Abstract

Context

The identification and biological actions of pituitary-derived exosomes remain elusive.

Objective

This work aimed to validate production of exosomes derived from human and rat pituitary and elucidate their actions.

Methods

Isolated extracellular vesicles (EVs) were analyzed by Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) and expressed exosomal markers detected by Western blot, using nonpituitary fibroblast FR and myoblast H9C2 cells as controls. Exosome inhibitor GW4869 was employed to detect attenuated EV release. Exosomal RNA contents were characterized by RNA sequencing. In vitro and in vivo hepatocyte signaling alterations responding to GH1-derived exosomes (GH1-exo) were delineated by mRNA sequencing. GH1-exo actions on protein synthesis, cAMP (3′,5′-cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate) response, cell motility, and metastases were assessed.

Results

NTA, exosomal marker detection, and GW4869 attenuated EV release, confirming the exosomal identity of pituitary EVs. Hydrocortisone increased exosome secretion in GH1 and GH3 cells, suggesting a stress-associated response. Exosomal RNA contents showed profiles distinct for pituitary cells, and rat primary hepatocytes exposed to GH1-exo exhibited transcriptomic alterations distinct from those elicited by growth hormone or prolactin. Intravenous GH1-exo injection into rats attenuated hepatic Eif2ak2 and Atf4 mRNA expression, both involved in cAMP responses and amino acid biosynthesis. GH1-exo suppressed protein synthesis and forskolin-induced cAMP levels in hepatocytes. GH1-exo–treated HCT116 cells showed dysregulated p53 and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways and attenuated motility of malignant HCT116 cells, and decreased tumor metastases in nude mice harboring splenic HCT116 implants.

Conclusion

Our findings elucidate biological actions of somatotroph-derived exosomes and implicate exosomes as nonhormonal pituitary-derived messengers.

Keywords: exosome, pituitary somatotroph adenoma, nonhormonal actions

Pituitary tumors arise from highly differentiated anterior pituitary cells, and may hypersecrete hormones including growth hormone (GH), prolactin (PRL), adrenocorticotropin, and rarely follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, or thyrotropin, or may be nonfunctional (1). These hormones act as messenger molecules to distant organs to regulate physiology and/or behavior (2). In patients with acromegaly, a pituitary somatotroph adenoma hypersecretes GH, which drives hepatic overproduction of insulin-like growth factor 1 and leads to development of metabolic and cardiovascular sequelae (3). Over the past decade, numerous studies indicate extracellular vesicles (EVs) act as paracrine/endocrine effectors, suggesting an alternative mode of intercellular communication beyond hormones (4).

Exosomes are small EVs (30-150 nm) of endocytic origin that contain lipids, proteins, messenger RNA (mRNA), and noncoding RNA (5, 6). Exosomal contents released into adjacent or distant target cells may facilitate local and systemic intercellular communication (7, 8). For example, exosomal shuttle mRNA and microRNA remain functionally active, and are delivered to target recipient cells to regulate specific sets of mRNA and protein expression (9, 10). Exosomes may also mediate interspecies rodent and human intercellular communication in experimental models (9).

As few reports have focused on characterizing pituitary EVs (11, 12), we considered whether such EVs may include exosomes that could act as pituitary messengers alongside pituitary trophic hormones functioning at target sites. Given the lack of cell lines derived from human somatotroph tumors and from normal human and rodent pituitaries, we employed primary cells derived from human somatotroph adenomas, GH1 and GH3 rat somatotroph tumor cells (13), and primary rat pituitary cells to isolate small pituitary EVs, which, by various lines of evidence, appear to be exosomes. We also profiled RNA derived from small EVs secreted by pituitary GH1 and GH3 cells and from nonpituitary fibroblast FR cells and myoblast H9C2 cells known to release exosomes. We tested GH1-derived exosome (GH1-exo) actions in hepatocyte signaling pathways in vitro and in vivo, as well as on protein synthesis, cAMP (3′,5′-cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate) response, cell motility and metastases. Our findings suggest that pituitary exosomes may act as nonhormonal pituitary-derived messengers mediating intercellular communication.

Materials and Methods

Cell Cultures

Human GH-secreting adenoma was freshly obtained from a 35-year-old male patient with acromegaly at the time of surgical resection after informed consent, as approved by the Cedars-Sinai Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 2873). Normal rat pituitaries were dissected from 6 male and 5 female Wistar rats (Charles River) as approved by the Cedars-Sinai Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC No. 002602). Rat and human pituitary tissues were transferred into 0.3% bovine serum albumin–containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM). After washing, all tissue pieces were put on a prewetted 70-µm cell strainer (Falcon) held by a 50-mL conical centrifuge tube. Tumor tissues were gently smashed on the cell strainer, flushed with DMEM, and centrifuged at 350g for 5 minutes to collect primary cells. Cell pellets were resuspended in eBioscience RBC Lysis Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 3 minutes to lyse red blood cells and eliminate red blood cell–derived exosome contamination in subsequent experiments. Resultant primary pituitary cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and cultured in NeuroCult NS-A Basal Medium with proliferation supplement (StemCell Technologies).

Cryopreserved Wistar rat hepatocytes were purchased from Sekisui XenoTech (catalog No. R3000.H15+, Lot 1610030) and thawed with OptiThaw Hepatocyte Kit (catalog No. K8000). Live cells were stained with trypan blue, counted by cell counter (Bio-Rad model TC10), and plated in OptiPlate Hepatocyte Media (catalog No. K8200). Pituitary GH1 (CCL-82, RRID:CVCL_0610, https://web.expasy.org/cellosaurus/CVCL_0610) and GH3 (CCL-82.1, RRID:CVCL_0273, https://web.expasy.org/cellosaurus/CVCL_0273), fibroblast FR (CRL-1213, RRID:CVCL_4202, https://web.expasy.org/cellosaurus/CVCL_4202), myoblast H9C2 (CRL-1446, RRID:CVCL_0286, https://web.expasy.org/cellosaurus/CVCL_0286), and malignant colon HCT116 (CCL-247, RRID:CVCL_0291, https://web.expasy.org/cellosaurus/CVCL_0291) and SW480 (CCL-228, RRID:CVCL_0546, https://web.expasy.org/cellosaurus/CVCL_0546) cell lines were purchased from ATCC. Exosome inhibitor GW4869 (catalog No. 567715) and hydrocortisone (catalog No. H6909) were obtained from MilliporeSigma.

Small Extracellular Vesicle Separation and Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis

Cells were plated in serum-free medium for 72 hours. Supernatant was collected, centrifuged at 350g for 5 minutes then at 2000g for 10 minutes to remove debris, and prefiltered through a 0.22-µm filter to eliminate larger vesicles. To efficiently concentrate exosomes from large medium volumes, we employed ultrafiltration. Centricon Plus 70 mL and Amicon Ultra 15 mL centrifugal filters (MilliporeSigma) were used for subsequent ultrafiltration to concentrate EV particles. Because the GH molecule (molecular weight < 30 kDa and size < 15 nm) is smaller than exosomes, we chose centrifugal filters with a 100-kDa membrane to ultra-filter GH1 exosomes, and 10-kDa filters were used for nonpituitary EVs. Ultrafiltered EVs were further washed in PBS (1:50) by ultracentrifugation at 28 000g for 4 hours to eliminate GH contamination for functional studies. EVs were resuspended in PBS, aliquoted to avoid freeze-thaw cycles, and stored in ultralow adhesion Eppendorf tubes at –70 °C. EV size and number were assessed by Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA 3.2 Dev Build 3.2.16) with NanoSight NS300 (Malvern Panalytical). EVs were not detected in cell-free NeuroCult NS-A Basal Medium (Human) and NeuroCult Basal Medium (Mouse and Rat) with proliferation supplement (StemCell Technologies) used for primary pituitary culture, or in OptiThaw and OptiPlate media (Sekisui XenoTech) used for primary hepatocyte culture.

Extracellular Vesicle Protein Extraction and Western Blot

EV proteins were prepared by Total Exosome RNA & Protein Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and exosomal markers detected by Western blot (14). Antibodies used were Alix (3A9) Mouse mAb, dilution 1:500 (Cell Signaling Technology, No. 2171, RRID:AB_2299455, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_2299455); Anti-tsg 101 Antibody (C-2), dilution 1:100 (Santa Cruz, No. sc-7964, RRID:AB_671392, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_671392); HSP70 Antibody, dilution 1:500 (Cell Signaling Technology, No. 4872, RRID:AB_2279841, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_2279841); HSP90 Antibody, dilution 1:500 (Cell Signaling Technology, No. 4875, RRID:AB_2233331, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_2233331); Anti-CD63 Antibody, dilution 1:1000 (System Biosciences, EXOAB-CD63A-1, RRID:AB_2561274, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_2561274).

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay

Rat GH concentration in culture medium and in isolated EV aliquots was assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Millipore Sigma, catalog No. EZRMGH-45K, RRID:AB_2892711, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_2892711).

microRNA/RNA Extraction

Cellular microRNA was prepared by miRNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) and EV RNA isolated by Total Exosome RNA & Protein Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to assess microRNA expression in cells and corresponding exosomes. Up to 500-ng cellular microRNA and EV RNA were reverse-transcribed by miScript II RT Kit (QIAGEN). Total RNA was prepared by RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) and 1-µg RNA was used to synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA) with iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad) for quantitative real-time–polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). For mRNA sequencing, total RNA was extracted by RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Total RNA sample concentration was measured using a Qubit fluorometer (high-sensitivity assay kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and for quality using the 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). For exosomal RNA sequencing, serum-free medium of GH1, GH3, H9C2, and FR cells were collected. EV preparation and libraries generation were performed by System Biosciences.

microRNA and Messenger RNA Expression Assessment by Quantitative Real-time–Polymerase Chain Reaction

microRNA expression was assessed by qRT-PCR using a miScript SYBR Green PCR Kit (QIAGEN). miScript primers were purchased from QIAGEN: miR-7a-2-3p (catalog No. MS00028553), miR-129-5p (catalog No. MS00005614), miR-141-3p (catalog No. MS00000413), miR-183-5p (catalog No. MS00000490), miR-200a-3p (catalog No. MS00000581), miR-200b-5p (catalog No. MS00027041), miR-204-5p (catalog No. MS00000609), miR-301b-3p (catalog No. MS00013356), miR-340-5p (catalog No. MS00043421), miR-375-3p (catalog No. MS00033516), miR-497-5p (catalog No. MS00001162), miR-125b-1-3p (catalog No. MS00013006), miR-322-3p (catalog No. MS00013440). Cel-miR-39-3p (catalog No. MS00019789) was used as spike-in control, and U6 (catalog No. MS00033740) as internal control for cellular microRNA expression.

mRNA expression was measured by qRT-PCR, amplified in 20-μL reaction mixtures (100-ng template, 0.5-μM primer, 10-μL 2X SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix [Bio-Rad]) at 95 °C for 1 minute, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 20 seconds and 60 °C for 40 seconds. Primers were purchased from Bio-Rad: Atf4 (No. qRnoCED0002372), Eif2ak2 (No. qRnoCID0007932). Gapdh (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; No. qRnoCID0057018) was used as an internal control.

Distribution of GH1-derived Exosomes In Vivo

GH1-derived exosomes suspended in PBS were treated with Vybrant DiD Cell-Labeling Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Labeled GH1-exo (5 × 108 particles/mouse) were intravenously injected into female C57BL/6 mice (n = 4), and unlabeled exosomes used as control (n = 1). Two mice injected with DiD-labeled GH1-exo and 1 control mouse were euthanized for organ dissection after 20 hours, as were 2 mice injected with DiD-labeled GH1-exo for 4 hours. Images were taken by using IVIS Spectrum imaging systems (Perkin Elmer).

RNA Sequencing and Data Analysis

For exosomal RNA sequencing, exosome preparation, exosomal RNA library generation, and sequencing services were purchased from System Biosciences. For mRNA sequencing, RNA integrity measurement, mRNA library preparation, and sequencing were all conducted at the Cedars-Sinai Genomics Core. Up to 1-µg total RNA per sample was used for library construction by the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA library preparation kit (Illumina). Library concentration was measured with a Qubit fluorometer and library size on an Agilent 4200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies). Libraries were multiplexed and sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina) using 75-bp single-end sequencing. On average, approximately 30 million reads were generated from each sample. Sequencing samples were replicated and samples from the same experiment were sequenced in the same run.

Raw reads obtained from RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) were aligned to the transcriptome using STAR (v 2.5.0) (15)/RSEM (v 1.2.25) (16) with default parameters. For human samples, a custom human GRCh38 transcriptome reference was downloaded (http://www.gencodegenes.org) containing all protein coding and long noncoding RNA genes based on human GENCODE version 23 annotation. For rat samples, a custom rat transcriptome reference was downloaded from Ensembl (https://uswest.ensembl.org/Rattus_norvegicus/Info/Index),containing all protein coding and long noncoding RNA genes based on rat Ensembl version 6.0.83 annotation. Expression counts for each gene (TPM: transcripts per million) in all samples were normalized by sequencing depth. Protein coding genes with at least 2 TPM on average in either condition were used to perform the differential gene expression analysis using DESeq2 (17). P values of multiple tests were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method (18) and the significance level was designated as false discovery rate less than .05 for rat group comparison. To capture the similar number of differentially expressed (DE) genes, we used the top 300 DE genes from the human group comparison, sorted by false discovery rate values, to conduct the downstream analysis. Pathway enrichment analysis of DE genes was performed using DAVID (19).

Protein Synthesis Assay

Rat hepatocytes (7.5 × 104 cells/well, 8 wells/group) were seeded in 96-well plates (Costar catalog No. 3915) precoated by ECL (Millipore Sigma) and cultured in OptiPlate Hepatocyte Media for 24 hours. Media were replaced and cells incubated with GH1-exo (2 × 104 particles/cell) or vehicle (PBS) respectively for an additional 24 hours. Nascent protein synthesis was detected by Click-iT HPG Alexa Fluor 488 Protein Synthesis Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Fluorescence with Alexa Fluor 488 was read to detect newly synthesized proteins, and nuclear DAPI (diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining measured to adjust for cell number.

3′,5′-Cyclic Adenosine 5′-Monophosphate Assay

Rat hepatocytes were plated in 48-well plates (7 × 104 cells/well) for 24 hours. Medium was replaced, and cells incubated with forskolin (0-100 µM), GH1-exo (105, 106, 107, 108, and 109 particles/mL) plus forskolin (10 µM), or GH (0-1000 ng/mL) plus forskolin (10 µM) for 30 minutes, then harvested to measure cAMP. Intracellular cAMP was assayed in quadruplicate using the LANCE cAMP kit (PerkinElmer) and modified for intracellular cAMP (20). Extrapolated results were read by a Victor 3 1420_015 spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer).

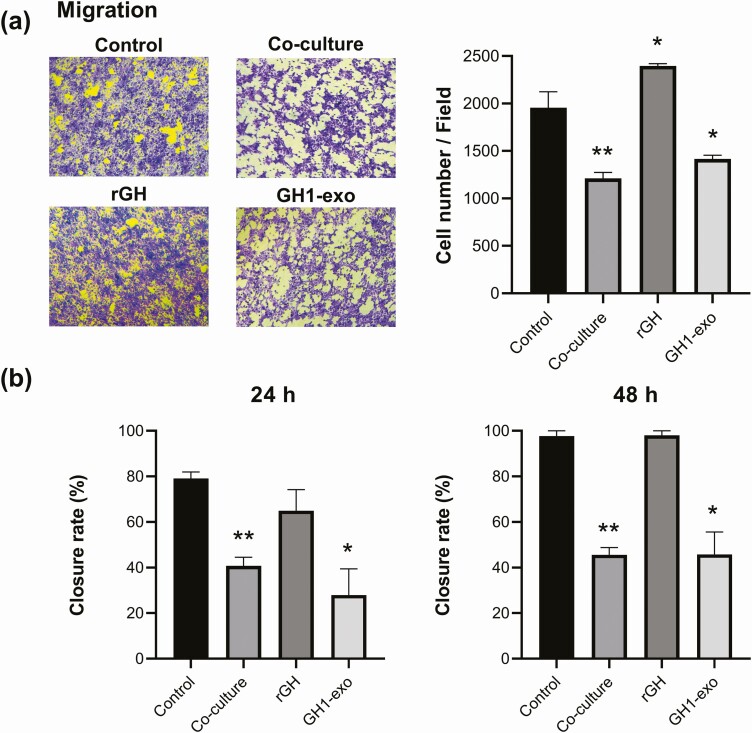

Invasion and Migration

Inserts (8-µm pore size; Corning, catalog No. 354578 for migration and catalog No. 354483 for invasion) were placed in 24-well plates and with prewarmed culture medium for 2 hours at 37 °C. HCT116 cells were added to the inserts (5 × 105 cells/insert for migration and 3 × 105 cells/insert for invasion) and were also seeded at the bottom of each well at approximately 50% confluency. HCT116 cells were incubated with recombinant rat GH (rGH) (500 ng/mL), or GH1-exo (109 particles in 1 mL/well), or PBS as control. Coculture conditions were established by seeding GH1 cells instead of HCT116 cells at the well bottoms at approximately 50% confluency. Both GH1 and HCT116 cells were cultured in DMEM/F-12 medium containing 5% exosome-depleted fetal bovine serum (EDFBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to maintain identical culture conditions for all groups. After 24 hours, the insert membranes were fixed with 70% ethanol and stained with 0.05% crystal violet. Nonmigrated and noninvaded cells on membrane surfaces were gently removed with a cotton swab, inserts imaged, and invaded and migrated cells quantified in 4 random fields per insert by blinded observers.

Wound-Healing Assay

HCT116 cells were seeded at approximately 50% confluency in 24-well plates in McCoy’s 5A medium with 10% FBS overnight. The next day, when cells were firmly attached, medium was aspirated and HCT116 cells scraped. Cells were washed in PBS, cultured in DMEM/F-12 with 5% EDFBS, and images of starting points photographed. HCT116 cells were then treated with PBS, rGH (500 ng/mL), or GH1-exo (109 particles in 1 mL/well). HCT116 cells (3 × 105 cells/insert) seeded in 0.4-µm pore size Transwell inserts (Costar catalog No. 3413) were placed on top of each well. Coculture conditions were established with 3 × 105 GH1 cells seeded in the insert instead of HCT116 cells. Medium was replaced and images taken every 24 hours for up to 48 hours. Wound healing was quantified by measuring the percentage of area closure at 24 and 48 hours.

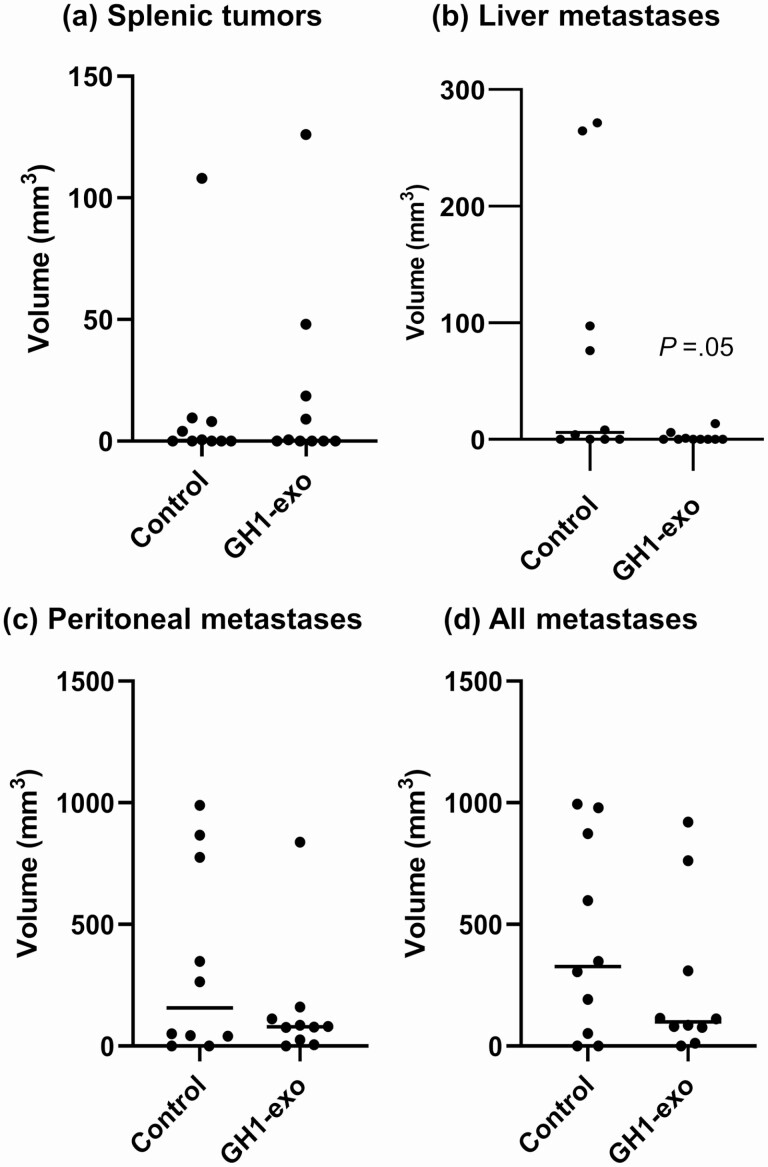

Experimental Metastases In Vivo

Animal protocols were approved by the Cedars-Sinai Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC No. 008537). Twenty 6-week-old female nude mice were randomly separated into 2 groups. HCT116 cells (5 × 105 cells) suspended in 50-µL PBS or in 50-µL PBS containing 1010 GH1-exo particles were implanted into the spleen of nude mice (n = 10 per group). Mice were intravenously administered GH1-exo (1010 particles/mouse) or vehicle twice a week for 5 weeks, weighed twice weekly, and monitored for metastasis development. Five weeks later, all mice were euthanized after slightly decreased body weight was observed. Organs, including liver and spleen, were inspected for tumor metastases. Where present, tumors were harvested, metastatic loci counted, and tumor size measured.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc). Comparisons were analyzed by unpaired 2-tailed t test. Multiple-comparisons were analyzed by unpaired 2-tailed t test with Bonferroni correction or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P less than or equal to .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Identification of Pituitary Adenoma Cell-derived Small Extracellular Vesicles as Exosomes

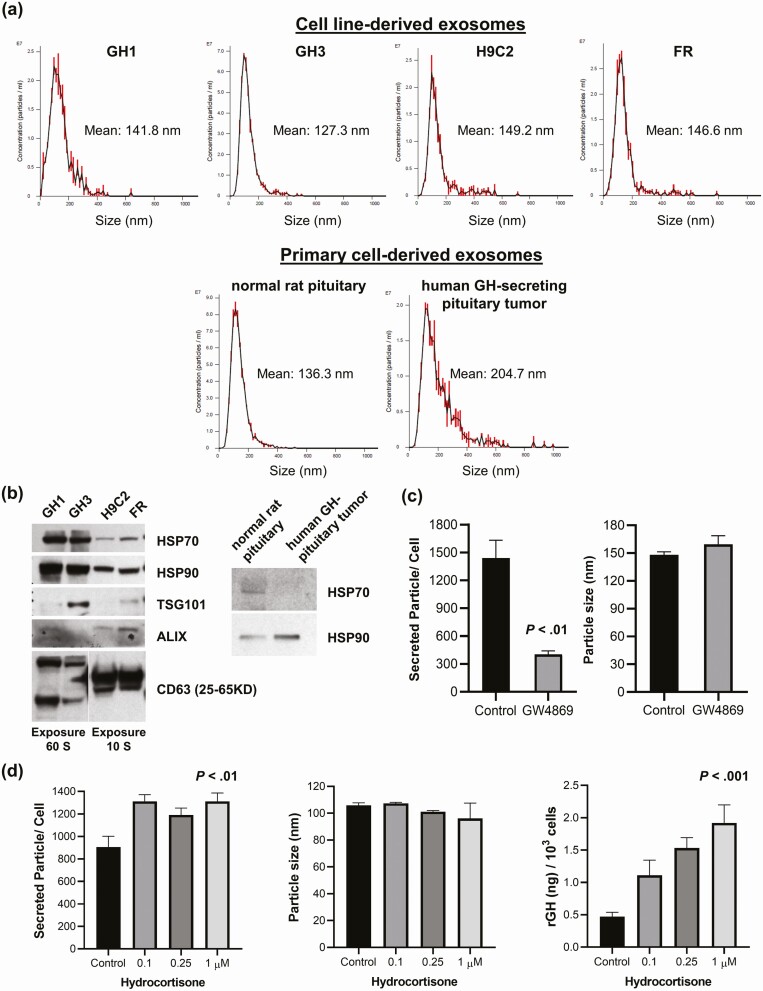

We employed primary cells derived from human somatotroph adenoma, rat somatotroph tumor cell lines (GH1 and GH3), and primary rat pituitary cells to characterize pituitary EVs. Rat fibroblast FR and myoblast H9C2 cells, known to release exosomes, were used as nonpituitary controls. Small EVs derived from primary human somatotroph adenoma cells, GH1, GH3, and primary rat pituitary cells were analyzed by NTA to visualize, measure, and count particles. Tracking patterns were similar to those of FR and H9C2 control cells; particle sizes ranged from 30 to 200 nm, with a mean of approximately 120 to 140 nm (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Isolation of pituitary-adenoma-cell–derived exosomes and regulation of exosome production. A, Representative Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis of cell-line–derived (upper) and primary-cell–derived (lower) exosomes. B, Exosome markers detected by Western blot in cell lines (left) and primary cells (right). C, GW4869 attenuated GH1-exo release (left) (P < .01, t test), while exosome size was not affected (right). D, Hydrocortisone induced exosome release (left) (P < .01) but did not affect exosome size (middle), and dose-dependently increased growth hormone (GH) production as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (right) (P < .001) (one-way ANOVA). All experiments were repeated 3 times and representative results presented. For C and D, quantitative results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4).

Proteins extracted from GH1, GH3, FR, and H9C2 cell-secreted small EVs expressed exosome markers ALIX, TSG101, CD63, HSP70, and HSP90 as detected by Western blot (Fig. 1B). HSP70 and HSP90 were also detected in EV protein harvested from primary human somatotroph adenoma cells and primary rat pituitary cells; however, ALIX, TSG101, and CD63 were not detectable, likely because of limited cell numbers obtained from primary cultures and the consequent limited yield of EV isolation.

To examine whether EV generation could be suppressed, we treated GH1 and GH3 cells in serum-free medium with exosome biosynthesis inhibitor GW4869 (10 µM) for 30 hours. EVs isolated from culture medium were assessed by NTA, and EV concentration was normalized to cell number. GW4869 attenuated GH1-secreted EV release as compared to controls (72% reduction, P < .01, t test), while EV size was not affected (Fig. 1C). Similar results were obtained with GH3 cells (data not shown). The inhibitory effects of GW4869 provide further evidence of the exosomal identity of small pituitary EVs.

Taken together, these observations provide several lines of evidence that small pituitary EVs are exosomes, although we cannot exclude some contribution by nonexosome EVs (eg, microvesicles, apoptosomes).

Hydrocortisone Increases Pituitary Exosome Production

Stress induces adrenal steroids, which also induce somatotroph GH (21). As stress induces exosome release (22-27), we tested whether steroids influence pituitary exosome production. We treated GH1 and GH3 cells with hydrocortisone (up to 1 µM) for 72 hours in serum-free medium and then isolated supernatant exosomes. Cells were harvested and counted to normalize exosome concentration. Hydrocortisone dose-dependently increased GH production as measured by ELISA (P < .001, one-way ANOVA), and also induced exosome release by up to 45% (P < .01, one-way ANOVA), but did not affect GH1 exosome size (Fig. 1D). Treatment of GH3 cells showed similar results (not shown).

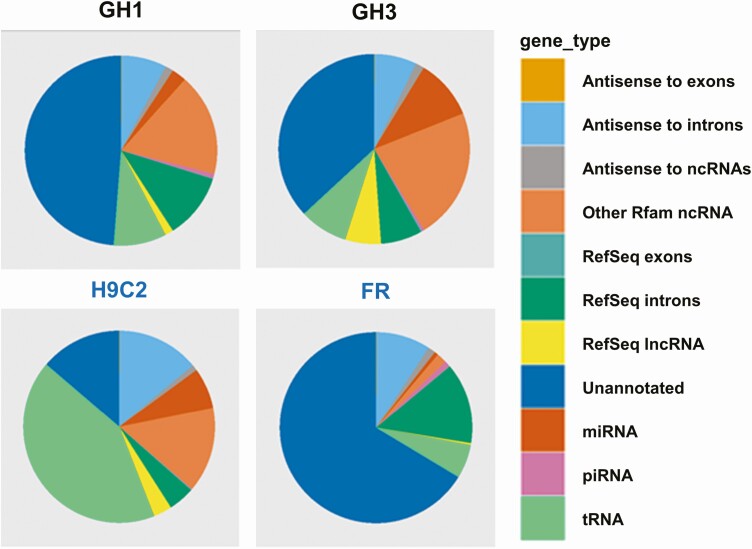

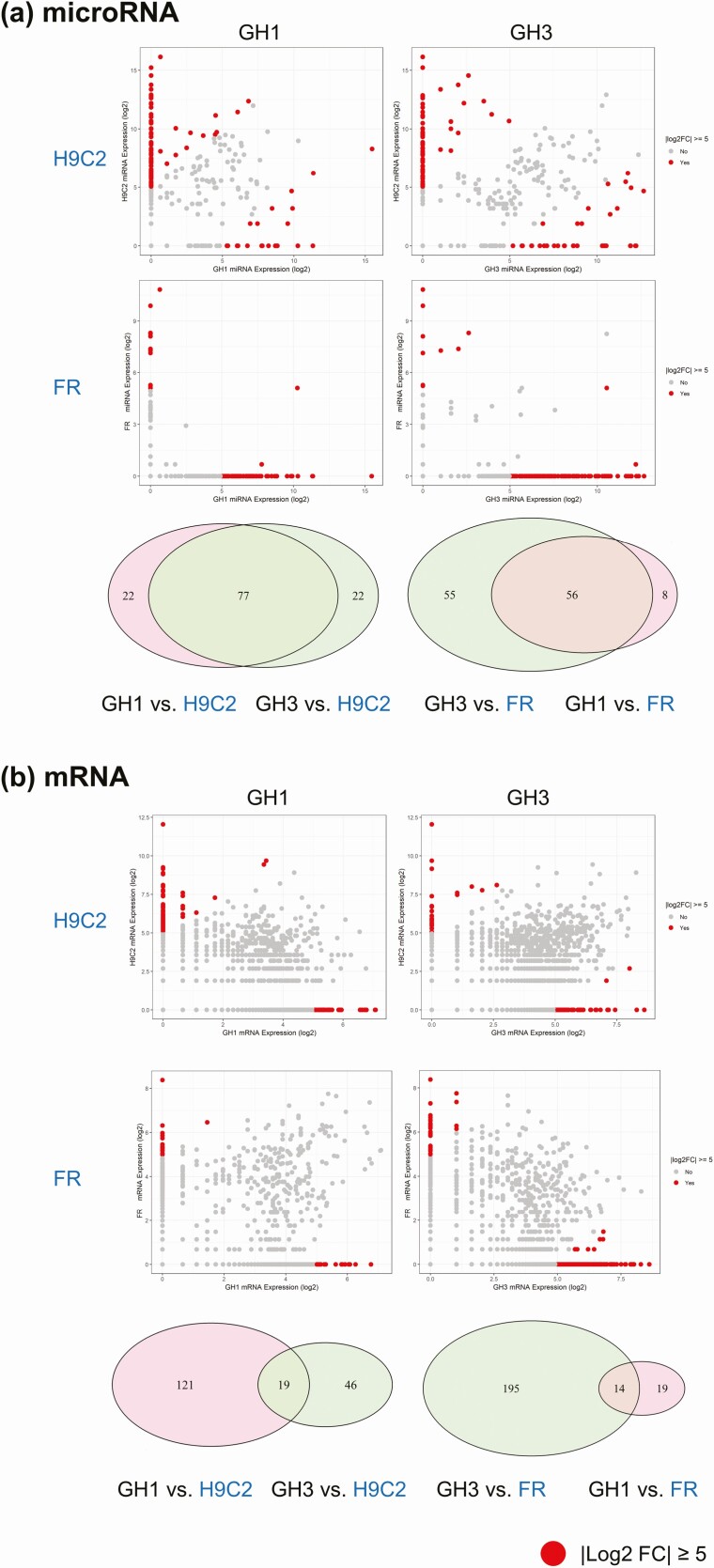

RNA Sequencing of Exosomal Shuttle RNA Derived From Rat Somatotroph Tumor Cells

Exosomal shuttle RNA derived from rat somatotroph GH1 and GH3 tumor cells were profiled by exosomal RNA-seq. Exosomal RNA-seq of somatotroph tumor cells showed distinct profiles as compared with those derived from fibroblast FR and myoblast H9C2 cells (Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 3, exosomal microRNA and mRNA derived from each cell line were analyzed using pairwise comparison. Ninety-nine exosomal microRNAs were distinctively expressed in GH1 and GH3 cells as compared with H9C2 cells, and 77 microRNAs overlapped (log2-fold change [|log2FC|] ≥ 5). In addition, as compared with those derived from FR cells, 111 exosomal microRNAs were distinctively expressed in GH3 cells and 64 distinctively expressed in GH1 cells, and 56 microRNAs overlapped (|log2FC|≥ 5). Overlapping altered microRNAs in GH1 and GH3 vs FR and H9C2 exosomes are shown in Table 1. Exosomal mRNA expression exhibited cell specific patterns for pituitary cells (GH1 and GH3) vs nonpituitary cells (FR and H9C2) similarly to microRNA (see Fig. 3), and overlapping mRNAs shown in Table 2. Since differentiated mRNA expression differs markedly in pituitary and nonpituitary cells, the number of overlapping exosome mRNAs is lower than that of microRNAs.

Figure 2.

Exosomal RNA profiles of GH1, GH3, H9C2, and FR as measured by RNA sequencing (RNASeq). Shown are sequencing read mapping and annotation of exosomal RNA derived from rat somatotroph GH1 and GH3 tumor cell lines and from nonpituitary FR and H9C2 cells.

Figure 3.

Pairwise comparison of exosomal microRNA or messenger RNA (mRNA) derived from GH1, GH3, H9C2, and FR cells. Shown are calculated log2FC for A, exosomal microRNA, and B, exosomal mRNA, expression in GH1 and GH3 vs H9C2 and FR. Red dots show alteration with |log2FC|≥ 5. Illustrations summarize GH1 and GH3 exosomal microRNA and mRNA expression overlap vs FR and H9C2.

Table 1.

Overlapping microRNAs altered in GH1 and GH3 vs FR and H9C2 exosomes

| microRNA | GH1 vs FR | GH3 vs FR | microRNA | GH1 vs H9C2 | GH3 vs H9C2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | rno-let-7f-1-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 1 | rno-miR-130b-5p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 2 | rno-miR-129-1-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 2 | rno-miR-137-3p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 3 | rno-miR-129-2-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 3 | rno-miR-137-5p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 4 | rno-miR-129-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 4 | rno-miR-141-3p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 5 | rno-miR-130b-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 5 | rno-miR-153-3p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 6 | rno-miR-137-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 6 | rno-miR-183-3p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 7 | rno-miR-137-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 7 | rno-miR-200a-5p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 8 | rno-miR-139-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 8 | rno-miR-200b-5p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 9 | rno-miR-141-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 9 | rno-miR-301b-3p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 10 | rno-miR-153-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 10 | rno-miR-340-5p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 11 | rno-miR-181c-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 11 | rno-miR-344a-3p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 12 | rno-miR-183-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 12 | rno-miR-344b-1-3p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 13 | rno-miR-183-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 13 | rno-miR-344b-3p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 14 | rno-miR-187-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 14 | rno-miR-346 | ↑ | ↑ |

| 15 | rno-miR-193b-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 15 | rno-miR-541-5p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 16 | rno-miR-195-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 16 | rno-miR-708-3p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 17 | rno-miR-195-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 17 | rno-miR-7a-2-3p | ↑ | ↑ |

| 18 | rno-miR-200a-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 18 | rno-let-7c-1-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 19 | rno-miR-200b-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 19 | rno-miR-100-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 20 | rno-miR-204-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 20 | rno-miR-10b-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 21 | rno-miR-204-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 21 | rno-miR-125b-1-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 22 | rno-miR-205 | ↑ | ↑ | 22 | rno-miR-133b-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 23 | rno-miR-219a-1-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 23 | rno-miR-143-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 24 | rno-miR-29b-1-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 24 | rno-miR-145-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 25 | rno-miR-29b-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 25 | rno-miR-17-1-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 26 | rno-miR-301b-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 26 | rno-miR-18a-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 27 | rno-miR-325-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 27 | rno-miR-18a-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 28 | rno-miR-339-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 28 | rno-miR-196b-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 29 | rno-miR-340-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 29 | rno-miR-19a-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 30 | rno-miR-344a-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 30 | rno-miR-214-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 31 | rno-miR-344b-1-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 31 | rno-miR-222-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 32 | rno-miR-344b-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 32 | rno-miR-31a-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 33 | rno-miR-345-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 33 | rno-miR-322-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 34 | rno-miR-346 | ↑ | ↑ | 34 | rno-miR-34b-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 35 | rno-miR-378a-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 35 | rno-miR-34b-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 36 | rno-miR-384-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 36 | rno-miR-34c-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 37 | rno-miR-485-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 37 | rno-miR-351-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 38 | rno-miR-497-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 38 | rno-miR-351-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 39 | rno-miR-500-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 39 | rno-miR-3580-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 40 | rno-miR-541-5p | ↑ | ↑ | 40 | rno-miR-3580-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 41 | rno-miR-6319 | ↑ | ↑ | 41 | rno-miR-449c-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 42 | rno-miR-664-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 42 | rno-miR-450a-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 43 | rno-miR-672-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 43 | rno-miR-450a-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 44 | rno-miR-708-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 44 | rno-miR-450b-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 45 | rno-miR-7a-1-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 45 | rno-miR-450b-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 46 | rno-miR-7a-2-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 46 | rno-miR-463-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 47 | rno-miR-9a-3p | ↑ | ↑ | 47 | rno-miR-463-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 48 | rno-miR-125b-1-3p | ↓ | ↓ | 48 | rno-miR-465-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 49 | rno-miR-145-3p | ↓ | ↓ | 49 | rno-miR-465-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 50 | rno-miR-322-3p | ↓ | ↓ | 50 | rno-miR-471-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 51 | rno-miR-351-5p | ↓ | ↓ | 51 | rno-miR-471-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 52 | rno-miR-450b-3p | ↓ | ↓ | 52 | rno-miR-483-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 53 | rno-miR-503-3p | ↓ | ↓ | 53 | rno-miR-483-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 54 | rno-miR-503-5p | ↓ | ↓ | 54 | rno-miR-490-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 55 | rno-miR-542-3p | ↓ | ↓ | 55 | rno-miR-490-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 56 | rno-miR-676 | ↓ | ↓ | 56 | rno-miR-503-3p | ↓ | ↓ |

| 57 | rno-miR-503-5p | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 58 | rno-miR-505-3p | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 59 | rno-miR-505-5p | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 60 | rno-miR-542-3p | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 61 | rno-miR-542-5p | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 62 | rno-miR-592 | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 63 | rno-miR-6321 | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 64 | rno-miR-6324 | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 65 | rno-miR-6328 | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 66 | rno-miR-675-3p | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 67 | rno-miR-675-5p | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 68 | rno-miR-676 | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 69 | rno-miR-741-3p | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 70 | rno-miR-743a-5p | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 71 | rno-miR-743b-3p | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 72 | rno-miR-743b-5p | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 73 | rno-miR-871-3p | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 74 | rno-miR-871-5p | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 75 | rno-miR-878 | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 76 | rno-miR-881-5p | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 77 | rno-miR-99a-5p | ↓ | ↓ |

Increase (↑) and decrease (↓): |log2FC|≥ 5. Exosomal microRNAs altered both in GH1 and GH3 vs FR and H9C2 are shown in bold.

Abbreviation: FC, fold change.

Table 2.

Overlapping messenger RNAs altered in GH1 and GH3 vs FR and H9C2 exosomes

| mRNA | GH1 vs FR | GH3 vs FR | mRNA | GH1 vs H9C2 | GH3 vs H9C2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adra1d | ↑ | ↑ | 1 | Neurod4 | ↑ | ↑ |

| 2 | Cactin | ↑ | ↑ | 2 | Car3 | ↓ | ↓ |

| 3 | Hist2h3c2 | ↑ | ↑ | 3 | Ctgf | ↓ | ↓ |

| 4 | Mdh1 | ↑ | ↑ | 4 | Edn1 | ↓ | ↓ |

| 5 | Pgf | ↑ | ↑ | 5 | Epdr1 | ↓ | ↓ |

| 6 | Rasl11a | ↑ | ↑ | 6 | Fzd2 | ↓ | ↓ |

| 7 | Sapcd2 | ↑ | ↑ | 7 | Gpx8 | ↓ | ↓ |

| 8 | Ctgf | ↓ | ↓ | 8 | Itpripl2 | ↓ | ↓ |

| 9 | Idi2 | ↓ | ↓ | 9 | Myl9 | ↓ | ↓ |

| 10 | Olr1765 | ↓ | ↓ | 10 | Myog | ↓ | ↓ |

| 11 | Olr610 | ↓ | ↓ | 11 | Prkcdbp | ↓ | ↓ |

| 12 | Olr611 | ↓ | ↓ | 12 | S100a11 | ↓ | ↓ |

| 13 | Pde6h | ↓ | ↓ | 13 | S100a4 | ↓ | ↓ |

| 14 | Tmsb4x | ↓ | ↓ | 14 | S100a6 | ↓ | ↓ |

| 15 | Slc35e4 | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 16 | Sox11 | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 17 | Tmsb4x | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 18 | Tnnc2 | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| 19 | Vim | ↓ | ↓ |

Increase (↑) and decrease (↓): |log2FC| ≥ 5. Exosomal messenger RNAs (mRNAs) altered both in GH1 and GH3 vs FR and H9C2 are shown in bold.

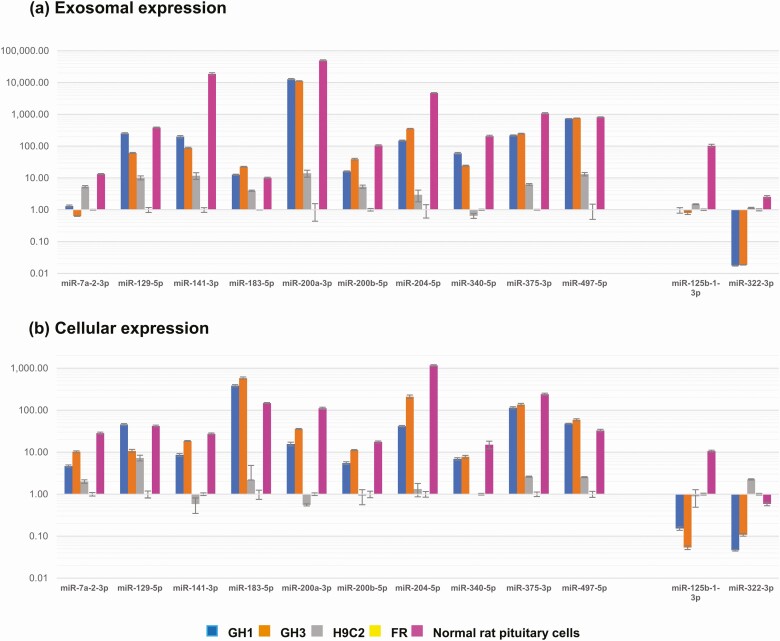

To further validate exosomal RNA-seq data, we selected 10 highly expressed and 2 lowly expressed microRNAs in GH1 and GH3 exosomes as compared with FR exosomes, and assessed expression levels in both exosomes and in corresponding parent cells by qRT-PCR. We also assessed these microRNA expression levels in normal rat primary pituitary cells and exosomes, normalized to FR expression. As shown in Fig. 4, most exosomal microRNA expression levels assessed by qRT-PCR were consistent with the results of RNA-seq. Most detected cellular and exosomal microRNA levels were concordant, indicating that microRNA signatures were similar in exosomes and in cells of origin.

Figure 4.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymorphism chain reaction validation of selected microRNA (miRNA) expression in exosomes and in corresponding parent cells. microRNA expression in A, exosomes, and B, parent cells, from GH1, GH3, and H9C2 cell lines and from normal rat primary pituitary cells were normalized to the expression of FR taken as 1.

GH1-derived Exosomes Regulate Hepatic Signaling Pathways In Vitro

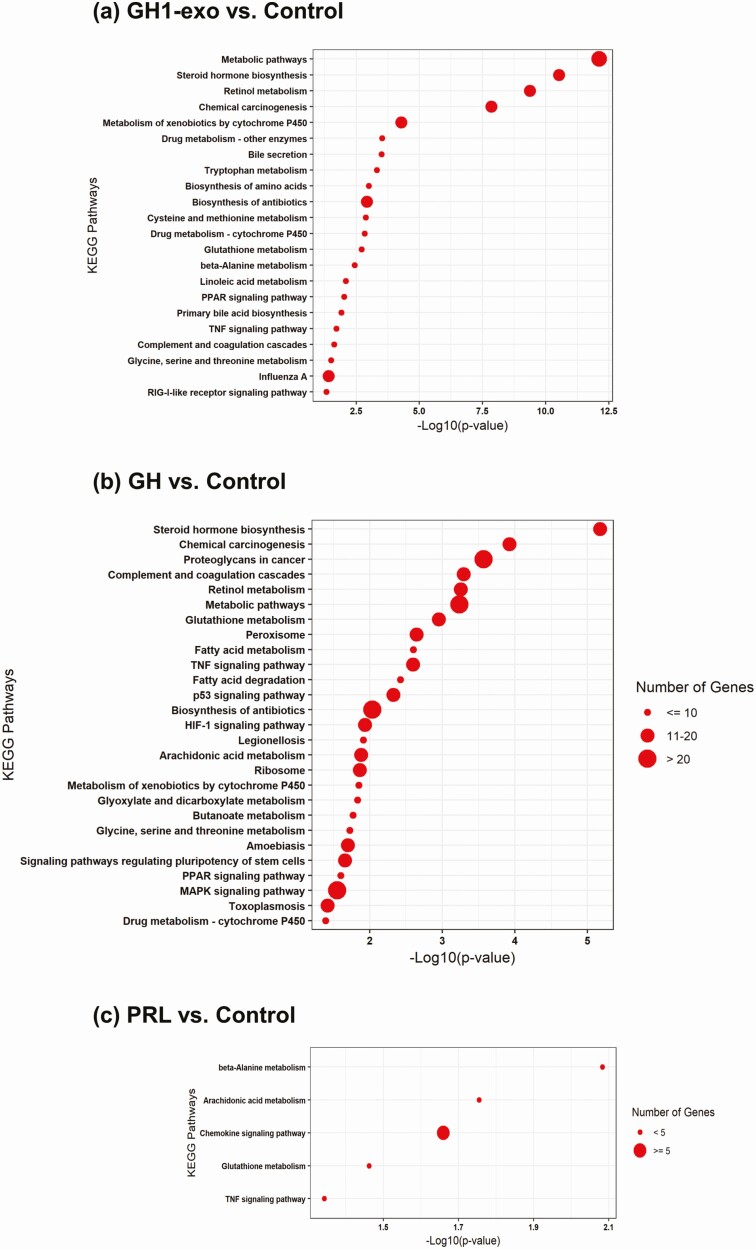

As functions of somatotroph tumor cell-derived exosomes are unknown, we treated primary rat hepatocytes with GH1-exo to explore downstream signaling alterations. GH1-exo were isolated by combining ultrafiltration and ultracentrifugation to eliminate GH contamination in the supernatant. Residual GH in isolated exosomes was assessed by ELISA to ensure less than 5-ng GH per treatment in functional assays. As hepatocytes are known target cells for pituitary-derived GH, we treated primary hepatocytes with GH1-exo (103 particles/cell), rGH (500 ng/mL), recombinant rat PRL (rPRL) (500 ng/mL), or PBS as control for 24 hours. mRNA sequencing identified downstream genes altered by GH1-exo, rGH, and rPRL as compared with nontreated controls, respectively, which were further delineated by KEGG pathway analysis. As shown in Fig. 5, GH1-exo behaved distinctly from GH and PRL. Specifically, although PRL altered a few hepatocyte pathways, GH1-exo and rGH both exhibited extensive but distinctive signaling patterns.

Figure 5.

Signaling pathways regulated by GH1-derived exosomes, growth hormone (GH), and prolactin (PRL) in primary rat hepatocytes. Signaling pathways delineated by KEGG pathway analysis in A, GH1-derived exosomes (GH1-exo); B, GH; and C, PRL vs control, based on altered genes identified in messenger RNA sequencing (mRNA-seq). Significantly altered pathways are listed from top to bottom according to P value. Size of red dots indicates the number of altered genes in each corresponding pathway. For mRNA-seq, each sample was assessed in duplicate, and experiments were repeated twice.

GH1-derived Exosomes Distinctively Regulate Hepatic Signaling Pathways In Vivo Compared to FR-derived Exosomes

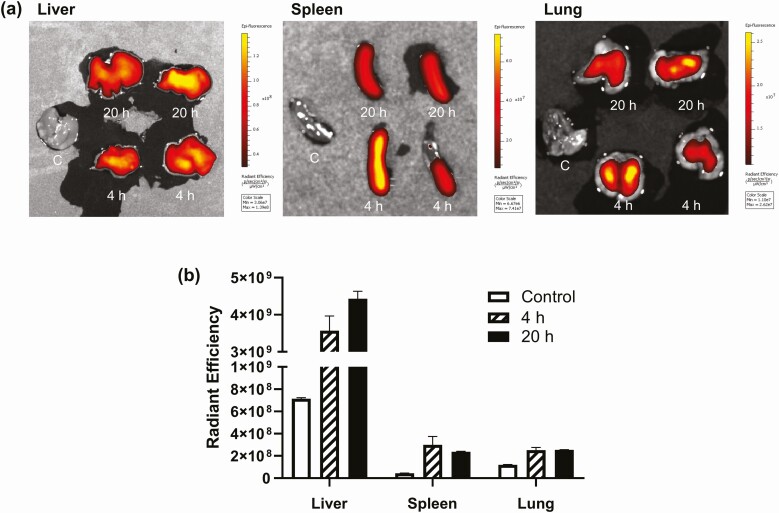

As GH1-exo altered signaling pathways in primary rat hepatocytes in vitro, we considered whether long-term exosome exposure altered phenotype and molecular signals in vivo. We first performed a distribution experiment in vivo to determine whether GH1-exo concentrate in murine organs. DiD-labeled GH1-exo intravenously administered to C57BL/6 female mice yielded strong fluorescent signals in the liver, spleen, and lung compared to control mouse receiving unlabeled exosomes (Fig. 6). Moderate signals were also observed in the heart, ovary, abdominal fat, intestine, kidney, and brain tissues (not shown).

Figure 6.

In vivo distribution of GH1-derived exosomes (GH1-exo) in mice. A, Fluorescence signal of DiD-labeled GH1-exo in murine tissues excised 4 and 20 hours after intravenous injection (5 × 108 particles/mouse). Unlabeled GH1-exo was used as control. B, Densitometry analysis of tissue fluorescence. Radiant efficiency: Experiments were repeated twice; representative results are presented.

To assess in vivo exosome function, we then injected 4-week-old female Wistar rats with intravenous GH1-exo (5 × 109 particles/200 g, n = 4), FR-derived exosomes (FR-exo, 5 × 109 particles/200 g, n = 3), or PBS as control (n = 3) twice weekly for 4 weeks. Body weight, length, and morning blood glucose were not significantly altered for the duration of the experiment, and heart, liver, and kidney weight and gross histology were unchanged after euthanasia. However, hepatic RNA sequencing identified 280 genes altered by GH1-exo compared to vehicle injection, with 77 specifically regulated by GH1-exo compared to FR-exo. KEGG pathway analysis of these 280 genes influenced by GH1-exo showed several significantly affected hepatic signaling pathways elicited by GH1-exo (P < .05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

GH1-derived exosomes regulate hepatic signaling pathways in vivo

| Pathway | Count | P | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| rno04141: protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum | 11 | 1.37E-04 | DERL2, ATF4, ERO1B, TXNDC5, MAN1A1, PDIA4, DNAJC3, EIF2AK2, LMAN1, CANX, SSR3 |

| rno05164: influenza A | 10 | 7.38E-04 | TMPRSS2, IRF7, RSAD2, OAS1A, DNAJC3, EIF2AK2, MX2, STAT2, CXCL10, ADAR |

| rno05143: African trypanosomiasis | 5 | .002 | HBA-A1, APOA1, LOC103694857, LOC100134871, HBB |

| rno04668: TNF signaling pathway | 6 | .020 | CXCL1, ATF4, CREB3L2, RIPK3, BCL3, CXCL10 |

| rno03320: PPAR signaling pathway | 5 | .024 | LPL, APOA1, FABP1, GK, FABP5 |

| rno05162: Measles | 6 | .044 | IRF7, OAS1A, EIF2AK2, MX2, STAT2, ADAR |

| rno04623: cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway | 4 | .046 | IRF7, RIPK3, CXCL10, ADAR |

Abbreviations: PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

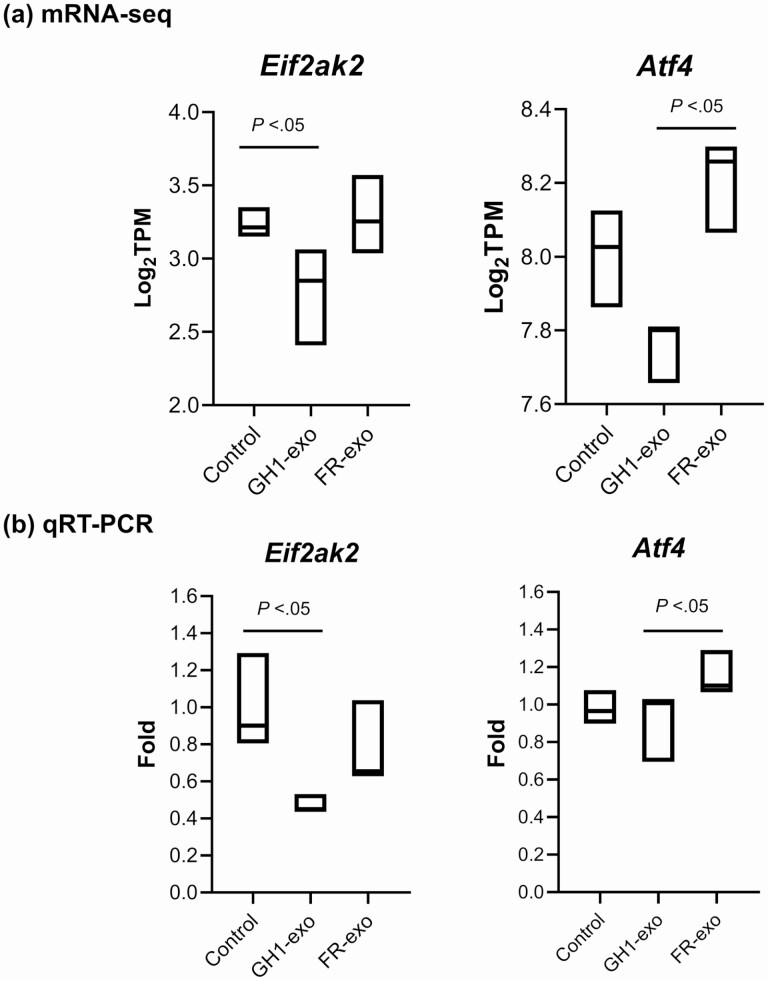

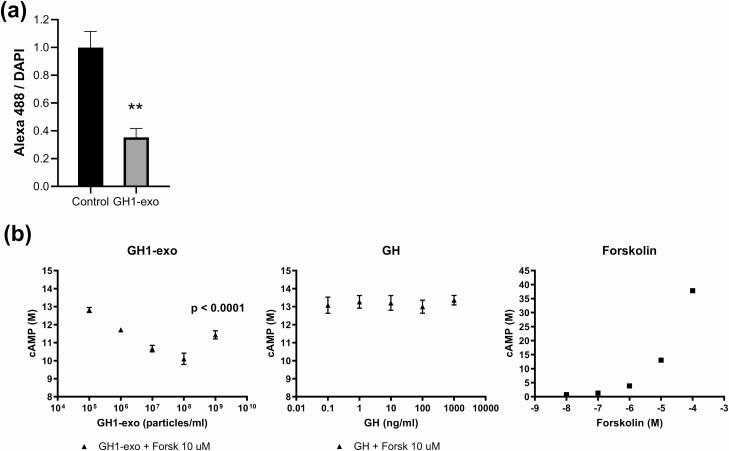

GH1-derived Exosomes Attenuate Eif2ak2/Atf4 Signaling, Suppress Amino Acid Biosynthesis, and Inhibit 3′,5′-Cyclic Adenosine 5′-Monophosphate

After analyzing altered genes/pathways associated with GH1-exo treatment in vivo and in vitro, EIF-2 kinase gene Eif2ak2 (encoding PKR) and the downstream Atf4 gene came to our attention. These genes are involved in integrated stress responses, amino acid biosynthesis, and metabolic processes (28-33). Hepatic mRNA expression of Eif2ak2 and Atf4 was decreased in rats injected with GH1-exo but not with FR-exo or control as assessed by mRNA-seq (Fig. 7A). qRT-PCR results confirmed decreased Eif2ak2 and Atf4 expression with GH1-exo injection (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, the amino acid biosynthesis pathway was attenuated with GH1-exo treated but not GH- and PRL-treated rat primary hepatocytes in vitro (see Fig. 5). GH1-exo suppressed hepatocyte protein synthesis by up to 65% in rat hepatocytes (P < .001, t test) (Fig. 8A). Moreover, we found that GH1-exo, but not GH, decreased forskolin-induced cAMP by up to 21% (P < .001, one-way ANOVA), and forskolin dose-dependently stimulated cAMP as expected for a positive control (Fig. 8B). These results suggest that GH1-derived exosomes may be involved in stress responses, amino acid biosynthesis, and metabolic processes by regulating Eif2ak2/Atf4 signaling.

Figure 7.

GH1-derived exosomes (GH1-exo) attenuated Eif2ak2 and Atf4 expression in rat livers as assessed by messenger RNA sequencing (mRNA-seq) and quantitative real time–polymorphism chain reaction (qRT-PCR). A, mRNA-seq results of Eif2ak2 and Atf4 expression (transcripts per million; TPM) in rat livers treated with GH1-exo (n = 4), FR-exo (n = 3) or phosphate-buffered saline as control (n = 3). B, qRT-PCR validation of Eif2ak2 and Atf4 mRNA expression. P less than .05, unpaired 2-tailed t test with Bonferroni correction.

Figure 8.

GH1-derived exosomes (GH1-exo) suppressed amino acid biosynthesis and inhibited cAMP (3′,5′-cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate). A, Active protein synthesis in rat primary hepatocytes treated with GH1-exo vs phosphate-buffered saline controls. Fluorescence with Alexa Fluor 488 was read to detect newly synthesized proteins and nuclear DAPI (diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining measured to adjust for cell numbers (n = 8). **P less than .001, t test. B, cAMP affected by GH1-exo plus forskolin (left) (P < .001, one-way ANOVA), GH plus forskolin (middle), or increasing doses of forskolin as a positive control (right) in rat primary hepatocytes. Experiments were repeated 3 times and representative experiment presented. Quantitative results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4).

GH1-derived Exosomes Attenuate Malignant HCT116 Cell Motility In Vitro

As exosomes usually carry signatures similar to their respective cell of origin (6) and most pituitary tumor cells are benign, we investigated GH1-derived exosome actions on peripheral malignant cell motility. Because no cancerous pituitary cells are available and exosomes transfer cargoes between rodent and human cells (9), we employed human malignant HCT116 cells for migration and invasion assays. HCT116 cells were incubated for 24 hours with either rGH (500 ng/mL), GH1-exo (109 particles in 1 mL/well), or PBS as control, or cocultured with GH1 cells. Cocultured GH1 cells produce both exosomes and GH, acting on HCT116 cells in the insert. GH1-exo incubation as well as cocultured GH1 cells both suppressed HCT116 migration and invasion (Fig. 9A). GH1-exo decreased HCT116 migration by 28% (P < .05), and GH1 cell cocultures attenuated motility by 38% (P < .01), whereas rGH treatment increased migration by 23% (P < .05) (t test). Similarly, HCT116 invasion was attenuated by both GH1-exo (40% reduction, P < .05) and coculture (71% reduction, P < .01), but was elevated significantly by rGH (1.6-fold, P < .01) (data not shown).

Figure 9.

GH1-derived exosomes (GH1-exo) attenuated malignant HCT116 cell motility in vitro. HCT116 cells were treated with GH1-exo, recombinant rat growth hormone (rGH), or phosphate-buffered saline as control or cocultured with GH1 cells. A, Representative images showing migrating cells counted at 24 hours (left) and quantitative results (right) presented as mean ± SEM (n = 8). Migrated cells were quantified in 4 random fields per insert and each sample assayed in duplicate. B, Percentage of area closure after scrape measured at 24 and 48 hours. Each sample was assayed in quadruplicate. Quantitative results presented as mean ± SEM (n = 4). All experiments were repeated at least 3 times. *P less than .05 vs control, t test; **P less than .01 vs control, t test.

To assess wound healing, HCT116 cells were treated with rGH (500 ng/mL), GH1-exo (109 particles in 1 mL/well), or PBS as control or cocultured with GH1 cells for up to 48 hours. GH1-exo treatment and GH1 cell coculture slowed wound healing by 48% and 65% at 24 hours and 53% and 46% at 48 hours, respectively; however, rGH did not change scrape closure as compared to controls (Fig. 9B). Taken together, these results suggest that GH1-exo attenuates malignant cell motility in vitro.

We next treated HCT116 cells with GH1-exo and performed mRNA-seq to further elucidate downstream signaling pathways. HCT116 cells were incubated with GH1-exo (5 × 103 particles/cell) or PBS as control and harvested after 48 hours. More than 500 downstream genes were significantly altered by GH1-exo compared to nontreated controls. KEGG pathway analysis of the top 300 genes showed that several cancer-related pathways were altered by GH1-exo, including p53 and MAPK signaling (Table 4). Interestingly, similar to what was detected in rat hepatocytes, ATF4 was also decreased by GH1-exo in HCT116 cells.

Table 4.

Signaling pathways altered by GH1-derived exosomes in HCT116 cells

| Pathway | Count | P | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| hsa04115: p53 signaling pathway | 11 | 5.81E-07 | PPM1D, TP53I3, SERPINB5, BBC3, DDB2, MDM2, PIDD1, FAS, SFN, SESN2, GADD45A |

| hsa05202: transcriptional misregulation in cancer | 11 | .002 | NUPR1, PER2, HOXA10, MDM2, BCL6, NGFR, BCL2L1, SIX4, HMGA2, MYC, DDIT3 |

| hsa03010: ribosome | 9 | .005 | RPS25, RPL41, RPL32, RPL9, RPLP1, RPS9, RPL39, RPL36AL, RPS24 |

| hsa04010: MAPK signaling pathway | 12 | .011 | FGF19, DUSP5, FOS, ATF4, RPS6KA3, TAOK1, NR4A1, PRKACB, FAS, GADD45A, MYC, DDIT3 |

| hsa00260: glycine, serine and threonine metabolism | 4 | .040 | ALAS1, PHGDH, GCAT, PSAT1 |

| hsa05162: measles | 7 | .046 | TNFRSF10A, TNFRSF10B, BBC3, MSN, FAS, EIF2AK2, STAT1 |

| hsa04068: FoxO signaling pathway | 7 | .048 | PLK3, PLK2, MDM2, BNIP3, BCL6, PCK2, GADD45A |

Abbreviation: MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase.

GH1-derived Exosomes Suppress Tumor Metastasis In Vivo

To assess the role of GH1-exo in development of tumor metastases in vivo, we implanted HCT116 cells (5 × 105) into the spleen of nude mice and administered intravenously GH1-exo (1010 particles/mouse) or PBS as control twice a week for 5 weeks (n = 10 each). No significant differences in phenotype were observed between the groups. As shown in Fig. 10, 5 of 10 mice in each group exhibited visible primary splenic tumors, with similar average volumes. However, 6 control mice (60%) developed liver tumors (1-12 metastatic loci, average volume 72.1 ± 34.5 mm3), whereas 3 mice in the GH1-exo–administered group (30%) developed fewer and smaller liver tumors (1-2 metastatic loci, average volume 2 ± 1.4 mm3), showing a lower incidence and a notable decrease of tumor volumes (P = .05, t test). Metastatic tumors were also commonly observed around the peritoneum but rarely in the intestine, pancreas, adrenal, and kidney. As compared to controls, GH1-exo administration resulted in a 57% decrease of average peritoneal tumor volumes (338 ± 124.2 vs 146 ± 78.5 mm3) and attenuated all-site metastases by 43% (434 ± 126.2 vs 247 ± 103.2 mm3) compared with controls (Fig. 10). These results are consistent with in vitro cell motility findings, suggesting that GH1-exo may attenuate tumor metastases in vivo.

Figure 10.

GH1-derived exosomes (GH1-exo) suppressed tumor metastasis in vivo. A, Splenic tumors, and B, liver; C, peritoneal; and D, all metastases detected in nude mice implanted with HCT116 cells suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing GH1-exo particles or in PBS only as control (n = 10 per group), and intravenously administered GH1-exo or PBS twice weekly for 5 weeks.

Discussion

Although circulating and paracrine hormones and cytokines classically function as mediators of intercellular communication, our findings suggest that exosomes derived from pituitary cells may also fulfill this function.

Exosome isolation requires optimization for maximum yield, purity, and assay reproducibility. We followed MISEV2018 guidelines for exosome preparation and identification (34), and coupled it with a comprehensive combination of techniques specific to pituitary exosome concentration. Surface markers, GW4869 sensitivity, size, and RNA content all are consistent with the identification of pituitary EVs as exosomes. Given that pituitary cells produce abundant trophic hormones, separation from contaminating hormones, which may remain in concentrated exosomes, is critical to attribute our results to nonhormonal exosome actions. Our rigorous approach described in “Materials and Methods” enabled optimization both of purity and yield of pituitary-derived exosomes from cells that produce abundant GH, while minimizing hormone contamination and preparation time.

Thermal and oxidative stress, hypoxia, genotoxic stress, and chemotherapeutic agents provoke increased exosome release (22-27), and may modify exosome protein and microRNA composition (35, 36) to modulate related immune responses, cancer cell death evasion, and treatment resistance (37-40). Mechanisms for stress-induced exosome secretion are largely unknown, although cell senescence and tumor-suppressor gene p53 are likely involved (41-44). Cortisol is an adrenal steroid hormone induced in response to stress (45-47), and we observed that hydrocortisone induced pituitary exosome release.

We found that GH1-exo attenuated hepatic expression of Eif2ak2 and downstream Atf4, all of which are involved in integrated stress responses (28, 29). Stress modulates EIF2α activity and ATF4 expression, regulating amino acid biosynthesis and metabolism (30-33). We also observed that GH1-exo attenuated amino acid biosynthesis and suppressed cAMP, suggesting that GH1-exo may attenuate EIF2α/ATF4 activity to compromise stress responses in recipient hepatocytes.

Cancer-derived exosomes play important roles in the tumor microenvironment, facilitating cell-cell communication between malignant and surrounding normal cells (48, 49), and delivering functional mRNAs, microRNAs, and proteins that induce cell transformation (9, 50, 51). Cancer-derived exosomes also trigger angiogenesis, promote migration and invasion, and mediate metastases (52-55). Pituitary tumors are benign (1) and qRT-PCR validation results indicated that pituitary exosomes carry signatures concordant with cell of origin, suggesting that pituitary exosomes possess benign characteristics. In this respect, we observed that GH1-exo attenuated migration and invasion and slowed wound healing in HCT116 cells, while intravenous GH1-exo attenuated tumor metastases in nude mice harboring splenic HCT116 implants. KEGG pathway analysis indicating altered p53 and MAPK pathways may partially explain the underlying motility attenuation. Our findings thus suggest that pituitary exosomes may transfer benign characteristics to malignant cells to confer reduced cell motility, or may alter the tumor microenvironment to attenuate metastases.

Characterization, biogenesis, constituents, actions, and related mechanisms of pituitary exosomes remain poorly understood. We isolated pituitary-derived exosomes, profiled exosomal RNAs, delineated GH1-exo–regulated hepatic pathways, and observed GH1-exo involvement in stress response and metastasis formation. Our results suggest pituitary exosomes function as nonhormonal messengers mediating intercellular communication.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Cedars-Sinai Genomics Core for assistance with RNA sequencing, Dr Geoffrey de Couto for assistance with GH1-exo distribution and NanoSight, and Shira Berman for assistance in manuscript preparation.

Financial Support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant No. R01DK113998 to S.M.) and the Doris Factor Molecular Endocrinology Laboratory at Cedars-Sinai. Support for biostatistics was provided in part by the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Science UCLA CTSI (grant No. UL1TR001881).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- cAMP

3′,5′-cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate

- DE

differentially expressed

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- EDFBS

exosome-depleted fetal bovine serum

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- EV

extracellular vesicle

- FC

fold change

- GH

growth hormone

- GH1-exo

GH1-derived exosomes

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- mRNA-seq

mRNA sequencing

- NTA

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PRL

prolactin

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- rGH

recombinant rat growth hormone

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

Additional Information

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Some or all data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Melmed S. Pituitary-tumor endocrinopathies. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):937-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neave N. Hormones and Behaviour: A Psychological Approach. Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Melmed S. Acromegaly pathogenesis and treatment. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(11):3189-3202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang-Doran I, Zhang CY, Vidal-Puig A. Extracellular vesicles: novel mediators of cell communication in metabolic disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017;28(1):3-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ibrahim A, Marbán E. Exosomes: fundamental biology and roles in cardiovascular physiology. Annu Rev Physiol. 2016;78:67-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367(6478). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maia J, Caja S, Strano Moraes MC, Couto N, Costa-Silva B. Exosome-based cell-cell communication in the tumor microenvironment. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2018;6:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Das Gupta A, Krawczynska N, Nelson ER. Extracellular vesicles-the next frontier in endocrinology. Endocrinology. 2021;162(9):bqab133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, Sjöstrand M, Lee JJ, Lötvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(6):654-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ramachandran S, Palanisamy V. Horizontal transfer of RNAs: exosomes as mediators of intercellular communication. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2012;3(2):286-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang Y, Liu YT, Tang H, et al. Exosome-transmitted lncRNA H19 inhibits the growth of pituitary adenoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(12):6345-6356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xiong Y, Tang Y, Fan F, et al. Exosomal hsa-miR-21-5p derived from growth hormone-secreting pituitary adenoma promotes abnormal bone formation in acromegaly. Transl Res. 2020;215:1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ooi GT, Tawadros N, Escalona RM. Pituitary cell lines and their endocrine applications. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;228(1-2):1-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhou C, Jiao Y, Wang R, Ren SG, Wawrowsky K, Melmed S. STAT3 upregulation in pituitary somatotroph adenomas induces growth hormone hypersecretion. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(4):1692-1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(1):15-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57(1):289-300. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):44-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ben-Shlomo A, Wawrowsky K, Melmed S. Constitutive activity of somatostatin receptor subtypes. Methods Enzymol. 2010;484:149-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Melmed S. Insulin suppresses growth hormone secretion by rat pituitary cells. J Clin Invest. 1984;73(5):1425-1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hedlund M, Nagaeva O, Kargl D, Baranov V, Mincheva-Nilsson L. Thermal- and oxidative stress causes enhanced release of NKG2D ligand-bearing immunosuppressive exosomes in leukemia/lymphoma T and B cells. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e16899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang T, Gilkes DM, Takano N, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factors and RAB22A mediate formation of microvesicles that stimulate breast cancer invasion and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(31):E3234-E3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang Y, Chen Y, Zhang F, Zhao Q, Zhong H. Increased anti-tumour activity by exosomes derived from doxorubicin-treated tumour cells via heat stress. Int J Hyperthermia. 2015;31(5):498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gobbo J, Marcion G, Cordonnier M, et al. Restoring anticancer immune response by targeting tumor-derived exosomes with a HSP70 peptide aptamer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(3):djv330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vulpis E, Cecere F, Molfetta R, et al. Genotoxic stress modulates the release of exosomes from multiple myeloma cells capable of activating NK cell cytokine production: role of HSP70/TLR2/NF-kB axis. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(3):e1279372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bandari SK, Purushothaman A, Ramani VC, et al. Chemotherapy induces secretion of exosomes loaded with heparanase that degrades extracellular matrix and impacts tumor and host cell behavior. Matrix Biol. 2018;65:104-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Taniuchi S, Miyake M, Tsugawa K, Oyadomari M, Oyadomari S. Integrated stress response of vertebrates is regulated by four eIF2α kinases. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pakos-Zebrucka K, Koryga I, Mnich K, Ljujic M, Samali A, Gorman AM. The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep. 2016;17(10):1374-1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harding HP, Zhang Y, Zeng H, et al. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol Cell. 2003;11(3):619-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ameri K, Harris AL. Activating transcription factor 4. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40(1):14-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baird TD, Wek RC. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2 phosphorylation and translational control in metabolism. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(3):307-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Han J, Back SH, Hur J, et al. ER-stress-induced transcriptional regulation increases protein synthesis leading to cell death. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(5):481-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018;7(1):1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. de Jong OG, Verhaar MC, Chen Y, et al. Cellular stress conditions are reflected in the protein and RNA content of endothelial cell-derived exosomes. J Extracell Vesicles. 2012;1:10.3402/jev.v1i0.18396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Harmati M, Gyukity-Sebestyen E, Dobra G, et al. Small extracellular vesicles convey the stress-induced adaptive responses of melanoma cells. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):15329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Beninson LA, Fleshner M. Exosomes: an emerging factor in stress-induced immunomodulation. Semin Immunol. 2014;26(5):394-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fleshner M, Crane CR. Exosomes, DAMPs and miRNA: features of stress physiology and immune homeostasis. Trends Immunol. 2017;38(10):768-776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vulpis E, Soriani A, Cerboni C, Santoni A, Zingoni A. Cancer exosomes as conveyors of stress-induced molecules: new players in the modulation of NK cell response. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3):611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. O’Neill CP, Gilligan KE, Dwyer RM. Role of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in cell stress response and resistance to cancer therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(2):136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yu X, Harris SL, Levine AJ. The regulation of exosome secretion: a novel function of the p53 protein. Cancer Res. 2006;66(9):4795-4801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lehmann BD, Paine MS, Brooks AM, et al. Senescence-associated exosome release from human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68(19):7864-7871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lespagnol A, Duflaut D, Beekman C, et al. Exosome secretion, including the DNA damage-induced p53-dependent secretory pathway, is severely compromised in TSAP6/Steap3-null mice. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(11):1723-1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Borrelli C, Ricci B, Vulpis E, et al. Drug-induced senescent multiple myeloma cells elicit NK cell proliferation by direct or exosome-mediated IL15 trans-presentation. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6(7):860-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chrousos GP. Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5(7):374-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. van der Valk ES, Savas M, van Rossum EFC. Stress and obesity: are there more susceptible individuals? Curr Obes Rep. 2018;7(2):193-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Spencer-Segal JL, Akil H. Glucocorticoids and resilience. Horm Behav. 2019;111:131-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 2013;19(11):1423-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li I, Nabet BY. Exosomes in the tumor microenvironment as mediators of cancer therapy resistance. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Skog J, Würdinger T, van Rijn S, et al. Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(12):1470-1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Melo SA, Sugimoto H, O’Connell JT, et al. Cancer exosomes perform cell-independent microRNA biogenesis and promote tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2014;26(5):707-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Becker A, Thakur BK, Weiss JM, Kim HS, Peinado H, Lyden D. Extracellular vesicles in cancer: cell-to-cell mediators of metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2016;30(6):836-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Weidle UH, Birzele F, Kollmorgen G, Rüger R. The multiple roles of exosomes in metastasis. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2017;14(1):1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tian W, Liu S, Li B. Potential role of exosomes in cancer metastasis. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:4649705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Adem B, Vieira PF, Melo SA. Decoding the biology of exosomes in metastasis. Trends Cancer. 2020;6(1):20-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.