ABSTRACT

Background

The tryptophan–kynurenine pathway is linked to inflammation. We hypothesize that metabolites implicated in this pathway may be associated with the risk of heart failure (HF) or atrial fibrillation (AF) in a population at high risk of cardiovascular disease.

Objectives

We aimed to prospectively analyze the associations of kynurenine-related metabolites with the risk of HF and AF and to analyze a potential effect modification by the randomized interventions of the PREDIMED (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea) trial with Mediterranean diet (MedDiet).

Methods

Two case–control studies nested within the PREDIMED trial were designed. We selected 324 incident HF cases and 502 incident AF cases individually matched with ≤3 controls. Conditional logistic regression models were fitted. Interactions with the intervention were tested for each of the baseline plasma metabolites measured by LC–tandem MS.

Results

Higher baseline kynurenine:tryptophan ratio (OR for 1 SD: 1.20; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.43) and higher levels of kynurenic acid (OR: 1.19; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.40) were associated with HF. Quinolinic acid was associated with AF (OR: 1.15; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.32) and HF (OR: 1.25; 95% CI: 1.04, 1.49). The MedDiet intervention modified the positive associations of kynurenine (Pinteraction = 0.006), kynurenic acid (Pinteraction = 0.008), and quinolinic acid (Pinteraction = 0.033) with HF and the association between kynurenic acid and AF (Pinteraction = 0.02).

Conclusions

We found that tryptophan–kynurenine pathway metabolites were prospectively associated with higher HF risk and to a lesser extent with AF risk. Moreover, an effect modification by MedDiet was observed for the association between plasma baseline kynurenine-related metabolites and the risk of HF, showing that the positive association of increased levels of these metabolites and HF was restricted to the control group.

Keywords: tryptophan, kynurenine, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, metabolomics, Mediterranean diet, case–control, PREDIMED

Introduction

The kynurenine pathway is the main metabolic route of degradation of tryptophan, an essential human amino acid. Cytokines, such as ILs, IFN-α and -γ, or TNF, have been shown to tightly regulate the activity of the enzymes implicated in the conversion of tryptophan into kynurenine and the rest of the pathway conversion steps (1). Moreover, tryptophan-related metabolites are also regulators of the inflammatory response (1), suggesting an important role of this pathway in inflammation.

The increased prevalence, during the past decade, of atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure (HF) has boosted their recognition as major public health problems (2, 3). Although they are different diseases, AF and HF share some important pathophysiological features, including inflammation (3). Increasing evidence links inflammation to the onset and perpetuation of AF (4). In this context, several inflammatory markers and mediators have been associated with the pathogenesis of AF (5). Similarly, inflammation-related metabolic pathways have been linked to HF and to a worse clinical progression of this disease (6, 7).

Consequently, assessing associations between the tryptophan–kynurenine pathway and the subsequent risk of AF and HF could help to clarify the links of inflammation with AF and HF. In addition, exploration of other metabolic pathways of tryptophan such as the serotonin pathway and the gut bacteria pathway of tryptophan-indole-3-propionic acid could provide a more complete overview of the potential association of tryptophan-related metabolites and HF or AF.

Consequently, our first objective was to analyze, in 2 case–control studies nested within the PREDIMED (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea) trial, the association between plasma metabolites implicated in degradation pathways of tryptophan and subsequent risk of AF or HF. Our second aim was to analyze the potential effect modification by 2 Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) interventions in the PREDIMED trial on the relation between the studied metabolites and the risk of AF or HF. Finally, we also explored the serotonin pathway and the gut bacterial pathway of tryptophan-indole-3-propionic acid in their association with AF and HF.

Methods

Population and design

The design and methods of the PREDIMED trial have been previously described (8). From 2003 to 2009, 7447 Spanish participants at high risk of cardiovascular disease were recruited in 11 different sites. Participants were women or men aged 55–80 y, with type 2 diabetes (T2D) or with ≥3 of the following cardiovascular disease risk factors: BMI (in kg/m2) ≥25, current smoking, hypertension, high concentrations of LDL cholesterol, low concentrations of HDL cholesterol, or family history of early coronary artery disease. Participants were allocated to a MedDiet supplemented with extra virgin olive oil (EVOO), a MedDiet supplemented with mixed nuts, or a control diet. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all recruiting centers in PREDIMED.

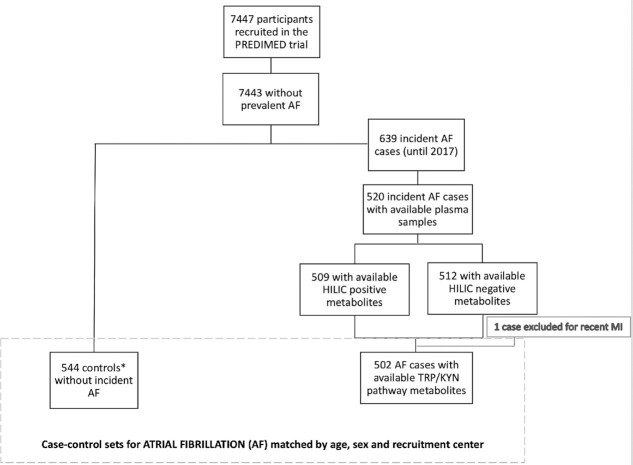

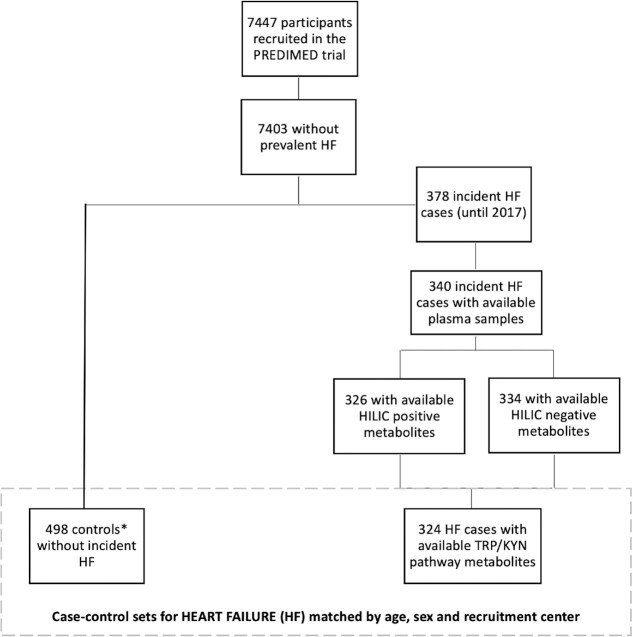

We designed 2 case–control studies nested within the PREDIMED trial. Initially 520 AF cases and 340 HF cases were considered after excluding prevalent cases and cases without plasma samples. Figures 1 and 2 show the flowcharts for both case–control studies. Incidence density sampling with replacement was used as the control sampling method (9). Thus, controls were randomly selected from all participants at risk at the time of the occurrence of the incident case, and selected controls could be selected again as a control for another index case and they could become a case later (9). One to 3 controls/case were matched by recruitment center, year of birth (±5 y), and sex.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of the case–control design for incident AF nested in the PREDIMED trial. *Incidence density sampling with replacement was used as the control sampling method. AF, atrial fibrillation; HILIC, hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography; PREDIMED, Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea; Trp–Kyn, tryptophan–kynurenine.

FIGURE 2.

Flowchart of the case–control design for incident HF nested in the PREDIMED trial. *Incidence density sampling with replacement was used as the control sampling method. HF, heart failure; HILIC, hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography; PREDIMED, Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea; Trp–Kyn, tryptophan–kynurenine.

Outcome ascertainment

HF and AF were a priori defined as secondary endpoints in the PREDIMED trial protocol (www.predimed.es). In this analysis, all HF and AF incident cases diagnosed from 2003 until December 2017 were included. One center stopped follow-up in December 2014 and all participants from this center were censored at this date to be selected as controls.

Information on these outcomes was collected from continuous contact with participants and primary health care physicians, annual follow-up visits, yearly ad hoc reviews of medical charts, and annual consultation of the National Death Index. Physicians blinded to the intervention group collected this information. If clinical diagnosis of HF or AF was found, clinical records of hospital discharge, outpatient clinic records, and family physicians’ records were obtained. Medical charts were sent codified to the Clinical End-Point Committee, whose members were also blinded to the intervention group. The documentation was independently evaluated by 2 cardiologists and if they did not agree on the classification of the event, consensus was reached via the consultation of a third cardiologist (the committee's chair). In some cases, more information was requested to complete the adjudication. The End-Point Committee adjudicated the events according to prespecified criteria in a “Manual of operations.”

The diagnosis criteria for the HF events were defined according to the 2005 guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (10). Patients were diagnosed as having symptoms and/or signs of HF (more frequently breathlessness or fatigue at rest or during exertion, or ankle swelling) attributable to objective evidence of cardiac dysfunction at rest (preferably by echocardiography). AF was initially identified from an annual review of all outpatient and inpatient medical records of each participant or yearly electrocardiograms (ECGs) performed during follow-up examinations in the health care centers. If AF was mentioned anywhere in the medical record or AF was present in the ECG, all relevant documentation was submitted to the Clinical End-Point Committee. A diagnosis of AF was made only if both AF was present in an ECG tracing and an explicit medical diagnosis of AF was made by a physician. AF events associated with myocardial infarction (MI) or cardiac surgery were not included (subjects with an AF diagnosis within 20 d after an MI/cardiac surgery were excluded) (11).

Sample collection and metabolomic analysis

During the baseline visit, participants provided blood samples after at least an 8-h fast. All samples were processed at each recruiting center no later than 2 h after collection and stored at −80°C until their analysis. Samples from matched case–control pairs were shipped and assayed in the same analytical run, randomly sorted to reduce bias and interassay variability.

LC–tandem MS was used to measure polar plasma metabolites. Kynurenic acid, tryptophan, hydroxyanthranilic acid, serotonin, and indole-3-propionic acid were measured using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) coupled with high-resolution positive ion mode MS detection, whereas kynurenine and quinolinic acid were measured using HILIC and targeted negative ion mode MS detection as described previously (12, 13). Metabolomic analyses were performed at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. A more detailed description can be found in the supplementary material.

For the tryptophan–kynurenine pathway we could analyze 5 metabolites that were determined under the targeted approach: tryptophan, kynurenine, kynurenic acid, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, and quinolinic acid (Supplemental Figure 1). We also calculated the ratio of kynurenine to tryptophan, which is a good proxy of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) activity, and it may provide an even better approach than the analysis of the absolute tryptophan or kynurenine concentrations (14). To complete the study, we explored other metabolic pathways of tryptophan, so we also included serotonin (tryptophan–serotonin pathway) and indole-3-propionic acid to consider the tryptophan degradation pathway by gut bacteria. Both metabolites were also determined under the targeted approach as previously described.

Covariates

Baseline questionnaires were used to collect sociodemographic data, lifestyle variables, prevalent and family history of diseases, and medication use. Leisure-time physical activity was measured with the validated version of the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity questionnaire (15).

Statistical analysis

Individual metabolite values were normalized and scaled in multiples of 1 SD with Blom's inverse normal transformation (16). Mean ± SD was used to describe quantitative traits and percentages to describe categorical variables.

We fitted conditional logistic regression models to account for the matching between cases and controls. In these conditional logistic models we calculated matched ORs and their 95% CIs for HF or AF considering the first quartile as the reference category. Quartile cutoffs were calculated according to the distribution of metabolites among controls (participants without HF or AF through the follow-up). We also calculated the matched ORs for the SD of each metabolite, including them as continuous variables. We fitted crude and multivariable models adjusted for intervention group (MedDiet + EVOO, MedDiet + nuts, or control), smoking status (never/current/former), BMI, leisure-time physical activity [metabolic equivalent task (METs)-min/d], prevalent chronic conditions at baseline (hypertension, T2D, and dyslipidemia), family history of premature coronary artery disease (CAD), and education level (primary school or lower/secondary school or higher).

In addition, we calculated scores (separately for AF and HF) combining all the tryptophan–kynurenine pathway metabolites weighted with the respective individual coefficients from the fitted multivariable conditional logistic regression models. These scores were introduced as continuous (per 1 SD increase) and as quartiles into the conditional logistic models adjusted for the same confounders as aforementioned.

To consider the interrelation between metabolites and AF or HF, we also ran structural equation modeling analyses (considering only the control group) adjusted for age, sex, and recruiting center. Tryptophan, kynurenine, kynurenic acid, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, and quinolinic acid were introduced simultaneously into the model. Pathway diagrams were also built with the structural equation models to better observe correlations between metabolites.

Interactions between each metabolite as continuous (per 1 SD increase) and the intervention as dichotomous (control/MedDiet) were tested using conditional logistic models adjusted for smoking status (never/current/former), BMI, leisure-time physical activity (METs-min/d), prevalent chronic diseases (hypertension, T2D, and dyslipidemia), family history of premature CAD, and education level (primary school or lower/secondary school or higher). In addition, adjustment for propensity scores that used 30 baseline variables to estimate the probability of assignment to each of the intervention groups and robust variance estimators were used to consider that a small percentage of participants were nonindividually randomly assigned to the intervention groups and that minor imbalances in baseline covariates existed in the trial (8). The P values for the interactions were calculated using the likelihood ratio test for each scenario. We also repeated these analyses introducing a 2-df product term considering the 3 arms of the intervention (control/MedDiet + EVOO/MedDiet + nuts) and each metabolite as continuous (per 1-SD increase).

Moreover, as an ancillary analysis, if the interaction of any of the metabolites and MedDiet resulted in statistical significance, we ran a new conditional logistic model including a joint variable that considered the metabolite as dichotomous (below/above the median) and the intervention with MedDiet (MedDiet compared with control).

All the statistical procedures were carried out with Stata 16 software (Stata Corp.).

Results

In these 2 case–control studies nested within the PREDIMED trial, the number of incident cases of AF was 502 (Figure 1) and the number of incident cases of HF was 324 (Figure 2).

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of participants according to disease status for both sets of case–control studies. We observed that both incident AF and HF cases were more likely to show hypertension and T2D and to belong to the PREDIMED control group.

TABLE 1.

Baseline participant characteristics of HF and AF incident cases and controls1

| Case–control sets for AF | Case–control sets for HF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (n = 544) | AF cases (n = 502) | Controls (n = 498) | HF cases (n = 324) | |

| Age, y | 68.4 ± 6.2 | 68.2 ± 6.1 | 70.2 ± 5.9 | 70.3 ± 5.8 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.7 ± 3.8 | 30.7 ± 3.8 | 29.2 ± 3.6 | 31.1 ± 3.8 |

| Leisure-time physical activity, METs min/d | 233 ± 225 | 226 ± 215 | 212 ± 218 | 217 ± 205 |

| Female | 50.0 | 49.8 | 54.8 | 58.3 |

| Hypertension | 82.0 | 88.2 | 82.2 | 87.3 |

| Dyslipidemia | 69.7 | 65.5 | 68.6 | 64.2 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 50.9 | 48.0 | 51.8 | 59.3 |

| Family history of premature CAD | 20.4 | 19.1 | 20.1 | 19.4 |

| Education | ||||

| Elementary or lower | 79.4 | 75.9 | 81.7 | 84.9 |

| Secondary or higher | 20.6 | 24.1 | 18.3 | 15.1 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never smokers | 58.1 | 58.8 | 62.1 | 59.9 |

| Current smokers | 14.0 | 14.3 | 11.3 | 14.5 |

| Former smokers | 27.9 | 26.9 | 26.6 | 25.6 |

| Intervention arm of the trial | ||||

| Control | 34.0 | 37.3 | 36.4 | 36.4 |

| MedDiet + EVOO | 36.9 | 31.9 | 37.9 | 30.9 |

| MedDiet + Nuts | 29.0 | 30.9 | 25.6 | 32.7 |

Values are means ± SDs or percentages. AF, atrial fibrillation; CAD, coronary artery disease; EVOO, extra virgin olive oil; HF, heart failure; MET, metabolic equivalent task.

In the present study, first, we analyzed the association between the metabolites implicated in the degradation pathways of tryptophan and AF risk. Raw analyses for the tryptophan–kynurenine pathway showed significant association for the upper compared with the lower quartile for kynurenine (OR: 1.41; 95% CI: 1.00, 2.01) and quinolinic acid (OR: 1.48; 95% CI: 1.03, 2.13; data not shown). When we repeated the analysis considering the metabolites as continuous, we found significant associations for kynurenine, quinolinic acid, and the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio with AF risk (ORfor 1 SD increase: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.30; OR: 1.20; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.37; and OR: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.30, respectively; data not shown). However, when we fitted the multivariable-adjusted models (Table 2) most of the associations were not statistically significant. Only quinolinic acid showed a significant association with AF (ORfor 1 SD increase: 1.15; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.32) in a conditional logistic model adjusted for intervention group, BMI, smoking, leisure-time physical activity, prevalent chronic diseases (dyslipidemia, hypertension, and T2D), family history of CAD, and education level (Table 2). Moreover, when all the metabolites were considered together in a structural equation model, none of the associations between the metabolites and AF reached statistical significance (Supplemental Table 1). However, when we analyzed the association between the weighted score (combining tryptophan, kynurenine, kynurenic acid, hydroxyanthranilic acid, and quinolinic acid) and AF in a conditional logistic model adjusted for the same confounders (Supplemental Table 2), we observed that higher values of the score were associated with a higher risk of AF (ORfor 1 SD increase: 1.15; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.32). The analysis of the other pathways of tryptophan degradation, serotonin and indole-3-propionic acid, did not show any statistically significant association, neither in the crude nor in the multivariable model (ORfor 1 SD increase: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.85, 1.13; P = 0.786 and ORfor 1 SD increase: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.85, 1.13; P = 0.788, respectively, in the fully adjusted model; data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Associations between baseline plasma tryptophan–kynurenine pathway metabolites and incident atrial fibrillation1

| Q1 (n = 299)2 | Q2 (n = 311)2 | Q3 (n = 310)2 | Q4 (n = 304)2 | P-linear trend | Per 1 SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tryptophan | Ref. | 1.01 (0.72, 1.40) | 1.01 (0.71, 1.43) | 0.91 (0.63, 1.30) | 0.625 | 0.98 (0.86, 1.11) |

| Kynurenine | Ref. | 1.14 (0.81, 1.61) | 0.93 (0.64, 1.35) | 1.19 (0.82, 1.73) | 0.550 | 1.09 (0.95, 1.24) |

| Kyn:Trp ratio | Ref. | 1.25 (0.88, 1.77) | 1.46 (1.03, 2.08) | 1.26 (0.86, 1.86) | 0.173 | 1.10 (0.96, 1.26) |

| Kynurenic acid | Ref. | 1.36 (0.96, 1.91) | 1.05 (0.75, 1.49) | 1.09 (0.76, 1.56) | 0.942 | 0.98 (0.86, 1.11) |

| 3-Hydroxyanthranilic acid | Ref. | 0.85 (0.58, 1.25) | 1.55 (1.11, 2.18) | 0.91 (0.62, 1.34) | 0.602 | 1.00 (0.87, 1.16) |

| Quinolinic acid | Ref. | 1.12 (0.76, 1.63) | 1.37 (0.95, 1.97) | 1.37 (0.93, 2.01) | 0.064 | 1.15 (1.01, 1.32) |

Values are matched ORs (95% CIs) unless otherwise indicated. The multivariable conditional logistic model adjusted for intervention group (Mediterranean diet or control group), BMI (kg/m2), smoking (never, current, former), leisure-time physical activity (metabolic equivalent tasks; min/d), prevalent chronic conditions at baseline (dyslipidemia, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes), family history of coronary artery disease, and education level (primary or lower/secondary or higher). Kyn:Trp, kynurenine to tryptophan; Q, quartile.

These numbers refer to the quartiles calculated for tryptophan and slightly vary for other metabolites because they were calculated for each metabolite considering only controls, and cases were included according to those values.

Second, we analyzed the associations of tryptophan metabolic pathways with HF. In the crude analyses, we observed significant associations of these metabolites with higher risk of HF, with an ORfor 1 SD increase of 1.19 (95% CI: 1.02, 1.39) for kynurenine, 1.25 (95% CI: 1.07, 1.47) for the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio, 1.23 (95% CI: 1.06, 1.43) for kynurenic acid, and 1.29 (95% CI: 1.10, 1.51) for quinolinic acid (data not shown). When we applied the multivariable adjustment to the conditional logistic models, we observed (Table 3) that the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio was associated with a higher risk of HF, showing a P for linear trend across quartiles of P = 0.017 and an ORfor 1 SD increase of 1.20 (95% CI: 1.01, 1.43). We also observed that higher levels of kynurenic acid (ORfor 1 SD increase: 1.19; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.40) and quinolinic acid (ORfor 1 SD increase: 1.25; 95% CI: 1.04, 1.49) were associated with a higher risk of HF (Table 3). When all the metabolites were considered together in a structural equation model, kynurenic acid showed a statistically significant association with HF (ORfor 1 SD increase: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.14), as seen in Supplemental Table 3 and in Supplemental Figure 2 (β coefficients of the model and covariances between metabolites are shown).

TABLE 3.

Associations between baseline plasma tryptophan–kynurenine pathway metabolites and incident heart failure1

| Q1 (n = 219)2 | Q2 (n = 199)2 | Q3 (n = 210)2 | Q4 (n = 189)2 | P-linear trend | Per 1 SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tryptophan | Ref. | 0.67 (0.43, 1.05) | 0.92 (0.61, 1.39) | 0.82 (0.51, 1.30) | 0.593 | 0.91 (0.77, 1.08) |

| Kynurenine | Ref. | 1.24 (0.77, 2.00) | 1.06 (0.65, 1.73) | 1.32 (0.82, 2.11) | 0.319 | 1.12 (0.94, 1.33) |

| Kyn:Trp ratio | Ref. | 0.92 (0.56, 1.51) | 1.00 (0.61, 1.62) | 1.66 (1.03, 2.68) | 0.017 | 1.20 (1.01, 1.43) |

| Kynurenic acid | Ref. | 1.15 (0.71, 1.85) | 1.31 (0.84, 2.06) | 1.52 (0.96, 2.42) | 0.061 | 1.19 (1.01, 1.40) |

| 3-Hydroxyanthranilic acid | Ref. | 1.25 (0.77, 2.02) | 1.56 (0.96, 2.53) | 1.13 (0.67, 1.90) | 0.544 | 0.98 (0.81, 1.18) |

| Quinolinic acid | Ref. | 0.86 (0.52, 1.43) | 1.32 (0.82, 2.12) | 1.43 (0.87, 2.36) | 0.060 | 1.25 (1.04, 1.49) |

Values are matched ORs (95% CIs) unless otherwise indicated. The multivariable conditional logistic model adjusted for intervention group (Mediterranean diet or control group), BMI (in kg/m2), smoking (never, current, former), leisure-time physical activity (metabolic equivalent tasks; min/d), prevalent chronic conditions at baseline (dyslipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes), family history of coronary artery disease, and education level (primary or lower/secondary or higher). Kyn:Trp, kynurenine to tryptophan; Q, quartile.

These numbers refer to the quartiles calculated for tryptophan and slightly vary for other metabolites because they were calculated for each metabolite considering only controls, and cases were included according to those values.

When we analyzed the association between the weighted score (combining tryptophan, kynurenine, kynurenic acid, hydroxyanthranlic acid, and quinolinic acid) and HF in a conditional logistic model adjusted for the same confounders (Supplemental Table 2), we observed that higher values of the score were associated with higher risk of HF, showing a P for linear trend across quartiles of P = 0.008 and an ORfor 1 SD increase of 1.29 (95% CI: 1.09, 1.54).

As we did for AF, we also analyzed the other pathways of degradation of tryptophan and we found an ORfor 1 SD increase of 0.94 (95% CI: 0.78, 1.13) for serotonin and of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.78, 1.12) for indole-3-propionic acid, showing null associations for both metabolites (data not shown).

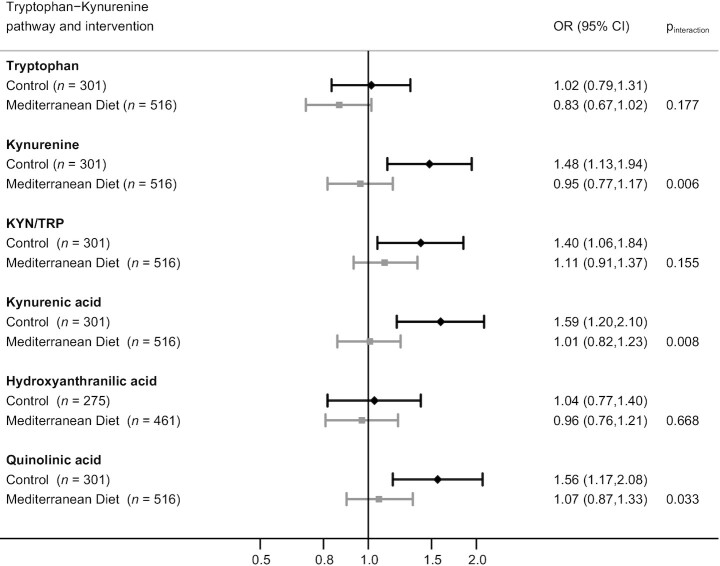

Finally, we analyzed the potential interactions between the randomized PREDIMED interventions with MedDiet (both MedDiet groups merged compared with the control group) and the metabolites implicated in the tryptophan–kynurenine pathways (as continuous variables) on the risk of AF and HF. In the case of AF only kynurenic acid exhibited a statistically significant interaction with MedDiet (P = 0.02) in the multivariable-adjusted model, showing that the risk of AF was higher in participants allocated to the control group (ORfor 1 SD increase: 1.21; 95% CI: 0.98, 1.49) than in subjects allocated to the MedDiet groups (ORfor 1 SD increase: 0.90; 95% CI: 0.77, 1.04; data not shown). When we tested the interaction considering each MedDiet group separately and each of the metabolites, no significant interactions were found.

In Figure 3, the results for the interaction analyses (considering both MedDiet groups together) on HF are shown. We found statistically significant interactions with MedDiet for kynurenine (P = 0.006), kynurenic acid (P = 0.008), and quinolinic acid (P = 0.033), showing that the MedDiet interventions modified the effect of the 3 metabolites on HF incidence: the higher risk of HF associated with higher levels of these metabolites was absent in the groups receiving the MedDiet interventions. A higher risk of HF was observed for higher levels of kynurenine, kynurenic acid, and quinolinic acid only in those subjects allocated to the control group. Supplemental Figure 3 shows the analyses for the interactions considering the MedDiet groups separately. We observed statistically significant interactions for tryptophan (P = 0.032), kynurenine (P = 0.005), and kynurenic acid (P = 0.003) on HF, showing that subjects allocated to the MedDiet supplemented with EVOO did not present the higher risk of HF conferred by kynurenine and kynurenic acid. In addition, higher levels of tryptophan were associated with a reduced risk of HF in the MedDiet + EVOO group (Supplemental Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Matched ORs (95% CIs) for the association between baseline metabolites (1-SD increase) of the tryptophan–kynurenine pathway and incident heart failure (HF) within each PREDIMED (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea) study intervention arm [both MedDiet intervention groups merged together (n = 516) compared with the control group (n = 301)]. The multivariable model adjusted for BMI (in kg/m2), smoking (never, current, former), leisure-time physical activity (metabolic equivalent tasks; min/d), prevalent chronic conditions at baseline (dyslipidemia, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes), family history of coronary artery disease, education level (primary or lower/secondary or higher), and propensity scores predicting random assignment to account for small between-group imbalances at baseline. MedDiet, Mediterranean diet.

To support these results, in Supplemental Table 4, we could observe the risk of HF after classifying subjects according to high or low baseline kynurenine (above or below the median, respectively) and to MedDiet or control group. The reference group were subjects allocated to the control group who presented high baseline levels of kynurenine, which were those with the highest risk of HF. Compared with them, subjects with high baseline kynurenine but receiving the intervention with MedDiet presented a statistically significant lower risk of HF (ORfor 1 SD increase: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.38, 0.92). Regarding subjects with low baseline levels of kynurenine, we confirmed that subjects allocated to the control group presented a lower risk of HF (ORfor 1 SD increase: 0.44; 95% CI: 0.26, 0.74) than those with high levels of kynurenine. For subjects with baseline low levels of kynurenine we did not observe a significant reduction of the risk for MedDiet groups (Supplemental Table 4).

Discussion

In 2 case–control studies, nested within the PREDIMED trial, we observed that plasma metabolites implicated in the degradation of tryptophan through the kynurenine pathway were prospectively associated with HF and, to a lesser extent, with AF risk. When all the tryptophan–kynurenine metabolites were combined in weighted scores we observed statistically significant associations for higher values of the scores and higher risk of HF and AF. Individually, we observed that a higher kynurenine:tryptophan ratio and higher levels of kynurenic acid and quinolinic acid were associated with a higher risk of HF. Interestingly, interactions between the MedDiet and kynurenine, kynurenic, and quinolinic acids were found, showing that the positive associations of these metabolites with HF were restricted to the control group. Our findings suggested that the MedDiet interventions, especially when supplemented with EVOO, might counteract the potential detrimental effects of these metabolites on the risk of HF.

Tryptophan–kynurenine pathway metabolites have been previously associated with HF prognosis, i.e., quinolinic acid and the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio were associated with an increased risk of mortality in HF patients (HR: 1.80; 95% CI: 1.1, 2.9 and HR: 1.55; 95% CI: 1.1, 2.2, respectively) (17) and also with clinical severity of HF, i.e., compromised capacity to do exercise, higher concentrations of inflammatory biomarkers, and higher risk of death (18). The literature related to the kynurenine pathway and AF is scarce but these metabolites have been reported to be associated with some features of AF (19). One plausible hypothesis is that the link between the tryptophan–kynurenine pathway and HF and/or AF may be related to inflammation. It is known that cytokines regulate the tryptophan–kynurenine pathway at several steps (1). It has also been reported that the metabolites implicated in the tryptophan–kynurenine pathway have a regulatory role in inflammatory responses (1). However, owing to the nature of the present study we cannot establish causation and consequently we cannot conclude whether proinflammatory cytokines may be over-activating the tryptophan–kynurenine pathway or whether higher concentrations of kynurenine-related metabolites were responsible for activating the inflammatory response.

Elevated concentrations of kynurenine pathway metabolites have been previously related to other cardiovascular diseases, i.e., higher risk of acute coronary events for higher levels of the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio (HRper quartile increment: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.31) (20), as well as to a worse prognosis of cardiovascular disease, i.e., higher risk of cardiovascular death (HRper 1SD increment: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.09, 1.37) (21). In this context, our group previously reported an important association for kynurenic acid (HRper 1SD increment: 1.23; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.48) with a composite outcome of stroke, MI, and cardiovascular death (22).

On the other hand, we found that the MedDiet modified the association of various metabolites involved in the kynurenine pathway with HF risk: the detrimental effects expected for high concentrations of kynurenine pathway metabolites (kynurenine, kynurenic acid, and quinolinic acid) on HF risk were not observed for subjects allocated to either of the 2 PREDIMED MedDiet intervention groups, but they were present in the control group. The anti-inflammatory properties of MedDiet have been widely described previously (23, 24). Therefore, it could be possible that although a high inflammatory response may be expected owing to high concentrations of kynurenine-related metabolites, an intervention with the MedDiet may be counteracting this response through its anti-inflammatory effects. Consequently, the risk of HF related to high baseline levels of kynurenine-related metabolites may be counteracted by the intervention with MedDiet. It could also be possible that the MedDiet may reduce the activity of the enzymes implicated in the conversion steps of the kynurenine pathway by reducing the concentrations of inflammatory markers that activate those enzymes (1). Specifically, the MedDiet has been widely reported to reduce the concentrations of cytokines such as IL-6, IL-18, IL-1β, and TNF-α (25, 26), and some of these cytokines, IL-1β and TNF-α, regulate the enzymes implicated in the conversion of tryptophan to kynurenine and from kynurenine to kynurenic acid (1). Thus, it can be hypothesized that the MedDiet, by reducing the concentrations of cytokines, may be regulating the tryptophan–kynurenine pathway. We found a marked effect for the MedDiet + EVOO intervention in reducing the HF risk conferred by kynurenine-related metabolites, supporting the important anti-inflammatory properties of EVOO (27, 28) and suggesting a special role for this key component of a traditional MedDiet in the regulation of the tryptophan–kynurenine pathway. Unfortunately, in these nested case–control studies, repeated measurements of the metabolites were not available and, consequently, we could not analyze the effects of the MedDiet on changes in metabolites. However, we previously reported that the MedDiet, and especially when supplemented with EVOO, appeared to reduce plasma levels of kynurenine-related metabolites (29).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study analyzing the potential interactions between a MedDiet intervention and tryptophan–kynurenine pathway metabolites on the risk of subsequent AF or HF. The findings of our study support that the MedDiet may exert a protective role by acting on inflammation through the regulation of the tryptophan–kynurenine pathway. This protective role appears to be especially important for subjects presenting high levels of kynurenine-related metabolites.

The present study shows some limitations that need to be addressed. First, the number of cases is limited, especially for HF. Thus, further independent studies with a larger sample size would be needed to confirm our findings. Unfortunately, it was not possible to perform an external validation of our results, which would have been especially interesting for replicating the interactions between MedDiet and the kynurenine-related metabolites on HF risk. In spite of the sample size, our design may have been adequate to explore the effect modification by the MedDiet. Second, the methods used for the metabolomics measurements did not capture all the metabolites involved downstream in the tryptophan–kynurenine pathway. Nevertheless, we were able to analyze the most important downstream steps in this pathway. Third, we cannot generalize our results to other populations with different ethnicities, ages, lower prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors, or to nonvolunteers. Finally, although we adjusted for several confounders, residual confounding may still be present.

In conclusion, in these 2 case–control studies nested in the PREDIMED trial, we found that several plasma tryptophan–kynurenine pathway metabolites were prospectively associated with higher risk of HF and to a lesser extent with AF. Moreover, an effect modification by the MedDiet, especially when supplemented with EVOO, was observed for the association between kynurenine-related metabolites and HF, showing that the detrimental effects of these metabolites were restricted to the control group.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—CR, FBH, and MAM-G: designed the research; CBC, CD, MR-C, and CR: conducted the research; CR, MR-C, PH-A, and ET: performed the statistical analyses; CR: drafted the paper; MAM-G, ET, and MR-C: contributed to drafting the manuscript; MG-F and CW: critically reviewed the paper; and J Li, AA-G, M Fito, LL, DC, EG-G, RE, M Fiol, J Lapetra, LS-M, ER, FA, and JS-S: reviewed the final manuscript. All the authors approved the final manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Notes

Supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute research grant R01HL118264 (to FBH). The PREDIMED (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea) trial was supported by the official funding agency for biomedical research of the Spanish government, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, through grants provided to research networks specifically developed for the trial: RTIC G03/140 (to RE) during 2003–2005 and RTIC RD 06/0045 (to MAM-G) during 2006–2013 and through Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y Nutrición (to MAM-G); Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares grant CNIC 06/2007; Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria—Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional grants PI04-2239, PI 05/2584, CP06/00100, PI07/0240, PI07/1138, PI07/0954, PI 07/0473, PI10/01407, PI10/02658, PI11/01647, P11/02505, PI13/00462, and JR17/00022; Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación grants AGL-2009-13906-C02, AGL2010-22319-C03, and SAF2016-80532-R; Fundación Mapfre 2010 (which had no role in the design, implementation, analysis, or interpretation of the data); Consejería de Salud de la Junta de Andalucía grant PI0105/2007; Public Health Division of the Department of Health of the Autonomous Government of Catalonia; Generalitat Valenciana grants ACOMP06109, GVA-COMP2010-181, GVACOMP2011-151, CS2010-AP-111, PROMETEO 17/2017, and CS2011-AP-042; Fundació La Marató-TV3 grants 294/C/2015 and 538/U/2016 (which had no role in the design, implementation, analysis, or interpretation of the data); and Regional Government of Navarra grant P27/2011. PH-A is supported by Juan de la Cierva-Formación postdoctoral fellowship FJCI-2017-32205, funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades. MG-F was supported by American Diabetes Association grant #1-18-PMF-029. JS-S is supported in part by ICREA, under the ICREA Academia program.

Supplemental Figures 1–3 and Supplemental Tables 1–4 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/.

Abbreviations used: AF, atrial fibrillation; CAD, coronary artery disease; ECG, electrocardiogram; EVOO, extra virgin olive oil; HF, heart failure; HILIC, hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography; MedDiet, Mediterranean diet; MET, metabolic equivalent task; MI, myocardial infarction; PREDIMED, Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Contributor Information

Cristina Razquin, Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain; Navarra Health Research Institute (IdiSNA), Pamplona, Spain; CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain.

Miguel Ruiz-Canela, Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain; Navarra Health Research Institute (IdiSNA), Pamplona, Spain; CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain.

Estefania Toledo, Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain; Navarra Health Research Institute (IdiSNA), Pamplona, Spain; CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain.

Pablo Hernández-Alonso, CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain; Human Nutrition Unit, Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, Rovira i Virgili University, Reus, Spain; Endocrinology and Nutrition Clinical Management Unit, Virgen de la Victoria Hospital, Málaga Biomedical Research Institute (IBIMA), Málaga, Spain; Pere Virgili Health Research Institute (IISPV), San Joan de Reus University Hospital, Reus, Spain.

Clary B Clish, Broad Institute, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Marta Guasch-Ferré, Department of Nutrition, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Channing Division for Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Jun Li, Department of Nutrition, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Clemens Wittenbecher, Department of Nutrition, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Molecular Epidemiology, German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbruecke, Nuthetal, Germany; German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD), Neuherberg, Germany.

Courtney Dennis, Broad Institute, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Angel Alonso-Gómez, CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain; Bioaraba Health Research Institute, Osakidetza Basque Health Service, Araba University Hospital; University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain.

Montse Fitó, CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain; Unit of Cardiovascular Risk and Nutrition, Hospital del Mar Institute for Medical Research (IMIM), Barcelona, Spain.

Liming Liang, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Biostatistics, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Dolores Corella, CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain; Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain.

Enrique Gómez-Gracia, CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain; Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Málaga, Málaga, Spain.

Ramon Estruch, CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain; Department of Internal Medicine, August Pi i Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBAPS), Hospital Clinic, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Miquel Fiol, CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain; Clinical Trials Platform, Balearic Islands Health Research Institute (IdISBa), Son Espases University Hospital, Palma de Mallorca, Spain.

Jose Lapetra, CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain; Research Unit, Department of Family Medicine, Seville Primary Care Health District, Sevilla, Spain.

Lluis Serra-Majem, CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain; Nutrition Research Group, Research Institute of Biomedical and Health Sciences (IUIBS), University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain.

Emilio Ros, CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain; Lipid Clinic, Department of Endocrinology and Nutrition, August Pi i Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBAPS), Hospital Clinic, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Fernando Aros, CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain; Bioaraba Health Research Institute, Osakidetza Basque Health Service, Araba University Hospital; University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain.

Jordi Salas-Salvadó, CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain; Human Nutrition Unit, Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, Rovira i Virgili University, Reus, Spain; Pere Virgili Health Research Institute (IISPV), San Joan de Reus University Hospital, Reus, Spain.

Frank B Hu, Department of Nutrition, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; Channing Division for Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Miguel A Martínez-González, Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain; Navarra Health Research Institute (IdiSNA), Pamplona, Spain; CIBER Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition (CIBEROBN), Carlos III Institute of Health, Madrid, Spain; Department of Nutrition, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Data Availability

Data described in the article, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending approval from the PREDIMED Steering Committee and Institutional Review Boards.

References

- 1. Baumgartner R, Forteza MJ, Ketelhuth DFJ. The interplay between cytokines and the Kynurenine pathway in inflammation and atherosclerosis. Cytokine. 2019;122:154148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anter E, Jessup M, Callans DJ. Atrial fibrillation and heart failure: treatment considerations for a dual epidemic. Circulation. 2009;119:2516–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sharma PS, Callans DJ. Treatment considerations for a dual epidemic of atrial fibrillation and heart failure. J Atr Fibrillation. 2013;6(2):740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Korantzopoulos P, Letsas KP, Tse G, Fragakis N, Goudis CA, Liu T. Inflammation and atrial fibrillation: a comprehensive review. J Arrhythm. 2018;34:394–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guo Y, Lip GYH, Apostolakis S. Inflammation in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2263–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Petersen JW, Felker GM. Inflammatory biomarkers in heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2006;12:324–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deswal A, Petersen NJ, Feldman AM, Young JB, White BG, Mann DL. Cytokines and cytokine receptors in advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2001;103:2055–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, Covas MI, Corella D, Arós F, Gómez-Gracia E, Ruiz-Gutiérrez V, Fiol M, Lapetra Jet al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang M-H, Shugart YY, Cole SR, Platz EA. A simulation study of control sampling methods for nested case-control studies of genetic and molecular biomarkers and prostate cancer progression. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:706–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Swedberg K, Cleland J, Dargie H, Drexler H, Follath F, Komajda M, Tavazzi L, Smiseth OA, Gavazzi A, Haverich Aet al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure: executive summary (update 2005): The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(11):1115–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martínez-González MA, Toledo E, Arós F, Fiol M, Corella D, Salas-Salvadó J, Ros E, Covas MI, Fernández-Crehuet J, Lapetra Jet al. Extravirgin olive oil consumption reduces risk of atrial fibrillation: the PREDIMED (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea) trial. Circulation. 2014;130:18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paynter NP, Balasubramanian R, Giulianini F, Wang DD, Tinker LF, Gopal S, Deik AA, Bullock K, Pierce KA, Scott Jet al. Metabolic predictors of incident coronary heart disease in women. Circulation. 2018;137(8):841–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang TJ, Ngo D, Psychogios N, Dejam A, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Ghorbani A, O'Sullivan J, Cheng S, Rhee EPet al. 2-Aminoadipic acid is a biomarker for diabetes risk. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(10):4309–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mangge H, Stelzer I, Reininghaus EZ, Weghuber D, Postolache TT, Fuchs D. Disturbed tryptophan metabolism in cardiovascular disease. Curr Med Chem. 2014;21:1931–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Elosua R, Marrugat J, Molina L, Pons S, Pujol E. Validation of the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire in Spanish men. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:1197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blom G. Statistical estimates and transformed beta-variables. New York: John Wiley & Sons A/S; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lund A, Nordrehaug JE, Slettom G, Solvang SEH, Pedersen EKR, Midttun Ø, Ulvik A, Ueland PM, Nygard O, Giil LM. Plasma kynurenines and prognosis in patients with heart failure. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0227365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dschietzig TB, Kellner KH, Sasse K, Boschann F, Klüsener R, Ruppert J, Armbruster FP, Bankovic D, Meinitzer A, Mitrovic Vet al. Plasma kynurenine predicts severity and complications of heart failure and associates with established biochemical and clinical markers of disease. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2019;44:765–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zapolski T, Kamińska A, Kocki T, Wysokiński A, Urbanska EM. Aortic stiffness—is kynurenic acid a novel marker? Cross-sectional study in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0236413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sulo G, Vollset SE, Nygard O, Midttun O, Ueland PM, Eussen S, Pedersen ER, Tell GS. Neopterin and kynurenine-tryptophan ratio as predictors of coronary events in older adults, the Hordaland Health Study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:1435–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zuo H, Ueland PM, Ulvik A, Eussen S, Vollset SE, Nygård O, Midttun Ø, Theofylaktopoulou D, Meyer K, Tell GS. Plasma biomarkers of inflammation, the kynurenine pathway, and risks of all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular disease mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183:249–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yu E, Ruiz-Canela M, Guasch-Ferré M, Zheng Y, Toledo E, Clish CB, Salas-Salvadó J, Liang L, Wang DD, Corella Det al. Increases in plasma tryptophan are inversely associated with incident cardiovascular disease in the Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED) Study. J Nutr. 2017;147:314–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Esposito K, Marfella R, Ciotola M, di Palo C, Giugliano F, Giugliano G, D'Armiento M, D'Andrea F, Giugliano D. Effect of a Mediterranean-style diet on endothelial dysfunction and markers of vascular inflammation in the metabolic syndrome: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chrysohoou C, Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Das UN, Stefanadis C. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet attenuates inflammation and coagulation process in healthy adults: the ATTICA study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:152–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Casas R, Urpi-Sardà M, Sacanella E, Arranz S, Corella D, Castañer O, Lamuela-Raventós RM, Salas-Salvadó J, Lapetra J, Portillo MPet al. . Anti-inflammatory effects of the Mediterranean diet in the early and late stages of atheroma plaque development. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:3674390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yarla NS, Polito A, Peluso I. Effects of olive oil on TNF-α and IL-6 in humans: implication in obesity and frailty. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2018;18:63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rodríguez-López P, Lozano-Sanchez J, Borrás-Linares I, Emanuelli T, Menéndez JA, Segura-Carretero A. Structure-biological activity relationships of extra-virgin olive oil phenolic compounds: health properties and bioavailability. Antioxidants. 2020;9:685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Serreli G, Deiana M. Extra virgin olive oil polyphenols: modulation of cellular pathways related to oxidant species and inflammation in aging. Cells. 2020;9:478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yu E, Papandreou C, Ruiz-Canela M, Guasch-Ferre M, Clish CB, Dennis C, Liang L, Corella D, Fitó M, Razquin Cet al. Association of tryptophan metabolites with incident type 2 diabetes in the PREDIMED trial: a case–cohort study. Clin Chem. 2018;64:1211–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data described in the article, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending approval from the PREDIMED Steering Committee and Institutional Review Boards.