Abstract

Effective control of severe immune-related adverse events, including cytokine release syndrome (CRS), is essential for the success of immunotherapy. We present a case of a granulocyte colony-stimulating factor–producing pleomorphic lung carcinoma treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab which developed CRS and severe immune-related pneumonitis. The effect of immunotherapy was heterogeneous; gastric metastasis was eliminated, but the pulmonary lesion had primary resistance. Steroid and tocilizumab were successful in controlling CRS, but additional infliximab was necessary to control pneumonitis. To control immune-related adverse events, it is important to choose immunosuppressive agents to the specific target organ and inflammatory cells.

Keywords: Cytokine release syndrome, Nivolumab, Ipilimumab, Pleomorphic carcinoma, Immunosuppressive agent, Case report

Introduction

Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) is a potentially life-threatening toxicity that has been observed after the administration of immune-based therapies for cancer, including chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy and immune checkpoint blockade treatments. CRS occurs either in the hyperacute phase, minutes to hours after the administration of these drugs, or in some days to 2 weeks after the proliferation of the administered T-cells.1 Here, we present a case of a patient with pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab who developed CRS with tumor progression. Tocilizumab, an antihuman interleukin (IL)-6 monoclonal antibody, was effective in controlling CRS, whereas infliximab, an antihuman tumor necrosis factor α monoclonal antibody, was necessary for controlling complicated pneumonitis. In the control of concurrent immune-related adverse events (irAEs), it may be necessary to use different immunosuppressive agents for different organs and inflammatory cells.

Case Presentation

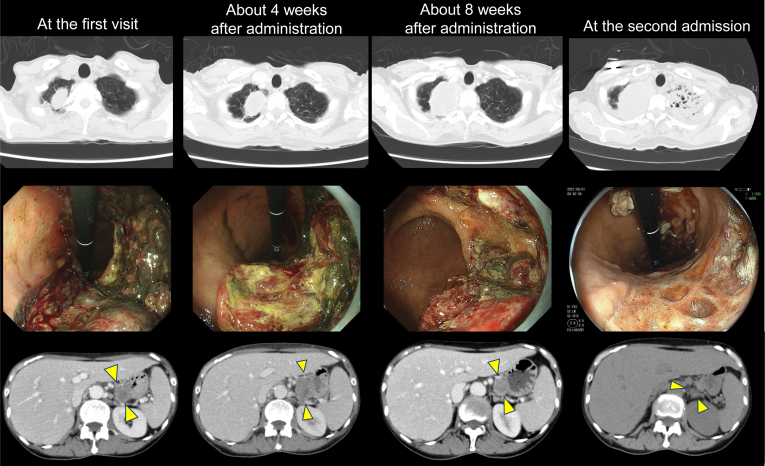

A 64-year-old Japanese female, who is a 45 pack-year smoker, presented with fatigue and lightheadedness associated with severe anemia and leukocytosis (d 1). Upper endoscopy results revealed a bleeding lesion in the stomach (Fig. 1), and computed tomography scan results revealed a pulmonary mass in the right upper lobe. Histopathologic analysis suggested granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)–producing pleomorphic carcinoma (Fig. 1). She was finally diagnosed with having pleomorphic carcinoma of the lung with clinical T2aN0M1b, stage IVB with no targetable driver mutations, and with a programmed cell death-ligand 1 tumor proportion score of 60%. Nivolumab (360 mg every 3 wks) plus ipilimumab (1 mg/kg every 6 wks) was administered on day 21, and 20 mg of prednisolone was given for grade 2 immune-related skin rash on day 47. The bleeding gastric metastasis had a tendency to shrink, whereas the pulmonary lesion had primary resistance (Fig. 2).

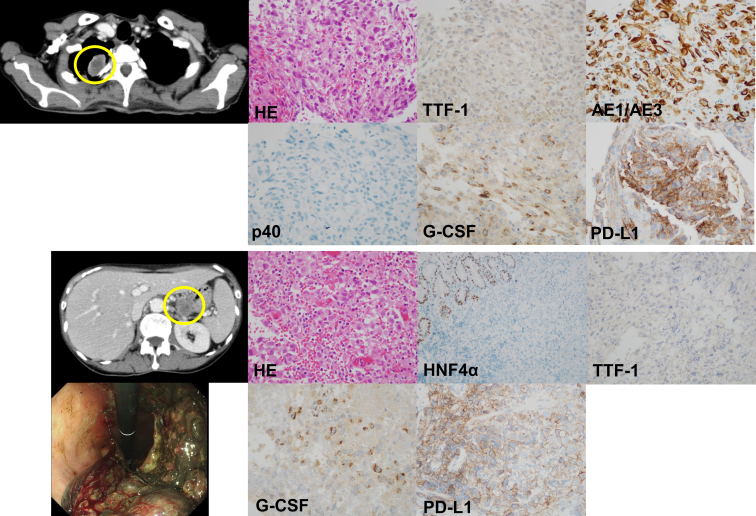

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemistry of tumors from the pulmonary and gastric lesions. The upper column reveals the immunohistochemistry analysis of the pulmonary tumor (yellow circle). HE stain revealed poorly differentiated polymorphic cells with scattered spindle cells. The immunohistochemical staining revealed that the tumor cells are negative for TTF-1 and p40 and positive for AE1/AE3 and G-CSF. The PD-L1 TPS using the 22C3 pharmDx assay is 60%. The lower column reveals the immunohistochemistry analysis of the gastric tumor (yellow circle). Upper endoscopy revealed a bleeding gastric lesion. HE staining revealed poorly differentiated polymorphic cells with scattered spindle cells. The immunohistochemical staining revealed that the tumor cells are negative for HNF4α and TTF-1 and positive for G-CSF. The normal gastric epithelium is positive for HNF4α. PD-L1 TPS using the 22C3 is 60% similar to the pulmonary tumor. G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; HE, hematoxylin and eosin; HNF4α, hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; TPS, tumor proportion score; TTF-1, thyroid transcription factor-1.

Figure 2.

Serial images of the tumor. The upper column reveals serial images of chest CT scans. The primary pulmonary lesion was gradually increasing. CT scan at the second admission revealed infiltration in the left lung field. The middle column reveals serial images of upper endoscopy. The bleeding gastric lesion was gradually decreasing. The lower column reveals decreasing gastric lesion (yellow arrow heads) in abdominal CT scans. The three images in the same row were not taken on the same day but were taken at approximately the same times: at the first visit, approximately 4 weeks after administration, approximately 8 weeks after administration, and at the second admission. CT, computed tomography.

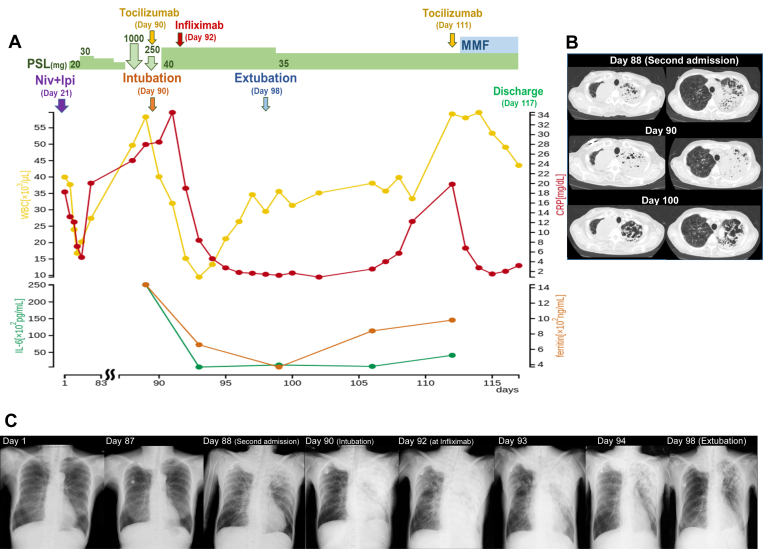

On day 88, she experienced sudden nausea and lightheadedness and was rushed to our hospital with signs of shock. An infiltrative shadow emerged in the left upper lobe (Fig. 3B), and procalcitonin was increased to 70.29 ng/mL. Test result for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 based on reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction using her nasal swab was negative. She was admitted to the intensive care unit, and empirical administration of broad-spectrum antibacterial agent was started with vasopressor agents. No infectious organisms were detected in the sputum and peripheral blood culture. With suspicion of CRS, we administered steroid pulse and tocilizumab (8mg/kg) therapy, which resulted in an immediate increase in blood pressure. Nevertheless, the infiltrative shadow rapidly progressed, thus requiring ventilation management. The serum IL-6 and ferritin levels at admission were 25,100 pg/mL and 1440.8 ng/mL, respectively (Fig. 3A). Although tocilizumab was administered for CRS, there was only temporary improvement in chest infiltration (Fig. 3C), and oxygenation worsened. Changes in chest radiograph images and the ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen from the administration of tocilizumab to the administration of infliximab (5mg/kg) are illustrated in Supplementary Figure 1. Because the effect of tocilizumab was considered to be limited and the oxygen toxicity owing to high oxygen concentration was concerned, infliximab was administered on day 92 after the investigation of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Thereafter, the infiltrative shadow rapidly disappeared within 1 week, and the patient was successfully weaned from mechanical ventilation (Fig. 3A–C). After leaving the intensive care unit, the patient had signs of CRS again, was treated with tocilizumab, and was discharged on day 117 with mycophenolate mofetil. After 2 weeks of discharge, unfortunately she died at home owing to rapid tumor progression.

Figure 3.

Clinical course and serial chest images. (A) The first visit was defined as day 1, and the course was followed from the second admission to the discharge on day 117. (B) Serial chest images from the second admission to extubation. The primary tumor in the right lung field was gradually increasing. The left infiltrative shadow was exacerbated from day 88 to day 90 and gradually subsided after infliximab administration from day 90 to day 100. The residual lung cavitated as a result of severe inflammation on day 100. (C) Serial chest radiograph images throughout clinical course. CRP, c-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; Ipi, ipilimumab; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; Niv, nivolumab; PSL, prednisolone; WBC, white blood cell.

Discussion

The patient developed CRS and severe immune-related pneumonitis along with tumor progression approximately 3 months after immunotherapy. The CRS improved with high-dose steroids and tocilizumab, but infliximab was necessary to control pneumonitis. In the management of severe irAEs across multiple organs, the control of immunoinflammatory cells in each organ may be required.2 Although immunotherapy was successful in priming host immune cells, excessive stimulation by primary tumor progression may have caused these irAEs.

Duodenal metastasis of lung cancer is rare, accounting for 0.2% to 1.7% of cases.3 Metastases from pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma have occasionally been reported.3, 4, 5 In this case, lung and stomach biopsies were performed respectively, and it was diagnosed as gastric metastasis of pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma because of the identical histologic type, high programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression, and the same rare G-CSF–producing tumor (Fig. 1).

Tumor-derived G-CSF possibly contributed to the development of severe irAEs.6 Because immunotherapy was ineffective in the primary lung lesion, G-CSF stimulation continued as inferred from the peripheral white blood cell count and C-reactive protein elevation (Fig. 3A). CRS has been reported to occur relatively early after immunotherapy.1,7 Nevertheless, the onset of CRS in the present case was delayed possibly owing to its association with tumor growth. The use of G-CSF receptor blocker8 for G-CSF–producing tumors may reduce the risk of irAE development in patients with the tumors.

CRS is recommended to be primarily managed with tocilizumab.1 The symptoms associated with CRS in this case were nausea, severe hypotension, and respiratory failure.1,7 Although the blood pressure immediately responded to steroid pulse therapy, the infiltrative shadow in the lung field did not improve, and tocilizumab was administered considering CRS. Within 2 days, expansion of the pulmonary infiltrative shadow and deterioration of oxygenation were observed (Supplementary Fig. 1). The effect of tocilizumab for pneumonitis was thus deemed to be limited. Additional infliximab was administered after investigation of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid revealed numerous neutrophils instead of lymphocytes with no infectious organisms. Tocilizumab has been found to be effective against CRS and may take several days to be effective.9 It is also reported to be effective against immune checkpoint inhibitor-related pneumonitis.10 In this case, because the infiltrative shadow in the lung field increased and the partial pressure of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen ratio decreased day by day after administration of tocilizumab (Supplementary Fig. 1), infliximab was additionally administered. There was a report that infliximab was effective for steroid-refractory immune checkpoint inhibitor–related pneumonia,11,12 and infliximab seemed to be a promising alternative to tocilizumab. It may be necessary to use different immunosuppressive agents depending on the irAE organ and the immune cell type, that is, the main cause of inflammation.2 Unfortunately, we were not able to measure cytokines other than IL-6 in this case, but the measurement of other cytokines including tumor necrosis factor α may further guide the use of immunosuppressive agents.

Conclusion

The development of CRS and severe immune-related pneumonitis in the present case may have been due to G-CSF produced from the tumor and the unleashed immune cells, which were further stimulated by tumor progression. We successfully controlled CRS with steroid and tocilizumab, and pneumonitis with infliximab. To control irAEs, it is important to choose immunosuppressive agents properly according to the specific organ and immune-inflammatory cells.

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement

Kei Kunimasa: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - original draft.

Takako Inoue: Investigation, Writing - review and editing.

Katsunori Matsueda, Takahisa Kawamura, Motohiro Tamiya, Kazumi Nishino: Investigation.

Toru Kumagai: Supervision.

Acknowledgments

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Kunimasa reports receiving honoraria for lecture from AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharma, and Novartis. Dr. Nishino reports receiving a grant from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim and honoraria for lecture from Chugai Pharma, AstraZeneca, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly Japan, Roche Diagnostics, Novartis, Pfizer, and Merck. Dr. Tamiya reports receiving grants from Ono Pharmaceutical, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Boehringer Ingelheim and honoraria for lecture from Taiho Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, Asahi Kasei Pharmaceutical, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Kumagai reports receiving grants from Ono Pharmaceutical, Merck Sharp & Dohme K.K., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., AstraZeneca K.K., Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Merck Serono Co., Ltd., Pfizer Japan Inc., Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Novartis Pharma K.K., AbbVie GK., Delta-Fly Pharma, Inc., and The Osaka Foundation for The Prevention of Cancer and Life-style related Diseases (Public Interest Incorporated Foundation) and personal fees from Ono Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca K.K., Taiho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Merck Sharp & Dohme K.K., Teijin Pharma Limited, Novartis Pharma K.K., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Pfizer Inc., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and Bristol-Myers Squibb K.K. The remaining authors have no conflict of interest.

Cite this article as: Kunimasa K, Inoue T, Matsueda K, et al. Cytokine release syndrome and immune-related pneumonitis associated with tumor progression in a pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab treatment: a case report. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2021;3:100272.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of the JTO Clinical and Research Reports at www.jtocrr.org and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtocrr.2021.100272.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Santomasso B.D., Nastoupil L.J., Adkins S., et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:3978–3992. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esfahani K., Elkrief A., Calabrese C., et al. Moving towards personalized treatments of immune-related adverse events. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17:504–515. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-0352-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taira N., Kawabata T., Gabe A., et al. Analysis of gastrointestinal metastasis of primary lung cancer: clinical characteristics and prognosis. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:2399–2404. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsuda M., Kai Y., Harada S., Suzuki K., Hontsu S., Muro S. Duodenal metastasis of pulmonary pleomorphic carcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14:1511–1515. doi: 10.1159/000519664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koh H., Chiyotani A., Tokuda T., et al. Pleomorphic carcinoma showing rapid growth, multiple metastases, and intestinal perforation. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;20(suppl):669–673. doi: 10.5761/atcs.cr.13-00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsukane R., Watanabe H., Minami H., et al. Continuous monitoring of neutrophils to lymphocytes ratio for estimating the onset, severity, and subsequent prognosis of immune related adverse events. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1324. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79397-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee D.W., Gardner R., Porter D.L., et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of cytokine release syndrome. Blood. 2014;124:188–195. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-552729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehta P., Porter J.C., Manson J.J., et al. Therapeutic blockade of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor in COVID-19-associated hyperinflammation: challenges and opportunities. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:822–830. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30267-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Price C.C., Altice F.L., Shyr Y., et al. Tocilizumab treatment for cytokine release syndrome in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019: survival and clinical outcomes. Chest. 2020;158:1397–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ando H., Suzuki K., Yanagihara T. Insights into potential pathogenesis and treatment options for immune-checkpoint inhibitor-related pneumonitis. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1484. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9101484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martins F., Sykiotis G.P., Maillard M., et al. New therapeutic perspectives to manage refractory immune checkpoint-related toxicities. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:e54–e64. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30828-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ortega Sanchez G., Jahn K., Savic S., Zippelius A., Läubli H. Treatment of mycophenolate-resistant immune-related organizing pneumonia with infliximab. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:85. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0400-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.