Abstract

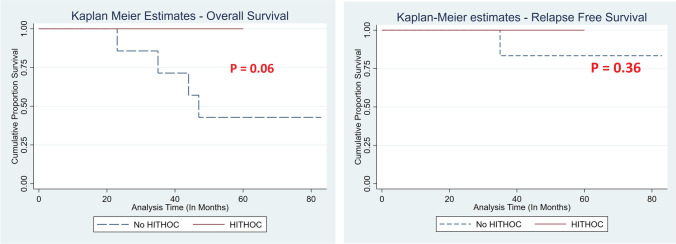

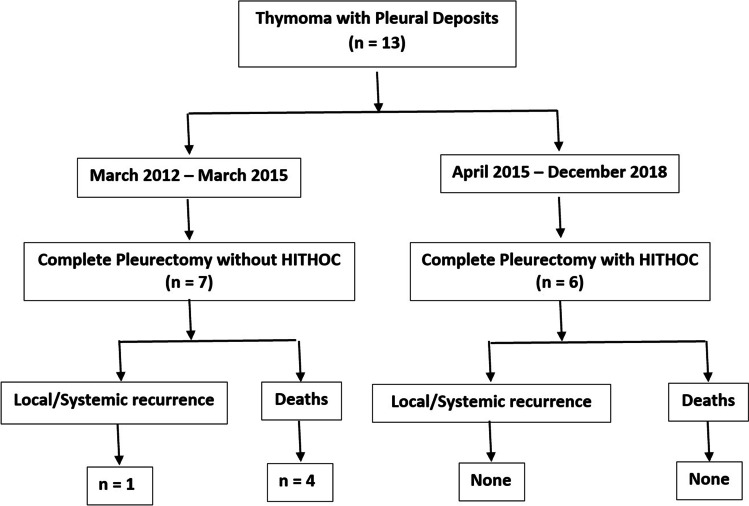

This study was aimed at evaluating the safety and efficacy of hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy in patients with Masaoka stage IVA thymoma. This is a retrospective comparative analysis between two groups of patients who were operated for Masaoka stage IVA thymoma. One group underwent complete parietal pleurectomy whereas other group received hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy after complete pleurectomy. An analysis of all perioperative variables, complications and survival was carried out. A total of 13 patients had stage IVA disease during the study period. Initial 7 patients (March 2012–March 2015) underwent complete parietal pleurectomy, whereas next 6 patients (April 2015–December 2018) had undergone HITHOC after complete parietal pleurectomy. Both groups are comparable in terms of age, co-morbidities, tumor size and duration of symptoms. The duration of surgery and intra-operative blood loss, postoperative ICU stay, duration of ICD and total hospital stay was similar between two groups. The total number of post-operative complications was higher in HITHOC group (5 vs 2), however non-significant (p = 0.10). The median follow-up duration was 63 months in no HITHOC group and 49.5 months in HITHOC group. There was no peri-operative mortality. The overall survival (P = 0.06) and relapse-free survival (P = 0.36) were not significantly different in the both groups. Hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy is a safe and feasible modality with no added morbidity or mortality. Multi-institutional prospective studies with large number of patients are required to accurately assess survival benefit.

Keywords: Masaoka-Koga stage IVA thymoma, Pleurectomy, HITHOC, Hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy

Introduction

Thymoma is the most common neoplasm of anterior mediastinum that arises from thymic epithelial cells [1]. Although most of the tumors are indolent in nature, few behave aggressively and can metastasize to the pleura (Masaoka-Koga stage IVA) [2]. Complete surgical resection with clear margins is the standard approach for management of resectable thymoma [3–5]. However, the treatment of thymoma with pleural metastasis is a subject of controversy. Pleural metastases can be present at initial presentation with thymoma or present as a recurrent disease after thymoma resection [6–8].

Presence of pleural metastasis is an advanced disease, which is usually not amenable to upfront surgical resection. Therefore, multimodality therapy in the form of induction chemotherapy (3–4 cycles), radical surgical resection followed by adjuvant chemo ± radiotherapy has been widely studied, with reduced local recurrence rates and improved survival [9, 10]. In stage IVA thymoma also, like in other stages of thymoma, complete surgical resection is a good prognostic factor for survival and should be always aimed at [11]. To achieve radical excision, various modalities like local pleural resection, total pleurectomy [12] and even pleuro-pneumonectomy have been attempted [13]. However, there is always a possibility of microscopic residual disease remining in the thoracic cavity which will predispose to local recurrence. Therefore, hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy (HITHOC) was attempted to improve the local tumor control, after local or total pleurectomy or even pleuro-pneumonectomy [14]. The rationale of this procedure was to expose any residual microscopic tumor cells to high local concentrations of chemo-therapeutic agent and the hyperthermia, which is expected to kill them, precluding the possibility of future recurrences. The aim of this pilot study was to evaluate the feasibility, safety and any oncological benefits of hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy after total pleurectomy/pleuro-pneumonectomy compared to surgery alone in thymoma patients with Masaoka-Koga stage IVA disease.

Material and Methods

Study Population

This is a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained data of the clinical experience from March 2012 to December 2018 at Department of Thoracic Surgery in a tertiary referral centre in New Delhi, India. A total of 13 patients, surgically treated for thymoma with pleural metastasis (Masaoka-Koga IVA), were included in the study. Complete pleurectomy only was done for patients presented to us between March 2012 and March 2015, whereas HITHOC was also added to this treatment for patients who presented between April 2015 and December 2018. Patients who had undergone resection for thymoma in the past and came with pleural recurrence were excluded from the study to maintain the homogeneity of the study population. Institutional ethical board approval was taken.

Pre-operative Evaluation

Evaluation of general condition—included a detailed history, physical examination, co-morbidity evaluation and blood investigations such as complete blood count, renal function tests and coagulation profile.

Oncological evaluation

The disease extent was assessed by contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of chest.

In patients with evidence of pleural metastasis in the CT scan, PET (positron emission tomography)-CT scan was advised to rule out distant metastasis.

Biopsy of the mass was done under guidance of either computed tomography/ultrasonography.

All thymoma patients with evidence of pleural nodules were advised neo-adjuvant chemotherapy (NACT). Three to four cycles of cyclophosphamide, cisplatin and doxorubicin were used in standard dosages and the treatment response was categorized into complete remission (CR), partial response (PR) or progressive disease.

If the pleural nodules were detected intra-operatively, then adjuvant chemotherapy was administered after surgical resection.

Myasthenia gravis (MG) was always ruled out by anti-acetylcholinesterase antibody levels in the blood and a repetitive nerve stimulation test.

-

3.

Functional evaluation—Predictive post-operative lung function was assessed using pulmonary function tests (PFT), diffusion capacity (DLCO) and ventilation/perfusion scan (selectively in patients likely to require pneumonectomy). Cardiac function was assessed using electrocardiography and transthoracic 2-dimensional echocardiography in all patients.

Surgical Technique

All patients with pleural metastasis were operated by mid-sternotomy approach. We always followed the dictum “No-touch technique”, where the tumor mobilization was always performed by en-bloc removal of all invaded structures. No attempt was ever made to separate the structures adherent to the tumor, but resected en-bloc with the tumor (When in doubt, take it out). All efforts were made to achieve R0 resection in all cases.

Parietal pleural nodules—In case of presence of tumor nodules over the parietal pleura, complete parietal pleurectomy was performed.

Visceral pleural nodules—In patients with deposits over visceral pleura, wedge resection was performed when nodules were localized over a single area. Pleuro-pneumonectomy was the treatment option, in case of extensive, diffuse visceral as well as parietal pleural deposits with lung involvement and are too numerous to remove individually.

Diaphragmatic deposits—In cases of tumor deposits with diaphragm involvement, full thickness resection of the same with 1-cm circumferential margin was performed and the resultant defect in the diaphragm was closed primarily.

Hyperthermic Intrathoracic Chemotherapy (HITHOC) Protocol

In the study subjects, the HITHOC protocol was used additionally after surgical resection. After radical thymoma resection with complete parietal pleurectomy with/without diaphragmatic resection and repair, complete hemostasis was achieved and ipsilateral lung was collapsed. Two pleural drains (32 F) were placed, one directed at the apex and another placed at the base and the chest was closed. HITHOC was performed using heart–lung machine. The target intrathoracic temperature was 41–43 °C. The chemotherapeutic agent used was cisplatin, at a dose of 130–150 mg/m2 body surface area. The total duration of perfusion was 60 min. The primer solution used was Plasma-Lyte A™ (Baxter Healthcare, USA) or Ringer lactate in volumes of 2–2.5 l. The “outflow” of the heart–lung machine was connected to apical chest tube and “inflow” was connected to basal chest tube. Initially, the chest cavity was filled with primer solution and the temperature was gradually raised to 42 °C. After achieving the desired temperature, cisplatin solution was infused into the primer solution and was circulated at the same temperature for 60 min. During this process, patients were carefully monitored for any hemodynamic instabilities and cardiac arrhythmias. After completion of 60 min, the thoracic cavity was re-perfused with normal saline solution for 10 min to drain out any residual cisplatin.

Postoperative Care

All patients were shifted to ICU for overnight observation. We preferred to keep these patients on ventilator overnight and were extubated on 1st post-operative day. Oral nutrition and aggressive chest physiotherapy were initiated from the first postoperative day. Renal functions were regularly monitored. Effective pain relief was achieved by epidural analgesia supplemented by intravenous medications. The chest drains were removed when there was no air leak and the drainage was not purulent/haemorrhagic and was less than 100 ml in 24 h. Duration of chest tube, hospital stay and other complications were monitored and recorded.

Adjuvant Therapy

All patients were given adjuvant radiotherapy. The dose of adjuvant radiotherapy was between 45 and 50 Gy for R0 resections, and 54 Gy for R1 resections including ipsilateral hemithorax. Patients who were not given induction/neo-adjuvant chemotherapy were given adjuvant radiotherapy.

Follow-up

First follow‐up was done at 1 month from discharge. Further follow-up protocol included CECT chest every 6 months for 2 years and then annually.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using Stata 14.0 software (StataCorp LLC, TX, USA). Continuous variables were presented as mean with standard error (SE). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies with percentages. Student’s T test was used to compare the normally distributed continuous variables, whereas Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare non-normal distribution continuous variables. Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare nominal categorical data. Survival was assessed by the Kaplan–Meier method. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of death due to any cause. Relapse-free survival (DFS) was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of local/systemic recurrence; however, death was not included. Differences between survival rates were assessed by using log-rank test. For all statistical tests, a p value less than 0.05 was taken as “clinically significant”.

Results

Complete Pleurectomy With HITHOC vs Complete Pleurectomy Without HITHOC

Demographic Characteristics

A total of 13 patients had stage IVA disease, in which first 7 patients (March 2012–March 2015) underwent complete parietal pleurectomy, whereas rest 6 patients (April 2015–December 2018) had undergone HITHOC after complete parietal pleurectomy. Both groups were comparable according to age, sex ratio, comorbidities, tumor diameter and associated myasthenia gravis. Most common presenting symptoms were weight loss followed by non-specific chest pain in both the groups. Predominantly, the pleural deposits were on left side. The duration of symptoms was also no different between two groups (P = 0.79) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic details of the HITHOC group and no HITHOC group

| Characteristics | Complete pleurectomy + HITHOC (n = 6) | Complete pleurectomy (no HITHOC) (n = 7) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 45.7 ± 17.8 | 49.7 ± 15.9 | 0.67 |

| Male: female | 5:1 | 5:2 | |

| No. of patients having comorbidities | 4 | 4 | 1.0 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 2 | 3 | –– |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 | 0 | |

| Hypothyroidism | 0 | 1 | |

| Bronchial asthma | 1 | 0 | |

| Presenting symptoms | |||

| Chest pain | 2 | 3 | –– |

| Breathlessness | 0 | 1 | |

| Weight loss | 4 | 3 | |

| Duration of symptoms (in months) | 3.4 ± 3.1 | 3.9 ± 3.6 | 0.79 |

| Mean tumor diameter (in cm) | 5.6 ± 3.9 | 5.9 ± 3.1 | 0.87 |

| Myasthenia gravis | 4 | 5 | 1.0 |

| Side of the disease | |||

| Right | 2 | 1 | |

| Left | 4 | 6 | |

Peri-operative variables

Duration of surgery and intra-operative blood loss were slightly higher in HITHOC group; however, the difference did not reach the statistical significance (P = 0.21 and P = 0.45). Pericardium was resected in all patients in view of invasion. No difference was observed between the two groups regarding variables such as postoperative ICU stay, duration of ICD and total hospital stay. The total number of post-operative complications was higher in HITHOC group (5 vs 2), however non-significant (p = 0.10). Atrial fibrillation (n = 2), wound infection (n = 1), prolonged air leak (n = 1) and myasthenia aggravation (n = 1) were the complications in HITHOC group. One patient had elevated serum creatinine in the postoperative period, however did not require any hemodialysis. In the other group, atrial fibrillation (n = 1) and myasthenic aggravation (n = 1) were the only complications. Atrial fibrillation was managed with intravenous cordarone therapy, wound infection was managed with would exploration and vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) device application, whereas myasthenia aggravation was treated with elevation of anti-myasthenic medications (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of perioperative variables between HITHOC group and no HITHOC group

| Characteristics | Complete pleurectomy + HITHOC (n = 6) | Complete pleurectomy (no HITHOC) (n = 7) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additional structures resected | –– | ||

| Pericardium | 6 | 7 | |

| Left brachiocephalic vein | 1 | 0 | |

| Wedge of lung | 1 | 2 | |

| Whole lung | 1 | 1 | |

| Diaphragm | 2 | 3 | |

| Mean duration of surgery (in minutes) | 338 ± 110 | 260 ± 102 | 0.21 |

| Mean intra-operative blood loss (In ml) | 119 ± 45 | 101 ± 38 | 0.45 |

| Postoperative variables | |||

| Mean duration of postoperative ICU stay (in days) | 1.15 ± 0.9 | 1.02 ± 0.7 | 0.77 |

| Postoperative ICD duration (in days) | 6.4 ± 2.1 | 5.9 ± 1.8 | 0.65 |

| Mean hospital stay (in days) | 7.1 ± 4.9 | 7.3 ± 4.1 | 0.93 |

| Complications | |||

| Number of overall complications | 5 | 2 | 0.10 |

| Prolonged air leak (> 5 days) | 1 | 0 | |

| Wound infection (%) | 1 | 0 | |

| Cardiac arrhythmias (%) | 2 | 1 | |

| Post-operative myasthenia aggravation (%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Renal failure requiring hemodialysis | 0 | 0 | |

| Peri-operative mortality | 0 | 0 | |

|

Mortality on follow-up < 3 months < 12 months < 24 months < 36 months < 48 months |

0 0 0 0 0 0 |

4 0 0 1 1 2 |

0.06 |

Mortality

There was no peri-operative mortality in either group (< 90 days). The median follow-up duration was 49.5 months in HITHOC group and 63 months in complete parietal pleurectomy without HITHOC group. In the follow-up period, there were 4 deaths, all in the non-HITHOC group. Two deaths were due to myasthenic crisis, 1 due to severe fungal sepsis and 1 had systemic tumor recurrence (Table 2).

Although the overall survival was better in HITHOC group, it did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.06) (Image 1). This can be explained by two factors: (1) small sample size and (2) shorter follow-up. The small sample size is secondary to the rarity of this disease and due to the single institutional study. We feel the small sample size had masked the actual advantage of HITHOC in terms of statistical significance. Shorter follow-up also contributed to the mentioned results.

Image 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves (overall survival and relapse-free survival) in HITHOC group vs no HITHOC group

Discussion

Thymomas are rare yet, the most common anterior mediastinal neoplasms in adults. Presence of pleural or pericardial tumor deposits (not contiguous with the primary tumor mass in the mediastinum) is defined as stage IVA disease according to Masaoka-Koga staging system [2]. Only 7% (approximate) of thymoma patients initially present with pleural/pericardial metastasis [15]. Complete surgical resection is the standard of care for the management of early stage thymoma (Masaoka-Koga stages I and II). Even in stage III thymoma, radical resection achieving clear margins (R0 resection) has been found to be a favourable prognostic factor [16]. Based on these results, various surgical protocols were attempted in stage IVA thymoma also with acceptable perioperative outcomes [17, 18]. Overall survival and recurrence-free survival were found to be better in patients who underwent surgery compared to chemoradiotherapy alone [19]. The superiority of complete surgical resection over incomplete resection was also emphasized by various authors [7, 20]. Various surgical approaches have been proposed for Masaoka-Koga stage IVA thymic tumors, which include local pleurectomy, total pleurectomy and pleuro-pneumonectomy. The method of surgery has been highly individualized based on the volume and location of disease, individual surgeon preference and institutional protocols.

Most commonly utilized surgical approach is localized/total pleurectomy. This is possible when the disease is localized to parietal pleura. However, if the deposits were present over visceral pleura, they can be excised individually using electrocautery or by wedge resection of lung or anatomical lung resection (i.e. lobectomy) in cases of large deposits with lung invasion. These approaches have proven safe with minimal morbidity and mortality [21]. Few patients may present with extensive, diffuse, large, invasive deposits over parietal as well as visceral pleura which are too numerous to be removed individually. In such cases, pleuro-pneumonectomy has been studied as a therapeutic modality with potential benefits [22]. This technique also allows to give high doses of adjuvant radiotherapy to the ipsilateral chest with avoidance of radiation-induced pulmonary complications [23, 24]. However, this approach is associated with significant morbidity and mortality and should be considered a “last resort” [25].

In spite of these advancements, there has always been a concern for persistence of microscopic disease even after complete pleurectomy, which increases the possibility of pleural recurrence. So, inspired from hyperthermic intra-peritoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), HITHOC was proposed to address such microscopic residual disease topically. This method was first proposed and utilized in 11 patients with thymoma, 7 patients with mesothelioma and 8 other tumors by Yellin et al. in 2001 [26]. Till now, only few studies have evaluated the benefits of HITHOC in thymoma with pleural metastasis. Initial studies showed a morbidity of 13–47% without any mortality and good 5-year survival rate up to 70% [27, 28].

Under usual circumstances, the chemotherapeutic agent penetrates only few millimetres into the tumor cells. Therefore, total pleurectomy containing all the pleural nodules (macroscopic clearance) is recommended before performing HITHOC, leaving only few microscopic cells [29]. HITHOC exposes the whole of thoracic cavity, homogenously to the chemotherapeutic agent and ensures optimal dosage to the entire involved surface [30]. HITHOC provides an increased concentration of the chemo-therapeutic agent in the thorax (i.e. direct contact with the microscopic cells) for limited duration. This greatly reduces the systemic absorption of the chemotherapy agent, thus reducing the systemic toxicity [31]. Hyperthermia is beneficial in two ways. First, it increases the penetration capability of the chemotherapy agent, and second, hyperthermia itself has cytotoxic effects which synergizes with the anti-neoplastic effect of chemotherapeutic agent by activating apoptosis [32].

Various chemotherapeutic agents were used either individually or in combination (cisplatin alone, cisplatin and doxorubicin, or cisplatin and adriamycin) in the HITHOC protocol [14, 33]. However, cisplatin was the commonly used chemotherapeutic agent alone in major series with the dosages varying from 80 to 200 mg/m2 BSA (body surface area) [34]. The target temperature achieved was reported variously in the literature ranging from 40.3–44 °C. The perfusion time was also reported between 60 and 120 min [35]. The most common systemic side effect of HITHOC is renal insufficiency [36]. One of our patients (25%) had developed a sharp rise in serum creatinine levels; however, it recovered within few days without any need of renal replacement therapy. We follow two-point approach to prevent renal failure. First, we follow very strict hydration protocol, which starts from the day prior to surgery (pre-op) and continues up to 3rd/4th postoperative day (i.e. 100 ml/h IV fluids) for increased diuresis. Second, we restricted the dosage of cisplatin to 150 mg/m2 BSA.

There is a large interest growing in this approach in recent years. These studies reported overall survival rates of 67–89% with no perioperative mortality and recurrence. However, these studies included fewer patients with shorter follow-up (18.8–29 months) [28, 31]. The largest study of HITHOC in stage IVA thymoma by Yellin et al. [26] included 35 patients (17 primary, 14 recurrent, 4 thymic carcinoma). No systemic toxicity was reported with peri-operative morbidity of 11.4% and mortality of 2.5%. In our series also, patients in HITHOC group had no mortality (Image 2).

Image 2.

Flowchart of management of Masaoka-Koga stage IVA in the study population

Limitations

Present study has several limitations. First, retrospective nature of study which has propensity for selection bias. Second limitation of this study is the small study population which limits the strength of the study. Finally, the short duration of follow-up is another major limitation of this study as at least 10 years of follow-up is necessary to confidently comment on the recurrence of disease in thymomas.

Conclusions

Hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy (HITHOC) is a feasible and safe emerging option in the management of Masaoka-Koga stage IVA thymoma. Although this pilot study has not demonstrated any statistically significant survival benefit due to small numbers, addition of this modality has no added morbidity or mortality. As it is based on sound theoretical concept, there is need for a multi-institutional prospective randomized study with greater number of patients and longer follow-up to evaluate its exact place in the treatment of Masaoka-Koga stage IVA thymoma patients.

Declarations

Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This study has not been presented previously.

References

- 1.Cohen AJ, Thompson L, Edwards FH, Bellamy RF. Primary cysts and tumors of the mediastinum. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;51:378–386. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(91)90848-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koga K, Matsuno Y, Noguchi M, et al. A review of 79 thymomas: modification of staging system and reappraisal of conventional division into invasive and non-invasive thymoma. Pathol Int. 1994;44:359–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1994.tb02936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venuta F, Rendina EA, Anile M, et al. Thymoma and thymic carcinoma. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;60:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11748-011-0814-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro M, Korst RJ. Surgical approaches for stage IVA thymic epithelial tumors. Front Oncol. 2014;3:332. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riely GJ, Huang J. Induction therapy for locally advanced thymoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:S323–326. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f20e90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright CD, Wain JC, Wong DR, et al. Predictors of recurrence in thymic tumors: importance of invasion, WHO histology and size. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:1413–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Regnard JF, Magdeleinant P, Dromer C, et al. Prognostic factors and long-term results after thymoma resection: a series of 307 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;112:376–384. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(96)70265-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang J, Rizik NP, Travis WD, et al. Comparison of patterns of relapse in thymic carcinoma and thymoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright CD, Choi NC, Wain JC, et al. Induction chemoradiotherapy followed by resection for locally advanced Masaoka stage III and IVA thymic tumors. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:385–389. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spaggiari L, Casiraghi M, Guarize J. Multidisciplinary treatment of malignant thymoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:117–122. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32834ea6bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardillo G, Carleo F, Giunti R, et al. Predictors of survival in patients with locally advanced thymoma and thymic carcinoma (Masaoka stages III and IVA) Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2010;37:819–823. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucchi M, Davini F, Ricciardi R, et al. Management of pleural recurrence after curative resection of thymoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:1185–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishikawa Y, Matsuguma H, Nakahara R, et al. Multimodality therapy for patients with invasive thymoma disseminated into the pleural cavity: the potential role of extrapleural pneumonectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:952–957. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Bree E, van Ruth S, Baas P, et al. Cyto-reductive surgery and intraoperative hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma or pleural metastases of thymoma. Chest. 2002;121:480–487. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.2.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Detterbeck FC, Parsons AM. Thymic tumors: a review of current diagnosis, classification, and treatment. 3rd ed. In: Patterson GA, Cooper JD, Deslauriers J, Lerut AEMR, Luketich JD, Rice TW, editors. Pearson’s Thoracic & Esophageal Surgery. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone (2008). 1599 p.

- 16.Nakahara K, Ohno K, Hashimoto J, et al. Thymoma: results with complete resection and adjuvant postoperative irradiation in 141 consecutive patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1988;95:1041–1047. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(19)35673-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yano M, Sasaki H, Yukiue H, et al. Thymoma with dissemination: efficacy of macroscopic total resection of disseminated nodules. World J Surg. 2009;33:1425–1431. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucchi M, Ambrogi MC, Duranti L, et al. Advanced stage thymomas and thymic carcinomas: results of multimodality treatments. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1840–1844. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Froudarakis ME, Tiffet O, Fournel P, et al. Invasive thymoma: a clinical study of 23 cases. Respiration. 2001;68:376–381. doi: 10.1159/000050530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rena O, Mineo TC, Casadio C. Multimodal treatment for stage IVA thymoma: a proposable strategy. Lung Cancer. 2012;76:89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang J, Rizk NP, Travis WD, et al. Feasibility of multimodality therapy including extended resections in stage IVA thymoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134:1477–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright CD. Pleuropneumonectomy for the treatment of Masaoka stage IVA thymoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1234–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rusch VW, Rosenzweig K, Venkatraman E, et al. A phase II trial of surgical resection and adjuvant high-dose hemithoracic radiation for malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:788–795. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.116560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yajnik S, Rosenzweig KE, Mychalczak B, et al. Hemi-thoracic radiation after extrapleural pneumonectomy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:1319–1326. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(03)00287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fabre D, Fadel E, Mussot S, et al. Long-term outcome of pleuropneumonectomy for Masaoka stage IVA thymoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39:e133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yellin A, Simansky DA, Paley M, et al. Hyperthermic pleural perfusion with cisplatin: early clinical experience. Cancer. 2001;92:2197–2203. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011015)92:8<2197::AID-CNCR1563>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Refaely Y, Simansky DA, Paley M, et al. Resection and perfusion thermochemotherapy: a new approach for the treatment of thymic malignancies with pleural spread. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:366–370. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(01)02786-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ried M, Potzger T, Braune N, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy perfusion for malignant pleural tumors: perioperative management and clinical experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;43:801–807. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujimoto S, Takahashi M, Kobayashi K, et al. Relation between clinical and histologic outcome of intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion for patients with gastric cancer and peritoneal metastasis. Oncology. 1993;50:338–343. doi: 10.1159/000227206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Averbach AM, Sugarbaker PH. Methodologic considerations in treatment using intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Cancer Treat Res. 1996;82:289–310. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1247-5_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ried M, Hofmann HS. Intraoperative chemotherapy after radical pleurectomy or extrapleural pneumonectomy. Chirurg. 2013;84:492–496. doi: 10.1007/s00104-012-2433-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuzaki Y, Tomita M, Shimizu T, et al. Induction of apoptosis by intrapleural perfusion hyperthermo-chemotherapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;14:161–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ambrogi MC, Korasidis S, Lucchi M, et al. Pleural recurrence of thymoma: surgical resection followed by hyperthermic intrathoracic perfusion chemotherapy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49:321–326. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezv039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim ES, Putnam JB, Komaki R, et al. Phase II study of a multidisciplinary approach with induction chemotherapy, followed by surgical resection, radiation therapy, and consolidation chemotherapy for unresectable malignant thymomas: final report. Lung Cancer. 2004;44:369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tudor AA, Schmid RA, Kocher GJ. Does hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy prolong survival in patients with pleural thymoma? – a systematic review of the literature. Open J Surg. 2018;2:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ried M, Potzger T, Braune N, et al. Local and systemic exposure of cisplatin during hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy perfusion after pleurectomy and decortication for treatment of pleural malignancies. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:735–740. doi: 10.1002/jso.23321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]