Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is associated with a greater risk of COVID-19 and an increased mortality when the disease is contracted. Metformin use in patients with DM is associated with less COVID-19-related mortality, but the underlying mechanism behind this association remains unclear. Our aim was to explore the effects of metformin on markers of inflammation, oxidative stress, and hypercoagulability, and on clinical outcomes. Patients with DM on metformin (n = 34) and metformin naïve (n = 41), and patients without DM (n = 73) were enrolled within 48 h of hospital admission for COVID-19. Patients on metformin compared to naïve patients had a lower white blood cell count (p = 0.02), d-dimer (p = 0.04), urinary 11-dehydro thromboxane B2 (p = 0.01) and urinary liver-type fatty acid binding protein (p = 0.03) levels and had lower sequential organ failure assessment score (p = 0.002), and intubation rate (p = 0.03), fewer hospitalized days (p = 0.13), lower in-hospital mortality (p = 0.12) and lower mortality plus nonfatal thrombotic event occurrences (p = 0.10). Patients on metformin had similar clinical outcomes compared to patients without DM. In a multiple regression analysis, metformin use was associated with less days in hospital and lower intubation rate. In conclusion, metformin treatment in COVID-19 patients with DM was associated with lower markers of inflammation, renal ischemia, and thrombosis, and fewer hospitalized days and intubation requirement. Further focused studies are required to support these findings.

Keywords: COVID-19, Diabetes, Metformin, Thromboelastography, Biomarker, Death, Intubation

Highlights

Fasting blood glucose level in patients with COVID-19 has been shown to be associated with severity of the disease and poor outcomes, including mortality.

Metformin use in patients with DM is associated with less COVID-19-related mortality, but the underlying mechanism behind this association remains unclear.

In this single center study, metformin treatment in COVID-19 patients with DM was associated with lower markers of inflammation, renal ischemia, and thrombosis, and fewer hospitalized days and intubation requirement.

In a multiple regression analysis, metformin use was associated with less days in hospital and lower intubation rate.

Introduction

Patients with COVID-19 have a higher prevalence of preexisting DM. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is known to induce new onset DM suggesting a bidirectional association [1, 2]. Since both diseases are associated with endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and hypercoagulability, their co-existence has been associated with a higher rate of severe adverse event occurrences, including mortality [3–5]. Moreover, fasting blood glucose level in patients with COVID-19 has been shown to be associated with severity of the disease and poor outcomes, including mortality [6]. Therefore, in addition to the standard-of-care treatment, rigorous control of blood glucose is an important treatment strategy in patients with COVID-19 and DM. Among glucose lowering agents, metformin is the most widely used. It is a well-studied, widely available, inexpensive agent with limited side effects. Significantly lower in-hospital mortality has been reported in meta-analyses and retrospective studies of patients with COVID-19 treated with metformin [7, 8]. In a recent population-based study of 2.85 million patients with COVID-19 and type 2 DM from the United Kingdom, metformin was the most widely used agent and was associated with a 23% reduction in in-hospital mortality (adjusted HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.73–0.81), whereas insulin therapy was associated with a 42% increase in in-hospital mortality (adjusted HR 1.42, 95% CI 1.35–1.49) compared to no recorded prescription of glucose lowering drugs [9]. In another study of an elderly minority population with COVID-19 from the United States of America (n = 11,390), metformin treatment was associated with lower rates of hospitalization and death and less disease severity [10].

In addition to glucose lowering effects, in vitro and animal model experiments have demonstrated anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of metformin [11–13]. Thus far, minimal data is available regarding the relation between metformin treatment, laboratory biomarkers, and their association to clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. Therefore, our aim was to study biomarkers of COVID-19, inflammation, hypercoagulability, renal ischemia and oxidative stress and in-hospital clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients with DM treated with and without metformin and in patients without DM.

Research design and methods

This report is a sub-analysis of the evaluation of hemostasis in hospitalized COVID-19 patients (TARGET-COVID) study (URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT04493307). The study was performed in accordance with standard ethical principles and approved by the local institutional review board. Patients were eligible for enrollment into the study if they were 18 years of age or older, had a new diagnosis of COVID-19 infection and were being admitted to hospital on either in-patient acute care or critical care service. All participants of the study were selected for this sub-analysis for one of the three arms including patients without diabetes mellitus, patients with diabetes mellitus on metformin and patient with diabetes mellitus not on metformin. All patients provided written consent. We enrolled hospitalized patients within 48 h of hospitalization between April, 2020 and February, 2021 who were diagnosed with COVID-19 by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assay. Diabetes mellitus was defined as patients on oral hypoglycemic agents/insulin or hemoglobin A1c level of > 6.5% [14]. Seventy-three patients without DM, thirty-four patients with DM on metformin therapy at the time of hospital admission and forty-one patients with DM who were metformin naïve were enrolled.

Sample collection

Laboratory assessments were conducted within 48 h of hospital admission. Venous blood was collected into Vacutainer tubes (Becton‐Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) containing 3.2% trisodium citrate for the thromboelastography (TEG)-6 s assay.

Thromboelastography

The TEG‐6 s is a microfluidic automated cartridge-based assay that can be used at the bedside [15]. The citrated multi‐channel assay measures platelet–fibrin clot strength or maximum amplitude (P-FCS or MA), reaction time (R, a measure of the enzymatic phase of coagulation), kinetics (K, a measure of the time to reach 20 mm of clot strength from R), angle (α, reflective of the velocity of clot strength generation), FCS (a measure of fibrin clot strength measured in the presence of tissue factor and a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor to isolate the contribution of fibrinogen during clot generation) and functional fibrinogen levels (FLEV, a measurement extrapolated from the FCS) [15].

Standard COVID-19 biomarkers

Standard COVID-19 biomarkers were analyzed in the central pathology laboratory at the Sinai Hospital of Baltimore. C-reactive protein (CRP) and ferritin were measured using Siemens Advia Chemistry XPT systems (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc. Malvern, PA, USA). Procalcitonin was measured using Abbott ARCHITECT B.R.A.H.M.S PCT assay (Abbott, Abbott Parks, IL, USA). Complete blood cell analysis was performed using Sysmex XN-1000™ Hematology Analyzer (Sysmex America Inc, Lincolnshire, IL, USA). Coagulation parameters were measured using STA Compact Max Analyzer (Diagnostica Stago, Inc., Parsippany, NJ, USA).

Urinary biomarkers

Urinary 11-dehydro-thromboxane B2 (u11-dh-TxB2) levels were determined using an enzyme-linked immune assay and microalbumin levels were determined using the Dimension clinical chemistry system and processed by Inflammatory Markers Laboratory (Wichita, KS) [16]. Urinary 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) levels were measured by enzyme-linked immune assay at CEDx Labs (Nashua, NH, USA) and liver-type fatty acid binding protein (L-FABP) levels were determined using a rapid, point-of-care lateral flow immunoassay (Timewell Medical, Tokyo, Japan) whose results were quantified using a CHR-631 Rapid Test Reader (Kaiwood Technology Co., Ltd., Tainan City, Taiwan) [17, 18].

Sequential organ failure assessment

The SOFA score is based on PaO2, FiO2, presence or absence of mechanical ventilation, platelet number, Glasgow coma scale, bilirubin, mean arterial pressure or administration of vasoactive agents, and creatinine. (https://www.mdcalc.com/sequential-organ-failure-assessment-sofa-score). Patients were categorized as SOFA score ≥ 3 and < 3 for comparison of standard and thromboelastography makers. SOFA score is used to indicate the severity of organ dysfunction and poor clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 [19].

Clinical events

In-hospital events including all-cause death, pulmonary thromboembolism, type 1 myocardial infarction (MI), ischemic stroke, days in hospital and intubation requirement were collected.

Statistical analysis

Continuous values were shown as mean ± SD for normally distributed data and mean and confidence interval for not normally distributed data. The Shapiro‐Wilk test was used to determine the normality of data and the student T test was used to compare the groups. Categorical variables were shown as counts and percentages. The chi‐squared test was used to determine whether there was a significant difference in frequencies between groups and outcomes. Multiple regression analysis was performed to identify independent variables such as glucose, body mass index (BMI), DM, age, creatinine, use of metformin, steroids, aspirin and insulin associated with duration of hospitalization, death and rate of mechanical ventilation (intubation). p < 0.05 was considered a significant difference between groups. (MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgium).

Results

The majority of patients were African American (African Americans with DM ~ 70%, without DM 59%). Compared to the DM group, the group without DM had less hypertension and hyperlipidemia. DM patients not on metformin compared to patients on metformin had a higher frequency of renal disease (p = 0.01) and a higher SOFA score (p = 0.002) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics

| DM | No DM (n = 73) | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metformin (n = 34) | No Metformin (n = 41) | Metformin vs. no metformin | Metformin vs. no DM | No metformin vs. No DM | ||

| Age (years) | 60 ± 18 | 67 ± 14 | 55 ± 19 | 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.0006 |

| Male, n (%) | 20 (59) | 20 (49) | 48 (66) | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.08 |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| African American | 24 (71) | 30 (73) | 43 (59) | 0.85 | 0.23 | 0.14 |

| Hispanic | 5 (15) | 5 (12) | 8 (11) | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.87 |

| Caucasian | 4 (12) | 4 (10) | 22 (30) | 0.78 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Asian | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.67 | 0.14 | 0.055 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 35.1 ± 11.6 | 32.1 ± 8.0 | 34.1 ± 11.8 | 0.19 | 0.68 | 0.34 |

| Co-morbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 28 (82) | 37 (90) | 43 (60) | 0.32 | 0.02 | 0.0008 |

| Hyperlipidaemia, n (%) | 17 (50) | 25 (61) | 24 (33) | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.004 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 21 (64) | 19 (46) | 40 (56) | 0.12 | 0.44 | 0.31 |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 10 (29) | 12 (29) | 10 (14) | 1.00 | 0.07 | 0.053 |

| Respiratory disease, n (%) | 7 (21) | 14 (34) | 19 (26) | 0.22 | 0.58 | 0.37 |

| Neurological disease/mental illness | 6 (18) | 12 (29) | 19 (26) | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.73 |

| Renal disease, n (%) | 2 (6) | 12 (29) | 6 (8) | 0.01 | 0.71 | 0.003 |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 2 (6) | 4 (10) | 2 (3) | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.12 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 1 (3) | 3 (7) | 6 (8) | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.85 |

| Sequential organ failure assessment score | 2.0 ± 1.5 | 4.2 ± 3.7 | 3.0 ± 3.0 | 0.002 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

There were no significant differences in medications between DM patients on metformin and metformin naïve patients, except proton pump inhibitor/H2 blocker use was higher in patients on metformin (p = 0.03) (Table 2). Among laboratory measurements, white blood cell counts were higher in DM patients not on metformin treatment compared to patients on metformin (p = 0.02) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Medications

| DM | No DM (n = 73) | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metformin (n = 34) | No metformin (n = 41) | Metformin vs. no metformin | Metformin vs. no DM | No metformin vs. No DM | ||

| Antiviral medications, n (%) | ||||||

| Remdesivir | 10 (29) | 12 (29) | 21 (29) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 2 (6) | 4 (10) | 5 (7) | 0.53 | 0.85 | 0.57 |

| Convalescent plasma | 8 (24) | 16 (39) | 21 (29) | 0.17 | 0.59 | 0.28 |

| Antithrombotic medications, n (%) | ||||||

| None | 3 (9) | 4 (10) | 7 (10) | 0.88 | 0.87 | 1.00 |

| Enoxaparin prophylaxis | 18 (53) | 13 (32) | 40 (55) | 0.07 | 0.85 | 0.02 |

| Heparin prophylaxis | 7 (21) | 9 (22) | 13 (18) | 0.92 | 0.71 | 0.61 |

| Therapeutic anticoagulation | 4 (12) | 11 (27) | 9 (12) | 0.11 | 1.00 | 0.04 |

| Direct oral anticoagulant | 2 (6) | 4 (10) | 4 (5) | 0.53 | 0.83 | 0.31 |

| Aspirin | 14 (41) | 14 (34) | 16 (22) | 0.54 | 0.04 | 0.16 |

| Antibiotic medications, n (%) | ||||||

| Ceftriaxone | 15 (44) | 16 (39) | 37 (51) | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.22 |

| Azithromycin | 16 (47) | 12 (29) | 36 (49) | 0.11 | 0.85 | 0.04 |

| Vancomycin | 6 (18) | 6 (15) | 7 (10) | 0.73 | 0.25 | 0.43 |

| Steroids | 25 (74) | 30 (73) | 48 (66) | 0.92 | 0.41 | 0.44 |

| Statins | 13 (38) | 21 (51) | 18 (25) | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.005 |

| Proton pump inhibitors/H2 blockers | 10 (29) | 22 (54) | 24 (33) | 0.03 | 0.68 | 0.03 |

Therapeutic anticoagulation = full dose heparin administration

Direct oral anticoagulant = apixaban

Table 3.

Laboratory measurements

| DM | No DM (n = 73) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metformin (n = 34 | No Metformin (n = 41) |

Metformin vs. no metformin | Metformin vs. no DM | No metformin vs. No DM | ||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 3.6 | 1.1 ± 1.8 | 0.21 | 1.00 | 0.12 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 198 ± 82 | 190 ± 85 | 121 ± 62 | 0.68 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Aspartate transaminase (u/L) | 49 ± 31 | 64 ± 62 | 64 ± 88 | 0.20 | 0.34 | 1.00 |

| Alanine transaminase (u/L) | 49 ± 61 | 61 ± 68 | 55 ± 63 | 0.43 | 0.64 | 0.64 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (u/L) | 98 ± 88 | 93 ± 49 | 71 ± 26 | 0.76 | 0.02 | 0.002 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 382 ± 108 | 439 ± 229 | 445 ± 357 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 0.92 |

| Prothrombin time (secs) | 14.6 ± 3.3 | 14.0 ± 3.1 | 14.9 ± 2.8 | 0.42 | 0.63 | 0.12 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.56 ± 0.21 | 0.65 ± 0.64 | 0.61 ± 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.68 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 3.6 ± 0.7 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 0.54 | 0.09 | 0.009 |

| Platelet (× 1000/mm3) | 262 ± 85 | 287 ± 154 | 257 ± 128 | 0.40 | 0.84 | 0.27 |

| White blood cells (K/mm3) | 8.6 ± 3.8 | 10.7 ± 3.8 | 8.4 ± 5.0 | 0.02 | 0.84 | 0.012 |

| Haematocrit (%) | 37 ± 6 | 37 ± 7 | 38 ± 6 | 1.00 | 0.42 | 0.42 |

| Neutrophil/leukocyte ratio | 9.3 ± 10.7 | 10.7 ± 9.2 | 8.3 ± 7.4 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.13 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.9 ± 2.1 | 11.7 ± 2.3 | 12.1 ± 2.3 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.37 |

| HaemoglobinA1c | 8.7 ± 2.3 | 8.5 ± 1.9 | 5.8 ± 0.8 | 0.68 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Thromboelastography

There were no significant differences between thromboelastography indices in DM patients on and not on metformin (Table 4). Patients without DM compared to patients with DM had lower levels of platelet–fibrin clot strength (p ≤ 0.04), functional fibrinogen (p ≤ 0.01) and fibrin clot strength (p ≤ 0.02), whereas reaction time was shorter in DM patients not on metformin compared to patients without DM (p = 0.02).

Table 4.

Thromboelastography measurements and standard biomarkers of COVID-19

| DM | No DM (n = 73) | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metformin (n = 34) | No metformin (n = 41) | Metformin vs. no metformin | Metformin vs. no DM | No metformin vs. No DM | ||

| Thromboelastography measurements | ||||||

| Reaction time (minutes) | 6.3 ± 2.1 | 5.6 ± 1.6 | 6.4 ± 1.9 | 0.11 | 0.81 | 0.02 |

| Fibrin clot strength (mm) | 43.5 ± 11.4 | 43.1 ± 12.4 | 37.2 ± 13.1 | 0.89 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Functional Fibrinogen level (mg/dL) | 791 ± 206 | 802 ± 215 | 674 ± 226 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 0.004 |

| Platelet–fibrin clot strength (mm) | 68.6 ± 4.9 | 69.6 ± 4.1 | 66.1 ± 6.3 | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.002 |

| Clot lysis (%) | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.9 | 0.9 ± 1.3 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| Standard markers | ||||||

| D-dimer (mg/L, FEU) | 1.8 ± 2.1 | 3.6 ± 4.5 | 2.2 ± 3.4 | 0.04 | 0.53 | 0.06 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 115 ± 100 | 86 ± 89 | 99 ± 76 | 0.19 | 0.36 | 0.41 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 672 ± 491 | 788 ± 575 | 988 ± 1984 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.53 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0.7 ± 2.1 | 3.2 ± 12.0 | 1.3 ± 4.2 | 0.23 | 0.43 | 0.22 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 3.6 | 1.1 ± 1.8 | 0.21 | 1.00 | 0.12 |

Standard COVID-19 biomarkers

There were no significant differences in C-reactive protein, ferritin, procalcitonin and creatinine between the three groups. D-dimer levels were lower in DM patients on metformin compared to metformin naïve patients (p = 0.04) and were similar between DM patients on metformin and patients without DM (Table 4).

Urinary biomarkers

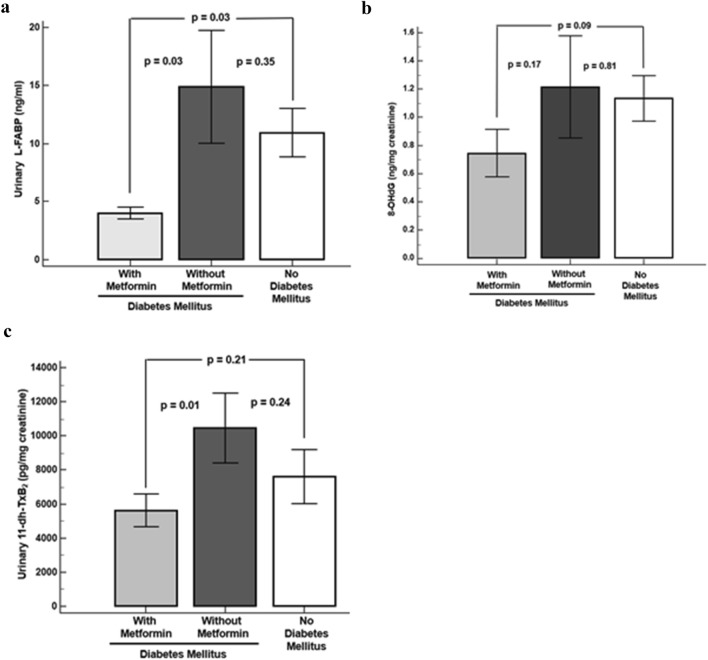

Compared to DM patients on metformin, urinary L-FABP levels were higher in metformin naïve patients (p = 0.03) and patients without DM (p = 0.03) (Fig. 1a). U11-dh-TxB2 levels were higher in metformin naïve patients compared to DM patients on metformin (p = 0.01) (Fig. 1b). 8-OHdG levels were numerically lower in DM patients on metformin compared to patients not on metformin and patients without DM (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Urinary biomarkers. a Urinary L-fatty acid binding protein. b Urinary 11-dehydro-thromboxane B2. c Urinary 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine

Clinical outcomes

Compared to metformin naïve patients, patients on metformin had a lower rate of intubation (p = 0.03) and fewer days in hospital (p = 0.13), lower in-hospital mortality (p = 0.12) and lower in-hospital mortality plus nonfatal thrombotic event occurrences (p = 0.10) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Clinical outcomes

| DM | No DM (n = 73) | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metformin (n = 34) | No Metformin (n = 41) | Metformin vs. no metformin | Metformin vs. no DM | No metformin vs. No DM | ||

| Days in hospital | 11.6 ± 14.4 | 17.5 ± 19.7 | 8.7 ± 4.8 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.001 |

| Intubation required (%) | 5.8 | 24.4 | 15 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.21 |

| In-hospital mortality (%) | 8.8 | 22 | 11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| In-hospital mortality plus nonfatal thrombotic events (%) | 11.7 | 26.8 | 15.1 | 0.10 | 0.64 | 0.13 |

Non-fatal thrombotic events include type 1 myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, pulmonary embolism

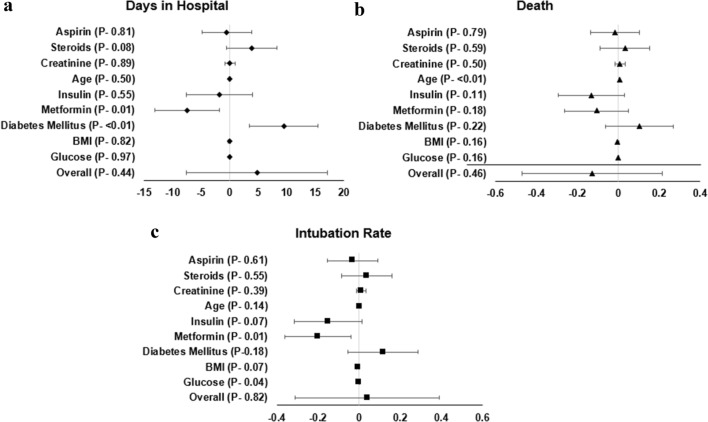

Multiple regression analysis revealed that days in hospital was positively associated with DM (Odds Ratio(OR) [95% confidence interval 9.5 [3.5 to 15.4] p < 0.01) and negatively associated with metformin use (OR [95% CI] − 7.4[− 1.7 to 13.1], (p < 0.01)); death was associated with age OR [95% CI] 0.005(0.002 to 0.008], p < 0.010; intubation rate was associated with metformin use (OR [95% CI] − 0.2[− 0.04 to − 0.36], p = 0.01) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Multiple regression analysis demonstrating factors associate with days in hospital, death, and intubation rate

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this observational study is the first to explore the relationship between the known biomarkers associated with inflammation associated with COVID-19 infection and clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients with DM treated with and without metformin. In our study, metformin treatment was associated with (a) significantly lower d-dimer, urinary L-FABP, and urinary 11-dh-TxB2 levels, (b) less disease severity with fewer days in hospital, and a (c) lower rate of intubation, in-hospital death and a composite of in-hospital death plus nonfatal thrombotic event occurrences.

SARS-CoV-1 virus can bind to the pancreatic islet ACE2 receptor causing acute islet cell damage and new onset DM [20]. The presence of preexisting or new onset DM further worsens the outcomes of COVID-19, since both diseases are associated with hypercoagulability, inflammation, oxidative stress, elevated platelet reactivity, resistance to fibrinolysis, and endothelial dysfunction. It has been shown that COVID-19 patients with DM had nearly two times more death and disease severity compared to patients without DM [21]. Similarly, an association between hyperglycemia and increased COVID-19 related mortality has been reported in patients with type 2 DM [22, 23]. Therefore, glucose-lowering agents are a major treatment strategy in addition to standard COVID-19 medications in patients with DM. Metformin therapy is currently being compared to placebo in COVID-19 patients in the ongoing METCOVID trial (NCT04510194).

The significant mortality benefit associated with metformin may be due to its noncanonical effects in addition to its glucose lowering effect. Metformin has been shown to have complex mechanism of action, which in part exerts anti-viral and anti-inflammatory affects [10, 24]. In the canonical pathway, metformin blocks complex-1 of the respiratory chain in mitochondria in hepatocytes, suppresses adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, and increases cytoplasmic adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-ATP ratio leading to the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). The AMPK phosphorylates the acetyl-CoA carboxylase that enhances insulin sensitivity and peripheral uptake of glucose and glucose consumption [25]. Metformin treatment has been shown to be associated with a 42% decrease in DM-related death and a 36% decrease in all cause death [26]. With respect to noncanonical pathways, in vitro studies of endothelial cells have shown that metformin enhances nitric oxide production by activating the AMPK pathway and inhibits the activation of the NF-κB pathway and generation of inflammatory cytokines [27]. Thus, metformin appears to reduce the inflammatory response through inhibition of the NF-κB pathway in patients with COVID-19. However, thus far, evidence for metformin-induced attenuation of inflammatory response or tissue damage as indicated by laboratory measures and its link to clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 is limited. A randomized study demonstrated that metformin is associated with reduced levels of inflammatory markers including tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) [28]. In a retrospective study, metformin treated patients with COVID-19 had decreased level of IL-6, but its relation to clinical outcomes were not reported [29].

In the current study, our data suggest that metformin therapy is associated with a significant decrease in D-dimer levels in patients with COVID-19 and DM. An association between high D-dimer levels and poor COVID-19 prognosis and elevated mortality is well established. However, we were not able to show the same relation with thromboelastography measurements and other standard biomarkers of COVID-19. The latter may be due to the lower number of patients enrolled in this observational study. The SOFA score, an indicator of the severity of illness was significantly lower in DM patients treated with metformin prior to hospitalization. The percentage of patients with renal disease were significantly lower in DM patients treated with metformin and were similar in COVID-19 patients without DM. This may be mainly due to metformin being contraindicated in patients with renal insufficiency. There were no other significant differences in demographics and co-morbidities amongst patients with DM treated with and without metformin.

L-FABP, a carrier protein involved in the intracellular transport of free fatty acids, is expressed in the proximal renal tubules and is excreted in urine following tubular damage [30, 31]. It has been reported that urinary L-FABP levels increase before serum creatinine in patients with acute kidney injury and may predict the severity of COVID-19 at an early stage [32]. U11-dh TxB2 is a marker of platelet activation and whole-body inflammation. Thromboxane A2 biosynthesis is contributed by platelets, leukocytes, and endothelial cell sources [33]. The independent relation of u11-dh TxB2 to adverse outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease and diabetes treated with aspirin has been demonstrated in major clinical trials [34–36]. Urinary 8-OHdG is one of the most widely studied biomarker of oxidative stress-induced deoxyribonucleic acid damage [37]. It has been shown to be associated with cardiovascular disease and endothelial dysfunction in patients with diabetes [37–40]. In our study, urinary L-FABP and 11-dh-TxB2 were significantly lower in metformin-treated patients and we also observed lower levels of 8-OHdG in metformin-treated patients. Finally, metformin treatment in COVID-19 patients was independently associated with a lower rate of intubation requirement and shorter hospital stay. Most of our findings resonate findings from other observational retrospective studies highlighting improved COVID-19 disease outcomes in patients on metformin [7, 10, 24, 28, 29, 41–44]. The main limitation of this study is the limited number of patients enrolled affecting the power to detect differences between groups. Hence, the findings from this observational sub-analysis are hypothesis generating and these effects of metformin should be explored in future translational research studies.

In conclusion, metformin therapy in patients with COVID-19 and DM was associated with lower D-dimer, L-FABP and 11-dh-TxB2 levels, and lower rate of intubation. Shorter hospital stay, and non-significantly lower rates of in-hospital death and in-hospital death plus thrombotic event occurrences were also notable. In a multiple regression analysis, metformin use was associated with a lower rate of intubation requirement, and shorter hospital stay.

Acknowledgements

Haemonetics donated instrument and cartridges for thromboelastography, u11-dh TxB2 samples were processed by Inflammatory Markers Laboratory. Part of the study was published as Gurbel PA, et al. Bedside thromboelastography to rapidly assess the pharmacodynamic response of anticoagulants and aspirin in COVID-19: evidence of inadequate therapy in a predominantly minority population. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021:1–3.

Funding

Platelet and Thrombosis Research, LLC, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Gurbel reports grants and personal fees from Bayer HealthCare LLC, Otitopic Inc, Amgen, Janssen, and US WorldMeds LLC; grants from Instrumentation Laboratory, Haemonetics, Medicure Inc, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals, and Hikari Dx; personal fees from UpToDate; Dr Gurbel is a relator and expert witness in litigation involving clopidogrel; in addition, Dr. Gurbel has two patents, Detection of restenosis risk in patients issued and Assessment of cardiac health and thrombotic risk in a patient. Dr. Tantry reports receiving honoraria from UptoDate and Aggredyne. Other authors report no disclosures.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Apicella M, Campopiano MC, Mantuano M, Mazoni L, Coppelli A, Del Prato S. COVID-19 in people with diabetes: understanding the reasons for worse outcomes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:782–792. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30238-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viswanathan V, Puvvula A, Jamthikar AD, et al. Bidirectional link between diabetes mellitus and coronavirus disease 2019 leading to cardiovascular disease: a narrative review. World J Diabetes. 2021;12:215–237. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v12.i3.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J. Factors associated with hospitalization and critical illness among 4,103 patients with COVID-19 disease in New York City. BMJ. 2020;369:1966. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roncon L, Zuin M, Rigatelli G, Zuliani G. Diabetic patients with COVID-19 infection are at higher risk of ICU admission and poor short-term outcome. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104354. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saha S, Al-Rifai RH, Saha S (2021) Diabetes prevalence and mortality in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. J Diabetes Metab Disord 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Lazarus G, Audrey J, Wangsaputra VK, et al. High admission blood glucose independently predicts poor prognosis in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;171:108561. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo P, Qiu L, Liu Y, et al. Metformin treatment was associated with decreased mortality in COVID-19 patients with diabetes in a retrospective analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:69–72. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lukito AA, Pranata R, Henrina J, et al. The effect of metformin consumption on mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:2177–2183. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khunti K, Knighton P, Zaccardi F, et al. Prescription of glucose-lowering therapies and risk of COVID-19 mortality in people with type 2 diabetes: a nationwide observational study in England. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9:293–303. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00050-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghany R, Palacio A, Dawkins E, et al. Metformin is associated with lower hospitalizations, mortality and severe coronavirus infection among elderly medicare minority patients in 8 states in USA. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;15:513–518. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kajiwara C, Kusaka Y, Kimura S, et al. Metformin mediates protection against legionella pneumonia through activation of AMPK and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. J Immunol. 2018;200:623–631. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly B, Tannahill GM, Murphy MP, O’Neill LAJ. Metformin inhibits the production of reactive oxygen species from NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase to limit induction of Interleukin-1b (IL-1b) and boosts Interleukin-10 (IL-10) in Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:20348–20359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.662114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaneto H, Kimura T, Obata A, et al. Multifaceted mechanisms of action of metformin which have been unraveled one after another in the long history. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:2596. doi: 10.3390/ijms22052596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Tantry US, et al. First report of the point-of-care TEG: a technical validation study of the TEG-6S system. Platelets. 2016;27:642–649. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2016.1153617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Tantry US. Defining platelet response to acetylsalicylic acid: the relation between inhibition of serum thromboxane B2 and agonist-induced platelet aggregation. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02334-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Endo K, Miyashita Y, Sasaki H, et al. Probucol and atorvastatin decrease urinary 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine in patients with diabetes and hypercholesterolemia. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2006;13:68–75. doi: 10.5551/jat.13.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katagiri D, Doi K, Honda K, Negishi K, et al. Combination of two urinary biomarkers predicts acute kidney injury after adult cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White-Dzuro G, Gibson LE, Zazzeron L, et al. Multisystem effects of COVID-19: a concise review for practitioners. Postgrad Med. 2021;133:20–27. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2020.1823094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang JK, Lin SS, Ji XJ, Guo LM. Binding of SARS coronavirus to its receptor damages islets and causes acute diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2010;47:193–199. doi: 10.1007/s00592-009-0109-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar A, Arora A, Sharma P, Anikhindi SA, Bansal N, Singla V, Khare S, Srivastava A. Is diabetes mellitus associated with mortality and severity of COVID-19? A meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:535–545. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu L, She Z-G, Cheng X, et al. Association of blood glucose control and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and pre-existing type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2020;31:1068–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holman N, Knighton P, Kar P, et al. Risk factors for COVID-19-related mortality in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in England: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:823–833. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30271-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crouse AB, Grimes T, Li P, et al. Metformin use is associated with reduced mortality in a diverse population with COVID-19 and diabetes. Front Endocrinol. 2021;11:600439. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.600439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samuel SM, Varghese E, Büsselberg D (2021) Therapeutic potential of metformin in COVID-19: reasoning for its protective role. Trends Microbiol. S0966–842X(21)00063–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34) Lancet. 1998;352:854–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bai B, Chen H. Metformin: a novel weapon against inflammation. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:622262. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.622262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen W, Liu X, Ye S. Effects of metformin on blood and urine pro-inflammatory mediators in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Inflamm (Lond) 2016;13:34. doi: 10.1186/s12950-016-0142-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y, Yang D, Cheng B, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with diabetes and COVID-19 in association with glucose-lowering medication. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:1399–1407. doi: 10.2337/dc20-0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torigoe K, Muta K, Tsuji K, et al. Urinary liver-type fatty acid-binding protein predicts residual renal function decline in patients on peritoneal dialysis. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e928236. doi: 10.12659/MSM.928236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Negishi K, Noiri E, Doi K, et al. Monitoring of urinary L-type fatty acid-binding protein predicts histological severity of acute kidney injury. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(1154–59):25. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katagiri D, Ishikane M, Asai Y, et al. Evaluation of coronavirus disease 2019 severity using urine biomarkers. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2:e0170. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tantry US, Mahla E, Gurbel PA. Aspirin resistance. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;52:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eikelboom JW, Hirsh J, Weitz JI, et al. Aspirin-resistant thromboxane biosynthesis and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2002;105:1650–1655. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013777.21160.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eikelboom JW, Hankey GJ, Thom J, et al. Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management and Avoidance (CHARISMA) Investigators. Incomplete inhibition of thromboxane biosynthesis by acetylsalicylic acid: determinants and effect on cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2008;118:1705–1712. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.768283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rocca B, Buck G, Petrucci G, et al. Thromboxane metabolite excretion is associated with serious vascular events in diabetes mellitus: a sub-study of the ASCEND trial. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(2):ehaa946. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graille M, Wild P, Sauvain JJ, et al. Urinary 8-OHdG as a biomarker for oxidative stress: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:3743. doi: 10.3390/ijms21113743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tousoulis D, Papageorgiou N, Androulakis E, et al. Diabetes mellitus-associated vascular impairment: novel circulating biomarkers and therapeutic approaches. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:667–676. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Minno A, Turnu L, Porro B, et al. 8-Hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine levels and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2016;24:548–555. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valavanidis A, Vlachogianni T, Fiotakis C, et al. “8-Hydroxy2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG): a critical biomarker of oxidative stress and carcinogenesis. J Environ Sci Health C. 2009;27:120–139. doi: 10.1080/10590500902885684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bigagli E, Lodovici M. Circulating oxidative stress biomarkers in clinical studies on type 2 diabetes and its complications. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:5953685. doi: 10.1155/2019/5953685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheen AJ. Metformin and COVID-19: from cellular mechanisms to reduced mortality. Diabetes Metab. 2020;46:423–426. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lalau JD, Al-Salameh A, Hadjadj S, et al. Metformin use is associated with a reduced risk of mortality in patients with diabetes hospitalised for COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. 2021;47:101216. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2020.101216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han T, Ma S, Sun C, et al. The association between anti-diabetic agents and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Med Res. 2021;S0188–4409(21):00167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]