Abstract

The molecular epidemiological characteristics of all Streptococcus pneumoniae strains isolated in a nationwide manner from patients with meningitis in The Netherlands in 1994 were investigated. Restriction fragment end labeling analysis demonstrated 52% genetic clustering among these penicillin-susceptible strains, a value substantially lower than the percentage of clustering among Dutch penicillin-nonsusceptible strains. Different serotypes were found within 8 of the 28 genetic clusters, suggesting that horizontal transfer of capsular genes is common among penicillin-susceptible strains. The degree of genetic clustering was much higher among serotype 3, 7F, 9V, and 14 isolates than among isolates of other serotypes, i.e., 6A, 6B, 18C, 19F, and 23F. We further studied the molecular epidemiological characteristics of pneumococci of serotype 3, which is considered the most virulent serotype and which is commonly associated with invasive disease in adults. Fifty epidemiologically unrelated penicillin-susceptible serotype 3 invasive isolates originating from the United States (n = 27), Thailand (n = 9), The Netherlands (n = 8), and Denmark (n = 6) were analyzed. The vast majority of the serotype 3 isolates (74%) belonged to two genetically distinct clades that were observed in the United States, Denmark, and The Netherlands. These data indicate that two serotype 3 clones have been independently disseminated in an international manner. Seven serotype 3 isolates were less than 85% genetically related to the other serotype 3 isolates. Our observations suggest that the latter isolates originated from horizontal transfer of the capsular type 3 gene locus to other pneumococcal genotypes. In conclusion, epidemiologically unrelated serotype 3 isolates were genetically more related than those of other serotypes. This observation suggests that serotype 3 has evolved only recently or has remained unchanged over long periods.

Streptococcus pneumoniae continues to be a common cause of serious and life-threatening infections, such as pneumonia, bacteremia, and meningitis, in both adults and children (1). Pneumococci can be classified according to differences in capsular polysaccharide structure. As many as 90 different capsular types can be distinguished by serotyping (10). The distribution of serotypes varies in different populations and different geographic areas, and certain pneumococcal serotypes are known to be more virulent than others (24, 28). Pneumococcal serotype 3 isolates are considered to represent the most virulent serotype. These isolates are often responsible for invasive disease (17, 20), particularly in adults (15, 19). Bacteremia caused by this organism is considered to have the highest mortality rate compared to that caused by other serotypes (15, 20). To date, the frequency of penicillin resistance among serotype 3 isolates has remained low (16).

Serotyping as a tool for epidemiological studies has several disadvantages. S. pneumoniae is a naturally transformable species, and frequent exchange of capsular genes occurs (2–4, 13, 23). In addition, serotyping determines the variation in a single genetic locus, i.e., the cps locus. Therefore, several other typing methods have been developed to assist with the identification of relatedness between strains and their cellular structures. These methods include multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (9), penicillin-binding protein (PBP) profile analysis (21, 22), pneumococcal surface protein A typing (22), and DNA fingerprint methods, such as pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (7), ribotyping, restriction fragment end labeling (RFEL) analysis, BOX PCR fingerprinting, and DNA fingerprinting of the PBP genes (14, 32). RFEL analysis provides a high degree of discriminatory power, and RFEL profiles are reproducible and suitable for computerized comparisons (14). In addition, RFEL analysis provides a DNA fingerprint that represents multiple loci in the pneumococcal genome. This technique is routinely used in our laboratory to generate a data library of pneumococcal DNA fingerprints. In this study, we investigated the molecular epidemiological characteristics of S. pneumoniae strains isolated in a nationwide manner from patients with meningitis in The Netherlands in 1994. The genetic relatedness within pneumococcal serotypes was determined. In addition, we studied the molecular epidemiological characteristics of epidemiologically unrelated serotype 3 pneumococci from four distinct countries. The isolates were characterized by serotyping, RFEL analysis, and PBP genotyping.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

We studied a collection of S. pneumoniae strains (n = 153) isolated from Dutch patients suffering from meningitis in The Netherlands in 1994. These strains were collected by the National Reference Center for Bacterial Meningitis in a nationwide manner and represent all pneumococcal meningitis isolates collected in a 1-year period. In addition, these strains were penicillin susceptible and were presumed to be epidemiologically unrelated. In addition, 42 penicillin-susceptible invasive serotype 3 pneumococci were isolated from patients in the United States (n = 27), Thailand (n = 9), and Denmark (n = 6). The latter strains were also presumed to be epidemiologically unrelated, since they were isolated from various geographic regions within these countries and at different times ranging from 1960 to 1962 and from 1992 to 1998 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Geographic origins of and isolation dates for 50 penicillin-susceptible serotype 3 pneumococcal isolates

| Strain designation | State or country | Isolation date | RFEL type | (pbpla-pbp2b-pbp2x) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DK001 | Denmark | 1961 | 294 | 02-02-71 |

| DK002 | Denmark | 1961 | 294 | 02-02-71 |

| DK003 | Denmark | 1960 | 292 | 02-02-71 |

| DK004 | Denmark | 1991 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| DK005 | Denmark | 1992 | 299 | 02-02-71 |

| DK006 | Denmark | 1962 | 289 | 02-02-71 |

| NL100 | The Netherlands | 1994 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| NL101 | The Netherlands | 1994 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| NL102 | The Netherlands | 1994 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| NL103 | The Netherlands | 1994 | 393 | 02-02-71 |

| NL104 | The Netherlands | 1994 | 300 | 02-02-71 |

| NL106 | The Netherlands | 1994 | 291 | 02-02-71 |

| NL107 | The Netherlands | 1994 | 290 | 02-02-71 |

| NL108 | The Netherlands | 1994 | 294 | 02-02-71 |

| TH001 | Thailand | 1998 | 093 | 02-02-71 |

| TH002 | Thailand | 1998 | 096 | 09-02-71 |

| TH003 | Thailand | 1998 | 122 | 02-02-03 |

| TH004 | Thailand | 1998 | 122 | 02-02-03 |

| TH005 | Thailand | 1998 | 121 | 02-02-03 |

| TH006 | Thailand | 1998 | 123 | 02-02-03 |

| TH007 | Thailand | 1998 | 165 | 02-02-71 |

| TH008 | Thailand | 1998 | 105 | 02-02-03 |

| TH009 | Thailand | 1998 | 242 | 02-02-71 |

| US001 | United States | 1960 | 294 | 02-02-71 |

| US002 | United States | 1960 | 294 | 02-02-71 |

| US003 | Alaska | 1995 | 295 | 02-02-71 |

| US004 | Colorado | 1993 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US005 | California | 1992 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US006 | Alaska | 1993 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US007 | Alaska | 1993 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US008 | Alaska | 1993 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US009 | Wisconsin | 1992 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US010 | Pennsylvania | 1995 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US011 | Pennsylvania | 1995 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US012 | Maryland | 1995 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US013 | Alaska | 1993 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US014 | Oklahoma | 1996 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US015 | Washington | 1993 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US016 | Washington | 1995 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US017 | Ohio | 1993 | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US018 | United States | 1990s | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US019 | United States | 1990s | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US020 | United States | 1990s | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US021 | United States | 1990s | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US022 | United States | 1990s | 167 | 02-02-71 |

| US023 | Maryland | 1994 | 297 | 02-02-71 |

| US024 | United States | 1990s | 297 | 02-02-71 |

| US025 | California | 1994 | 298 | 02-02-71 |

| US026 | Wisconsin | 1992 | 296 | 02-02-71 |

| US027 | Oklahoma | 1996 | 076 | 02-02-71 |

Serotyping.

Pneumococci were serotyped on the basis of capsular swelling (Quellung reaction) observed microscopically after suspension in antisera prepared at Statens Seruminstitut, Copenhagen, Denmark (8).

RFEL analysis.

Typing of pneumococcal strains by RFEL analysis was performed as described by van Steenbergen et al. (33) and adapted by Hermans et al. (14). Briefly, purified pneumococcal DNA was digested with restriction enzyme EcoRI. The DNA restriction fragments were end labeled at 72°C with [α-32P]dATP by using Taq DNA polymerase (Goldstar; Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium). The radiolabeled fragments were denatured and separated electrophoretically on a 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gel containing 8 M urea. The gel was transferred to filter paper, vacuum dried (HBI, Saddle Brook, N.Y.), and exposed to ECL Hyperfilms (Amersham, Little Chalfont, Bucks, United Kingdom).

PBP genotyping.

Genetic polymorphisms of the penicillin resistance genes pbpla, pbp2b, and pbp2x were investigated by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. PCR amplification of the PBP-encoding genes was performed with a 50-μl PCR buffer system containing 75 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 20 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.01% (wt/vol) Tween 20, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 10 pmol of each primer, 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Goldstar), and 10 ng of purified chromosomal DNA. Cycling was performed with a PTC-100 programmable thermal controller (MJ Research, Watertown, Mass.) and consisted of the following steps: predenaturation at 94°C for 1 min; 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 52°C, and 2 min at 72°C; and final extension at 72°C for 3 min. The primers used to amplify the genes pbp1a, pbp2b, and pbp2x were described previously (3, 6, 21). The amplification products (5 μl) were digested with restriction endonuclease HinfI and separated by electrophoresis in 2.5% agarose gels (27). Gels were scanned and printed with a Geldoc 2000 system (Biorad, Veenendaal, The Netherlands). The different PBP genotypes are represented by a three-number code (e.g., 06–14–43), referring to the restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns of the genes pbp1a (pattern 6), pbp2b (pattern 14), and pbp2x (pattern 43), respectively.

Computer-assisted analysis of the DNA banding patterns.

The RFEL types were analyzed with the Windows version of Gelcompar software, version 4 (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium), after imaging of the RFEL autoradiograms with Image Master DTS (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). DNA fragments in the molecular size range of 160 to 400 bp were documented. The DNA banding patterns were normalized with pneumococcus-specific bands present in the RFEL banding patterns of all strains. Comparison of the banding patterns was performed by the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic averages (26) and with the Jaccard similarity coefficient applied to peaks (31). Computer-assisted analysis and the methods and algorithms used in this study were in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer of Gelcompar. A tolerance of 1.2% in band positions was applied during comparison of the DNA patterns.

For evaluation of the genetic relatedness of the strains, we used the following definitions: (i) strains of a particular RFEL type are 100% identical on the basis of RFEL analysis, (ii) an RFEL cluster represents a group of RFEL types that differs by only one band (approximately ≥95% genetic relatedness), and (iii) an RFEL clade represents a group of RFEL types that differs by less than four bands (approximately ≥85% genetic relatedness). The genetic heterogeneity is defined as the number of RFEL clades representing one or more strains divided by the total number of strains.

RESULTS

Epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal isolates in The Netherlands.

The epidemiology of S. pneumoniae strains isolated in a nationwide manner from patients with meningitis in 1994 in The Netherlands was investigated. These strains (n = 153) were all found to be penicillin susceptible and were analyzed by serotyping, PBP typing, and RFEL typing. The results are shown in Fig. 1 and Table 2. The invasive isolates represented 31 serotypes: 1 (n = 3), 3 (n = 8), 4 (n = 3), 5 (n = 2), 6A (n = 7), 6B (n = 15), 7F (n = 7), 8 (n = 4), 9N (n = 4), 9V (n = 7), 10F (n = 2), 10A (n = 4), 11A (n = 2), 14 (n = 12), 15A (n = 1), 15C (n = 2), 16F (n = 2), 18F (n = 1), 18B (n = 2), 18C (n= 12), 19F (n = 18), 19A (n = 2), 22F (n = 1), 23F (n = 16), 23A (n = 1), 23B (n = 2), 24F (n = 3), 32A (n = 1), 33F (n = 5), 34 (n = 1), and 38 (n = 3).

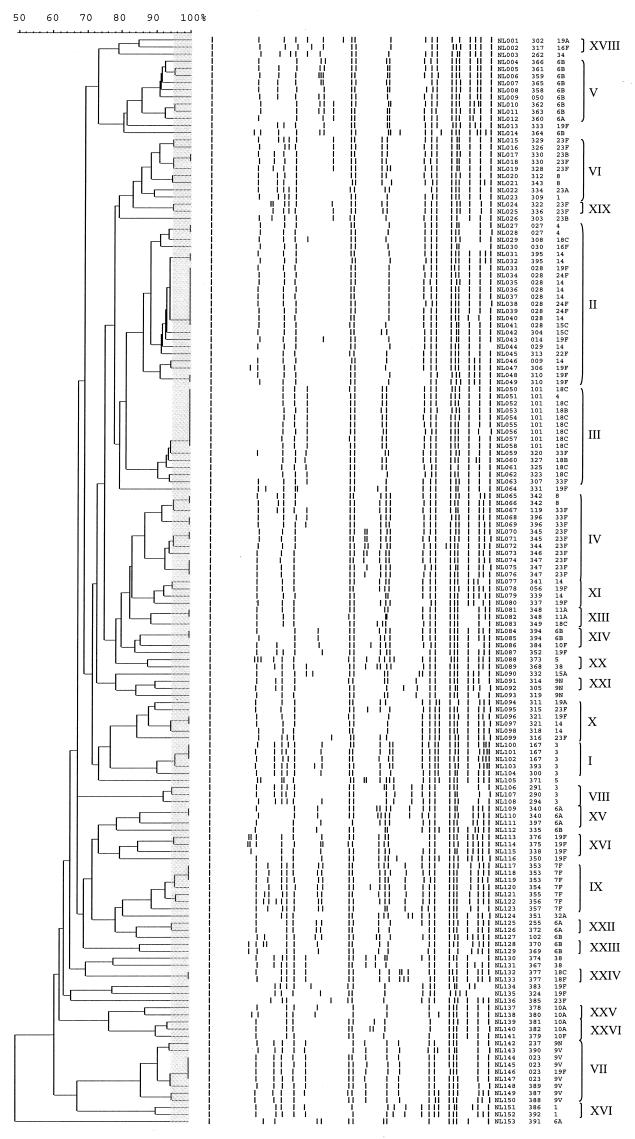

FIG. 1.

Genetic relatedness of 153 penicillin-susceptible invasive pneumococcal isolates, based on the RFEL banding patterns of the isolates. The country code (NL, The Netherlands), strain codes, RFEL types, and serotypes are depicted. Codes I to XI refer to genetic clades of pneumococcal strains; genetic clusters are indicated by a grey box in the dendrogram (for definitions, see Materials and Methods).

TABLE 2.

PBP genotypes of the 153 S. pneumoniae strains isolated from patients with meningitis in 1994 in The Netherlands

| PBP genotype | No. of strains | Serotype(s) of the strains |

|---|---|---|

| 02-02-03 | 67 | 21 distinct serotypes |

| 02-02-71 | 54 | 14 distinct serotypes |

| 02-02-02 | 22 | 10 distinct serotypes |

| 02-02-14 | 4 | Serotype 8 |

| 02-02-05 | 3 | Serotype 19F |

| 02-02-15 | 2 | Serotype 5 |

| 02-02-16 | 1 | Serotype 32A |

Seven distinct PBP genotypes displaying variations in the RFLP patterns of pbp2x only were observed. The PBP types 02-02-03, 02-02-71, and 02-02-02 occurred most frequently. In addition, all serotype 8 strains displayed PBP genotype 02-02-14, both serotype 5 strains displayed PBP genotype 02-02-15, and the single serotype 32A strain displayed PBP genotype 02-02-16. Finally, 3 of the 18 19F strains displayed PBP genotype 02-02-05 (Table 2).

RFEL analysis divided the 153 strains into 116 distinct RFEL types. These RFEL types represented 28 genetic clusters, i.e., strains showing over 95% genetic relatedness, and 73 RFEL types that were less than 95% related to other strains. RFEL clusters were represented by 80 strains (52%). The cluster size varied from two (19 clusters) to nine (2 clusters) strains. In addition, four clusters of three strains and three clusters of four strains were observed. RFEL types 28 (genetic clade II) and 101 (genetic clade III) were the most predominant types. They were each represented by nine isolates. Within genetic clusters, different serotypes were observed. Eight of the 28 RFEL clusters displayed two or more serotypes (Table 3). The strain collection could be divided into 25 genetic clades, i.e., strains with more than 85% RFEL homology. The genetic clades varied in size from 2 to 23 strains (Fig. 1). Comparison of penicillin-susceptible invasive strains with penicillin-nonsusceptible strains representing 193 distinct RFEL types present in the international data library and representing 16 countries (13) revealed no overlap in RFEL types between penicillin-susceptible strains and penicillin-non-susceptible strains.

TABLE 3.

RFEL clusters consisting of strains with different serotypes

| RFEL clustera (RFEL types) |

Serotypes (no. of strains) |

|---|---|

| A(28) | 14 (4), 15C (1), 19F (1), 24F (3) |

| B(101) | 4 (1), 18B (1), 18C (7) |

| C(23) | 9V (3), 19F (1) |

| D(328, 330) | 23F (2), 23B (1) |

| E(119, 342) | 8 (2), 33F (1) |

| F(56, 341) | 14 (1), 19F (1) |

| G(321) | 14 (1), 19F (1) |

| H(377) | 18F (1), 18C (1) |

For definition of RFEL clusters and RFEL types, see Materials and Methods.

Genetic relatedness within serotypes in The Netherlands.

The genetic relatedness of strains within the nine most predominant serotypes present in the collection was investigated. All strains of serotype 7F (n = 7) belonged to clade IX, and all strains of serotype 9V (n = 7) belonged to clade VII. Strains of serotype 3 (n = 8) belonged to two distinct genetic clades, I and VIII. Strains of serotype 14 (n = 12) represented three distinct genetic clades, III, X, and XI. Strains of serotypes 6B, 18C, and 23F were genetically more heterogeneous. However, most strains of serotypes 6B, 18C, and 23F belonged to one clade. Eight of the 15 serotype 6B strains belonged to clade V, 9 of the 12 serotype 18C strains belonged to clade III, and 7 of the 16 serotype 23F strains belonged to clade IV. Strains with serotypes 6A and 19F displayed the most heterogeneity in this collection of S. pneumoniae strains, as 7 serotype 6A strains were represented by 4 genetic clades and 18 serotype 19F strains were represented by 11 genetic clades (Fig. 1).

Genetic relatedness within serotype 3 isolates of distinct geographic origins.

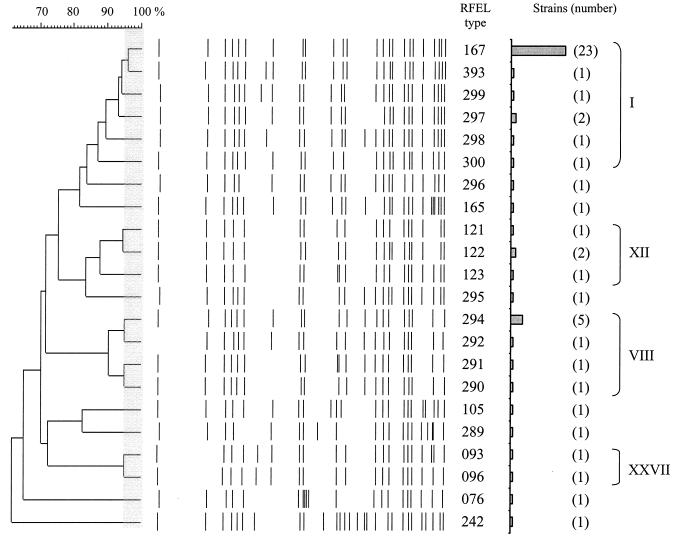

We investigated the molecular epidemiology of serotype 3 strains from The Netherlands (n = 8) and three additional countries: the United States (n = 27), Thailand (n = 9), and Denmark (n = 6). These 50 epidemiologically unrelated serotype 3 strains were characterized by RFEL analysis. Four distinct RFEL clades and seven RFEL types that were less than 85% related to other serotype 3 strains were observed among these strains (Fig. 2). The most predominant RFEL clade, I, represented 29 serotype 3 strains (58%). This RFEL clade was represented by 22 isolates from the United States, 2 isolates from Denmark, and 5 isolates from The Netherlands. RFEL cluster VIII was represented by eight strains (16%)—two American, three Danish, and three Dutch strains. RFEL clade XII was represented by four Thai isolates. In addition, two Thai isolates formed a Thai-specific clade. Thus, 43 strains shared RFEL types with at least one other strain (86%). Seven serotype 3 strains with RFEL types 296, 295, 165, 105, 289, 76, and 242 did not match the four genetic clades, and six of them did not match any of the 153 Dutch invasive strains representing 116 RFEL types and 31 serotypes. In contrast, the serotype 3 strain with RFEL type 105 was genetically related (90.9%) to a serotype 19F strain representing RFEL type 352.

FIG. 2.

Genetic relatedness of 50 penicillin-susceptible pneumococcal serotype 3 isolates, based on the RFEL banding patterns of the isolates. RFEL types are depicted. Codes I, VIII, XII, and XXVII refer to genetic clades of pneumococcal strains; genetic clusters are indicated by a grey box in the dendrogram (for definitions, see Materials and Methods). Bars represent the number of isolates per RFEL type.

The serotype 3 collection was also analyzed by PBP typing. PBP genotype 02–02–71 was invariably observed in the strains from the United States, Denmark, and The Netherlands. The Thai strains displayed three distinct PBP genotypes: 02–02–03 (n = 5), 02–02–71 (n = 3), and 09–02–71 (n = 1) (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Few studies have documented genotype analyses of penicillin-susceptible strains (12, 29) and of serotype-specific strains (9, 18). We investigated the epidemiological characteristics of 153 penicillin-susceptible S. pneumoniae strains isolated from patients with meningitis in The Netherlands in 1994. The isolates represented 31 serotypes. The most predominant serotypes were 19F, 23F, 6B, 18C, 14, 3, 6A, 7F, and 9V. Various investigators have reported the occurrence of horizontal transfer of capsular genes (2, 11–13). In Dutch penicillin-susceptible isolates, horizontal transfer of capsular genes has occurred frequently. A high frequency of capsular exchange has been reported in molecular epidemiological studies of penicillin-resistant isolates from many countries (12, 13). This is the first study suggesting the frequent occurrence of horizontal transfer of capsular genes among penicillin-susceptible isolates.

RFEL analysis revealed that 52% of the strains belonged to genetic clusters. The amount of genetic clustering was substantially lower among the penicillin-susceptible isolates than among the penicillin-nonsusceptible isolates in other studies (2, 5, 11–13, 25). A comparison of the penicillin-susceptible invasive isolates studied here with 193 penicillin-nonsusceptible strains representing 193 distinct RFEL types in the international data library and representing 16 countries revealed no overlap (12, 13).

The PBP genotypes 02–02–03, 02–02–71, and 02–02–02 were found most frequently. This observation corresponds with the PBP typing results for penicillin-susceptible pediatric carriage isolates in the U.S. population (30). Interestingly, four additional PBP genotypes (02–02–14, 02–02–15, 02–02–16, and 02–02–05) were identified for serotypes 8, 5, 32A, and 19F, respectively. The serotype specificity of the latter PBP genotypes suggests a divergence of the PBP genotypes before the origin of the capsular types 8, 5, 32A, and 19F.

The genetic relatedness within the specific pneumococcal serotypes was highly variable. RFEL genotypes of serotype 6A and 19F strains displayed high levels of heterogeneity; i.e., strains of these serotypes represented many RFEL types that belonged to many genetic clusters and genetic clades. In contrast, the RFEL genotypes of serotype 7F, 9V, 14, and 3 strains were found to be genetically related. Interestingly and consistent with our observations, Canadian penicillin-susceptible isolates of serotypes 3 and 7F were also more genetically related than isolates of other serotypes (18). Moreover, invasive penicillin-susceptible serotype 3 isolates from the United Kingdom also tended to be more closely related to each other than to isolates of other serotypes (9).

We focused on the molecular epidemiological characteristics of epidemiologically unrelated serotype 3 pneumococci and extended our serotype 3 collection with isolates from the United States, Thailand, and Denmark. RFEL analysis demonstrated that serotype 3 strains isolated in these countries displayed a strong degree of genetic relatedness: the vast majority of the strains represented two distinct RFEL clades. Furthermore, both genetic clades harbored isolates from three countries: the United States, Denmark, and The Netherlands. These observations indicate that two serotype 3 clones have been disseminated internationally. In addition, six Thai serotype 3 isolates belonged to two RFEL clades (clades XII and XXVII). The data suggest strong genetic homogeneity within the serotype 3 pneumococci and support the observations for Canada and the United Kingdom (9, 18). Interestingly, the Canadian serotype 3 strains displayed two distinct genotypes, and the majority of the epidemiologically nonrelated serotype 3 strains from the United Kingdom displayed two genotypes. Moreover, MLST analysis of serotype 3 strains isolated in six countries identified two major genetic clusters (M. C. Enright and B. G. Spratt, http://mlst.zoo.ox.ac.uk). Since the strains have been characterized by distinct typing methods, i.e., pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, MLST, and RFEL analysis, and since there is no overlap in the characterized strains, the genetic relatedness between the latter serotype 3 strains and the strains characterized in this study is currently unknown. The remaining six serotype 3 RFEL types each occurred once in our collection. Our observations suggest that these latter strains have been derived from horizontal transfer of the capsular type 3 gene locus to other pneumococcal genotypes.

PBP genotyping of the serotype 3 strains demonstrated limited variation in the pbp1a, pbp2b, and pbp2x genes. All serotype 3 strains from the United States, Denmark, and The Netherlands displayed PBP genotype 02–02–71. However, variation was demonstrated in the Thai serotype 3 isolates. PBP type 09–02–71 was represented by a single Thai isolate. This PBP type was also specific for the penicillin-susceptible phenotype, as there was no overlap with penicillin-nonsusceptible isolates from 16 countries (13).

In conclusion, pneumococcal strains belonging to serotype 3 display limited genetic heterogeneity despite the lack of epidemiological relatedness. We hypothesize that this serotype has recently evolved or has remained unchanged for a prolonged period. The few serotype 3 isolates not belonging to the main clusters are presumably derived from horizontal transfer of capsular genes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jay Butler (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.), Gregory C. Gray (Emerging Illness Division, Naval Health Research Center, San Diego, Calif.), Jørgen Henrichsen (Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark), Surang Dejsirilert (National Institute of Health, Department of Medical Sciences, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand), and Lodewijk Spanjaard (Department of Medical Microbiology, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for providing us with pneumococcal isolates.

The study was sponsored by the Sophia Foundation for Medical Research, Rotterdam, The Netherlands (grants 183, 217, and 268), the NWO (grant SGO-inf. 005), and Public Health Service grant AI28457 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso DeVelasco E, Verheul A F, Verhoef J, Snippe H. Streptococcus pneumoniae: virulence factors, pathogenesis, and vaccines. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:591–603. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.591-603.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes D M, Whittier S, Gilligan P H, Soares S, Tomasz A, Henderson F W. Transmission of multidrug-resistant serotype 23F Streptococcus pneumoniae in group day care: evidence suggesting capsular transformation of the resistant strain in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:890–896. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coffey T J, Dowson C G, Daniels M, Zhou J, Martin C, Spratt B G, Musser J M. Horizontal transfer of multiple penicillin-binding protein genes, and capsular biosynthetic genes, in natural populations of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2255–2260. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffey T J, Enright M C, Daniels M, Wilkinson P, Berron S, Fenoll A, Spratt B G. Serotype 19A variants of the Spanish serotype 23F multiresistant clone of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb Drug Resist. 1998;4:51–55. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1998.4.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dejsirilert S, Overweg K, Sluijter M, Saengsuk L, Gratten M, Ezaki T, Hermans P W. Nasopharyngeal carriage of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae among children with acute respiratory tract infections in Thailand: a molecular epidemiological survey. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1832–1838. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1832-1838.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowson C G, Hutchison A, Spratt B G. Extensive re-modelling of the transpeptidase domain of penicillin-binding protein 2B of a penicillin-resistant South African isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:95–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enright M C, Spratt B G. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology. 1998;144:3049–3060. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Facklam R R, Washington J A., II . Streptococcus and related catalase-negative gram-positive, cocci. In: Balows A, Hausler W J, Herrmann K L, Isenberg H D, Shadomy H J, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1991. pp. 238–257. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall L M, Whiley R A, Duke B, George R C, Efstratiou A. Genetic relatedness within and between serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the United Kingdom: analysis of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and antimicrobial resistance patterns. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:853–859. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.853-859.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henrichsen J. Six newly recognized types of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2759–2762. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2759-2762.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hermans P W, Sluijter M, Dejsirilert S, Lemmens N, Elzenaar K, van Veen A, Goessens W H, de Groot R. Molecular epidemiology of drug-resistant pneumococci: towards an international approach. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:243–251. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hermans P W, Sluijter M, Elzenaar K, van Veen A, Schonkeren J J, Nooren F M, van Leeuwen W J, de Neeling A J, van Klingeren B, Verbrugh H A, de Groot R. Penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in The Netherlands: results of a 1-year molecular epidemiologic survey. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1413–1422. doi: 10.1086/516474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hermans P W M, Overweg K, Sluijter M, de Groot R. Penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae: an international molecular epidemiological study. In: Tomasz A, editor. Streptococcus pneumoniae: molecular biology and mechanisms of disease. New York, N.Y: Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., Publishers; 2000. pp. 457–466. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hermans P W M, Sluijter M, Hoogenboezem T, Heersma H, van Belkum A, de Groot R. Comparative study of five different DNA fingerprint techniques for molecular typing of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1606–1612. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1606-1612.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsueh P R, Wu J J, Hsiue T R. Invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infection associated with rapidly fatal outcome in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 1996;95:364–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klugman K P. Pneumococcal resistance to antibiotics. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:171–196. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.2.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawrenson J B, Klugman K P, Eidelman J I, Wasas A, Miller S D, Lipman J. Fatal infection caused by multiply resistant type 3 pneumococcus. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1590–1591. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.8.1590-1591.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louie M, Louie L, Papia G, Talbot J, Lovgren M, Simor A E. Molecular analysis of the genetic variation among penicillin-susceptible and penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes in Canada. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:892–900. doi: 10.1086/314664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin D R, Brett M S. Pneumococci causing invasive disease in New Zealand, 1987-94: serogroup and serotype coverage and antibiotic resistances. N Z Med J. 1996;109:288–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mufson M A, Kruss D M, Wasil R E, Metzger W I. Capsular types and outcome of bacteremic pneumococcal disease in the antibiotic era. Arch Intern Med. 1974;134:505–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munoz R, Coffey T J, Daniels M, Dowson C G, Laible G, Casal J, Hakenbeck R, Jacobs M, Musser J M, Spratt B G, Tomasz A. Intercontinental spread of a multidrug-resistant clone of serotype 23F Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:302–306. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munoz R, Musser J M, Crain M, Briles D E, Marton A, Parkinson A J, Sorensen U, Tomasz A. Geographic distribution of penicillin-resistant clones of Streptococcus pneumoniae: characterization by penicillin-binding protein profile, surface protein A typing, and multilocus enzyme analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:112–118. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nesin M, Ramirez M, Tomasz A. Capsular transformation of a multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:707–713. doi: 10.1086/514242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nielsen S V, Henrichsen J. Capsular types of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated from blood and CSF during 1982-1987. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:794–798. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.5.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Overweg K, Hermans P W M, Trzcinski K, Sluijter M, de Groot R, Hryniewicz W. Multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Poland: identification of emerging clones. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1739–1745. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1739-1745.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romesburg H C. Cluster analysis for researchers. Malabar, Fla: Krieger; 1990. pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott J A, Hall A J, Dagan R, Dixon J M, Eykyn S J, Fenoll A, Hortal M, Jette L P, Jorgensen J H, Lamothe F, Latorre C, Macfarlane J T, Shlaes D M, Smart L E, Taunay A. Serogroup-specific epidemiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae: associations with age, sex, and geography in 7,000 episodes of invasive disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:973–981. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.6.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sibold C, Wang J, Henrichsen J, Hakenbeck R. Genetic relationships of penicillin-susceptible and -resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains isolated on different continents. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4119–4126. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4119-4126.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sluijter M, Faden H, de Groot R, Lemmens N, Goessens W H F, van Belkum A, Hermans P W M. Molecular characterization of pneumococcal nasopharynx isolates collected from children during their first years of life. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2248–2253. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.8.2248-2253.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sneath, P. H. A., and R. R. Sokal. Numerical taxonomy, p. 131–132. Freeman, San Fransisco, Calif.

- 32.van Belkum A, Sluijter M, de Groot R, Verbrugh H, Hermans P W M. Novel BOX repeat PCR assay for high-resolution typing of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1176–1179. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1176-1179.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Steenbergen T J, Colloms S D, Hermans P W M, de Graaff J, Plasterk R H. Genomic DNA fingerprinting by restriction fragment end labeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5572–5576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]