Abstract

We applied the high-resolution genotyping technique fluorescent amplified-fragment length polymorphism (FAFLP) analysis to 71 isolates of a single phage type (PT8) of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE)-characterized verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157. Twenty-seven similar, but not identical, groupings were defined by both FAFLP analysis and the PFGE profiles. Given the FAFLP analysis conditions described here, these two methods exhibited equivalent discriminatory powers.

Verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 (VTEC O157) is a food-borne pathogen of considerable public health importance. In sentinel surveillance systems sporadic cases are more frequently identified than outbreaks.

Strains of VTEC O157 can be differentiated into more than 80 phage types (9). In the Laboratory of Enteric Pathogens initial differentiation of isolates is effected by phage typing followed by other methods that obtain higher levels of discrimination. Several molecular biology-based techniques have been applied in order to obtain the further discrimination required for outbreak investigations; of these pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) is the most widely used in practice (4). PFGE usually has the resolving power needed to investigate outbreaks, but it may not always resolve isolates belonging to a single common phage type.

The genome sampling technique of amplified-fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) analysis, in which subsets of genomic DNA fragments from digests of isolates are selectively amplified and compared, can discriminate strain genotypes within many bacterial species (12). When they are fluorescently labeled, these fragments can be visualized with the laser detection system of an automated sequencer. The potential benefits of using fluorescent AFLP (FAFLP) analysis for subtyping of VTEC O157 isolates have been partly established (3, 14). In 1997 and 1998, strains belonging to a single phage type, PT8, represented about 17% of total human VTEC O157 isolates from England and Wales (1) and were responsible for several major outbreaks.

In order to determine whether FAFLP analysis is appropriate for the study of outbreaks caused by a single phage type (5), we analyzed 71 XbaI PFGE-characterized isolates of VTEC O157 PT8 from England and Wales between 1996 and 1998 (13). Forty-seven isolates from 11 outbreaks were studied (Table 1). Twenty-four other isolates from sporadic human infections were studied. The outbreak strains had been assigned to nine PFGE groups, PT8-1 to PT8-9 (G. Willshaw, unpublished data).

TABLE 1.

Differentiation by FAFLP analysis and PFGE of strains VTEC O157 PT8

| Isolate groupa | Isolate no. | FAFLP group | PFGE group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outbreak isolates | |||

| A | 13, 49, 50 | I | PT8-1 |

| B | 51, 14 | VIII | PT8-2 |

| C | 15, 52–55 | V, except isolate 55 (unique) | PT8-3 |

| D | 16, 17–20 | I | PT8-4 |

| E | 10, 11, 12 | IX, one to two fragment differences within group | PT8-5 |

| F | 9, 56, 57 | X | PT8-6 |

| G | 6, 8 | VI | PT8-7 |

| H | 21, 22 | II | PT8-8 |

| I | 5, 58, 59 | I | PT8-9 |

| J | 3, 4, 23, 24, 60–66 | I, except isolates 61–64 (VII) | PT8-1 |

| K | 1, 2, 67–72 | V | PT8-3 |

| Sporadic isolates | 25 | Unique | e |

| 26 | Unique | f | |

| 27 | I | g | |

| 28 | Unique | j | |

| 29 | Unique | l | |

| 30 | Unique | PT8-5 | |

| 31 | Unique | m | |

| 32 | Unique | v | |

| 33 | Unique | u | |

| 34 | Unique | s | |

| 35 | III | r | |

| 36 | Unique | q | |

| 37 | I | PT8-4 | |

| 38 | Unique | c | |

| 39 | Unique | k | |

| 40 | IV | w | |

| 41 | Unique | PT8-1 | |

| 42 | V | PT8-3 | |

| 43 | IV | a | |

| 44 | III | n | |

| 45 | IV | a | |

| 46 | V | p | |

| 47 | Unique | d | |

| 48 | VI | PT8-7 |

Outbreaks occurred in England and Wales between 1996 and 1998. Sporadic isolates were from unlinked human cases between September 1997 and November 1998.

FAFLP reactions and analysis were carried out as described previously (3), except that three additional primers that ended with TG, TC, or TT at the 3′ end were also used. With this combination of four distinct two-base selective MseI primers, a total of 46 discriminatory bands in the 100 to 506-bp size range were scored as present or absent for each sample. DNA fingerprints (FAFLP profiles; e.g., see Fig. 1) were analyzed by successive clustering by an average-linkage method of clustering (unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages), yielding the tree shown in Fig. 2. All samples were examined twice, and all duplicates gave FAFLP profiles identical to those of the originals. Gel and amplification controls always gave identical profiles. The FAFLP analysis was done without knowledge of the PFGE results.

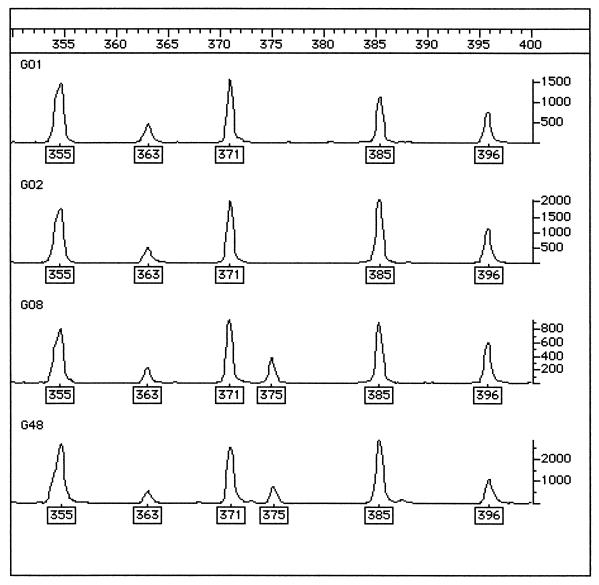

FIG. 1.

Genotyper output of FAFLP analysis of isolates 1, 2 (FAFLP group V) 8, and 48 (FAFLP group VI) in the fragments size range of 350 to 400 bp. The boxed numbers under the peaks of the traces are the fragment sizes (in base pairs) assigned by comparison with the standard curve generated from the internal size standard. The fragment at 375 bp is the only fragment separating the profiles of FAFLP groups V and VI, represented in Fig. 2 as the shortest distance between two different isolates.

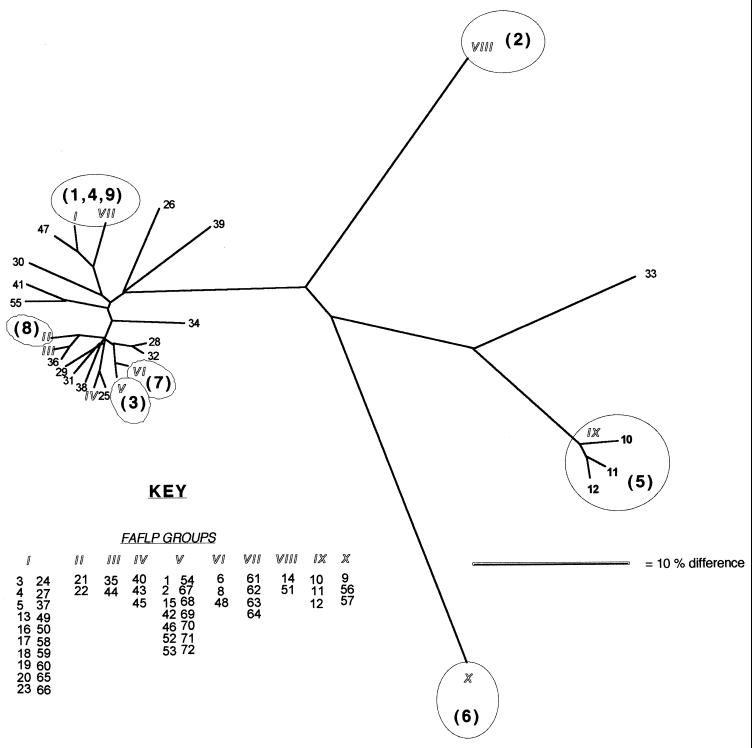

FIG. 2.

Distance tree of 71 E. coli O157 PT8 isolates obtained by FAFLP analysis. Branch lengths that are similar to and that include those between FAFLP groups V and VI reflect a single FAFLP fragment difference. The outbreak groups determined by PFGE are presented in parentheses.

In general, PT8 outbreaks that were differentiated from each other by FAFLP analysis were also distinguished by PFGE (Table 1). Four isolates (isolates 61 to 64) from outbreak J that shared a single PFGE profile (PT8-1) were assigned to a separate FAFLP group, group VII. This group differed by two FAFLP fragment positions from FAFLP group I. Similarly, isolate 55 possessed a unique FAFLP profile, with two fragment differences from the others in PFGE group PT8-3, which fell into FAFLP group V. The two FAFLP profiles which contained most isolates were groups I and V, which contained 20 and 14 isolates, respectively. Conversely, PFGE groups PT8-1, PT8-4, and PT8-9 were distinguishable by one to three fragment differences, whereas by FAFLP analysis most outbreak isolates that had these three PFGE profiles were designated a single genotypic clone, FAFLP group I (Fig. 1).

Among the 24 sporadic isolates, FAFLP analysis differentiated 19 profiles. Three of these profiles, belonging to FAFLP groups I (isolates 27 and 37), V (isolates 42 and 46), and VI (isolate 48), were also found among outbreak isolates. Two FAFLP groups (groups III and IV) were found only among sporadic strains. The profile of sporadic isolate 30 had 13 FAFLP fragment differences from the profiles of outbreak isolates 10, 11, and 12 that were of the same PFGE group, PT8-5. By comparison, 23 sporadic isolates were differentiated from each other by PFGE, although 5 isolates had profiles that had also been recognized in outbreak isolates (isolates 30, 37, 41, 42, and 48; Table 1).

In summary, among all 71 isolates studied here, 27 genotypes were defined by FAFLP analysis and 27 had been defined by PFGE, suggesting that, with the particular combination of selective primers used for FAFLP analysis, either method yields the same level of discrimination. Minor differences by FAFLP analysis (usually two to three fragments) separated certain isolates that were designated identical by PFGE, but PFGE discriminated certain isolates placed in the same FAFLP group (group I). However, further discrimination is likely by FAFLP analysis with different selective primer combinations, a feature of this methodology.

A recent publication by Zhao and colleagues (14), who used selective primer combinations different from those described here, reported that FAFLP analysis exhibited a higher discriminatory power for VTEC O157:H7 than PFGE. However, that study did not include phage typing, so the potential for their method to resolve a single phage type cannot be compared with that of our method.

The costs of both FAFLP analysis and PFGE have been determined by Olive and Bean (10). While the setup costs for FAFLP analysis are higher ($45,000 to $130,000) than those for PFGE ($10,000 to $20,000), the cost per sample is marginally less ($20 for FAFLP analysis but $22 for those for PFGE). However, FAFLP analysis takes approximately two-thirds of the time required for PFGE, is inherently more flexible, and yields many more datum points per genome (6–8) and its results can be read by a machine.

The definition of clonality by either FAFLP analysis or PFGE depends on what distinguishing criteria, in terms of numbers of fragment differences, are applied. Early published criteria for the interpretation of PFGE profiles (11) have been modified in practice to allow a combination of epidemiological context and single fragment differences to define clonality (E. Ribot, unpublished data). Our results show that for VTEC O157:H7, as for other pathogens (6–8), if the epidemiological context supports it, a single amplified fragment difference in FAFLP analysis may define a new strain. Conversely, a one- to two-fragment difference between isolates may indicate that they should be assigned to the same epidemiological clone (such as FAFLP group IX). These questions are determined in practice by the epidemiological context.

As a genotyping methodology, FAFLP analysis exhibits certain theoretical and practical advantages over existing techniques. By comparison with PFGE, it generates a considerably larger number of datum points and the amplified fragments are precisely sized (±1 bp). It is inherently flexible, and its discriminatory power can be increased or decreased through the use of different selective primers but the same digestion-ligation reaction. Furthermore, it can be based directly on whole genome sequences (2, 3, 7), soon to be available for VTEC O157.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anonymous. Vero cytotoxin producing Escherichia coli O157: phage types reported in 1998. Communic Dis Weekly Rep. 1999;9:291. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold C, Metherell L, Clewley J P, Stanley J. Predictive modelling of fluorescent AFLP: a new approach to the molecular epidemiology of E. coli. Res Microbiol. 1999;150:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(99)80044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold C, Metherell L, Willshaw G, Maggs A, Stanley J. Predictive fluorescent amplified-fragment length polymorphism analysis of Escherichia coli: high-resolution typing method with phylogenetic significance. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1274–1279. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.5.1274-1279.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett T J, Lior H, Green J H, Khakharia R, Wells J G, Bell B P, Greene K D, Lewis J, Griffin P M. Laboratory investigation of a multistate food-borne outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and phage typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;12:3013–3017. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.3013-3017.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohm H, Karch K. DNA fingerprinting of Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2169–2172. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.8.2169-2172.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desai M, Tanna A, Wall R, Efstratiou A, George R, Stanley J. Fluorescent amplified-fragment length polymorphism analysis of an outbreak of group A streptococcal invasive disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3133–3137. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3133-3137.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goulding J N, Stanley J, Saunders N, Arnold C. Genome sequence-based fluorescent amplified fragment length polymorphism (FAFLP) analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1121–1126. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.3.1121-1126.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grady R, Desai M, O'Neill G, Cookson B, Stanley J. Fluorescent amplified-fragment length polymorphism analysis of the MRSA epidemic. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;187:27–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khakhria R, Duck D, Lior H. Extended phage typing scheme for Escherichia coli O157:H7. Epidemiol Infect. 1990;105:511–520. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800048135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olive D M, Bean P. Principles and applications of methods for DNA-based typing of microbial organisms. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1661–1669. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1661-1669.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vos P, Hogers R, Bleeker M, Reijans M, van de Lee T, Hornes M, Frijters A, Pot J, Peleman J, Kulper M, Zabeau M. AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willshaw G A, Smith H R, Cheasty T, Wall P G, Rowe B. Vero cytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 outbreaks in England and Wales, 1995: phenotypic methods and genotypic subtyping. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:561–565. doi: 10.3201/eid0304.970422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao S, Mitchell S E, Meng J, Kresovich S, Doyle M P, Dean R E, Casa A M, Weller J W. Genomic typing of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by semi-automated fluorescent AFLP analysis. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:107–113. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]