Abstract

The algorithm for a new identification system was designed on the basis of colony color and morphology on CHROMagar Orientation medium in conjunction with simple biochemical tests such as indole (IND), lysine decarboxylase (LDC), and ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) utilization tests with gram-negative bacilli isolated from urine samples as well as pus, stool, and other clinical specimens by the following colony characteristics, biochemical reactions, and serological results: pinkish to red, IND positive (IND+), Escherichia coli; metallic blue, IND+, LDC+, and ODC negative (ODC−), Klebsiella oxytoca; IND+, LDC−, and ODC+, Citrobacter diversus; IND+ or IND−, LDC−, and ODC−, Citrobacter freundii; IND−, LDC+, and ODC+, Enterobacter aerogenes; IND−, LDC−, and ODC+, Enterobacter cloacae; IND−, LDC+, and ODC−, Klebsiella pneumoniae; diffuse brown and IND+, Morganella morganii; IND−, Proteus mirabilis; aqua blue, Serratia marcescens; bluish green and IND+, Proteus vulgaris; transparent yellow-green, serology positive, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; clear and serology positive, Salmonella sp.; other colors and reactions, the organism was identified by the full identification methods. The accuracy and cost-effectiveness of this new system were prospectively evaluated. During an 8-month period, a total of 345 specimens yielded one or more gram-negative bacilli. A total of 472 gram-negative bacillus isolates were detected on CHROMagar Orientation medium. For 466 of the isolates (98.7%), no discrepancies in the results were obtained on the basis of the identification algorithm. The cost of identification of gram-negative bacilli during this period was reduced by about 70%. The results of this trial for the differentiation of the most commonly encountered gram-negative pathogens in clinical specimens with the new algorithm were favourable in that it permitted reliable detection and presumptive identification. In addition, this rapid identification system not only significantly reduced costs but it also improved the daily work flow within the clinical microbiology laboratory.

The media most widely used for the isolation and differentiation of coliform gram-negative bacteria and other enteric pathogens from clinical specimens are MacConkey agar in the United States and modified Drigalski agar in Japan, but their ability to differentiate these types of organisms is minimal because they depend only on determination of lactose utilization. Several proprietary chromogenic mixtures, which have been available for some years, allow the presumptive identification of pathogenic organisms on the basis of colonial morphology and distinctive color patterns (9, 11, 12, 17). CHROMagar Orientation medium is a chromogenic culture medium that is usually used for the isolation and enumeration of urinary tract pathogens. It has several advantages, such as a greater ability to differentiate gram-negative bacilli, and facilitates the detection as well as presumptive identification of gram-negative bacilli (12). Several previous studies have shown that it can serve as a primary isolation and reliable differentiation medium for urinary tract pathogens, including gram-negative bacilli, enterococci, and staphylococci (9, 12, 17). However, its suitability for use with clinical specimens other than urine samples has not been assessed.

In the present study, I sought to evaluate the accuracy of the rapid identification system on the basis of colony colors, morphology on CHROMagar Orientation medium, and the results of additional simple biochemical tests such as indole, lysine decarboxylase, and ornithine decarboxylase utilization tests with gram-negative bacilli isolated from various clinical specimens. The objectives of the study were (i) to evaluate the usefulness of CHROMagar Orientation medium for the detection and presumptive identification of gram-negative bacilli when they were present in mixed cultures of clinical specimens after direct plating not only from urine but also from wound swab, stool, and other specimens, and (ii) to establish a cost-effective and rapid identification approach with CHROMagar Orientation medium that would aid in the optimal use of identification kits.

(This study was presented at the 100th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, Los Angeles, Calif., 21 to 25 May 2000.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

The algorithm for the rapid identification system (Table 1) was designed on the basis of colony color and morphology on CHROMagar Orientation medium in conjunction with simple biochemical tests such as indole, lysine decarboxylase, and ornithine decarboxylase utilization tests according to the manufacturer's instructions and as described by Merlino et al. (12). I prospectively evaluated the accuracy of the identification system with gram-negative bacilli from various clinical specimens between February 1999 and September 1999 in the microbiology laboratory of Chiba Children's Hospital, a 200-bed tertiary-care hospital. All gram-negative bacilli observed on CHROMagar Orientation medium were identified by use of the algorithm, and the results were compared to those obtained with the Crystal E/NF system (Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems [BBL], Cockeysville, Md.) and, if required, the API 20E system (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France).

TABLE 1.

Algorithm for presumptive identification of gram-negative bacilli isolated from clinical specimens

| Color reaction on CHROMagar Orientation medium | Results of differential reactionsa

|

Expected isolate(s) | Requirement for confirmation of identificationab | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IND | LDC | ODC | Serology | |||

| Pinkish to red | + | Escherichia coli | IND negative | |||

| Metallic blue (with or without halo) | + | + | − | Klebsiella oxytoca | ||

| + | − | + | Citrobacter diversus | |||

| ± | − | − | Citrobacter freundii | |||

| − | + | + | Enterobacter aerogenes | |||

| − | − | + | Enterobacter cloacae | |||

| − | + | − | Klebsiella pneumoniae | |||

| Diffuse brown | + | Morganella morganii | ||||

| − | Proteus mirabilis | |||||

| Transparent yellow-green | + | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Serology negative | |||

| Aqua blue | Serratia marcescens | |||||

| Bluish green | + | Proteus vulgaris | IND negative | |||

| Clear (whitish) | − | + | Salmonella sp. is suspicious | All isolates | ||

| Other colors | All isolates | |||||

IND, spot indole test; LDC, lysine decarboxylase; ODC, ornithine decarboxylase.

Crystal E/NF system; if required, the API 20E system.

Media (i) CHROMagar Orientation medium.

CHROMagar Orientation medium was purchased as prepared plates from BBL.

(ii) Quality control.

The following American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) strains were used for quality control of the medium and to assess color stability; Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606, Aeromonas caviae ATCC 15468, Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC 7966, Citrobacter freundii ATCC 8090, Enterobacter aerogenes ATCC 13048, Enterobacter cloacae ATCC 13047, Escherichia coli ATCC 35218, Klebsiella oxytoca ATCC 49131, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 27736, Morganella morganii ATCC 25830, Plesiomonas shigelloides ATCC 51903, Proteus mirabilis ATCC 7002, Proteus vulgaris ATCC 6380, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, Serratia marcescens ATCC 8100, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia ATCC 13637, and Yersinia enterocolitica ATCC 23715.

Adjunctive simple biochemical tests.

An indole spot test was performed with colonies on CHROMagar Orientation medium and/or colonies from a pure culture on modified heart infusion slant agar with DMACA Indole Dropper reagent (BBL).

Lysine decarboxylase and ornithine decarboxylase tests were carried out with OIML medium (Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan); they were combined in one tube to save time and materials. Colonies on CHROMagar Orientation medium were inoculated onto OIML medium by stabbing. After 18 to 24 h of incubation at 35°C, lysine decarboxylase and ornithine decarboxylase utilization was noted. Lysine decarboxylase utilization was determined by the presence of a purple color throughout the lower portion of the tube, and ornithine decarboxylase utilization was determined by the presence of a green or blue color in the upper portion.

The oxidase test was performed with an oxidase test stick (Eiken Chemical Co.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Salmonella O serogroup and Vi antigen were detected by agglutination with Salmonella antisera (Denka Seiken Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and serovar identification was confirmed by the Public Health Laboratory of Chiba Prefecture.

Serotyping of Pseudomonas aeruginosa was performed with Pseudomonas antisera (Denka Seiken).

Bacteriological procedures by specimen type. (i) Urine.

Urine samples were inoculated onto modified Drigalski agar plates (Nippon Becton Dickinson Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with a calibrated 5-μl loop. After centrifugation at 3,000 rpm (2,010 × g) for 10 min, Gram staining of the urine sediments was performed to evaluate whether a pyogenic reaction was present, and if gram-negative bacilli were also observed, these sediments were inoculated onto CHROMagar Orientation medium. The plates were incubated at 35°C for 18 to 24 h. In most laboratories, Gram staining of urine is not routinely performed with urinary sediment, and the culture plate would also not be inoculated, depending on whether gram-negative bacilli were observed in the direct smear. However, I had several reasons for routinely Gram staining urine sediments. Although Gram-staining examination of urine is slightly labor intensive, it is still a low-cost method for the estimation of bacteriuria and the presence of neutrophils. Most of the urine samples from pediatric patients in my hospital were collected in an adhesive bag placed on the perineum, meaning that they were often contaminated with multiple organisms normally present in the fecal flora. Accordingly, urine microscopy may help with determination of whether organisms in the urine are the possible causal bacteria or whether contamination is to blame, and it would also determine whether organism identification and susceptibility testing need to be carried out. Only in rare instances, when more fastidious organisms such as Haemophilus influenzae are suspected, is an enriched medium such as chocolate agar required to determine the cause of infection.

(ii) Pus, otorrheic, sputum, exudate, and other specimens.

Pus, otorrheic, sputum, exudate, and other specimens were also examined for the presence of gram-negative bacilli by Gram staining of smears. If gram-negative bacilli were observed, each sample was streaked onto CHROMagar Orientation medium, in addition to the appropriate agar plates.

(iii) Stool specimens.

Stool specimens were inoculated in parallel onto CHROMagar Orientation medium and appropriate agar plates such as modified Drigalski agar, Columbia-colistin-nalidixic acid (CNA) agar with 5% sheep blood, and CHROMagar Candida for surveillance for normal resident flora. Routinely, my laboratory also attempts to isolate Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli O157, Yersinia, and Campylobacter strains from all stool specimens submitted for culture because of gastrointestinal indications. Routine surveillance for fecal flora is not performed by many laboratories and would not be part of established laboratory protocols. In my hospital, as the number of stool specimens submitted for surveillance for normal resident flora is greater than the number submitted for surveillance for gastrointestinal pathogens, it was deemed necessary to try to evaluate the performance of CHROMagar Orientation medium for recognition of normal resident flora as well as enteric pathogens.

RESULTS

Accuracy of the algorithm.

During the 8-month study period, a total of 345 specimens yielded one or more gram-negative bacilli (Table 2), for a total of 472 gram-negative bacilli isolates on CHROMagar Orientation medium. More than one gram-negative bacillus species was detected in 80 (43.5%) of 184 stool specimens, 6 (6.0%) of 100 urine specimens, 5 (29.4%) of 17 pus specimens, and 11 (25.0%) of 44 other specimens. The colony characteristics of these isolates on this medium and the identification results are given in Table 3. Four hundred sixty-six (98.7%) of the total of 472 isolates were correctly identified by the identification system. For the remaining six isolates, one isolate of Citrobacter amalonaticus was misidentified as Citrobacter diversus, one isolate of Enterobacter agglomerans was misidentified as Citrobacter freundii, one isolate of Proteus penneri was misidentified as Proteus mirabilis and three isolates of Providenciae were misidentified as Morganella morganii because the algorithm did not include these species.

TABLE 2.

Recovery of gram-negative bacilli, by specimen source

| Organism | No. of clinical specimens

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of specimens (345)a | Feces (184) | Urine (100) | Pus (17) | Otorrheic specimen (13) | Sputum or nasal swab (13) | Exudate (5) | Ascitic fluid (2) | Peritoneal drainage (2) | Urine catheter tip (1) | Pleural fluid (1) | Bile (1) | Otherb (6) | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Acinetobacter lwoffii | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Citrobacter amalonaticus | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Citrobacter diversus | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||

| Citrobacter freundii | 13 | 11 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Enterobacter agglomerans | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Enterobacter cloacae | 37 | 20 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 | |||||

| Escherichia coli | 220 | 135 | 70 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 23 | 19 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 63 | 42 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Morganella morganii | 10 | 8 | 2 | ||||||||||

| Proteus mirabilis | 9 | 4 | 2 | 3 | |||||||||

| Proteus penneri | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Proteus vulgaris | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Providencia alcalifaciens | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Providencia rustigianii | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Providencia stuartii | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 42 | 6 | 12 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Salmonella spp. | 15 | 13 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Serratia marcescens | 19 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Total no. of isolates | 472 | 284 | 109 | 22 | 13 | 19 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

Values in parentheses are the total number of specimens yielding one or more gram-negative bacilli.

Gastric juice, bronchial tube and other tubes.

TABLE 3.

Identification results obtained with algorithm for presumptive identification of gram-negative bacilli and pigment reaction on CHROMagar Orientation medium

| Organism | Total no. of isolates | No. (%) of isolates with described color | Description of pigment on CHROMagar Orientation medium | No. of isolates

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correctly identified (with Crystal E/NF system) | Not identified | ||||

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 4 | 4 | White (nontransparent, mucoid) | 4 (4) | |

| Acinetobacter lwoffii | 1 | 1 | White (nontransparent) | 1 (1) | |

| Citrobacter amalonaticus | 1 | 1 | Light blue with diffuse edges | 1 | |

| Citrobacter diversus | 4 | 3 | Metallic blue with diffuse edges | 3 | |

| Citrobacter diversus | 1 | Metallic blue with pinkish border | 1 | ||

| Citrobacter freundii | 13 | 11 (84.6) | Metallic blue interior with pinkish border | 11 | |

| Citrobacter freundii | 2 (15.4) | Metallic blue with no halo | 2 | ||

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 2 | 2 | Metallic blue with no halo | 2 | |

| Enterobacter agglomerans | 1 | 1 | Metallic blue with no halo | 1 | |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 37 | 28 (75.7) | Metallic bluish purple with no halo | 27 | |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 9 (24.3) | Metallic bluish purple with purple-to-pink halo around periphery | 9 | ||

| Escherichia coli | 220 | 218 (99.1) | Pinkish to red | 218 | |

| Escherichia coli | 1 (0.5) | Clear (whitish) | 1 (1) | ||

| Escherichia coli | 1 (0.5) | Blue interior with pink halo (diffuse) | 1 (1) | ||

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 23 | 18 (78.3) | Metallic blue with no pink halo | 18 | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 5 (21.7) | Metallic blue with slight pink halo around periphery | 5 | ||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 63 | 60 (95.2) | Metallic blue with no pink halo | 59 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 3 (4.8) | Metallic blue with slight pink halo around periphery | 3 | ||

| Morganella morganii | 10 | 10 (100) | Diffuse brown | 10 | |

| Proteus mirabilis | 9 | 9 (100) | Diffuse brown | 9 | |

| Proteus penneri | 1 | 1 | Diffuse brown | 1 | |

| Proteus vulgaris | 2 | 2 | Bluish green with a slight brown background | 2 | |

| Providencia alcalifaciens | 1 | 1 | Diffuse brown | 1 | |

| Providencia rustigiani | 1 | 1 | Diffuse brown | 1 | |

| Providencia stuarii | 1 | 1 | Diffuse brown | 1 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 42 | 42 (100) | Transparent yellow to green, diffuse edges | 42 | |

| Salmonella spp. | 15 | 15 (100) | Clear (whitish) | 15 (15) | |

| Serratia marcescens | 19 | 19 (100) | Aqua blue | 19 | |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 2 | 2 | Clear (whitish) | 2 (2) | |

| Total no. of isolates | 472 | 466 (24) | 6 | ||

The accuracy of the algorithm by the observed colors of the colonies on the CHROMagar Orientation medium is shown in Table 4. All 218 isolates of pinkish to red colonies were correctly identified as Escherichia coli in conjunction with their indole positivity. I found that characteristic transparent yellow-green colonies (n = 42) were also correctly identified as Pseudomonas aeruginosa in conjunction with their serological results. All aqua blue colonies (n = 19) were correctly identified as Serratia marcescens. This color deepened to a dark blue after 1 to 2 h at room temperature, during the period of examination, a finding in accordance with the results of an earlier study (12). This characteristic appearance was extremely useful in the identification of this organism. Clear to white undifferentiated colonies (n = 18) were correctly identified as Salmonella sp. (n = 15), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (n = 2), or Escherichia coli (n = 1) by the Crystal E/NF system according to the identification algorithm.

TABLE 4.

Identification results obtained with algorithm for presumptive identification of gram-negative bacilli

| Observed color of colonies on CHROMagar Orientation medium | No. of isolates | No. (%) of isolates correctly identified |

|---|---|---|

| Pinkish to red | 218 | 218 (100) |

| Metallic blue (with or without halo) | 144 | 142 (98.6) |

| Diffuse brown | 23 | 19 (82.6) |

| Transparent yellow-green | 42 | 42 (100) |

| Aqua blue | 19 | 19 (100) |

| Bluish green | 2 | 2 (100) |

| Clear (whitish) | 18 | 18 (100) |

| Other colora | 6 | 6 (100) |

| Total | 472 | 466 (98.7) |

White (nontransparent, mucoid colony), white (nontransparent), or blue interior with pink halo.

Cost-effectiveness of the approach.

Cost comparison results were based on the commercial cost of each system (Table 5), but the cost of the labor associated with testing was not included. Only 24 identification kits were needed during the 8-month period. An overall reduction of about 70% in the cost of identification of gram-negative bacilli was achieved during this period.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of cost of the Crystal E/NF identification system and new rapid identification systema

| Item (cost [$] per test) | Crystal E/NF system

|

New rapid identification system

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of tests | Total cost ($) | No. of tests | Total cost ($) | |

| Crystal E/NF system (7.69) | 472 | 3,630 | 24 | 184 |

| CHROMagar Orientation medium (2.21) | 345 | 763 | ||

| OIML agarb (1.04) | 144 | 150 | ||

| Modified heart infusion slant agarc (0.02) | 472 | 11 | 224 | 5 |

| Total | 472 | 3,641 | 472 | 1,102 |

During an 8-month period.

Ornithine decarboxylase and lysine decarboxylase production test.

Indole production test.

Evaluation of usefulness of CHROMagar Orientation medium. (i) Recognition of gram-negative bacilli.

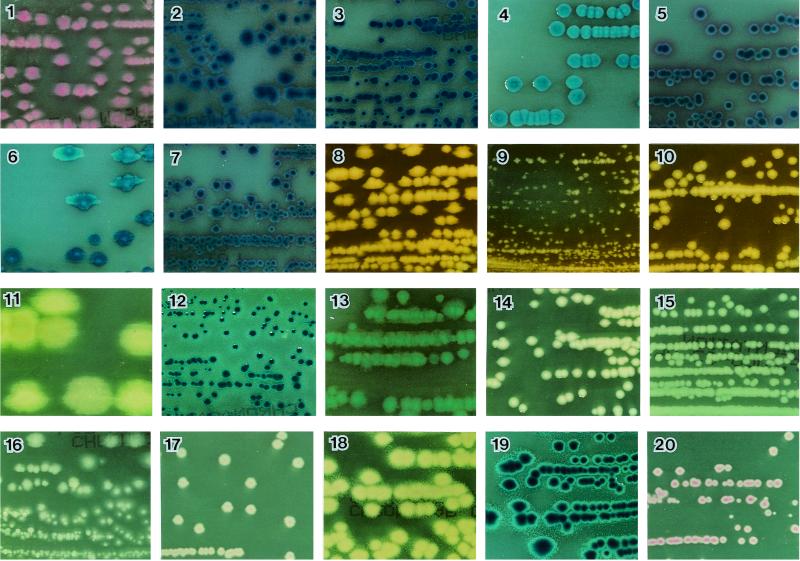

Figure 1 demonstrates representative color reactions for selected organisms on the CHROMagar Orientation medium. Escherichia coli was the predominant isolate in the study, with 218 of 220 isolates (99.1%) producing a pinkish-to-red color (Fig. 1, no. 1). Twelve lactose-negative isolates and three mucoid-colony isolates also demonstrated the same color. Of the two remaining Escherichia coli isolates, one was colorless (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside [ONPG] negative), and the other had a blue interior with a pink halo (both ONPG and β-glucoside positive), which was different from the color of Klebsiella-Enterobacter-Citrobacter (K-E-C) group (metallic blue).

FIG. 1.

Colonies of selected organisms plated on CHROMagar Orientation medium. 1, Escherichia coli; 2, Enterobacter aerogenes; 3, Enterobacter cloacae; 4, Klebsiella pneumoniae; 5, Citrobacter freundii; 6, Klebsiella oxytoca; 7, Citrobacter diversus; 8, Proteus mirabilis; 9, Morganella morganii; 10, Providencia stuartii; 11, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; 12, Serratia marcescens; 13, Proteus vulgaris; 14, Acinetobacter baumannii; 15, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia; 16, Salmonella; 17, Plesiomonas shigelloides; 18, Aeromonas hydrophila; 19, Aeromonas caviae; 20, Aeromonas sobria.

The K-E-C group isolates regularly produced a metallic blue color with or without a purple to pink halo (Fig. 1, no. 2 to 7). Although the K-E-C group may be difficult, if not impossible, to identify by colony color and morphology alone, these isolates were distinguished as coliforms from other gram-negative bacilli and could easily be differentiated by the use of simple additional tests, such as indole, lysine decarboxylase, or ornithine decarboxylase utilization tests, by following the identification chart.

The Proteus, Morganella, and Providencia (P-M-P) group isolates demonstrated diffuse brown colonies as a result of tryptophan deaminase production (Fig. 1, no. 8 to 10). Proteus vulgaris isolates (n = 2) had bluish green colonies with a slight brown background (Fig. 1, no. 13). Acinetobacter baumannii (n = 4) consisted of nontransparent convex colonies (Fig. 1, no. 14), making these isolates easily distinguishable from the other species described above.

(ii) Recognition of enteric pathogens.

During the study period, a total of 15 Salmonella isolates were isolated from fresh stool samples, and no other enteric organisms were recovered. The 15 isolates were lactose negative and H2S positive, yielding clear colonies on CHROMagar Orientation medium (Fig. 1, no. 16). They were distinguishable from the common species in stool by their colony color. One isolate was detected with CHROMagar Orientation medium only, and for three isolates the number of colonies on this medium was greater than the number on Salmonella-shigella agar, which is usually used for isolation. It is probable that the peptone and yeast extract in the formulation provided additional enrichment, and the absence of inhibitory effects may also contribute to its efficiency. I found that this medium allows the detection of Salmonella even in mixed cultures and even when the colony counts are low. Additionally, this medium was useful for the differentiation of Salmonella (clear) from other H2S-producing members such as Citrobacter freundii (metallic blue) and Proteus (brown) and permitted the accurate retrieval of colonies to elicit other biochemical and serological reactions.

(iii) Other advantages.

The CHROMagar Orientation medium prevented the swarming of Proteus isolates and limited the spread of mucoid Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Klebsiella oxytoca isolates, which may yield confluent growth on plates, as was also demonstrated in previous studies (9, 12, 17).

DISCUSSION

Laboratories must perform accurate and cost-effective identification of clinical isolates of gram-negative bacilli (14, 15, 18). In addition, rapid bacterial identification and susceptibility testing in the microbiology laboratory can have a demonstrable clinical impact as well as provide significant cost savings, as was demonstrated by Doern et al. (3) in a large prospective study. One of the more recent advances in the rapid presumptive identification of pathogenic organisms is the use of different colony colors that are produced by the reactions of genus- or species-specific enzymes with chromogenic substrates (1, 2, 4–13, 16, 17). In this regard, the study by Merlino et al. (12) was attractive, as it described the major advantages of CHROMagar Orientation medium and showed that it had a greater ability to differentiate the common species of gram-negative bacilli. The purpose of the present study not only was to determine the usefulness of this medium but also was to evaluate the accuracy and cost-effectiveness of the algorithm for the rapid identification of gram-negative bacilli in mixed cultures of various clinical specimens. Additionally, in this evaluation, I considered that use of this medium might reduce the number of identification kits needed but not the number of culture media used, resulting in more accurate identifications when the results obtained with the medium were used in conjunction with growth characteristics on other media, and might substantially lower the work load in the laboratory.

The overall accuracy of the present approach to the identification of gram-negative bacilli was 98.7% (466 of 472 isolates). The result obtained with the proposed algorithm for identification showed an excellent correlation with the results obtained with the commercial identification panel, confirming its usefulness for primary isolation and differentiation of clinical gram-negative bacilli from various specimens such as urine, wound swab, otorrheic, and stool specimens for surveillance for normal resident flora and other organisms. In addition, I estimate that the use of this identification system will result in material savings equivalent to about $3,850 per year in my laboratory, in addition to reducing labor and enabling rapid reporting of clinically relevant laboratory results, without a loss of sensitivity. I believe that this protocol could easily be adopted by most clinical laboratories.

Several other studies have recommended the use of CHROMagar Orientation medium as a single medium for reliable detection, enumeration, and presumptive identification of urinary tract pathogens (9, 17). My study revealed that about 64% (70 of 109) of the gram-negative bacilli from urine specimens were Escherichia coli, a proportion similar to that found in prior studies (9, 17). In addition, all 109 isolates from the 100 urine samples containing more than one organism were accurately identified without discrepancy when the algorithm was used. Thus, this algorithm appears to be an excellent and time-saving method for the rapid identification of the causative pathogens of urinary tract infections.

Of the six isolates misidentified in this study, two (Citrobacter amalonaticus and Enterobacter agglomerans) were not included in the flow diagram, and their frequency of isolation in the routine laboratory may be very low. As for the remaining four isolates, one of Proteus penneri and three of the genus Providencia were not correctly identified because other simple tests other than the indole reaction were not performed in this trial. Members of the P-M-P group were easily distinguished on primary plates because of their brown colonies on a diffuse beige pigment background. Proteus mirabilis and Morganella morganii, important pathogens in urinary tract infections, may be differentiated by the indole spot test. I reasoned that as the frequencies of isolation of Proteus penneri and Providencia spp. in the routine laboratory are probably low, they need not be included in the algorithm. However, because of the results of the present study, I intend to change the logic for the screening of these organisms and include the ornithine decarboxylase test, that is, to use the ornithine decarboxylase test when indole-negative and ornithine-positive isolates are identified as Proteus mirabilis and when both indole- and ornithine-negative isolates are identified as Proteus penneri, as well as when both indole- and ornithine-positive isolates are identified as Morganella morganii and indole-positive and ornithine-negative isolates are presumptively identified as Providencia species. If definitive identification is still required, the Crystal E/NF system could be used. This logic may allow the more accurate identification of the P-M-P group of organisms.

As pointed out by Merlino et al. (12), the use of CHROMagar Orientation medium by laboratory workers afflicted with various types of color blindness may lead to difficulties in distinguishing differences in color and colony appearance. In the present study, I created a colony color table to help overcome this problem. Practice is also required to correctly interpret the colors of colonies of major organisms before this medium is used. Furthermore, it is extremely important that when questionable colony colors and morphology are encountered in the interpretation of culture results, the color logic chart should not be applied and the colony should be investigated by the full identification methods available.

In summary, the approach to presumptive identification of gram-negative bacilli on the basis of both colony color and morphology on CHROMagar Orientation medium and adjunctive simple biochemical tests described here provides a reliable routine method for the primary isolation and differentiation of isolates from specimens from various body sites. An additional important advantage of this medium is the easy recognition of bacterial growth and the simultaneous detection of multiple organisms so that the identity of the organisms and the results of antibiotic susceptibility tests can be more accurately reported. Furthermore, the new rapid identification system contributes significantly to reducing the number of identification kits needed and to streamlining the daily work flow in the clinical laboratory.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I am grateful to Shigeru Nakayama for the photography.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dalet F, Segovia T. Evaluation of a new agar in Uricult-for rapid detection of Escherichia coli in urine. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1395–1398. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1395-1398.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delisle G J, Ley A. Rapid detection of Escherichia coli in urine samples by a new chromogenic β-glucuronidase assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:778–779. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.778-779.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doern G, Vautour R, Gaudet M, Levy B. Clinical impact of rapid in vitro susceptibility testing and bacterial idenification. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1757–1762. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1757-1762.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dusch H, Altwegg M. Comparison of Rambach agar, SM-ID medium, and Hektoen Enteric agar for primary isolation of non-typhi salmonellae from stool samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:410–412. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.410-412.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edberg S C, Kontnick C M. Comparison of β-glucuronidase-based substrate systems for identification of Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:368–371. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.3.368-371.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaillot O, Camillo P D, Berche P, Courcol R, Savage C. Comparison of CHROMagar Salmonella medium and Hektoen enteric agar for isolation of salmonellae from stool samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:762–765. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.762-765.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geiss H K. Comparison of two test kits for rapid identification of E. coli by a beta-glucuronidase assay. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;9:151–152. doi: 10.1007/BF01963647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heizmann W, Döller P C, Gutbrod B, Werner H. Rapid identification of Escherichia coli by Fluorocult media and positive indole reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2682–2684. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.12.2682-2684.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hengstler K A, Hammann R, Fahr A. Evaluation of BBL CHROMagar Orientation medium for detection and presumptive identification of urinary tract pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2773–2777. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2773-2777.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larinkari U, Rantio M. Evaluation of a new dipslide with a selective medium for the rapid detection of beta-glucuronidase-positive Escherichia coli. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:606–609. doi: 10.1007/BF01690735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazoyer M A, Orenga S, Doleans F, Freney J. Evaluation of CPS ID2 medium for detection of urinary tract bacterial isolates in specimens from a rehabilitation center. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1025–1027. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.1025-1027.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merlino J, Siarakas S, Robertson G J, Funnell G R, Gottlieb T, Bradbury R. Evaluation of CHROMagar Orientation for differentiation and presumptive identification of gram-negative bacilli and Enterococcus species. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1788–1793. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1788-1793.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Odds F C, Bernaerts R. CHROMagar Candida, a new differential isolation medium for presumptive identification of clinically important Candida species. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1923–1929. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.8.1923-1929.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pattyn S R, Sion J P, Verhoeven J. Evaluation of the LOGIC system for the rapid identification of members of the family Enterobacteriaceae in the clinical microbiology laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1449–1450. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1449-1450.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perry J D, Ford M, Hjersing N, Gould F K. Rapid conventional scheme for biochemical identification of antibiotic resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates from urine. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41:1010–1012. doi: 10.1136/jcp.41.9.1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfaller M A, Houston A, Coffmann S. Application of CHROMagar Candida for rapid screening of clinical specimens for Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, Candida krusei, and Candida (Torulopsis) glabrata. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:58–61. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.1.58-61.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samra Z, Heifetz M, Talmor J, Bain E, Bahar J. Evaluation of use of a new chromogenic agar in detection of urinary tract pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:990–994. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.990-994.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yong DCT, Thompson J S, Prytula A. Rapid microbiochemical method for presumptive identification of gastroenteritis-associated members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:914–918. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.6.914-918.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]