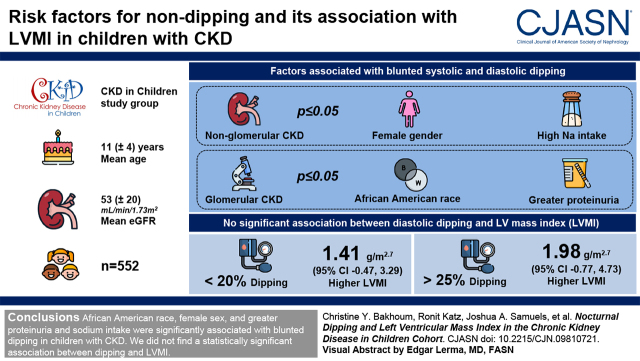

Visual Abstract

Keywords: ambulatory blood pressure, chronic kidney disease, pediatrics, nondipping, clinical epidemiology, blood pressure, cohort studies

Abstract

Background and objectives

The physiologic nocturnal BP decline is often blunted in patients with CKD; however, the consequences of BP nondipping in children are largely unknown. Our objective was to determine risk factors for nondipping and to investigate if nondipping is associated with higher left ventricular mass index in children with CKD.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of ambulatory BP monitoring and echocardiographic data in participants of the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children study. Multivariable linear and spline regression analyses were used to evaluate the relationship of risk factors with dipping and of dipping with left ventricular mass index.

Results

Within 552 participants, mean age was 11 (±4) years, mean eGFR was 53 (±20) ml/min per 1.73 m2, and 41% were classified as nondippers. In participants with nonglomerular CKD, female sex and higher sodium intake were significantly associated with less systolic and diastolic dipping (P≤0.05). In those with glomerular CKD, Black race and greater proteinuria were significantly associated with less systolic and diastolic dipping (P≤0.05). Systolic dipping and diastolic dipping were not significantly associated with left ventricular mass index; however, in spline regression plots, diastolic dipping appeared to have a nonlinear relationship with left ventricular mass index. As compared with diastolic dipping of 20%–25%, dipping of <20% was associated with 1.41-g/m2.7-higher left ventricular mass index (95% confidence interval, −0.47 to 3.29), and dipping of >25% was associated with 1.98-g/m2.7-higher left ventricular mass index (95% confidence interval, −0.77 to 4.73), although these relationships did not achieve statistical significance.

Conclusions

Black race, female sex, and greater proteinuria and sodium intake were significantly associated with blunted dipping in children with CKD. We did not find a statistically significant association between dipping and left ventricular mass index.

Podcast

This article contains a podcast at https://www.asn-online.org/media/podcast/CJASN/2021_12_20_CJN09810721.mp3

Introduction

Ambulatory BP monitoring has evolved as a valuable tool in the diagnosis and management of hypertension in children (1,2). Prior clinical trials evaluating different BP targets in children with CKD used ambulatory BP monitoring to define levels and guide treatment (3). The 2021 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines for persons with CKD now recommend the routine use of ambulatory BP monitoring in children with CKD (4). One of the significant benefits of ambulatory BP monitoring, as compared with casual or standardized BP measurements, is that it captures diurnal variations. BP normally declines by at least 10% from daytime to nighttime in children and adults (2,5). In adults, absence of this physiologic decline is associated with adverse clinical outcomes, including higher risk of cardiovascular disease and a more rapid decline in kidney function (6–11).

Prior data from the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children (CKiD) cohort, the largest study of children with CKD in North America, demonstrated that nondipping is prevalent in this population (12). However, the relationship of nondipping with markers of cardiovascular disease in this group is unknown. There are limited data, which suggest that nondipping is associated with worse cardiovascular and kidney outcomes in children with CKD. In a cross-sectional study of 29 children with CKD, lower systolic dipping was associated with lower eGFR (13). Another study of 46 children with stages 3–5 CKD demonstrated that a higher number of abnormal ambulatory BP monitoring indices (of which nondipping was a parameter) was associated with greater prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) (14). A few risk factors for nondipping in the pediatric population have been identified, including obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, and proteinuria; however, a more comprehensive evaluation of potential risk factors has not been conducted, and these prior studies were not designed to focus on children with CKD (15–17). We sought to characterize what the risk factors for nondipping are in children with CKD from within the CKiD cohort. We also tested our hypothesis that BP nondipping would be associated with greater left ventricular mass index (LVMI) in this population, independent of 24-hour mean systolic BP. Given that overt cardiovascular disease is not prevalent in children with CKD, subclinical markers, such as higher LVMI, become very important to identify early on in order to allow a focus on mitigation strategies. Although nondipping has been associated with greater LVH and higher LVMI in adults, the clinical consequences of nondipping in pediatric CKD remain generally unknown (6,7).

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Design

The study design and methods of the CKiD study have been previously described (18). Briefly, CKiD is a prospective, observational cohort study that recruited children 6 months to 16 years of age with Schwartz eGFR of 30–90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 from 59 different centers across North America. Three groups were recruited over specific time periods as follows: April 2005 to August 2009, February 2011 to March 2015, and October 2016 to September 2019 (19). The initial cohort was recruited on the basis of eGFR by the original Schwartz equation (20), and subsequent recruitment was made on the basis of the modified Schwartz equation (21). Exclusion criteria included history of dialysis within 3 months prior to recruitment; history of solid organ, bone marrow, or stem cell transplantation; malignancy; structural heart disease; and genetic syndromes involving the central nervous system, among others (18). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of each participating center and conducted in adherence with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Additionally, informed consent and age-appropriate assent were obtained from a parent or guardian and each participant, respectively. Our ancillary study was deemed exempt by the University of California San Diego and Yale University Institutional Review Boards.

This study is a cross-sectional analysis of baseline ambulatory BP monitoring and echocardiographic data from CKiD participants. We identified 552 participants with ambulatory BP monitoring and echocardiogram from the same study visit. Of these, 471 (85%) were obtained at visit 2, 49 (9%) were obtained at visit 4, 28 (5%) were obtained at visit 6, three (0.5%) were obtained at visit 8, and one (0.2%) was obtained at visit 14.

Casual Blood Pressure Measurement

The protocol for casual BP measurement in CKiD has been previously described (22). An aneroid sphygmomanometer (Mabis MedicKit 5; Mabis Healthcare, Waukegan, IL) was used to measure casual BP annually at each CKiD visit. After 5 minutes of rest, study personnel obtained auscultatory BP a total of three times, with 30-second intervals between measurements (22). The mean was calculated and then classified according to the 2017 American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical Practice Guideline (1).

Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring Protocol

Ambulatory BP monitoring was performed using SpaceLabs 90217 monitors (SpaceLabs Healthcare, Issaquah, WA), with BP measured every 20 minutes over a 24-hour period at a bleed step of 8 mm Hg (23). All data were analyzed centrally, as has been previously described (23).

The ambulatory BP monitoring study was deemed adequate if (1) it was worn for ≥21 hours with greater than or equal to one valid BP measured per hour for at least 18 hours and (2) it had greater than or equal to one successful BP recording in ≥75% of wake hours and ≥75% of sleep hours (23). For participants with an unsuccessful study, at least one repeat attempt was made. Nocturnal hypertension was defined as a nighttime systolic or diastolic mean BP ≥95th percentile for sex and height and/or a nighttime systolic or diastolic load ≥25% (23).

Dipping Calculations and Definitions

Systolic dipping and diastolic dipping were calculated as the percentage decrease in mean BP (either systolic or diastolic, respectively) from the average of measurements during the wake and sleep periods. Abnormal dipping pattern was defined as a decline of <10% in either systolic or diastolic dipping (2).

Echocardiography

Participating centers performed M-mode and Doppler echocardiography on each participant. For standardization, recordings were then read and analyzed by the Cardiovascular Core Imaging Research Laboratory at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (12).

Using two-dimensional directed M-mode echocardiography, left ventricular mass was measured according to the American Society of Echocardiography criteria (24). Left ventricular mass was then indexed to account for body surface area (mass was divided by height to a power of 2.7 or grams per meter2.7) (25). LVH was defined as LVMI≥95th percentile.

Other Variables

As part of the CKiD protocol, demographic and medical history included age, sex, body mass index (BMI) percentile, etiology of CKD, duration of CKD, self-reported race, birth weight, use of antihypertensive medications in the past 30 days (including categories of medication used), and total sodium intake (grams per day) calculated according to the 2013 Nutrition Data System software estimation (18). GFR was measured using plasma clearance of iohexol at baseline (26). Urine protein-creatinine ratio (UPCR) was measured annually in all participants. The CKiD central laboratory at the University of Rochester (Rochester, NY) performed all laboratory analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for participants with normal dipping pattern (“dippers”) and abnormal dipping pattern (“nondippers”). Continuous variables were described as mean ± SD. Categorical variables were described as frequency and percentage. UPCR (milligrams per milligram) was log2 transformed for normalization of the data.

We performed multivariable linear regression analyses to evaluate the relationship of various covariates with systolic and diastolic dipping (percentage). Variables that were deemed important to include in the models a priori were age, race, sex, BMI percentile, iohexol GFR, loop diuretic use, sodium intake (grams per day), birth weight (kilograms), and duration of CKD. Analyses were stratified by etiology of CKD (glomerular versus nonglomerular), given the potential for interaction between this variable and other important predictors in their effect on nocturnal dipping.

Next, we performed multivariable linear regression analyses to evaluate the relationship between systolic or diastolic dipping (percentage) and LVMI (grams per meter2.7). Variables identified as important to include in the models a priori were age, sex, race, BMI percentile, iohexol GFR, etiology of CKD, 24-hour mean systolic BP, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use, and duration of CKD. We then created unadjusted restricted cubic spline curves with knots placed at the quartiles to visualize the relationship between systolic and diastolic dipping (percentage) and LVMI (grams per meter2.7). On the basis of visualization of diastolic dipping in the spline curves, we created a categorical variable for diastolic dipping and evaluated its relationship with LVMI in a multivariable linear regression model with the same covariates as above.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 26 (Armonk, NY). Spline regression plots were generated using R version 4.0.3 (Vienna, Austria). A P value of 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 552 CKiD participants had ambulatory BP monitoring and echocardiographic data from the same visit and were included in this analysis. The mean age of the cohort was 11.1 years (SD of 4.1 years), with a mean eGFR of 53 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (SD of 20) (Table 1). Females (n=226) made up 41% of the cohort, and Black participants (n=69) made up 13% of the cohort (Table 1). The etiology of CKD in the cohort was nonglomerular disease in 73% of participants.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of Chronic Kidney Disease in Children study participants by dipping status

| Baseline Characteristic | Overall, n=552 | Dippers, n=327 | Nondippers, n=225 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at entry, yr | 11.1 (4.1) | 11.3 (4.0) | 10.8 (4.4) |

| Female | 226 (41) | 124 (38) | 102 (45) |

| Black | 69 (13) | 32 (10) | 37 (16) |

| Glomerular disease | 151 (27) | 85 (26) | 66 (29) |

| Birth weight, kg, n=520 | 3.11 (0.73) | 3.14 (0.71) | 3.10 (0.76) |

| Urine protein-creatinine, mg/mg,a n=538 | 0.32 (0.12–0.92) | 0.32 (0.11–0.85) | 0.33 (0.13–1.06) |

| LVMI, g/m2.7 | 30.9 (9.1) | 30.8 (9.3) | 30.9 (8.9) |

| BMI percentile, n=545 | 59.6 (30.7) | 60.7 (30.1) | 58.6 (31.6) |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 61 (11) | 36 (11) | 25 (11) |

| Carotid intima-medial thickness, mm, n=135 | 0.45 (0.26) | 0.43 (0.16) | 0.47 (0.34) |

| Total sodium intake, g/d,a n=469 | 3.0 (2.3–4.0) | 2.9 (2.3–4.0) | 3.0 (2.3–4.2) |

| Antihypertensive medication | 377 (68) | 224 (69) | 153 (68) |

| Loop diuretic use, n=514 | 12 (2) | 3 (1) | 9 (4) |

| Iohexol GFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2, n=500 | 51 (23) | 51 (22) | 50 (25) |

| Creatine-cystatin C–based eGFR | 53 (20) | 53 (20) | 53 (21) |

| Casual BP, n=535 | |||

| Normal BP | 348 (65) | 199 (63) | 149 (68) |

| Elevated BP | 71 (13) | 45 (14) | 26 (12) |

| Stage 1 hypertension | 92 (17) | 57 (18) | 35 (16) |

| Stage 2 hypertension | 24 (5) | 14 (5) | 10 (4) |

| Nocturnal hypertension | 283 (51) | 131 (40) | 152 (68) |

| Systolic dipping (%) | 10.8 (5.6) | 14.4 (3.3) | 5.6 (3.9) |

| Diastolic dipping (%) | 16.8 (7.3) | 20.7 (5.2) | 11.3 (6.3) |

For variables with missing data, n is provided. LVMI, left ventricular mass index; BMI, body mass index.

Median with interquartile range is reported as it is non-normally distributed.

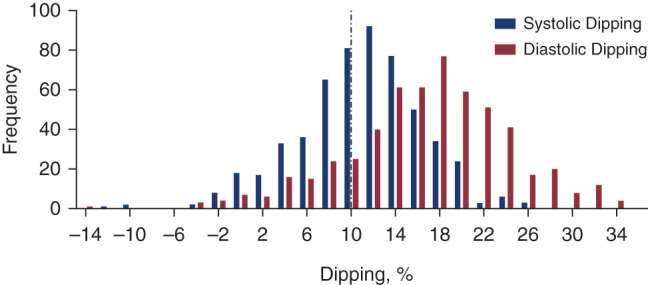

The mean systolic dipping in the overall cohort was 11% (SD of 6%), and the mean diastolic dipping was 17% (SD of 7%). The systolic and diastolic dipping distributions are presented in Figure 1. Of the 552 participants, 225 (41%) were nondippers. Of these, 86 (38%) had both systolic and diastolic nondipping, 133 (59%) had isolated systolic nondipping, and six (3%) had isolated diastolic nondipping. Within nondippers, 152 (68%) were also classified as having nocturnal hypertension (Table 1).

Figure 1.

The distribution of nocturnal BP dipping in Chronic Kidney Disease in Children participants. Systolic dipping (percentage) is displayed in blue. Diastolic dipping (percentage) is displayed in red.

Determinants of Systolic and Diastolic Dipping

Table 2 describes the multivariable linear regression models for systolic and diastolic dipping (percentage) in participants with nonglomerular CKD. Female sex was associated with lower (or blunted) systolic dipping by 2% (95% confidence interval [95% CI], −3.24 to −0.56) and lower diastolic dipping by 2% (95% CI, −3.68 to −0.21) (Table 2). A 1-g/d-higher sodium intake, on the basis of food frequency questionnaires, was associated with lower systolic dipping by 0.22% (95% CI, −0.36 to −0.07) and lower diastolic dipping by 0.26% (95% CI, −0.46 to −0.07) (Table 2). For diastolic dipping, 1-year older age was associated with higher dipping by 0.38% (95% CI, 0.00 to 0.75) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable analysis of risk factors associated with systolic and diastolic dipping (percentage) in children with nonglomerular CKD

| Variable | Estimatea (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Systolic dipping | ||

| Log2 (UPCR) | −0.12 (–0.51 to 0.27) | 0.54 |

| Black | −1.45 (–3.75 to 0.85) | 0.22 |

| Femaleb | −1.90 (–3.24 to –0.56) | 0.01b |

| Age, per yr | 0.23 (–0.06 to 0.52) | 0.11 |

| BMI percentile, per 1% | 0.002 (–0.02 to 0.02) | 0.83 |

| Iohexol GFR, per ml/min per 1.73 m2 | −0.02 (–0.05 to 0.02) | 0.44 |

| Loop diuretic use | −2.44 (–8.56 to 3.69) | 0.44 |

| Total sodium intake, per g/db | −0.22 (–0.36 to –0.07) | 0.01b |

| Birth weight, per 1 kg | −0.02 (–0.94 to 0.90) | 0.96 |

| CKD duration, per yr | −0.05 (–0.32 to 0.23) | 0.75 |

| Diastolic dipping | ||

| Log2 (UPCR) | −0.37 (–0.88 to 0.13) | 0.15 |

| Black | −1.15 (–4.13 to 1.82) | 0.45 |

| Femaleb | −1.94 (–3.68 to –0.21) | 0.03b |

| Age, per yrb | 0.38 (0.00 to 0.75) | 0.05b |

| BMI percentile, per 1% | 0.01 (–0.02 to 0.04) | 0.47 |

| Iohexol GFR, per ml/min per 1.73 m2 | −0.01 (–0.06 to 0.04) | 0.64 |

| Loop diuretic use | −4.09 (–12.01 to 3.83) | 0.31 |

| Total sodium intake, per g/db | −0.26 (–0.46 to –0.07) | 0.01b |

| Birth weight, per 1 kg | −0.36 (–1.55 to 0.83) | 0.55 |

| CKD duration, per yr | 0.02 (–0.34 to 0.37) | 0.92 |

UPCR, urine protein-creatinine ratio (milligrams per milligram); BMI, body mass index.

n=365 due to missing covariates.

Variable with P value achieving statistical significance.

Table 3 describes the multivariable linear regression models for systolic and diastolic dipping (percentage) in participants with glomerular CKD. A two-fold–higher UPCR was associated with lower systolic dipping by 0.62% (95% CI, −1.24 to 0.00) and lower diastolic dipping by 0.77% (95% CI, −1.54 to −0.00) (Table 3). Black race was associated with lower systolic dipping by 5% (95% CI, −8.88 to −1.34) and lower diastolic dipping by 7% (95% CI, −12.0 to −2.63) (Table 3). Additionally, for diastolic dipping, one–percentile point–higher BMI was associated with higher dipping by 0.07% (95% CI, 0.01 to 0.13), and loop diuretic use was associated with lower dipping by 6% (95% CI, −12.2 to −0.45) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of risk factors associated with systolic and diastolic dipping (percentage) in children with glomerular CKD

| Variable | Estimatea (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Systolic dipping | ||

| Log2 (UPCR)b | −0.62 (–1.24 to 0.00) | 0.05b |

| Blackb | −5.11 (–8.88 to –1.34) | 0.01b |

| Female | −0.57 (–2.13 to 3.26) | 0.68 |

| Age, per yr | −0.21 (–0.62 to 0.21) | 0.33 |

| BMI percentile, per 1% | 0.05 (0.00 to 0.10) | 0.05 |

| Iohexol GFR, per ml/min per 1.73 m2 | −0.01 (–0.06 to 0.04) | 0.71 |

| Loop diuretic use | −4.19 (–8.91 to 0.52) | 0.08 |

| Total sodium intake, per g/d | 0.18 (–0.43 to 0.79) | 0.57 |

| Birth weight, per 1 kg | −1.83 (–3.91 to 0.25) | 0.08 |

| CKD duration, per yr | −0.08 (–0.40 to 0.24) | 0.63 |

| Diastolic dipping | ||

| Log2 (UPCR)b | −0.77 (–1.54 to –0.00) | 0.05b |

| Blackb | −7.32 (–12.0 to –2.63) | 0.003b |

| Female | 0.24 (–3.11 to 3.59) | 0.89 |

| Age, per yr | −0.36 (–0.87 to 0.16) | 0.17 |

| BMI percentile, per 1%b | 0.07 (0.01 to 0.13) | 0.03b |

| Iohexol GFR, per ml/min per 1.73 m2 | −0.001 (–0.06 to 0.06) | 0.99 |

| Loop diuretic useb | −6.31 (–12.2 to –0.45) | 0.04b |

| Total sodium intake, per g/d | 0.26 (–0.50 to 1.02) | 0.50 |

| Birth weight, per 1 kg | −1.67 (–4.25 to 0.92) | 0.20 |

| CKD duration, per yr | 0.02 (–0.37 to 0.42) | 0.90 |

UPCR, urine protein-creatinine ratio (milligrams per milligram); BMI, body mass index.

n=91 due to missing covariates.

Variable with P value achieving statistical significance.

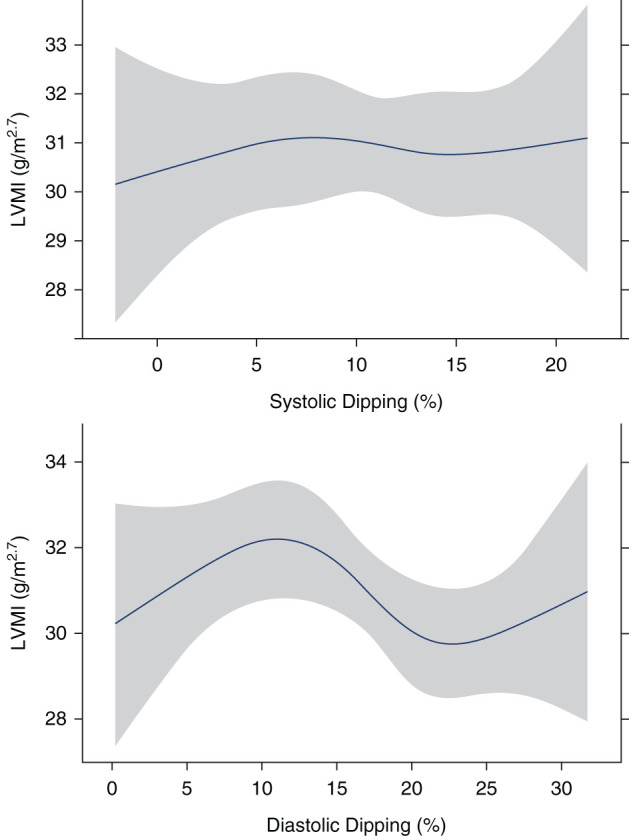

The Relationship of Systolic and Diastolic Dipping Percentage with Left Ventricular Mass Index

In multivariable models, one–percentage point–greater diastolic dipping was associated with 0.01 g/m2.7 (−0.11, 0.10) lower LVMI (Table 4), and one–percentage point–greater systolic dipping was associated with 0.05 g/m2.7 (−0.09, 0.19) higher LVMI (Table 4). Black race, younger age, higher BMI percentile, and lower iohexol GFR were significantly associated with higher LVMI (Table 4). The unadjusted spline regression plots for the relationship of systolic and diastolic dipping percentages with LVMI are presented in Figure 2. Overall, we did not find a statistically significant association between systolic dipping percentage and LVMI (Figure 2). Diastolic dipping appeared to have a nonlinear relationship with LVMI, where LVMI appeared to be lowest around diastolic dipping of 20%–25% (Figure 2). On the basis of the visualized spline curves, in an exploratory analysis, we evaluated the relationship of diastolic dipping as a categorical variable (<20%, 20%–25%, and >25%) with LVMI. In this multivariable analysis with diastolic dipping of 20%–25% as the reference group, we identified that diastolic dipping of <20% was associated with 1.41-g/m2.7-higher LVMI (95% CI, −0.47 to 3.29) and that diastolic dipping of >25% was associated with 1.98-g/m2.7-higher LVMI (95% CI, −0.77 to 4.73) (Table 5). These relationships, however, did not achieve statistical significance (P=0.14 and P=0.16, respectively) with adjustment for 24-hour mean systolic BP.

Table 4.

Association of systolic and diastolic dipping (percentage) with left ventricular mass index (grams per meter2.7)

| Variable | Estimatea (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Systolic dipping, % | 0.05 (–0.09 to 0.19) | 0.47 |

| Black | 2.41 (0.03 to 4.78) | 0.05b |

| Female | −0.22 (–1.81 to 1.37) | 0.79 |

| Age, per yr | −0.62 (–0.91 to –0.34) | <0.001b |

| BMI percentile, per 1% | 0.07 (0.04 to 0.09) | <0.001b |

| Iohexol GFR, per ml/min per 1.73 m2 | −0.11 (–0.14 to –0.07) | <0.001b |

| Glomerular disease | 1.88 (–0.66 to 4.41) | 0.15 |

| 24-h mean systolic BP | 0.07 (–0.00 to 0.15) | 0.06 |

| ACEi use | −1.26 (–2.83 to 0.32) | 0.12 |

| CKD duration, per yr | −0.03 (–0.28 to 0.22) | 0.81 |

| Diastolic dipping, % | −0.01 (–0.11 to 0.10) | 0.90 |

| Black | 2.29 (–0.10 to 4.68) | 0.06 |

| Female | −0.34 (–1.93 to 1.25) | 0.67 |

| Age, per yr | −0.61 (–0.90 to –0.33) | <0.001b |

| BMI percentile, per 1% | 0.07 (0.04 to 0.09) | <0.001b |

| Iohexol GFR, per ml/min per 1.73 m2 | −0.11 (–0.14 to –0.07) | <0.001b |

| Glomerular disease | 1.84 (–0.69 to 4.38) | 0.15 |

| 24-h mean systolic BP | 0.07 (–0.01 to 0.14) | 0.09 |

| ACEi use | −1.25 (–2.82 to 0.33) | 0.12 |

| CKD duration, per yr | −0.03 (–0.28 to 0.22) | 0.82 |

BMI, body mass index; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.

n=488 due to missing covariates.

Variable with P value achieving statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Unadjusted spline curves demonstrating the relationship of nocturnal BP dipping with left ventricular mass index in participants of the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children cohort. The relationship between systolic dipping (percentage) and left ventricular mass index (LVMI; grams per meter2.7) is shown in the top panel. The relationship between diastolic dipping (percentage) with LVMI (grams per meter2.7) is shown in the bottom panel.

Table 5.

Association of diastolic dipping as a categorical variable with left ventricular mass index (grams per meter2.7)

| Variable | Estimatea (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Diastolic dipping <20% | 1.41 (–0.47 to 3.29) | 0.14 |

| Diastolic dipping >25% | 1.98 (–0.77 to 4.73) | 0.16 |

| Black | 2.38 (0.01 to 4.75) | 0.05b |

| Female | −0.43 (–2.0 to 1.14) | 0.59 |

| Age, per yr | −0.61 (–0.89 to –0.32) | <0.001b |

| BMI percentile, per 1% | 0.07 (0.04 to 0.09) | <0.001b |

| Iohexol GFR, per ml/min per 1.73 m2 | −0.11 (–0.14 to –0.07) | <0.001b |

| Glomerular disease | 1.73 (–0.80 to 4.27) | 0.18 |

| 24-h mean systolic BP | 0.06 (–0.01 to 0.14) | 0.10 |

| ACEi use | −1.17 (–2.74 to 0.41) | 0.15 |

| CKD duration, per yr | −0.04 (–0.29 to 0.21) | 0.75 |

Reference group is diastolic dipping of 20%–25%. BMI, body mass index; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.

n=488 due to missing covariates.

Variable with P value achieving statistical significance.

Discussion

In a large, diverse cohort of children with CKD, we comprehensively evaluated risk factors for dipping using ambulatory BP monitoring. We found that predictors of dipping differ by etiology of CKD. In those with nonglomerular CKD, female sex and greater sodium intake are each independently associated with blunted systolic and diastolic dipping. In those with glomerular CKD, greater proteinuria and Black race are both independently associated with lower systolic and diastolic dipping. Contrary to data in adults and contrary to our a priori hypothesis, we did not observe associations of systolic and diastolic dipping with LVMI in linear regression models. However, on the basis of spline regression analyses, those with diastolic dipping in the range of 20%–25% appeared to have lower LVMI as compared with those with dipping outside of this range, although this was not statistically significant. Additionally, similar to what was identified in a prior CKiD study, we found that Black race, younger age, higher BMI percentile, and lower iohexol GFR were significantly associated with higher LVMI (27).

Children with CKD are at high risk for mortality secondary to cardiovascular disease in adulthood (28). Thus, identifying potential risk factors for worsening cardiovascular disease in this population is of paramount importance. Blunted nocturnal BP dipping is significantly associated with LVH and larger LVMI in adults (6,7,10,11). In children, the data regarding the relationship of nocturnal BP with markers of cardiovascular remodeling are much more limited. In a study of 24 children on dialysis, those with LVH had significantly lower nocturnal dipping as compared with those without LVH (29). However, in a single-center, retrospective study of 114 children with hypertension excluding those with kidney failure, nondipping was not significantly associated with higher LVMI or LVH (30). This study is, therefore, much larger and evaluated 552 children with CKD from across North America. The general absence of a relationship of dipping with LVMI in linear models raises questions around the utility in using dipping percentage as an early risk factor for cardiovascular disease in children with CKD. Future studies are needed to interrogate different thresholds for defining systolic and diastolic nondipping in pediatric populations and to evaluate their relationship with other important outcomes in children with CKD.

Different mechanisms have been implicated in the pathophysiology of blunted nocturnal dipping (31). Of particular interest is the role of sodium intake and kidney sodium excretion. Higher sodium intake in adults has been associated with impaired nocturnal dipping, and a reduction in sodium intake has been shown to improve BP dipping (32,33). The pressure-natriuresis hypothesis may be the link between sodium and dipping patterns, with the concept that nondippers are inefficient daytime excreters of sodium and have a compensatory rise in nocturnal BP to enhance nocturnal natriuresis (34,35). Consistent with this, our study found that higher sodium intake was significantly associated with blunted nocturnal dipping in children with nonglomerular CKD. It is interesting that we did not find this association in those with glomerular disease. We hypothesize that this may be because those with glomerular disease are more likely to be on tightly restricted sodium diets. Additionally, we identified that loop diuretic use was significantly associated with blunted diastolic dipping in children with glomerular CKD, although we interpret this with caution given the limited number of children in this study who reported its use. We hypothesize that those children on loop diuretics likely have impaired daytime sodium and water excretion leading to volume overload and compensatory elevated nocturnal BP. Also, consistent with prior literature, we found that greater proteinuria is associated with blunted dipping in children with glomerular CKD, again possibly the result of the effect of the proteinuric state on sodium handling by the kidney (16). Finally, in line with studies in adults, we also identified that Black race was significantly associated with blunted nocturnal dipping in children with glomerular CKD (36,37). Further studies in children are needed to determine whether these racial differences are related to environmental factors, diet, genetic differences, or a combination of these (38).

This study has important limitations. First, it is cross-sectional, and thus, we cannot infer the direction of relationships between dipping and LVMI. Future studies evaluating serial ambulatory BP monitoring and echocardiograms are needed to make further conclusions. Second, the pediatric CKD population we studied is heterogeneous as far as etiology of CKD, and there may be differences in kidney sodium handling and dipping patterns by disease. Although we stratified by CKD etiology in the analysis of predictors of dipping and adjusted for CKD etiology in the analysis of predictors of LVMI, future studies are needed to establish whether dipping patterns and their association with outcomes vary on the basis of specific CKD pathologies. Third, dietary sodium intake was estimated on the basis of food frequency questionnaires, as 24-hour urine sodium excretion data are not available in this cohort (39). Fourth, dipping pattern is one of the less reproducible measures on ambulatory BP monitoring in children (40). Thus, one test is likely not sufficiently reliable to characterize dipping profile, and future studies with serial ambulatory BP monitoring are needed to confirm our findings. Finally, a majority of children in this study self-identified as White, thus limiting generalizability of our findings to other racial and ethnic groups.

In conclusion, among a large cohort of children with CKD living in North America, we demonstrate that Black race, female sex, and greater proteinuria and sodium intake are each independently associated with blunted systolic and diastolic nocturnal BP dipping. Importantly, we determined that systolic and diastolic dipping were not associated with LVMI; however, there was a nonlinear relationship between diastolic dipping and LVMI. Given these findings, further studies are needed to investigate thresholds for defining nondipping and to evaluate its association with other important pediatric CKD outcomes.

Disclosures

T. Al-Rousan reports receiving research funding from National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant HL148530. P.S. Garimella reports receiving honoraria from DCI, serving as an associate editor for BMC Nephrology and an editorial board member for Kidney Medicine, and serving on the speakers bureau for Otsuka. P.S. Garimella's spouse reports ownership interest in Fitbit Inc. J.H. Ix reports employment with Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System; consultancy agreements with Ardelyx, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Jnana, and Sanifit; receiving research funding from Baxter International; and serving as a scientific advisor or member of AlphaYoung. R. Katz reports consultancy agreements with the University of California San Diego and the University of Pennsylvania and serving as a statistical editor for CJASN. J.A. Samuels reports receiving research funding from Novartis Pharmaceutical; receiving honoraria from MedStudy, Inc.; and patents and inventions with LAM Pharmaceuticals. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

The CKiD Study is supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants U01DK66143 and U01DK66174, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants U24DK082194 and U24DK066116, and additional funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The work for this ancillary study was also supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants 5T32DK104717-05 (to C.Y. Bakhoum), K23 DK114556 (to P.S. Garimella), and K24 DK110427 (to J.H. Ix), and American Heart Association grant 857722 (to C.Y. Bakhoum).

Acknowledgments

Data in this manuscript were collected by the CKiD prospective cohort study with clinical coordinating centers (principal investigators) at Children’s Mercy Hospital and the University of Missouri–Kansas City (Dr. Bradley Warady) and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (Dr. Susan Furth), the Central Biochemistry Laboratory (Dr. George Schwartz) at the University of Rochester Medical Center, and the data coordinating center (Drs. Alvaro Muñoz and Derek Ng) at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The CKiD website is located at https://statepi.jhsph.edu/ckid, and a list of CKiD collaborators can be found at https://statepi.jhsph.edu/ckid/site-investigators/.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Data Sharing Statement

The CKiD cohort deidentified participant data and data dictionaries used in our analyses are available through the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Central Repository.

References

- 1.Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, Blowey D, Carroll AE, Daniels SR, de Ferranti SD, Dionne JM, Falkner B, Flinn SK, Gidding SS, Goodwin C, Leu MG, Powers ME, Rea C, Samuels J, Simasek M, Thaker VV, Urbina EM; Subcommittee on Screening and Management of High Blood Pressure in Children : Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 140: e20171904, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flynn JT, Daniels SR, Hayman LL, Maahs DM, McCrindle BW, Mitsnefes M, Zachariah JP, Urbina EM; American Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension and Obesity in Youth Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young : Update: Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in children and adolescents: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 63: 1116–1135, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wühl E, Trivelli A, Picca S, Litwin M, Peco-Antic A, Zurowska A, Testa S, Jankauskiene A, Emre S, Caldas-Afonso A, Anarat A, Niaudet P, Mir S, Bakkaloglu A, Enke B, Montini G, Wingen A-M, Sallay P, Jeck N, Berg U, Caliskan S, Wygoda S, Hohbach-Hohenfellner K, Dusek J, Urasinski T, Arbeiter K, Neuhaus T, Gellermann J, Drozdz D, Fischbach M, Möller K, Wigger M, Peruzzi L, Mehls O, Schaefer F; ESCAPE Trial Group : Strict blood-pressure control and progression of renal failure in children. N Engl J Med 361: 1639–1650, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group : KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease. Available at: https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/KDIGO-2021-BPGL.pdf. Accessed July 19, 2021

- 5.Yano Y, Kario K: Nocturnal blood pressure and cardiovascular disease: A review of recent advances. Hypertens Res 35: 695–701, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdalla M, Caughey MC, Tanner RM, Booth JN 3rd, Diaz KM, Anstey DE, Sims M, Ravenell J, Muntner P, Viera AJ, Shimbo D: Associations of blood pressure dipping patterns with left ventricular mass and left ventricular hypertrophy in Blacks: The Jackson Heart Study. J Am Heart Assoc 6: e004847, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahman M, Griffin V, Heyka R, Hoit B: Diurnal variation of blood pressure; reproducibility and association with left ventricular hypertrophy in hemodialysis patients. Blood Press Monit 10: 25–32, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson MB, Hix JK, Vidt DG, Brotman DJ: Association of impaired diurnal blood pressure variation with a subsequent decline in glomerular filtration rate. Arch Intern Med 166: 846–852, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu M, Takahashi H, Morita Y, Maruyama S, Mizuno M, Yuzawa Y, Watanabe M, Toriyama T, Kawahara H, Matsuo S: Non-dipping is a potent predictor of cardiovascular mortality and is associated with autonomic dysfunction in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 563–569, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoshide S, Kario K, Hoshide Y, Umeda Y, Hashimoto T, Kunii O, Ojima T, Shimada K: Associations between nondipping of nocturnal blood pressure decrease and cardiovascular target organ damage in strictly selected community-dwelling normotensives. Am J Hypertens 16: 434–438, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaques DA, Müller H, Martinez C, De Seigneux S, Martin P-Y, Ponte B, Saudan P: Nondipping pattern on 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is associated with left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease. Blood Press Monit 23: 244–252, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitsnefes M, Flynn J, Cohn S, Samuels J, Blydt-Hansen T, Saland J, Kimball T, Furth S, Warady B; CKiD Study Group : Masked hypertension associates with left ventricular hypertrophy in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 137–144, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitsnefes MM, Kimball TR, Daniels SR: Office and ambulatory blood pressure elevation in children with chronic renal failure. Pediatr Nephrol 18: 145–149, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta D, Chaturvedi S, Chandy S, Agarwal I: Role of 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in children with chronic kidney disease. Indian J Nephrol 25: 355–361, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macumber IR, Weiss NS, Halbach SM, Hanevold CD, Flynn JT: The association of pediatric obesity with nocturnal non-dipping on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Am J Hypertens 29: 647–652, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakhoum CY, Vuong KT, Carter CE, Gabbai FB, Ix JH, Garimella PS: Proteinuria and nocturnal blood pressure dipping in hypertensive children and adolescents. Pediatr Res 90: 876–881, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber SAT, Santos VJ, Semenzati GO, Martin LC: Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in children with obstructive sleep apnea and primary snoring. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 76: 787–790, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furth SL, Cole SR, Moxey-Mims M, Kaskel F, Mak R, Schwartz G, Wong C, Muñoz A, Warady BA: Design and methods of the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children (CKiD) prospective cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1006–1015, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkinson MA, Ng DK, Warady BA, Furth SL, Flynn JT: The CKiD study: Overview and summary of findings related to kidney disease progression. Pediatr Nephrol 36: 527–538, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz GJ, Haycock GB, Edelmann CM Jr., Spitzer A: A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in children derived from body length and plasma creatinine. Pediatrics 58: 259–263, 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz GJ, Muñoz A, Schneider MF, Mak RH, Kaskel F, Warady BA, Furth SL: New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 629–637, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flynn JT, Mitsnefes M, Pierce C, Cole SR, Parekh RS, Furth SL, Warady BA; Chronic Kidney Disease in Children Study Group : Blood pressure in children with chronic kidney disease: A report from the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children study. Hypertension 52: 631–637, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samuels J, Ng D, Flynn JT, Mitsnefes M, Poffenbarger T, Warady BA, Furth S; Chronic Kidney Disease in Children Study Group : Ambulatory blood pressure patterns in children with chronic kidney disease. Hypertension 60: 43–50, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devereux RB, Reichek N: Echocardiographic determination of left ventricular mass in man. Anatomic validation of the method. Circulation 55: 613–618, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khoury PR, Mitsnefes M, Daniels SR, Kimball TR: Age-specific reference intervals for indexed left ventricular mass in children. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 22: 709–714, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz GJ, Abraham AG, Furth SL, Warady BA, Muñoz A: Optimizing iohexol plasma disappearance curves to measure the glomerular filtration rate in children with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 77: 65–71, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brady TM, Roem J, Cox C, Schneider MF, Wilson AC, Furth SL, Warady BA, Mitsnefes M: Adiposity, sex, and cardiovascular disease risk in children with CKD: A longitudinal study of youth enrolled in the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children (CKiD) study. Am J Kidney Dis 76: 166–173, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lilien MR, Groothoff JW: Cardiovascular disease in children with CKD or ESRD. Nat Rev Nephrol 5: 229–235, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaudhuri A, Sutherland SM, Begin B, Salsbery K, McCabe L, Potter D, Alexander SR, Wong CJ: Role of twenty-four-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in children on dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 870–876, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seeman T, Hradský O, Gilík J: Nocturnal blood pressure non-dipping is not associated with increased left ventricular mass index in hypertensive children without end-stage renal failure. Eur J Pediatr 175: 1091–1097, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanbay M, Turgut F, Uyar ME, Akcay A, Covic A: Causes and mechanisms of nondipping hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens 30: 585–597, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uzu T, Ishikawa K, Fujii T, Nakamura S, Inenaga T, Kimura G: Sodium restriction shifts circadian rhythm of blood pressure from nondipper to dipper in essential hypertension. Circulation 96: 1859–1862, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sachdeva A, Weder AB: Nocturnal sodium excretion, blood pressure dipping, and sodium sensitivity. Hypertension 48: 527–533, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bankir L, Bochud M, Maillard M, Bovet P, Gabriel A, Burnier M: Nighttime blood pressure and nocturnal dipping are associated with daytime urinary sodium excretion in African subjects. Hypertension 51: 891–898, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukuda M, Goto N, Kimura G: Hypothesis on renal mechanism of non-dipper pattern of circadian blood pressure rhythm. Med Hypotheses 67: 802–806, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muntner P, Lewis CE, Diaz KM, Carson AP, Kim Y, Calhoun D, Yano Y, Viera AJ, Shimbo D: Racial differences in abnormal ambulatory blood pressure monitoring measures: Results from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Am J Hypertens 28: 640–648, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hyman DJ, Ogbonnaya K, Taylor AA, Ho K, Pavlik VN: Ethnic differences in nocturnal blood pressure decline in treated hypertensives. Am J Hypertens 33: 884–891, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Booth JN III, Li M, Shimbo D, Hess R, Irvin MR, Kittles R, Wilson JG, Jorde LB, Cheung AK, Lange LA, Lange EM, Yano Y, Muntner P, Bress AP: West African ancestry and nocturnal blood pressure in African Americans: The Jackson Heart Study. Am J Hypertens 31: 706–714, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hui WF, Betoko A, Savant JD, Abraham AG, Greenbaum LA, Warady B, Moxey-Mims MM, Furth SL: Assessment of dietary intake of children with chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol 32: 485–494, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stergiou GS, Bountzona I, Alamara C, Vazeou A, Kollias A, Ntineri A: Reproducibility of office and out-of-office blood pressure measurements in children: Implications for clinical practice and research. Hypertension 77: 993–1000, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]