Significance

Anthrax is a deadly infection caused by exposure to Bacillus anthracis bacteria. Anthrax lethal toxin (LeTx) has long been recognized as a major determinant of lethal anthrax, which paralyzes the host’s immune defenses by killing off macrophages. Despite the importance of macrophage cytotoxicity in anthrax pathogenesis, the signaling pathways underlying cell death of B. anthracis-infected macrophages are poorly understood. This study shows that infection with live B. anthracis or LeTx intoxication sensitizes macrophages to TNF-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation and caspase-8–mediated apoptosis. Moreover, caspase-8–mediated apoptosis is shown to promote anthrax-associated lethality in vivo. Collectively, the study establishes TNF- and RIPK1 kinase activity–dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation and macrophage apoptosis as key host–pathogen mechanisms in lethal anthrax.

Keywords: anthrax, TNF, infection, apoptosis, NLRP3 inflammasome

Abstract

Lethal toxin (LeTx)-mediated killing of myeloid cells is essential for Bacillus anthracis, the causative agent of anthrax, to establish systemic infection and induce lethal anthrax. The “LeTx-sensitive” NLRP1b inflammasome of BALB/c and 129S macrophages swiftly responds to LeTx intoxication with pyroptosis and secretion of interleukin (IL)-1β. However, human NLRP1 is nonresponsive to LeTx, prompting us to investigate B. anthracis host–pathogen interactions in C57BL/6J (B6) macrophages and mice that also lack a LeTx-sensitive Nlrp1b allele. Unexpectedly, we found that LeTx intoxication and live B. anthracis infection of B6 macrophages elicited robust secretion of IL-1β, which critically relied on the NLRP3 inflammasome. TNF signaling through both TNF receptor 1 (TNF-R1) and TNF-R2 were required for B. anthracis-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation, which was further controlled by RIPK1 kinase activity and LeTx-mediated proteolytic inactivation of MAP kinase signaling. In addition to activating the NLRP3 inflammasome, LeTx-induced MAPKK inactivation and TNF production sensitized B. anthracis-infected macrophages to robust RIPK1- and caspase-8–dependent apoptosis. In agreement, purified LeTx triggered RIPK1 kinase activity- and caspase-8–dependent apoptosis only in macrophages primed with TNF or following engagement of TRIF-dependent Toll-like receptors. Consistently, genetic and pharmacological inhibition of RIPK1 inhibited NLRP3 inflammasome activation and apoptosis of LeTx-intoxicated and B. anthracis-infected macrophages. Caspase-8/RIPK3-deficient mice were significantly protected from B. anthracis-induced lethality, demonstrating the in vivo pathophysiological relevance of this cytotoxic mechanism. Collectively, these results establish TNF- and RIPK1 kinase activity–dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation and macrophage apoptosis as key host–pathogen mechanisms in lethal anthrax.

The bacterial pathogen Bacillus anthracis is a rare, but notoriously deadly pathogen in humans with mortality rates from anthrax varying from ∼20% for cutaneous anthrax to 80% and higher for inhalation anthrax. This encapsulated, spore-forming, gram-positive bacterial pathogen efficiently kills infected hosts through the systemic action of two secreted toxins (1). Edema toxin (EdTx) and lethal toxin (LeTx) share a receptor-binding protein named protective antigen (PA) that transfers the edema factor (EF) and lethal factor (LF) moieties into the cytosol of target cells, where the latter exert their cytopathic and cytotoxic effects (1, 2).

Studies in macaques and mice identified LeTx as a major virulence factor driving systemic dispersion of vegetative bacteria, which ultimately may result in fatal anthrax (3, 4). LeTx internalization by macrophages drives macrophage cell death, which is a key early pathogenic event during spore infections that allows vegetative bacteria to establish systemic infection of its host (5). LF is a highly selective Zn2+-dependent metalloprotease that, once internalized, cleaves a subset of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases (MAPKKs) to abolish downstream MAPK signaling in LeTx-intoxicated macrophages (6). In addition, macrophages of BALB/c and 129S mice express a LeTx-sensitive Nlrp1b allele that responds to LF-mediated cleavage with NLRP1b inflammasome activation and pyroptosis (7–9). However, human NLRP1 and the Nlrp1b allele of C57BL/6J (B6) macrophages are nonresponsive to LeTx, suggesting that B. anthracis may induce macrophage cell death through alternative mechanisms that are poorly understood.

Here, we show that B. anthracis infection induces NLRP3 inflammasome activation and caspase-8–mediated apoptosis of B6 macrophages. Notably, B. anthracis sensitizes macrophages by promoting TNF production concomitantly with LeTx-mediated inactivation of p38 MAPK signaling. LeTx intoxication of TLR3/4- or TNF-activated macrophages similarly sensitized macrophages to TNF- and RIPK1 kinase activity–dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation and cell death induction. Caspase-8/RIPK3-deficient mice were significantly protected from B. anthracis-induced lethality, demonstrating the in vivo pathophysiological relevance of this cytotoxic mechanism in lethal anthrax.

Results

B. anthracis Infection and LeTx Intoxication Activate the Canonical NLRP3 Inflammasome.

Macrophages of BALB/c and 129S mice express a “LeTx-sensitive” Nlrp1b allele that rapidly responds to LeTx intoxication with NLRP1b inflammasome activation and pyroptosis (7–9). Surprisingly, despite B6 bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) lacking a LeTx-sensitive Nlrp1b allele (7, 8), B. anthracis infection elicited substantial secretion of IL-1β and robust cell death of B6 macrophages (Fig. 1 A and B). Consistent with bacterial secreted toxins driving these responses, conditioned bacterial broth of B. anthracis cultures that is devoid of vegetative bacteria elicited high levels of IL-1β secretion and cell death from lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-primed B6 BMDMs (Fig. 1 C and D). To identify the responsible toxin, LPS-primed BMDMs were subsequently treated with purified B. anthracis EdTx or LeTx. Whereas EdTx failed to induce cell death of intoxicated macrophages, LeTx induced significant secretion of IL-1β and recapitulated the cell death response of B. anthracis-conditioned broth (Fig. 1 E and F). These results suggest that B. anthracis infection and LeTx intoxication promote inflammasome activation in B6 macrophages despite the absence of a LeTx-responsive NLRP1b inflammasome.

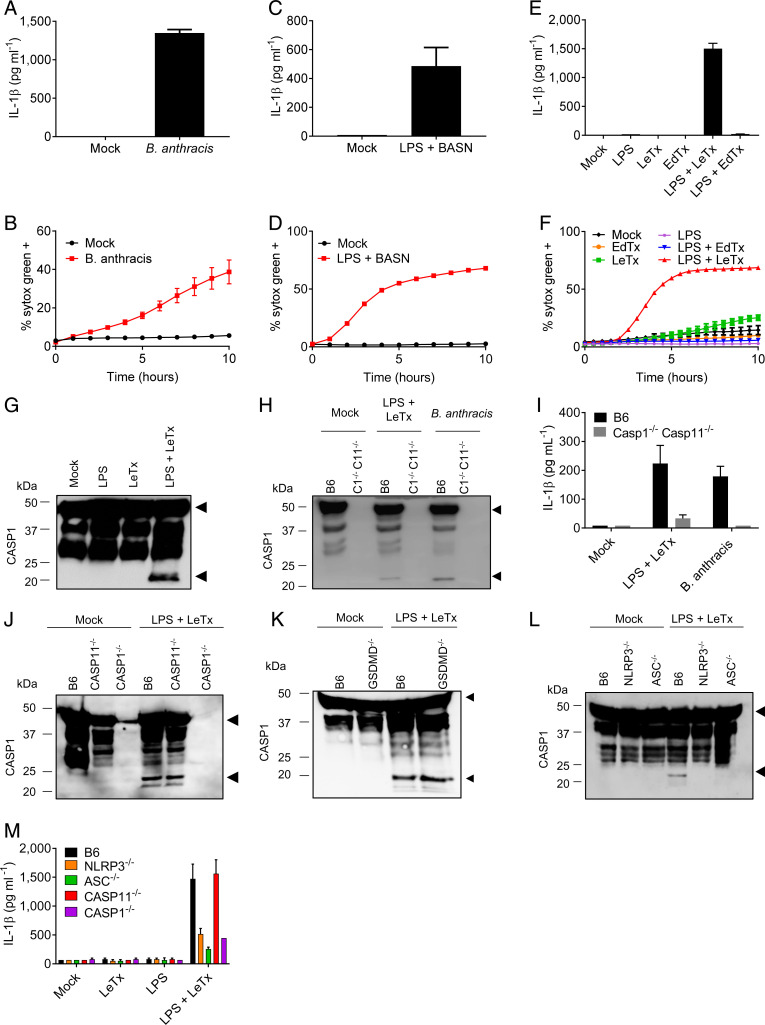

Fig. 1.

B. anthracis infection and LeTx activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Wild-type C57Bl6 (B6) BMDMs, or BMDMs with genotypes indicated in the figures, were stimulated or infected as described in Materials and Methods. (A–F) Kinetics of cell death induction were analyzed by quantification of cell permeabilization, and supernatants were collected at 4 h poststimulation and analyzed for IL-1β. (G–M) Lysates were immunoblotted for caspase-1, and supernatants were analyzed for IL-1β at 4 h poststimulation. Arrows on caspase-1 Western blots denote the proform (Upper arrow), and cleavage fragments (Lower arrow), respectively. Data are representative of two to four experiments. Bars indicate mean plus SD. BASN, conditioned bacterial broth of B. anthracis cultures.

Consistent with caspase-1 driving IL-1β production, we observed robust caspase-1 maturation in lysates of LPS + LeTx-stimulated cells (Fig. 1G). Notably, LeTx elicited caspase-1 maturation only in LPS-primed B6 macrophages (Fig. 1 G and H), whereas B. anthracis infection activated caspase-1 in unprimed B6 macrophages as well (Fig. 1H). This suggests that vegetative bacteria are able to prime macrophages for subsequent inflammasome activation by secreted LeTx. In contrast to wild-type BMDMs, IL-1β secretion from Casp1−/−Casp11−/− BMDMs was blunted upon stimulation with LPS + LeTx or infection with live B. anthracis (Fig. 1I), further suggesting a role for inflammasome activation in B. anthracis-induced IL-1β secretion. Caspase-1 maturation was unaffected in Casp11−/− BMDMs (Fig. 1J) and GSDMD−/− macrophages (Fig. 1K), suggesting that the noncanonical inflammasome pathway was dispensable for LeTx-induced caspase-1 activation in LPS-primed macrophages. Contrastingly, caspase-1 cleavage was abolished in Nlrp3−/− and in Asc−/− BMDMs (Fig. 1L), formally establishing that LeTx activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Moreover, LPS + LeTx-induced IL-1β secretion was inhibited in Nlrp3−/−, Asc−/−, and Casp1−/− BMDMs, whereas wild-type and Casp11−/− BMDMs secreted comparable amounts of IL-1β in the culture supernatants (Fig. 1M). Engagement of the canonical NLRP3 inflammasome explains the need for LPS priming for induction of caspase-1 maturation and IL-1β secretion (10). This is in marked contrast with 129S and BALB/c macrophages that express a “LeTx-responsive” NLRP1b inflammasome, in which LeTx induces caspase-1 activation and cell death regardless of LPS priming (SI Appendix, Fig. 1 A–E) (7, 8). Collectively, these results demonstrate that B. anthracis infection and LeTx intoxication engage the canonical NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages lacking a LeTx-responsive NLRP1b inflammasome.

TRIF Signaling Sensitizes Macrophages to LeTx-Induced Apoptosis and NLRP3 Activation.

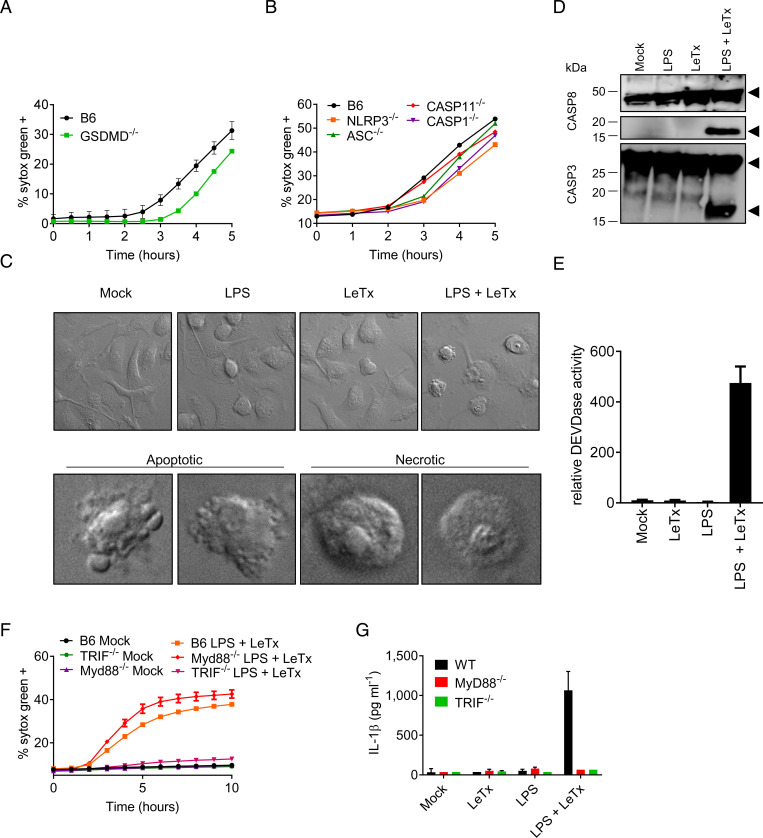

Considering the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in caspase-1 maturation and IL-1β secretion, we hypothesized that LeTx-induced macrophage cell death may correspond to GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis. However, LeTx-induced cell death was only slightly delayed (±1 h) in Gsdmd−/− BMDMs compared to wild-type BMDMs (Fig. 2A). Macrophages lacking NLRP3, ASC, or caspase-1 resembled Gsdmd−/− BMDMs with each showing LeTx-induced Sytox Green staining only slightly lagging behind that of wild-type and Casp11−/− BMDMs at 3 h postintoxication and with minimal differences observed at subsequent time points (Fig. 2B). These observations suggest that LeTx induces cell death largely independently of GSDMD and the NLRP3 inflammasome in LPS-primed BMDMs. We excluded a role for necroptosis because mixed lineage kinase domain like pseudokinase (MLKL) deficiency had no effect on LeTx-induced cell death; and cell death in macrophages with a combined deletion in GSDMD and MLKL phenocopied GSDMD-deficient cells (SI Appendix, Fig. 2A). An earlier report suggested that LeTx induces apoptosis of LPS-primed macrophages through activation of protein kinase R (PKR) (11). Consistent with induction of apoptosis, careful inspection of confocal micrographs showed cells with a classical apoptotic appearance (shrunken and blebbing) in addition to cells with a swollen morphology that is reminiscent of secondary necrosis (Fig. 2C). In agreement, flow cytometry analysis identified a population of ∼30% apoptotic cells that was positive for the early apoptosis marker Annexin-V while being impermeable to propidium iodide (PI), in addition to an equally sized population of double-positive cells (SI Appendix, Fig. 2B). Moreover, immunoblotting indicated cleavage of apoptotic caspases 3 and 8, which required combined stimulation with LPS and LeTx (Fig. 2D). An analysis of DEVDase activity further corroborated these results and showed markedly increased DEVDase activity levels specifically in lysates of LPS + LeTx-treated macrophages compared to those of untreated cells, LPS-primed, or LeTx-intoxicated BMDMs (Fig. 2E). Although TLR3 and TLR4 activation generally does not induce apoptosis, these receptors can activate caspase-8 through the adaptor TRIF (12). TRIF was indeed required for LeTx-induced apoptosis in LPS-primed BMDMs, whereas MyD88 was dispensable (Fig. 2F). We extended this observation to TLR3 by demonstrating that LeTx also elicited cell death in macrophages primed with the TLR3 agonist poly(I:C), whereas BMDMs primed with the TRIF-independent TLR1/2 agonist Pam3CSK4 resisted LeTx-induced cell death (SI Appendix, Fig. 2 C and D). Notably, both MyD88 and TRIF deficiency abolished LeTx-induced IL-1β secretion from LPS-primed BMDMs (Fig. 2G). TRIF was also required for IL-1β secretion from poly(I:C)-primed cells, whereas Pam3CSK4-primed BMDMs failed to secrete IL-1β (SI Appendix, Fig. 2E). Caspase-1 cleavage and up-regulation of pro–IL-1β protein levels were also defective in poly(I:C) + LeTx-stimulated TRIF−/− BMDMs (SI Appendix, Fig. 2F). Together, these results show that TRIF signaling sensitizes macrophages to LeTx-induced apoptosis and NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated IL-1β secretion in TLR3- and TLR4-primed macrophages.

Fig. 2.

LeTx sensitizes TLR3/4-primed macrophages to TRIF-dependent apoptosis and NLRP3 activation. Wild-type C57Bl6 (B6) BMDMs, or BMDMs with genotypes indicated in the figures, were stimulated with LPS + LeTx as described in Materials and Methods. Kinetics of cell death induction were analyzed by quantification of cell permeabilization (A, B). At 4 h after stimulation, cell death induction was characterized in B6 BMDMs by microscopy. (C Upper) Representative image of BMDMs stimulated with the indicated treatments. (C Lower) Close-up images of LPS + LeTx treated BMDMs with typical apoptotic and necrotic morphology. At 4 h after stimulation, lysates were collected and immunoblotted for caspase-3 and -8. Black arrows denote the proform (Upper arrows) and matured form (Lower arrows) of caspase-3 or -8 (D). Analysis of DEVDase activity in BMDMs, 4 h after stimulation with the indicated treatments (E). Kinetics of cell death induction by the indicated treatments were analyzed by quantification of cell permeabilization, and at 4 h poststimulation, supernatants were collected and analyzed for IL-1β (F, G). Data are representative of three to six experiments. Bars indicate mean plus SD.

TNF Mediates B. anthracis Infection–Induced NLRP3 Activation and Macrophage Cell Death.

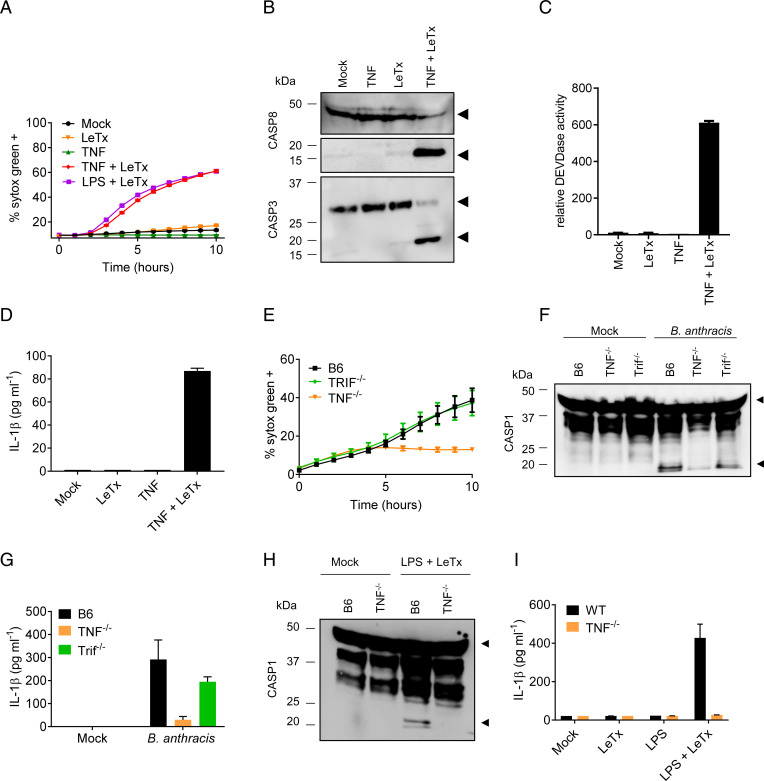

Considering that death receptors also induce apoptosis (13), and in light of an early report suggesting that LeTx induces nonapoptotic cell death in TNF-primed macrophages (14), we further examined LeTx-induced cell death in TNF-primed macrophages. LeTx potently induced cell death in TNF-primed BMDMs with kinetics resembling that seen in LPS-primed cells (Fig. 3A). As in LPS-primed BMDMs (SI Appendix, Fig. 2A), a role for necroptosis was ruled out because genetic inactivation of RIPK3 or MLKL failed to inhibit LeTx-induced cell death in TNF-primed BMDMs (SI Appendix, Fig. 3A). TNF + LeTx-induced cell death in macrophages lacking the pyroptosis effector GSDMD was initially slightly delayed (±1 h), but eventually caught up with wild-type BMDMs (SI Appendix, Fig. 3B). We observed both apoptotic and necrotic cells in confocal differential interference contrast micrographs of TNF + LeTx-stimulated cells, which was consistent with the presence of sizeable Annexin-V+/PI− as well as double-positive cell subpopulations in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots (SI Appendix, Fig. 3 C–E). Apoptosis was further confirmed by Western blot analysis showing robust cleavage of caspases 3 and 8 (Fig. 3B), and by demonstrating DEVDase activity in lysates of TNF + LeTx-treated macrophages (Fig. 3C). Moreover, TNF + LeTx stimulation, but not TNF or LeTx alone, induced secretion of IL-1β in the culture supernatants (Fig. 3D). We conclude from these data that LeTx primarily induces apoptosis and promotes IL-1β secretion from TNF-primed macrophages.

Fig. 3.

TNF mediates B. anthracis infection–induced NLRP3 activation and macrophage cell death. Wild-type C57Bl6 (B6) BMDMs, or BMDMs with genotypes indicated in the figures, were stimulated as described in Materials and Methods. Kinetics of cell death induction were analyzed by quantification of cell permeabilization (A). At 4 h after stimulation with the indicated treatments, lysates were collected and immunoblotted for caspase-3 and -8 (B), or analyzed for DEVDase activity (C). Culture supernatants were analyzed for IL-1β (D). Kinetics of B. anthracis-induced cell death induction were analyzed in BMDMs of the indicated genotypes by quantification of cell permeabilization (E). Cell lysates were immunoblotted for caspase-1, and culture supernatants were analyzed for IL-1β (F, G). At 4 h after stimulation with the indicated treatments, lysates were collected and immunoblotted for caspase-1, and culture supernatants were analyzed for IL-1β (H, I). Black arrows on immunoblots denote the proform (Upper arrows) and matured form (Lower arrows) of caspase-1, -3, or -8. Figures are representative of three to six experiments. Bars indicate mean plus SD.

To examine the relative importance of TRIF and TNF signaling in the context of bacterial infection, we next infected TRIF−/− and TNF-deficient BMDMs with live B. anthracis. Wild-type and TRIF knockout macrophages mounted a comparable cell death response, whereas TNF-deficient macrophages were markedly protected from B. anthracis-induced cell death (Fig. 3E). This indicates that B. anthracis primarily kills macrophages through a TNF-dependent mechanism. Caspase-1 activation and IL-1β secretion were also markedly reduced in TNF-deficient BMDMs that had been infected with live B. anthracis (Fig. 3 F and G). Unexpectedly, we found that TNF−/− macrophages were also partially protected from LPS + LeTx-induced cell death (SI Appendix, Fig. 4 A and B). TNF deficiency also largely abolished caspase-1 maturation and IL-1β secretion following LPS + LeTx stimulation (Fig. 3 H and I), suggesting that NLRP3 inflammasome activation and apoptosis in LPS + LeTx-stimulated BMDMs were partially relayed through TLR4/TRIF-mediated TNF production. Consistent with this model, we detected significant levels of TNF in culture media of LeTx-intoxicated macrophages that have been primed with poly(I:C) or LPS, but not in those primed with the TRIF-independent TLR1/2 agonist Pam3CSK4 (SI Appendix, Fig. 4C). In conclusion, TNF is a key driver of both cell death induction and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in B. anthracis-infected and LeTx-intoxicated macrophages.

TNF Signaling through TNF-R1 and TNF-R2 Is Required for LeTx-Sensitized Macrophage Apoptosis.

The critical involvement of TNF in B. anthracis-infected macrophages prompted us to investigate downstream mechanisms controlling LeTx-induced cell death in TNF-primed macrophages. TNF exerts its activities through TNF receptor-1 (TNFR1) and TNFR2, both of which are expressed by macrophages. Costimulation of wild-type macrophages with LeTx and human TNF—the latter being a selective ligand of murine TNFR1, but not TNFR2 (15)—failed to induce cell death and cleavage of caspases 8 and 3 as seen with murine TNF (SI Appendix, Fig. 5 A and B), suggesting a key role for TNFR2 in sensitizing cells to LeTx-induced cytotoxicity upon TNF priming. In agreement, genetic deletion of either TNFR1 or TNFR2 sufficed to abolish LeTx-induced killing of murine TNF-primed macrophages (Fig. 4A) as well as cleavage of caspases 8 and 3 (Fig. 4B). Under certain conditions (16), TNFR2 may induce depletion of TRAF2 and cellular inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (cIAP) 1 and 2 to accelerate TNFR1-dependent activation of caspase-8. We noted that cellular TRAF2 levels were markedly reduced in wild-type macrophages treated with murine TNF, contrary to cells stimulated with human TNF. Notably, TNFR2-induced TRAF2 depletion occurred regardless of LeTx costimulation, whereas LeTx stimulation alone did not alter TRAF2 levels (SI Appendix, Fig. 5C). Although further analysis is required, these results suggest that TNFR2-mediated TRAF2 depletion may sensitize LeTx-intoxicated macrophages to TNFR1-mediated apoptosis.

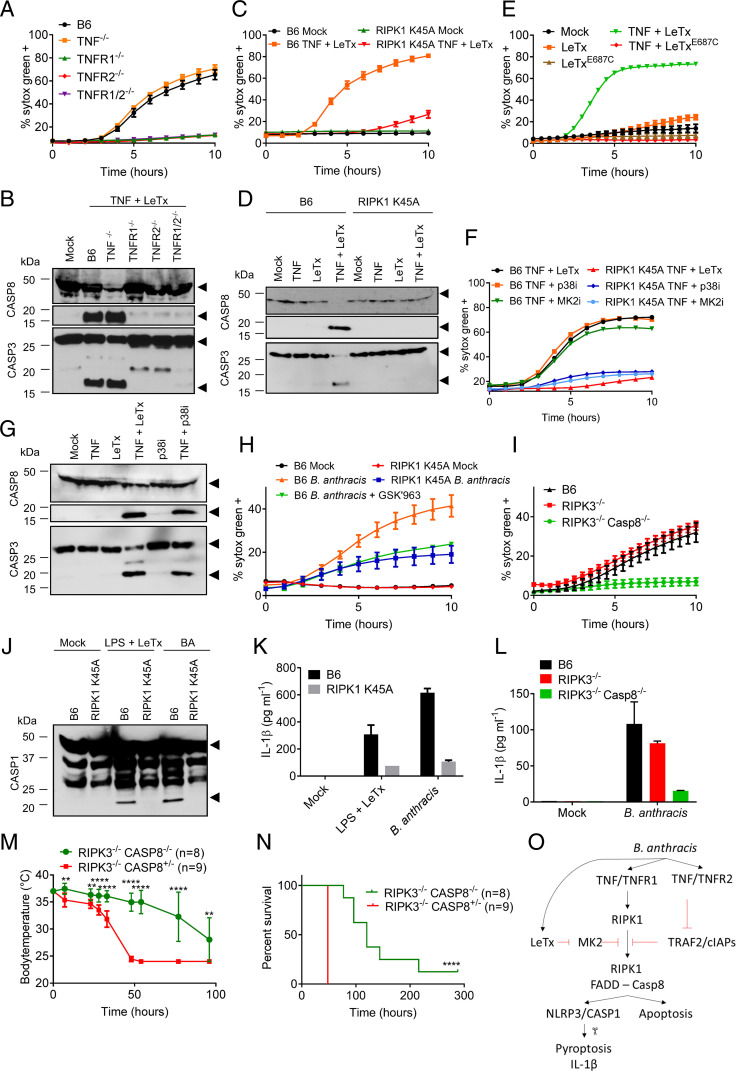

Fig. 4.

RIPK1-mediated NLRP3 activation and caspase-8–dependent apoptosis protects against B. anthracis-induced lethality in vivo. Wild-type C57Bl6 (B6) BMDMs, or BMDMs with genotypes indicated in the figures, were stimulated as described in Materials and Methods. Kinetics of cell death induction were analyzed by quantification of cell permeabilization until 4 h after stimulation, and lysates were then collected and immunoblotted for caspase-3 and -8 (A–I). BMDMs with genotypes indicated in the figures, were stimulated or infected as described in Materials and Methods. At 4 h poststimulation, lysates were collected and immunoblotted for caspase-1 (J), and supernatants were analyzed for IL-1β (K and L). Black arrows on immunoblots denote the proform (Upper arrows) and matured form (Lower arrows) of caspase-1, -3, or -8. Temperature (M) and lethality (N) data of mice with genotypes indicated in the figures, and infected with live B. anthracis as described in Materials and Methods. Student’s t test was used to compare temperature at each measurement (**P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001), and Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test was used for analysis of the survival data (****P < 0.0001). Schematic representation of the B. anthracis-induced cell death mechanism (O). Figures are representative of two to four experiments. Bars indicate mean plus SD.

RIPK1 Kinase Activity Is a Critical Regulator of LeTx-Induced Apoptosis and NLRP3 Activation.

The serine/threonine kinase activity of RIPK1 is a key regulator of TNF-induced apoptosis, necroptosis, and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nec1s, a selective pharmacological inhibitor of RIPK1 kinase activity (17), abolished cleavage of caspases 8 and 3 and markedly reduced LeTx-induced cell death of TNF-primed wild-type macrophages (SI Appendix, Fig. 5 D–G). Similar results were obtained with the structurally unrelated RIPK1 kinase inhibitor GSK′963 (18), but not its inactive enantiomer GSK′962 (SI Appendix, Fig. 5H). LeTx-dependent killing and cleavage of caspases 8 and 3 were also markedly inhibited in TNF-primed macrophages from RIPK1 K45A homozygous knockin mice (19) that express a catalytically inactive RIPK1 mutant from the endogenous locus (Fig. 4 C and D). This was further corroborated by fewer cell corpses being observed in high-resolution microscopy images (SI Appendix, Fig. 5I), and by FACS analysis showing that RIPK1 K45A knockin macrophages lacked the Annexin-V+/PI− and double-positive cell subpopulations seen in FACS plots of TNF + LeTx-treated wild-type BMDMs (SI Appendix, Fig. 5J). RIPK1 K45A BMDMs (SI Appendix, Fig. 6 A and B) and wild-type BMDMs that had been pretreated with Nec1s or GSK′963 (SI Appendix, Fig. 6 C–E) were also resistant to LPS + LeTx-induced apoptosis and cleavage of caspases 8 and 3. Consistent with RIPK1 kinase-dependent apoptosis induction, LPS- and TNF-primed RIPK3−/−Casp8−/− BMDMs and RIPK3−/−FADD−/− BMDMs strongly resisted LeTx-induced cell death, whereas RIPK3 was dispensable (SI Appendix, Fig. 6 F and G). RIPK1 kinase activity also was critical for LPS + LeTx-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation because caspase-1 maturation and secretion of IL-1β were abolished in RIPK1 K45A BMDMs (SI Appendix, Fig. 6 H and I). Similarly, LPS-primed wild-type macrophages that had been pretreated with Nec1s failed to secrete IL-1β upon LeTx intoxication (SI Appendix, Fig. 6J). Additionally, RIPK3−/− macrophages were partially defective in LPS + LeTx-stimulated caspase-1 maturation and IL-1β secretion, whereas these responses were abolished in RIPK3−/−Casp8−/− BMDMs (SI Appendix, Fig. 6 K and L). Together, these results establish RIPK1 kinase activity as a critical regulator of LeTx-induced apoptosis and NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Inactivation of p38 MAPK/MK2 Signaling Sensitizes LeTx-Intoxicated Macrophages to RIPK1-Dependent NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Apoptosis.

LeTx is an exquisitely selective metalloprotease that cleaves MAPKK family members, which results in defective activation of p38 MAPK (6). We found that the catalytically inactive LF E687C mutant failed to induce cell death in TNF- or LPS-primed macrophages (Fig. 4E and SI Appendix, Fig. 7A). Notably, the LF E687C mutant also failed to elicit IL-1β secretion in culture media of LPS-primed macrophages (SI Appendix, Fig. 7B). LeTx-induced IL-1β secretion was linked to p38 inactivation because the p38 inhibitor SB203580 resembled LeTx in inducing RIPK1 kinase activity–dependent (SI Appendix, Fig. 7 C and D) and NLRP3-mediated (SI Appendix, Fig. 7 E and F) caspase-1 cleavage and IL-1β secretion from LPS-primed BMDMs. This suggests that cleavage of MAPKK substrates rather than cytosolic entry of LF promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Consistent with a previous report suggesting that p38 inhibition mimics the cytotoxic effect of LeTx in LPS-primed macrophages (11), the p38 inhibitor SB203580 also induced efficient killing of TNF- as well as LPS-primed wild-type BMDMs, but not RIPK1 K45A macrophages (Fig. 4F and SI Appendix, Fig. 7G). We speculated that this was relayed by the p38 MAPK substrate MK2 because the latter was recently identified as an important cell death checkpoint controlling RIPK1 kinase–dependent cell death induction (20–23). In agreement, the MK2 inhibitor PF-3644022 induced cell death of TNF- and LPS-primed B6 BMDMs, but not RIPK1 K45A macrophages (Fig. 4F and SI Appendix, Fig. 7G). Western blot analysis further confirmed that inhibition of p38 signaling induced cleavage of caspases 8 and 3 at levels comparable to those seen with LeTx in TNF- or LPS-primed BMDMs (Fig. 4G and SI Appendix, Fig. 7H). Together, these results suggest that LeTx-mediated inhibition of the MAPKK/p38/MK2 kinase cascade may act as a checkpoint for switching TNF- and LPS-induced proinflammatory signaling into RIPK1 kinase activity–dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation and cell death induction.

Role of RIPK1 in B. anthracis-Induced Apoptosis and NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation.

Considering the central role of RIPK1 signaling in LeTx-mediated cell death and NLRP3 inflammasome activation, we next investigated its putative role in macrophages infected with live B. anthracis. Cell death induction was reduced by about half in wild-type BMDMs that had been pretreated with RIPK1 kinase inhibitor GSK′963 and in B. anthracis-infected RIPK1 K45A BMDMs (Fig. 4H). Moreover, inhibition of B. anthracis-induced cell death was nearly complete in RIPK3−/−Casp8−/− BMDMs, whereas RIPK3−/− BMDMs showed no protection (Fig. 4I). Together, these results suggest that live B. anthracis promoted both RIPK1 kinase activity–dependent and –independent apoptosis of infected macrophages. B. anthracis-induced caspase-1 maturation fully depended on RIPK1 kinase activity (Fig. 4J). Moreover, IL-1β secretion was largely blunted in RIPK1 K45A and RIPK3−/−Casp8−/− BMDMs, but not in RIPK3−/− BMDMs (Fig. 4 K and L).

Caspase-8 Promotes B. anthracis-Induced Lethality In Vivo.

To extend these results, we examined the physiological relevance of B. anthracis-induced caspase-8 activation in an in vivo model of lethal anthrax. A cohort of RIPK3−/−Casp8−/− mice and littermate control RIPK3−/−Casp8+/− mice was infected with 5 × 106 colony-forming units (CFU) B. anthracis followed by antibiotics treatment to mimic acute LeTx-driven toxicity before body temperature and survival were monitored over time. All RIPK3−/−Casp8+/− control mice had reached humane endpoints of hypothermia below 25 °C within 2 d and had to be killed. As in B. anthracis-infected macrophages (SI Appendix, Fig. 6), RIPK3 deficiency failed to provide any protection in B. anthracis-infected animals (SI Appendix, Fig. 8 A and B). In marked contrast, RIPK3−/−Casp8−/− mice were significantly delayed in B. anthracis-induced hypothermia and lethality, with some mice still alive when the study protocol was ended on day 12 (Fig. 4 M and N). These results show that anthrax-associated caspase-8–mediated apoptosis is detrimental to the host. Interestingly, this contrasts with caspase-8–mediated apoptosis in Yersinia-infected animals that was previously shown to be essential for survival of infected hosts (24, 25).

Discussion

LeTx has been recognized as a major determinant of lethal anthrax since its initial purification 60 y ago (26, 27). About a decade ago, LeTx internalization by myeloid cells was shown to be essential for systemic dissemination of the pathogen in B. anthracis-infected mice (5). This suggests that LeTx serves to target neutrophils and macrophages during early stages of infection in order to paralyze the host’s immune defenses against the pathogen and to allow vegetative B. anthracis bacteria to establish systemic infection. At later stages of infection, LeTx then targets cardiomyocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells to induce mortality (2).

Despite the central importance of myeloid cells in anthrax pathogenesis, the molecular mechanisms underlying cell death of B. anthracis-infected macrophages are poorly understood. Macrophages expressing a LeTx-sensitive Nlrp1b allele rapidly induce activation of the NLRP1b inflammasome and are killed by pyroptosis upon LeTx intoxication (7, 8, 28, 29). However, human NLRP1 and the Nlrp1b allele of B6 mice are nonresponsive to LeTx, prompting our choice of the latter as an experimental model to investigate B. anthracis host–pathogen interactions in the absence of LeTx-induced NLRP1b inflammasome activation (7, 8).

Our findings revealed complex host–pathogen interactions between B. anthracis and its host in which infection is met with TNF secretion. Although the B. anthracis factors and host receptors that promote TNF production in infected mouse macrophages remain unclear, phagocytosis of B. anthracis peptidoglycan was previously shown to stimulate TNF production in human monocytes (30). We showed here that engagement of both TNFR1 and TNFR2 by the cytokine, concomitant with proteolytic inactivation of MAPKK/p38/MK2 signaling in LeTx-intoxicated macrophages, is required to induce RIPK1 activity–dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation as well as caspase-8–mediated apoptosis (Fig. 4O). Notably, caspase-8 deficiency abolished cell death induction in both LeTx-intoxicated and B. anthracis-infected macrophages. Moreover, cell death of LeTx-intoxicated macrophages fully relied on RIPK1 kinase activity, whereas RIPK1 kinase activity accounted for only about half of the cytotoxicity levels in B. anthracis-infected macrophages. An interesting question that awaits analysis is to what extent the scaffolding function of RIPK1 regulates caspase-8 activation in B. anthracis-infected macrophages. Another intriguing observation is that caspase-1 cleavage and IL-1β secretion in LeTx-intoxicated BMDMs were mediated by the canonical NLRP3 inflammasome (Fig. 1), whereas Yersinia-infected cells were previously reported to promote caspase-8–mediated cleavage of GSDMD and IL-1β (31, 32). It’s tempting to speculate that these differences are linked to LeTx selectively inactivating MAPK signaling, while the effector protein YopJ of Yersinia species antagonizes NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways by simultaneously inhibiting TAK1, IKK, and MKK proteins (31, 32).

Future studies should address whether the cell death pathways uncovered here also underlie LeTx-induced cytotoxicity in additional cell types that are implicated in anthrax-related mortality such as neutrophils, cardiomyocytes, and vascular smooth muscle cells. Considering that LeTx-induced macrophage cell death is a key determinant of B. anthracis systemic infection and anthrax-associated host lethality (5), this report significantly broadens our understanding of B. anthracis host–pathogen interactions and identifies TNF-induced caspase-8 activation and apoptosis as a target in lethal anthrax.

Materials and Methods

A detailed description of the materials and experimental procedures is available in the accompanying SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Methods Summary.

Mice.

A list of genetically modified mouse strains used in this study is available in SI Appendix, Table 1.

BMDM studies.

BMDMs were isolated and subsequently activated by LPS or TNF in combination with LeTx (500 ng/mL PA + 250 ng/mL LF, Quadratech). Inhibitors for RIPK1 (50 µM Nec1s and 1 µM GSK′962 or GSK′963), p38 (25 µM SB203580 and SB202190), and MK2 (50 µM PF-3644022) were used at indicated concentrations.

Antibodies.

The following antibodies were used: caspase-1 (Adipogen), caspase-8 (Enzo; Cell Signaling), caspase-3 (Cell Signaling), RIPK1 (BD Biosciences), IL-1β (Genetex), TRAF2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Cytokine analysis and Annexin-V staining for FACS.

Luminex assay (Bio-Rad) and Annexin-V staining (BD Pharmingen) were used to quantify cytokine release and apoptosis.

Cell death kinetics.

A plate-based fluorometric assay (FLUOstar Omega BMG Labtech or Incucyte Zoom [Essenbio]) was used to quantify cell permeabilization (5 µM SYTOX Green).

DEVDase activity.

Caspase-3/7 activation was detected using CellEvent Caspase3/7 Green substrate (Invitrogen). Data were acquired and analyzed using the Incucyte Zoom system (Essenbio).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the VIB Bio Imaging core for assistance with imaging, and Vishva Dixit (Genentech) for generous supply of mutant mice. F.V.H. and N.V.O. are postdoctoral fellows with the Fund for Scientific Research Flanders. We also thank P. Wattiau (Centrum voor Onderzoek in Diergeneeskunde en Agrochemie–Veterinary and Agrochemical Research Centre Brussels) for providing the B. anthracis 34F2 (Sterne) strain. P.V. is the recipient of Methusalem Grants BOF09/01M00709 and BOF16/MET_V/007. T.-D.K. is supported by NIH Grants AR056296, CA163507, and AI101935 and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities. This work was supported by the Ghent University Concerted Research Actions (Grant BOF14/GOA/013), European Research Council Grant 683144 (PyroPop), the Fund for Scientific Research Flanders Grant G014221N, and a Baillet Latour Medical Research Grant (to M.L.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2116415119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Moayeri M., Leppla S. H., Vrentas C., Pomerantsev A. P., Liu S., Anthrax pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 69, 185–208 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu S., et al. , Key tissue targets responsible for anthrax-toxin-induced lethality. Nature 501, 63–68 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutt J. A., et al. , Lethal factor, but not edema factor, is required to cause fatal anthrax in cynomolgus macaques after pulmonary spore challenge. Am. J. Pathol. 184, 3205–3216 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pezard C., Berche P., Mock M., Contribution of individual toxin components to virulence of Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 59, 3472–3477 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu S., et al. , Anthrax toxin targeting of myeloid cells through the CMG2 receptor is essential for establishment of Bacillus anthracis infections in mice. Cell Host Microbe 8, 455–462 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duesbery N. S., et al. , Proteolytic inactivation of MAP-kinase-kinase by anthrax lethal factor. Science 280, 734–737 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyden E. D., Dietrich W. F., Nalp1b controls mouse macrophage susceptibility to anthrax lethal toxin. Nat. Genet. 38, 240–244 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Opdenbosch N., et al. , Activation of the NLRP1b inflammasome independently of ASC-mediated caspase-1 autoproteolysis and speck formation. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–14 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedlander A. M., Bhatnagar R., Leppla S. H., Johnson L., Singh Y., Characterization of macrophage sensitivity and resistance to anthrax lethal toxin. Infect. Immun. 61, 245–252 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauernfeind F. G., et al. , Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J. Immunol. 183, 787–791 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park J. M., Greten F. R., Li Z. W., Karin M., Macrophage apoptosis by anthrax lethal factor through p38 MAP kinase inhibition. Science 297, 2048–2051 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gitlin A. D., et al. , Integration of innate immune signaling by caspase-8 cleavage of N4BP1. Nature 587, 275–280 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varfolomeev E. E., et al. , Targeted disruption of the mouse Caspase 8 gene ablates cell death induction by the TNF receptors, Fas/Apo1, and DR3 and is lethal prenatally. Immunity 9, 267–276 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S. O., et al. , Sensitizing anthrax lethal toxin-resistant macrophages to lethal toxin-induced killing by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 7413–7421 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis M., et al. , Cloning and expression of cDNAs for two distinct murine tumor necrosis factor receptors demonstrate one receptor is species specific. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 2830–2834 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fotin-Mleczek M., et al. , Apoptotic crosstalk of TNF receptors: TNF-R2-induces depletion of TRAF2 and IAP proteins and accelerates TNF-R1-dependent activation of caspase-8. J. Cell Sci. 115, 2757–2770 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi N., et al. , Necrostatin-1 analogues: Critical issues on the specificity, activity and in vivo use in experimental disease models. Cell Death Dis. 3, e437 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berger S. B., et al. , Characterization of GSK’963: A structurally distinct, potent and selective inhibitor of RIP1 kinase. Cell Death Discovery 1, 15009 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polykratis A., et al. , Cutting edge: RIPK1 Kinase inactive mice are viable and protected from TNF-induced necroptosis in vivo. J. Immunol. 193, 1539–1543 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dondelinger Y., et al. , MK2 phosphorylation of RIPK1 regulates TNF-mediated cell death. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 1237–1247 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menon M. B., et al. , p38MAPK/MK2-dependent phosphorylation controls cytotoxic RIPK1 signalling in inflammation and infection. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 1248–1259 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaco I., et al. , MK2 Phosphorylates RIPK1 to prevent TNF-induced cell death. Mol. Cell 66, 698–710 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lalaoui N., et al. , Targeting p38 or MK2 enhances the anti-leukemic activity of Smac-Mimetics. Cancer Cell 29, 145–158 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson L. W., et al. , RIPK1-dependent apoptosis bypasses pathogen blockade of innate signaling to promote immune defense. J. Exp. Med. 214, 3171–3182 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dondelinger Y., et al. , Serine 25 phosphorylation inhibits RIPK1 kinase-dependent cell death in models of infection and inflammation. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–16 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanley J. L., Smith H., Purification of factor I and recognition of a third factor of the anthrax toxin. J. Gen. Microbiol. 26, 49–63 (1961). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beall F. A., Taylor M. J., Thorne C. B., Rapid lethal effect in rats of a third component found upon fractionating the toxin of Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 83, 1274–1280 (1962). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Vasconcelos N. M., et al. , An apoptotic caspase network safeguards cell death induction in pyroptotic macrophages. Cell Rep. 32, 107959 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Opdenbosch N., et al. , Caspase-1 engagement and TLR-induced c-FLIP expression suppress ASC/Caspase-8-dependent apoptosis by inflammasome sensors NLRP1b and NLRC4. Cell Rep. 21, 3427–3444 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iyer J. K., et al. , Inflammatory cytokine response to Bacillus anthracis peptidoglycan requires phagocytosis and lysosomal trafficking. Infect. Immun. 78, 2418–2428 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarhan J., et al. , Caspase-8 induces cleavage of gasdermin D to elicit pyroptosis during Yersinia infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E10888–E10897 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orning P., et al. , Pathogen blockade of TAK1 triggers caspase-8-dependent cleavage of gasdermin D and cell death. Science 362, 1064–1069 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.