 scores are obtained by summing the scores for each domain. For domains with up to two missing responses, a score for the missing items would be imputed as an average of the remaining items for that section. Questionnaires with missing responses to more than two items would be excluded from the analysis. The overall score ranges from 0 to 64; a higher score indicates that oral conditions have a greater negative impact on the child's QoL. The CPQ11–14 was adapted cross-culturally and has been validated for use in Brazilian children; it exhibits satisfactory psychometric properties.21 The CPQ11–14 was self-administered by each adolescent at his or her own school.

Clinical Data

One calibrated examiner carried out clinical examinations and recorded dental caries (decayed/missing/filled teeth [DMFT]), malocclusion (DAI), and dental trauma.28 The calibration process was performed prior to the survey in a group of 30 children, 11 to 14 years old. Theoretical and clinical training and calibration exercises were arranged for a total of 36 hours under the supervision of one benchmark examiner. The kappa values for intraexaminer reproducibility were 0.82, 0.92, and 1.00 for the DAI, DMFT, and traumatic dental injuries, respectively. The dental examination used international criteria standardized by the WHO for oral health surveys.6 The DAI includes 10 parameters of dentofacial anomalies related to both clinical and esthetic aspects: missing anterior teeth, midline diastema, incisal segment crowding, incisal segment spacing, largest anterior irregularity in the maxilla, largest anterior irregularity in the mandible, anterior maxillary overjet, anterior mandibular overjet, anterior open bite, and anteroposterior molar relation. The results were multiplied by the respective round coefficient (weight) and then summed; then, a constant value of 13 was added to the results.6 Four grades of malocclusion were established, with priorities and orthodontic treatment recommendations assigned to each grade:

Grade 1 (DAI ≤25): normal or minor malocclusion/no treatment needed,

Grade 2 (DAI 26–30): definite malocclusion/treatment is elective,

Grade 3 (DAI 31–35): severe malocclusion/treatment is highly desirable, and

Grade 4 (DAI ≥36): handicapping malocclusion/treatment is mandatory.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Descriptive, unadjusted analyses provided summary statistics assessing the association between the different levels of malocclusion and the overall and domain-specific CPQ11–14 scores using analysis of variance (ANOVA). The same test was performed to assess summary association between independent variables and the outcome. We also assessed the frequency of children with higher scores of CPQ11–14, with the 75th percentile of scores considered as the cutoff point. Statistical differences were then assessed by the chi-square test.

Simple and multivariate linear regressions were performed to assess covariates for the overall CPQ11–14 scores. A backward stepwise procedure was used to include or exclude explanatory variables in the fitting of the model. Explanatory variables were selected for the final models only if they had a P value ≤ .05 after adjustment.

Sensitivity analysis compared the sample subjects' ethnic groups and ages with those of all children enrolled in public schools of the city. These data were provided by the educational council of the City of Osorio. Selection bias was then assessed using chi-square tests and t-tests for independent samples.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Lutheran University of Brazil. Informed consent was obtained prior to beginning data collection.

RESULTS

A total of 705 adolescents, all 11 to 14 years old, were evaluated for their eligibility to participate in the study; 73 were already receiving orthodontic treatment and were therefore excluded. Of the 632 eligible adolescents, 80.5% agreed to participate (n = 509; 57.2% girls and 42.8% boys). All 509 participants answered the QoL questionnaire completely, with no missing responses. Adolescents were predominantly white (90.8%), more than half were from nuclear families (62.3%), and 70% had a household income equal or smaller than two BMW. The mother's level of formal education ranged from 0 to 16 years (mean, 6.9 ± 3.2 years). Of the 509 adolescents surveyed, 465 (91.4%) had already seen a dentist; of these, the time since the last dental visit ranged from 1 to 72 months (mean, 9.8 ± 10.8 months; median, 7 months).

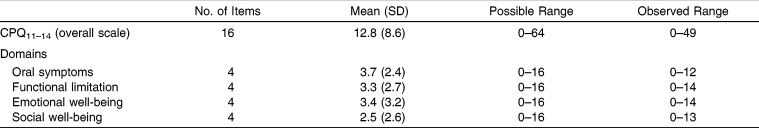

The overall scores of CPQ11–14 showed a normal distribution, with a mean score of 12.8 ± 8.6 and a median of 11 (25% = 6; 75% = 18). Domain-specific scores showed large variations; the highest mean score was for “oral symptoms” (3.7 ± 2.4) and the lowest was seen for “social well-being” (2.5 ± 2.6) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Distribution of Overall and Domain-Specific CPQ11–14

The DAI ranged from 15 to 77 (mean, 29.0 ± 7.9); 24% of the sample had minor or no malocclusion and 24% had definite malocclusion. Severe malocclusion and disabling malocclusion were seen in 21.6% and 22% of the sample, respectively.

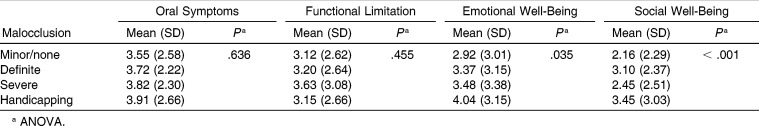

The overall and domain-specific scores of CPQ11–14 varied across the different categories of malocclusion. The severity of malocclusion was significantly associated with higher mean CPQ11–14 scores in the emotional and social well-being domains (Table 2). No significant differences were observed among the categories of malocclusion for the oral symptoms and functional limitation domains.

Table 2.

Descriptive Distribution of Domain-Specific CPQ11–14 Scores by Severity of Malocclusion

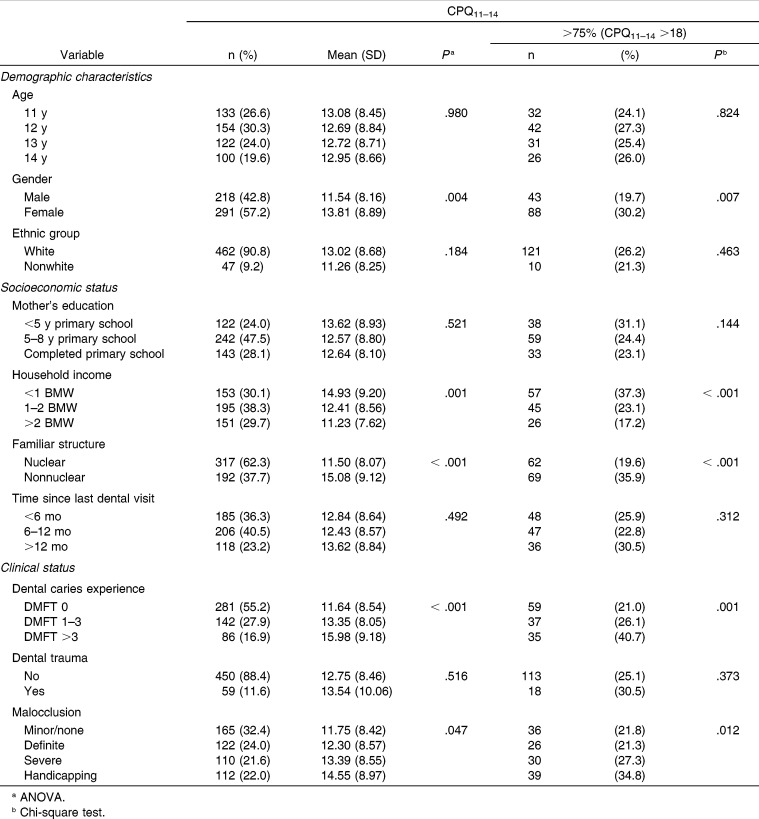

Unadjusted variables showed that CPQ11–14 scores were significantly higher for girls, lower household income, nonnuclear families, DMFT >3, and handicapping malocclusion (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sociodemographic Characteristics Related to Scores of CPQ11–14 (Median and 75th Quartile)

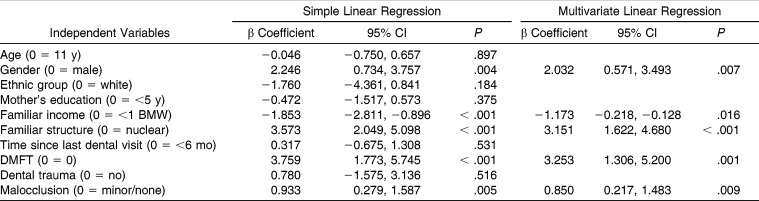

Following adjustment for confounding variables, higher impacts on OHRQoL were observed for adolescents living in nonnuclear families (P < .001), for girls (P = .007), for those with lower household income (P = .016), and for adolescents with DMFT >3 (P = .001). The severity of malocclusion was significantly associated with poorer scores of CPQ11–14, even after the adjustment; mean scores of CPQ11–14 increased by approximately 1 for each change in severity of malocclusion (β = .85; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.22–1.48) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Simple and Adjusted Linear Regression Analysis for the Severity of Impacts (CPQ11–14)

No difference was found between children included in the study and those who were not with regard to ethnic group (respondents: 90.8% white, 9.2% nonwhite; nonrespondents: 89.1% white, 10.9% nonwhite; P = .291) and mean age (respondents: 12.4 ± 1.0 years; nonrespondents: 12.3 ± 1.0 years; P = .293).

DISCUSSION

This study assessed the effect of malocclusion on OHRQoL. Our findings demonstrated that OHRQoL progressively deteriorates as the severity of malocclusion increases. Previous studies have also reported that adolescents with disturbances in dental occlusion experienced severe impacts on their QoL.2,4,16,25 However, few studies have assessed the relationship between OHRQoL and malocclusion using predefined criteria and taking into account potential confounding variables within a representative sample.

The role of dentofacial abnormalities in psychosocial well-being and QoL is well established. Theoretical explanations of the link between malocclusion and OHRQoL are based on the effect of this condition on dissatisfaction with self-image as well as on its impact on adolescents' daily performance.4,29 There is evidence that malocclusion can reduce chewing and speech capability, thus affecting an individual's perceptions of oral health.3,22,30 Nevertheless, the primary impact of malocclusion on the QoL has been reported as being in the domains of emotional and social well-being, which comprise issues related to esthetic components and self-esteem.1,14,16

In the present study, the association between increased malocclusion and CPQ11–14 scores was significant mainly for the domains of social and emotional well-being. Questions in this domain address adolescents' social relations, including avoidance of showing their teeth, laughing, and talking with other children at school or with people at home.31 Thus, a disturbance of normal occlusion may reduce social acceptance and induce low self-esteem and poor QoL by psychosocial pathways.14,32 Unesthetic occlusal traits may induce unfavorable social responses among adolescents, such as nicknames and teasing by schoolmates.33,34 Others have found that the presence of some occlusal traits is a significant indicator of self-reported bullying among adolescents.29 Taken together, these findings suggest that the impact of malocclusion on QoL is a result of psychosocial features, rather than oral or functional problems.35 Future studies should be conducted to investigate whether orthodontic treatment in patients with malocclusion can improve OHRQoL.

This study also confirmed the negative impact of dental clinical status and socioeconomic position on OHRQoL. It is well established that higher levels of dental disease are found in areas with a lower socioeconomic status.36,37 After adjusting for covariates, it was found that being female, living in a nonnuclear family with a low household income, and having a high DMFT index are significantly associated with high mean CPQ11–14 scores. Disadvantaged individuals are more likely to engage in deleterious behaviors that could affect their health.38 These results support previous studies that found that related socioeconomic inequalities and clinical conditions were important for OHRQoL.16,38

This study followed a cross-sectional design, and the temporal relationship between the outcome and predictors could not be defined. Nevertheless, the main exposure identified in this study as associated with OHRQoL—malocclusion—possibly preceded the outcome and cannot be considered to represent reverse-causality bias. Approximately 20% of the adolescents eligible for the study refused to participate. Nonrespondents may have exhibited characteristics associated with higher risks of different diseases. However, selection bias is unlikely to have occurred, since the sample subjects did not differ from the source population with regard to age or ethnic group.

CONCLUSIONS

Increased severity of malocclusion is associated with higher impact on OHRQoL, independent of dental caries or traumatic dental injuries.

Socioeconomic inequalities and clinical conditions represent important features of OHRQoL.

Sociodental measures may contribute to the identification of groups with higher levels of need, thus yielding a better cost-effectiveness ratio of oral health policies.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Paula DF, Jr, Santos NC, da Silva ET, Nunes MF, Leles CR. Psychosocial impact of dental esthetics on quality of life in adolescents. Angle Orthod. 2009;79:1188–1193. doi: 10.2319/082608-452R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marques LS, Ramos-Jorge ML, Paiva SM, Pordeus IA. Malocclusion: esthetic impact and quality of life among Brazilian schoolchildren. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129:424–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onyeaso CO, Aderinokun GA. The relationship between dental aesthetic index (DAI) and perceptions of aesthetics, function and speech amongst secondary school children in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2003;13:336–341. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2003.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peres KG, Barros AJ, Anselmi L, Peres MA, Barros FC. Does malocclusion influence the adolescent's satisfaction with appearance? A cross-sectional study nested in a Brazilian birth cohort. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36:137–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Projeto SBBrasil 2010 Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde Bucal Resultados Principais. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organisation (WHO) Oral Health Surveys Basic Methods 4th ed. Geneve: WHO; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jenny J, Cons NC, Kohout FJ, Jakobsen J. Predicting handicapping malocclusion using the Dental Aesthetic Index (DAI) Int Dent J. 1993;43:128–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organisation (WHO) International Collaboration Study of Oral Health Outcomes (ICS II) Document 2 Oral Data Collection and Examination Criteria. Geneve: WHO; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cons NC, Jenny J, Kohout FJ, Songpaisan Y, Jotikastira D. Utility of the dental aesthetic index in industrialized and developing countries. J Public Health Dent. 1989;49:163–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1989.tb02054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenny J, Cons NC. Establishing malocclusion severity levels on the Dental Aesthetic Index (DAI) scale. Aust Dent J. 1996;41:43–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1996.tb05654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamamci N, Basaran G, Uysal E. Dental Aesthetic Index scores and perception of personal dental appearance among Turkish university students. Eur J Orthod. 2009;31:168–173. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjn083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gherunpong S, Tsakos G, Sheiham A. Developing and evaluating an oral health-related quality of life index for children; the CHILD-OIDP. Community Dent Health. 2004;21:161–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbosa TS, Gaviao MB. Oral health-related quality of life in children: part II. Effects of clinical oral health status. A systematic review. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008;6:100–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster Page LA, Thomson WM, Jokovic A, Locker D. Validation of the Child Perceptions Questionnaire (CPQ 11–14) J Dent Res. 2005;84:649–652. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jokovic A, Locker D, Stephens M, Kenny D, Tompson B, Guyatt G. Validity and reliability of a questionnaire for measuring child oral-health-related quality of life. J Dent Res. 2002;81:459–463. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piovesan C, Antunes JL, Guedes RS, Ardenghi TM. Impact of socioeconomic and clinical factors on child oral health-related quality of life (COHRQoL) Qual Life Res. 2010;19:1359–1366. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9692-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vargas-Ferreira F, Piovesan C, Praetzel JR, Mendes FM, Allison PJ, Ardenghi TM. Tooth erosion with low severity does not impact child oral health-related quality of life. Caries Res. 2010;44:531–539. doi: 10.1159/000321447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Locker D, Allen F. What do measures of “oral health-related quality of life” measure. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:401–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goursand D, Paiva SM, Zarzar PM, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Child Perceptions Questionnaire 11–14 (CPQ11–14) for the Brazilian Portuguese language. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:2. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traebert J, de Lacerda JT, Thomson WM, Page LF, Locker D. Differential item functioning in a Brazilian-Portuguese version of the Child Perceptions Questionnaire (CPQ) Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010;38:129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torres CS, Paiva SM, Vale MP, et al. Psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the Child Perceptions Questionnaire (CPQ11–14) - short forms. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:43. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peres SH, Goya S, Cortellazzi KL, Ambrosano GM, Meneghim Mde C, Pereira AC. Self-perception and malocclusion and their relation to oral appearance and function. Cien Saude Colet. 2011;16:4059–4066. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232011001100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tessarollo FR, Feldens CA, Closs LQ. The impact of malocclusion on adolescents' dissatisfaction with dental appearance and oral functions. Angle Orthod. 2012;82:403–409. doi: 10.2319/031911-195.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sardenberg F, Martins MT, Bendo CB, et al. Malocclusion and oral health-related quality of life in Brazilian schoolchildren. Angle Orthod. 2012 May 21 doi: 10.2319/010912-20.1. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castro Rde A, Portela MC, Leao AT, de Vasconcellos MT. Oral health-related quality of life of 11- and 12-year-old public school children in Rio de Janeiro. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2011;39:336–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGrath C, Broder H, Wilson-Genderson M. Assessing the impact of oral health on the life quality of children: implications for research and practice. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:81–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foster Page LA, Thomson WM, Jokovic A, Locker D. Epidemiological evaluation of short-form versions of the Child Perception Questionnaire. Eur J Oral Sci. 2008;116:538–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2008.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andreasen J, Andreasen F, Andersson L. Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth 4th ed. Copenhagen: Munskgaard; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seehra J, Fleming PS, Newton T, DiBiase AT. Bullying in orthodontic patients and its relationship to malocclusion, self-esteem and oral health-related quality of life. J Orthod. 2011;38:247–256; quiz 294. doi: 10.1179/14653121141641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shue-Te Yeh M, Koochek AR, Vlaskalic V, Boyd R, Richmond S. The relationship of 2 professional occlusal indexes with patients' perceptions of aesthetics, function, speech, and orthodontic treatment need. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;118:421–428. doi: 10.1067/mod.2000.107008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piovesan C, Marquezan M, Kramer PF, Bonecker M, Ardenghi TM. Socioeconomic and clinical factors associated with caregivers' perceptions of children's oral health in Brazil. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2011;39:260–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Z, McGrath C, Hagg U. The impact of malocclusion/orthodontic treatment need on the quality of life. A systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2009;79:585–591. doi: 10.2319/042108-224.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernabe E, de Oliveira CM, Sheiham A. Condition-specific sociodental impacts attributed to different anterior occlusal traits in Brazilian adolescents. Eur J Oral Sci. 2007;115:473–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2007.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johal A, Cheung MY, Marcene W. The impact of two different malocclusion traits on quality of life. Br Dent J. 2007;202:E2. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antunes JL, Narvai PC, Nugent ZJ. Measuring inequalities in the distribution of dental caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:41–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piovesan C, Mendes FM, Antunes JL, Ardenghi TM. Inequalities in the distribution of dental caries among 12-year-old Brazilian schoolchildren. Braz Oral Res. 2011;25:69–75. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242011000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Locker D. Disparities in oral health-related quality of life in a population of Canadian children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:348–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davey-Smith G, Blane D, Bartley M. Explanations for socioeconomic differentials in mortality: evidence from Britain and elsewhere. Eur J Public Health. 1994;4:131–144. [Google Scholar]