Abstract

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) represents the third most frequent cause of acute cardiovascular syndrome. Among VTE, acute pulmonary embolism (APE) is the most life-threatening complication. Due to the low specificity of symptoms clinical diagnosis of APE may be sometimes very difficult. Accordingly, the latest European guidelines only suggest clinical prediction tests for diagnosis of APE, eventually associated with D-dimer, a biomarker burdened by a very low specificity. A growing body of evidence is highlighting the role of miRNAs in hemostasis and thrombosis. Due to their partial inheritance and susceptibility to the environmental factors, miRNAs are increasingly described as active modifiers of the classical Virchow's triad. Clinical evidence on deep venous thrombosis reported specific miRNA signatures associated to thrombosis development, organization, recanalization, and resolution. Conversely, data of miRNA profiling as a predictor/diagnostic marker of APE are still preliminary. Here, we have summarized clinical evidence on the potential role of miRNA in diagnosis of APE. Despite some intriguing insight, miRNA assay is still far from any potential clinical application. Especially, the small sample size of cohorts likely represents the major limitation of published studies, so that extensive analysis of miRNA profiles with a machine learning approach are warranted in the next future. In addition, the cost-benefit ratio of miRNA assay still has a negative impact on their clinical application and routinely test.

1. Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a family of disease that includes deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and acute pulmonary embolism (APE). VTE is commonly found in clinical practice being the third cause of acute cardiovascular syndrome after myocardial infarction and stroke [1]. Among this class of disease, APE represents the most serious complication of VTE thus requiring early diagnosis and treatment. The incidence of APE ranges from about 39 to 115 per 100.000 population every year and accounts for about 300,000 death/year in US [2]. A recent increased in its incidence was also observed during SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, likely as an expression of the thromboinflammatory storm triggered by infection [3]. Symptoms of APE are often not specific—ranging from mild symptoms to sudden death—and clinical diagnosis may be sometimes very difficult [4]. Pulmonary angiography and computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) are highly specific for diagnosis of APE [5], but they require intravenous contrast infusion that may represents a great concern in patients with chronic kidney failure or allergic diathesis. Latest European guidelines published in 2019 have included two major prediction tests for APE diagnosis: the revised Geneva rule and the Wells score [6]. Their goal is to increase the rate of APE diagnosis, by stratifying patients across risk categories. Nevertheless, for only 65% of patients categorized at high-risk APE is finally diagnosed. The search for biomarkers able to implement the diagnostic chart—alone or combined with clinical scores—then represents an urgent clinical need. D-dimer assay offers high sensitivity but low specificity, thus limiting its application as exclusion test for diagnosis of APE [7, 8]. Here, we summarize the role of microRNAs (miRNAs) in VTE, with a special focus on APE. Great attention has also been paid to link current pathophysiological evidence with potential therapeutic implications.

2. miRNAs: Pathophysiological Actors and Potential Useful Biomarkers of Thromboembolism

miRNAs are noncoding RNAs around 22 nucleotides long [9] mainly involved in posttranslational messenger RNA (mRNAs) degradation [10]. miRNAs generate from gene exons—or less frequently introns—and processed into pre-miRNAs [11–13]. Once in the cytoplasm, pre-miRNAs are processed by a Dicer into mature miRNAs [14] that are released freely or within microvesicles. The way miRNAs are carried also has high relevance in their pathophysiology. Within microvesicles, miRNAs may complex and interact with other molecules, even those involved in thrombosis and homeostasis. Furthermore, microvesicle composition may provide information on the cellular source of miRNAs [15]. By targeting hundreds of genes [16], the spectrum of activity for each miRNAs broadly ranges from translation repression [17] to stimulation [18, 19], target degradation, and transcriptional/posttranscriptional gene silencing as well [20, 21]. The regulatory role of miRNAs is known since decades [22] but their applications as diagnostic/prognostic markers [23]—and even therapeutic targets [24]—have been only recently investigated. Many features would characterize miRNAs as ideal biomarkers: stability, low structural complexity, lack of postprocessing modifications, organ- and cell-specific expression, and tissue- and pathology-specific regulation [25–27]. miRNAs are also detectable in many fluids—e.g., such as serum, plasma, urine, and saliva [28]—where they regulate different biological processes [29, 30]. In light of these properties, miRNAs are being increasingly described as potential biomarkers of disease, including cardiovascular ones: heart failure, arrhythmias, coronary artery disease, myocardial fibrosis, and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) [31, 32]. Although bioinformatics plays a big part in identifying putative miRNAs, a range of techniques has been developed to overcome technical challenges and simplifying miRNA profiling. Alongside quantitative PCR—characterized by high specificity and sensitivity but limited to small scale experiments—clinical application of miRNA assay relies on array or multiplex profiling, which maintain high sensitivity and specificity alongside with a straightforward data analysis. Much more is expected from the incoming development of RNA sequencing that would perform whole-genome analysis.

2.1. The Role of miRNA on Hemostasis and Thrombosis

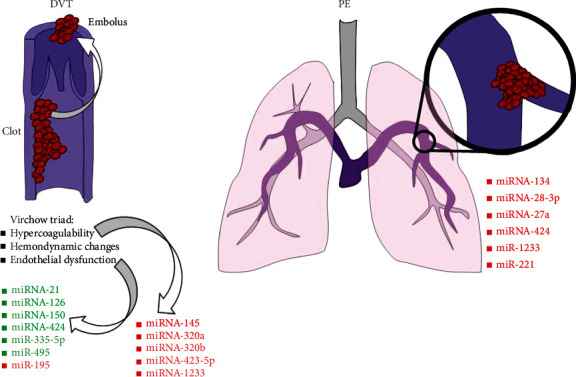

A growing body of evidence has identified for miRNAs an active role of hemostasis and thrombosis. This effect may be driven by an active modulation of specific proteins: factor XI, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1), protein S, fibrinogen, tissue factor, and antithrombin [33, 34]. Due to their partial inheritance expression and susceptibility to environmental factors, miRNAs may then have a dynamic role in VTE, which would encompass the whole classical Virchow's triad. Many of them have been then tested in clinical studies [35, 36], but a major role has been accounted for miR-134, miR-145, miR-195, miR-483-3p, miR-532, and miR-1233 [37]. Among them, miR-145 is specific of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and exerts regulatory properties on tissue factor (TF) gene expression. miR-145 expression is also inversely correlated proinflammatory cytokines and lower incidence of thrombosis [38, 39]. Specific miRNA signatures have been then associated to all stage of thrombotic process from initiation to organization, recanalization, and resolution. Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) exert a control on these processes [40]. Their suppression results in the overexpression of proinflammatory cytokines and inhibition of VEGF functions, hallmark of thrombotic risk, and associated with miR-195. GABA type A receptor-associated protein like 1 activation has been identified as the direct target by which miR-195 exerts its detrimental functions on cell proliferation, migration, angiogenesis, and autophagy [41].

The role of miRNAs on hemostasis and thrombosis is not only limited to the coagulation cascade but also involves platelet activation and reactivity [42, 43]. Increase in platelet reactivity has been associated with the overexpression of miR-320 family as consequence of the interaction with the WIPF1 gene encoding for WAS/WASL-interacting protein [44]. miR-423-5p is another biomarkers of platelet aggregation [45]. Both miR-320 family and miR-423-5p may then raise susceptibility for VTE [46], whereas miR-1233 has been indicated as connecting signal between platelets and ECs [47].

Other miRNAs are finally implicated in vascular repair and thrombus resolution. This effect—mediated by angiogenesis and EPC proliferation/migration—involves miR-21, miR-126, miR-150, and miR-424 [48–51].

Although far from routinely clinical application, identifying those specific miRNA signatures—virtually targeting all Virchow's triad [52]—would have a rationale for VTE risk stratification [53].

3. miRNAs in Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Experimental Data and Clinical Evidence

Despite the epidemiological and clinical relevance, diagnosis of APE still represents an unmet clinical need. D-dimer is routinely used as biomarker of APE but it is burdened by a very low specificity [54]. Many other biomarkers tested in the last decades failed to replace or improve D-dimer performance [55–57]. Concerning miRNAs, experimental data are mainly focusing on vascular response to APE [58–63], while data on APE predictor/diagnosis are few. The lack of standardization their assay represents an additional confounder. However, all studies here considered share similar laboratory processes with differences in protocol of centrifugation (Table 1).

Table 1.

miRNAs studied as potential diagnostic biomarkers for APE.

| Author | Year | Study design | miRNA (cut-off) | Sample | Results | Concerning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mao et al. [63] | 2011 | 32 APE patients vs. 32 healthy controls vs. 22 non-APE patients∗ | miRNA-134 (10-fold difference between miRNA levels) | Plasma | miRNA-134 was significantly higher in APE with an AUC of 0.83 (95% CI, 0.74 to 0.93) p < 0.001 | miRNA-134 was elevated also in UA |

| Hoekstra et al. [65] | 2016 | 37 APE patients vs. 37 healthy controls | miRNA-28-3p (4-fold difference between miRNA levels) | Plasma | miRNA-28-3p (but neither miRNA-134 nor miRNA-210) show a significant increase—stable during the first 6 hours—in APE. The AUC was 0.79 (95% CI 0.69 to 0.90) | miRNA-28-3p was elevated also in DM and GI malignancies |

| Zhou et al. [66] | 2018 | 78 APE patients vs. 70 healthy controls | miRNA-27a/b | Plasma | miRNA-27a expression was upregulated in APE patients (p < 0.001). The AUC was 0.78 (95% CI 0.69 to 0.88); p < 0.001. miRNA-27a significantly improved the AUC of D-dimer | miRNA-27 levels are also influenced by LVH |

| Ba et al. [69] | 2016 | 30 APE patients vs. NSTEMI (n = 30), DVT (n = 6), PAH (n = 15), and 12 healthy controls | miRNA-1233 (11-fold difference between miRNA levels) | Serum | In acute state (1st day), miRNA-1233 was even able to discriminate APE from NSTEMI with an AUC of 0.95 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.00); p < 0.001 highest serum level on 1st day. miRNA-1233 then decreased levels on 3rd and 5th day with lower values reached at 9 months | None. Even, miRNA-1233 was better than miRNA-134 and miRNA-27a as APE biomarker |

| Nie et al. [72] | 2018 | 60 APE vs. 50 healthy controls | miRNA-221 (4-fold difference between miRNA levels) | Plasma | miR-221 was significantly upregulated in APE (p < 0.05) and showed positive correlations with BNP, troponin, and D-dimer. AUC for plasma miR-221 was 0.82 (95% CI 0.76 to 0.91), higher than that of D-dimer | miRNA-221 was elevated also in MI and PAH |

APE: acute pulmonary embolism; AUC: area under the curve; UA: unstable angina; DM: diabetes mellitus; GI: gastrointestinal; LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy; NSTEMI: non-ST elevated nyocardial infarction; DVT: deep venous thrombosis; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; BNP: B-type natriuretic peptide; MI: myocardial infarction.

First in 2011, a panel of 30 different miRNAs was tested in a case control study matching patients with suspected APE [64]. Among the most expressed miRNAs (10-fold or higher), plasmatic miR-134 was the best predictor of APE, also able to identify high/intermediate vs. low-risk patients. miR-134 was then identified as specifically expressed by mononuclear blood cells [65] but its specificity for APE diagnosis was not later confirmed. Rather, a persistent increase (about 3.6-fold) in miR-28-3p was observed even hours after the onset of APE [66]. A release by hypoxic-ischemic lung cells as response to inositol phosphate metabolism and phosphatidylinositol pathway activation has been also hypothesized as mechanisms for the miR-28-3p expression. More recently, plasmatic concentrations of miR-27a and miR-27b emerged as further potential diagnostic markers of APE, being able to increase diagnostic potential of D-dimer [67]. Accordingly, the miR-27 family is known to regulate the TF pathway inhibitor (TFPI) in ECs [68, 69]. Platelet-derived miR-1233 is another candidate biomarker associated with suppressant activity on platelet activation and P-selectin expression [70]. Clinical relevance of miR-1233 relies on the ability in discriminating APE from other thrombotic disease (e.g., non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and DVT) with an early predictive value, higher than miRNA-27a and miRNA-134 [71]. Finally, more recent analysis on extensive miRNA panels identified a role for plasmatic miR-221, a VSMC-specific product upregulated by platelet-derived growth factor [72, 73]. Plasmatic miR-221 significantly increased in patients with APE with a cut-off set at 4-fold overexpression [74]. The abovementioned studies provide the rationale but lacks of definitive proof for translating miRNA assay in clinical practice (Figure 1). Small sample size and bias involving patient selection and miRNA analysis protocol are likely their main weakness. Future studies are expected to address these issues performing real-life analyses and finally test whether miRNA assay may overcome D-dimer in diagnosing APE. To date, miRNA assay still remains far from any potential clinical translation.

Figure 1.

List of most important microRNAs (miRNAs) involved in venous thromboembolism. Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) determinants are classically grouped into the Virchow trial. They may be influenced by a wide range of miRNAs, especially hypercoagulability and endothelial dysfunction. Less is known about pulmonary embolism (PE). Whereas pathophysiological data are still lacking, different miRNAs are being increasingly described as potential biomarker of disease.

4. Conclusion

The recognition of a circulating biomarker able to stratify the risk for APE would lead more accurately patients with clinical suspect of APE to second-level diagnostic tools, such as CTPA. This would be of paramount relevance for patients with mild/severe contraindications to CTPA, especially those with chronic kidney disease or history of medium contrast allergic reactions. Data from preliminary studies also suggest a potential role of miRNAs in discriminating APE from the most frequent confusing clinical conditions (firstly NSTEMI). Such an achievement would shorten the diagnostic chart and the time-to-treatment protocols, in accordance with the classic paradigm of “golden hour.” Even if it were, benefit of miRNA assay should also exceed the economic burden of their assay. The need of large panel assays and interaction analyses makes machine learning approach mandatory to finally establish the sensitivity of miRNA (as single biomarker or panel) and their clinical relevance. Additional goals should also include high sensitivity and specificity for APE. Comparing miRNAs with other biomarkers of APE (e.g., NT-proBNP, troponins, and D-dimer) would further help in establishing their potential for clinical use. Not last, being miRNA expression partially inherited, large-scale studies should consider different ethnic groups. Finally, any potential role of anticoagulation therapies on miRNA expression remains unclear.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Rete Cardiologica of Italian Ministry of Health (#2754291) to Prof. F. Montecucco.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Thrombosis: a major contributor to the global disease burden. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis . 2014;12(10):1580–1590. doi: 10.1111/jth.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wendelboe A. M., Raskob G. E. Global burden of thrombosis: epidemiologic aspects. Circulation Research . 2016;118(9):1340–1347. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mondal S., Quintili A. L., Karamchandani K., Bose S. Thromboembolic disease in COVID-19 patients: a brief narrative review. Journal of Intensive Care . 2020;8(1):p. 70. doi: 10.1186/s40560-020-00483-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein P. D., Beemath A., Matta F., et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with acute pulmonary embolism: data from PIOPED II. The American Journal of Medicine . 2007;120(10):871–879. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Konstantinides S. V., Meyer G., Becattini C., et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS) European Heart Journal . 2020;41(4):543–603. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konstantinides S. V., Meyer G. The 2019 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. European Heart Journal . 2019;40(42):3453–3455. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein P. D., Hull R. D., Patel K. C., et al. D-dimer for the exclusion of acute venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine . 2004;140(8):589–602. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douma R. A., Kamphuisen P. W., Buller H. R. Acute pulmonary embolism. Part 1: epidemiology and diagnosis. Nature Reviews. Cardiology . 2010;7(10):585–596. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau N. C., Lim L. P., Weinstein E. G., Bartel D. P. An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science . 2001;294(5543):858–862. doi: 10.1126/science.1065062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartel D. P. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell . 2004;116(2):281–297. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bushati N., Cohen S. M. MicroRNA functions. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology . 2007;23(1):175–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai B., Li J., Wang J., et al. MicroRNA-124 regulates cardiomyocyte differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells via targeting STAT3 signaling. Stem Cells . 2012;30(8):1746–1755. doi: 10.1002/stem.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee Y., Kim M., Han J., et al. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. The EMBO Journal . 2004;23(20):4051–4060. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruby J. G., Jan C. H., Bartel D. P. Intronic microRNA precursors that bypass Drosha processing. Nature . 2007;448(7149):83–86. doi: 10.1038/nature05983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zifkos K., Dubois C., Schafer K. Extracellular vesicles and thrombosis: update on the clinical and experimental evidence. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2021;22(17):p. 9317. doi: 10.3390/ijms22179317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gangaraju V. K., Lin H. MicroRNAs: key regulators of stem cells. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology . 2009;10(2):116–125. doi: 10.1038/nrm2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brennecke J., Stark A., Russell R. B., Cohen S. M. Principles of microRNA-target recognition. PLoS Biology . 2005;3(3, article e85) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vasudevan S., Tong Y., Steitz J. A. Switching from repression to activation: microRNAs can up-regulate translation. Science . 2007;318(5858):1931–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1149460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozak M. Faulty old ideas about translational regulation paved the way for current confusion about how microRNAs function. Gene . 2008;423(2):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang H. W., Wentzel E. A., Mendell J. T. A hexanucleotide element directs microRNA nuclear import. Science . 2007;315(5808):97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1136235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim D. H., Saetrom P., Snove O., Jr., Rossi J. J. MicroRNA-directed transcriptional gene silencing in mammalian cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America . 2008;105(42):16230–16235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808830105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lagos-Quintana M., Rauhut R., Lendeckel W., Tuschl T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science . 2001;294(5543):853–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1064921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reid G., Kirschner M. B., van Zandwijk N. Circulating microRNAs: association with disease and potential use as biomarkers. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology . 2011;80(2):193–208. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elbashir S. M., Lendeckel W., Tuschl T. RNA interference is mediated by 21- and 22-nucleotide RNAs. Genes & Development . 2001;15(2):188–200. doi: 10.1101/gad.862301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Rooij E. The art of microRNA research. Circulation Research . 2011;108(2):219–234. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell P. S., Parkin R. K., Kroh E. M., et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America . 2008;105(30):10513–10518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang K., Zhang S., Marzolf B., et al. Circulating microRNAs, potential biomarkers for drug-induced liver injury. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America . 2009;106(11):4402–4407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813371106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber J. A., Baxter D. H., Zhang S., et al. The microRNA spectrum in 12 body fluids. Clinical Chemistry . 2010;56(11):1733–1741. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.147405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu P., Guo M., Hay B. A. MicroRNAs and the regulation of cell death. Trends in Genetics . 2004;20(12):617–624. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suarez Y., Sessa W. C. MicroRNAs as novel regulators of angiogenesis. Circulation Research . 2009;104(4):442–454. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.191270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalozoumi G., Yacoub M., Sanoudou D. MicroRNAs in heart failure: small molecules with major impact. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract . 2014;2014(2):79–102. doi: 10.5339/gcsp.2014.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fichtlscherer S., de Rosa S., Fox H., et al. Circulating microRNAs in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation Research . 2010;107(5):677–684. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.215566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teruel R., Corral J., Perez-Andreu V., Martinez-Martinez I., Vicente V., Martinez C. Potential role of miRNAs in developmental haemostasis. PLoS One . 2011;6(3, article e17648) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teruel-Montoya R., Rosendaal F. R., Martinez C. MicroRNAs in hemostasis. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis . 2015;13(2):170–181. doi: 10.1111/jth.12788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Starikova I., Jamaly S., Sorrentino A., et al. Differential expression of plasma miRNAs in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism and healthy control individuals. Thrombosis Research . 2015;136(3):566–572. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X., Sundquist K., Svensson P. J., et al. Association of recurrent venous thromboembolism and circulating microRNAs. Clinical Epigenetics . 2019;11(1):p. 28. doi: 10.1186/s13148-019-0627-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiang Q., Zhang H. X., Wang Z., et al. The predictive value of circulating microRNAs for venous thromboembolism diagnosis: a systematic review and diagnostic meta-analysis. Thrombosis Research . 2019;181:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2019.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Leary L., Sevinc K., Papazoglou I. M., et al. Airway smooth muscle inflammation is regulated by microRNA-145 in COPD. FEBS Letters . 2016;590(9):1324–1334. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahu A., Jha P. K., Prabhakar A., et al. MicroRNA-145 impedes thrombus formation _via_ targeting tissue factor in venous thrombosis. eBioMedicine . 2017;26:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abou-Saleh H., Yacoub D., Théorêt J. F̧., et al. Endothelial progenitor cells bind and inhibit platelet function and thrombus formation. Circulation . 2009;120(22):2230–2239. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.894642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mo J., Zhang D., Yang R. MicroRNA-195 regulates proliferation, migration, angiogenesis and autophagy of endothelial progenitor cells by targeting GABARAPL1. Bioscience Reports . 2016;36(5) doi: 10.1042/BSR20160139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garcia A., Dunoyer-Geindre S., Fish R. J., Neerman-Arbez M., Reny J. L., Fontana P. Methods to investigate miRNA function: focus on platelet reactivity. Thrombosis and Haemostasis . 2021;121(4):409–421. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1718730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elia E., Montecucco F., Portincasa P., Sahebkar A., Mollazadeh H., Carbone F. Update on pathological platelet activation in coronary thrombosis. Journal of Cellular Physiology . 2019;234(3):2121–2133. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagalla S., Shaw C., Kong X., et al. Platelet microRNA-mRNA coexpression profiles correlate with platelet reactivity. Blood . 2011;117(19):5189–5197. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-299719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gidlof O., van der Brug M., Ohman J., et al. Platelets activated during myocardial infarction release functional miRNA, which can be taken up by endothelial cells and regulate ICAM1 expression. Blood . 2013;121(19):3908–3917. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-461798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Braekkan S. K., Mathiesen E. B., Njolstad I., Wilsgaard T., Stormer J., Hansen J. B. Mean platelet volume is a risk factor for venous thromboembolism: the Tromsø study. Research and Practice in Thrombosis and Haemostasis . 2010;8(1):157–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li J., Tan M., Xiang Q., Zhou Z., Yan H. Thrombin-activated platelet-derived exosomes regulate endothelial cell expression of ICAM-1 via microRNA-223 during the thrombosis-inflammation response. Thrombosis Research . 2017;154:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meng Q., Wang W., Yu X., et al. Upregulation of microRNA-126 contributes to endothelial progenitor cell function in deep vein thrombosis via its target PIK3R2. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry . 2015;116(8):1613–1623. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Du X., Hong L., Sun L., et al. miR-21 induces endothelial progenitor cells proliferation and angiogenesis via targeting FASLG and is a potential prognostic marker in deep venous thrombosis. Journal of Translational Medicine . 2019;17(1):p. 270. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-2015-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bao C. X., Zhang D. X., Wang N. N., Zhu X. K., Zhao Q., Sun X. L. Retracted: MicroRNA-335-5p suppresses lower extremity deep venous thrombosis by targeted inhibition of PAI-1 via the TLR4 signalingpathway. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry . 2018;119(6):4692–4710. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hembrom A. A., Srivastava S., Garg I., Kumar B. MicroRNAs in venous thrombo-embolism. Clinica Chimica Acta . 2020;504:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fazzalari A., Basadonna G., Kucukural A., et al. A translational model for venous thromboembolism: microRNA expression in hibernating black bears. The Journal of Surgical Research . 2021;257:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Forrest A. R., Kanamori-Katayama M., Tomaru Y., et al. Induction of microRNAs, miR-155, miR-222, miR-424 and miR-503, promotes monocytic differentiation through combinatorial regulation. Leukemia . 2010;24(2):460–466. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oi M., Yamashita Y., Toyofuku M., et al. D-dimer levels at diagnosis and long-term clinical outcomes in venous thromboembolism: from the COMMAND VTE registry. Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis . 2020;49(4):551–561. doi: 10.1007/s11239-019-01964-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Newman J., Brailovsky Y., Allen S., et al. Angiopoietin-2 correlates with pulmonary embolism severity, right ventricular dysfunction, and intensive care unit admission. Vascular Medicine . 2021;26(5):556–560. doi: 10.1177/1358863X211002276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thoreau B., Galland J., Delrue M., et al. D-dimer level and neutrophils count as predictive and prognostic factors of pulmonary embolism in severe non-ICU COVID-19 patients. Viruses . 2021;13(5):p. 758. doi: 10.3390/v13050758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bontekoe E., Brailovsky Y., Hoppensteadt D., et al. Upregulation of inflammatory cytokines in pulmonary embolism using biochip-array profiling. Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis . 2021;27:p. 107602962110131. doi: 10.1177/10760296211013107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang M., Gu S., Liu Y., et al. miRNA-PDGFRB/HIF1A-lncRNA CTEPHA1 network plays important roles in the mechanism of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. International Heart Journal . 2019;60(4):924–937. doi: 10.1536/ihj.18-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miao R., Gong J., Zhang C., et al. Hsa_circ_0046159 is involved in the development of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis . 2020;49(3):386–394. doi: 10.1007/s11239-019-01998-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen H., Ma Q., Zhang J., Meng Y., Pan L., Tian H. miR‑106b‑5p modulates acute pulmonary embolism via NOR1 in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. International Journal of Molecular Medicine . 2020;45(5):1525–1533. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2020.4532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu T. W., Liu F., Kang J. Let-7b-5p is involved in the response of endoplasmic reticulum stress in acute pulmonary embolism through upregulating the expression of stress-associated endoplasmic reticulum protein 1. IUBMB Life . 2020;72(8):1725–1736. doi: 10.1002/iub.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ou M., Zhang C., Chen J., Zhao S., Cui S., Tu J. Overexpression of microRNA-340-5p inhibits pulmonary arterial hypertension induced by APE by downregulating IL-1β and IL-6. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids . 2020;21:542–554. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 63.Mao H. Y., Liu L. N., Hu Y. M. Mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomal miRNA-28-3p promotes apoptosis of pulmonary endothelial cells in pulmonary embolism. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences . 2020;24(20):10619–10631. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202010_23420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiao J., Jing Z. C., Ellinor P. T., et al. MicroRNA-134 as a potential plasma biomarker for the diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism. Journal of Translational Medicine . 2011;9(1):p. 159. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoekstra M., van der Lans C. A., Halvorsen B., et al. The peripheral blood mononuclear cell microRNA signature of coronary artery disease. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications . 2010;394(3):792–797. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhou X., Wen W., Shan X., et al. miR-28-3p as a potential plasma marker in diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Thrombosis Research . 2016;138:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang Q., Ma J., Jiang Z., Wu F., Ping J., Ming L. Diagnostic value of circulating microRNA-27a/b in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. International Angiology . 2018;37(1):19–25. doi: 10.23736/S0392-9590.17.03877-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ali H. O., Arroyo A. B., Gonzalez-Conejero R., et al. The role of microRNA-27a/b and microRNA-494 in estrogen-mediated downregulation of tissue factor pathway inhibitor α. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis . 2016;14(6):1226–1237. doi: 10.1111/jth.13321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arroyo A., Salloum-Asfar S., Pérez-Sánchez C., et al. Regulation of TFPIα expression by miR-27a/b-3p in human endothelial cells under normal conditions and in response to androgens. Scientific Reports . 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1038/srep43500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee B. K., Kim M. H., Lee S. Y., Son S. J., Hong C. H., Jung Y. S. Downregulated platelet miR-1233-5p in patients with Alzheimer's pathologic change with mild cognitive impairment is associated with Aβ-induced platelet activation via P-selectin. Journal of Clinical Medicine . 2020;9(6):p. 1642. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kessler T., Erdmann J., Vilne B., et al. Serum microRNA-1233 is a specific biomarker for diagnosing acute pulmonary embolism. Journal of Translational Medicine . 2016;14(1):p. 120. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nie X., Chen Y., Tan J., et al. MicroRNA-221-3p promotes pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells proliferation by targeting AXIN2 during pulmonary arterial hypertension. Vascular Pharmacology . 2019;116:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Davis B. N., Hilyard A. C., Nguyen P. H., Lagna G., Hata A. Induction of microRNA-221 by platelet-derived growth factor signaling is critical for modulation of vascular smooth muscle phenotype. The Journal of Biological Chemistry . 2009;284(6):3728–3738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808788200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu T., Kang J., Liu F. Plasma levels of microRNA-221 (miR-221) are increased in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Medical Science Monitor . 2018;24:8621–8626. doi: 10.12659/MSM.910893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]